A Letter from Ted Kaczynski to Aram

2022

May 14, 2022

Dear [REDACTED],

I apologize for taking so long to answer your very interesting letter, which I received on November 24, 2021. As [REDACTED] has probably told you, I've been moved to the Federal Medical Center at Butner, North Carolina because I'm suffering from cancer, and can't [STRUCK OUT "be"] expect[STRUCK OUT "ed"] to live much longer. I've been so burdened with the task of putting my affairs in order in anticipation of my death that I've had very little time for writing serious letters like the present one.

I think you know about my letter of February 7, 2022, to [REDACTED] in which I addressed one aspect of your letter to me. In the present letter I will address another aspect of it, and I hope to write one or more future letters in which I address other aspects of your letter. After that, however, I don't expect to engage in any further discussion of East Asian culture as it relates to anti-tech. The subject is fascinating and vitally important, but whatever time may be left to me has to be spent on writing down as much as I can of the ideas I've already developed; the exploration of new areas will have to be left to the next generation.

Here I will address your argument that East Asians are more submissive or more conformist, therefore less capable of revolution, than Americans and Europeans are. I remain unconvinced by your reasoning.

Your argument seems strongest when applied to Japan. See Technological Slavery, Letter to Dr. Skrbina, Nov. 23, 2004, Part IV.C, page 171 in the third edition, page 177 in the fourth edition.

A Spaniard named Jose Maria Gironella, who had spent considerable time in Japan during the 1960s, reported some experiences which may support your argument as it applies to that country. For example, he quoted a Japanese named Tajima: "We like hierarchy and we like to obey. At bottom, we feel more comfortable and protected in obeying."[1] And another Japanese: "You know that the Americans wanted to democratize us…. Do you know why they were partly successful? Because they ordered us to democratize."[2] But Gironela also reported experiences suggestig that the Daoist love of wild nature was widespread in Japan.[3] For example:

The route zigzagged [up the mountain], and as we gained altitude the forest grew more and more dense. Mikedo [a young woman] watched the forest as if hypnotized … and there was no room for doubt that in those moments the girl intensely loved the nature that surrounded us. ... All that was very beautiful. Until we saw some tree-cutters. ... It was a profanation. ... Mikedo shouted at them, 'You're crazy!' [4] We visited the part, clean but wild. 'You well know [said Mikedo] that nature must be respected and not dominated.' [5]

But I don't know what cultural changes Japan may have undergone since the 1960s.

However that may be, in 2018 The Economist reported on "Medical Care Services (MCS), Japan's largest operator of dementia-care homes":

China and Japan turn out to differ -- a lot. Notably, China is an exceptionally low-trust society. But bonds of family duty are stronger than in Japan, say MCS's bosses. ... When it entered China, MCS … built single-bed rooms to Japanese standards, offering the privacy and calm that pensioners in Japan demand. But Chinese clients wanted company and the lively din known as renao... .[6]

I'll say no more here about Japan, because I know so little about the Japanese.

I've read and continue reading a great deal more about China than about Japan. I'll begin with your statement that in China, "Ordinary people just lived as a serf as they had always lived." But it's doubtful whether or to what extent ordinary people did live as "serfs," even in the broadest sense of that word. Frederick W. Mote, a professor of Chinese History and Civilization at Princeton, wrote:

I adopt the view that most of the people in Song and later China [up to 1800?] were farmers who owned their land and could freely buy it and sell it, could bequeth it to their children and grandchildren or other persons, and could leave the land for other occupations or for other localities more or less as they chose. ... Those conditions had developed over a very long span of time.[7]

Mote concedes, however, that this view is the subject of "fierce debate."

Ebrey states the opposing view. According to her, most land in China was in possession of the big landowners; though there were also small landowners, and "there were economically peripheral areas, such as hilly areas far from trade routes and not suited to rice, where large landowners were nearly absent, and most farming was done by owner-cultivators."[8] If Ebrey's view is right, it suggests that the situation in regard to "serfdom" (oppression of the rural population) in China was roughly similar to what it was in Europe during the Middle Ages.

You write, "there had been numerious rebellions in China and Japan. But those rebellions didn't end the old value. Rebellions in China, Japan only mean the change of the ruing dynasty... ."

There was plenty of rebellion throughout Chinese history,[9] and even when the rebels were mere bandits who didn't challenge the old values they certainly were not submissive or conformist. And in many cases they did challenge the old values.[10]

You say that the rebels sometimes succeeded in overthrowing a dynasty, but they did not succeed in changing the old values -- the old dynasty was replaced by a new dynasty of the same time -- whereas "In the history of the West ... rebellions/revolutions often brought the total collapse of the old value and the arrival of the new value (i.e., the collapse of the western Rome, the Reformation of the 16th century, the French Revolution, American Revolution, Russian Revolution, etc.)."

But the collapse of the western Roman Empire was not the result of rebelliousness or nonconformity on the part of its citizens. The collapse came about through a gradual process of depopulation (perhaps caused by repeated epidemics) with political, economic, and cultural degeneration that left the western empire vulnerable to conquest by northern barbarians who completed the destruction of Roman culture. China too was conquered by northern barbarians, but these barbarians invaded a country that was densely populated, and was culturally and economically far more healthy than the wester Roman Empire was in its final phase. Consequently, the barbarians were absorbed into Chinese culture and its system of values.

The result was that Western Europe became politically and economically fragmented, whereas China (though sometimes divided politically) remained relatively unified; it never suffered anything like the fragmentation that Western Europe did. And I suggest that this was the most important of the factors that gave rise to the divergence between Chinese history and that or Europe.

The real root of the changes in values signaled by the Western revolutions was not any intrinsic rebelliousness or nonconformity amoung Europeans; it was natural selection operating on the numerious political, cultural and economic entities into which Western Europe was divided. During the 15th centry, intense economic and military competition amoung Western European states led the Portuguese and the Spanish governments to sponsor overseas exploration and colonization for the purpose of gaining control over gold and silver mines, and in order to create trade monopolies in valuable commodities. Other Western European nations soon followed suit. Their explorations exposed Europeans to new ideas from other civilizations, and these ideas, combined with intense competition, led to the rapid decay of old values and to technological progress and economic growth that eventually made the West dominant throughout the world. The great Western reovlutions were mere incidents in this process of economic, technological, cultural and political transformation of the West.

During the 15th century the Chinese had sailing ships that were much bigger and much begger than any European ships of the time, and the Chinese government sent out seaborne expeditions that explored as far west as the east coast of Africa. In fact, Chinese merchants had already traded as far as the east coast of Africa long before the 15th century. But the government did not continue its westward explorations, nor did it support the merchants' trading activities by conquering far-off territories and founding colonies. The government had no motive for ding such things, because China had no external economic competitors, or at least none that posed any serious challenges to China.[11]

The Chinese were certainly capable of technological progress. By 1100 AD they were already producing iron and steel by methods and in quantities that were not matched by the West until the 18th century.[12] But China underwent no industrial revolution comparable to that of the West, because iron and steel production and many other industries were strictly controlled by the government,[13] so that in these industries there was no competition internal to China. And because China faced no serious external economic competition, the government had no motive to accelerate progress by allowing private enterprise and free competition.

The Chinese were capable or rebellion that not only challenged old values but successfully replaced them with new ones. This is what happened when new ideas, and, more importantly, overwhelming political, economic, and military competition arrived from the Wst during the 19th century and up to 1900. At that time the humiliating intervention by the Wstern powers and Japan on the occasion of the Boxer rebellion led to rejection by the Chinese of the old values and a determination to replace the tradition system with new forms of social organization and new technologies that would enable China to defend itself against further humiliations.[14]

I'm aware of only two important pieces of evidence that Chinese people are more submissive or more conformist than Westerners:

(i) "[T]o survive the communal and interdependent life of a crowded Chinese family in a crowded Chinese village was possible only through the observation of an elaborate code of social norms. The premium was on conformity, not bold independence ... ."[15]

Assuming this is accurate, it should in no way lower our estimate of the Chinese capacity for revolution or for other large-scale social rebellion. Chinese loyalty -- and therefore Chinese submission and conformity -- traditionally were to the extended family or the village and not to any larger entity.[16] If anything, [STRUCK OUT "the"] solidariaty of local communities should facilitate rebellion against large-scale social entities.

(ii) Chinese (and other East Asian) immigrants and their immediate descendants are remarkably successful here in America; they word hard and do what is necessary to get ahead; and they probably have a very low rate of drug abuse and crime. But the fact that Chinese-Americans tend to conform in these respects may mean only that they have more self-discipline or better foresight than most other Americans do. Very little crime in America is a result of rational, thought-out rebellion. Almost all Americans who commit crimes, or abuse drugs, or fail to study in school and work hard, do so only because they are deficient in self-control, or else lack proper appreciation of the future consequences of their crimes or their drug abuse or their failure to study or work.

If it's true that Chinese have more self-discipline or better foresight than most Americans do, then Chinese should be more successful as rebels or revolutionaries than Americans are, because a revolutionary movement needs to be well disciplined and well organized.[17]

In any case, as I pointed out earlier, history has demonstrated the Chineses capacity for rebellion, including rebellion that challenges the values of the Chinese power-structure. So I don't think we should feel discouraged about the long-term prospects for anti-tech revolution in China.

I may be wrong. What I know abount China is only what I've read in a few books and articles, so I'm prepared to change my mind if you can show me evidence that I find convincing.

I look forward to hearing more from you in relation to the possible development of an anti-tech movement in East Asia.

Cordially yours for Wild Nature,

Ted Kaczynski

Original Scans

[1] Jose Maria Gironella, El Japon y su duende, Editorial Planeta, Barcelona, 1970, pp. 35-36. I recently received a letter from an anonymouse German who wrote: "We Germans feel more comfortable with law and order, discipline and [social] distance, obediance and predictability." Are the Germans less conforming than the Japanese?

[2] Ibid., p. 41.

[3] Ibid., pp. 144-45, 166, 173.

[4] Ibid., p. 166.

[5] Ibid., p. 173.

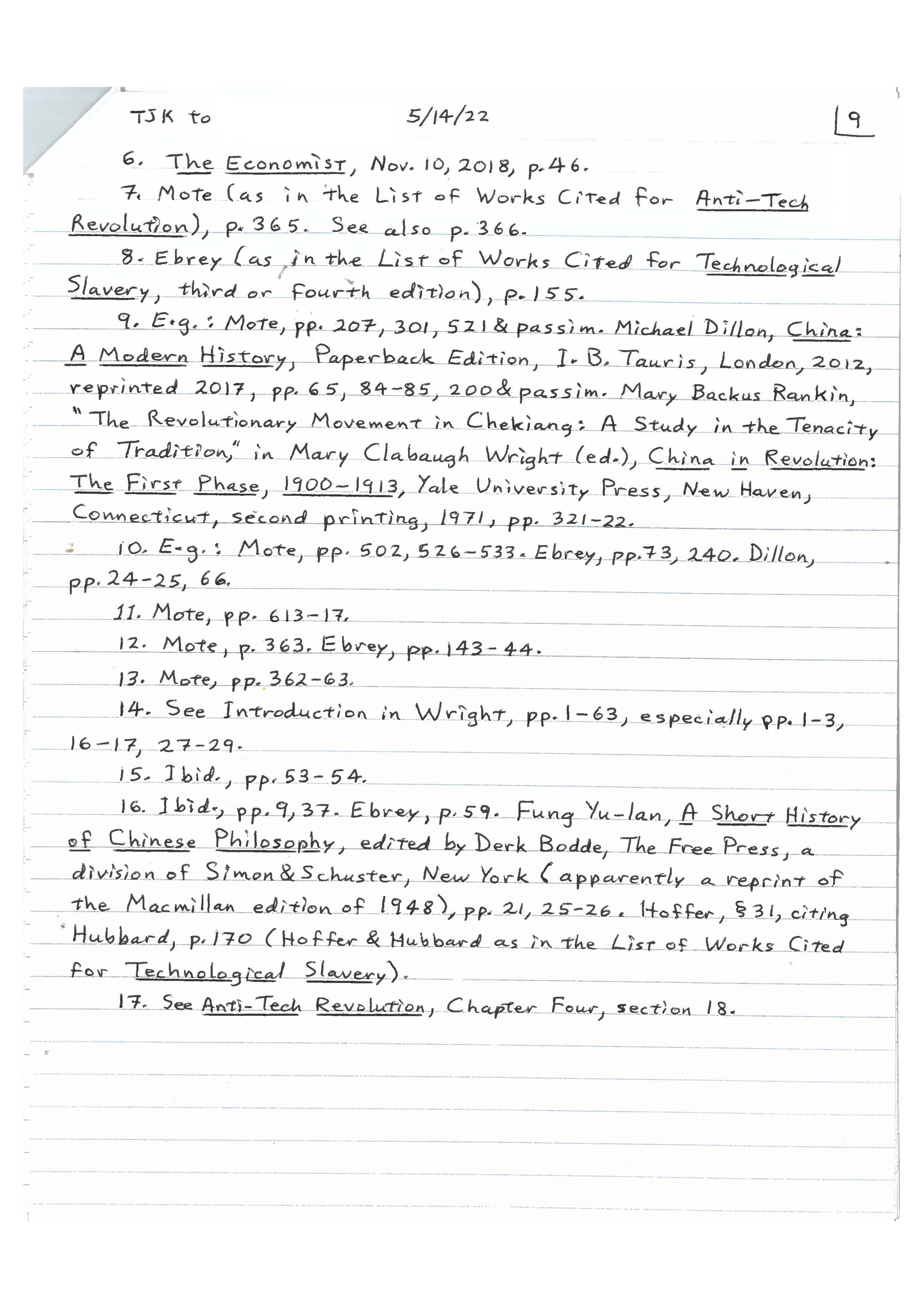

[6] The Economist, Nov. 10, 2018, p. 46.

[7] Mote (as in the List of Works Cited for Anti-Tech Revolution), p. 365. See also p. 366.

[8] Ebrey (as in the List of Works Cited for Technological Slavery, third or fourth edition), p. 155.

[9] E.g.: Mote, pp. 207, 301, 521 & passim. Michael Dillon, China: A Modern History, Paperback Edition, I. B. Tauris, London, 2012, reprinted 2017, pp. 65, 84-85, 200 & passim. Mary Backus Rankin, "The Revolutionary Movement in Chekiang: A Study in the Tenacity of Tradition," in Mary Clabaugh Wright (ed.), China in Revolution: The First Phase, 1900-1913, Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut, second printing, 1971, pp. 321-22.

[10] E.g.: Mote, pp. 502, 526-533. Ebrey, pp. 73, 240. Dillon, pp. 24-25, 66.

[11] Mote, pp. 613-17.

[12] Mote, p. 363. Ebrey, pp. 143-44.

[13] Mote, pp. 362-63.

[14] See Introduction in Wright, pp. 1-63, especially pp. 1-3, 16-17, 27-29.

[15] Ibid., pp. 53-54.

[16] Ibid., pp. 9, 37. Ebrey, p. 59. Fung Yu-Ian, A Short History of Chinese Philosophy, edited by Derk Bodde, The Free Press, a division of Simon & Schuster, New York (apparently a reprint of the Macmillan edition of 1948), pp. 21, 25-26. Hoffer, §31, citing Hubbard, p.170 (Hoffer & Hubbard as in the List of Works Cited for Technological Slavery).

[17] See Anti-Tech Revolution, Chapter Four, section 18.