Agnes Callard

Professora de filosofia define a indisciplina como emigrar sem destino definido

Agnes Callard, da Universidade de Chicago, diz que muitas almas inquietas encontram um refúgio na discordância

19/09/2018. Updated on 09/19/2018.

Quando estou sozinha tarde da noite, numa rua deserta, gosto de andar por cima das linhas amarelas duplas. Uma vez, decidi parar e me deitar, bem ali no meio da rua. Eu me mantive contraída, braços colados ao corpo, para que os carros pudessem passar pelos dois lados. Mas não era invisível e assustei um policial gentil que passou dirigindo por mim. Depois de determinar que eu não estava morta, bêbada ou chapada, ele concluiu que eu tinha tendências suicidas. Conversamos por um bom tempo. Não ajudou muito quando expliquei que, se eu quisesse ser atropelada, teria me movido alguns metros em uma direção ou outra. E escolhido uma rua mais movimentada. Ele queria saber por que, se não queria ser atropelada, eu estava deitada no meio da rua.

Havia muitos motivos. Eu queria ver o céu da perspectiva da rua; queria ficar nesse local secreto, que é sempre atravessado, mas nunca ocupado; acima de tudo, queria sentir como era deitar ali, com as linhas amarelas duplas estendendo-se por baixo de mim, da cabeça aos pés. Mas todas essas razões viraram não razões quando as declarei em voz alta. Ele não sabia o que pensar de mim, mas por fim admitiu que eu não parecia suicida. Insistiu em me levar para casa e me fez prometer que nunca mais faria aquilo de novo.

Faz quase 20 anos, mas de vez em quando ainda preciso me lembrar dessa promessa. Eu sei que deitar no meio da rua não é coisa que se faça. Mas coisas que não são coisas que se fazem me atraem quando estou num certo estado de espírito, que eu chamo de indisciplinado. Todos nós somos às vezes indisciplinados, mas essas manifestações ficam menos óbvias ao longo da vida. Com o tempo, paramos de esculpir pequenos retratos de giz de cera derretido. Quando alguém nos entrega um buquê, não comemos uma das flores. Desistimos de colecionar e fazer bolas com o cabelo que cai durante o banho. As primeiras duas coisas eu fazia, a terceira não — mas, quando conheci o cara que fazia bolas de cabelo, eu entendi. Um ano e pouco antes, em meu primeiro ano de faculdade, eu havia mandado meu cabelo pelos Correios para minha irmã de 6 anos. Eu acabara de cortá-lo e achei que ela pudesse querer para alguma coisa. Ela levou para um evento da escola, e seus professores ligaram para meus pais, perturbados. A irmã mais velha parecia ser uma má influência.

Filmes adolescentes têm como tema a indisciplina, mas também a deturpam como uma crítica à arbitrariedade ou à injustiça do statu quo. (“Esta é nossa hora de dançar!”) A rebeldia requer uma sofisticação, uma astúcia, que está uns passos à frente da mera indisciplina. Por exemplo, passei por um período, na adolescência, em que queria me tornar um mordomo. (Não se encontrava tão facilmente ficção de língua inglesa na Hungria, onde eu passava as férias, mas por algum motivo encontrei toda a obra de P.G. Wodehouse. Queria ser Jeeves quando crescesse.) Tenho uma outra irmã, dois anos mais nova do que eu, e me lembro deste como um dos momentos em que ela realmente transbordou de frustração comigo: “Você NÃO PODE ser um mordomo. Não existem mordomos mulheres!”. Se eu tivesse sido uma Jovem Feminista, talvez ela me admirasse. Mas ela sabia a verdade: eu estava surda ao sentido relevante de “não pode”. Rebeldia é uma negação determinada da ordem social. Indisciplina é a negação indeterminada.

Filmes disfarçam indisciplina de rebeldia porque estão no mercado do disfarce. E, encaremos os fatos, eu também. Estive a contar-lhe histórias. Histórias verdadeiras, mas, ainda assim, histórias. Mesmo que você estivesse um pouco enojado com o envio dos cabelos pelos Correios, eu calculo que você ficou do meu lado contra os professores do jardim de infância. Mas tenha isto em mente: você não sabe o que eu deixei de contar. Por exemplo, deixei de contar que não me preocupei em secar o cabelo depois de cortá-lo e antes de enviá-lo, e também que minha irmãzinha deixou-o no envelope por semanas antes de levar para a escola e o que ela apresentou para sua sala estava... mofado e nojento. O que não a incomodou de jeito nenhum. Mas talvez agora você comece a simpatizar com a dificuldade dos professores de consolar uma aluna do jardim de infância desesperada depois de insistirem em jogar no lixo essa pilha pútrida de cabelo humano. Ou talvez não, talvez você ainda esteja no Time dos Indisciplinados. Acho que agora, pensando bem, cabelos mofados também têm um charme.

Os filmes não são os culpados. Não conseguimos deixar de amenizar a indisciplina para o consumo de outros. Fingimos que é inspiradora — ou então, se inspiradora estiver indisponível, engraçada. A necessidade de disfarçar indisciplina ajuda bastante a explicar por que o humor é tão importante para nós.

Muitos adultos sofrem erupções de indisciplina por meio de acessos de fraqueza da vontade: nós não fazemos o que deveríamos estar fazendo, embora reconheçamos que seja muito importante. Às vezes, sentimos que não podemos fazer aquilo que, todavia, deveríamos fazer.

Indisciplina também se manifesta como insociabilidade. Aqui está um exemplo de um jantar de uma conferência à qual compareci há uns meses. A conferência em questão havia sido longa, o jantar veio ao final, e o episódio ocorreu no fim do jantar. Eu não aguentava mais socializar. Mas já havia ido ao banheiro mais vezes do que é socialmente aceitável, então sabia que apenas tinha de esperar até a sobremesa. Por algum tempo, a conversa havia sido sobre animais de estimação: compartilhando histórias sobre animais, discutindo que animais adotar no futuro etc. Meu vizinho à mesa, um amigo querido e um mentor, notou meu silêncio e me instigou a participar: “E você?”.

Eu disse: “Eu odeio animais não humanos”. Um silêncio instalou-se. Havia muitas coisas educadas e verdadeiras que eu poderia ter dito — por exemplo: “Sou alérgica a gatos e cachorros”. Isso teria sido bem recebido. Mas, na hora, as únicas palavras em que consegui pensar foram as que falei. Para minha sorte, a sobremesa chegou logo depois, e eu escapei.

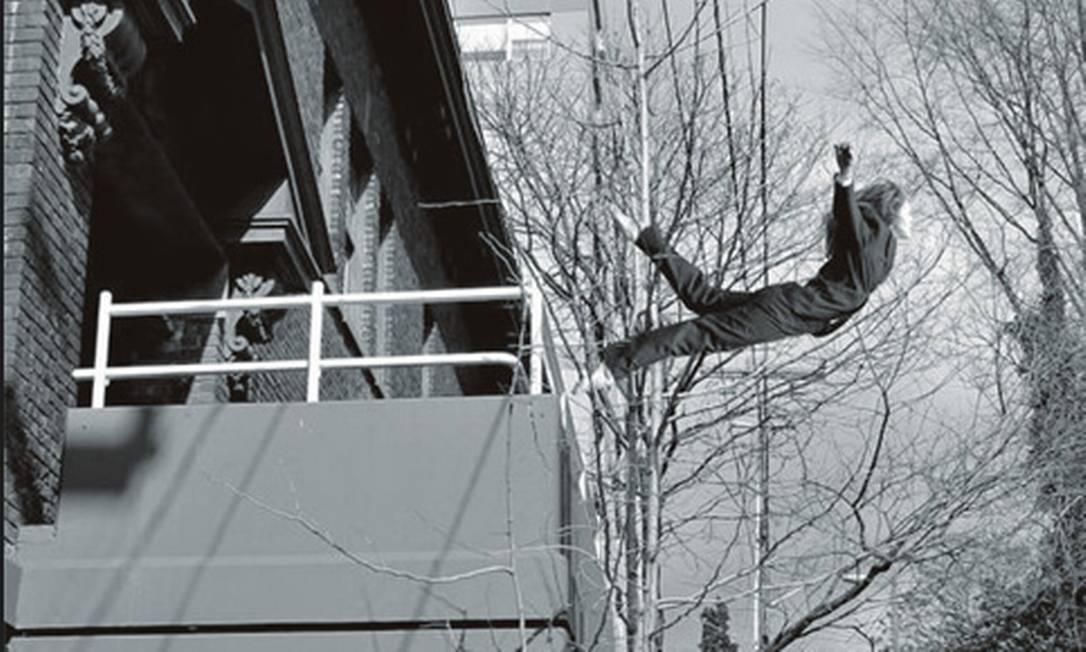

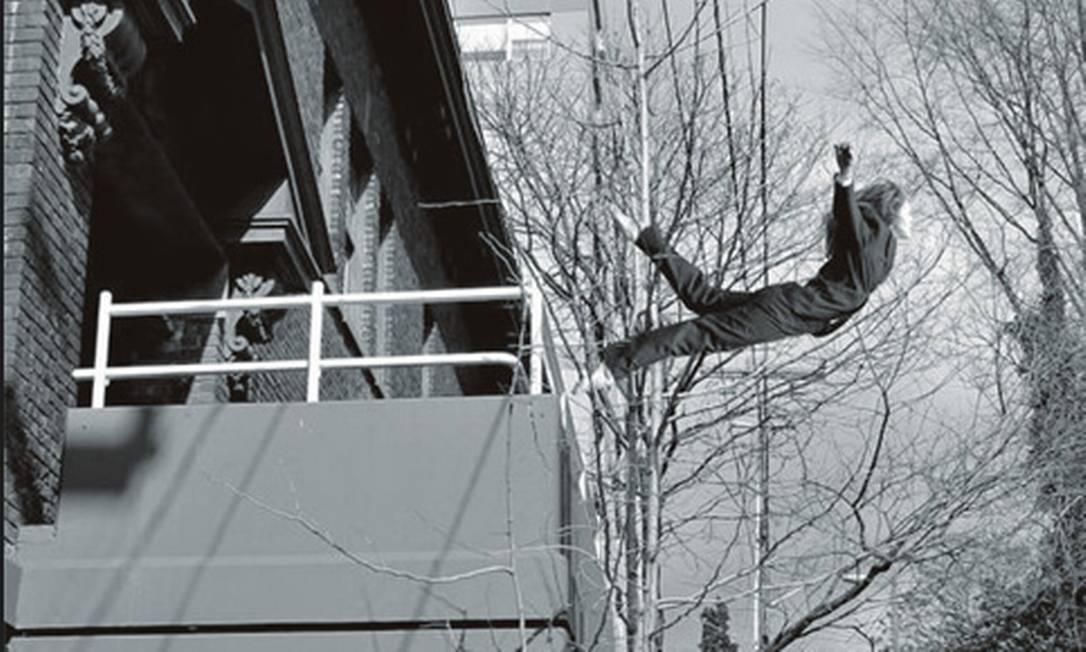

Nós, pessoas indisciplinadas, rejeitamos os princípios organizadores não só de nossa sociedade, mas de nossa própria vida. Afastamos com um tapa a mão estendida do amigo que quer nos integrar ao grupo. A autossegregação que se transforma em solidão miserável parece sem sentido ou, de forma equivalente, parece tratar a rejeição a coordenar com outros como se fosse valiosa para seu próprio bem. Igualmente intrigante é a rejeição a coordenar consigo mesmo, pois é isto que é a fraqueza da vontade: jogar pela janela nossos melhores planos, afastando com um tapa as mãos de nossos passado e futuro. Regras não são nada além de formas de coordenação através do tempo (consigo mesmo) e de pessoas (com outros). Tudo o que fazemos requer pelo menos uma dessas formas de coordenação, então indisciplina é uma rejeição da própria produtividade. É desertar a vida.

Por que agimos dessa maneira? Para que serve a indisciplina? Uma possibilidade é que não serve para nada, é apenas uma forma de autodestruição. Deixe-me oferecer uma visão mais otimista. Talvez uma função da indisciplina seja que ela nos oferece uma maneira de esperar. Pelo quê? Pelo clube ao qual vale a pena pertencer. Pelo eu que merece amor. Pelas regras que merecem ser seguidas. Indisciplina diz: “Não ame aquele com quem você está!”.

Se quisermos considerar a possibilidade de essa interpretação estar correta, não podemos, em nível conceitual, comparar a rejeição a um conjunto de regras com a aceitação a um outro, superior. Isso combinaria a indisciplina com a rebeldia. O rebelde é um guerreiro que tenta fazer com que nós sigamos aquilo que ele acha ser o conjunto de regras correto ou melhorado. Se a indisciplina existe, então é possível achar que algumas regras são falsas, restritas, farsantes, alienantes, em uma palavra, exógenas, sem conseguir apontar uma alternativa. Rebeldia tem um destino; indisciplina é emigrar sem ter para onde ir.

Primeiro, pessoalmente acho que indisciplina é uma caixinha de surpresas: já me levou a fazer coisas que são autodestrutivas, insensíveis ou apenas idiotas. Já me fez ser, às vezes, uma péssima irmã, amiga, filha, mãe, esposa. Uma péssima cidadã, inclusive. Mas também me levou a Sócrates. Vejo Sócrates como o filósofo da indisciplina. De certa forma, claro, todo filósofo é o filósofo da indisciplina — eles investigam as verdadeiras regras, em vez daquelas que por acaso seguimos. São cães de caça do necessário, do universal, das regras inescapáveis. Então, os filósofos estudam lógica, isto é, as regras que governam o pensamento, e estudam ética, as regras que governam nossas interações com os outros. O que faz de Sócrates o filósofo da indisciplina é que ele foi o primeiro e talvez o último a pensar que elas faziam parte do mesmo conjunto de regras. Ele nos mostrou uma atividade única e interpessoal que é governada pelas regras — um tipo específico de conversa.

Sócrates sugere que, quando a indisciplina levar embora, de forma prestativa, tudo na vida que é um mero acidente de cultura e costumes, tudo que é arbitrário ou mutável ou convencional, o que ficará será a investigação dialética. Se você e eu buscamos o significado da coragem, ou a natureza do conhecimento, ou os blocos de construção da realidade fundamentais, e o fazemos testando as declarações de outros ao tentar refutá-las, então estamos vivendo de forma autêntica. É certo que seremos fiéis a nós mesmos e que nosso compromisso com os outros será verdadeiro.

Sócrates foi mais longe ainda e elegeu a investigação como a única forma verdadeira de atividade política, a única forma de amizade, ou amor, ou conexão humana. Isso pode parecer extremo, mas tenha em mente este padrão: a proximidade socrática verdadeira impossibilita a sensação de estar fingindo ou apenas seguindo o fluxo. O encantamento da filosofia socrática, para mim, é encontrar algo que é à prova até de meus mais poderosos impulsos indisciplinados — a descoberta de um lugar onde não estar nem um pouco disposto a cooperar se torna um tipo de cooperação. E eu acho que não estou sozinha: muitas almas inquietas encontram um refúgio na discussão; na discordância; em se opor a algo e que outros se oponham a elas. Nós nos deleitamos com o alívio de não ter de nos esquivar de nossa indisciplina e com a oportunidade de poder aperfeiçoá-la.

*Agnes Callard é professora de filosofia da Universidade de Chicago e autora do livro Aspiration (Oxford University Press, 2018)

Automatic translation of a translation

Philosophy professor defines indiscipline as emigrating without a defined destination

Agnes Callard of the University of Chicago says many restless souls find refuge in disagreement

Agnes Callard*; Translated by Mariana Nântua

19/09/2018 - 08:00 / Updated on 09/19/2018 - 08:44

When I'm alone late at night on a deserted street, I like to walk over the double yellow lines. Once, I decided to stop and lie down, right there in the middle of the street. I kept myself tight, arms glued to my body, so that cars could pass on both sides. But I wasn't invisible, and I scared a kind policeman who drove past me. After determining that I wasn't dead, drunk, or high, he concluded that I had suicidal tendencies. We talked for a long time. It didn't help much when I explained that if I wanted to be run over, I would have moved a few meters in one direction or another. A busier street is chosen. He wanted to know why, if I didn't want to be run over, I was lying in the middle of the street.

There were many reasons. I wanted to see the sky from the perspective of the street; he wanted to stay in this secret place, which is always crossed, but never occupied; Most of all, I wanted to feel what it was like to lie there, with the double yellow lines stretching beneath me, from head to toe. But all of these reasons became non-reasons when I stated them out loud. He didn't know what to think of me, but he finally admitted that I didn't seem suicidal. He insisted on taking me home and made me promise that he would never do that again.

It's been almost 20 years, but every now and then I still need to remind myself of that promise. I know that lying down in the middle of the street is not something you do. But things that are not things that are done attract me when I am in a certain state of mind, which I call undisciplined. We are all sometimes undisciplined, but these manifestations become less obvious throughout life. Over time, we stopped sculpting small portraits from melted crayons. When someone hands us a bouquet, we don't eat one of the flowers. We gave up collecting and making balls with the hair that falls out during the shower. The first two things I did, the third I didn't — but when I met the guy who made hairballs, I understood. A year or so earlier, in my first year of college, I had mailed my hair to my 6-year-old sister. I had just cut it and I thought she might want it for something. She took it to a school event, and her teachers called my distraught parents. The older sister seemed to be a bad influence.

Teen films have indiscipline as their theme, but they also misrepresent it as a criticism of the arbitrariness or injustice of the status quo. "This is our time to dance!" Rebellion requires a sophistication, a cunning, which is a few steps ahead of mere indiscipline. For example, I went through a period in my adolescence when I wanted to become a butler. (English-language fiction was not so easily found in Hungary, where I spent my holidays, but for some reason I found all of P.G. Wodehouse's work. I wanted to be Jeeves when I grew up.) I have another sister, two years younger than me, and I remember this as one of the moments when she really overflowed with frustration with me: "You CAN'T be a butler. There are no female butlers!" If I had been a Young Feminist, maybe she would have admired me. But she knew the truth: I was deaf to the relevant meaning of "can't." Rebellion is a determined denial of the social order. Indiscipline is indeterminate denial.

Movies disguise indiscipline as rebellion because they are in the disguise market. And, let's face it, so do I. I've been telling him stories. True stories, but stories nonetheless. Even if you were a little disgusted with the mailing of the hairs, I reckon you sided with me against the kindergarten teachers. But keep this in mind: you don't know what I failed to tell. For example, I failed to tell you that I didn't bother to dry my hair after cutting it and before sending it in, and also that my little sister left it in the envelope for weeks before taking it to school and what she presented to her class was... Musty and disgusting. Which didn't bother her at all. But maybe now you'll start to sympathize with teachers' difficulty in comforting a desperate kindergartner, after they insisted on throwing this putrid pile of human hair in the trash. Or maybe not, maybe you're still on the Unruly Team. I think now, come to think of it, moldy hair also has a charm.

Movies are not to blame. We cannot help but alleviate indiscipline for the consumption of others. We pretend it's inspiring—or if it's unavailable, funny. The need to disguise indiscipline goes a long way toward explaining why humor is so important to us.

Many adults suffer eruptions of indiscipline through bouts of weakness of will: we don't do what we should be doing, even though we recognize that it is very important. Sometimes we feel that we cannot do what we should do.

Indiscipline also manifests itself as unsociability. Here's an example of a dinner from a conference I attended a few months ago. The conference in question had been long, dinner came to an end, and the episode took place at the end of dinner. I couldn't stand socializing anymore. But she had been to the bathroom more times than is socially acceptable, so she knew she just had to wait until dessert. For some time, the conversation had been about pets: sharing stories about animals, discussing what animals to adopt in the future, etc. My neighbor at the table, a dear friend and mentor, noticed my silence and urged me to participate: "What about you?"

I said, "I hate nonhuman animals." A silence settled. There were many polite and truthful things I could have said—for example, "I'm allergic to cats and dogs." That would have been well received. But at the time, the only words I could think of were the ones I spoke. Lucky for me, dessert arrived soon after, and I escaped.

We undisciplined people reject the organizing principles not only of our society, but of our own life. We slap away the outstretched hand of the friend who wants to integrate us into the group. Self-segregation that turns into miserable loneliness seems meaningless or, equivalently, seems to treat rejection to coordinate with others as if it were valuable for its own good. Equally intriguing is the refusal to coordinate with oneself, for this is what the weakness of the will is: to throw our best plans out the window, slapping our hands away from our past and future. Rules are nothing but forms of coordination across time (with oneself) and people (with others). Everything we do requires at least one of these forms of coordination, so indiscipline is a rejection of productivity itself. It is deserting life.

Why do we act this way? What is indiscipline for? One possibility is that it serves no purpose, it is just a form of self-destruction. Let me offer a more optimistic view. Perhaps one function of indiscipline is that it offers us a way to wait. For what? For the club to which it is worth belonging. For the self that deserves love. For the rules that deserve to be followed. Indiscipline says: "Don't love the one you're with!".

If we want to consider the possibility that this interpretation is correct, we cannot, at the conceptual level, compare the rejection of one set of rules with the acceptance of another, higher one. This would combine indiscipline with rebellion. The rebel is a warrior who tries to get us to follow what he thinks is the correct or improved set of rules. If indiscipline exists, then it is possible to think that some rules are false, restricted, farcical, alienating, in a word, exogenous, without being able to point out an alternative. Rebellion has a destiny; Indiscipline is emigrating with nowhere to go.

First, I personally think that indiscipline is a box of surprises: it has led me to do things that are self-destructive, insensitive or just stupid. It has made me be, at times, a bad sister, friend, daughter, mother, wife. A bad citizen, by the way. But it also led me to Socrates. I see Socrates as the philosopher of indiscipline. In a way, of course, every philosopher is the philosopher of indiscipline — they investigate the true rules, rather than the ones we happen to follow. They are hunting dogs of the necessary, of the universal, of the inescapable rules. So philosophers study logic, that is, the rules that govern thought, and they study ethics, the rules that govern our interactions with others. What makes Socrates the philosopher of indiscipline is that he was the first and perhaps the last to think that they were part of the same set of rules. He showed us a unique, interpersonal activity that is governed by rules—a specific type of conversation.

Socrates suggests that when indiscipline helpfully takes away everything in life that is a mere accident of culture and customs, everything that is arbitrary or changeable or conventional, what will remain is dialectical investigation. If you and I seek the meaning of courage, or the nature of knowledge, or the fundamental building blocks of reality, and we do so by testing the claims of others by trying to refute them, then we are living authentically. It is certain that we will be true to ourselves and that our commitment to others will be true.

Socrates went even further and chose research as the only true form of political activity, the only form of friendship, or love, or human connection. This may sound extreme, but keep this pattern in mind: true Socratic closeness makes it impossible to feel like you're faking it or just going with the flow. The enchantment of Socratic philosophy, for me, is to find something that is proof against even my most powerful undisciplined impulses—the discovery of a place where not being at all willing to cooperate becomes a kind of cooperation. And I think I am not alone: many restless souls find a refuge in discussion; in disagreement; to oppose something and for others to oppose them. We revel in the relief of not having to shy away from our indiscipline and the opportunity to be able to perfect it.

Agnes Callard is a professor of philosophy at the University of Chicago and author of the book Aspiration (Oxford University Press, 2018)

O Globo, a national newspaper: Stay on top of the evolution of the most read newspaper in Brazil

<www.oglobo.globo.com/epoca/professora-de-filosofia-define-indisciplina-como-emigrar-sem-destino-definido-23080137>