Bron Taylor

Rebels against the Anthropocene?

Ideology, Spirituality, Popular Culture, and Human Domination of the World within the Disney Empire

2019

Popular Culture, Religion, and the Anthropocene

Walt Disney and the Anthropocene

Disney’s Subversive Filmmaking

The Animal Kingdom…from the Tree of Life to Africa

Abstract

There is no scientific consensus whether a new epoch labeled the Anthropocene should be declared and, if so, when it started. Yet the basic idea can be helpful and provocatively stated: The Anthropocene is that period in Earth’s history traceable to when Homo sapiens began subjugating and expropriating for its own use the world’s organisms and ecosystems. Given this understanding it may be possible to illuminate how ‘religion’ and ‘popular culture’ are entangled with these anthropogenic processes. The creative productions and commercial enterprises launched by Walt Disney and his corporation, reflect, express, and promote diverse understandings of the human domination of the world and those peoples often understood to have beneficent, spiritual relations with nature. Analyzing understandings, contentions, and trends that are found under Disney’s umbrella shows how it reflects and promotes diverse cultural understandings, including religious ones, about the proper relationships between human beings and their various environments. Such analysis also shows that significant changes are unfolding and that some of Disney’s creatives are among a growing chorus of rebels against the Anthropocene.

Keywords

Walt Disney, popular culture, Anthropocene, Disneyland, Magic Kingdom, animation, EPCOT, animal kingdom, manifest destiny, nature spirituality, Dark Green Religion

Introduction

In 1998, I attended the American Academy of Religion Conference in Orlando, Florida, the city which is well known globally as the site of Walt Disney World. By coincidence, the conference coincided with the opening on Earth Day (April 22) of Disney’s Animal Kingdom, a brand new theme park. I was curious whether and if so, how, religion, animals, and their habitats might be interpreted there, so I asked several colleagues whom I thought had similar interests if they would be interested in going. They all declined, explaining similarly that they did not want to support the Disney Corporation because it promotes unbridled capitalism, consumerism, and ecocide.

As an observer of academic subcultures I was unsurprised by such critiques, which I later found well summarized Adrian Ivakhiv:

Disney has often been criticized as shaping the cultural landscape in profoundly conservative directions…for presenting a sentimentalized and distorted view of animal lives and ecological realities, and for projecting middle-class American values—or, in some interpretations, racist, classist, and hierarchic or even neo-monarchist values—onto the natural world (2013: 216).[1]

I was, however, surprised that avowed religion and nature scholars, who recognized the power of Disney to influence biophysical systems, were uninterested in an opportunity to analyze the Animal Kingdom. I wondered if their reactions might reflect a leftist observer bias, which like all such bias, can lead to misapprehensions. As a scholar who tries to guard against this dynamic, when I set out to explore the Animal Kingdom, I sought to set aside my own preconceptions while analyzing this new theme park.

A number of years later, based in part on that visit, I argued (Taylor 2005) that the ideologies and spiritualities Disney has expressed and promoted over the years have been plural, in transition, and contested— just like the culture in which Disney’s worlds are situated. This ultimately Durkheimian assumption about the ways human perceptions and values, religious and otherwise, tend to reflect the cultures people live in, combined with the ultimately Weberian assumption that sometimes religious ideas decisively change the cultures from which they emerge, has animated my interest in the ways Disney’s ‘cultural creatives’ might both kindle social change and change with the times.[2] And in the decades since I first visited the Animal Kingdom, I have wondered as well whether increasing alarm about anthropogenic environmental change might be visible at Disney, and if so, whether this would not only reflect but influence the times. Such questions are especially apropos given the ferment over whether human behavior has so profoundly changed Earth’s environmental systems that a new epoch, the Anthropocene, should be declared.

Herein I take up these questions with special attention to the ideological, spiritual, ethical, and environmental dimensions of Disney’s cultural productions. More specifically, I have sought to understand whether these productions are enthusiastic, optimistic, or critical about the monumental changes that the Anthropocene term was created to emphasize. Put simply, herein I explore whether Disney’s cultural creatives embrace or are rebels against the Anthropocene.

Popular Culture, Religion, and the Anthropocene

Before turning to the evidence and findings about what the Walt Disney Company has to do with popular culture, religion, and the Anthropocene, it is important to clarify these terms.

The notion of popular culture refers to artistic and other productions that are widely appreciated and consumed by the public at large—not by relatively small subsets of a society, such as cultural elites or those in ethnic, religious, or other enclaves. Although the boundaries that demarcate popular culture may be difficult to discern, it is a useful concept. As a media and entertainment empire emerging and spreading globally from the United States, which has great appeal for mass publics and ordinary people,[3] Disney’s films, music, and theme parks provide archetypal examples of cultural productions that fit common understandings of popular culture.

The term ‘religion’ requires more unpacking, especially when examining phenomena that some observers may not recognize as religious. As is the case with popular culture, determining where religion begins and ends is difficult. It would be simple to assume that religion necessarily involves beliefs and perceptions related to non-material divine beings or supernatural forces. I do not make such an assumption, however, because it omits a wide variety of social phenomena that have typically been understood to be religious. Instead, I take what many scholars call the ‘family resemblances’ approach to the study of religion, which involves analyzing a wide array of traits and characteristics that are typically associated with religious perceptions and practices without trying to establish a strict boundary between what counts as religion and what does not (Saler 1993, 2008).[4] This approach has the analytic advantage of being able to consider as similar social phenomena that some distinguish as ‘religious’ and ‘spiritual’. With the family resemblance approach, this commonly made distinction, that religion is organized and institutional and involves supernatural beings while spirituality is individualistic and concerned with the quest for meaning, personal transformation, and healing, is not particularly valuable because both share most if not all of the same characteristics. A family resemblance approach to religion-resembling social phenomena can be illuminating even if one elects not to label given social phenomena as religious. As with notions like ‘religion’ and ‘popular culture’, defining and demarcating the boundaries of what has been termed ‘the Anthropocene’ is difficult and consensus is elusive. The Anthropocene is a neologism for a proposal and argument, first advanced in 2000 by Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer (Crutzen and Stoermer 2000; Crutzen 2002a, 2002b), that a new geological epoch, the Anthropocene, should be declared to follow the Holocene Epoch, which itself supplanted the Pleistocene Epoch approximately 12,000 years ago. The Holocene has been characterized by the relatively stable climate that has been congenial to the emergence of agriculture, and the concomitant expansion and spread of human populations around the world. The central rationale behind the proposal is that a new epoch would properly acknowledge that humanity has decisively changed Earth environmental systems. Put starkly, the Anthropocene refers to an epoch in which, in irreversible ways, humanity subjugated and expropriated for its own use the vast majority of the world’s terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, and their processes and organisms.[5]

The scientific body that has responsibility for demarcating Earth’s chronology is the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS). It established an Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) to consider whether the proposal had merit and, if so, what criteria and chronology should mark the new Epoch. Although there has been disagreement within the AWG and far more beyond it, in 2019 its majority agreed that it made sense to declare an Anthropocene Epoch and date it to the mid-twentieth century, when the atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons and innovative chemistry, through ordinary environmental processes, spread many anthropogenic molecules over the entire planet. Increasingly influential, as well, for those arguing for a mid-twentieth-century dating, is ‘the great acceleration’ of anthropogenic environmental change since 1945, in which rapidly increasing human numbers and technological innovations intensified many of the environmentally destructive practices that had already dramatically changed the Earth system (McNeill and Engelke 2014; Steffen et al. 2015). By 2019, however, the AWG decided that stratigraphic evidence of the global spread of radioactive fallout was an especially important chronological marker, although no formal declaration will be issued before 2020, if ever. This may be, in part, because of significant and diverse criticisms of the Anthropocene notion itself, of the evaluative criteria deployed by the AWG, and even of the philosophical presuppositions underlying its efforts.[6]

The foremost problem with dating the Anthropocene in the midtwentieth century, however, is clear evidence that the anthropogenic alteration of the Earth system began far earlier. For many, myself included, this suggests that if it makes sense to demarcate an Anthropocene Epoch, it would best be understood as a long process that has been unfolding for tens of thousands of years. Indeed, profound anthropogenic environmental change can be traced as far back as the Late Pleistocene (30,000–100,000 BP). This was a period in which there were still several Homo species. These hominids domesticated fire and used it to change the landscape in ways that provided preferred vegetation to gather and animals to hunt, and it was also advantageous in the preparation of both mora and fauna for food. Even before Homo sapiens had driven other Homo species to extinction (the weight of evidence is that our own species did just that), by the end of the Pleistocene, early humans were already colonizing Earth and widely changing ecosystems. They did so not only by driving many species to extinction and by extirpating species from many regions, but by burning vegetation. Sometimes (intentionally and not) they also changed ecosystems by moving species into new habitats, displacing or reducing populations of endemic ones. In these and other ways, humankind had already dramatically transformed many of Earth’s ecosystems (and even Earth’s sediments) well before the Neolithic (agricultural) revolution.[7] Of course, the transformation of the Earth system by humans intensified with the Neolithic revolution, which began about 9,500 BP, with the rate of expansion increasing from about 9,000 BP. The Neolithic revolution continued many of the processes that had begun during the Late Pleistocene, but agricultural peoples added behaviors that had even greater environmental impacts: extensive deforestation to clear land and build settlements, and the domestication of many plant and animal species combined with intensive killing or displacement of organisms that threatened these domesticates. Agricultures spread through most of Eurasia by about 3,000 BP; they had also been established independently on all continents except Antarctica by this time, with different species being domesticated on different continents and at various times (Diamond 1997, 2005; Harari 2015).[8] Early during the Neolithic, increasing populations of domesticated animals raised as livestock even changed atmospheric chemistry by increasing concentrations of carbon dioxide and methane (Fuller et al. 2011; Kaplan et al. 2010). The revolution’s environmental impacts grew all the more rapidly through European imperialism, which also had a profound ecological dimension as scores of organisms were moved around the world (Crosby 1986). The transformation of the earth’s land, waters, and living systems accelerated even more rapidly with the industrial revolution. Some scientists trace the Anthropocene to this period and the profound transformations initiated by the invention of the coal-fueled steam engine in 1785, and to the further intensification a century later that accompanied the invention of the internal combustion engine and humankind’s new-found ability to pump liquid petroleum from the ground. This anthropogenic transformation not only decisively changed the atmosphere and climate, but it further eroded biological diversity. Regardless of whether one concludes that the Anthropocene should be declared, and if so, to what time it should be traced, the ferment over the term has valuably focused attention on the role of Homo sapiens in changing Earth’s living systems. The critical dynamic this illuminates for the present purpose, namely, framing a discussion of the Disney Corporation’s entanglements with ideologies and spiritualities related to nature, is this: the millennia-long process of anthropogenic change represents a long trend toward biological and cultural homogenization.[9] Moreover, this process also led to religious homogenization, as small-scale societies (which have often involved animistic perceptions) were overrun by the world’s predominant religions (Mason 1993; Shepard 1998). These so-called ‘world religions’ generally considered themselves to be superior to the ones they converted or exterminated, which helped to justify the very processes by which they, and the larger and more powerful societies in which they were situated, supplanted the smaller ones.

Walt Disney and the Anthropocene[10]

Although my primary focus is on Disney’s cultural productions that are especially relevant to religion and the Anthropocene, I will start with a brief introduction to Walt Disney (1901–1966). He was, of course, the driving creative force behind the film and entertainment empire that bears his name, but his brother, Roy Disney (1893–1971), deserves mention as well; as the company’s fiscal and organizational manager he made his own decisive contributions. This said, Walt Disney was clearly the leader of the company and his prominence, and the company’s economic power, began with the animated short he conceived of and orchestrated, which starred Mickey Mouse. The first film featuring the charismatic rodent was released as Steamboat Willie in 1928.[11] It was soon followed by other popular animated shorts, and, subsequently, by a host of enthusiastically received and profitable animated and feature films, beginning with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). A deal to produce television programs, which began airing in 1954, provided funding for Disneyland, which opened in July 1955 in Anaheim, California. Walt Disney World later opened in 1971 in Orlando, Florida; Disney theme parks followed in Japan, China, and France, and the film division and resort business boomed.

Many books and two motion pictures have sought to understand Walt Disney.[12] Some are hagiographic and focused on the obstacles he faced and his creative and entrepreneurial achievements. Others contend he must be understood, like many white men of his time, as sexist and racist, or at least, as insensitive in this regard. Still others have cast him as an anti-Semite, a fascist, or even as a Nazi sympathizer (based largely on his attendance at a meeting of a putatively pro-Nazi organization before WWII); or criticize his anti-labor views, evidenced by his disputes with his own workers and his willing participation in the anti-communist fervor that riled the nation, and Hollywood, after WWII.

Others depict Walt Disney as a complicated and conflicted man: that although he expressed many of the biases of his time, as exemplified by his enforcing of dress and grooming codes and by forbidding same-sex dancing at Disneyland during the 1960s, he was kind to individuals of diverse backgrounds. He also recognized maws in American history while, at the same time, he downplayed them, promoting an idyllic vision of America—its land, people, settlements, political system, ingenuity, leadership, and future.

It is beyond the present purpose to arbitrate the divergent portraits of Walt Disney, apart from noting that the most judicious biographies note his maws but dispute the harshest judgments made about him (Watts 1997; Gabler 2006).[13] What few dispute is the influence that growing up on a farm in Missouri and in a strict Protestant Christian home had upon him. Arguably, both contributed to two assumptions Disney shared with many Americans of his time. First, and echoing Genesis, by divine provenance humans are in charge of the world and here to improve it. Second, just as the Hebrew people were chosen by God to be a light shining as a moral example to the nations (a notion grounded in the original Covenant with Abraham and expressed multiple times in the Hebrew Bible and Christian New Testament), so were Americans (according to John Winthrop and the Puritans) to be a city shining on a hill for all the world to see, value, and emulate (Miller 1956). In sum, it might be best to understand the mature Walt Disney (after 1950) as a nationalist who combined political and economic conservatism with respect for the putatively democratic and egalitarian ideals of the nation. Thereby, he expressed and promoted the ‘we feeling’ that is essential to patriotism and combined it with an appreciation for the diversity and beauties of the land, including its diverse geographies, ecosystems, mora, and fauna. This contributed as well to the ‘place feeling’ that is the second pillar typical of patriotism.[14] And there is no doubt that Walt Disney thought that the best of American ideals were salutary models that the world should follow. Whatever disputes there may be about the man who founded the Disney entertainment empire he has obviously had a huge influence on and beyond American popular culture, often to the consternation of those who see Disney as a force of cultural homogenization and thus, of American cultural imperialism.[15] This biographical backdrop sets the stage for my inquiry into the ways that perceptions and values related to religion, popular culture, and what many call the Anthropocene, have been contested, entangled, and changed within Disney’s Worlds.

Disneyland & Main Street USA

I begin this focus with Disneyland. I know the place better than most because I was born the year it opened and grew up in Southern California. I went to Disneyland several times as a youngster, and then, between the ages of 13 and 16, I visited the park several more times due to an incentive program provided to newspaper carriers who recruited new subscribers.[16]

Visitors to Disneyland and later Disney Theme Parks enter through its gates to ‘Main Street USA’, where visitors encounter an idyllic image of the United States, depicted implicitly as a sacred place characterized by community and prosperity. I recall well that the Opera House on Main Street presented Great Moments with Abraham Lincoln, who appeared as an animatronic robot extolling on the ideals of the Republic. The attraction, which opened in 1965 and continued for decades with few changes, expressed a message that cohered with early Puritan understandings of America as a new promised land, whose sacredness depends not only on divine creativity but on righteous human labor. Indeed, the presentation exemplified the civil religion thesis, expressing and promoting the we and place feeling essential to religious nationalism. Lincoln, of course, is one of the preeminent saints of this nationalistic cult, and Walt Disney held him in particularly high esteem. In the narrative preceding Lincoln’s talk, for example, choral music accompanied the robotic president as he rose from his chair, and the narrator intoned that Lincoln had sacrificed himself, messiah-like, for the survival of the nation.

The heart of Lincoln’s presentation was excerpted from various speeches. It began with a discussion of how ‘God has planted in our bosoms’ a ‘love of liberty’, which is ‘the heritage of all men, in all lands everywhere’. Yet, Lincoln warned, liberty must be defended against despotism and inculcated in the American people:

Let reverence for the law be breathed by every American mother. Let it be taught in the schools, in the seminaries, and in the colleges and preached from the pulpit, proclaimed in legislative halls, and enforced in courts of justice. And in short, let it become the political religion of the nation; and let the old and the young, the rich and the poor, the grave and the gay of all sexes and tongues and colors and conditions, sacrifice unceasingly at its altars.[17]

With these words Lincoln had expressed the central idea behind what, a century later, the sociologist Robert Bellah (drawing on Emile Durkheim) would famously label ‘civil religion’, namely, the conviction that the nation was established by divine providence and had a responsibility to ensure social stability, freedom, community, and prosperity (Durkheim 1965 [1912]; Bellah 1967, 1975). Bellah also thought that civil religion, which Lincoln presaged by calling for a political religion, could provide ideals that the nation should uphold. As the refrain from The Battle Hymn of the Republic played and increased in volume, providing a stirring crescendo, Lincoln concluded his speech, stressing that citizens have a duty to God and the Republic:

Let us strive to deserve, as far as mortals may, the continued care of Divine Providence. Trusting that, in future national emergencies, He will not fail to provide us the instruments of safety and security… Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.

Although the speech mentioned ‘all sexes and tongues and colors’ and stressed that tyranny must be resisted, that Lincoln’s battle was also against slavery was only subtly acknowledged: During his preliminary remarks, Lincoln modestly mentioned that his public life was well known, and the Gettysburg Address was available to read in the Opera House’s foyer. But as is generally the case under the Disney umbrella, the dark side of the nation’s history, while acknowledged, was downplayed, the full horror and tragedy obscured and viewed merely as one of the many obstacles on the way toward the establishment of justice and civic virtue. Here in the Opera House, and throughout the park, the central message was that Americans had a God-given duty to control, use, develop, and defend the republic as a sacred and utopian political space.

This space, however, had long been occupied by Native American peoples before the arrival of the supposedly freedom-loving Europeans. The desired freedom of the European immigrants in fact collided with the liberty of the continent’s first peoples, and consequently, the new nation would not be established without a fight. At Disneyland, this part of the story was presented in Adventureland and Frontierland, while on Disney-produced television programs, the American continent was presented as an exciting and dangerous place full of Indians and Pirates, all of whom must give way to the advancing, largely white, and Christian civilization.

Frontierland

As a child, like many youngsters of my generation (perhaps especially those of European ancestry), I especially enjoyed Frontierland. There we would play on Tom Sawyer Island and mount the parapets at Fort Wilderness, where one could shoot imagined Indians who were paddling Indian War Canoes (which in 1971 were replaced by Davy Crockett’s Explorer Canoes). A brochure, map, and photographs from the early years explained that the fort overlooked ‘A vast, untamed, American Wilderness’, replete with friendly Indians (who had capitulated to the invading settlers) and hostile Indians (who did not). From these canoes, visitors could see that the ‘treacherous’ hostile ones had burnt a ‘settlers cabin’; on the ground in front of it lay the unfortunate interloper, face up, with an arrow in his chest.[18]

This scenario referred to and drew directly on a series of highly popular Davy Crockett television programs, which Disney began airing in late 1954. The first was titled Indian Fighter, the second, Davy Crockett Goes to Congress, the third, Davy Crockett at the Alamo. This trilogy ran periodically on network television until 1974; a version that combined them into a feature-length film was given theatrical release in 1955, titled Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier. It aired as late as 1993.[19] These films led to a socially influential, decades-long Davy Crocket craze. The storyline is telling.

In the first tale Crockett and his sidekick George Russell volunteered to serve as scouts for then General (and future President) Andrew Jackson, who was fighting Creek Indians who had not capitulated to the white settlers and accepted their proposed resettlement treaty. The Indians, according to this film, had been unjustly raiding settler encampments—the lyrics in a ballad woven into the film stated that the Indians were ‘burning at a devil’s pace’ these settlements, so Crockett was ‘tracking the redskins down’. Crockett and his comrades killed many Indians (in a strikingly nonchalant way). Eventually, Chief Redstick’s band snuck up, captured Russell, and began preparing to torture him. Crockett then appeared, and after calling out, ‘Creek Warriors, hear me’, he killed the first Indian who attacked him by throwing a knife into his chest. Then, after Redstick invited Crockett to speak, Crockett acknowledged their bravery but asserted that by refusing to join the Indians who had capitulated they were being unreasonable. Then he appealed to them, ‘I ain’t a soldier, I’m a settler, I’m a hunter like you’. Redstick scoffed, noting that Crockett hunted Indians. To this, Crockett replied, ‘only because you made war on us. Your smart chiefs gave up because they found out that war is no good’. He added that all Redstick’s warriors were going to die because he was a bad chief. Redstick bristled with anger to which Crockett offered that they could all go home in peace ‘if you’d just listen to reason. But seeings you won’t, I recon I’ll have to challenge you according to enjun law’. Crockett added the claim that the Indians would like white man’s law ‘if they’d give it half a chance’. Redstick and Crockett then faced off with tomahawks, according to this supposed Indian method of solving disputes. After Crockett prevailed, he chose to spare Redstick’s life. Redstick was incredulous and asked Crockett why, to which Crockett replied, implicitly invoking his God, ‘Maybe because of another law. We have trouble living up to it. It ain’t bad for red man or white man alike, “thou shalt not kill”’. Crockett also stated, after Redstick said he did not trust white men, that his word was his bond and he was giving his word that they’ll keep the peace. In response, Redstick freed Russell and hesitantly shook Crockett’s hand, symbolizing the peace and the man-to-man respect that had been forged between these fellow warriors. The ballad’s stanzas at the end of Indian Fighter declared that, for the rest of his life, Davy Crockett took a stand to guarantee ‘that justice was due every redskin band’.

After the Creek Indian wars ended, in the second film, ‘Davy Crockett goes to Washington’, Crockett moved to Tennessee with his family and Russell. Before the move he and Russell scouted and selected their new home, after viewing a bucolic scene in which several bears frolicked in a pristine river. Throughout these films Crockett was depicted as a skilled hunter with a special connection to the land. (Yet his legend also included that he killed his first bear as a three year old and over a hundred more bears during the course of his life.)

After their move to Tennessee, Crockett and Russell set about taming the land and building a homestead. But soon he agreed to become a magistrate because some lawless white men were stealing land from Indians who were entitled to it by a treaty. Then, after a stint in the Tennessee legislature, Crockett was elected to Congress, a political move championed by Andrew Jackson, the general under whom he served in the earlier Indian wars. Jackson, who was also a slaveholder and an anti-abolitionist, had, by then, been elected President. Crockett opposed Jackson’s Indian Removal Act (1830). In the film, he argued before Congress ‘sure we got to grow and expand, and that is no excuse to violate a sacred treaty. And you won’t do settlers no good either’. He added (to applause by congressmen in the film) that we need to be the kind of people ‘the good Lord wanted us to be’. But in real life, Jackson got his Act and the Indians got the infamous and genocidal Trail of Tears. Combined with the longstanding policy in the United States involving forced assimilation and conversion to Christianity, many of America’s native societies were annihilated, whilst the rest lost most of their land and much if not all of their traditional cultures.

In the third segment, having lost his wife to disease and with his children living with her family out east, Crockett and Russell set off to Texas, looking for land and freedom. After avoiding hostile Indians they ended up taking a stand at the Alamo with other new settlers against General Santa Ana and the Mexican Army, which were depicted as invaders. There at the Alamo, Crockett, Russell, and their comrades heroically perished. Facing death on his final night on Earth, Crocket sang this melancholy song:

Farewell to the mountains | whose mazes to me were more beautiful by far than Eden could be | the home I redeem | from the savage and wild | the home I have loved | as a father his child. The wife of my bosom I farewell to ye all | in the land of the stranger I rise or I fall.

The final chorus of the film’s recurring ballad concluded, ‘Davy, Davy Crocket, Fighting for liberty!’, as the words ‘March 6, 1836—Liberty and Independence forever!’ mashed across the screen.

The story thus portrayed the land as sublime and the taming of its wildlands, wild creatures, as well as its first peoples, as representing an inevitable step toward freedom, civilization, and self-rule (at least by and for white men). Disney’s empire sometimes expressed ambivalence about this process, periodically acknowledging that it was often bloody and tragic. But in the early years at least, it also blamed the victims: if only the Indians had more quickly listened to reason and accepted as superior European peoples and their customs, laws, and agricultural lifeways, the progress could have been quicker and with fewer casualties. What is clear is that these films and Frontierland itself expressed and promoted the idea that Europeans had a divinely sanctioned obligation to tame nature and establish a democratic and at least Christianity-influenced civilization across the North American landscape. In 1845 the newspaper editor John O’Sullivan coined the term ‘manifest destiny’ to capture and defend this process. The term aptly expressed the religion infused ideology and rationale for expansion that is common in settler societies.

The America of the 1950s, however, would soon experience great social upheavals, which would challenge such understandings of US history and change the perspectives of many, including those involved in Disney productions of all sorts. The changes to follow were, no doubt, in part because of harsh criticisms that Disney and its productions promoted bigotry, stereotypes, and sanitized histories.

One of the most telling examples of these changes could be seen at Frontierland’s settler’s cabin. By the late 1960s, in the wake of the civil and Native American rights movements, visitors no longer saw that treacherous Indians had burnt the settler’s cabin, but rather, evil river pirates. By the 1980s (perhaps after objections from river pirates) the story changed again: moonshiners had taken over the cabin and they had accidentally burnt it down themselves. In the 1990s, a careless settler torched his own cabin, endangering an adjacent eagles’ nest, thus adding an environmental twist to the story. Over the same period, the three Davy Crockett television episodes fell out of favor, no doubt due at least in part to their depiction of history and American Indians.

Fantasyland

At the center of Disneyland is Fantasyland, which structurally and symbolically connects European with US culture. Its entrance is Sleeping Beauty’s Castle, right at the end of Main Street. The fanciful castle was modeled after Neuschwanstein, which was built in Bavaria by ‘mad’ King Ludwig II. Towering nearby is a replica of Switzerland’s Matterhorn; from near its peak visitors could plunge in bobsleds to its base. As children we would be on high alert as we anticipated our first glimpse of Disneyland, which was this Matterhorn replica. For us, it was a kind of sacred mountain.

Fantasyland’s attractions drew on European folk tales and most also were made into feature-length films, including Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), Pinocchio (1940), Cinderella (1950), Alice in Wonderland (1951), Peter Pan (1953), and Sleeping Beauty (1959). Fantasyland and these films both reflected and reinforced the nation’s prevalent Eurocentrism. Despite its European heart, from its opening to the present, from 1966 Fantasyland also included an attraction in which children from diverse cultures around the world happily sang its signature song, for which it was also named, ‘It’s a Small World’. This message, of course, would be at odds with any notion of manifest destiny or even of cultural or religious hegemony, because it explicitly promoted and expressed a hope for a harmonious and culturally diverse world. Even the world’s diverse animals were represented, sculpted into the attraction’s landscape plants.[20] Some critics would likely argue that the respect for biological and cultural diversity represented in this attraction should be understood as the ultimate fantasy, betrayed by the ways Disney presents homologized stereotypes of cultures and a consumer culture that contributes to the erosion of biological diversity.

Tomorrowland

American culture during the 1960s entered a period of profound social disruption and change, fueled especially by resistance to the Vietnam War, the civil rights movement, growing critiques of inequality, ecological concerns, and a concomitant rejection of materialistic consumerism, all of which eroded the power of the nation’s civil religion to promote social cohesion. Within this cultural ferment, regret grew about injustices toward Native and African Americans, and as a result of these trends, many aspects of Disney’s filmmaking and theme parks began to change. Although America’s patriotic self-conldence had been shaken, however, another characteristic of the nation was little chastened and assumed greater importance: faith in technological progress and a corresponding hope in an America-led innovative, and even utopian, future. This has been nowhere more obvious than at Disneyland’s Tomorrowland, which was replicated at subsequent Disney theme parks and especially at EPCOT, which would later be constructed at Walt Disney World in Florida.

At Tomorrowland, Disney secured corporate sponsors for all its attractions, unabashedly cheerleading their leadership toward the envisioned utopia. Nowhere was this theme more obvious than at oil giant Chevron’s Autopia—the attraction’s name fused automobile and utopia—and there, children drove pint-sized cars. The attraction served as a rite of passage into car culture for millions of Americans, and indeed, it introduced them to the notion that freedom and progress go hand in hand—with hands on the steering wheel.

Immediately adjacent to Autopia was the General Electric-sponsored Carousel of Progress, in which a middle-class family’s father, surrounded by his wife and children, narrated the technological innovations that occurred throughout the twentieth century. According to its presentation, these innovations made life easier and reinforced domestic tranquility and happiness. As audiences slowly spun around to successive stages, representing different time periods, a song proclaimed ‘There’s a great big beautiful tomorrow | Shining at the end of every day’, noting optimistically that all this was ‘only a dream away’.

At Tomorrowland, such progress has been tethered to a fascination and revelry in nature as known by the sciences, including especially the control and manipulation of nature by science, all in the service of the celebrated progressive narrative. The chemical company Monsanto, for example, in an attraction taking visitors inside the atom, celebrated the way science is unlocking nature’s secrets, bringing better living through chemistry, and promising tremendous benelts from nuclear power, as did Our Friend the Atom (1957), a partially animated educational film.[21] This sort of unbridled technological optimism was displayed, as well, at attractions that, even before space might began, expressed awe at rocketry, envisioned space travel and settlements on the moon, and eventually, celebrated the Apollo moon explorations and provided an attraction that envisioned a Mission to Mars. At Tomorrowland, America’s pioneering spirit, manifest destiny, and even the Anthropocene expanded beyond the biosphere into space and distant worlds.[22] Although a significant proportion of Americans’ faith in the righteousness of their nation had eroded, the notion of the nation’s exceptional nature and its important role as a light to all nations was well represented at Tomorrowland, and, for many, it retained its evocative power. There the presentation was not only that America was a beacon of technological hope that presaged a utopian future, but the conviction was that the land was itself sacred. This was nowhere more apparent than at its America the Beautiful attraction, which opened in 1960 and ran for two decades. After entering a large round room, visitors were surrounded by 360 degrees of awe-inspiring images of America’s landscapes and landmarks, which were accompanied by patriotic hymns and a corresponding narrative that began with an inspiring chorus of America the Beautiful. In a way that would be unheard of decades later after the 2016 election of the anti-immigration President Donald Trump, the film lauded the multitudes of immigrants who, yearning for freedom, had set aside narrow self-interest, sometimes sacrificing greatly, to build and settle the continent, establish democracy and justice, and make America great.

Celebrating the national saints at Mt. Rushmore, America the Beautiful ended with a my-by of the Statue of Liberty and the conclusion of its namesake hymn, about God shedding his grace on America and bringing goodness and brotherhood ‘from sea to shining sea’. This attraction provided another archetypal example of America’s civil religion; and as with most forms of patriotism, it provided an exaggerated sense of the republic’s virtue. For many, such performances also reinforced felt connections to their fellow citizens and loyalty to the nation, as well as notions of American exceptionalism and utopian possibilities. In addition to such sentiments, the celebration of the beauty of the land, even the unique beauty of the American land, reinforced the sentimental place feelings that are essential to religious nationalism.

Disney’s Subversive Filmmaking

Despite the prevalence of themes that, more often than not, explicitly or implicitly consecrated settler colonialism, the taming of wild nature, and the putatively new, freedom-loving and technologically progressive American republic, there were also expressions of ambivalence under the Disney umbrella. Some of these would even morph into at least modestly subversive strains critical of the human domination of the world.[23]

Some of this I wrote about elsewhere, where I discussed how Disney filmmaking has not only celebrated settler expansionism but, in both animated and documentary forms, has evocatively promoted empathy toward non-human organisms and conservationist prescriptions aimed at maintaining the balance and harmony of nature. Although these films have often been highly anthropomorphic and based on outdated ecological understandings, over time, at least those released as documentaries, have increasingly provided information that reflects current scientific understandings. Regardless of whether these films and the stories they have told have cohered closely with science, they have all tended to promote a wonder toward nature that expresses what I have variously called ‘spiritualities of belonging and connection to nature’ (Taylor 2001b, 2001a) and ‘dark green religion’ (Taylor 2010). Generally speaking, these spiritualities, in turn, promote pro-environmental values (Taylor, Levasseur, and Wright 2020). Given space constraints and my focus on Disney’s theme parks, I will only mention a few representative examples.[24]

Disney’s earliest feature-length, animated films, established the genre. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) and Bambi (1942) both depicted forest creatures as cute and friendly. Audiences were especially moved when Bambi’s mother was killed by a hunter and the rest of the terrified forest creatures med an anthropogenic forest fire. The Jungle Book (1967) blurred the boundary between human and non-human communities as the feral child Mowgli was raised by wolves and found his home and kin in the forest. Its concluding song, ‘The Bare Necessities’, preached a common environmental theme that was emerging forcefully during the 1960s, that happiness cannot be found in material consumption (Whitley 2008: 115). Similarly, the line between human and non-human worlds were blurred in The Little Mermaid (1989), as when Ariel chose to become human and when Tarzan (1999), who was raised by gorillas, later saved them from capture. Perhaps the most influential of all has been The Lion King (1994, remade in 2019), which, including in its award-winning theme song celebrating the ‘Circle of Life’, depicted nature as sublime and in a delicate balance that needs to be respected. The film clearly suggested that when we recognize that all living things play important roles in the world’s life cycles we will come to respect all living things. Like Bambi and Snow White, Simba in the Lion King also experienced the ‘magic’ and love of nature, in his case when his father spoke to him through the wind, clouds, and stars, reminding him of his obligations to the ecological whole.

Remarkably, Pocahontas (1995) and Brother Bear (2003) changed the script with regard to Native Americans; they both sympathetically portrayed Native Americans and their animistic spiritualities and felt kinship with non-human organisms. Both also expressed common, environmental themes. Pocahontas was especially subversive in its message that Native American lifeways, and attitudes toward nature, were superior to that of, in her case, the newly arrived Europeans who did not understand that the world is filled with spiritual intelligences. This film even deviated from the history that is known about Pocahontas; in the film she stayed with her people rather than being transported to and dying in England. In this additional way, the film challenged the common American understanding of the superiority of European culture.[25] It was not only the treatment of Native Americans by Europeans that has been reappraised in Disney films; so was the notion that humans should hold marine organisms in captivity. Following cultural changes precipitated in part by the evocative non-Disney film, Free Willy (1993), which was about freeing an orca captured young in the wild, Finding Nemo (2003) and its sequel Finding Dory (2016) did for captive marine organisms what Bambi did for forest creatures: it made them creatures humans could relate to and care about. And here, the longstanding theme of freedom and liberty, and implicitly, of moral considerability (a term in environmental philosophy which refers to those whose interests ought to be taken into consideration) was now being applied to at least some marine organisms. Interestingly, after another non-Disney documentary was released, Blackfish (2013), which harshly criticized the marine park industry and its treatment of whales, Finding Dory’s script was changed (Barnes 2013).[26] The revised script had Dory and her salty friends battling to escape; indeed, freedom and a return to their oceanic home was their ultimate destiny. Moreover, at several points, the film asserted that the only proper rationale for marine parks was ‘rescue, rehabilitation and release’. An announcer at the marine park even proclaimed, ‘Every animal we rescue and care for eventually will return home, where they belong’. Of course, many organisms in marine parks are captured in the ocean and few of those who are bred in captivity ever return to the sea.

Despite such ambiguities, Disney’s animated and theatrical nature films, as well as Disney’s nature documentaries, have sought to evoke wonder and felt appreciation of nature. Nature documentaries were Walt Disney’s first and, early on, his most profitable productions. They began with the academy award-winning True Life Adventures (from 1948), which aired both on television and in theatres. And in 2008, DisneyNature was launched to create big-screen nature documentaries with the latest technologies. In the company’s announcement of this initiative, Disney’s then president and CEO, Robert Iger, stated that their goal was to foster ‘greater understanding and appreciation of the beauty and fragility of our natural world’.[27] Putting the avowed environmental crusade even more explicitly was a DisneyNature executive who declared, in a special feature released with Oceans (2010), that at Disney, they are teaching the ‘intrinsic value of nature’.[28] Such a value commitment, quite obviously, rejects the human domination of nature and the concomitant erosion of biodiversity. Over the decades, Disney filmmaking has increasingly, both implicitly and explicitly, challenged notions that any particular group of humans should subjugate others, as well as any idea that human beings should treat the rest of the world as its slave.

Walt Disney World and EPCOT

Five years after Walt Disney’s death in 1966, the second theme park that Walt Disney planned was opened in central Florida. Roy Disney, who saw the project through to its 1971 opening, named the entire area, which included several separate parks, Walt Disney World. Its Magic Kingdom largely replicated Disneyland, with its Main Street USA, Adventureland, Frontierland, Fantasyland, and Tomorrowland. Two entirely new parks appeared in Florida, EPCOT (meaning Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow), which opened in 1982, and Animal Kingdom, which opened in 1998. Discussion of both is essential for holistic analysis of the entanglements of religion, nature, and the Anthropocene in Disney’s worlds.

EPCOT continued the theme of technological utopianism that was initiated at Tomorrowland, including attractions that celebrated space exploration. EPCOT was innovative in new ways, however, urging environmental conservation and even a technology-led sustainability revolution. Indeed, it could be said that Disney was promoting the idea of a ‘good Anthropocene’ through ‘eco-modernism’, long before such terms and a corresponding school of thought emerged and gained significant attention, as well as scathing criticism.[29] Other themes have been present there, as well.

For example, while waiting in line for the animistically titled Listen to the Land boat ride, which was presented by Chiquita and later renamed Living with the Land, visitors encountered statements expressing love and trust in nature. Two of these were from well-known romantic writers, including the poet William Wordsworth, ‘Nature never did betray the heart that loved her’, and the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, ‘Nature never deceives us; it is always we who deceive ourselves’. Others quoted were religious figures, including Pope John Paul II, ‘We cannot say we love the land and then take steps to destroy it’; scientists, including Francis Bacon, who has been blamed for promoting an authoritarian antipathy toward nature as well as credited as the father of modern science, ‘Nature is not governed except by obeying her’. Even a US president not known for environmental concern, George (probably H.W.) Bush, contributed to the nature-respecting chorus, as did a number of unknown school children.

The ride took visitors through a number of earthly biomes before concluding at a Sustainable Agriculture: Production and Research Center, which demonstrated how foods can be grown hydroponically and in other innovative ways, while also explaining integrated pest management. It also included a Biotechnology Lab—In Cooperation with USDA Agricultural Research Service, suggesting that nothing is to be feared, and environmental solutions are being found, by scientists manipulating the DNA of organisms.

Nearby, a seventy-minute film, Circle of Life, an Environmental Fable, which was based on the Lion King, promoted conservationist themes; it appeared there from 1995 until early 2018. Across from this venue was an ‘Innoventions’ [sic] building. Its exhibitions continued to express the view that all the challenges we face, including environmental ones, could be solved by scientific and technological ingenuity, as exemplified in an exhibit presented by IBM titled ‘An exploration into making the world work better’. There, an airplane took visitors on a tour featuring ‘icons of progress’ and included paeans to scientists, military technologies (it specifically featured ‘The first National Air Defense Network’), and lauded ‘The preservation of Culture through Technology’ (featuring new archeological and other techniques). Its ‘Smarter Planet agenda’ explained how we can more intelligently manage ‘transportation, commerce, education, energy, food, water [and thus] capture the potential of a world that is becoming instrumented, interconnected, and infused with intelligence’. Nearby, another venue, Project Tomorrow: Inventing the Wonders of the Future, was presented by Siemens, along with a Vision House, which featured green home innovation and design.

Playing off of the blockbuster film Finding Nemo, The Seas with Nemo and Friends promoted the idea of exploring and appreciating the world’s oceans, as well as empathy toward marine organisms. The ride and its exhibits included aquariums, where visitors could wonder at the ocean’s diversity. Also at this educational and conservationist venue, exhibits forthrightly proclaimed that ‘Conservation Starts with You’, while urging participation in beach clean ups, helping sea turtles, and volunteering and donating to zoos, aquariums, and conservation organizations. This venue also included a ‘Manatee Rehabilitation Center’, where injured members of this endangered species were being rehabilitated from injuries they had received, mostly from Florida’s boaters. There, a panel, borrowing a phrase from Finding Nemo, declared, ‘Fish are friends, not food’. It added, ‘You guessed it—manatees are vegetarians!’. The venue also provided facts about threatened coral reefs, sharks, and other endangered marine species.

Another main attraction at EPCOT has been its World Showcase. Much like ‘It’s a Small World’ at Disneyland and at Disney World’s Magic Kingdom, it celebrates the world’s cultural diversity. There, visitors stroll through villages crafted to resemble eleven highly diverse countries. This area at EPCOT may reflect the increasing diversity and cosmopolitanism that is present in much of American culture, and enthusiastically embraced by Disney’s imagineers. Thus Disney’s World Showcase may moderate its longstanding themes that celebrate US exceptionalism and promote nationalism. Such additions also, likely, reflect a commercial purpose, showing respect to the millions of Disney customers who come from foreign lands.

The Animal Kingdom…from the Tree of Life to Africa

To follow up with my analysis of the Animal Kingdom, after moving to Florida, I returned in 2010, 2014, and 2018.

The layout of the park is reminiscent of Disneyland and its replica, Magic Kingdom. But rather than walking down Main Street USA, visitors enter the park and wander through an ‘oasis’, which according to Disney’s own description, offers ‘Eden-like mora and fauna rich with cooling waterfalls and meandering streams’.[31] Also available are opportunities to purchase Disney souvenirs. At the end of the oasis, instead of a Fantasyland Castle, there is the sacred center, the axis mundi, of the Animal Kingdom: a massive Tree of Life. The Tree is actually a fourteen story high sculpture modeled after the African Baobab Tree, which is sometimes referred to as the African Tree of Life.[32] Into its trunk and branches 325 animals were crafted and their limbs, wings, and other body parts were entwined, thus symbolizing the interconnection of life. Underneath the tree a 3D film, It’s a Bug’s Life, drew on a 1998 Disney film by the same name. This film, and outside at an exhibit entitled ‘It’s Tough be a Bug’, visitors are told ‘insects are your friends’ and their importance to ecosystems is explained. The pro-insect message appeared elsewhere at the park as well. Indeed, explicit conservationist messages were woven throughout the Animal Kingdom.

When it first opened, the Kingdom’s central focus was on African nature and its featured attraction was the Kilimanjaro Safari. Disney had imported thousands of African plants and animals to create a savannahresembling landscape through which visitors would ride on a simulated Land Rover through the Harambe Wildlife Reserve. Those on the safari were there, of course, to enjoy the wildlife, but they were also urged to help the reserve’s rangers protect its endangered animals by being on the lookout for poachers. Indeed, a sign leading up to the platform where visitors board the safari vehicle proclaimed, ‘Wild animal poaching is social evil’.

It was, perhaps, unsurprising that Disney would focus on the threat that poachers pose to Africa’s wildlife and the heroism of the rangers opposing them; it makes for a good if simplistic melodrama. Upon my first visit in 1998, after viewing and learning about some of the animals on Disney’s savannah, I discovered that the exit path led into an area with displays that looked like the kind of poster-board presentations commonly found at scientific conferences. These displays explained in more detail than most visitors could or would read, the diverse interplay of social and ecological factors that have led to Africa’s biodiversity crisis. In the following years, these interpretive panels were replaced with simpler explanations of conservation challenges and solutions and scattered more widely throughout the Kingdom.

Near the safari one can wander through an African village or attend The Festival of the Lion King, a version of which has also been longrunning in New York City and London. This festival engages the audience by asking those in attendance to identify with non-human animals by assuming their voices during the performance. It also celebrates the ‘Circle of Life’ in its finale, providing an emotional if not also a ritualized embrace of Mother Nature herself. This exemplifies why, when seeking to understand nature spiritualities, it is important to look for exhortations for people to connect emotionally to nature, or to experience awe and wonder at its beauties and mysteries; it is also important to note when technologies or other means are recommended, or provided, that are designed to provide just such experiences. Many examples are apparent at the Animal Kingdom.

At the end of a short train ride from the Africa section, for example, one first sees this sign: Ralki’s Planet Watch—Open Your Eyes to the World around You—while the map to this venue explained that this was a place to ‘discover how to save the world’.[33] The venue was named for the wise baboon in the Lion King, and the first thing one sees there is the aptly titled Affection Station, where children have been provided a place to connect emotionally to (non-predatory) animals by petting and hugging them.

In an adjacent building, a Conservation Station is pitched to curious children and teaches basic conservation science while encouraging pro-environmental behavior. Nearby, soundproof booths provide a special meditative place to listen to the sounds of different ecosystems. Adjacent to these booths children pose for photographs with an actress dressed as Pocahontas, right in front of Grandmother Willow. Between 1998 and 2008, the animistic dimension of the Pocahontas film, in which trees communicate with open-hearted people, was reiterated during a performance titled Pocahontas and Her Forest Friends. In it, Pocahontas explained that all creatures, even snakes, are needed for the forest to be healthy. She also expressed anguish during her conversations with Grandmother Willow over the logging of her beloved forest. Her overarching, plaintive question to her audience was, ‘Will you be a protector of the forest?’[34]

When Animal Kingdom opened, visitors could also connect to nature, and learn about conservation challenges and practices, via the Pangani Forest Exploration Trail. (The trail was likely named for a region in Tanzania, not for the god Pan.) A sign at the entrance to the trail explained that the trail leads into a wildlife sanctuary that has been protected through a collaboration between the citizens of Harambe and a number of International Conservation groups. It then quoted an aphorism that has become widely disseminated within the global environmental milieu, ‘We do not inherit the Earth from our parents— we only borrow it from our children’. Disney attributed the saying to an African proverb, but those acquainted with the global environmental milieu have probably seen it attributed to the Native American Chief Seattle, as I have in many ways and places, including on a napkin in a bagel shop chain in Amsterdam.[35] The statement, ironically, was most likely the invention of a Hollywood screen writer, who, with it, depicted a stereotypical view of Native American spirituality. However mysterious the saying’s origins, it is a good expression of the intergenerational ethics promoted by environmentalists.

Along the trail one could visit a Conservation School and an Endangered Species Rehabilitation Center, sign up to be a Wilderness Explorer through a kind of Junior Ranger program, and learn about issues such as the role of bushmeat hunting in Africa’s biodiversity crisis. The park’s wildlife areas were also accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums and the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums, which mandate specific standards and the participation in breeding programs to help endangered species. Much of the purpose of showcasing these animals on this trail and later, after an area focused on Asia opened in 1999, has been to help visitors connect emotionally to and experience the wonder of specific endangered animals, including a troop of lowland gorillas and critically endangered Sumatran tigers.

…from Asia to Avatarland

The tigers were found in an area named after a region in India, the Anadapur Royal Forest Tiger Reserve. There, visitors could wander through the Maharajah Jungle Trek and see many animals native to South Asia; the storyline was that of villagers and their beneficent rulers living in harmony with the region’s wildlife. Also in this area is a Flights of Wonder attraction, which teaches visitors about a variety of birds, including by displaying many of their behaviors.

The Asia area also offered scary adventures, including an Expedition Everest to the Nepal and the Tibetan plateau. As one approaches the train platform, which is actually a rollercoaster to a forbidden mountain near Mt. Everest guarded by the mythical Yeti, the thrill-seekers see trees adorned with Tibetan prayer mags. Adjacent plaques urge respect for these trees and explain that they are venerated by the local inhabitants. In another display of Disney’s environmental engagements, a glass case displayed objects commemorating a 2005 expedition that the Animal Kingdom funded and participated in with Conservation International. The plaque lauded traditional Tibetan and Sherpa conservation practices, and noted that the scientists worked with stakeholders from these communities to document the region’s biological diversity.

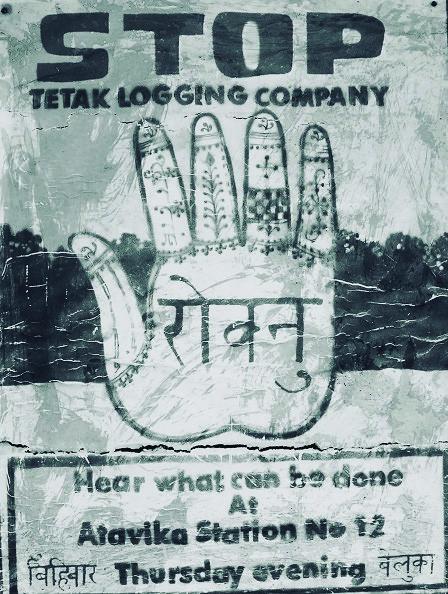

Known to few visitors is that, undergirding this collaboration, was the growing scientific understanding that the spiritual beliefs and practices of traditional cultures (including those that today are typically termed ‘indigenous’) are often entangled with profound ecological understandings regarding how to live in a habitat without eroding its biological diversity (see Berkes 1999, 2005; Gadgil, Berkes, and Folke 1993; Lansing 1991; Messer and Lambek 2001; Nelson and Shilling 2018; Rappaport 1968; Reichel-Dolmatoff 1996; Reo and Whyte 2012; Williams and Baines 1993). Such understandings may also be related to the acknowledgment, also at this venue, that conservation efforts often involve direct-action resistance to logging; one sign posted there announced a meeting to ‘Stop Tetak Logging Company’. Implicit in this display is that the expansion of industrial, market societies, with their voracious appetites for natural resources, is a threat to both biological and cultural diversity.

This sort of perspective may have been subtle and easy to miss on Disney’s Tibetan plateau, but it was one of the themes in Avatar (2009), a blockbuster science-fiction fantasy film conceived of and directed by James Cameron.[36] Avatar is set on Pandora, a moon circling a gaseous planet in the Alpha Centauri star system. The planet and the entire story is a metaphor for the human history of Earth, which has involved the imperial expansion of large and powerful societies at the expense of small-scale indigenous ones. In Avatar, human invaders who had already and imprudently stripped bare their home planet, came with military might and mining technology to acquire a rare mineral they needed to fuel their imperial ambitions. Scientists interested in the moon’s biota were also deployed to help the invaders secure the cooperation of the Na’vi, the moon’s aboriginal peoples; if such cooperation could not be not secured, the scientists and the mercenaries with them were supposed to discover Na’vi weaknesses so the moon’s natives could be effectively subjugated.

The film produced a fierce debate, some of which I orchestrated in Avatar and Nature Spirituality (2013). The film’s central narrative revealed that the natives had a deep, spiritual connection to and understanding of the moon’s mora, fauna, and environmental systems. Moreover, they had an ecologically and socially rich way of life, one that clearly resembled what many today think about Earth’s indigenous societies. Indeed, the film included a shaman and rituals that underscore the notion that all life is interconnected and that indigenous people have special ecological wisdom. Some of the human invaders came to understand the beauty of these people, their lifeways, and the moon’s living systems, and joined the Na’vi resistance to the invading forces. In short, the film taught that biological and cultural diversity are mutually dependent; it also sought to metaphorically evoke an affective appreciation for the beauties and diversity of Earth’s living systems. As Cameron put this intention, ‘Avatar asks us to see that everything is connected, all human beings to each other, and us to the Earth’. And he explained that he sought to use the ‘magic’ and ‘wonder of cinema’ to help people ‘appreciate this miracle of the world that we have right here’ (Access 2010). Thus, Avatar the film, and Pandora—the World of Avatar (henceforth Avatarland), which opened in 2017 at the Animal Kingdom, were both designed to evoke and deepen reverence for earthly life.

Avatarland’s setting takes place well after and does not recapitulate the conmict depicted in the film, however. Its focus is on the beauty and wonder of Pandora. For Avatar Flight of Passage, its most popular attraction, park visitors assume identities as Pandoran ecotourists, my on an Ikran (a mying dragon-like banshee), and participate in a tribal rite of passage, as well as learn about how the Ikran are a keystone species (Porges 2018). The second main attraction is a peaceful Na’vi River Journey, which features beautiful bioluminescent plants and intriguing wildlife. It ends with Na’vi Shaman of Songs, who sings a poetic, melancholy song in the Na’vi language about the beauty and sadness of the forest. The ride is alight with animistic wood sprites and it includes a prayer-like reference to the Great Mother, Eywa, the pantheistic goddess of Pandora, in whom all things are one.[37] The indigenous theme is reinforced outside, where one can participate in a drum circle, and throughout the rest of the area one sees the sights and sounds of Pandora, its moating mountains and forest, which change depending on whether it is daytime, twilight, or night. Unlike at other areas of the park, the conservationist messages were not explicit (except at Avatarland’s eateries, which stressed how the foods were sourced sustainably). Nevertheless, the entire land seemed designed to kindle wonder and delight in nature, and respect for the spiritualities and lifeways of indigenous peoples.

…from Avatarland to the Rivers of Life

Since its opening in 2017, the finale for many Animal Kingdom visitors has been a performance of its Rivers of Light: A Celebration of Nature’s Wonders. The spectacle fused romantic music, brightly lit moats moving about a large lake, and nature-related themes drawing indigenous and Asian religions. These included lotus mowers (presumably symbolizing the purity of nature), indigenous shaman storytellers, and animal spirit guides symbolizing Earth, air, fire, and water. In its greatest technological feat, curtains of water sprayed by water cannons are illuminated by a projector that shows a host of terrestrial animals and birds running or flying across the watery horizon. Just as striking were the narrative and songs that accompanied the various phases of the show. The performance began by welcoming the audience to ‘A celebration of nature’s wonder told through music, water, and light’. Shortly afterward, as ships moated in, a female voice intoned:

Of all the gleaming planets in our vast universe, it is only here, on Earth, that water and light harmoniously unite to create the wonder of life… Here, where the forces of nature meet in harmony, the spirits of the animals are free to dance together in the night sky, creating rivers of light. We are united in this special place to celebrate the magnificence and wonder of all living creatures, for in life, we are all one.

Later, in ‘We are One’, the festival’s main song, there is a religion-resembling call to a ritualized and sensory experience of nature, for ‘It’s our rite | it’s our call | every creature great and small…’ The song exhorts the audience to engage in specific practices evocative of a veneration or worship of nature: ‘Raise your hands to the sky | feel the rain | face the wind |Touch the earth | And take it in | Touch the sea | Feel the light | Live the fullest of this life | Touch the earth | Feel the sun | We are one in Relation | Touch the earth | Feel the sun | We are one’. The lyrics also averred that ‘We are one with the oceans’, celebrated pure water and wilderness, and ended with a female voice offering what seemed like a benediction:

Within each of us is a light, a light that shines in all living things. Here with fire and water, between the earth and sky, our light rises on the wind to join the stars. As we journey on this great Earth, may we remember the life we share, may we celebrate our bond with the natural world, and the wonders that mow on the rivers of light.

The performance also ended with the Tree of Life lighting up on the distant horizon.

While watching the performance I was stunned by how overtly the performance expressed and promoted the spiritualities of belonging and connection to nature, and even the kinship of all life, that are central in contemporary nature spiritualty. This was striking in part because, presumably, Disney would want to avoid offending prospective customers; Disney had previously been criticized for productions that conservative religionists consider idolatrous, promoting the veneration or worship of nature rather than God, even threatening the hegemony of their God in the public sphere.[38] Their fear is well founded because ‘dark green’ nature spiritualities have cultural traction and are being influentially expressed and promoted by a host of cultural creatives within and beyond popular culture.

Conclusion

Much can be criticized regarding Disney’s environmental practices, including the destruction of native Florida habitat for the creation of Walt Disney World, the environmental impacts of its daily operations, and the contributions to climate disruption from the travel of millions to its attractions. Moreover, Disney messaging, from a perspective that values both biological and cultural diversity, has been inconsistent and often ironic. Nevertheless, I remember being impressed upon my initial visit to the Animal Kingdom by those poster-board displays explaining the drivers of extinction and how community-based conservation efforts were addressing them; and I have noted how efforts to reach visitors through encounters with rare animals, emotional artistic attractions, and simple and widely scattered conservation messages have continued there in new forms. I wondered, where else would millions of ordinary people, including those without significant environmental education or time in environmentalist enclaves, ever encounter such information? Drawn in by such curiosity, in 2004, I interviewed Jackie Ogden, then the Director of Animal programs at the Animal Kingdom. She explained that she earned her PhD in wildlife ecology because she wanted to help protect biological diversity and ‘save the world’; she also expressed ‘respect and awe’ for nature in a way that resembles nature spiritualities found widely around the world. To animal rights critics of zoos and the Animal Kingdom, she replied, that given the right opportunities, people can develop a love for animals at such places. She continued, ‘zoos and the Animal Kingdom have an important and positive role to play in conservation because conservationists must reach out beyond the purist 5–10% who already care’. Sounding much like the executive who said that at Disney they were teaching the ‘intrinsic value of nature’, Ogden conlded that, at the Animal Kingdom, ‘Our mission is to help inspire all of our guests to care more about wildlife’.[39] Of course, the quest for prolt drives a great deal of what transpires under Disney’s corporate umbrella, but it is also clear that Disney’s creatives are complicated creatures, motivated by more than pecuniary interests.

Indeed, most people have many motivations and are replete with ambivalences, contradictions, and uncertainties—much like the societies they inhabit and popular culture generally. As people wrestle with the resulting contestations, society and popular culture continues to unfold and change. As environmental alarm intensifies and as adherence to the world’s longstanding, predominant religions continues to erode in much of the world, popular culture will continue to be an important site for the quest for spiritual fullllment and meaning. And these messy cultural processes will have something to say about whether Homo sapiens will continue to be an imperial animal, or as Aldo Leopold once famously put it, change ‘from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it’ (1966 [1949]: 240). Those who are trying to awaken such values and precipitate corresponding practices, including at least some of Disney’s cultural creatives, are among a growing chorus of rebels against the Anthropocene.

References

Access. 2010. ‘James Cameron’s “Avatar” Wins Big at Golden Globes’, Access, 17 January. Online: www.accesshollywood.com.

Asafu-Adjaye, John, et al. 2015. An Ecomodernist Manifesto. Online: http://www. ecomodernism.org/manifesto.

Barnes, Brooks. 2013. ‘“Finding Nemo” Sequel Is Altered in Response to Orcas Documentary’, New York Times, 9 August. Online: artsbeat.blogs. nytimes.com/2013/08/09/lnding-nemo-sequel-is-altered-in-response-to-orcasdocumentary/?_r=0.

Barnosky, Anthony D., et al. 2014. ‘Introducing the Scientific Consensus on Maintaining Humanity’s Life Support Systems in the 21st Century: Information for Policy Makers’, The Anthropocene Review 1.1: 78–109. DOI: doi.org.

Barrier, J. Michael. 2007. The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney (Berkeley: University of California Press).

Bellah, Robert. 1967. ‘Civil Religion in America’, Daedalus 96: 1–21.

———. 1975. The Broken Covenant: American Civil Religion in Time of Trial (New York: Seabury).

Berkes, Fikret. 1999. Sacred Ecology: Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Resource Management (Philadelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis).

———. 2005. ‘Traditional Ecological Knowledge’, in Taylor (ed.) 2005: 1646–49.

Boivin, Nicole L., et al. 2016. ‘Ecological Consequences of Human Niche Construction: Examining Long-Term Anthropogenic Shaping of Global Species Distributions’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113.23: 6388–96. DOI: doi.org.

Brereton, Pat. 2005. Hollywood Utopia: Ecology in Contemporary American Cinema (Bristol, UK: Intellect Books).

Brode, Douglas. 2004. From Walt to Woodstock: How Disney Created the Counterculture (Austin: University of Texas Press).

Champ, Joseph G., and Rebecca Self Hill. 2005. ‘Theme Parks’, in Taylor (ed.) 2005: 1631–32.

Cotter, Bill. 1997. The Wonderful World of Disney Television: A Complete History (New York: Hyperion).

Crist, Eileen. 2013. ‘On the Poverty of Our Nomenclature’, Environmental Humanities 3: 129–47. DOI: doi.org.

Crosby, Alfred W. 1986. Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900– 1900 (Studies in Environment and History; Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press).

Crutzen, Paul J. 2002a. ‘The “Anthropocene”‘, Journal de Physique IV 12. DOI: doi.org.

———. 2002b. ‘Geology of Mankind: The Anthropocene’, Nature 415: 23. DOI: doi.org.

Crutzen, Paul J., and Eugene F. Stoermer. 2000. ‘Opinion: Have We Entered the Anthropocene?’, Global Change. Online: www.igbp.net.

Cuomo, Christine J. 2017. ‘Against the Idea of the Anthropocene Epoch: Ethical, Political and Scientific Concerns’, Biogeosystem Technique 4.1: 4–8. DOI: doi.org.

Cypher, Jennifer, and Eric Higgs. 2001. ‘Colonizing the Imagination: Disney’s Wilderness Lodge’, in Bernd Herzogenrath (ed.), From Virgin Land to Disney World: Nature and Its Discontents in the USA of Yesterday and Today (Amsterdam: Rodopi): 403–23. DOI: doi.org.

Deudney, Daniel. 1995. ‘In Search of Gaian Politics: Earth Religion’s Challenge to Modern Western Civilization’, in Bron Taylor (ed.), Ecological Resistance Movements: The Global Emergence of Radical and Popular Environmentalism (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press): 282–99.

———. 1996. ‘Ground Identity: Nature, Place, and Space in Nationalism’, in Yosef Lapid and Friedrich Kratochwil (eds.), The Return of Culture and Identity in IR Theory (Boulder/London: Lynne Rienner): 129–45.

Diamond, Jared M. 1972. ‘Biogeographic Kinetics: Estimation of Relaxation Times for Avifaunas of Southwest Pacific Islands’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 69: 3199–203. DOI: doi.org.

———. 1975. ‘Island Dilemma: Lessons of Modern Biogeographic Studies for the Design of Nature Preserves’, Biological Conservation 7: 129–46. DOI: doi.org.

———. 1997. Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies (New York: Norton).

———. 2005. Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed (New York: Viking).

Dinerstein, Eric, et al. 2017. ‘An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm’, BioScience 67.6: 534–45.

Doi: doi.org.

Durkheim, Emile. 1965 [1912]. Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (New York: The Free Press).

Edgeworth, Matt, et al. 2019. ‘The Chronostratigraphic Method is Unsuitable for Determining the Start of the Anthropocene’, Progress in Physical Geography 43.3: 334–44. DOI: doi.org.

Eliade, Mircea. 1991. Images and Symbols: Studies in Religious Symbolism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press).

Ellis, Erle. 2012. ‘The Planet of No Return: Human Resilience on an Artificial Earth’, Breakthrough Journal 2.Winter. Online: thebreakthrough.org.

Erb, Karl-Heinz, et al. 2018. ‘Unexpectedly Large Impact of Forest Management and Grazing on Global Vegetation Biomass’, Nature 553: 73–76. DOI: doi.org.

Frommer, Paul. 2017. ‘Way Tiretuä—the Shaman’s Song’, Na’viteri.Org Blog, 1 July. Online: naviteri.org.

Fuller, Dorian, et al. 2011. ‘The Contribution of Rice Agriculture and Livestock to Prehistoric Methane Levels: An Archeological Assessment’, The Holocene 21.5: 743–59. DOI: doi.org.

Furtwangler, Albert. 1997. Answering Chief Seattle (Seattle: University of Washington Press).

Gabler, Neal. 2006. Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination (New York: Knopf).

Gadgil, M., F. Berkes, and C. Folke. 1993. ‘Indigenous Knowledge for Biodiversity Conservation’, Ambio 22: 151–56.

Hamilton, Clive. 2015. ‘The Theodicy of the “Good Anthropocene”’, Environmental Humanities 7: 233–38. DOI: doi.org.

Harari, Yuval N. 2015. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind (New York: Harper).