Debra Gwartney

Correspondent, The Oregonian

Protesters call treetops home

Forest Service intervention doesn’t stop a group near Eugene

Dec 6, 1998

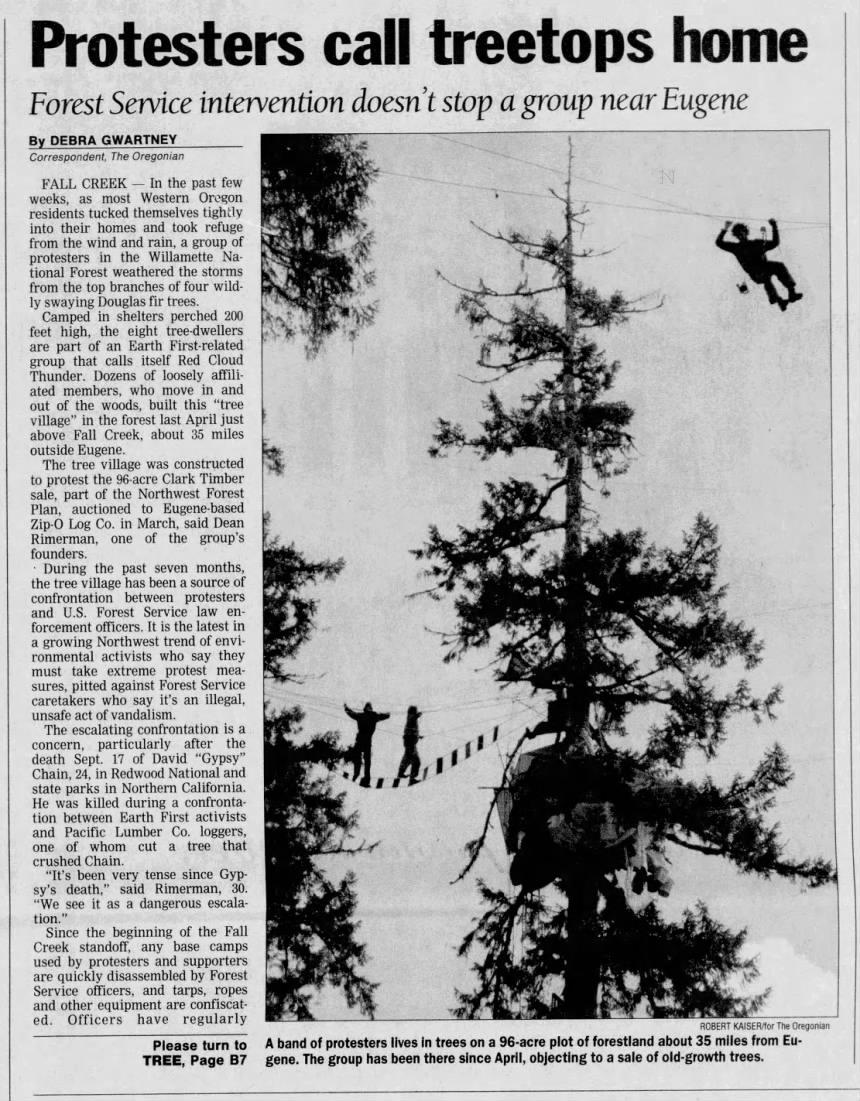

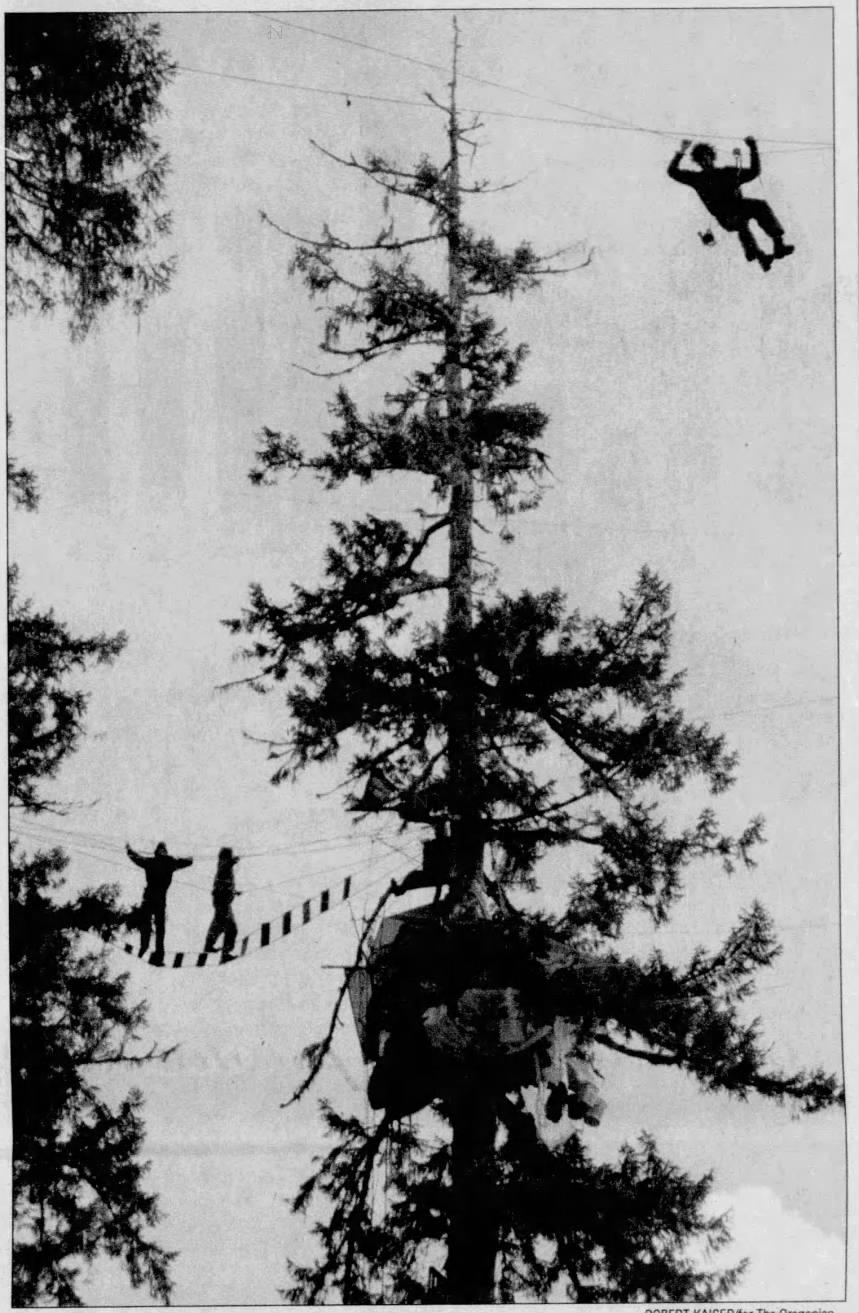

A band of protesters Ilves In trees on a 96-acre plot of forestland about 35 miles from Eugene. The group has been there since April, objecting to a sale of old-growth trees.

FALL CREEK — In the past few weeks, as most Western Oregon residents tucked themselves tightly into their homes and took refuge from the wind and rain, a group of protesters in the Willamette National Forest weathered the storms from the top branches of four wildly swaying Douglas fir trees.

Camped in shelters perched 200 feet high, the eight tree-dwellers are part of an Earth First-related group that calls itself Red Cloud Thunder. Dozens of loosely affiliated members, who move in and out of the woods, built this “tree village” in the forest last April just above Fall Creek, about 35 miles outside Eugene.

The tree village was constructed to protest the 96-acre Clark Timber sale, part of the Northwest Forest Plan, auctioned to Eugene-based Zip-0 Log Co. in March, said Dean Rimerman, one of the group’s founders.

During the past seven months, the tree village has been a source of confrontation between protesters and U.S. Forest Service law enforcement officers. It is the latest in a growing Northwest trend of environmental activists who say they must take extreme protest measures, pitted against Forest Service caretakers who say it’s an illegal, unsafe act of vandalism.

The escalating confrontation is a concern, particularly after the death Sept. 17 of David “Gypsy” Chain, 24, in Redwood National and state parks in Northern California. He was killed during a confrontation between Earth First activists and Pacific Lumber Co. loggers, one of whom cut a tree that crushed Chain.

“It’s been very tense since Gypsy’s death,” said Rimerman, 30. “We see it as a dangerous escalation.”

Since the beginning of the Fall Creek standoff, any base camps used by protesters and supporters are quickly disassembled by Forest Service officers, and tarps, ropes and other equipment are confiscated. Officers have regularly informed protesters that they are breaking federal law by inhabiting the trees and by building in the national forest, spokeswoman Sue Olson said.

“Our approach on how to deal with the situation hasn’t changed over time,” said Olson, who said recent severe weather has increased concern about the tree protest. “Safety has always been our first consideration. That goes for protesters, law enforcement officers and contractors who are working on behalf of timber sale operations.”

No matter what, Olson said, Forest Service climbers will not go up in the trees and attempt to bring down the protesters.

The tree villagers confirm that their confrontations with officers happen on the ground.

In the past several weeks officers have regularly piled up base camp equipment and other supplies and have burned them at the site, the protesters said.

However, Olson said that though materials and supplies are often confiscated as evidence, and base camps dismantled, only one item — an illegal structure built to block the road — has been burned.

The impetus of the protest revolves not just around the Clark Timber sale, but also protesters’ beliefs that their opinions about the logging of old-growth trees have never mattered throughout the process, said Rimerman. who lives in Eugene.

“The Forest Service is unwilling to take into regard popular public opinion,” Rimerman said. “People don’t want the ancient forest cut.”

After exhausting legal options, he said, the only action left for his group was to take a “no compromise” position in the trees.

In particular, he said, Red Cloud Thunder wants to draw attention to what the group claims is a lack of adherence to the Northwest Forest Plan. That includes a “completely lacking survey for endangered animals,” Rimerman said.

Protesters have reported that they often see endangered red tree voles, flying squirrels and spotted owls in the woods, none of which were documented in the Forest Service 1996 biological survey of the parcel.

Village has family atmosphere

The forest dwellers, who range in age from 15 to 40, have settled into the woods.

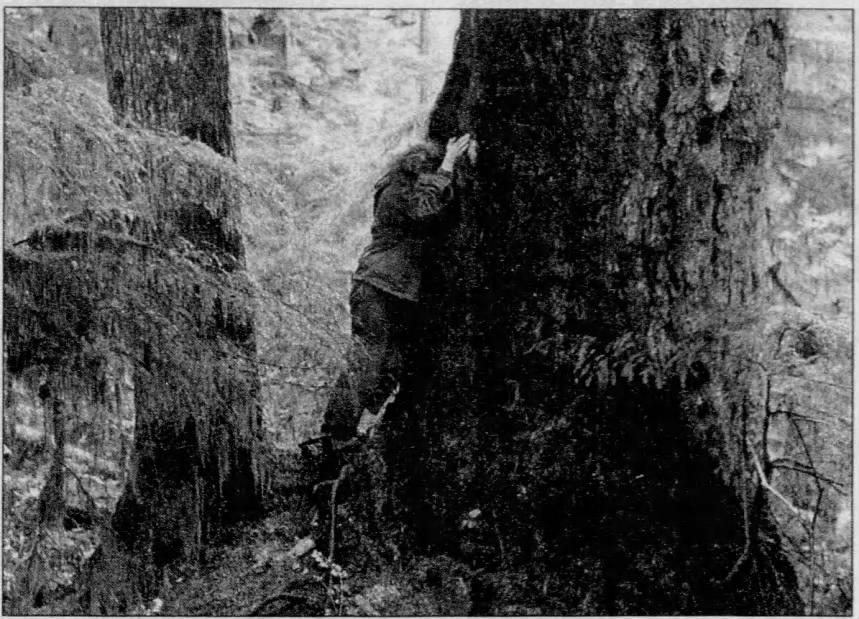

They have named each tree in the grove: Happy, Grover, Comfrey, Friendly, Yggdrasil and Foghorn are among them. The Red Cloud Thunder members have a deep-throated call that sounds out over the forest when they want to communicate. Their skin coated with dirt and their clothes tattered, they say this is the kind of family to which they want to belong.

“It’s become a kind of society,” Rimerman said. “We feel at home here.”

But there is a palpable lack of peace, as the protesters tensely wait and watch for the next confrontation with the Forest Service.

Rimerman said the constant need to find more supplies has not deterred the tree dwellers and their supporters. As winter settles in. bringing bitter winds and plenty of rain, the protesters say they have no intention of abandoning their plywood-and-tarp dwellings.

“We’re stronger than ever,” said Rimerman, who came to Oregon from California’s Bay Area. “We’re more organized and better prepared and have a lot of support from the community.”

One 35-year-old protester calls himself “Pacific,” citing the need to use a “woods name” because of potential legal consequences from the protest action. He wears camouflage clothing and has painted his face green to better hide in the woods. Though he spends most of his time in the forest, Pacific said when he is in town, he hears strong support for the protest.

“Eugene likes its recreation spots, and it doesn’t want its murky water to get any worse,” he said, referring to the concern that logging will damage the city’s ground water supply.

Rimerman said the group has had no trouble getting supplies and gear from Eugene residents.

“We can stand in front of a local natural food store for two hours and have $50 in cash and big box of healthy food,” he said.

Since April, hundreds of tree-sitters — some as young as 11 — have inhabited the village at about eight at a time, Rimerman said. Climbing ropes stretched between the four structures serve as a midair walkway, allowing the treesitters to travel from tree to tree with the use of harnesses and clamps. A propane stove is used to cook. A bucket hoists water and lowers wastes.

“It’s extremely livable,” said “Monkey,” a 21-year-old man from Washington state who has spent at least two months cumulative in the treehouse and declined to give his name. “It’s an amazing way to live. It’s easy to get around on the walkway, and it’s easy to cook in our kitchen.”

Formal protest disputed

To Olson of the Forest Service, the housekeeping in the woods is a fallacy, built on layers of illegal activity.

She said she is frustrated because the group did not organize to speak out in opposition to the Clark Timber sale during the public hearing process last year, instead of taking action in the trees.

“I implore people to get involved earlier, to come in like any citizen through the front door of our offices,” she said. “It’s important to understand what’s going on in your national forest during the process, rather than at the point of standing on the line and protesting.”

But Scott Cramblit, a former Willamette National Forest logger who grew up in Springfield and is a frequent visitor to the tree-sit, said he witnessed Rimerman’s unsuccessful attempt to take a stand during official proceedings.

“I know this group wouldn’t have become radical and climbed trees if the government channels had worked,” he said.

Doug Heiken, who runs the Eugene office of the Oregon Natural Resources Council, said his organization also tried to stop the Clark Timber sale through legal and procedural means but failed. The council has recently filed a lawsuit, alleging the failure of the Northwest Forest Plan in general, he said.

“The Clark sale is a good example of the many problems in the plan,” he said. Those include lack of legitimate endangered species surveys and lack of protecting steep slopes and wetlands, he said.

Heiken added that though he worries about the safety of the people in the trees, he supports the principles for which they are fighting.

“This parcel is close to Fall Creek; it’s close to Eugene; so many people come out and enjoy it,” he said. “And it’s a cathedral to these young people.”

A protester, who will only identify herself as “Chaos,” pays homage to the tree that holds one of the dwellings where eight members of her group, Red Cloud Thunder, have been living since April. The group Is preparing to go through a potentially rough winter to protest cutting old-growth trees.