Eisel Mazard

Escape from Gor

March 14, 2025

John Norman of Gor interview (1980)

No More Gor: A Conversation with John Norman (1996)

Although we have this saying in English; ‘don’t judge a book by its cover’, the truth is that the cover is an important part of the book.

A large percentage of the readers and devotee of John Norman’s book series, Gore, the Counter-Earth Chronicles, the Gorian Saga, whatever you want to call it... a large percentage of the readers would admit that they started reading in the first place because as teenage boys, the highly sexually suggestive cover art caught their eye and stoked their curiosity.

Alec Purves: First of all, where does the term kajira come from, Brandy?

Brandy: So kajira is a Gorean term that comes from the books. The commonality is la kajira, which is not French, and it means I am a slave girl.

Alec: But you’re almost 30 now. But it’s the fact that--.

Brandy: And you’ve known me since I was 18? 18 years old. …

I had a male who was telling me that I should be removed from school because it’s not my job to go to get an education. I need to be taken out of work because my job is to serve him. That I was going to live in a basement, and that was just my life.

The first editions of the books, when they were first published in the United States of America, had covers that were in absolutely no way sexually suggestive or provocative.

The Publishing companies, plural, who tried to make money out of these books, only realized in retrospect, many years later, just how pornographic these books were.

They went back and issued 2nd and 3rd editions, later editions of these books had increasingly sexually explicit covers as they figured out that’s what the audience was interested in, that was what the market was, and even that was the core content of these books that the author was trying to get across.

David Stewart: From this image, you should get an idea of what this is about.

Essentially, there’s this earth on the other side of the sun, and you have characters from our earth get kind of whisked off there and on this earth, it’s essentially like a medieval fantasy.

Women are, most women are basically slaves, and there’s a bunch of sex slaves, as you can tell from this particular cover image right here and this is something that goes through all of the novels, as women are literally physically dominated, like beaten, sexually dominated.

It’s a very strong, what most people consider anti-female empowerment narrative that runs throughout these particular books.

Brandy: So I first found out about gore when I was 18 years old.

That was 11 years ago now and I was like, what’s gore? And then I went on Google and then that kind of, I mean, wrapped this whole slavery, domination, Conan the Barbarian meets Frank Frazetta meets dirty perverted minds come to life in the book series and I just hook, line, sink or sunk into it.

David: A lot of people consider them misogynist, sexist, and perhaps they are.

The thing is, they’re also very successful, not just with men, but with women.

There’s a whole subculture that developed called the Gorean subculture, the Gore subculture, where women choose to live this lifestyle where they are essentially sexual slaves to a man and in the books, they’re often presented, you know, women are often presented as being sexually liberated through slavery, which is a weird thing and the women who aren’t slaves, like, are sexually repressed and There’s, I don’t know, there’s a lot of weird things like that.

So when we look at the content of these books, and we look at the intent of the author, there is a peculiar tension with what is written out so plainly, shall we say, in the cover art of these books and that is these books are at least ****** if not outright pornographic.

But here’s where the strange tension lies.

No one could have less of a detached, good-humored attitude towards this than the author of the books himself.

I think there would be no political controversy surrounding the Gore books whatsoever if he had the same sort of relaxed Hollywood entertainer’s attitude as someone like Kevin Smith. Kevin Smith is a film writer, movie director, what have you.

If he just had the attitude of, well, you know, these books are a little bit eccentric, but so am I and so are my readers. Well, you know, it’s all in good fun. Who hasn’t had a wacky, off-the-wall fantasy like this once a while? No, The enduring significance of these books and their enduring infamy and their source of political controversy is created by the incongruous fact that the author was a professor of philosophy, and he took these books seriously to a mind-blowing extent, as not merely his satire in our society as it is now, but the pronouncement of his political and social philosophy for what our society ought to be.

Alec: How did we meet, Brandy?

Brandy: So, funny story, you actually saved me because I was about 18 at the time, maybe a couple months to being 19 and as a Kajira, who was very young and naive.

So first of all, where does the term kajira come from, right? So kajira is a Korean term that comes from the books.

The commonality is la kajira, which is not French and it means I am a slave girl.

Kajira, you know, Dan is 30 now, but it’s the fact that. and you’ve known me since I was 18? 18 years old.

I had a male who was telling me that I should be removed from school because it’s not my job to go and get an education.

I need to be taken out of work because my job is to serve him.

that I was going to live in a basement and that was just my life and actually stalked me and found me at my school.

Rocker actually helped me get the authorities involved, get this person off of any kind of venue where he could contact me and kind of guided me towards like what ethical gore is versus what like a video game is.

David: So maybe it’s sexist, maybe it’s misogynist. Does that mean that you blacklist or censor it, particularly when you have a group of people, including women, who are really into wanting to live this lifestyle and it became a whole subculture, like an S&M subculture and you also have similar content like Fifty Shades of Grey.

Now, what happened with this novel is that the original publisher, Ballantine Books, didn’t want to publish the books anymore and you can maybe guess why, but this was a long time ago.

This is like in the 70s. So Dahl picked it up. Dahl’s a very famous publisher. Fantasy published a whole bunch of Michael Moorcock’s novels and a bunch of other people.

Very big fantasy, you know, fantasy publisher and somewhere in the book series, they decided they weren’t going to publish them anymore and the official reason they gave was low sales.

Not only that, he couldn’t find another publisher.

He said he got blacklisted by the entire industry as a result of the portrayal of women in his books and I also think he wrote like a practical, like fantasy dominating, sex dominating guide for couples as well, just as an aside, that I think might have sold pretty well.

John Owen: I posted a review of Hunters of Gore on Amazon.com and reposted it to my personal Facebook page.

It got such a strong, positive response that I figured I’d go ahead and share it with everybody.

Having heard various people, especially those in the role-playing **** community, extolling the magnificence of this series, I looked into it and found myself disgusted time and again at the idea of a philosophy that values men who control women with rape and physical beatings.

The most common defense I heard of the books was that they were intended to satirize feminism.

While there were certain thematic elements of this in the plotline of Outlaw of Gore, the remainder of the books seemed to ever increasing degrees to justify why a bully is the best thing that a man can ever be, and that men have a right and a responsibility to beat up women and terrorize them and what are three things that you would give as far as advice? to any new person coming in that’s considering as far as being a part of gore, as far as being a kajira, what are three things that you would give advice?

Brandy: First thing I would say is read the books. Just read them. Know what it is that you’re dealing with. Know the nuances of the difference of a stray slave versus a free woman that’s actually a kajira in clothing.

There’s a lot of subtle differences and nuances, and the most important thing is don’t submit to people that you’ve never met.

You don’t know who these people are, and there are a lot of dangerous people in this world, and you are more than likely a very attractive, very sweet girl who they want to keep forever.

perhaps the books touch on neglected or suppressed human constants, male and female.

Perhaps they have something to say, which has not been said for a long time.

They are probably unique, or almost so in modern literature, in raising serious questions about the intellectual superstructure of Western civilization.

I’m sorry. I’m sorry. The cover of the books doesn’t just matter to the members of the audience, they’re reading public. How is it possible for this guy, who is a professor of philosophy in New York State, how is it possible for him to hold up the book with these sexually graphic covers on it, how is it possible for him to be making millions of dollars out of peddling **** **** based on his own twisted sexual fantasies and to say, dead serious with a straight face in this way, these books are unique in modern literature in raising serious questions about the intellectual superstructure of Western civilization.

Absolutely nothing about the cover of these books suggests that they’re raising serious intellectual questions and let me tell you something, as this video goes on, I think you and my audience will come to agree with me that nothing about the content of these books raises such serious questions.

They have intellectual content.

There are ideas in them.

Perhaps that is what’s so outrageous Some critics.

He here compares himself to no less important thinker than James Watt, the inventor of the steam engine.

Many scientific breakthroughs related to the transformation of the modern West.

He compares himself in writing these sex fantasies to James Watt in challenging and transforming our civilization.

Hero of Alexandria in the 2nd century BC invented the steam engine.

James Watt the 18th century designs an improved steam engine and alters the course of human civilization.

I think a similar phenomenon has occurred with the Corrigan books.

How is it possible to be this delusional? And let’s just pause to reflect on this for a moment.

Again, keeping the lurid cover art in mind, what is the discovery that he thinks is equivalent to discovering the steam engine, industrialization, electricity, these kinds of things? What is the breakthrough that he’s saying people knew in ancient times, in the 2nd century BC, and then they’re rediscovering now in his sexy fantasy books, It’s slavery.

His idea is that in ancient Greece, they had ***** sex slavery, and now here he is again, rediscovering and profoundly transforming ***** sex slavery.

You know, the same sense that James Watt didn’t just rediscover the steam engine, he profoundly changed his civilization.

The claim is that John Norman, in writing the Gore books, is now going to transform the future of our civilization by rediscovering something from the past that was forgotten and what it is he’s rediscovering is men taking women captive, enslaving them, and in plain English, ****** them and that his claim is, this isn’t just the only thing that can make men happy.

This is the only thing that can make women happy.

It’s the only way to set Western civilization back on the road.

right path.

So again, a little bit of a contrast from the joking, self-effacing attitude of someone like Kevin Smith.

Kevin Smith very often is challenged about the fact that one film or another of his is absolutely terrible.

Perhaps the majority of his films are absolutely terrible and he’s able to sit there in a relaxed way and say, well, he’s just a storyteller.

He’s just having fun and some people like it.

If that were John Norman’s attitude towards creative output, I think I can say we wouldn’t be having this conversation right now.

There wouldn’t be any political controversy surrounding these books.

But I think because this was his attitude, because he took this strident philosophical and political position, I think this controversy is never going to die.

I think 100 years from now, the Gore books and their fans are going to be with us, and there are going to be new movies being made out of them.

I think the inspiration, like Conan the Barbarian, like Star Wars, I think there are some elements of this that will never, ever die.

Serp Kerp: It must have been, when they made these books later, he must have just escalated and that’s what I heard people say when I go on the Amazon reviews, is the first books, the first couple of books are good, and then as it goes on, they just turn into straight **** and just kind of misogynistic pseudo-philosophy.

John: This was the first score novel I read, and I subsequently read Tarnsman, Outlaw, Priests, Kings, and Captive, in case you...

want to accuse me of being ill-informed and I was introduced to Tarl Cabot, who revels not in consensual **** but in the merciless, gloating, terrorizing, more akin to a high school bully who, unable to accept the more tender and vulnerable feelings he has for a girl, beats her and humiliates her to suppress his own inadequacy in the face of those feelings.

Serp: But it’s like women desiring men based on their status.

not how good they treat them.

So men that have higher status but abuse women are considered highly attracted by women.

That’s like as edgy as this book gets.

Seagulls Gather: The section I think that will enrage more people than any other is where they work out the details of her slavery and Talina is forced to wear a collar announcing that she is his property.

Her life as a slave, though, actually affords her slightly more freedom than her life as a princess did, confined as she was by being veiled and limited to the Gorian Seraglio.

This real-world commentary features a handful of times in the text, dealing with not just Greek mythology, but also Darwinian concepts and again, in a section that might well offend quite a few, comparing the activity of the slave market with the more modern for 1969 dating practices, though that comparison actually seems more relevant in the Twitter age, it will certainly raise an eyebrow or a hackle or two.

John: Norman’s assertion is that men must be brutally harsh with women because if they ever show the slightest sympathy, then women will seize on that and enslave the men by weakening and feminizing them.

For the women in the novels, this is undoubtedly Every single female character in the aforementioned books, with one very minor exception, was a shrill, maniacal, malicious, stuck-up pain in the *** that was ultimately brought under control by a physically strong, arrogant man and what are the expectations as far as surrendering as a Kajira?

Brandy: The idea is that you give up yourself completely to your master.

The idea being that you are his article of possession.

You are his clothing or property to do with whatever he pleases.

So at that same connotation, your mind, your soul, your body, your thoughts, your fears, your inhibitions, your desires, they no longer belong to you.

They belong to the person that you submitted to and it’s very difficult for a lot of people to come to terms with that because they lose their independence.

Seagulls: In conclusion, the sexism and the depiction of slavery, sexual or otherwise, in this book is fairly toxic.

Probably only those belonging to a certain sexual subculture would read this and Fifty Shades of Grey, but it’s hard not to see them as originating from the same sort of inspiration.

If you can shake off that mental shudder, you’ll find Tanzanman of Gore to be nothing like is expected, a maxim which holds true about just about every aspect of it.

The plot is better than expected, the characters are better than expected, the quality of writing is better than expected.

The relationship between Tal and Talina is probably the focus of the book, motivating Tal as it does even when the two are separated.

Not even 1% as explicit as Fifty Shades of Grey.

They are a much more engaging couple than Steel and Grey.

When not veering towards abuse or even being generous **** their relationship is a quite reasonable, occasionally enjoyable, transition from sparring to affection.

John: There is nothing noble about being so emotionally weak that anyone you don’t dominate physically will be able to take advantage of you.

Norman likes to make the argument both in the books and elsewhere that this savage patriarchal rule was necessary the good of society if there is one positive in the Gore novels it is that it will compel the reader to rise to the occasion and to articulate precisely why they disagree with Mr.

Norman and if on a personal note um why do you love Gore so much and what does being a K how is how is that you know G for me was.

Brandy: The secret to the world that I didn’t have.

It was like learning who I was all over again.

I’ve never been in a community where I strived so hard every waking moment to study and learn and just retain information.

It was like a, it’s a drug.

You can’t stop because once you are pleasing and once you do get that attention, it’s It’s addictive.

You don’t let that go and it’s not the same as when a **** master looks at you or even a vanilla person looks at you.

Like, when a Gorean looks at you, feel it. You know in your heart that this is a different dynamic and that like, you get to be the real you don’t get to be anywhere else.

obviously, my books answer to certain deep needs in human beings.

If they were not important to people, if they did not have something important to say, something which apparently desperately needs saying, they would not be as popular as they are.

Now, this type of claim is very difficult to make about comedy.

I could say that when I was a child, I responded to the comedy of Chris Rock, stand-up comedian, because it spoke to certain repressed political problems that existed in downtown Toronto, Canada.

Most obviously, the shadow of the Black Panther radicalism of the 1970s and the divisions between black and white, ethnic conflict, and this kind of thing.

There was something I could say that his comedy, that it meant for me, that made this seem empowerful and important.

But to make these kinds of generalizations, even with comedy, even with something as explicitly political as comedy can be, is incredibly dangerous.

I mean, if we’re being honest, why did Chris Rock become so popular? Did it have nothing to do with the fact that he makes a lot of jokes about cheating on his wife and sleeping around? It’s just an incredibly fatuous, self-serving path we start to go down when we try to justify what appeals to us, even in comedy or even in politics, as representing something profound for all human beings, or something that shifts in our own time and as I’m suggesting here with this illustration, It’s much, much more surreal, much, much more self-serving and delusional when we say this about *********** rather than when we say this about comedy or something with an explicit political message.

On screen there, I’m contrasting two women who were respectively the most successful pornographic actresses in their time.

One is Eva Elfie and one is Jana Michaels.

So about 12 years apart, these women were the leading pornographic stars.

What can you read into this? What, you know, okay, I could try to construct some kind of social commentary, like, well, you know, 12 years ago, hip hop music was going through this period where, you know, female body image linked to rapid.

You can try.

You can try.

But you know what the truth is? There’s absolutely nothing we can read into this.

At any given moment, including right now, you can Google around the internet and you can find a dozen women who look just like Gianna Michaels and a dozen women who just look like Ava Elfie, just very similar looking people, who never became stars, who never became wildly popular.

You can find all kinds of cross-currents in culture that way, but especially in something that blatantly appeals to the ****** right? But there is no rational explanation for why one person was a successful actress and another person was not.

Why one person became famous and another person languished in obscurity when they were just as beautiful or what have you and you know why? Because desire is irrational.

Desire is the most irrational and arbitrary part of human nature.

But if you’re looking at the cover of the gore books, if you’re looking at these pictures of women in bikinis with swords and so on, it doesn’t take that much imagination to figure out that yes, indeed, we’re dealing with the ****** pornographic, desiring side of human nature that irrationally fastens on one woman and becomes fascinated with her and makes her famous and makes her the most famous sex symbol of her generation and fails to fasten on another, all right? The arbitrariness of fame is quite surreal if you’re talking about comedy or action movies or adventure movies.

It’s already arbitrary enough.

But when you step into the blatantly ****** when you step into the realm of *********** the extent to which it’s arbitrary, irrational, and not susceptible to analysis.

It is on a whole other level.

Let’s not go any further with quoting the interviews with John Norman.

Let’s not go any further with the philosophy of John Norman in his own words, without a little soups all, a little taste of what it is you’re missing out in these books.

What it is that he characterizes as having so much profound intellectual content, transforming our civilization, et cetera, et cetera.

In this book, Norman continues his pattern of storytelling, interspersed with detailed explanations of how to train a slave, how to make a lawn blow, how to train a slave, how to make a ship, how to train a slave, how to fight naval warfare, how to train a slave.

Did I mention how to train a slave? This guy is joking about the extent to which these books incredibly repetitiously try to inculcate this philosophy of male dominance of female slaves into the readers.

He’s joking about it, but notice at the top of the screen, four stars.

Many of the harshest critics of the Gore series are people who openly admit they love the books, they enjoy the books, but they can admit and they can joke about the extent to which this is really kind of perverse and bizarre and repetitious and reflects some kind of monomania or insanity on the part of the author.

Another four-star review for the same book.

Taro has a bit of an existential crisis and even though I like this book, the reason behind it was handled very poorly and so out of character that it is laughable and he decides that money is what he wants in life, and so he becomes a pirate.

Arrr.

Tarl suddenly has no problem with torturing his captives.

He also has no problem with keeping lots of slaves and pimp slapping them at will and going beast mode on them at the slightest infraction.

Despite the big tonal shift, I actually like this entry into the Gore canon.

Although much of the old recipe is still in effect here.

Tarl meets Woman.

Woman and Tarl are mean to each other.

Tarl and Woman eventually fall in love after Woman realizes how awesome slavery is.

Again, this is a critique coming from someone who loves the books and who appreciates what the author does intellectually or in terms of providing a good adventure story, whatever it is he may appreciate.

This isn’t someone who hates the books, but this is someone who can admit how deeply flawed they are.

Readers of the books, whether they love them or hate them, debate at what point the series started to go downhill, at what point the authors Sexual, political, and philosophical obsessions started to destroy the quality of the books, but many of them would name this specific book, Raiders of Gore, as the turning point.

Prior to this, there was at least some ethical tension in that the main character in the books disapproved of slavery and as you’ve just heard from this book forward, after he briefly becomes a slave himself, he 110% embraces slavery and this becomes a univocal soapbox for the author to preach his pro-slavery, pro-rape, pro-violence to women views without the ethical ambiguity that was provided by having a main character, even a narrator, who in the earlier books at least felt some kind of misgivings about embracing that ethos.

From a website called Books Without Any Pictures, Based on reviews I’ve read, there’s a point where the series starts to go way downhill.

I’ve definitely reached that point.

It also represents a major departure from the series thus far, because instead of focusing on Carl Tabbot, the hero of all the previous books, it instead chooses to use an Earth woman as the protagonist, Eleanor Brinton, a rich ***** New York City socialite who hates men.

That’s her defining personality trait.

Her only personality trait, even.

One night, Eleanor is captured and taken to Gore, where it’s pretty obvious what happens to her.

She quickly learns that on Gore, women have no social status, and she changes hands between a variety of different men.

Here’s A one-star review.

If you are into domination and submission, then this is the book for you.

If not, it will bore you out of your brain, despite the rather well-crafted science fantasy world the story inhabits.

There is page after page of stuff like this:

Naked and in chains, humiliated, spoiled rich ***** lifts her head and rages, I am not a slave, I am not a slave.

Barbarian hunk roars and strikes her across the face and then kicks her in the guts.

Say you are a slave, *****.

Sobbing, humiliated, spoiled rich ***** hangs her head and says, I am a slave, I am a slave.

I kid you not.

That is the book, and I’ve just saved you a lot of time.

Another one-star review.

Everyone said that this book marks the point that the Gore novels start going downhill.

As a big fan of the novels, I didn’t want to believe it.

Well, let me tell you, this novel is awful.

Here is the plot in a scene which is repeated over and over and over.

Girl: I am not a slave.

Man: you are a slave.

Girl: okay, I am a slave and it feels so right.

The end.

This book represents something of a turning point in this series in terms of its misogyny.

For the first time, I think, it actually mentions the concept of rape.

Previously, the book series was coy about it, using euphemisms like taking, possessing, enjoying, etc.

But in this book, it actually mentions rape directly or explicitly.

Likewise, this book portrays actual violence against the women being hunted slash enslaved, a particular unfortunate being shot through the shoulder and pinned to a tree by an arrow.

It also describes in greater detail the physical maiming inflicted on women who do not adequately adapt themselves to their lives of sexual enslavement.

This is also the most sexually explicit of the books thus far.

Previously, the narrative would always pan to the moon or fade to black whenever a sexy time begins.

This book gets a little braver before cutting away.

Which is, of course, one of the most baffling things about this series.

Yes, it’s all about male dominance and the glorification of rape culture, literally, “fuck her until she loves you”

But it doesn’t bother to realistically portray the psychological slash emotional ramifications of this behavior.

What fun would that be? So it is clearly a fantasy for those who enjoy that kink.

But why is it that he’s so shy about the actual sex?

Many of the reviews ask this, like, why does it not actually describe the sex? You get all these descriptions of chains, chains and whips and the procedures of enslaving people, but then the sex itself, the author seems to be uncomfortable actually describing beyond the use of some vague euphemisms.

Slave Girl of Gore gets a one-star review.

Any reviews of this book have to begin with a comparison to Captive of Gore.

Captive of Gore was the first book in the series to be narrated by someone other than Tarle, being narrated by an Earth female captured and taken to Gore as a slave.

Just want to pause to note, absolutely, by definition, none of this is about **** because none of this is about people consensually having sex or playing games.

This is not about consensual sex between adults.

This is about people being abducted, kidnapped, taken captive, brutally raped, etc. Okay? This is very clearly and explicitly not about consensual sex.

So anyone who happens to click on this video who’s a fan of these books, Please accept the fact that is what you are in the position of making excuses for.

You’re actually making excuses for a political philosophy that’s asserting people genuinely violating one another’s consent, taking people captive, enslaving them, et cetera, is... for the victim’s own good, because, John Norman argues, inwardly and secretly, that is what women want, even if they don’t know it yet, until after this traumatic experience happens to them.

So she is an Earth female, taken captive and relocated to Gore.

This is essentially the same story as the earlier book, Captive of Gore.

In Captive of Gore, we have Eleanor Brinton, a rich ***** socialite, who is beaten into submission until she likes it.

In Slave Girl of Gore, we have Judy Thornton, a college student taken to Gore and raped into submission until she likes it.

There are a few differences between the books that are noteworthy.

One of the main differences in the books is that while Eleanor, in the earlier book, resisted her slavery, mostly through whining and screaming, Judy, in the later book, took to it quickly, too quickly.

Judy is literally melting in the hands of her rapists and, quote, realizing her place, close quote, within hours of being drugged and transported to an alien world.

While Eleanor remained in shock for much of her own story, which is more believable, and was constantly crying, plotting, and scheming to get out of her predicament, Judy instantly converts from a naive, virginal, opinionated college student to a gushing, love-starved, submissive sex slave.

Both books, however, make the same point about that conversion.

It’s what women really want.

A subtle difference between the books is that Captive of Gore took an approach that some women just don’t know what they want, and all you have to do is beat them and rape them until they realize it.

However, Slave Girl goes further than Captive by claiming that all women are submissive and natural sex slaves, and they can’t wait to show you.

Norman steps up this rhetoric from book to book.

At least he’s consistent.

In this video, we’re not going to judge a book by its cover.

We’re not going to judge a book by its book reviews.

We’re not going to judge a book by the response of its fan base or its detractors.

We’re not even going to judge a book by taking select quotations of the original text out of context.

We’re going to judge the book by the stated intent of the author and let’s never forget, John Norman was a career professor of philosophy.

He taught philosophy, he wrote philosophy, and then he started this side project, writing the books, the science fiction world of gore, that increasingly took over his life as the years went on and why? What was so rewarding him of this? Was it for him? Just a fantasy? Was it for him? Just a hobby? Was it the fame? Was it the adulation of at least thousands if not millions of fans? Was it the possibility of a connection to Hollywood and at least two movie adaptations? What was it? What you’re going to find in these interviews with John Norman is that he took himself incredibly seriously as a writer.

That he was motivated not just to reach out to people and change their minds and maybe change their sex lives by sharing his fantasies with them.

He really felt that he was out here trying to change the course of Western civilization.

From his perspective, he was trying to save the world. I kid you not.

1996 interview with New York Review of Science Fiction by David A. Smith.

Smith, the interviewer, says, I wonder if what upsets people is not the content of the books so much as their author.

After all, you were a man writing in part about the glories of dominating and enslaving women.

To this, John Norman responds, That is an important and interesting strand of the Gorian fabric, but it is only one strand.

An entire world is created here with languages, cultures, artifacts, politics, religion, costume, cooking, military strategies, weapons.

Oh, he alternates between boasting about the graphically sexual, violent nature of the vision of an alternate reality, an alternate future for planet Earth that he’s presenting here.

He alternates between boasting about it and this very evasive, cagey, dishonest sort of reaction, right? And I give a lot of credit to this interviewer.

He doesn’t let Norman wriggle out of it here, right? Like, oh yes, well, dominating enslaved women, that’s just one strand of the fabric.

That would be like pretending it’s just what happens to be on the cover, but as if the rest of the books were really concerned with, as he says, politics, religion, costuming, cooking, military strategy, weapons.

Keep in mind, John Norman, born in the 1930s, still alive today and still writing books in the 2020s, has he and his books addressed any of the major political issues that arose in his lifetime.

He lived through World War II. He lived through the Cold War, the rise and fall of the Soviet Union, right? The rise and fall of Mao Zedong in China, all right? The end of the British Empire, British colonialism, then the emergence of new nationalist movements, including pan-Islamism, pan-Arabism, you know, the increasing importance of Islam in Western politics, right? September 11th and so on. He’s lived through all of this.

When he says he’s interested in politics, religion, et cetera, is there any evidence of that in his books? And then on the contrary, as we’re going to discuss through this video, is there evidence that he has this unique belief in the significance of relations between the genders and that our society must be transformed to reflect the true inner nature of women and the kind of relationships they secretly inwardly want for men.

That is very clearly the exclusive obsession of his books, and that’s the key to his philosophical and political belief that he’s doing something profoundly meaningful in making a lot of money out of some pretty sick and twisted science fiction fantasy here.

The interviewer continues and I highlight it.

I highlight this obscure issue that your books are completely obsessed with, you know, domination.

Domination of women by men exclusively, never the other way around.

I highlight it because female sexual slavery seems to me such a prominent element in the novels.

Lots of credit.

Lots of credit to the interviewer.

Plenty of people would let him just wiggle out of this line of questioning, which is already what he’s trying to do, right? And in the reactions they generate.

The Gorian novels imply that women want this whether they know it or not.

Norman replies, well, there are plenty of folks, such as Anne Rice, who are writing material which is far, far more ******.

Anne Rice’s Sleeping Beauty trilogy is light years beyond anything I would do or even think of doing.

Yet Mrs.

Rice is a heroine to many feminists and is published by one of the houses that refuses to so much as look at anything by John Norman.

So he’s being very directly asked, about sex slavery in his books and then we have another form of dishonesty and innovation where he’s trying to make the issue that he’s a victim of censorship by feminists.

There’s a lot of that material in his interviews and I hate to say this, guys, but if what he were saying here about Anne Rice’s novels, Anne Rice is most famous for vampire novels, if that were true, it would still be completely, utterly irrelevant, right? Like if Anne Rice writes sexy vampire novels, you didn’t answer the question of the fact that you devoted your life to glorifying 1 particular type of slavery and rape.

Interviewer, you are saying that gore is an emotionally healthier society, that it’s emotionally healthier than our own in the real world in the 21st century? Norman’s reply, well, for example, some men in our world seem to want to hurt women.

These things are incomprehensible in a Gorian world.

But they make some sense in our world, a world in which natural relationships tend to be denied and you’ve heard that asks, Denied how? Oh, you’re giving him just enough rope to hang himself.

John Norman leaps at the chance to answer that question.

The male, cheated of his manhood, desires to inflict pain and revenge.

The female, cheated for womanhood, accepts and perhaps even desires pain, perhaps to punish herself for deserting her deepest self.

Really think about what he’s doing here.

Directly, he’s lying to you.

He’s being deceptive, dishonest, evasive, and lying.

He is directly lying to you in claiming that men do not hurt women in his fictional world of gore.

All right? That is a lie.

But he’s also inviting you in a very real sense to blame the victim in our world.

That women who are the victims of rape and sexual violence That in fact he’s suggesting we should instead feel sympathy or pity for the men because they are quote unquote cheated of their manhood and desire to inflict pain and revenge because of this sickness in our modern society that he, alone, John Norman, is trying to solve.

Just how much of A lie is it? Just how dishonest is it for him to say these things are incomprehensible in the Gorham world? Nobody gets hurt in his fabulous fantasy.

It would be easy to imagine some other author writing a book based on their own sexual fantasy or even based on their political philosophy, which Norman is here doing, where nobody gets hurt.

In fiction, anything is possible.

Quote, Misogynist Manifesto.

This one-star review really means zero.

The book asserts that what all women, including intelligent, well-educated women, really want is to be abused, degraded, humiliated by powerful, brutal men, and shared with other men.

The women begged to be sold into slavery rather than killed.

You can guess what the alpha males decided and he notes that he is a male reviewer.

This is the single most sexist book I’ve ever read.

I’m a guy.

Still, this entire thing is offensive and degrading to women.

The ideas behind the story could have led to an interesting sci-fi take on time travel.

Instead, it’s mostly about rape and subjugation of women.

This all sounds pretty standard and it is.

But right around page 50 is when Norman starts in with his bizarre dom-sub-philosophies.

So the whole story becomes murky.

Before Hamilton can be sent back to the distant past in the hopes that she will join a group of Cro-Magnon men, her will must be broken by her Yellison’s lackeys until she is deemed ready for the submissive slave-like existence.

For the submissive slave-like existence that awaits her.

Here’s the old Crank’s explanation to Hamilton before he shoves her into a box for a one-way trip to the Stone Age.

You must understand, said Hellerza, that if you were transmitted as a modern woman, irritable, sexless, hostile, competitive, hating men, your opportunities for survival might be considerably less.

I’m a prisoner, she said, and I want to be ****** like a prisoner, used!

Time Slave wouldn’t be a John Norman book if women didn’t revel in their captivity, which brings us to the middle of the book where things get real.

Brenda Hamilton, transported to an unfamiliar time, is naked and running through the forest with a leopard in pursuit when she runs into Tree, a red-blooded Cro-Magnon hunter.

At page 143 is the first of many very unfortunate rape scenes in this book.

Some go on for pages.

None are really necessary.

The next 100 pages chronicle Brenda’s transformation from a caricature of a fully realized woman to a whimpering, sex-obsessed slave.

Of course, this being a John Norman novel, she revels in this change and feels that she has finally become a true woman, in quotation marks.

For the first time in her life, she felt the fantastic sentience of an owned, loving female.

She had just begun under the hands of a primeval hunter to learn the capacities of her femaleness.

Regrettably, more than half of this novel is lent to Norman’s **** leadings, which involve A repetitive, preachy tone, because the man is literally trying to convert you.

How can he say that in our world, some men want to hurt women, whereas in his fictional world, This is inconceivable.

Frankly, how dare you, John Herman? The interviewer asks, Elsewhere, you have made the point that Gorian society is decentralized and pluralistic.

Would you want a Gorian society to actually be created? His reply, It seems possible that a Gorian world might be the best possible world empirically, given human realities.

it would not be a utopian world.

Now, apart from the obvious and important questions of morality and ethics here, like sex slavery being the ideal way to reorganize society, you wouldn’t prefer to live in a world that had electricity, flushing toilets, paper, pencils, pens.

Like, Why would this one factor of having access to sex slaves and being in a society that normalizes this kind of rape and violence towards women, why would that one factor alone make this, quote, the best possible world empirically for human nature? The interviewer, I give him a lot of credit, presses this point that obviously John Norman has spent his whole life evading.

Many people who express tolerance over people’s private lives and private fantasies become militant if those philosophies are forcibly imposed on others.

So this is asking the right question, the crucial question, in the most polite and tactful way imaginable.

The interviewer’s saying very clearly, we’re not talking about fantasy.

We’re not talking about dress-up playtime between 2 consenting adults, middle class, bourgeois, decadent people who just want to pretend to be slaves or pretend to be ****** each other.

We’re talking about actual rape, actual slavery and a political philosophy written by you, John Norman, that glorifies and propels these things as the greatest possible society, the most suitable for human nature.

John Norman replies,

The philosophies of statism, authoritarianism and collectivism are being imposed forcibly on the American people by the bayonets and guns of the state.

Sound a little bit familiar? John Norman’s biggest secret was the extent to which he was ripping off Ayn Rand.

Ayn Rand is a terrible writer to begin with and a terrible philosopher and a terrible economist. It’s a whole other story. But if this kind of verbiage doesn’t sound familiar to you, take a look at Ayn Rand or what her immediate followers and fans have to say about life in the 20th century United States of America.

Oh yes, what a deep analysis of what America was like from 1980 to 2020, the American people being forced by the big nets and guns of the state.

Does this even sound like someone with a PhD in philosophy offering a critique of the life of the contemporary United States of America? But this is how he justifies his own mission to save the world, his own mission to liberate his fellow man from this repressive regime that won’t let people enslave and sexually dominate one another.

Appendices

John Norman of Gor interview (1980)

John Norman (aka John Eric Lange) interview

Source: Questar magazine, February 1980.

JOHN NORMAN

THE CHRONICLES OF GOR

QUESTAR INTERVIEW

by Dr. Jeffrey M. Elliot

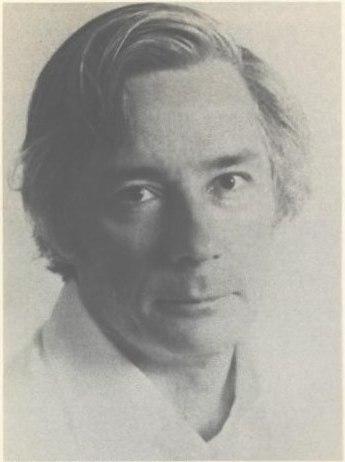

Who is “John Norman?” That question has baffled readers and critics alike for years. Indeed, rumors of all kinds have circulated as to the long-guarded identity of one of the world’s most successful (as measured by total book sales) science fiction-fantasy writers. Now, in this exclusive interview. Dr. John Lange, a.k.a., “John Norman,” answers many of the questions which have sparked this debate, questions relating not only to the author’s identity, but to his controversial “Gorean” series. For the first time in print, Lange sets the record straight, speaking first-hand about himself and his work, in what amounts to one of the liveliest and most provocative interviews of its kind ever published.

Having divulged Norman’s identity, the next appropriate question is: Who is “John Lange?” The answer to this question was equally difficult to come by, but the facts below are as accurate as could be gleaned.

Dr. John Lange was born in Chicago, Illinois, on June 3. 1931. Lange is married and has three children, two boys and one girl He is a professor of philosophy at Queens College of the City University of New York, in Flushing, New York, where he specializes in the areas of epistemology, logic, and innovational conceptualization. The author received a B A from the University of Nebraska, an M A from the University of Southern California, and a Ph D. from Princeton University. Lange has published several scholarly works, including The Cognitivity Paradox: An Inquiry Concerning the Claims of Philosophy (Princeton University Press, 1970) and Values and Imperatives: Studies in Ethics, by C.l Lewis (Stanford University Press, 1969), which he edited.

Lange has worked, at one time or another, either part-time or full-time, as a radio announcer and writer for KOLN, Lincoln, Nebraska; a film writer for the University of Nebraska; and a story analyst for Warner Brothers Motion Pictures, Inc., in Burbank, California. He has also worked as a technical editor and special materials writer for Rocketdyne, a Division of North American Aviation. Inc., specializing in the production of rocket engines.

The author’s first professional sale was a radio script to a station in Lincoln, Nebraska, when he was in high school, or somewhere thereabouts. Under the pseudonym, “John Norman,” Lange has published a number of popular works, among which are the “Gorean” books. He Is a member of the Science Fiction Writers of America and the American Philosophical Association.

QUESTAR: Can you say how you started as a science fiction-fantasy writer?

NORMAN: I think this probably has something to do with one’s imagination and its nature. Certain sorts of imaginations probably lend themselves more readily to different literary genres. As a modality of self-expression, adventure fantasy seems attractive, rich, and natural to me. I’m sorry this is not a better answer. Why do some people paint, others compose music? And if one paints, why do some paint landscapes and others...? I do not think.I will attempt to respond further to this question.

QUESTAR: What is it about the genre, if anything, that accounts for your interest?

NORMAN: Let us suppose that a lion hunts antelopes. Does he hunt antelopes because there is something about antelopes that accounts for his interest? That sounds like a very rational decision process was involved. He probably hunts antelopes because he is a lion, and, being a lion, antelopes look good to him. Similarly, I suspect that I write adventure fantasy because I have a certain sort of imagination. Because of the way I am, perhaps, it looks good to me.

QUESTAR: Why did you decide to write under a pseudonym, as opposed to your actual name?

NORMAN: I have a family to support. At the time the first Gorean book was published, I did not have tenure at my academic institution. I did not wish to be denied tenure, and be out of a job, with no explanations given, but the reason being, perhaps, that I had dared to do something so academically disreputable as write science fiction. This situation has been ameliorated somewhat in the academic world in the last few years, but I think it is still true to say that, for the most part, it is academically customary to belittle and dismiss science fiction. For example, I think a young man or woman in an English department would do well, even today, to keep a low profile about an interest in science fiction, if he or she is interested in tenure, promotion, etc. To my mind, there remains today in the academic world a great deal of prejudice against the genre For example, at my own institution, science fiction, for purposes of fellowshipleave applications, does not count as “creative work.” That is interesting, I think, for science fiction and adventure fantasy are probably the most creative of the literary genres. If it had not been for the tenure probler.., I do not think I would have used a pseudonym. On the other hand, I think “John Norman” is an excellent writing name, and I am pleased with it My own name, John Lange, incidentally, is almost never pronounced correctly. That would seem a count against it, at least as a writing name. Furthermore, it, hilariously, is used by at least one other writer as his pseudonym.

QUESTAR: To what extent is John Lange knowable through his fiction?

NORMAN: I do not think I am qualified to respond to this question It is very difficult to know oneself, let alone worry about how aspects of one’s personality might be expressed in one’s work. Obviously, something of oneself must be involved in all honest creative work. On the other hand, I doubt that psychology is yet ready to make serious judgements on such matter. There are just too many unknowns in the equation, and it is difficult to control and correlate the writer variables, the analyzer’s variables, and the work variables. To be sure, anyone who has read the Gorean books surely knows me better than if he had not read them On the other hand, it is necessary to read the books intelligently and honestly. If the books are read unintelligently and hysterically, the result, I think, would be that the reader would finish up knowing very little about either the books or me.

QUESTAR: Unlike most writers, you have studiously avoided publicity. Why?

NORMAN: I have not, perhaps, as studiously avoided publicity as many people think. I have, for example, publicly addressed various science-fiction conventions and various science-fiction groups. On the other hand, I think it is quite true that I have not made a practice of actively seeking publicity. First, it is not my nature to do so. Second, as is no secret, various individuals in the science-fiction community bear me great hostility. This is obvious in emotive, abusive, slanderous reviews. Accordingly, I see no point in entering more actively into the affairs of the science-fiction community It is natural, incidentally, for these individuals to wish to control and limit science fiction. That I outsell them, say, forty or fifty to one, also, has perhaps contributed to their pique. Some of these individuals take themselves very seriously, in spite of their having no obvious justification in doing so. Some resent my extending the perimeters of science fiction into new areas, this perhaps seeming to reflect adversely on their own work, which might then, in contrast, appear unprogressive, sterile, and juvenile. It is popular to call for “new directions” in science fiction, but when one shows up, it seems that panic sets in. “New directions” usually means new wrinkles or variations on old variations or old themes, within the limitations of certain orthodox political structures. They are thrilled by new hardware, which is safe; they are terrified by an attempt to treat human beings honestly, rather than as Victorian abstractions. I do not bear these people ill will. They are doubtless as innocent as mice and rabbits. On the other hand, I think one of the reasons for the isolation of John Norman in the sciencefiction community, in spite of the fact that he is, I gather, the best-selling, or one of the best-selling authors in the genre, is to be explained in virtue of the hatred of a few individuals who wish to control, limit, and direct the destiny of science fiction. I think their power is unfortunate for the future of science fiction and, too, of course, for the future of up-and-coming writers who are not willing to spend years brown-nosing their way into the club. The John Norman phenomenon, however, indicates that their power is not complete. One may then similarly hope that many other new writers may, in their own chosen ventures, be fortunate enough to speak the truth as they see it. Not only are the old lies repetitious, they do not even sell very well. The writer’s hope is the readers, and their honesty^nd care for good writing. It is the readers, in the final analysis, who have made John Norman successful. In spite of what might happen in the future, for example, that certain individuals might eventually become successful in managing to fully implement the censorship implicit in their position, it will always be the case that, at least for a few years, something was done against them and beyond them which was itself, and was, in its way, whether correct or incorrect, proud and magnificent. The Gorean books exist.

QUESTAR: How would you characterize the kind of writing you do? Is it fair to label it “sword and sorcery” in content?

NORMAN: I dislike labels and categories. They can be useful, but often they become stereotypes, and one then tends to view matters not as they are, in their own fullness and uniqueness, but under the attributes of stereotypes. This is a cruel error where human beings are concerned and, logically, it does not improve in validity when the move is made to artifacts, musical compositions, stories, etc. The genre I write is, so to speak, “the Gorean novels.” They are, for most practical purposes, their own genre. If one had to use labels, I would think that something like “adventure fantasy” would be rather good. They are certainly not “sword and sorcery.” For example, magic is not involved in the books. Similarly, great attention is given to scientific verisimilitude, within, of course, artistic latitude. The Gorean books, incidentally, are one of the few productions in science fiction which take seriously things like human biology and depth psychology. I’m not announcing anything new if I point out that there is very little science, normally, in science fiction. Indeed, if one were merely interested in coming up with category titles which were more descriptive than “science fiction” of what actually goes on in “science fiction,” presumably one would speak of something like “engineering fiction” or “technology fiction.” Furthermore, what science, as opposed to applied science (e g., space ships, etc.), occurs in science fiction is usually limited to the physical sciences, or, in more knowledgeable writers, the social sciences. The human sciences (e.g., human biology and psychology) are usually avoided, perhaps because they involve areas “too close to home.”

QUESTAR: Do you have specific requirements when it comes to writing a story?

NORMAN: I once knew a musician who would ask himself the following critical question about his music, “Does it sound?” Not being a musician, I am not fully cognizant of what he may have had in mind, but, clearly, he was not asking if it was audible or not. I think he was suggesting that there was a “rightness” about it which might be difficult or impossible to analyze, but which, if attained, would be recognizable. His test of good music then was “whether or not it sounded.” It is hard to teach music on this kind of premise, but perhaps there is no other test or touchstone for excellence in that genre. Similarly, in writing, I suspect that all, or most, authors use a similar sort of subjective yet essential and significant test. “Does it sound?” Is it terrific? Is it marvelous? Does it make you want to leap out of your chair and scream with joy? More simply, is it good? Is it right? In this sense, I would like for my work to be “good,” to be “right,” indeed, to be “great.” Greatness is my objective. I would rather fail to have grasped a star than never to have lifted my head to the sky.

QUESTAR: Are you a meticulous writer? Do you do considerable rewriting?

NORMAN: Interestingly, the Gorean books write themselves. I do not know if other authors have this experience or not. I hope so, for it saves a great deal of work. The Gorean books are not put together like shelves, according to outlines or plans drawn up beforehand. They are more in the nature of organic products which grow. They are more like flowers and trees than reports and machines. I know when a book is ready. Then I sit down and watch it unfold. I am sometimes an amazed, delighted spectator. It is like something going on over which I have very little control. It is more like a welcome gift. Why should I ask questions? If the book is not “there,” then I do not know if it could be written or not. I have never hacked a book. When a book is ready, I have humbly accepted it, gratefully. On the hypothesis that these books are not dictated through me by some foreign intelligence, which would seem pretty screwy, I must suspect that they are very deeply related to subconscious creative processes. I am pretty much, perhaps unfortunately, at the mercy of such processes. As the Eskimos say, “No one knows from where songs come.” I do, of course, before turning in a manuscript, do some revising and some rewriting. I can sweat blood over commas, like any other beleaguered writer. On the other hand, if my information is correct, I probably expend fewer dues for literary torture than many authors. I hope so, for it sounds as though some of those fellows really suffer. I have nothing against suffering, incidentally. I just don’t care to do it myself.

QUESTAR. Given what you write, do you feel any special obligations to your readers? If so, what?

NORMAN: I have general obligations to human beings, and I have obligations to myself. I have special obligations to my family, etc. I am not clearly aware that I have special obligations to my readers, beyond those which I would have towards other human beings. I hope, of course, that they will enjoy my work. I do not think I have an obligation to please my readers, for example, but I would naturally hope that I would. In the final analysis, I write for myself. I wish to please mostly myself. If an artist cannot be true to himself, how can he be true to anyone else? I think my readers expect me to be honest to myself. My first obligation is thus to truth and integrity. If I can fulfill this obligation, I think then that my readers, or most of them, will be satisfied.

QUESTAR: How do you view your role as a writer—entertainer, observer, reformer?

NORMAN: I do not think of writing as a “role.” Similarly, I do not think of eating and sleeping as roles. Writing is something which, for me, is very natural. Accordingly, it is difficult for me to try and answer this question. I write primarily for myself. I wish to please myself. I wish to come up with something great. Therefore, I do not primarily consider myself in “other-related” roles (e.g., as an entertainer, reformer, etc ). One must be aware of defining oneself in relation to others. I am myself. So are most other people, if they only knew it.

QUESTAR: How much would you admit to modelling your characters on real people?

NORMAN. This seems an oddly phrased question. There is a sense in which I suppose most literary characters are modeled on “real” people. This seems something less to be “admitted” than something which it would be difficult to doubt. To be sure, characters, if interesting and believable, must have “real” characteristics, the characteristics of “real” people. One of the problems with much science fiction is that the background, perhaps because of its exotic nature, tends to intrude too much into the story and often distracts from elements such as plot and characterization. I think characterization, in particular, is difficult for many writers in science fiction because of the unusual “scenery” involved. It is hard to get involved with a particular character when unusual appliances and gadgets are clicking and blinking, and whistling and zooming in the vicinity. This is an advantage that more pedestrian genres usually have over science fiction; that the background, because of its prosaic nature, can commonly be taken for granted, and the author can concentrate on character development and conflict. One of the strengths of Robert Heinlein, I think, is his capacity to handle characterization. Aside from his own considerable talent, one of his devices in this matter, it seems to me, is not to bite off more than he can chew in the matter of a specific background at a specific time. The background in Heinlein commonly gives us an enhancing setting for human concerns. In Heinlein, people are there, really. In certain other authors, things seem to take precedence over people; such authors are perhaps less interested in people than in things. From my own point of view, I find both interesting. People, however, I must admit, come first. Incidentally, in the case of the Gorean books, the backgrounds are usually simple enough, and familiar enough, from the past history of Earth, and easily understandable extrapolations of barbaric cultures, to be fairly unobtrusive. Gorean backgrounds, thus, seldom distract from the interpersonal relations involved. Indeed, a great deal of attention is often given, in Gorean novels, to interpersonal interactions, sometimes of a dramatic and interesting nature. Similarly, character development is extremely important Most characters in science fiction, as you know, begin as, and remain substantially, the cardboard stereotypes of juvenile hero literature. Indeed, one of the difficulties which some people have with the Gorean books is that their familiar and predictable stereotypes do not occur The Gorean books present an ethos which is not that of most Earthlings, and, indeed, one for which a great deal is to be said The Gorean books suggest that human beings dare to think truly alternate realities, not just the old realities projected into an exotic environment Perhaps the fear to do this motivates some of the abusive and hysterical reactions which the Gorean books have aroused. It seems tragic when individuals who are supposedly original and daring thinkers, by profession even, are suddenly revealed, in basic matters, to be truly afraid of thinking. Or, perhaps it isall right to think about machines; it is only ourselves, perhaps, about which we must not dare to think. Thought, of course, is dangerous. It is the instrument of change.

QUESTAR: What degree of reality do your characters have for you after you have finished writing about them?

NORMAN: This seems something of an odd question, too. The characters in the Gorean novels, for what it is worth, seem extremely real to me. I am confident that I know how they feel about things, where their “heads are at,” and how they would be likely to respond in given instances. I suspect any author feels this way about characters. If the character is not real, it seems it would be difficult to write about him, or her, or it. Surely, the reality of such a character does not cease when one ceases writing about him.

QUESTAR: Do you write with a particular audience in mind? Do you tailor your work for this audience?

NORMAN: Perhaps I write because I have to. If that is the case, then questions about particular audiences, etc. become somewhat irrelevant. I do, of course, wish to please myself. Perhaps this is relevant. This might be a good point to mention a theory I have about literary selection. The analogy, of course, is to natural selection. Let us suppose an animal is born with a certain set of physical properties and behaviorial dispositions. Obviously, these properties and dispositions will influence its survival in a given environment For example, in some environments, thick fur and certain serum may be of value, while in other environments thin fur and different serum factors. Genetics, so to speak, throws the dice and the environment selects the winning numbers. A similar phenomenon occurs in evolving social and technological environments. Hero of Alexandria, in the Second Century B.C., constructs a novel toy; James Watt, in the Eighteenth Century A.D , building on the work of earlier inventors, designs an improved steam engine, and alters the nature and direction of human civilization. I think a similar phenomenon has occurred with the Gorean books. I have done what is right and natural and honest, at least from my own point of view. I have not attempted to please critics or conform to a market. I have been myself. I think this comes through in my writing. I am self-directed, rather than other-directed. I have kept my integrity. It has been my good fortune that the Gorean books are apparently needed in our contemporary civilization. Obviously, they answer to certain deep needs in human beings. If they were not important to people, and if they did not have something important to say, something which apparently desperately needs saying, they would not be as popular as they are.

QUESTAR: How would you describe your audience? Who buys a John Norman novel?

NORMAN: It is difficult to answer this question without market research. Fan mail, of course, and sales in special outlets, such as college bookstores, provide us with some evidence. My impression is that the Gorean books are read and enjoyed by individuals of all ages and backgrounds. The sales, for example, for better or for worse, indicate that the audience for them extends far beyond the borders of the “science-fiction” community. They have been on best-seller lists many times, for example. Unlike the usual science-fiction sales of a few thousand books, if one is lucky, they have sold millions of copies. Incidently, Gorean books have been published in several languages Certainly, many women are avid fans of the Gorean series. Indeed, I think one of the contributions, not likely to be acknowledged, which the Gorean books have made commercially to the science-fiction field is that they have helped to open it up to female interest. In this sense, I think I have brought, or have probably brought, many new readers to science fiction, not only male, but also female. The success of the Gorean books, I think, tends to improve the sales of other science-fiction books, or adventure-fantasy books, by encouraging interest in the genre and enlarging its market. I, personally, am very fond of my audience. Their encouragement and support is deeply appreciated.

QUESTAR: Would you enjoy reading your own books? Do you read other authors who write in the same vein?

NORMAN: This is a hard question to answer, because I have written the books. It is thus hard to look at them objectively, as though, say, they might have been written by someone else. Since I think the books are marvelous and interesting, etc., I certainly hope that I would enjoy reading them. On the other hand, I can conceive of feeling extreme frustration, anger and disappointment if I read them, and had not written them, for then I think I would have wished that it had been I, and not the other fellow, who had written them. Perhaps I would be angry that he had “gotten there first “ I do not read other authors who write in the same vein. I might if there were any. I don’t know. John Norman, at least at the moment, for better or for worse, is the only fellow in his field. My field, of course, is my sort of novel, that sort of novel which I have pioneered. I am tolerant of diversity in the science-fiction field, incidentally I do not have a set of a priori notions as to what counts as science fiction or not; I do not limit myself to certain traditional paradigms of propriety. I encourage each author to be true and honest to himself. The major danger which science fiction faces is selfimposed limitations, probably largely functions of psychological and cultural blocks.

QUESTAR: How much research, planning, and study do you do before sitting down to write?

NORMAN: As with most authors, my work is a result, at least in part, of resources accumulated over many years. As a youngster in high school, for example, I had an interest in ancient history. The first serious book I ever read, as I recall, was the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius. I remember reading it at the wrestling matches. Upon occasion, of course, specific research is in order for a given book; for example, in connection with one project or another, I have investigated, or deepened my investigations, of such matters as Roman naval construction, Medieval shipping, Viking sports, the economics of oases, Eskimo weaponry, and the flora and fauna of rain forests. I usually limit specific research to a dozen books or so and a few days’ time. After all, I am not writing, say, a novel of Napoleonic France, which would require incredible fidelity to historical details. I am writing adventure fantasy. The Gorean world, of course, has been heavily influenced by our world; on the other hand, it is not our world. Thus, there must be a creative contribution to the construction of the world. In that sense, in adventure fantasy, research must serve a purpose beyond familiarizing oneself with certain facts; one must not content oneself merely with the replication of past realities. Instead, one must consider how such things, in a different situation in time, might become altered or transformed. Indeed, perhaps new inventions, cultural practices, etc., would be developed. The major value of research, I think, in this sort of situation, is not to limit, but rather to stimulate and enrich, the creative purpose. Aside from questions of research, I do not do much pre-planning of my books. For example, as explained earlier, I prefer to let the book happen by itself, while I watch it. I am around, so to speak, while it is being written. I do, of course, generally have a background in mind, and sometimes a general problem or line of development. How can one make a map of territories he has never seen? How can he chart lands which he has not yet explored?

QUESTAR: Do you think highly of your own work? Are you proud of the Gorean series?

NORMAN: Yes, I think highly of my own work. It is the finest thing, of its sort, ever to be done in adventure fantasy. Whether or not one should be proud of one’s work, on the other hand, is a more complex and interesting question. The moral question here, for a humanist and a naturalist, is a knotty one. It is particularly acute in my case because the books, as I have mentioned, pretty much write themselves. I do not know if I should take credit, in that sense, for them or not. I welcome them as gifts. I do not know if I am “proud” that songs come to me. I am, of course, undeniably grateful.

QUESTAR: Do you have a favorite among your books? What makes it your favorite?

NORMAN: I do not think it is wise on an author’s part to respond to this sort of inquiry. One loves all one’s children.

QUESTAR: What is it about your novels that explains their tremendous popularity?

NORMAN: I don’t know. Hopefully, they are well written and exciting. Perhaps the readers find the Gorean world of interest. Perhaps the books touch on neglected or surpressed human constants, male and female. Perhaps they have something to say which has not been said for a long time. They are probably unique, or almost so, in modern literature, in raising serious questions about the intellectual superstructure of western civilization. They have intellectual content. There are ideas in them. Perhaps that is what so outrages some critics. Science fiction, however, or at least from my point of view, can be a literature with cognitive content. No one would deny that in principle, yet how few have troubled themselves to put it into practice. To paraphrase Nietzshe, the problem is not to have the courage of one’s convictions; that is easy. The problem is to have the courage for an attack on one’s convictions.

QUESTAR: Does writing serve a cathartic value for you? Does it teach you important things about yourself and what you prize?

NORMAN: I enjoy writing, and I’m happy when I do it. Perhaps some sort of cathartic value is involved. I do not know. I suppose it would be. I do not know. There are probably many values, of a diverse nature, connected with writing. I would also suppose that one knows more about oneself when one has written a book than before. Similarly, when one has written a book, I suppose one might be clearer about either what one has valued or what one has decided to value than one might have been before.

QUESTAR; How important is artistic excellence when it comes to your writing? Do you aspire to a certain literary standard?

NORMAN: I am not the sort of fellow who presents himself either as an “artist” or a “craftsman.” These seem to me vanity costumes. I am less concerned with being an artist or a craftsman than I am with writing the book. My focus is on the work, not myself. It has been my experience that those fellows who make a great deal out of themselves as being “artists” or “only humble craftsmen,” are likely to be either good artists or craftsmen than the fellows who forget about that role garbage and are work-oriented, not image-oriented. The real artist, or craftsman, is hard to find on the cocktail circuit; he is too busy in the studio trying to get some effect or another right. Does that sprinkling can belong in the picture or not? He may paint it in and out a dozen times. He is not worrying about his image; he is worrying about the sprinkling can.

QUESTAR: How do you respond to the charge that your books exploit sex and violence—that they debase and debauch the human spirit?