Fredrik Barth

Nomads of South Persia

The Basseri Tribe of the Khamseh Confederacy

1961

Chapter I: History, Ecology and Economy

Chapter IV: Tribe and Sections

Chapter VI: Attached Gypsy Tribe

Chapter VII: External Relations

Chapter VIII: Economic Processes

Chapter IX: Demographic Processes

Chapter X: The Forms of Nomadic Organization in South Persia

Nomads

of South Persia

The Basseri Tribe

of the Khamseh Confederacy

FREDRIK BARTH

Little, Brown and Company

BOSTON

© COPYRIGHT BY OSLO UNIVERSITY PRESS 1961

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. NO PART OF THIS BOOK

MAY BE REPRODUCED IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY

ELECTRONIC OR MECHANICAL MEANS INCLUDING

INFORMATION STORAGE AND RETRIEVAL SYSTEMS

WITHOUT PERMISSION IN WRITING FROM THE

PUBLISHER EXCEPT BY A REVIEWER WHO MAY

QUOTE BRIEF PASSAGES IN A REVIEW.

SECOND PRINTING

Published simultaneously in Canada

by Little, Brown & Company (Canada) Limited

The hard cover edition of this book is distributed in the United States of America by Humanities Press, Inc., New York, and in the British Commonwealth by George Allen & Unwin Ltd., London. This book is also published as Bulletin No. 8, Uni versite tets Etnografiske Museum, University of Oslo.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Contents

| I | History, Ecology and Economy | 1 |

| II | Domestic Units | 11 |

| III | Camps | 25 |

| IV | Tribe and Sections | 49 |

| V | Chieftainship | 71 |

| VI | Attached Gypsy Tribe | 91 |

| VII | External Relations | 93 |

| VIII | Economic Processes | 101 |

| IX | Demographic Processes | 113 |

| X | The Forms of Nomadic Organization in South Persia | 123 |

| Appendix I The Ritual Life of the Basseri | 135 | |

| Works Cited | 154 | |

| Index | 155 |

List of Figures

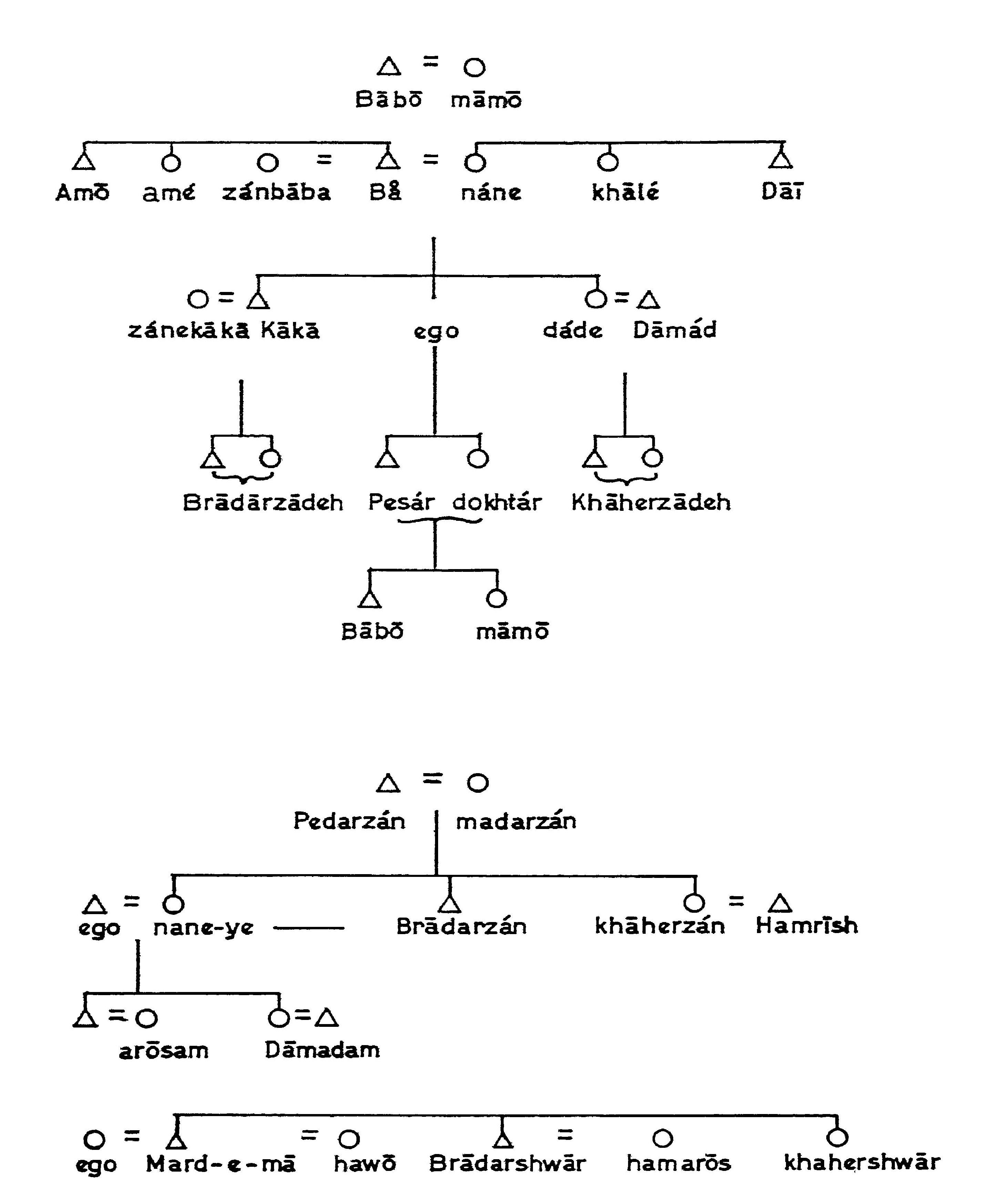

| FIG. 1 | Colloquial kinship terms of the Basseri |

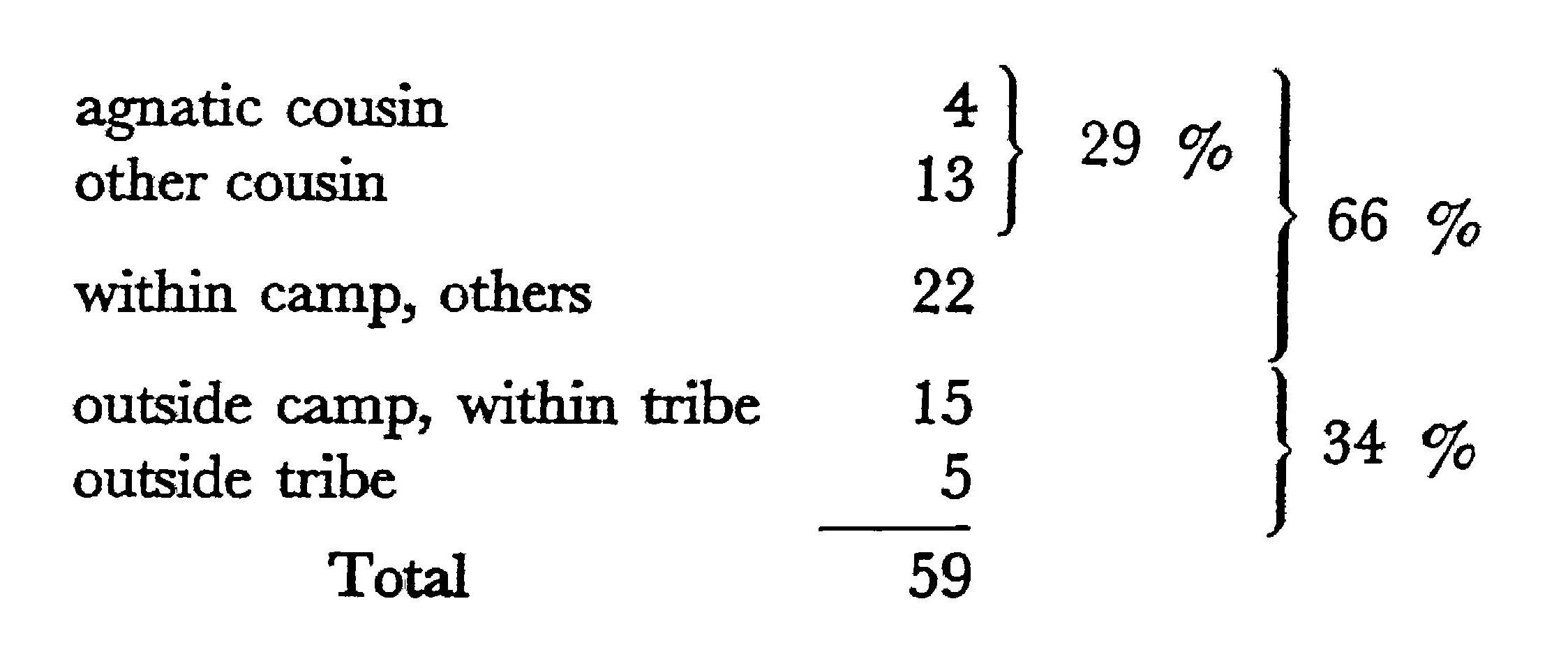

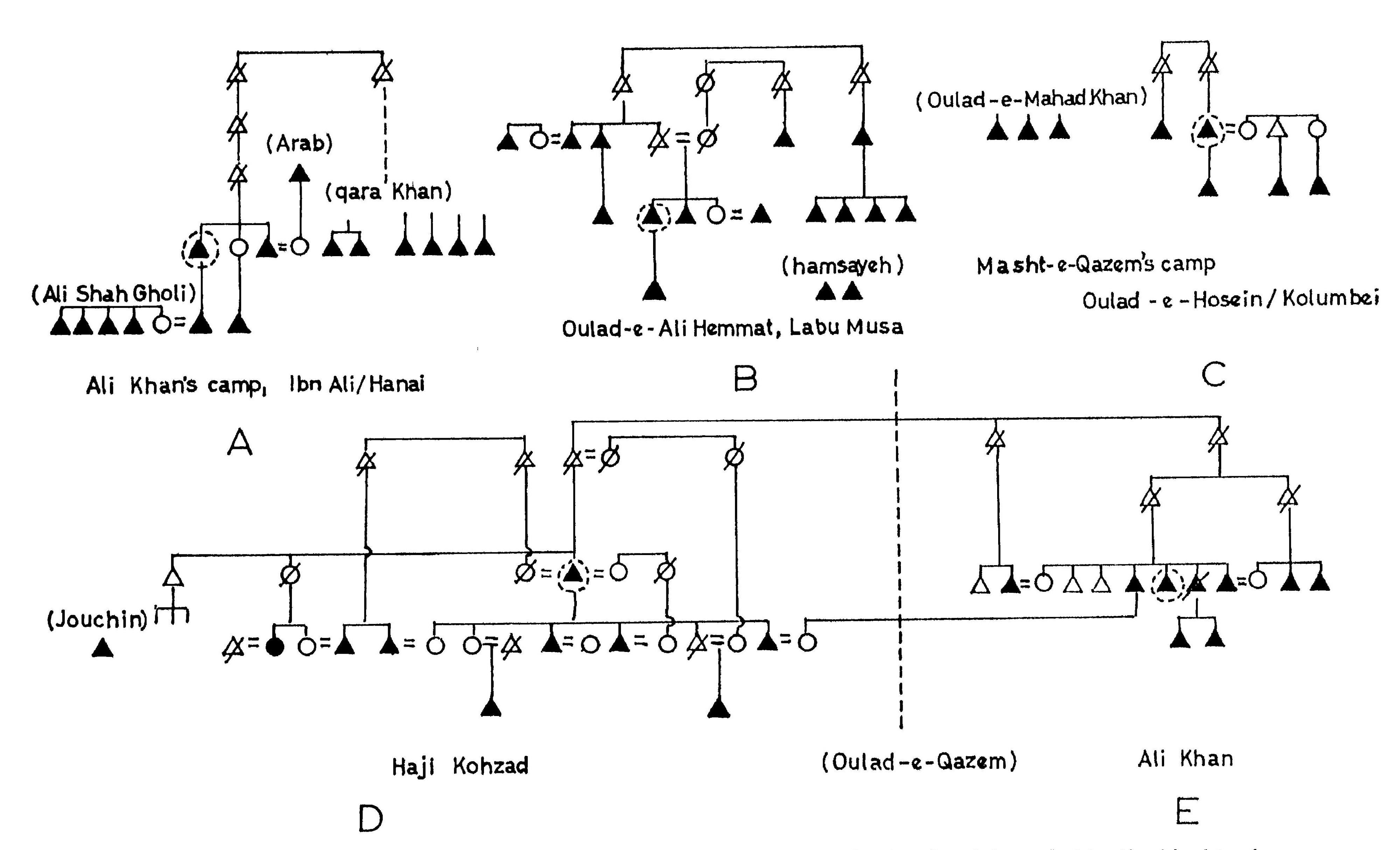

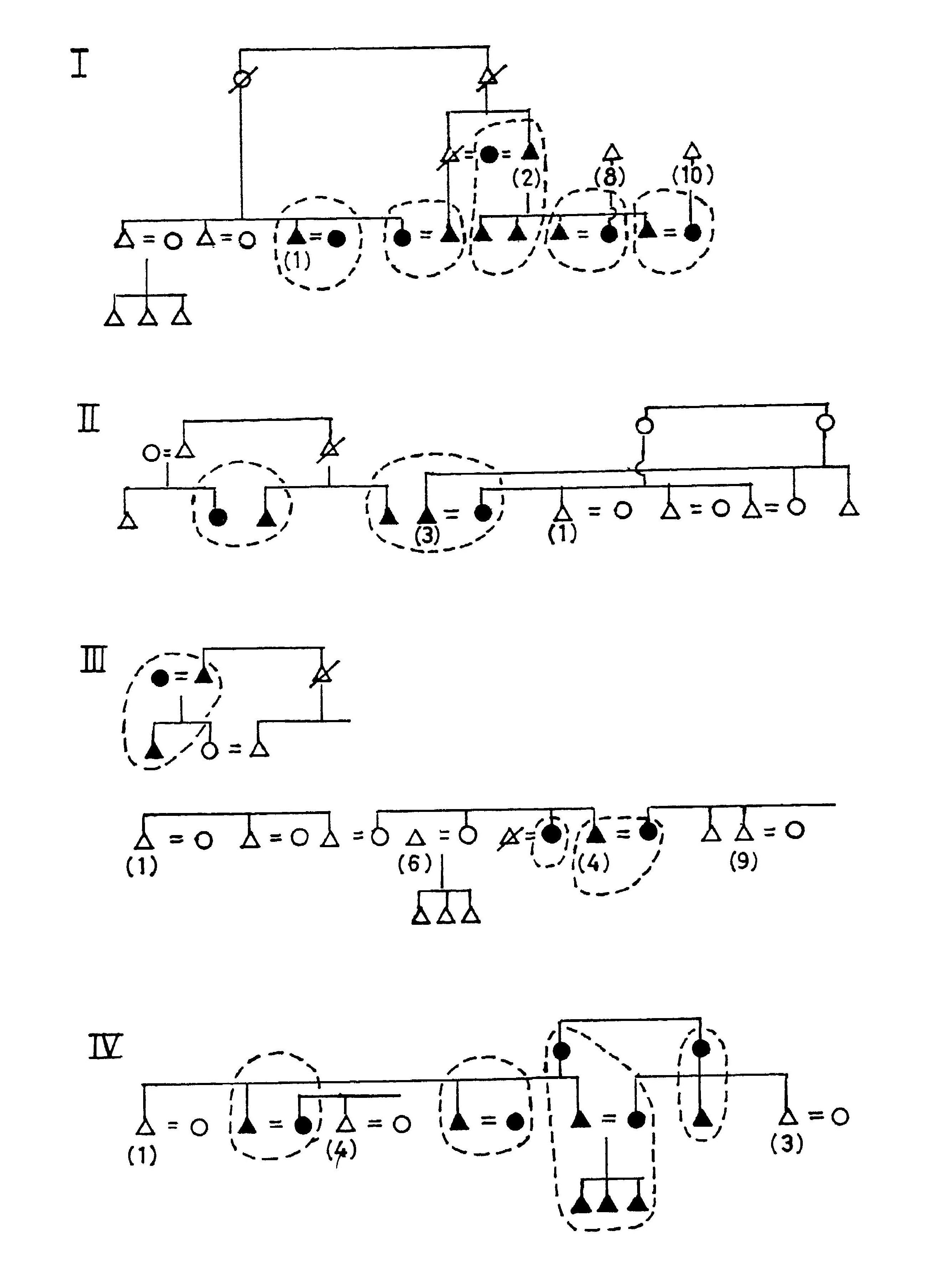

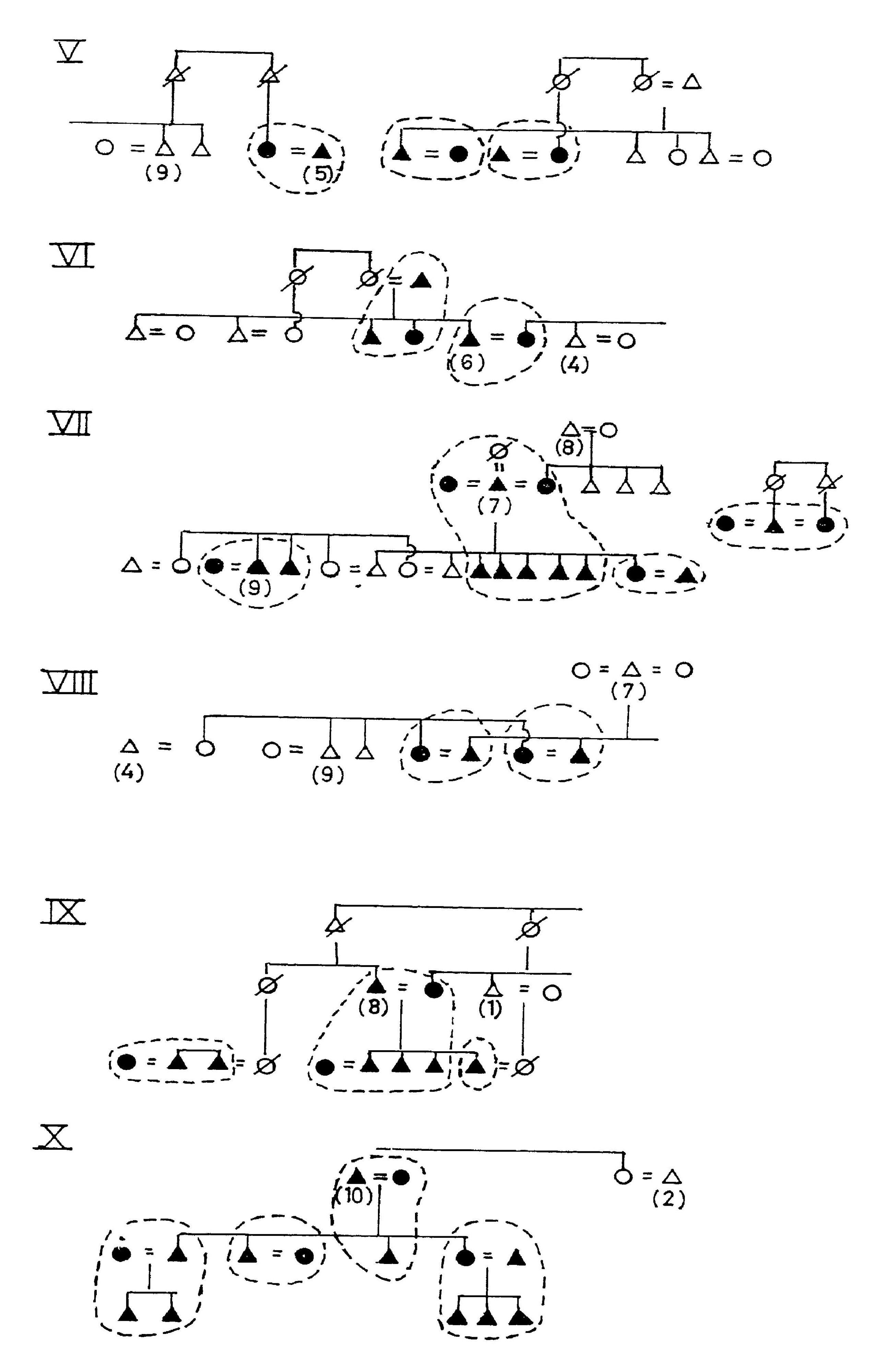

| FIG. 2 | Kinship composition of five camps |

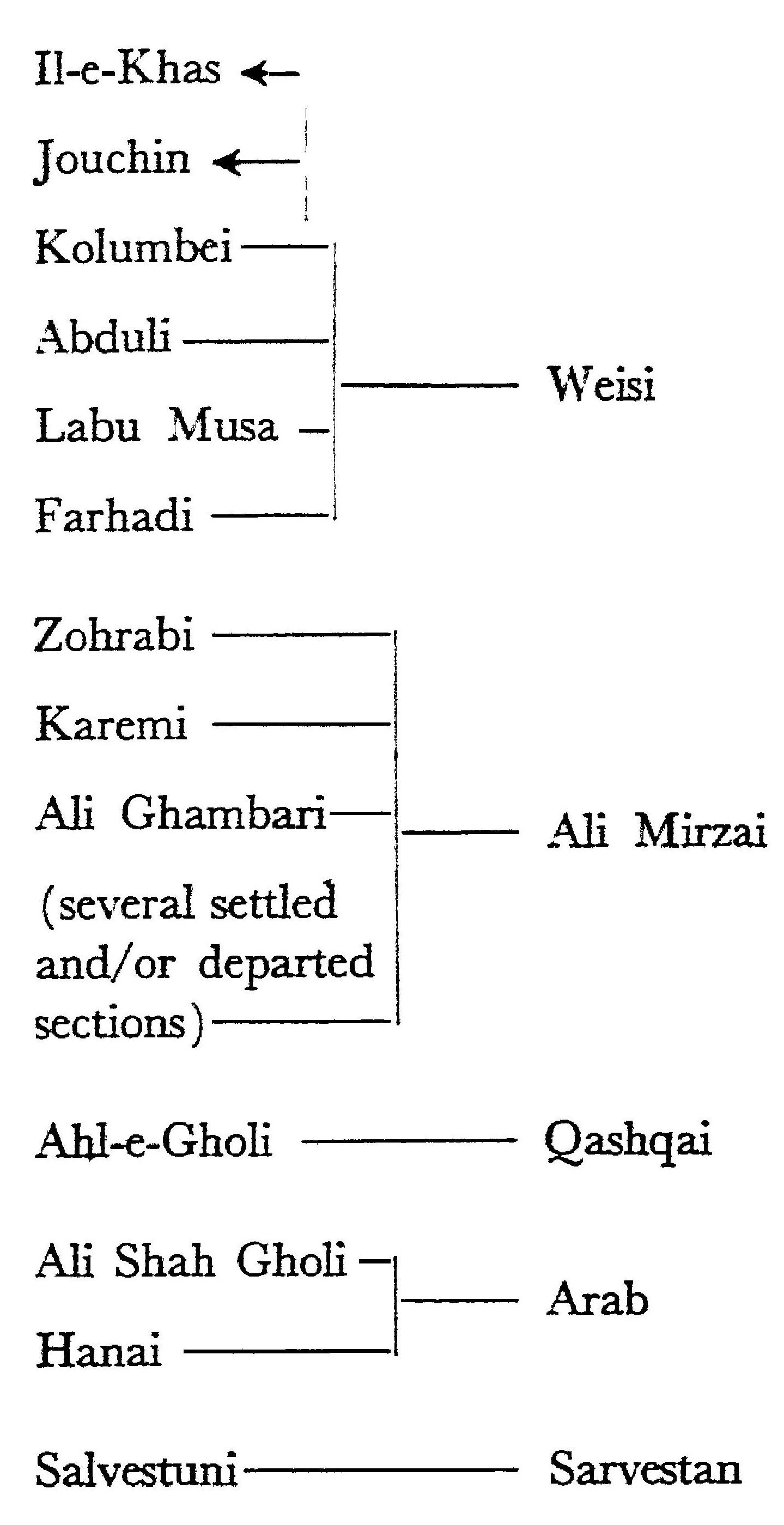

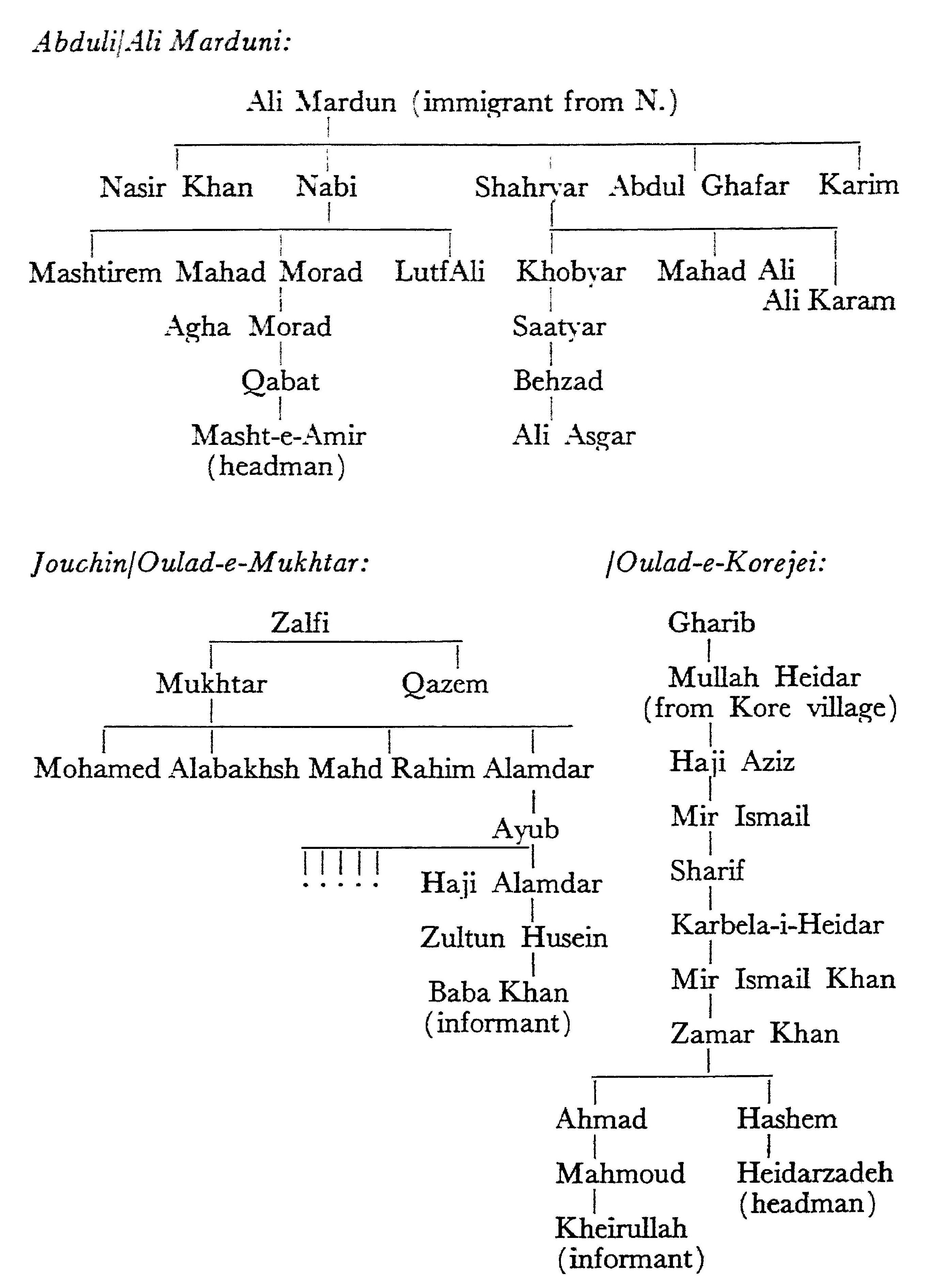

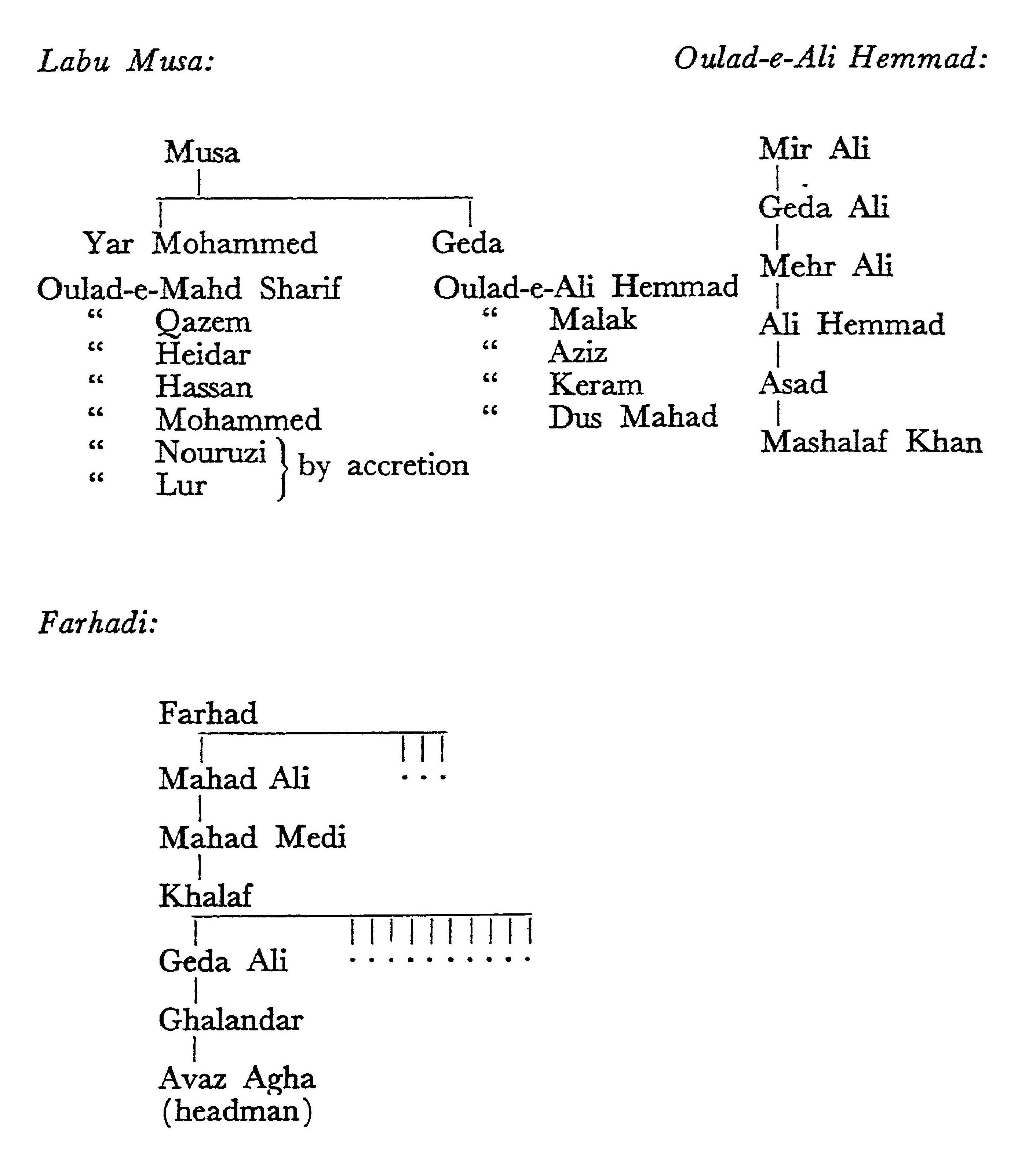

| FIG. 3 | Genetic relations of Basseri sections |

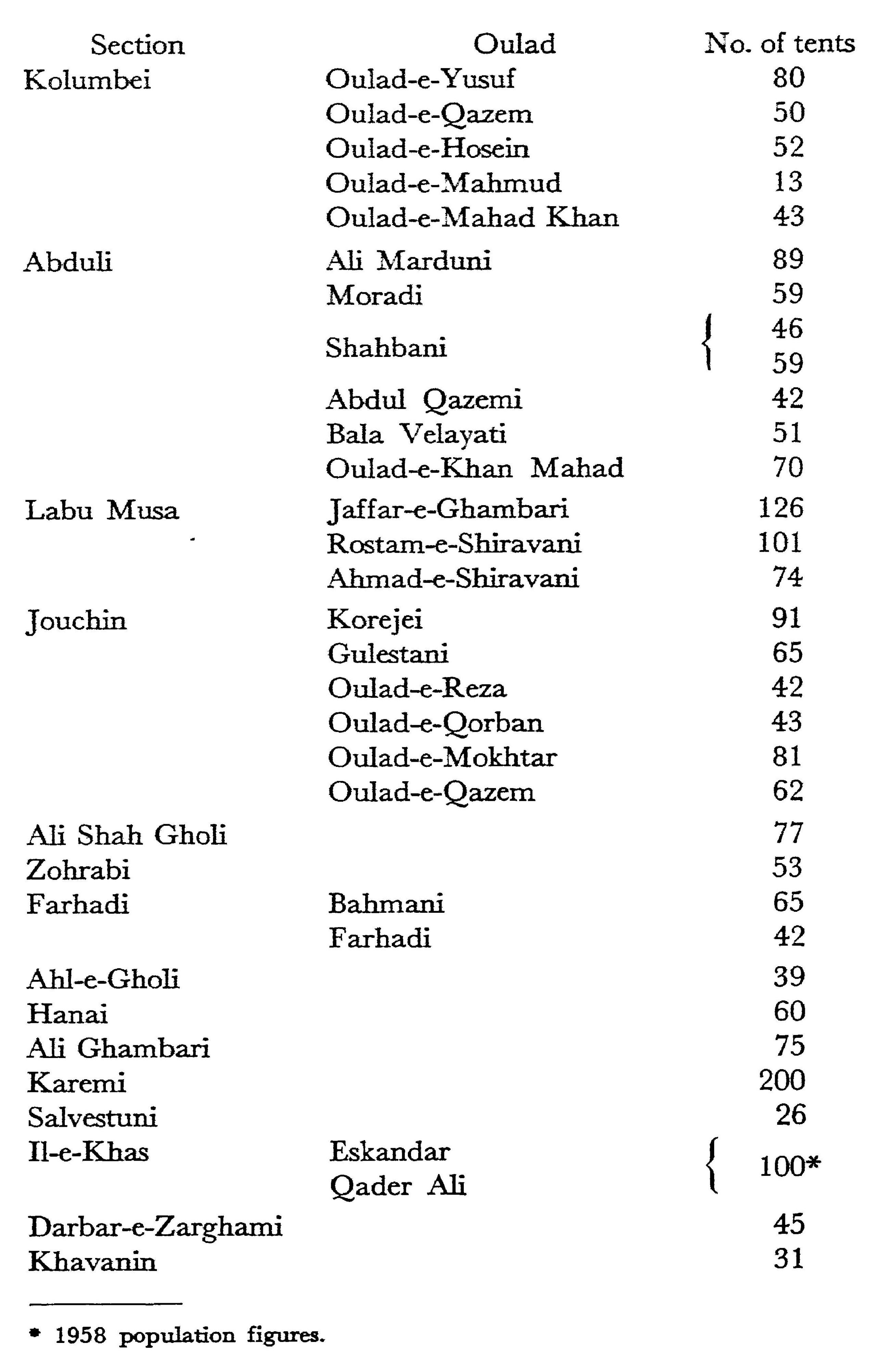

| FIG. 4 | Pedigrees and genealogies of some Basseri sections and oulads |

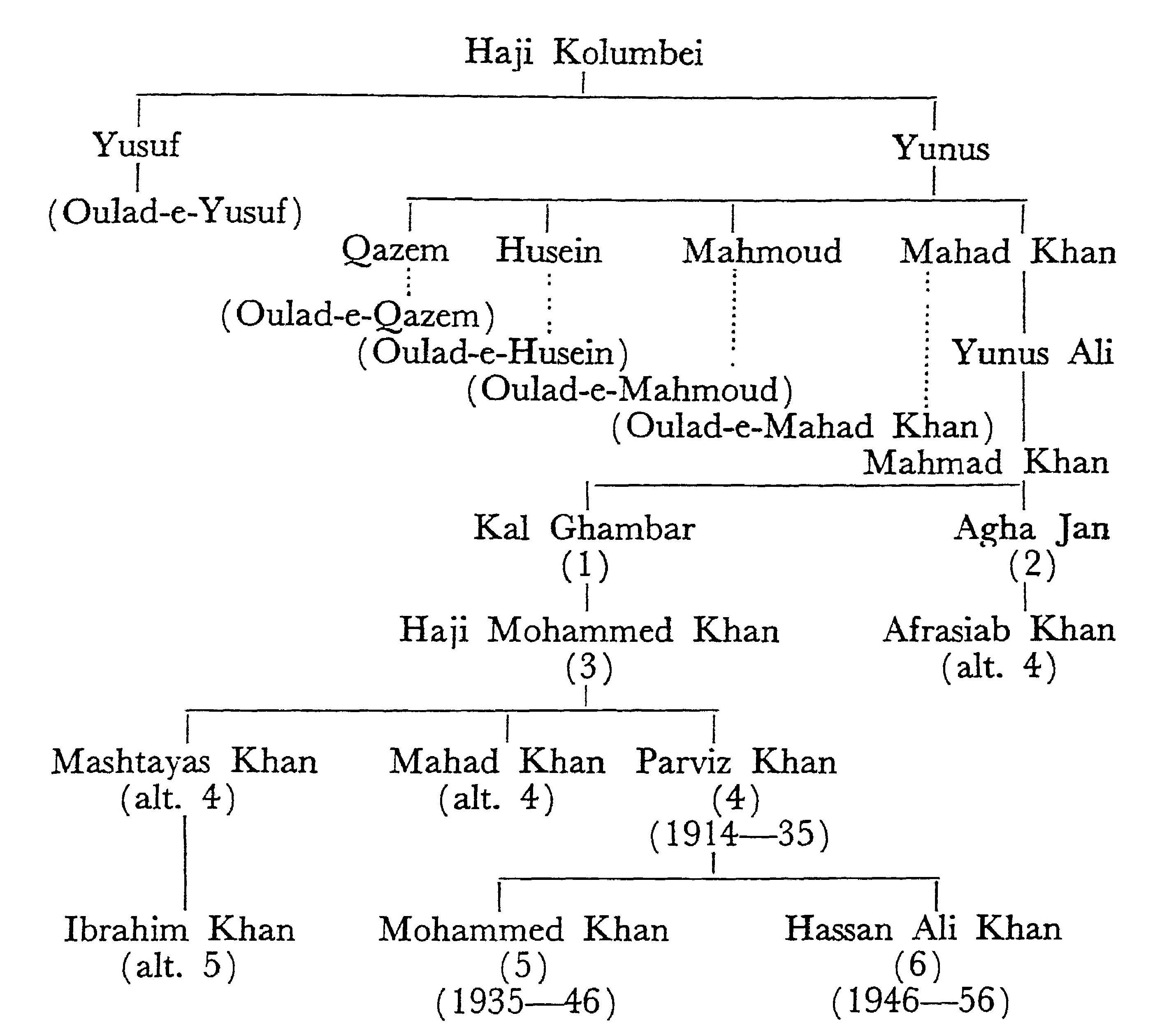

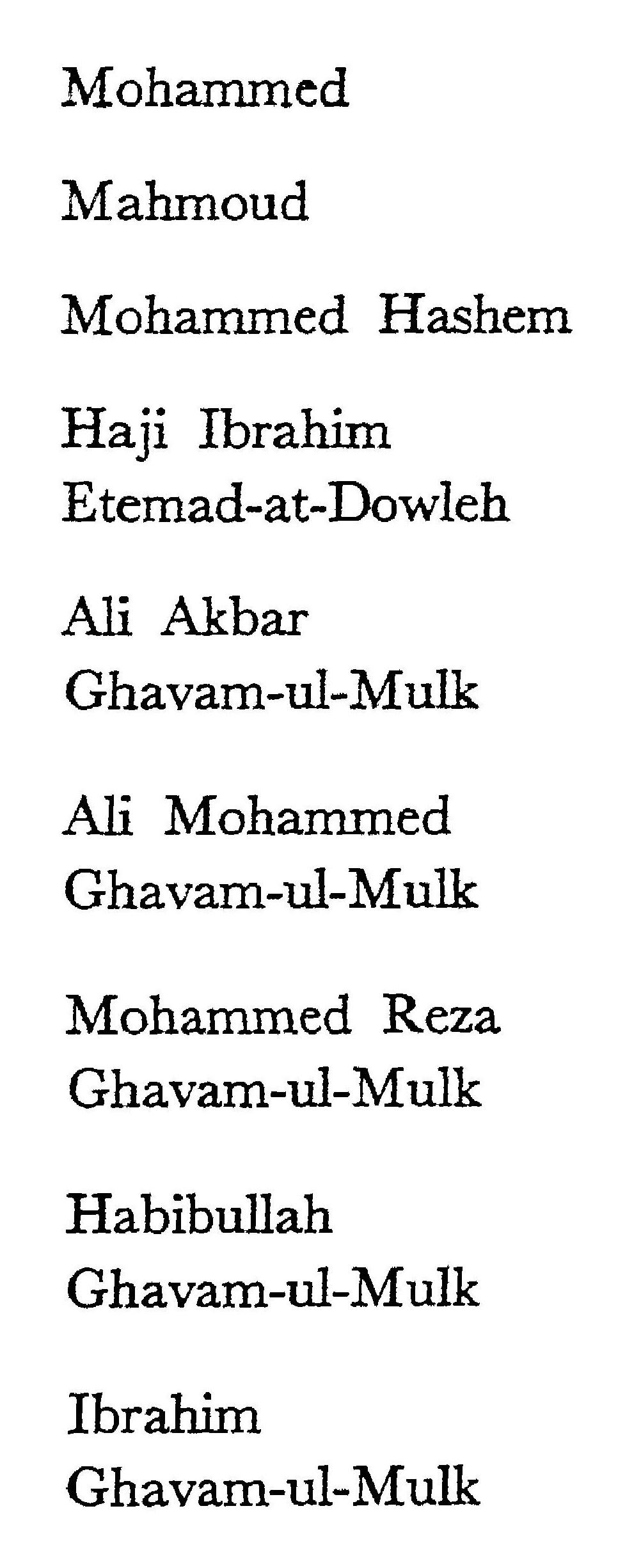

| FIG. 5 | Genealogy of the Basseri chiefs |

| FIG. 6 | The heads of the Ghavam family from its founding to the present |

| FIG. 7 | Routes of sedentarization |

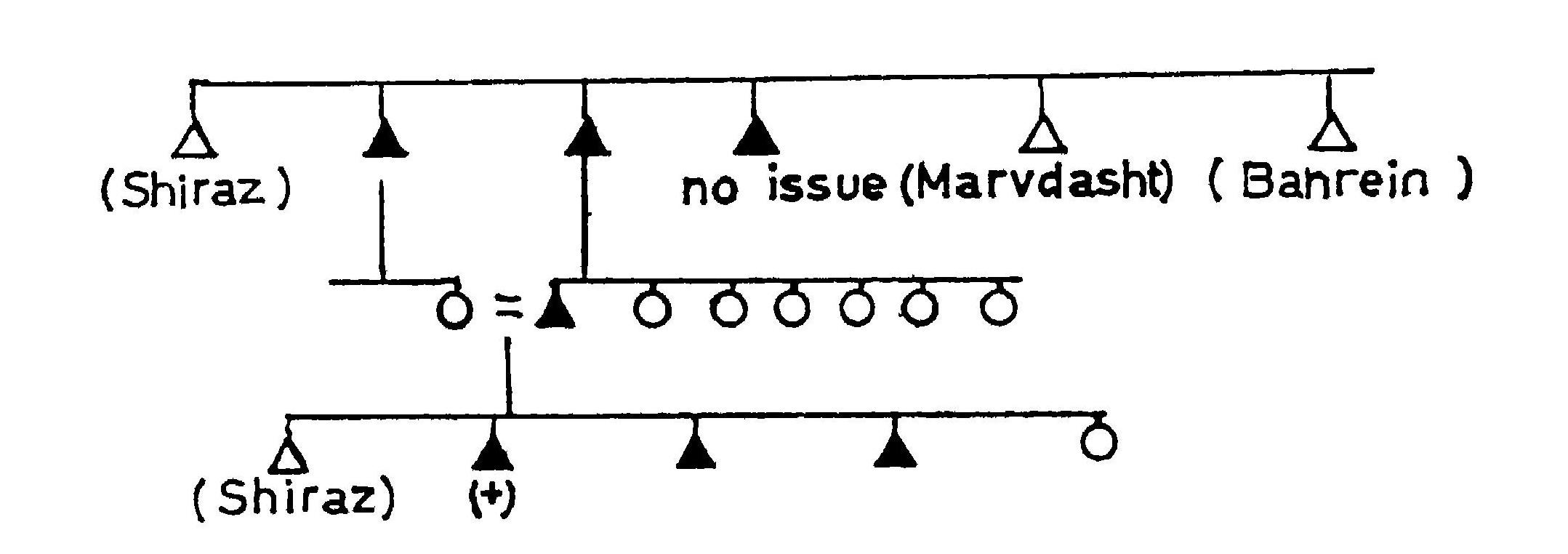

| FIG. 8 | Cases of sedentarization in one family history |

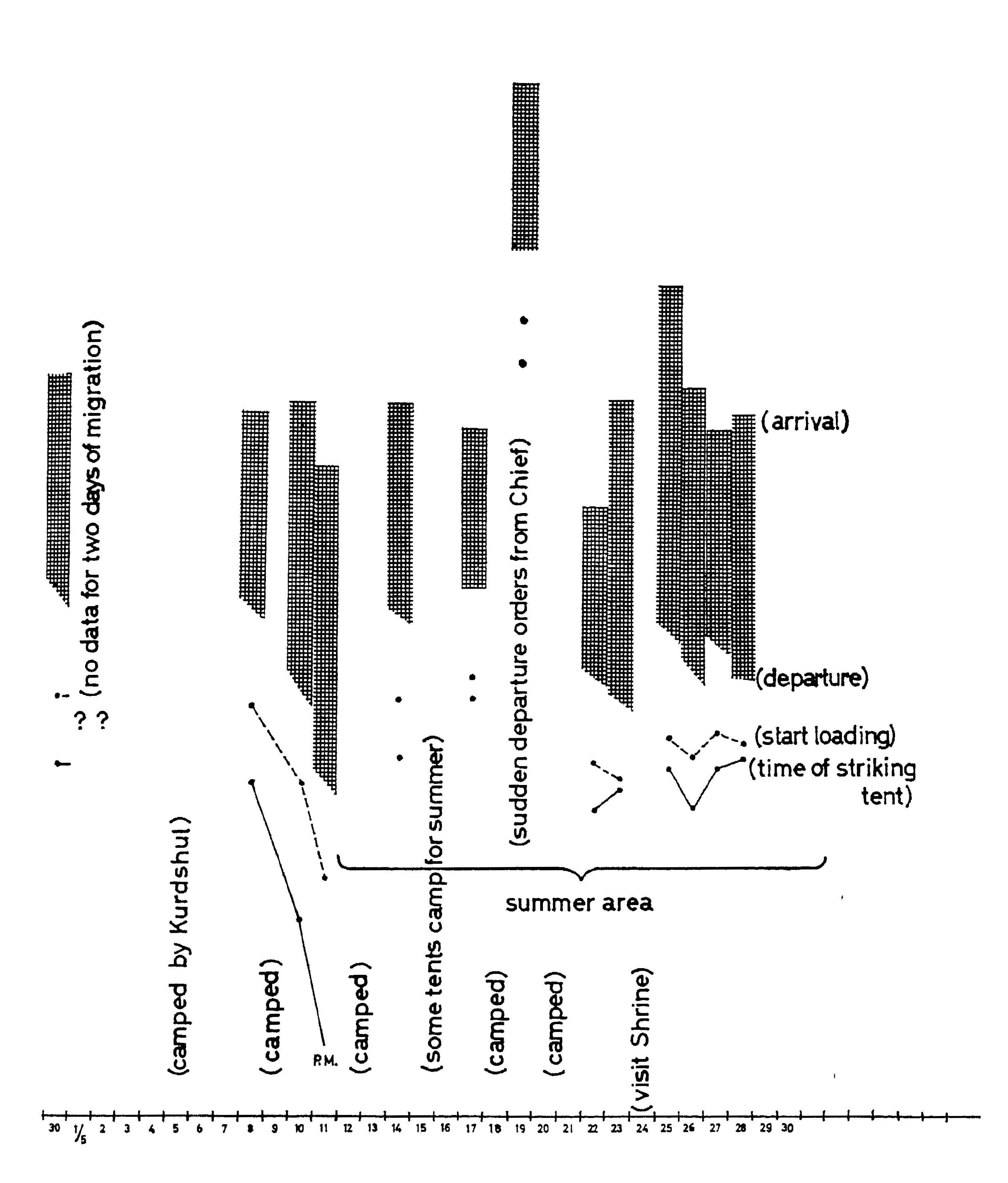

| FIG. 9 | Time sequences during the Darbar camp’s spring migration in 1958 |

| FIG. 10 | Herding units of the Darbar camp |

Foreword

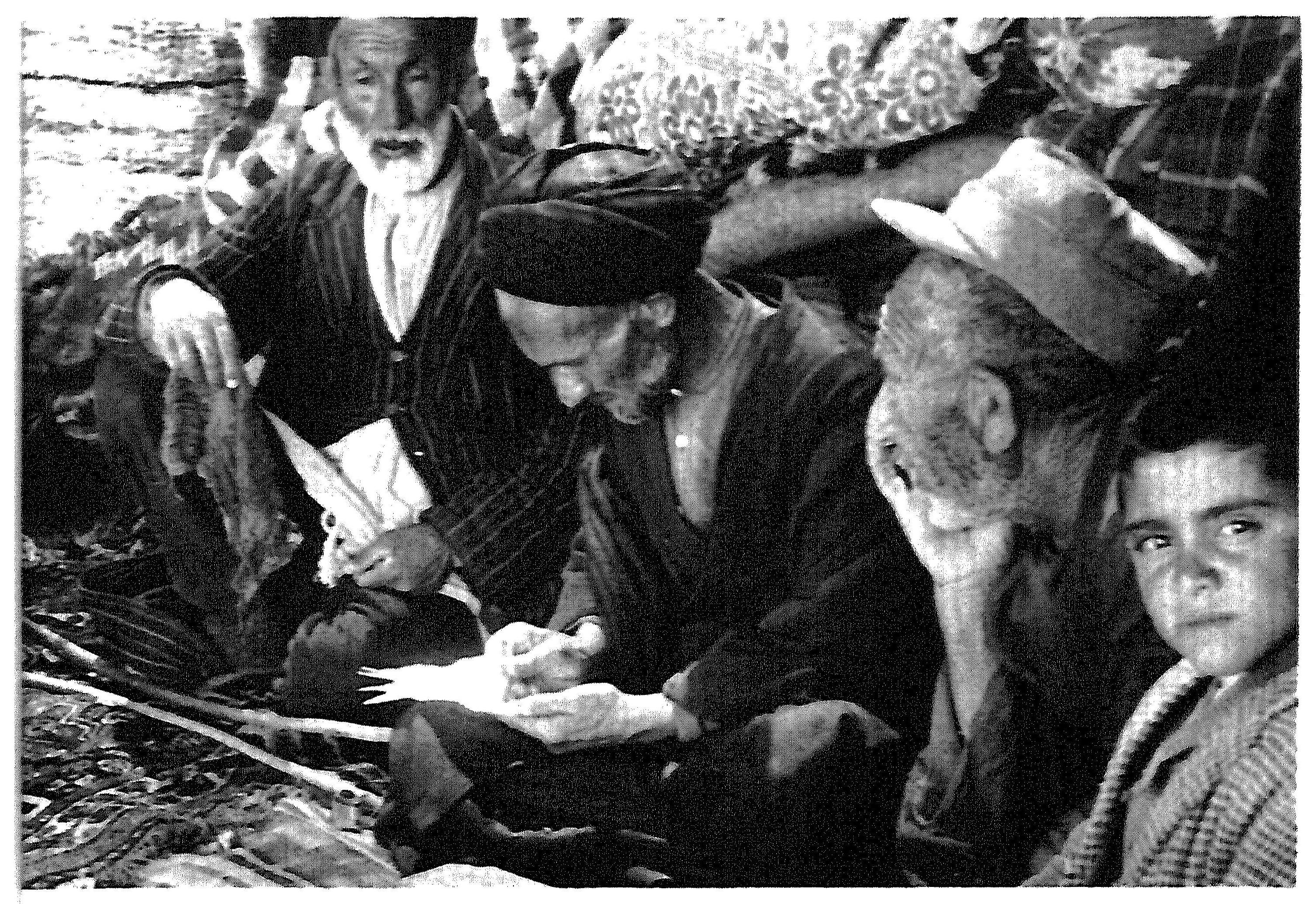

The following study is based on material collected in the field in Iran in the period December 1957 to July 1958 while I was engaged in research on nomads and the problems of sedentarization under the Arid Zone Major Project of UNESCO. Through the courtesy of H. E. Mr. Ala, the Court Minister, special permission was obtained from the Iranian Chief of Staff to enable me to spend the period 1/3 to 1/6 1958 among the Basseri nomads. Before and after that period, briefer visits were made to sedentary communities and other tribes in the province of Fars.

My thanks are first and foremost due to Mr. Hassan Ali Zarghami, the former chief of the Basseri, who gave me his full support in my studies and who made all possible arrangements for my comfort; to Ghulam Islami and his family, who received me into their tent and made me feel welcome as a member of their household throughout the duration of my stay; and to Ali Dad Zare, who served me with competence and patience as field assistant. I also recognize a debt to many other persons who have facilitated this work: to members of the Basseri tribe and particularly of the Darbar camp, and to friends and officials in Iran and elsewhere. In particular I want to mention Professor Morgenstierne of the University of Oslo, with whom I read Persian.

There are few previous studies in the literature on any of the nomadic groups in the Middle East, and none on the Khamseh. I have therefore seen it as an important duty in the following study to put down as much as possible of what I was able to observe of the society and culture of the Basseri. But this end is not best served by a mere compilation of a body of such observations — rather, I have tried through an analysis to “understand” or interrelate as many of these facts as possible.

The following pages present this analysis in terms of a general ecologic viewpoint. As the work grew, so did my realization of the extent to which most of the data are interconnected in terms of the possibilities and restrictions implied in a pastoral adaptation in the South Persian environment. Most of the following chapters describe different aspects of this adaptation. Starting with the elementary units of tents, or households, a description is given of the progressively larger units of herding groups, camps, the whole tribe and its major divisions, and the unifying political structure of the tribe and the confederacy. Throughout this description I try to reduce the different organizational forms to the basic processes by which they are maintained, and adapted to their environment. The subsequent chapters analyse more specifically some of these processes as they serve to maintain the tribe as an organized and persisting unit in relation to the outside, mainly within the systems of political relations, economic transactions, and demographics. The final chapter draws together the results of this analysis, and tries to apply the resulting model of Basseri; organization to a comparative discussion of some features of nomadic organization in the South Persian area.

There are a number of reasons why some kind of ecologic orientation is attractive in the analysis of the Basseri data. Some of these may be subjective and reflect the personal needs of the investigator, rather than the analytic requirements of the material. Perhaps this framework of analysis is particularly attractive because some features of nomadic life are so striking to any member of a sedentary society. The drama of herding and migration; the idleness of a pastoral existence, where the herds satisfy the basic needs of man, and most of one’s labour is expended on travelling and maintaining a minimum of personal comfort, and hardly any of it is productive in any obvious sense; the freedom, or necessity, of movement through a vast, barren and beautiful landscape — all these things assume a growing aesthetic and moral importance as one participates in nomadic life, and seem to call for an explanation in terms of the specific circumstances which have brought them forth. Perhaps also the poverty of ceremonial, and the eclectic modernism of the attitude of the Basseri, encourage an approach which relates cultural forms to natural circumstances, rather than to arbitrary premises. At all events, a great number of features of Basseri life and organization make sense and hang together as adaptations to a pastoral existence, and in terms of their implications for other aspects of the economic, social, and political life of the pastoral nomad population of Fars.

Oslo, October 1959.

F. B.

Chapter I: History, Ecology and Economy

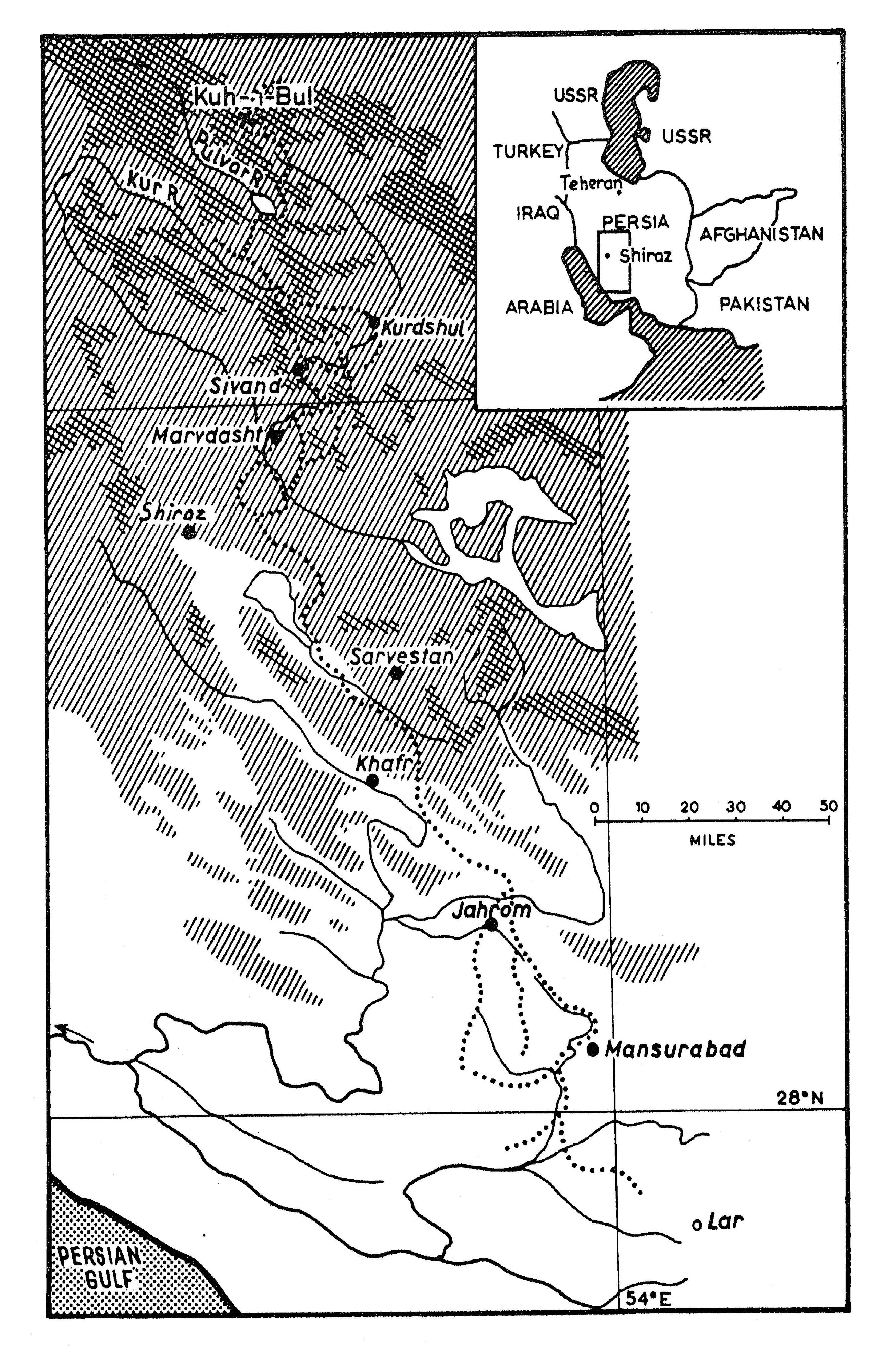

The Basseri are a tribe of tent-dwelling pastoral nomads who migrate in the arid steppes and mountains south, east and north of Shiraz in Fars province, South Persia. The area which they customarily inhabit is a strip of land, approximately 300 miles long and 20–50 miles wide, running in a fairly straight north-south line from the slopes of the mountain of Kuh-i-Bul to the coastal hills west of Lar. In this strip the tribe travels fairly compactly and according to a set schedule, so the main body of the population is at no time dispersed over more than a fraction of the route; perhaps something like a 50-mile stretch, or 2,000 square miles.

Fars Province is an area of great ethnic complexity and admixture, and tribal units are best defined by political, rather than ethnic or geographical criteria. In these terms the Basseri are a clearly delimited group, recognizing the authority of one supreme chief, and treated as a unit for administrative purposes by the Iranian authorities. The Basseri have furthermore in recent history been associated with some other tribes in the larger Khamseh confederacy; but this grouping has today lost most of its political and social meaning.

The total population of the Basseri probably fluctuates between 2,000 and 3,000 tents, depending on the changing fortunes of their chiefs as political leaders, and on the circumstances of South Persian nomadism in general. Today it is estimated at nearly 3,000 tents, or roughly 16,000 inhabitants.

The Basseri tribe is Persian-speaking, using a dialect very close to the urban Persian of Shiraz town; and most tribesmen know only that language, while some are bilingual in Persian and Turkish and a few in Persian and Arabic. All these three language communities are represented among their neighbours. Adjoining them in most of their route is the smaller Kurdshuli tribe, speaking the Luri dialect of Persian and politically connected with the Qashqai confederacy. Politically dependent on the Basseri are the remnants of the Turkishspeaking Nafar tribe. The territories to the east are mostly occupied by various Arab tribes, some still Arabic-speaking and some Persian of the same dialect as the Basseri. Other adjoining areas to the east are dominated by the now largely sedentary Baharlu Turkish-speaking tribe. All these eastern tribes were associated with the Basseri in the Khamseh confederacy. The opposing Qashqai confederacy dominates the territories adjoining the Basseri on the west, represented by various branches of which the Shishbeluki are among the most important. These tribes are Turkish-speaking.

In addition to the Basseri population proper, various other groups are found that regard themselves as directly derived from the Basseri, while other groups claim a common or collateral ancestry. In most of the villages of the regions through which the Basseri migrate, and in many other villages and towns of the province, including Shiraz, is a considerable sedentary population of Basseri origin. Some of these are recent settlers — many from the time of Reza Shah’s enforced settlement in the 3 O’s and some even later — while others are third or fourth generation. In some of the villages of the north, notably in the Chahardonge area, the whole population regards itself as a settled section of the tribe, while in other places the settlers are dispersed as individuals or in small family groups.

Several other nomad groups also recognize a genetic connection with the Basseri. In the Isfahan area, mostly under the rule of the Dareshuri Turkish chiefs, are a number of Basseri who defected from the main body about 100 years ago and now winter in the Yazd- Isfahan plain and spend the summer near Semirun (Yazd-e-Khast). In north-west Fars a tribe generally known as the Bugard-Basseri migrates in a tract of land along the Qashqai-Boir Ahmed border. Finally, on the desert fringe east of Teheran, around Semnan, there is reported a considerable tribal population calling themselves Basseri, who are known and recognized as a collateral group by the Basseri of Fars.

The sparse historical traditions of the tribe are mainly connected with sectional history (pp. 52 ff.), or with the political and heroic exploits of recent chiefs (pp. 72 ff.). Of the tribe as a whole little is recounted., beyond the assertion that the Basseri have always occupied their present lands and were created from its dust — assertions contradicted by the particular traditions of the various sections.

Early Western travellers prove poor sources on the nomad tribes of Persia; but at least tribal names and sections are frequently given. The Basseri are variously described as Arab and Persian, as largely settled and completely nomadic. An early reference to them is found in Morier (1837: 232), based on materials collected in 1814–15. One would guess from the paucity of information on the tribe that it was relatively small and unimportant; overlordship over the tribe had, according to Persian historical compilations, been entrusted to the Arab chiefs in Safavid times (Lambton 1953: 159). According to the Ghavams, leaders of the Khamseh, the confederacy was formed about 90–100 years ago by the FaFaFa of the present Ghavam. In the beginning the Turk tribes of Baharlu and Aynarlu were predominant among the Khamseh, and the Basseri grew in importance only later. Most Basseri agree that the tribe has experienced a considerable growth in numbers and power during the last three generations.

During the enforced settlement in the reign of Reza Shah only a small fraction of the Basseri were able to continue their nomadic habit, and most were sedentary for some years, suffering a considerable loss of flocks and people. On Reza Shah’s abdication in 1941 migratory life was resumed by most of the tribesmen. The sections and camp-groups of the tribe were re-formed and the Basseri experienced a considerable period of revival. At present, however, the nomads are under external pressure to become sedentary, and the nomad population is doubtless on the decline.

The habitat of the Basseri tribe lies in the hot and arid zone around latitude 30° N bordering on the Persian Gulf. It spans a considerable ecologic range from south to north, ranging from low-lying salty and torrid deserts around Lar at elevations of 2,000 to 3,000 ft. to high mountains in the north, culminating in the Kuh-i-Bul at 13,000 ft. Precipitation is uniformly low, around 10”, but falls mainly in the winter and then as snow in the higher regions, so a considerable amount is conserved for the shorter growing season in that area. This permits considerable vegetation and occasional stands of forest to develop in the mountains. In the southern lowlands, on the other hand, very rapid run-off and a complete summer drought limits vegetation, apart from the hardiest desert scrubs, to a temporary grass cover in the rainy season of winter and early spring.

Agriculture offers the main subsistence of the population in the area, though not of the Basseri. It is under these conditions almost completely dependent on artificial irrigation. Water is drawn by channels from natural rivers and streams in the area, or, by the help of various contraptions, raised by animal traction from wells, particularly by oxen and horses. Finally, complex nets of qanats are constructed — series of wells connected by subterranean aqueducts, whereby the groundwater of higher areas is brought out to the surface in lower parts of the valleys.

The cultivated areas, and settled populations, are found mostly in the middle zone around the elevation of Shiraz (5,000 ft. altitude), and also, somewhat more sparsely, as more or less artificial oases in the south. Settlement in the highest zones of the north is most recent, and still very sparse.

The pastoral economy of the Basseri depends on the utilization of extensive pastures. These pastures are markedly seasonal in their occurrence. In the strip of land utilized by the Basseri different areas succeed each other in providing the necessary grazing for the flocks. While snow covers the mountains in the north, extensive though rather poor pastures are available throughout the winter in the south. In spring the pastures are plentiful and good in the areas of low and middle altitude; but they progressively dry up, starting in early March in the far south. Usable pastures are found in the summer in areas above c. 6,000 ft; though the grasses may dry during the latter part of the summer, the animals can subsist on the withered straw, supplemented by various kinds of brush and thistles. The autumn season is generally poor throughout, but then the harvested fields with their stubble become available for pasturage. In fact most landowners encourage the nomads to graze their flocks on harvested and fallow fields, since the value of the natural manure is recognized.

The organization of the Basseri migrations, and the wider implications of this pattern, have been discussed elsewhere (Barth 1960). An understanding of the South Persian migration and land use pattern is facilitated by the native concept of the il-rah, the “tribal road”. Each of the major tribes of Fars has its traditional route which it travels in its seasonal migrations. It also has its traditional schedule of departures and duration of occupations of the different localities; and the combined route and schedule which describes the locations of the tribe at different times in the yearly cycle constitutes the il-rah of that tribe. Such an il-rah is regarded by the tribesmen as the property of their tribe, and their rights to pass on roads and over uncultivated lands, to draw water everywhere except from private wells, and to pasture their flocks outside the cultivated fields are recognized by the local population and the authorities. The route of an il-rah is determined by the available passes and routes of communication, and by the available pastures and water, while the schedule depends on the maturation of different pastures, and the movements of other tribes. It thus follows that the rights claimed to an U-rah do not imply exclusive rights to any locality throughout the year, and nothing prevents different tribes from utilizing the same localities at different times — a situation that is normal in the area, rather than exceptional.

The Basseri il-rah extends in the south to the area of winter dispersal south of Jahrom and west of Lar. During the rainy season camps are pitched on the mountain flanks or on the ridges themselves to avoid excessive mud and occasional flooding. In early spring the tribes move down into the mainly uncultivated valleys of that region, and progressively congregate on the Benarou-Mansurabad plain. The main migration commences at the spring equinox, the time of the Persian New Year. The route passes close by the market town of Jahrom, and northward over a series of ridges and passes separating a succession of large flat valleys. The main bottleneck, both for reasons of natural communication routes and because of the extensive areas of cultivation, is the Marvdasht plain, where the ruins of Persepolis are located. Here the Basseri pass in the end of April and beginning of May, crossing the Kur river by the Pul-e-Khan or Band-Amir bridges, or by ferries. In the same period, various Arab and Qashqai tribes are also funnelled through this area.

Continuing northward, the Basseri separate and follow a number of alternative routes, some sections lingering to utilize the spring pastures in the adjoining higher mountain ranges, others making a detour to the east to pass through some villages recently acquired by the Basseri chief. The migration then continues into the uppermost Kur valley, where some sections remain, while most of the tribe pushes on to the Kuh-i-Bul area, where they arrive in June.

While camp is moved on most days during this migration, the population becomes more stationary in the summer, camping for longer periods and moving only locally. The first camps commence the return journey in the end of August, to spend some weeks in the Marvdasht valley grazing their flocks on the stubble and earning cash by labour; most go in the course of September. As the pastures are usually poor the tribe travels rapidly with few or no stops, and reaches the south in the course of 40—50 days, by the same route as the spring journey. During winter, as in the summer, migrations are local and short and camp is broken only infrequently.

The Basseri keep a variety of domesticated animals. Of far the greatest economic importance are sheep and goats, the products of which provide the main subsistence. Other domesticated animals are the donkey for transport and riding (mainly by women and children), the horse for riding only (predominantly by men), the camel for heavy transport and wool, and the dog as watchdog in camp. Poultry are sometimes kept as a source of meat, never for eggs. Cattle are lacking, reportedly because of the length of the Basseri migrations and the rocky nature of the terrain in some of the Basseri areas.

There are several common strains of sheep in Fars, of different productivity and resistance. Of these the nomad strain tends to be larger and more productive. But its resistance to extremes of temperature, particularly to frost, is less than that of the sheep found in the mountain villages, and its tolerance to heat and parched fodder and drought is less than that of the strains found in the south. It has thus been the experience of nomads who become sedentary, and of occasional sedentary buyers of nomad livestock, that 70–80 % of the animals die if they are kept throughout the year in the northern or southern areas. The migratory cycle is thus necessary to maintain the health of the nomads’ herds, quite apart from their requirements for pastures.

Sheep and goats are generally herded together, with flocks of up to 300–400 to one shepherd unassisted by dogs. About one ram is required for every five ewes to ensure maximal fertility in the flock, whereas in the case of goats the capacity of a single male appears to be much greater. The natural rutting seasons are three, falling roughly in June, August/September, and October; and the ewes consequently throw their lambs in November, January/February, or March. Some sections of the tribe (e. g. the Il-e-Khas) who winter further north in the zone of middle altitude separate the rams and the ewes in the August/September rutting period to prevent early lambing.

Lambs and kids are usually herded separately from the adults, and those born during the long migrations are transported strapped on top of the nomads’ belongings on donkeys and camels for the first couple of weeks. A simple device to prevent suckling, a small stick through the lamb’s mouth which presses down the tongue and is held in place by strings leading back behind the head, is used to protect the milk of the ewes when lambs and kids travel with the main herd. Early weaning is achieved by placing the lamb temporarily in a different flock from that of its mother.

The animals have a high rate of fertility, with moderately frequent twinning and occasionally two births a year. However, the herds are also subject to irregular losses by disaster and pest; mainly heavy frosts at the time of lambing, and foot-and-mouth disease and other contagious animal diseases. In bad years, the herds may. suffer average losses of as much as 50 %. Contrary to general reports, the main migrations are not in themselves the cause of particular losses of livestock, by accident or otherwise.

The products derived from sheep -and goats are milk, meat, wool and hides, while of the camel only the wool is used. These products are variously obtained and processed, and are consumed directly, stored and consumed, or traded.

Milk and its products are most important. Sheep’s and goats’ milk are mixed during milking. Milk is never consumed fresh, but immediately heated slightly above body temperature, and started off by a spoonful of sour milk or the stomach extract of a lamb; it then rapidly turns into sour milk or junket respectively. Cheese is made from the junket; it is frequently aged but may also be consumed fresh. Cheese production is rarely attempted in periods of daily migrations, and the best cheese is supposed to be made in the relatively stationary period of summer residence.

Sour milk (mast) is a staple food, and particularly in the period of maximal production in the spring it is also processed for storage. By simple pressing in a gauze-like bag the curds may be separated from the sour whey; these curds are then rolled into walnut-sized balls and dried in the sun (kashk) for storage till winter. The whey is usually discarded or fed to the dogs; the Il-e-Khas are unusual, and frequently ridiculed, for saving it and producing by evaporation a solid residue called qara gkorut, analogous to Scandinavian “goat cheese”.

Sour milk may also be churned, or actually rocked, in a goat skin (mashk) suspended from a tripod, to produce butter and buttermilk fdogh). The latter is drunk directly, the former is eaten fresh, or clarified and stored for later consumption or for sale.

Most male and many female lambs and kids are slaughtered for meat; this is eaten fresh and never smoked, salted or dried. The hides of slaughtered animals are valuable; lambskins bring a fair price at market, and the hides of adults are plucked and turned inside out, and used as storage bags for water, sour milk and buttermilk. The skins of kids, being without commercial value and rather small and weak, are utilized as containers for butter etc.

Wool is the third animal product of importance. Lamb’s wool is made into felt, and sheep’s wool and camel-hair are sold, or spun and used in weaving and rope-making. Goat-hair is spun and woven.

In the further processing of some of these raw products, certain skills and crafts are required. Though the nomads depend to a remarkable extent on the work of craftsmen in the towns, and on industrial products, they are also dependent on their own devices in the production of some essential forms of equipment.

Most important among these crafts are spinning and weaving. All locally used wool and hair is spun by hand on spindlewhorls of their own or Gypsy (cf. pp. 91–93) production — an activity which consumes a great amount of the leisure time of women. All saddlebags, packbags and sacks used in packing the belongings of the nomads are woven by the women from this thread, as are the rugs used for sleeping. Carpets are also tied, as are the outer surfaces of the finest pack- and saddle-bags. Furthermore, the characteristic black tents consist of square tentcloths of woven goat-hair — this cloth has remarkable water-repellent and heat-retaining properties when moist, while when it is dry, i. e. in the summer season, it insulates against radiation heat and permits free circulation of air. All weaving and carpet-tying is done on a horizontal loom, the simplest with merely a movable pole to change the sheds. None of these often very attractive articles are produced by the Basseri for sale.

Otherwise, simple utilitarian objects of wood such as tent poles and pegs, wooden hooks and loops bent over heat, and camels’ pack saddles are produced by the nomads themselves. Ropes for the tents, and for securing pack loads and hobbling animals are twined with 3–8 strands. Some of the broader bands for securing loads are woven. Finally, various repairs on leather articles, such as the horses’ bridles, are performed by the nomads, though there is no actual production of articles of tanned leather. Clothes for women are largely sewn by the women from bought materials, while male clothes are bought ready made.

Hunting and collecting are of little importance in the economy, though hunting of large game such as gazelle and mountain goat and sheep is the favourite sport of some of the men. In spring the women collect thistle-sprouts and certain other plants for salads or as vegetables, and at times are also able to locate colonies of truffles, which are boiled and eaten.

The normal diet of the Basseri includes a great bulk of agricultural produce, of which some tribesmen produce at least a part themselves. Cereal crops, particularly wheat, are planted on first arrival in the summer camp areas, and yield their produce before the time of departure; or locally resident villagers are paid to plant a crop before the nomads arrive, to be harvested by the latter. The agriculture which the nomads themselves perform is quite rough and highly eclectic; informants agreed that the practice is a recent trend of the last 10–15 years. Agricultural work in general is disliked and looked down upon, and most nomads hesitate to do any at all. The more fortunate, however, may own a bit of land somewhere along the migration route, most frequently in northern or southern areas, which they as landlords let out to villagers on tenancy contracts, and from which they may receive from 1/6 to 1/2 of the gross crop. Such absentee “landlords” do no agricultural work themselves, nor do they usually provide equipment or seed to their tenants.

A great number of the necessities of life are thus obtained by trade. Flour is the most important foodstuff, consumed as unleavened bread with every meal; and sugar, tea, dates, and fruits and vegetables are also important. In the case of most Basseri, such products are entirely or predominantly obtained by trade. Materials for ’clothes, finished clothes and shoes, all glass, china and metal articles including all cooking utensils, and saddles and thongs are also purchased, as well as narcotics and countless luxury goods from jewelry to travelling radios. In return, the products brought to market are almost exclusively clarified butter, wool, lambskins, and occasional live stock.

Chapter II: Domestic Units

The Basseri count their numbers and describe their camp groups and sections in terms of tents (sing.: khune = house). Each such tent is occupied by an independent household, typically consisting of an elementary family; and these households are the basic units of Basseri society. They are units of production and consumption; represented by their male head they hold rights over all movable property including flocks; and they can even on occasion act as independent units for political purposes.

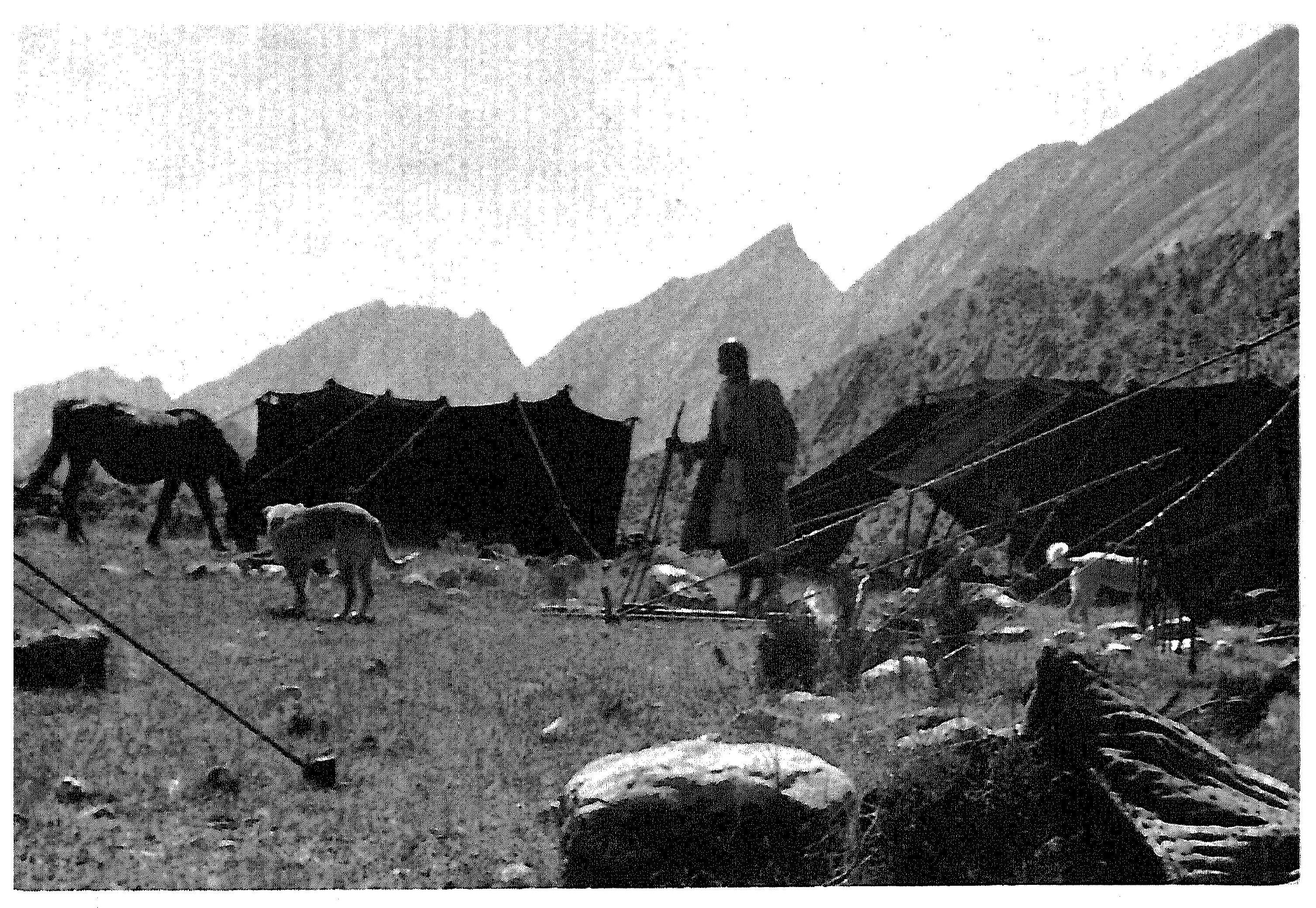

The external sign of the existence of such a social unit is the tent. This is a square structure of cloth woven from goat-hair, supported along the sides and in the corners by tent poles, and in the case of the larger tents also along the central line by a row of T-shaped poles. The size of the tent varies according to the means of the family which resides in it; but it is typically about 6 by 4 m, and 2 m high, supported by 5 poles along the long side and 3 poles along the short side, and composed of 5 separate cloths: 4 for walls and one for roof. These cloths are fastened together by wooden pins when the tent is pitched. At the proper position for each tentpole is a wooden loop, attached to the roof cloth; the ropes are stretched from these loops and the notched ends of the tentpoles support the ropes adjoining the loop, rather than the tent cloth itself. The lower part of the wall is formed by reed mats which are loosely leaned against the tent cloth and poles.

When travelling, the Basseri frequently pitch a smaller tent with fewer poles, using the roof cloth also for one wall and thereby producing a roughly cubical structure. When the weather is mild, a short or even a long side of the tent is left open, frequently by laying the wall cloth on top of the slanting tentropes; when the weather is cold the living space is closed in snugly by four full walls, and the tent is entered by a corner flap. Very occasionally in the summer when the tribe passes through openly forested areas, the tent may be dispensed with for a night and the households camp in the open under separate trees.

The living space within the tent is commonly organized in a standard pattern. Water and milk skins are placed along one side on a bed of stones or twigs; the belongings of the family are piled in a high wall towards the back, closing off a narrow private section in the very back of the tent. A shallow pit for the fire is placed close to the entrance. Though these arrangements are fairly stereotyped, they are dictated by purely practical considerations and are without ritual meaning.

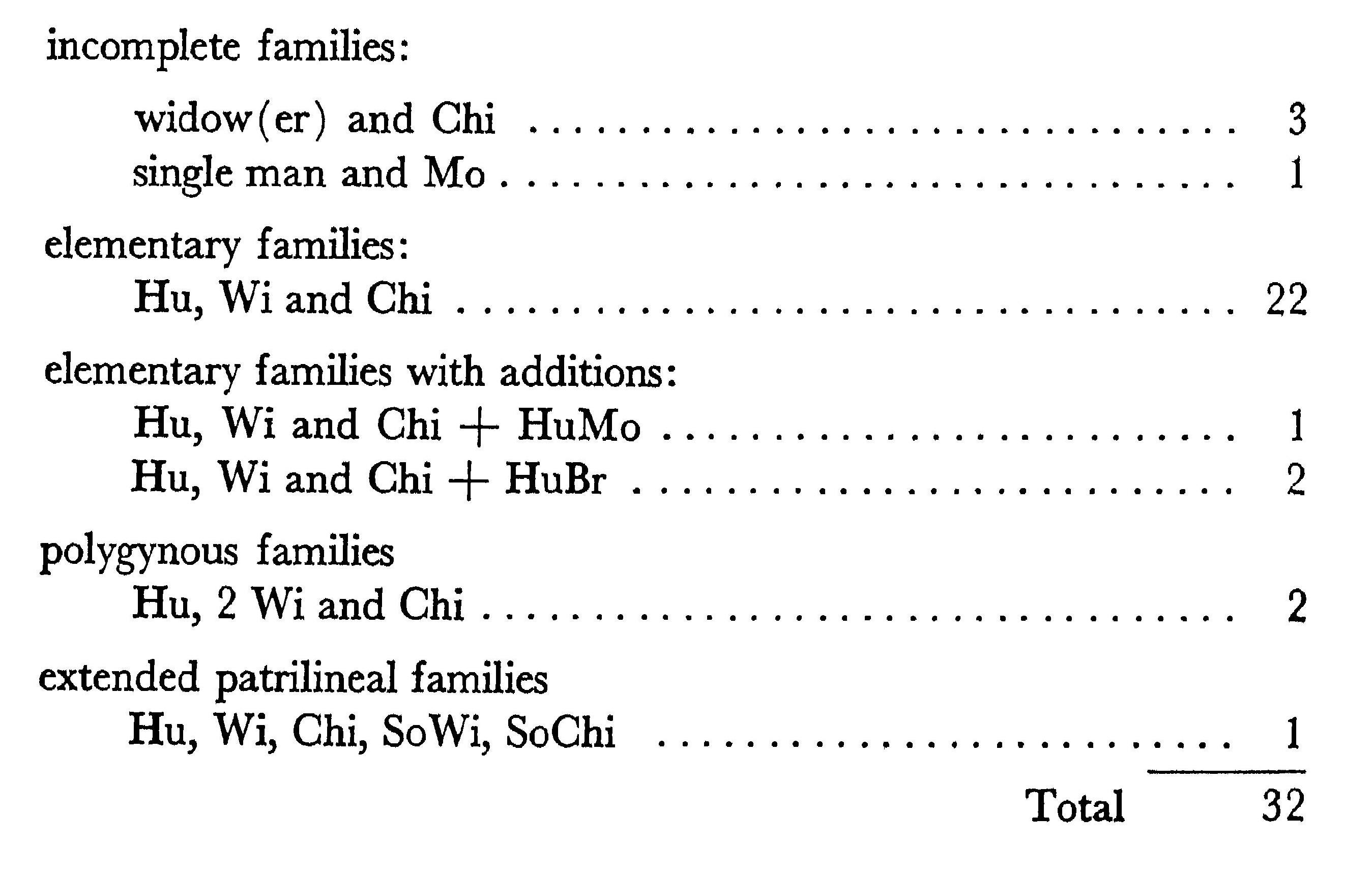

This structure is the home of a small family group. In one camp group of 32 tents the average number of persons per tent was 5.7. The household is built around one elementary family of a man, his wife and their children, with the occasional addition of unmarried or widowed close relatives who would otherwise be alone in their tent, or the wife and children of a married son who is the only son, or the most recent son to be married. The different types of household in one camp group were distributed as follows:

Composition of households:

incomplete families:

widow (er) and Chi 3

single man and Mo 1

elementary families:

Hu, Wi and Chi 22

elementary families with additions:

Hu, Wi and Chi + HuMo 1

Hu, Wi and Chi + HuBr 2

polygynous families

Hu, 2 Wi and Chi 2

extended patrilineal families

Hu, Wi, Chi, SoWi, SoChi 1

Total 32

The household occupying a tent is a commensal and propertyowning group. Though title to animals and some other valuable items of movable property may be vested in individual members of the household, the right to dispose of such is controlled by the head of the household, and the products of the animals owned by different members are not differentiated but used in the joint economy of the household.

In addition to the tent, the household, in order to exist, needs to dispose of all the equipment necessary to maintain the nomadic style of life — rugs and blankets for sleeping, pails and skins for milk, pots for cooking, and packbags to contain all the equipment during migrations, etc. Even between close relatives the lending and borrowing of such equipment is minimal.

The household depends for its subsistence on the animals owned by its members. These must as a minimum include sheep and goats as producers, donkeys to transport the belongings on the migrations, and a dog to guard the tent. All men also aspire to own a riding stallion, though less than half the household heads appear ever to achieve this goal; and wealthier persons with many belongings also need a few camels for transport.

Among the Basseri today each household has about 6–12 donkeys and on an average somewhat less than 100 adult sheep and goats. Every adult man has his distinctive sheep-mark, which by a combination of a brand on the sheep’s face and notching or cutting of one ear or both endeavours to be unique. Brothers frequently maintain their father’s brand when dividing the flock, but modify the earmarks. Yet there is no great emphasis on lineal continuity of brands, and men sometimes arbitrarily decide to change their brand. Though the herds may be large, adults have a remarkable ability to recognize individual animals; and the sheep-marks are used more as proof of the identity of lost sheep vis-a-vis outsiders than to distinguish the animals of different owners who camp together.

There is normally no loaning or harbouring of animals except for weaning purposes; each household keeps its flock concentrated. Occasionally, however, wealthy men may farm out a part of their flock to propertyless shepherds on a variety of contracts (cf. Lambton 1953: 351 ff.). These are, among the Basseri:

dandune contract: the shepherd pays 10–15 Tomans (1 Toman = roughly 1 shilling) per animal per year, keeps all products, and at the expiration of the contract returns a flock of the same size and age composition as he originally received.

ter az contract: the shepherd pays approximately 2 kg clarified butter per animal for the three spring months, and keeps all other products. If one of the flock stops giving milk in less than 45 days, he may have it replaced; if an animal is lost through anything but the negligence of the shepherd, the owner carries the loss.

nimei or nisfei contract (for goats only): the shepherd pays 30 Tomans/year per goat and keeps all its products; after termination of the contract period, usually 3–5 years, he keeps one half of the herd as it stands, and returns the other half to the original owner.

Such contracts are most common in periods when the flocks of the Basseri are large.

Domestic organization. Within each tent there is a distribution of authority and considerable division of labour among the members of the household. But this follows a highly elastic pattern, and it is characteristic that few features of organization are socially imperative and common to all, while many features vary, and appear to reflect the composition of each household and the working capacities of its members.

All tents have a recognized head, who represents the household in all dealings with the formal officers of the tribe, and with villagers and other strangers. Where the household contains an elementary family, the head is universally the husband in that family, even when his widowed father or senior brother resides with the family. Where the tent is occupied by an incomplete family, the senior male is the head. Only where there are no adult male members of the household, or where they are temporarily absent, is a woman ever regarded as the head of a household; and in such cases she is usually represented for formal purposes by a relative.

However, with respect to decisions in the domestic and familial domain, men and women are more nearly equal, and the distribution of authority between spouses is a matter of individual adaptation. Thus decisions regarding the multitude of choices in the field of production and consumption (but not decisions about migration routes and camp sites), all matters of kinship and marriage and the training of children, and decisions that will greatly affect the family, such as whether to change one’s group membership, or become sedentary, these are all decisions that are shared by the spouses and to some extent by the other adult members of the household, and in which the wiser or more assertive person dominates, regardless of sex. The internal authority pattern of the Basseri is thus very similar to that of the urban Western family.

Labour is divided among household members by sex and age, but few tasks are rigidly allotted to only one sex or one age group. The various labour tasks may be grouped in three categories: domestic work, the daily cycle of migration, and tending and herding of animals.

Domestic tasks are mainly done by the women and girls — they prepare food, wash and mend clothes, spin and weave, while the men and boys provide wood and water. But this latter is also frequently done by girls and sometimes by poor women, while men frequently make tea, or roast meat, or wash their own clothes. Spinning and weaving are never done by men, and male villagers are often ridiculed by the nomads for pursuing these activities. Most repairs of equipment and tents, twining of ropes, etc. are done by men.

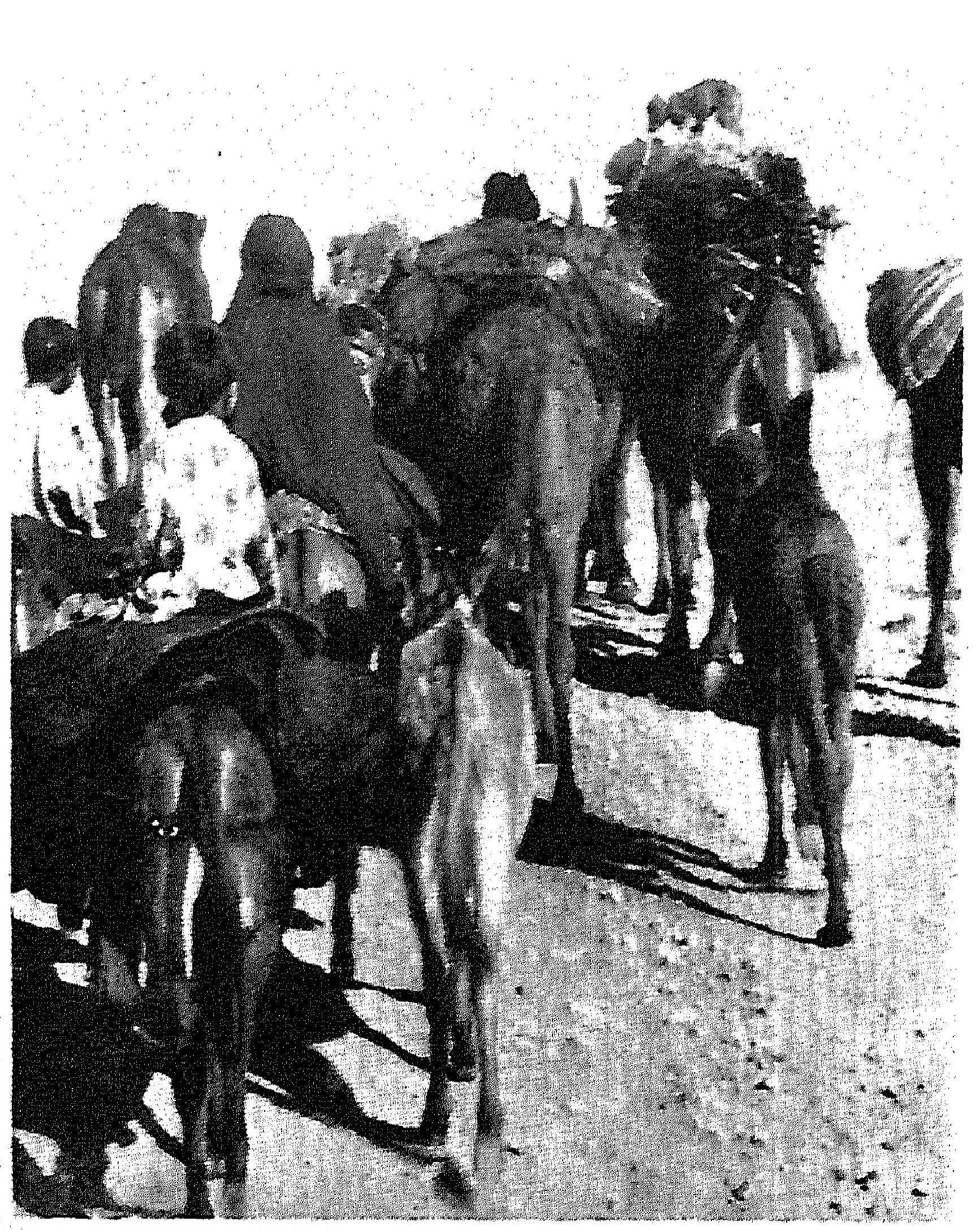

About 120 days out of the year, the average Basseri camp is struck and repitched at a new location; and these frequent migrations consume much time and labour and strongly affect the organization of the daily round. Activity starts well before daylight, when the sheep and goats, which have spent the night by the tent, depart in the care of a shepherd who is usually a boy or man, but may also be a girl. The tent is usually struck before sunrise, while the household members snatch odds and ends of left-over food and drink tea for breakfast. The donkeys, which have roamed freely during the night in a common herd, are retrieved by a boy or man of the camp. Packing and loading are done by all, usually in a habitual way but with no formal division of labour. The total process of breaking camp may take about 1^ hours.

Most family members ride on top of the loaded donkeys during the migration, while one — boy, man, girl, or occasionally woman — follows on foot and drives the beasts. Men who own horses usually ride these at the head of the caravan. They thus determine the route and decide on the place to camp — usually after roughly 3 hours of travel at a brisk pace. Tent sites are seized by the men, sometimes with a certain amount of argument, and the donkey caravan disperses to these sites. All household members co-operate in unloading the beasts and pitching the tent, the men moving the heaviest pieces. The donkeys are let loose and driven off by a child, or several children, while a larger child is sent off for brush to make a fire for tea.

The sheep and goats arrive in camp at about noon; after these are milked the women prepare a meal. Various domestic tasks are performed in the afternoon; just before sunset the flock is milked again, and the evening meal is taken late, just before sleep.

The work of tending the animals consists mainly of herding and milking. The shepherd for the main flock is almost always a male; as he is occupied with the flock from c. 4 a.m. to 6 p.m. he cannot simultaneously serve as head of household and perform the male domestic tasks in the tent and during migration. Boys down to the age of 6 are therefore frequently used as shepherds, while married men only exceptionally do such work. The smaller and less wide-ranging flocks of lambs and kids are usually looked after by smaller children of both sexes; or they may be divided, the weaned ones accompanying the main herd, the unweaned ones tethered in the tent.

Milking is done by bdth sexes, but mostly by women. The animals are fairly easy to control and may be milked individually by a single person. But a simpler and more systematic arrangement is preferred, whereby the flock is driven by shepherding children into a spear-head formation and forced to pass through the narrow point at its apex, where they are held by the shepherd or another male, while being milked by two or more persons on either side of the shepherd. Thereby those who do the milking need not move their pails, and the milked animals pass through and roam off, separated from the unmilked animals.

Household economy: A picture of the resultant economy and standard of living of the average Basseri household may be formed and to some extent cross-checked by a little simple arithmetic. The average suggested above of somewhat less than 100 sheep/goats per tent is based on Basseri estimates and agreed with a few rough counts that I made of the flock associated with tent camps. Only very few herd owners have more than 200 sheep, while informants agreed that it was impossible to subsist on less than 60. To maintain a satisfactory style of life it was generally considered that a man with normal family commitments requires about 100 sheep and goats — so at present a majority of the Basseri fall somewhat short of this ideal. However, the flocks in 1958 were still suffering from losses experienced during and after a very bad season in 1956–7, and were thus unusually small.

The market value of a mature female sheep was at the time of fieldwork c. 80 Tomans, so the average flock represented a capital asset of c. 7,000 T., (roughly £ 350 or $ 1,000). In a different context, I was able several times to discuss family budgets in detail. The consensus of opinion and data is that a normal household needs to buy goods for an average value exceeding 3,000 T., while a comfortable standard of living implies a consumption level of 5–6,000 Ts’ worth of bought goods per year.

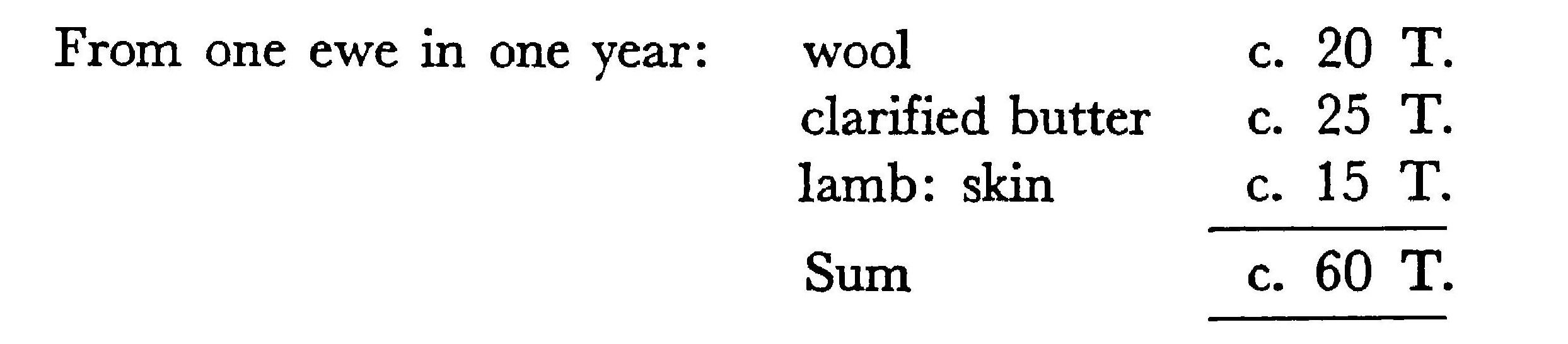

These requirements seem at first sight out of proportion to the productive capital of 8,000 T. corresponding to the ideal average of a flock of 100 head. However, an estimate of the income produced by a fertile ewe gives consistency to the picture. In 1958, its estimated value was:

From one ewe in one year:

| wool | c. 20 T. |

| clarified butter | c. 25 T. |

| lamb: skin | c. 15 T. |

| Sum | c. 60 T. |

leaving lamb’s meat, buttermilk, and curds to be consumed by the nomad and his family. This sum, formerly greater, has suffered a severe reduction with the collapse of prices on “Shirazi” lambskins, until recently bought for as much as 50 T. Yet allowing both for a 10 % population of rams and billygoats in the herd, and a 15 % per annum rate of replacement of stock, a flock of 100 head should give a total product per annum of more than 5,000 T. value at 1958 prices.

Estimates based on different kinds of data thus agree on an average net income from the sale of produce of 3–5,000 T., or roughly £ 200, per annum per household for the Basseri in 1958, together with a considerable production of foodstuffs consumed directly, such as milk, milk products, and meat. This confirms one’s overwhelming subjective impression of a high standard of living among the Basseri nomads relative to most populations in the Middle East.

Household maintenance and replacement. The description so far has been static, and has not touched on the crucial problem of the continuation and replacement of household units as a process spanning the generations. These problems are particularly interesting among pastoral nomads, and may be discussed in terms of the concept of household “viability” used by Stenning (1958) in his article on the pastoral Fulani.

The household units of the Basseri are based on elementary families; and this means that after a new marriage, when the nucleus of a new family is established, this nucleus forms a new and independent household. A woman joins her husband upon marriage, and after a few nights in a separate small bridal tent lives with him and his natal family in their tent. But the young couple’s period of residence there is usually brief and rarely extends beyond the birth of the first child; as soon as possible they establish themselves in a separate tent as a separate household. As such they form an independent economic unit, and to be viable sis such they must possess the productive property and control the necessary labour force to pursue the pastoral nomadic activities described above. In the following I shall try to describe the standard Basseri arrangements whereby productive property in the form of herds and equipment, and additional labour force, are provided to secure the viability of newly established, or in other respects incomplete, elementary families.

Though the herd of a household is administered and utilized as a unit, individual members of the household may, as noted, hold separate title to the animals. It is therefore possible for a young person to build up some capital in flocks while he still lives in his parents’ tent. In times of plenty fathers frequently give a few animals to their younger sons, partly to stimulate their interest in caring for the animals, partly to test their luck as herd owners. Boys whose fathers are very poor usually seek work as shepherds for others; and in return for such work they are given a few lambs every year, and with good luck can build up a small herd that way.

The main transfers, however, take place at the time of marriage. The various transactions at marriage will be analysed below; we are here concerned only with those that contribute directly to setting up the new household. The expense of this is carried by the groom’s father, who provides a cash bride-price which the bride’s father is expected in part to use to equip his daughter with rugs, blankets, and household utensils, while the women of both households may contribute labour to weave cloth for the new tent. A payment of sheep is also usually made, and it is expected that these will later be passed on by the bride’s father to his son-in-law, though this is not always done.

These customs contribute to the setting up of the married couple in a separate tent; but they do not provide the new household with the necessary flocks. This is achieved by a practice explicitly regarded by the Basseri as anticipatory inheritance, whereby a son at marriage receives from his father’s herd the arithmetic fraction which he would receive as an heir if his father were to die at that moment. In such divisions, the right of the “widow” to a small share is recognized; otherwise only agnatic heirs are considered, and close agnates eliminate all more distant agnates, while a man often reserves for himself a share equal to that he allots to each son.

For example, as a boy a certain Alamdar, one of 5 brothers, was given a flock of 60 one-year-old lambs and kids; but he had bad luck and nearly all the animals were lost, his father appropriating the few that were left. When he married, his father made the bride payments and then gave Alamdar 1/6 of his herd (there being 5 sons plus himself and his wife to share).

In another case, Barun, the eldest of 6 sons, was married. At the time his father had 145 sheep, 9 donkeys, and 3 horses. The bride payment asked was 20 sheep. His father, wanting to set up his son well, waived his own right to a share, allotted 5 sheep to his wife, leaving 20 sheep as the share for one son. Barun also received 3 donkeys (which, being forbidden as food, increase more rapidly than sheep) and 1 horse. Barun received no return from his father-in-law on the bride payment.

A few years later his brother was married. Meanwhile the father’s flock had grown to 200, and the groom received 40 sheep as his share as one of 5 remaining sons. No adjustment was made because of this difference between the shares given the first and the second sons on their marriage. In fact Barun’s flock had meanwhile grown to 50 sheep; but even, had he been propertyless by then he would have had no right to a further share. In such divisions, bride payments are always made before the departing son is allotted his share, while payments received on girls are added to the father’s estate at the time of receipt, and sons who have separated from him before that time have no rights in such payments, and no other remaining claims on their father’s flocks.

On the death of the father, however, a certain estate remains to be allocated. If the old man was living with a married son, or even a married daughter, all household property is regarded as the property of the resident spouses, with possible adjustments made in the case of particularly valuable items such as rugs etc. If a household is dissolved by the death of its head, his heirs divide the property. In such cases, daughters who are married in their natal tribal section, or are present for other reasons at the time of their father’s death, usually receive a share of his estate.

In addition to flocks and household property, some nomads also own land, or money in a bank. Such property is never passed on while the owner is alive, but is divided by his heirs on his death. Though the claim is usually made that Koranic inheritance rules are observed with respect to land and money, they are in practice usually side-stepped, and the estate appropriated by the agnatic heirs. In cases of conflict over inheritance, the tribal authorities usually defer to the decision of civil or religious courts, where the rights of a daughter to half the share of a son are upheld. To forestall daughters in their claims to a share of the land, male agnatic heirs frequently give them for a few years “gifts” of a reasonable fraction of the produce of such lands.

Through such practices, a marrying couple are provided with the property in animals and equipment which they require to set themselves up as an economically independent household unit. But to maintain themselves in this position they must perform the whole set of tasks connected with pastoral nomadic subsistence. This requires the co-operation of at the very least three persons: a male head of household who performs male tasks around the tent and connected with the migration, a woman to perform female domestic tasks, and a male shepherd. Only in a restricted phase of its development, while it contains adolescent children, can an elementary family be expected to contain this necessary personnel. The ideal, and in fact relatively common, situation is one where the husband and head of household remains close to the tent, and accompanies the caravan on migration, while one or several sons serve as shepherd boys. Where the family alone does not contain this labour team, other arrangements must be made.

Such arrangements may be of several kinds. A shepherd or servant may be engaged; childless couples may adopt a brother’s son or other close male agnate; while most households enter into small co-operative herding units to secure additional labour by sharing the burdens.

The relationship between a shepherd or servant and his master is based on an explicit economic contract, whereby the former is supplied with food and shelter, new clothes at Nowruz (Spring equinox, the Persian New Year), and a salary of no more than 40–50 T. per year. Such contracts are taken only by propertyless, usually unmarried men; only rarely is the relationship so stable and remunerative for the shepherd that he can establish a family of his own.

The partners in such contracts are rarely close kin; on the other hand there is considerable reluctance to engage a shepherd or servant who is an outsider, and even more so if he is a stranger, since it is necessary to place considerable trust in him, both with regard to his treatment of the animals, and his respect for the family and property of his master. He lives as a member of the household by which he is engaged, but generally eats separate from, or subsequent to, his master. The ambition of such servants and shepherds is to establish themselves with a family as a small independent herd owner; and this goal they not infrequently achieve after 10–15 years of work. Less than one household in ten has the means to employ outside labour in this way.

Occasionally when a marriage proves barren, the childless couple may adopt a close agnate of the husband, preferably his brother’s son, as their own child. In such cases the boy is used as shepherd as a real son would have been, and ultimately inherits his foster-parents’ estate to the exclusion of other heirs.

Both these devices serve to maintain the isolated, individual household as a viable unit by supplementing its labour pool from outside sources. This independence and self-sufficiency of the nomad household, whereby it can survive in economic relation with an external market but in complete isolation from all fellow nomads, is a very striking and fundamental feature of Basseri organization.

However, to facilitate the herding and tending of the flocks, Basseri households usually unite in groups of 2–5 tents. These combine then- flocks and entrust them to a single shepherd, and co-operate during milking time. As noted, a shepherd is readily able to control a herd of up to 400 head, and there is some feeling that very small herds are relatively more troublesome; while milking is made easier when numerous people combine to drive and control the herd.

The tents of such a herding unit are always pitched together, in a line or a crescent, with the herd spending the night beside them; and when the herd is driven in for milking, most of the members of the unit assist. But each woman, or, occasionally, man, milks only the animals belonging to her or his own household, and generally departs when they are all done, not waiting for the other members of the herding unit to complete their milking.

The relationship among members of a herding unit is contractual, and is always regarded as a partnership among equals. Household heads are free to establish the relation with anyone they wish inside their own tribal section. The division of labour between members is based on expediency, and the person or persons who serve as shepherds are in no way regarded as the servants of the others; rather, the work they do is regarded as a favour, and rewarded by gifts of lambs. At any time, a member of a herding unit may withdraw from that group and work alone, or join another unit; and through time the constellations of households in herding units change completely.

By joining a herding unit, households can persist without the full complement of personnel to make them viable as fully independent units. It is sufficient that one of the component members of a herding unit provides a shepherd; and smaller households are thus motivated by practical considerations to join households with a secure labour supply, while these are interested in increasing their income by serving as herders for others.

Such practical considerations, as well as friendship and enmity, and a belief in the good or bad herding luck of different persons, seem to dominate a man’s decisions about which herding unit he joins. Thus when disagreements arise, or the compositions of households change, herding unit membership tends to change.

Considerations of nearness of kinship, on the other hand, seem to be irrelevant to the composition of herding units. While married sons initially tend to retain their flocks in the old herd, and thus stay in the herding unit of their father, these bonds are freely broken at any time; and there are no apparent regularities in the kinship composition of the herding units of the camp with which I spent most of my time. These are illustrated in Fig. 10; and in every unit, persons have combined with distant relatives and non-kin in spite of the presence in camp of very close kin. The competition of herding units thus seems to be determined by considerations of the availability of labour, the sizes of herds, and the distribution of friendship and mutual trust.

In this chapter I have tried to describe the basic unit of Basseri social organization: the household occupying a tent, and the activities whereby this unit maintains itself and reproduces itself. The picture is one of relatively great independence and self-sufficiency, whereby many households are viable in complete isolation from other Basseri, though strongly dependent on an external market in sedentary and agricultural communities. For purposes of more efficient herding, however, these households combine in small herding units, the composition of which reflects practical expediency for herding purposes, rather than kinship or other basic principles of organization.

Chapter III: Camps

During two or three months of winter, an extreme dispersal is advantageous for the Basseri population, since the pastures on which they depend at that time are poor but extensive. In winter therefore, the groups of 2–5 tents associated in herding units make up local camps, separated by perhaps 3–4 km from the next group. At all other times of the year camps are larger, and usually number 10–40 tents. This group migrates as a unit, and its tents are pitched close together in a more or less standard pattern. In the summer there is a certain tendency to fragmentation, but camps still remain larger than single herding units, even if the tents are generally further apart.

These camps are in a very real sense the primary communities of nomadic Basseri society; they correspond to hamlets or small compact villages among sedentary peoples. The members of a camp make up a very clearly bounded social group; their relations to each other as continuing neighbours are relatively constant, while all other contacts are passing, ephemeral, and governed by chance. In the following I shall attempt to describe the composition of such camp groups among the Basseri, and analyse their internal structure and organization.

There is one point that deserves emphasis, and that offers the point of departure for the following analysis. Unlike a sedentary community, which persists unless the members abandon their house and land and depart, a camp community of nomads can only persist through continuous re-affirmation by all its members. Every day the members of the camp must agree in their decision on the vital question of whether to move on, or to stay camped, and if they move, by which route and how far they should move. These decisions are the very stuff of a pastoral nomad existence; they spell the difference between growth and prosperity of the herds, or loss and poverty. Every household head has an opinion, and the prosperity of his household is dependent on the wisdom of his decision. Yet a single disagreement on this question between members of the camp leads to fission of the camp as a group — by next evening they will be separated by perhaps 20 km of open steppe and by numerous other camps, and it will have become quite complicated to arrange for a reunion. The maintenance of a camp as a social unit thus requires the daily unanimous agreement by all members on economically vital questions.

Such agreement may be achieved in various ways, ranging from coercion by a powerful leader to mutual consent through compromise by all concerned. The composition of a camp will thus indirectly be determined by the available means whereby the movements of economically independent households can be controlled and co-ordinated. In a sense, recruitment to a camp group is not a once-and-for-all allocation by some basic criterion to a stable group, but a daily process dependent on the attainment of agreement within the group. Rather, therefore, than start my analysis by scrutinizing some existing camps, so as to discover hidden principles of kinship which underly their composition, I shall base my analysis on the processes whereby the unity of a camp may be maintained.

This task is simplified by the existence of a recognized leader in every camp, who represents the group for political and administrative purposes, and on whom this analysis can focus. Leaders of different camps may be of two kinds: headmen (sing.: katkhoda) formally recognized by the Basseri chief, and, where no headman resides in camp, informal leaders (sing.: riz safid, lit. “whitebeard”) who by common consent are recognized to represent their camp in the same way as a headman does, but without the formal recognition of the Basseri chief and therefore technically under a headman in a different camp. The distinction between these two categories has broken down somewhat since the Iranian Army assumed administrative control over the tribe two years ago, because of the practice of the administering Colonel to elevate all camp leaders to the status of formally recognized headmen. This, however, has as yet had little effect on their position in their own camp.

A leader holds his camp together by exercising authority and/or by his influence in establishing and formulating unanimous agreement within the camp on questions of migration and camp sites. The position of the leaders of camps may thus be analysed in terms of their sources of authority, grouped under the following headings: The required authority to dictate decisions may depend on (a) political power derived from the central chief, (b) economic or (c) military power within the camp. The weaker and more diffuse influence sufficient for the task of establishing and formulating general agreement may derive from additional sources generally subsumed under the heading of (d) kinship.

Relations to the chief. An analysis of the position of the Basseri chief is given later; in the present context it is sufficient to know that he is the head of a very strongly centralized political system and has immense authority over all members of the Basseri tribe. However, the system does not depend on any delegation of power from the chief to subordinates. The ordinary leaders of tent camps, being without any formal recognition by the chief, naturally cannot base their authority on his support. But even the headmen which he formally recognizes are not vested by him with any special coercive means. They transmit, on occasion, his orders to the camp in general, and then in a sense speak with all the authority which such an order carries; but when they exercise their discretion in their personal capacity as headmen, the chief is in no way committed to their decisions, and when consulted makes his own decision without reference to possible previous rulings by the headman. This lack of support from above, except in .special cases when the chief consciously tries to change the political constellations within a group, is also revealed in questions of succession. The office of headman is usually inherited in male line, with some regard for seniority. However, the members of a headman’s group insist on their right to appoint anyone of their number as the successor, and the chief is expected merely to assent to their choice. The tribesmen also claim that they may depose their headman at will, and in such cases the chief reportedly rarely supports the old incumbent. The chief himself expressed this principle from his own point of view, saying that it is most convenient to have the headman who is most acceptable to his own group, since he is able most readily to effect the commands of the chief regarding that group. In other words, the chief in his dealings through the headmen draws on the power and influence which they have established already by other means, and does not delegate any of his own power to them. The prestations that flow from the chief to the headmen are mostly gifts of some economic and prestige value, such as riding-horses and, especially in the past, weapons. The headman is also in a politically convenient position since he can communicate much more freely with the chief than can ordinary tribesmen, and thus can bring up cases that are to his own advantage, and to some extent block or delay the discussion of matters detrimental to his own interests. None the less, the political power which a headman derives from the chief is very limited.

Economic power. Headmen are never among the smallest herd owners in their group, and incumbency in the status calls for certain moderate expenditures on hospitality and general appearance which exclude the poorest strata. But the economic position of a headman is subject to the same fluctuations as that of any other herd owner, and there is little correlation between great wealth and headmanship. I know clear examples of serious economic regression in the case of some headmen, and this does not appear to affect their position greatly. Informants claimed that where a popular headman is impoverished by a serious loss of animals over a long period, the members of his group may decide to reconstitute his herd by voluntary or percentile gifts of animals. As for the authority which may be derived from wealth, persons who do have great wealth in flocks seem to have few techniques whereby they can convert such economic superiority directly to political power. The big herd owner has greatly enhanced prestige, but he does not manipulate his wealth to gain political control over a larger group of dependent followers; thus, where parts of his flocks are sub-let (cf. pp. 13–14) to others, contracts are preferably established with persons in other camp groups, so as to spread the economic risks, rather than within the camp, to gain control over camp members. The power and influence of headmen can thus to only a, very small extent derive from economic sources.

Military power. Dominance by headmen through force is similarly incompatible with the usual forms of Basseri organization. A headman has no access to such sources of power outside the camp group, and is not empowered by the chief with special privileges to utilize force. As pointed out, each tent is an autonomous unit under its head, who has direct political relations with the chief without reference to his headmen, and small groups of 2–5 tents in a herding unit are economically completely self-sufficient. The only source of force for a headman is thus within his own tent, and to some extent within his own herding unit — a ven small base from which to attempt to tyrannize a whole camp. I do know* of a few relevant cases, one where a headman has disproportionate influence because of the activities of his group of married and unmarried sons, feared as bandits and thieves; the other is in the same group, where five brothers and two paternal cousins were able to challenge their headman’s authority in a conflict still not resolved when I left the tribe. These men were able to meet force with force because of their numbers, and because they were unmarried, and therefore less vulnerable to the threatened reprisals. These cases, however, were regarded by the tribesmen as unusual and deplorable; and few headmen or other camp leaders rely to any great extent on the use of force to maintain their position.

Kinship. There is thus no basis in the Basseri system of organization for the exercise of a strong commanding authority by headmen, and even less by informal leaders of camps. The camp leader is dependent on his ability to influence camp members, to guide and formulate public opinion in the group. The authority required for this activity is derived from sources within the camp, and the composition of persisting camps reflects these sources. They are: agnatic kinship in a ramifying descent system, and matrilateral and affinal relations. In the case of an established leader the personal esteem which accrues to him from his experience and proved ability is of course important; but this does not significantly affect the composition of the camp, and is irrelevant to the crucial question of succession to leadership. The structurally significant sources of camp leader authority appear to be only those two named. Each of these requires separate discussion.

In matters of succession the agnatic line is given prominence among the Basseri, as among other tribal people in the Middle East. We have seen how sons and subsidiarily collateral patrikinsmen are favoured in inheritance to the extent of usually excluding daughters from access to their legally rightful share. Where membership in formal groups is transmitted by descent, the line chosen is always the patriline — thus the son of a Basseri is regarded as Basseri even though his mother may be from another tribe or from a village, while a Basseri woman who marries outside the tribe transmits no rights in the tribe to her offspring. The importance of agnatic kin is reinforced by an ideology’ of respect and deference for Fa, FaFa, and FaBr, and solidarity of Br.s, and the ideal of solidarity is extended laterally to patrilateral cousins and beyond.

There is thus a continual process of formation of small patrilineal nuclei: groups of brothers held together by their joint rights in their father’s flock before their marriage, and certain residual economic interests, as well as the ideal of solidarity, after their marriage. There is also a normative extension of this solidarity to agnatic collaterals. But the genealogical knowledge that is necessary to make such an extension effective is poorly developed. Only few men know their own pedigrees in any depth (though a few informants were able to name as many as 8–11 ascending generations), and the genealogical map of agnatic collaterals is even less generally known.[1] As a source of influence over camp members, agnatic kinship can thus be utilized by leaders only to a limited extent — while the acceptance of lineal authority from ascendants is strong, the strength of lateral solidarity is slight and may even be too weak to keep brothers together. More frequently it seems that references to agnatic kinship are used as formal justifications, by both parties, for the influence that accrues to leaders by virtue of other factors.

Patrilineal descent is also of prominent importance in succession to the formal office of headman. As noted above (p. 27), the chief must confirm succession and insists on his right to appoint any new headman he likes, while the tribesmen similarly claim the right to choose their own leader — again independently of the candidate’s kinship position. But with strong lineal identification, and succession by the son to other of his father’s formal statuses, the headman’s son is by far the strongest pretender and the most convenient candidate for the compromising parties. In cases I know where the preceding headman was not the present incumbent’s father or brother, reference to this fact was usually avoided. Patrilineal succession is thus the rule, usually with due regard to the relative seniority of the headman’s sons in terms of age, and not, in cases of polygyny, with reference to the status of their mothers.

While patrilineal kinship is used to conceptualize larger kin-based groups and is the vehicle for the transmission of some rights, bonds of solidarity also tie mafrzkin together. As is found so frequently elsewhere among peoples with a patrilineal organization (e. g. Radcliffe- Brown 1952), the relation between a mother’s brother and a sister’s child is also, among the Basseri, an indulgent one; and the term “mother’s brother”, Dai, implies easy familiarity. As a term of address it is used frequently to any related elder man, and it is also used “incorrectly” reciprocally by a mother’s brother as a term of address to his sister’s children (and even occasionally to other children, including his own) on the pattern of the reciprocal grandparent/grandchild usage. The leader of the camp where I spent most of my time is known as Dai Ghulam, “uncle Ghulam”, by all junior members of the camp; and though this is exceptional, it indicates the importance attached to matrilateral kinship.

Finally, affinal relations are also regarded as relations of solidarity and kinship; and they appear to be most effective in establishing political bonds between tents. This effectiveness can only be understood through an investigation of the marriage contract and the transfers involved in marriage, and the authority distribution between the persons concerned.

The authority to make marriage contracts for the members of a household is held by the head of that household. Thus a married man may arrange subsequent marriages for himself, while all women and unmarried boys are subject to the authority of a marriage guardian, who is the head of their household, i. e. the father if he is alive; otherwise a brother or a father’s brother. A marriage is thus a transaction between kin groups constituting whole households, and not merely between the contracting spouses. Characteristically, a man refers to his daughter-in-law as arosam — “my bride”. The rule of exogamy bans only descendants, and ascendants and their collaterals of the first degree. Thus no larger kin group than the “tent”, i. e. the elementary family, is normally made relevant to the marriage transaction. Divorce, though legally simple for the man, is a rare occurrence; in one of the two cases I know the marriage was dissolved by the wife.

The marriage contract (aghd-e-nume) is often drawn up and written by a non-tribal ritual specialist, a mullah or a holy man. It stipulate certain bride payments, classified by the Basseri as: shirbahah, “milk-price”, in payment for the girl and the domestic equipment she is expected to bring, and mahr, a divorce or widows’ insurance or fine, a stipulated sum which is the woman’s share of her husband’s estate and which is also payable in the event of divorce.

A token gift of a couple of cones of sugar is also given by the groom to the senior mother’s brother of the girl.

In the betrothal period the prospective groom is also expected to provide his girl with gifts at all calendrical festivals, and to perform various bride services in the form of continual minor favours to his parents-in-law.

At the time of the wedding, however, all these transactions are completed. There are no outstanding debts either way between affines, apart from the expectation that the father of the girl will return to his son-in-law some of the animals given in bride payment. The woman retains no transferable rights in her natal household. Yet the affinal relation is regarded as warm and enduring by the Basseri, and much emphasis is placed on its maintenance. The levirate and sororate are practised almost without exception, even against the will of the women concerned. Sister exchange marriages (gav-ba-gav, “cow-for- cow”) are frequently arranged. And the renewal of affinal ties in each succeeding generation by further marriages is also sought. These subsequent marriages are not regarded as delayed exchange marriages, since the direction of transfer of the woman is immaterial, and not systematically reversed. Their implications are rather like those of marriages between parallel cousins, to counteract the weakening of kin ties that results from increased collateral distance. This tendency to renew affinal ties in every generation may be seen in the genealogical tables given elsewhere (Figs. 2, 10).

The relationship between affines among the Basseri is thus a strong and important one, which people try to maintain through the generations and which is used to reinforce even close matrilateral bonds, and the bonds between close agnatic collaterals. That this should be so may seem surprising. From general anthropological experience one would expect the relation between affines, particularly brothers- in-law, to be one of tension (see e. g. the general formulation by Homans 1950: 250). However, the situation becomes understandable against the background of other features of Basseri organization.

The autonomy, both economic and political, of individual Basseri tents has already been repeatedly emphasized; it is a fundamental feature of Basseri organization. These separate households are structurally united only where there is a community of vested interests between persons in two or more guch units. With the pattern of anticipatory inheritance described above, the division of the sibling group between discrete autonomous households is initiated even before the death of the father, and on his death, the division of his property is completed; no estate remains to tie siblings together. Naturally, bonds of sentiment generally remain, but these depend on past experiences and the continuation of good feelings, and do not arise from shared interests in a contemporary situation. Matrilateral kinship similarly does not imply a shared estate of any kind, since the woman retains no transferable rights in her natal home.

The affinal relation, however, does in a sense imply shared rights in an estate — in the woman herself. A woman’s father or brother have certain residual rights over her, e. g. as marriage guardians in the event of her widowhood; and the strength of her relations to her kin is maintained by frequent — where possible, daily — visits in her natal tent. At the same time, the honour of her kinsmen is affected by her life and activities; she can both enhance and harm their prestige. Her kinsmen thus retain interest in a married woman, and are to some extent able to exercise control over her; they also desire good relations with her husband to increase this control of theirs over her and her situation.