Gaspard d’Allens

Investigation into ecofascism

February 1, 2022

Part 1: How the far right wants to reclaim ecology

“Man must defend his biotope against invasive species”

“We must kill the invaders and thus save the environment”

“This country deserves a dirty racial civil war”

“The true nature of Europeans is to be a Waffen SS”

Part 2: From the nineteenth century to Zemmour, ecofascism contaminates the political debate

An ideology that is part of “the conquest of minds”

In Europe as in France, the far right monopolizes the foundations of ecology to justify its identity and nationalist discourses. Who are the ecofascists? Why do they appropriate ecology? Is an alliance with Éric Zemmour possible? Reporterre conducted the investigation, in two parts.

Part 1: How the far right wants to reclaim ecology

The air is brown and those nostalgic for fascism[1] are draped in green. On the far right, today, a nebula of small groups monopolize the theories of collapse and use ecology to feed their obsession with identity. The threat is real and the situation unprecedented, fuelled by the climate peril, the migration crisis and the trivialisation of xenophobic discourse. The “ecofascist” temptation is, more than ever, topical.

Some groups are calling for the creation of “Identity Zones to Defend” (Zid), others are buying farms in the countryside to “defend the land”, others are heavily arming themselves in anticipation of a hypothetical civil war. Some learn the basics of wildlife in the wilderness and claim to be degrowth. The result of a disconcerting ideological tinkering, these movements combine a culture of healthy eating with a fascination for weapons, hatred of migrants and gardening, virilism and neopaganism[2].

The authorities are beginning to pay attention to this. The national coordinator of intelligence and the fight against terrorism, Laurent Nuñez, evokes ”a movement that is developing”, like white supremacists in the United States, and which “does not hesitate to call for clandestine techniques and the practice of survivalism”. In the context of the environmental catastrophe, these disparate currents mark a profound recomposition of the fascist movement.

“Man must defend his biotope against invasive species”

“Ecology is a godsend for them,” philosopher Dominique Bourg told Reporterre. It allows them to renovate themselves, to reaffirm themselves and to regain their importance in the era. For him, this recuperation is, after all, logical: “They have been fantasizing about decline for decades. Climate change is grist to the mill. It feeds their belief in the apocalypse, also feeds their imagination marked by the fear of invasion and disappearance.”

As early as 1999, one of the ideologues of the far right, Guillaume Faye, predicted “a clash of civilizations” and a ”convergence of catastrophes”—economic, geopolitical and environmental. For the fascists, the prophecy is coming true. The climate crisis is accelerating the “great replacement”, a theory popularised by the writer Renaud Camus, who claims that the so-called “native” “European peoples” will gradually be replaced by people of immigrant origin. To resist this, the ecofascists believe that it will be necessary to monopolize and protect the few territories where the “native populations” could still live, and to fight against the “hordes of migrants” who flee other continents that have become inhospitable.

Ecology here serves as a screen for segregationist thinking. Since the 1970s, the intellectuals of the Groupement de recherche et d’études pour la civilisation européenne (Greece) have been the main instigators. They are carrying out ideological work to incorporate the themes of ecology into the far right. The philosopher Alain de Benoist, the founder of Greece, says he is decreasing[3] and uses the concept of nature to legitimize “selection, inequality, and hierarchy.”

At the heart of these theories lie the hatred of the other, the cult of the border and the fear of miscegenation. “True ecology must preserve human diversity by maintaining the great races in their natural environment,” writes Alain de Benoist. “Man must defend his biotope against invasive species. We must protect ecosystems, starting with human ecosystems that are nations,” continues Hervé Juvin. This National Rally executive created the association Les localistes! with the former member of France Insoumise Andréa Kotarac. In its manifesto, this movement assures that “all of France is a zone to be defended”.

“This approach is ethno-differentialist,” historian Stéphane François explains to Reporterre. It is no longer a question of establishing a hierarchy between biological races, but of drawing watertight boundaries between “cultures” or “civilizations”. This vision corresponds to what the philosopher Malcolm Ferdinand refers to as the “ecology of Noah’s ark”. By ecofascism, we should understand a policy that wants to preserve living conditions on Earth, but for the exclusive benefit of a minority, a white one at that.

“Embarking on Noah’s ark is first of all to act, from a singular point of view, of a set of limits both in the load that the Earth can bear and in the capacity of its ship. To climb on Noah’s ark is to leave the Earth and protect oneself behind a wall of anger. It is to adopt the survival of certain humans and non-humans and to legitimize the use of violent selection of boarding,” the researcher wrote in his book A Decolonial Ecology.

“We must kill the invaders and thus save the environment”

This vision is not only theoretical. It is also translated into action. On March 15, 2019, in Christchurch, New Zealand, a man armed with weapons of war, Brenton Tarrant, opened fire in a mosque, killing 51 people and wounding 49 others. A few minutes earlier, he had distributed a seventy-four-page manifesto in which he detailed his ideological journey and openly claimed to be an “ecofascist”. “Immigration and global warming are two sides of the same problem,” he wrote. “The environment is being destroyed by overpopulation, and we Europeans are the only ones who are not contributing to overpopulation. [...] We must kill the invaders, kill the overpopulation, and thus save the environment.”

On August 3 of the same year, another attack took place in El Paso, Texas, in a supermarket frequented by Hispanics. Patrick Crusius killed 23 people and wounded 26 others with automatic weapons. His manifesto is even more revealing than Brenton Tarrant’s: “Our lifestyle is destroying our environment. It creates massive debt for future generations. [...] I love the people of this country, but they are all too stubborn to change their way of life. Under these conditions, the next step is to reduce the number of people who consume resources in America. If we can get rid of them in sufficient quantities, then our way of life can become a little more sustainable in the long run. Later, in his manifesto, he declared that he had prepared all his life for a future that does not exist.

These two cases are far from being epiphenomena. In Europe, several small armed groups also claim to be ecofascist, while many far-right people practice survivalism. According to Stéphane François, “the core of ecofascist activists in France numbers 200 to 300 people. Around it, there is a more diffuse nebula where this type of idea is propagated in particular by magazines such as Elements, Earth and People, Penser et agir or the publishing house Culture & Racines. Their readership is around 20,000 people.”

These journals advocated a romantic conception of ecology, giving pride of place to regional poets — Giono, Mistral, etc. — and the classics of the French neo-Nazi library — Saint-Loup or Robert Dun, a former SS man who was the precursor of a racialist ecology. Against an ecology “colonized by the cosmopolitan left”, their ecology promotes the figure of the peasant rooted in his regional environment and makes the link between the people, the land and blood. Their ecology is inseparable from a certain vision of nationalism, and justifies the need for a revolution that is both anti-capitalist and identity-based.

With digital technology, these messages are now even more resonating. They circulate via social networks, YouTube channels and encrypted messaging services. In the course of its investigation, Reporterre slipped into several eco-fascist groups that exchange on the Telegram application. They are called NEO (195 subscribers) or Ecofash propaganda (2,600 subscribers). Its members quietly disseminated visuals and propaganda texts calling for “defending our race” and extolling pell-mell “Aryan environmentalism”, life in the woods or the misdeeds of the industrial revolution. There are also slogans such as “Save the bees, not the migrants” or “The earth does not lie”.

“This country deserves a dirty racial civil war”

Recently, in France, several court cases have revealed the imminence of the peril. The anti-terrorist prosecutor’s office has also been seized several times. On Tuesday, November 23, 2021, a group of far-right survivalists called Recolonisons la France and composed of thirteen people was arrested by the police who discovered an arsenal of 130 weapons during the arrest. The members of this group are young and come from the gendarmerie. This structure defined itself as a “community group of patriotic survivalists”.

A few days earlier, two ultra-right activists were also arrested in Occitania. They were planning to carry out an attack and described themselves as “accelerationists”. They were convinced of the arrival of collapse and civil war, and wished to encourage clashes between communities.

Last October, three other far-right survivalists were indicted in the region of Saint-Étienne (Loire), after the discovery of several weapons and ammunition in their home. On one of the sites searched, a living base had been set up with a large stock of food and medicine. A submachine gun, an assault rifle, two shotguns and three grenades, as well as 2,500 rounds of ammunition were also recovered.

Just one year ago, in the Puy-de-Dôme, a 48-year-old man murdered three gendarmes and wounded a fourth. He was armed with a Glock and an AR-15 assault rifle and possessed combat equipment. According to the prosecutor, Éric Maillaud, the madman was “a Catholic, very practicing, even extremist. Survivalist. It would seem that he was convinced that the world was coming to an end.”

In general, the survivalist current is very permeable to far-right ideas. He is also well represented in the police. In an investigation in July 2020, Mediapart revealed exchanges between several members of the security forces in Rouen (Seine-Maritime). Police officers defined themselves as fascists and survivalists, and stockpiled weapons and food. “This country deserves a dirty racial civil war”; “I want a Norman, fascist, barbaric state, and for us to meet among ourselves, among whites,” they wrote on their private WhatsApp group.

“The true nature of Europeans is to be a Waffen SS”

“At its origin, survivalism stems from a profoundly reactionary thought,” says sociologist Bertrand Vidal. The movement was created during the Cold War in response to the Soviet threat. “Its founders, including Kurt Saxon, wrote survival advice and fiction published by the printing press of the American Nazi Party. At the root of survivalism, there is a dichotomizing consciousness of the world: on the one hand there are the chosen ones, the winners of the end of the world, and on the other side the wretched of the earth, those who deserve to disappear. Logically, the far right has been able to curl up in this vision.”

In 2016, one of the pundits of survivalism, Piero San Giorgio, declared that the true nature of Europeans “is to be a Waffen SS, a lansquenet, a conquistador... “. He added that “we make sure that people who should not have existed exist... We save the sick, the disabled... It’s very good, it gives you a good conscience, but that’s not how you build a civilization, that’s how you destroy it.”

His book Surviving Economic Collapse has sold widely and has been translated into ten languages. In his books, he theorizes the concept of the “sustainable autonomous base” (BAD) as a means of survival. According to him, it is necessary to acquire properties in rural areas in order to establish entrenched bases that are self-sufficient in both food and energy, with enough to last a difficult period, to participate in a civil war that he considers inevitable.

Piero San Giorgio organizes with the fascist Alain Soral and his association Equality and Reconciliation survival courses in the south of France near Perpignan (Pyrénées-Orientales). He also promoted survivalist articles on Alain Soral’s e-commerce site Prends le maquis, of which he was a partner and shareholder. A flourishing business. Alain Soral himself has settled in the countryside. He bought a farm in Ternant, in the Nièvre region, in a place called La Souche. On the far right, several activists have chosen to return to the land or, at least, to live far from the metropolises. This withdrawal to the countryside is seen as a first step, before setting out to reconquer the territory.

Génération Identitaire thus invites us to “develop community resilience strategies in abandoned spaces” to “create an economy that feeds its members or a significant part”. “This can only be done in the countryside,” says one of its spokesmen, Clément Martin, in a recent article. “In every war, there is a vanguard and a rearguard: the two positions do not contradict each other, they are complementary. It is important to keep in mind that in order to endure, our ideal must be embodied in families where the children are happy to grow up in the heart of a preserved terroir. This is why it is imperative to reconquer our countryside and make it our Zid: identity zones to be defended,” he wrote.

These projects are moving underground. Even Action française called on its “patriots” to put down roots. Several “nationalist farms” have already been created. The best known is called the Desouchière, in Mouron-sur-Yonne (Nièvre). Its members advocate a community life only among “whites”, “in the heart of the Morvan, in the old Celtic country, where a harsh race has always lived with tenacity and independence”. They had associated an Amap with his project [4] in the Dijon conurbation and offered an assortment of local products stamped with the coat of arms of Burgundy.

The return to the countryside is in the air of the times. Logan Alexandre Nisin, who has been in prison for four years after planning to carry out attacks with his OAS group, was also the treasurer of the France-Village association. The latter’s ambition was to buy a small village to ”save the white race”.

Ecofascism is therefore not a fantasy, it is already a reality. Tomorrow, Reporterre will look back at its historical origins and its recent conquest of minds, its porosity with certain ecologist circles and its possible alliance with the candidacy of Éric Zemmour.

Part 2: From the nineteenth century to Zemmour, ecofascism contaminates the political debate

The current rise of ecofascism stems from an ideological battle, which has been going on for decades, to impose its favorite themes and bring the far right closer to ecology. Within ecological and emancipatory circles, there is a tendency to minimize this groundswell and to see it as nothing more than a movement condemned to marginality. We would be wrong. The unprecedented confusion that reigns today could change the situation. “In the chiaroscuro monsters arise,” wrote Antonio Gramsci.

In this article, Reporterre looks back at three elements that invite us to take “the green-brown peril” seriously: its ideological corpus and its deep roots, its porosity with certain currents of political ecology and finally the candidacy of Éric Zemmour, who could succeed in bringing about the junction between the traditional fascist movement and its new components.

In the first place, it must be remembered that fascism[5] and ecology have often cultivated dangerous liaisons. “In history, ecology has not necessarily been synonymous with emancipation, it also contains within it the seeds of a profoundly reactionary way of thinking with the praise of a nature deemed immutable, birth control or the rejection of minorities,” historian Stéphane François told Reporterre.

“Ecofascism” is a phrase coined by Pentti Linkola, a Finnish writer who advocated deindustrialization, zero immigration, and population reduction to protect the planet. The author, who died in 2020, called democracy a “religion of death” and defended the implementation of authoritarian measures to maintain human life on Earth.

An ancient history

Ecofascist thought is the result of an ideological tinkering that finds its foundations as early as the nineteenth century. It takes up the analyses of the economist Thomas Malthus, who made overpopulation the main cause of the ecological problem. The latter advocated voluntary birth control, especially among the working classes, and the cessation of all aid to the needy to “avoid the premature end of the human species”.

Ecofascism also has its roots in the folklore of the völkisch movement in Germany, which mixed environmentalism and xenophobic nationalism. Two thinkers, Ernst Moritz Arndt and Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl, have nourished this imagination. As early as 1815, they spoke out against the short-sighted exploitation of forests and soils and, at the same time, flattered the racial purity of the Teutonic people, supposedly invaded by Jews and Slavs. Love of the land was then linked to anti-Semitism, and the mysticism of nature to ethnocentric populism.

Ernst Haeckel, the biologist who coined the word “ecology” in 1866, was himself a proponent of the völkish movement. “The roots of fascism go deep into the ecological thought of the nineteenth century,” explains historian Paul Guillibert in an article published in the journal Mouvements. At some point in history, these two currents — ecology and fascist ideology — became intertwined.

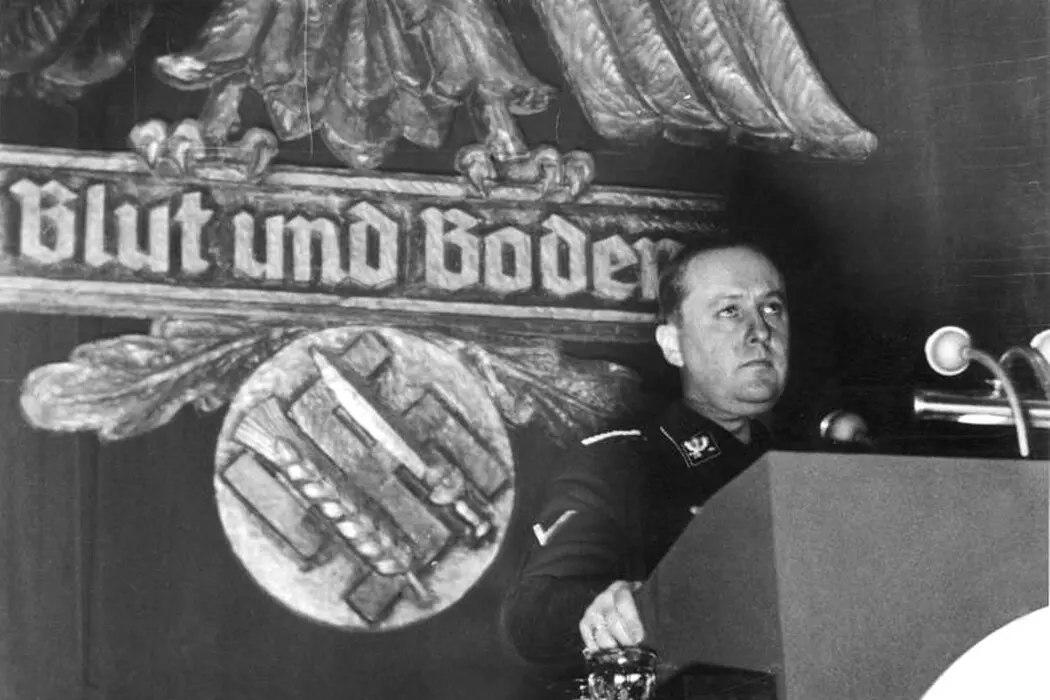

They also gave birth to the “green wing” of the Nazi Party. Composed mainly of Walther Darré, Fritz Todt, Alwin Seifert and Rudolf Hess, this ecologist faction obtained, before its eviction in 1942, many advances in environmental matters, including the creation of several thousand agroecological farms in Germany. Their ecology was historically linked to the idea of rootedness, they defended the Nazi slogan “Blut und Boden” (”blood and soil”), which aimed to define a racially homogeneous political community on a territory bounded by natural borders.

An ideology that is part of “the conquest of minds”

This form of ecology did not disappear with the end of Nazism, quite the contrary: some denazified cadres, such as Pastor Werner Georg Haverbeck and Renate Riemeck, a medievalist and former secretary of the SS Johann von Leers, promoted it again in the 1970s. At the same time, in France, a former SS man, Robert Dun (real name Maurice Martin), was one of the pioneers of this form of ecology. Similarly, in 1995, the anti-Semitic activist and survivor of collaboration with the Nazis, Henry Coston, published a libel entitled No! Ecology is not left-wing.

Ecofascist thought has found fertile ground since the 1980s, particularly in France. With the help of the New Right and the decisive ideologue Alain de Benoist. These currents have waged what they call “a metapolitical struggle,” an extra-parliamentary cultural struggle that sees ideological transformation as a precondition for political change.

Werner Georg Haverbeck (1909.10.28 — 1999.10.18)

1923年にNSDAPの青少年組織に参加している。 pic.twitter.com/xNuoDlwZBF— オスロート (@heinkel70) October 27, 2015

According to researcher Lise Benoist, contacted by Reporterre, “these metapoliticians claim to be ‘right-wing Gramscists’, they set out to conquer minds and fiercely oppose a cultural hegemony that they consider to be left-wing.” In forty years, these ideologues have gradually ploughed their furrow and have succeeded in imposing their obsession with identity, which they have linked to ecological issues, into the public debate. In particular, they introduced the theme of degrowth to the far right and built a new doctrine around the ecology of the border.

In his recent book The Great Confusion, the sociologist Philippe Corcuff believes that they have won the battle of ideas. They succeeded in “disintegrating previously stabilized political landmarks” and “developed discursive bridges between currents that could previously be considered antagonistic.”

A porosity with the more traditional currents of ecology

The historical depth and theoretical framework of ecofascism is one of the first reasons that can push us to worry. “It could lead to an ideological reconfiguration of fascism,” warns Antoine Dubiau, the host of the blog Perspectives printemps. The second particularly destabilizing element is to note that these ecofascist currents are not always as isolated as we think and not necessarily cut off from the currents of political ecology.

Here too, we can cite many examples. As the historian Stéphane François recounts in his book Les vert-bruns, some former Nazi cadres participated in the creation of the Grünen in Germany. In the United States, ecofascists have also infiltrated the bioregionalist movement. The far-right ideologue Alain de Benoist had ties to Edward “Teddy” Goldsmith, the founder of the British journal The Ecologist. One of the theorists of anti-speciesism, Maximiani Portas, better known as Savitri Devi, was both an ardent neo-Nazi and a radical environmental activist who inspired many hippies after the 1968s. The founder of the group Earth First!, Dave Foreman, is also a sulphurous personality: he believed that mass immigration was the major cause of ecological deterioration.

“A rooted ecology defends the local territory, the European heritage and the need for the heterosexual family nucleus”

France is not spared from these nauseating ties. People close to ecofascist currents can be found in Antoine Waechter’s Independent Ecologist Movement (MEI). This former presidential candidate defends an ecology that is neither right nor left and praises localism and terroirs, sometimes quoting former Vichy supporters such as Yann Fouéré. Members of the New Right have joined his party, such as the identity activist Laurent Ozon, who ran the magazine Le Recours aux forêts, or Fabien Niezgoda and the essayist François Bousquet, who directs the magazine Elements.

“They agree on a critique of globalized capitalism, the commodification of nature and the alienation of modern forms of life,” says researcher Lise Benoist. “It is a common basis for a rooted ecology, which defends the local territory, the European heritage and the need for the heterosexual family nucleus.”

In September 2020, the researcher, who works with Andreas Malm and the Zetkin Collective, was able to enter a far-right conference organized at the Maison de la Chimie in Paris and entitled “Nature as a base”. She described an incongruous event with stands where Alain de Benoist’s books rubbed shoulders with those of Pablo Servigne on collapse.

“The ecologists have a lot of ideological clarification work to do if they want to prevent certain far-right circles from reclaiming their battles,” says Antoine Dubiau, of the blog Perspectives printemps. “This is a threat to be taken very seriously. The way we talk about ecology today, nature or demography can sometimes be soluble in a fascistic conception. The loopholes through which these militants could rush must be closed to avoid any attempt to capture them.”

This perspective would require significant intellectual work to repoliticize and redefine the concepts specific to ecology. An observation shared by the philosopher Pierre Madelin in the journal Terrestres: “We are not sufficiently prepared to fight this criminal alliance between brown and green, neither conceptually nor politically.”

The alliance between carbofascism and ecofascism

However, there is an urgency. Éric Zemmour’s candidacy for the French presidency could reshuffle the cards. Obviously, the far-right polemicist has no use for ecology, as Reporterre has shown, but he carries around him a nebula close to survivalism.

Recently, Streetpress revealed how a far-right group, an active supporter of Éric Zemmour, was practicing shooting racist caricatures of Jews, Muslims and blacks in a forest in western France. The group called itself the “Gallican Family”. Composed of several dozen active members, it brings together a few hundred sympathizers. In their discussion circle, these members praise the terrorist Brenton Tarrant — the perpetrator of the attacks in Christchurch, New Zealand, in 2019 — who claimed to be eco-fascist and called for communitarianism.

“The only really salient element of their doctrine are the recurrent references to survivalism,” Mathieu Molard, the editor-in-chief of Streetpress, told Reporterre. “The Gallican Family, like many radical groups in France, claims to be part of this popular movement in the United States, whose followers train to survive and arm themselves in anticipation of a catastrophe or a collapse of our civilization.”

[EXTREME-RIGHT] Zemmour’s supporters shoot caricatures of Jews, Muslims and blacks

The investigation https://t.co/CaGhnwdr64

Subscribe to FAF, the StreetPress newsletter that deciphers the far right https://t.co/riDCLSnc4W pic.twitter.com/Qwkt1P7Bys

— StreetPress (@streetpress) November 2, 2021

An alliance could therefore emerge between these different survivalist or ecofascist groups and the movement around the candidacy of Éric Zemmour. This would not be completely unprecedented. In the United States, Donald Trump’s climate scepticism has not prevented some of his supporters from flirting with the proponents of ecofascism. For example, the author Mike Ma, who claims to be a non-nationalist, wrote for the ultranationalist website of former White House special adviser Steve Bannon. Donald Trump was also very close to John Tanton, a billionaire committed to both environmental protection and immigration, who before his death in 2019 led the Federation for American Immigration Reform. Many survivalists in the United States supported Donald Trump in the last election. Several of them are among those charged in the assault on the Capitol on January 6, 2021.

Press review — #JacobChansley, the “shaman” #QAnon of the Capitol, sentenced to more than 3 years in prison https://t.co/jeKdtWx4Kt | wnews pic.twitter.com/Aba6srRRGT

— PRESS REVIEW (@wnewspresse) November 17, 2021

In France, the question remains unresolved for the time being. The alliance is not yet effective, but calls for the utmost vigilance. As André Gorz already announced in the 1970s, “the great battle has begun. It will be their ecology or ours.”

[1] Fascism refers to an ideology, a movement and a historical political regime, that of Mussolini in Italy in the 1920s and 1930s. His doctrine combines the idea of the need for a leader, populism and nationalism. Its political system leads to a totalitarian society. The ecofascism we are talking about in this survey is not intended to become a political regime, it is for the moment only an ideology linking ecology to hatred of the other, it does not yet constitute a movement as such. But it could become so in the future, especially if it moves closer to the more traditional fascist currents.

[2] According to the Larousse, paganism is the “name given by the Christians of the first centuries to polytheism”. The neopagans have a younger history: “Neopaganism is said to have originated in the eighteenth and nineteenth-centuries in Europe. It comes from occultism or romanticism,” explains researcher Stéphane François, interviewed by TV5 Monde.

[3] He is the author of Demain, la décroissance — Penser l’écologie jusqu’au bout (Edite, 2007).

[4] Associations for the maintenance of peasant agriculture.

[5] Fascism refers to an ideology, a movement and a historical political regime, that of Mussolini in Italy in the 1920s and 1930s. His doctrine combines the idea of the need for a leader, populism and nationalism. Its political system leads to a totalitarian society. The ecofascism we are talking about in this survey is not intended to become a political regime, it is for the moment only an ideology linking ecology to hatred of the other, it does not yet constitute a movement as such. But it could become so in the future, especially if it moves closer to the more traditional fascist currents.