Ive Brissman, Paul Linjamaa, and Tao Thykier Makeeff

Handbook of Rituals in Contemporary Studies of Religion

Exploring Ritual Creativity in the Footsteps of Anne-christine Hornborg (Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion, 22)

06 Mar 2024

Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion

Anne-Christine Hornborg – Friend and Colleague

Bibliography of Professor Anne-Christine Hornborg

Articles in Popular Press and News Papers

Introduction: Ritual Creativity

Part 1: Ritual and Indigenous Religions

Part 2: Ritual, Ecology, and New Spiritualities

Part 3: Ritual and Body: Bodies as Rituals

Part 4: Regional Perspectives: Islam and African Christianity

Part 1: Ritual and Indigenous Religion

Chapter 1: Earthen Spirituality or Cultural Genocide?

3. Gary Snyder: Early Appropriation by an Elder of the Deep Ecology Movement

4. American Indian Spirituality in the Earth First! Movement

7. Dennis Martinez: Ambivalence, Culture Cops, and Hot Heads

10. Summary and Reflections on the Ethics of Appropriation

Chapter 2: The Return of Mi’kmaq to Living Tradition

3. Environmentalism and Conservation

4 From Sacred Ecology to Animism

6 Knowledge and Responsibility

7 Conclusion: Becoming Mi’kmaq

Chapter 3: Cosmologies of the Earth and Ether

4 Spirituality as Compensation for the Loss of Physical and Material Well-Being

5 The Enchantment and Disenchantment of Literacy

1. As I Stroll, I Wonder: Who Is We? Where Is Here?

Part 2: Ritual, Ecology, and New Spiritualities

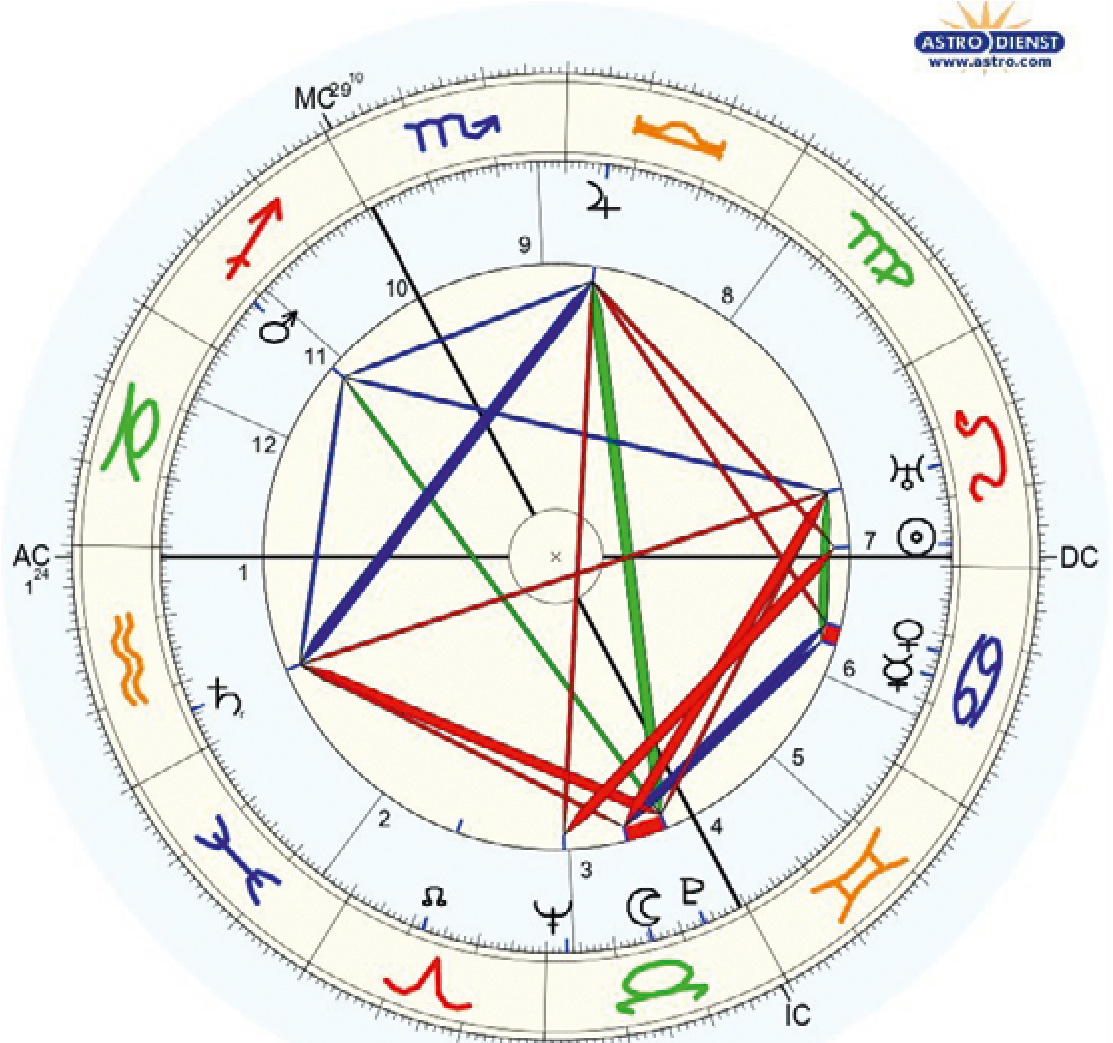

Chapter 6: Financial Astrology

2 Founding Myths and Historical Development of Financial Divination

3 Fundamentals of Astrological Symbolism

4 How to Astrologically “Read” the Stock Market

5 Divination and the Stock Market

Chapter 7: Manipulating the Sticks

2 The Yijing in European Esotericism

3 Aleister Crowley and the Yijing

4 Crowley’s Ritual of Yijing-Divination

Chapter 8: The Sounds of Silence

2 Interrituality: Ritual Creativity and Minor Ritual Acts

3 Minor Ritual Acts of Silence

4 Forming Circles of Silence and Sharing

5 Approaching in Silence: Visiting Wistman’s Wood

7 Silence and Deep Listening – beyond the Realm of Words

8 Rebuilding Quiet Places – Silence and Ecological Awareness

Chapter 9: Durga Is Also Living in Sweden

2 Ritual Competence and Performance

3 Durga Puja as a Social Arena for Bengalis

4 The Multiple Functions of Puja Committees

8 A ‘Celebration’ Set Apart from Everyday Life

Part 3: Ritual and Body: Bodies as Rituals

Chapter 10: Ritual Dance from a Philosophical Perspective

2 Dance, Rituals, and Embodiment

3 The Problem of Philosophical Dualism and Mentalism

4 The Study of Religion and Embodiment

6 Mirror Neurons, Abstract Religious Concepts and the Transformative Power of Ritual

Chapter 11: Transformation beyond the Threshold

2 Undergoing the Neophyte Ritual of Initiation

3 Crossing the Threshold of Liminality

4 In a New Light: Self-Reflexive Reiteration

5 Bringing Others to the Threshold: Re-Experiencing Ritual

6 Reiteration: the ‘Slow Fermentation’ of the Initiatory Process

Chapter 12: Bringing Embodiment Back to Antiquity

2 Introducing Valentinus Fragment 1

3 The Meaning of parrhésia in Antiquity

4 Revisiting Valentinus’ Fragment 1

Chapter 13: “Man Who Catch Fly with Chopstick, Accomplish Anything”

5 Martial Arts, Personal Growth, and Excellence

7 “Anything Is Possible When You Have Inner Peace”

Part 4: Rituals in Regional Perspectives: African Christianity and Islam

Chapter 14: Al-ṣalāt: the Ritual of Rituals in Islam

4 Purifying the Body and al-ṣalāt

9 The Power of al-ṣalāt: Some Sort of Conclusion

Chapter 15: Ritual Fields and Participation in the Alevi Festival in Hacıbektaş

2 The Hacıbektaş Festival and Its Importance for Alevi Communities

3 The Study of the Hacıbektaş Festival

4 The Ritual Fields of the Hacıbektaş Festival

4.1 Ritual Field 1: Pilgrimage and Saint Veneration

4.2 Ritual Field 2: Celebrations of Alevi Culture

4.3 Ritual Field 3: Ceremonies of Recognition and Politics

Chapter 16: Who Got the Rite Wrong? The Mavuno Alternative Christmas Service and Charismatic Ritual

2 Negotiation, Innovation, and Disruption in the Field of Rituals

3 The Alternative Christmas Service

4 Widening the Frame – Negotiating Charismatic Liturgy through Music

5 Creating Space for Forbidden Feelings – Negotiating Life beyond the Ritual Frame

Chapter 17: A Ritual That Turned the World Upside Down

2 A Paradigmatic African Instituted Church

3 On the Curse of Ham and Its Uses

4 Black Race as the Sinful Race

6 Annulment of Ham’s Curse as Subversion of Colonial Hierarchies

Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion

Series Editors

Terhi Utriainen (University of Turku, Finland)

Benjamin E. Zeller (Lake Forest College, USA)

Editorial Board

Olav Hammer (University of Southern Denmark)

Charlotte Hardman (University of Durham)

Titus Hjelm (University College London)

Adam Possamai (University of Western Sydney) Inken Prohl (University of Heidelberg)

volume 22

The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bhcr

[Title Page]

Handbook of Rituals in Contemporary Studies of Religion

Exploring Ritual Creativity in the Footsteps of

Anne-Christine Hornborg

Edited by

Ive Brissman

Paul Linjamaa

Tao Thykier Makeeff

LEIDEN | BOSTON

[Copyright]

This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder.

Open access publication of this book has been made possible by Lunds universitetsbibliotekens bokfond.

The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at https://catalog.loc.gov

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2024004331

Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill-typeface.

issn 1874–6691 isbn 978-90-04-54292-1 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-69220-6 (e-book) DOI 10.1163/9789004692206

Copyright 2024 by Ive Brissman, Paul Linjamaa and Tao Thykier Makeeff. Published by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands.

Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Schöningh, Brill Fink, Brill mentis, Brill Wageningen Academic, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Böhlau and V&R unipress.

Koninklijke Brill NV reserves the right to protect this publication against unauthorized use.

This book is printed on acid-free paper and produced in a sustainable manner.

Contents

Anne-Christine Hornborg – Friend and Colleague

Olle Qvarnström

Bibliography of Professor Anne-Christine Hornborg

Introduction: Ritual Creativity

Ive Brissman, Paul Linjamaa and Tao Thykier Makeeff

Part 1

Ritual and Indigenous Religion

1. Earthen Spirituality or Cultural Genocide? Radical Environmentalism’s Appropriation of Native American Spirituality

Bron Taylor

2. The Return of Mi’kmaq to Living Tradition

Graham Harvey

3. Cosmologies of the Earth and Ether Spirituality and Sociality among the Mi’kmaq, Warlpiri and Māori

Michael Jackson

4. Subsumed Rituals

The Intrinsic Implications of Divination and Powerful Things among the Eastern Penan of Malaysian Borneo

Mikael Rothstein

5. Where Is Here?

Ronald L. Grimes

Part 2

Ritual, Ecology, and New Spiritualities

6. Financial Astrology

Taking Divination into the Heart of Capitalist Economy

Olav Hammer

7. Manipulating the Sticks

Reconstructing Aleister Crowley’s Use of Yijing Divination

Johan Nilsson

8. The Sounds of Silence

A Study of Minor Ritual Acts of Silence in Dark Green Spirituality 148 Ive Brissman

9. Durga Is Also Living in Sweden

Celebrating a Hindu Festival in a Secular Setting 167 Göran Ståhle

Part 3

Ritual and Body: Bodies as Rituals

10. Ritual Dance from a Philosophical Perspective 179 Erica Appelros 11. Transformation beyond the Threshold

The Reiterative Practice of Initiation in the Contemporary Initiatory Society Sodalitas Rosae Crucis (S.R.C.)

Olivia Cejvan

12. Bringing Embodiment Back to Antiquity

*Manifesting Enlightenment through the Body in Valentinus’ Writings

Paul Linjamaa

13. “Man Who Catch Fly with Chopstick, Accomplish Anything”

Ritualised Bodily Learning and the Pursuit of Excellence in the Martial Arts

Tao Thykier Makeeff

Part 4

Rituals in Regional Perspectives: African Christianity and Islam

14. Al-ṣalāt: the Ritual of Rituals in Islam 241 Jonas Otterbeck

15. Ritual Fields and Participation in the Alevi Festival in Hacıbektaş 256 Hege Markussen

-

Who Got the Rite Wrong? The Mavuno Alternative Christmas Service and Charismatic Ritual 271 Martina Björkander

-

A Ritual That Turned the World Upside Down

The Kimbanguist Annulment of Ham’s Curse 291

Mika Vähäkangas

Index 306

Anne-Christine Hornborg – Friend and Colleague

When I was master of Fogelvik, I was indeed both happy and rich. But when made king of the Swedish land, I was a poor and unhappy man.

This short poem is attributed to the fifteenth century king Karl Knutsson Bonde, who apparently never forgot his happy youth as a seaside farmer and owner of Fågelvik Manor in the beautiful archipelago of Tjust.

It is Anne-Christine Hornborg’s great fortune that although she also was a seaside farmer, she was not fated to be drawn away from her beloved farm like her former royal neighbour. Indeed, throughout her life she has enjoyed many memorable times as both a happily married farmer living by the sea in Yxnevik (not far from Fågelvik) and as a committed academic deeply involved in important environmental, educational, and societal issues. The fresh sea breezes and dark fertile soil of her homeland enriched Anne-Christine’s life, leading to a lifelong commitment to the environment and a profound interest in indigenous peoples’ perceptions of nature.

I first met Anne-Christine Hornborg at Lund University, when she was an undergraduate and I was a doctoral candidate. Years later, after we both had become professors in the religion department, her primary focus was on anthropological perspectives and mine was on philological and historical issues. Anne-Christine was a skilled and popular pedagogue and a highly successful researcher, always open to new ideas and interdisciplinary perspectives. She had the ability to deal with difficult contemporaneous problems and the knowledge to identify their origins and relate them to the broader intellectual concerns of modern culture.

I hold dear an unforgettable memory of a weekend spent with Anne-Christine and her family at their home in Yxnevik. It was a lovely summer’s day in July 2014. After a delightful meal, enriched by pleasant meaningful conversation, I sat with Anne-Christine, her husband Alf, and their two children Christoffer and Sara on the wooden deck of their home, overlooking the sea. Sitting there in that moment I realised how the two diverse aspects of Anne-Christine’s life had complemented each other to create a meaningful, well-rounded existence.

Olle Qvarnström

Centre for Theology and Religious Studies

Lund University

Bibliography of Professor Anne-Christine Hornborg

Monographs

2012. Coaching och lekmannaterapi: en modern väckelse. Stockholm: Dialogos Förlag.

2008. Mi’kmaq Landscapes: From Animism to Sacred Ecology. Vitality of Indigenous Religions. London: Ashgate, reprinted Abingdon: Routledge 2016.

2007. Cowritten with Erica Appelros and Helena Röcklinsberg, Din tro eller min? Religionskunskap för gymnasieskolan 2. Stockholm: Natur och kultur.

2007. Cowritten with Erica Appelros and Helena Röcklinsberg, Din tro eller min? Religionskunskap för gymnasieskolan 1. Stockholm: Natur och kultur.

2005. Ritualer: teorier och tillämpning. Stockholm: Studentlitteratur AB.

2001. A Landscape of Left-Overs: Changing Conceptions of Place and Environment among Mi’kmaq Indians of Eastern Canada. Dissertation, Lund University Studies in History of Religions 14.

Editorship

2013. Guest editor for Svensk Teologisk Kvartalskrift 89, “Riternas förändring i det moderns Sverige.”

2010. Den rituella människan: flervetenskapliga perspektiv, Linköping University Electronic Press.

Book Chapters

2021. “Rebranding the soul: Rituals for the well-made man in market society.” In J. Cornelio, F. Gauthier, T. Martikainen, and L. Woodhead, eds., Routledge International Handbook of Religion in Global Society. New York and London: Routledge, 52–62.

2021. “Designing Enchanted Rituals for Modern Man.” In P.J. Stewart and A.J. Strathern, eds., The Palgrave Handbook of Anthropological Ritual Studies. London: Palgrave, 255–274.

2018. “Religion inifrån och utifrån: Perspektiv på autenticitet och andlighet i fält.” In D. Enstedt and K. Plank, eds., Levd religion: Det heliga i vardagen. Stockholm: Nordic Academic Press, 60–78.

2017. “Jag är mi’kmaq och det jag gör är min kultur!” In E. Hall and B. Liljefors Persson, eds., Ursprungsfolkens religioner – perspektiv på kontinuitet och förändring. Föreningen lärare i religionskunskap, 93–107.

2016. “Objects as Subjects: Agency, and Performativity in Rituals.” In M. Broo, T. Hovi, P. Ingman, and T. Utriainen, eds., The Relational Dynamics of Enchantment and Sacralization: Changing the Terms of the Religion vs Science Debate. Bristol, CT: Equinox, 27–45.

2015. “Skolcoaching: en historisk möjlighet eller dagslända?” In H.A. Larsson, ed., Det historiska perspektive 2–3. Högskolan för lärande och kommunikation. Jönköping: Samhällsstudier och didaktik, 11–30.

2014. “Hitta dina inre resurser: mindfulness som kommersiell produkt.” In K. Plank, ed., Mindfulness: Tradition, tolkning och tillämpning. Lund: Nordic Academic Press, 177–202.

2014. “Att få flow i livet: mind-body-terapin och coaching som nya helandemetoder.” In J. Moberg and G. Ståhle, eds., Helig Hälsa. Helandemetoder i ett mångreligiöst Sverige. Stockholm: Dialogos, 145–166.

2013. “ ‘Healing or Dealing?’ Neospiritual therapies and coaching as individual meaning and social discipline in late modern Swedish society.” In F. Gauthier and T. Martikainen, eds., Religion in Consumer Society: Brands, Consumers and Markets. Farnham: Ashgate, 189–206.

2013. “Det är ett sätt att leva från den dag du föds: om andlighet och reservatsliv hos kanadensiska mi’kmaqindianer.” In S. Sorgenfrei, ed., Mystik och andlighet: kritiska perspektiv. Stockholm: Dialogos, 141–157.

2012. “Are you content with being just ordinary? Or do you wish to make progress and be outstanding?” In Tore Ahlbäck and Björn Dahla, eds., New ritual practices in contemporary Sweden: Post-secular religious practices. Scripta Instituti Donneriani Aboensis 24. Åbo: Donner Institute for Research in Religious and Cultural History, 111–127.

2012. “Making a Garden Out of the Wilderness: Contested Ideas of Landscape, Dwelling and Personhood in the Encounter Between European Settlers and the Mi’kmaq in ‘New France’.” In L. Feldt, ed., Wilderness in Mythology and Religion: Approaching Religious Spatialities, Cosmologies, and Ideas of Wild Nature. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 205–228.

2011. “Designing Rites to Reenchant Secularized Society: Cases from Contemporary Sweden.” In U.G. Simon, C. Brosius, A. Michaels, P.H. Rösch, and G. Ahn, eds., Reflexivity, Media, Design and Visuality. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Publishing House, 671–691.

2010. “Ritualer.” In J. Svensson and S. Arvidsson, eds., Människor och makter 2: En introduktion till Religionsvetenskapen. Linköping: Lindköpings universitet, 104–119.

2010. “Ritual Studies och ett flervetenskapligt sätt att studera ritualer.” In A.-C. Hornborg, ed., Den rituella människan: flervetenskapliga perspektiv. Linköping University Electronic Press, 11–23.

2010. “Marknadsföring av natur och hälsa: Om rituellt helande i det senmoderna Sverige.” In A.-C. Hornborg, ed., Den rituella människan – flervetenskapliga perspektiv. Linköping University Electronic Press, 151–169.

2010. “Cultural Trauma, Ritual and Healing.” In G. Collste, ed., Studier i tillämpad etik 12: Identity and Pluralism: Ethnicity, Religion and Values. Linköping University Electronic Press, 104–109.

2010. “Inledning: Ritual Studies som ett flervetenskapligt sätt att studera ritualer.” In A.-C. Hornborg, ed., Den rituella människan: flervetenskapliga perspektiv. Linköping University Electronic Press, 11–23.

2009. “Selling Nature, Selling Health: The Commodification of Ritual Healing in Late Modern Sweden.” In S. Bergman and Y.-B. Kim, eds., Religion, Ecology & Gender: East-West Perspectives. Studies in Religion and the Environment 1. Münster: LIT Verlag, 109–129.

2009. “Praxis Dialogue: Catholic Rituals in Native American Contexts.” In C. Stenqvist, P. Fridlund, and L. Kaennel, eds., Plural Voices: Intradisciplinary Perspectives on Interreligious Issues. Leuven: Peeters Publishers, 37–54.

2009. Co-written with Heather Eaton, “Ritual Time and Space: A Liminal Age and Religious Consciousness.” In S. Bergman and Y.-B. Kim, eds., Religion, Ecology & Gender: East-West Perspectives. Studies in Religion and the Environment 1. Münster: LIT Verlag, 79–89.

2009. “Owners of the Past: Readbacks or Tradition in Mi’kmaq Narratives.” In S. Wilmer, ed., Native American Performance and Representation. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 61–77.

2007. “Rites for Modern Man: New Practices in Sweden.” In L. Midholm, A. Nordström, and M.T. Agozzino, eds., The Ritual Year and Ritual Diversity: Proceedings of the Second International Conference of the SIEF Working Group on the Ritual Year, Gothenburg June 7–11, 2006. Gothenburg: Institute for Language and Folklore, 83–92.

2000. “Djävulsdyrkare, trollkarl eller schaman: det europeiska mötet med buoin hos kanadensiska mi’kmaqindianer.” In T.P. Larsson, ed., Schamaner: essäer om religiösa mästare. Stockholm: Bokförlaget Nya Doxa, 159–180.

1998. “Handel och mission hos kanadensiska mi’kmaqindianer under 1600-talet.” David Westerlund, ed., Religioner i norr: Svensk religionshistorisk årsskrift 7. Göteborg: Svenska samfundet för religionshistorisk forskning, 218–232.

Peer-Reviewed Articles

2018. “Leder religionsantropologins utmaningar och forskningsproblematik till nostalgiska elegier och idylliska tankar om ädla vildar?” Religionsvidenskabeligt tidsskrift. 68, 91–101.

2017. “Interrituality as the Mean to Perform the Art of Building New Rituals.” Journal of Ritual Studies. 31:2, 17–27.

2016. “Förtrollande riter i det offentliga rummet: hur designas den lyckade individen.” Chaos: Skandinaviske tidsskrift for religionshistoriske studier. 65:1, 23–51.

2016. Cowritten with Maria Wemrell, Juan Merlo and Shai Mulinari, “Contemporary Epidemiology: A Review of Critical Discussions Within the Discipline and a Call For Further Dialogue with Social Theory.” Sociology Compass. 10:1, 153–171.

2015. “Ondska hos mi’kmaq: ett kulturellt och historiskt färgat begrepp.” Dīn: tidsskrift for religion og kultur. 1, 13–37.

2015. “Mannen som gifte sig med en bäver: ett omöjligt äktenskap?” Chaos: Skandinavisk tidsskrift for religionshistoriske studier. 63, 7–19.

2015. “Skolcoaching: en möjlighet eller dagslända?” Aktuellt om Historia. 2–3, 11–30.

2013. “Inledning: Riternas förändring i det moderna Sverige.” Svensk Teologisk Kvartalskrift. 89, 49–53.

2012. “Secular Spirituality in Contemporary Sweden.” Swedish Missiological Themes. 100:3, 303–321.

2012. “Are We All Spiritual? A Comparative Perspective on the Appropriation of a New Concept of Spirituality.” Journal for the Study of Spirituality. 1:2, 247–266.

2012. “Designing Rites to re-enchant secularized society: new varieties of spiritualized therapy in contemporary Sweden.” Journal of Religion and Health. 51:2, 402–418.

2012. “Secular Spirituality in Contemporary Sweden.” Swedish Missiological Themes. 100:3, 303–321.

2010. “Designing Rites to Reenchant Secularized Society: New Varieties of Spiritualized Therapy in Contemporary Sweden.” Journal of Religion and Health. 51:2, 402–418.

2010. “I coachningland: på spaning efter den inre potentialen.” Chaos: Skandinavisk tidsskrift for Religionshistoriske studier. 53:1, 1–16.

2010. “Designing Rites to Reenchant Secularized Society: New Varieties of Spiritualized Therapy in Contemporary Sweden.” Journal of Religion and Health. May.

2009. “Lokala livsvärldar och texternas konstruktioner: om ‘indianens’ natursyn.” Religion och Livsfrågor. 3, 18–20.

2008. “Protecting Earth? Rappaport’s vision of rituals as environmental practices.” Journal of Human Ecology. 24:4, 275–283.

2007. “Att återförtrolla det sekulariserade samhället: är Sverige på väg in i Vattumannens tidsålder?” Svensk religionshistorisk årsskrift. 33–59.

2007. “ ‘I’m Inca’: The Fiesta of Mamacha Carmen in the Andean village of Pisac.” Journal of Ritual Studies. 21:2, 46–56.

2007. “Riter för ‘Det Högre Självet’: Nyandlighet som terapi i det senmoderna Sverige.” Finsk Tidskrift: Kultur – ekonomi – politik. 5, 254–270.

2006. “ ‘Människa, varför har Ni valt det här yrket?’: Ledarskap och praktik i nya riter.” Svensk Teologisk Kvartalskrift. 82, 110–122.

2006. “Nya rituella sammanhang i senmodernitetens Sverige.” Tvärsnitt – om humanistisk och samhällsvetenskaplig forskning. 3, 20–23.

2006. “Visiting the Six Worlds: Shamanistic Journeys in Canadian Mi’kmaq Cosmology.” Journal of American Folklore. 119, 312–336.

2005. “Eloquent Bodies: Rituals in the Context of Alleviating Suffering.” Numen. 52, 356–394.

2005. “Talande kroppar. Ritual och återupprättelse.” Chaos: Skandinavisk tidsskrift for religionhistoriske studier. 44, 113–141.

2004. “Cosmology, Ethics and the ‘Biocentric Indian’.” Acta Americana. 12:29–48.

2004. “Différentes perceptions du paysage: changement et continuité chez les Micmacs.” Recherches amerindiennes au Quebec. 34, 45–57.

2004. “Ritual Practice as Power Play or Redemptive Hegemony: The Mi’kmaq Appropriation of Catholicism.” Swedish Missiological Themes. 92, 169–193.

2003. “Being in the Field: Reflections on a Mi’kmaq Kekunit Ceremony.” Anthropology and Humanism. 28, 1–13.

2002. “ ‘Readbacks’ or Tradition? The Kluskap Stories Among Modern Canadian Mi’kmaq.” European Review of Native American Studies. 16, 9–16.

2002. “St Anne’s Day: A Time to ‘Turn Home’ for the Canadian Mi’kmaq Indians.” International Review of Mission. XCI, 237–255.

2001. “Kluskap: As Local Culture Hero and Global Green Warrior: Different Narrative Contexts for the Canadian Mi’kmaq Culture Hero.” Acta Americana. 9, 7–38.

Reports

2016. Cowritten with M. Wemrell, J. Merlo, and S. Mulinari. Användning av alternativ och komplementär medicin (AKM) i Skåne: Pilotstudie. Lund University.

Reviews

2020. “Daniel Andersson, Ursprungsfolkens religioner: Land, minne, kultur.” Chaos: Skandinavisk tidsskrift for religionhistoriske studier. 74:2, 174–176.

2020. “Mikael Rothstein, Naesehornsfuglen skriger: hovedjagt og kraniekult.” Chaos: Skandinavisk tidsskrift for religionhistoriske studier. 74:2, 165–168.

2017. “Mikael Rothstein, Regnskovens religion – forestillinger og ritualer blandt Borneos sidste jægersamlere.” Chaos: Skandinavisk tidsskrift for religionhistoriske studier. 65:2, 179–181.

2017. “Mikael Rothstein, Regnskovens religion – forestillinger og ritualer blandt Borneos sidste jægersamlere.” Hunter Gatherer Research. 2:4, 483–486.

2014. “Jennifer Reid, Finding Kluskap: A Journey into Mi’kmaw Myth.” Anthropos: International Review of Anthropology and Linguistics. 109, 736–737.

2013. “Anne Kalvig, Åndeleg helse – Ein kulturanalytisk studie av menneske- og livssyn hos alternative terapeutar. Avhandling for graden philosophiae doctor, Universitetet i Bergen 2011.” Skandinavisk tidsskrift for religionhistoriske studier.

Articles in Popular Press and News Papers

2019. “Doing the rite thing.” Svensk Teologisk Kvartalskrift. 4, 223–236.

2019. “Framtidens begravningar: Varför överger svenskarna de traditionella kyrkliga liturgierna?” Signum: Katolsk orientering om kyrka, kultur, samhälle. 45, 30–35.

2019. “Funerals of the future?: Sweden Sees Sharp Rise in Burials Without Ceremony.” The Conversation. August.

2016. “Förödmjukande att tvingas gå kurserna.” Svenska Dagbladet. January.

2014. “Snabba lösningar till pånyttfödelse.” Lund University Research Magazine.

2013. “På spaning efter den inre potentialen.” RIT, Religionsvetenskaplig internettidskrift. 1.

2012. Cowritten with Hans Albin Larsson, “Läxhjälp ett hån mot lärarnas kompetens.” Svenska Dagbladet. December.

2012. “Coaching har blivit vår tids väckelse.” Svenska Dagbladet. May.

2011. Cowritten with Hans Albin Larsson, “Oseriöst att kommunala skolan hyr in coacher.” Aftonbladet. May.

2011. Cowritten with Hans Albin Larsson, “Skattepengar ska inte gå till studiecoacher.” Aftonbladet. May.

2009. “Terapi mot arbetslösheten?” Aftonbladet. February.

2009. “Arbetslösa erbjuds kosmisk energi.” Aftonbladet. February.

2007. “Utnyttja inte människors längtan.” Svenska Dagbladet. March.

2007. “Riter för den moderna människan.” Budbäraren 7. March.

2007. “I mörker är alla terapeuter gråa.” Svenska Dagbladet. February.

2007. “Självkännedom kostar.” Sydsvenskan. February.

Introduction: Ritual Creativity{1}

This book brings together leading international scholars of religion from a variety of disciplines with the aim of casting light on the topic of ritual studies within contemporary studies of religion. The contemporary studies of religion consist of an array of interconnected fields and the present volume explores the role played by rituals in the following emergent areas: new spiritualities and ecology, religion and embodiment, and indigenous religions. In addition, the volume offers a selection of regional perspectives on ritual studies from African Christianity and Islam which includes contemporary negotiations of identity and coloniality. The collected volume offers a combination of significant theoretical and methodological discussions as well as previously understudied topics in the contemporary studies of religion.

The book addresses readers from a wide range of disciplines. It will be of interest to and relevance for both students and researchers within the larger fields of ritual and religious studies, as well as anthropology and environmental humanities. The volume is not only a broad exploration of the importance of ritual in the contemporary studies of religion but also a way to honour a fellow scholar whose academic pursuits during her thirty-year career illustrate the interconnectedness and value of cross-pollination between several disciplines.

The work of Professor Anne-Christine Hornborg embodies the innovative and fruitful ways in which ritual perspectives can be applied to a broader context within the contemporary study of religions. In 2001 Professor Hornborg published the well-received study A Landscape of Left-Overs (2001) based on fieldwork among Nova Scotia’s first nation Mi’kmaq. Since then, Professor Hornborg has published many important contributions in ritual studies based on her other fieldwork in locations such as Tonga and Peru. These insights have been disseminated in a number of ways within the study of contemporary religion, demonstrating the persistence of ritual and religion in our own secular and consumerist societies. The chapters in the present volume are all inspired by the work of Professor Hornborg, in particular, the methodological and theoretical contributions she has offered throughout her long career. Some chapters revisit the contexts in which Professor Hornborg carried out long periods of fieldwork.

This book takes as its point of departure the great potential which we, the editors and contributors, believe is found in interdisciplinary approaches, and to which Professor Hornborg’s career is a testament. Professor Hornborg’s contributions to the study of rituals showcases the importance of ritual perspectives for the relatively young field of the study of contemporary religions. Similarly, her career reflects the development and broadened area of application which the subject of ritual studies has gone through. At the outset, ritual studies grew out of the field of anthropology. In many ways it was a tool used and applied to make sense of “other” cultures, most notably those of indigenous peoples. Today, the shoe is very much on the other foot, and Professor Hornborg is one of those important scholars who put it there, by using the insights she gained from diligent and rigorous study of the “other” to in effect cast light on the hidden power relations in the implicit polarisation of academic othering, and the potential found in also pointing the gaze inwards, rather than only outwards.

Since Catherine Bell’s new paradigm in ritual studies turned attention to the social construction of rituals (Bell 1997) many scholars have developed this approach to rituals and ritualisation. One of them is Professor Hornborg, who in a number of works brought ritual studies further. Rather than being just a pattern of repetition in accord with liturgy or tradition, it is more often the case that rituals, or rather those who do rituals and ritualisation, demonstrate high degrees of creativity.

Shifting the analytical question from how rituals are performed to how they are constructed turns our attention from tradition and repetition to creativity and innovation. In her work on the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia, Canada, Hornborg offers an illuminating example of ritual creativity where ritual is related to environmental activism and struggle. Here the Mi’kmaq performed their powwow ritual on the mountain they tried to save from mining companies, and their rituals became a way to mediate a sacred meaning in a secular struggle. Their ritual creativity was an inspired response to the needs of the contemporary world and drew from folk tradition, but in innovative and creative ways that combined existing elements into new rituals. In her research Hornborg addresses this ritual creativity and ingenuity with the introduction of the term ‘interrituality’ which she defines as “borrowing minor ritual acts or elements including objects found in other rituals” (Hornborg 2017: 17). Hornborg elaborates on how such minor ritual acts become important building blocks in new rituals. As Hornborg notes, doing the “rite thing” is not just to do the right thing: improvisation and innovations prove that rituals are flexible for the need of a certain occasion.

Just as Professor Hornborg was inspired by Bell and other great scholars of ritual (some of whom have been kind enough to contribute to the present volume), we, the editors, have found great inspiration in Professor Hornborg’s work, as well as in her scholarly support and guidance. Similarly, it is our hope that the present volume will inspire others to continue to develop the study of rituals in new creative ways. The overall aim of this handbook is to show the significance of employing eclectic methodologies, innovative theoretical perspectives, and constantly seeking out fresh types of data. We hope that the texts contained in this handbook will be of use in this respect, to both scholars and students from a wide range of backgrounds. By offering new examples of ritual innovation, and illustrating a wide variety of scholarly ingenuity when it comes to finding new fields for exploring creativity in rituals and ritualisations, it is our aspiration that more researchers will be inspired by Hornborg’s work, and that they will take ritual studies into new exciting areas. By providing a chamber of resonance for a multiplicity of voices – just as Professor Hornborg has done as a teacher, supervisor, and scholar – this handbook is designed to help others discover voices of their own. Our ambition is to reach beyond performative perspectives, and approach ritual creativity, in a more flexible way, characterised by sensitivity toward the special cases studied. Therefore, rather than seeing performance as repetition we will pay attention to improvisation and play.

How can we understand such a complex phenomenon as ritual? One way to approach ritual is to see it as a shapeshifter, much like music. The following quote is sometimes attributed to the musician Duke Ellington: “the music situation today has reached the point where it isn’t necessary for categories. I think what people hear in music is either agreeable to the ear or not. And if this is so, if music is agreeable to my ear, why does it have to have a category? It either sounds good or it doesn’t.”[1] Ellington points out an important aspect of the problem of defining and categorising elusive, and often emotionally vested cultural practices: our understanding of them, and hence our attempts to separate them into categories, is based on idiosyncratic perceptions. In this sense, ritual is like music. Not only the definition of genres of music, or of which music is “good” or not, changes, but the very definition of what constitutes music changes from person to person and from decade to decade. This becomes even more evident at the fringes, and while most people alive today might agree, that the Beatles played music, not all would use the word “music” to describe the sounds produced by Karlheinz Stockhausen, the metal band Cannibal Corpse, or the rapper Hopsin. It is also important to remember that although the idiosyncratic sensibilities of the few may become those of the many, this is also subject to change over time. When the Beatles first broke through, they were described by one critic as “so appallingly unmusical, so dogmatically insensitive to the magic of the art that they qualify as crowned heads of anti-music” (Buckley 1964).

Like music, what is referred to as rituals and ritualised behaviour is part of a mode of human (and non-human) practice that is in constant flux. It is polysemous, creative, ever changing, developing in relation to contextual needs. However, it is also the subject of theoretical sensibilities and battles over definition, which are affected by the gaze scholars cast on potential data, as well as the nets they cast to collect these data. In turn, the selection of data also affects the outcome of debates over definitions and theoretical approaches. Although we do not aim to put an end to the idea of ‘schools of thought’, we believe that it is important to keep in mind that if one is too invested in a specific school of thought or a system of analysis, the risk is that the data is not given a voice of its own. It is our aspiration that this book will invite both scholars and students to look with fresh eyes at ways of defining, analysing, and in general talking and writing about the phenomena and behaviours we call rituals and ritualisations, which may have attained some degree of canonicity, and that they will approach them in new, creative, and curious ways.

Rituals and ritualisations are not just something out there or back then but something here and now as well. We believe that the earlier scholarly attraction to systemic or even mechanistic perspectives in which rituals follow rules and produce meaning is suitably complemented by more organic and less ordered perspectives. To say that this implicates a shift from a Harmonic to an Eridian perspective would perhaps be overstating the case. However, we believe that the time is ripe for a more organic approach to the study of rituals and ritualisations, as well as to the study of their social, historical, and biological contexts. We suggest a shift from the genitive to the accusative: The idea that rituals and ritualisations contain or produce meaning places these as the loci of action, instead of focussing on the humans (or other animals) who do rituals or ritualisations. Rather, we suggest, that meaning is vested in rituals and ritualisation, or interpreted from these, in a wide variety of unpredictable ways. Rituals are malleable and polysemous. Claude Debussy supposedly described music as the space between the notes. It might be fruitful to think of rituals and ritualisations in similar ways.

Outline and Content

The present volume consists of seventeen chapters divided into four parts. As stated above, the objective is to contribute to and further new perspectives in ritual studies in the context of the contemporary study of religions.

The four different parts cover explorations into indigenous religions – a field which changed the study of rituals and demonstrated its importance for not only religious studies, but for anthropology and ethnography; ecology and new spiritualities, a relatively young but quickly expanding field which showcases the continued importance of ritual perspectives; the bodily aspect of rituals, explorations which all take their departure from the idea that rituals are like humans, and humans are like rituals – embodied; the fourth and final part of the book presents case studies from the two religions which statistically viewed have the most adherents globally, Islam and Christianity. Nevertheless, the four studies presented in Part 4 approach these ‘world’ religions from very different perspectives and contexts, demonstrating the dynamic nature of religions and the limitations of vast categories, through regional in-depth studies.

Part 1: Ritual and Indigenous Religions

Part 1 brings together several of the leading scholars in ritual studies and explores the topic of indigenous religions. The study of ritual is intimately connected with explorations of the contexts of indigenous peoples. In one way, the field of ritual studies can be said to have grown out of early studies of the religion of indigenous peoples. Seminal works in the bourgeoning field of anthropology of religion placed the importance of rituals at the fore. Pioneers like Bronislaw Malinowski and E.E. Evans-Pritchard – who emphasised the importance of fieldwork – paved the way for a new generation of scholars who would develop the field of ritual studies, such as Victor Turner and Ronald Grimes, the latter of whom is showcased in the present volume. The more distant and unknown the people, the more the rituals seem to stand out as a way into new worlds of meaning making.

Ritual studies developed during a time when indigenous religions were still termed as primitive or tribal religion. As such, the religions of indigenous peoples were framed as less developed or unsophisticated examples of religious phenomena, in contrast with Abrahamitic religions and the other two ‘world religions’, Buddhism and Hinduism. Much has been done in the field of religious studies since these categorisations were employed without much reflection. As Graham Harvey – featured in the present volume – has clarified, these paradigms reflect westernised structures based on Protestant enlightenment ideas (Harvey 2000: 1–19).

The first part of the present study covers the explorations of ritual aspects of several indigenous peoples, expanding on different relations to place and landscape; animism and ancestral religion; colonial perspectives, as well as issues relating to relocation and the relation between identity and land. These are all central themes that have become guiding in the study of indigeneity. In the first chapter of Part 1, “Earthen Spirituality or Cultural Genocide?,” Bron Taylor explores the way Native American spirituality has been appropriated by radical environmentalists. He identifies the way in which aspects of the appropriation of Native American spirituality threaten to contribute to the decline of Native American cultural integrity and survival, particularly regarding smaller Native nations. However, appropriation does have its advantages, giving Native Americans opportunities to exercise their agency and opening up avenues for fruitful cross-pollination between cultures.

In the second chapter, “The Return of Mi’kmaq to Living Tradition,” Graham Harvey revisits the anthropological scene first explored by Anne-Christine Hornborg in her study Mi’kmaq Landscapes: From Animism to Sacred Ecology (2008). Harvey discusses several key aspects of indigenous traditions to which Hornborg brought attention in her study and elaborates on the importance of approaching both animism and Mi’kmaq identities as relational concepts, or as he puts it, “everyday matters of negotiation.”

In the third chapter, “Cosmologies of the Earth and Ether,” Michael Jackson continues exploring the spirituality and sociality of the Mi’kmaq, adding noteworthy parallel readings by comparing the Mi’kmaq with the Warlpiri and Māori peoples. Beginning with a summary of Professor Hornborg’s insights into Mi’kmaq spirituality, Jackson proceeds to explores the parallel scenes through a very personal account and – despite noting how difficult it is to avoid the implicit biases of the Judeo-Christian heritage in cross-cultural analyses – he finds striking similarities in the way community and family translates into the religious, moral, and tribal identities of these peoples.

The fourth chapter, “Subsumed Rituals,” is authored by Mikael Rothstein and begins the exploration which is the topic of several other chapters in this volume: the ritual perspectives of divination. Rothstein investigates the intrinsic implications of divination among the Eastern Penan of Malaysian Borneo, and their relation to objects imbued with power. He introduces the notion of ‘subsumed ritual’, a form of ritual that approaches the domain of divination and relation to powerful objects not by identifying these practices as different – displacing time, place, or identity as rituals often are thought to do – but rather as practices that are integrated in the everyday life, rituals that gain their power precisely because they are unquestionable parts of life, just as eating and sleeping are.

In chapter five we invite the readers to reacquaint themselves with Ronald Grimes’ classic essay “Where is Here?” Here Grimes explores the dynamics of the human relation to place and land. In a very personal account, he discusses the fact that his own home, and the land on which it stands, have belonged to other peoples, peoples that did not necessarily give them up freely. Through Grimes’ account we encounter insightful reflections on what it means to be a ‘neighbour’, the human relation to land, landscape, and their importance for identity, as well as actions of displacement and the practice of ‘bad rituals’.

Part 2: Ritual, Ecology, and New Spiritualities

In the second part of the book, entitled “Ritual, Ecology, and New Spiritualities,” the explorations in ritual studies pay attention to two themes: new spiritualties and environmentalism. The distinction between religion and spirituality has been the subject of considerable scholarly discussion. Nonetheless, for many practitioners of new spirituality the difference between religion and spirituality is real and cannot be escaped by an alternative definition of religion. The anthropologist of religion Anne-Christine Hornborg notes that the sentence “I’m spiritual, not religious” has become a key expression of a new form of globalised religion, that focuses on a specific notion of spirituality signifying a universal human essence located deep inside everyone. Hornborg concludes: “The message is: Spirituality unites us into a single humanity, while religion, with its dogma and rituals, separates us” (Hornborg 2011: 249). Many scholars have contributed to the understanding of new forms of spirituality. Paul Heelas’s analysis of religions in the modern world concludes that spirituality appears to be flourishing (Heelas 2005). Rather than a trajectory where the religious is giving way to the secular; the religious is giving way to the spiritual. Heelas finds a key characteristic, which has come to be associated with spirituality: “Spirituality has to do with the personal, that which is interior or immanent” (Heelas 2005: 414). Therefore, contemporary spirituality may more precisely be termed “spirituality of life” (Heelas 2005: 414). According to Heelas, new spiritualities radicalise the expressive aspects of modernity; both affirming modern values and reacting against them. Although spiritualities are shaped by their time, they likewise encourage resistance and alternatives. Like Heelas, Christopher Partridge finds a contemporary situation where religion appears to be on the decline, but where spiritualities, conversely, seem to be alive and kicking. Partridge investigates the alternative spiritual milieu in the contemporary western world, where an increasing number of Westerners are in various ways discovering and articulating spiritual meaning in their lives. New ways of believing are not intricately tied to public institutions or buildings, but they are still socially significant (Partridge 2005: 3). Alternative spiritualities are found outside institutions and are entwined with popular culture and urban myths (Partridge 2005: 2). Again, this relates to how sources of inspiration that are often considered non-religious are an incentive for spiritual reflection, which is set in the intersection between spirituality and the environmental movement.

It should be noted that the interest in alternative spiritualities is not a new phenomenon. Non-traditional re-enchantment has been a long time coming, particularly in the past forty years, Partridge concludes. Partridge sees alternative spiritualties as distinct from new age spirituality. Other scholars, such as Steven J. Sutcliffe and Ingvild Sælid Gilhus, have offered perspectives on New Age which is “among the most disputed category in the study of religion” (Sutcliffe and Gilhus 2013: 2). Rather than considering New Age as demonstrating atypical forms of religion, Sutcliffe and Gilhus argue for the need of “a model of a religion that comprise new age phenomena” and “to develop a general model of religion, with a terminology to match” (Sutcliff and Gilhus 2013: 2). The contributions by Olav Hammer and Johan Nilsson in the present volume provide perspectives on new spiritualities with special attention to divination, and that of Ståhle focuses on new spiritualities in a contemporary secular context.

The theme of religion and ecology has attracted increasing attention in recent times in the shadow of the climate crisis. In 1967, Lynn White Jr’s article “The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis” set the agenda for the discussion of religion and ecology for decades to come. White, a scholar of medieval history, claimed that “especially in its Western form, Christianity is the most anthropocentric religion the world has seen” (White 1967: 1205). However, he found an alternative Christian approach in Saint Francis of Assisi. Today the ecological crisis has deepened, and scholars read the article in a new light (Worster 2017; Hamlin and Lodge 2006). Research in the emerging field of religion and ecology addresses the question: How do religious traditions respond to the challenges of the ecological crisis? Both representatives of religious traditions and scholars of religion have responded to the challenges of the ecological crisis and climate change. Parallel to religious traditions going through transformation in relation to ecology, research on these changes becomes increasingly relevant (Jenkins, Tucker and Grim 2017). The anthropologist of religion Bron Taylor labels claims that the world’s religions are becoming more environmentally friendly as “The Greening of Religion Hypothesis” (Taylor 2016: 268). Taylor distinguishes between green religion and dark green religion. In simple terms, green religion can be characterised as anthropocentric, and dark green religion as eco- or biocentric (Taylor 2010: 10). Roger Gottlieb points out how environmentalism challenges religions and how new spiritualties are often characterised by radical innovation, including the creation of new liturgies and rituals (Bauman et al. 2011: 115). Given this creative character it is perhaps reasonable to avoid defining spirituality too strictly, since this phenomenon is somewhat of a shapeshifter too. Hence, the theoretical discourse on spirituality sheds light on a complex phenomenon and relates to both ecology and ritual creativity.

In her study on Mi’kmaq people in Canadian Nova Scotia (2008) the anthropologist of religion Anne-Christine Hornborg shows how ritual studies, new spiritualties, ecology and environmentalism come together. The Mi’kmaq people undertook an environmentalist struggle against authorities planning to start a mining project on their sacred land. The Mi’kmaq endeavoured to stop the mining project, and to do so they performed a traditional pow-wow drumming ritual at the proposed mining sites. Hornborg argues that references to sacred land in environmentalist struggle adds “spiritual reasons to the more secular arguments that the environmental groups put forward” (Hornborg 2008: 280). References to the sacredness of places and spaces, such as mountains or forest, rather than environmental arguments are harder to reject for authorities, who “were not used to discuss spiritual values side by side with plans for a secular industrial project” (Hornborg 2008: 280). These issues are reoccurring themes in several chapters that bind Parts 1 and 2 of the present book together.

Part 2 elaborates on the discussion of new spiritualties and the relationship between spiritualties and ecology. It also contributes to discussions on ritual creativity through various examples. The contributors – Olav Hammer, Johan Nilsson, Ive Brissman, and Göran Ståhle – offer several cases from the field which bring fresh perspectives on ritual creativity and contribute to theoretical discussions on ritualisation. The section stars Olav Hammer who – in his chapter “Financial Astrology” – approaches divination as a form of ritualisation. Hammer studies how forms of divination – and specifically astrology – are useful for those who wish to predict the rise and fall of the stock market. The main question that informs this study is how rituals of celestial divination, grounded in symbolism that has its origins in a premodern era, have been transformed into methods for such a quintessential element of modern capitalist society as predicting the fluctuations of stock prices. Hammer offers a criticism of the recent history of financial astrology and places it in the context of historical records. He provides a thumbnail sketch of astrological symbolism and surveys how astrological symbols have been applied to the world of investing. Finally, he poses the question of how financial astrology functions compared to more conventional methods of market forecasting. Hammer’s contribution offers new and exciting perspectives on the relevance of ritual studies in areas which at a first glace might be viewed as topics detached from the field of studying rituals in religious studies.

Ritualisation and divination is also a theme in Johan Nilsson’s article “Manipulating the Sticks.” Nilsson’s chapter begins by noting the significance played by esoteric movements for how Asian religions have been viewed in ‘the West’. He discusses the westward migration of texts, ideas and practices originating in Asia, and especially how China became integrated in some of the influential historical narratives developed in the occult milieu. Nilsson further explores the creation of divination rituals influenced by the Ancient Chinese Book of Changes, the Yijing, within an influential early 20th century esoteric movement: Aleister Crowley’s Thelema. Crowley created a form of Yijing-based divination, one of the first well-documented examples of the practice of divination connected to the Yijing adapted to a worldview with historical roots in Europe. Nilsson discusses how Crowley’s ritual explorations became the basis of a community of practice which has continued to influence ritual techniques among new religious movements to the present day.

The merging of environmentalism and new spiritualties is manifested in the ritual practices connected to Dark Green spirituality. In “The Sounds of Silence,” Ive Brissman explores the role of silence in various workshops that aim to encourage reflection on environmental matters. Brissman draws from fieldwork conducted in environmental workshops in the UK. She discusses the practices of ritual silence (walks, sharing circles, meditations, et cetera) that work to stimulate and encourage reflection, and how minor ritual acts of silence can further our understanding of ritual creativity. Brissman applies Hornborg’s term ‘interrituality’ to address ritual creativity and how ritual acts are used as building blocks, not in creating new rituals but in the wider context of practices and workshops. Brissman argues that being in silence is a way to relate to a soundscape and larger-than-human-world and – relating to Donna Haraway – to make kin with other species and rebuild quiet places.

The last chapter in Part 2, “Durga is also living in Sweden,” authored by Göran Ståhle, brings us back to the question of how new spiritualities are lived out in secular contexts. Ståhle explores the celebration of a Hindu festival in the secular setting of contemporary Sweden by using Ronald Grimes’s concepts of competence and performance. Ståhle distinguishes different characteristic features of the celebration of Durga Puja, relating to ritual performance and competence. While variations are inherent in the performance of this festival, Ståhle identifies the framing of the festival in the Swedish secular setting as especially illustrative of how ritual sets and the settings interact. These insights contribute toward our understanding of the ritual performances of new spiritualities in what is often viewed as an increasingly secular majority society.

Part 3: Ritual and Body: Bodies as Rituals

Part 3 deals with rituals and bodies as well as viewing bodies as rituals. It can be argued that these are inseparable, and that any attempt at separating them is only possible because of the history of western philosophy and religion. In his famous work Discourse on Method (1637) René Descartes – whom Ronald Grimes has humorously described as “the bad-boy nemesis of all who would overcome body/mind dualism” (Grimes 2014: 337) – writes that he realised that he could pretend that he had no body, and that “there was no world nor any place in which I was present, but I could not pretend in the same way that I did not exist” (Descartes 1637 [1999]: part 4, 24–25). Although Descartes is seen as an important thinker in the scientific revolution, his religious insistence on the primacy of thought and ultimately of the soul (which he paradoxically thought was located in the pineal gland) and the Catholic God is one of the most important anchoring points of philosophy and science as intellectualism, rather than materialism. Like all of us, Descartes lived a bodily life, no matter how much his legacy of intellectualism over physicality might give the impression of the opposite. He drank and slept, he was a mercenary and a master fencer, he romanced women and fathered a child with a servant girl (which they lost to scarlet fever). Although the Cartesian split may never be bridged entirely, it is being criticised increasingly in the human, social, and natural sciences. In the context of Ritual Studies, Anne-Christine Hornborg has been an avid critic of over-intellectualisation, arguing for the importance of understanding the role of somatic modes of attention and pointing out the ‘blind alleys’ of Cartesian dualism:

I take a critical stance to intellectualism, which has defined the body as a passive object and, as such, only a reflection of ideas and symbolic meanings manifested in ritual practices. By contrast, phenomenology has shown that it is with a mindful body and somatic modes of attention that we approach the world and that bodies are active in learning and remembering. It is not only our mind that constructs identities and “imagined communities”; our body is at work simultaneously, and the Cartesian split between mind and body has generated blind alleys in ritual studies (Hornborg 2005: 356).

Some of the pitfalls of the understanding of the relation between ritual and body are linguistic in nature. Small words that separate the words body and ritual – words such as and, in, or of seem to infer connectedness, but may also implicitly signal separation. Bodies ritualise, are ritualised, or perform rituals. But can we separate rituals from bodies? Can we separate rituals from language? And can we separate language from bodies?

Whatever perspective one applies, the study of ritual is intricately linked to the study of the regulation or redefinition of bodies. Bodies are central to some of the oldest written outlines of ritual activity, whether it be living bodies, dead bodies, or bodies in the afterlife, such as in ancient Egyptian funerary texts, or the regulated display of discipline and ceremony by living bodies such as those of the ancient Chinese Book of Rites. Similarly, bodily aspects of ritual, and ritual contexts of bodies, social and physiological, have been, and remain central to Ritual Studies. The four chapters of Part 3 investigate this intricate relationship between rituals and bodies, rituals as bodies – and even bodies as rituals – in the context of a variety of case-studies. They offer fresh perspectives on distinct areas related to the intersection between body and ritual. In the first chapter of Part 3 entitled “Ritual dance from a Philosophical Perspective,” Erica Appelros asks and offers answers to why dance might be interpreted as a universal vehicle for religious experience and expression. Appelros’ chapter deals with this question through the lens of the philosophy of religion and casts light on how movement can embody religious concepts.

In the chapter “Transformation Beyond the Threshold” Olivia Cejvan investigates a Swedish initiatory society, Sodalitas Rosae Crucis (S.R.C.), a group inspired by the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Based on two years of fieldwork Cejvan explores how ritual heritage from the 19th century is brought to life in group rituals and solitary ritual work by individual members. Cejvan’s chapter offers new insights on rituals from anthropological and educational theory and applies them in new and thought-provoking ways on a contemporary initiatory society.

Paul Linjamaa’s chapter “Bringing Embodiment Back to Antiquity” presents a novel exploration of one of very few textual fragments traceable to the early Christian theologian Valentinus. Based on points made by Professor Anne-Christine Hornborg, that “religion is lived, carried and manifested in human bodies” the chapter analyses the rhetorical concept parrhésia (παρρησία) and argues for a bodily dimension to Valentinus’ work, rather than a strict religious intellectualism. As such, the piece exemplifies how contemporary ritual theory allows us to approach ancient material in new ways.

Finally, in the chapter “Man Who Catch Fly with Chopstick, Accomplish Anything” Tao Thykier Makeeff explores ritualised bodily learning and pursuits of excellence in the martial arts. He proposes that martial arts are an overlooked, but relevant cultural practice in Ritual Studies. Through analyses of both traditional and modern examples, as well as pop-cultural representations, he demonstrates that martial arts share key characteristics with ritual, and that both social and physiological changes result from the ritualised repetition of movements.

Part 4: Regional Perspectives: Islam and African Christianity

The fourth and last part of the book explores rituals from regional perspectives in the two largest religions in the world: Christianity and Islam. However, as the contributions here illustrate, regional perspectives in ritual and religious studies often demonstrate what theoreticians of religion frequently point out: categories spanning vast areas of space and lengths of time are accompanied by serious limitations. The first chapter in this part of the book is an exploration into a ritual that is performed daily by millions of Muslims world-wide: al-ṣalāt. In his chapter “Al-ṣalāt: The ritual of rituals in Islam” Jonas Otterbeck presents broad insights into this ritual, by revisiting the meaning making aspect of rituals, its importance for sustaining and building viable group identities. Otterbeck presents al-ṣalāt as a forceful ritual that both enables the practitioner to express their individuality while attaching themselves to broader identities. Otterbeck argues that it is vital for ritual analyses to focus not only on words and acts but to recognise how rituals are part of socialisation and its discourses of meaning making.

In the second chapter of this final part of the book we are immediately brought back ‘to the ground’. From the broader reflections offered by Otterbeck concerning the wide-ranging Muslim ritual al-ṣalāt, Hege Markussen presents an exploration of ritual perspectives relating to a very concentrated reflection of Islam: an annual Alevi festival in central Turkey in commemoration of the thirteenth century Sufi saint Hacı Bektaş Veli. While previous studies of the ritual aspects of this festival have highlighted its diversity and commemorational activities Markussen approaches the festival as an arena of complex ritual participation and reflects on the meeting between devotee and researcher. Markussen reflects on the ‘ritual field’ as an arena where both researcher and devotee are seen as participating ritually, but from different perspectives.

These two chapters which open the last segment of the book demonstrate the breadth of ritual studies. The last two contributions in the final part of the book offer insights into a growing field of study, in a way bringing back ritual studies to a context in which it was once developed: in the meeting with African peoples. In her chapter entitled “Who Got the Rite Wrong?” Martina Prosén explores the innovative use of music and dance among young adults in the mega-church of Mavuno in Nairobi, Kenya. In particular, Prosén reflects on an alternative Christmas service she attended in the church in December 2013. She argues that the ritual framing of the event enabled young people to divulge thoughts and ideas about feelings that are rarely spoken of in church, concerning romantic desire, jealousy, and anger. However, this new ritual setting which caters to the emotional needs of the congregation’s young people comes at a price: in order for the rite to be successful for part of the congregation, it is necessary for it to fail for others.

In the last chapter of the book “A Ritual that Turned the World Upside Down” Mika Vähäkangas explores the ritual setting of what is known as “the annulment of Ham’s curse,” a ritual performed in Kimbanguist communities around the world. Vähäkangas begins by setting the ritual in its historical, political, and cultural-religious context and proceeds to interpret it in the particular Kimbanguist cosmology. Vähäkangas demonstrates how the ritual is employed by Kimbanguist to counter colonialism, a way for a community to renegotiate their black identity. As such, Vähäkangas offers important insights of the ways in which rituals are employed to challenge feelings of oppression in a post-colonial world and the recreation of new identities based on older historical and cosmological paradigms.

References

Bauman, W.A., Bohannan, R., and O’Brien, K.J. 2011. Grounding Religion: A Field Guide to the Study of Religion and Ecology. Abingdon: Routledge.

Buckley Jr., William F. 1964. Boston Globe. September.

Descartes, R. 1999 [1637]. Discourse on Method in Discourse on Method and Related Writings. Trans. D.M. Clarke. London: Penguin Edition.

Hamlin, C., and Lodge, D.M., eds. 2006. Religion and New Ecology: Environmental Responsibility in a World of Flux. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

Harvey, G. 2000. “Introduction.” In G. Harvey, ed., Indigenous Religions: A Companion. London and New York: Cassell, 1–19.

Heelas, P. 2002 [2005]. “The Spiritual Revolution: From ‘Religion’ to ‘Spirituality’.” In L. Woodhead, P. Fletcher, H. Kawanami, and D. Smith, eds., Religions in the Modern World. London: Routledge.

Heelas, P. and Woodhead, L. 2005. The Spiritual Revolution: Why Religion is Giving Way to Spirituality. Malden: Blackwell.

Heelas, P. 2008. Spiritualities of Life: New Age Romanticism and Consumptive Capitalism. Malden: Blackwell.

Hornborg, Anne-Christine. 2001. A Landscape of Left-Overs. London: Ashgate.

Hornborg, Anne-Christine. 2005. “Eloquent Bodies: Rituals in the Contexts of Alleviating Suffering.” Numen 52:3, 356–394.

Hornborg, Anne-Christine. 2008. “Protecting the Earth? Rappaport’s Vision of Rituals as Environmental Practices.” Journal of Human Ecology 23:4, 275–283.

Hornborg, Anne-Christine. 2008. Mi’kmaq Landscapes: From Animism to Sacred Ecology. London: Routledge.

Hornborg, Anne-Christine. 2009. “Selling Nature, Selling Health: The Commodification of Ritual Healing in Late Modern Sweden.” In S. Bergmann and K. Yong-Bock, eds., Religion, Ecology & Gender: East-West Perspectives. Berlin: LIT, 109–130.

Hornborg, Anne-Christine. 2011. “Are we all spiritual?” in Journal for the Study of Spirituality 1:2, 249–268.

Gottlieb, R.S. 1996. This Sacred Earth: Religion, Nature, Environment. New York: Routledge.

Gottlieb, R.S., ed. 2003. Liberating Faith: Religious Voices for Justice, Peace, & Ecological Wisdom. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Pub.

Gottlieb, R.S. 2003. “Saving the World: Religion and Politics in the Environmental Movement.” In R.S. Gottlieb, ed., Liberating Faith: Religious Voices for Justice, Peace, & Ecological Wisdom. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Pub., 491–512.

Gottlieb, R.S. 2003. “Tradition: Ethical Roots of Spiritual Social Activism.” In R.S. Gottlieb, ed., Liberating Faith: Religious Voices for Justice, Peace, & Ecological Wisdom. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Pub., 1–3.

Gottlieb, R.S. 2006. A Greener Faith: Religious Environmentalism and Our Planet’s Future. New York: Oxford University Press.

Grimes, R.L. 2014. The Craft of Ritual Studies. New York: Oxford University Press.

Jenkins, W., Tucker, M.E., and Grim, J., eds. 2017. The Routledge Handbook of Religion and Ecology. Abingdon: Routledge.

Partridge, C. 2005. Re-enchantment in the West: Understanding Popular Culture. Vol. 1. London: T&T Clark International.

Partridge, C. 2005. Re-enchantment in the West: Alternative Spiritualities, Sacralization Popular Culture and Occulture. Vol. II. London: T&T Clark International.

Sutcliffe, S.J. and Gilhus, I.S. 2013. New Age Spirituality: Rethinking Religion. London: Routledge.

Taylor, B. 2010. Dark Green Religion: Nature Spirituality and the Planetary Future. Berkley: University of California Press.

Taylor, B. 2016. “The Greening of Religion Hypothesis (Part One): From Lynn White, Jr and Claims That Religions Can Promote Environmentally Destructive Attitudes and Behaviors to Assertions They Are Becoming Environmentally Friendly.” Journal of the Study of Religion and Culture 10:3, 268–305.

White, L. Jr. 1967. “The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis.” Science 155, 1203–1207.

Whitney, E. 2006. “Christianity and Changing Concept of Nature: An Historical Perspective.” In Lodge and Hamlin, eds., Religion and The New Ecology: Environmental Responsibility in a World In Flux. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 26–52.

Worster, D. 2017. “History.” In W. Jenkins, M.E. Tucker, and J. Grim, eds., The Routledge Handbook of Religion and Ecology. Abingdon: Routledge, 347–354.

Part 1: Ritual and Indigenous Religion

∵

Chapter 1: Earthen Spirituality or Cultural Genocide?{2}

Radical Environmentalism’s Appropriation of Native American Spirituality

Bron Taylor

1. Introduction[2]

The problem is one of cultural appropriation. Eurocentric intellectuals habitually take the knowledge of indigenous peoples and incorporate it into their own thinking, usually without attribution. In the process they tend to deform it beyond recognition, bending it to suit their own social, economic and political objectives. Unfortunately, this has, with very few exceptions, proven to be as true of professed ‘allies’ of native people as it has of their avowed enemies.

M. Annette Jaimes, Alfred University

This epigraph introduces a scathing critique by Ward Churchill of Jerry Mander’s In the Absence of the Sacred (Mander 1992). Ward Churchill, who was then well known as an American Indian Movement (AIM) intellectual and activist, had “been sharply critical of the appropriation of Native American ideas and spirituality by Euroamericans” (Churchill 1993: 43–48). Mander had argued that Native American wisdom could help us discern how to live in harmony with nature “if only we’d let them be and listen to what they say” (Mander 1992: 382). Churchill concluded that despite Mander’s stated desire to learn from Indians, by borrowing from them largely without attribution, and by absorbing Indian ideas “as their own ‘intellectual property’ while synthesising new (and therefore inherently ‘superior’) vernaculars of societal/ecological reality,” Mander “embodies the worst of what [he] purports to oppose,” namely, the destruction of indigenous culture and wisdom (Churchill 1993: 46, 43).

It is easy to assemble examples where New Age devotees or others drawn to Native American spirituality have stolen sacred artefacts, trespassed and desecrated places considered sacred, or interrupted ceremonies while insisting that they have a right to be present.[3] There are writers who have been accused of profiteering off Native American cultures by fabricating experiences or apprenticeships with indigenous shamans (Rose 1992: 403–421). There are non-Indians who are scorned for profiteering off of sweat lodges or other ceremonies that are purportedly derived from Native American traditions. Some of these practices clearly hinder and even thwart specific Native American religious practices (Rose 1992; Deloria 1992: 35–39). Yet such threats to Native American religious practice seem small compared to the policies of Federal and State governments that fail to protect, or directly destroy (often through road building and subsequent commercial enterprise) the land base and specific places considered essential for ceremony, herb gathering, and so on (Jaimes 1992; Vecsey 1991).

Herein, I focus on cases of the borrowing and sharing of Native American spirituality where it is difficult to find agreement about what constitutes proper conduct or easily discern social impacts.[4] The following case studies and reflections are motivated equally by the belief that threats to Native American cultural integrity and religious practice are real and should be forthrightly resisted, and by a fear that blanket condemnations of the appropriation of Native American cultural practices may hinder the nascent and fragile alliances developing in some regions between Indians and non-Indians, and thereby erode the survival prospects of native peoples, their cultures, and places.

My primary purpose is to provide careful descriptions of the specific dynamics involved in, and of the arguments about, the appropriation of Native American spirituality, so that readers can form their own views about these phenomena. A secondary purpose is to submit my own views about these dynamics for the reader’s consideration, with the understanding that I consider them to be tentative and subject to further revision. Ultimately, I hope the description and reflections in this paper will contribute to dialogue and behaviours that will reduce the tensions attending these phenomena.

I began this inquiry with three main perspectives in mind about the appropriation of Native American spirituality. Put simply, one view argued similarly to Churchill that, however well intended, such borrowing represents a form of cultural genocide, either destroying such traditions by syncretistically transforming them as they selectively borrow from them, and/or directly threatening Indian survival by assuming that native spiritualities are dead and in need of resuscitation by whites. A second view contended that the appropriation of Native American religion is impossible, since the resulting phenomenon is no longer Native American religion. A third view held that, since the borrowing of myth, symbol, and rite from one group by another is a central characteristic of cultural and religious evolution, it is inappropriate for religious studies scholars to categorically condemn such developments because such condemnations inevitably privilege one form of religion over another.[5]

Some readers would like to know something about my conclusions at the outset. For now, I hope it will suffice to say that I have found – in various ways to be specified later – that there is merit to and legitimate concerns expressed in each of the preceding three views. Other readers will be interested to know whether and to what extent I have participated in ceremonies led by or borrowed from Native American traditions. My participation in Native American ceremony has been limited to several occasions where Indians and Euroamerican environmental activists have gathered in solidarity around issues of mutual concern. Often, during such occasions prayers and sometimes rituals are performed, usually led by an Indian elder or medicine person. My own participation has been limited to standing and respectfully listening to such proceedings.[6]

2. Case Studies

The following discussion is based on field observations and archival research conducted between 1990 and 1996 exploring several streams of the North American Deep Ecology (or Radical Environmental) movement, focusing especially on its radical vanguard, Earth First!. Earth First! is best known for dramatic civil disobedience campaigns and the use of sabotage in their efforts to thwart commercial incursions into the planet’s few remaining roadless areas (Taylor 1995). Earth First! activists believe that the natural world has value apart from its usefulness to humans. This moral claim is often grounded in mystical experiences in the natural world that yield pantheistic and/or panentheistic worldviews, and is often combined with a sense that nature is full of animate, spiritual intelligences, including but not always limited to animals, who can communicate with humans. I have previously labelled Earth First!’s religious orientation “primal spirituality” because many within this subculture venerate and seek to learn from and emulate the world’s remaining indigenous cultures, especially those cultures unassimilated into the global market economy. They generally consider such cultures to be spiritually and ecologically wise (Taylor 1994: 185–209).

The desire of many deep ecologists to learn from indigenous cultures produces an impulse to borrow ritual practices (Taylor 1995). In North America, this has been facilitated by the increasing openness of some Native Americans to such cultural sharing and by the proliferation of New Age practitioners and institutes claiming to be authentic bearers of such practices. The following examines such appropriation within the Deep Ecology movement and explores the ensuing controversy among those Indians and Earth First!ers who are attempting to work out an alliance in defence of places that both consider sacred.

3. Gary Snyder: Early Appropriation by an Elder of the Deep Ecology Movement

Gary Snyder is considered an ‘elder’ within the Deep Ecology movement. His Pulitzer prize winning book, Turtle Island (1969), borrowed its title from a Native American name for North America. Snyder hoped to promote what he took to be native wisdom regarding the sacrality of the landscape, believing that ultimately all people are capable of becoming psychologically and spiritually Native American (Snyder 1990). During his most formative years a Native American path was inaccessible to him so he went to Japan to study Zen Buddhism, eventually calling himself “a practicing Buddhist, or Buddhist-shamanist” (Snyder 1980: 33). Snyder was subsequently criticised for “cultural imperialism in the adoption of the persona of a white shaman/healer.”[7] He responded that shamanism is a universal cultural experience, is not “proprietary … to any one culture,” and is found everywhere throughout most of pre-history, not only among Native Americans. Although crediting Native Americans for preserving shamanism in North America, Snyder insisted that at the centre of shamanism is “a teaching from the nonhuman.” Shamanistic experiences are widely available, Snyder believes, because they are ultimately rooted in “a naked experience that some people have out in the woods” (Snyder 1980: 154–155). He argues that many Native American stories, “like the trickster and the woman who married the Bear … are found all over the world. Nobody owns them. It’s only a lack of [a global] perspective that would make people think such things are their own property.”[8]