James Sinks

Cutting the timber harvests

Unhappy with forest protection plans, protesters fight to make cuttings stop

November 28, 1999

The Forest Plan

Good intentions, poor results

Sunday, Nov. 14

-

High expectations

Sunday, Nov. 21

-

Where did the money go?

Sunday, Nov. 28

-

Cutting the harvests

The Northwest Forest Plan offered the timber industry and environmentalists a compromise: There would be less timber cut, but the national forests o the region would still supply a steady flow of raw logs to mills, and agencies would survey the wood: to ensure no rare species would be endangered. That hasn’t happened. From the beginning, both sides hated the plan. What’s happening now?

Sunday, Dec. 5

-

Toward an uncertain future

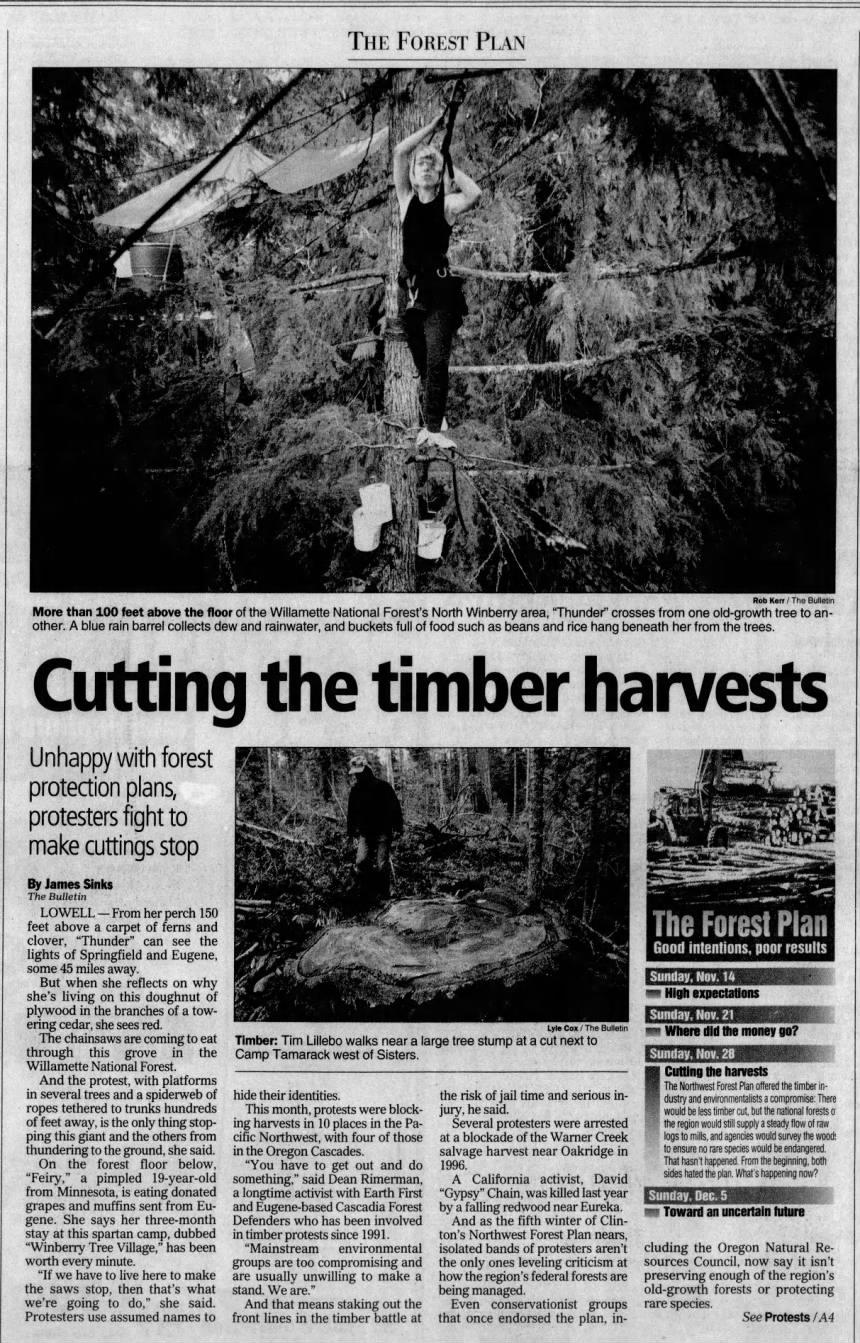

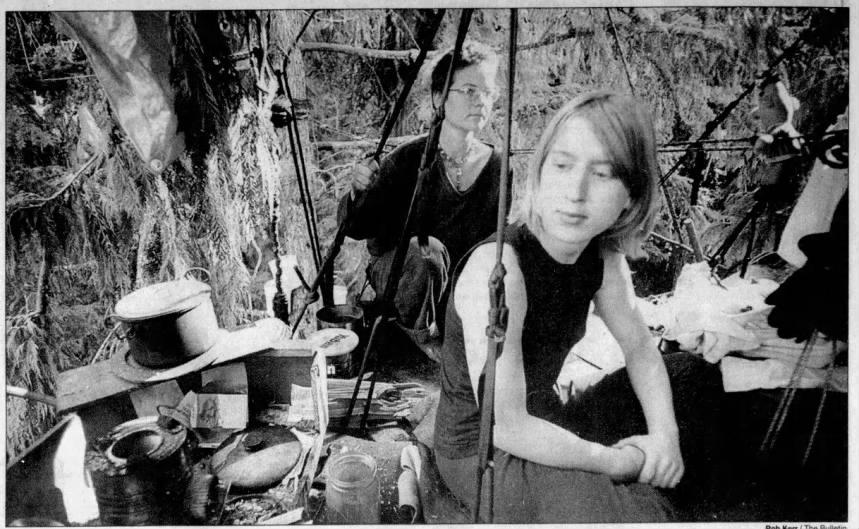

More than 100 feet above the floor of the Willamette National Forest’s North Winberry area, Thunder crosses from one old-growth tree to another. A blue rain barrel collects dew and rainwater, and buckets full of food such as beans and rice hang beneath her from the trees.

LOWELL — From her perch 150 feet above a carpet of ferns and clover, “Thunder” can see the lights of Springfield and Eugene, some 45 miles away.

But when she reflects on why she’s living on this doughnut of plywood in the branches of a towering cedar, she sees red.

The chainsaws are coming to eat through this grove in the Willamette National Forest.

And the protest, with platforms in several trees and a spiderweb of ropes tethered to trunks hundreds of feet away, is the only thing stopping this giant and the others from thundering to the ground, she said.

On the forest floor below, “Feiry,” a pimpled 19-year-old from Minnesota, is eating donated grapes and muffins sent from Eugene. She says her three-month stay at this spartan camp, dubbed “Winberry Tree Village,” has been worth every minute.

“If we have to live here to make the saws stop, then that’s what we’re going to do,” she said. Protesters use assumed names to hide their identities.

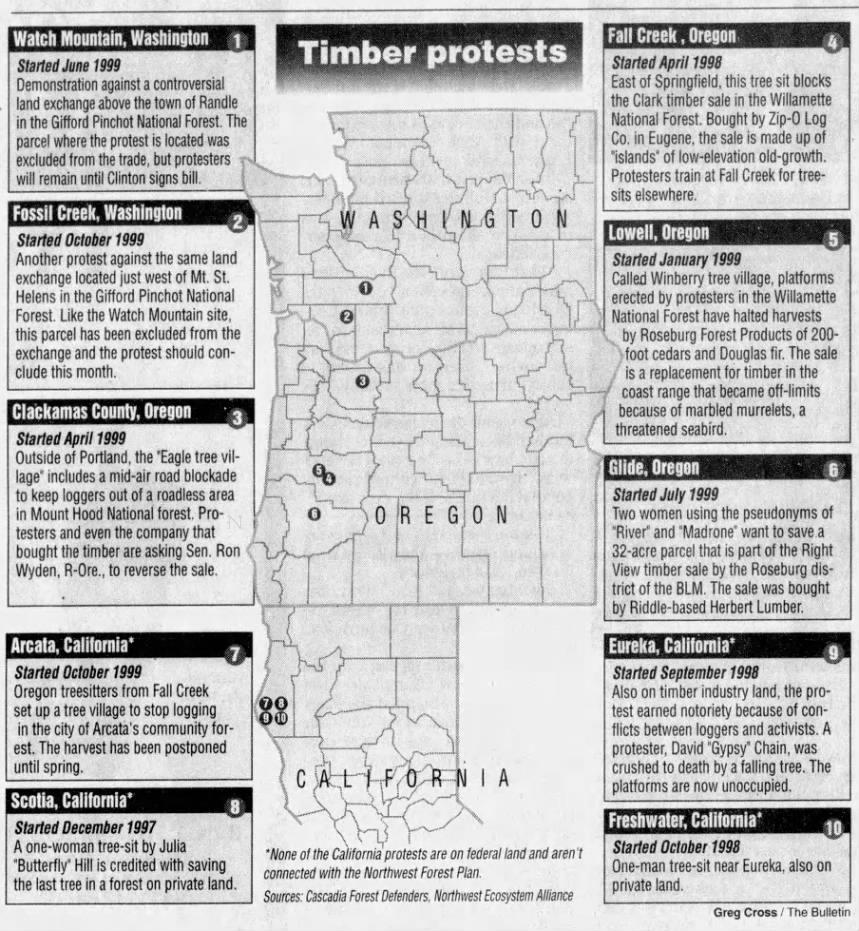

This month, protests were blocking harvests in 10 places in the Pacific Northwest, with four of those in the Oregon Cascades.

“You have to get out and do something,” said Dean Rimerman, a longtime activist with Earth First and Eugene-based Cascadia Forest Defenders who has been involved in timber protests since 1991.

“Mainstream environmental groups are too compromising and are usually unwilling to make a stand. We are.”

And that means staking out the front lines in the timber battle at the risk of jail time and serious injury, he said.

Several protesters were arrested at a blockade of the Warner Creek salvage harvest near Oakridge in 1996.

A California activist, David “Gypsy” Chain, was killed last year by a falling redwood near Eureka.

And as the fifth winter of Clinton’s Northwest Forest Plan nears, isolated bands of protesters aren’t the only ones leveling criticism at how the region’s federal forests are being managed.

Even conservationist groups that once endorsed the plan, including the Oregon Natural Resources Council, now say it isn’t preserving enough of the region’s old-growth forests or protecting rare species.

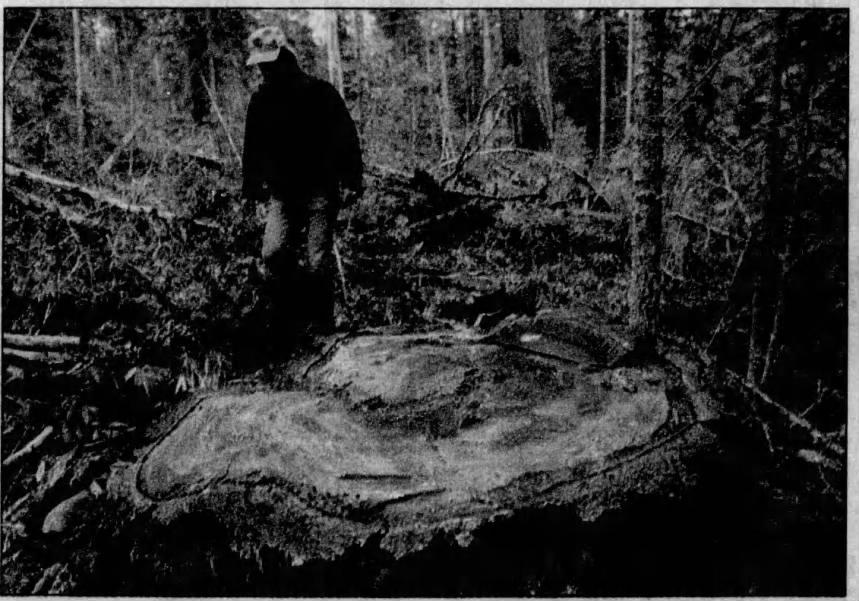

Timber: Tim Lillebo walks near a large tree stump at a cut next to Camp Tamarack west of Sisters.

They say it is riddled with loopholes that allow road building and cutting to continue in spotted owl habitat, and that the U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management have been too accommodating to the timber industry in order to “get out the cut.”

And they say taxpayers shouldn’t be footing the bill for federal timber harvests, which often lose money according to government audits.

“The Northwest Forest Plan started with a lot of promise,” said Dave Werntz of the Northwest Ecosystem Alliance in Washington state. “But there has been a clear record of agency law-breaking and failure to meet a balance on our public lands.”

At a 1993 forest summit in Portland, President Clinton said the forest plan would be compromise that would appease the timber industry and the environmental movement.

It turned out to do neither.

“The plan from the start has been very controversial,” said Jim Lyons, an assistant secretary with the U.S. Department of Agriculture who oversees the U.S. Forest Service.

But he said the Clinton plan is working as intended, even amid growing criticism. “People are frustrated because the plan isn’t doing everything they’d like it to do. But if nobody’s happy it must be the right thing.”

But Jim Geisinger, president of the industry-backed Northwest Forestry Association, said environmentalists and a sympathetic Clinton-Gore administration won the battle over the forests.

Timber companies that rely on public logs were the losers, he said.

“It gave the environmental community everything they asked for and then some,” Geisinger said.

“There are 24 million acres of federal forests and 20 million are off-limits to regularly scheduled harvests,” he said. “How much more environmental protection do we need? It’s ridiculous.”

Undercut plan

But activists maintain the forest plan still doesn’t do enough, or has been undercut by pro-timber industry lawmakers.

The so-called “salvage rider” approved by Congress and signed by Clinton in 1995 helped erode already shaky support among conservationists, said Andy Kerr of The Larch Co.

That law banned appeals and mandated the logging of many green stands of timber, including some that was made off-limits because of species and landslide concerns.

“I want the plan to succeed but we’re not going to allow it to succeed in a lopsided way,” said Joseph Bower, spokesman for Citizens for Better Forestry in Hayfork, Calif. “This is not a timber plan, it is an ecosystem management plan.”

He said pro-industry lawmakers have failed to supply the funding for research and ecosystem restoration needed to make the forest plan work.

“These guys aren’t dumb,” he said. “The very congressmen who are railing at the Forest Service are the same ones who are causing this.”

Environmentalists aren’t only airing their gripes in the trees. They’re also doing it in the courtroom.

Virtually every timber sale is appealed, and three high-profile cases are in the courts this year.

In two of this year’s suits, judges agreed that federal agencies failed to follow the forest plan before offering trees for harvest.

One of those cases was settled last week, with the government agreeing to perform surveys for rare species. Without those surveys, logging could be killing off other rare species that live in old-growth forests, said Tim Lillebo, Eastern Oregon representative for the Oregon Natural Resources Council.

In the other suit, a judge halted 24 sales in the Umpqua basin near Roseburg because agencies hadn’t created “aquatic conservation strategies” as required.

A third lawsuit, filed in June by a collection of groups including the John Muir Project and the Eugenebased Native Forest Council, calls for banning logging on federal land in the entire Pacific Northwest, charging that Clinton’s plan failed to protect the spotted owl.

“President Clinton promised a plan that was ecologically sound and legally defensible, but it’s neither,” said Michael Donnelly, president of the Friends of the Breiten-bush Cascades.

A study this year showed the ‘owls are dying at a rate of 4 percent a year — and agencies are still routinely approving sales near known nests, said Jim Britell with the Kalmiopsis Audubon Society on the Southern Oregon coast.

Kurt Loop, director of the Regional Ecosystem Office in Portland, said the Clinton plan forecasted a drop in owl population until forests regenerate in several decades.

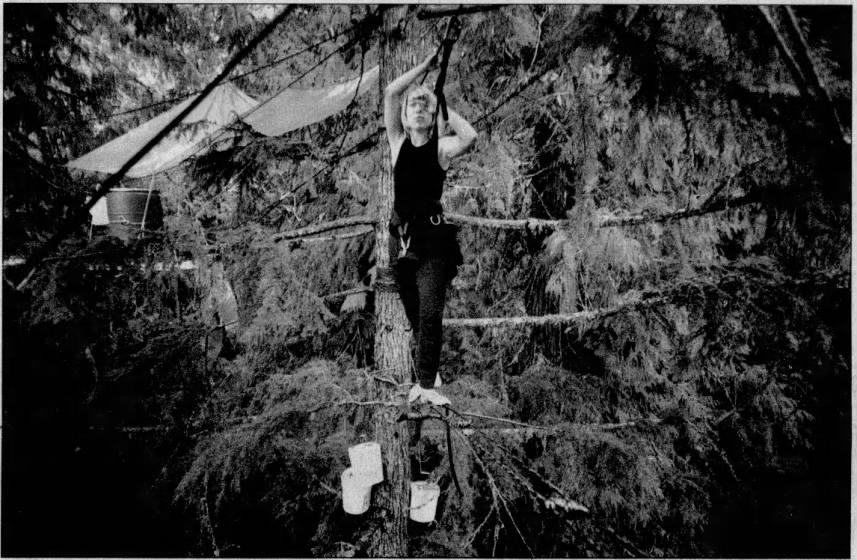

Bare necessities: Tree sitters Thunder, front, and Squirrel lounge on their platform in the old-growth canopy with only the bare necessities. A cook stove and Ernie doll greet visitors at the top of an uphaul rope (seen at right).

Loopholes

Activists also say loopholes in the plan are allowing a surprising amount of timber to be cut in protected reserves — more than 20 percent of the total harvest in the region by some estimates.

In the Deschutes National Forest, for instance, roughly 10 million board feet is being removed as part of a so-called “restoration project.”

“This was some of the best stuff out there, and they just went in and wiped out all the habitat that was left,” Lillebo said. “We thought the reserve was supposed to be protected. But these were big green trees and it was just logged and destroyed.”

But Gery Ferguson, a planner with the forest, said much of that timber is dead and is being cut to reduce the danger of fire or the likelihood of beetle infestation — a common problem in Oregon’s eastern forests.

The forest plan allows cutting to occur in the reserves, provided the trees are younger than 80 years old and the thinning helps wildlife. But Lillebo said some of the trees cut in the Santiam project are much older.

With her digital camera in hand, Francis Eatherington has scouted roads and log landings in Southern Oregon’s Umpqua basin that were permitted in no-cut zones.

The road-building allows companies to cut and cart away big trees without having to bid on them, she said, and one of those roads even washed into a creek

Meanwhile, ugly clearcuts still are occurring in the reserves. “They still get to cut plenty,” said Eather-ington, a member of watchdog group Umpqua Watersheds Inc.

Glenn Lahti, natural resource specialist with the Roseburg district of the Bureau of Land Management, said the agency’s hands are tied when it comes to logging roads.

That’s because it must honor long-standing contracts that allow adjacent landowners to cross the reserves.

The BLM manages land in a checkerboard pattern, which means some private property can’t be reached without crossing federal parcels.

But the agency has worked to try and find the least-damaging routes for roads, Lahti said.

He also said companies have proved to be responsible and quickly fix failing roads. And the clearcuts criticized by Eatherington were small and designed to create openings for wildlife, he said.

“All of this is covered under the plan,” Lahti said. “The plan is the best thing we’ve got going.”

Flawed plan

But many conservationists say the plan itself is flawed. They say too much of the acreage designated as off limits is simply logged-over forestland, not untouched older stands. And they say the plan shouldn’t allow for more old growth to be razed, even though that was part of the compromise.

“How do you save anything by cutting half of what’s left?” said Tim Hermach of the Native Forest Council. “We’re liquidating publicly held wealth as though an 800-year-old tree is replaceable.”

A growing number of scientists and even Gov. John Kitzhaber agree that cutting older trees seems to undermine the goal of the plan, which is to promote the health of species that live in mature forests.

Environmentalists also criticize land swaps, like one proposed in Washington state this year. In the past, many of those swaps have given taxpayers clearcuts while timber companies got prime old-growth groves.

Hermach said the value of old trees is underestimated in such trades.

Two tree-sit protests were erected on controversial parcels in that proposed swap — and those trees have been removed from the exchange.

The North Winberry parcel east of Springfield was traded to Scott Timber Co., the logging arm of Roseburg Forest Products, because rare marbled murrelets, a tiny seabird, were found in a purchase in the coast range.

The Winberry trees were scheduled to be cut in the next decade, but Rimerman and the other protesters want Sen. Ron Wyden, R-Ore., to pull the plug indefinitely.

Roy Keene, a Eugene logger turned “green forester,” said the swap is a sweetheart deal for the timber company and doesn’t pencil out for the Forest Service.

“This is a double-ugly,” he said, standing at the base of a Western red cedar that measures more than eight feet across. Sunlight filters though a vaulted canopy of branches hundreds of feet overhead.

“They say this unit isn’t ecologically significant,” he said, shaking his head.

“These are trees that never should be cut in the first place. We shouldn’t be doing commercial logging in a heritage forest.”