Lydia Eccles

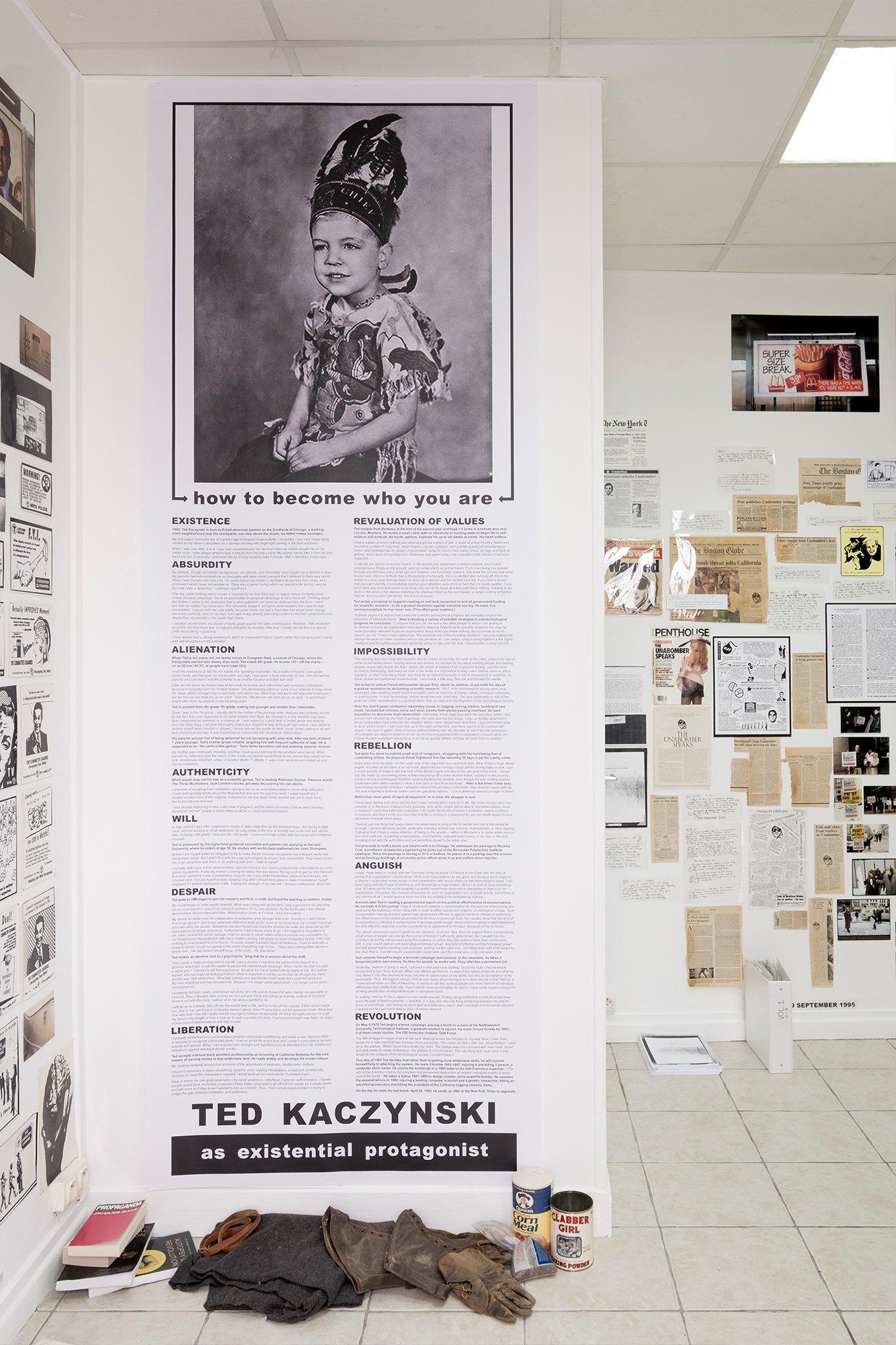

Ted Kaczynski as existential protagonist

2025

EXISTENCE

1942: Ted Kaczynski is born to Polish-American parents on the Southside of Chicago, a dingy working-class Polish neighborhood near the stockyards, one step above the slums. His father makes sausages.

My first vague memories are of a golden age of blessed irresponsibility. I remember I was very happy being carried on my father’s shoulders on a Sunday morning with bright light coming in the front windows.

When I was very little, 3 or 4, I was very concerned over the fact that when my mother bought me an ice cream cone, I was always afraid to take it directly from the lady’s hand. My mother had to take it from her and hand it to me. Eventually I overcame this by forcing myself to take it directly.

After a few times it was easy.

ABSURDITY

My parents, though of Catholic backgrounds, are atheists, and fortunately never taught me to believe in God. My parents had indoctrinated me so thoroughly with basic moral precepts that I adhered to them very strictly. When I was 5-years old I told a lie. For some reason my mother’s reprimand stung more than usual, and I promised I would never tell another lie. There was a period during which my special pride and joy was the fact that I was a “good boy.” I preened myself on it.

One day, while thinking about morals, it occurred to me that there was no logical reason for being good, unless personal advantage. But to be good solely for personal advantage is not a moral act. Thinking about this further, I came to the realization that a value-judgment can never be deduced from the facts. I went and told my mother my conclusion. She refused to accept it, and gave naive answers that I saw through immediately. I argued with her only briefly, because I knew she had a fixed idea that would never change, and it was perfectly clear to me that I was right. It was already becoming evident to me that I could think more clearly than my parents or the adults that I knew.

I decided I would make the choice of being good—just for the sake of being good. However, I felt crestfallen about the fact that there was no logical justification for morality. After that I usually did not feel any special pride about being a good boy.

I have always had a strong tendency to admit an unpleasant truth to myself, rather than trying to push it away with self-deception or rationalization.

ALIENATION

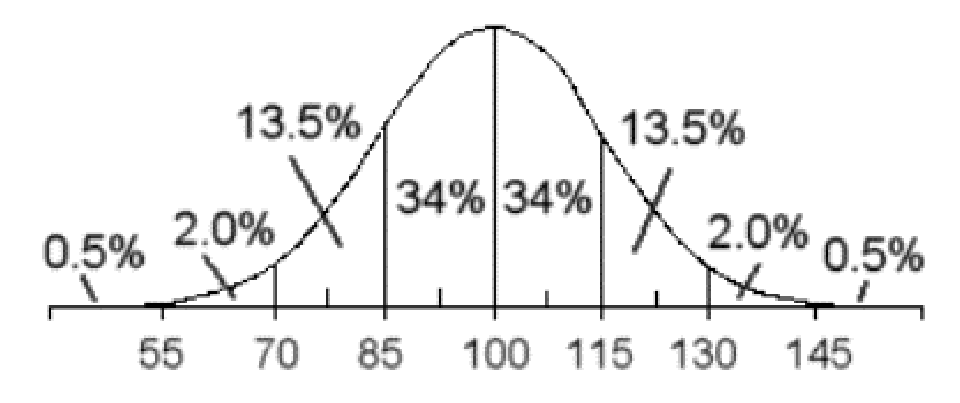

When Ted is ten-years old, his family moves to Evergreen Park, a suburb of Chicago, where the Kaczynskis earn less money than most. Ted enters 5th grade. Then he scores 167 on an IQ test.

I had the misfortune to fall into the hands of a “guidance councellor.” As a matter of routine I was given certain tests, and because my scores were very high, I was given a fairly elaborate IQ test. She phoned my parents and told them I had the potential to be another Einstein and blah blah blah.

Little did she know my mother was all too ready to receive such information with excessive enthusiasm, because it coincided with her fondest dreams. She immediately called up some of our relatives to brag about the news, which I thought was in bad taste, and said to me, “Miss Frye said we’re not supposed to tell you—but we feel we can treat you as an adult.” That line, “We feel we can treat you as an adult,” is something I heard often from my parents in the following years.

Ted is pushed from 5th grade up to 7th grade, making him younger and smaller than his classmates.

Once I was in the 7th grade, I quickly slid to the bottom of the pecking order. Jealousy was probably roused by the fact that I was supposed to be vastly smarter than them. My shyness in a new situation may have been interpreted as coldness or a superior air. I was subject to a good deal of verbal abuse and teasing from the other boys. I became thoroughly cowed and stayed that way all through high school. I was afraid to defend myself when insulted or abused. I simply ignored the insults as best I could. It had nothing to do with lack of physical courage. It was psychological—connected with dominance relationships.

His parents accuse him of being abnormal for not socializing with other kids. After the birth of David, 7 years younger, Ted’s mother turns irritable, targeting him with frequent outbursts of rage. He is supposed to be “the perfect little genius.” Ted’s father becomes cold and sneering, passive, morose.

When I was small, family entertainments often involved my father playing the piano, games, and stuff like that. In my teens, we all just sat squalidly in front of the television set, shovelling junk food into our mouths. My mother was continually shouting, scolding, insulting and blaming for me whatever went wrong. What earned my bitterness was the nature of the insults my parents would throw at me. Names they would call me: sick, emotionally disturbed, creep, or another Walter T. (Walter T. was a man we knew who ended up in a mental institution).

AUTHENTICITY

While adults map out his fate as a scientific genius, Ted is reading Robinson Crusoe, Treasure Island, The Three Muskateers, Jack London’s books, privately discovering his own desire.

I dreamed of escaping from civilization—going to live on an uninhabited island or some other wild place.

I read anthropology books about the Neanderthal man and the way they lived. I asked myself why I wanted to read more of this material. It dawned on me that what I really wanted was not to read more, but to actually live that way.

I was already beginning to take a dim view of progress and the future of society. I felt we were heading toward an “ant-hill” society in which there would be no more individual freedom.

WILL

In high school I was often subjected to insults or other indignities by the dominant boys. Not daring to fight back, and not wishing to show weakness, my only choice in the face of hostility was to be cold and stoical. After finishing 10th grade, I was put into 12th grade. I came out of high school with my social self-confidence crushed.

One summer when I was 15 or 16, in one of the prairies that still remained then, I threw a clod of earth at a bird. It “froze”, and I walked up to it and just picked it up. As soon as I had it in my hand it began to struggle violently. I held it in my hand for some time, and I soon began to experience warm, affectionate, pitying feelings for it. I had hoped to kill it as an act of hunting, in accord with my fantasies of a primitive life. But now I was turning soft. I thought, “How can I ever hope to experience a cave-man style life if I am too soft-hearted to kill game? For that kind of life I will have to be hard.” So I forced myself to kill the bird by crushing it in my hand. I left the place feeling sick with pity for the unfortunate creature.

Ted is pressured by his high-school guidance counsellor and parents into applying to Harvard University; he enters at age 16. He is drawn to mathematics because he finds it very difficult. He studies with world-class mathematician John Thompson and falls in love with pure—not applied—mathematics.

At first I felt myself under an obligation to try to make friends because my parents had criticized me for not being more social. But I didn’t fit in with the prep-school types by whom I was surrounded. They never invited me to go anywhere with them or do anything with them. I kept to myself. I have never been able to fully understand just what the externally visible traits of mine are that have always caused me to be marked out as different.

I actually didn’t give a fuck about whether I got into Harvard, but I had to pretend to be interested so as not to shock my parents. My most persistent fantasy was to live, at least temporarily, a savage life completely independent of organized society. But I hadn’t the least idea of how to get what I wanted.

It was my mother’s craving for status that was behind the big push to get me into Harvard. I went because my parents expected it and I didn’t know what else to do. But once I got there it was a tremendous thing for me. I was under tremendous pressure and tension, but I thrived on it. I forced myself to keep studying long after I should have gone to sleep. I considered myself negligent if I went to bed before 2 AM.

Feeling the strength of my own will, I became enthusiastic about will power.

I think that when the average person is doing nothing, his mind tends to wander more-or-less at random. This can happen to me too; but I have a strong tendency to settle instead on a particular subject, and think about it intently, turning it over and over in my mind and examining it from all angles. Once I get involved in a problem, whether in working with my mind or with my hands, even if that problem was of no great interest to me at the beginning, I have a tendency to become quite concerned with it and devote great care and attention to it.

DESPAIR

Ted goes to U. Michigan to earn his master’s and Ph.D. in mathematics. He finds the teaching careless, sloppy.

My morale began to slide rapidly downhill. What was I doing with all the time I was supposed to be spending on my coursework? I spent it on research problems of my own devising. By the fourth year I was deeply demoralized, discouraged and bitter. Mathematics—even at it’s best—was only a game.

My desire for wilderness life independent of civilization grew stronger than ever. Trouble is, I didn’t know how to go about it; and it was extremely difficult to work up the nerve to cut loose from my civilized moorings and take off to the woods.

Sometimes we don’t know how much the choices we make are governed by the expectations of people around us. Furthermore, I didn’t know where to go.

I felt trapped in my pattern of life; I felt I lacked the social courage. I had no sexual or social relationships to provide any consolation for my fundamental dissatisfaction with life in modern society. Life began to seem completely empty. I felt I had nothing to look forward to or to live for. To quote Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, “I had to deal with a being to whom I could not appeal in the name of anything high or low... There was nothing either above or below him... He had kicked himself loose of the earth... He was alone.”

Ted makes an abortive visit to a psychiatrist. He has second thoughts when he arrives for he appointment, so he lies that he is anxious about the draft.

Then came a major turning point in my life. Like a phoenix I rose from the ashes of my despair to a glorious new hope. (I ask the reader to pardon the melodramatic language.

When I write like that it is with a slight grin.) I wanted to kill that psychiatrist. Because the future looked utterly empty to me.

So I said to myself, why not really kill that psychiatrist? What is important is not the words that ran through my mind, but the way I felt about them. What was entirely new was the fact that I really felt I could kill someone. My very hopelessness had liberated me. Because I no longer cared about death. I no longer cared about consequences.

I suddenly felt that I really could break out of my rut in life and do things that were daring, irresponsible or criminal. Then I thought, well, as long as I am going to throw everything up anyway, instead of having to shoot it out with the cops, I will do what I’ve always wanted to do.

I will go up to Canada, take off into the woods with a rifle, and try to live off the country. If that doesn’t work out, and if I can get back to civilization before I starve, then I’ll come back and kill someone I hate.

What was new was that I now felt I really had the courage to behave irresponsibly. All these thoughts passed through my head in the length of time it took me to walk a quarter of a mile. I had acquired bright new hope, an angry, vicious kind of determination and high morale.

LIBERATION

I promptly embarked on a conscientious program of physical conditioning and made a new vigorous effort in learning to recognize edible wild plants. I had no social life at this time and I made it a principle to be both asocial and amoral.

What I had acquired was strength and hopefulness to be liberated from my conditioned inhibitions against defying authority overtly.

Ted accepts a tenure-track assistant professorship at University of California Berkeley for the sole reason of earning enough money to buy wilderness land. He reads widely in anticipation of the leap and develops his social critique.

My reading centered around true accounts of the adventures of explorers, frontiersmen, Indians.

I found it necessary to begin disciplining myself to avoid reading newspapers, except just occasionally, because if I read the newspapers regularly I would build up too much tense, frustrated anger.

Five examples of just a few of the things that I resented:

That my life depended on the decisions of dictators and politicians who had atom bombs at their disposal; boosters in the political and business worlds who pushed economic and population growth, thereby increasing air pollution, noise, over-crowding, and destruction of such wilderness as remained; scientists and engineers whose discoveries and inventions encouraged economic growth and population growth by increasing food supply, and increased the power of society to control individuals by either physical or psychological means; groups that pushed collectivist ideologies, which I feared might change society in such a way as to restrict my personal autonomy even further...

Here is where my one great weakness—my social weakness—interfered.

I was too self-conscious. I feared people would think me foolish or peculiar if they knew I proposed to go off into the woods for 2 weeks alone; and still more so if they knew I wanted to live as a hermit.

Thus, I had a great social problem in trying to bridge the gap between civilization and wilderness.

REVALUATION OF VALUES

Ted resigns from Berkeley at the end of his second year and buys 1.4 acres in a remote area near Lincoln, Montana. He builds a small cabin, with no electricity or running water, to begin the project of learning self-reliance skills and living in solitude and freedom. He hunts, gathers, gardens, explores the wilderness on expeditions of up to six weeks at a time. His heart softens.

I had a supper of which nothing was store-bought but a pinch of salt: a salad of yellow-monkey flower and brooklime; a stew of 3 squirrels, onion flowers, my own potatoes, and a small quantity of miscellaneous herbs, and huckleberries for desert.

A good meal! Today for lunch I had: salad, bread, oil, legs and back of grouse, and a quart of huckleberries. Yesterday, and again today, I ate a handful of the berries of red osier dogwood.

In city life you tend to be turned inward. In the woods your awareness is turned outward; you’ll notice inconspicuous things on the ground, such as edible plants or animal tracks. If a human being has passed through and left even just a small part of a footprint, you’ll probably notice it. You know the sounds that come to your ears: this is a birdcall, that is the buzzing of a horsefly, this is a startled deer running off, this is the thump of a pine cone that has been cut down by a squirrel and has landed on a log. If you hear a sound that you can’t identify, it immediately catches your attention, even if it’s so faint that it’s barely audible.

If you don’t have any work that needs to be done, you can sit for hours at a time just doing nothing, listening to the birds or the wind or the silence, watching the shadows move as the sun travels, or simply looking at familiar objects. And you don’t get bored. You’re just at peace.

Ted writes a proposal to create an anti-tech movement aiming to end all government funding for scientific research—to be a gradual revolution against industrial society. He mails it to environmentalists he has read, but never met: “In these pages it is argued that continued scientific and technical progress will inevitably result in the extinction of individual liberty.”

After evaluating a variety of possible strategies to end technological progress he concludes: “I propose that you join me and a few other people to whom I am writing in an attempt to found an organization dedicated to stopping federal aid to scientific research. You may be understandably reluctant to join an organization about which you know nothing, but you know as much about it as I do. It hasn’t been started yet. You would be one of the founding members. I am only making the attempt because no better qualified person has yet done so. I am simply trying to bring together a few highly intelligent and thoughtful people who would be willing to take over the task. I would prefer to drop out of it. personally because I am unsuited to that kind of work; in fact I dislike it intensely.”

(The recruitment effort goes nowhere.)

IMPOSSIBILITY

This morning was very fresh and beautiful. But as I came around the hill north of the cabin, I heard the roar of some snowmobiles ahead, buzzing around and around. It’s not that I’m shy about meeting people, but meeting people—especially people like that—upsets the sense of isolation from organized society. Just the noise by itself is distressing, and living out here in the winter it is impractical to keep one’s clothes clean or shave regularly, so that I look like a tramp, and must be an object of curiosity, if not of amusement or suspicion, to these slicked and pampered snow-mobilists. I went back a little way, then sat and brooded for awhile.

Ted writes to anarchist French philosopher Jacque Ellul. He has read his book, The Technological Society, six times. He lays out to Ellul his idea of a gradual revolution by de-funding scientific research:

“BUT, if the technological society were once destroyed, then anything might become possible, such as recovery of human values, individual autonomy, or anything else. In your terminology, history would become unblocked. The goal (attainable or not) of the proposal under consideration is a gradual rather than an explosive disintegration of the technological society.”

Over the next 5 years, civilization inexorably closes in on him: logging, mining, new-built roads, motorcycles, recreational vehicles, snowmobiles and trailers, planes passing loudly overhead on new flight patterns. On each expedition he discovers fresh destruction.

Until today, those ridge-tops were the one place where I felt secure from intrusion by this kind of garbage; this area was my last refuge. I was so terribly upset that if those cocksuckers had come into the meadow where I was I would have shot them.

I just don’t know what to do or where to turn.

I can’t just hole up in the cabin all the time, and there seems to be nowhere left where I can hunt or gather roots or berries without looking over my shoulder to see if the vile emissaries of civilization are about to break in on me.

As for returning permanently to civilization—I would rather die.

I never thought civilization would close in on me so quickly.

Where did they all come from so quickly?

REBELLION

Ted tests his nerve to commit small acts of vengeance, struggling with his humiliating fear of committing crimes—no physical threat scares him like the prospect of spending 30 days in jail for a petty crime.

A few miles from my cabin, on the south side of the ridge that runs east from here, Mine X had a large diesel engine mounted on the back of an old truck, apparently for running a large drill for boring holes in rock. I put a small quantity of sugar in the fuel tank of the diesel engine and also in the gas tank of the truck.

I broke into this trailer by unscrewing some screws and prying off a metal window-frame, ruining it in the process. (I had a strong psychological inhibition against breaking the window, even though it’s very unlikely anyone could have been within earshot.) I stole a few cans of food from the trailer.

After a few times it was easy.

Overcoming my earlier inhibition, I smashed most of the windows in the trailer, then reached inside with my rifle and smashed a Coleman lantern and two gas lamp fixtures. I put a generous amount of sugar in the diesel.

But within four more years of rapid development, Ted is tired; the struggle by sabotage is over.

I have been feeling ever since last fall that I have nothing left to hope for in life. My home country (as I now consider it) in Montana is being ruined gradually, and, while I might still be able to find wilder places, there is nowhere I could feel safe from civilization.

Life under the thumb of modern civilization seems worthless to measure and thus I more and more feel that life is coming to a dead-end for me and death begins to look attractive—it would mean peace.

There is just one thing that really makes me determined to cling to life for awhile and that is the desire for revenge. I want to kill some people, preferably including at least one scientist, businessman, or other bigshot.

Following that, I have a vague intention of taking to the woods—either in Montana or in some wilder place—and, from ambush, murdering snow-mobilists, motorcyclists, outboard motor users, or the like; in the end shooting it out with the authorities and not permitting myself to be taken alive.

Ted crafts a bomb and returns with it to Chicago. He addresses the package to Buckley Crist, a professor of materials engineering he picks out of the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute catalogue. Since the package is too big to fit in a mailbox, he places it in a parking lot near the science and technology buildings. A university police officer picks it up and suffers minor injuries.

ANGUISH

Lately I have been in contact with the Chairman of the local unit of Friends of the Earth with the idea of joining that organization—not because I think such organizations do any good, but because there might be a chance I could meet some people in that organization who would share my anti-technological views.

I still keep trying with faint hope of starting an anti-technological organization. Since I do well at most everything else, if it were not for my social disability I probably would have done well in attempting to start such an organization. Of course, the chances of success for such an organization are no doubt remote, but if there is any chance at all, I would seem to have lost it by my inability to be accepted by a group.

A month later Ted reads a governmental report on the political effectiveness of assassination. He excerpts it in his journal: Page 4.“A second category is assassination for the purpose of terrorizing and destroying the legitimacy of the ruling elite in order to effect substantial systemic or ideological change. Such assassinations may be directed against high government officials or against mid-level officials to undermine the effectiveness of the central government at the local or provincial level. Our studies show that this kind of assassination is effective in achieving the long-range goals sought. Once a terrorist group is well-established, the only effective response is either counterterror or agreement to the basic demands of the terrorists.”

The above conclusions sound hopeful to me, because, if correct, they seem to suggest that a comparatively small group of people can change the course of history if sufficiently determined. But I wouldn’t be too confident about this without examining the evidence on which they (the authors) base their conclusions.

Still, if only I could start an anti-technological terrorist group! Any kind of effective anti-technological group! But that would require meeting a lot of people, picking out the right ones, and filling them with enthusiasm for the idea; that is, it would require considerable social skill—and the social area is my one weak point.

Ted commits himself to begin a terrorist campaign next summer. In the meantime, he takes a temporary job to earn money. He likes the people he works with; and they offer him a permanent job.

Yesterday, instead of going to work, I phoned in and said I was quitting. To tell the truth, I feel heartsick having had to turn down that job. When Joe offered me that job, in view of the nature of the job and what he said about it, his offer seemed to imply not only an appreciation of my ability, but also an acceptance of my personality. Thus, the biggest reason I feel so very badly about having to turn down the job is that I feel as if I have turned down an offer of friendship. It seems to me that working people are more tolerant of individual differences than intellectuals are. I have met far more personalities for whom I have some respect among the working people than among intellectuals or bourgeois types.

In quitting I feel as if I have signed my own death-warrant. Drifting along indefinitely in that job would have been the path of least resistance—and that, in a way, was the only thing remaining between me and the finish of everything. I am feeling so much grief and bitterness over it, that I conclude that the social rejection I’ve endured has cut much deeper than I formerly realized.

REVOLUTION

On May 9, 1979 Ted begins a terror campaign, placing a bomb in a room at the North-Western University Technological Institute; a graduate student is injured. He mails 4 more bombs by 1982; 3 of them cause injuries.

The FBI forms the Unabom Task Force.

The fifth of August I began a hike to the east. Walking across the hillsides on my way there, I saw down below me a new road that had not been there previously. This made me feel a little sick. Nevertheless, I went on to the plateau.

What I found there broke my heart. The plateau was criss-crossed with new roads, broad and well-made for roads of that kind. The plateau is ruined forever.

The only thing that could save it now would be the collapse of the technological society. I couldn’t bear it.

This day of 1983 Ted decides that rather than acquiring more wilderness skills, he will commit himself fully to attacking the system as a whole. He mails 5 bombs 1983–1987, injuring 4 and killing 1 person, a computer store owner. He claims the bombings in a 1985 letter to the San Francisco examiner:

“The aim of the Freedom Club is the complete and permanent destruction of modern industrial society in every part of the world.”

The FBI chooses not to reveal this message to the public.

Ted takes a hiatus 1987–1993 to design smaller, more powerful bombs. He then resumes with highly-targeted assassinations of prominent researchers and political actors, injuring a leading computer scientist[1] and injuring a genetic researcher[2]; killing a public relations executive[3] and killing the president of the California logging industry lobby[4].

On the day he mails the last bomb—April 20, 1995—he sends a letter to The New York Times (implicitly, the FBI) offering to negotiate an agreement.

[1] David Gelernter: Yale University computer scientist; author of Mirror Worlds: Or: The Day Software Puts the Universe in a Shoebox... How It Will Happen and What it Will Mean. “Reality will be replaced gradually, piece by piece, by a software imitation; we will live inside the imitation; and the surprising thing is— this will be a great humanistic advance.”

[2] Charles Epstein: Medical geneticist at University of California San Francisco. At the same time, Ted sent warning letters to Nobel-Prize-winning gene-splicing pioneers, Phillip Sharp and Richard Roberts. Roberts later developed and advocated global use of GMOs.

[3] Thomas Mosser: Burson Marsteller executive. Ted had read that B-M had defended Exxon after the 1989 Exxon Valdez spilled ten million gallons of crude oil into Prince William Sound. B-M had advised but not handled the account. B-M specialized in “reputation repair” for corporations and states causing catastrophic environmental harms or human rights abuses.

[4] Gilbert Murray: President of the lumber lobby group, the California Forestry Association.

Contact: Lydia Eccles, UniversalAliens@Hotmail.com