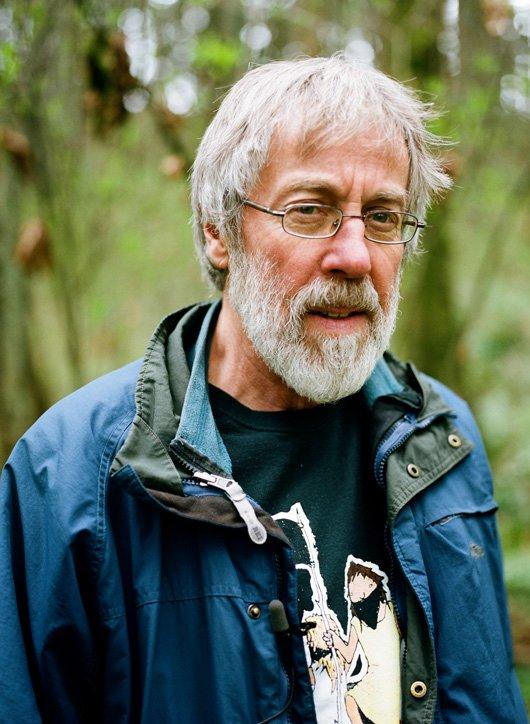

John Zerzan, Derrick Jensen, Carson Wright, Andony Melathopoulos and Brian Tokar

Platypus Society interviews with John Zerzan & Derrick Jensen

April 2020

Reflections on Seattle 1999: An interview with John Zerzan

“The Left has never been against civilization”: An interview with Derrick Jensen

Response to Platypus’ interviews with J. Zerzan and D. Jensen

Reflections on Seattle 1999: An interview with John Zerzan

Andony Melathopoulos

The following interview took place January 5th 2020, Eugene, Oregon.

Andony Melathopoulos: What were your impressions of how the 20th anniversary of the anti-WTO protests in Seattle have been received? How did people remember it?

John Zerzan: The anti-globalization movement still resonates with people. I was at an event in Eugene, Oregon that was completely packed. People there either remembered it fondly or were compelled to know what it was all about. I certainly heard regrets that we don’t have anything like the anti-globalization movement today. There is broad agreement that that movement fizzled out with 9/11. I wonder sometimes whether the energy behind that movement might have continued to grow without 9/11, or whether it had already reached its natural cycle. But the concerns of the movement are even more relevant today. Even more so than in 1999, the bloom had rubbed off the rose of technology. I was just reading the Sunday New York Times and there were several articles about how cyberspace has disappointed: it has failed at connecting and empowering people. People are questioning assumptions of progress and that was certainly part of Seattle.

AM: You have been an anarchist since the 1960s New Left. If you were to look back, how would you describe your development as an anarchist in the years leading up to 1999?

JZ: In the 1960s I was working for the Department of Social Services in San Francisco and we had formed an independent union; the standard union was so corrupt and do-nothing that we were forced to. We quickly discovered that organized labor was more hostile to us than management. So I was forced to rethink how unions functioned. I went back historically to see how unions developed; was it very radical in the beginning and just tended to become bureaucratic, or what? That led me to explore technology, because the first unions were associated with textile production in England which coincided with the Luddite movement. My personal experience with unions and my scholarly work led me to think that the whole factory mode, the whole industrial model, was severely disciplinary, sort of in the Foucauldian sense. It was not just an economic system, but a carceral structure, a prison. In this respect, Marx was completely wrong about industrialization: it didn’t radicalize people, it domesticated them and took away their energy and their time.

I began to think the problem wasn’t restricted to the Industrial Revolution, but situated at the very roots of civilization, going back to domestication of plants and animals in settled agriculture. I discovered the anthropological basis for this position, quite by accident, in the 1980s. One thing, literally, led to another. Since there wasn’t anything going on in the 1980s—there were no social movements—I had time to think and pursue these problems. But by the 1990s, I was seeing the same kind of ideas appearing elsewhere. The Unabomber is an obvious example of this kind of civilizational critique.

Some people responded to growing social problems by returning to the 1960s. Stewart Brand, for example, had the illusions that we could better harness the potential of new technologies like personal computers and use it to connect people democratically. He literally posed the problem as “technology, yes or no,” and he answered with a resounding “yes.” Some of us said “no, that’s not the right answer, who can honestly express that kind of optimism anymore?” I mean, the amount of depression and suicide and daily mass shootings, it’s a catastrophe. I’m not saying it’s all because of technology, but it’s certainly the fabric that surrounds all these problems.

To be clear, in the 1960s we didn’t even think about these issues. We were talking about ending the Vietnam War and racism. The 1960s ended with a sudden collapse of the movement. We were left wondering, “what was that all about, what were we missing, why did it fail?” That was another impetus for rethinking things.

AM: But as you were saying, the rethinking took place in isolation in the 1970s, but then by the 1980s you discovered you were not alone.

JZ: Exactly. Freddie Perlman, for example, became an inspiration for us, as did thinkers from Europe like Jacques Ellul. The theory journal Telos was translating work into English, making it accessible to us for the first time. Also, influential was Fifth Estate magazine based in Detroit. There was something clearly in the air about a deeper questioning along the lines I was thinking. It was in different languages, using different terms, but really was the same thing.

AM: Would you characterize what was bubbling up as a rejection of the Left as it had been traditionally defined, a sense of disaffection with the New Left?

JZ: Well, I don’t know. I might attribute it more to what was happening in anthropology in the 1960s and 1970s. We were realizing there was something utopian about humanity pre-civilization and pre-domestication. And many of the thinkers that influenced us in this respect were Marxists like Stanley Diamond. They had the intellectual honesty to put forward that the answer isn’t industry and it isn’t more and more machines. Another anthropologist who comes to mind is Marshall Sahlins and his idea that the original affluent society was hunter-gatherer.

Anthropology got us thinking about radical decentralization. We recognized that community is gone, it’s been swallowed by mass society, and that what we have to have is a face-to-face society. A society of 50 or 100 people, not 300 million people with one ruler. We didn’t see this as a utopian pipe dream, but as something anthropology was validating. That was thrilling.

AM: But you also mentioned that these discontents were not only being expressed in theory, but that they reflected changes in society. Before the interview you mentioned that in the 1980s people of my generation (Generation X) were particularly receptive to these ideas, for example, in the form of intense interest in the Unabomber (Ted Kaczynski) and his essay Industrial Society and Its Future.

JZ: Yes, it was striking the amount of connection with what Ted was trying to say. Certainly, I would encounter young Eugene punks who were very engaged, organizing benefit events for him, for example. But the appeal was broader than that. It was mainstream. By the early 1990s there was a general sense that all was not right in terms of faith in technology.

AM: What about the rising environmental activism in the 1980s and 1990s? Here in the Pacific Northwest it seemed that this was also the era of Earth First and the blockades of logging roads.

JZ: You’re very right. Earth First’s journal office was actually located here in Eugene in the late 1990s. There was also the Earth Liberation Front (ELF) and the arson of a new ski resort in Vale, Colorado in 1998. At the time you could ask people “was that cool, are you down with that?” and it would tell you where people stood. The Pacific Northwest was the place where you’d find people setting log trucks on fire, blocking logging roads and camping in tree canopies to prevent logging.

AM: Would you agree that this activism seems to anticipate the black bloc in Seattle?

JZ: I think some of the stakes were the same. I think of the case of Jeff Luers. He was a tree-sit person who transitioned to black bloc-type militancy in the streets of Eugene. He was arrested with one other guy and he got 22 years at the age of 22 for arson at a car lot. Then, when Jeff was in custody, there was a bigger arson at the same car lot that burned something like 30 SUVs. The powers that be wanted to make a lesson out of him. When you start doing shit like that, that’s for real. The reactions and the repression inevitably follow. I mean, it can be exhilarating like nothing you’ve experienced before and/or it can mean kids go to prison for years and years. They had to be ready for that. It was an amazing time.

AM: Looking back again to the 1960s, do you see these kinds of tactics as being a break from something like the civil rights movement, or in continuity with it?

JZ: Oh I don’t know. I do think the growth of movements is always a surprise. I mean take the 1960s. Until the mid-1960s it seemed like a continuity of the 1950s. There was nothing going on. There were Freedom Riders, there were civil rights, certainly. I don’t discount that. But I mean in the general white society little or nothing was happening. You’ve got moronic TV, you’ve got massive consumerism; “buy, buy, buy,” the economy is raging forward, everybody can buy a car or two cars. There was no sign of what was about to break out. It broke out all of a sudden, starting at the University of Berkeley in the fall of 1964. I mean, who knew? The Marxists were looking for the collapse of the economy, for the downturn, but there was no downturn, the economy was growing and growing. I mean, you could get fired from someplace and go across the street and get another job. It wasn’t that “when people feel the squeeze they’re going to revolt.” In fact, it’s usually the other way around. People revolt when they have free time. Take, for example, Watts in 1965. It was not getting worse for people there, in fact it was probably a little better. At the time the Situationist International referred to it as the first rebellion in history “to justify itself with the argument that there was no air conditioning during a heat wave.”[1]

Marcuse’s One Dimensional Man in 1964 took a similarly pessimistic tone, suggesting that there may never be a revolution or serious resistance because people are lobotomized. And within months he was very happy to take it back because the 1960s happened, he was proven wrong.

AM: But was he? Earlier you mentioned that your experience of the 1960s was that the New Left ultimately became a form of accommodation, a way of fitting into society.

JZ: Well there you go, yes, at a greater depth, I would agree. Paul Picone wrote that the 1960s uprisings weren’t really that radical for those very reasons. When we took it up later we realized we didn’t go that far in the 1960s, we were engaged, but we realized there was so much we hadn’t thought of.

AM: The Frankfurt School in general was not optimistic about the 1960s, Marcuse notwithstanding.

JZ: Right. They were hoping for utopian currents to emerge, but they also detected authoritarian tendencies in the German Left, and there still are. It raises the issue of theory. Adorno was dealing with students who said they didn’t have time for theory, it was a time for action. They accused him of sitting in his ivory tower, of not being radical. But he insisted that theory is radical, you have to keep thinking, you have to keep deepening your questions. But there was so much impatience and passion and you can understand the sentiment that one could go on theorizing forever, but at some moment you have to act. That’s understandable too.

AM: Talking about critical theory makes me think of Rousseau and his critical engagement with the very modern preoccupation with the “state of nature.” I mean, clearly, no one in the medieval period was even thinking in terms of the “state of nature,” let alone trying to understand society in these terms. How do you think about it?

JZ: I think about this in terms of contending flows, the Enlightenment versus Romanticism. These are distinct. In hindsight, the Enlightenment has proved to be a failure. More science, more technology, there won’t be any more superstition; none of those things are true or have happened. It’s fashionable now to mock Romanticism. “Oh, that’s a bunch of noble savage stuff” is now the favorite slur of postmodernism. You can slur all you want but I always think that, while I don’t really know what noble means, I know what ignoble is, that’s what we’ve got, and postmodernism defends it.

I’ve tried to provoke postmodernists. It never happens because they’re too fucking cynical. They just laugh. They say: “let’s have a beer afterwards,” and I think if that was me being attacked, I’d try to defend my ideas. But you wouldn’t if you don’t have any values and don’t stand for anything.

AM: Postmodernism had its own war with Marxism.

JZ: Yes, that was perhaps the good thing about postmodernism. When it challenged the idea of a “grand narrative” it was talking about Marxism. They were active in routing out Marxism in the 1970s. It just disappeared in France afterward, and gradually that extended everywhere. But does that mean you just rule out any kind of grasp of the whole? Why would you throw everything out with the bathwater? I was a Marxist and now I’m not, I don’t take issue with that critique, but I disagree that after Marxism you can’t know anything. What you are left with is a deflection of any kind of standpoint at all. Then you’re absolutely helpless. Then you’ve got nothing. You don’t even go out and fight and lose. There is no fight.

AM: There seemed to be a renewed interest in democracy in the 1990s. I mean, one of the iconic images of the protests in Seattle was a massive banner with an arrow labelled “democracy” going in the opposite direction to an arrow labelled “WTO.” What did you make of this renewed enthusiasm for democracy?

JZ: As an anarchist, I don’t want democracy. I don’t want representative rule. If you want something different, ultimately, it’s not massified politics. We would need to get to a more face-to-face community. The demand for democracy, either from a small-d democrat or from the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), ends up in reformism, because it doesn’t lead to a radical break with society. You end up fighting over better health care or better government programs, rather than drawing attention to the chronic ill health in society.

AM: Anarchists in the 19th Century emphasized civil social action, independent of the state, the vehicle for transforming society. Is this more in line what you think is called for?

JZ: The Left qua the Left wouldn’t be the Left anymore if it began questioning its goals relative to social transformation. Its watchwords remain “smash the state” and “abolish capitalism.” Both are implausible in a modern world. You can’t smash the state. There is a need for all kinds of regulation and coordination. Call it what you want, but it’s still governmental. Abolishing capitalism is equally implausible. What does that even mean? It means people don’t get paid. How do you get rid of the commodity and wage labor in a modern world? The only way that those two things will be possible is to get rid of industrial society. Then you could have those things. But the Left has no interest in that goal. Chomsky just froths at the mouth when we point out that these goals weren’t even possible in the 1800s and how these goals have only grown more preposterous with time. These are just slogans. They have no meaning whatsoever. They don’t want to get rid of this world.

So, you can’t do without either the state or capitalism. You can say, you want a nicer form of capitalism. That was always a prominent feature of some currents of the anti-globalization movement and certainly the World Social Forum. They would say: “we want a bottom-up globalization, a people’s globalization, etc.” Maybe you have a leftist politician instead that doesn’t change things in a fundamental way. Some of us, however, were truly anti-globalization. We didn’t want a globalized world. We didn’t want an integrated world where everyone is plugged in.

AM: Your point about anti-globalization vs. alter-globalization is interesting in hindsight. Some might say that 1999 and 2019 bookend the discontents with globalization in different ways. Protesting the WTO was seen as a progressive cause in the 1990s. Only fringe conservatives like Pat Buchanan would agree and call the WTO an “embryonic monster.” But today it is conservatives who are calling for the renegotiation of global trade. Are you surprised by these developments?

JZ: I was having an exchange with Paul Kingsnorth in England. He was writing about Brexit and he was trying to remind people that maybe the upside of Brexit is you have more local control. Not that there was much of a radical edge to Brexit, but he was at least interested in exploring the possibilities within it. We actually don’t want to be part of this totalizing world, where you can’t get outside of it at all. I am not sure I agree with their arguments, but it is striking how some of these conservatives are, in a way, closer to where we’re at. Because what is the most reactionary position of all? It’s to go back to the Stone Age. I mean that’s, in a certain way, what we are talking about.

AM: It must be quite remarkable to you. People who would have been protesting against trade deals for 30 years are suddenly arguing for their continuance.

JZ: Yes and no. The term “globalization” was used in ways that were ultimately hard to pin down. Globalization meant many different things to different people. The current discontent around globalization should be an opportunity to be more specific. We should be listing down all the horrors associated with globalization. Why is the ocean full of plastic, and rising and warming? Everyone knows this is horrible at some level. But to connect the dots would mean imagining something quite different. In other words, connecting the dots is not the main problem. The main problem is inertia. I remember talking to this woman in Turkey and she recounted explaining primitivism to someone and finally he said “I think you’re exactly right and I agree with everything you said.” He continued “but you might as well argue against the sun coming up,” in other words, it has no meaning, there’s nothing behind it. That’s what we have to get over. Then we need to start thinking about 1999, or other possible ‘99s to shake things up.

AM: Regarding the return of 1999 in the 21st century, do you envision your ideas finding a hearing among a new generation?

JZ: I can only see small signs. There’s some new anarchist zines popping up just in the past few months, like Oak, Backwoods and Blackbird. But there are also signs that it is going in the opposite direction. Greta Thunberg, for example, is now a spokesperson for the Fourth Industrial Revolution. That’s unbelievable and is precisely against what she is talking about. I thought, “no, no, that can’t be right.”

But I think that people will start to say, “you know things are getting so bad, so much worse, are we going to keep swallowing these mainstream assumptions?” I can understand why they don’t want to become anarchists or primitivists, but at some point they should become skeptical of progressive illusions. I wouldn’t be surprised if there’s all kinds of DSA members who start to find us. I’ve talked to some that are very sympathetic to a green, primitivist, radical approach. They’re still in DSA simply because they don’t see anything else. But they are not going to go to their dying days worshiping Bernie. They might just as well hop off the train and join the revolution.

It doesn’t have to start out as anything radical. I mean, Paris 1968 started out as nothing but a campaign to modernize the university system. There was absolutely nothing radical about that, but as we know it just kept going, and kept bursting the bounds of that starting point. By the peak, ten million people were on strike and occupying their workplace. So you never know. It might start out as one thing, before growing into something else.| P

Transcribed by Andony Melathopoulos.

“The Left has never been against civilization”: An interview with Derrick Jensen

Carson Wright and Andony Melathopoulos

The following is an edited transcript of an interview with Derrick Jensen conducted on January 19th, 2020 by Carson Wright and Andony Melathopoulos of the Platypus Affiliated Society. Jensen is an anarchist and environmental activist, as well as a speaker and author of several books, including A Language Older Than Words and The Culture of Make Believe.

Carson Wright: How did you come to understand civilization as irredeemable? Who were your early influences?

Derrick Jensen: I came to understand civilizations as irredeemable through observing the real world far more than by reading books. A formative incident in my life was in second grade when they put in a subdivision right next to where I lived. I saw the meadowlarks, grasshoppers, garter snakes and cottonwood trees all disappear and become a neighborhood of white-box houses. I understood even then that if this keeps going on forever, these other creatures will run out of places to live. I recognized that the expansion of this culture comes at the expense of the non-human world. I understood that you can’t have infinite growth on a finite planet. By my late twenties and early thirties, when I was becoming an environmental activist, I realized that most activists had the same feeling, of hanging on by their fingernails to protect this or that piece of ground until civilization would collapse. It doesn’t take a cognitive giant to figure out that if you have uncountable salmon, then you count them and they’re in the millions and later they are in the hundreds of thousands or in the tens of thousands, that there is a clear trend towards species extinction. I’m actually pretty stunned that more people don’t recognize the pattern and the directions that this culture is going.

They say that one sign of intelligence is the ability to recognize patterns. Look at the pattern of the last 6,000 years. In Iraq, the cedar forests were so thick that the sunlight never touched the ground. The first written minutes of Western Civilization were of Gilgamesh deforesting the hills and valleys of Iraq to make a great city. North Africa was heavily forested, and they were cut down to make the Egyptian and Phoenician navies. Plato wrote about how deforestation was harming water quality in ancient Greece. This is the story of civilization.

From the patterns of history, I realized civilization was harmful to the planet, but I learned it was irredeemable from a combination of things. The first is the realization that most humans don’t feel that non-humans matter in the slightest. Most people believe that the economic system is more important than life on the planet. This extends to a mainstream perspective that emerged in the 1980s and 1990s about “balancing the economic system and the environment.” What wasn’t recognized is how such a statement implies the environment and the economic system are antithetical: why else would you have to come up with rhetoric about balancing them? An economic system in opposition to the natural world ends up destroying the natural world.

The irredeemability of civilization stems from the way in which recognition of its destructiveness is never fully registered. I’ve written extensively about my childhood abuse. Recovering from abuse is a hard and difficult process that most people don’t go through. If it is that difficult for an individual — for one person — then I can’t imagine a circumstance in which the entire civilization could recognize its behavior, particularly when individuals are financially rewarded for environmentally destructive behavior.

There is also just plain stupidity. I think of the Gordon Gekko character in Oliver Stone’s 1987 movie Wall Street. Stone meant this to be an evil character, and he delivers a speech about how greed is good — but most people missed the point, and it became a motto for Wall Street. Or Sam Peckinpah’s Wild Bunch (1969); Peckinpah made the film because he was disgusted with how sanitized the violence was in Westerns. He intended to rub people’s faces in the violence and show that the people who are doing this violence are not good people. But the audience missed the point and said, “Wow, that’s really great, it’s so violent, it’s so groovy.”

It’s not just stupid people. People can be very smart as individuals, but collectively we are stupid. Postmodernism is a case in point. It starts with a great idea, that we are influenced by the stories we’re told and the stories we’re told are influenced by history. It begins with the recognition that history is told by the winners and that the history we were taught through the 1940s, 50s and 60s was that manifest destiny is good, civilization is good, expanding humanity is good. Exemplary is the 1962 film How the West Was Won. It’s extraordinary in how it regards the building of dams and expansion of agriculture as simply great. Postmodernism starts with the insight that such a story is influenced by who has won, which is great, but then it draws the conclusion that nothing is real and there are only stories.

Peggy Reeves Sanday wrote on why there are rape-prone versus rape-free cultures. She noted that there were characteristics that were common among high-rape cultures, such as the extent of militarization, the value of women, if there is a history of ecological dislocation over the last several hundred years. But ecological dislocation has been roundly a feature of this culture for at least the last several hundred years. It would take a few hundred years for a society to metabolize trauma and to become no longer a harmful culture. Social change can’t take place overnight; it can only occur over generations. Take, for example, the end of slavery in the U.S. with the American Civil War. The war didn’t change the underlying contempt for black people. So, you stop chattel slavery, and it leads to new forms of oppression, like Jim Crow. Then that becomes outmoded, and then you come up with new mechanisms of oppression.

But the biggest reason civilization is irredeemable is that it is based functionally — not just psychologically or socially — on dismantling the ecological infrastructure of the planet and converting it into a scheme of humans, their pets, their livestock and their machines. This is the theme that I explored in my book Endgame (2006), which was a different tact of my arguments against civilization compared to A Language Older than Words (2000) or The Culture of Make Believe (2003).

There were thinkers who influenced me along the way. Neil Evernden and John Livingtson were big influences on me. One person who should have been a big influence on me, but I didn’t read him until later, was Daniel Quinn. Had I read him 10 years earlier than I did, he would have had a big influence on me. Edward Abbey was the same way.

Andony Melathopoulos: As you point out, in the 1950s, to regular people, taking a forest and turning it into homes appeared as progress. It seems this generation didn’t have the same concerns as your generation did. How do you account for your perspective on history?

DJ: On one level, I disagree with you, in that perspectives like mine predate my generation. Like I said, Plato was complaining about deforestation harming water quality a couple thousand years ago. There were similar perspectives in ancient Rome. Turning to the U.S., there were a number of figures in the 19th Century, like George Perkins Marsh, who wrote about how his culture was inherently destructive. Or someone like Henry David Thoreau. Before WWII, there were figures like John Muir and Frederick W. Turner. There were people who wrote on the collapse of the Columbia River salmon populations even before the dams went in because of the canning factories.

But there is also something about the period after the 1950s. Ecological concern was noticeable before that time. My great grandmother grew up in Nebraska. She would get nervous every time there were thunderstorms because she was afraid it would spook the bison and they would stampede and run over the top of the sod house, causing it to collapse. But she would say to my mom growing up in the 1930s that things have changed more in the last five years than they’ve changed in the rest of her life put together.

So, what changed? Joseph Campbell once wrote that when a local mythology works, it brings you a sense of meaning in your life. So, if the signs and symbols of Catholicism work for you, then you have a couple-thousand-year path of meaning open to you. In the 1950s, the myth of capitalism and progress still worked for many people, laying out a path of meaning for them. On the other hand, if those signs no longer function, then you have to set out and find your own path, your own meaning, and that’s what Campbell called the Hero’s Journey. And the reason I bring him up, and the reason that he’s relevant to this conversation, is because yes, I agree that in the 30s and 40s the myth of progress was ascendant, and it worked for most people. And by the 50s and 60s, cracks emerged. People began abandoning the myth and searching for new meaning.

But the abandonment of myth can also lead to craziness. Joseph Tainter wrote that as a complex society starts to collapse, people hold on to whatever beliefs made the society grow in the first place. So, on Easter Island, as the society collapsed, people were still building stone heads. Something similar is at work when people turn their attention to solar and wind installations. What generated the problems we face in the first place is industrialization. The idea that we might overcome industrialization through more industrialization of the wind, oceans, deserts is absurd.

CW: Early theorists of social contract frequently took as their starting point humanity before civilization. Rousseau noted that “the philosophers who have inquired into the foundations of society have all felt the necessity of going back to a state of nature, but not one of them has got there.” Rousseau points out that all questions about the state of nature seem bound up with the question of what society is. Do you find an affinity with the critical tradition?

DJ: I’m not a fan of Rousseau. I don’t think there is a “state of nature,” by which I mean something very specific. Humans, like elephants, gorillas, hyenas and wolves, are social creatures. And we are taught how to be human. Being human is not, as Richard Dawkins asserts, that we are fundamentally selfish. Nor is it a matter of us being fundamentally social. Ruth Benedict explains the dichotomy of selfishness in her analysis of why some cultures are good and some cultures are bad; why some cultures are peaceful, take care of their women and children and others are warlike. Benedict discovered that good cultures recognize that people are both social and selfish, and they do away with the selfishness/altruism dichotomy by making those two the same, that is, by socially rewarding behavior that benefits the group as a whole and disallowing behavior that benefits the individual at the expense of the group. So, if I go fishing and I share the salmon with everybody, and they praise me, it makes me want to do it again. But it would be socially disallowed for me to catch and hoard the salmon and try to sell it back to the group. There were some tribes in the Pacific Northwest, in fact, which would employ shaming polls which would be put outside someone’s home if they were being a jerk. A bad culture, by contrast, would socially reward behavior that benefits the individual at the expense of the group, which turns everybody into competitors at all times for whatever resources.

That is to say, that I think humans are really plastic. John Livingston once said something that I originally disagreed with. He said that the problem of humanity is that we substituted ideology for instinct. I disagreed with it at first, because it felt to me like he was saying that elephants are only instinctual and don’t have societies, which is not true. But then I later understood what he was getting at. He meant that ideology is unreliable because if you have a bad ideology, it can cause you to act destructively on society and on the natural world. The ideology of the last 6,000 years asserts that non-humans don’t exist as subjective beings and that it’s acceptable for humans to conquer everybody. If nature made a mistake, it was making us dependent on ideology instead of insulin.

That is why I don’t like Rousseau. I don’t think there is a state of nature, where humans are perfect. I believe the Tolowa, on whose land I now live, were sustainable, not because they were a primitive people who didn’t question anything, but because they had lived on this land for thousands of years and learned what they can and can’t do.

AM: You seem to use culture and civilization interchangeably. I am not sure what you actually mean when you say civilization is irredeemable because presumably some of these cultures were good and bad. When in this history does humanity’s path become irredeemable?

DJ: I use civilization in a very specific way; it’s a way of life characterized by the growth of cities. The root of the word “civilization” comes from the Latin civitas, which literally means “state” or “city.” A city is defined as a people living in numbers large enough to require the importation of resources. And in that situation, a few things happen. As soon as your way of life requires importation of resources, your way of life can never be sustainable because it means you’ve denuded the landscape of that particular resource, and you now require its importation as your city grows. All cities require a larger land base from which they steal. I mean think about New York City: where do they get their wood? Where do they get their food? Where do they get their bricks?

AM: Are you saying there is nothing qualitatively different between New York versus a city in Crete during the time of the Minoans? Are they just the same thing, just on different scales?

DJ: In my book The Culture of Make Believe, I made the point that every holocaust is different. We can talk about the capital ‘H’ Holocaust of the Jews in Germany, and that is different from what David Stannard describes as the American holocaust of American Indians. They have some things in common, but they’re different, and those two are both different than the Armenian genocide, and those are all different than the Rwandan genocide, but they still share things in common. So, I would not say that the Minoan cities are the same as New York, but they share some things, one being that both are unsustainable. No city has ever been sustainable. Secondly, in addition to not being sustainable, cities must be based on violence. If you need resources from some other city, and they won’t trade for it, you are going to take it.

I don’t know why the first cities arose. But what I am clear on is when you have a form of humanity based on agriculture and cities, you have a competitive advantage over your neighbors, because you have converted your land base into humans, into machinery, into weapons of war. Once you’ve overshot your own carrying capacity, you can either collapse — voluntarily or not — or you can expand. Usually, civilizations have chosen to expand. One that didn’t — and we’re not sure why — were the Mayans.

CW: How do you regard the history of the Left? Was it ever concerned with overcoming 6,000 years of civilization, or was the Left always about deepening civilization?

DJ: It depends on how we define the Left. I really like Dalton Trumbo’s 1938 novel Johnny Got His Gun. It’s about a soldier in WWI who wakes up in the hospital and finds out that he is blind, and he can’t speak; basically, his mouth is gone. There’s a beautiful passage near the end of the book where he’s talking about workers getting together. It’s all very moving, but he also talks about how “we are the people who are stringing the high-power lines, etc.” The point being that he is buying into the whole myth of progress. I think, in so far as he is representative of the Left, then yes, I don’t think it’s about overcoming civilization. Part of the problem is that the Left reflects the culture. It is generally human supremacist and sees humans as the only ones that matter. And it’s a problem going as far back as the origins of the Left, and it continues to this day.

I would not say that the Left has been entirely unconcerned with the natural world. But I might characterize the Left’s concern falling along the spectrum of shallow ecology versus deep ecology. Shallow ecology is the idea that we can protect places without actually going after the system itself or without actually going after the underlying philosophies of the entire culture. There are a lot of people who do really good work who are shallow ecologists. I don’t want to devalue their work.

Deep ecology, which I belong to, would assert that while good work is necessary, it won’t stop the destruction of the planet. This split does harken back to a debate that has been going on for 130 years now, exemplified by the debates between Gifford Pinchot and John Muir. Where John Muir was protecting wildness for wildness’s sake, Gifford Pinchot was focused on protecting the resources for human use into the future. I don’t know Pinchot’s political positions, but I’m guessing he would fall within the sort of traditional Left.

I am not sure I can defend this position, but it seems like the traditional Left would overlap with Pinchot’s position, while the only ones who still follow John Muir’s side of the debate are the “looney” Left, in which I would include myself. I don’t actually mean we’re lunatics but that we are not taken seriously.

AM: Putting concern for the natural world to one side, what about civilization? Has the Left ever been about getting beyond civilization?

DJ: Let’s presume that the Left is defined by its being anti-capitalist. So, if we presume that Marxism is leftist, it was not traditionally against industrialism. On that level, I would say, no, the Left has never been against civilization.

CW: You have recently characterized the contemporary Left as “regressive.” When and why did the Left become regressive?

DJ: I think we’re in the midst of a collapse of civilization, and we’re definitely in the midst of the end of the American empire. And when empires start to fail, a lot of people get really crazy. In The Culture of Make Believe, I predicted the rise of the Tea Party. I recognized that in a system based on competition and where people identify with the system, when times get tough, they wouldn’t blame the system, but instead, they would indicate it’s the damn Mexicans’ fault or the damn black people’s fault or the damn women’s fault or some other group. The thing that I didn’t predict was that the Left would go insane in its own way. I anticipated the rise of an authoritarian Right, but not authoritarianism more generally, to which the Left is not immune. The collapse of empire results in increased insecurity and the demand for stability. The cliché about Mussolini is that he made the trains run on time, that he brought about stability.

CW: It’s been 20 years since the anti-WTO protests in Seattle. It seems like there was a new wave of Green anarchism that came in the wake of the protests. How would you assess the legacy of this green anarchism of the late 1990s?

DJ: I mean did the anti-WTO protests accomplish anything in the real world? Did they even slow globalization? Not really. In my book Endgame, I wrote positively about the accomplishments of the anti-WTO moment, but I have since come to reassess some of the whole black bloc — now antifa — stuff.

I agreed on one point with the black bloc tactics at the anti-WTO that so often those protests had been all about “speaking truth to power,” but they were effectively symbolic. I remember reading a veteran leftist who pointed out that the anti-war protest in the United States ended the war. And I was like, “Sure, they helped, but what really ended the war was Vietnamese people dying and fighting.”

The one thing I liked about the black bloc actions is that they recognized that the protests were merely symbolic, but two problems I have with the black bloc, and now antifa, is that they were very clear that their primary enemy was not the state. The primary enemy was the liberals who were protesting. The other problem was that their actions were equally symbolic. When they would argue that by breaking windows they would shatter the hold that capitalism has over everybody, it was basically magic. If we break it, they will come.

If the liberals want to speak “truth to power,” the black bloc wants to raise their middle finger to those in power. Both are symbolic. What I’m interested in is decisive attacks on infrastructure. When the black bloc started in the 1980s, there were some groups that were able to take over entire parts of communities. There were 10,000 of them in Germany, and they would drive the police out of a part of the city. And what would they do then? They would loot and burn. I look at that and think, you have 10,000 people who can actually take over a city, and that’s the damage that you do the capitalism: you burn a few stores and loots some TVs?

AM: I am not sure I understand what you mean about “decisive attacks on infrastructure?” Was the problem with the black bloc more than just the means they employed? Do you believe they focused on the wrong ends?

DJ: Not just the ends, but primarily their tactics. Anarchists first started turning on me when I began advocating for different tactics, specifically organized resistance. Organized resistance, according to some anarchists, is Stalinist and cult-like. Chaz Bufe ran into this in the late 1980s. He had an essay titled “Listen, Anarchist!”[2] where he points out that insurrectionist and individualist currents in anarchism were undermining it.

The problem in anarchism goes back to a rift that emerged 2,000 years ago. The rift is between those who understand that laws are made primarily by and for the wealthy and that humans can govern ourselves without the need for county commissioners. That is one set of anarchists, in which I would count myself, Ed Abby and, frankly, most of traditional anarchism. This current is characterized by a phrase Chaz Bufe uses: it’s a form of anarchism concerned not whether there should be organization but rather how things should be organized.

The other half of anarchism is characterized by those who believe that because those in power make laws that primarily benefit them, all social restrictions are inherently oppressive, and we should break every social restriction. This position is exemplified by an experience I had. I was giving a talk, and John Zerzan was in the audience. I was going on about how laws are made by and for the wealthy, and then I said that that doesn’t mean I have a problem with laws against rape, and he took strong issue with that position. Frankly, I think this current is destroying anarchism. Because, how are you ever going to confront the state, with all of its power, if you can’t organize in groups larger than six?

I was reading this thing a couple years ago about moving troops. It’s a real skill, and this is what master sergeants do, get troops moving without having a traffic jam. I mean, it just stuns me that anarchists think they can take on the state with its tremendous levels of organization and its firepower without organizing.

AM: What would be the ends of such an organization?

DJ: What I want to achieve is, I want to live in a world that has more wild salmon every year than the year before and has more migratory songbirds etc. So, what that means is, the dams need to be removed, industrial logging has to stop, industrial fishing has to stop, global warming has to be stopped. And how do we do that?

If I was made dictator, for example, I would not take out every dam tomorrow. I recognize that this whole system is based on subsidies, and I would change the subsidies right now. The world’s commercial fishing fleets, for example, are subsidized at a greater value than its entire catch. In the Pacific Northwest, activists have told me that counties want increased logging because that’s where they make the money for their schools and for their infrastructure. We should hire these same people who right now are cutting trees down for us to instead reforest and to instead go in and destroy old mining roads and to take out dams.

Chris Hedges says that those in power determine the terms of resistance, because if they will allow non-violent resistance, then that’s what happens. And if they don’t allow it, then it moves up the scale. It’s the same thing as the JFK quote, “those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable.”

What I want is for there to be more wild salmon every year. And I don’t really care how we get there. I don’t care if it’s because companies and governmental entities are behind it, or if the county or state government does it, or if a dam comes down because of an earthquake or somebody blows it up. It doesn’t matter to me. I just want for the dam to be gone so the salmon can come back.

CW: Do you see the currents and trends in environmentalism changing from the 1980s and 1990s?

Environmentalism in the 1980s and early 1990s was about saving wild spaces and wild beings, and that has changed, in great measure because of climate change activism. People like Bill McKibben and Naomi Klein are pushing relentlessly for wind and solar, but they are explicit that what they’re trying to save is this culture and this way of life and not the natural world. Naomi Klein has said explicitly that the polar bears don’t do it for her.

Environmentalism has really been captured over the last decade by the “sustainability” movement, which has really been about sustaining this destructive culture a little bit longer, just powering it in different ways. A great example of that is you can have 100,000 people march on the streets of New York or Paris, and if you ask them why they’re marching, they’ll say to save the planet, and if you ask them what their demands are, they will say they want subsidies for wind and solar. Which is extraordinary; the environmental movement has been turned into the lobbying arm for a sector of industrial capitalism.

With Extinction Rebellion, I see a movement back to a biocentric perspective that does care about the extinction that is going on all around us. I hope this signals a pendulum swing back towards a focus on the natural world, but as I said earlier about cultural make-believe, as this culture continues to collapse, there will be more and more people who simply want to maintain the culture at literally any cost. Over the next little bit, splits will become more apparent between those whose loyalty is to the natural world and those whose loyalty is to the dominant system.| P

Response to Platypus’ interviews with J. Zerzan and D. Jensen

Brian Tokar

Brian Tokar is an activist and author, a lecturer in Environmental Studies at the University of Vermont, and an active board member of 350Vermont as well as the Institute for Social Ecology (social-ecology.org), where he served as Director from 2008–2015. He has written and edited seven books on environmental issues and movements, including Toward Climate Justice: Perspectives on the Climate Crisis and Social Change (2010, Revised 2014) and a brand new collection, Climate Justice and Community Renewal: Resistance and Grassroots Solutions, to be published this spring by Routledge.

I APPROACHED PLATYPUS’ RECENT INTERVIEWS with John Zerzan and Derrick Jensen with much interest. I was especially curious to see if either had modified their views in any way given the recent appropriation of nihilistic environmental rhetoric by various white nationalists and self-proclaimed eco-fascists, including last year’s mass shooters in El Paso and New Zealand. It appears, however, that their basic positions have not changed at all.

Zerzan and Jensen became icons of radical environmentalism during the post-Seattle/WTO era, and both still apparently believe that human civilization is inherently at odds with personal self-realization and the protection of natural biodiversity. Today, with both the climate crisis and our response to right wing nationalism demanding rising levels of human solidarity and identification with marginalized people, such perspectives appear even more self-defeating than they were 20–30 years ago. Both interviews reflect a mythologized and disturbingly linear view of human cultural evolution, elevate acts of individual rebellion over the development of popular social movements, largely dismiss the experiences of the victims of contemporary capitalism, and both writers still appear to view their own perspectives as the only truly radical alternative to status-quo environmentalism.

The opening part of Zerzan’s interview references his important early writings on the nature of work under capitalism, which helped invigorate an increasingly self-aware post-sixties rebellion against the capitalist workplace. He helped contextualize a rising anti-authoritarian response to Marxist glorifications of the workplace as the primary locus of class struggle, a response that led to an impressive outpouring of literary, cultural and political expressions, most notably in the emerging high-tech workplaces of that era. However Zerzan never fully embraced the historical critiques of technology and its social matrix (a term from Murray Bookchin’s work) that were emerging at the same time. Historians of technology like Langdon Winner and David Noble offered a considerably more nuanced view of the course of technological developments that advanced managerial control over the workplace, from agrarian times to the rise of technology-based industries in the early 20th century.

Zerzan’s interview suggests that the social movements of the 1980s — against imperialist war, widening habitat destruction, and environmental racism, to cite a few examples — largely passed him by. Instead, he began a course of research and writing that helped spark the emergence of a popular “neoprimitivism” that captured the imaginations of many young anarchists during the Seattle era and beyond. Zerzan’s work drew upon many of the same path-breaking anthropologists whose work had been utilized by the pioneering social ecologist Murray Bookchin — scholars like Stanley Diamond, Paul Radin and Marshall Sahlins. But while Bookchin and his colleagues advanced the view that egalitarian social structures among preliterate peoples suggested the potential for a more profound social freedom that could enlarge the scope of human possibilities, Zerzan had a rather different interpretation. He and his followers largely opted for nostalgia, arguing that the emergence of civilization and “symbolic culture” was a kind of evolutionary tipping point that led to widespread domination, warfare, ideologies of control, and a dramatic curtailing of human possibilities. Rather than theorizing a dialectical tension between the historical legacies of domination and freedom, as Bookchin had in his 1982 magnum opus, The Ecology of Freedom, Zerzan’s recourse was to look backward, reject civilization, and urge young radicals to withdraw into communities of like-minded individuals to try to attack “the machine.” So in the late 1990s we had the “black bloc,” the Earth Liberation Front, and other similar circles of often self-isolating militants, tendencies that expressed some admirable qualities but ultimately proved more successful at enabling authorities to rationalize heightened repression than developing movements to bring down the system.

Since the 1980s, we have seen a couple of generations of radical anthropologists advance an increasingly complex view of human evolution and human potentialities. Feminist anthropologists have shattered essentialist views of traditional gender roles, citing examples of cultures that radically defy all the usual assumptions. Two recent review articles by David Wengrow and David Graeber[3] challenge all conventional notions of a linear human history, especially the widespread environmentalist view (dating back to Rousseau and more recently popularized through the novels of Daniel Quinn, who is cited in Jensen’s interview) that the emergence of agriculture and cities was singularly linked to alienation from non-human nature and the rise of social domination. Wengrow and Graeber cite archeological evidence for highly stratified societies among some Paleolithic hunter-gatherers, patterns of seasonal fluidity between dispersed hunting bands and highly organized settlements, and radically egalitarian and economically redistributive lifeways among some early agriculturalists. If we consider the latest evidence, it appears that the potential for domination and freedom, for oppression and liberation, exists in nearly every era of human history.

Another significant clash between Zerzan’s outlook and that of social ecology is around the question of democracy. Zerzan equates democracy solely with the “massified” and highly manipulated forms of representative democracy that exist today in most countries, ignoring the parallel legacy of revolutionary direct democracy that traces its earliest historical roots to the ancient Athenian polis, which first clashed with the modern nation state during the Paris Commune of 1871 and now appears resurgent, from the horizontalist response to Argentina’s financial crisis in the early 2000s, to Occupy Wall Street and recent radical municipalist movements from Barcelona to Jackson, Mississippi and beyond. It’s not about empowering “leftist politicians,” as Zerzan suggests, but rather a movement from below that aims to replace top-down statecraft with a more genuine grassroots politics where local diversity flourishes and chains of solidarity unite communities in bottom-up confederations that reject provincialism, racism and the legacies of colonialism.

To fully actualize such an agenda may take generations, but what Zerzan offers instead appears to be largely rhetorical, and also self-contradictory. We “can’t smash the state,” but we can “get rid of industrial society.” We need “regulation and coordination,” but reject democratic governance and need to “go back to the stone age.” He rejects DSA, where a recently formed Libertarian Socialist Caucus is actively challenging the organization’s tendency to narrowly focus on electoral politics and reforming the Democratic Party, but embraces the Brexiteers’ far narrower vision of “local control” — a trajectory that has taken Paul Kingsnorth of the UK-based Dark Mountain Project from a thoughtful, literary-minded approach to questioning civilization toward an open embrace of ethnic nationalism.[4] All this inherently contradictory rhetoric is steering those drawn to it in some highly disturbing directions, as we will see.

If anything, Derek Jensen’s approach is even more subjective, more rhetorical, and more of a dead end. He shares Zerzan’s simplistic, linear understanding of human history and an idealized view of small bands of militant activists pushing beyond the limits of civilization. His work has reached a substantially larger popular audience than Zerzan’s, and for many years in the 1990s and early 2000s Jensen was by far the most popular writer on the anarchist/anti-authoritarian scene, a popularity that only began to wane when he embraced his partner Lierre Keith’s essentialist diatribes against transgender people and their increasing visibility in radical activist circles. Jensen extrapolates his personal history of childhood abuse toward a view that all organized society is inherently abusive, and has traveled across the country and beyond arguing that a collapse of civilization represents the only hope for preserving biodiversity and liberating humanity.

Jensen shares the view of many leading proponents of deep ecology that an undifferentiated humanity is to blame for environmental abuses and that the ideology of capitalism is merely an extension of human nature. For several prominent deep ecologists in the 1980s–90s, this led to a perverse and fundamentally racist cheerleading for famine and AIDS as vehicles for population control, and support for the militarization of national borders to protect “American wilderness.” Well-funded anti-immigrant political operatives in the early 2000s made several unsuccessful attempts to take over the national board of the Sierra Club, and today’s more overt ecofascists have made immigration control their proverbial line in the sand — with encouragement from several prominent deep ecologists.

For Jensen, rape culture, racism and other horrors are not the product of particular institutional arrangements and class dynamics, but simply products of human “stupidity” and “selfishness.” Abusive behavior is a given, and “industrialization” is the vehicle for spreading our civilization’s stupidity worldwide. Not only is the social matrix underlying technological development out of the picture, but also the specific history of capitalist industrialism, boosted by the expanding use of fossil fuels from the mid-19th century to the present. While scholars such as Andreas Malm and the members of the UK’s Corner House research group have carefully dissected the origins of these phenomena and the ways particular interests have exploited fossil-driven technologies to advance social control, Jensen simply blames us all. Yes, cities have become centers of resource extraction under capitalism, but they are also the places where per capita energy consumption is declining the most rapidly — especially outside of the wealthiest enclaves. Visionary architects and planners are exploring ways to make cities and neighborhoods more self-reliant and the expansion of urban agriculture is a worldwide phenomenon, mainly constrained by inflated land values and limited access to capital for those whose innovations will not help the rich keep accumulating more wealth. Following many deep ecologists, Jensen uses the language of “overshoot” and “carrying capacity” in a highly mechanistic way that blames victims more than perpetrators.

Typical of his voluminous writings, with their vast scope of unstated assumptions and selective research, Jensen here appears incapable of seeing beyond his personal biases. The founder and first director of the U.S. Forest Service, Gifford Pinchot, had a utilitarian outlook on resource use, so for Jensen he must have been a leftist. In reality, Pinchot was a scion of Phillips Exeter and Yale, and a conservationist firmly in the Teddy Roosevelt mold. He pushed for more systematic and scientific management of (recently stolen) U.S. public lands at a time when unregulated exploitation by timber and railroad interests was the norm. In ethical terms he indeed fell far short of his sometime-nemesis, the Sierra Club founder John Muir, but he also helped advance the science of forestry in ways that both accommodated and constrained corporate interests. Pinchot helped expand public ownership of forest lands at a time when Congress was pushing for privatization, and he later joined Roosevelt in founding the Progressive Party. A decade later, he was elected governor of Pennsylvania as a staunch supporter of Prohibition and a fiscal conservative.

Jensen is surely correct that there are authoritarian currents on the left as well as the right, but that is something that both anarchists and independent Marxists challenged throughout the 20th century, not a recent phenomenon that Jensen simply failed to predict. And while positioning himself as an advocate for “organizing,” Jensen continues to be dismissive of the actual social movements through which many people have been drawn to his work. He views current environmental campaigns as too focused on a bland “sustainability” (which they frequently are, especially in the movement’s most conventional institutional forms) and the 1990s-early 2000s antiglobalization/global justice movement as not having accomplished anything. In reality, opposition to the WTO and other global trade agreements helped radicalize an entire generation of critically-minded activists and also significantly constrained what once looked like an irreversible march toward corporate tyranny. While capitalist abuses continue on an ever-massive scale, the institutional means for sustaining those abuses and isolating them from public scrutiny and opposition are far less consolidated than the trajectory of the late nineties would have enabled. The WTO, IMF and other global financial institutions hold far less sway than they once did, and global elites may be more divided than at any time in recent memory, a factor that has always created openings for movements to develop further.

Popular resistance to expansion of fossil fuel infrastructure is at an all-time high, with hundreds of projects cancelled in recent years in the U.S. alone. The conscious linking of resistance and renewal, of what the French global justice campaigner Maxime Combes has described as blockadia and alternatiba,[5] has also helped reduce the hegemony of fossil fuel interests within the world of global finance. Is it happening fast enough to fend off the threat of global climate catastrophe and sustain the living ecosystems Jensen wishes us to identify more closely with? It’s hard to tell, and the answer could be no, but the alternative Jensen offers is a fantasy at best, and a recipe for the collective suicide and increased infiltration of dissenting forces at worst.

What Jensen refers to euphemistically in his interview as “decisive attacks on infrastructure” is described in considerable detail in the 2011 book, Deep Green Resistance, which he coauthored with Lierre Keith and Aric McBay. It is a work of adolescent fantasy disguised as political strategy, whereby a secretive alliance of underground cells and above-ground organizers simultaneously sabotages current infrastructure and prepares for a post-civilization future. Guided by a highly selective and thoroughly misleading discussion of the history of past militant movements, “DGR,” as it’s become known, will – in these authors’ view – simultaneously blow up power lines and bridges, create popular assemblies, grow organic gardens and run for political office. As far as I can tell, its main accomplishment in the 2010s was to make it easier for authorities to entrap naïve young militants in various ill-fated schemes to sabotage public infrastructure. When the Earth First! Journal (soon to celebrate its 30th anniversary) published a supplement featuring DGR a few years ago, the ‘next steps’ section mainly featured a list of Facebook pages.

Perhaps the most important lesson of the last 150 years of anti-authoritarian political theory and praxis is the inseparability of ends and means, something Jensen demonstrates a flagrant disregard for. He fantasizes about policy measures he’d implement “if I was made dictator” (by whom??) and insists he ‘doesn’t really care’ how we accomplish goals such as enhancing wild salmon populations. But history shows that liberatory ends can only be achieved by liberatory means. Most likely that means a diverse and widely transparent movement-of-movements that aims to overturn the tyranny of capital, advances genuine democratization, and creates new economic and political structures that value cooperation over competition and the integrity of living ecosystems and diverse human cultures over the narrow interests of current elites.

An understanding of the inseparability of means and ends — and of the ties that bind ecodefense to human liberation — is also necessary to firmly distance our movements from the tide of racism and overt ecofascism that has surfaced in recent years. In a recent book chapter, social ecologist Blair Taylor cites numerous ‘alt-right’ commentators and organizers who have sought to embed ecological themes in their resolutely white supremacist discourse. The Pacific Northwest of the U.S., along with several northern European countries, is a center for this kind of activity, and ‘green anarchist’ themes, including those advanced by Zerzan and Jensen, are reported to be very popular within this milieu. Zerzan affirms his affinity for the “Unabomber,” Ted Kaczynski, who was celebrated in a 2013 Orion magazine essay by Paul Kingsnorth and has also become an iconic figure in some of the most violent white supremacist circles. Although he has criticized white nationalist tendencies among some of his readers, Zerzan has published several books through an outfit called Feral House that markets heavily to skinheads and conspiracists, and carries at least a few overtly Nazi titles. Taylor cites the cases of three self-identified “green anarchists” who have turned toward an explicitly fascist ideology while in prison, and similar cases have been discussed in the pages of the Earth First! Journal. He concludes that

Green and primitivist anarchism have proven compatible with the ecofascist right because they share significant philosophical and political terrain, including ecological antimodernism, civilizational decline narratives, blood and soil sympathies, and hostility towards the left.[6]

Of course there is a long history of right wing currents in ecological thought, starting with the coinage of the word “ecology” by the 19th century German naturalist Ernst Haeckel, whose retrograde racialist views were adopted by prominent Nazi ideologues. Early Social Darwinists like Herbert Spencer sought to reinterpret evolutionary theory as a rationale for capitalism, a tendency that was challenged by radical geographers like Peter Kropotkin and Elisée Reclus. In the 1950s, pioneering forest ecologists in the U.S. adopted methods of land management that had their origins in World War II military strategies. Historian and social ecologist Peter Staudenmaier has documented a vast web of connections linking ecological and fascist ideas throughout the 20th century, as well as specific links between recent ecofascist tendencies and their mid-20th century antecedents.[7]

Today’s global crises — economic, ecological and social — have ushered in horrific waves of authoritarian populism and white supremacism, driven by a politics of bigotry, scapegoating and ethnic nationalism. In response, movements for liberation need to be exceptionally clear that we embrace principles of solidarity, mutualism, anti-racism, and a profound commitment to climate justice. There is no room in such a movement for scapegoating, isolationism or nihilism, and it is truly unfortunate that two of the most articulate and widely quoted voices of militant resistance to the status quo have not yet accepted that fundamental lesson.| P

[1] Guy Debord, “The Decline and Fall of the Spectacle-Commodity Economy,” (1965) <www.cddc.vt.edu>.

[2] Chaz Bufe, “Listen, Anarchist!” The Anarchist Library, available online at: <theanarchistlibrary.org>.

[3] D. Graeber and D. Wengrow. “How to change the course of human history.” Accessed March 2, 2018. <www.eurozine.com/change-course-human-history>.; D. Wengrow and D. Graeber, “Farewell to the ‘childhood of man’: ritual, seasonality, and the origins of inequality,” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 21, no. 3 (2015): 597–619.

[4] P. Kingsnorth, “The lie of the land: does environmentalism have a future in the age of Trump?” The Guardian, March 18, 2017.

[5] Blockadia, a term coined by the Texas-based Tar Sands Blockade in the early 2010s and popularized by Naomi Klein, represents the proliferation of spaces of resistance to the expansion of fossil fuel infrastructure and other extractive industries. Alternatiba is a French Basque word that was adopted as the name of a bicycle tour to highlight alternative-building projects throughout France during the lead-up to the 2015 Paris climate conference. Combes proposed linking the two in a unified grassroots response to the anticipated failings of Paris. See Combes, Maxime. “Towards Paris2015, Challenges and Perspectives. Blockadia and Alternatiba, the Two Pillars of Climate Justice.” France attac. Accessed December 20, 2014. france.attac.org/IMG/pdf/Towards_Paris2015-climate%20justice.pdf.

[6] B. Taylor, “Alt-right ecology: Ecofascism and far-right environmentalism in the United States,” in The Far Right and the Environment: Politics, Discourse and Communication, ed.B. Forchtner (London: Routledge, 2019), 286.

[7] J. Biehl and P. Staudenmaier, Ecofascism: Lessons from the German Experience (San Francisco: AK Press, 1995) revised and expanded, 2011.