Protecting half of the planet could directly affect over one billion people

Received: 7 May 2019; Accepted: 9 October 2019; Published online: 18 November 2019

Judith Schleicher[1]{1}, Julie G. Zaehringer[2],[3], Constance Fastré[4], Bhaskar Vira[5], Piero Visconti[6] and Chris Sandbrook[7]

In light of continuing global biodiversity loss, one ambitious proposal has gained considerable traction amongst conservationists: the goal to protect half the Earth. Our analysis suggests that at least one billion people live in places that would be protected if the Half Earth proposal were implemented within all ecoregions. Taking into account the social and economic impacts of such proposals is central to addressing social and environmental justice concerns, and assessing their acceptability and feasibility.

To halt the rapid global loss of biodiversity, numerous conservation strategies have been implemented. Member states of the Convention on Biological Diversity have committed to placing 17% and 10% of the world’s terrestrial and marine areas, respectively, within protected areas by 2020, according to Aichi biodiversity target 11[8]. Although meeting this target is within the reach of many countries[9], rapid biodiversity loss continues[10]. As a result, conservationists have responded with alternative and more ambitious goals. One prominent proposal calls for the expansion of the global conservation estate to cover half of the Earth[11],[12]. This Half Earth or Nature Needs Half proposal has gained strong momentum, and has the potential to influence the post-2020 biodiversity targets and related processes[13]. Indeed, the Global Deal for Nature, a policy proposal that aims for 30% protection by 2030 and 50% protection by 2050, has been endorsed by a broad coalition of environmental organizations[14].

Achieving the Half Earth objective could involve radical changes in land and sea use across the planet. So far, the proposal has received some scrutiny with regards to environmental considerations[15] and its potential impacts on food production[16]. However, there has been no empirical analysis of other possible social and economic impacts of Half Earth, and the proposal itself has been ambiguous about the exact forms and locations of the new conserved areas being called for. This is despite the fact that the proposal’s social and economic impacts will influence its ability to deliver its conservation objectives, and that there are frequently trade-offs involved in meeting the environmental, social and economic goals associated with conservation and development interventions[17],[18]. The reported impacts of existing protected areas vary widely, from physical and economic displacement, to positive socio-economic outcomes for well-being or industry[19]. These impacts depend, in part, on the type of protected areas, their governance and the restrictions they place on resource use. Where the impacts are negative, they tend to disproportionally affect marginalized communities[20]. In light of this evidence from existing protected areas, the global increase in conserved areas to 50% could have considerable implications for the lives of those living inside, or in the vicinity of, these areas[21],[22].

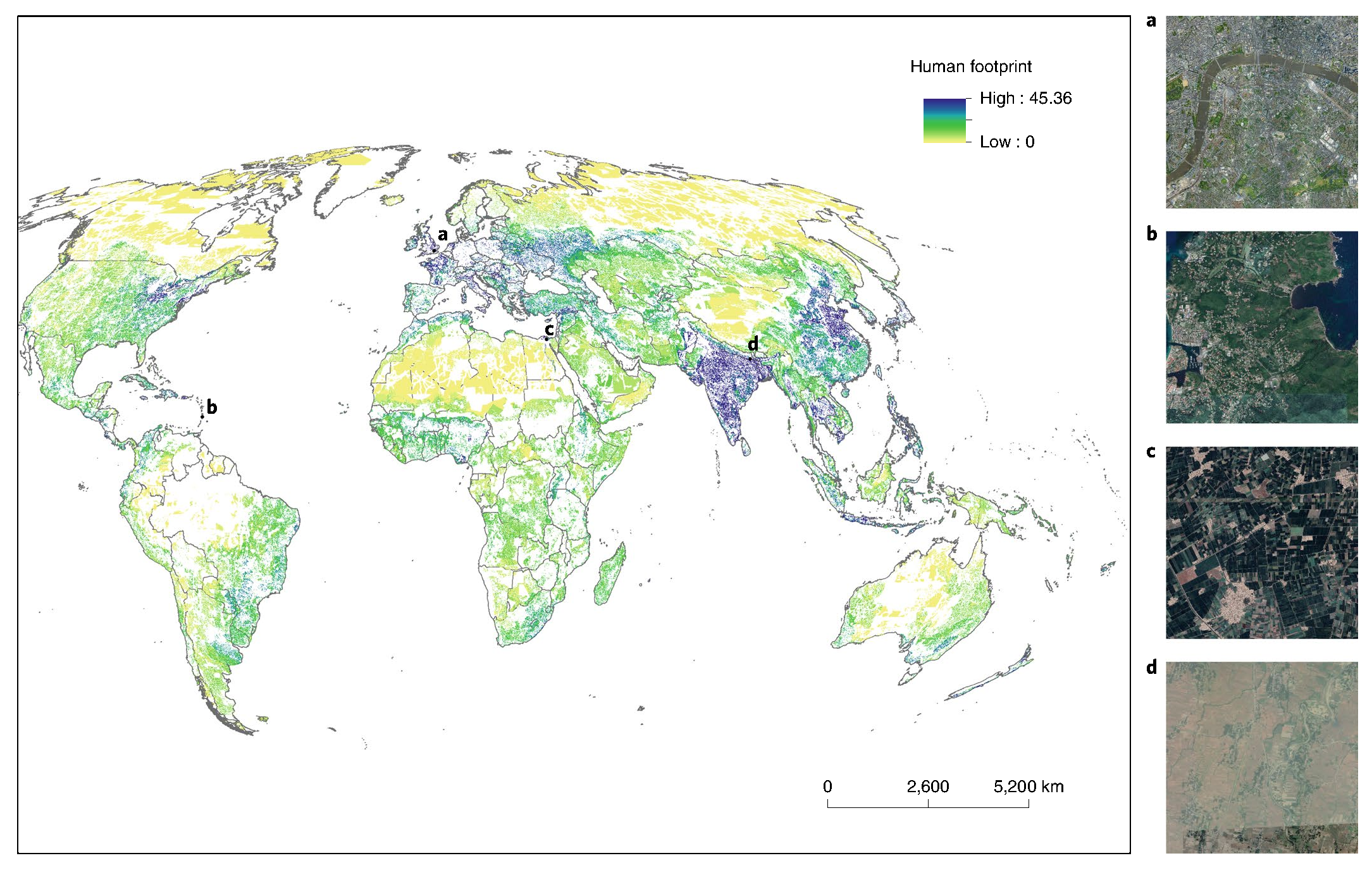

We investigated the human implications of Half Earth by assessing the number and distribution of people that would be directly affected if half of Earth’s land mass was protected. Since there is no consensus among those calling for a 50% protection target regarding which additional areas to protect, we based our analysis on the ecoregion approach proposed by Dinerstein and colleagues[23]. This approach is based on 846 ecoregions, to ensure protection of the full range of ecosystems and their associated species, and adequately conserve all elements of biodiversity. Dinerstein and co-workers[24] classify the ecoregions into four categories: those that already have 50% protection, those that could achieve 50% protection as sufficient natural habitat remains, those where 50% could be possible with substantial restoration efforts, and those with at most 20% of their natural habitat remaining and where achieving 50% protection of habitat is therefore very difficult. To calculate the minimum number of people who would live in the conserved areas, and hence be directly affected by Half Earth, we selected areas (~5 × 5 km pixels) to be added to the existing protected area network within each ecoregion, from lowest to highest human footprint value[25], until 50% coverage was achieved under one of two scenarios: (1) within all ecoregions or (2) only in ecoregions where Dinerstein and colleagues consider Half Earth to be feasible[26]. To achieve this, we combined global data layers of the ecoregions, protected areas (from the World Database of Protected Areas[27]) and the human footprint with a global human population layer of 2017[28].

Our approach assumes a protection strategy designed to minimize the key impacts on society, including avoiding areas with high population density and agricultural land. It ignores the effects on people living beyond the boundaries of the conserved areas, such as those constraining access to resources. For these reasons our approach generates a conservative estimate of the potential number of people affected. Indeed, areas with higher human footprint values, and higher population densities, would have to be protected if additional ecological criteria were applied to design the protection strategy, such as ensuring connectivity between conserved areas, setting minimum size thresholds of conserved areas or seeking to protect land with the highest biodiversity regardless of ecoregion. Hence, the number of people affected would probably be higher in an approach based on ecological criteria, especially in poorer countries that tend to have higher concentrations of biodiversity[29].

We found that over one billion people currently live in areas that would be protected under the Half Earth proposal, if it were applied to all ecoregions (Fig. 1). This is four times the number of people estimated, by our approach, to be living in protected areas today (247 million), and includes 760 million people living in additional areas that would need to become protected to meet the 50% target. If we only consider the ecoregions where Dinerstein and co-workers suggest that 50% protection is feasible[30], 28% of the ecoregions’ area (Supplementary Fig. 2), currently home to 170 million people, must be newly protected. This is roughly equivalent to the combined populations of the UK, Thailand and Morocco. The majority of people living in new areas to be protected live in middle-income countries, and ~10% live in low-income countries, regardless of whether we include all, or only less-impacted, ecoregions (Table 1).

The majority of the additional conserved areas have human footprint values within the lowest 20% (Supplementary Fig. 3). However, the global network of conserved areas necessary to achieve Half Earth would comprise areas with human footprint values within the top 20% under both scenarios, covering all ecoregions or only lessimpacted ones. At the upper end of this spectrum, these include highly developed areas, such as London (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Implementing Half Earth at the ecoregion level would clearly be in conflict with human activity, raising questions about the feasibility and diverse social implications of this strategy.

We recognize the importance of conserved areas for the future of life on Earth, and the fundamental need for radical action in the face of unfolding environmental crises. However, our findings highlight the crucial importance of taking into account the human impacts of Half Earth, Global Deal for Nature or other ambitious (area-based) conservation targets. Even with our conservative approach, a very large number of people would be affected by implementing Half Earth. Therefore, any such proposals need to explicitly consider and seriously engage with their social and economic consequences. Considering these implications is not only central to concerns about social and environmental justice, but will also determine how realistic their implementation is in terms of achieving their intended conservation outcomes.

Table 1. Number of people living in additional areas requiring protection to meet the Half earth targets within each ecoregion

Number of people (millions)

| All ecoregions | Less-impacted ecoregions | |

| Low | 75 (10%) | 16 (9%) |

| Lower-middle | 403 (53%) | 64 (37%) |

| Upper-middle | 234 (31%) | 65 (38%) |

| High | 47 (6%) | 25 (15%) |

Data are grouped according to the World Bank classification of low, lower-middle, upper-middle and high-income countries and according to whether (1) all ecoregions are included, or (2) only less-impacted ecoregions are included, where more than 20% of natural habitat remains. Percentage values of the total population are given for these two scenarios.

We make three recommendations based on our findings. First, Half Earth proponents should be explicit about the types and locations of the conserved areas they are calling for, to allow more indepth assessments of their social, economic and environmental impacts in the future. Second, the advocates of all area-based conservation measures should recognize and take seriously the human consequences, both negative and positive, of their proposals. Third, the parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, tasked with negotiating and implementing the post-2020 conservation framework, should apply more holistic, interdisciplinary approaches that take into account social and economic implications across various scales[31],[32]. Such approaches should consider important broader issues, such as environmental justice, the multiple values people attribute to nature and the need for action to tackle the ultimate economic consumption and production drivers of biodiversity loss[33],[34],[35].

Methods

To determine the number and distribution of people living in areas that would be protected under two Half Earth scenarios (50% protection within all ecoregions and 50% protection of those ecoregions with more than 20% natural habitat remaining), we combined the following global datasets: terrestrial ecoregions[36], human footprint[37], the World Database of Protected Areas (July 2018[38]) and the LandScan 2017 global population distribution[39]. We focused on ecoregions because (1) the Half Earth targets have been judged to be achievable, or already reached, in ~49% of all ecoregions[40], (2) they have been widely used as a proxy to capture biodiversity for conservation planning and (3) they are the basis for the Global Deal for Nature proposal[41] and for assessing Half Earth’s impacts on food production[42]. We grouped ecoregions into Dinerstein and co-workers’[43] four categories according to their percentage protection and the amount of natural habitat remaining. We selected new areas for protection (conserved areas) on the basis of the human footprint, which combines a broad range of human impacts, such as human population density, agricultural land area, infrastructure and transport routes. Although it does not capture some less intensive human influences, it is the most comprehensive global index of its kind. To determine the distribution of people within countries of different income statuses, we combined a global administrative areas layer at the country level[44] with the World Bank’s income classification[45] of low, low-middle, upper-middle and high-income countries. Disputed territories and countries without the World Bank’s income codes were excluded from the analysis (n = 6).

We pre-processed datasets using ArcGIS version 10.4.1[46]. We rasterized all datasets, projected them to Mollweide equal area at a spatial resolution of ~5 × 5 km, and set them to a common extent. Through this pre-processing, very small ecoregions (covering less than 50% of any pixel) were removed, resulting in 818 remaining ecoregions. We excluded Antarctica because it is not included in the human footprint dataset, nor in the analysis conducted by Dinerstein and colleagues[47]. As Antarctica is not permanently settled, excluding it does not affect our population count results.

We imported, stacked and analysed the raster datasets in R version 3.5.1[48]. To determine the area required to be protected in each ecoregion to meet the 50% target, we divided the total area of each ecoregion by two and subtracted the area currently protected per ecoregion according to the World Database of Protected Areas[49]. Under the first scenario, we then ordered the pixels in each ecoregion according to ascending human footprint values and selected the number of pixels with the lowest human footprint values to meet the 50% target within each ecoregion from pixels not under protection. We calculated the number of people living in the selected areas by summing the population count value[50]. We calculated the number of people living within existing protected areas by combining the World Database of Protected Areas with the population distribution data layer. Under the second scenario, we repeated this analysis, selecting only pixels from ecoregions where over 20% of the natural habitat remains. Last, we calculated the number of people living inside the conserved areas under each of these two scenarios per country, according to the World Bank’s income classification[51].

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are all publically available or available to educational institutions for non-commercial purposes, but not distributable by the authors. Details of each dataset and download links are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Code availability

The R code used to reproduce the results is provided in the Supplementary Information.

References

Acknowledgements

J.G.Z. undertook this work while a Visiting Scholar in the Department of Geography,

University of Cambridge (May 2018–April 2019), and was supported by the Swiss Programme for Research on Global Issues for Development (r4d programme), which is funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (grant no. 400440 152167). Our analysis was conducted utilizing the LandScan (2017) high resolution global population data set copyrighted by UT-Battelle, LLC, operator of Oak Ridge National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC0500OR22725 with the United States Department of Energy.

Author contributions

J.S., J.G.Z., C.F., B.V., P.V. and C.S. designed the analyses. J.S. and J.G.Z. compiled the data and conducted the analyses. J.S. wrote the paper with input from J.G.Z., C.F., B.V., P.V. and C.S.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0423-y.

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to J.S.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Toward an equitable future for all species

Our response to Schleicher et al. “One Billion People to be Directly Affected by Protecting Half.” Nature Sustainability (2019): 1-3.

By Dr. Helen Kopnina, Dr. Eileen Crist, Joe Gray, Dr. Katarzyna Nowak, Dr. John Piccolo, Ewa Orlikowska, Dr. Dominick DellaSala, Dr. Bron Taylor, Dr. Haydn Washington, Dr. Carl Safina & Dr. Simon Leadbeater

We are in a planetary recession marked by biodiversity collapse, climatic upheavals, freshwater shortages, global toxification, and unprecedented human and nonhuman displacements (Ripple et al, 2017). The only positive outlook lies in deep solutions and new narratives. Protecting at least half the Earth, terrestrial and marine, offers such an outlook. Safeguarding nature on a vast scale is necessary both to halt the mass extinction underway and to prevent further ecological degradation (Steffen et al., 2018). In addition to affording robust natural solutions to the ecological exigencies that are imperiling all complex life, the Half Earth (or Nature Needs Half) initiative charts a course toward a sustainable and equitable human coexistence alongside the millions of living beings with whom we share the planet (Noss et al., 2012; Wilson, 2016; Dinerstein et al., 2017; Kopnina 2016; Kopnina et al., 2018).

In implementing Half Earth, conservationists, scientists, and policy-makers should work in concert with Indigenous Peoples and local populations (Goodall, 2015). Such efforts are aimed at ensuring that, en route to preempting further ecological catastrophes and healing the relationship between humanity and Earth, wide-scale nature protection will not adversely affect people in proximity to these natural areas (Goodall, 2015; Naidoo et al., 2019). The level of protection proposed will also bar corporate ventures, such as mining, logging, and industrial agriculture, from profiteering at the ongoing expense of the natural world and local and Indigenous Peoples (Vettese, 2018).

It is thus disappointing that Judith Schleicher et al. (2019) undermine the spirited endeavors of Half Earth by recycling the cliché that people’s interests and the interests of the nonhuman world are perennially in conflict. The eco-catastrophes that we are witnessing display the deep untruth of this platitude, as humanity is now jeopardized by the consequences of unrestrained overreach in the ecosphere (Steffen et al., 2018). Ours is the moment to realize the ultimate falsehood of the “people versus nature” ostensible tradeoff and to recognize that the wellbeing—and malaise—of both are intertwined. Yet Schleicher et al., by tacitly raising the specter of fortress conservation, sabotage the needed transformation toward achieving the “win-win” alignment between humanity and the nonhuman world that Half Earth seeks to foster. Indeed, the subtext of their paper insinuates that the motives of conservationists are dubious.

Half Earth practitioners must work with communities to achieve ecological integrity and people’s wellbeing in tandem. To ensure that nonhuman and human worlds thrive together in the long term, and that people are not disadvantaged by large-scale nature protection, the Half Earth movement must be complemented by downscaling the human enterprise (Crist, 2019). This means degrowing the global economy, changing production and overconsumption patterns, and shifting to renewable energy sources (Rees, 2014). It also demands overhauling the financial system away from its debt-based mode of operation, which fuels consumerism and helps bankroll egregious levels of wealth. Additionally, to lower consumption and waste—in a world rapidly converging toward a middle-class standard of living—we must work internationally to stabilize and gradually reduce the global population (Pimentel et al., 2010). This goal is achievable by fast-tracking human-rights policies of family-planning services for all, education for girls and young women through at least secondary school, abolition of child marriage, and comprehensive sex education in every school (Crist et al., 2017). Shrinking the human enterprise also calls upon us to refrain from infrastructural expansion into protected or intact areas and, in some cases, to remove already-encroaching development upon these. These strategies can occur in urban areas through cradle-to-cradle designs, as well as on agricultural lands which can support more biodiversity, e.g., through regenerative approaches and setting aside wildlife habitat (McDonough and Braungart, 2002; Yigitcanlar et al., 2019).

Even in the midst of profound apprehension and grief, there is a cresting human awareness of what we stand to lose: the cosmic wealth of a living planet and the chance to inhabit it with grace (Rolston, 2012). Half Earth offers a global eco-social prospect that marries realism and vision. Schleicher et al. undermine this hope-filled course with the backsliding and killjoy insinuation of people versus nature. A throwback mindset is also acute in their blanket anthropocentrism, wherein considerations of justice and wellbeing apparently apply solely to humans; they fail to mention the rights of nonhumans to thrive or even to continue to exist (Chapron et al., 2019). Protecting nature is not meant to displace or disadvantage local communities, as Schleicher et al. imply, but to create sustainable coexistence. In this coexistence, ecological integrity—species diversity, thriving populations, and evolutionary potential—is of greater value than short-term human economic success.

The problem is not with Nature Needs Half, but that economic and population growth trends need to be addressed, for the sake of both human well-being and conservation. At a deeper level, we must move in the ethically inclusive direction of protecting the natural world not only because it is good for us, but also because it is good for all (Piccolo et al., 2018). Such inclusive worldviews are already emerging in the leading wave of both popular and academic cultures, leaving behind the human-centered presumption that pervades Schleicher et al.’s paper. The present-day watchwords spurring humanity toward a lively and equitable future—including intersectional justice, rights of nature, rewilding, and multispecies flourishing—reflect the ascending human consciousness of all-Earthling solidarity. Half Earth is an essential component of making that future a reality.

References

Chapron, G. et al. 2019. "A rights revolution for nature." Science 363 (6434): 1392-1393.

Crist, E. et al. 2017. "The interaction of human population, food production, and biodiversity protection." Science 356 (6335): 260-264.

Crist, E. 2019. Abundant Earth: Toward an Ecological Civilization. University of Chicago Press.

Dinerstein, E., et al. 2017. "An ecoregion-based approach to protecting half the terrestrial realm." BioScience 67 (6): 534-545.

Goodall, J. 2015. Caring for people and valuing forests in Africa.” In Wuerthner, et al., eds. 2015. Protecting the Wild: Parks and Wilderness, the Foundation for Conservation. Washington D.C.: Island Press, pp. 21-26.

Kopnina, H. 2016. Half the earth for people (or more)? Addressing ethical questions in conservation. Biological Conservation, 203, pp.176-185.

Kopnina, H., et al. 2018. "The ‘future of conservation’ debate: Defending ecocentrism and the Nature Needs Half movement." Biological Conservation 217: 140-148.

McDonough, W. and Braungart, M. 2002. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. New York: North Point Press.

Naidoo, R., et al. 2019. Evaluating the impacts of protected areas on human well-being across the developing world. Science Advances, 5(4): eeav3006.

Noss, R.F., et al. 2012. Bolder thinking for conservation. Conservation Biology, 26:1-4.

Piccolo, J. et al. 2018. Why conservation biologists should re-embrace their ecocentric roots’. Conservation Biology, 32(4): 959-961.

Pimentel, D. et al. 2010. “Will Limited Land, Water, and Energy Control Human Population Numbers in the Future?” Human Ecology, 38 (5): 599-611.

Rees, W. 2014. “Avoiding Collapse: An Agenda for Sustainable Degrowth and Relocalizing the Economy.” Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. BC Office.

Ripple, W.J. et al. 2017. World scientists’ warning to humanity: a second notice. BioScience, 67(12):1026-1028.

Rolston, H. A New Environmental Ethics: The next millennium for life on earth. London: Routledge, 2012.

Steffen, W. et al. 2018. Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene. PNAS http://www.pnas.org/content/pnas/early/2018/07/31/1810141115.full.pdf

Wilson, E. O. 2016. Half Earth: Our Planet's Fight for Life. WW Norton & Company.

Vettese, T. 2018. To freeze the Thames: Natural geo-engineering and biodiversity. New Left Review, 111: 63-86.

Yigitcanlar, T. et al. 2019. Towards post-anthropocentric cities: Reconceptualizing smart cities to evade urban ecocide. Journal of Urban Technology, 26 (2): 147-152.

[1] Department of Geography, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK.

[2] Department of Geography, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK.

[3] Centre for Development and Environment, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland.

[4] Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, London, UK.

[5] Department of Geography, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK.

[6] International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Laxenburg, Austria.

[7] Department of Geography, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK.

[8] The Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020 and the Aichi Biodiversity Targets (CBD, 2010).

[9] Tittensor, D. P. et al. A mid-term analysis of progress toward international biodiversity targets. Science 346, 241–245 (2014).

[10] Global Assessment Preview (IPBES, 2019).

[11] Locke, H. Nature needs half: a necessary and hopeful new agenda for protected areas in North America and around the world. George Wright Forum 31, 359–371 (2014).

[12] Wilson, E. O. Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life (Liveright, 2016).

[13] Dinerstein, E. et al. A global deal for nature: guiding principles, milestones, and targets. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw2869 (2019).

[14] Synthesis of Views of Parties and Observers on the Scope and Content of the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework (CBD, 2019).

[15] Dinerstein, E. et al. An ecoregion-based approach to protecting half the terrestrial realm. BioScience 67, 534–545 (2017).

[16] Mehrabi, Z., Ellis, E. C. & Ramankutty, N. The challenge of feeding the world while conserving half the planet. Nat. Sustain. 1, 409–412 (2018).

[17] Ellis, E. C., Pascual, U. & Mertz, O. Ecosystem services and nature’s contribution to people: negotiating diverse values and trade-offs in land systems. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 38, 86–94 (2019).

[18] Brockington, D. & Wilkie, D. Protected areas and poverty. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 370, 20140271 (2015).

[19] Oldekop, J. A., Holmes, G., Harris, W. E. & Evans, K. L. A global assessment of the social and conservation outcomes of protected areas. Conserv. Biol. 30, 133–141 (2016).

[20] West, P., Igoe, J. & Brockington, D. Parks and peoples: the social impact of protected areas. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 35, 251–277 (2006).

[21] Büscher, B. et al. Half-Earth or whole Earth? Radical ideas for conservation, and their implications. Oryx 51, 407–410 (2017).

[22] Kopnina, H. Half the earth for people (or more)? Addressing ethical questions in conservation. Biol. Conserv. 203, 176–185 (2016).

[23] Dinerstein, E. et al. An ecoregion-based approach to protecting half the terrestrial realm. BioScience 67, 534–545 (2017).

[24] Dinerstein, E. et al. An ecoregion-based approach to protecting half the terrestrial realm. BioScience 67, 534–545 (2017).

[25] Venter, O. et al. Sixteen years of change in the global terrestrial human footprint and implications for biodiversity conservation. Nat. Commun. 7, 12558 (2016).

[26] Dinerstein, E. et al. An ecoregion-based approach to protecting half the terrestrial realm. BioScience 67, 534–545 (2017).

[27] World Database on Protected Areas (UNEP-WCMC & IUCN, 2018); https://protectedplanet.net

[28] Bright, E. A., Rose, A. N., Urban, M. L. & McKee, J. LandScan 2017 High-Resolution Global Population Data Set (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 2018).

[29] Balmford, A. et al. Conservation conflicts across Africa. Science 291, 2616–2619 (2001).

[30] Dinerstein, E. et al. An ecoregion-based approach to protecting half the terrestrial realm. BioScience 67, 534–545 (2017).

[31] Büscher, B. et al. Half-Earth or whole Earth? Radical ideas for conservation, and their implications. Oryx 51, 407–410 (2017).

[32] Visconti, P., Bakkenes, M., Smith, R. J., Joppa, L. & Sykes, R. E. Socio-economic and ecological impacts of global protected area expansion plans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 370, 20140284 (2015).

[33] Ellis, E. C., Pascual, U. & Mertz, O. Ecosystem services and nature’s contribution to people: negotiating diverse values and trade-offs in land systems. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 38, 86–94 (2019).

[34] Büscher, B. et al. Half-Earth or whole Earth? Radical ideas for conservation, and their implications. Oryx 51, 407–410 (2017).

[35] Ten Brink, B. et al. Rethinking Global Biodiversity Strategies: Exploring Structural Changes in Production and Consumption to Reduce Biodiversity Loss (Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, 2010).

[36] Dinerstein, E. et al. An ecoregion-based approach to protecting half the terrestrial realm. BioScience 67, 534–545 (2017).

[37] Venter, O. et al. Sixteen years of change in the global terrestrial human footprint and implications for biodiversity conservation. Nat. Commun. 7, 12558 (2016).

[38] World Database on Protected Areas (UNEP-WCMC & IUCN, 2018); https://protectedplanet.net

[39] Bright, E. A., Rose, A. N., Urban, M. L. & McKee, J. LandScan 2017 High-Resolution Global Population Data Set (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 2018).

[40] Dinerstein, E. et al. An ecoregion-based approach to protecting half the terrestrial realm. BioScience 67, 534–545 (2017).

[41] Synthesis of Views of Parties and Observers on the Scope and Content of the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework (CBD, 2019).

[42] Mehrabi, Z., Ellis, E. C. & Ramankutty, N. The challenge of feeding the world while conserving half the planet. Nat. Sustain. 1, 409–412 (2018).

[43] Dinerstein, E. et al. An ecoregion-based approach to protecting half the terrestrial realm. BioScience 67, 534–545 (2017).

[44] Database of Global Administrative Areas (GADM, 2018) https://gadm.org/

[45] Country Classification (World Bank, 2018).

[46] ArcGIS for Desktop v.10.4.1 (ESRI, 2016).

[47] Dinerstein, E. et al. An ecoregion-based approach to protecting half the terrestrial realm. BioScience 67, 534–545 (2017).

[48] R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2018).

[49] World Database on Protected Areas (UNEP-WCMC & IUCN, 2018); https://protectedplanet.net

[50] Bright, E. A., Rose, A. N., Urban, M. L. & McKee, J. LandScan 2017 High-Resolution Global Population Data Set (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 2018).

[51] Country Classification (World Bank, 2018).

{1} e-mail: Judith.Schleicher@cantab.net

Appendix from Nature Sustainability, Jan 17, 2020. <communities.springernature.com/posts/toward-an-equitable-future-for-all-species>