Scott Corey

Kaczynski’s views might be on trial, too

The Unabomber case might force government lawyers to buck a tradition of not prosecuting people for their political beliefs

Dec 21, 1997

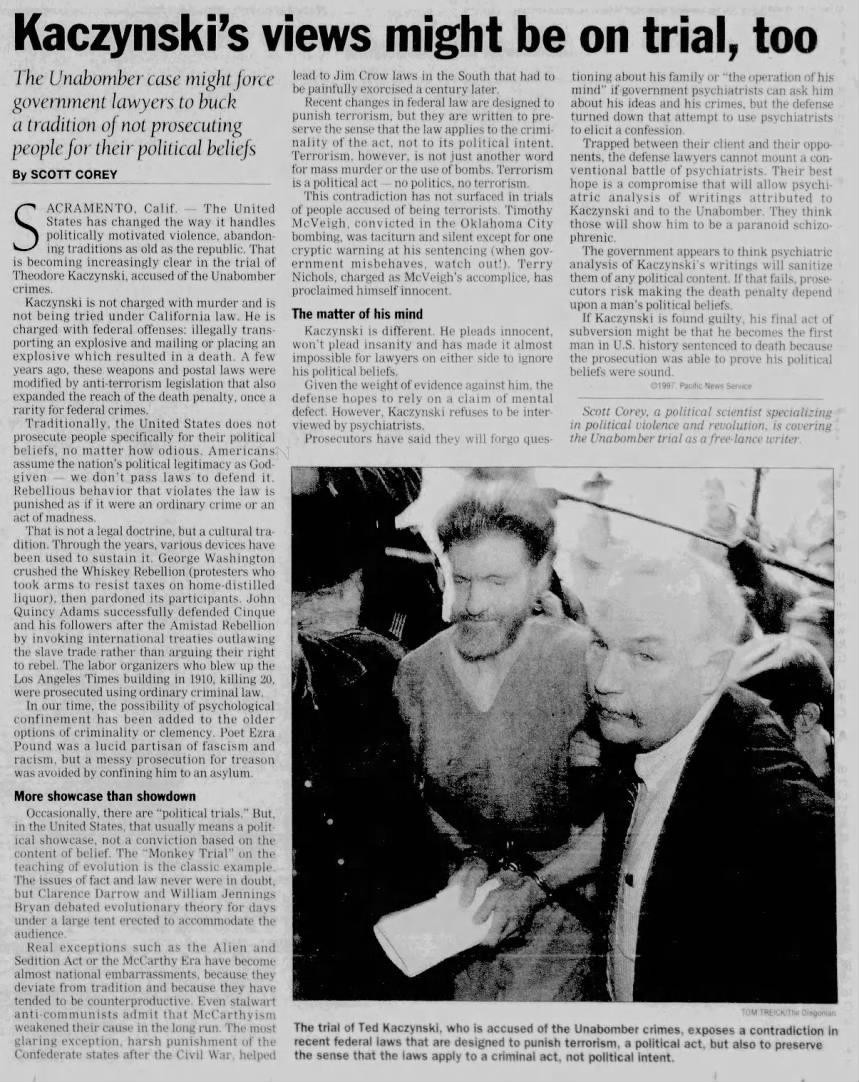

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — The United States has changed the way it handles politically motivated violence, abandoning traditions as old as the republic. That is becoming increasingly clear in the trial of Theodore Kaczynski, accused of the Unabomber crimes.

Kaczynski is not charged with murder and is not being tried under California law. He is charged with federal offenses: illegally transporting an explosive and mailing or placing an explosive which resulted in a death. A few year’s ago. these weapons and postal laws were modified by anti-terrorism legislation that also expanded the reach of the death penalty, once a rarity for federal crimes.

Traditionally, the United States does not prosecute people specifically for their political beliefs, no matter how odious. Americans assume the nation’s political legitimacy as God-given we don’t pass laws to defend it. Rebellious behavior that violates the law is punished as if it were an ordinary crime or an act of madness.

That is not a legal doctrine, but a cultural tradition. Through the years, various devices have been used to sustain it. George Washington crushed the Whiskey Rebellion (protesters who took arms to resist taxes on home-distilled liquor), then pardoned its participants. John Quincy Adams successfully defended Cinque and his followers after the Amistad Rebellion by invoking international treaties outlawing the slave trade rather than arguing their right to rebel. The labor organizers who blew up the Los Angeles Times building in 1910, killing 20, were prosecuted using ordinary criminal law.

In our time, the possibility of psychological confinement has been added to the older options of criminality or clemency. Poet Ezra Pound was a lucid partisan of fascism and racism, but a messy prosecution for treason was avoided by confining him to an asylum.

More showcase than showdown

Occasionally, there are “political trials.” But. in the United States, that usually means a political showcase, not a conviction based on the content of belief. The “Monkey Trial” on the teaching of evolution is the classic example. The issues of fact and law never were in doubt, but Clarence Darrow and William Jennings Bryan debated evolutionary theory for days under a large tent erected to accommodate the audience.

Real exceptions such as the Alien and Sedition Act or the McCarthy Era have become almost national embarrassments, because they deviate from tradition and because they have tended to be counterproductive. Even stalwart anti communists admit that McCarthyism weakened their cause in the long run. The most glaring exception. harsh punishment of the Confederate states after the Civil War, helped lead to Jim Crow laws in the South that had to be painfully exorcised a century later.

Recent changes in federal law are designed to punish terrorism, but they are written to preserve the sense that the law applies to the criminality of the act, not to its political intent. Terrorism. however, is not just another word for mass murder or the use of bombs. Terrorism is a political act — no politics, no terrorism.

This contradiction has not surfaced in trials of people accused of being terrorists. Timothy McVeigh, convicted in the Oklahoma City bombing, was taciturn and silent except for one cryptic warning at his sentencing (when government misbehaves, watch out!). Terry Nichols, charged as McVeigh’s accomplice, has proclaimed himself innocent.

The matter of his mind

Kaczynski is different. He pleads innocent, won’t plead insanity and has made it almost impossible for lawyers on either side to ignore his political beliefs.

Given the weight of evidence against him, the defense hopes to rely on a claim of mental defect. However, Kaczynski refuses to be interviewed by psychiatrists. Prosecutors have said they will forgo questioning about his family or “the operation of his mind” if government psychiatrists can ask him about his ideas and his crimes, but the defense turned down that attempt to use psychiatrists to elicit a confession.

Trapped between their client and their opponents, the defense lawyers cannot mount a conventional battle of psychiatrists. Their best hope is a compromise that will allow psychiatric analysis of writings attributed to Kaczynski and to the Unabomber. They think those will show him to be a paranoid schizophrenic.

The government appears to think psychiatric analysis of Kaczynski’s writings will sanitize them of any political content. If that fails, prosecutors risk making the death penalty depend upon a man’s political beliefs.

If Kaczynski is found guilty, his final act of subversion might be that he becomes the first man in U.S. history sentenced to death because the prosecution was able to prove his political beliefs were sound.

Scott Corey, a political scientist specializing in political violence and revolution, is covering the Unabomber trial as a freelance writer.