Ted Kaczynski’s Correspondence with Adam Parfrey

2003–2015

Introduction

Between 1978 and 1995, Ted Kaczynski, a Harvard-educated mathematician, sent 16 package bombs. All of them exploded. Three people were killed and 23 others injured. The first bomb went to a materials-engineering professor at Northwestern University. It was followed by explosives mailed to a computer-store owner, an advertising executive, a timber-industry lobbyist, and a behavioral geneticist. One of the handcrafted devices was planted in the cargo hold of an American Airlines Boeing 727, forcing the pilot to make an emergency landing.

In 1971, two years after quitting his job as an assistant professor at the University of California at Berkeley, Kaczynski moved to a remote cabin near Lincoln, Montana, and lived as a recluse. It was the embittered Kaczynski’s contention that humanity evolved under primitive, low-tech conditions, and that only a violent collapse of the modern era’s daunting techno-industrial system could restore man to his natural state.

Caving to his promise to “desist from terrorism” if given a wide platform for his views, The New York Times and The Washington Post agreed in 1995 to publish his so-called manifesto, in which he conceded that the bombings were extreme but necessary to end technology’s evils.

Now incarcerated at the maximum-security prison in Florence, Colorado, Kaczynski, 68, lives on “Celebrity Row” with such incorrigibles as World Trade Center bombing mastermind Ramzi Yousef and, before his 2001 execution, Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh. Kaczynski has corresponded with several people during his confinement, including Parfrey, whose provocative essays about imminent global catastrophe, and the kinds of agitative authors he’d published, had not gone unnoticed by the Unabomber.

Beginning in 2003, Parfrey and Kaczynski exchanged dozens of letters, leading Parfrey to publish the “collected writings” of Kaczynski under the title Technological Slavery.

“The letters from him were extremely focused,” Parfrey recalls. “None of them were particularly revealing, other than to show his obsessive-compulsive behavior. I knew that he had published his work The Road to Revolution in 2008, in Switzerland [by Xenia Press], and that he was very unhappy with how that turned out. So I knew he was looking for [another] publisher.

“I had read his manifesto when it came out, and I found that there was more than just madness to him,” adds Parfrey. “I know he’s a killer and sociopath, but I found myself in agreement with a lot of what he’s written, and that his message is worth explaining.”

Parfrey was initially contacted by David Skrbina, a University of Michigan philosophy professor who also had corresponded at length with Kaczynski. The Unabomber found a kindred spirit in the professor, a pioneer in the field of ecosophy—or “deep ecology”—which emphasizes the interdependence of human and nonhuman life. It was Skrbina who convinced Kaczynski to produce a revised book, based on his prison letters and newly written essays.

For a time, Kaczynski and Parfrey haggled over what to call the book, a paperback with a 3,000-copy first printing. “He suggested Technological Suicide, and I said I wanted a new title,” remembers Parfrey. “Then he finally said Technological Slavery, which is exactly what I wanted in the first place.”

When news first surfaced in late September that Parfrey had published the Unabomber’s work, the Los Angeles Times reported that he and Skrbina had fretted over the moral issue of giving a convicted murderer this kind of vehicle to promote his beliefs. Absolutely untrue, says Parfrey, specifying that he and Skrbina “didn’t agonize over this at all. I wanted to publish it and I did.” (Kaczynski is forbidden by the so-called “Son of Sam Law” from profiting from his crimes, and will not receive a cent in book royalties.)

Recalls Skrbina: “Yes, I had concerns, obviously, about the crimes and the murders, but I was looking purely at arguments about technology that he was raising, and I said we [have] got to separate that.”

“There’s been no real anger at all,” adds Parfrey, citing the lack of negative reaction Technological Slavery has elicited. “Maybe that’s because a lot of his concepts don’t seem so weird to a lot of people.”

In fact, a number of contemporary critics of technology and industrialization agree with Kaczynski’s message, if not his violence, including John Zerzan, a leader of the primitivist movement in the U.S., and Herbert Marcuse, a renowned German political theorist who died a year after Kaczynski embarked on his bombing spree.

Then there is Bill Joy, the founder of Sun Microsystems, who in April 2000 wrote in Wired magazine: “I am no apologist for Kaczynski. His bombs killed three people during a 17-year terror campaign and wounded many others. One of his bombs gravely injured my friend David Gelernter, one of the most brilliant and visionary computer scientists of our time. Like many of my colleagues, I felt that I could easily have been the Unabomber’s next target. Kaczynski’s actions were murderous and, in my view, criminally insane. He is clearly a Luddite, but simply saying this does not dismiss his argument.”

Kaczynski, notes Parfrey, was not at all happy with Technological Slavery‘s final cover design, an FBI reconstruction of the homemade package bombs. Parfrey says the cover was a collaborative effort with Bill Smith, an artist who has designed covers for LA Weekly, Seattle Weekly‘s sister paper in Los Angeles.

Asked what troubled Kaczynski, Parfrey smiles and confides, “He said it was in bad taste.”

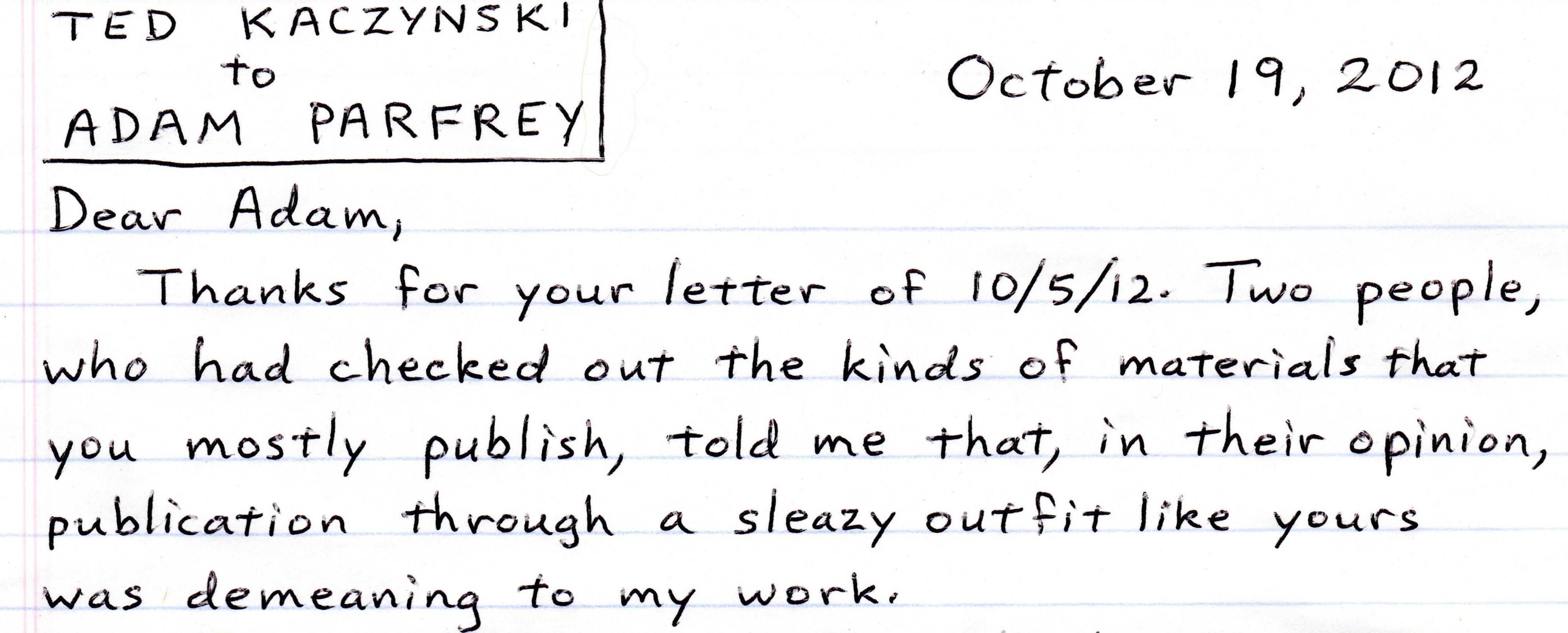

Ted to Adam — October 19th, 2012

Dear Adam,

Thanks for your letter of 10/5/12. Two people, who had checked out the kinds of materials that you mostly publish, told me that, in their opinion, publication through a sleazy outfit like yours was demeaning to my work.

Ted to Jeff — September 28th, 2014

Dear Jeff,

Thanks for your letter of 9/6/14, which I received on 9/17/14. I’m sorry I haven’t answered sooner, but problems continually come up here ...

I agree with you about e-books, and for the same reason: It is scary that the companies that offer e-books can rewrite them at will. But there’s more: If the publisher of an e-book goes out of business or simply decides to delete the book it just disappears, whereas a book printed on good paper will last for centuries. Also (though this is less important), e-books don’t give the page numbers of the corresponding printed book, which creates a problem if a user of an e-book and a user of the printed version want to cite particular passages to one another. The publisher of Tech Slavery, Adam Parfrey, published the e-version without my permission. Parfrey is now publishing T.S. on an expired contract, and Julie and I have been exploring the possibilities for legally forcing Parfrey either to stop publication altogether or to negotiate a new contract that will bar e-books. Julie can give you up-to-date information on that, which I don’t yet have....

Ted to Jeff — April 13th, 2015

I hope you’ve received my letter of 2/9/15. Susan tells me that you told her that you had heard from someone at Feral House that they would be interested in publishing my new book....

I’ll appreciate it if you’ll send the following message from me to the person from whom you heard the expression of interest:

A precondition for any discussion of possible publication of my new book by Feral House is an explicit, written acknowledgment by Adam Parfrey that his right to publish Technological Slavery expired upon the expiration of my contract with Xenia, and that his continued publication of Technological Slavery constitutes an infringement of my copyright.

Of course, there’s virtually no chance that Parfrey will give me such an acknowledgment, but I’ll appreciate it if you’ll send the message anyway, just as a challenge to Parfrey.

Thanks.

I hope all is well with you & your family.

Best regards,

Ted