Various Authors

The Luddite Dispatch

August 2024-April 2025. The dispatch is still running, so new issues will be archived as and when new ones are made.

Photocopies

Vol. 1 — No. 1 (Extract)

Vol. 1 — No. 2

Vol. 1 — No. 3

Digitized

Vol. 1 — No. 1 (Extract)

August 2024 — Free

What is the Luddite Club?

We’re a team of ex screenagers, who found more fulfilling lives offline. Three years ago, we started a club in Brooklyn for like-minded Luddites to meet up and converse with one another each weekend. Now, by transitioning from a club to a nonprofit, we want to help more teens nationwide learn the tools we used to effectively manage digital dependency themselves.

Looking for club-starters, artists, and writers interested in contributing to our next edition!

Finding Community Beyond the Screen

Logan Lane —

I was an iPad kid. At ten years old, I found myself longing to be famous on apps like Instagram, Snapchat, and TikTok. My phone kept the curated lives of my peers with me — at the bus stop, at the dinner table, and finally to my bed, where I fell asleep late at night, groggy and irritable, clutching my device. I constantly plotted my Instagram identity. On some days, I wanted to look effortlessly beautiful. On other days, I wanted to seem too cool to care. Often I yearned for both identities at the same time, which was a Sisyphean task.

I was a compulsive creator and artistic jammer. I liked to sew, knit, and draw, but my crafts only seemed to matter if I could post them online for digital praise. The way I see it now, when you have a toxic relationship with these platforms, you’re either judging yourself or other people. And I often fell prey to these judgmental behaviors.

However, Sitting next to Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn one afternoon with some kids who called themselves urban explorers, I felt the sudden urge to throw my iPhone into the water. I saw no difference between the garbage on my phone and the garbage surfacing in the polluted canal. I soon powered off my phone, put it in a drawer, and signed off social media for good. Thus began my life as a Luddite....

Vol. 1 — No. 2

April 2025 — Free

Unplugged and Unraveled: Why Seine-Port’s Smartphone Ban Failed

By Logan Lane and August Lamm

We flew into Charles de Gaulle Airport in late January. We had spent our seven-hour flight crammed between a stylish French woman, asleep, with a large iPhone in her limp hand and an American tech bro playing Block Blast, a mobile gaming phenomenon that had captivated everyone from anxious fourth graders to stoned high schoolers to, apparently, lull-grown men on transatlantic flights.

Despite our tech-dependent seat mates, our idealized vision of Europe as a mecca for techno skeptics was still intact. In the past five years, we had watched New York City become a mapless ghost of its historic self, with screens and barcodes everywhere: street corners, restaurants, even the subterranean world of the subway. But France, we knew, was rich in “third spaces” venues not dedicated to work, school, or commerce, where people gathered together in public.

France had a culture that valued historic preservation, technological skepticism, and government intervention, and it was home to the reason we had come here in the first place—Seine-Port, a small suburban city just south Paris with a population of just 2,000, which had made headlines the previous year for its ban on smartphone use in public. If a community could resist an ever expanding techno future, it made sense that it would be French.

The mayor of Seine-Port, Vincent Paul-Petit, was the former CEO of an SME that folded after being hacked. He conceived of the ban in response to, “a lot of problems in terms of health and attention capacity.” that excessive cell phone use had brought to his constituents. Paul-Petit saw a future for his little city that harkened back to a more bucolic past: when people actually spoke to each other in public. His decree restricted the use of smartphones at school gates, restaurants, parks, and on the sidewalk. Recommendations for parents discouraged screen use for children before school, in the evenings, in bedrooms, and at mealtimes. Free flip phones were provided to residents under 15. The decree passed by a slim margin of 54%, and was enforced on March 1. 2024.

By the time we arrived in Seine Port, the ban had been the victim of legal entanglements and had been officially overturned. Paul-Petit was informed by regional authorities that he was not authorized to pass such a ban and the official mandate was revoked.

But Paul-Petit had assured that the ban was still widely accepted. “It works.” he insisted, during a chat before we arrived. “Most people arc keeping the rule for themselves.” The residents of Seine-Port, he claimed, were now walking to the bakery without their smartphones, even striking up conversations with local shopkeepers. These changes, however minor, were important to him, and indicative of an important cultural shift, but Paul-Petit’s ultimate ambition was a countrywide ban.

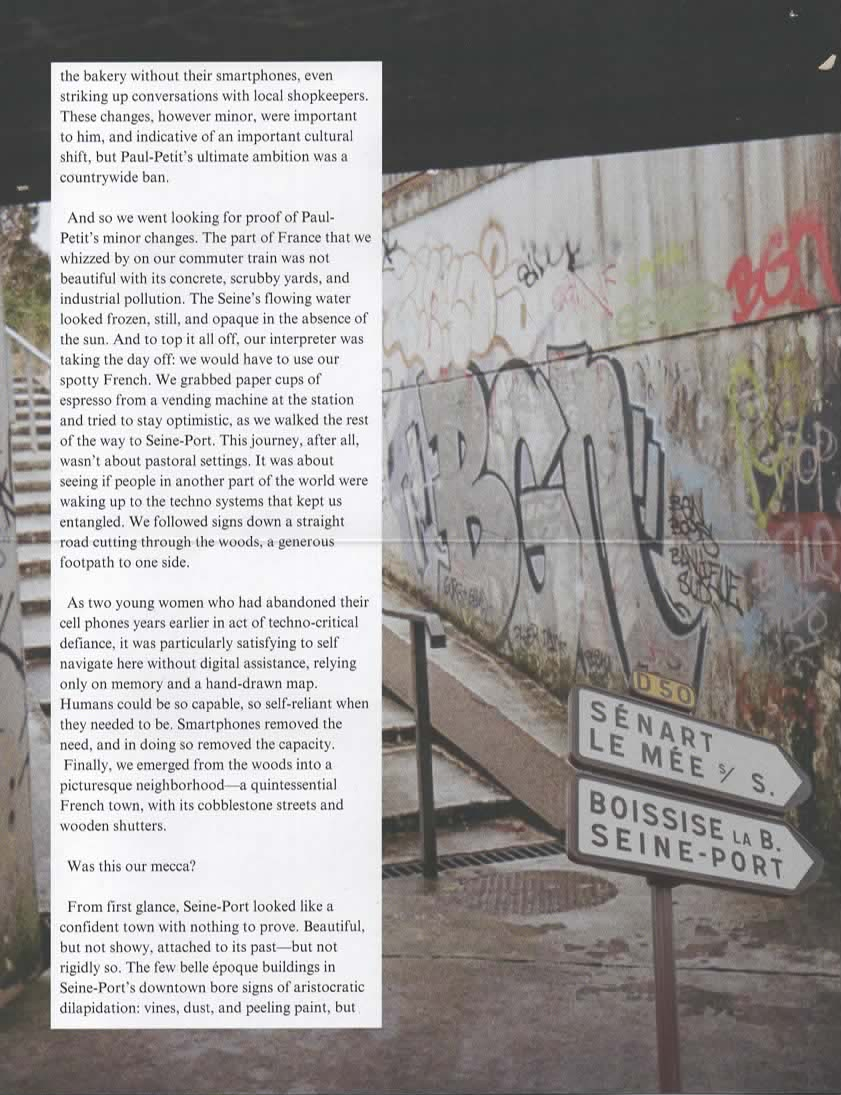

And so we went looking for proof of Paul-Petit’s minor changes. The part of France that we whizzed by on our commuter train was not beautiful with its concrete, scrubby yards, and industrial pollution. The Seine’s flowing water looked frozen, still, and opaque in the absence of the sun. And to top it all off, our Interpreter was taking the day off: we would have to use our spotty French. We grabbed paper cups of espresso from a vending machine at the station and tried to stay optimistic, as we walked the rest of the way to Seine-Port. This journey, after all, wasn’t about pastoral settings. It was about seeing if people in another part of the world were waking up to the techno systems that kept us entangled. We followed signs down a straight road cutting through the woods, a generous footpath to one side.

As two young women who had abandoned their cell phones years earlier in act of techno-critical defiance, it was particularly satisfying to self navigate here without digital assistance, relying only on memory and a hand-drawn map.

Humans could be so capable, so self-reliant when they needed to be. Smartphones removed the need, and in doing so removed the capacity.

Finally, we emerged from the woods into a picturesque neighborhood—a quintessential French town, with its cobblestone streets and wooden shutters.

Was this our mecca?

From first glance. Seine-Port looked like a confident town with nothing to prove. Beautiful, but not showy, attached to its past—but not rigidly so. The few belle époque buildings in Seine-Port’s downtown bore signs of aristocratic dilapidation: vines, dust, and peeling paint, but no structural issues, and certainly no graffiti. It was a city secure enough to let itself go a bit. like a tech start-up’s young CEO with a stain on his shirt, what did it matter? Seine-Port’s reputation as an insular enclave for the old and wealthy—could easily withstand it.

A small cafe-cum-tabac by the main square was evidently the city’s hub. We headed inside and sat at a table near the window and looked out onto the central plaza, a dusty beige square on which a group of older men played petanque. There were no smartphones in sight. In fact, the most advanced technology we spotted was a retractable string with a magnet on the end, for picking up the metal petanque balls without having to bend down. Perhaps the official ban. now overturned, had not been necessary in the first place—at least not for this demographic.

Eager for confirmation, we surveyed the restaurant where, according to Paul-Petit, screens were no longer ubiquitous, Our hearts sank. In a room of 11 residents over the age of 65 we counted seven smartphones, watched three people make calls at the table, one on speakerphone. Worst of all, we watched a woman use two smartphones, one of them showing a food TikTok—frying pans and cutting boards flashing as she ate her boeuf bourguignon.

Still holding out hope, we went looking for more residents who might shed light on whether the ban had had a positive impact on their town.

We were surprised to find a tattoo and piercing parlor on the main street. If only for a chance to interview the 30-somethings inside, wc contemplated getting piercings. It wasn’t necessary. The tattoo-plastered woman working there was eager to talk about the ban. “The whole thing is ridiculous,” she proclaimed. ” Then in authoritative defiance mixed with rage, she assured us: “Don’t worry, you can use your phone anywhere.” We quickly realized that she was misidentifying us as two people ensuring that the right to use your phone had won out in Seine-Port. We asked her if anyone ever stopped her while she was using her smartphone and encouraged her to put it down. “Occasionally,” she scoffed, “an old person will, but I don’t care about them.”

We were uncovering that Paul-Petit’s cell phone ban had not liberated Seine-Port. It had in fact started a mini-war and launched a fight over power and overreach. It angered people. Phones in Seine-Port were not seen by residents as signs of addiction. Using one in public was now a brave act of civil disobedience.

We shuddered at the thought of poor Paul-Petit. His noble effort to save his town had backfired. This wasn’t our Mecca, the smartphone situation here was much like that in any city.

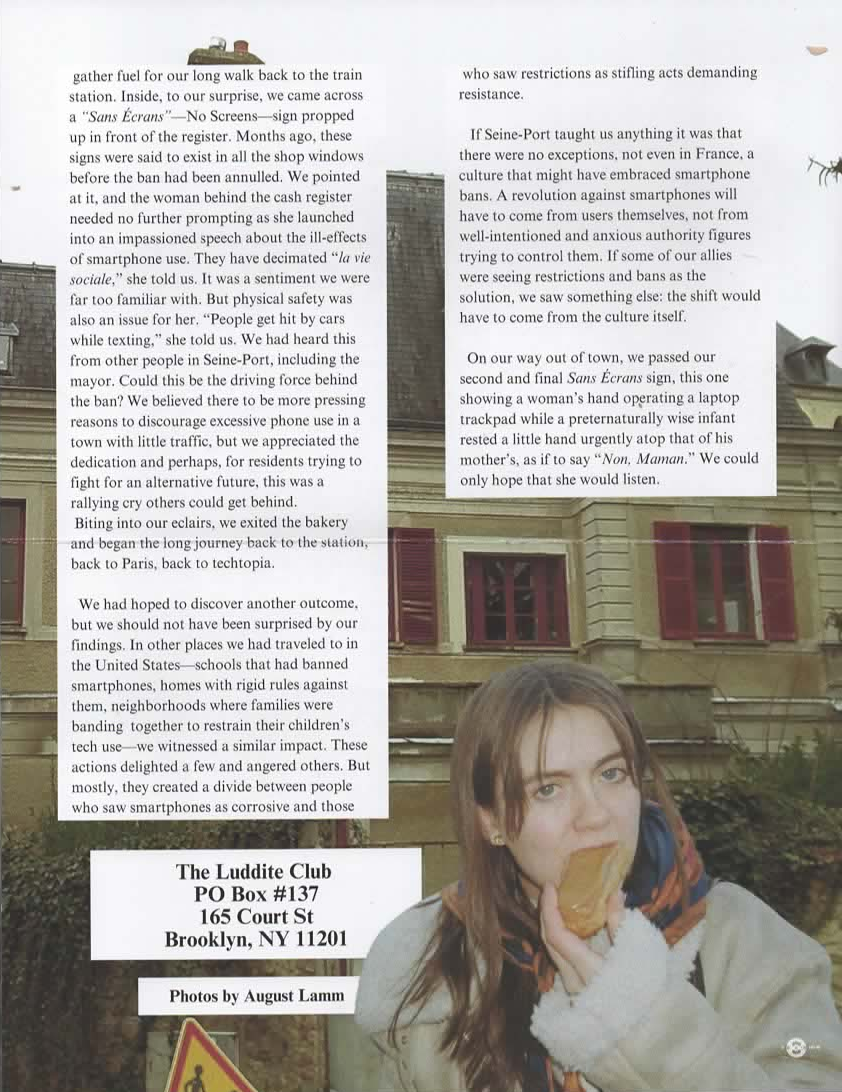

On our way out back to Paris, depleted and saddened we stopped at the town bakery to gather fuel for our long walk back to the train station. Inside, to our surprise, we came across a “Sans Écrans”—No Screens—sign propped up in from of the register. Months ago, these signs were said to exist in all the shop windows before the ban had been annulled. We pointed at it, and the woman behind the cash register needed no further prompting as she launched into an impassioned speech about the ill-effects of smartphone use. They have decimated “la vie sociale,” she told us. It was a sentiment we were far too familiar with. But physical safety was also an issue for her. “People get hit by cars while texting,” she told us. We had heard this from other people in Seine-Port, including the mayor. Could this be the driving force behind the ban? We believed there to be more pressing reasons to discourage excessive phone use in a town with little traffic, but we appreciated the dedication and perhaps, for residents trying to fight for an alternative future, this was a rallying cry others could get behind.

Biting into our eclairs, we exited the bakery and began the long journey back to the station, back to Paris, back to techtopia.

We had hoped to discover another outcome, but we should not have been surprised by our findings. In other places we had traveled to in the United States -schools that had banned smartphones, homes with rigid rules against them, neighborhoods where families were banding together to restrain their children’s tech use—we witnessed a similar impact. These actions delighted a few and angered others. But mostly, they created a divide between people who saw smartphones as corrosive and those who saw restrictions as stifling acts demanding resistance.

If Seine-Port taught us anything it was that there were no exceptions, not even in France, a culture that might have embraced smartphone bans. A revolution against smartphones will have to come from users themselves, not from well-intentioned and anxious authority figures trying to control them. If some of our allies were seeing restrictions and bans as the solution, we saw something else: the shift would have to come from the culture itself.

On our way out of town, we passed our second and final Sans Écrans sign, this one showing a woman’s hand operating a laptop trackpad while a preternaturally wise infant rested a little hand urgently atop that of his mother’s, as if to say “Non, Maman.” We could only hope that she would listen.

Vol. 1 — No. 3

October 2025 - Free

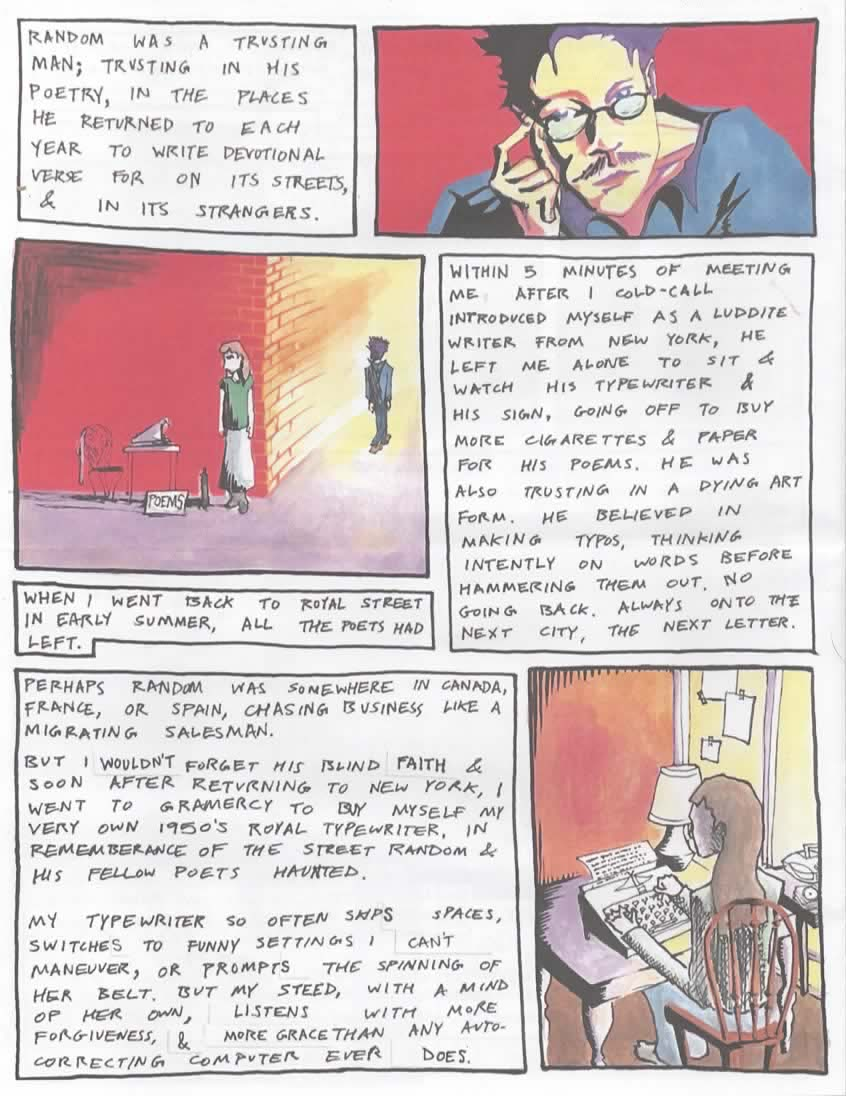

Trusting Typewriters In a Transient Town

Not a single person in the Orlando Airport was reading as I withstood a caffeine headache and waited for my flight to New Orleans.

On the flight, yet again, I sat next to a phone-gaming prodigy. This time: an 8 year old in spiderman crocs ignored by his busy father.

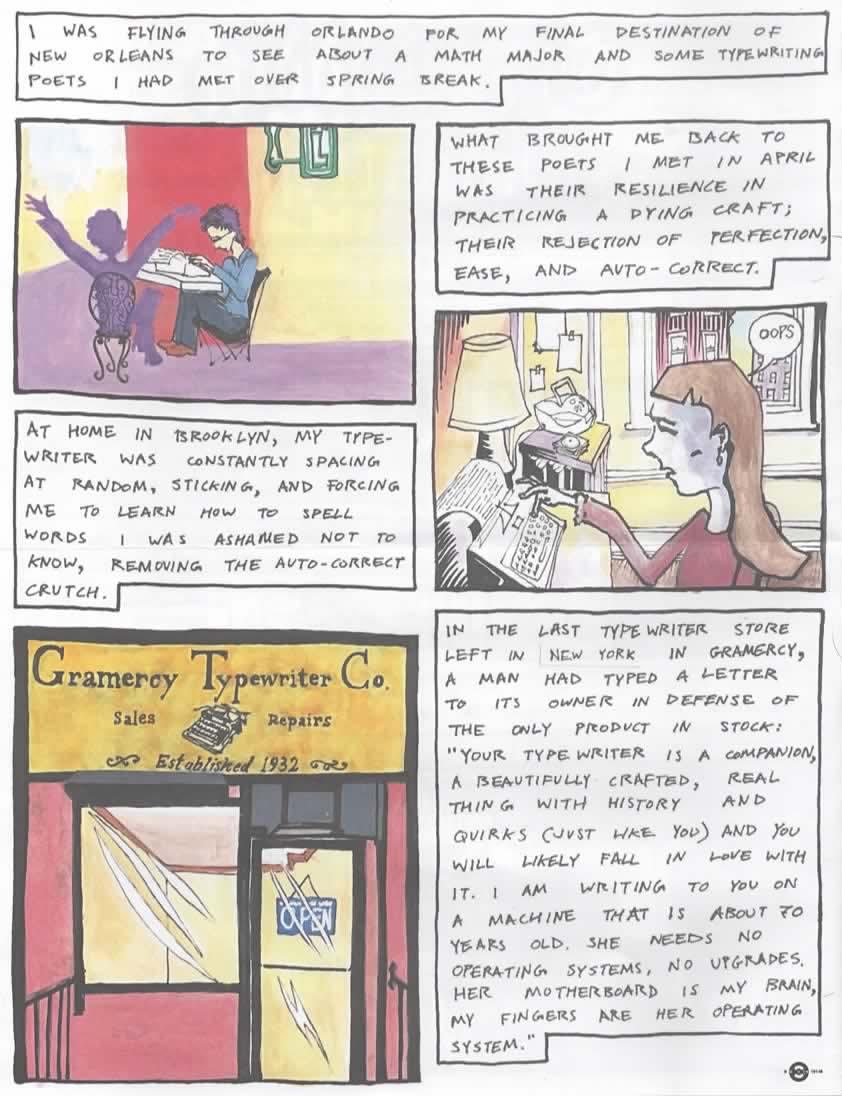

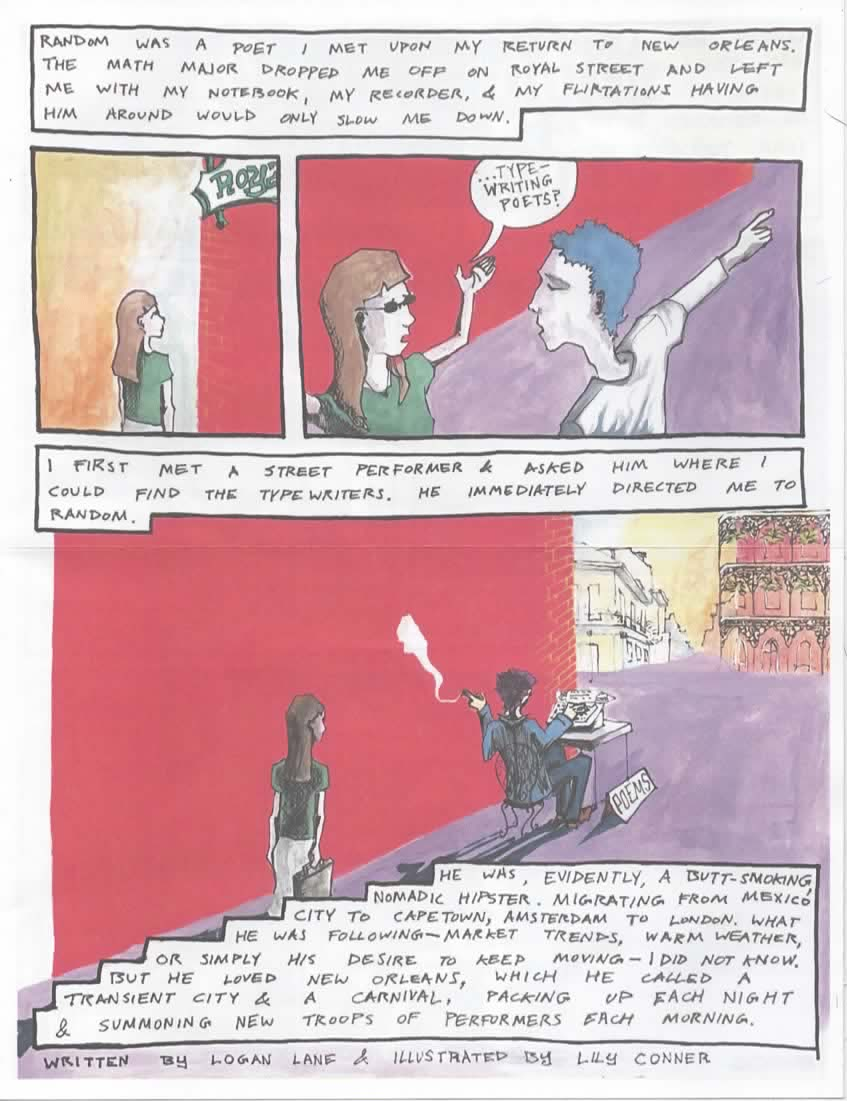

I was flying through Orlando for my final destination of New Orleans to see about a math major and some typewriting poets I had met over spring break. ...

For clarity also, the archivists who run this website are pro-tech anarchists, but we just find Ted Kaczynski's life story and impact interesting. So, we hope people can use the website to research various tech-critical ideas.