Janice M. Irvine

Marginal People in Deviant Places

Ethnography, Difference, and the Challenge to Scientific Racism

2022

Modern Social Differences and Race Science

Hyperlink 1.1: New Social Knowledge of Difference

Hyperlink 1.2: FBI Surveillance & Keen Video Interview

Rebranding: Hobo Art and Politics

Once a Hobo ... Nels Anderson’s Career

Hyperlink 2.1: Citing Bertha, on Queer Evidence

Hyperlink 2.2: Finding Hobo Graffiti

Hyperlink 2.3: A Conversation with Anthropologist Susan Phillips

Modern Chicago: Bright Lights, Big City

“From Where They Come in the City”: Mapping the Taxi-Dance World

Conclusion: Taxi-Dance Legacies

Hyperlink 3.1: “Life’s Gutters”: Popular Culture Represents the Taxi-Dance Hall

Hyperlink 3.2: The Well of Loneliness: A Queer Note?

Hyperlink 3.3: Chicago’s Taxi-Dance Halls

Hyperlink 3.4: Paul Cressey’s Censorship

The Works Progress Administration Projects

Field Research: The Worker Camps

Anthropometry, Race, Representation: One Doll’s Story

Lost and Found; Forgotten or Erased?

Hyperlink 4.1: Anthropometry of Barbie

Prehistory: Goffman and His Asylum

Medicalization and Its Challengers

Places, Territories, and the Difference Differences Made

Deinstitutionalization and Collapse

Hyperlink 5.3: Goffman’s Cultural Archive

Hyperlink 5.5: Vivian Gornick Interview

Deviant Insiders: The Breastplate of Righteousness

Laud’s Legacy: On Secrets and Shame

Hyperlink 6.1: Women and the Early Gay Canon

Hyperlink 6.2: Sex, Tearoom Trade, and the IRB

Hyperlink 6.3: Albert Reiss: Queers and Peers

Hyperlink 6.4 The Open Space of Glory Holes

The Knowledge Churn: Who Tells the Hippie Story?

Sherri Cavan: Outsider Women of Sociology

How the Haight Produced Hippies

Hippies Selling, Selling Hippies

We Are All Hippies Now—Or Are We?

Hyperlink 7.1: Countercultures, Moral Panics, and the National Deviancy Conference

Biography, Politics, and Research

Hyperlink 7.2: An Interview with Sherri Cavan

Hyperlink 7.3: Slumming Tours: The Spectacle of Social Difference

[Title Page]

Marginal People in Deviant Places

Ethnography, Difference, and the Challenge to Scientific Racism

Janice M. Irvine

University of Michigan Press

Ann Arbor

[Copyright]

Copyright © 2022 by Janice M. Irvine

Some rights reserved

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Note to users: A Creative Commons license is only valid when it is applied by the person or entity that holds rights to the licensed work. Works may contain components (e.g., photographs, illustrations, or quotations) to which the rightsholder in the work cannot apply the license. It is ultimately your responsibility to independently evaluate the copyright status of any work or component part of a work you use, in light of your intended use. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

For questions or permissions, please contact um.press.perms@umich.edu

Published in the United States of America by the

University of Michigan Press

Manufactured in the United States of America

First published July 2022

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data has been applied for.

ISBN 978-0-472-05538-8 (paper : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-472-90265-1 (OA)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11519906

[Dedication]

To Marsha Burke, my sister, and co-traveler through a marginal past.

And to my Portland friends, who welcomed a stranger.

Digital materials related to this title can be found on the Fulcrum platform via the following citable URL: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11519906

Illustrations

Preface

Figure 1. Howard Becker, piano, performing at the 504 Club in Chicago, circa 1950.

Figure 2. Mad magazine cover, December, 1971. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 3. Zora Neale Hurston collecting folklore, late 1930s. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 4. Early gay pride march, Mattachine Society of New York. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 5. Columbia University sociologist C. Wright Mills. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 6. Center Building, St. Elizabeths Hospital inWashington, D.C., circa 1900.

Figure 7. Lobby card for the 1927 film The Taxi Dancer. Available on Fulcrum.

Chapter 1

Figure 8. Book cover, Must You Conform? by Robert Lindner, 1956. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 9. Ernest Burgess course notes for Social Pathology, October 4, 1927. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 10. Cesare Lombroso, six figures illustrating types of criminals, 1888. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 11. W. E. B. Du Bois in his office, circa 1948. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 12. Georg Simmel, circa 1901. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 13. Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) demonstration, New York City. Available on Fulcrum.

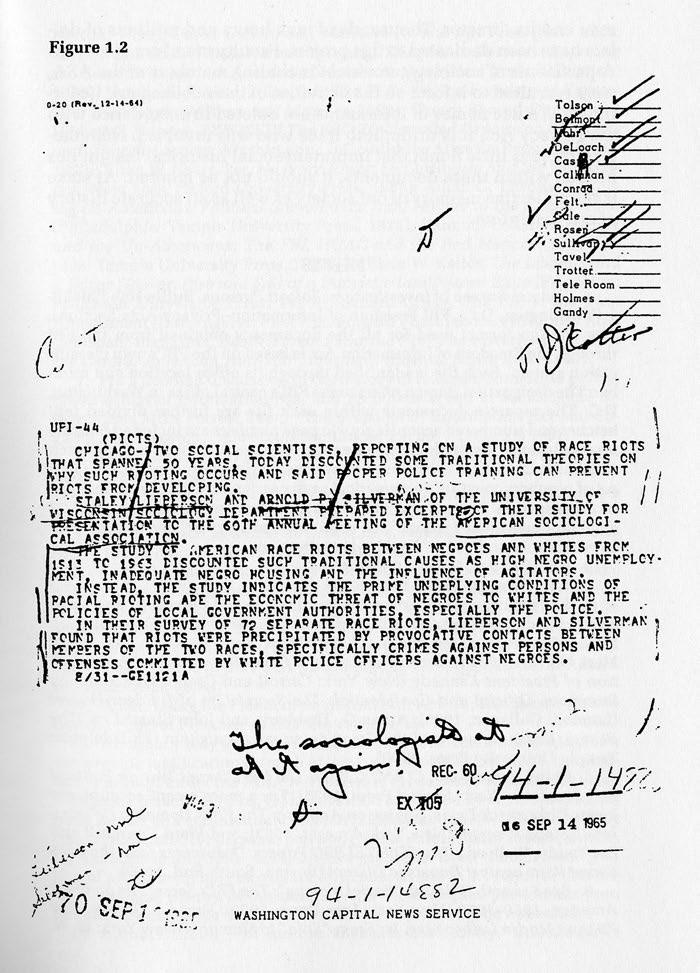

Figure 14. Federal Bureau of Investigation, American Sociological Association, September 14, 1965. Washington, DC: FBI Freedom of Information—Privacy Acts Section.

Figure 15. Street signs marking the intersection of Haight and Ashbury Streets in San Francisco. Available on Fulcrum.

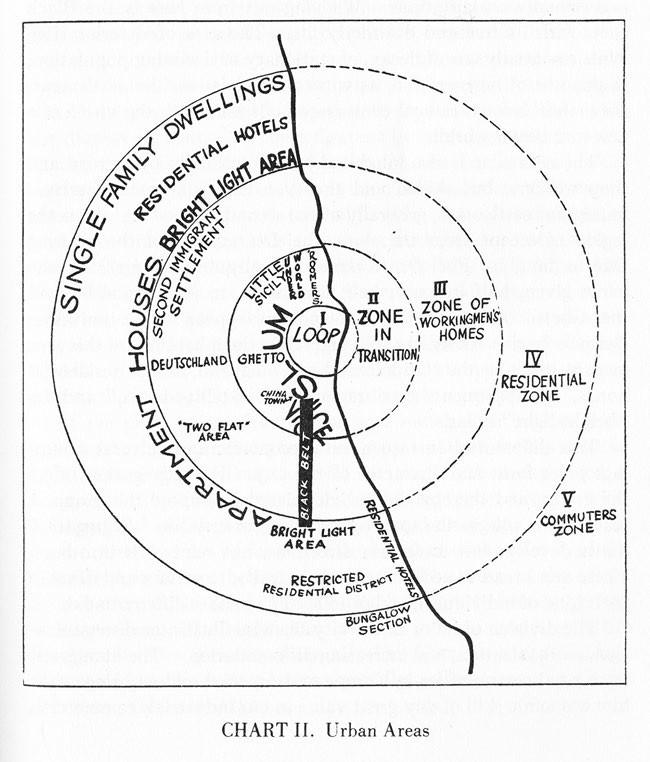

Figure 16. “Urban Areas,” map illustrating the growth of cities.

Figure 17. The sleeping porch in the Allison Building at St. Elizabeths Hospital, Washington, DC. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 18. Israel Levin Senior Center, December 2018. Available on Fulcrum.

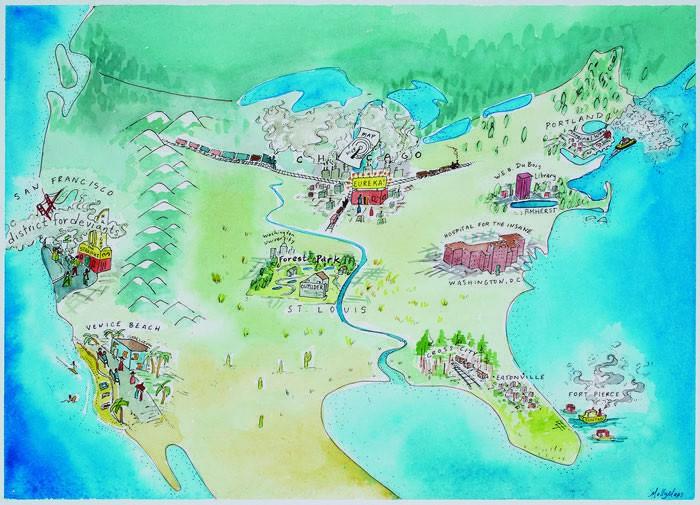

Figure 19 Marginal People in Deviant Places. Map by Janice M. Irvine ©. Artist, Molly Brown, South Portland, Maine.

Chapter 2

Figure 20. The National Hobo Museum, at the former Chief Movie Theatre on Main Street, Britt, Iowa. Available on Fulcrum.

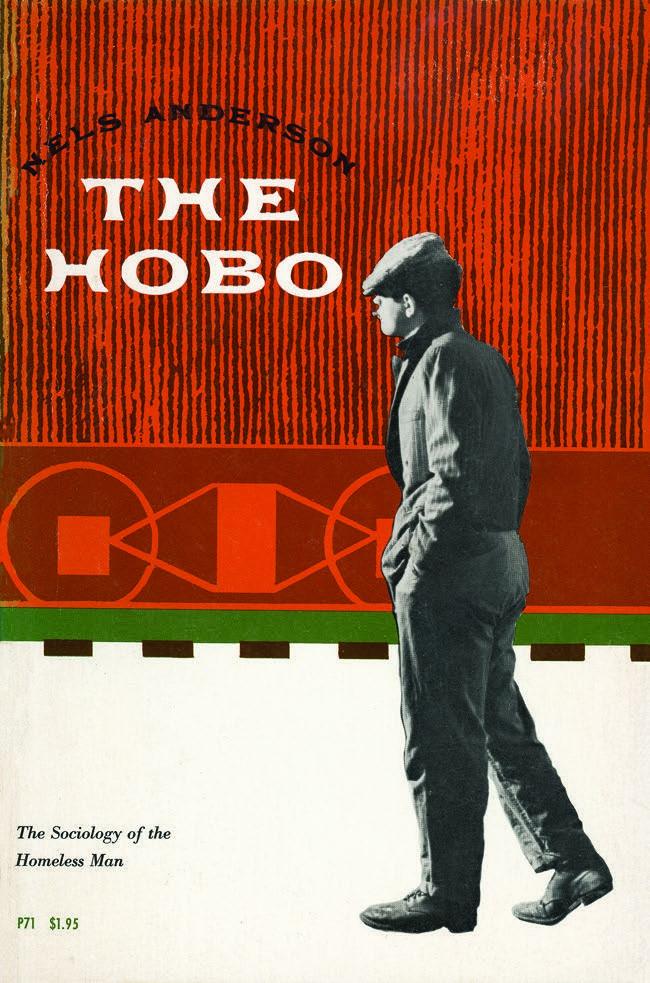

Figure 21. The Hobo, by Nels Anderson.

Figure 22. More than twenty-five years a bindle stiff. Photograph by Dorothea Lange, 1938.

Figure 23. Advertisement for the book, The Hobo, from the University of Chicago Press. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 24. Lou Ambers with a large bag mounting a train. Photograph by Alan Fisher, 1935. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 25. Front page of The Adventures of a Female Tramp, 1914, by hobo writer A-No. 1. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 26. Downtown Chicago intersection in the late nineteenth century, congested with horses, carts, carriages, and train cars. Available on Fulcrum.

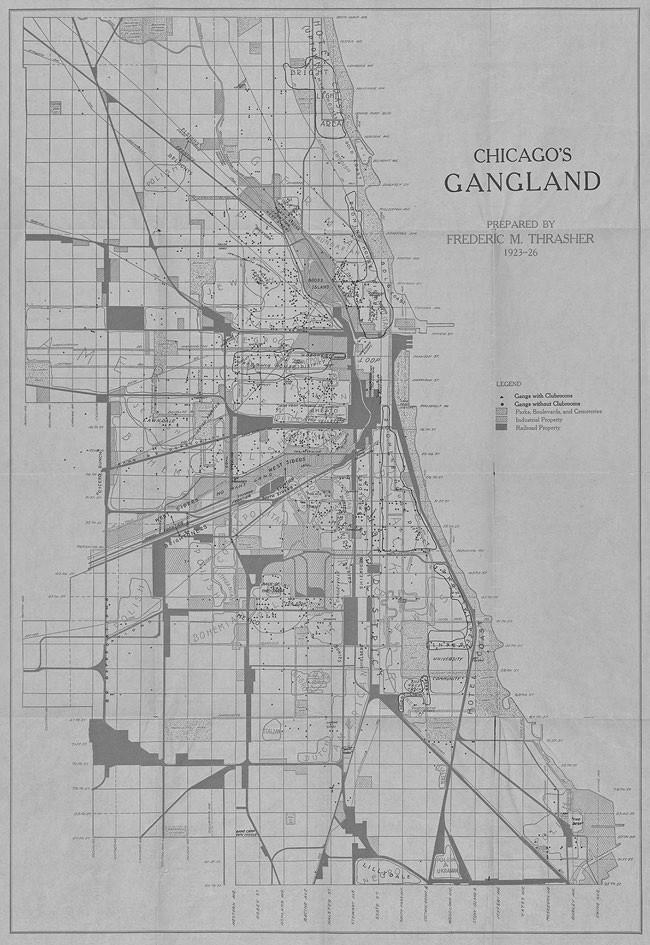

Figure 27. Chicago Gangland, 1927. Created by University of Chicago sociologist Frederic Milton Thrasher for his book The Gang: A Study of 1,313 Gangs in Chicago.

Figure 28. Nels Anderson included samples of menus from restaurants in hobohemian. From The Hobo: The Sociology of the Homeless Man, 1923. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 29. Century-old hobo graffiti found by anthropologist Susan Phillips under a concrete bridge of the L.A. River.

Figure 30. Lou Ambers cooking over a campfire, using a tin can on a stick. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 31. A squatter in Chicago, named Blackie, reading a newspaper in the type of living area Nels Anderson referred to as a hobo jungle. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 32. A boxcar located at the hobo jungle on Diagonal, one block off Main Street in Britt, Iowa. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 33. Russel-Morgan print of a tramp smoking cigar with cane over his arm, 1899. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 34. Charlie Chaplin as the Tramp. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 35. Physician and occasional hobo, Ben Reitman. From The Hobo: The Sociology of the Homeless Man, 1923. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 36. A poster by the International Brotherhood Welfare Association advertising a hobo rally and lecture entitled “The Hobo and His Welfare,” with Dr. Ben Reitman and James Eads How. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 37. Industrial Workers of the World, “The Little Red Song Book,” 1918. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 38. Publicity photograph of Charlie Chaplin for the film Modern Times, 1936. Available on Fulcrum.

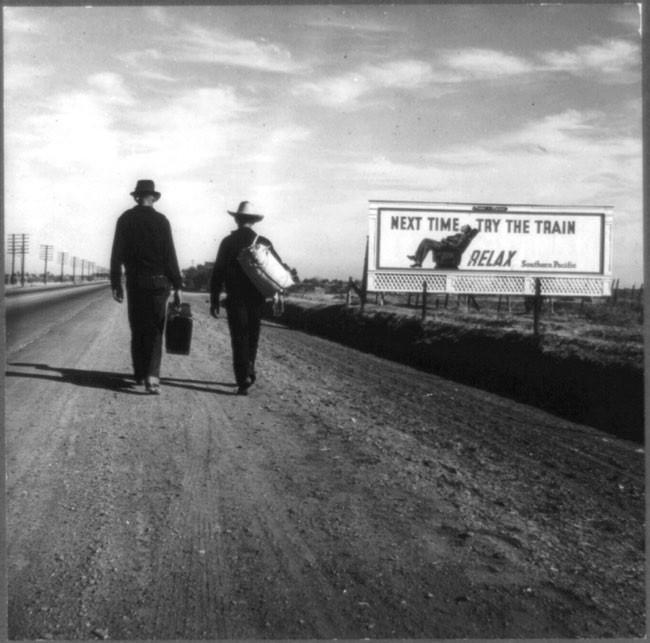

Figure 39. Toward Los Angeles, 1937.

Figure 40. Century-old hobo graffiti under a concrete bridge of the L.A. River. Available on Fulcrum.

Chapter 3

Figure 41. Film poster for 1931 Lionel Barrymore production, Ten Cents a Dance, starring Barbara Stanwyck. Available on Fulcrum.

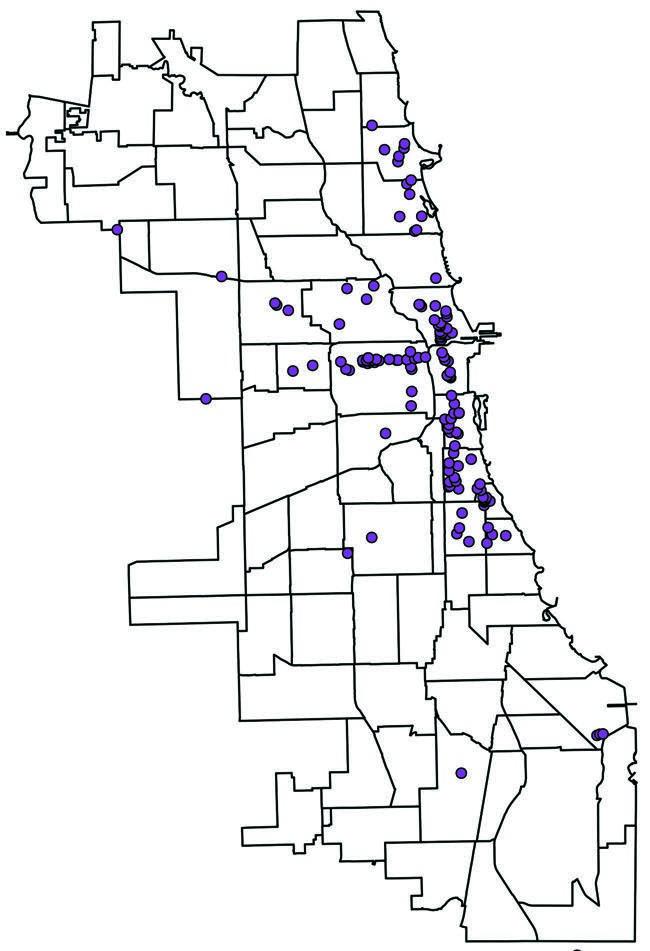

Figure 42. Chicago sex work establishments during the Prohibition era, 1920–1933.

Figure 43. A photograph of Jane Addams, cofounder of Hull House, in Chicago, was included in a gallery of Keepers of the Faith. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 44. Book cover of Hull House associate Louise DeKoven Bowen, The Public Dance Halls of Chicago. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 45. Cover of antidance treatise, From the Ball-room to Hell, 1892. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 46. Road map of Chicago and vicinity, produced by Cities Service Oil Company, 1937. Available on Fulcrum.

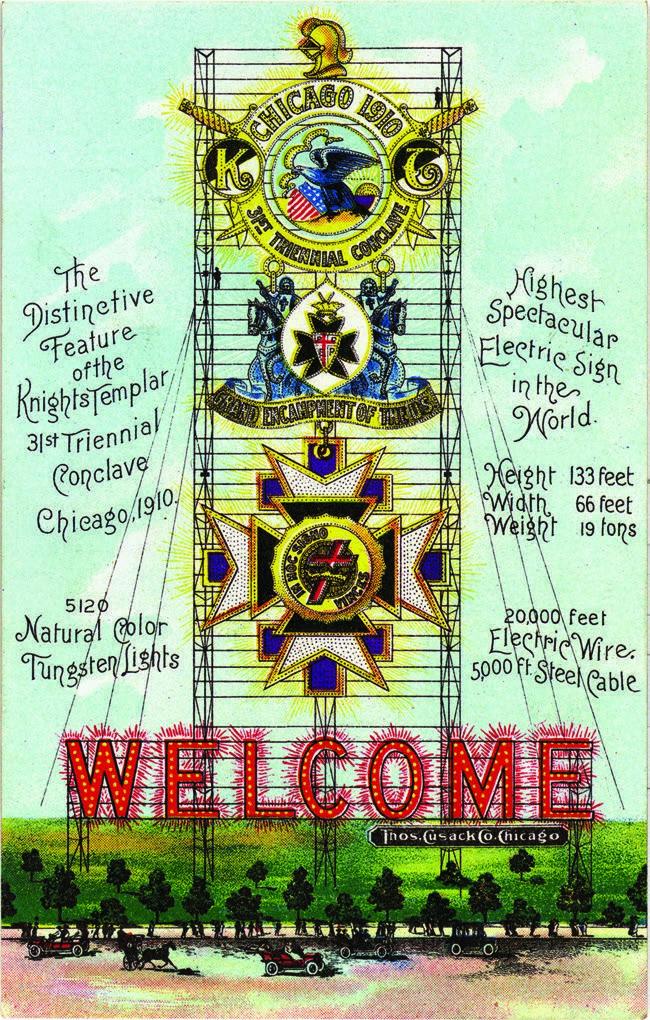

Figure 47. This Knights Templar postcard, of the 31st Triennial Conclave “Welcome” sign, held in Chicago, August, 1910.

Figure 48. System of Chicago Surface Lines, 1929. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 49. On the dance floor, 1938. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 50. The Migration of Negroes, 1890, The Georgia Negro. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 51. Nationalities Map No. 1—Polk Street to Twelfth, Halsted Street to Jefferson, Chicago. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 52. Paul Cressey’s map for The Taxi-Dance Hall text, “From Where They Come in the City.” Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 53. Paul Cressey’s base map of Chicago, marking the locations of taxi-dance halls licensed in 1927. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 54. Moral crusades against taxi-dance halls in Chicago and other regions of the United States were widely reported in newspapers. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 55. The Social Dance book cover, 1921. An antidance treatise by Dr. R. A. Adams that argues that dancing is both immoral and physically unhealthy. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 56. Paul Cressey’s book on taxi-dance halls received widespread coverage in the Chicago newspapers. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 57. A taxi dancer responded to the flurry of news coverage about Paul Cressey’s book, The Taxi-Dance Hall. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 58. Book cover, Taxi Dancers, by Eve Linkletter, 1958. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 59. Excerpt from Paul Cressey’s field notes in which he discussed seeing the book (which he misspelled) The Well of Loneliness. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 60. Book cover, The Well of Loneliness, by Radclyffe Hall. Available on Fulcrum.

Chapter 4

Figure 61. Road map of Florida, 1938. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 62. Zora Neale Hurston and an unidentified man, probably at a recording site in Belle Glade, Florida, 1935. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 63. Commemorative plaque celebrating Hurston as “Eatonville’s Daughter,” at the Zora Neale Hurston National Museum. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 64. Zora Neale Hurston as a student at Howard University, 1919–23.

Figure 65. Zora Neale Hurston and three boys, in Eatonville, Florida, 1935. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 66. Zora Neale Hurston, half-length portrait, at the Florida Writers’ Project exhibit, at the New York Times Book Fair, 1938. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 67. Florida: A Guide to the Southernmost State. Compiled and written by the Federal Writers’ Project of the Work Projects Administration for the State of Florida, 1940. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 68. Segregation at the bus station in Durham, North Carolina, 1940. Photographer, Jack Delano. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 69. Notes taken by Stetson Kennedy on dialogue between Zora Neale Hurston and Dr. Carita Coree, director of the Florida Writers Project about reporting of the Ocoee Incident. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 70. Zora Neale Hurston, with Rochelle French and Gabriel Brown, in Eatonville, Florida, 1935. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 71. Phosphate mine in the Bone Valley Formation region. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 72. Gulf, Florida & Alabama Railway Company turpentine camp, circa 1900.

Figure 73. Zora Neale Hurston, smoking a cigarette, at the Aycock and Lindsay turpentine camp, Cross City, Florida, 1939. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 74. Zora Hurston’s manuscript, “Cross City: Turpentine Camp,” written after her visit to the Aycock & Lindsay turpentine camp, 1939. Available on Fulcrum.

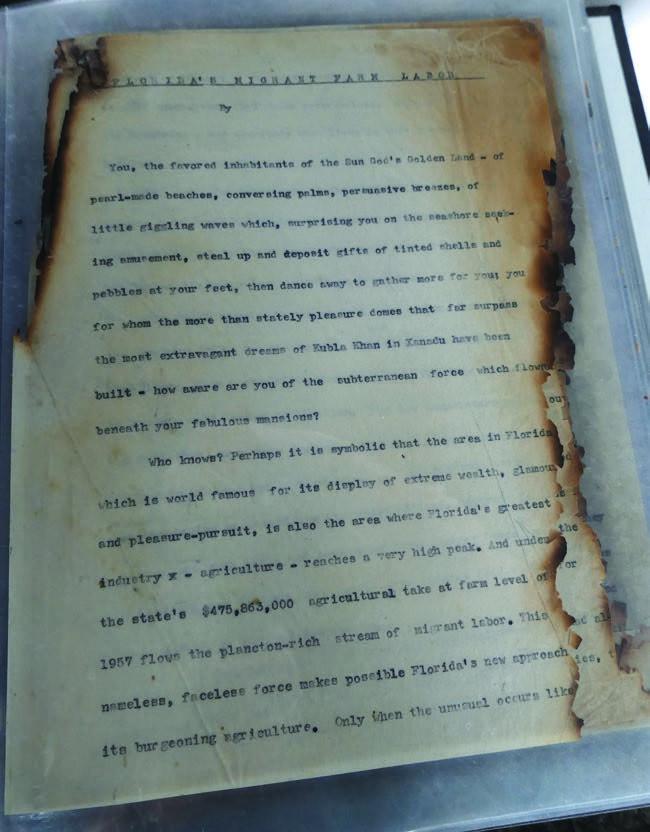

Figure 75. Burned, typewritten title page of Hurston’s article, “Florida’s Migrant Farm Labor.”

Figure 76. Newspaper advertisement for Negro dolls and the Negro Doll Company. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 77. Cover of anthropologist Melville Herskovits’s 1930 text, The Anthropometry of the American Negro. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 78. Eugenics Society exhibit, 1930s, advising visitors to “Marry Wisely.” Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 79. Flag, announcing lynching, flown from the window of the NAACP in New York City, 1936. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 80. Florida and the Railroad Barons map shows the expansion of rail lines in Florida, which bolstered industrial expansion in areas such as phosphate mining, sugar production, and myriad fruit and vegetable products. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 81. Trainman signaling from a Jim Crow coach, St. Augustine, Florida, 1943. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 82. Zora Neale Hurston and her car, Cherry. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 83. Cover of the Negro Motorist Green Book, by Victor Hugo Green, 1940 edition. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 84. Dell’s Café, Eatonville, Florida. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 85. People dancing, probably from the Georgia, Florida, and Bahamas expedition, 1935. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 86. Migratory laborers playing checkers in front of jook joint during slack season for vegetable pickers, Belle Glade, Florida, 1941.

Figure 87. Burned fragment from Hurston’s papers expressing her frustration with Southern racism. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 88. Letter from Zora Neale Hurston to W. E. B. Du Bois, June 11, 1965. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 89. Zora Neale Hurston moved to this single-story, stucco house in Fort Pierce in 1957. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 90. Zora Neale Hurston’s weathered cemetery marker at the Garden of Heavenly Rest Cemetery in Fort Pierce. Available on Fulcrum.

Chapter 5

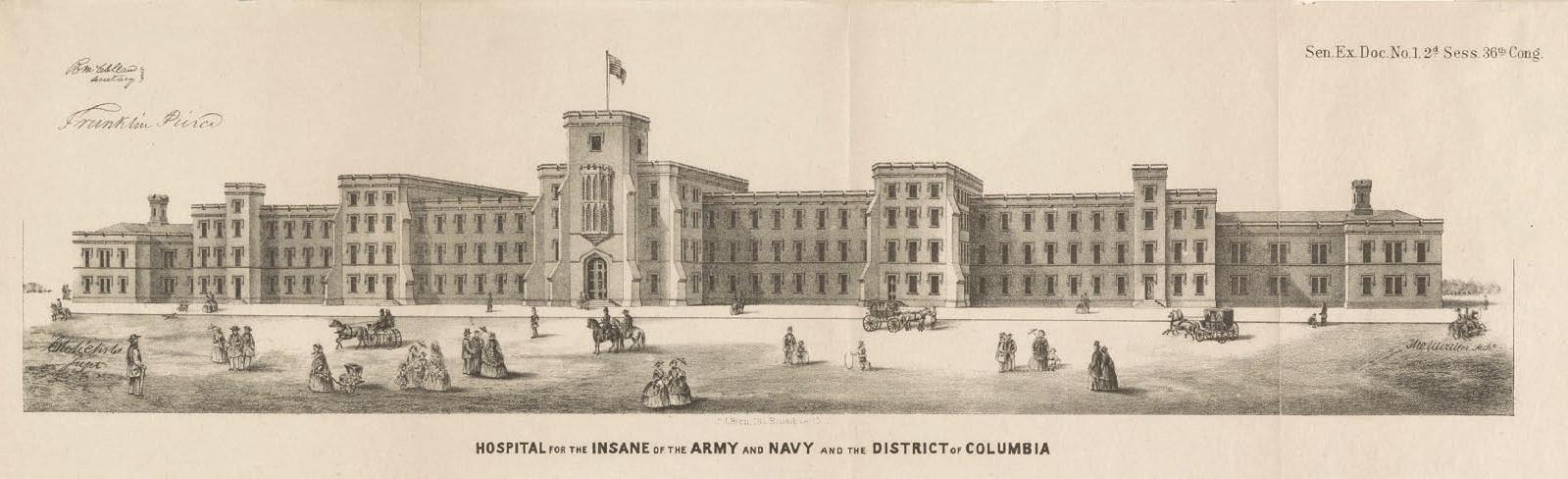

Figure 91. Hospital for the Insane of the Army and Navy and the District of Columbia, 1860.

Figure 92. https://arcg.is/1KvXfG0. ArcGIS map.

Figure 93. Surveillance dog in action by the Department of Homeland Security. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 94. Erving Goffman’s text, Asylums, 1961. Available on Fulcrum.

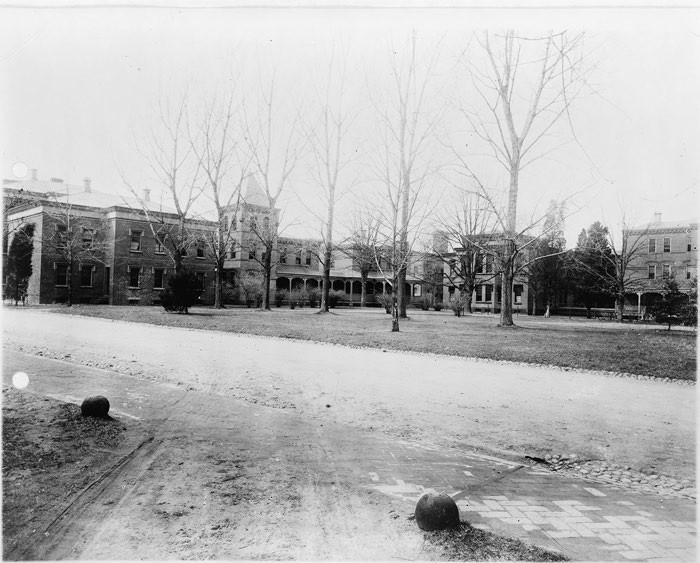

Figure 95. St. Elizabeths Hospital, Washington, DC, between 1909 and 1932.

Figure 96. Maps of St. Elizabeths Hospital, Washington, DC, circa 1860. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 97. The former Recreational Therapy Branch building on the St. Elizabeths campus. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 98. Two editions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 99. David Rosenhan. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 100. Original blueprint showing rendering of the Male Receiving Building at St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, DC, circa 1934. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 101. African American patients eating in a segregated dining hall in Building Q circa 1915. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 102. Indian Asylum, Canton, South Dakota. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 103. Historical highway sign in South Dakota marking the Hiawatha Asylum for Insane Indians. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 104. The Burroughs Cottage on St. Elizabeths campus, March, 2017. Available on Fulcrum.

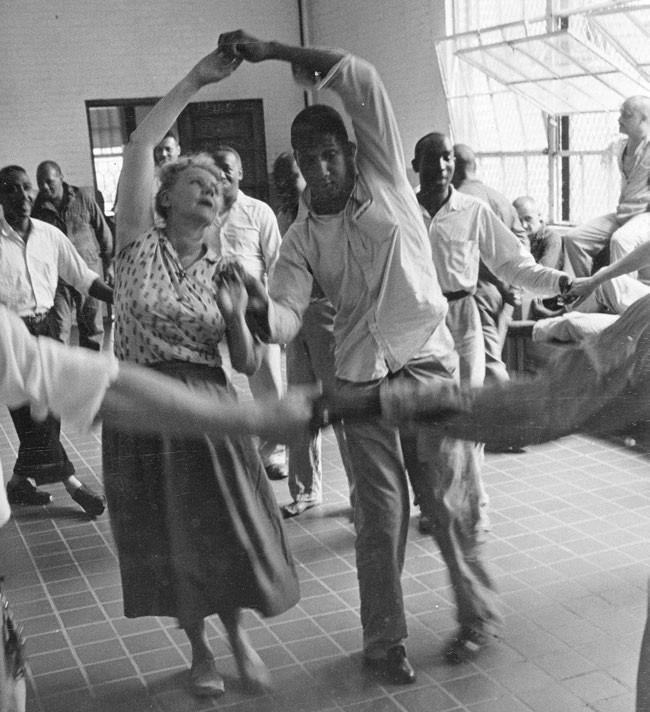

Figure 105. Marion Chace launched dance therapy at St. Elizabeths in 1942 and taught for several decades.

Figure 106. Ken Kesey in 1974. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 107. The 1946 novel, The Snake Pit. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 108. St. Elizabeths woman patient in a rocking chair. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 109. Advertisement for Haldol, the antipsychotic drug released in 1967. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 110. Book cover of a reader compiling articles from Madness Network News. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 111. Buildings remain closed and shuttered at St. Elizabeths Hospital, 2018. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 112. Aerial view of St. Elizabeths Hospital, west campus. Available on Fulcrum.

Chapter 6

Figure 113. Sociologist Laud Humphreys. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 114. Draft cover page of Laud Humphreys’s dissertation. Available on Fulcrum.

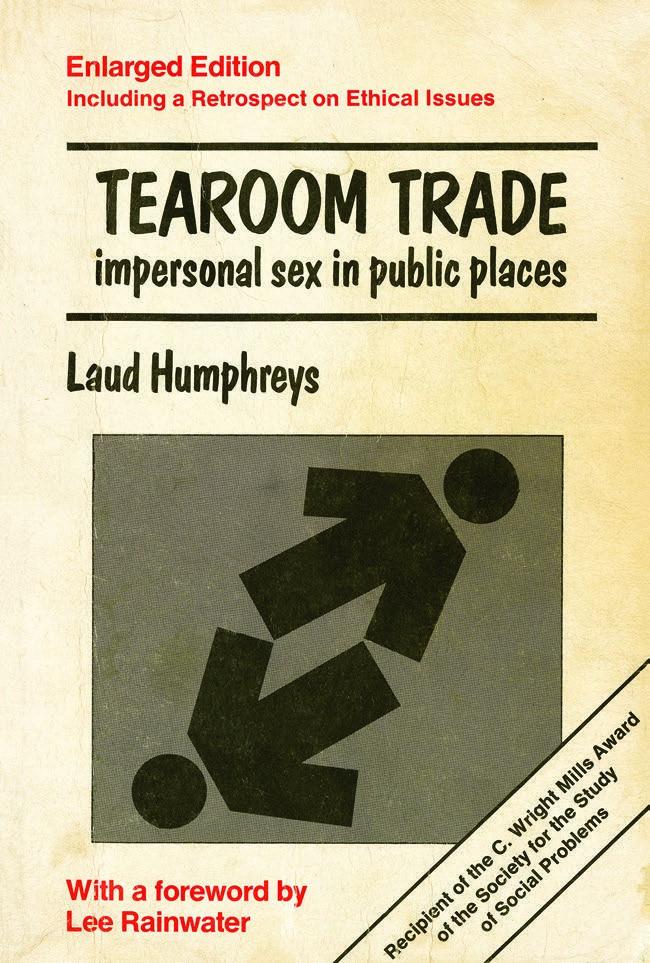

Figure 115. Book cover of a 1975 enlarged edition of Tearoom Trade: Impersonal Sex in Public Places.

Figure 116. New York State Historic Site plaque at the Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street, New York City, marking the uprisings in June, 1969. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 117. Laud Humphreys 1968 diary. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 118. Systematic Observation Sheet developed and employed by Laud Humphreys in recording tearoom encounters. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 119. Map of Forest Park indicating some of the restrooms that served as popular tearooms. Available on Fulcrum.

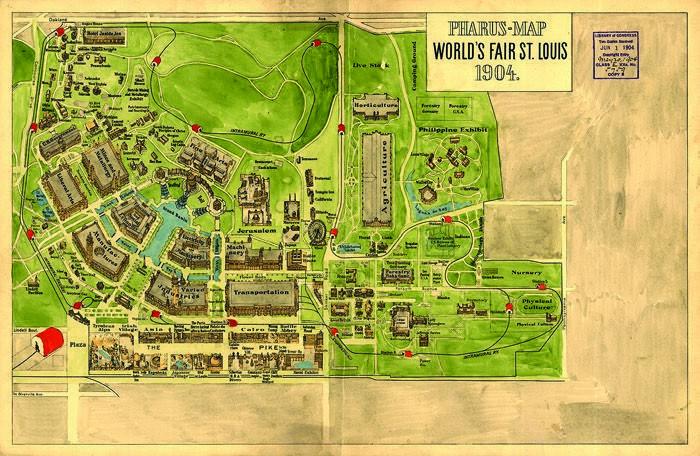

Figure 120. Map of the World’s Fair in St. Louis, 1904, also known as the Louisiana Purchase Exposition.

Figure 121. One of the outdoor restrooms in Forest Park.

Figure 122. Men’s restroom in the Minneapolis–St. Paul International Airport, where US Senator Larry Craig (R-Idaho) was arrested for lewd conduct. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 123. Advertisement by Guild Book Service for the report, “Homosexuality and Citizenship in Florida.” Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 124. Photograph of an apparent tearoom sexual encounter. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 125. Book cover of the fiftieth-anniversary edition of City of Night, by John Rechy, originally published in 1963. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 126. Laud Humphreys autographed a first edition of Tearoom Trade to his friend and colleague, sociologist Carol Warren. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 127. The physical altercation between Laud Humphreys and Alvin Gouldner was covered by the New York Times, headlined, “Sociology Professor Accused of Beating Student.” June 9, 1968. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 128. Laud Humphreys’s diary entries from May 20–21, 1968.Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 129. Sociologist and activist Mary McIntosh. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 130. Photograph of a glory hole published in a gay magazine. Available on Fulcrum.

Chapter 7

Figure 131. Traffic heading toward the Woodstock Music & Art Fair, August 16, 1969. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 132. Book cover, Sherri Cavan’s Hippies of the Haight. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 133. Cover of the first issue of the men’s magazine Playboy, December 1953. Available on Fulcrum.

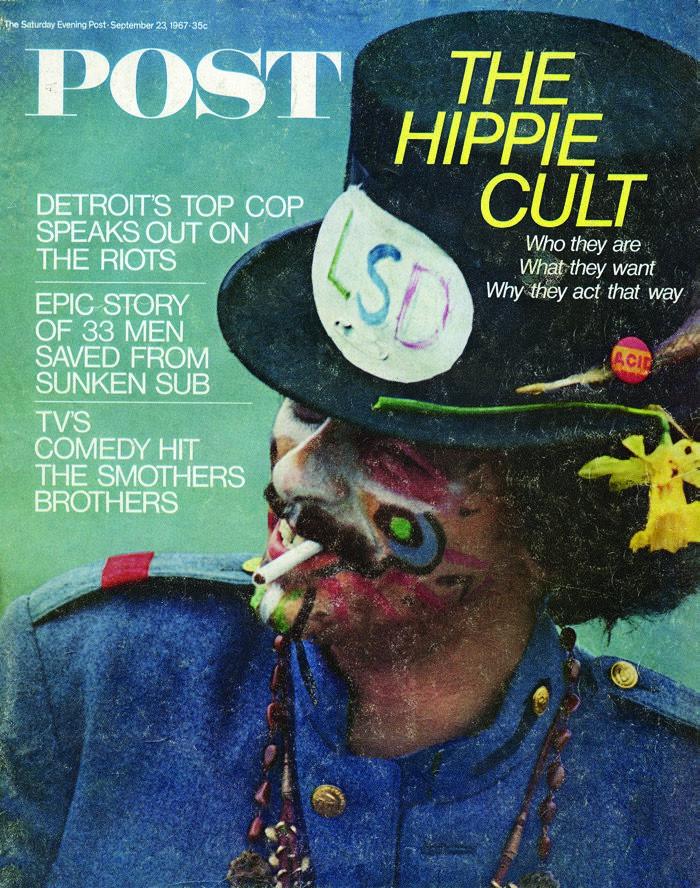

Figure 134. Cover of the Saturday Evening Post, September 23, 1967, which ran writer Joan Didion’s famous article, “Slouching Towards Bethlehem.”

Figure 135. The Death of Hippie funeral notice, scheduled in Haight Ashbury for October 6, 1967, attributed the hippie’s death to mass media. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 136. Sociologist Sherri Cavan at her home in Haight Ashbury stands in front of some of her sculptures, 2014.

Figure 137. Street signs mark the famous intersection of Haight Street and Ashbury Street in San Francisco. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 138. 1967 Screen print of San Francisco represents the city’s art and music scene. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 139. Sherri Cavan’s house on Page Street in 2014. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 140. Hippie is a Straight Theater Celebration, 1967. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 141. Hippie is making mandalas, 1967. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 142. Tourists peer out a bus window on the Gray Line bus company’s “Hippie Tour,” 1967. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 143. Hippies with marijuana stash in an apartment, 1969. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 144. The Jimi Hendrix Red House, Haight Ashbury. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 145. Janis Joplin performing in 1969. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 146. Hippie is salesmanship, 1967. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 147. Hippie is getting busted. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 148. Newspaper article reporting the Death of Hippies ceremony at Buena Vista Park, 1967. San Francisco Chronicle. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 149. Haight Ashbury continues to attract tourists to shops commercializing the region’s hippie history. Available on Fulcrum.

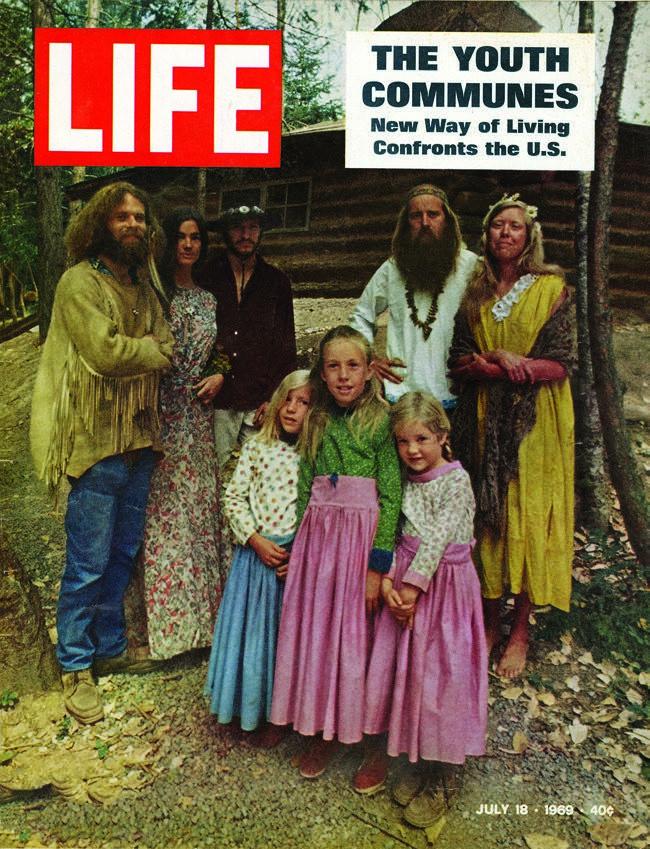

Figure 150. Life Magazine cover depiction of the new youth communes as a confrontation with the United States.

Conclusion

Figure 151. Number Our Days book cover. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 152. Barbara Myerhoff, with members of the Israel Levin Senior Adult Center.

Figure 153. Israel Levin Senior Adult Center. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 154. Colorful murals on Israel Levin Senior Adult Center. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 155. Gathering Place on the Bench. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 156. Life Not Death in Venice protest. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 157. K.O.S. protest.

Figure 158. Act Up members engage in street protest, circa late 1980s. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 159. Queer and Queer Nation. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 160. Senior Center demolition. Available on Fulcrum.

Figure 161. Bench outside Israel Levin Senior Adult Center, December, 2018.

Acknowledgments

Writing about deviants is exciting. Until it isn’t. On the one hand, this has been the most fun I’ve ever had doing research. It involved my favorite activities: travel, exploring archives, and talking to people. This project deepened my recognition of how my life has been so profoundly constructed by knowledge, art, and politics by, and about, those of us on the social margins. On the other hand, this book brought more than its share of heartache. For one thing, people died. The news, by email or word of mouth, that one of my interviewees had died brought a lingering sadness. This was a historical project, and poring over obituaries and reports of memorial services for an earlier generation of scholars kindled a new poignancy about their lives and work. This bittersweet reminder that I, too, am simply a small part of a longer tradition of rethinking difference led me to locate myself on the map of scholars and our research places that I designed for this book. Additionally, it is an understatement to note that immersion in histories of relentless racism, sexism, and homophobia was painful. The persistence of bias, injustice, and stigma toward unconventional ways of living and unconventional forms of knowledge is dispiriting and enraging.

This project would not have become a book without Sara Cohen. It was an easy decision to follow her to the University of Michigan Press after our several years of rich collaboration at Temple University Press. I’m grateful for her unwavering faith in this book and my writing process, for her incisive comments on multiple drafts, and for generally putting up with me. Many thanks to University of Michigan Press for producing a beautiful book. Likewise, I was lucky to have two anonymous reviewers whose very smart comments made this a better book.

It has always amazed me how generous people are with their time and memories when they agree to do interviews! Many thanks to the numerous scholars, artists, and activists who agreed to talk with me, and to those who participated in video interviews. Your insights and stories lent depth and nuance to my thinking about the texts, places, and time periods I’ve explored in this book. Every interview was a powerful reminder of the interconnectedness of personal and historical dimensions in the production of knowledge about social difference.

I received crucial institutional support for this project from several sources. Many thanks to the American Sociological Association for a grant from their Fund for the Advancement of the Discipline, and to the University of Massachusetts for a Social and Behavior Sciences Faculty Research Grant. A stipend and digital support from the University of Massachusetts’s Innovate program supported a very early pilot chapter, “Asylum Stories,” built as an Open Educational Resource on the Scalar platform. I’m deeply grateful to Michele Turre, our uber-competent senior instructional technologist, for her “assistance” on that project, which basically consisted of her building everything while I sat next to her, watching. Likewise, I received crucial digital support from UMass Amherst IT, Instructional Innovation. The UMass SOAR Fund and the College of Social and Behavior Sciences offset the subvention cost necessary for publication. In our year-long seminar in the Institute for Social Science Research Scholars Program, faculty members, particularly cofacilitators Naomi Gerstel and Laurel Smith-Doerr, provided helpful feedback on tender, early drafts. Laurel’s enduring enthusiasm for my work helped me think this deviant project was viable. Finally, the Conti Fellowship from UMass was an unexpected and welcome gift of release time for a year-long focus on research and writing.

The cover image, Untitled 1987, is by the Australian artist, poet, and mental health advocate Graeme Doyle (1947–2021). Doyle’s art is held in The Cunningham Dax Collection, Melbourne, Australia, which notes that Doyle, who experienced a long-term struggle with mental illness, “identified himself as an ‘outsider artist,’ intentionally acknowledging his position on the margins.” Doyle’s outsider art, which depicts complexity and stigma related to mental illness, resonates powerfully with this book’s themes of outsiders, marginality, and difference. Many thanks to Julia Young at the Dax Centre, who facilitated permission to feature Doyle’s painting on the cover.

A huge shout-out to archivists and librarians! The interlibrary loan staff at UMass delivered at warp-speed the vast range of sometimes-obscure materials I requested over the years. I worked in several special collections, and I’m grateful for the friendly efficiency of the many archivists there: the University of Chicago, the London School of Economics, Northeastern University, the University of Southern California, the New York City Public Library, the University of Florida, the University of Massachusetts, and ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives. Thanks also to Sarah Leavitt, curator at the National Building Museum, for helpful conversations about St. Elizabeths and comments on an early draft chapter. My last research trip unfolded, and unraveled, in Florida during the week of March 9, 2020. When it became clear I would have to change my flight and go home early, I rushed to the University of Florida special collections a day ahead of schedule. Many thanks to Flo Turcotte, literary manuscripts archivist, for rearranging her schedule to come to the library to chat about Zora Neale Hurston and facilitate my collection of digital images. It was the day the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic, and Flo was the last archivist I spoke with in person for a very long time.

Finishing a book in a pandemic was, well, basically like doing anything else in a pandemic—scary and hard. Several months into lockdown, with pretty much everywhere, including UMass, closed, I left Northampton, Massachusetts, and moved to Portland, Maine. For many months I was lost, in every sense of that word. I mourned the sudden absence of local friends and colleagues, and was untethered from institutional resources. I’m grateful to fellow sociologist Wendy Chapkis at the University of Southern Maine for academic collegiality, friendship, and for directing me to the phenomenal Osher Map Library at USM. Executive Director Libby Bischof and Osher Professor Matthew Edney were welcoming and generous on my first pandemic-era visit back to an academic space. Libby and Matthew, along with Bob Spencer and Louis Miller, located and then produced high-resolution scans of several fabulous maps in this book. Thank you all for your kindness to a displaced scholar!

Portland offered additional supports, in ways unexpected and moving. For one, soon after arriving there, I decided to create a graphic representation of all my research sites. Although I brainstormed ideas for this conceptual map, I had no idea how to artistically render such a thing. Unexpectedly, I found an artist who is also a geographer! I’m exceedingly grateful to Molly Brown, of MollyMaps in South Portland, for her collaboration in turning my fantasy map into reality. Colleen Bedard also gave me helpful artistic advice during my early mapmaking foray. Additionally, after a chance conversation on a freezing, masked, January Meetup beach walk, Barbara Cray generously volunteered to edit my videos for me (Sara Cohen heroically picked up the ball at the end.) Finally, my new Portland friends regularly asked how the book was going, fed me, patiently explained my new city and state to me, and invited me to that classic Maine cultural experience, “camp.”

Then there are the other all-important people. Like many academics, my intellectual webs traverse state and national borders. Without naming them all, I newly appreciate, in their abrupt dislocation during the pandemic, how ambient connections to broader intellectual conversations shape our work. Zoom and Skype helped them endure. In different ways, my closer circle of scholars has strengthened this work and kept me sane-ish: Kathy Davis, Arlene Stein, Regina Kunzel, Katie Young, Jackie Urla, Sarah Babb, Jen Lundquist, and Jon Wynn. Finally, Barbara Cruikshank, along with everything else, helps me remember myself as a scholar. You have all talked me through this project’s broader frameworks and finer points of analysis, the roller-coaster of thinking and writing, and life’s pleasures and vicissitudes during ten years of research. Just knowing you are out there has made all the difference.

Preface

We tell ourselves stories in order to live. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices.[1]

Joan Didion

In mid-twentieth-century publishing, “the outsider” arrived. Four books—all similarly entitled “outsider”—highlighted a robust cultural visibility of, and curiosity about, those who defied social convention. During the McCarthy-era Red Scare, the Harlem Renaissance writer Richard Wright explored themes of racism, segregation, and the American Communist Party in his 1953 novel The Outsider. The 1956 book by working-class English writer Colin Wilson, The Outsider, surprised everyone, including the author, by becoming an instant bestseller. Heralded as capturing “a representative theme of our time ... of our deepest predicament,” the book explored writers who fled a “cow-like” herd mentality to seek a deeper existential truth.[2] S. E. Hinton’s novel a decade later, The Outsiders, about marginalized, working-class teenage “greasers,” inspired a film adaption by Francis Ford Coppola. Recently, actor and writer Lena Dunham wrote that “over 50 years later” The Outsiders “has never felt more relevant—or true.”[3] Finally, sociologist Howard Becker’s 1963 essays featuring dance musicians, Outsiders, helped turn the social science of difference on its head.[4] It was the century of the outsider.

These authors wrote against the grain of Cold War, midcentury conformity. They all described themselves as outsiders, and their characters struck similar chords in their critique of social conventionality. Richard Wright’s outsider, Cross Damon, represented “a black man’s attempted escape from stable, essentialist forms of identity, including race.”[5] Colin Wilson celebrated the alienation of his artistic outsiders, Hinton’s gentle juvenile delinquents overcame the stigma of poverty to become heroes, and Becker indicted those who made and enforced social rules, thereby creating “outsiders” of his then-edgy marijuana-smoking musicians. And yet, as suggested by the almost simultaneous publication of these books, the outsider theme already had an enduring cultural presence. From the turn of the twentieth century, social marginality had been growing increasingly visible, whether through hierarchies of racial, national, gender, or economic inequality, or as the margins chosen by bohemians and political radicals. Paradoxically, outsiders were also, well, popular! At least, some of them were. And discovering which outsiders could be marketed and sold would become central to what I call “outsider capitalism.”

Together, sociology, popular culture, political activism, and even the process of commodification all reflected and produced this zeitgeist of the outsider. As literary critic Carla Cappetti has argued, urban sociologists and novelists “intellectually rubbed elbows” and served as reference points for each other.[6] University of Chicago sociologists had a direct impact on the novels of key early-twentieth-century writers such as Richard Wright, James T. Farrell, and Nelson Algren. Conversely, Roger Salerno dubs the work of Chicago School scholars “sociology noir” for its overlapping sensibilities with noir popular culture.[7] In addition, emerging forms of technology enabled innovative cultural production such as television, film, and photography. For example, mid-twentieth-century photographer Diane Arbus notoriously challenged positivist and eugenic theories of knowledge and scientific categorization within documentary photography and celebrity portraits, with her conceptual reversals of the freakish and the normal.[8] Mad magazine, founded in 1952, fostered a new deviant aesthetic of quirky, outsider critique. Alfred E. Neuman (the E stands for Enigma) helped a generation of young people develop a posture of snarky wit. These myriad outsider stories intertwined to make visible the perils, pleasures, and politics of difference.

This, too, is a book about outsiders. It explores cultural ideas about strangers, marginality, deviance, and differences. The social-scientific knowledge production about difference is its central theme. I explore different stories we tell about differences, and how those have changed, and not changed, over time. When this book begins, in the early twentieth century, race science produced the dominant narratives about human variations. Biological theories of difference produced a narrative othering that produced and reinforced caste hierarchies of race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, social class, mental status, age, and other variations. Discourses on nature and biology framed otherwise benign human differences as unnatural, deficient, and even dangerous.

In contrast, during this same period, some social scientists reconceptualized scientific knowledge, theoretical frameworks, and languages of human differences. They honed ethnographic practices to capture the diverse worlds of differences and outsiders, and of the places they inhabited. They rewrote social knowledge about differences, against the individualizing pathologies of scientific racism. Instead, these scholars told complex stories about social worlds of marginality, inequality, exclusion, and stigma, as well as vibrancy, creativity, and rebellion. They uncovered cultural logics in the social worlds of those who were nonconformist and different, and developed new ideas that blurred the boundaries between normalcy and deviance.

This book examines those early- to mid-twentieth-century redefinitions of difference. Each chapter is a time capsule, following a classic or little-known ethnographic text published between 1923 to 1978, or, in the case of anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston, a body of her ethnographic research in Florida. The book explores hobos and taxi dancers and their immigrant dance partners of early Chicago. It traverses the social worlds of rural, southern African Americans brought to life by Hurston. It journeys through the asylums inhabited by midcentury mental patients, the “tearooms” of men having public sex, and the Haight Ashbury hippie district. We end with elderly Eastern European Jewish immigrants at a Venice Beach senior center.

These snapshots of ethnographic knowledge production illuminate ways of knowing about difference in specific historical moments. In this book, I braid together the stories told by the ethnographic text with the meta-story of how the story was crafted. These stories about the story explore the where, how, and when of the authors’ projects, such as their methods, theoretical frameworks, and intellectual networks (or absence of them), as well as the challenges and support they encountered in their research. The historical, cultural, and political contexts—the experiences of researchers—influenced what stories could be told and who could tell them.

The chapters tell multifarious stories about modern outsiders, weaving the ethnographers’ tales together with other sources of journalistic, artistic, and political evidence. As such, I tell my own stories of outsiders and outsider scholarship through the lens of these ethnographic texts. These tales depict textured, nuanced social worlds, with some common themes, such as norm defiance, boundary-crossing, hierarchies of bias and social worth, and stigma. They show how difference was lived in a daily way, including, in some cases, the differences of the scholars themselves.

Three interlaced themes weave throughout and organize the chapters. The central theme is a critical history of the making of social knowledge about difference, in which social researchers challenged the dominant narrative of scientific racism. A disparate cohort of early- to mid-twentieth-century scholars engaged with new social worlds, human differences, and emerging social types emblematic of modernity. Early social theorists and ethnographers, culminating with later sociologists of deviance, rewrote the stories of strangers and outsiders. The second major theme is a social history of certain American outsiders. I explore the types of stories social researchers told about overlapping domains of difference. These differences include intersections of race, class, gender, sexualities, and age. However, my conceptualization of difference is more capacious. It features a wide swath of social outsiders and marginal figures who arose in early to mid-twentieth-century modernity, such as hobos, taxi dancers, and hippies. The third theme unites the first two by considering how specific places shaped the emergence of modern outsiders and the ethnographic writing about them.

Several subplots emerge within these central stories. One focuses on how social changes associated with modernity and capitalism gave rise to new forms of difference. A second explores a long-standing American paradox by which social differences are both despised and desired, and conformity is disdained yet enforced (I use the term “American paradox” because my focus in this book is largely on the United States, not because I am making an argument that this dynamic is uniquely American). A third explores the rise of an outsider capitalism that packaged and marketed social difference. Finally, we see how ethnographic stories of difference were entangled with those of artists, popular writers, and the political activism of outsiders themselves. These subplots appear when pertinent, and not all of them feature in every chapter.

There is a lot going on here. However, the multiple themes and threads underscore one of my key points. These ethnographic approaches to studying the social worlds of others opened up new questions and avenues for exploration—in this case, my own—rather than foreclosing curiosity with determinist explanations. In 1959, sociologist C. Wright Mills argued that we can only understand individuals, and this would certainly include strangers, outsiders, and deviants, by locating them within their specific social and cultural circumstances. Mills called this capacity to grasp the intersections of biography and history “the sociological imagination,” a term we instantly embraced.[9] I have allowed myself the freedom to follow my own sociological imagination down the various paths that beckoned.

This book tells stories about stories that echo through the decades. Several overarching claims interconnect chapters. First, I argue that early social scientists—certain sociologists and cultural anthropologists—were crucial to an epistemic departure from the ideas of race science. Ethnography, and later sociological deviance studies, didn’t change the master narrative of scientific racism. However, they represented a critical rupture to the cultural authority of scientific racism, producing new forms of social knowledge. By “critical rupture” I mean an interruption or a break from the past, in this case from the dominant knowledge production of race science.[10] Despite early ethnography’s shortcomings—for example, its partial essentialism and exoticism—it introduced other stories of difference into mainstream culture. The ethnographic texts of early sociologists were generally characterized by attempts (not always successful) at moral neutrality and a benign, and increasingly respectful, stance toward social differences.

Second, I show how, by midcentury, sociologists developed key concepts by which to analyze difference differently. The sociology of deviance, as it came to be known, built on earlier sociology of strangeness and marginality. While deviance studies suffered conceptual limitations now apparent from our contemporary historical context, the field nonetheless posed an epistemic challenge to race science through its anti-essentialist approach to differences. I argue that these theoretical advances served as bridge ideas between early ethnographic departures from race science, and later poststructuralist, feminist, and queer approaches to difference. Their work resonates with ongoing cultural and political battles over social differences, nonconformity, privilege, and exclusion. Sociologists Scott Frickel and Neil Gross argue that the emergence of scientific/intellectual movements is generated by high-status actors in prestigious positions.[11] However, the pioneering sociologists of deviance were arguably the first generation of scholars who were able to study marginality from positions as marginal women and men themselves, sometimes openly as outsiders. As such, some were beset by the same stigma as the marginal communities they studied.

Third, I suggest to readers that social knowledge has emotional valences. This book is about knowledge production, not knowledge reception. I can only posit to the reader that different intellectual questions and ways of knowing can shift the affective register of difference knowledge. Cognition and emotion are intertwined. The ideas, vocabularies, and symbols of discourses represent, as cultural theorist Raymond Williams said, “not feeling against thought, but thought as felt and feeling as thought.”[12] This is particularly evident in knowledge about difference. There is a deep affective component to our cultural ambivalence toward difference. Nonconformists are suspect and demonized, while also charismatic and seductive. The outsider is both hated and cool, in a dense affective mix. I suggest that the divergent narratives of race science and ethnography spoke to opposites poles of this paradox. Knowledge can support and produce feelings of fear, anger, and hatred. Or it can support and produce curiosity, acceptance, and appreciation. I believe our long history of political culture wars evinces this dynamic.

I suggest that this new social knowledge and methods, such as the texts that I’m clustering under the term “ethnography,” represent different stories, better stories, about human differences. Better stories, a concept extrapolated by cultural theorist Dian Georgis, are emotional resources for understanding our past, present, and future existences.[13] A “better” story, she suggests, helps us imagine what is possible. Better stories are queer forms of knowledge, in the sense of being characterized by ambivalence, ambiguity, paradox, and the destabilization of what we assume we know. As sociologist Kathy Davis argues, the term “better stories” does not imply moral superiority.[14] There are always better stories that can surprise, move, and open us to future possibilities.

Ethnographies, I argue, are better stories about difference. They are open-ended, rather than foreclosing curiosity. They capture complexity, messiness, affect, and contradictions in the myriad forms of difference in the social world. They generate more questions and even more stories. As we will see in the texts I have chosen, better stories are not perfect, nor do they need to be.

Finally, these chapters travel through deviant places. I argue that places, actual research-site locations, shaped the making of social knowledge and ethnographic stories. I locate the scholars examined here in their geographic location, sketching some of the intersections of place, research, and stories. Most of the sites of these classic texts have changed radically over time, some no longer exist, and some—like The Hobo—are multiple and transient. Yet even these changes tell a story. In the next chapter, I examine the analytic possibilities afforded by the study of research locations in the making of social knowledge.

Government professor Charles King tells a triumphalist tale about some of the figures who appear in my book, such as Franz Boas, Ruth Benedict, Margaret Mead, and Zora Neale Hurston (King largely overlooks the important sociological work during this period). King argues that this “circle of renegade anthropologists reinvented race, sex, and gender in the twentieth century.”[15] He claims we can thank Boas and his “contrarian researchers” for bringing about an outlook King calls “modern and open-minded.” It is a worldview, he suggests, that rejects racism as “morally bankrupt and self-evidently stupid,” and instead embraces social differences and diverse cultural expressions. It is an outlook, for example, that now makes it “unremarkable for a gay couple to kiss goodbye on a train platform.” In his telling, cultural anthropologists freed difference from cultural and political demonization.

But did they? My own story in this book is different. And darker. It complicates the idea of an arc of cultural progress. Major changes in culture, laws, and forms of knowledge over the last century are indisputable. But it would be a mistake to see those advances as settled. The landscape of difference, outsiders, and marginality is still hotly contested, not reinvented and resolved. I argue that the work of this loose cohort of early- to mid-twentieth-century social researchers, in particular sociologists, produced social knowledge about types of difference that were, and remain, at the center of the volatile battles that in the 1980s became known as the culture wars. They did not vanquish biological determinism, which we see achieving broad popularity again in the twenty-first century. Nor did they quell a bitter emotional politics over difference. It is possible, in fact, that this social science contributed to culture wars as a result of the heightened visibility it brought to modern differences. Finally, many of these scholars were stigmatized for studying stigmatized outsiders, and the field of deviance studies was itself beset by discrediting dynamics that undercut its legacy.

Caveats and guideposts are in order. Like all stories, this one is partial. I selected texts, authors, and topics in keeping with a certain methodological logic that would support a meaningful and diverse story about the social-knowledge production of difference. The texts I have chosen allow me to explore familiar, and less-familiar, categories and types of difference: race, gender, class, age, and sexualities; places of marginality and deviance; forms of transgression such as impersonal public sex, and choosing to live outside of conventional nuclear family structures.

The chapters tell stories over time as well as place. The early texts—The Hobo, The Taxi-Dance Hall, and the field research of Zora Neale Hurston—suggest an early ethnographic rupture of the determinist narratives of race science. They depict field researchers shaped by new social ideas about difference while also grappling, variously, with ambivalence, moralism, bias and stigma, and structural inequalities. Midbook we reach midcentury, and Erving Goffman’s canonical text, Asylums: Essays on the Condition of the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. The remaining chapters highlight the epistemic transformation in the study of social differences brought about by these midcentury sociologists and their students. Goffman, Laud Humphreys, and Sherri Cavan unapologetically featured mental patients, hippies, and men having impersonal public sex as savvy social actors fashioning their own normative communities. Old age and death weave through the conclusion, in anthropologist Barbara Myerhoff’s classic ethnography, Number Our Days. By this point, as aging was increasingly medicalized, and the sociology of deviance was suffering criticism from emergent disciplinary approaches to difference, Myerhoff’s portrait of the dailiness of immigrant Jews underscored that old age—itself a form of strangeness—was more cultural than biomedical, reinforcing the power of ethnographic rather than biomedical stories.

Most of the authors I examine in this book are sociologists. This is for reasons beyond my own disciplinary affiliation. The book tells US histories, and the cohort of early- to midcentury social scientists studying marginality and deviance in local neighborhoods were largely sociologists. As anthropologist Esther Newton told me, until the latter part of the century, there was pressure for anthropologists to work in foreign, seemingly exotic places: “They were all running off to New Guinea. That was the real anthropologist—with the helmet and the beard.”[16] The anthropologists I include here, Zora Neale Hurston, Barbara Myerhoff, and Esther Newton, felt compelled to explain why they were studying US localities (Erving Goffman crossed between the disciplines but is generally referred to as a sociologist). Not all the scholars I discuss would have described their work as ethnographic—the term was not widely used by early-century sociologists, for example. But the work I profile shares the methodological approaches of deep, extended cultural observation, along with “thick descriptions”[17] of, and a new epistemic approach to, different social worlds.

There are expansive literatures on all the different social types explored in these chapters, as well as numerous histories of the social sciences, sociology, the Chicago School, anthropology, and ethnography. My book does not aspire to fully incorporate or review that scholarship. Rather, I stick closely to my own stories, using these texts to show how certain early and midcentury social scientists, particularly sociologists, embraced themes of strangeness, marginality, and outsiders, and rewrote deviance. It is a less-told tale of how this strain of social science introduced new and different ways of thinking and feeling about human difference. While new social knowledge and ways of knowing about difference center this book, the chapters are not a linear movement through theory-building, nor a fine-grained exposition of theoretical debates across the decades. I’ve chosen texts that feature historically diverse outsiders—along with outsider institutions, buildings, scholars, businesses, and places—and that showcase the narrative possibilities of the broad ethnographic imagination in telling their stories. Cumulatively, the texts explore the worlds of marginal people in deviant places. Likewise, I keep my focus on the ethnographers and their texts, rather than giving equal time to the historical views of race science toward the marginalized people in these chapters. Readers can find those stories elsewhere.

A number of tensions, paradoxes, and discontinuities weave through this book. For example, the American paradox of cultural rejection and embrace of difference; the swagger and stigma of deviance; the exploitations and appreciations in the ethnographic gaze; the conflicts and conciliations generated by the cultural visibility of outsiders. There are the paradoxes of capitalism. As historian John D’Emilio has argued, the expansion of wage labor and capital profoundly transformed “the nuclear family, the ideology of family life, and the meaning of heterosexual relations.”[18] Capitalism, then, helped support the possibilities for new types of social difference, at the same time that outsider capitalism commodified, exoticized, and in some cases normalized difference. I have identified, rather than resolved, these paradoxes, which by their very definition are unresolvable.

I use the terms “ethnography” and “difference” in this book both broadly and narrowly, another paradox. For one, I use “ethnography” to refer to a social-science methodology of deep cultural observation, as I explain in the next chapter. As sociologists Patricia and Peter Adler note, the scholarship on ethnography has become “a huge industry,”[19] and I do not review that literature or generalize my claims to all ethnographies. Rather, I suggest an ethnographic potential. My ethnographic optimism is not a refutation of the many thoughtful criticisms of it, many of them from anthropologists. Some of these criticisms are exposed in these chapters, in particular certain early scholars’ connection to moralistic social reformers. However, I remain appreciative of ethnography’s history of, and possibilities for, producing the better stories that capture the pluralities and complexities of differences.

In addition, I use the term “ethnography” as shorthand for the fusion of method and epistemology. Since this book focuses on the epistemology of social difference, I use “ethnography” as an umbrella term to denote new ways of knowing, thinking, feeling, asking questions, and writing about outsiders, deviants, and difference. It is, to adapt Mills’s term, an ethnographic imagination. By this I mean an epistemic stance characterized by curiosity, not about the origins, treatment, and eradication of human variation, but about the cultures, worldviews, and ways of living of those who are different.[20] In other words, better and different stories about difference. I connect early explorations of outsiders, strangeness, and urban marginality (and in Hurston’s case, rural differences) to midcentury theoretical ruptures with biological determinist narratives of difference, culminating in a sociology of deviance. This shorthand departs from narrower, conventional definitions of ethnographic method, but makes it possible to write a manageable story.

Likewise, there are different ways of being different, of being marginal and outside. I use the term “difference” both broadly and specifically. Familiar forms of difference figure prominently in these chapters—the expected “menu,” such as race, class, and gender, as anthropologists Carol Greenhouse and Davydd Greenwood call these “official discourses of difference” operationalized by state bureaucracies.[21] We see how some early social scientists prefigured later critical-race scholars, feminist theorists, and queer-studies scholars who documented how allegedly essential categories such as race, gender, and sexuality are invented and reproduced through structural, cultural, and interactional dynamics. However, a central theme of this book is the emergence of new kinds of people in modernity—new social differences—and how some social scientists studied and ascribed meaning to these differences. Therefore, many of the marginal people who appear in these pages are those defying norms, such as living outside of nuclear families or following unconventional career trajectories. These chapters move through different forms of difference.

The title of this book—Marginal People in Deviant Places—employs the terms “marginal” and “deviant” in their critical, even oppositional, sociological spirit. Outsiders have gone by different names in different historical eras: degenerates, deviants, outcasts, misfits, reprobates. More specific pejoratives refer to race, mental status, gender, sexuality, and other variations. The vocabulary of difference has changed over time, and the stories in this book delineate some of those historical shifts. I use the language specific to each text and its historical period, and avoid the use of scare quotes and qualifiers, such as “alleged deviance.” Notably, the sociological term “deviance” is today often misread as negative and judgmental. However, sociologists flipped this vernacular meaning into a critique of how rule-makers create what we consider to be deviance. Deviants are, as sociologist Howard Becker put it in 1963, “sufficiently bizarre and unconventional for them to be labeled as outsiders by more conventional members of the community.”[22] This sociological reframing, universalizing, and respect for marginality, deviance, strangeness, outsiders, and difference is a central theme of this book.

Marginal People in Deviant Places tells a critical history of knowledge production and a social history of myriad American outsiders and their places. These chapters do not cumulatively represent a tidy, comprehensive story about social science, ethnography, or difference. Rather, they historicize an interruption of the dominant race-science stories of the era, and suggest the narrative power of ethnographic stories to confound essentialist categories and hierarchical meanings of difference. While I use the terms “marginal” and “deviant” to evoke this historical rupture, the possibility that they retain emotional traces of shame signifies that this rupture is partial and ongoing.

The stories, people, and places examined in this book show that we are not one, or even two Americas, but that there are potentially endless variations on how to be a person in the modern world. This multiplicity of American difference has been foundational to the country’s artistic creativity, economic vibrancy, technological innovation, and much more. Yet there is a shadow over these stories of marginal people in deviant places. In this book, we see social condemnation and political opposition to differences—and to the scholars who wrote about them. It is timely, then, to investigate our history of social-science knowledge production about difference, and how we know what we think we know about those who diverge from conventional norms. Dian Georgis argues that “we are not obligated to live by the stories that no longer help us live well.”[23] We can tell different stories about difference. Culture wars over issues such as race, immigration, gender, trans identities, and other variations, highlight how debates about social inclusion and social marginality, about normalcy and nonconformity, and about who matters in American democracy and culture are not in our historical past, they linger in our ongoing, unsettled present.

Methods, and Such

I, too, am a storyteller of outsiders, writing in a specific historical moment, with my own intellectual and political passions. Some of this book’s topics—hobos, taxi dancers, older Jewish immigrants, asylums—were new to me and exciting to explore. Yet I have been writing about these overarching themes—the history of knowledge production, marginality, stigma, social hierarchies, outsider scholarship, art, activism, and the commodification of difference—throughout my career. This mix of familiarity and unfamiliarity made it the perfect project. There was also a personal-political dimension. My own social locations, and activism, as an outsider made me a fellow traveler with the marginality, strangeness, and deviance I examine in this book.

I began this project in 2012, focused specifically on the midcentury sociology of deviance. Like so many books, it started out as one thing and ended up being, well, different. As the focus expanded to the sociological prehistory on difference—strangers and marginality—my time period moved earlier in the twentieth century to include two classic Chicago School texts (chapters 2 and 3). The digital format, available online at https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11519906, allowed me to veer toward subplots that enrich the main story, so I had the freedom to follow paths that were interesting and fun. I have told my own stories around and through these ethnographic stories. In the digital edition, the chapters have hyperlinks to stories connected to the main themes, including archival and interview material, as well as commentary by contemporary scholars working on these topics and in these places. Textual hyperlinks appear at the end of chapters in the print edition, but for the fully enhanced experience of the book, readers should consult the online edition.

I further expanded the book to examine ethnographic places after my visit to Laud Humphreys’s tearoom sites in St. Louis. There is a magical dimension to walking in the footsteps of a long-ago ethnographer of an iconic or favorite text. It is, perhaps, for social researchers, the equivalent of visiting battlefields. Fortunately, before the pandemic shut down travel, I was able to wander the research locations of all the ethnographic work in these chapters. In the case of Zora Neale Hurston, my Florida road trip took place during the week in mid-March, 2020, when the world began shutting down. I visited Hurston’s hometown, Eatonville, worked in her collected papers at the University of Florida, and then drove to Fort Pierce, where she died, all during the period when conservative radio hosts were decrying the novel coronavirus as a hoax. At other research sites, I took historical walking tours and architectural tours, combed historical museums, and explored streets and neighborhoods with knowledgeable colleagues. I went to the annual Hobo Convention in Britt, Iowa. These explorations offered glimpses of sites as they had existed during the earlier moment of ethnographic study, and of how they have changed. They also yielded insight into how places might matter in research (see chapter 1). During these trips, I took many of the photographs in this book.

This critical history is based on qualitative interviews, archival research, and primary sources. I conducted approximately fifty interviews in the United States, the UK, and Israel with pioneering sociologists, scholar-activists, public intellectuals, and artists. Regarding the criteria for my interview choices, I chose those who (1) had done pioneering research in the sociology of deviance; (2) were familiar with the field during the time period under study; or (3) were public intellectuals and activists with connections to disciplinary debates and public conversations about difference and deviance. I conducted archival research at several collections: the University of Chicago, the London School of Economics, Northeastern University, the University of Southern California, the New York City Public Library, the University of Florida, and One National Gay & Lesbian Archives. The interview material largely shows up in the later chapters, since the authors of key texts on those chapters’ topics, or some of their contemporaries, were still alive. The early chapters are based on the original texts and archival material, supported by video interviews with scholars.

A word about the digital platform. This project essentially required that I visually curate my own ideas, an endeavor that social scientists are not typically trained to do. In choosing the photographs and designing the book map, I had to shift from a textual to a visual orientation for presenting ideas. This process changed me, in a good way, as a writer, and also a reader. There were quirks and nuances. For one thing, copyright restrictions limited my choices. In addition, the pandemic travel shutdown prevented my final set of research trips for gathering historical and contemporary images, and, importantly, for shooting video interviews in person and on-site. Zoom allowed me to keep interviewing, but it wasn’t the same. While the loss during lockdown of UMass digital support for editing lends these videos more of a DIY quality than I had originally anticipated, they strike me as sort of heroic, given all the constraints. Video editing is also a form of knowledge production and revision. Most videos were only tweaked, but stories in a few of them were shortened to fit constraints on time and file size. In those cases, I made choices based on which stories most closely hewed to the book’s key themes.

The interviewing and archival research largely took place during what now, in retrospect, seem like the relatively calm Obama years. The project felt lighthearted at that point, at least in my imagination. Much of the writing, however, took place during the four years of the Trump administration. Even prior to the 2016 election, Donald Trump had stoked anger and hatred toward many types of social differences—particularly immigrants, African Americans, women, and trans people—as a way to mobilize his base. At the same time, Trump, a White, male, elite billionaire, touted his supposed outsider status. Cultural polarization, even violence, related to social differences spiked, while the cultural meanings of “outsider” were confounded. Soon into his administration, historians had warned that the United States was drifting toward fascist politics, what philosopher Jason Stanley calls “a permanent temptation,”[24] with its intensification of hierarchical discourses of “us versus them.”[25] This shifting context underscored the importance of research and stories about social differences. There are many themes in this book, yet the central one is a story about scientific knowledge production that either supports or challenges us-them thinking.

One: Introduction

“Must you conform?” is the question that haunts all men living in this time of crisis and decision.[26]

Robert Lindner

In 1956, psychoanalyst Robert Lindner, author of the 1944 classic Rebel Without a Cause, published his quirky text, Must You Conform? suggesting that the answer could be, no, you need not. Lindner’s question, provocative in a climate of racial intolerance and cultural anxieties about nonconformity, also hinted at a zeitgeist of modern outsiders. New types of social differences were being brought into being by a pivotal half-century of unprecedented modern change. Some of these key developments of modernity included urbanization, rapid scientific and technological advances, social fragmentation, the rise of liberal individualism, and the burgeoning of industrial capitalism. These fostered new opportunities to be an outsider, while outsiders themselves became more socially visible. Social differences—and stories about them—proliferated in these early decades, continuing throughout the twentieth century.

American Studies scholar Anna Creadick argues that the idea of “normality” gained cultural currency in the post–World War II years, 1943–1963.[27] Scientific medicine and psychiatry produced discourses, circulated through popular media, promoting the widespread embrace of normality. Yet much earlier, sociologists were troubled by, and at the same time troubled, questions of difference, conformity, and outsiders. In 1927, University of Chicago sociologist Ernest Burgess scrawled at the top of his Social Pathology course notes—“What is the normal?”[28] A modern social science of difference began viewing “social pathology,” which would later become “deviance,” as an often-creative adaptation to modern urban life. By midcentury, sociologist Edwin Lemert argued for the abandonment of the “archaic and medicinal” idea that human beings could be classified into categories of normalcy and deviance.[29] It was a radical articulation of ideas that would be dubbed the sociology of deviance, or deviance studies. Easy assumptions about deviance and pathology, the normal and abnormal, conformity and deviance, began to crumble.

Fast forward to 1990. Pioneering literary and queer theorist Eve Sedgwick famously claimed, “People are different from each other. It is astonishing how few respectable conceptual tools we have for dealing with this self-evident fact.”[30] In fact, we did have the cultural tools, with a new language of difference. They were, rather, unknown, forgotten, or ignored, even by humanities scholars sympathetic to outsiders. Time passed, and innovative ideas had faded or were lost in disciplinary silos. However, this book argues that in the early to mid-twentieth century, certain social scientists developed new conceptual and methodological tools for radical exploration of differences.

The intellectual and social landscape of difference changed throughout the twentieth century. This chapter introduces that story. The first two sections sketch a historical background useful for thinking through the ethnographic ruptures to race science. I examine two different approaches to studying, theorizing, and storytelling about human variation of individuals and social groups. Race science saw variations as largely biological in origin, manifest in inferior physiological traits such as cranial size, bone density, skin color, ear shape, and the like. They framed social identities, such as race and gender, as well as nonconforming behaviors such as criminality and sexual difference, as embodied and fixed. By contrast, social scientists rewrote difference, depicting deviant worlds as ordinary. They developed research methods and introduced conceptual frameworks that produced different stories in which outsiders and strangers were constructed by, and navigated their way through, particular historical, social, economic, and political circumstances. Ethnographers’ thick descriptions represented individuals as constructing meaning and living within coherent cultural systems and worldviews. These studies of the rich social worlds of others enabled later scholars to argue that difference is socially constructed, its social meanings invented.

The final section of this introduction examines the pivotal role of ethnographic places in storytelling about difference. Ethnographers often invented pseudonyms for the villages, hospitals, bars, nudist colonies, and other sites they studied, omitting location entirely or burying the specific place in a footnote or preface. Yet this book argues that ethnographic locations, spaces, and places represent a significant aspect of how ethnographic knowledge production ruptured race science narratives.

Ethnographic stories carry traces of their locations. Extending geographer David Livingstone’s call for a “geography of science,”[31] I suggest that knowledge of research places helps us differently understand these social science texts, the scholars themselves, the processes of social research, and the interweaving of research setting and the makings of social knowledge. At the end of this introduction, I suggest numerous ways that ethnographic places matter in social research and analysis. Overall, in this introduction I do not undertake the impossible task of a thorough literature review of modernity, scientific racism, the histories of ethnography and deviance studies, or the sociology of place.

Modern Social Differences and Race Science

Cultural anxieties about difference, a fear of the “abnormal,” as philosopher Michel Foucault noted, “haunts the end of the nineteenth century.”[32] The “monsters” Foucault discussed from this period were figures such as the masturbator and the incorrigible, yet this time saw a turbulent mix of racial, ethnic, gender, and other differences. In the United States in the post-Reconstruction era, racial hatred fueled segregationist laws and escalating violence against African Americans. Immigrants were the target of increasingly exclusionary policies. Women were still denied suffrage. Social transgression was punished by law or community sanction. Yet change, in certain respects, was in the air. Social researchers worked against the backdrop of two countervailing dynamics: social changes that enabled new ways of living and new types of differences, and the dominant discourse of scientific racism dedicated to explaining and eliminating them.

Different Differences

Modern life brought changes that allowed, forced, or encouraged new forms of difference. Steven Smith refers to modernity as the site of a “unique human being”—the bourgeois.[33] Yet modernity did not just produce the bourgeoisie, it opened up space for social transgressions of many kinds, both cultural and individual, whether by choice or circumstance. The new mobility enabled by transportation technologies introduced strangers and difference into cities and previously homogeneous villages. A wide range of nonconforming social types achieved new visibility on the streets. Later communication technologies such as radio and television, along with changes in print culture, brought strange new characters and different subcultures into mainstream homes.

These material changes helped produce a “social imaginary” of modernity—its collective background or cultural understanding that enables social life.[34] Cultural sensibilities—social imaginaries—of strangeness, ambiguity, and marginality resonated widely, as bohemia emerged in US cities early in the century, and dissident types burgeoned. These deviant types intrigued new social researchers, such as those discussed in this book, whose scholarship was surely a force in generating what historian Christine Stansell describes as “a milieu that brought outsiders and their energies into the very heart of the American intelligentsia.”[35] By the mid-twentieth century, modern social changes enabled Robert Lindner and others to posit nonconformity as a decision, a choice. In time, strangeness would be embraced by some, for example hippies, while social marginality became a creative choice for others.

Capitalism played its part in this story. Economic and social changes associated with capitalism supported possibilities for new types of social difference. Individuals moved from the constraints of small village life, with its religious and familial regulations, into urban ways of living and working. This might mean living solo or in an unconventional arrangement. As historian John D’Emilio has argued, the expansion of wage labor and capital profoundly transformed “the nuclear family, the ideology of family life, and the meaning of heterosexual relations.”[36] Transforming, too, were the meanings of gender, work, leisure, marriage, public places, and much more.

Capitalism celebrated difference, yet flattened it. As historian Thomas Frank argues, “liberation and continual transgression” were foundational to consumer capitalism. Unfettered desire fueled consumption. By the sixties, he notes, “hip became central to the way American capitalism understood itself and explained itself to the public.”[37] Rebellion became an advertising trope. However, capitalism’s role goes beyond the marketing of “hip.” Broad domains of social marginality, strangeness, and difference became commodities to be bought and sold. As new forms of difference and strangeness became possible and visible, capitalism would become adept at recognizing, packaging, and marketing them.

The dynamics of what I call “outsider capitalism” emerged. In being mass marketed, some outsiders and ways of being an outsider became more visible, with paradoxical effects. Outsider capitalism could blunt the edges of difference. Widely available for consumption, difference easily morphed into conformity. Still, the packing and selling of outsider difference required making it attractive, a move arguably preferable to knowledge practices that fostered social hostility.

This necessarily brief sketch argues that early- and mid-twentieth-century dynamics fostered new possibilities to be different and new kinds of people. I extend philosopher Ian Hacking’s useful concept, “making up people.”[38] Hacking claims that throughout the twentieth century, scientific and medical expertise, including psychiatry and psychology, generated new, typically biomedical, frameworks and languages for people to understand themselves, their behavior, and their social interactions. Hacking identifies what he calls “engines of discovery,” such as counting, scientific classification, and the generation of expert knowledge, which produced new identities across a wide spectrum of behaviors. Sociologists call this process the medicalization of everyday life.[39] I argue throughout these chapters that it was not just medicine and psychiatry that produced new types of people, with new languages, social networks, and ways of being a person. Other engines of social change were also crucial in making up people, including modernity, capitalism, political activism, cultural production, and ethnographic inquiry and storytelling. However, Hacking’s focus on biomedicine and the psychiatric disciplines, and this book’s historical backdrop of scientific racism, underscores these factors’ long-standing discursive power in defining and regulating social difference.

Essentialized Differences

The social complexities of modernity generated a reliance on expertise. A central project of science has been to produce stories about difference, entailing efforts to explain and classify human variation. Spurred by late-nineteenth-century concerns about recent immigrants, African Americans, and native-born Whites,[40] race had become a central classification system.[41] Scientific racism became one of the dominant institutions producing social knowledge—particular narratives and stories—about human variations. Race occupied the center of intellectual attention to difference. Scientific racism, which contained several ideological and theoretical strands regarding heredity and biology, posited that innate biological differences accounted for essential hierarchies of superiority and inferiority, conformity and deviance.