Agnes Callard

The Virtuous Spiral

Aristotle’s Theory of Habituation

2. Virtues and parts of the soul

3. Habituation as virtue acquisition

4.1 Knowledge as a back door to virtue?

4.1.1 Knowledge does not give rise to virtuous dispositions

4.1.2 Knowledge does not give rise to virtuous actions

4.2 Partial virtue in Metaphysics Theta 8

1. Introduction

Aristotle’s ethics is an ethics of virtue activation: a happy life calls for the exercise of the virtues of justice, courage, moderation, and the rest. But how do people become virtuous? This is a fundamental question for Aristotelian moral psychology, since we need to answer it in order to know how ethics can be realized in creatures like us: non-eternal organisms who exist by changing over time. Is virtue ‘natural’ to us—is it somehow, innate, waiting to be expressed—or is it the product of ‘nurture’—impressed upon us by our familial and social environment?

Aristotle’s answer is: neither. We acquire virtue by habituation. Aristotle grants that we could not acquire virtue without the contributions that both nature and nurture make to our efforts, but his understanding of the fundamental mechanism of virtue acquisition falls on neither side of that divide. Habituation is not the emergence of innate virtue nor the transfer of virtue from what has it, to what doesn’t. Rather, habituation is self-transformation, the acquisition of a disposition—such as the disposition to act virtuously—by way of exercising that very disposition—acting virtuously.

There is, however, a difficulty as to how such a process is possible, given that one cannot exercise a disposition one lacks. If virtue is both required for, and generated by, virtuous action, habituation becomes an incoherent process, a conceptual analog of M. C. Escher’s drawings of impossible cubes and staircases. Call this problem ‘the habituation circle’.

This chapter draws on Aristotle’s metaphysics of change and his analysis of the division in the soul to demystify the workings of habituation. Aristotle thinks that ethical change, like change in general, happens part by part. His account of habituation relies on the intelligibility of possessing partial virtue, and of performing an action in a partially virtuous manner. Though virtue both produces and is produced by virtuous activity, the two instances of ‘virtuous activity’ are not the same: the performance of a somewhat virtuous action makes a person somewhat more virtuous, and this in turn allows her to act somewhat more virtuously, and so on. The processes that correspond to the two ‘halves’ of the circle—virtue giving rise to virtuous activity, and virtuous activity giving rise to virtue—each operate on one another’s output in such a way as to move the agent towards more virtue, and more virtuous activity.

This feedback loop resembles a closed circle less than a spiral opening outwards, growing in size. Such growth calls for the two parts of the process—action producing virtue, and virtue producing action—to be separate occurrences. I show that Aristotle’s division of the soul into an affective and an intellectual part allows him to describe these as two distinct stages. When I make myself virtuous, I do so because my intellectual part can act on my affective part, regulating my feelings; and, in turn, my affective part can act on my intellectual part, making me receptive to knowledge.

2. Virtues and parts of the soul

In I.13, Aristotle divides the soul into an affective and an intellectual part.[1] In the affective part are contained desires, passions, pleasures, and pains: the affective part of the soul is that in virtue of which we are sensitive and feeling creatures. The intellectual part, by contrast, is responsible for the activities of thought and reasoning, both theoretical and practical.

The ethical virtues (courage, justice, moderation, etc.) are organized and perfected conditions of the affective part of the soul. These conditions amount to dispositions to act and feel in the right way.

But what is a disposition? A disposition is an extra level of organization to which something is subject when its nature underdetermines how it will respond in a set of situations. To have the relevant disposition is to have acquired the organization necessary for responding well, as opposed to badly, in the specified set of situations.

When, for instance, one’s soul is in a good (i.e. courageous) condition with respect to fear and boldness, one will feel and choose as one ought in circumstances that involve danger. Likewise, when one’s soul is in a good (i.e. moderate) condition in respect of appetitive desire, one will make the right choices in respect of food, or sex, or physical comfort. A virtuous person will be neither over-indulgent nor abstemious in a way that interferes with health or pleasure. In general, the virtuous person is the one who feels, desires, and fears in accordance with what is in fact good or bad.

If we turn our attention to the intellectual part of the soul, we see that it too has an organized or perfected condition. When someone is such that she reasons well theoretically—which is to say, about what is eternal and cannot be otherwise—then she has the virtue of sophia (theoretical wisdom). When she is disposed to reason well practically—which is to say, about what it is up to her to determine—then she has the virtue of phronēsis, practical wisdom. In general, we can say that a person has intellectual virtue when her thinking guides her in the right direction, either in theorizing—towards knowledge—or in acting—towards the good.

The distinction between ethical and intellectual virtue is an important one for discussions of virtue acquisition, since the two forms of virtue are acquired in different ways. Ethical virtue is acquired by a process of habituation (ethismos), whereas intellectual virtue is acquired by teaching (II.2, 1103a14–18). Aristotle’s discussion of virtue acquisition in the Nicomachean Ethics concentrates on ethical virtue specifically, and thus on the process of habituation. In fact, he typically uses the word ‘virtue’ (aretē) as a shorthand to refer to ethical virtue specifically, a practice that I, like most commentators, will henceforth follow. (Though in those places where context calls for disambiguation I will introduce the modifiers ‘ethical’ and ‘intellectual’.)

Nonetheless, it will not be possible to set aside intellectual virtue or its acquisition entirely. This is, first, because the two kinds of virtue-acquisition process often get conflated: some of Aristotle’s contemporaries were inclined—perhaps in part due to the influence of Socrates—to make the mistake of understanding the process of habituation into virtue as purely a matter of the intellectual acquisition of knowledge about how to act. Aristotle is interested in diagnosing and correcting this mistake, and thus the contrast between intellectual and ethical virtue hangs in the background of his account of habituation. More positively, he believes that education of the affective part of the soul is not independent of education of the intellectual part of the soul. This dependence is not surprising, given his thesis of the unity of the virtues (VI.12–13): just as one cannot have practical wisdom in the intellectual part without ethical virtue in the affective part (or vice versa), so too the process of acquiring the one is not fully independent of the process of acquiring the other.

3. Habituation as virtue acquisition

Aristotle’s view is that we become just, moderate, and courageous people by performing just, moderate, and courageous actions. Habituation is the process of acquiring the disposition (i.e. the virtue of justice, moderation, or courage) by performing the corresponding (just, moderate, or courageous) action. Before examining the workings of the process of habituation in further detail, it is worth situating this conception of habituation in Aristotle’s larger theory of virtue. Virtue, according to Aristotle, is something praiseworthy, and it does not arise by nature or by craft; nor is being virtuous a merely accidental property of a human being.

3.1 Not by nature

Let me begin by explaining why Aristotle thinks nothing acquired by habituation can be natural.

Aristotle’s metaphysical worldview divides the world into those things that do and those that don’t have an internal source of change and rest. His word for such a source of change is ‘nature’; ‘natural things’ are things that are such as to be the sources or causes of their own changes: plants, animals, their parts, and the simple bodies (earth, air, fire, and water). A tool or house, by contrast, is dependent for its existence and continued maintenance on external source of change and rest, namely the craftsman or the caretaker (Physics II.1). Natural things use and sustain themselves, and these processes are governed by the form or (in the case of living things) the soul of the thing in question. A tiger’s activities are governed by its form (i.e. soul), and it exists for the sake of that form. It is self-regulating. For instance, the final dimension and shape that limits its growth can be traced to the form in it (De Anima II.1–4, On Generation and Corruption I.5).

Aristotle denies that virtue is natural. Virtue arises by habituation, and natural things cannot be habituated to act contrary to their nature:

This makes it quite clear that none of the virtues of character comes about in us by nature; for no natural way of being is changed through habituation, as for example the stone which by nature moves downwards will not be habituated into moving upwards, even if someone tries to make it so by throwing it upwards ten thousand times, nor will fire move downwards, nor will anything else that is by nature one way be habituated into behaving in another. (II.1, 1103a18–23)

If it were in our nature to be good (or neither good nor bad), then habituation could not make us bad, and if it was in our nature to be bad (or neither good nor bad), then habituation could not make us good. Given that we can be changed by habituation, the virtues cannot be ours by nature.[2]

3.2 Not an accidental change

Consider the relatively superficial kind of changes that something undergoes when it gets moved from one place to another, or dipped in paint. Accidental changes of this kind come at a tangent to the essence of the thing in question: something can take on and lose accidental properties without changing in any respect that concerns what it is. Could virtue be an accidental property? In Physics VII.3, Aristotle answers this question for one specific kind of accidental change—alterations, which are changes in the sensible properties of something: ‘dispositions, whether of the body or of the soul, are not alterations. For some [dispositions] are virtues and others are defects, and neither virtue nor defect is an alteration: virtue is a perfection’ (246a10–13). His reasoning can be generalized to all accidental changes, however, since no accidental change can be a perfection (or defect) of the thing in question—perfection must speak to the being of the thing in question:

So just as when speaking of a house we do not call its arrival at perfection an alteration (for it would be absurd to suppose that the coping or the tiling is an alteration or that in receiving its coping or its tiling a house is altered and not perfected), the same also holds good in the case of virtues and defects and of the things that possess or acquire them; for virtues are perfections and defects are departures: consequently they are not alterations. (Phys. 7.3, 246a17–246b3)

The virtues are perfections of the thing whose virtues they are: a virtue is what it is for the thing to be a good exemplar of some particular kind. For this reason, a perfection stands in a close relation to the process of generation: Aristotle says that ‘a circle is perfect when it is really a circle and when it is best’ (Phys. 7.3, 246a15–16). Perfection completes the process of generation, just as the coping or tiling completes the house. In being perfected, the thing comes to fully inhabit a particular way of being. And so the question, for a human being, is: which way of being does virtue perfect?

There are two possibilities. The first is that, despite not being due to nature, virtue nonetheless perfects nature. The second is that it perfects some non-natural way of being. This second option amounts, I will argue, a picture of virtue acquisition as virtue imposition, by society, upon the individual.

3.3 Non-artefactual

An artefact does not have its own nature. Its size, shape, and other properties are determined by the demands of its maker, and not, for example, by that of which it is made. A wooden bed is not, simply due to facts about what wood is like, a suitable place for a nap. It is suitable for a nap because someone has shaped it to be so. The maker makes the artwork by having, in his soul, the form that dictates how the artefact should be. He then imposes this form on some bit of matter whose nature was not such as to have this form. Aristotle says that once some wood has been made into a bed, it is no longer ‘wood’ but a ‘wooden’ something. The wood and its nature have been tamed and restrained by craft, and so ‘wood’ no longer counts as what it is to be the thing in question. Wood is demoted to the metaphysical status of matter. The thing is now an artefact—a bed—rather than a natural thing—some wood.[3]

If virtue acquisition happened in an analogous way, a person’s natural passions would be the product of the institutions, laws, and individuals making up her society. Just as the structure and function of the wooden bed are determined not by anything about wood but by the form in the craftsman’s soul, so too someone’s desires, fears, and emotions would be determined by what a community needs her to feel and how it needs her to act. On this artefactual picture, virtue arises contrary to nature, in that the new form (e.g. chair), replaces the form that was there before (e.g. wooden). To the extent that the chair still behaves like wood—e.g. sprouts wood if you plant it (Physics II.1, 193b7–13)—this is either accidental or contrary to its being a chair.

Aristotle rejects this artefactual picture of virtue acquisition. He denies that virtue acquisition works against the nature of the thing: ‘The virtues develop in us neither by nature nor contrary to nature, but because we are naturally able to receive them and are brought to completion by means of habituation.’ (II.1, 1103a23–6) It is not in the nature of wood to be braced and joined so as to support a sleeper. When the source of change and rest is external to something, Aristotle says that it is acted upon by a violent external force.[4] The wood is not ‘doing’ anything in becoming shaped into a chair. Its nature—which is what regulates all its doings—is being subordinated by the agency of the craftsman (and his tools). Habituation is to be contrasted with such processes, since it occurs by way of the actions of the thing being habituated. Aristotle thinks that, though virtue does not come about by nature, it is also does not come about in a way that is contrary to nature.

3.4 A source of praise

Why does Aristotle think that virtue is acquired through acting, rather than being acted upon? One possibility is that he took this as an observed fact about his own society. Another possibility is that this is a conclusion of what he took to be the most fundamental fact about virtue and vice: that they are sources of praise and blame. Aristotle’s methodology throughout the early books of the Nicomachean Ethics proceeds by operationalizing this feature of virtue: when he wants to make an argument as to what some virtue entails, he uses the fact that we praise or blame people who act in certain ways as the main constraint on the construction of the theory of that virtue. (For a general statement of the point, see I.12, 1101b13–14, II.5, 1105b30.) The intuitions with which he theorizes about courage and moderation presuppose that we see the courageous or moderate agent, rather than her parents or her society, as the proper target of praise—and likewise, that we see the cowardly or rash or immoderate agent as the proper target of blame.

Aristotle may have reasoned that if my excellence were something that someone did to me—a product of being shaped or inculcated or indoctrinated by the forces external to me—it would not be a source of praise. The passive recipient of virtue is not praiseworthy for having it, since it can be traced to another source. On the habituation theory, the mechanism of virtue acquisition is (the action of) the person being habituated. A person becomes virtuous not by having anything done to her, but rather by doing things—specifically, by performing virtuous actions. The virtue she acquires can, then, be traced to herself. I find it plausible that the demand to underwrite praiseworthiness is what led Aristotle to reject the artefactual picture in favour of one on which virtue is acquired by habituation.

It is worth emphasizing, however, that the agency manifested in virtue acquisition has a characteristic dependence on outside assistance. For example, in NE II.4 Aristotle explains that one way to do something you do not know how to do is to act under the direction of another. Aristotle does not believe that habituation would be possible, absent a framework of parents, teachers (and, most importantly) laws (see NE X.9)—for these give the agent direction in acting as she does not yet know how to act. Likewise, there are somatic or constitutional facts that have a role to play in one’s success. It follows that Aristotle’s ethical framework requires us to invoke the distinction between doing something with (natural and social) help and having something done to you.

The fact that habituation requires help has implications when it comes to moral responsibility for the failure to acquire virtue. Aristotle doesn’t make this point explicitly—he is less interested in questions of what mitigates responsibility in the failure case than in questions of what underwrites responsibility for the success case—but we can invoke his distinction between mere animalistic ‘brutishness’ and ethically blameworthy ‘vice’ in NE VII.5 to mark the relevant conceptual space. If someone’s natural or social environment is hostile enough to preclude virtue acquisition, then Aristotle says the resultant condition is not vice but rather something like brutishness. And while brutishness is in many ways analogous to vice—both are bad—this wider use of ‘bad’ does not license blame (1148b5–6).

When one’s failure to acquire virtue is due to the absence of the (natural or social) assistance, one is not morally responsible for this failure, and that is why we do not call these cases of true ‘vice.’

3.5 Habituation: summary

Thus, Aristotle’s account of habituation is an account of a process that is not natural, accidental, or artefactual:

Again, in the case of those things that accrue to us by nature we poses the capacities for them first, and display them in actuality later (something that is evident in the case of the senses: we did not acquire our senses as a result of repeated acts of seeing, or repeated acts of hearing but rather the other way round—we used them because we had them, rather than acquiring them because we used them); whereas we acquire the excellences through having first engaged in the activities, as is also the case with various sorts of expert knowledge—for the things we have to learn before we can do, we learn by doing.[5] For example people become builders by building and cithara-players by playing the cithara; so too, then, we become just by doing just things, moderate by doing moderate things, courageous by doing courageous things. (II.1, 1103a26–1103b2)

Aristotelian habituation invokes the category of things we learn to do and learn by doing—dispositions. This category, first, rejects accidentality by invoking perfection and, second, creates room between the idea of natural self-perfection and the idea of external perfection. Acquisition by exercise sets the acquisition of a disposition apart from both natural and artefactual changes. When a thing’s perfection is the product of its nature—such as with seeing or hearing—it acquires the potentiality[6] before exercising it. The same is true (though Aristotle doesn’t make the point here) of a craft object: the craftsman makes the chair able to be used for sitting, and it has this potentiality before it is actually used for sitting. We do not create chairs by sitting on them, any more than we create the power of sight by seeing. But we do create the power to play the cithara or the power of moderation by playing the cithara and being moderate. The power is ours and not to be attributed to any external source of change—we created it, by doing what we did—but the power is not natural, both because we had to create it, and because we required assistance to do so.

4. The habituation circle

The various distinctive features of virtue turn out to call for the idea of acquiring a power by exercising it. But this is a problematic idea, and Aristotle devotes a chapter of the Nicomachean Ethics—II.4—to the problem:

But someone might raise a problem about how we can say that, to become just, people need to do what is just, and to do what is moderate in order to become moderate; for if they are doing what is just and moderate, they are already just and moderate, in the same way in which, if people are behaving literately and musically, they are already expert at reading and writing and in music. (1105a17–21)

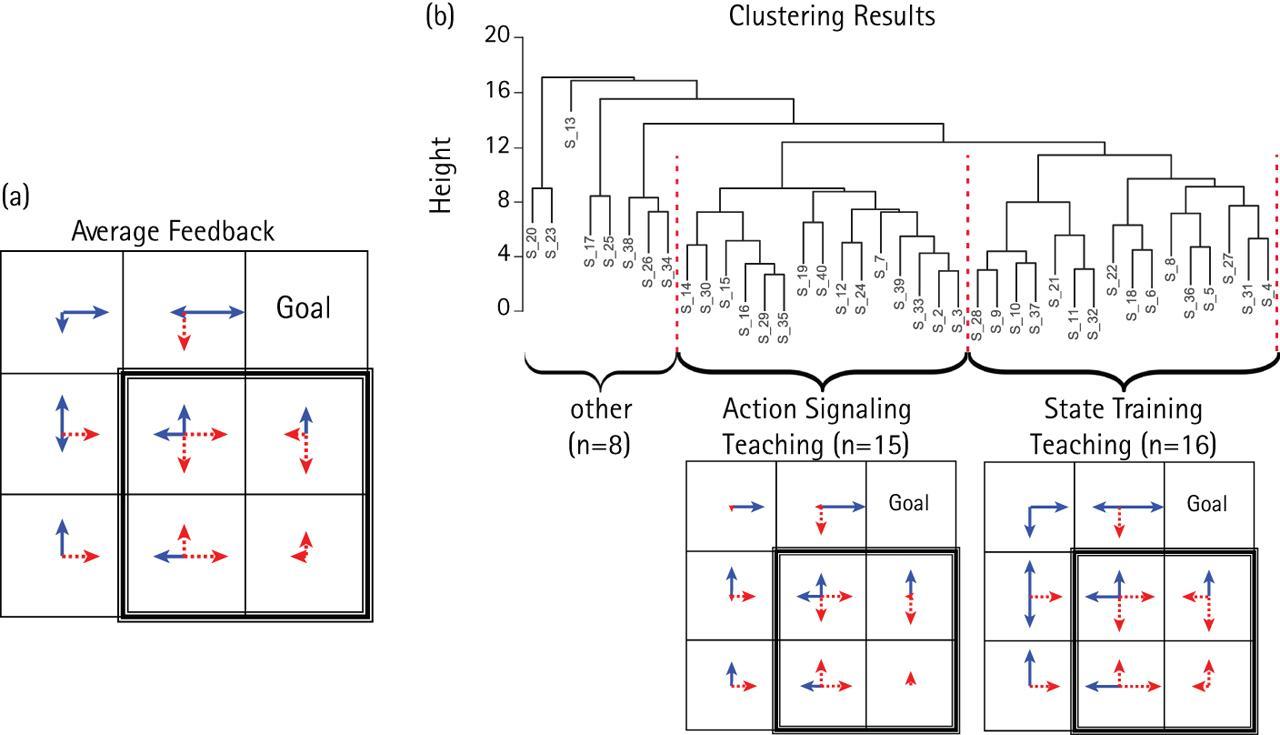

This is what I have called the habituation circle (Fig. 3.1): in habituation, virtuous actions are generated from virtue, but virtue is also generated from virtuous actions. The circle has two parts, the Disposition from Action Principle and the Action from Disposition principle.

The Disposition-from-Action Principle (DFA) says that people become just and moderate by doing just and moderate actions. The Action from Disposition Principle (AFD) says that just and moderate actions activate, and therefore presuppose the existence of, a person’s justice and moderation.

4.1 Knowledge as a back door to virtue?

This circular structure seems to make virtue acquisition impossible—unless perhaps there is an opening somewhere in the ‘circle’. If virtuous dispositions were not the only place from which virtuous actions could come, or vice versa, then we would have an easier time understanding how the process gets going. Is there another source for either one? Aristotle addresses himself to one such contender, knowledge. Aristotle sees intellectualism—the view that moral knowledge is all that is necessary for goodness—as a bad way of breaking into the circle; he argues both against the claim that virtuous dispositions come from knowledge (about how to be) and the claim that virtuous actions come from knowledge (about how to act).

4.1.1 Knowledge does not give rise to virtuous dispositions

Aristotle supports the claim that virtue must come from virtuous activity (and not knowledge) by denying that philosophizing can, independently of ethical habituation, give rise to virtue:

So it is appropriate to say that the just person comes about from doing what is just, and the moderate person from doing what is moderate; whereas from not doing these things no one will have excellence in the future either. But most people fail to do these things, and by taking refuge in talk they think that they are philosophizing, and that they will become excellent this way, so behaving rather like sick people, when they listen carefully to their doctors but then fail to do anything of what is prescribed for them. Well, just as the latter, for their part, won’t be in good bodily condition if they look after themselves, like that, neither will the former have their souls in a good condition if they philosophize like that. (II.4, 1105b9–18)

Aristotle is describing people who make the mistake of thinking they are going to be made good merely by acquiring knowledge. His claim is that it is not knowledge that leads the unhabituated to virtue of soul but rather action, just as it is not knowledge that leads to ‘virtue’ of body—health—but the action of following through on medical advice. The analogy with health might strike some as tendentious—it is clear that knowledge cannot, in and of itself, heal physical problems; it is perhaps less obvious that knowledge cannot, in and of itself, heal the soul.

It is important to understand this claim in the context of Aristotle’s divided psychology: improvements in the intellectual part of the soul no more immediately translate into improvements in the affective part of the soul than they do to the body. Aristotle notes in I.13 that the disconnect between the mind and the body is obvious—we can see it in the case of paralysed limbs—whereas in the soul the ‘disconnect’ between affective and intellectual is not as obvious but nonetheless equally real: ‘The difference is that in the case of the body we actually see the part that is moving wrongly, which we do not in the case of the soul. But perhaps we should not be any less inclined to think that in the soul, too, there is something besides reason, opposing and going against it’ (I.13, 1102b21–5).

Knowledge cannot heal your flu; so too it cannot heal your cowardice. This should not be seen as an argument by bad analogy, but as a reminder of the distinction articulated in I.13: the evident division between body and knowledge is meant to call to mind the less evident division between the knowledge in the intellectual part of the soul and ethical virtue in the affective part.

4.1.2 Knowledge does not give rise to virtuous actions

Aristotle inveighs against those who think knowledge will yield right action:

This is why the young are not an appropriate audience for the political expert; for they are inexperienced in the actions that constitute life, and what is said will start from these and will be about these. What is more, because they have a tendency to be led by the emotions, it will be without point or use for them to listen, since the end is not knowing things but doing them. Nor does it make any difference whether a person is young in years or immature in character, for the deficiency is not a matter of time, but the result of living by emotion and going after things in that way. For having knowledge turns out to be without benefit to such people, as it is to those who lack self-control; whereas for those who arrange their desires, and act, in accordance with reason, it will be of great use to know about these things. (I.3, 1095a2–16)

In this passage, Aristotle criticizes those who believe that right action will come to immature persons from the acquisition of knowledge—instead, he says, they will be like akratics, namely, people who cannot enact the knowledge that they have. Elsewhere he says that an akratic is like a city that has good laws but fails to enforce them (VII.10, 1152a20). Knowledge is not useful to a person for whom the appetitive part of the soul is in disarray. Rather, what is crucial both for right action and for the profitability of knowledge is that the person have a certain character, namely of the sort where their desires are made to accord with reason. Good actions cannot spring directly from knowledge, absent virtue.

Aristotle denies that knowledge represents a way of getting virtuous dispositions without virtuous actions, or vice versa. For it is the fact that someone (already) has virtue and (already) acts virtuously that allows any knowledge he acquires to be of benefit to him. Not only is knowledge no solution to the habituation circle, but it is, in fact, infected by the problem. Practical knowledge may be acquired by teaching but is nonetheless dependent on the success of habituation. This is because moral knowledge only gets a grip on us to the extent that it speaks the language of our motives and passions. If we preach to the unhabituated, our moral lessons are fated to fall on deaf ears. Thus, in order to be teachable, we require ethical virtue. In this way the problem of the acquisition of ethical virtue is also a problem for the acquisition of the intellectual virtue of wisdom (phronēsis).

4.2 Partial virtue in Metaphysics Theta 8

Aristotle’s answer to how habituation works, in light of the circle, is that one can act from partial virtue and one can perform actions that are partially virtuous. Virtue and virtuous activity come from one another because each can arise in an imperfect or incomplete form. Aristotle offers this answer in two places: the first is a chapter we have already sampled, Nicomachean Ethics II.4, and the second is Metaphysics Theta (θ) 8, in which he discusses the acquisition of a disposition in relation to the distinction between potentiality and actuality[7]. The two accounts are compatible, though they have different emphases. The NE II.4 discussion is focused on the explanatory force of the fact that we can perform actions that are virtuous, but not paradigmatically so; by contrast, in θ8 Aristotle’s solution to the same puzzle stresses the fact that virtue can exist in someone in an incomplete condition. Let me begin with the latter passage:

This is why it is thought impossible to be a builder if one has built nothing or a lyre player if one has never played the lyre; for he who learns to play the lyre learns to play it by playing it, and all other learners do similarly. And thence arose the sophistical quibble, that one who does not possess a science will be doing that which is the object of the science; for he who is learning it does not possess it. But since, of that which is coming to be, some part must have come to be, and, of that which, in general, is changing, some part must have changed (this is shown in the treatise on movement), the learner must, it would seem, possess something of the science. But here too, then, it is clear that actuality is in this sense also, viz. in order of generation and of time, prior to potency. (Metaphysics θ8, 1049b29–1050a3)

Here Aristotle states the puzzle of the habituation circle in terms of dispositions in general, rather than focusing on the disposition of virtue in particular. The disposition is what gets activated when the person performs the corresponding activity (AFD). But the disposition arises from the activity (DFA). For example, in order to play the lyre one must (already) know how to play it; likewise, the person who does geometrical calculations must (already) know geometry. In order to be in the process of learning— to be engaging in the activities of building or geometrical construction—one must already have the art one is learning. So how is the agency of the learner—doing the relevant action without but in order to acquire the relevant disposition—possible?

Aristotle’s answer in this passage is that it is possible because the learner has some of the disposition: ‘the learner must, it would seem, possess something of the science.’ When he is done learning, he will have all of it. The crucial innovation Aristotle has introduced here is the idea that dispositions are complexes, and have parts. He wants us to understand a case of knowing some geometry, or having some facility with the lyre, as a case in which one has a part, but not the whole, of the disposition. Aristotle’s answer here effectively qualifies the truth of AFD: actions can come not only from corresponding dispositions but also from parts of the disposition.

Aristotle makes the corresponding qualification in DFA, to the effect that the activities of the learner are themselves not full or perfect instances of the corresponding kind. In the same passage, he mentions in passing that those who are learning by practice do not engage in the relevant activity ‘except in a limited sense’ (Meta. θ8, 1050a14). He does not, however, offer more details as to what engaging in an activity in a ‘limited sense’ amounts to. But he does precisely this in his discussion of the habituation circle in NE II.4.

4.3 Acting partially virtuously in NE II.4

After stating the problem (1105a1721, previously cited), Aristotle observes:

One can do something literate both by chance and at someone else’s prompting. One will only count as literate, then, if one both does something literate and does it in the way a literate person does it; and this is a matter of doing it in accordance with one’s own expert knowledge of letters. (II.4, 1105a22–6)

Introducing a qualification on DFA breaks the habituation circle, since it becomes possible to acquire a disposition by performing an action in a different and defective way compared to the way in which a person will perform it once he has acquired the disposition. Later, Aristotle describes this qualification specifically with reference to the case of an ethical disposition:

So things done are called just and moderate whenever they are such that the just person or the moderate person would do them; whereas a person is not just and moderate because he does these things, but also because he does them in the way in which just and moderate people do them. So it is appropriate to say that the just person comes about from doing what is just, and the moderate person from doing what is moderate; whereas from not doing these things no one will have virtue in the future either. (1105b512)

It is possible to do just and moderate actions in two ways.

(1) in the fully just and moderate way that the just or moderate man does them;

(2) in the qualified way that the learner does them.

In between the two passages quoted above, Aristotle explains what differentiates (1) from (2). The fully just actions of the person who has already acquired justice meet three additional conditions: ‘first, if he does them knowingly, secondly if he decides to do them, and decides to do them for themselves, and thirdly if he does them from a firm and unchanging disposition’ (NE II.4, 1105a31–3).

An action is done in a partly just manner if the agent (1) lacks knowledge, (2) fails to choose it for its own sake, and (3) has a changeable character. (3) paraphrases the fact that he is a learner—his character is in transition, which is precisely why he must act from only a partial (but growing) ethical disposition. This is in effect a reiteration of the qualification on AFD covered in more detail in the Metaphysics theta 8 passage discussed above. (1) is a consequence of (3), given Aristotle’s thesis of the unity of the virtues: he holds that the (practically) intellectual virtues are conditional on the possession of the ethical ones. What, then, do we make of (2), choosing the action for its own sake? What does it mean that the learner fails to (fully) meet this condition?

As Marta Jimenez (2016) has argued, this cannot mean that he performs the action from an ulterior motive such as a desire for money, status, or appetitive pleasure. In that case he would become habituated into acting on that (bad) reason, and such actions would never qualify as just, or moderate, or brave. Rather, it must be that he comes, more and more, to appreciate the value of acting courageously—to take pleasure in courage itself. How does that happen?

In order to answer this question, we will have to describe in more detail what it means to do something ‘partly’ for its own sake—or to have ‘part’ of a virtuous disposition.

5. Acquiring new pleasures

Habituation is a matter of doing a (somewhat) virtuous action from a (somewhat) virtuous disposition so as to act (somewhat) more virtuously from a (somewhat) more virtuous disposition. The question is, motivationally speaking: what drives this process? Aristotle holds that we are motivated by pleasure and pain, but it is precisely the mark of not yet being habituated to fail to take pleasure in the right sorts of actions. How do the wrong sorts of motivations motivate us to acquire the right ones? Notice that this problem arises for ethical habituation specifically, as opposed to craft habituation, which does not involve a habituation of the motivational faculty itself. Rewards and incentives can come in ‘from the outside’ to fuel the person’s training in some arena of technical competence. In ethical habituation, however, the person’s capacities for pleasure and pain place restrictions on the actions she can perform to habituate herself.

In an influential paper, Myles Burnyeat (1980: 78) argues that we come to experience virtuous actions as enjoyable by performing them:

I may be told, and may believe, that such and such actions are just and noble, but I have not really learned for myself (taken to hear, made second nature to me) that they have this intrinsic value until I have learned to value (love) them for it, with the consequence that I take pleasure in doing them. To understand and appreciate the value that makes them enjoyable in themselves I must learn for myself to enjoy them, and that does take time and practice—in short, habituation.

Burnyeat is surely correct that this is Aristotle’s view, but he does not address the question of how such process of coming-to-take-pleasure works, and, more specifically, he does not explain how I can come to take the ‘right’ sorts of pleasures by doing an action that springs from the ‘wrong’ sorts of pleasures.

Hallvard Fossheim (2006) notes this lacuna, and argues that it is the mimetic character of the trainee’s actions that make them pleasant: the trainee imitates virtuous acts of those around her, and the production of mimetic representations is, quite generally, a pleasant activity. This account has a number of virtues, one being that such pleasures are not ‘ulterior motives’—they are plausibly understood as pleasure in the very act (of representing) itself, and likewise tied to an appreciation of what one is representing.

Fossheim may be right that habituation involves mimesis. But invoking mimesis does not, of itself, explain the dynamic process by which the action becomes less and less of an imitation as one becomes more and more virtuous. This is not true of other forms of mimetic representation, such as acting in a play. Those representations are simply indulged in for some period and subsequently come to an end. We will need to say more to explain how, in habituation, mimetic pleasure, decreasing over time, gives way to the correct pleasure taken in the action for its own sake.

If we want to pinpoint the mechanism for changes in one’s faculty of pleasure-taking, we should turn to Aristotle’s psychology. His conception of the divided soul in I.13, already discussed, provides him with the resources to explain the kinds of changes to which our affective condition is subject. Given that ethical virtue is a matter of the condition of the affective part of our soul, Aristotle must think that the actions we perform shape or influence the organization of this part of our soul.

What shape do they give it? Whatever shape the action has. The goodness of a good action lies in the fact that it is in accord with a rational principle, a principle having its source in the intellectual part of the soul. Like Plato, Aristotle sees the intellectual part as being the ‘most authoritative element’ (IX.8, 1168b) of a human being: ‘For each person ceases to investigate how he will act at whatever moment he brings the origin of the action back to himself, and to the leading part of himself; for this is the part that decides’ (III.3, 1113a5–6).

The intellectual part grasps some rational principle (orthos logos: see VI.1) and the person acts in accordance with it. Consider Aristotle’s definition of ethical virtue as ‘a disposition, issuing in decisions, depending on intermediacy of the kind relative to us, this being determined by rational prescription and in the way in which the practically wise person (phronimos) would determine it.’ (II.6, 1106b36–1107a2) This is a striking definition, considering that decision, reason, and practical wisdom are all features pertaining to the other part of the soul—the intellectual, not the affective. Aristotle’s thought is that it is virtuous to have one’s passions arranged in the way that precisely conforms to and supports the reasoning work of the rational part of the soul. Though the affective part is not rational in the sense of being able to produce reasoning, it is receptive to the rationality of the intellectual part.[8]

The affective part of the soul becomes virtuous by (gradually) taking on the organization of the intellectual part of the soul. The mechanism of this transformation is action: every action has an intellectual principle, and when someone acts in accordance with that principle, the principle comes to shape who he is. The affective part of the soul is precisely a capacity to be affected; and we ourselves (qua intellectual) are among the things by which we ourselves (qua affective) can be affected. When we act in accordance with the intellectual part of our soul, our affective part becomes rational in the sense in which someone is rational in listening to a rational adviser (I.13, 1102b29–1103a3). We shape ourselves by heeding our own advice. In this sense, we become what we do: the order of our actions informs the order of our feelings. We thereby come to take pleasure in what we (rationally grasp that we) ought to do, and be pained by what we (rationally grasp that we) ought not do.

This does not necessarily or unfailingly happen—I can insulate myself from being ‘educated’ by my actions if, for instance, I feel ashamed of what I did. Hence Aristotle thinks of shame as a semi-virtue, appropriate only for the young. It is both ‘occasioned by bad actions’ (IV.9, 1128b22)—which presupposes that one has acted badly—and functions as a restraint on future actions—‘young people should have a sense of shame because they live by emotion and get so many things wrong, but are held back by a sense of shame’ (IV.9 1128b17–18). Shame could, then, be understood as a corrective on the usual process of habituation, in that shame sets up a wall of resistance to having one’s passions informed by the logic of one’s action. Assuming that one does not set up such a barrier, one steers a course towards becoming what one does.

The cognitive aspects of action—the action’s intellectual principle—creates an order in the affective aspects of the soul of the person engaging in it. When a learner acts, practising the disposition in question, she is acting on herself. She thereby comes to take pleasure in accordance with the rule (logos) in question, and to feel pain in violations of it. Thus practice changes our sources of pleasure or pain. If this were all there were to the story, then practice would not constitute learning, but rather the embodying or realizing in the soul of the learning one has already done. And that learning would be the product of teaching, since while the affective part of the soul is educated by habituation, the intellectual part is educated by teaching. But the conclusion that teaching is the ultimate driver of moral education is, we have already seen, in tension with Aristotle’s avowed anti-intellectualism.

Recall Aristotle’s warning against attempting to acquire virtue by listening to speeches, and his insistence that works of ethics are useless to those who have not been well habituated. Aristotle understands ethical virtue as paving the way for acceptance of rational content by the intellectual part of the soul; in the passage quoted at greater length above, he says knowledge brings profit ‘for those who arrange their desires, and act, in accordance with reason’ (NE I.3, 1095a10–11). If this is so, how does one come to desire and act in accordance with a rational principle? We seem to be back in a version of the circle: it is knowledge in the intellectual part that drives the actions that habituate the affective part, but it is only when the affective part is habituated that the intellectual part is receptive to knowledge.

Practice may, as I have been asserting, have hedonic powers; but it also, as Burnyeat (1980: 73) observes, has cognitive powers. I propose that in order to explain how practice can improve cognition and conation, we have to acknowledge an asymmetry between the two parts of the soul. It is true that each is necessary for the well-functioning of the other—this is a version of Aristotle’s doctrine of the unity of the ethical and intellectual virtues (VI.12–13)—but it cannot be that for every advance in ethical virtue, the corresponding intellectual advance is already presupposed. If that were the case, there would never be any felt need to move further.

The progress of habituation is self-guided—something the agent does, albeit with outside assistance—and so he needs access to a perspective on which his current situation seems in need of rectification; this, in turn, requires misalignment between the parts of the soul. Thus we must construe each advance in affective virtue as making possible a further but distinct advance in intellectual virtue—and vice versa. Let me discuss this point by way of an example.

Anyone who has commanded a reluctant child has faced the hopeless prospect of providing him with an endless list of corrections and clarifications. Sometimes one adopts the strategy of continuously barking commands and criticisms at him, and this can bring about a result in the vicinity of the desired one, but it is not satisfying. One feels that one has eviscerated the project of parenting by adopting the role of a puppeteer. For one never ends up at the endpoint one was wishing for, which is to be able to praise one’s child for what he has done. The problem is both that the child does not know how to do the relevant task well and at the same time that he does not care enough about its being done well to appreciate the various distinctions and niceties that would go into learning. In one’s better moments as a parent, one takes a different approach. One lowers one’s sights, divests oneself from concern with the quality of the end result, and produces a simpler, more digestible command.

The value of the simpler command to do the less valuable action is that the child can take pride and pleasure in doing it successfully on his own. Perhaps he cannot put all the toys back in their proper places, but he can work to gather them all in a given box. And once he has learned how to do that simpler task well on his own, one can introduce a small refinement, one which the child is in a position to see as a way of improving what he was doing earlier.

If I allow the child to incorporate some instruction before introducing more, I am giving him a chance to, as we say, ‘get a feel for’ the relevant task. When a child learns in this way, he is developing a certain kind of disposition. Engaging in the action corresponding to the (simple) instruction allows the affective part of his soul to take on the order corresponding to that instruction. Once this has happened, he has an easier time grasping the point of subsequent refinements, which can in turn ready him for further refinements. We call this ‘getting a feel’ because one comes to feel and therefore doesn’t need to check that one is doing the action correctly. What he does becomes what he has learned, and that allows him to do more and learn more.

By contrast, consider instruction by way of a list of rules. It doesn’t matter whether the rules are received as a series of spoken commands, or a visual checklist, or memorized and internally consulted. The person who aims to follow instruction given in this format will have to repeatedly observe what he is doing and check whether it conforms to the rules. The detachment that can be engendered by this approach—‘am I going through the right sorts of motions?’—is an alternative to what I have described as having a feel for the right way of proceeding. Nonetheless, the checklist approach may produce a good result. For instance, in medicine it has been claimed that surgical checklists save lives (Gawande 2007). The limit case of this is machines, which produce very good results relying exclusively on lists of rules.

Craft habituation has much in common with ethical habituation: they both require part-by-part change, both involve learning by doing, and both are characterized by the DFA-AFD circle (see fig. 3.1). But there are important differences. First, in craft the disposition acquired needn’t involve taking pleasure in the relevant activity. Second, in craft the actions that bring about the disposition needn’t be the product of free choice: a slave can acquire a craft, under duress. Perhaps the deepest difference between craft habituation and ethical habituation, however, lies in the question of how necessary they are in the first place.

In the case of craft, Aristotle notes, mere success in respect of the product, irrespective of how it was brought about, suffices for us: ‘the things that come about through the agency of skills contain in themselves the mark of their being done well, so that it is enough if they turn out in a certain way’ (II.4, 1105a27–8). In ethics, our goal is that the action should be able to be done for its own sake, from an affective grasp of the importance of acting in this way—as ethical habituators, our target is the affective condition of someone’s soul. We care not (only) that the result was achieved, but also how it was achieved. A craftsman is in principle replaceable by a rule-following machine, but ethics is not subject to the same substitution.

Habituation is the way in which we learn not only how to be ethical but also how to be good at driving, hairdressing, or cooking. In all cases, practice ingrains in the person the feel for what they are doing that allows them to acquire further refinements in an intelligent way. However, this fact is a deeper fact about ethics than it is about habituation in other areas. In the case of craft, it merely happens to be the case that acquiring a disposition is a useful way to bring about the relevant result; sometimes we bypass habituation using checklists or, for that matter, machines. Habituation is essential to the practice of ethics in a way in which it is not essential to the existence of craft objects, because in the latter case all that we care about is that a set of rules are followed, but not (necessarily) that they are followed from the relevant motivational makeup.

We want the ethical learner’s sense of the rightness of what she is doing to be properly internal to her. The target of ethical habituation is not to give rise to a set of actions but rather to give rise to the kind of person who will do such actions for their own sakes. As we have seen, Aristotle holds it to be distinctive of the ethical good that praise must be appropriate to it, and this in turn means that the action must come from within the agent in a substantive sense. It must spring from an inner principle that informs what she takes pleasure in. That’s what habituation does: it turns an ethical rule into a principle of action for a being for whom it was not by nature a principle.

Habituation is possible because my affective and my intellectual improvement are mutually reinforcing without being fully mutually dependent on one another. The circle of Aristotelian habituation is broken by the fact that the two parts of the soul are, in their imperfectly developed state, decoupled enough to act on one another. On the one hand, improvements in my understanding of a rule happen by way of its coming to more fully inform the affective part of my soul. As Aristotle said (I.3, 1095a2–16, previously cited section 3.4.1.2), learning is only of benefit to those who have acquired the right dispositions by way of practice—only such people will be in a position to further ‘internalize’ an understanding of the rule/instruction (logos). On the other hand, those very improvements in my affective condition are themselves products the of rule-governed actions—which is to say, of my intellectual acquisitions.

The more I understand the rule, the more I am able to affectively inhabit it, and the more I affectively inhabit it, the better I understand it. This interplay is productive because defects in the two parts of the soul do not perfectly mirror one another. My growth can be represented not as a circle, but as a spiral (see Fig. 3.2: VD = ‘virtuous disposition’; VA = virtuous activity).

Aristotle’s thesis of the unity of the virtues requires that my (intellectual) grasp of a rule cannot be perfected so long as imperfections remain in my affective condition, and vice versa. It does not, however, follow that defects in the one part translate into corresponding defects in the other. That would only be true if the two parts of the soul were by nature, i.e. pre-habituation, in a complete state of harmony. But Aristotle denies that this is the case, observing that the two parts can stand to one another in the relation that someone stands to her own paralysed limbs (I.13, 1102b13–28). So, for instance, the akratic is someone who has a reasoned decision in the intellectual part of her soul, but fails to act on it due to imperfections in her affective condition. Such a person has the universal knowledge of how one ought to act in her circumstances (1151a20–1151a28[9]), despite a defect in her affective condition. Such a person is akin to one who understands what she has been commanded to do, but is disinclined to obey the command. (Recall, once again, Aristotle’s comparison between akratics and the city that fails to enforce its laws: VII.10, 1152a20.)

Likewise, the phenomenon of ‘natural virtue’ (VI.13[10]) reveals the possibility of a gap in the opposite direction. ‘Natural virtue’ is a virtue-resembling, unhabituated condition in which our passions, by accident of birth, take on some order that has the appearance of the one habituation would produce. This condition is one that not only (pre-habituated) human children but also non-human animals can be in. A naturally virtuous person is in an affective condition that resembles that of the courageous or moderate person while lacking the corresponding intellectual grasp of the rule. Thus we can call a non-human animal, such as a lion, naturally ‘courageous’ despite the animal’s lacking the intellectual part of the soul entirely.

(It’s worth clarifying that ‘natural virtue’ is not a kind of virtue, and a ‘naturally virtuous’ person is not virtuous, i.e. ethically good. As noted above, Aristotle believes that we do not have virtue by nature. ‘Natural’ in ‘natural virtue’ is an alienating term, so that the phrase should be read as something like: an analog in the natural world to what virtue is in the ethical one.)

The possibility of akrasia and natural virtue allows us to make a conjecture as to the ‘entry point’ for habituation, which is that habituation gets going on the basis of the individuals having (some) natural virtue and (some) access to explicit moral commands from parents, teachers, and lawmakers. The two parts of the soul have, in this way, independent origin stories, and these two parts do not fully line up until the person acquires (full) ethical and intellectual virtue. This misalignment makes it possible for the parts to improve one another: my failure to fully comprehend the rule (logos) can be rectified by my taking pleasure in following it, but also my failure to take full pleasure in following it can be rectified by my acting in accordance with (whatever limited intellectual grasp I currently have of) the rule. Aristotle’s thesis about the unity of the virtues is also a theory about when the soul is unified—and when it isn’t. The disunity of the soul makes virtue acquisition possible, and the unity of virtue is the unity of the soul.

For human beings, unity of soul is an achievement: virtue brings the parts of the soul into alignment. Until it is achieved, the parts of the soul are disunified enough to break the virtuous cycle. Because virtue is what unifies the soul, it constitutes a perfection of our natural condition; because the soul is not, by nature, unified, its habituation into virtue is a possibility.

It is not currently fashionable to understand human beings as divided into Reason and Passion, for it seems to us that most of what we do is thoroughly permeated by both. Aristotle would agree. He does not ever seem inclined to factor out motivation into its intellectual and affective components. The dividedness of the soul is relevant not for the synchronic analysis of virtuous (or vicious) action but in order to have a story to tell about how such action comes into being. If habituation is to be the work of the agent herself, she must act upon herself, and that in turn generates a psychology of self-distance. Dividing the soul into affect and intellect gives virtue a way to come into being. The division of the soul is not a story about a soul standing still; instead, it offers Aristotle the materials to account for a distinctively ethical form of change.

References

Barnes, J. (ed.) 1984. The Complete Works of Aristotle. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Broadie, S. (ed.) and C. Rowe (trans.) 2002. Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Burnyeat, M. 1980. Aristotle on learning to be good. In Amélie Oksenberg Rorty (ed.), Essays on Aristotle’s Ethics. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Callard, A. 2017. Enkratēs Phronimos. Archiv für Geschichte der Philosophie 99(1): 31–63.

Fossheim, H. 2006. Habituation as mimesis. In T. D. J. Chappell (ed.), Values and Virtues: Aristotelianism in Contemporary Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gawande, A. 2007. The checklist. New Yorker, 12 Oct.

Jimenez, M. 2016. Aristotle on becoming virtuous by doing virtuous actions. Phronesis 61(1): 3–32.

Further Reading

General overview of Aristotle’s Ethics

Cooper, John M. 1986. Reason and Human Good in Aristotle. Indianapolis: Hackett.

Broadie, Sarah. 1991. Ethics with Aristotle. New York: Oxford University Press

Bostock, David. 2000. Aristotle’s Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Human function

Kraut, Richard. 1979. The peculiar function of human beings. Canadian Journal of Philosophy 9(3): 467–78.

Barney, Rachel. 2008. Aristotle’s argument for a human function. Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy 34: 293–322.

Akrasia

Destrée, Pierre. 2007. Aristotle on the causes of akrasia. In Christopher Bobonich and Pierre Destree (eds), Akrasia in Greek Philosophy: From Socrates to Plotinus. Leiden: Brill.

Pickavé, Martin, and Jennifer Whiting. 2008. Nicomachean Ethics 7.3 on akratic ignorance. Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy 34: 323–71.

Friendship

Annas, Julia. 1977. Plato and Aristotle on friendship and altruism. Mind 86(344): 532–54.

Brewer, Talbot. 2005. Virtues we can share: friendship and Aristotelian ethical theory. Ethics 115(4): 721–58.

Kahn, Charles H. 1981. Aristotle and altruism. Mind 90: 20–40.

Pleasure

Gosling, J. C. B., and C. C. W. Taylor. 1982. The Greeks on Pleasure. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Wolfsdorf, David. 2013. Pleasure in Ancient Greek Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Reason vs passion

Lorenz, Hendrik. 2006. The Brute Within: Appetitive Desire in Plato and Aristotle. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

McDowell, John. 1996. Incontinence and practical wisdom in Aristotle. In Sabina Lovibond and Stephen G. Williams (eds), Essays for David Wiggins: Identity, Truth and Value. Oxford: Blackwell.

The best life

Lawrence, Gavin. 1993. Aristotle and the ideal life. Philosophical Review 102(1): 1–34.

Lear, Gabriel Richardson. 2000. Happy Lives and the Highest Good: An Essay on Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

[1] Aristotle calls these two parts of the soul ἄλογον and λόγον ἔχον (I.13, 1102a27–8), which makes it natural to reach for the labels ‘rational’ and ‘irrational’ when referring to them. However, this bit of terminology must be taken with a grain of salt, for the following reasons. (1) Aristotle specifies that in applying these labels he is simply following a (probably Platonic) convention. (2) He goes on to subdivide the ‘irrational’ into the part relevant to ethical virtue and a nutritive part irrelevant to virtue (1102b11). He distinguishes the part of the ‘irrational part’ that I call ‘affective’ from the nutritive part precisely on the grounds that the affective participates in reason in a way (1102b13–14). (3) He seems open to classifying both (what I am calling) affective and intellectual as sub-parts of ‘what has reason’ (διττὸν ἔσται καὶ τὸ λόγον ἔχον, 1103a1–2). For these reasons, the labels ‘rational’ and ‘irrational’ are misleading, and incline the reader to conceive of the part of the soul corresponding to ethical virtue as less rational than Aristotle understands it to be. For these reasons, as in Callard (2017: 32 n. 2), I adopt the convention of identifying the two parts of the soul not by the presence of absence of reason, but by the characteristic activities Aristotle associates with each part: feeling (affect) and thinking (intellect).

[2] See §3.3.2 for a discussion of what Aristotle calls ‘natural virtue’.

[3] Aristotle’s discussions of this point can be found at Phys. VII.3, 245b9–a1; Meta. θ7, 1049a18–24; Meta. Z7 1033a16–22

[4] ‘So, too, among things living and among animals we often see things suffering and acting from force, when something from without moves them contrary to their own internal tendency’ (EE 1224a20–23).

[5] Rowe’s (2002) translation of this clause reads, ‘for the way we learn the things we should do, knowing how to do them, is by doing them.’ I find Rowe’s English, specifically the grammatical role of the clause in commas, hard to construe. For this reason I have supplanted his translation of the quoted phrase with the one in Barnes (1984).

[6] For the distinction between potentiality and actuality, see n. 7.

[7] For the distinction between potentiality and actuality, see Metaphysics θ.6, where Aristotle says that it cannot be analysed into simpler terms, but can only be elucidated by analogy: the potential stands to the actual as what can build stands to what builds, or as waking stands to sleeping, or as having one’s eyes shut stands to seeing, or as matter to stands to what it composes, or as the unwrought stands to the wrought.

[8] See n.1.

[9] See esp. 1151a25–6: ‘the best thing in him, the first principle, is preserved.’

[10] Cf. EE III.7, 1234a24–33.