Amy Brady

‘I Don’t Think Those Feelings of Self-Doubt Ever Go Away.’

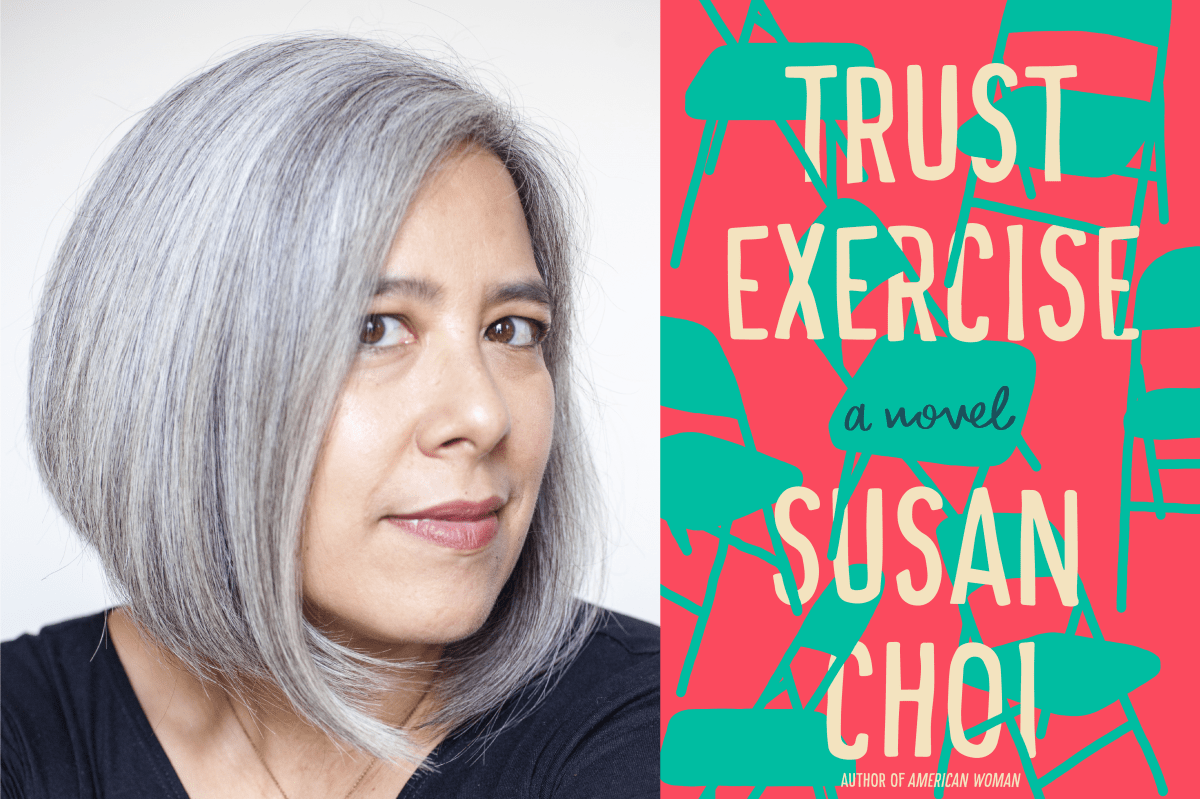

Susan Choi talks about feeling unsure of oneself, as a writer, as a performer — or as a victim — and about how her latest novel evolved in uncanny tandem with the real world.

Amy Brady | Longreads | April 2019 | 10 minutes (2,627 words)

The truth has never been a universally agreed upon concept. As most psychologists will tell you, a shift in perspective can alter how a situation feels as well as what it means. And most historians agree that the “truth” of any significant event changes depending on who’s telling the story.

In her astounding fifth novel Trust Exercise, Susan Choi plays with both perspective and narrative structure to tell the truth, or “truth,” about a group of suburban performing arts high school students. The book begins with Sarah, a fifteen year old in deep lust with her peer, David. Their friends, Karen and Joelle, and outcast Manuel, round out the teenage cast. Martin is a theater teacher from England who spends a couple of weeks at the high school, and Mr. Kingsley is their beloved theater teacher who makes the students participate in trust exercises usually reserved for older, more experienced actors. His questionable teaching style and Martin’s over-familiarity with the students are clues that the adults view the teens as both children and grown-ups, as needing guidance to navigate the professional world of acting but as also already possessing the emotional development needed to withstand the cruelty it bestows upon them.

As the novel unfolds, Choi captures the rage and lust of teenage life with thrilling verisimilitude. Who hasn’t felt the devastation of unrequited love as a horny fifteen year old? Or felt mistreated in a friendship? Or held a secret from a parent? Choi’s descriptions of her characters’ psychological interiors are equally adept: The teens walk assuredly into a classroom one moment, only to feel crushed by self-doubt the next, their self-confidence ruled by roiling hormones.

The novel’s authenticity is what makes both of its structural shifts, when they arrive, so shocking; the lives of these teens feel too real to be anything but the truth. But after each shift, everything in the story that came before is changed — changed but not entirely undone. It’s as if we had been reading the novel through a telescope only to be handed a kaleidoscope to finish it; the story’s pieces are all still there, but now they are arranged in different and surprising ways.

The shifts bring revelations about what the students endured from their teachers and parents and each other. Some of the revelations are amusing in their familiarity. Others are heartbreaking for the same reason. Trust Exercise is a novel that resonates with the #MeToo movement, but it’s also a story as old as time — it’s about those in power taking advantage of those who are powerless to stop them.

Readers of Choi’s previous work will not be surprised by the novel’s thematic ties to real-life headlines. American Woman (2003) was based on the kidnapping of newspaper heiress Patty Hearst by the Symbionese Liberation Army. Her 2008 novel, A Person of Interest, was drawn from the paranoia and ideology of Ted Kaczynski, a man better known as the Unabomber. Trust Exercise captures the mood and mindset of a world undergoing a sea change in terms of how we think of sexual consent. Its themes echo with those of My Education, Choi’s 2013 novel about a graduate student who gets involved with a dangerous and charismatic professor. Choi spoke with me over the phone about the inspiration for Trust Exercise, as well as about her own experiences as a teenager and a “theater kid.” The interview has been edited slightly for clarity and length.

*

Amy Brady: Your previous novels were based loosely on real events. What about Trust Exercise? It certainly speaks to the #MeToo movement. Was there a particular news story that inspired this book?

Susan Choi: No, not really. This was a book that accumulated over a long span of time. In fact, I wrote the earliest pages of it so long ago that I couldn’t say exactly when I wrote them. But it was definitely before My Education was even published, so before 2013. I was working on another novel at the time, a novel I’m actually still working on.

So Trust Exercise was the side project.

Yes, at first I thought it might even be a short story. But I kept going back to it. I felt drawn to it, a feeling that I’m sure was influenced by the things I was reading about in the news. Looking back, I can see that my losing interest in that other project was the result of so many particular newsworthy moments.

Like what?

In 2015 I had just started teaching at Yale. A painful kind of eruption of debate and discussion and disagreement took hold of the campus that year surrounding race and power and safety. A lot of that discussion was prompted by students, and as a teacher, I felt it was important for me to listen. Then, the following fall of 2016 — which I’m sure you remember well — our nation’s political life took a turn that a lot of us, me included, didn’t expect. Then a year after that came the memorable fall of Harvey Weinstein. At that point I had finished so much of Trust Exercise that it finally became clear to me that it was the project I was meant to be working on and not that other book. It was only then, when I had almost finished it, that I became conscious of Trust Exercise as being a book, and not a short story. As the news stories surrounding [sexual consent] kept breaking, I felt like the book and the world around me were converging. It was a strange feeling. I’ve never had that happen before with something that I’ve written.

Bottom of Form

I recently read an interview you did for the Nassau Literary Review, wherein you talk about the “rules” of novel writing. You write that the novel is “expansive, hard to define; you can do as many things with it as you can think of to do. I don’t think there are that many rules, or that its purview is narrow.” That way of thinking seems to apply to Trust Exercise, which upends so many narrative conventions and rules.

I had forgotten I’d said that! That interview was with a former student of mine. I’m so glad that I’d said something in there that sticks in a valuable way.

I felt like the book and the world around me were converging. It was a strange feeling. I’ve never had that happen before with something that I’ve written.

So I’m surprised to hear you say that the writing of Trust Exercise happened over a long period, because the structure is just so exquisitely formed.

[Laughs] I’m glad that appears to be the case. But in truth, it was something that evolved over time, which makes the whole process sound like it happened smoothly. It didn’t. It evolved in leaps. I feel like there’s a Darwinian metaphor here that I can’t grab a hold of because science obviously was never my forte. [Laughs] But every time my interest in the novel waned and then came back again, I’d have this entirely new attitude toward it, and that new attitude is reflected in the book’s unusual structure.

Every section of the book sheds shocking light on the previous section, and when I got to the ending, I just kind of sat there stunned. I think I understand what happened, but I can think of a couple of different interpretations.

I’m tickled to hear that, because I love it when my novels leave room for multiple interpretations. Honestly, that’s very exciting to me. When people come back to me with interpretations of my work that I never thought of, it means that the book is working. It’s doing something all by itself, operating as a world of its own. That’s the best I can hope for.

There’s a particular moment of ambiguity in the novel that has stuck with me, a moment that I suppose becomes less ambiguous as you keep reading. Without giving too much away, I’ll say that it happens at the end of the second section with a woman, Karen, on stage, in the middle of a theater performance, doing a violent act against a man named Martin. At first I thought she was having some sort of mental break. But by the end of the book, her violence — and the rage that drove her to it — both made sense to me. I’ve been thinking about that moment because I realize that so many women in real life who act out with justifiable anger are often thought of as being just damned crazy.

Definitely. I think it’s a perception that a lot of women feel about themselves and in turn are made to feel about each other. It’s happening everywhere right now in our culture. One of the things I find powerful about that particular character is that she holds that same divided attitude toward herself. A part of her feels that she was wronged by an older man and that it’s her fault. But another part realizes she’s a victim.

The fact that there are already so many stories circulating around Martin doesn’t seem to help her figure out her feelings.

Right! She reads a newspaper article about Martin, and she thinks, well, the women in this article don’t have a case [against him], so neither do I. I wanted her doubt about what had actually happened between her and Martin to come across strongly in the book, because I wanted her struggle over whether she was a victim to be something the reader would also have to struggle with.

Why is that?

Because I think that’s a very real and relatable feeling, and also because I think we as a culture tend to struggle with how credible we find victims. There are times, for instance, when Karen seems like the sanest character in the whole story, the only person who sees anything for what it really is. And then there are other moments where it’s hard to take her seriously. I love that she can be both of those things. I think maybe there’s no way not to end up being both of those things.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Karen and your other characters’ psychology more generally, because this book captures so well a teenager’s drift of mind, the way that a teen can have staggering confidence one moment and then crushing self-doubt the next.

It’s nice to hear that that aspect of the writing works. There’s a part of me that always fears that my writing is too interior or associative, that the characters just ramble on too much in their mind.

You worry about that now? Even after four other books?

I don’t think those feelings of self-doubt ever go away.

I suppose that’s true. I sometimes still have the self-doubt of a teenager.

Self-doubt is something that’s so interesting about teenagers. We as a culture don’t really know what to think about people that age. On the one hand we tend to think of teens as little adults. But on the other hand, we believe they’re still children. And when you’re still a teenager, it’s hard to know how to think of yourself because you receive so many contradictory messages.

And then we grow up and it’s like nothing has changed, at least psychologically.

Yes! That’s what’s so striking to me about the [teenage mindset]. After we’ve grown up, we are still just as psychologically recognizable as we were when we were fourteen or fifteen years old. I see that in my close friends who I’ve known all my life — they’re different, certainly, but they’re also the same. For better or worse, the teen years are the beginnings of adult consciousness and all its associated craziness.

The book is working. It’s doing something all by itself, operating as a world of its own. That’s the best I can hope for.

This reminds me of a moment in the second section of Trust Exercise, when adult David reprimands adult Karen for justifying some questionable things they did as teens. She says they were just kids, but he corrects her, saying, “We were never really children.”

Yes, and a part of me agrees with him. I mean, [the characters] never really were kids. But then again, of course they were kids. They always were! That period of life is one of the most fascinating and consequential, and yet as adults we have such a hard time understanding and defining it. I’m now the parent of a fourteen year old who remains a very opaque person to me. I look at him, and I can’t help but wonder what’s going on inside his head. My inability to know is actually quite incredible to me, because I remember being fourteen. I remember that age very clearly, how you feel like you know everything and are very mature. Clearly that’s not true, but it certainly feels that way at the time. I remember all of that, and yet [my son] can still be such a mystery to me.

So speaking of being a teenager, I personally didn’t go to a performing arts high school, but I did theater in high school and stuck with the craft through college. I have to say, you really captured well the way that people talk backstage and handle difficult tasks like quick costume changes. Do you have a theater background?

I did theater in high school and in college, but I wasn’t a performer — I was a techie. I was one of those kids who had this momentary bloom of self-confidence that propelled me into a theater program. And then once I was in the program, the confidence left me and I was terrified of performing. I mean, I was mortified. It was such a strange situation to have put myself in — I was a participant in a performance program when the last thing I wanted to do was get up in front of anybody. So I ended up taking refuge in the techie world. I built sets and loved it. I still have a glue gun. When I went to college, I went straight into theater because it’s what I knew, but I stayed back stage. My [fear of performing] got so bad that I actually had to stop doing theater my junior year because I couldn’t graduate without a performance.

Do you still enjoy theater?

Oh yes, but I’m just an audience member now. There’s amazing theater in New York.

What’s next for you?

At the moment, I’m looking both backwards and forwards because there’s still that book that Trust Exercise distracted me from. And it is a project that I really care about, possibly too much. It’s about my father’s father who I never knew and who’s fascinating to me, because he’s such a complicated and remote figure. I never met him. He died before I was born. He had lived in Korea, which is also a point of interest for me, because I don’t speak a word of Korean. I’m just not connected to that side of my heritage, at least not through language. But this man, my paternal grandfather, was an extremely prolific writer, and I can’t read any of his work because it’s all in Korean. Some of it has been translated, but reading his work in translation feels odd to me. Clearly there are so many issues bundled up in his story for me, but the trick is figuring out how to make his story interesting to others. I hope I can figure it out, but who knows. I may end up writing an entirely different book again before ever finishing it.

* * *

Amy Brady is the Deputy Publisher of Guernica Magazine and the Editorial Director of the Chicago Review of Books. Her writing has appeared in Oprah magazine, The Village Voice, Pacific Standard, The New Republic, McSweeney‘s, and elsewhere.

Editor: Dana Snitzky