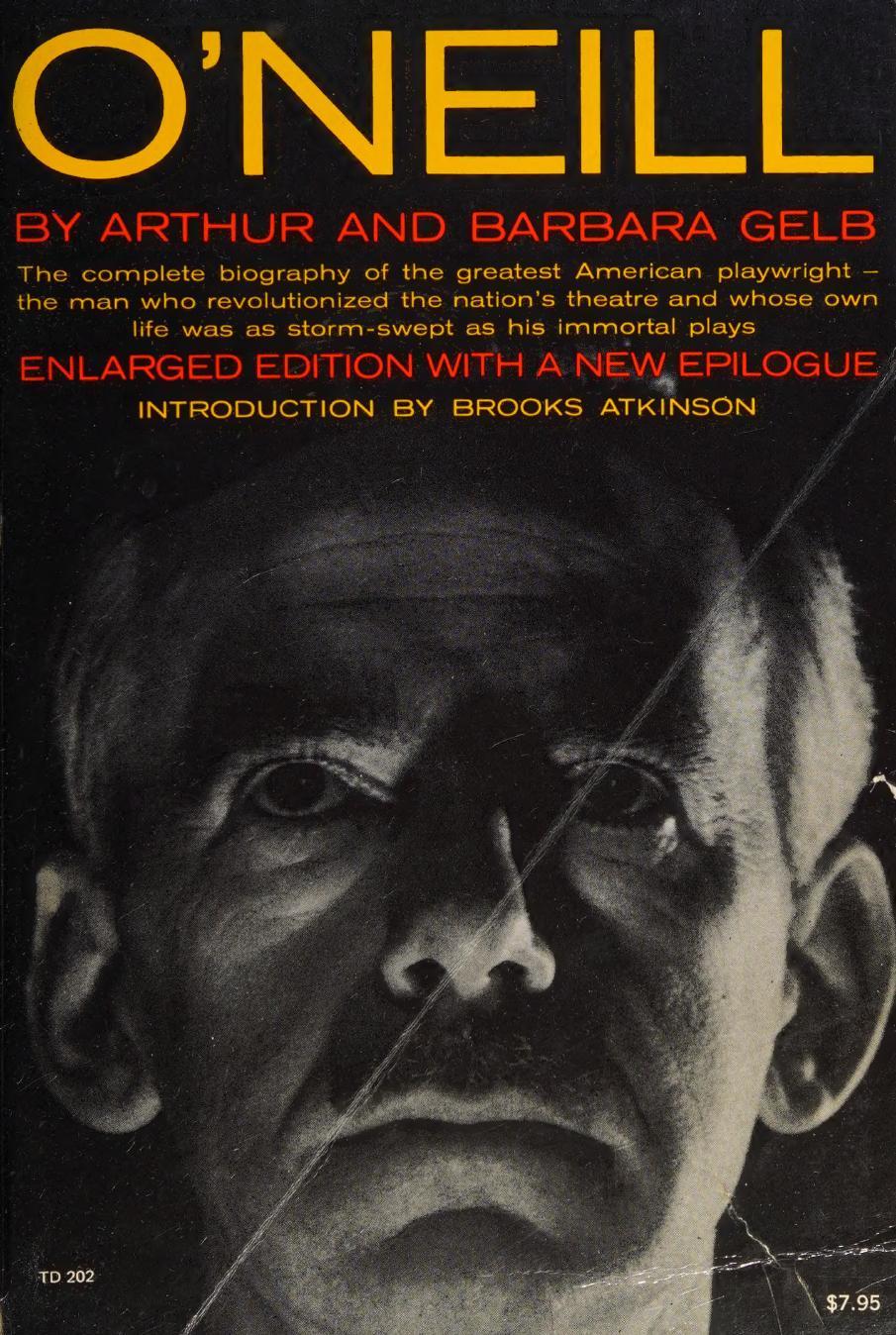

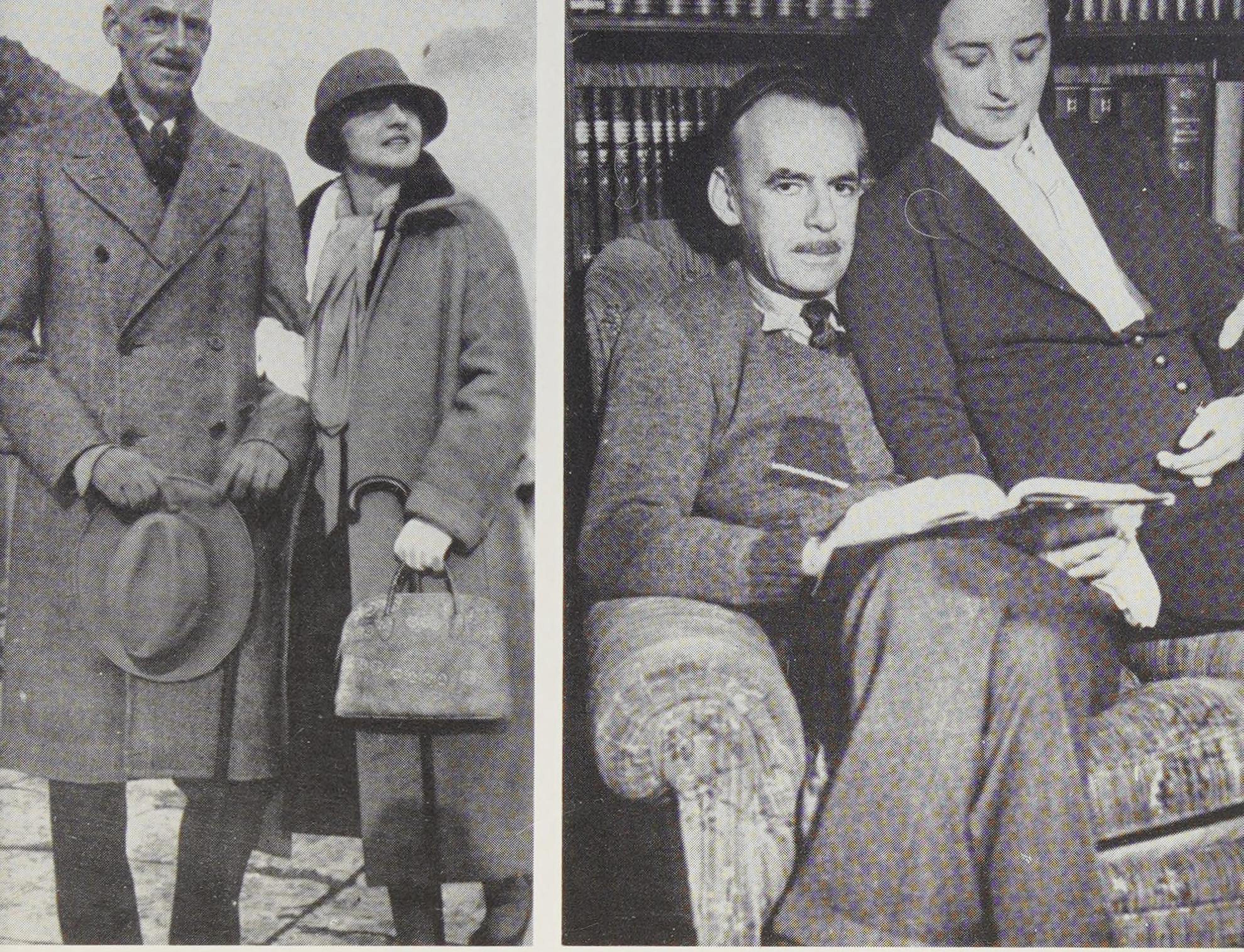

Arthur and Barbara Gelb

O’Neill

Part 1: Haunting Ghosts 1846—1912

Part 2: The Birth of a Soul 1912—1920

Part 3: The Makings of a Poet 1920—1926

Part 4: Wilderness Regained 1926—1936

Part 5: Hopeless Hope 1936—1953

Front Matter

Title Page

O’NEILL

NEW YORK, EVANSTON, SAN FRANCISCO, LONDON

ARTHUR & BARBARA GELB

HARPER & ROW • PUBLISHERS

[Copyright]

The first edition of O’Neill was originally published by Harper & Row in 1962.

Part of the material on O’Neill as a young man in New London first appeared in Horizon, March i960, under the title “The Start of a Long Day’s Journey.”

Copyright © 1960, 1962, 1973 by Arthur and Barbara Gelb.

For information address Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc., 10 East 53rd Street, New York, N.Y. 10022. Published simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, Toronto.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Gelb, Arthur. 1924-

O’Neill.

1. O’Neill, Eugene Gladstone, 1888–1953.

I. Gelb, Barbara, joint author.

PS3529.N5Z653 1974 812’.5’2 [B] 73–6760

ISBN 0-06-011487—8

[Dedication]

FOR DANIEL AND FANNY & THEIR FOUR GRANDSONS

Acknowledgments

A great many persons, libraries, institutions, organizations and publications have given their help and cooperation in the preparation of this book. We will never be able to thank all of them adequately, and can only try to outline the extent of their assistance and indicate the measure of our gratitude.

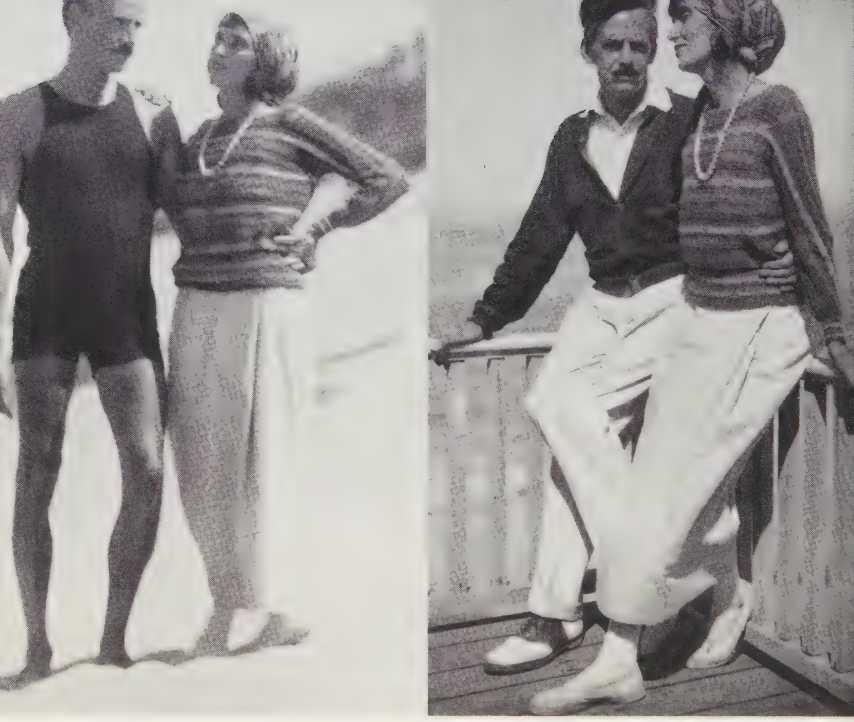

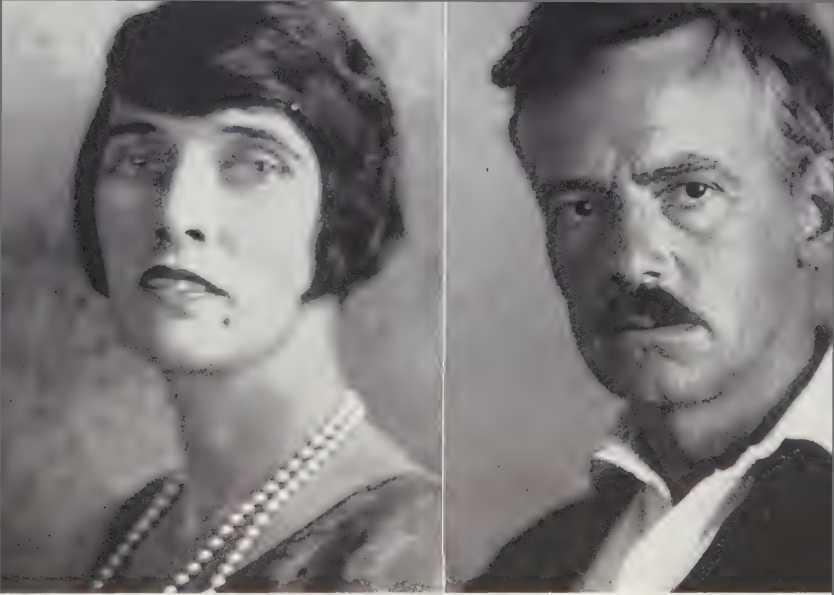

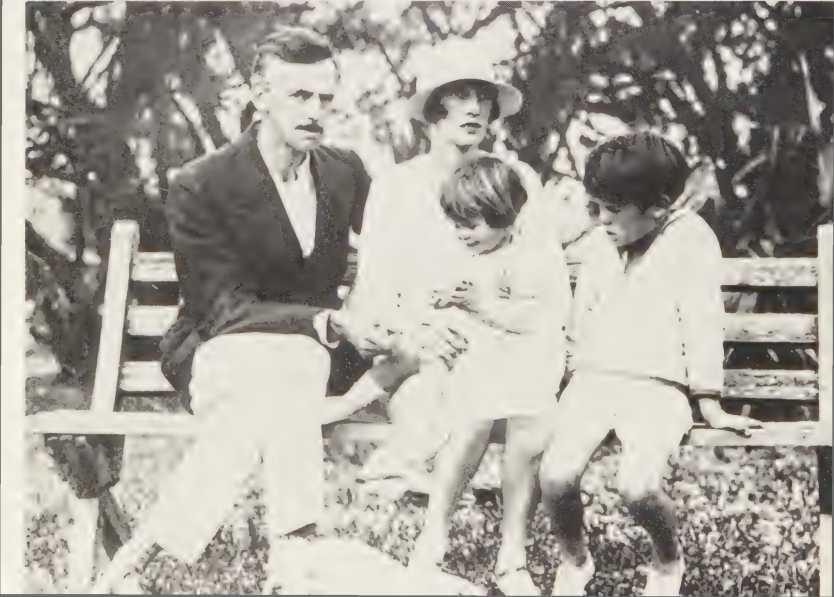

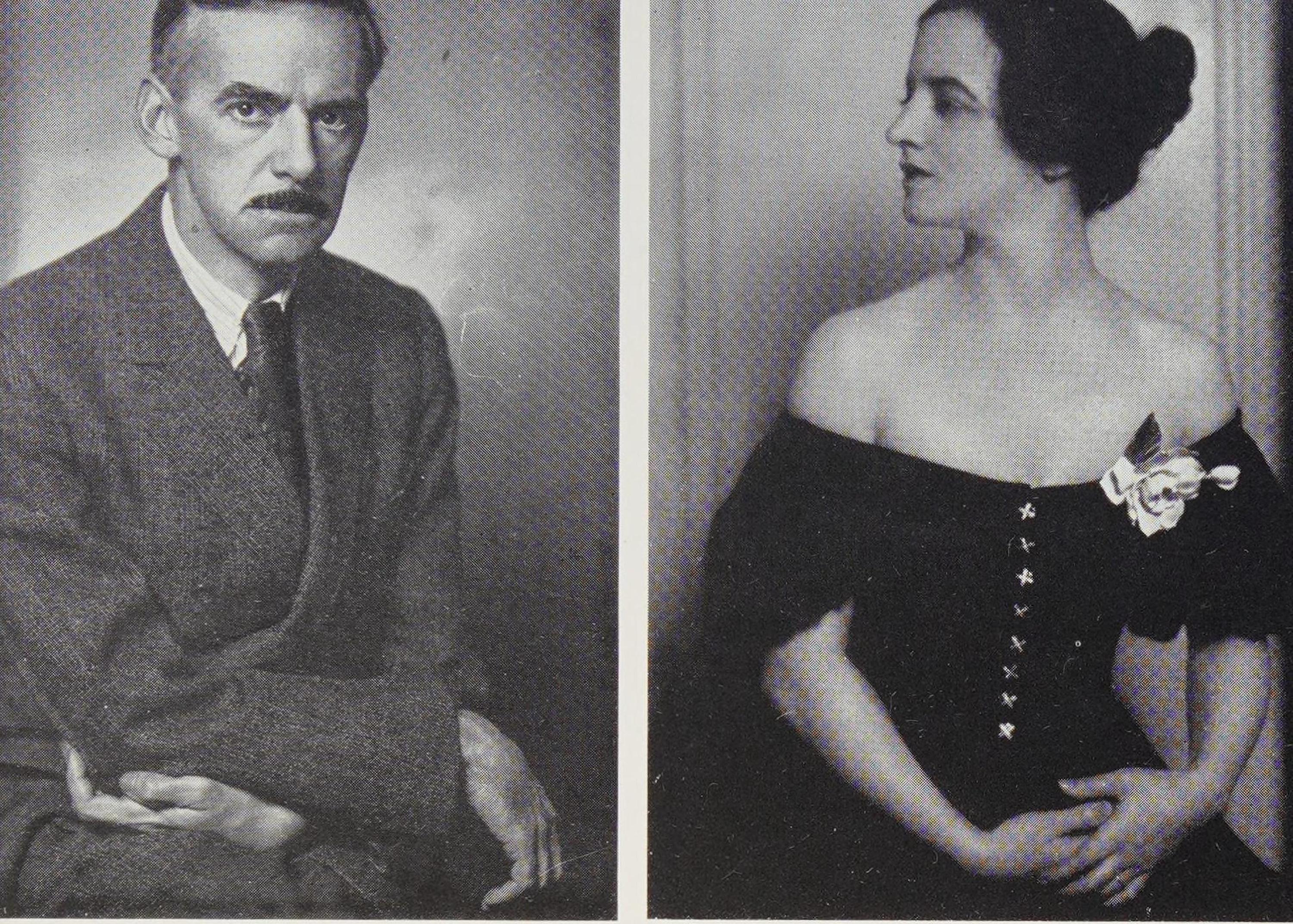

We acknowledge, first, our debt to Carlotta Monterey O’Neill. With the understanding that we were to have the freedom of complete objectivity, she graciously allowed herself to be interviewed on many occasions, put documents and photographs at our disposal, made us a gift of two privately printed volumes containing O’Neill’s writings, cleared our path at the Yale University Library’s O’Neill Collection, and facilitated and consented to our quoting from and using the published and unpublished works of her husband. Mrs. O’Neill entrusted us with the details of her life with her husband, forbearing to ask for any power of censorship or to review what use we made of the material.

O’Neill’s first wife, Kathleen Pitt-Smith (the mother of Eugene O’Neill, Jr.), and his second wife, Agnes Boulton Kaufman (the mother of Shane O’Neill and Oona O’Neill Chaplin), also furnished us with much valuable information. Mrs. Pitt-Smith granted us extensive interviews and showed us documents relating to her son; Mrs. Kaufman’s memoir, Part of a Long Story (Doubleday & Company, Inc.), provided a picture of the climate of her marriage to O’Neill between 1918 and 1920. We thank them both.

We are very much indebted to four people whose help, faith and encouragement over five years extended well beyond the bounds of friendship: S. N. Behrman, Brooks Atkinson, Dr. Philip Weissman and Clara Rotter, all of whom allowed themselves to be put upon constantly, and who became integrally involved, in one way or another, in this project.

Our deep gratitude is extended, also, to Oscar Godbout, an ardent O’Neill scholar, and Robert Siegel (who was converted to one)—both spent many hours of their spare time in pursuit of live and documentary information pertaining to O’Neill, which they duly and minutely conveyed to us; to Leonard Harris, who took time out from his professional obligations as a publisher and editor (not ours) to labor over our manuscript; to John Mason Brown, who packed up a suitcaseful of rare books for us and told us to keep them for as long as we wished; to Kenneth Macgowan, who was an invaluable source of information, about O’Neill, and who turned over his voluminous correspondence to us; to Frances Steloff, whose Gotham Book Mart was a gold mine of rare volumes and documents, and who spared us many hours of her time; to Irving Hoffman, who put us in touch with people who would otherwise have been inaccessible; to Robert Downing, an encyclopedia of the theatre, who read proofs and kept a sharp eye out for factual errors; to Russel Crouse, Saxe and Dorothy Commins, Angna Enters, Shirlee and Robert Lantz, David and Esther Hahin, Mr. and Mrs. Arthur McGinley, Ben and Ann Pinchot, Elliot Norton, James Joseph Martin and Charles O’Brien Kennedy, who, in addition to supplying us with information, extended to us, on more than one occasion, their hospitality; and to Lawrence Langner, who not only talked to us at length and on many occasions about his relationship with O’Neill, but generously allowed us to quote from his comprehensive autobiography, The Magic Curtain (E. P. Dutton & Company, Inc.).

Without the help of various libraries, our task would have been an impossible one. We wish first to thank the Yale University Library, whose O’Neill collection is the world’s foremost; Dr. Donald C. Gallup and James T. Babb extended us every courtesy in our research there. We are also grateful, at Yale University, to Steve Kezerian.

We are much obligated for the extensive help given us by the New York Public Library’s Theatre Collection, and to George Freedley and Paul Myers, who were never too busy to track down that one, last (only it never turned out to be the last) detail; also the library’s Berg Collection and John Gordan.

The Princeton University Library, through the good offices of Alexander P. Clark and Alexander D. Wainwright, made its O’Neill collection available to us and granted us many special favors. Dartmouth College was equally gracious in placing the facilities of its library at our command, and we wish to thank Bella C. Landauer, who was responsible for the gift of the O’Neill collection to Dartmouth, and who brought other O’Neill items to our attention. We also thank Donald D. McCuaig, Marcus A. McCorison and Professor Kenneth Robinson for their help at Dartmouth.

At Harvard University, with the assistance of William Van Lennep, we were permitted to examine the O’Neill documents on file at the Houghton Library’s Theatre Collection. St. Mary’s College furnished us with details of Ella O’Neill’s student days, and we thank Marion McCandless for her exhaustive letters of information and for her book, Family Portraits. At St. Mary s, we also appreciate the help of S. Robert Johnson.

Mrs. George Jean Nathan allowed us to see her husband’s O’Neill collection, now at Cornell University; we gratefully thank her, also, for allowing us to quote from the published writings of George Jean Nathan.

We owe a debt to the Museum of the City of New York and May Davenport Seymour; the University of Oregon and Horace W. Robinson; Fordham University and Burt Solomon; the Fales Collection of New York University; the University of Washington Library and Jessica Potter; the University of Pennsylvania and Neda M. Westlake; Connecticut College for Women and Hazel Johnson; the University of Notre Dame and James E. Armstrong; the Columbia University Library and Kenneth A. Lohf; the New London Public Library and Frank Edgerton; the Newberry Library and Amy Nyholm; the Boston Public Library and Richard G. Hensley and Mrs. Marjorie Bouquet; the Library of Congress Reference Division and Richard S. McCartney; the Library of Congress Manuscript Division and David C. Mearns.

Our thanks are due, as well, to Actors Equity and Alfred Harding; O’Malley’s Book Shop; the American Merchant Marine Institute and Frank Braynard; the Church of St. Ann (New York City) and the Reverend John P. Healy; the Euthanasia Society of America and Dr. Robert L. Dickinson and Mrs. Robertson Jones; the General Service Administration, National Archives (Washington, D.C.), and F. R. Holdcamper; Lawrence Memorial Hospital (New London, Conn.); the Marine Society of the Port of New York; the Mystic Seaport Museum (Mystic, Conn.) and Malcolm D. McGregor; the National Institute of Arts and Letters; the George M. Cohan Music Publishing Company; the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (New York City); Bellevue Hospital; Norwich (Conn.) State Hospital; Laurel Heights Sanatorium (Shelton, Conn.) and Dr. Kirby S. Howlett, Jr., and Dr. Edward J. Lynch; the New London County Historical Society; d he Players and Pat Carroll; the Episcopal Actors Guild and Mrs. Helen Morrison; the Seaman’s Institute; Sailors Snug Harbor and Arthur Cochrane and Frederick S. McMurray; St. Joseph’s Church and St. Mary’s Cemetery (New London, Conn.); the Stamford Historical Society and Miss M. E. Plumb; the United States Lincs and Richard Harris; the Office of the Town Clerk and the Office of the City Clerk (New London) and Elizabeth T. Roath; Harkness Memorial State Park (Connecticut State Park and Forest Commission, Waterford, Conn.); Mount St. Vincent-on-Hudson and the Sisters of Charity—most particularly, Mother Mary; the College of Mount St. Vincent and Sister Marie Jeanette; De La Salle Institute; the Veterans Administration Hospitals in the Bronx and Manhattan and in Bath, N.Y., and the Probate Court, Salem, Mass.

Special thanks are due to the Gaylord Farm Sanitarium, which provided us with background information. We are grateful to members of its staff—Howard Crockett, Mrs. Reba Maisonville and especially to Dr. Sterling B. Brinkley, its director.

We are indebted to the reference libraries and morgues of various magazines and newspapers for their great help, and also for their permission to quote from specific articles. Many of these articles, too numerous to list here, have been acknowledged in the text. First in our gratitude is The New York Times, the extent of whose assistance is incalculable, and whose files have been drawn upon more than those of any other publication.

We thank, also, the New York Herald Tribune; the New York Journal American; the New London Day and its managing editor, George E. Clapp; the Oakland (California) Tribune and Frank Wootten and Lester Sipes; the Boston Globe and Herbert A. Kenny; the Providence (R.I.) Journal and the Evening Bulletin and I. Talanian; the Lynne (Mass.) Item and V. P. O’Brien; the Oregon Journal; the Salem Evening News and Warren Rockwell; the Oregonian and Amanda Marion; the Seattle Post-Intelligencer; the Seattle Times and Chester Gibbon; Time and Content Peckham; and Variety.

Among the people connected with O’Neill or members of his family, who gave us their hospitality and in other ways extended themselves to make our job easier, were: Winfield Aronberg, Barbara Burton, Dr. and Mrs. Louis Bisch, E. J. Ballantine, Mrs. Claire Bird, Mrs. Fred Boyden, Louis Bergen, Alfred B. C. Batson, Mrs. Chester A. Beckley, Agnes Casey, Professor Bruce Carpenter, Bennett Cerf, Mrs. Benjamin DeCasseres, Jasper Deeter, Eddie Dowling, Dorothy Day, Eben Given and Phyllis Duganne Given, Charles Ellis and Norma Millay Ellis, Waldo Frank, Mrs. Byron S. Fones, Dr. Shirely C. Fisk, Lillian Gish, Mrs. Samuel S. Greene, Mrs. Pete Gross, Dr. and Mrs. Joseph Ganey, Mrs. Clayton Hamilton, John Hewitt, Joe Heidt, Ralph Horton, Mrs. Smith Ely Jelliffe, Edna Kenton, Alexander King, Joseph Wood Krutch, Louis Kalonvme, Manuel Komroff, Ed Keefe, James and Patty Light, Ruth Lander, Armina Marshall Langner, William L. Laurence, Romany Marie, Mrs. W. E. Maxon, Dr. Frederic B. Mayo, Jo Mielziner, George Middleton, Mrs. Beatrice Maher, Philip Moeller, Ward Morehouse, Frank and Elsie Meyer, Joseph A. McCarthy, Elizabeth Murray, Mrs. Matt Moran, Nina Moise, Dudley Nichols, George Jean Nathan, Patricia Neal, Sean O Casey, Dr. Robert Lee Patterson, Florence Reed, Arthur Leonard Ross, Jessica Rippin, Robert Rockmore, Selena Royle Renavent, Paula Strasberg, Mrs. Earl C. Stevens, Lee Simonson, Wilhelmina Stamberger, Bessie Sheridan, Mr. and Mrs. Phil Sheridan, Claire Sherman, Mrs. E. Chappell Sheffield, Mai-mai Sze, Pauline Turkel, Brandon Tynan, Allen and Sarah Ullman, Alice Woods Ullman, Carl Van Vechten and Fania Marinoff Van Vechten, Mary Heaton Vorse, Mrs. Jacob N. Wolodarsky, Charles Webster, Richard Weeks, Francis (Jeff) Wylie, Norman Winston, Mary Welch, Stark Young and William and Marguerite Zorach. We are grateful to them all.

We also thank Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant, whose reminiscences of O’Neill were of great value and who has allowed us to quote from her book, Fire Under the Andes (Alfred A. Knopf); Ilka Chase, who granted permission to quote from Past Imperfect (Doubleday & Company); Mrs. Dudley Nichols, who consented to our use of letters written by her husband; Mrs. Barrett H. Clark, for permission to quote from Eugene O’Neill: The Man and His Plays (Dover Publications); and Mrs. Sherwood Anderson, for her help in locating some of the sources of her husband’s writings.

Others who generously furnished us with information and assistance of various kinds are: Jacob Ben-Ami, Walter Abel, Mr. and Mrs. Egmont Arens, Leslie Austin, Margaret Anglin, Dr. Frank L. Babbott, Frank D. Brewer, Charlotte E. Betts, Mary Bicknell, Pincus Berner, Robert C. Brown, Bessie Breuer, Albert Boni, Elizabeth Brennan, Jeanie Begg, Jennie Belardi, Mark Barron, Charles Burns, Chief of Police (Marblehead, Mass.) Samuel H. Bradish, Frederick Brisson, Mark Crane, Dan D. Coyle, Joseph Corky, Holger Cahill, George Canessa, Mrs. Francis Cadenas, Edith Corwin, Ed Kook, Dr. Saul Colin, Melville Cane, Mrs. Albert B. Carey, Carmen Capalbo, Stanley Chase, Harry T. Crowley, Louis Calta, Frank Conroy, Alexander Campbell, Bosley Crowther, Padraic Colum, Aileen Cramer, Cheryl Crawford, Edward Choate, Arthur Cantor, Gloria Cantor, F. V. Chappell, Alexander H. Cohen, Jack Cunningham, Bernard Clark, Joe Cronin, Warren Carberg, Arthur Daley, Harrison Dowd, Jack Dempsey, Olin Downes, Zelda Dorfman, Thomas F. Dorsey, Jr., Barbara Dubivsky, Lawrence E. Davies, Ruth Dutro, John D. Davies, Milton I. D. Einstein, Manny Eisler, Leon Edel, Max Eastman, Donald Friede, Daniel Foley, Mrs. Hall Furber, Lynn Fontanne, John Fenton, Bijou Fernandez, Robert Flanagan, Mrs. Emily Rippin Griswold, Howard Mortimer Green, Paul Green, Max Gordon, Ruth Gilbert, Louis Gruenberg, Dr. Karl Ragnar Gierow, Edward Goodman, Brother Angelus Gabriel, Mrs. Joseph Girsdansky, Carol Grace, Howard Mortimer Green, Jesse Gordon, David Golding, Margalo Gilmore, Marjorie Griesser, Police Lieutenant (Marblehead, Mass.) G. E. Girard, Dr. Gordon Hislop, A. Arthur Halle, Sam Hick, Mrs. Walter Huston, Sol Hurok, Sonia Levine Hovey, James Hammond, Helen Hayes, Theresa Helburn, Dag Hammarskjold, John Houseman, Mabel Hess, Inez Hogan, Rita Hastings, John Cecil Holm, Granville Hicks, Ann Harding, Robert Hassett, Margaret Heyer, Arthur Hughes, Blanche Hayes, Dr. Daniel Hiebert, Barry Flyams, Don Hartman, Dr. Andrew Harsanyi, Edward Hubler, Catharine Huntington, Louis Isaacs, Dr. Oswald Jones, Bill Johnson, Denis Johnston, Don Janson, Sybil V. Jacobsen, Dr. Robert Klein, Allred Krevmborg, Leon Kramer, Sadie Koenig, Margaret Kaplan, Gilbert Kahn, Theodore Liebier, Jr., Mrs. William L’Engle, Claire Luce, Alfred Lunt, Frank Leslie, Dr. Sidney Lenke, Scott Lindsley, Louise Larabec, T. H. Latimer, J. Anthony Lewis, Gloria Vanderbilt Lumet, Edward Lazarc, David Lawrence, Kyra Markham, Nickolas Moray, Mary Morris, Mrs. Julian Moran, Aline MacMahon, W. Somerset Maugham, Thomas Mitchell, Robert Manning, Marcella Markham, Philip McBride, Mrs. Harold J. McGee, Gilbert Miller, James Meighan, Theodore Mann, Walter Murphy, Mrs. Richard J. Madden, Dr. Merrill Moore, Warren Munsell, Mrs. Mabel Ramage Mix, Bert McCord, Alan D. Mickle, Richard Maney, Sal J. Miraliotta, Edward Morrow, Albert C. Nathanson, Dr. and Mrs. John Norris, Daniel O’Neill, Arnold Newman, Dr. W. Richard Ohler, Clifford Odets, Hal Olver, Henry O’Neill, Dr. B. N. Pennell, Albert J. Perry, Augustus Perry, Joseph Plunkett, Karl Pretshold, Mrs. Percy Palmer, Sevmour Peck, Brother Basil Peters, David F. Perkins, Coddington Pendleton, fudge S. V. Prince, Professor Norman Pearson, Arthur Pell, Dorothy Peterson, Sidney Phillips, Stavros Peterson, Frank Payne, Susan Pinchot, C. N. Pollock, Stephen Philbin, James Francis Quigley, Jose Quintero, George Reynolds, Sawyer Robinson, George Ronkin, George Ross, William Brennan Rogers, Jason Robards, Jr., Jane Rubin, Jay Russell, A. M. Rosenthal, Lennox Robinson, Harold D. Smith, James Shay, Richard Shepard, Mrs. Eunice Saner, Paul Shyrc, Mrs. Henry Bill Selden, Dr. Thomas B. Stoltz, Robert Sisk, Arnault G. Schellenberg, Mrs. John Sloan, Louis Sobol, James Shute, Arthur Shields, Bernard Simon, Oliver M. Sayler, Dr. Daniel Sullivan, Wilbur Daniel Steele, Patrolman (Marblehead, Mass.) John Snow, Mrs. George E. Shay, Dr. Kenneth J. Tillotson, John Tucker, Edna Tyler, Clara A. Weiss, Arthur G. Walter, Richard Witkin, Thornton Wilder, Richard Watts, Jr., Mary Williams, Edmund Wilson, Dr. Sophus Keith Winther, Robert Weller, Ted Williams, Mr. and Mrs. Laurence A. White, Stephen Weissman, Stephen Watts, William Weart, Arthur W. Wisner, Peggy Wood and Sam Zolotow.

In addition to the books previously acknowledged, we are grateful to Random House, Inc., for permission to quote from The Plays of Eugene O’Neill (three volumes) and from The Iceman Cometh by Eugene O’Neill and A Moon for the Misbegotten by Eugene O’Neill. We also thank the Yale University Press for allowing us to quote from Long Day’s Journey Into Night, by Eugene O’Neill, as well as from A Touch of the Poet and Hughie, both by Eugene O’Neill.

We are also indebted to the following sources:

Inscriptions: Eugene O’Neill to Carlotta Monterey O’Neill (Yale University Library); George Pierce Baker and the American Theatre, by Wisner Payne Kinne (Harvard University Press); An Anarchist Woman, by Hutchins Hapgood (Dodd, Mead & Company); The Complete Plays of Eugene O’Neill: Wilderness Edition (Charles Scribner’s Sons); History of the San Francisco Theatre, Volume XX: James O’Neill, by Workers of the Writers’ Program of the WPA of Northern California (sponsored by the city and county of San Francisco); The Theatre of George Jean Nathan, by Isaac Goldberg (Simon and Schuster); The Intimate Notebooks of George Jean Nathan (Alfred A. Knopf); A History of the American Drama from the Civil War to the Present, by Arthur Hobson Quinn (Harper & Brothers); Total Recoil, by Kyle Crichton (Doubleday & Company, Inc.); The Curse of the Misbegotten, by Croswell Bowen with the assistance of Shane O’Neill (McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc.); A Victorian in the Modern World, by Hutchins Hapgood (Harcourt, Brace & Company); Letters of Sherwood Anderson (Little, Brown & Company); George Pierce Baker, A Memorial (Dramatists Play Service); Conversations on Contemporary Drama, by Clayton Hamilton (Macmillan); Anathema! by Benjamin DeCasseres (Gotham Book Mart); A Bibliography of the Works of Eugene O’Neill, by Ralph Sanborn and Barrett H. Clark (Random House, Inc.); A Wayward Quest, by Theresa Helburn (Little, Brown & Company); Time and the Lown, by Mary Heaton Vorse (The Dial Press); Our American Theatre, by Oliver M. Sayler (Brentano’s); Movers and Shakers, by Mabel Dodge Luhan (Harcourt, Brace & Company); Living My Life, by Emma Goldman (Garden City Publishing Company, Inc.); Whatever Goes Lip-—by George C. Tyler and J. C. Furnas (The Bobbs-Merrill Company); John Reed, by Granville Hicks (The Macmillan Company); The Road to the Temple, by Susan Glaspell (Frederick A. Stokes); The Provincetown, by Helen Deutsch and Stella Hanau (Farrar & Rinehart, Inc.); A Research in Marriage, by G. V. Hamilton, M.D. (Lear Publishers, Inc.); These Things Are Mine, by George Middleton (The Macmillan Company); The Stage Is Set, by Lee Simonson (Dover Publications); Representative One-Act Plays by American Authors, selected by Margaret Goodner Mayorga (Little, Brown & Company); Reference Point, by Arthur. Hopkins (Samuel French); Of Time and the River, by Thomas Wolfe (Charles Scribner’s Sons); Nine Plays by Eugene O’Neill—introduction by Joseph Wood Krutch (Random House, Inc.); The American Drama Since 1918, by Joseph Wood Krutch (George Braziller, Inc.); The Gangs of New York, by Herbert Asbury (Alfred A. Knopf); and This Is My Best, edited by Whit Burnett (The Dial Press).

We also acknowledge, with thanks, consent to quote from the following:

“O’Neill Picks America as His Future Workshop,” by Richard Watts, Jr., September 27, 1931; “Exile Made Him Appreciate U.S., O’Neill Admits,” by Ernest K. Lindley, May 22, 1931; “Nathan Admits O’Neill Flouted Advice He Gave,” by Ishbel Ross, March 17, 1931; “Regarding Mr. Eugene O’Neill as a Writer for the Cinema,” by Richard Watts, Jr., March 4, 1928; “Eugene O’Neill Talks of His Own and the Plays of Others” (unsigned), November 16, 1924; “Young Boswell Interviews O’Neill” (unsigned), May 24, 1923; “Eugene O’Neill” (unsigned), November 13, 1921; “Eugene O’Neill at Close Range in Maine,” by David Karsner, August 8, 1926; Poem (“To Be Sung at the O’Neill Play”) in Franklin P. Adams’ column, October, 1931. The foregoing are all by permission of the New York Herald Tribune.

“The Odyssey of Eugene O’Neill,” by Fred Pasley, 1932—by permission of the New York Daily News; “A Eugene O’Neill Miscellany” (unsigned), January 12, 1928, and “The Boulevards After Dark,” by Ward Morehouse, May 14, 1930—by permission of the New York Sun; “O’Neill in Northwest to Get Drama,” by Richard L. Neuberger, November 29, 1936—by permission of the Sunday Oregonian; “The Ordeal of Eugene O’Neill” (cover story), October 21, 1946—by permission of Time; “Softer Tones for Mr. O’Neill’s Portrait,” by Mary Welch, May, 1957, and “Untold Tales of Eugene O’Neill,” by Gladys Hamilton, August, 1956—by permission of Theatre Arts magazine, Miss Welch and Mrs. Hamilton; “The Iceman and the Bridegroom,” by Cyrus Day, March, 1958—by permission of Modern Drama and the author; “The Recluse of Sea Island,” by George Jean Nathan, August, 1935—by permission of Redbook magazine and Mrs. George Jean Nathan.

Permission to quote from the three-part Profile of Eugene O’Neill by Hamilton Basso, February 28, March 6 and March 13, 1948, has been granted by the author and The New Yorker; we thank The New Yorker, also, for permission to quote from reviews and “The Talk of the Town,” and for a verse by Arthur Guiterman. Permission to quote from “Close-up —Eugene O’Neill,” by Tom Prideaux, October 14, 1946, is by courtesy of the author and Life, copyright 1946 Time Inc. Permission to quote from A Weekend with Eugene O’Neill,” by Malcolm Cowley, September 5, 1957, has been granted by the author and The Reporter magazine.

In addition, we would like to acknowledge our appreciation to the following articles and authors:

“Haunted by the Ghost of Monte Cristo,” by Richard H. Little—Chicago Record Herald, February 9, 1908; “Personal Reminiscences,” by James O’Neill—Theatre Magazine, December, 1917; “Nipping the Budding Playwright in the Bud,” by Heywood Broun—Vanity Fair, October, 1919; “Personality Portraits,” by Alta M. Coleman—The Theatre, April, 1920; “Playwright Finds His Inspiration on Lonely Sand Dunes by the Sea,” by Olin Downes—Boston Sunday Post, August 29, 1920; “Enter Eugene O’Neill,” by Pierre Loving—The Bookman, August, 1921; “The Extraordinary Story of Eugene O’Neill,” by Mary B. Mullett—American Magazine, November, 1922; “Making Plays with a Tragic End,” by Malcolm Mollan—Philadelphia Public Ledger, January 22, 1922; “The Real Eugene O’Neill,” by Oliver M. Sayler—The Century Magazine, July, 1922; “What a Sanatorium Did for Eugene O’Neill,” by J. F. O’Neill —Journal of Outdoor Life, June, 1923; “Eugene O’Neill,” by Charles A. Merrill—Boston Globe, July 8, 1923; “Eugene O’Neill—the Inner Man,” by Carol Bird—Theatre Magazine, June, 1924; “Back to the Source of Plays Written by Eugene O’Neill,” by Charles P. Sweeney— New York World, November 9, 1924; “Eugene O’Neill Lifts Curtain on His Early Plays,” by Louis Kalonyme—The New York Times, December 21, 1924; “Fierce Oaths and Blushing Complexes Find No Place in Eugene O’Neill’s Talk,” by Flora Merrill—New York World, July 19, 1925; “Fifteen Year Record of the Class of 1910—Princeton University,” 1925; “I Knew Him When—” by John V. A. Weaver—New York World, February 21, 1926; “Eugene O’Neill, Writer of Synthetic Drama,” by Malcolm Cowley-—Brentano’s Book Chat, Vol. 5, No. 4, July and August, 1926; “Who’s Who on Broadway,” by Homer H. Metz—New York Telegraph, December 25, 1927; “O’Neill Stirs the Gods of the Drama, by H. I. Brock—The New York Times, January 15, 1928; “Celebrities and Some Others,” by Allred Batson—North China Daily News, February 12, 1929; “Out of Provincetown,” by Harry Kemp—Theatre Magazine, April, 1930; “The World’s Worst Reporter, by Robert A. Woodworth—Providence Journal, December 6, 1931; “O’Neill’s House VWs Shrine for Friends,” by Mary Heaton Wise—New York World, January 11, 193!; “O’Neill Is Eager to See Cohan in ‘Ah, Wilderness!’” by Richard Watts, Jr.—New York Herald Tribune, September 9, 1933; “Eugene O’Neill Undramatic Over Honor of Nobel Prize”—Seattle Times, November 12, 1936; “O’Neill Turns West to New Horizons,” by Richard L. Neuberger—The New York Tiwtes, November 22, 1936; “O’Neill Plots a Course for the Drama,” by S. J. Woolf—The New York Times, October 4, 1941; “Eugene O’Neill Discourses on Dramatic Art,” by George Jean Nathan—New York journal American, August 22, 1946; “Eugene O’Neill Returns After Twelve Years,” by S. J. Woolf—The New York Times, September 15, 1946; “O’Neill on the World and ‘The Iceman,’” by John S. Wilson—PM, September 3, 1946; “Playwright Eugene O’Neill Back for Play’s Premiere Says He’ll Roam No More,” by Mark Barron—Associated Press News Feature, October 12, 1946; “Memories of Eugene O’Neill,” by Herbert J. Stoeckel—Hartford Courant Magazine, December 6, 1953; “Shane O’Neill’s hong Journey,” by Helen Dudar—New York Post, February 7, 1957; “Eugene O’Neill— Notes From a Critic’s Diary,” by Stark Young—Harper’s Magazine, June, 1957; “The Bright Face of Tragedy,” by George Jean Nathan— Cosmopolitan, August, 1957; “A Few Memories of Eugene O’Neill,” by Richard Watts, Jr.—New York Post, September 8, 1957.

Also, the following stories and articles by Eugene O’Neill:

“Tomorrow”—The Seven Arts magazine, June, 1917; “A Letter from Eugene O’Neill”—The New York Times, April 11, 1920; “A Letter [from Eugene O’Neill]”—The New York Times, December 16, 1921; “Strindberg and Our Theatre”—Provincetown Playbill, No. 1, Season 1923–24; “Are the Actors to Blame?”—Provincetown Playbill, No. 1, Season 192526; “The ‘Fountain’ Program Note”-—Greenwich Playbill, No. 3, Season 1925–26; “The Playwright Explains”-—The New York Times, February 14, 1926; “Memoranda on Masks—A Dramatist’s Notebook”—The American Spectator, November, 1932; “Second Thoughts”—The American Spectator, December, 1932.

Finally, we thank our editors at Harper for their patience and moral support. If we have inadvertently neglected to thank any of the people who gave us their assistance, we ask their pardon, and offer our gratitude.

Introduction

Since Mr. Gelb and I are associates on the news staff ofThe New York Times, he has told me a good deal about O’Neill during the five years in which Mrs. Gelb and he have been writing it. When they undertook the responsibility of writing it they did not foresee the size it would assume. They had always admired Eugene O’Neill’s plays; they had long regarded him as America’s greatest dramatist; they were fascinated by everything they heard about him from people who had known him. All they intended originally was a biography of conventional length.

But the more they poked into his bizarre personal life, which they saw reflected in the dark mirror of his plays, the more engrossed they became. Everything in his life became significant because everything affected his plays. He was a highly personal writer who proceeded through a succession of obsessions from the wistfully romantic sea plays to the ruthlessness of Long Day’s Journey Into Night.

Eventually Mr. and Mrs. Gelb had to decide whether they were going to write a selective biography or a comprehensive life and study. They decided on the latter. For it became obvious to them that the philosophical life of the dramatist developed out of the experiences and temperaments of his mother and father: that the real sources, in fact, were his emotional and spiritual heritage. The father and mother lived in a spacious theatre that their son helped to destroy. He retained much of the spaciousness of style, but he filled it with bleaker and harsher materials.

Although O’Neill had a charming personality, he was an extremely complex man. Brooding, restless, distrustful, dramatic, he rejected every thing in life that did not bear directly on his writing. Except for his passion for writing, he would probably have drunk himself to an early death, like his hopeless brother. If the term “beatnik” had existed in his youth, he would have been recognized as a perfect example of the rootless, rebellious, dissipated, egotistical, self-pitying renegade. His passion for writing saved him by imposing on him a certain discipline. He chose between dereliction and writing. Even after he had made the choice—more or less deliberately, it appears—he was still “on the lam,” like a fugitive from society. He was forever abandoning what he had in favor of something else he thought he wanted, but never found. His life was a long day’s journey into night.

Those of us who were acquainted with him knew some of this. But his association with the theatre was only a small part of his personal life, and possibly the least significant. The things that mattered most to him and made the deepest impression on him were, invisible, at least to most of us—his boyhood, unsettled because his father and mother were frequently on tour; his years at sea and on the beach; his mad gold expedition in Honduras; his aimless days and nights in Greenwich Village; his hand-to-mouth existence in Provincetown. Also, the romantically gloomy books, plays and poems he read from the nineteenth century when the death wish was a literary fetish. These were the things that mattered most.

Although the rootlessness and isolation of much of O’Neill’s life have set his biographers many problems, Mr. and Mrs. Gelb have tracked him down with the ingenuity and perseverance of police reporters. They have interviewed more than four hundred people who knew one aspect or another of O’Neill’s elusive life. The people who knew him are mortal, like all of us; and people are always the best sources. The printed records confirm only a small part of the facts and impressions that people retain in their memories. Mr. and Mrs. Gelb have been able to relate O’Neill’s life directly to his plays. It is not a pretty life. But it is always absorbing; much of it is astonishing. We are fortunate to have it on the record less than a decade after O’Neill’s death.

Brooks Atkinson

New York, 1961

“Man is born broken, he lives by mending. The grace of God is glue!”

The Great God Brown, Act IV, Scene I

Part 1: Haunting Ghosts 1846—1912

I

In the early summer of 1939 Eugene O’Neill began work on what he called “a play of old sorrow, written in tears and blood.” It was Long Day’s Journey Into Night—a brutal baring of the forces that had shaped him, an evaluation of his tragic viewpoint, an explanation of his failures as a human being, and a celebration of the fact that he had become, in spite of these failures, the consummate artist that he was.

“I love life,” he once said. “But I don’t love life because it is pretty. Prettiness is only clothes-deep. I am a truer lover than that. I love it naked. There is beauty to me even in its ugliness. In fact, I deny the ugliness entirely, for its vices are often nobler than its virtues, and nearly always closer to a revelation.”

O’Neill, at fifty, felt an urgency to embark on the revelations of Long Day’s Journey Into Night, for he knew that the mental and physical stamina that had sustained him throughout twenty-five astoundingly productive years was ebbing. Although he no longer cared about having his plays produced—he had not had anything on Broadway since 1934, when Days Without End had been coolly received-—he did not want to die without leaving a definitive, naked statement of who and what he was.

He was convinced of his own immortality as a dramatist and, while determined to withhold his autobiographical play from the public until twenty-five years after his death, he did want it, ultimately, to take its place in the body of his work. His widow, to whom he left control of all his plays, permitted the script to be published three years after he died; it was immediately recognized as a masterpiece in the United States and abroad.

O’Neill wrote in a dedication of the play that at last he had been able to face his dead. After years of dissecting, analyzing and reconstructing the members of his family and drawing thinly disguised and symbolically heightened portraits of them, he was now prepared to approach them and himself with, as he put it, “deep pity and understanding and forgiveness.”

It is true that he pitied and understood. But the fact that he was impelled, years after their deaths, to reveal his father as a miser, his mother as a narcotics addict, his brother as an alcoholic, indicates that he could not entirely forgive. O’Neill, in his fifties, was still torn by alternating hatred and love for his family.

Friends assumed that he wanted to defer publication of Long Day’s Journey Into Night out of consideration for the feelings of his parents’ surviving relatives, who would have been dead when the play finally emerged. Since O’Neill had little affection for his parents’ kin, however, it is more likely that the purpose of the delay was to prevent his harsh portraits from being disputed (which, as it turned out, they were—and hotly—by friends of O’Neill’s father).

O’Neill was trying to tell an unsuspecting world the truth—if not always the literal truth, at least the artistic truth—about his heritage. He was compelled to go back to his roots, to justify himself, to prove that “the sins of the father are to be laid upon the children.”

“I’m always acutely conscious of the Force behind—(Fate, God, our biological past creating our present, whatever one calls it—Mystery, certainly),” O’Neill had written to the theatre historian and critic Arthur Hobson Quinn, fifteen years before beginning Long Day’s Journey Into Night.

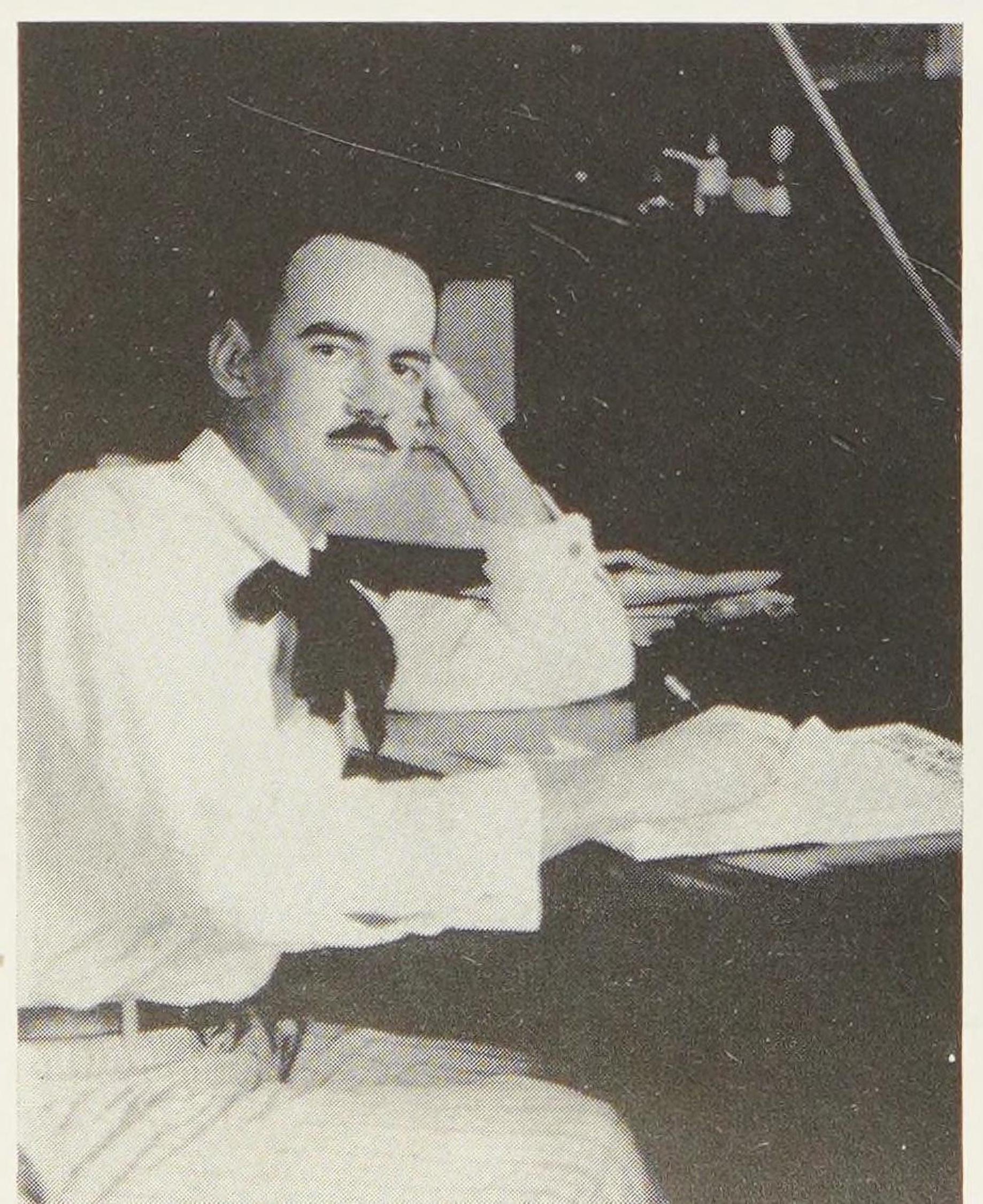

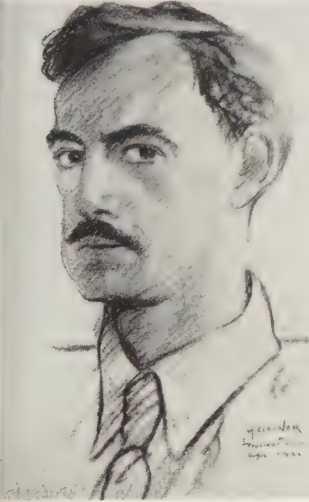

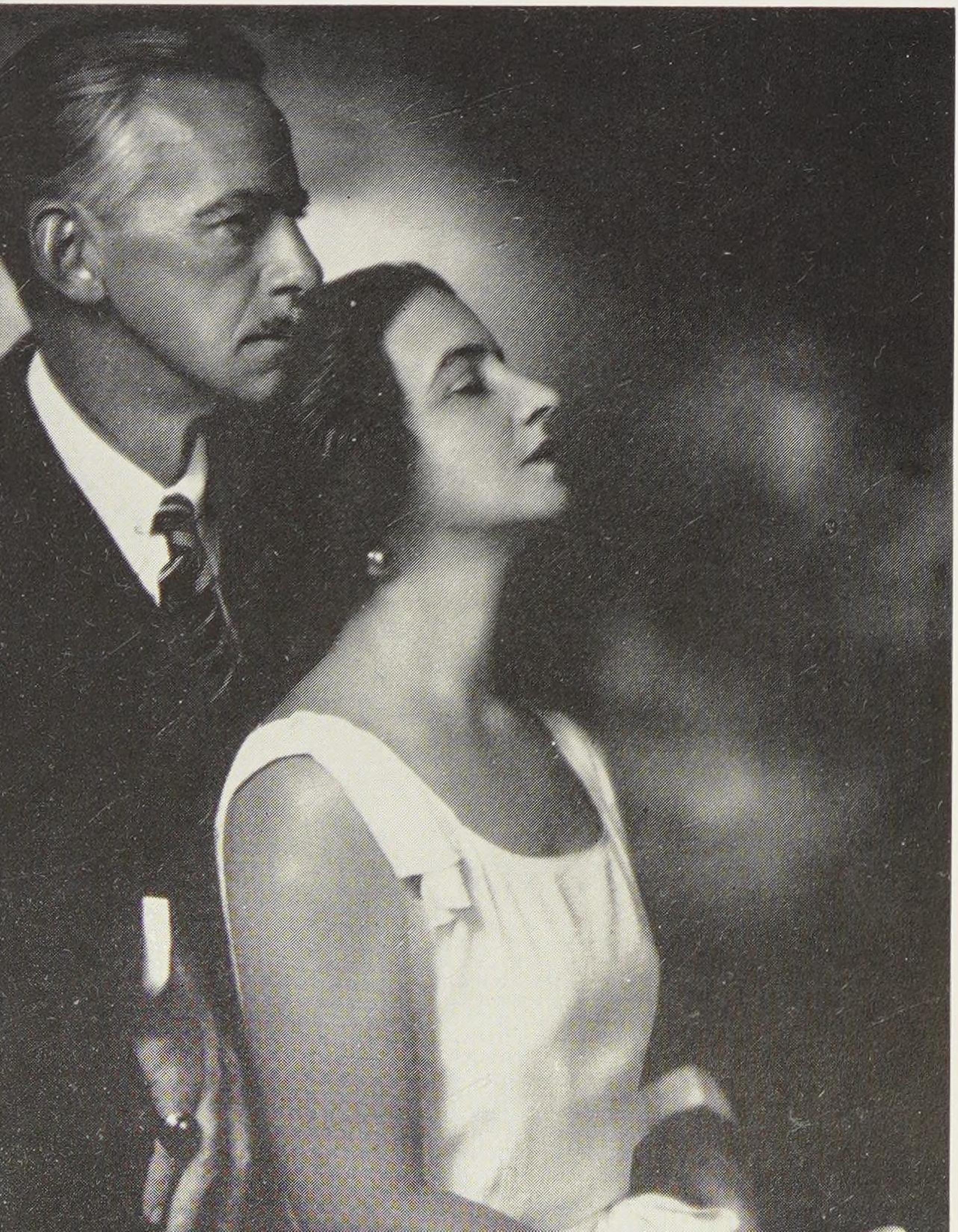

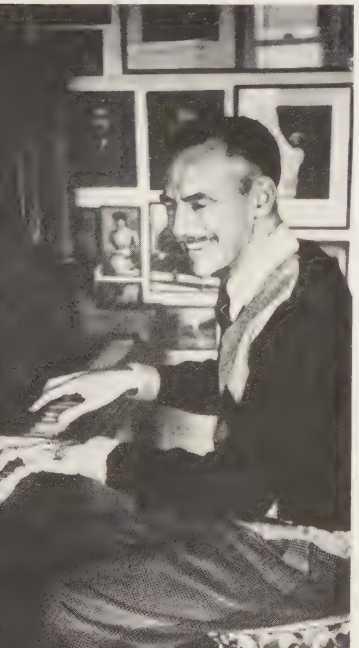

When he started writing the play O’Neill, despite the inroads of a debilitating nervous disorder, was still impressively handsome. His dark hair was streaked with white and there were deeply cut lines about the mouth, at the edges of the eyes, and etched into a lofty forehead. A sparse, gray, triangular mustache roofed a mouth at whose corners lurked the hint of a sardonic smile. The sagging checks could not hide high, strong bones, a firm jaw and a chin chiseled from granite. He smiled rarely, but when he did it was like the sudden lifting of a fog; the fog settled again with the same startling rapidity.

His eyes, always an astonishment to those meeting him for the first time, illuminated his face. Large, dark, immeasurably deep, set wide apart under heavy brows, they could stare into depths that existed for no one else. When he turned the O’Neill look on someone, he appeared to gaze into that person’s soul. But the appraisal was neither critical nor even disconcerting; it was a look of profound and gentle searching, at once penetrating and reassuring. For nothing shocked him. He was interested only in the motive behind the action.

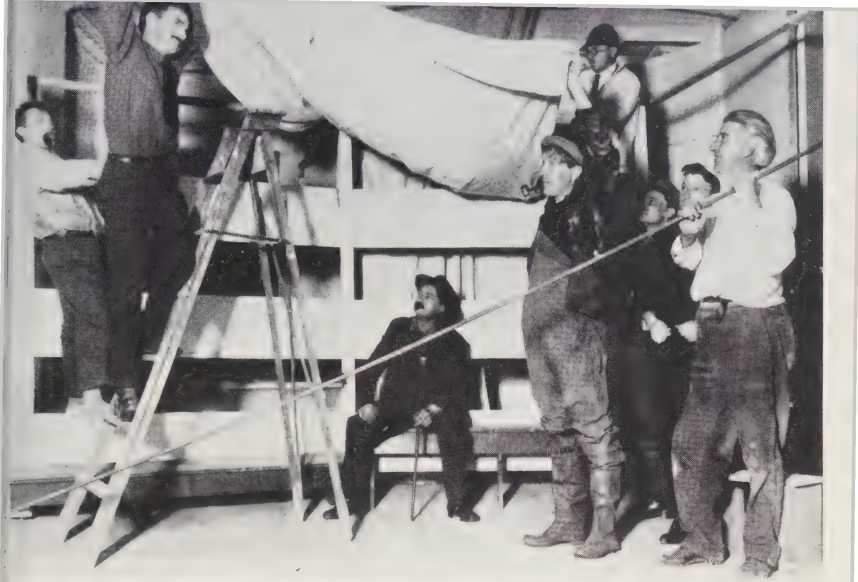

O’Neill, aged fifty, was regarded as the most distinguished dramatist the United States had ever fostered. Since 1916, when a group of passionate young writers, actors and artists in Provincetown, Massachusetts, presented his one-act play, Bound East for Cardiff, he had made a staggering contribution to the American theatre, and had become, except for Shakespeare and possibly Shaw, the world’s most widely translated and produced dramatist.

For over a quarter of a century he had battled to lift American drama to the level of art and keep it there, to mold a native, tragic stage literature. The first American to succeed as a writer of theatre tragedy, he had continued shattering Broadway convention and made possible the evolution of an adult theatre in which such playwrights as Thornton Wilder, Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller could function.

To O’Neill tragedy had the meaning the Greeks gave it, and it was their classic example that he tried to follow. He believed with the Greeks that tragedy always brought exaltation, “an urge toward life and ever more life”; the spectacle of a performed tragedy roused men to “spiritual understandings and released them from the petty greeds of everyday existence.” Tragedy ennobled in art what O’Neill often referred to as man’s “hopeless hopes.” Any victory man might wring from life was an ironic one, O’Neill believed. His viewpoint was that “life in itself was nothing.” It was only the dream that kept man “fighting, willing—living.”

“To me, the tragic alone has that significant beauty which is truth,” O’Neill said in 1921, not long after the premiere of Beyond the Horizon, his initial Broadway production and the first of four O’Neill plays to win the Pulitzer Prize. “It is the meaning of life—and the hope. The noblest is eternally the most tragic. The people who succeed and do not push on to a greater failure are the spiritual middle-classes. Their stopping at success is the proof of their compromising insignificance. How petty their dreams must have been!”

In 1939 O’Neill’s dream still soared. Despite the fact that he had won the Nobel Prize for literature three years before, he did not think he had yet pushed on to a great enough failure. Although he already had thirty-four published plays to his credit, including the thirteen-act trilogy, Mourning Becomes Electra, and had completed the as yet unproduced and unpublished The Iceman Cometh, he had set his “hopeless hope on finishing a Herculean cycle of eleven plays. 7 he cycle, on which he had been working intermittently for about five years, was to span a period of more than 175 years in the history of an American family doomed to what O’Neill characterized as “self-dispossession,” or the bartering of their souls for material gain.

But ill health had forced him to ponder the shelving of his taxing project. Toward the end of 1937 he began to suffer from an illness diagnosed at first as Parkinson’s disease and later as a rarer disease, whose nature could not be completely ascertained but which most specialists considered degenerative.

The obscure disorder causes a gradual breakdown of brain cells and results in a lack of co-ordination between nerves and muscles. The sufferer loses the ability to control arms, legs and even tongue and throat, while retaining his mental clarity. He reaches for a sheet of paper and instead of grasping it his hand flies upward; he tries to walk forward, and instead he stumbles backward; he clears his throat to speak and with his tongue cleaving to his palate his voice emerges as a croak, his words unformed.

In O’Neill’s case these things did not happen always or all at once. He never knew, though, when or how he was to be frustrated. His symptoms varied in their intensity; some of his doctors believed that psychological causes governed the form of his affliction.

By 1939 palsy was seriously affecting his hands. Even as a young man his hands had trembled slightly, a trait he believed he had inherited from his mother. Now the trembling made it difficult for him to write. To help control the shaking and conserve energy, he formed smaller letters, and his calligraphy became increasingly cramped. Eventually he was squeezing a thousand words onto a sheet of paper the size most people fill with two hundred. Much of his work had to be deciphered under a magnifying glass. He could not set down a creative thought except in his own hand. It was impossible for him to dictate or to use a typewriter.

Thus handicapped, O’Neill turned to work he considered more pressing than the cycle. “I felt a sudden necessity to write plays I’d wanted to write for a long time that I knew could be finished,” he wrote to a friend.

On a Tuesday, June 21, 1939, O’Neill’s wife, Carlotta, made the following entry in her diary: “Gene talks to me for hours—about a play (in his mind) of his mother, father, his brother and himself.... A hot, sleepless night—an ache in our hearts for things we can’t escape!” She was referring to the imminence of World War II.

It took O’Neill a little over two years to complete Long Day’s Journey Into blight. He worked every morning, many afternoons, and sometimes evenings as well. Often he wept as he wrote. He slept badly, and occasionally in the night he rose from the converted Chinese opium couch that served as his bed to go to his wife’s room and talk of the play and of his anguish.

“He explained to me that he had to write the play,” his wife once said.

He had to write it because it was a thing that haunted him and he had to forgive his family and himself.”

He was living at the time on a 158-acre estate, in a concrete-block house built on the side of a mountain, about thirty-five miles from San Francisco.

The house was staffed, until the war, by efficient servants. O’Neill saw scarcely anyone except his wife, whose job it was to maintain an atmosphere conducive to work.

“Orders were that nobody was to go near him,” she later recalled, “not even if the house was on fire. He was never to be disturbed.”

O’Neill arose daily at 7:30, dressed, had breakfast on a tray in his bedroom, and then shut himself into his study to work until 1 p.m.

“He would come out of his study looking gaunt, his eyes red from weeping,” Mrs. O’Neill continued. “Sometimes he looked ten years older than when he went in in the morning. For a while he tried to have lunch downstairs with me. But it was very bad, because he would sit there and I knew his whole mind was on his play—acts, lines, ideas— and he couldn’t talk. I would have to sit there perfectly dumb. I didn’t even want to make a sound with the chair that might disturb him. It made me very nervous and it made him nervous seeing me sitting there like that. We decided it would be best for him to have his lunch on a tray, alone.”

After lunch O’Neill would lie down for a rest, unless he was at a point in his work where he felt he had to go on a bit longer. But he napped sometime during the afternoon and if the weather was mild he swam in his pool, which, being high over the valley, had an oddly soothing effect on him. Later in the day he and his wife would walk about on their grounds and look in on the chickens O’Neill was keeping as a hobby. He sometimes went back to work until dinner.

In the evenings the O’Neill’s usually sat before their huge fireplace. O’Neill enjoyed reading Yeats aloud, while his Dalmatian lay at his feet.

“If he felt gay, he would act something out,” his wife has said. “He was very charming; he could be the worst ham you ever met. But if he was sick, he would be silent and just sit and think. Sometimes, he wouldn’t talk all day long.”

When the play was completed in the summer of 1941, O’Neill told his wife, “Well, thank God, that’s finished.” All but spent from the effort, he was able to write only one more play before his death in 1953— A Moon for the Misbegotten (completed in 1943), which is principally about his brother and is in a sense a sequel to Long Day’s Journey Into Night.

O’Neill presented Carlotta with the original manuscript of Long Day’s Journey Into Night on July 22, 1941, their twelfth wedding anniversary. In his inscription he declared that it had been her love that had enabled him to face his dead and write about “the four haunted Tyrones.”

O’Neill had chosen Tyrone to designate his surname because, steeped as he was in Gaelic history and intensely proud of his undiluted Irish blood, he knew the name was derived from Tir-eoghain, meaning the land of Owen. Owen, who died in A.D. 465, was the ancestor of the O’Neill’s who for centuries ruled over a section of Ulster, including the part that later became County Tyrone.

O’Neill did not bother to disguise the given names of his father and brother—James and James Jr.—but he called himself Edmund, which was the name of a brother who had died in infancy. And he called his mother, whom everyone had known as Ella Quinlan O’Neill, Mary Cavan Tyrone (Cavan also being the name of a county in Ulster).

Their story was, indeed, born of tears and blood and was the key to O’Neill’s tragic outlook in life and art.

II

Both James O’Neill and Ella Quinlan came from Irish Catholic families that had immigrated in the frontier days to bustling cities in Ohio. But that was all they had in common. James, dashing and handsome, and Ella, shy and pretty, fell in love before realizing that their outlooks clashed. Though jealously possessive, they were temperamentally unsuited. Like the warring protagonists in the plays their son was to write, James and Ella became victims of a destructive incompatibility.

Ella was the pampered daughter of a middle-class family, which provided her with a reasonable amount of culture and a higher education. She leaned toward a mystic view of life, was reserved, a little spoiled, romantic and innocent. It was difficult for her to make friends; her shyness was often misconstrued as hauteur and tended to put people off.

James was an actor with no formal schooling, who had fought his way up from poverty. He was gregarious, adaptable, materialistic, secure in his Catholicism and, although self-centered, endowed with a charm that made him universally loved.

Ella could never forgive James for exposing her to his rough-and-tumble world; and he could not forgive her for the pride with which she held aloof from that world. Yet each satisfied in the other a perverse need to torment and pardon. They could express their love only in cycles of punishment and reconciliation. The untranquil climate of their marriage is the theme of Long Day’s journey Into Night. That play lays open the wounds of their marriage, hammering at the accusations and guilty withdrawals and pitiful, abortive attempts at mutual understanding, insisting with nerve-racking emphasis on the quality and quantity of their pain.

James and Mary Tyrone, the play’s middle-aged couple who stand for O’Neill’s parents, are shown to be at once deeply in love and irrevocably embattled; Mary still dwells on the fact that she has married beneath her, out of helpless passion. Her frustration has driven her, long since, to narcotics addiction. She talks in self-pitying monologues. She has tried to understand James’s ambition and his terror at being unable to rise to and stay at the top, but she cannot excuse the effect it has had on her.

James, for his part, adores her, but writhes under her withdrawal and contempt. He has had to resign himself to caring for her as one would a child and salvaging the crumbs of their life.

Eugene O’Neill described the same kind of relationship in a much earlier play, in which the protagonists are frankly designated as Ella and Jim. In it Ella and Jim, both in their twenties, marry out of desperation. Each needs and clings to the other, though neither can give the other happiness or even peace. Ella considers herself Jim’s superior by birth and background and Jim is forced to concede her superiority. Ella resents Jim’s unrelenting fight to overcome his environment; she is furious at being dependent on him; and she is incapable of accepting his selfsacrifice and devotion to her. Jim cannot follow her behind the locked door of her disillusionment.

Jim and Ella literally drive each other insane but they do not let go. In the end Ella is reduced to a childlike state in which she talks to herself madly; Jim’s hope of rising above the petty cruelties of life is crushed, and he resigns himself to being Ella’s nurse.

“I can’t leave her. She can’t leave me,” says Jim to his sister, who has asked why they don’t separate. “And there’s a million little reasons combining to make one big reason why we can’t. For her sake—if it’d do her any good—I’d go—I’d leave—I’d do anything—because I love her ... but that’d only make matters worse for her. I’m all she’s got in the world! Yes, that isn’t bragging or fooling myself. I know that for a fact! Don’t you know it’s true?”

It was a truth O’Neill understood and could hammer home. He did not bother, in this play, to disguise the true names of his parents for two reasons. The first was that they were both recently dead. The other was that Jim was a Negro and the play, on the surface, seemed to be a study of miscegenation, which no one could dream of relating to O’Neill’s own family. The play was All God’s Chilian Got Wings, written in 1923.

O’Neill never stopped writing of his mother and father. He always portrayed them as lovers communicating in code, neither ever able to find the other’s key. Always alive to the intangible gap between his parents, he stated over and over in his plays the theme of man’s tragic inability to reach his fellow man. One of the most heartfelt expressions of this theme is voiced by the hero of The Great God Brown, also written a few years after the death of his parents. In a scene O’Neill selected to represent the work he considered one of his “most interesting and moving, Dion Anthony, the hero he modeled largely on himself, mourns his parents:

“What aliens we were to each other! When [my father] lay dead, his face looked so familiar that I wondered where I had met that man before. Only at the second of my conception. After that, we grew hostile with concealed shame. And my mother? I remember a sweet, strange girl, with affectionate, bewildered eyes as if God had locked her in a dark closet without any explanation.”

Eugene O’Neill’s conception of his mother as a girl locked in a dark closet was influenced by The Spook Sonata, a play by August Strindberg, one of O’Neill’s early literary heroes. In that terrifying drama a woman referred to as the Mummy actually lives in a closet and talks to her family like a parrot. Shortly after his mother’s death O’Neill informed a close friend that she had lived in a room from which she had seldom ventured— that, in a way, she was like the Mummy.

Ella revealed herself to no one outside of her immediate family. Among the hundreds of friends and business associates with whom her husband brought her into contact—even among her relatives who spent summer after summer in the harbor resort of New London, Connecticut, where she and James had their only permanent home—there was no one who could say he really knew her. Relatives who survived her did not even know her actual given name; she had been christened Mary Ellen and was called by that name throughout her childhood.

At fifteen, when she went to boarding school, she dropped the Mary and became Ellen, a name she considered more glamorous. She remained Ellen to the time of her marriage (as indicated by her school records and marriage certificate). Some time after her marriage she assumed the name Ella, which she used on all later legal documents, including her will; that is the name engraved on her tombstone in New London.

It appears then that O’Neill used his mother’s actual given name in Long Day’s Journey Into Night, just as he used the real names of his father and brother. But he may not have done so in this case for the sake of biographical accuracy. For if he had wanted to identify Ella as unequivocally as he did his father and brother he would have used her adopted name, by which everyone, including her relatives, knew her. Psychiatrists to whom the point has been raised consider it likely that O’Neill tried to link his mother to the Virgin Mary, to stress symbolically her frustrated desire to have been a nun rather than a wife and mother. He was acutely conscious of his mother’s conflict between the pure religious life that half-called her and the worldly one she led with her husband, but with which she could not come to terms.

Ella was born on Grand Avenue in New Haven, Connecticut, on August 13, 1857, at the height of a national financial panic. She was the daughter of Thomas Joseph and Bridget Lundigan Quinlan, who had both come from Ireland.

When Ella was born, her father was in his early thirties and her mother in her late twenties. Quinlan had established himself as a general storekeeper but he found the going difficult. Soon after the birth of his daughter he moved his family, which also included a son, William, to Ohio.

The Quinlans, like many immigrant Irish streaming into Ohio on their way west in pursuit of gold, were attracted by Cleveland. Although it was still reeling from the effects of a state-wide wave of bank failures, Cleveland seemed to offer more immediate opportunities than far-off California, for it was a beautiful lake port city and promised quick financial recovery. It had been joined only a few years before by railroad to Cincinnati, then the biggest city in the Midwest.

In Cleveland, Thomas Quinlan became a news dealer, and with the business boom provided by the Civil War he began to thrive. By 1867, when Ella was ten, Quinlan’s business had expanded into a retail shop dealing in books, stationery, “fancy goods,” bread, cakes and candies. The Quinlan family had reached respectable middle-class status. Quinlan accumulated a private library; he also bought a grand piano on which Ella, who showed an aptitude for music, was urged to take lessons. By the time Ella was thirteen, he had switched to the retail liquor and tobacco business and moved into a comfortable house in a good neighborhood.

During the next few years, through judicious investment in real estate and increased patronage of his shop, Quinlan became a man of substance. He brought up his children with all the cultural advantages that a prosperous businessman and a devoted father could provide. Holding firm convictions about his children’s education, he encouraged his daughter to think she might eventually earn a living through playing and teaching piano. But he let his children know he was going to provide for them in his will, and gave Ella to understand that any independence she might achieve by mastery of the piano was to be a matter of moral satisfaction rather than financial necessity.

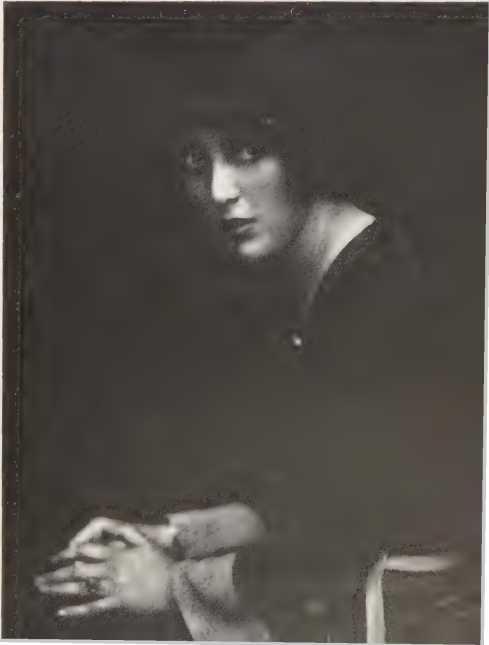

His plans for her must have been colored somewhat by wishful thinking, for Ella was not suited temperamentally to making her own way in life. No trace of the rugged adaptability that had brought her parents from Ireland could be found in her pliant personality or in her delicate features. Tall for her generation—about five feet six inches—and slender, she had a pale, smooth skin, large, dark-brown eyes, a wide, tremulous mouth, a high forehead, and long hair that was to change gradually from reddish to dark brown and which she often wore knotted at the back of her head. She had a quick, shy laugh, and a low-pitched voice.

Ella seemed best suited to take her place in Cleveland’s well-bred society, probably as the wife of a dependable businessman like her own father. In addition to studying the piano she read the classics from her father’s library and, at intervals, was taken by her father to the theatre. Like her friends, she was infatuated with the stock-company actors— and was thrilled by the passionate declamations of the great touring stars.

In September of 1872, when she was fifteen, she was sent to the convent of St. Mary, at Notre Dame in Indiana. Only very well-off families provided their daughters with a higher education, but Quinlan was prepared to give both his children every advantage. To ensure his plans for them he outlined his wishes in an explicit will less than two months after Ella left for the convent.

After bequeathing to his wife all his real and personal property (on condition that she remain unmarried “during the period of her natural life”), he reminded his children of his hopes for them by leaving to William his “Library of Printed Books” and to Mary Ellen his “One Piano Forte.” (After her marriage, she moved this heirloom to her house in New London. It figures as an important off-stage prop in Long Day’s Journey Into Night.)

Quinlan provided for his children in the event of his wife’s remarriage, and took further pains to secure their future in a codicil to his will, which reflected a certain lack of confidence in his wife:

“I devise that my children ... while they are living with my wife ... and before either of them shall attain their majority, that they each of them shall receive at the hands of my wile the same opportunities for education and self improvement, and be supported and clothed and treated as my wife knows and believes they would be treated by me and are treated by me now.”

Quinlan concluded with a vigorous admonition:

“I also expect of and require from my children ... that they each of them shall use the talents which they possess and the education which they may acquire to earn for themselves when they arrive at an age proper for them to do so an honest, honorable and independent livelihood, not relying upon their mother nor upon such share of the property as may descend to each after her demise nor before then.”

Ella, who adored her father and was more attached to him than to her mother, gave every indication of living up to his wishes. She settled down at the convent, situated-near the campus of Notre Dame, a boys’ school that later became the university. St. Mary’s was not at that time an accredited college. It did, however, offer instruction at the college level and since no American university of the period would admit women to its liberal arts courses, St. Mary’s was popular not only among Catholics but also among Protestant and Jewish families. For her day and background, Ella was exposed to a cultural cross section.

Her studies, in addition to church history, dogma and catechism, included English, ethics, rhetoric, philosophy, astronomy, French, and courses in the theory and composition of music, as well as piano technique. In Long Day’s Journey Into Night Mary Tyrone’s contention that she could have been a successful pianist is sneered at by her husband: “The piano playing and her dream of becoming a concert pianist. That was put in her head by the nuns flattering her. She was their pet. They loved her for being so devout. They’re innocent women ... when it comes to the world....”

Actually the nun who taught Ella piano was far from being the unworldly woman James imagined her. Her name (mentioned in Long Day’s Journey Into Night) was Mother Elizabeth. A convert, Mother Elizabeth did not join the Sisters of the Holy Cross until alter she became a widow. Born in England, she was descended from Dr. George Arnold, who had been organist at Winchester Cathedral under Queen Elizabeth; she was educated in Europe, was herself a fine pianist and was worldly enough to set the foundation, in 1850, for a music department at St. Mary’s that was still adhered to by the college more than a hundred years later.

In Mother Elizabeth’s judgment Ella was exceedingly talented. Mother Elizabeth also was astute enough to recognize in Ella a tendency toward self dramatization. W hen Ella, who had evinced a strong interest in religion, spoke of wishing to become a nun, Mother Elizabeth knew this was more a romantic daydream than a serious intention and she hurt Ella’s feelings by advising her to postpone her decision. Mother Elizabeth’s intuition proved sound, for Ella was married just two years after her graduation from St. Mary’s.

One of her schoolmates, Ella Nirdlinger, often spoke of her as a beautiful and pious girl to her son, George Jean Nathan, who later became one of the first drama critics to recognize Eugene O’Neill’s talent. Another of Ella’s classmates was Loretta Ritchie, of Pinckneyville, Illinois, who kept up a casual correspondence with Ella for many years. Ella wrote Loretta of bringing up her children in hotels and sometimes cradling them, as infants, in dresser drawers. Neither Loretta Ritchie nor Ella Nirdlinger snubbed Ella Quinlan when she married, although Ella’s literary counterpart, Mary Tyrone, sadly recollects in Long Day’s Journey Into Night, that after her marriage to an actor “all my old friends either pitied me or cut me dead.”

In June, 1875, when Ella was eighteen, she was graduated with honors in music. She received a gold medal engraved with her name and garnered honors for politeness, neatness, order, amiability, and correct observance of the academic rules.

Although Long Day’s Journey Into Night is biographically accurate in regard to most of the minutiae concerning Ella and James, a mystifying lapse occurs in connection with the description of their first meeting.

Eugene O’Neill has made it appear in the play that Ella was introduced to James by her father during the spring vacation of her senior year at St. Mary’s, in 1876. Ella was actually in her senior year in 1875, but this error of a year is less noteworthy than the fact that Ella’s father had died before the end of 1874. More interesting is the reference in the play to Quinlan’s participation in his daughter’s wedding plans, particularly the mention of his purchase of an elaborate wedding dress for her, when, in fact, the wedding took place more than three years after his death. O’Neill deliberately altered the facts to heighten Ella’s tragedy. She becomes a more poignant victim when she is thrust into James’s harum-scarum theatrical world directly from the sheltering home of her father.

But while O’Neill took license with these details, it is true that Ella’s father did become acquainted with James O’Neill in 1871 or 1872. James, at that time, was the leading man at Cleveland’s celebrated theatre, the Academy of Music. Quinlan’s shop on Superior Avenue was just a block and a half from the theatre, which stood between Superior and St. Clair avenues, in the heart of Cleveland’s business district.

Members of the acting troupe visited the shop and it was there that Quinlan and James struck up an acquaintance based on their common Irish ancestry. It was the custom for leading businessmen of the community to befriend actors of prominence; many of the touring stars, who were products of stock companies, could boast of friends in every town on their itinerary; this often made their travels more pleasant, for their local friends could be counted on to wine, dine and even house them during their engagements.

Ella, as a girl of fifteen, met James, who was then twenty-six, in her father’s home and developed a schoolgirl’s crush on him. But Ella enrolled in the convent in the fall of 1872, about the same time that James left Cleveland for McVicker’s Stock Company in Chicago. While Ella may have dreamed of James and talked to her friends about him, and even imagined herself his wife (when she was not imagining herself a nun), James did not give her a serious thought at that time. During the next three or four years, which he spent in Chicago and San Francisco, James was conducting a fairly hectic love life; it was not until he came to New York in 1876 that he again met Ella—and this time decided he had found his true love.

Their courtship had come about after Ella had spent some months in Cleveland following her graduation and decided that life was pallid there without her father’s stimulating presence. She reminded her mother of his wishes, and Bridget agreed to take Ella to New York, where she had relatives, and to let her enroll for advanced studies in music.

Mother and daughter arrived there early in 1876; substantial checks drawn on Quinlan’s estate followed them periodically. When James reached New York to fill an acting engagement in the fall of 1876, Ella persuaded a male relative of Bridget’s to take her to see him backstage, using James’s former acquaintance with her father as an excuse. She had not forgotten her schoolgirl daydreams, and was already half in love with him.

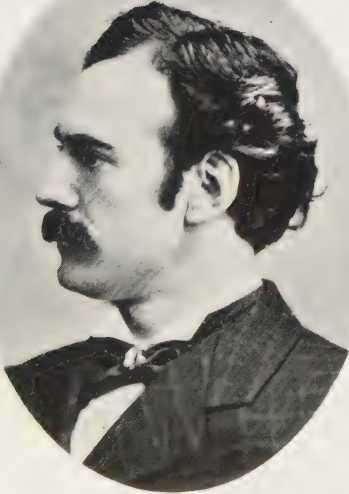

III

James O’Neill, at thirty, was an irresistibly romantic figure. While he was not much taller than Ella—he sometimes wore high-heeled boots on stage to increase his five feet eight inches—-he had a compact, well-balanced figure, graceful carriage and nobility of bearing that more than compensated for his lack of physical stature. His hair was black and curled over a high forehead; his eyes were melting and almost as dark as Ella’s, but they looked at the world more candidly and could burn with passion. His nose and chin followed classically chiseled lines; his even, white teeth gleamed against a dark complexion, and his lilting voice was a caress. In contrast to Ella’s shyness, James’s manner was open and sunny. He was a tireless and effective raconteur.

Although James was self-conscious about his lack of formal education, the life he had led made him far more worldly and sophisticated than Ella. He had the easy confidence of a man who knew he could charm the birds out of the trees.

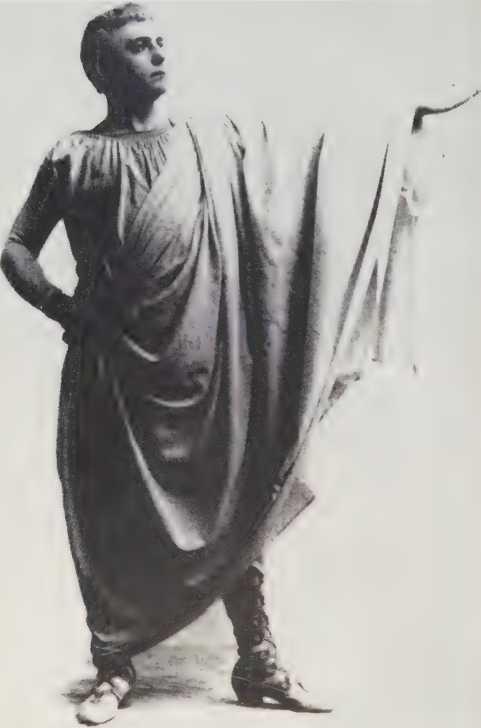

On the stage he added to his natural endowments (aside from high heels) a swashbuckling manner, heroic gestures and a carefully acquired skill with a rapier. These characteristics were perfectly suited to the extravagant melodramas of the era and to the virtuoso recitals of Shakespearean roles for which the public had an endless appetite.

In addition, James had already begun to develop the controlled, melodious voice that could penetrate to the gallery of the huge theatres in which he played. He jokingly referred to his voice as “my organ.” He had taught himself the trick of increasing its volume while actually raising it only two or three notes in pitch. In this way he was able to convey fiery emotion without shouting, which set him apart from the stock actors who resorted to ranting.

In 1876 there seemed to be no question that James would rise to the top of his profession. In theatre circles it was predicted that he might succeed Edwin Booth, who was fourteen years his senior. Booth, one of the three American actors who achieved international lame during the nineteenth century (the others were Edwin Forrest and Joseph Jefferson), was considered by many to be the greatest actor of his era.

Beneath the personal warmth that attracted people to James lay a ruthlessness that often characterizes the successful actor. He possessed the slightly inhuman capacity to sweep aside any involvement that might hinder the pursuit of his art. His artistic temperament told him, without his having to analyze it, that if he did not put the advancement of his career before any other consideration he would founder.

As an actor, James belonged first to his profession, and spent himself completely on his audience. But while there was a certain glory in this dedication and an intoxication in the mass worship he inspired, there was also an emptiness. James tried to fill it by drinking. He always kept a bottle in his dressing room and sometimes drained it in a day. He carried his whiskey well, however, and rarely showed signs of its effect, except for a brilliant sparkle in his eyes. Certainly it did not hurt his acting nor did it in any way hinder his career.

The theatre of the day, in which James had been steadily rising for the past seven years, was a national institution that approximated in popularity the motion-picture industry during the 1930’s and 1940’s. There was scarcely a city that did not support its own resident stock company, with the larger cities supporting two or more. The local companies created their own favorites and in such cities as New York, San Francisco and Chicago it was possible for individual stock company actors to gain enormous local popularity without necessarily attaining national prominence. When famous touring stars visited these cities, the major stock players dropped temporarily into supporting roles.

In an era when leading players in stock companies ruled the public emotions in the same way that movie heroes later would, James O’Neill was sighed over and dreamed about. A Chicago newspaper writer once recalled, in a typical article about him: “Chicago adored James O’Neill. Girls built romances about his private life, some with substantial foundation.... One was that the leading lady of McVicker’s Stock Company was hopelessly in love with the dashing James and that it grieved him sore not to be able to return her purple passion. Droves of girls went every week just to see the heroine droop and wilt when Jimmy kissed her.”

James was a boon to stock company managers, whose prime concern was to elicit waves of emotion from their audiences. Audience response was then a much more tangible quality than it is in today’s relatively polite and intimate theatre, and managers went to considerable pains to measure it. Sometimes a manager would sit in an upper box and face the audience during initial performances of a play, to test the potency of the “shock waves” passing from viewer to stage. The play would be doctored on the basis of those waves. If all went well, bursts of applause and cheers would be spontaneously wrung at frequent intervals from the playgoers, who became almost painfully involved in the emotions of the actors and did not wait to applaud politely at the lowering of the curtain. The applause after a scene was occasionally so prolonged that the stars had to acknowledge it by taking bows between acts.

The impact of James’s personality and reputation on Ella was devastating. She was hypnotized by the glamour and magic that surrounded him.

Her mother, however, was not overjoyed by the prospect of having James for a son-in-law. The fact that it was Thomas Quinlan who had first introduced James to Ella did not help Bridget feel resigned, even though James seemed to be an upright Irishman and a good Catholic. While it was considered permissible for fashionable families to lionize a prominent actor, a member of the theatrical profession was not held to be a sound matrimonial prospect for a cherished daughter. Even the best of actors led nomadic lives and were subject to financial hazards, and a number of them were known to be philanderers and heavy drinkers. Scandals in their private and professional lives were followed with shivering pleasure in the newspapers. First-class hotels would seldom accommodate actors because of their habit of jumping their rent when, as often happened, their shows closed unexpectedly and left them stranded and unpaid.

Bridget recognized the fact, which Ella ignored, that a sheltered upbringing and refined taste were not adequate equipment for an actor’s wife; actors traveled from town to town, often under primitive conditions; and Ella could hardly find herself at home among the rugged troupers who were James’s friends and formed almost his whole world. It was not the sort of life that either Bridget or her husband had envisioned for their daughter, and she pointed this out to Ella. But Ella was carried away by the idea of being the wife of James O’Neill and, summoning an uncharacteristic tenacity and resolution, she determined to marry him.

As for James, nothing at this point in his life seemed impossible. He was as determined as Ella to marry and was as confident as she that within a short time he would stand in the front rank of his profession. That he could have deluded himself into believing Ella would make him a suitable wife or a reasonably happy one is even harder to understand than Ella’s blind confidence. He was under no romantic illusions about the discomforts of touring and he was certainly aware that Ella could not adapt cheerfully to the wandering life of an actor.

Perhaps the fact that, by the social standards of the day, she was unattainable made the conquest seem sweeter to his ambitious nature. Marrying Ella represented another break with his squalid background. And unquestionably he was captivated by her beauty and innocence, to a point where rational planning became difficult. There was also the incentive of Ella’s financial independence; it was not, perhaps, a major factor, but it could help smooth their way.

With the promise of a brilliant future and the conquest of Ella’s heart, James had grown a long way from the shabby boy with the thick Kilkenny brogue who had landed with his parents in America early in 1856. His family were what F. Scott Fitzgerald, speaking of his own forebears, once described as “strictly potato-famine Irish,” but James would never have acknowledged this fact publicly. In a loquacious and mellow mood, three years before his death in 1920, he gave a lyrical account of his beginnings:

“It was Kilkenny—smiling Kilkenny ... where I was born one opaltinted day in October, 1847.” (His son Eugene, many years later, pointed out that “like all actors, he cut his age for publication.” Actually, he was born October 14, 1846.)

“I beg leave to think,” James continued, “that were I permitted to choose a birthplace for any Irishman’s child, be he dreamy-eyed son of Erin with star fire in his heart or laughing gossoon with song on his lip and roguery in his eye, ’twould be that same little town in old Leinster.”

James was nine, the fourth of six children (three boys and three girls), when his father, Edward, a struggling farmer, and his mother, Mary, arrived at Buffalo in upstate New York. James had outgrown his “skirties,” but his younger siblings were still wearing the red flannel garments in which Irish peasant women dressed their children, to prevent them from being abducted by malevolent fairies.

Like the Quinlans, the O’Neill’s soon left their first landing place and pushed west to Ohio. It was in the same year that the Quinlans arrived in Cleveland—1857—that the O’Neill’s settled in Cincinnati, about a four-hour train ride away. Unlike the Quinlans, however, the O’Neill’s did not prosper, although Cincinnati was then the undisputed industrial center of the West. Edward O’Neill was a mystic; soon after his arrival, in response to an ethereal summons from his Celtic ancestors, who warned him of his impending death, he abandoned his family and returned to Ireland, where he died a short time later.

The two older brothers left home (one later joined an Ohio regiment and was killed in the Civil War) and James became the family’s mainstay. His life was bleak, but in no instance during the many times he was asked to contribute his reminiscences to various publications did he more than hint at the actual horror of his early existence. By contrast with his son, James was inclined—publicly at least—to imbue life with the gallant optimism and rather conventional pride that had always made him loved and respected outside his family. The views of both father and son were distorted and dramatically heightened by their strangely disparate temperaments.

For example, Eugene O’Neill’s impression of his father’s boyhood is contained in the lines he wrote for James Tyrone in Long Day’s Journey Into Night:

It was at home I first learned ... the fear of the poorhouse.... There was no damned romance in our poverty. Twice we were evicted from the miserable hovel we called home.... I cried, though I tried hard not to, because I was the man of the family. At ten years old! There was no more school for me. I worked twelve hours a day in a machine shop.... A dirty barn of a place where rain dripped through the roof, where you roasted in summer, and there was no stove in winter, and your hands got numb with cold, where the only light came through two small filthy windows ... I got ... fifty cents a week! And my poor mother washed and scrubbed for the Yanks by day and my older sister sewed.... We never had clothes enough to wear, nor food enough to eat.”

This was true as far as it went, but it was only part of the story. James O’Neill’s own romanticized version presents a startling contrast:

“I tried many kinds of work after my father died. I was a newsboy for one day.” (He had been hoodwinked into buying a bundle of day-old papers for twenty cents, and barely escaped being turned over to a policeman by his first customer. James thought this was funny.) “Then I was apprenticed to a machinist. Somehow, the clank of iron, the ring of the hammer, the heavy glow of the forge seemed unattuned to the romance of Kilkenny’s mossy towers, where walked the shadowy ghosts of Congreve, and Bishop Berkeley, of Dean Swift and Farquhar—Irishmen all, who wore their college gowns in and out of the grassy quadrangle of the venerable seat of learning that is Kilkenny’s boast.... And so three or four years went along, careless young years, when spare evenings were spent poring over a Shakespeare given me by an elder sister, of losing myself in the land of romance at the theatre where I was an established gallery god.”

While the “careless young years” were largely the figment of a mellow imagination, James’s lot did improve more than one is led to believe by Long Day’s Journey Into Night. His sister made a reasonably good marriage when James was fourteen and her husband, who had settled in Norfolk. Virginia, sent for him.

The Civil War had begun. James’s brother-in-law did a brisk business in military uniforms. James, who participated, earned a good salary and was rewarded with an instructor provided by his brother-in-law. “For three years I worked in the store all day and studied with my tutor in the evening,” James once recalled. “He was a man of liberal tastes, and, liking the theatre, he took me with him twice a week to see the plays. It was then that I formed my taste for the theatre. When the war was over my brother-in-law sold out his business and moved back to Cincinnati, and I went with him. Having saved a little money I tried to go into several small businesses, but was not successful. I found my money going and wondered what I should do.”

This account is a relatively sober one for James. In most cases he preferred to embellish. Just three years before his death he was still giving an imaginatively colored story of his beginnings. Describing his introduction to the stage, he wrote:

“I believe I had a subconscious assurance—the promise of a sublime— possibly a ridiculous faith—that I should be an actor one day, although no possibility seemed more remote. However, what’s an Irish lad without his dream? And so I carried mine along with me cherishing it.”

Many years earlier, however, in writing to A. M. Palmer, a New York theatre manager with whom he had a long association, James prosaically, and no doubt honestly, informed him that he had “drifted to the stage without interest.”

“I was fond enough of the playhouse,” he added, “and had the curiosity, common among boys, to have a peep behind the scenes so that I took an opportunity to go on as one of the lads in the last act of ‘The Colleen Pawn,’ which was being played at the National in Cincinnati, Ohio. I began the thing as a lark, but the stage manager prevailed on me to remain.”