Asher

Our Dark Passenger

Anarchists Talk About Mental Illness and Community Support

Depression, police terrorism, and me

Are we Falling? The War Machine

Places to look for help in Aotearoa / New Zealand

Discussion Questions for Workshops and Groups

Also published by Katipo Books — www.katipo.net.nz

Contents

Front Cover

Contents

Introduction (Asher)

Bryden’s Story (Bryden)

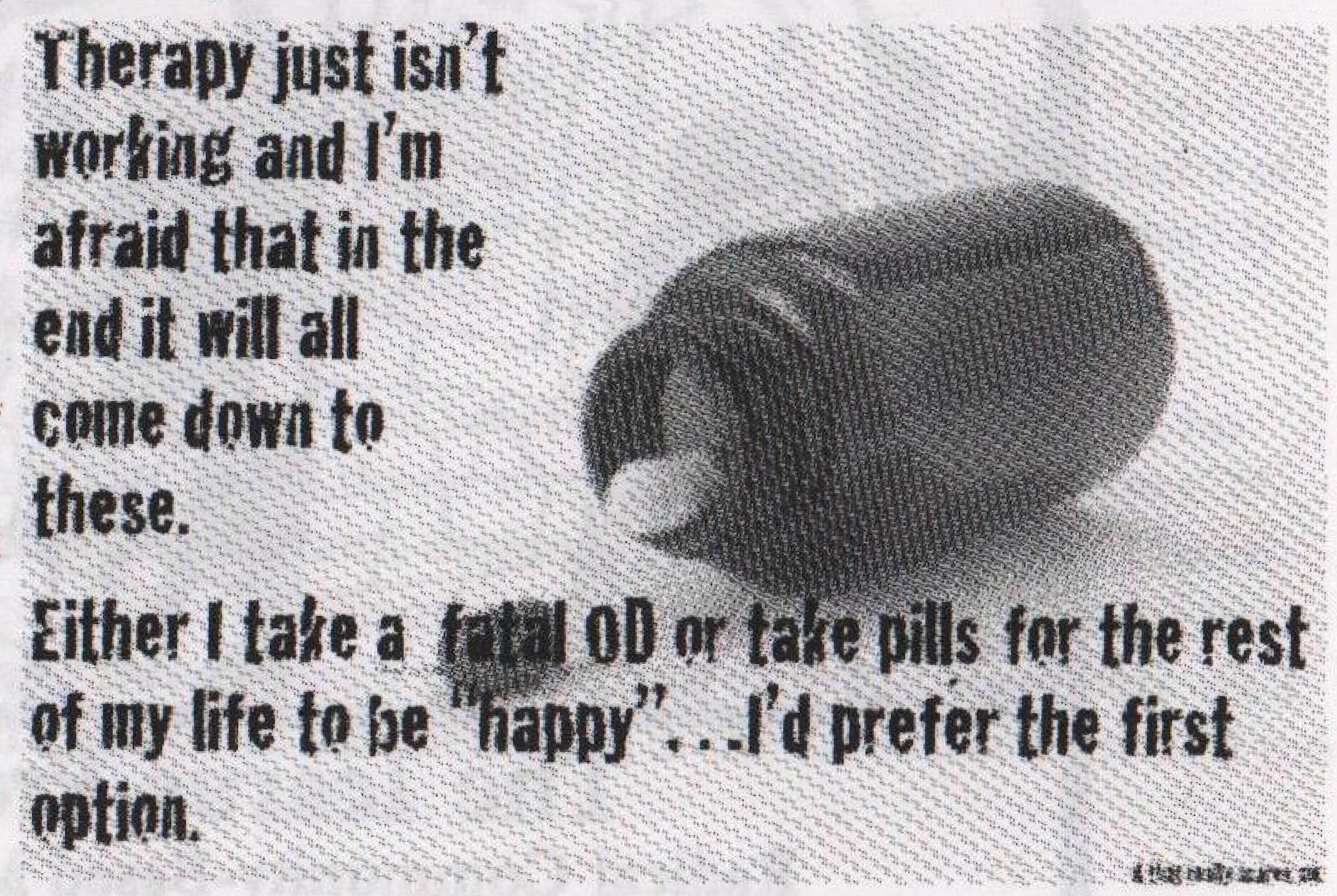

Ending it all (Anonymous)

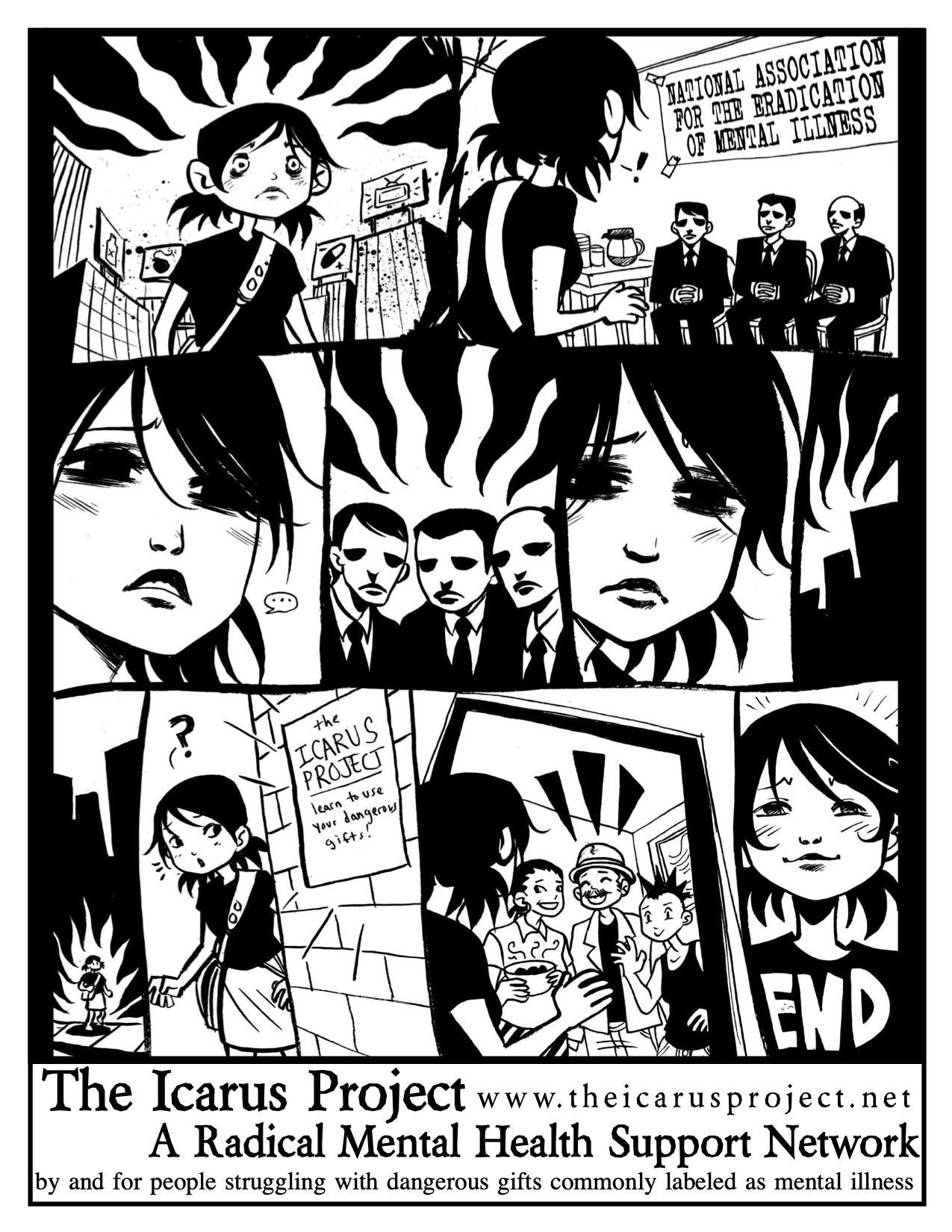

Cartoon (The Icarus Project)

Mental Illness: My Struggle (Asher)

Depression, police terrorism, and me (Anna-Claire)

Amy’s Poem, Drawing, Are we Falling? The war machine (Amy)

On Being Alone (Asher)

Places to look for help in Aotearoa / New Zealand

Activism and Depression (Bexxa)

Discussion Questions for Workshops and Groups (The Icarus Project)

How I Became a Thief (Jessica Max Stein)

The Spoon Theory (Christine Miserandino)

Also from Katipo Books

Back cover, 5 things to NOT say to someone suffering from depression

WARNING

Parts of this zine are likely to be triggering to those who have a history of self-harm or mental illness, so please use your own discretion when deciding to read.

If you think you are likely to be affected negatively by this zine, please DO NOT read it!

Fonts: Header/Footer in Trajan Pro, 12pt. Text in Palatino Linotype (Headings in bold), 12pt

Collated and designed by Asher (anarchiazine@gmail.com)

Published by Katipo Books — www.katipo.net.nz

PO Box 377, Christchurch, New Zealand / info@katipo.net.nz

First published: May 2008

Anti-Copyright: Feel free to copy and distribute

Introduction

Thanks for picking up this zine. It includes a collection of writings (and some art) from anarchists across Aotearoa on their experiences with mental illness, and some interesting/thought provoking pieces stolen from various places on the internet, including from The Icarus Project (www.theicarusproject.net), a radical mental health network in the USA that’s well worth checking out.

It is my firm hope that this little collection will help to spark more discussions about mental illness within our political communities and friendship circles, that we can begin to offer each other and ourselves the support we need. We need to realise when people are drifting away because they aren’t able to cope, and we need to be doing all we can to give them all they require.

In our supposedly radical communities, mental illness is deeply stigmatised, and even at times ridiculed. It shouldn’t be up to those of us in our deepest depressive states or our most manic episodes to call people out on this shit, but so often, if we don’t do it, nobody else will.

To give an example: My depression was treated far more seriously by my WINZ case manager when I went onto the Sickness Benefit than it was by most of my friends when I told them I’d gone onto that benefit. Sad, and yet not fucking surprising. Almost every friend I told about my getting onto the Sickness Benefit made some comment about how I was scamming WINZ (which isn’t a bad thing of course, but I wasn’t!) and, sadly, each time I played along. It was easier to pretend I was OK, and I’d lied to WINZ to get easy money. The reality was totally different — if I had tried to take on a full or even part time job, I wouldn’t have lasted a week before falling apart completely. I find it hard enough to get out of bed, to smile, to act (and its almost always an act) like. I’m coping without having time-constrained commitments (ie — a job) to live up to.

We need to become better at opening up and talking about our own experiences with mental illness — its fucking difficult and scary, especially when you don’t know how those you are opening up to are going to react, but it is the only way that we are going to be able to support each other. At the same time, we need to realise when talking isn’t the best move — I know I’ve triggered at least a couple of especially depressive episodes by reliving past ones in an effort to explain them.

Anyway, thanks to all the contributors, I hope all the readers enjoy the zine, and feel free to send any comments to anarchiazine@gmail.com. This will probably be a one-off zine, unless I get a lot of people offering submissions...

Bryden’s Story

I don’t remember exactly when my parents started taking me to psychiatrists, but I must have been pretty young. My earliest memory of these visits is being in an office/waiting room area and being made to take some foul tasting white pills. I was really uncomfortable with these appointments and refused to say anything, mostly just sitting there, crying. One guy got me to draw pictures. It was quite traumatic finding letters years later analyzing these drawings that I had just done for fun. Later, when I was 10 or 11 I went to some other lady, was even quieter and played with lego and dinosaurs.

When I was 12 or 13 I got real mad and totally refused to see anymore horrible psychiatrists. I started smoking pot and drinking a bit. I was feeling really crap about liking boys now, and didn’t know how to deal with what I was feeling, and was so shit scared of anyone finding out I couldn’t talk to anyone about it.

I’ve had depression on and off my whole life and wanted to kill myself frequently from about 13–15, I cut myself but never tried seriously. I got really sick when I was 17, with intrusive suicidal thoughts after working too much, and not sleeping or eating. The doctor put me on sleeping pills when I started to have problems sleeping, but these .fucked me up worse and I hallucinated on them and freaked out.

My mum got worried and we had the Crisis Assessment Team over. They asked me a bunch of weird questions and said they had seen a lot worse. The psychiatrist I was made to see was a dick and disputed all my claims about the dodginess of anti depressants. He put me on Aropax, which I took for day and then threw out.

The counselor I ended up seeing instead was also a dick. I told him repeatably I wasn’t comfortable with him taking notes and he just kept on taking them. I made an appointment with another counselor, but didn’t go, I bought cigarettes and went to the beach instead.

I wasn’t involved with the anarchist scene at this stage, I had just stared going to demos.

The next kind of breakdown I had was maybe a year later. I was lying in bed, home alone, a bit stoned and bit boozed, when I heard someone in the house and saw torchlight under my door. I froze, then couldn’t find my cellphone, jumped out my window and the neighbours called the cops. After this I was having anxiety attacks, couldn’t sleep (again) and was pretty paranoid. This time the doctor gave me lorazepam (new and improved valium) which turned out to be horribly addictive. Now, after 21 years of recurring depression I have finally learnt to recognize when Tm started to feel down. Usually it just takes a few weeks of long walks, writing and taking it easy to get back to my freaky old self. Lots of good sex and cuddles help too. And cupcakes. And staying the fuck away from doctors.

I self medicate with valarian and cannabis.

As I tend to sort my own shit out most of the time, I haven’t really had any support from the Wellingtown anarchist posse, apart from asking for the occasional hug. Would be neat if there was a mental health support group/network in our community, cos what does it mean to be well adjusted in such a fucked up world.

Ending it all

I dream about suicide a lot.

Sometimes, I dream about it in the night. I dream of taking pills, of jumping off a bridge, of walking in front of a truck. I wake up, scared shitless, not just at the dream, but at how I can’t stop myself considering, while wide awake, if maybe it would be the best idea to just end it all.

Other times, I daydream about suicide. Walking down the road, I drift off into thoughts of jumping in front of oncoming traffic. Frequently, I jolt myself back into reality just in time to stop myself from turning my dream into reality. Holding onto a lamppost, I breath deeply to try to regain myself, to find the strength to know that I can let go of the lamppost and still control my emotions.

I lie in my bed, partially reading a book, but mostly dreaming up ways to end it all with as little pain as possible. I dream of my suicide note, and how I will explain my actions to mv loved ones. I wonder who would attend my funeral.

Most of the time, I manage to check myself, to bring myself back from the brink. Occasionally though, I find myself unable. On a few occasions, friends interventions (unbeknownst to them) have probably been the only thing keeping me alive. On other occasions, it has simply been my fear. What if I take these pills, don’t die, and end up in a coma? What if I jump off this, but end up paralysed for life instead of dead?

I’ve never talked to anyone about this. My friends know I’m depressed, but I don’t think they have a clue about my suicidal tendencies. I don’t know how to begin to discuss it, or who I could discuss it with that could actually do anything about it.

I wish people were more proactive. I wish more people would offer me support. And, most of all, I wish I knew how to accept it.

Mental Illness: My Struggle

Originally published on January 17 2007, on anarchiawordpress.com

At age 14, I was diagnosed with clinical depression. At the time, being the naive and vaguely optimistic teenager I was, I thought that medication would “fix me”, that I’d take a few pills for a few months, and magically, it would all disappear, and I’d never have to think about it again. So when my doctor prescribed me an antidepressant, I took it, and waited for it to build up in my system to the point where it was supposed to have an effect. It didn’t. So, I went back to my doctor, and still faithful to the medical establishment, I took her advice and increased my dosage. Again, no noticable effect. So again, I increased my dosage. After a while, this began to have an effect, but certainly not a desirable one — my sleep, already poor, became even worse, my appetite became totally insatiable (I put on around 15-20kg in just 2 or 3 months), and frequent uncontrollable mood swings were the order of the day.

Clearly, I could not take this medication any longer, so my doctor switched me to another pill. A short time later, my dosage was again increased, to the point where I was taking twice the reccomend maximum adult dosage, at age 15. The side effects from this medication were similar to the previous one, only amplified massively, lb cope with my severe lack of sleep (50+ hours without sleep wasn’t uncommon, and what little sleep I did get was in short bursts and unsatisfying) I was given sleeping pills, which at least gave me a few nights healthy rest.

All through this time I was also seeing a counsellor, an experience which I have tried my hardest to erase from my memory. It essentially boiled down to hours of being patronised, of being asked to talk and then not being listened to...I quickly began to dread my appointments and frequently refused to go.

As this dragged on and on, it got to the point where I decided I could take it no longer. While camping in January 2001, I threw all my medication into a river and swore to myself I would never take anti-depressants again, a promise I have kept to. And yet, 9 years since I was first diagnosed, my illness still effects me in

• every waking moment. Two or three times a year, during especially bad periods, I consider going back on medication, but the memories of the side effects are still too strong in my mind to allow myself to do that.

My illness definately marginalises me within society. I can think of a number of friendships I have lost due to it — both from friends, who, feeling unable (or unwilling) to offer any meaningful level of support that I have needed from time to time, have simply run away, and from people who’s response has been so

patronising or otherwise offensive that I have lost any desire to be friends with them.

So often, people delegitimise mental illness. I have primarily experienced this in two ways. The first regards mental illness in a way that noone would ever regard physical illness — with virtual contempt for the sufferer. This way sees the sufferer as “too weak”, otherwise they would be able to “get over it”. The second, however, is more worrying for me personally, as I think it is limited to the anarchist/activist milieu, which is what I mostly hang out in — this is the belief that the sole cause of mental illness is the current capitalist, racist, patriarchal society we live in, and “after the revolution there won’t be mental illness”. To quote from an article I wrote a while ago:

Yes, it is entirely possible (and even likely) that the current society does make mental illness more common. But, just like how even in an anarchist society cancer would still exist, influenza would still exist, likewise mental illness would still exist. You might think you’re making a political statement when you say it, but what you’re really doing is invalidating the feelings and experiences of your friends and family that sujfer every day.

Now, while the idea is incredibly offensive to me, it is perhaps something J could deal with if people at least approached it on a politically consistent level. But they don’t. There are plenty of problems in society today that exist because of the capitalist, racist, patriarchal society we live in that wouldn’t exist if we destroyed capitalism, patriarchy and racism. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t actively work on them in the here and now. You don’t see people ignoring decolonisation work, or anti-rape work (both of which are incredibly important) because they wouldn’t exist if we smashed racism and patriarchy. So why ignore mental illness, even if you believe it wouldn’t exist in your utopia?

The lack of desire to seriously engage with the mental illnesses that so many people within my local anarchist community deal with has caused me to barely broach the subject with even my closest friends. But I’m sick of that. Tm sick of the silence. I’m sick of crying alone.

Depression, police terrorism, and me

For the past year I have been mentally ill with depression. The stress of the October police terror raids triggered in me an episode of insomnia, social anxiety, obsessive thinking that verged on paranoid delusion and suicidal thoughts. The intense period of this lasted a week until my mum got back from overseas. My usual support network of friends was overstreched, reeling from what was happening to our community.

My strategies for dealing with this were varied. I smoked a lot of pot. In the short term, that made the lows not so low and brought my attention to what was just in front of me, which was all I felt I could cope with. It motivated me to feed myself too, which I was finding hard to do. I could put myself to sleep with a joint. Long term, though, I was just sweeping under the carpet lots of emotions that the situation had brought up for me and denying myself the opportunity to learn and grow.

I had more healthy strategies too. For the first couple of weeks, I meditated each morning. I took up drumming, thrashed the kit for an hour or two a day. I found great feelings of anger, fear and powerlessness, which can become quite self-

destructive, could be transformed. So I drummed as we learned in Otautahi of the terror inflicted on communities in Tuhoe country and other places, and of friends held indefitnitely in prison, possibly for years.

I painted banners. One-a-day in the second week after the terror raids. I found I could paint for hours, barely noticing the time going by. Aside from banners for the solidarity group, my subject was the 1981 Springbok tour protests. This was great for my manic thinking, my brain well preoccupied with this historical obsession I had been researching in the weeks before the raids.

Since October, I have had a sore throat. I believe it is the pent up emotions I felt unable to face back then. Following a toothache and wisdom tooth removal, my insomnia returned, and with it social anxiety, obsessive thinking and suicidal thoughts. So more drumming and this time hours spent playing with poi, writing and dancing around the house. I am not drinking or smoking pot this time, which means facing emotions I have been avoiding for years. Past hurts, of abuse and neglect I experienced as a child, have been coming up for me. Memories of events that happened over 12 years ago have been lurking just below the surface, and would overcome me with great sadness without warning.

I am ready for growth and change. Time to process this stuff and let go. Approach my family and begin our healing. Even realising this, articulating it in words, I have felt a great surge of energy, love and self acceptance. I feel more real and alive than I have in so long — this I realise is a taste of what it is like to live without depression. While I still cry every day, I no longer think about killing myself. I can see myself recovering, so I am able to play my part in the struggle. Io support indigenous activists asserting their right to self-determination. To protect our mother, the earth. To challenge apathy and raise consciousness. This is my life work. I am ready.

Amy’s Poem

As the sun hurtles through space, we turn on our axis, creating day and night, and I am tucked up in my bed. The wind against my window frame comes blowing, travelling across the earth from a huge distance, blowing salt into the air. Birds sit in a tree, calling in echoes down into the valley, I can hear them. The air is early morning, it smells wet and then I realise, where I am...and that we don’t actually know where we are... it’s then that I find peace.

Are we Falling? The War Machine

Learning to Write Number 2.

Not that long ago I found out that my dad’s aunt was schizophrenic, the first generation, because my dad’s sister also was diagnosed with this disease. I believe in biodiversity. I have decided to take a state test. I m tired of trying to explain to people who believe that I am sick, that I actually feel really good. A friend of mine once made me laugh by saying, that, you only have a problem if you think you do.

My mother has this stuck in her head, on delay, “I believe at the bottom of my hear t, that there is something wrong with you”.

I do love her.

My ideas are my identity, I have had experiences and chosen to believe in them... and have even at times chosen not to believe in belief, sometimes I feel that social norm and individualistic marketing manipulation has taken my family away from me. psychologically speaking. I miss the old days, when I didn’t know about any of this crap.

Here are some thoughts, my belief’s, myself and I.

Some time’s I fear to write what I think because I m not sure I understand. Ideas and words are complicated, everything is complex. Or maybe it s just me who has a complex. A complex for the War Machine!

‘How can we create change in this world, when the very word, change, is associated with money.’

I read this zine that I picked up from a music shop when I was travelling through cape town, it was an independent zine, there was this article in it from a lady called Zinzina Martin and it was about freedom. I wish I still had the article, it is long lost, but by memory I can still remember some of what she wrote.

“There is a theory about life and death, that basically state’s, when we are born into this world, our soul’s decide to become earth bound and assume human form... that this life, is the eternal struggle, to rise to the planes from which we have come”.

It is about freedom, about being free and that we are not actually free... because of social and political boundaries.

change! I’ve heard that the generation gap does not facilitate this, but more so, Living within Globalisation, socially. The social gap, does not facilitate either.

When in reality, for each one of us, our constructed identities, our diversity and perspective is important (or not) individually, but necessary for our survival.

So what happens if we take, an individualistically minded individual, with their own sub culture and community, and group them together with 4 other individualistically minded sub community’s, to create positive social change? The World is Doomed!

I have seen people in their minds challenge their idea’s, and re-invent or reprogramme their mind’s to become better individuals for themselves and other people, to create a better world.

Somebody should write a book called ‘how to be happy in a sick society’. Although in truth, I don’t think id like to see a tree fall, for this one.

I feel bitter about my privilege, in knowing, that it has been built upon the foundation of war, as an elder of my blood, once said, “The War Machine”. And to my grandfather, who served in this war for my future, RIP.

You’re born into this world, and have all these amazing experiences, you look around, and realise where you are, then, realise what you are, and whom you’re with...

On Being Alone

Originally published on March 23 2008, at anarchia.wordpress.com

So, at the moment, I’m alone in the house, and have been for the last couple ot days. One ot my flatmates is away, at the celebrations for the 100th anniversary of the crib-time strike in Blackball which was the start of a wave of militant unionism in Aotearoá (later subsumed into the Labour Party, unfortunately), while the other is at his partner’s house, and the visiting Gemían anarchist who was staying at mine has also moved on to other parts of the country.

Last time I was alone for any length of time was over new years, and at the time, I felt somewhat similar to how I do now — to put it in as few inadequate words as possible — not good.

Of course, I have several reasons to be happy — I’ve just become an uncle for the first time, I’m in a wicked flat with great people (and 3 cats and temporarily 4 chickens), I have a firm plan for the rest of 2008 that I’m quite excited about. I also should be really busy — I have 3 articles (total of around 6000 words) all due this weekend, which I haven’t really even started on (except in my head), and a smattering of other work to do for Katipo Books and for local solidarity organising with the October 15th arrestees.

Instead, I find myself frozen in inaction. Even typing these words is significantly more effort than it should be. Getting my thoughts onto paper (or, more accurately, computer screen) is, while possible, a mammoth task for me at the moment.

This literal aloneness that I am currently experiencing only brings to the surface a deeptelt metaphorical aloneness that seems to be with me almost every day. At the start of the movie Fight Club, Edward Norton’s character describes the experience of insomnia: “Nothing’s real. Everything’s far away. Everything’s a copy of a copy of a copy.” As someone who suffers from insomnia from time to time (usually coinciding with my lowest periods), this really resonated with me the first time I watched the movie. However, it also provides a glimpse into the appearance of life to me during my depressive states, even when I’m sleeping well.

I

For me, I frequently feel like I’m not in my body, but watching it. I might be having a conversation, but that’s not actually me, not my consciousness. While my body is doing these things, my consciousness is watching on, stuck in my brain racking over a conversation I had a week ago, a month ago, at some point in my childhood — searching for a hidden meaning, thinking of a better comeback, analysing why I said what I said. My consciousness likely won’t experience the conversation I’m taking part in until later in the day, week or month, when it processes it while my body (what would normally be perceived as “me”) has long moved on.

Still with me? Good. Hopefully this is making some semblance of sense, I get the feeling sometimes that the English language simply doesn’t contain the words to explain some things.

This experience I have just described, the turning of my life into a film I’m constantly watching, leads to an overwhelming feeling of loneliness. I think this is at least partially responsible for my seeking of intense experiences — for it is during these times that I feel most in my own body, it is during these intense times that I actually feel emotions, rather than observe myself experiencing them from the outside. It is in this seeking of intensity that I understand those who regularly self-harm (luckily, something I’ve mostly been able to avoid) — the need to actually feel is an indescribably vital part of living.

I seek out these intense moments in a range of ways — I’ve tried drugs, and while they work in the immediate sense, the after-effects are almost never worth it (and so, these days, I more or less entirely stay away from them). Travel and moving to new cities/countries also seems to work for a period — the sheer shock of being so far from everything I know forces me back into myself. This tends to last for a little while, until I’m settled in to my new location, at which point everything goes back to what I sadly consider normalcy. Starting relationships also seems to work — the intensity that comes with a new relationship jolts me into the moment, although, as with travel/moving, this doesn’t last.

I’he last example I’ll give is something that I’ve only begun to realise in the last few days, and properly only this weekend, as I’ve had plenty of time to stew inside my brain. Anyone who knows me well knows all too well my desire to have kids. I’m now beginning to wonder how much that is connected to what I’ve just been discussing — there is no doubt that, most of the time when I interact with my friend’s children, I am drawn back into myself, back into genuine emotion. Perhaps my desire to have children of my own is tied in with this, as an opportunity (perhaps the only one), to put myself inside my body for the majority of the time. In this, however, I have fears. Who is to say that, as with moving or new relationships, enough time with a child won’t simply see me seperate my consciousness from my body again, lose my connection with my experiences...

And, despite the ever increasing knowledge of my condition, despite the fact that I now feel able to write about it, to talk about it, to begin to describe it, I still am stuck in the same place I started — totally disconnected from my own reality, totally alone.

Places to look for help in Aotearoa / New Zealand

Depression.org.nz

This website, run by the Ministry of Health, is actually surprisingly good! The site is broken as I write this, but I imagine it’ll be back up. This is the 24/7 face of the campaign that you probably will have seen around on TV and in the newspapers which attempts to destigmatise depression.

The Lowdown — www.thelowdown.co.nz

The “youth” version of Depression.org.nz, fronted by a bunch of semi-famous people, telling their stories about depression. They offer a free text service — text them before midnight with any questions and they’ll get back to you ASAP. The most impressive part of this site, in my opinion, is the “Stories” section, which contains videos (and some written stories) by a range of people about their experiences with depression.

Phone Hotlines

There are a range of phone hotlines for people suffering from depression and/or feeling suicidal.

Depression hotline — 0800 111 757

What’s Up (for 5–18 year olds, phone counselling) — 0800 WHATS UP (942 8787)

Youthline — 0800 37 66 33

Lifeline (professional counsellors, 24/7/365) — 0800 543 354

Activism and Depression

Originally published in Off Our Backs, Jani Feb 2005

I’ve struggled with melancholy since early youth-ranging from suicidal crisis-to blanketing sorrow-to months of numb depression. Sometimes sadness comes when I see a styrofoam cup and think about the environmental damage our society is causing; when I think about rape and war; or when I think about a friend in an abusive relationship. Sometimes I’m sad for no clear reason. Feeling sad about the world, and tending toward depression in general, has been a major motivating force for my activism, yet conversely, that same sensitivity can have a paralyzing effect which prevents me from being the non-stop activist I idealize. Learning to work with my depression, rather than against it has been necessary. I learn to try to flow with my moods, fighting the sorrow less, accepting the melancholy into my life as a teacher who keeps me in touch with the destruction of the planet.

Slowly, I’ve learned that not everyone tends toward depression, and not all activists are depressives. But mental health is everyone’s concern, especially in activist communities where a lot of what we do and think about is emotionally challenging. In addition to the “activist part” of us, we’ve all collected painful experiences in our lives that become part of our emotional stew and need attention and healing. Many of us have friends who have killed themselves. Many of us have friends who have tried to die or we ourselves have attempted suicide, and/or we struggle in numerous other ways. We activists must recognize that whether we are inclined to depression or not, dealing with police brutality and media distortions, combined with our awareness of global atrocity and our individual histories can be very difficult, and we need to take care of each other. We must be responsible for each other, responsive to different peoples’ boundaries, and take active roles in support. If the world’s in flames, we can provide emotional support as a group while we fight to end the fire. Otherwise, we’ll be eaten alive.

I want to share some of my experiences with depression, ways I use to cope and my wishes for radical communities/groups in the work of making our lives as mentally healthy as possible.

I protested the world trade organization in Seattle in 1999. I was heavily gassed and a cop pulled my hair. Unlike the activists in videos about the Seattle protests who expressed euphoria and an energy boost from the demonstrations, I was wounded spiritually, emotionally and physically. After the protests, isolated in my hometown in Maine, I was traumatized, desperate and suicidal. I felt brain-damaged, devastated, defeated. (In retrospect it was a very successful direct action that has had consequences for the corporate world, and added power to the global citizens’ voice, but it still hurt.)

When we return home to our sometimes small or non-existent activist groups after huge demonstrations, we can feel a lot of sadness, either from what we experienced at the protests, or the drop in energy from the mass movement to our smaller communities, and other factors. I wasn’t fucked up for being suicidal/outraged after experiencing the violence of the state, but that’s the message I told myself, heard from most of my affinity group, and many of the people I spoke with in Maine. I went to a leftist therapist at this time who was helpful, but kept referring to me as a “strong young woman,” and encouraged me to accept the world. I didn’t want the “woman” qualifier attached to my strength and experiences, and I refuse to accept the world as it is. I’m deeply grateful and indebted to the work that second wave feminists did in espousing women as strong people, but at this point in history I’d rather be viewed as a strong person.

I could have easily killed myself with all the rage, sorrow, loneliness and self-destruction I was carrying after Seattle. I wish there had been a network of people to help me process my experience with, and to put the protests in a historical global context. An activist support phone number would have helped. One night I called the local crisis line; it was alienating and not helpful.

I’ve dealt with depression differently over the years. I used to feel it was my duty to refuse to be happy-someone must bear witness to the misery, inequality and realness of the world! I wanted no part of the fake society where we were expected to put on a smile no matter how we actually felt (especially for people socialized as women); I refused to join the tyranny of happypancakeclones. I would maintain a sad face partly because that was how I felt inside, and partly to remind people that things weren’t as perfect as they pretended. I believed that no one in the world could truly be happy; I believed my friends shared the same amount of sorrow as me, especially when we were into drugs and sad/raging activist music. This method was a trap because after a while, putting on a sad face for the purpose of exposing the falseness of the society wore away at my own ability to feel joy.

For years, I dismissed my sorrow as “just teenage angst,” and when I wasn’t a teen anymore I beat myself up for not having “moved on” from that “infantile” stage of being a teen (as if deeply feeling sorrow and/or anger is reserved exclusively for infants in U.S. society). I told myself I was a privileged whiny brat who deserved to die, who didn’t have real reasons to be sad, etc. I felt guilty for having light skin, for living in the U.S., for being human. I wanted to save the world, but the way I dealt with my depression enforced my self-hatred, and I became more depressed and less useful. It was a trap that got worse the more I struggled to leave depression.

My recent method of dealing with my despair is accepting it into my life. Rather than fight it and fight myself, I try to respect my sorrow (at least from a distance!), and listen to it. I don’t always need to be the bleeding heart on display bearing witness to atrocity in otherwise happy-seeming situations anymore. I keep a pretty big space in my life for depression, but I try to enjoy life when possible too. I’m sure I’ll find other coping strategies. I have no idea why, but it seems I’ve (at least temporarily) left behind the past frequency of major suicidal crises. And perhaps some of my early depression was about being a teenager-not from an innate (biological cross-cultural phenomenon) “teen angst,” but because I had few choices: I hated school and its salute-the-flag-in-the-morning, don’t-conform-and-you’ll-be-punished/raped, anti-emotional landscape which produces a rigid culture of gender: cute, slim popular girls, and tough, jocky boys. School was a hostile environment; walking the halls was frightening. I never fit in, and eventually learned to say “fuck you” to the whole establishment of conformity and authority as a self-schooler and drop-out, but it scarred my spirit forever. Anyway, the point is that school was another trap/jail without any room to breathe, so it makes sense that I was especially sad as a teenager.

Over the years I’ve made choices in an attempt to avoid deep depressions. In 1997, I decided to go mostly sober-not for any anti-intoxicant reason; it was simply that I couldn’t tell if I was sad due to withdrawal, or the drugs, or when I was “just sad.” Which chemicals were messing with my spirit? (I should add that I credit my use of drugs in high school for helping me avoid suicide.) I also try to get 8+ hours of sleep a night, eat plenty of food, get plenty of alone time, and cultivate supportive friendships which include actively dealing with conflicts. I’ve learned to recognize pre-bleeding despair, and sometimes crisis. Previously I refused to recognize bloodsorrow as a reality in my life because the misogynist Christian (anti-body) society wants to use pms as proof that women are in fact biologically weaker than men, and tied to our (sinful) bodies (again, as if feeling emotions is somehow weak/ infantile/irrational). I don’t want every angry/sad emotion a woman expresses to be easily dismissed as “some biological ‘woman thing,”’ (no matter where we are in the cycle). So I fight against this analysis/dismissal, but I am affected by the bloodcycle, and it helps to approach a crisis with an awareness of where I am in my moonstrual cycle. A friend who tried to kill herself years ago later ascribed it to her pms. I want to build an alternate universe within patriarchy, but it’s challenging. It’s difficult to knit a healthy space to talk about blood-related things without in some way affirming the patriarchy’s biologically determined anti-body destiny of women, because there is no alternate universe in which emotions are valued, where emotions are a teacher, a guide, rather than the enemy to be suppressed.

Another thing I’ve come to is that it’s not safe for me to have dietary restrictions, though it would be more in keeping with my politics. For years I was vegan; at some point the veganism combined with misery and a desire to get love or be hospitalized or something (around the time of protesting the WTO) so, basically, it led me into self-starvation practices, even while accompanied with a fierce feminist critique of diet culture, an embracing of fat-positive activism, and, at least, a voiced rejection of some punk scenes’ valorization of skinniness. While that time of my life has passed, I think it might still be dangerous for me to have any sort of dietary restriction.

I’ve found that I can’t be very7 flexible with my mental health guidelines. I have to accept that I can’t live out the punk hitchhiker hobo dream I used to want, which is a good realization because that fantasy excludes a lot of people who simply can’t live that way. Sometimes I feel like a nerd with all my guidelines, but it’s too dangerous to let them go just to try to fit in to an activist scene.

I called last year my Mental Health Year, giving myself permission to withdraw from overt activism, to focus on depression, and figure out how to sustainably approach lifetime activism. The year was great! Living in a rented house-The Witchouse-with supportive friends who hung out downstairs laughing over popcorn and tea kept me from miserable isolation. I was always drawn downstairs (if sometimes reluctantly-who wants to voluntarily leave their cozy cocoon/nest of knives and self-hatred?). Yes, I still struggled with suicidal thoughts, cutting myself, the challenging aspects of living in community, and the urge to be out in the world stopping bombs, healing wounds, killing rapists, but I was in an emotionally safe space.

I watched the way feelings change and move, sitting with them until they pass and I get the energy to draw, dance furiously, masturbate, sing loud, indulging in joy and laughter wholeheartedly when it arrives, but letting sadness take me, too. I had no serious lover, it gave me the space to know that the ups and downs are in me. I couldn’t scapegoat a relationship. My mental health includes crying, yelling/singing times, signs/graffiti, screaming at harassers in cars, marches, food, sleep, friends and acquaintances (Some friends find the unpredictability of my moods unsettling and/or annoying. Some don’t understand my sadness, and don’t want to hear about it. I’ve found that I have much richer friendships with friends who are able to hang out with me when I am sad as well as joyful), spontaneous dancing, painting angry/ funny drawings, making desperate phone calls, getting massage or other healing work, a low-key job, solitude, chocolate, water. I have a kind of maintenance game — if I feel myself getting “too sad,” I will actively try to get out of it.

During the year, I raided the library for the self-help books I’d always rejected as yuppie navel-gaze panacea. Some of them were surprisingly helpful, and not all were yuppie and anti-activism. Speaking of Sadness by sociologist David Karp (a depressive himself) contains interviews with depressives in the U.S. I was surprised to read how many things depressives have in common in terms of how we learn to see and cope with our depression. The book fails to investigate society itself as a cause of depression, though there is a chapter that touches on that, questioning particularly why people socialized as women have a much higher rate of depression than people socialized as men (It can’t just be biology, can it???). Joanna Macy’s Despair and Empowerment in the Nuclear Age affirms that it is valid and absolutely real to suffer from deep despair as a result of the fuckedupness of the world that we live in. I would also recommend When Someone You Love is Depressed for practical information about how to take care of yourself while you are caring for someone with depression.

Last summer I went to the North American Anarchist Gathering. My favorite part was the workshop on mental health in radical activist/anarchist communities. In a huge circle, each of us talked about our relationship to mental health, suicide, despair, hospitalizations, pills, manic depression, etc. We talked about ways in which the protest scene is similar to the general U.S. culture, and ways it could be improved. We’re all different, and we bring different gifts, skills and wants to activism. We need to keep talking. We need to tell our friends what is and isn’t support for us, and create a scene that takes mental health seriously.

While we can work to make large-scale activist mental health networks, I think the best support comes from yourself and your local community or travel companions. I would love to see an international database of feminist, activist-ally, trans-ally, queer-ally, poor-ally counselors, doctors, and healers. I want mental health and healing be seen as an integral part of the radical activist community. This would lessen the concept that activism is typified by temporary heroic actions, and open room for activism to include more things. Yes, action is a necessity. But action might be a house meeting, or a year of rest. What defines activism? Is it not activist to be a single parent? To live in a community? To clean houses for a living? To reject your family’s wealth? To have sex in your wheelchair? To take up guns in the communities in which the police imprison men of color at a higher rate than they can go to college? To reject college entirely? To join the military to be the first person in your family who goes to college? To fight to survive cancer? To work against domestic violence?

We need dialogues about what motivates our activism, and what world people want to live in, so we know whom we are working with. We can’t just assume we all want the same things. We need to expand the definition of activist out of a temporary street-action centered situation. We need to have these dialogues, even as the U.S. government is destroying our kids and kids all over the world, as well as the Earth; I do not want to be part of an activist movement that perpetuates what I most hate about the independent-minded/play the game and you’ll be rewarded/ macho-dominated/divide-and-conquer society. The work we are involved in is challenging and wonderful, and while we each deal with different issues around mental health, we need to find ways alone and together so that we can survive and take care of each other.

Now that my Mental Health Year is over, the Witchouse is closed, and the Bush administration is killing and hurting everyone but themselves, how am I doing? Well, the Year never really ended., and the point isn’t how happy I am, but how well I can sit with my depression, and how to make the best use out of the rage, instead of becoming paralyzed. Tm lonesome, and I long for a community that reflects all of my wishes, dedicated to mental health.

I invite people to contact me on these issues. For the continuing anti-capitalist pro-diverse feminist revolution: rifka@riseup.net.

This article is dedicated to Yareak and Amilia and others who thought they needed to leave life. For everyone: Please, love yourself deeply, and get help when you need it. These are hard times we live in. You deserve years of nurturing and healing.

Some Mental Health ideas for (radical) communities in general:

-

Make retreat spaces: could include a network of safe houses for recovery; collective houses include rooms for healing, yelling, crying, whatever; plug into the intentional community network and find places that are willing to invite activists in for rests

-

Respect that some people can’t always go to big demos, can’t always do certain work; are still fabulous activists/friends, etc.

-

Respect that some folks do need big-pharma meds to stay alive and for other reasons.

-

Create free or inexpensive holistic health clinics

-

Trade massages, energy healing

-

Spend equal time debriefing, processing difficult actions/experiences/conflicts, as planning them...One great radical faerie structure for this is a Heart Circle: people in a circle/often with candlelight/an object that denotes speaker/each person can say whatever they want for as long as they want without interruption and an option to not be responded to

-

Try to see mental illness as a part of life; not necessarily bad/scary/negative/weak

-

Make alliances with mental health patient liberation groups in your area ” Create alternative care systems to psych wards, etc, but definitely make use of existing systems such as crisis hotlines, counseling, counseling groups, and hospitals if needed

-

As a supporter, get lots of support for yourself

-

Do fun stuff

-

Take sabbaticals from activism

-

Get to know your boundaries, respect them, and voice them

-

Talk about your experiences with mental health/mental illness

-

Maintain an easy to find international database of activist/trans/queer/poor- friendly counselors, doctors, healers

-

See where mental health/illness issues overlap with fights against sexual abuse and all other types of abuse and injustice

-

Acknowledge that activism can be very challenging and can be painful

-

Read helpful books; I recommend ...Unholy Ghost: Writers on Depression; When Someone you love is Depressed; Speaking of Sadness; Despair and Empowerment in the Nuclear Age; Mad Pride; Willow, Weep for Me

-

Experiment; find out what works for you-try herbs; foods; listen to your patterns

Note January 2008:

This article was written in a different time in my life- began it in 2002. Now that I have experienced suicides of close connections, I have a somewhat different view of depression and I’m sure this article would be different if written now. I also feel less part of any sort of big ‘movement,’ though my ideals remain the same. I think I had to learn to keep my idealism under wraps because it was too painful to continuously feel that it was unattainable. Activism is important to me, and I guess it’s true that even then I was questioning what we viewed as ‘activism.’ I remain committed to my mental health as well as the mental health of others, and to having societies perceive the many varieties of mental-ness in better ways. In the past few years I had great experiences with some good counselors. My best to you as we traverse our lives on earth!

Discussion Questions for Workshops and Groups

Originally published in Friends Make the Best Medicine: A Guide to Creating Community Mental Health Support Networks, available at theicarusproject.net

Having a series of questions can be a great way to focus a workshop discussion into deep and meaningful directions. Brainstorm ideas beforehand, potentially including:

-

What does it mean to be “mentally ill?”

-

What are the implications of being labeled sick by a society that is obviously sick?

-

How do we figure out what’s society’s madness, and what’s our own, and when the lines are too hard to draw?

-

Is madness a continuum rather than a set of definitions and diagnosis?

-

What does it mean to see our madness as a potentially dangerous gift?

-

What alternative frameworks exist for interpreting our mental health struggles?

-

Can we look at the role of race, class, gender, and other aspects of our identities in shaping our struggles while still taking responsibility for ourselves?

-

Can diagnostic labels help us see patterns without putting us in a box or becoming self-fulfilling prophecies?

-

When does behavior become “dysfunctional”?

-

Can we define for ourselves what an appropriate level of functioning looks and feels like?

-

What kinds of healing and wellness practices have helped us to get better?

-

What are our ‘early warning signs’ that we need to focus more on our wellness and health?

-

How do we take care of each other and ourselves?

-

How can we respect decisions to take psych medication but still be honest about the risks of these drugs?

-

How can we respect decisions to try alternative treatments and/or reject conventional medical treatment?

-

How can we respect choices to use recreational drugs when they seem self-destructive?

-

What are our options when we or someone we know seems to be going into • crisis?

-

What topics aren’t being discussed in our communities that we want to see discussed?

-

What are people struggling with and how can we find better ways to talk about

How I Became a Thief

Originally published in Mad Love zine, available at theicarusproject.net

I have stolen only once in my life, a single object, from a private mental hospital on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, where I spent 72 involuntary hours in March 1998. I was 21. I stole a book, the definitive biography of the poet Anne Sexton by Diane Wood Middlebrook. I already owned a copy, back home; mine was in better condition.

I bought the book—hardcover, $24.95—in tenth grade for my first-ever research paper, in which I compared Sexton’s life to Sylvia Plath’s. I argued that both poets were “mentally ill” because they were oppressed by the narrow roles for women in the 1950s. They weren’t “crazy,” I argued, just undomesticated. I got an A.

I read the book from time to time, as I reread all my books, like visiting old friends.

I loved Sexton’s patrician face on the cover, the slim cheekbones and Roman nose. Her hands were up in a shrug, cigarette dangling. She wore a black-and-white print minidress, almost psychedelic, her bare legs crossed beneath.

* * *

My descent into thievery began when a “friend” brought me to the emergency room of St. Vincent’s hospital. “You just seem really depressed,” she said. “Let’s just go talk to them.” I was pretty depressed. It was easier not to fight.

The nurse ushered me in to a cot and left me there for four hours. At two in the morning, offended and fed up, I walked out during a shift change and went home to shower, feeling oddly dirty, and to bed.

I woke to a pounding on my door, a man’s voice shouting. “Open up! This is the police!” What the fuck? I groped the lamp on, squinted at the clock: 5:43 am. “Open this door right now!” I was naked, a bad dream. I dashed for my clothes on the bathroom floor. Suddenly, urgently, I had to piss, squatting over the toilet, palms clapped over my ears. Time seemed strangely elongated, each second unbearably slow.

They pounded and shouted. I wiped and flushed and dressed, clumsy with terror. Should I go out the window, down two flights on the fire escape? Were they out front too? Were my neighbors lying awake, listening to this?

I didn’t know what else to do. I opened the door.

As soon as I cracked an inch they pushed it wide all the way, two men and two women in blue uniform bursting in as I backed up. “Put your hands behind your back, please.”

“Are you—uh—arresting me?”

“Don’t answer her,” said one of the men. “They all do this.”

“We all do what? What ‘we’?”

“Put your hands behind your back, please.” I complied, facing the door. They wrenched handcuffs around my wrists, yanking my shoulders back. “Put those on.” I slipped into my sandals, nearly losing my balance as I shifted from foot to foot. “Can I pack a bag?” I asked.

“Let’s go.”

“Can I at least take my keys?”

I heard jingling behind me. “You’ll get these back at your release. Let’s go.” The cop put a warm, flabby hand between my shoulder blades, guiding me downstairs and into the blue dawn to an idling ambulance. I here I was made to lie on a cot atop my pinioned arms, jouncing through the streets back to the hospital until I lost feeling in my wrists.

* * *

The hospital was no place to heal. There was no privacy, no space for contemplation. I saw one therapist for about 20 minutes, an older man with a Celexa clipboard and receding hairline. “I’ve seen plenty of girls like you come through here,” he said.

“Now trust me. If you don’t start on a regimen of anti-depressants, you’ll either live your life in and out of mental institutions, or you’ll kill yourself. I think we’ll start you on Paxil.”

They gave me three pills, one oversized green and two pink, at breakfast, lunch and dinner. It was easy amidst the din of the dayroom to slip the pills into my pocket and flush them at the next opportunity. The meals were usually tough meat, a white roll, half-frozen peas and little carrot squares. I picked at the vegetables, didn’t connect this with the light, distant feeling in my head throughout my stay.

The social worker cornered me spacing out in the dayroom. “I have something for you,” she said. I was dubious. I despised the social workers, most only a few years older than I, prancing in every morning in their fresh clean clothes.

I followed her bobbing blonde ponytail into the closetlike social workers’ lounge, which stank of orange deodorizer. Did they sneak cigarettes in here? I perched on a metal stool as she opened a grey footlocker, turning with a book in her hand. I started at the familiar cover: Anne Sexton’s bright eyes and expressive hands, her long elegant legs.

“You’ll like this,” said the social worker. “I think you can really relate to her story.”

I glanced up, curious. The social worker smiled thinly, avoiding my eyes. She seemed strangely afraid of me. I felt a sharp burn of shame, a searing anger. Slowly I crossed my arms. Slowly I spoke. “Anne Sexton,” I said. “She killed herself, you know. Carbon monoxide, in the garage. Wearing her dead mother’s fur coat.”

The social worker’s mouth stiffened. She looked down at the book, riffling rapidly through its pages, too fast to actually read. When she glanced up I caught her eye and held it, like a dare.

She broke the gaze, turning away with the book. “I can’t let you have this.” She shut the locker abruptly. “I think you know why.”

Late that night, I tried the door of the lounge. It opened easily, the fruity scent evoking my old anger. I crept inside. The book lay right on the counter; I snatched it up and stuck it under my arm, backing out of the room, carefully closing the door behind me. The hall was empty. I snuck the book back to my room, hiding it in the pillowcase. When they let me out of the hospital I dropped it into my plastic Patient’s Belongings bag, along with my keys.

On my way home I gave the book to a peddler by Washington Square Park. He offered me money, but I told him he didn’t owe me anything.

I sat in the park for a while that afternoon, gladly, basking in the sun on my shoulders.

I still own my old copy of the book. I don’t read it much.

The Spoon Theory

Originally published at www.butyoitdontlooksick.com. While it is about Lupus, I feel that the spoon theory also demonstrates well how many people with mental illnesses are forced to live their lives.

My best friend and I were in the diner, talking. As usual, it was very late and we were eating French fries with gravy. Like normal girls our age, we spent a lot of time in the diner while in college, and most of the time we spent talking about boys, music or trivial things, that seemed very important at the time. We never got serious about anything in particular and spent most of our time laughing.

As I went to take some of my medicine with a snack as I usually did, she watched me with an awkward kind of stare, instead of continuing the conversation. She then asked me out of the blue what it felt like to have Lupus and be sick. I was shocked not only because she asked the random question, but also because I assumed she knew all there was to know about Lupus. She came to doctors with me, she saw me walk with a cane, and throw up in the bathroom. She had seen me cry in pain, what else was there to know?

I started to ramble on about pills, and aches and pains, but she kept pursuing, and didn’t seem satisfied with my answers. I was a little surprised as being my roommate in college and friend for years; I thought she already knew the medical definition of Lupus. I hen she looked at me with a face every sick person knows well, the face of pure curiosity about something no one healthy can truly understand. She asked what it felt like, not physically, but what it felt like to be me, to be sick.

As I tried to gain my composure, I glanced around the table for help or guidance, or at least stall for time to think. I was trying to find the right words. How do I answer a question I never was able to answer for myself? How do I explain every detail of every day being effected, and give the emotions a sick person goes through with clarity. I could have given up, cracked a joke like I usually do, and changed the subject, but I remember thinking if I don’t try to explain this, how could I ever expect her to understand. If I can’t explain this to my best friend, how could I explain my world to anyone else? I had to at least try.

At that moment, the spoon theory was born. I quickly grabbed every spoon on the table; hell I grabbed spoons off of the other tables. I looked at her in the eyes and said “Here you go, you have Lupus”. She looked at me slightly confused, as anyone would when they are being handed a bouquet of spoons. The cold metal spoons clanked in my hands, as I grouped them together and shoved them into her hands. I explained that the difference in being sick and being healthy is having to make choices or to consciously think about things when the rest of the world doesn’t have to. The healthy have the luxury of a life without choices, a gift most people take for granted.

Most people start the day with unlimited amount of possibilities, and energy to do whatever they desire, especially young people. For the most part, they do not need to worry about the effects of their actions. So for my explanation, I used spoons to convey this point. I wanted something for her to actually hold, for me to then take away, since most people who get sick feel a “loss” of a life they once knew. If I was in control of taking away the spoons, then she would know what it feels like to have someone or something else, in this case Lupus, being in control.

She grabbed the spoons with excitement. She didn’t understand what I was doing, but she is always up for a good time, so I guess she thought I was cracking a joke of some kind like I usually do when talking about touchy topics. Little did she know how serious I would become?

I asked her to count her spoons. She asked why, and I explained that when you are healthy you expect to have a never-ending supply of “spoons”. But when you have to now plan your day, you need to know exactly how many “spoons” you are starting with. It doesn’t guarantee that you might not lose some along the way, but at least it helps to know where you are starting. She counted out 12 spoons. She laughed and said she wanted more. I said no, and I knew right away that this little game would work, when she looked disappointed, and we hadn’t even started yet. I’ve wanted more “spoons” for years and haven’t found a way yet to get more, why should she? I also told her to always be conscious of how many she had, and not to drop them because she can never forget she has Lupus.

I asked her to list off the tasks of her day, including the most simple. As, she rattled off daily chores, or just fun things to do; I explained how each one would cost her a spoon. When she jumped right into getting ready for work as her first task of the morning, I cut her off and took away a spoon. I practically jumped down her throat. I said “ No! You don’t just get up. You have to crack open your eyes, and then realize you are late. You didn’t sleep well the night before. You have to crawl out of bed, and then you have to make your self something to eat before you can do anything else, because if you don’t, you can’t take your medicine, and if you don’t take your medicine you might as well give up all your spoons for today and tomorrow too.” I quickly took away a spoon and she realized she hasn’t even gotten dressed yet. Showering cost her spoon, just for washing her hair and shaving her legs. Reaching high and low that early in the morning could actually cost more than one spoon, but I figured I would give her a break; I didn’t want to scare her right away. Getting dressed was worth another spoon. I stopped her and broke down every task to show her how every little detail needs to be thought about. You cannot simply just throw clothes on when you are sick. I explained that I have to see what clothes I can physically put on, if my hands hurt that day buttons are out of the question. If I have bruises that day, I need to wear long sleeves, and if I have a fever I need a sweater to stay warm and so on. If my hair is falling out I need to spend more time to look presentable, and then you need to factor in another 5 minutes for feeling badly that it took you 2 hours to do all this.

I think she was starting to understand when she theoretically didn’t even get to work, and she was left with 6 spoons. I then explained to her that she needed to choose the rest of her day wisely, since when your “spoons” are gone, they are gone. Sometimes you can borrow against tomorrow’s “spoons”, but just think how hard tomorrow will be with less “spoons”. I also needed to explain that a person who is sick always lives with the looming thought that tomorrow may be the day that a cold comes, or an infection, or any number of things that could be very dangerous. So you do not want to run low on “spoons”, because you never know when you truly will need them. I didn’t want to depress her, but I needed to be realistic, and unfortunately being prepared for the worst is part of a real day for me.

We went through the rest of the day, and she slowly learned that skipping lunch would cost her a spoon, as well as standing on a train, or even typing at her computer too long. She was forced to make choices and think about things differently. Hypothetically, she had to choose not to run errands, so that she could eat dinner that night.

When we got to the end of her pretend day, she said she was hungry. I summarized that she had to eat dinner but she only had one spoon left. If she cooked, she wouldn’t have enough energy to clean the pots. If she went out for dinner, she might be too tired to drive home safely. Then I also explained, that I didn’t even bother to add into this game, that she was so nauseous, that cooking was probably out of the question anyway. So she decided to make soup, it was easy. I then said it is only 7pm, you have the rest of the night but maybe end up with one spoon, so you can do something fun, or clean your apartment, or do chores, but you can’t do it all.

I rarely see her emotional, so when I saw her upset I knew maybe I was getting through to her. I didn’t want my friend to be upset, but at the same time I was happy to think finally maybe someone understood me a little bit. She had tears in her eyes and asked quietly “Christine, How do you do it? Do you really do this everyday?” I explained that some days were worse then others; some days I have more spoons then most. But I can never make it go away and I can’t forget about it, I always have to think about it. I handed her a spoon I had been holding in reserve. I said simply, “I have learned to live life with an extra spoon in my pocket, in reserve. You need to always be prepared”

Its hard, the hardest thing I ever had to leam is to slow down, and not do everything. I fight this to this day. I hate feeling left out, having to choose to stay home, or to not get things done that I want to. I wanted her to feel that frustration. I wanted her to understand, that everything everyone else does comes so easy, but for me it is one hundred little jobs in one. I need to think about the weather, my temperature that day, and the whole day’s plans before I can attack any one given thing. When other people can simply do things, I have to attack it and make a plan like I am strategizing a war. It is in that lifestyle, the difference between being sick and healthy. It is the beautiful ability to not think and just do. I miss that freedom. I miss never having to count “spoons”.

After we were emotional arid talked about this for a little while longer, I sensed she was sad. Maybe she finally understood. Maybe she realized that she never could truly and honestly say she understands. But at least now she might not complain so much when I can’t go out for dinner some nights, or when I never seem to make it to her house and she always has to drive to mine. I gave her a hug when we walked out of the diner. I had the one spoon in my hand and I said “Don’t worry. I see this as a blessing. I have been forced to think about everything I do. Do you know how many spoons people waste everyday? I don’t have room for wasted time, or wasted “spoons” and I chose to spend this time with you.”

Ever since this night, I have used the spoon theory to explain my life to many people. In fact, my family and friends refer to spoons all the time. It has been a code word for what I can and cannot do. Once people understand the spoon theory they seem to understand me better, but I also think they live their life a little differently too. I think it isn’t just good for understanding Lupus, but anyone dealing with any disability or illness. Hopefully, they don’t take so much for granted or their life in general. I give a piece of myself, in every sense of the word when I do anything. It has become an inside joke. I have become famous for saying to people jokingly that they should feel special when I spend time with them, because they have one of my “spoons”.

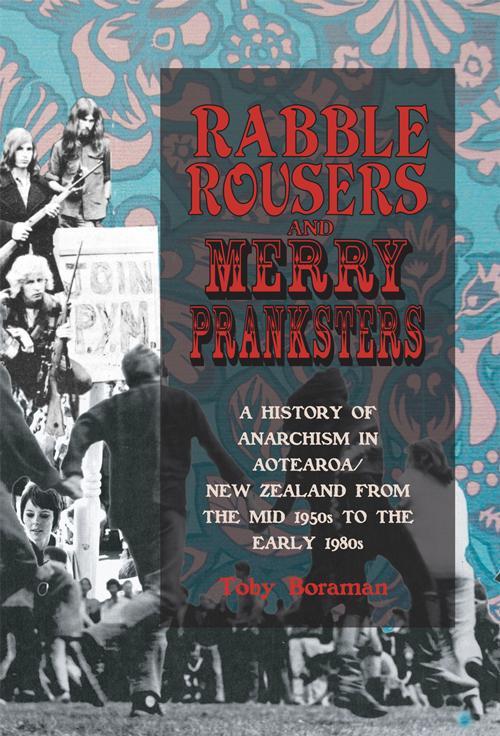

Also published by Katipo Books — www.katipo.net.nz

Author: Toby Boraman

144 pages

$30 + postage

Rabble Rousers and Merry Pranksters captures some of the imagination, the audacity; the laughs and the wildness that animated many of the social movements of the sixties and seventies in Aotearoa/New Zealand. During this time, particularly from the late sixties to the early seventies, an astonishingly broad-based revolt occurred throughout the country. Thousands of workers, Maori, Pacific people, women, youth, lesbians, gays, students, environmentalists and others rebelled against authority. Innovative new styles and anarchistic methods of political dissent became popular.

A colourful and energetic bunch of anarchists occasionally played significant roles in these struggles. Anarchists were prominent in the anti-nuclear, anti-Vietnam. War, anti-US military bases, commune, unemployed and peace movements. Rabble Rousers and Merry Pranksters is a richly-detailed tale about a much neglected antiauthoritarian Leftist current in Aotearoa/New Zealand history.

The book is a pioneering work. Lt represents the first major history of anarchism and libertarian socialism in Aotearoa/New Zealand. It is primarily based upon interviews and correspondence with participants in the libertarian socialist scene. It also draws upon extensive research into unpublished manuscripts, documents, magazines, leaflets and other ephemera written by anti-authoritarians. To capture a little of the distinctive and colourful political style of the period, over 100 images are included in the book, including cartoons, posters and leaflets.

Also available from Katipo Books — www.katipo.net.nz

Author: The Icarus Project

36 pages

As the title suggests, this pamphlet is a guide to supporting people in our communities who suffer from various forms of mental illness. It is produced by The Icarus Project, a predominantly US-based network of groups of people suffering from mental illness who have a dual focus — of supporting each other and of educating others about the reality of mental illness and the different options beyond medical treatment.

Double CD — over 1.5 hours of music

“Tu Kotahi — Freedom Fighting Anthems” is a CD Compilation to raise money for those affected by the October 15th ‘Terror’ Raids. Check the track listings at katipo.net

All the money raised will be split between organisations directly supporting those affected by the raids, and also working on consciousness raising around the issue. For more information on the raids, see www.octoberl5thsolidarity.info

5 things to NOT say to someone suffering from depression

“WHY DON’T YOU JUST SNAP OUT OF IT?”

“LOOK, WE ALL GET A LITTLE SAD SOMETIMES...”

“I UNDERSTAND HOW YOU FEEL”

“I’VE BEEN DEPRESSED TOO, THAT DOESN’T MEAN YOU CAN’T ... ”

“BUT YOU WERE SO HAPPY LAST WEEK!”