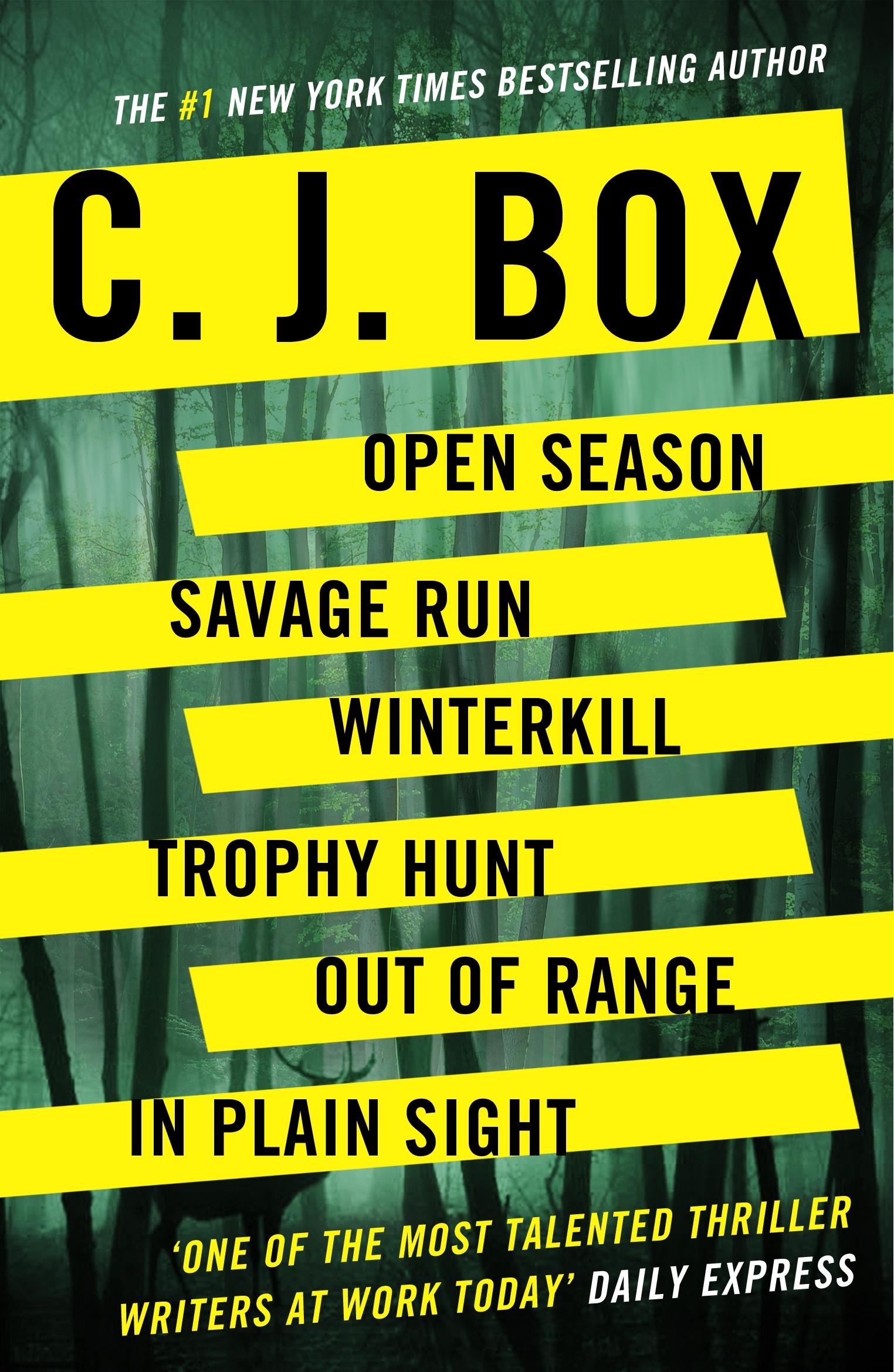

C. J. Box

Joe Pickett Series Bundle (Book 1-6)

PART ONE: Severe Winter Storm Warning

1. Twelve Sleep County, Wyoming

[Author Bio]

C. J. Box is the winner of an Anthony Award, the Prix Calibre .38, the Macavity Award, the Gumshoe Award, the Barry Award and the 2009 Edgar Award for Best Novel. His novels are US bestsellers and have been translated into 21 languages. Box lives with his family outside of Cheyenne, Wyoming.

[Copyright]

Published in ebook in Great Britain in 2019 Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © C. J. Box, 2011, 2012

The moral right of C. J. Box to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The novels in this anthology are entirely works of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author's imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 918 9

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26-27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

Open Season

[Dedication]

To Molly, Becky, Roxanne, and especially for Laurie – my partner, my anchor, my first reader, my love

And thanks to Andy Whelchel and Martha Bushko, who brought this to life

CONTENTS

-

PART ONE

-

Chapter 1

-

Chapter 2

-

Chapter 3

-

Chapter 4

-

-

PART TWO

-

Chapter 5

-

Chapter 6

-

Chapter 7

-

Chapter 8

-

Chapter 9

-

Chapter 10

-

-

PART THREE

-

Chapter 11

-

Chapter 12

-

Chapter 13

-

Chapter 14

-

Chapter 15

-

Chapter 16

-

Chapter 17

-

-

PART FOUR

-

Chapter 18

-

Chapter 19

-

Chapter 20

-

Chapter 21

-

Chapter 22

-

Chapter 23

-

-

PART FIVE

-

Chapter 24

-

Chapter 25

-

Chapter 26

-

Chapter 27

-

Chapter 28

-

Chapter 29

-

Chapter 30

-

Chapter 31

-

Chapter 32

-

Chapter 33

-

-

PART SIX

-

Chapter 34

-

Chapter 35

-

Chapter 36

-

Chapter 37

-

-

PART SEVEN

-

EPILOGUE

PART ONE

Findings, Purposes, and Policy

(b) Purposes. - The purposes of this Act are to provide a means whereby the ecosystems upon which endangered species and threatened species depend may be conserved, to provide a program for the conservation of such endangered species and threatened species, and to take such steps as may be appropriate to achieve the purposes of the treaties and conventions set forth in subsection(s) of this section.

—The Endangered Species Act Amendments of 1982

Printed for the use of the Senate Committee on

Environment and Public Works

US Government Printing Office

Washington: 1983

1

JOE LIVED, BUT it wasn’t something he was particularly proud of. It was now fall and Sunday morning dawned slate gray and cold. He was making pancakes for his girls when he first heard of the bloody beast who had come down from the mountains and tried to enter the house during the night.

Seven-year-old Sheridan Pickett related her dream aloud to the stuffed bear that served as her confidant. Lucy, three and horrified, listened in. The television set was on even though the reception from the vintage satellite dish was snowy and poor, as usual.

The monster, Sheridan said, had come down from the mountains through the dark, steep canyon behind the house very late last night. She watched it through a slit in the curtain on her window, just a few inches from the top bunk of her bed. The canyon was where Sheridan had always suspected a monster would come from, and she felt proud, if a bit fearful, that she had been right. The only light had been the moon through the dried leaves of the cottonwood tree. The monster had rattled the back gate before figuring out the latch and had then lurched clumsily (sort of like mummies in old movies) across the yard to the backdoor. Its eyes and teeth glinted yellow, and for a second, Sheridan felt an electric bolt jolt through her as the monster’s head swiveled around and seemed to looked directly at her before it fled. The monster was hairy and shiny, as if covered with liquid. Twigs and leaves were stuck to it. There was something white, a large sack or box, swinging from the monster’s hand.

“Sheridan, stop talking about monsters,” Joe called out. The dream disturbed him because the details were so precise. Sheridan’s dreams were usually more fantastic, inhabited by talking pets or magical things that flew. “You’re going to scare your little sister.”

“I’m already scared,” Lucy declared, pulling her blanket to her mouth.

“Then the man walked slowly away across the yard through the gate toward the woodpile where he fell down into a big shadow. And he’s still out there,” Sheridan finished, widening her eyes toward her sister to deliver the complete effect.

“Hold it, Sheridan,” Joe said abruptly, entering the room with a spatula in his hand. Joe was wearing his threadbare terry-cloth bathrobe he had purchased on a lark in Jackson Hole on his and Marybeth’s honeymoon ten years before. He shuffled in fleece slippers that were a size too large. “You said ‘man.’ You didn’t say ‘monster.’ You said ‘man.’ ”

Sheridan looked up quizzically, her big eyes wide. “Maybe it was a man. Maybe it wasn’t a dream after all.”

JOE HEARD A vehicle outside, racing up the gravel Bighorn Road much too fast, but by the time he crossed the living room and parted the faded drapes of the front picture window, the car or truck was gone. Dust rolled lazily down the road where it had been.

Beyond the window was the front yard, still green from summer and littered with plastic toys. Then there was the white fence, recently painted, paralleled by the gravel road. Farther, beyond the road, the landscape dipped into a willow-choked saddle where the Twelve Sleep River branched out into six fingers clogged with beaver ponds and brackish mosquito-heaven eddies and paused for a breath before its muscular rush through and past the town of Saddlestring. Beyond were the folds of the valley as it arched and suddenly climbed to form a precipitous mountain-face known as Wolf Mountain, a peak in the Twelve Sleep Range.

With Wolf Mountain in front of them and the foothills and canyon in back, the Pickett family, eight miles from town in their house, lived a life of deep and casting shadows.

The front door opened and Maxine burst in, followed by Marybeth. Marybeth’s cheeks were flushed—either from the brisk cold air or her long walk with the dog, Joe wasn’t sure which—and she looked annoyed. She wore her winter walking uniform of lightweight hiking boots, chinos, anorak, and wool hat. The anorak was stretched tight across her pregnant belly.

“It’s cold out there,” Marybeth said, peeling the hat off so her blond hair tumbled onto her shoulders. “Did you see that truck tear by here? That was Sheriff Barnum’s truck going too fast on that road up to the mountains.”

“Barnum?” Joe said, genuinely puzzled.

“And your dog was going nuts when we got back to the house. She nearly took my arm off just a minute ago.” Marybeth unclipped Maxine’s leash from her collar, and Maxine padded to her water dish and drank sloppily.

Joe had a blank expression on his face while he was thinking. The expression sometimes annoyed Marybeth, who was afraid people would think him simple. It was the same expression, in a photograph, that had been transmitted throughout the region via the Associated Press when Joe, while still a trainee, had arrested a tall man—who turned out to be the new governor of Wyoming—for fishing without a license.

“Where did Maxine want to go?” he asked.

“She wanted to go out back,” she said. “Toward the woodpile.”

Joe turned around. Sheridan and Lucy had paused at breakfast and were looking to him. Lucy looked away and resumed eating. Sheridan held his gaze, and she nodded triumphantly.

“Better take your gun,” Sheridan said.

Joe managed a grin. “Eat your breakfast,” he said.

“What’s this all about?” Marybeth asked.

“Bloody monsters,” Sheridan said, her eyes wide. “There’s a bloody monster in the woodpile.”

Suddenly, there was the roar of motors coming up Bighorn Road from Saddlestring. Joe was thinking exactly what Marybeth said next: “Something’s going on. I wonder why nobody called here?”

Joe lifted the telephone receiver to make sure it was working, the dial tone echoed clearly into his ear.

“Maybe it’s because you’re the new guy. People here still can’t get used to the fact that Vern Dunnegan isn’t around anymore,” Marybeth said, and Joe knew instantly she wished she could take it back.

“Dad, about that monster?” Sheridan said from the table, almost apologetic.

JOE BUCKLED HIS holster over his bathrobe, clamped on his black Stetson, and stepped outside onto the back porch. He was surprised how cool and crisp it was this early in the fall. When he saw the large spatters of dried blood between his oversized fleece slippers, the chill suddenly became more pronounced. Joe pulled his revolver and broke the cylinder to make sure it was loaded. Then he glanced over his shoulder.

Framed in the dining room window were Sheridan and Lucy. Marybeth stood behind them and off to the side. His three girls in the window were various stages of the same painfully beautiful blond and willowy female. Their green eyes were on him, and their faces were wide open. He knew how silly he must look. He couldn’t tell if they could see what he could: splashes of blood on the ancient concrete walkway that halved the yard and crushed frozen grass where it appeared that someone—or something—had rolled. It looked almost like the night nesting place of a large deer or elk the way the grass and crisp autumn leaves had been flattened.

Grasping the pistol in front of him with both hands, Joe skirted a young pine and stepped through the open gate of the weathered fence to the place where the woodpile was.

Joe sucked in his breath and involuntarily stepped back, his ears filled with the whumping sound of his own heart beating.

A big, bearded man was sprawled across the woodpile, both of his large hands folded across his belly, palms down, and one leg cocked over a stump. The man’s head rested on a log, his mouth parted just enough to show two rows of yellow teeth that looked like corn on the cob. His eyelids weren’t completely shut, and where there should have been a moist reflection from his eyes there was instead a dull, dry membrane that looked like crinkled cellophane. His long hair and full beard was matted by blood into crude dreadlocks. The man wore a thick beige chamois shirt and jeans, and broad stripes of dark blood had coursed down both. It was Ote Keeley, and Ote looked dead.

Joe reached out and touched Ote’s meaty, pale white hand. The skin was cold and did not give to the touch. Except for the dried blood in his hair and on his clothes and his waxy skin, Ote looked to be very comfortable. He could have been reclining in his La-Z-Boy, having a beer and watching the Bronco game on television.

Clutched in one of Ote Keeley’s hands was the handle of a small plastic cooler minus the lid. Joe kneeled down and looked into the cooler, which was empty except for a scatter of small teardrop-shaped animal excrement. The inside walls of the cooler were scratched and scarred, as if clawed. Whatever had been in there had been manic about getting out, and it had succeeded.

Joe stood and saw the extra buckskin horse standing near the corral. The horse was saddled, and the reins hung down from the bridle. The horse had been ridden hard and had lost enough weight that the cinch slipped and the saddle hung loose and upside down.

Joe stared at Ote’s blank face, recalling that day in June when Ote had pointed Joe’s own pistol at his face and cocked the hammer. Even though Ote had thought better of it and had sighed theatrically and spun the weapon around butt-first with his finger in the trigger guard like the Lone Ranger, Joe had never quite been the same. He had been expecting to die at that moment, and for all practical purposes he deserved to die, having given up his weapon so stupidly. But it hadn’t happened. Joe had holstered his revolver with his hands shaking so badly that the barrel of the revolver rattled around the mouth of the holster. His knees had been so weak that he backed up against his pickup to brace himself so he wouldn’t collapse. Ote had simply watched him with a bemused expression on his face. Without a word, Joe had written out the citation for poaching in a shaking scrawl and handed the ticket to Ote Keeley, who took it and stuffed it in his pocket without even looking at it.

“I won’t say nothin’ if you don’t about what just happened,” Ote had said.

Joe hadn’t acknowledged the offer, but he hadn’t arrested Ote either. The deal had been struck: Ote’s silence in exchange for Joe’s life and career. It was a deal Joe agonized over later, usually late at night. Ote Keeley had taken something from him that he could never get back. In a way, Ote Keeley had killed Joe, just a little bit. Joe hated him for that, although he never said a word to anyone except Marybeth. What made it worse was when word of the incident filtered out anyway.

During the summer Ote had gotten drunk and told everyone at the bar what had happened. The story about the new game warden losing his weapon to a local outfitter had joyously made the rounds, and it even appeared in the wicked anonymous column “Ranch Gossip” that ran in the weekly Saddlestring Roundup. It was the kind of story the locals loved. In the latest version, Joe had lost control of his sphincter and had begged Ote for the gun back. Joe’s supervisor in Cheyenne heard the rumors and had called Joe. Joe confirmed what had actually happened. In spite of Joe’s explanation, the supervisor sent Joe a reprimand that would stay in his personnel file forever. An investigation was still possible.

Keeley’s poaching trial date had been set to take place in two weeks, but obviously Ote wouldn’t be appearing.

Ote Keeley was the first dead person Joe had ever seen except in a coffin at a funeral. There was nothing alive or real about Ote’s expression. He did not look happy, puzzled, sad, or in pain. The look on his face—frozen by death and for several hours—told Joe nothing about what Ote was thinking or feeling when he died. Joe fought an urge to reach up and close Ote’s eyes and mouth, to make him look more like he was sleeping. Joe had seen a lot of dead big game animals, but only the stillness and the salt-ripe odor was the same. When he saw dead animals, he had many different emotions, depending on the circumstances—from indifference to pity and sometimes to quiet rage aimed at careless hunters. This was different, Joe thought, because the dead body was human and could be him. Joe made himself stop staring.

Joe stood up. There had been a monster.

He heard something and turned around.

The backdoor slammed shut, and Sheridan was coming out in her nightgown, skipping down the walk with her hands in the air to see what he had found.

“Get BACK into that house!” Joe commanded with such unexpected force that Sheridan spun on her bare feet and flew right back inside.

On his way through the house and to the phone, Joe told Marybeth who the dead man was.

2

OF COURSE, COUNTY Sheriff O. R. “Bud” Barnum wasn’t in when Joe called the dispatch center in Saddlestring. According to the dispatcher—a chain-smoking conspiracy buff named Wendy—neither was Deputy McLanahan. Both, she said, had responded to an emergency that morning in a Forest Service campground in the mountains.

“Some campers reported seeing a wounded man on horseback ride straight through their camp last night,” Wendy told Joe. “They said the suspect allegedly rode his horse right through their camp while displaying a weapon and threatening the campers with said weapon.”

Joe could tell that Wendy loved this situation, loved being in the center of the action, loved telling Joe about it, loved saying things like “allegedly” and “said weapon.” She did not get a chance to use those words often in Twelve Sleep County.

“I called out the entire sheriff’s office and both emergency medical vehicles at seven-twelve A.M. this morning to respond.”

“Did you get a description of the man on horseback?” Joe asked.

Wendy paused on the telephone, then read from the report: “Late thirties, wearing a beard, bloody shirt. A big man. Crazy eyes, they said. The suspect was allegedly swinging some kind of plastic box or cooler around.”

Joe leaned his chair back so he could see out of the small room near the front door that served as his office. Both girls were still lined up at the back window, looking out. Marybeth hovered behind them, trying to draw their attention away by rattling a box of pretzels the same way she would shake dog biscuits at Maxine to get her to come into the house.

“Why wasn’t I called?” Joe inquired calmly. “I live on the Bighorn Road.”

There was no response. Finally: “I never even thought about it.”

Joe recalled what Marybeth had said about Vern Dunnegan but said nothing.

“Sheriff Barnum didn’t mention it neither,” Wendy said defensively.

“The injured man was displaying and threatening a weapon with one hand and swinging a plastic box with the other?” Joe asked. “How did he steer his horse?”

“That’s what the report says.” Wendy sniffed. “That’s what the campers reported. They was out-of-staters. From Massachusetts or Boston or some place like that.” She said the last part as if it explained away the inconsistency.

“Which campground?” Joe persisted.

“It says here they was at Crazy Woman Creek.”

Crazy Woman was the last developed U.S. Forest Service campground on Bighorn Road, a place generally used as a jumping-off site for hikers and horse-packers entering the mountains.

“Are you in radio contact with Sheriff Barnum?” Joe asked.

“I believe so.”

“Why don’t you give him a call and let him know that the man on horseback was Ote Keeley and that Ote is lying dead on the woodpile behind my house.”

Joe could hear Wendy gasp, then try to regain her composure.

“Say again?” she replied.

JOE HUNG UP the telephone and started for the backdoor.

“You’re not going back out there?” Sheridan whispered.

“Just for a minute,” Joe said in what he hoped was a reassuring tone.

He shut the door behind him and slowly walked toward the body of Ote Keeley, his eyes sweeping across the yard, taking in the bloodstained walk, the woodpile, the canyon mouth behind the house. He wanted a clear picture of everything as it was right now, before the sheriff and deputies arrived. He didn’t want to screw up again.

Squatting near the plastic cooler, Joe drew two empty envelopes and a pencil from the pocket on his robe. Using the tip of the eraser, Joe flicked several small pieces of scat from the cooler into an envelope. He would send that to headquarters for analysis. He gathered several more pieces of scat and put them in another envelope. He sealed both and put them back in his pocket. He left the rest for the sheriff.

Back in the house, Joe dressed in his day-to-day uniform: blue jeans and his red, button-up chamois shirt with the pronghorn antelope patch on the sleeve. Over the breast pocket was his name plate, which read GAME WARDEN and under that J. PICKETT.

When he came downstairs, the girls were sprawled in front of the snowy television, and Marybeth was sitting at the table flanked by dirty dishes. She held a big mug of coffee in her hands and stared at something in the air between them.

Her eyes raised until they met Joe’s.

“It’ll be okay,” Joe said, forcing a smile. He asked Marybeth to gather up the children and some clothes and go into Saddlestring. They could check into a motel until this was over and the backyard was cleaned up. He didn’t want the kids seeing the dead man. Sheridan’s dreams were already vivid enough.

“Joe, who will pay for the room? Will the state pay for it?” Marybeth asked softly so the children couldn’t hear.

“You mean we can’t?” Joe replied, incredulous. She shook her head no. Marybeth kept the meager family budget under a tight rein. It was the end of the month. She would know if they were broke, and apparently that was the case. Joe felt his face flush. Maybe they could stay with somebody? Joe dismissed that. While they had made a few friends in town, they were still new, and he didn’t know who they could call to ask this kind of favor.

“Can we use the credit card?” he asked.

“Nearly maxed out.” She said. “It might work for a night or two, though.”

He felt another wave of heat wash up his neck.

“I’m sorry, honey,” he mumbled. He fitted his dusty black hat on his head and went outside to wait.

3

AFTER MEASURING, MARKING, and photographing, the deputies sealed off the woodpile with yellow CRIME SCENE tape and unfurled a body bag.

Joe stationed himself outside with his back to the window so no one who looked out could see the deputies bend Ote Keeley into the bag, folding his stiff arms and legs inside so they could zip it up and carry it away. Ote was heavy, and the middle part of the bag hummed along the top of the grass as the deputies took the body out of the yard and around the side of the house to the ambulance.

Sheriff O. R. “Bud” Barnum had arrived first and had briskly ordered Joe to show him where Ote Keeley’s body was. Despite his age, Barnum still moved with speed and stiff grace. His pale blue eyes were set in a pallid leather face and rimmed with paper-thin flaps of skin. Joe watched as the blue eyes swept the scene.

Joe had expected questions and was prepared for them. He informed Barnum that he had gathered the scat evidence to send to headquarters, but Barnum had waved him off.

“Yup, that’s Ote all right,” Barnum had said, before returning to his Blazer. “You’ll write up a report on it?” Joe nodded yes. That was all there was. No questions, no notes. Joe was surprised and felt useless.

From the side of the house, Joe observed the sheriff as he held the mike of his police scanner to his mouth with one hand and gestured in the air with the other. By his movements, Joe could tell that Barnum was becoming frustrated with somebody or something. So was Joe, but he tried not to show it.

Joe went inside the house. Marybeth watched him nervously from her place on the couch.

“Is it gone?” she asked, referring to the body. She didn’t want to say Ote’s name.

Joe assured her that it was.

She was pale, Joe noticed. Her face was drawn tight. Marybeth rubbed her hand across her extended belly. She didn’t realize she was doing it. He remembered the gesture from before, when she was pregnant with Sheridan and then Lucy. It was something she did when she felt that things were on the verge of chaos. She held her arms across her unborn baby as if to shield it from whatever unpleasantness was happening outside. Marybeth was a good mother, Joe thought, and she reared the children with care. She resented it when outside events intruded on her family without her prior consent, permission, or planning.

“He’s the guy who took your gun a while back,” Marybeth said with dawning realization. “I’ve met his wife. In the obstetrician’s office. She’s at least five months along also.” She grimaced. “They have a little one about Sheridan’s age and I think one younger. Those poor kids ...”

Joe nodded and poured some coffee in a mug to deliver to Sheriff Barnum out in his Blazer.

“I just wish it wouldn’t have happened here,” Marybeth said. “I know these things happen but why did he have to come here, to our house? Right to our house?”

It’s not our house, Joe said to himself. It belongs to the State of Wyoming. We just live here. But Joe didn’t say that and instead went out the front door after a quick “I’ll be right back.”

Barnum was signing off from a conversation, and he angrily hung up the microphone in its cradle on the dashboard. Joe handed him the cup of coffee, and Barnum took it without a word.

“What we know so far is that Keeley went into the mountains with two other guides to scout for elk and set up their camp last Thursday,” Barnum said, not looking directly at Joe. “They have an outfitters camp up there somewhere. They weren’t expected back until tomorrow so nobody had missed them yet.”

“Who were the other guides?” Joe asked.

“Kyle Lensegrav and Calvin Mendes,” Barnum replied, finally looking at him. “You know ’em?”

Joe nodded. “I’ve run into them a few times. Their names have come up along with Ote Keeley’s in connection with a poaching ring. But nobody’s caught them doing anything as far as I know.” Joe had once had a beer in the Stockman Bar with both of them. They were both in their mid-thirties, and both mountain-man throwback types. Lensegrav was tall and thin, and he wore thick glasses mounted on a hooked nose. He had a scraggle of blond beard. Mendes was short and stout, with dark eyes and a charming, flashbulb smile. Pickett had heard that Mendes and Ote Keeley had been in the army together and that they had both served in Desert Storm.

“Well, nobody’s seen Lensegrav or Mendes,” Barnum continued. “My guess is that they’re trying like hell to get out of state because they shot their good old pal Ote Keeley right in the chest a couple of times, for whatever reason.”

“Or they’re still up in the mountains,” Joe said.

“Yup.” Barnum paused, pursing his lips. “Or that. The word is out to the Highway Patrol statewide to watch out for ’em. Problem is I don’t know yet what they’re driving. Keeley’s truck and horse trailer are up at Crazy Woman Creek where they left it. We’re trying to find out if one of them took a vehicle up there as well.”

Joe nodded at Barnum and said “Hmmmm.” There was an uncomfortable minute of silence.

Sheriff Barnum was an institution in Twelve Sleep County, and he had been in office for 24 years. He rarely had opposition when he ran for election, and in the few times he had, he’d taken 70 percent of the vote. He was a hands-on sheriff, involved in everything from civic organizations to officiating at high school football and basketball games. He knew everybody in the county, and they in turn knew and respected him. Very little got by Sheriff Barnum. Over the years, he had become a storied and colorful character. Specific incidents had become legend. He had put a .357 Magnum bullet into the eyebrow of a ranch foreman who had just used an irrigation shovel to bludgeon to death his own mother, brother, and a Mexican hired hand. He had taken Polaroid snapshots of cows who had apparently been mutilated by alien beings who had arrived on earth in cigar-shaped flying objects. He had arrested a Basque sheepherder in his sheep wagon and confiscated a ewe named Maria that had been dyed pink. He had once turned back two dozen Hell’s Angels en route to Sturgis, South Dakota, by firing up a 24-inch chainsaw while straddling the yellow line on the highway.

“Your office should have called me this morning,” Joe said abruptly. “I was closer to the scene than anyone else.”

Barnum sipped the coffee and squinted at Joe as if sizing Joe up for the first time.

“You’re right,” Barnum answered. Then: “Wasn’t it Ote Keeley who took your gun away from you while you were giving him a citation?”

“Yes, it was,” Joe replied, feeling his ears flush hot.

“Strange he came here,” Barnum said.

Joe nodded.

“Maybe he wanted to take your gun away from you again.” Barnum smiled crookedly to show he was joking. Barnum was wily, no doubt about it. Joe hardly knew the sheriff, but Barnum had already tweaked one of his weak spots. There was a moment of hesitation before Joe asked if Barnum planned to investigate the elk hunting camp.

“I would, but right now I’m screwed,” Barnum said, banging the dashboard with his fist. “That camp is in a roadless area so we can’t get to it. Our chopper’s on loan to the Forest Service so they can fight that fire down in the Medicine Bow Forest. Tomorrow night’s the earliest we could get it back.

“And my horse posse guys are all in the mountains already because they’re all gettin’ ready to go hunting.” Barnum looked over at Joe, exasperated. “We can’t get to that camp unless we hoof it, and I’m not walking.”

Joe thought it over for a moment. “I know a guy who knows where that elk camp is located, and I’ve got a couple of horses.”

Barnum began to object, then caught himself.

“Well, I don’t see why not, since you’re volunteering. How soon could you get going?”

Joe rubbed his jaw. “This afternoon. I’ve got to fetch my horse trailer and get outfitted, but I’m pretty sure I could get on the trail by about two or three.”

“Take my guy McLanahan,” Barnum said. “I’ll get on the radio and tell him to grab his saddle and some heavy artillery and get his lazy butt out here. You guys might run into some bad business up there, and I want to make sure you’ve got ’em outgunned.”

Barnum grabbed his microphone but halted before he spoke into it.

“Who is it who knows where that hunting camp is?” Barnum asked.

“Wacey Hedeman,” Joe replied.

“Wacey Hedeman?” Barnum hissed. “He’s declared that he’s going to run against me in the next election, that blow-dried son of a bitch.”

Joe shrugged. Wacey was the game warden in the next district but had patrolled in the Twelve Sleep area temporarily after Vern left and before Joe was assigned the position. Wacey had once mapped out all of the licensed outfitters’ elk camps along the Crazy Woman drainage.

“Goddamnit,” Barnum spat vehemently. “I hate it when things turn cowboy.”

Barnum cursed again, then turned away to radio his dispatcher.

WACEY DIDN’T ANSWER the telephone in his home office and didn’t respond to the radio call, but Joe had a good idea where to find him. Before he left in the truck to find Wacey, he kissed Marybeth and his girls goodbye. Lucy gave him a bored kiss. She didn’t approve of him leaving the house at any time for any reason, and this was how she showed it. Because she was so much younger and was wise beyond her years—she had absorbed, as if by osmosis, many of the lessons her older sister had learned the hard way—Joe often treated Lucy as a fellow adult conspirator, fighting the many emerging pre-adolescent forces of her animated older sister.

Sheridan and Lucy were confused by why they had to leave their house. Marybeth was telling them how exciting it would be to stay in a motel, but they weren’t yet convinced.

Joe stopped at the door and turned back. Sheridan was watching him closely.

“You okay, honey?” Joe asked her.

“I’m okay, Dad.”

“Next time you say you see a monster, I’m going to believe you.”

“Okay, Dad.”

“You remember who’s coming tomorrow night, don’t you?” Marybeth asked.

He had not thought about it at all with everything that had happened that morning.

“Your mother.”

“My mother,” Marybeth echoed. “So we’ll be back in the house by then. Hopefully, you will, too.”

Joe grimaced.

4

WHILE HER MOTHER packed a suitcase in the bedroom, Sheridan did exactly what she had been told not to do and went to the dining room window to watch. However, before she did, she made sure that Lucy was still wrapped in her blanket on the floor watching television. Lucy would gladly tell on her older sister.

The man her dad called Sheriff Barnum stood in the yard near the woodpile, and another man wearing the same kind of policemen’s uniform—he was younger than Sheriff Barnum but still old, like her dad—stood near him. The sheriff stood with his back to the woodpile, pointing toward the mountains and talking. His arm swept along the top of the mountains and up the road, and the younger man’s eyes followed the gesture. Sheridan couldn’t hear what the sheriff was saying. At one point, the sheriff walked from the woodpile to the house. He stopped squarely in front of Sheridan at the window, and Sheridan was too scared to move. Over his shoulder, to the other man, the sheriff called out the number of paces he had measured. Before turning back, he had looked down and grinned at her. It had been a kind of “get out of my way, kid” smile. Sheridan wasn’t sure she liked Sheriff Barnum. She didn’t like his pale eyes. She didn’t like cigarettes, either, and even through the screen in the window she could smell them on his uniform.

As Sheriff Barnum returned to the woodpile, Sheridan thought about how surprised she was that this thing had happened. How could it be that what she had thought the night before was a monster from her “overactive imagination” (as her mom called it) had turned out to be real? It was as if her dream world and the real world had merged for this event. Suddenly, adults were involved. She had had a strange notion: what if her imagination was so powerful that she could dream things into existence?

But she decided this wasn’t the case. If it was, she would have brought forth something much nicer than this. Like a pet—a real pet of her own.

Sheriff Barnum took a pack of cigarettes out of his shirt pocket, shook them, and flipped one up into his mouth. It was a neat trick, she thought. She had never seen it before. The man with Sheriff Barnum reached over and lighted the sheriff’s cigarette for him. A great roll of white smoke grew around the sheriff’s head.

Sheridan wore her glasses. She wished now she would have had her glasses on the night before, so she could have seen the man’s face in detail when he looked at her. If she would have seen him clearly, she would have trusted her own mind over her imagination and run to her parents’ room instead of convincing herself that she had a nightmare about monsters coming down from the mountains.

She loved that she could see clearly now but hated the fact that she was the only student in her class who had to wear glasses. Her first day of school at Twelve Sleep Elementary was also her first day wearing glasses. She would never forget how tall she seemed to be when she looked down or how awkward she felt when she walked. The chalkboard and the words on it were in such sharp focus that they hurt her eyes. It was bad enough that she was one of the new girls in school, and the rude girls had already grouped her into a category called “Weird Country” that was made up of students who lived out of town. Or that she could already read books and say poetry she had memorized while they struggled with sentences. But on top of all of that, she also had to show up wearing glasses.

And she was the new game warden’s daughter in a place where the local game warden was a big deal because nearly everyone’s dad hunted. It was understood that Sheridan’s dad could put others in jail. So far, in the two weeks since school had begun, she had absolutely no friends in the second-grade class.

Sheridan’s only friends were her animals, had been her animals, and they had all disappeared. The loss of her cat, Jasmine, had devastated her. She had cried and prayed for Jasmine to come back, but she didn’t. She begged her parents for another pet to love, but they said she would have to wait until she got a little older. They told her she would have to get a fish or a bird in a cage, something that didn’t go outside or into the hills behind the house. She had overheard her dad telling her mom about coyotes (although she wasn’t supposed to know), and she had figured out that her cat Jasmine had been eaten. Just like her puppy before that. But while those pets were nice, they weren’t what she needed. She wanted a pet to cuddle with. She wished she had a secret pet, one that neither her parents, the rude girls at school, or the coyotes knew about. A secret pet that was just hers. A pet she could love and who would love her for who she was: a lonely girl who had moved from place to place before she could make friends and who had a little sister who was too adorable for words and a baby on the way who would command most of her parents’ love and attention for ... maybe forever.

Then she saw something outside that quickly brought her back to earth. Something had moved in the woodpile; something tan and lightning fast had streaked across the bottom row of logs and darted into a dark opening near the base between two lengths of wood.

The sheriff and the younger man were still talking, and they had their backs to the fence and the woodpile. What she had seen was just behind them, only a few feet away, but it didn’t look like they had noticed anything. They hadn’t even turned around. She could see nothing now. A ground squirrel? Too big. A marmot? Too sleek and fast. She had never seen this kind of animal before, and she knew every inch of that yard and every creature in it. She even knew where the nest of tiny field mice was and had studied the wriggling pink naked mouse babies before their eyes opened. But this animal was long and thin, and it moved like a bolt of lightning.

Sheridan gasped and jumped when her Mom spoke her name sharply behind her. Sheridan turned around quickly but her mom was looking sternly at her and not at the woodpile through the window. Sheridan didn’t say a word when her mom guided her away from the window, through the house, and to the car.

As her mom backed out of the driveway and Lucy sang a nonsense song, Sheridan watched over her shoulder through the back car window as the house got smaller. As they crested the first hill toward town, the little house was the size of a matchbox.

Behind the matchbox house, Sheridan thought, was a woodpile. And in that woodpile was the gift her imagination had brought her.

PART TWO

Determination of Endangered Species and Threatened Species

Sec. 4. (a) General. - (1) The Secretary shall by regulation promulgated in accordance with subsection (b) determine whether any species is an endangered species or a threatened species because of any of the following factors:

[(1)] (A) the present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of its habitat or range;

[(2)] (B) overutilization for commercial, [sporting,] recreational, scientific, or educational purposes;

[(3)] (C) disease or predation;

[(4)] (D) the inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms;

or

[(5)] (E) other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence.

—The Endangered Species Act Amendments of 1982

5

THERE WERE 55 game wardens in the State of Wyoming, an elite group, and Joe Pickett and Wacey were two of them. Wacey had received his B.A. in wildlife management while bull-riding at summer rodeos before Joe had graduated with a degree in natural resource management. Three years apart, both had been certified at the state law enforcement academy in Douglas and both had passed the written and oral interviews, as well as the personality profile, to become permanent trainees in Jeffrey City and Gillette districts respectively, before becoming wardens. Each now made barely $26,000 a year.

As Joe drove down the two-lane highway toward the Eagle Mountain Club, he thought of how the morning had violently changed course. Ote Keeley had ridden down from the mountains in the middle of the Pickett family Sunday routine. It was a routine that had moved with them as they relocated throughout the state. It continued to Baggs in Southern Wyoming, then to Saddlestring as he worked under the high-profile Game Warden Vern Dunnegan, then to Buffalo when Joe took on his first full-fledged post as game warden. There had been six different state-owned houses in nine years, five different towns. All of the homes—and especially this one—had been plebeian and small. They were careful at headquarters not to give the taxpayers the idea that their hunting license fees were going toward elaborate homes for state employees. The Pickett house was built into the mouth of a small canyon on a lot that included a barn, a corral, and a detached garage. They had brought their family routine back to Saddlestring district after Vern suddenly retired from the state and Joe finally got the job he wanted most, in the place he and Marybeth liked the best.

It was a job Joe almost didn’t get. Vern had recommended Joe and had used his influence at headquarters to get Joe an interview with the director. In what Joe and Marybeth later called “one his larger bonehead moves,” Joe had written the wrong date for the appointment with the director in his calendar and simply missed it. When Joe screwed up, he tended to do it massively and publicly. The director had been furious for being stood up and it was only through Vern’s intervention that Joe was able to later meet with the director and secure the post.

Both Marybeth and Joe had commented how much bigger the house had seemed to be when Vern and his wife occupied it, back when Joe worked under Vern and he and Marybeth would visit. They both remembered sitting in the shaded backyard, sipping cocktails while Vern barbecued steaks and Vern’s attractive wife, Georgia (they had no children), mixed drinks and tossed salad inside. The house at that time seemed almost elegant in a way, and both Joe and Marybeth were envious. The future seemed so bright then. But that was two children and a Labrador ago, and the same three-bedroom home was filled. After only four months in the house it seemed to be shrinking. The baby would make the house even smaller. And everything about it was falling apart. The shelf life for a state-owned and -constructed home was short.

Today was, he knew, likely to be the last Sunday for at least three months that he would be able to cook breakfast for his girls and read the newspapers—and now he hadn’t even been able to do that. Big game hunting season in Twelve Sleep County, Wyoming, would begin on Thursday with antelope season. Deer would follow, then elk and moose. Joe would be out in the mountains and foothills, patrolling. School would even be let out for “Elk Day” because the children of hunters were expected to go with their families into the mountains.

Hunters began before dawn, and Joe would begin before dawn. Hunters could legally take game up to a half an hour after dark, and Joe would be out among them until well after that, checking permits and licenses, making sure that the game was tagged properly, that laws weren’t broken, and that private land wasn’t trespassed on. In Wyoming, the people owned the game animals, and they took their ownership to heart. Joe took his job just as seriously.

He thought about Sheridan saying “Better take your gun,” and it bothered him. Sheridan had certainly noticed his Sam Browne belt and the pistol in it when he came home every night. His .270 Winchester rifle rested permanently in the window gun rack of the department green Ford pickup he drove. They knew that his job entailed carrying a gun with him. But never had either child ever suggested he go out and shoot something. Maybe they didn’t realize what he really did all day. He had heard Sheridan say in passing that her Dad “saved animals” for his job. He liked that definition, even though it was only partially true.

Joe slowed on the highway to let a herd of pronghorn antelope cross. He watched as they ducked under a barbed-wire fence and continued their journey toward the foothills, toward Wacey Hedeman’s district.

Wacey and Joe had both been trained in the field by Vern Dunnegan at different times. Vern told anyone who would listen that they were his “best boys.” Because their districts adjoined each other—the warden in the Saddlestring district and the warden in the Basin district—Wacey and Joe often teamed up on projects and investigations. They built hay fences together, shared horses and snow machines when needed for patrol, called on each other for support if necessary, and traded notes. As a result of spending many predawn hours together in one or the other’s trucks, Joe had come to know Wacey well. They had even become friends, of a sort. Wacey fascinated Joe at the same time he repelled him. Wacey knew the county and was intimate with ranchers and poachers alike. Wacey was an ex–rodeo cowboy who had an easy, oily charm that worked on just about everyone, Joe included. Even Marybeth seemed to enjoy Wacey, although she startled Joe once by saying that she didn’t trust him.

Some of the things Joe knew about Wacey would have confirmed her opinion, but he kept them to himself.

JOE TURNED HIS pickup off of the highway into the entrance of the Eagle Mountain Club. A uniformed guard in a white clapboard guardhouse waved at him to go through, and the motorized wrought-iron gate swung wide. But as Joe drove forward, the guard suddenly swung out of the door of the house and approached his window.

The guard was in his late fifties, and his uniform strained across his belly.

“I thought you were somebody else when I waved at you,” the guard said, bending his head to the side so he could see into the truck.

“You thought I was Wacey Hedeman,” Joe said. “He has a truck just like this. I’m here to see Wacey.”

The guard stared hard at Joe. “Have you been here before?”

“Once, with Wacey.” Joe let his voice drop. “Now please let me through now. There was a homicide near Saddlestring, and I need Wacey’s help on it now.”

The guard stepped back but took a moment to wave Pickett through. In his rearview mirror, Joe watched the guard step into the road and write down Joe’s license plate number on a pad he took from his pocket.

The Eagle Mountain Club was an exclusive private resort on a hilltop overlooking the Bighorn Mountains. From what Wacey had told him, initial dues to the club were $250,000 and members joined by invitation only. The Eagle Mountain Club had only 250 members, and new members joined only when old members died, dropped out, or were denied privileges by a majority of the members. This had happened only twice to Joe’s knowledge, once to the famous televangelist who “baptized” a housekeeper by inserting the neck of a vodka bottle into her and then dunking her in the club-stocked trout pond and the other time when a member, a former astronaut, was found guilty of beating his wife to death with a bronze replica of the Lunar Landing Module. The club had a 36-hole golf course that fingered through the foothills of the Bighorn Mountains, as well as a private fish hatchery, shooting range, airstrip, and about 60 multimillion-dollar homes that had been constructed when a million dollars was an obscene amount of money. The one thing the exclusive membership had in common was a passion for privacy. Few people in the state even knew about the Eagle Mountain Club, and access to it was purposely difficult. It was more than 200 miles from the nearest city of any size—Billings, Montana—and more than 500 miles from Denver.

The Eagle Mountain Club was nearly vacant in the fall, and Joe encountered no vehicles or golf carts on the road. Few residents stayed during the winter, and most were already gone. As he drove along the wide empty roads bordered by manicured lawns with the Bighorns looming all around him, Joe got the sense of being on top of the country that spread out around him. It was a false oasis hidden away on a mountaintop in Wyoming, a high and dry place where the grass grew only because of nonstop, unrepentant irrigation and where all of the food in the four-star restaurant was flown in from other places. Joe felt that this place didn’t belong, and he knew it was there for precisely that reason. The Eagle Mountain Club predated the recent flight to the Rocky Mountains by rich celebrities by about 30 years.

Homes were set back off of the road, and most were hidden by trees. There were no street signs, and driveways to homes were marked by brass plaques imbedded in the pavement with the owners’ last names. When he saw the name Kensinger, he turned.

Wacey’s muddy green Ford pickup was parked at a rakish angle on the side of the massive two-level log home. Joe parked behind it and got out. His footsteps on the pavement were the only sound he could hear. Joe knocked on the door.

The wide oak front door swung open, and Wacey stood in it and squinted at Joe with a sour expression on his face. Wacey was still thin and compact—a bull-rider’s body—and his mouth was hidden under a thick auburn gunfighter’s mustache. The only thing he was wearing was his red chamois Game and Fish shirt.

“Take your pants off and come on in, Joe,” Wacey said in a whisper. “That’s what I did.” A slow full-face grin started near his corners of his blue eyes.

Someone inside the dark house, a woman, asked Wacey what he was doing.

“My colleague Joe Pickett from the Saddlestring District is here,” Wacey said over his shoulder. “I’ll just be a minute.”

Behind Wacey, in the gloom, Joe saw the form of a very white and naked woman pass. He heard her bare feet slap across the marble floor.

To Joe, Wacey mouthed the name “Aimee Kensinger.” Then: “She really does like us wardens.”

Despite himself, Joe smiled. Wacey was something else. Wacey had once told Joe that Aimee Kensinger, the trophy wife of Donald Kensinger of Kensinger Communications, had a thing for cowboy-types in uniform. Joe knew Wacey had been spending a lot of time of late at the Eagle Mountain Club. He also knew that Wacey’s visits coincided with Donald Kensinger’s business trips.

Wacey stepped out on the porch and eased the door closed behind him.

“What’s going on?” Wacey asked. “I was right in the middle of something.”

Joe knew what. There was a wet stain on the front tail of Hedeman’s shirt where his erection stretched out at the fabric like a tent pole. Hedeman followed Joe’s eyes.

“That’s kinda embarrassing,” Wacey said. “Guess I’m leakin’ a bit. She’ll make a guy do things like that when they aren’t used to it.”

Joe Pickett told Wacey what had happened that morning. He confirmed that Wacey did know where Ote Keeley’s elk camp was located on the Twelve Sleep Drainage. He told Wacey about the cooler, and Wacey seemed interested.

“Ote Keeley. He was that guy ...”

“Yup,” Joe answered sharply.

“When do we need to get going?” Wacey asked.

“Right now,” Joe said. “Right now.”

“I gotta call Arlene,” Wacey replied, referring to his wife.

“Maybe you ought to do it from the truck.”

Wacey again started his slow, infectious smile. He winked at Joe and nodded his head toward the door.

“She’s gonna finance my campaign for sheriff,” Wacey said in a conspiratorial voice. “And when it comes to sex, she’ll try just about anything. She even shaved herself this morning. You ever mess around with a woman who is shaved clean as a whistle? It’s weird. Sort of like a little girl, but not a little girl at all, you know? You just don’t realize how big and ripe those lips are down there unless you can really see ’em.”

Joe nodded uncomfortably.

Aimee Kensinger came out of the house wearing a thick white robe.

Joe said hello. He had met her once at a museum fundraiser dinner Marybeth had taken him to, but he knew she didn’t remember him. He hadn’t been in his uniform.

“Hello, officer,” Aimee Kensinger said. It was a purr, a self-conscious, very obvious purr. Joe was both alarmed and aroused.

Aimee Kensinger had a wide-open healthy face framed by a bell of dark hair. Her feet were bare and her calves were trim. She wore no makeup, but her face was still flushed from whatever Wacey and she had been doing inside.

“Forget it, babe.” Wacey said gently to her, giving her a brotherly punch on the arm. “He’s married.”

“So are you, honey,” she said.

“It’s different with Joe, though,” Wacey answered, shrugging as if he couldn’t understand it himself.

“Good for you,” she said. Joe couldn’t tell if she meant it or not.

6

THE COMMAND POST that had been established at the Crazy Woman Creek Campground had quickly become chaos. The murder of Ote Keeley and the possibility of an armed camp of suspects had ignited the imagination of the entire valley. A crowd had formed in the campground including off-duty Saddlestring police officers, volunteer fire department members, the mayor, the editor of the weekly Saddlestring Roundup, even elderly officers of the local VFW armed with Korean War–era M-1 carbines. Two local survivalists had shown up in battle fatigues with specially modified SKS Chinese assault rifles and concussion grenades hung from web belts. Sheriff Barnum didn’t mind the crowd; he reveled in it. His makeshift office was established in a stout-walled Cabela’s outfitter tent. His desk was a card table. Someone (Joe guessed one of the Korean War vets) told him that when he sat at the table and smoked, he reminded them of General Ulysses S. Grant at Shiloh. Barnum enjoyed the comparison and mentioned it to anyone who would listen.

Joe Pickett and Wacey Hedeman saddled their horses and shook the hands of well-wishers while they waited for Deputy McLanahan to arrive. Joe had brought up his six-year-old buckskin mare named Lizzie. Joe felt like he and Wacey were star athletes of the local football team. Men clapped them on their shoulders and whacked them on the butt as they walked by. Many said they wished they were going along.

McLanahan arrived armed for a small war, and the gear he had brought would have been fine if the three of them were setting off on a land offensive with four-wheel drives and transport trucks. Unfortunately for McLanahan, this was a designated roadless area of the national forest and the only access was by foot or horseback. In his Blazer and horse trailer, McLanahan had brought hundreds of pounds of bulky outfitter tents, sleeping bags, a propane stove, blankets, cast-iron skillets, Dutch ovens and frying pans, radio equipment and a chuck box filled with plates and utensils that weighed more than 150 pounds by itself. The back of the Blazer was stacked with guns—Joe imagined McLanahan cleaned out the gun cabinet in the sheriff’s office. He saw several high-powered sniper’s rifles with night-vision scopes, semi-automatic carbines loaded with armor-piercing shells, a couple of MAC-10 machine pistols, M-16 automatic rifles, and semi-automatic riot shotguns. “Typical Barnum overkill,” Wacey had scoffed loud enough to be heard by the crowd in the camp. A few people laughed. “Supporters,” Wacey whispered to Joe.

Barnum had ordered the three horsemen to “take as much as they could,” and McLanahan had loaded down the canvas panniers while Joe and Wacey stared at each other in puzzlement. Barnum made it clear that he was assuming command of the operation and that the two Game and Fish officers were subordinate to the county sheriff, which was officially true in this circumstance. He “strongly advised” that both equip themselves with more firepower. Both had sidearms—Joe had his never-fired-in-anger-and-once-swiped-by-Ote-Keeley Smith & Wesson .357 Magnum revolver, and Wacey had his 9mm Beretta semi-automatic. Finally, Wacey was persuaded to strap to his saddle one of the carbines in a scabbard. Both had pitched in to help McLanahan, who was a boyish-looking former college ROTC officer, to load the panniers on the two packhorses so they could finally leave.

Barnum scoffed when he saw that, instead of digging into the county arsenal, Joe was taking his personal remington Wingmaster .12-gauge shotgun, which was primarily a bird-hunting weapon. If he had to take a shotgun, Barnum said, at least it should be one of the short-barreled riot guns from the truck. Joe explained that he had had the shotgun since his teens and he was comfortable with it. Joe was known as an excellent wing shot when it came to game birds or, occasionally, clay targets. Strangely, he could rarely hit a target if it was stationary, only if it was moving or flushing from the underbrush. He had the ability to hit a fast-moving target by instinct and reaction, and he never really aimed. If he aimed, he missed. Joe had failed his initial pistol test and had barely passed on his second (and last) attempt. While he was fully capable of bagging his limit of three pheasants with three well-placed aerial shots, he was unable to punch holes in the outline of an intruder on the firing range. Barnum finally persuaded Joe to at least load his shotgun with magnum double-ought buckshot shells so if he had to he could “knock down a house.” But Joe thought how odd it was to be loading the shotgun he had used since boyhood for ducks and pine grouse with shells designed solely to kill a man. But he did it, and he filled one pocket of a saddle bag with a dozen extra rounds.

Barnum briefly took Joe and Wacey aside while they waited for Deputy McLanahan to secure his panniers.

“Guess who is on the way to observe this rodeo, boys?” Barnum asked them. Joe and Wacey exchanged glances but neither knew.

“Vern Dunnegan!” Barnum clapped Joe and Wacey on their shoulders. “Your mentor. He called and left a message with the dispatch.”

“Why is Vern here?” Joe asked. Wacey shrugged.

“He was in the area and heard about it on the radio, I suppose,” Barnum said. “So don’t screw up, boys. Not only will the entire valley be watching, but Vern will be watching, too.” There was sarcasm in Barnum’s voice.

Most of the gear, including the chuck box, they left with Barnum and the bustle of people and equipment. As they finally mounted and had turned their horses to the trail-head, they could hear Sheriff Barnum, flanked by the two retired Korean War vets from the VFW post, on his radio trying to track down his missing helicopter.

“HOW CLOSE ARE we?” Joe asked Wacey as he nosed his horse through the silent pocket of aspen. In timber this thick, it was best to let Lizzie pick her own way through. He just pointed her in the general direction, which was behind and to the left of Wacey. Wacey was a few yards ahead, and he reined in his mount and leaned to the side of his saddle.

“Couple hours,” Wacey said, also in a murmur.

“That’s what I was worried about.”

Hedeman nodded. They would not make it to the outfitters’ elk camp in daylight, even though getting there before dark had been the purpose of the trip.

Joe walked his horse abreast Wacey’s palomino. Two aspens as thin and round as baseball bats stood between them. The grove was heavily timbered, and black roots curled up through a carpet of lemon-colored leaves.

“And here comes the reason why,” Wacey grumbled.

It was hushed in the middle of the trees, the light was dappled and muted, but they could hear the clinking of Deputy McLanahan and his packhorse skirting the grove on the outside. McLanahan had fitted the packhorse with hunting panniers, and the bulging canvas bags were so wide that he couldn’t follow Joe and Wacey into the grove. Joe and Hedeman caught a glimpse of the deputy down a narrow chute in the trees; it was clear that McLanahan was much less of a horseman than Joe on his worst day.

“When I’m elected I’m going to fire his butt before I even order business cards,” Hedeman whispered, looking down the chute where McLanahan had passed. Joe didn’t respond. There was no need to.

THEY WAITED FOR Deputy McLanahan in the clear of a saddle slope that was bordered on each side by juniper pine. Commas of snow from that morning lay in long pools of shadow cast by boulders and trees. Groves of aspen were bright yellow with fingers of crimson coursing through them. The evening sun made the colors intense, almost throbbing.

Joe thought of the contrast of the last few hours. At Crazy Woman Creek, he had seemed crowded by admirers and he felt like a member of a powerful force. Here, in the cool darkening stillness of the Bighorns, he felt tiny and insignificant.

“I’m gonna be real sore tomorrow,” bellowed McLanahan as he approached.

Joe noticed Wacey shift his weight sharply in his saddle, a familiar sign of irritation.

“When you’re sneaking up on somebody, you might consider keeping your voice low,” Wacey hissed as McLanahan approached. “It’s an old, sly Indian trick. We’re assuming that the people we are sneaking up on have ears mounted on each side of their head.”

Deputy McLanahan, clearly angry, started to say something but caught himself. Wacey was not fun to argue with.

“You’re slow and we’re late,” Wacey continued in the low hiss. “We aren’t going to get there with any light. We’re going to have to cold camp up here and go into the outfitters’ camp at dawn to see if we can catch anyone.”

McLanahan’s jaw was tight, and his eyes glistened. Joe felt sorry for the deputy. Much of the delay had been the deputy’s fault but Hedeman was pressing the point.

“Starting late ain’t my fault. Barnum read me a list of supplies to bring that was as long as your arm,” McLanahan finally said, and his voice caught.

“The hell it ain’t,” Wacey answered, turning away and nudging his horse forward.

“Don’t worry about it,” Joe assured McLanahan. “Let it go.”

“He don’t need to say that,” McLanahan answered, his bottom lip trembling. “Not that way.”

Don’t cry, for God’s sake, thought Joe. He clicked his tongue, and the buckskin walked. He left McLanahan alone to compose himself, and he wondered what was with Wacey. Wacey seemed uncommonly irritable. He hoped it didn’t have to do with the fact that the success or failure of this venture would likely become an issue in the future sheriff’s race against Barnum.

THEY PICKETED THEIR horses by the blue light of fluorescent battery lamps and spread out sleeping bags tight against a granite bluff. They were close enough to the elk camp, Wacey said, that a fire was out of the question.

Marybeth had made a half-dozen ham sandwiches, and they ate them in the dark. McLanahan passed around a pint of Jim Beam bourbon, which seemed to improve Hedeman’s mood, at least a little.

“I missed my son’s football practice tonight,” McLanahan said unexpectantly. “I’m the defensive line coach.”

“You have a son?” Joe asked. McLanahan was just too young for that, he thought.

“Well, he’s not actually my son.” McLanahan sounded a bit sheepish. “He’s the son of my fiancée. We’re livin’ together. She’s been married a couple of times before. She’s quite a bit older.”

“Oh.”

Wacey snorted. “What in the hell does that have to do with the price of milk?”

“First practice I missed,” McLanahan said. “Twelve Sleep plays Buffalo on Friday. Home opener.”

“The mighty Buffalo Bison, our nemesis,” Hedeman said sarcastically. Then: “Why don’t you go find your radio and tell Barnum where we’re at and what we’re doin’. All those folks down there will want a report so they can spend the rest of the evening second-guessing us. Let him know we’ll move on the elk camp before dawn tomorrow.”

McLanahan nodded and wandered away to dig through his panniers.

“Jesus,” Wacey complained after McLanahan was gone. “Havin’ him on the payroll is like havin’ two good men gone.”

“Take it easy on him,” Joe said.

Wacey grunted and chewed his sandwich. “I’ll be interested to find out what was in that cooler Ote had with him.”

“Yup.”

“I suppose it coulda been anything,” Wacey continued. “Of course it might not mean a goddamn thing in the end, I guess.”

Joe nodded. Then he reeled off the number of ranch houses between Crazy Woman Creek and the Pickett home that Ote Keeley could have gone to for help.

“There was a reason he came to our house,” Joe said. “I just don’t know what it could be.”

“You’re gonna send that cooler and those shit pellets to Cheyenne to get it checked out?”

“Yeah.”

“Then we’ll know,” Wacey said.

“Then we’ll know,” Joe echoed.

“Could be nothin’,” Wacey said. “Could be one of those things we just never know, and the only guy who knows is stupid, dead Ote.”

“Maybe Ote was bringing you a couple of beers,” Deputy McLanahan said from the dark as he approached. “Maybe that’s what was in that cooler. Maybe he thought you guys would pop a couple and forgive each other.”

“Excuse me, McLanahan,” Wacey said. “Did you get Barnum?”

McLanahan told Joe and Wacey that he had talked with Sheriff Barnum and told him of their status. He said Barnum had located the helicopter and the earliest it could get back up to Saddlestring was tomorrow afternoon. There had been no sightings as yet of the other two outfitters, Kyle Lensegrav or Calvin Mendes.

“Guess who else was down there at command central?” McLanahan asked, the light reflecting off his teeth.

Neither spoke.

“Vern Dunnegan!” McLanahan’s voice was a mix of excitement and awe.

Joe noted that Wacey had looked sharply at him to check his reaction. Joe didn’t flinch.

“Vern says, ‘Be careful, boys. Make me proud.’ ”

“What’s Barnum say?” Joe asked.

“Barnum says, ‘Don’t fuck up and make me look bad.’ ” McLanahan laughed.

Vern, like Barnum, was a kind of legend—the most popular and influential game warden ever in the area, as well as a force in the community. The kind of guy who had coffee with the city councilmen at 10 each morning in the Alpine Cafe and who was not only tougher than hell on poachers and game violators but was also known to fix a few tickets and let a few locals off the hook. Even though he was primarily a state employee, Vern always liked to think of himself as an entrepreneur. He boasted that he had 31 years of business experience. Vern was always involved with something in town, whether it was the local shopper newspaper, a video store, satellite dishes, or a local radio station. Vern always owned a share and had a partner or two. For whatever reasons, the partners always left town and Vern ended up with the enterprise. Then he sold it and moved on to the next venture. Some said he was a good businessman. Most said he was nakedly greedy, and he systematically looted each company until the partners left out of disgust and fear. Vern Dunnegan had cast a big shadow. So big, Marybeth had said, that Joe had yet to see much sunlight in the Twelve Sleep Valley as far as the community went. Vern had supervised both Wacey and Joe, and he had tutored them both in the ways of the field. No one knew more about the ways and means of poachers and game law violators—or about the vile side of humans out-of-doors—than Vern Dunnegan.

It was Vern’s shadow that had probably prevented Joe from being notified that morning about the incident in the campground at Crazy Woman Creek. Vern had resigned six months earlier to go to work for a large energy company as a field executive in “local relations,” whatever that was. The rumor at the time was that Vern had more than tripled his salary.

THEY DISCUSSED THE plan and the possibilities. They would move in on the elk camp in the predawn from three directions and close in. Wacey said he would communicate with Joe and Deputy McLanahan with hand signals. If anyone was in the camp, they would surround and disarm them as quickly as possible.

“We don’t know if these two had anything to do with Ote getting shot,” Wacey said. “Ote may have wandered out of camp on his own, run into some kind of trouble, and made the midnight run to Pickett’s house. These two might not even know where he is or what’s going on.”

“On the other hand ...” interrupted McLanahan, barely able to contain his excitement of the possibility of being part of some real action.

“On the other hand, they may have gotten drunk with old Ote and got in a fight and shot him a couple of times,” Hedeman finished. “So we’ve got to be prepared for just about anything.”

“If they’re involved they might not even be there,” Joe said. “They might have cleared out last night and they’re in Montana by now.”

JOE LAY IN his sleeping bag but couldn’t sleep. He doubted the other two could either. The stars were out, and it was colder than he had expected it to be. He could see his breath in the starlight.

His revolver was within reach on the side of his sleeping bag, and he reached down in the dark and felt the checkered grip.

Joe thought of his girls. It was only 9:30, although it seemed much later. Both girls would be in bed, but probably not asleep. More than likely, they would be pretty wound up in that motel room. Sheridan would be reading or gabbing to her bear. She used to do that at night with her kitten, and before that, her puppy. Marybeth would be reading Lucy a story or cuddling her until she drifted off. Sheridan would no doubt be checking the motel window for the approach of more monsters.

He wondered how this incident would affect his girls, especially Sheridan. It was one thing to look for monsters and another thing to actually see them. Ote’s sudden appearance had somehow thrown a new curve on things, and Joe knew Marybeth would be thinking about that. The sanctity of their little family had been violated. Ote’s blood would remain on the walk for months—and in their memories forever. Joe wondered what kind of cleaning substance he could buy that would remove bloodstains from concrete. How would Lucy remember this day? Would it make her more cautious, more suspicious? Would Sheridan wonder if her parents—especially her dad—could actually protect her from harm after all? The relationship between a father and his daughters, Joe had discovered, was a remarkably powerful thing. They looked to him to accomplish greatness; they expected it as a matter of course because he was their dad and therefore a great man. Someday, he knew, he would do something less than great and they would see it. It was inevitable. He wondered at what age his luster would dim in Sheridan’s eyes and then in Lucy’s. He wondered how painful it would be for them all when they recognized it.

Joe Pickett had two passions. One was his family and the other was his job. He had tried as best he could to keep them separate, but that morning Ote Keeley had forced them together. Joe now looked at both differently and what he saw pained him. Marybeth had never actually complained about the way her life had gone since marrying Joe Pickett. Her frustration appeared in random sighs and sometimes hopeless facial expressions that she probably didn’t even recognize as such—but Joe did. Marybeth had been on a career path—she was a bright and attractive woman. But by marrying Joe in college, having children, and moving around the state with him from one beat-up house to another, her life had turned out differently than she, or her hard-driving mother, imagined. Marybeth deserved a certain standard, or at least a permanent home of their own; Joe had not been able to provide either. It was eating at him, taking a million tiny bites. When she talked on the telephone to her old college friends who were traveling and managing businesses and enrolling their children in private schools, she would be blue for weeks afterward, although she wouldn’t admit it. While he loved his job—he was, after all, nature boy—the guilt he felt this morning when he learned that they couldn’t even afford a motel room in town still shrouded him. The exhilaration of the mountains right now brought a hard-edged sense of regret and confusion. His belief that what he did was good—and that he was good at it—would not put his daughters through college or allow his wife to ever take a real vacation.

Joe shifted to try to get more comfortable. He tried to think of other things but he couldn’t. Joe tried to imagine what Marybeth would think if she could see him now, on a manhunt with his hand on his revolver and two (heavily armed) men sleeping next to him. It was a boyhood dream coming true; good guys pursuing bad guys. He couldn’t deny the excitement that was keeping him wide awake. It would be hard to describe to Marybeth how he felt right now. He wasn’t sure she would understand.

He wondered what Marybeth, the protector of his career who had never understood what Joe saw in Vern (or Wacey, for that matter), would think of Vern being back in Saddlestring. Joe tried to stave off the resentment he felt toward Vern. Vern had been good to him and had recommended him for the Saddlestring district. It wasn’t Vern’s fault that everybody seemed to think Vern hung the moon when it came to setting the standard for a local warden.

Too much to think about, and no conclusions to be reached.

He raised up on an elbow and in the faint light of the stars, could see Deputy McLanahan walking away from the camp to relieve himself. McLanahan couldn’t sleep either.

As he stared up at the hard white stars—there were so many of them that the night sky looked gauzy—Joe realized that if things were to change for him and his family, he probably would have to change. Marybeth and his girls deserved better than what they had; to give them more, he would have to give up the other thing he deeply loved.

But first there was the matter of a dead man in his backyard and an elk camp a few miles away.

Wacey sighed deeply. He was snoring. He seemed to be exhausted. Joe wished he could sleep like that.

7

AT SIX A.M., they had rolled up their sleeping bags in silence, saddled up, and followed Wacey up and over the summit into the creek bottom where the elk camp was. No one had brought breakfast.

Joe was alert but not completely awake. Although he knew he must have slept, he could not recall actually waking. He had slipped in and out of a kind of cruel half-consciousness that was vivid with dreams and episodes that didn’t connect.

Joe followed Wacey down a horse trail toward the camp. It was still dark enough that Wacey’s worn denim jacket was out of focus. Deputy McLanahan followed Joe. No words had yet been exchanged that morning.

They tied up their horses in a stand of lodgepole pines. Wacey poured dusty piles of oats into the grass for the horses to eat and to distract them and keep them quiet while the three men walked the rest of the way up the trail to the camp. It was an hour before dawn and the mountain air was crisp. The cold that had settled in for the night was just beginning to retreat through the trees and up the slopes.

They were upon the camp in less than 30 minutes. Canvas outfitters’ tents came suddenly into view, blue-gray smudges against the dark grass and trees, and when they did, Wacey dropped into a hunter’s squat and Joe and McLanahan followed suit. They kept hidden from the tents by a hedgerow of three-foot young pines.

Wacey leaned into Joe and McLanahan and whispered that McLanahan should flank left and Joe right. Wacey would continue down the horse trail and hide behind a granite spur just inside the periphery of the camp. When they all found good cover where they could see into the camp, they would wait until it was light. Wacey said he would ask the outfitters to come out with their hands behind their heads. If only he spoke, he said, the outfitters wouldn’t know how many men were out there. Joe was impressed by Wacey’s take-charge attitude and command of tactics. Wacey seemed to be a natural and comfortable leader, and he had led them straight to the elk camp without a map. He had taken command and was not shy about it. Joe had not seen this side of Wacey before.

“Did you see the horses?” Wacey asked, in a low whisper. “There’s two of ’em in a corral.” Joe shook his head no. He had dropped too quickly to see anything more than the tents.

“There’s probably somebody in camp after all,” Wacey said, looking to both Joe and McLanahan. “Those horses are likely to notice us before the outfitters do, so keep quiet and close to the ground and out of sight.”

McLanahan let out a long breath that rattled at the end of it and mindlessly caressed the stock of his shotgun with his thumb. He was anxious and probably scared. McLanahan’s face no longer had the kind of whiz-bang enthusiasm for action in it that Joe had seen the night before. Joe understood.

JOE KEPT LOW and picked his way through the trees to the right side of the camp. He kept his shotgun parallel to the ground, glad he had it with him. He slid along the trunk of a thick, downed pine tree until he reached the root pan. It was there, for the first time, that he really raised up and looked at the camp.

There were three tents constructed in a semicircle, with the opening of each aimed at a fire ring. They were permanent tents with stoves inside and probably wooden floors. Black stovepipes poked from the top of each tent. A thick wooden picnic table with benches was near the fire ring, as well as stumps for the elk hunters to sit on while they drank and watched the fire at night.

The ground around the tents was hard packed by years of boots and horses’ hooves during hunting season. A blackened coffee pot hung from an iron T near the cold camp fire. It was impossible to tell when the campsite had been used last.

Behind the tents, directly opposite the horse trail they had entered the camp on, was the area used for hanging elk and deer. The crossbeams for suspending the carcasses as they were skinned and cooled were wired high in the trees, as well as rusty block-and-tackle for winching up 500-pound animals. Joe could now see the makeshift lodge-pole corral through the trees.

The camp was still. Only the gentle tinkling of a foot-wide creek—the headwaters of the north fork of the Crazy Woman—made a sound. They had somehow surrounded the camp without raising warning chatters by squirrels, and the horses apparently hadn’t seen them either because there was no nickering. Joe looked at his watch and waited. The fused warm light of dawn was now creeping down the summit. It was a clear morning, and the camp would soon be bathed in sunlight.

He shifted to get more comfortable and tried to imagine who might be inside the tents and what they might be doing. As he did so, he noticed a quick movement.