CrimethInc.

Days of War, Nights of Love

Crimethink for Beginners

Warning: this book will not save your life

Think about your direct bodily experience of life. No one can lie to you about that.

PREFACE / What is a “CrimethInc.”?

{right this moment} I. A SHORT “HISTORY” OF THE C.W.C.

II. Important Documents: a CrimethInc. Contra-diction-ary

No Gods No Masters; An Introduction to the idea of thinking for yourself

Where does the idea of “Moral Law” come from?

God is dead—and with him, Moral Law.

But if there’s no good or evil, if nothing has any intrinsic moral value, how do we know what to do?

But how can we justify acting on our ethics, if we can’t base them on universal moral truths?

Hierarchy ... & Anarchy; Resurrecting anarchism as a personal approach to life.

Do we really need masters to command and control us?

{throughout the medieval era} THE BRETHREN OF THE FREE SPIRIT

{early 1600’s} THE PAUPER KINGS OF THE SEA

The Martial Law of Public Opinion

Marriage ... and Other Substitutes for Love and Community

{1814} PERCY SHELLEY AND MARY GODWIN ELOPE

C is for Capitalism and Culture

How does this affect the average guy?

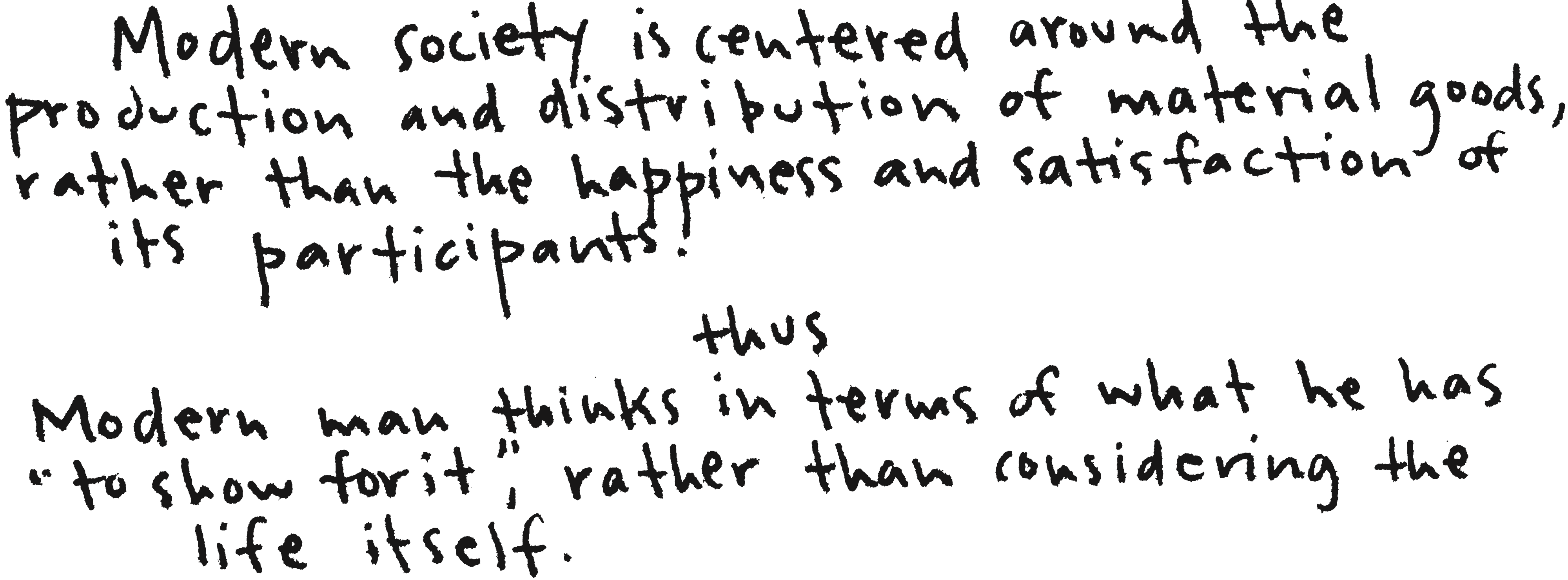

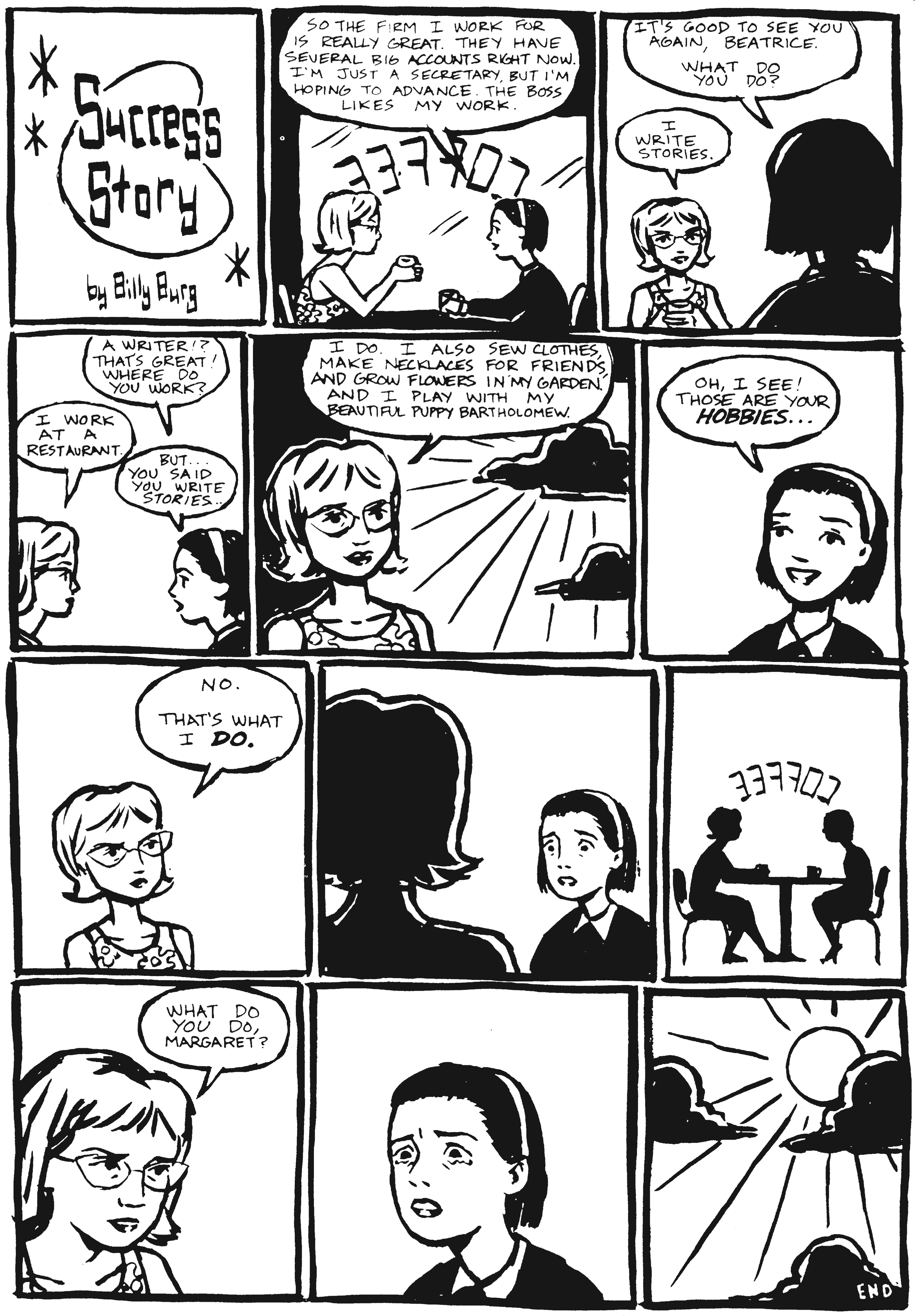

What does capitalism make people value?

“But doesn’t competition lead to productivity?”

“Don’t tell me life would be better and more free in a system like the Soviet Union had”

So ... who exactly is it that gets power under capitalism?

What kind of place does this make our world?

OK, OK, but what’s the alternative?

POSTSCRIPT: A Class War Everyone Can Fight In

Enough abstractions! let’s talk about real life!

{Spring, 1871} THE^PARIS COMMUNE

From Over-the-Counter-Culture to Beneath the Underground.

D is for Death and Domestication

{Fall, 1891} RIMBAUD’S DEATHBED CONVERSION

THE DOMESTICATION OF ANIMALS ... AND OF MAN.

{December, 1900} THE QUEEN OF DRAG KINGS ENTERS A SUFI PARADISE

Freedom is a sensation. We have only “choice.”

Nothing is true, everything is permitted.

{during the first world war} ART EXPLODES ITSELF

H is for History, Hygiene, and Hypocrisy

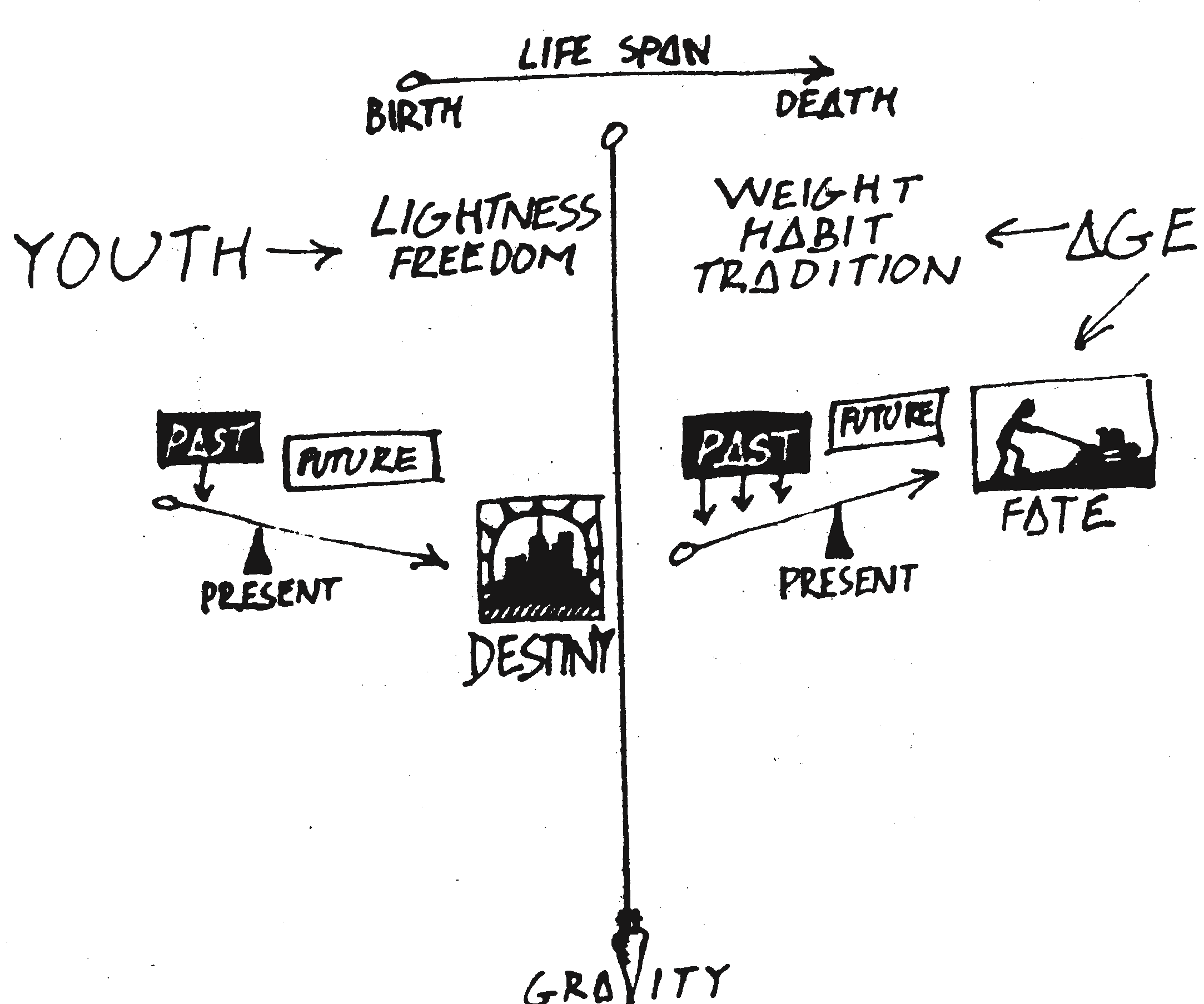

How to Break the Chain of Events (time travel and other banalities)

Postscript: It Not Now, Then When?

{Summer of 1918} SHORT-LIVED ANARCHIST STATE IN FIUME

{November 7,1922} THE CONCERT AT BAKU

{the 1930’s} ANARCHIST REVOLUTION IN SPAIN

Exhibit A: Crimethlnc. Itself

“insINC.ere”

{April 9, 1950} THE NOTRE-DAME INCIDENT

I is for Identity, Ideology, and Image

1. Identity and the Scarcity Economics of Self

Seduced by the Image of Reality

{August 24, 1967} The Conquest of the New York Stock Exchange

M is for their Media, Movement, and Myth

The Revolution Cannot Be Televised.

The Values of Mass Production.

{May 1968} THE PARIS COMMUNE RETURNS FROM THE DEAD

II. Nadia’s Answer: Absolutely Not.

{July 8,1972} THE GERMAN COURTROOM GETAWAY

{late 20th century} CRIMETHINC. IS BORN

P is for Plagiarism, Politics, and Production

II. Plagiarism and the Modern Revolutionary

III. Language and the Question of Authorship Itself

{spring 1992} THE 1st INTERNATIONAL CRIMETHINC. CONVENTION

FACE IT, YOUR POLITICS ARE BORING AS FUCK

Product is the Excrement of Action.

{spring 1994} THE SECOND INTERNATIONAL

{summer 1994} THE FIRST CRIMETHINC. COMPOUND OPENS

AlieNation: The Map of Despair

If your heart is free, the ground you’re standing on is liberated territory. Defend it.

{spring 1995} THE HIJACKING OF THE WASHINGTON POST

Nostalgia for an unpredictable future

Folk Science Vs. “The” Scientific Method

{fall 1997} CRIMETHINC. FINISHES THE JOB FOR DADA

{spring 1998} CRIMETHINC. BALLET TROUPES DEBUT

Why I Love Shoplifting from big corporations

{November 1999} THE STOCKHOLM ACTION

{November/December 1999 and April 2000} OUT OF THE WAITING GAME AND INTO THE FIRE

{at this very moment} PRESENT CRIMETHINC. PROJECTS

eclipse the past

Warning: this book will not save your life

Today there is a booming discontent industry, consisting of entrepreneurs who cash in on your misery by selling you products that describe and decry it. Thus the exchange economy finds a place even for its enemies: perpetuating both industry and discontent as we struggle to fight them, we keep the wheels turning by selling more merchandise. And as in every other aspect of your lives, your real desires to make something happen are channeled into consuming— and your own abilities and potential are displaced, projected onto the “revolutionary” items you purchase.

This book could be a part of that process. While we hope we are using our product to “sell” revolution, it might be that we are just using “revolution” to sell our product.{1} The best of intentions can’t protect us from this risk. But we’ve undertaken this project because we felt that, in addition to our other, less explicitly compromised activities, it might be worth giving the old experiment one more try: to see if a commodity can be created that gives more than it takes away.

For this book to have even the smallest chance of succeeding in that tall order, you can’t approach it passively, you can’t expect it to do the work. You have to regard it as a tool, nothing more. This book will not save your life; that, my friend, is up to you.

OK, that said, HERE WE GO!!!

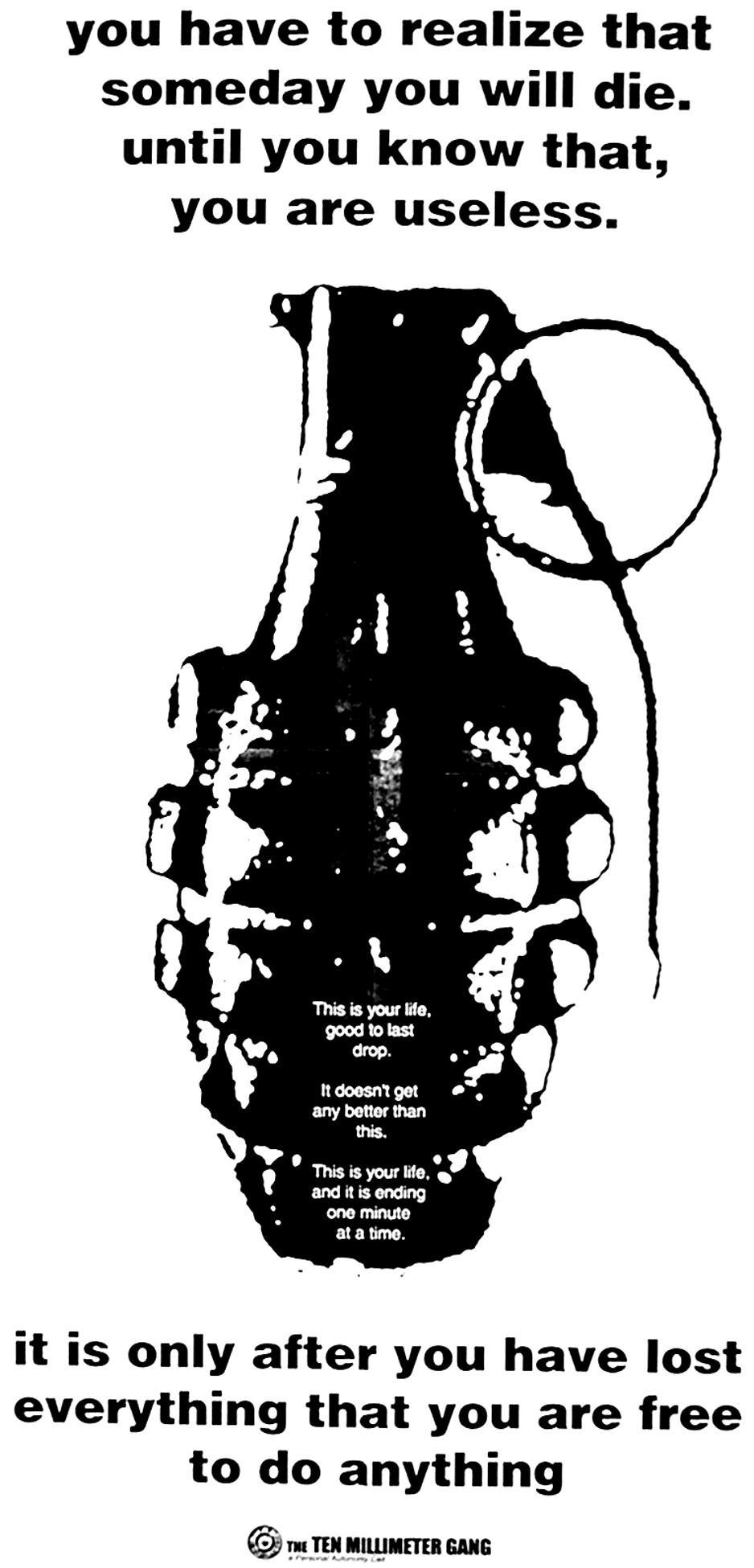

Think about your direct bodily experience of life. No one can lie to you about that.

How many hours a day do you spend in front of a television screen? A computer screen? Behind an automobile windscreen? All three screens combined?

What are you being screened from?

How much of your life comes at you through a screen, vicariously?

(Is watching things as exciting as doing things? Do you have enough time to do all the things that you want to? Do you have enough energy to?)

And how many hours a day do you sleep? How are you affected by standardized time, designed solely to synchronize your movements with those of millions of other people? How long do you ever go without knowing what time it is? Who or what controls your minutes and hours?

The minutes and hours that add up to your life?

Can you put a value on a beautiful day, when the birds are singing and people are walking around together? How many dollars an hour does it take to pay you to stay inside and sell things or file papers? What will you get later that could make up for this day of your life?

How are you affected by being in crowds, by being surrounded by anonymous masses? Do you find yourself blocking your emotional responses to other human beings?

And who prepares your meals? Do you ever eat by yourself? Do you ever eat standing up? How much do you know about what you eat and where it comes from? How much do you trust it?

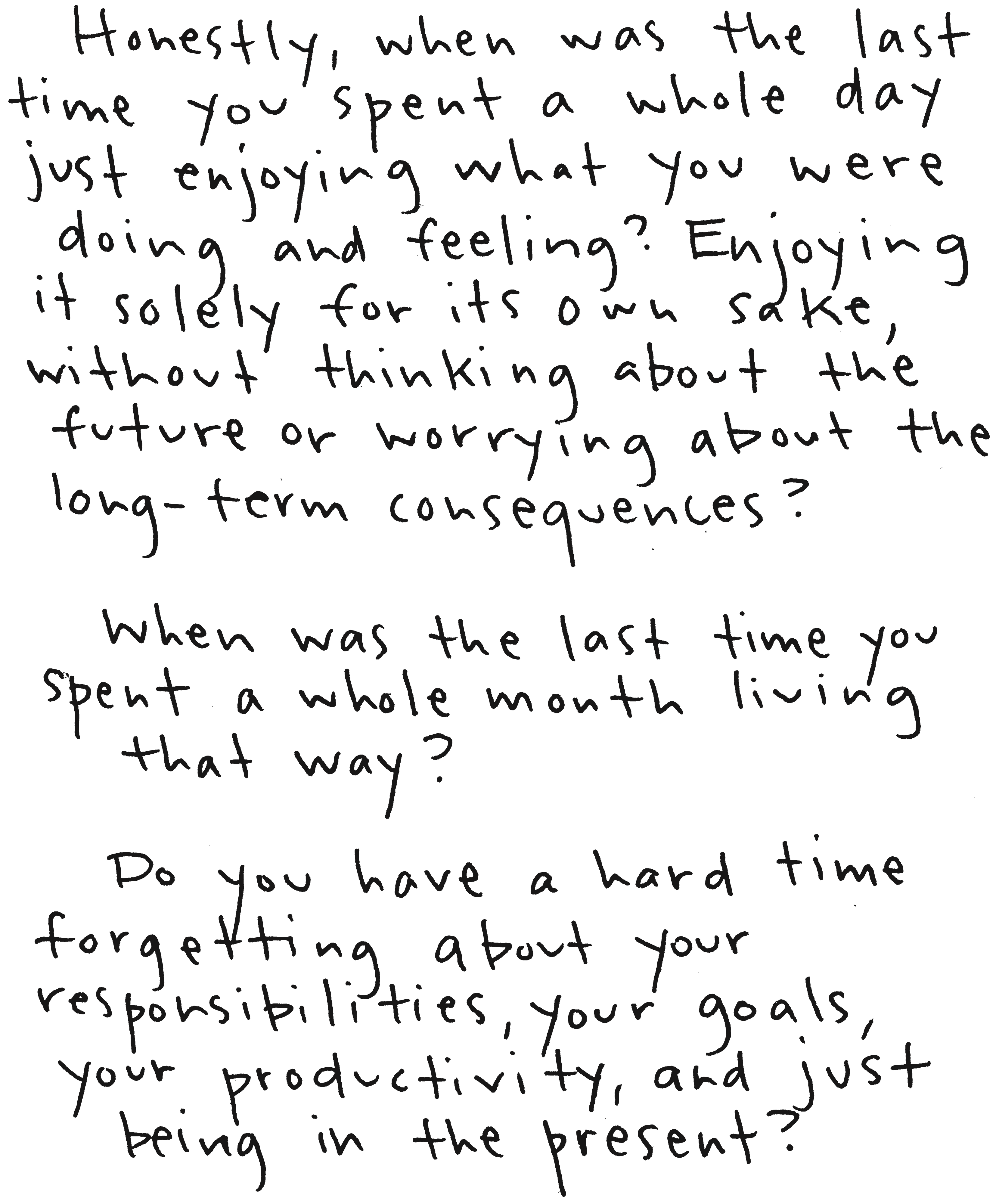

What are we deprived of by labor-saving devices? By thought-saving devices? How are you affected by the requirements of efficiency, which place value on the product rather than the process, on the future rather than the present, the present moment that is getting shorter and shorter as we speed faster and faster into the future? What are we speeding towards?

Are we saving time? Saving it up for what?

How are you affected by being moved around in prescribed paths, in elevators, buses, subways, escalators, on highways and sidewalks? By moving, working, and living in two- and three-dimensional grids? How are you affected by being organized, immobilized, and scheduled... instead of wandering, roaming freely and spontaneously? Scavenging? (Shoplifting?)

How much freedom of movement do you have—freedom to move through space, to move as far as you want, in new and unexplored directions?

And how are you affected by waiting? Waiting in line, waiting in traffic, waiting to eat, waiting for the bus, waiting for the bathroom — learning to punish and ignore your spontaneous urges?

How are you affected by holding back your desires?

By sexual repression, by the delay or denial of pleasure, starting in childhood, along with the suppression of everything in you that is spontaneous, everything that evidences your wild nature, your membership in the animal kingdom?

Is pleasure dangerous? Could danger be joyous?

Do you ever need to see the sky? (Can you see stars in it any more?) Do you ever need to see water, leaves, foliage, animals? Glinting, glimmering, moving?

Is that why you have a pet, an aquarium, houseplants?

Or are television and video your glinting, glimmering, moving?

How much of your life comes at you through a screen, vicariously?

Do videotapes of yourself and your friends fascinate you, as if you are somehow more real in image than in life?

If your life was made into a movie, would it be worth watching?

And how do you feel in situations of enforced passivity? How are you affected by a non-stop assault of symbolic communication — audio, visual, print, billboard, computer, video, radio, robotic voices—as you wander through the forest of signs? What are they urging upon you?

Do you ever need solitude, quiet, contemplation? Do you remember it? Thinking on your own, rather than reacting to stimuli? Is it hard to look away?

Is looking away the very thing that is not permitted?

Where can you go to find silence and solitude? Not white noise, but pure silence? Not loneliness, but gentle solitude?

How often have you stopped to ask yourself questions like these?

Do you find yourself committing acts of symbolic violence?

Do you ever feel lonely in a way that words cannot even express?

Do you ever feel ready to LOSE CONTROL?

[Anti-Copyright]

This PDF is available free of charge thanks to the generous contributions several hundred anarchists and fellow travelers made to a fundraiser in December 2021.

Additional copies of this book are available from www.crimethinc.com

Plagiarized © 2001, 2011 by CrimethInc. Free Press

Printed on 100% post-consumer recycled paper by unionized printers in Canada.

English language (and all applications thereof) used without permission from its inventors, writers, or copywriters. No rights reserved. All parts of this book may be reproduced and transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, especially including photocopying if it is done at the expense of some unsuspecting corporation. Other recommended methods include broadcasting readings over pirate radio, reprinting tracts in unwary newspapers, and just signing your own name to this and publishing it as your own work. Any claim relating to copyright infringement, advocation of illegal activities, defamation of character, incitement to riot, treason, etc. should be addressed directly to your Congressperson as a military rather than civil issue.

Oh, yeah ... intended “for entertainment purposes only,” you fucking sheep.

Warning: The word “revolution,” which is used constantly throughout these pages with an unironic naivete, may be amusing or off-putting to the modern reader, convinced as he is that effective resistance to the status quo is impossible and therefore not even worth considering. Gentle reader, we ask that you suspend your disbelief long enough to at least contemplate whether or not such a thing might be worthwhile if it were possible; and then that you suspend it further, long enough to recognize this disbelief for what it is—despair!

Untitled

What is crimethink?

Today, everything that can’t be bought, sold, or faked is crimethink.

PREFACE / What is a “CrimethInc.”?

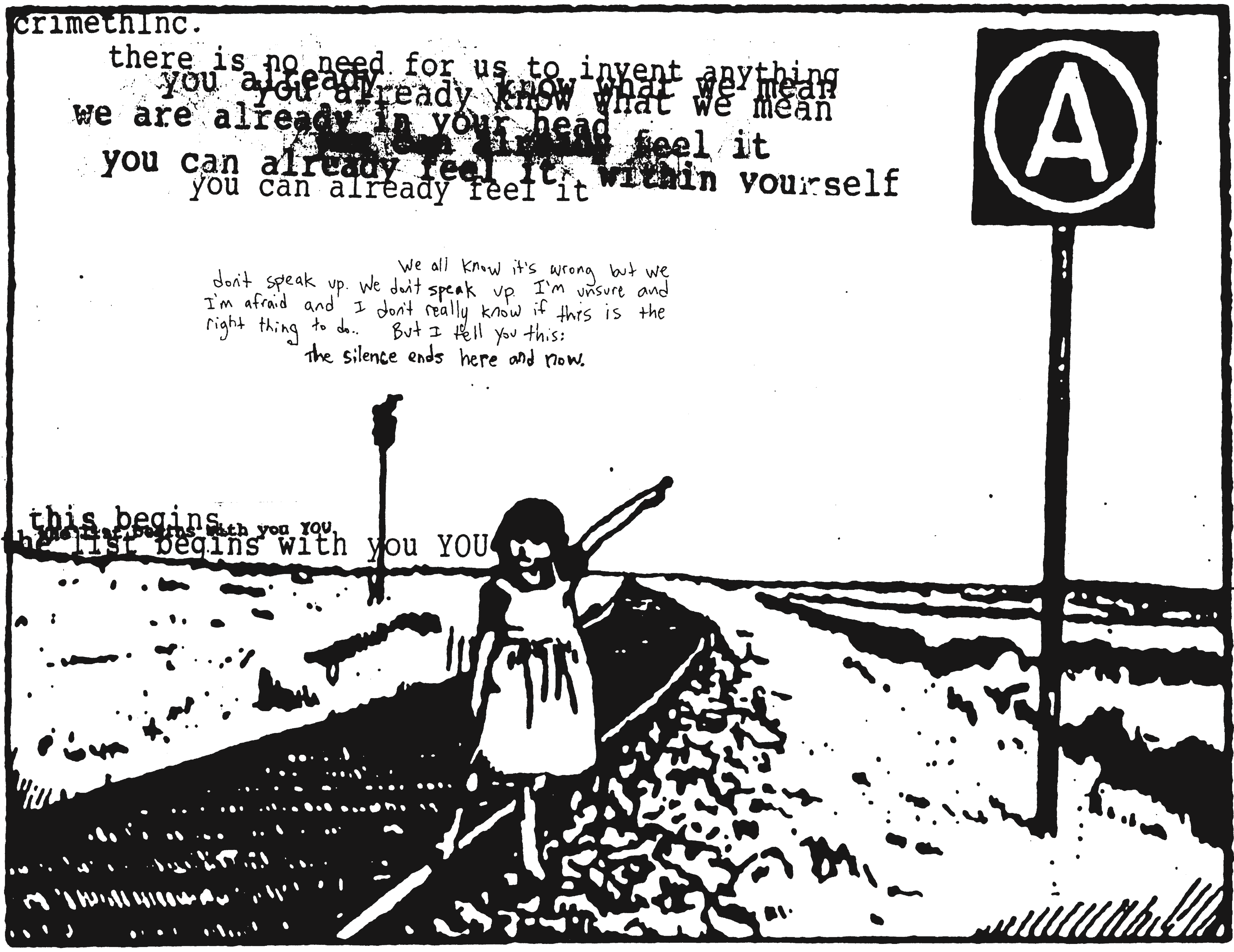

A spectre is haunting the world today: the spectre of crimethink, and the underground front which heralds it. In every corporate washroom, on every street corner, under every roof from the ghettoes to the suburbs you can hear the whispers: “What is this CrimethInc.? Who are they? What do they want?”

These questions can be approached, if not answered. CrimethInc. is significant for what it is not: it is not a membership organization. It is not an elitist vanguard that purports to lead the masses out of darkness to salvation—experience has shown a thousand times that such parties are the social forces that create masses. And it is not a Movement, either: for such things only exist as a part of history, and as such are subject to its laws—gestation, ascendance, decline. As crimethink is a force that exists beneath the currents of history, outside the chain of events, CrimethInc. is the first stirrings of a revolt that will take us all out of history.

CrimethInc. is invincible because it is centerless, amoebic, invisible. Who is CrimethInc.? It could be anyone—the woman on the bus next to you could be one of us. Perhaps an autonomous CrimethInc. nucleus is at play in your town as you read this; perhaps you will form one when you’re finished reading. Because CrimethInc. is an expression of longings that are in every heart, it could be just three travelers in an Italian hostel tonight and two hundred thousand independent cells in full blown insurrection next month.

As for what we want—you’d have to ask each of us, one by one, and hopefully you know better than to trust people when they answer that question.

It was said of one of our predecessors, a body of ex-artists and theorists active primarily in the 1960’s, that their group was unique in that it represented a stance rather than an ideology (“not a position, but a proposition”). It would be tempting to say that CrimethInc. improves on their method in that it is founded on a shared desire, rather than a common critique; but this also misses the mark. CrimethInc. is a web of desires, all unique to the individuals who feel them; what sets CrimethInc. apart is that it is a means of interlocking these desires, of creating mutually beneficial relationships between people with different needs. This is why we have the bureaucrats and entrepreneurs, whose very existence depends on our isolation and frustration, shaking in their loafers. This is how we have come to be the ones to fire the first shots of the third and final world war, the war which will be fought for total liberation.

Untitled

What is CrimethInc.

CrimethInc. is the black market where brilliant schemes and wild abandon are traded for lives.

CrimeThink for Yourself!

How To Use This Book.

It is crucial to point out that this book isn’t designed to be used in the way a “normal” book is. Rather than reading it from one cover to the other, casting perfunctory votes of disapproval or agreement along the way (or even deciding to “buy in” to our ideas, in passive consumer fashion), and then putting it on the shelf as another inert possession, we hope you will use this as a tool in your own efforts—not just to think about the world, but also to change it. This book is composed of ideas and images we’ve remorselessly stolen and adjusted to our purposes, and we hope you’ll do exactly the same with its contents. There’s no need to even read it as one unit if it doesn’t please you; such a thing might be too repetitive for the average bear, anyway. But please by all means use the images for posters, take sentences for your own writing, reinterpret ideas and claim them as your own inventions, turn in the articles as papers for your Sociology class—if you must turn those papers in, that is!

As for the contents themselves: we’ve limited ourselves for the most part here to criticism of the established order, because we trust you to do the rest. Heaven is a different place for everyone; hell, at least this particular one, we inhabit in common. This book is supposed to help you analyze and disassemble this world—what you build for yourself in its place is in your hands, although we’ve offered some general ideas of where to start. In our next book we’ll provide some more detailed suggestions, and share some of our experiences exploring the alternatives to the structures and forces we assault in this one. In the meantime, remember: the destructive impulse is also a creative one ... happy smashing!

-Nadia C.

Against practicality we therefore disdain the example and admonition of tradition in order to invent at any cost something which everyone considers crazy!

Forward!

by NietzsChe Guevara

I. Normal?

People from the (rapidly splintering) “mainstream” of society in Europe and the United States today take a peculiar pleasure in considering themselves “normal” in comparison to legal offenders, political radicals, and other members of social outgroups. They treat this “normalcy” as if it is an indication of mental health and moral righteousness, regarding the “others” with a mixture of pity and disgust. But if we consult history, we can see that the conditions and patterns of human life have changed so much in the past two centuries that it is impossible to speak of any lifestyle available to human beings today as being “normal” in the natural sense, as being a lifestyle for which we adapted over many generations. Of the lifestyles from which a young woman growing up in the West today can choose, none are anything like the ones for which her ancestors were prepared by centuries of natural selection and evolution.

It is more likely that the “normalcy” that these people hold so dear is rather the feelings of normalcy that result from conformity to a standard. Being surrounded by others who behave the same way, who are conditioned to the same routines and expectations, is comforting because it reinforces the idea that one is pursuing the right course: if a great many people make the same decisions and live according to the same customs, then these decisions and customs must be the right ones.

But the mere fact that a number of people live and act in a certain way does not make it any more likely that this way of living is the one that will bring them the most happiness. Besides, the lifestyles associated with the American and European “mainstream” (if such a thing truly exists) were not exactly consciously chosen as the best possible ones by those who pursue them; rather, they came to be suddenly, as the results of technological and cultural upheavals. Once the peoples of Europe, the United States, and the world realize that there is nothing necessarily “normal” about their “normal life,” they can begin to ask themselves the first and most important question of the new century:

Are there ways of thinking, acting, and living that might be more satisfying and exciting than the ways we think, act and live today?

II. Transformation

... to live as the subject, rather than the object, of history—

—or, better,

as sovereign rather than subject ...

If the accumulated knowledge of Western civilization has anything of value to offer us at this point, it is an awareness of just how much is possible when it comes to human life. Our otherwise foolish scholars of history and sociology and anthropology can at least show us this one thing: that human beings have lived in a thousand different kinds of societies, with ten thousand different tables of values, ten thousand different relationships to each other and the world around them, ten thousand different conceptions of self. A little traveling can still show you the same thing, if you get there before Coca-Cola has had too much of a head start.

That’s why I can’t help but scoff when someone refers to “human nature,” invariably in the course of excusing himself for a miserable resignation to our supposed fate. Don’t you realize we share a common ancestor with sea urchins? If differing environments can make these distant cousins of ours so very distant from us, how much more possible must small changes in ourselves and our interactions be! If there is anything lacking (and there sorely, sorely is, most will admit) in our lives, anything unnecessarily tragic or meaningless in them, any corner of happiness that we have not yet thoroughly explored, then all that is needed is for us to alter our environments accordingly. “If you want to change the world, you first must change yourself,” the saying goes; we have learned that the opposite is true.

And there is another valuable discovery our species has made, albeit the hard way: we are capable of absolutely transforming environments. The place you lie, sit, or stand reading this was probably altogether different a hundred years ago, not to mention two thousand years ago; and almost all of those changes were brought about by human beings. We have completely remade our world in the past few centuries, changing life for almost every kind of plant and animal, ourselves most of all. It only remains for us to experiment with executing (or, for that matter, not executing) these changes intentionally, in accordance with our needs and desires, rather than at the mercy of irrational, inhuman forces like competition, superstition, routine.

Once we realize this, we can claim a new destiny for ourselves, both individually and collectively. No longer will we be buffeted about by powers that seem beyond our control; instead, in this exploration of ourselves through the creation of new environments, we will learn all that we can be. This path will take us out of the world as we know it, far beyond the farthest horizons we can see from here. We will become artists of the grandest kind, painting with desire as a medium, deliberately creating and recreating ourselves—becoming, ourselves, our own greatest work.

To accomplish this, we’ll need to learn how to coexist and collaborate successfully: to see just how interconnected all our lives are, and finally learn to live with that in mind. Until this becomes possible, each of us will not only be denied the vast potential of her fellows, but her own potential as well; for we all make together the world that each of us must live in and be made by.

The other thing that is lacking is the knowledge of our own desires. Desire is a slippery thing, amoebic and difficult to pin down, let alone keep up with. If we’re going to make a destiny out of the pursuit and transformation of desire, we first must find ways to discover and release our loves and lusts. For this, not enough experience and adventure could ever suffice. So the makers of this new world must be more generous and more greedy than any who have come before: more generous with each other, and more greedy for life!

II. Utopia

Even from here, I can taste the question already on the tip of your tongue: isn’t this utopian?

Well, of course it is. You know what everyone’s greatest fear is? It is that all the dreams we have, all the crazy ideas and aspirations, all the impossible romantic longings and utopian visions can come true, that the world can grant our wishes. People spend their lives doing everything in their power to fend off that possibility: they beat themselves up with every kind of insecurity sabotage their own efforts, undermine love affairs and cry sour grapes before the world even has a chance to defeat them ... because no weight could be heavier to bear than the possibility that everything we want is possible. If that is true, then there really are things at stake in this life, things to be truly won or lost. Nothing could be more heartbreaking than to fail when such success is actually possible, so we do everything we can to avoid trying in the first place, to avoid having to try.

For if there is even the slightest possibility that our hearts’ desires could be realized, then of course the only thing that makes sense is to throw ourselves entirely into their pursuit and risk that heartbreak. Despair and nihilism seem safer, projecting our hopelessness onto the cosmos as an excuse for not even trying. So we remain, clutching our resignation, as secure as corpses in coffins (“better safe and sorry”) ... but this still cannot ward off that dreadful possibility Thus in our hopeless flight from the real tragedy of the world, we only heap upon ourselves false tragedy, unnecessary tragedy, as well.

Perhaps this world will never conform perfectly to our needs—people will always die before they are ready, perfect relationships will end in ruins, adventures will end in catastrophe and beautiful moments be forgotten. But what breaks my heart is the way we flee from those inevitable truths into the arms of more horrible things. It may be true that every man is lost in a universe that is fundamentally indifferent to him, locked forever in a terrifying solitude—but it doesn’t have to be true that some people starve while others destroy food or leave fertile farms untilled. It doesn’t have to be true that men and women waste their lives away working to serve the hollow greed of a few rich men, just to survive. It doesn’t have to be that we never dare to tell each other what we really want, to share ourselves honestly, to use our talents and capabilities to make life more bearable, let alone more beautiful. That’s unnecessary tragedy, stupid tragedy, pathetic and pointless. It’s not even utopian to demand that we put an end to farces like these.

If we could bring ourselves to believe, to really feel, the possibility that we are invincible and can accomplish whatever we want in this world, it wouldn’t seem out of our reach at all to correct such absurdities.

What I am begging you to do here is not to put faith in the impossible, but have the courage to face that terrible possibility that our lives really are in our own hands, and to act accordingly: to not settle for every misery fate and humanity have heaped upon us, but to push back, to see which ones can be shaken off. Nothing could be more tragic, and more ridiculous, than to live out a whole life in reach of heaven without ever stretching out your arms.

{right this moment} I. A SHORT “HISTORY” OF THE C.W.C.

Actually, there is nothing we despise more than history. Nothing could be more crippling than the feeling that we are part of a chain of events, an inescapable chain reaction that predetermines everything we do, everything that is possible- With everything around us supposedly a part of this vast continuum, it’s easy to forget that history itself is actually a very recent invention.

Remember, the human race has existed for over a hundred thousand years, so it is the past few thousand years of “civilization” that are the deviation from the “natural” if anything is. Before time was divided into past and future, and then subdivided and sub-subdivided further until it seems to speed past without even pausing for us to climb on, we experienced it in a radically different manner. In prehistoric days, time was not linear: it could begin afresh as the sun rose on a beautiful spring morning, pause for an eternity as your lover kissed and nibbled your thighs, end abruptly upon the death of your child. It repeated itself in circular cycles, or in climbing spirals of recurrence endlessly renewed and unique. It could not trap you or bypass you, only carry you to the moment and release you into it. Just as there were no national borders or trends of global standardization, time was not bound by any one law or system.

One could trek a few days out of one’s homeland and enter entirely new worlds, traveling through space and time in ways that simply couldn’t be measured.

You may have noticed that while the moments of great upheaval and suffering in your life are burned into your memory forever, your experiences of bliss seem to slip through the net: while you can recall the superficial details, the actual sensations seem to melt together with those of every other experience of pleasure you can recall. This is not because happiness itself is a generic, formless condition; rather, ecstasy and pleasure are simply part of a world that lies beyond the pale of history. History cannot capture or describe the things that make life magical and precious—these things can only be approached in person. They are as invisible to hindsight and narrative as they are to the instruments of the scientist.

Read this, then, not as a history of CrimethInc. and its progenitors, but as an illustration in negative space, a map to places in the occupied time of our past in which real life surfaced for a moment—to remind us that some day it will be back forever.

II. Important Documents: a CrimethInc. Contra-diction-ary

Note: When reading dry political theory, such as the texts you will find on the following pages, it may be useful to apply the Exclamation Point Test from time to time, to determine if the material you are reading is actually relevant to your life. To apply this test, simply go through the text replacing all the punctuation marks at the ends of sentences with exclamation points. If the results sound absurd when read aloud, then you know you’re wasting your time.

A is for Anarchy

The gods die twice—

—once in heaven, once on earth.

No Gods No Masters; An Introduction to the idea of thinking for yourself

No Gods

Once, flipping through a book on child psychology, I came across a chapter about adolescent rebellion. It suggested that in the first phase of a child’s youthful rebellion against her parents, she may attempt to distinguish herself from them by accusing them of not living up to their own values. For example, if they taught her that kindness and consideration are important, she will accuse them of not being compassionate enough. In this case the child has not yet defined herself or her own values; she still accepts the values and ideas that her parents passed on to her, and she is only able to assert her identity inside of that framework. It is only later, when she questions the very beliefs and morals that were presented to her as gospel, that she can become a free-standing individual.

Far too many of us so-called radicals and revolutionaries show no signs of going beyond that first stage of rebellion. We criticize the actions of those in the mainstream and the effects of their society upon people and animals, we attack the ignorance and cruelty of their system, but we rarely stop to question the nature of what we all accept as “morality.” Could it be that this “morality,” by which we think we can judge their actions, is itself something that should be criticized? When we claim that the exploitation of animals is “morally wrong,” what does that mean? Are we perhaps just accepting their values and turning these values against them, rather than creating moral standards of our own?

Maybe right now you’re saying to yourself “what do you mean, create moral standards of our own? Something is either morally right or it isn’t—morality isn’t something you can make up, it’s not a matter of mere opinion.” Right there, you’re accepting one of the most basic tenets of the society that raised you: that right and wrong are not individual valuations, but fundamental laws of the world. This idea, a holdover from a deceased Christianity, is at the center of our civilization. If you are going to question the establishment, you should question it first!

Where does the idea of “Moral Law” come from?

Once upon a time, almost everyone believed in the existence of God. This God ruled over the world, He had absolute power over everything in it; and He had set down laws which all human beings had to obey. If they did not, they would suffer the most terrible of punishments at His hands. Naturally, most people obeyed the laws as well as they could, their fear of eternal suffering being stronger than their desire for anything forbidden. Because everyone lived according to the same laws, they could agree upon what “morality” was: it was the set of values decreed by God’s laws. Thus, good and evil, right and wrong, were decided by the authority of God, which everyone accepted out of fear.

One day, people began to wake up and realize that there was no such thing as God after all. There was no hard evidence to demonstrate his existence, and few people could see any point in having faith in the irrational any longer. God pretty much disappeared from the world; nobody feared him or his punishments anymore.

But a strange thing happened. Though these people had the courage to question God’s existence, and even deny it to the ones who still believed in it, they didn’t dare to question the morality that His laws had mandated. Perhaps it just didn’t occur to them; everyone had been raised to hold the same beliefs about what was moral, and had come to speak about right and wrong in the same way, so maybe they just assumed it was obvious what was good and what was evil whether God was there to enforce it or not. Or perhaps people had become so used to living under these laws that they were afraid to even consider the possibility that the laws didn’t exist any more than God did.

This left humanity in an unusual position: though there was no longer an authority to decree certain things absolutely right or wrong, they still accepted the idea that some things were right or wrong by nature. Though they no longer had faith in a deity, they still had faith in a universal moral code that everyone had to follow. Though they no longer believed in God, they were not yet courageous enough to stop obeying His orders; they had abolished the idea of a divine ruler, but not the divinity of His code of ethics. This unquestioning submission to the laws of a long-departed heavenly master has been a long nightmare from which the human race is only just beginning to awaken.

God is dead—and with him, Moral Law.

Without God, there is no longer any objective standard by which to judge good and evil. This realization was very troubling to philosophers a few decades ago, but it hasn’t really had much of an effect in other circles. Most people still seem to think that a universal morality can be grounded in something other than God’s laws: in what is good for people, in what is good for society, in what we feel called upon to do. But explanations of why these standards necessarily constitute “universal moral law” are hard to come by. Usually, the arguments for the existence of moral law are emotional rather than rational: “But don’t you think rape is wrong?” moralists ask, as if a shared opinion were a proof of universal truth. “But don’t you think people need to believe in something greater than themselves?” they appeal, as if needing to believe in something can make it true. Occasionally, they even resort to threats: “but what would happen if everyone decided that there is no good or evil? Wouldn’t we all kill each other?”

Everything that glorifies “God” and the afterworld slanders humanity and the real world.

The real problem with the idea of universal moral law is that it asserts the existence of something that we have no way to know anything about. Believers in good and evil would have us believe that there are “moral truths”—that is, there are things that are morally true of this world, in the same way that it is true that the sky is blue. They claim that it is true of this world that murder is morally wrong just as it is true that water freezes at thirty two degrees. But we can investigate the freezing temperature of water: we can measure it and agree together that we have arrived at some kind of “objective” truth, insofar as such a thing is possible. On the other hand, what do we observe if we want to investigate whether it is true that murder is evil? There is no tablet of moral law on a mountaintop for us to consult, there are no commandments carved into the sky above us; all we have to go on are our own instincts and the words of a bunch of priests and other self-appointed moral experts, many of whom don’t even agree. As for the words of the priests and moralists, if they can’t offer any hard evidence from this world, why should we believe their claims? And regarding our instincts—if we feel that something is right or wrong, that may make it right or wrong for us, but that’s not proof that it is universally good or evil. Thus, the idea that there are universal moral laws is mere superstition: it is a claim that things exist in this world which we can never actually experience or learn anything about. And we would do well not to waste our time wondering about things we can never know anything about.

When two people fundamentally disagree over what is right or wrong, there is no way to resolve the debate. There is nothing in this world to which they can refer to see which one is correct—because there really are no universal moral laws, just personal evaluations. So the only important question is where your values come from: do you create them yourself, according to your own desires, or do you accept them from someone else ... someone else who has disguised their opinions as “universal truths”?

Haven’t you always been a little suspicious of the idea of universal moral truths, anyway? This world is filled with groups and individuals who want to convert you to their religions, their dogmas, their political agendas, their opinions. Of course they will tell you that one set of values is true for everybody, and of course they will tell you that their values are the correct ones. Once you’re convinced that there is only one standard of right and wrong, they’re only a step away from convincing you that their standard is the right one. How carefully we should approach those who would sell us the idea of “universal moral law,” then! Their claim that morality is a matter of universal law is at base just a devious way to get us to accept their values, rather than forging values of our own which might conflict with theirs.

So, to protect ourselves from the superstitions of the moralists and the trickery of the evangelists, let us be done with the idea of moral law. Let us step forward into a new era, in which we will make values of our own rather than accepting moral laws out of fear and obedience. Let this be our new creed:

There is no universal moral code that should dictate human behavior. There is no such thing as good or evil, there is no universal standard of right and wrong. Our values and morals come from us and belong to us, whether we like it or not; so we should claim them proudly for ourselves, as our own creations, rather than seeking some external justification for them.

But if there’s no good or evil, if nothing has any intrinsic moral value, how do we know what to do?

Make your own good and evil. If there is no moral law standing over us, that means we’re free—free to do whatever we want, free to be whatever we want, free to pursue our desires without feeling any guilt or shame about them. Figure out what it is you want in your life, and go for it; create whatever values are right for you, and live by them. It won’t be easy, by any means; desires pull in different directions, they come and go without warning, so keeping up with them and choosing among them is a difficult task—of course obeying instructions is easier, less complicated. But if we just live our lives as we have been instructed to, the chances are very slim that we will get what we want out of life: each of us is different and has different needs, so how could one set of “moral truths” work for each of us? If we take responsibility for ourselves and each carve our own table of values, then we will have a fighting chance of attaining some measure of happiness. The old moral laws are left over from days when we lived in fearful submission to a nonexistent God, anyway; with their departure, we can rid ourselves of all the cowardice, submission, and superstition that has characterized our past.

Some misunderstand the claim that we should pursue our own desires to be mere hedonism. But it is not the fleeting, insubstantial desires of the typical libertine that we are speaking about here. It is the strongest, deepest, most lasting desires and inclinations of the individual: it is her most fundamental loves and hates that should shape her values. And the fact that there is no God to demand that we love one another or act virtuously does not mean that we should not do these things for our own sake, if we find them rewarding—which almost all of us do. But let us do what we do for our own sake, not out of obedience!

But how can we justify acting on our ethics, if we can’t base them on universal moral truths?

Morality has been justified externally for so long that today we hardly know how to conceive of it in any other way. We have always had to claim that our values proceeded from something external to us, because basing values on our own desires was (not surprisingly!) branded evil by the preachers of moral law. Today we still feel instinctively that our actions must be justified by something outside of ourselves, something “greater” than ourselves—if not by God, then by moral law, state law, public opinion, justice, “love of man,” etc. We have been so conditioned by centuries of asking permission to feel things and do things, of being forbidden to base any decisions on our own needs, that we still want to think we are obeying a higher power even when we act on our own desires and beliefs; somehow, it seems more defensible to act out of submission to some kind of authority than in the service of our own inclinations. We feel so ashamed of our aspirations and desires that we would rather attribute our actions to something “higher.” But what could be greater than our own desires, what could possibly provide better justification for our actions? Should we be serving something external without consulting our desires, perhaps even serving against our desires?

This question of justification is where so many otherwise radical individuals and groups have gone wrong. They attack what they see as injustice not on the grounds that they don’t want to see such things happen, but on the grounds that it is “morally wrong.” By doing so, they seek the support of everyone who still believes in the fable of moral law, and they get to see themselves as servants of the Truth. These people should not be taking advantage of popular delusions to make their points, but should be challenging assumptions and questioning traditions in everything they do. An improvement in, for example, animal rights, which is achieved in the name of justice and morality, is a step forward at the cost of two steps back: it solves one problem while reproducing and reinforcing another. Certainly such improvements could be fought for and attained on the grounds that they are desirable (nobody who truly considered it would really want to needlessly slaughter and mistreat animals, would they?), rather than with tactics leftover from Christian superstition. Unfortunately, because of centuries of conditioning, it feels so good to feel justified by some “higher force,” to be obeying “moral law,” to be enforcing “justice” and fighting “evil” that it’s easy for people get caught up in their role as moral enforcers and forget to question whether the idea of moral law makes sense in the first place. There is a sensation of power that comes from believing that one is serving a higher authority, the same one that attracts people to fascism. It’s always tempting to paint any struggle as good against evil, right against wrong; but that is not just an oversimplification, it is a falsification: for no such things exist.

We can act compassionately towards each other because we want to, not just because “morality dictates,” you know! We don’t need any justification from above to care about animals and humans, or to act to protect them. We need only feel in our hearts that it is right, that it is right for us, to have all the reason we need. Thus we can justify acting on our ethics, without basing them on moral truths, simply by not being ashamed of our desires: by being proud enough of them to accept them for what they are, as the forces that drive us as individuals. And our own values might not be right for everyone, it’s true; but they are all each of us has to go on, so we should dare to act on them rather than wishing for some impossible greater justification.

But what would happen if everyone decided that there is no good or evil? Wouldn’t we all kill each other?

This question presupposes that people refrain from killing each other only because they have been taught that it is evil to do so. Is humanity really so absolutely bloodthirsty and vicious that we would all rape and kill each other if we weren’t restrained by superstition? It seems more likely to me that we desire to get along with each other at least as much as we desire to be destructive—don’t you usually enjoy helping others more than you enjoy hurting them? Today, most people claim to believe that compassion and fairness are morally right, but this has done little to make the world into a compassionate and fair place. Might it not be true that we would act upon our natural inclinations to human decency more, rather than less, if we did not feel that charity and justice were obligatory? What would it really be worth, anyway, if we did all fulfill our “duty” to be good to each other, if it was only because we were obeying moral imperatives? Wouldn’t it mean a lot more for us to treat each other with consideration because we want to, rather than because we feel required to?

And if the abolition of the myth of moral law somehow causes more strife between human beings, won’t that still be better than living as slaves to superstitions? If we make our own minds up about what our values are and how we will live according to them, we at least will have the chance to pursue our desires and perhaps enjoy life, even if we have to struggle against each other. But if we choose to live according to rules set for us by others, we sacrifice the chance to choose our destinies and pursue our dreams. No matter how smoothly we might get along in the shackles of moral law, is it worth the abdication of our self determination? I wouldn’t have the heart to lie to a fellow human being and tell him he had to conform to some ethical mandate whether it was in his best interest or not, even if that lie would prevent a conflict between us. Because I care about human beings, I want them to be free to do what is right for them. Isn’t that more important than mere peace on earth? Isn’t freedom, even dangerous freedom, preferable to the safest slavery, to peace bought with ignorance, cowardice, and submission?

The wages of sin are freedom.

Besides, look back at our history. So much bloodshed, deception, and oppression have already been perpetrated in the name of right and wrong. The bloodiest wars have been fought between opponents who each thought they were fighting on the side of moral truth. The idea of moral law doesn’t help us get along, it turns us against each other, to contend over whose moral law is the “true” one. There can be no real progress in human relations until everyone’s perspectives on ethics and values are acknowledged; then we can finally begin to work out our differences and learn to live together, without fighting over the absolutely stupid question of whose values and desires are “right.” For your own sake, for the sake of humanity, cast away the antiquated notions of good and evil and create your values for yourself!

No Masters

If you liked school, you’ll love work. The cruel, absurd abuses of power, the self-satisfied authority that the teachers and principals lorded over you, the intimidation and ridicule of your classmates don’t end at graduation. Those things are all present in the adult world, only more so. If you thought you lacked freedom before, wait until you have to answer to shift leaders, managers, owners, landlords, creditors, tax collectors, city councils, draft boards, law courts, and police. When you get out of school you may escape the jurisdiction of some authorities, but you enter the control of even more domineering ones. Do you enjoy being controlled by others who don’t understand or care about your wants and needs? Do you get anything out of obeying the instructions of employers, the restrictions of landlords, the laws of magistrates, people who have powers over you that you would never have given them willingly?

How is it that they get all this power, anyway? The answer is hierarchy.

Hierarchy is a value system in which your worth measured by the number of people and things you control, and how dutifully you obey those above you. Weight is exerted downward through the power structure: everyone is forced to accept and conform to this system by everyone else. You’re afraid to disobey those above you because they can bring to bear against you the power of everyone and everything under them. You’re afraid to abdicate your power over those below you because they might end up above you. In our hierarchical system, we’re all so busy trying to protect ourselves from each other that we never have a chance to stop and ask if this is really the best way our society could be organized. If we could think about it, we’d probably agree that it isn’t; for we all know happiness comes from control over our own lives, not other people’s lives. And as long as we’re busy competing for control over others, we’re bound to be the victims of control ourselves.

It is our hierarchical system that teaches us from childhood to accept the power of any authority figure, regardless of whether it is in our best interest or not. We learn to bow instinctively before anyone who claims to be more important than we are. It is hierarchy that makes homophobia common among poor people in the U.S.A.—they’re desperate to feel more valuable, more significant than somebody. It is hierarchy at work when two hundred punk rockers go to a rock club (already a mistake, of course!) to see a band, and for some stupid reason the clubowner won’t let them perform: there are two hundred and six people at the club, two hundred and five of whom want the band to play, but they all accept the decision of the clubowner just because he is older and owns the place (i.e. has more financial power, and thus more legal power). It is hierarchical values that are responsible for racism, classism, sexism, and a thousand other prejudices that are deeply ingrained in our society. It is hierarchy that makes rich people look at poor people as if they aren’t even human, and vice versa. It pits employer against employee, manager against worker, teacher against student, making people struggle against each other rather than work together in mutual aid; separated this way, they can’t benefit from each other’s skills and ideas and abilities, but must live in jealousy and fear of them. It is hierarchy at work when your boss insults you or makes sexual advances at you and you can’t do anything about it, just as it is when police flaunt their power over you. For power does make people cruel and heartless, and submission does make people cowardly and stupid: and most people in a hierarchical system partake in both. Hierarchical values are responsible for our destruction of the natural environment and the exploitation of animals: led by the capitalist West, our species seeks control over anything we can get our claws on, at any cost to ourselves or others. And it is hierarchical values that send us to war, fighting for power over each other, inventing more and more powerful weapons until finally the whole world teeters on the edge of nuclear annihilation.

But what can we do about hierarchy? Isn’t that just the way the world works? Or are there other ways that people could interact, other values we could live by?

Hierarchy ... & Anarchy; Resurrecting anarchism as a personal approach to life.

Stop thinking of anarchism as just another “world order,” just another social system. From where we all stand, in this very dominated, very controlled world, it is impossible to imagine living without any authorities, without laws or governments. No wonder anarchism isn’t usually taken seriously as a large-scale political or social program: no one can imagine what it would really be like, let alone how to achieve it—not even the anarchists themselves.

Instead, think of anarchism as an individual orientation to yourself and others, as a personal approach to life. That’s not impossible to imagine. Conceived in these terms, what would anarchism be? It would be a decision to think for yourself rather than following blindly. It would be a rejection of hierarchy, a refusal to accept the “god given” authority of any nation, law, or other force as being more significant than your own authority over yourself. It would be an instinctive distrust of those who claim to have some sort of rank or status above the others around them, and an unwillingness to claim such status over others for yourself. Most of all, it would be a refusal to place responsibility for yourself in the hands of others: it would be the demand that each of us not only be able to choose our own destiny, but also do so.

According to this definition, there are a great deal more anarchists than it seemed, though most wouldn’t refer to themselves as such. For most people, when they think about it, want to have the right to live their own lives, to think and act as they see fit. Most people trust themselves to figure out what they should do more than they trust any authority to dictate it to them. Almost everyone is frustrated when they find themselves pushing against faceless, impersonal power.

You don’t want to be at the mercy of governments, bureaucracies, police, or other outside forces, do you? Surely you don’t let them dictate your entire life. Don’t you do what you want to, what you believe in, at least whenever you can get away with it? In our everyday lives, we all are anarchists. Whenever we make decisions for ourselves, whenever we take responsibility for our own actions rather than deferring to some higher power, we are putting anarchism into practice.

So if we are all anarchists by nature, why do we always end up accepting the domination of others, even creating forces to rule over us? Wouldn’t you rather figure out how to coexist with your fellow human beings by working it out directly between yourselves, rather than depending on some external set of rules? The system they accept is the one you must live under: if you want your freedom, you can’t afford to not be concerned about whether those around you demand control of their lives or not.

Do we really need masters to command and control us?

In the West, for thousands of years, we have been sold centralized state power and hierarchy in general on the premise that we do. We’ve all been taught that without police, we would all kill each other; that without bosses, no work would ever get done; that without governments, civilization itself would fall to pieces. Is all this true?

Certainly, it’s true that today little work gets done when the boss isn’t watching, chaos ensues when governments fall, and violence sometimes occurs when the police aren’t around. But are these really indications that there is no other way we could organize society?

Isn’t it possible that workers won’t get anything done unless they are under observation because they are used to not doing anything without being prodded—more than that, because they resent being inspected, instructed, condescended to by their managers, and don’t want to do anything for them that they don’t have to? Perhaps if they were working together for a common goal, rather than being paid to take orders, working towards objectives that they have no say in and that don’t interest them much, they would be more proactive. Not to say that everyone is ready or able to do such a thing today; but our laziness is conditioned rather than natural, and in a different environment, we might find that people don’t need bosses to get things done.

And as for police being necessary to maintain the peace: we won’t discuss the ways in which the role of “law enforcer” brings out the most brutal aspects of human beings, and how police brutality doesn’t exactly contribute to peace. How about the effects on civilians living in a police-“protected” state? Once the police are no longer a direct manifestation of the desires of the community they serve (and that happens quickly, whenever a police force is established: they become a power external to the rest of society, an outside authority), they are a force acting coercively on the people of that society. Violence isn’t just limited to physical harm: any relationship that is established by force, such as the one between police and civilians, is a violent relationship. When you are acted upon violently, you learn to act violently back. Isn’t it possible, then, that the implicit threat of police on every street corner—of the near omnipresence of uniformed, impersonal representatives of state power—contributes to tension and violence, rather than dispelling them? If that doesn’t seem likely to you, and you are middle class and/or white, ask a poor black or Hispanic man how the presence of police makes him feel.

When the standard forms of human interaction all revolve around hierarchical power, when human intercourse so often comes down to giving and receiving orders (at work, at school, in the family, in the courts), how can we expect to have no violence in our society? People are used to using force against each other in their daily lives, the force of authoritarian power; of course using physical force cannot be far behind in such a system. Perhaps if we were more used to treating each other as equals, to creating relationships based upon equal concern for each other’s needs, we wouldn’t see so many people resort to physical violence against each other.

And what about government control? Without it, would our society fall into pieces, and our lives with it?

Certainly things would be a great deal different without governments than they are now—but is that necessarily a bad thing? Is our modern society really the best of all possible worlds? Is it worth it to grant masters and rulers so much control over our lives, out of fear of trying anything different?

Besides, we can’t claim that we need government control to prevent mass bloodshed, because it is governments that have carried out the greatest slaughters of all: in wars, in holocausts, in the centrally organized enslavement and obliteration of entire peoples and cultures. And it may be that when governments break down, many people lose their lives in the resulting chaos and infighting. But this fighting is almost always between other power-hungry hierarchical groups, other would-be governors and rulers. If we were to reject hierarchy absolutely and refuse to serve any force above ourselves, there would no longer be any large scale wars or holocausts. That would be a responsibility each of us would have to take on equally, to collectively refuse to recognize any power as worth serving, to swear allegiance to nothing but ourselves and our fellow human beings. If we all were to do that, we would never see another world war again.

Of course, even if a world entirely without hierarchy is possible, we should not have any illusions that any of us will live to see it realized. That should not even be our concern: for it is foolish to arrange your life so that it revolves around something that you will never be able to experience. We should, rather, recognize the patterns of submission and domination in our own lives, and, to the best of our ability, break free of them. We should put the anarchist ideal—no masters, no slaves—into effect in our daily lives however we can. Every time one of us remembers not to accept at face value the authority of the powers that be, each time one of us is able to escape the system of domination for a moment (whether it is by getting away with something forbidden by a teacher or boss, relating to a member of a different social stratum as an equal, etc.), that is a victory for the individual and a blow against hierarchy.

Do you still believe that a hierarchy-free society is impossible? There are plenty of examples throughout human history: the bushmen of the Kalahari desert still live without authorities, never trying to force or command each other to do things, but working together and granting each other freedom and autonomy. Sure, their society is being destroyed by our more warlike one—but that isn’t to say that an egalitarian society could not exist that was extremely hostile to, and well-defended against, the encroachments of external power! In Cities of the Red Night, William Burroughs writes about an anarchist pirates’ stronghold a few hundred years ago that was just that.

If you need an example closer to your daily life, remember the last time you gathered with your friends to relax on a Friday night. Some of you brought food, some of you brought entertainment, some provided other things, but nobody kept track of who owed what to whom. You did things as a group and enjoyed yourselves; things actually got done, but nobody was forced to do anything, and nobody assumed the position of master. We have these moments of non-capitalist, non-coercive, non-hierarchical interaction in our lives constantly, and these are the times when we most enjoy the company of others, when we get the most out of other people; but somehow it doesn’t occur to us to demand that our society work this way, as well as our friendships and love affairs. Sure, it’s a lofty goal to ask that it does—but let’s dare to reach for high goals, let’s not settle for anything less than the best in our lives!

“Anarchism” is the revolutionary idea that no one is more qualified than you are to decide what your life will be.

» It means trying to figure • out how to work together to meet our individual needs, how to work with each other , rather than “for” or against each other. And when this is impossible, it means preferring strife to submission and domination.

» It means not valuing any system or ideology above the people it purports ‘to serve, not valuing anything theoretical above the real things in this world. It means being faithful to ‘ real human beings (and animals, etc.), fighting for ourselves and for each other, not out of “responsibility,” not for “causes” or other intangible concepts.

» It means not forcing your desires into a hierarchical order, either,, but accepting and embracing all of them, accepting yourself. It ‘ , means not trying to force the self to abide by any external laws, not trying to restrict your emotions ‘ to the predictable or the , practical, not pushing your instincts and desires into boxes: for there is no cage large enough to accommodate the human soul in all its flights, all its heights and depths.

» • It means refusing to put the responsibility for your happiness in anyone else’s hands, whether that be parents, lovers, employers, or society itself. It means taking the pursuit of meaning and joy in your life upon your own shoulders.

For what else should we pursue, if not happiness? If something isn’t valuable because we , find meaning and joy in it, then what could possibly make it important? How could abstractions like “responsibility,” “order,” or “propriety” possibly be ‘more important than the real needs of the people who invented them? Should we serve , employers, parents, , the State, ‘ God, capitalism, moral law, causes, movements,’ “society” before ourselves? Who taught you that, anyway?

{throughout the medieval era} THE BRETHREN OF THE FREE SPIRIT

Across almost two millennia, the Catholic Church maintained a sranglehold over life in Europe. It was able w do this because Christianity gave it a monopoly on the meaning of life: everything that was sacred, everything that mattered was not to be found in this world, only in another. Man was impure, profane, trapped on a worthless earth with everything beautiful forever locked beyond his reach, in heaven.* Only the Church could act as an intermediary to that other world, and only through it could people approach the meaning of their lives.

Mysticism was the first revolt against this monopoly: determined to experience for themselves a taste of this otherworldly beauty, mystics did whatever it took— starvation, self-flagellation, all kinds of privation—to achieve a moment of divine vision: to pay a visit to heaven, and return to tell of what blessedness awaited there. The Church grudgingly accepted the first mystics, privately outraged that anyone would sidestep its primacy in all communication with God, but believing rightly that the stories the mystics told would only reinforce the Church’s claims that all value and meaning rested in another world.

But one day, a new kind of mysticism appeared; those who practiced it were generally known as the Brethren of the Free Spirit. These were men and women who had gone through the mystical process, but returned with a different story: the identification with God could be permanent, not just fleeting, they announced. Once they had had their transforming experience, they felt no gulf between heaven and earth, between sacred and profane, between God and man. The heretics of the Free Spirit taught that the original sin, the only sin, was this division of the world, which created the illusion of damnation; for since God was holy and good, and had made all things, then all things truly were wholly good, and all anyone had to do to be perfect was to make this discovery.

Thus these heretics became gods on earth: heaven was not something to strive towards, but a place they lived in; every desire they might feel was absolutely holy and beautiful, and not only that—it was the same as a divine commandment, more important than any law or custom, since all desires were created by God. In their revelation of the perfection of the world and themselves, they even were able to go beyond God, and place themselves at the center of the world: accepting the Church’s authority and objective world view had meant that if God had not invented them, they would not exist; but now, accepting their own desires and perspectives as sovereign, and therefore asserting their own subjective experience of the world as the only authority, they were able to see that if they had not existed, then God would not exist.

The book of Schwester Katrei, one of the sources that remains from these times, describes one woman’s pursuit of divinity through this kind of mysticism; at the end, she announces to her confessor, in words that shook the medieval world: “Sir, rejoice with me, for I have become God.”

The Brethren of the Free Spirit were never a movement or an organized religious group; in fact, they resembled CrimethInc. more than any group since has. Their secrets were spread through the world, among people of all classes, by humble wanderers who traveled from one land to the next seeking adventure. These were vagabonds who refused to work not out of selfdenial but because they proclaimed that they were too good for work, as they suggested anyone else could be who wanted to; accordingly, they declined to spend their lives selling their beliefs, as so many traditional Christians (and Communists, and even anarchists) do, but rather concentrated on living them—which proved, of course, to be far more infectious.

Of course the Catholic Church responded to this heresy by slaughtering the Brethren by the thousands. Anything less than a campaign of all-out terror would have sealed its fate, as its authority was almost entirely undermined by this new liberating theology. Despite the violence of this repression, however, the secrets of the Free Spirit were passed on across vast measures of time and space; they traveled unseen and uncharted, through corridors hidden to history (perhaps because they consisted of moments lived outside of history?), to appear in social explosions and near-revolutions hundreds of years and thousands of miles apart.1 On many occasions the power of the Church and the nations that served it was almost broken by these seemingly spontaneous uprisings; they appear throughout official history like a heartbeat in a sleeping body.

The heretics of the Free Spirit managed to reach a state of total self-confidence and empowerment that we anarchists and feminists only dream of today; that they managed to do this using the raw materials of Christianity, traditionally such a confining and crippling religion, is truly amazing. I often think that if only we could cast away all our doubts and inhibitions and really feel that what we are is beauty and perfection (must be, if such concepts are to exist at all!), and what we want is nothing to fear or be ashamed of, we would become invincible and the world would be ours forever more.

* Even today, Christianity teaches that whatever is worthy about you is God’s, and whatever is imperfect about you is your own failing—thus we have existence of our own only to the extent that we are flawed and shameful.

See also: the Ranters, the Diggers, the Anabaptists, the Antinomians, etc.

{early 1600’s} THE PAUPER KINGS OF THE SEA

During the early seventeenth century the port city of Sale on the an coast became a shaven for pirates from all over the world,eventually evolving into a free, protoanarchist state that attracted, among others, poor, outcast Europeans who came in droves to begin new lives of piracy preying upon the trade ships of their former home countries. Among these European Renegadoes was the Dread Captain Bellamy; his hunting ground was the Straits of Gibraltar, where all ships with legitimate commerce changed course at the mention of his name, often to no avail. One Captain of a captured merchant vessel was treated to this speech by Bellamy after declining an invitation to join the pirates:

I am sorry they won’t let you have your sloop again, for I scorn to do anyone a mischief, when it is not to my advantage; damn the sloop, we must sink her, and she might be of use to you. Though you are a sneaking puppy, and so are all those who submit to be governed by laws which rich men have made for their own security; for the cowardly whelps have not the courage otherwise to defend what they get by knavery; but damn ye altogether:

damn them for a pack of crafty rascals, and you, who serve them, for a parcel of hen-hearted numbskulls. They vilify us, the scoundrels do, when there is only this difference, they rob the poor under the cover of law, forsooth, and we plunder the rich under protection of our own courage. Had you not better make then one of us, than sneak after these villains for employment?

When the captain replied that his conscience would not let him break the laws of God and man, the pirate Bellamy continued:

You are a devilish conscience rascal, I am a free prince, and I have as much authority to make war on the whole world as he who has a hundred sail of ships at sea, and an army of 100,000 men in the field, and this my conscience tells me; but there is no arguing with such snivelling puppies, who allow superiors to kick them about deck at pleasure.

B is for the Bourgeoisie

Raise the double standard of living!

[adapted from George Orwell’s Homage to Catatonia]

the Discreet charm of the BOURGEOUISE; Or, the Tyranny of the Hair Dryer

Does your father drift from one hobby to another, fruitlessly seeking a meaningful way to spend the little “leisure time” he gets off from work? Does your mother endlessly redecorate the house, going from one room to the next until she can start over at the beginning again? Do you agonize constantly over your future, as if there was some kind of, track laid out ahead you—and the world would end if you turned off of it? If the answer to these questions is yes, it sounds like you’re in the clutches of the bourgeoisie, the last barbarians on earth.

The Martial Law of Public Opinion

Public opinion is an absolute value to the bourgeois man and woman because they know they are living in a herd: a herd of scared animals, that will turn on anyone it doesn’t recognize as its own. They shiver in fear as they ponder what “the neighbors” will think of their son’s new hairstyle. They plot ways to seem even more normal than their friends and coworkers. They don’t dare fail to turn on their lawn sprinklers or dress appropriately for “casual Fridays” at the office. Anything that could drag them out of their routines is viewed as suspect at best. Love and lust are both diseases, possibly fatal, as are all the other passions that could drive one to do things that would result in expulsion from the flock. Keep them quarantined to secret affairs and teenage dates, to night clubs and strip clubs—for God’s sake, don’t contaminate the rest of us. Go wild when “your” football team wins a game, drink yourself into oblivion when the weekend comes, rent obscene movies if you have to, but don’t you dare sing or run or make love out here. Under no circumstances admit to feeling anything that doesn’t belong in the staff room or at the dinner party Under no conditions admit to wanting anything more or different than what “everyone else” wants, whatever and whoever that might be.

And of course their children have learned this, too. Even after the death matches of the grade school nightmare, even among the most rebellious and radical of the nonconformists, the same rules are in place: don’t confuse anybody as to where you stand. Don’t use the wrong signifiers or subscribe to the wrong codes. Don’t dance when you’re supposed to be posing, don’t speak when you’re supposed to be dancing, don’t mess with the genre or the moves. Make sure you have enough money to participate in the various rituals. To keep your identity intact, make it clear which subcultures and styles you’re aligned to, which bands and fashions and politics you want to be associated with. You wouldn’t dare risk your identity, would you? That’s your character armor, your only protection against certain death at the hands of your friends. Without an identity, without borders to define the edges of your self, you’d just dissolve into the void ... wouldn’t you?

The Generation Gap

The older generations of the bourgeoisie have nothing to offer the younger ones because they have nothing in the first place. All their standards are hollow, all of their riches are consolation prizes, not one of their values contains any reference to real joy or fulfillment. Their children sense this, and rebel accordingly, whenever they can get away with it. The ones that don’t have already been beaten into terrified submission.

So how has bourgeois society continued to perpetuate itself through so many generations? By absorbing this rebellion as a part of the natural life cycle. Because every child rebels as soon as she is old enough to have a sense of self at all, this rebellion is presented as an integral part of adolescence—and thus the woman who wants to continue her rebellion into adulthood is made to feel that she is insisting on remaining a child forever. It’s worth pointing out that a brief survey of other cultures and peoples will reveal that this “adolescent rebellion” is not inevitable or “natural.”

This perpetual rebellion of the youth also creates deep gulfs between different generations of the bourgeoisie, which play a crucial role in maintaining the existence of the bourgeoisie as such. Because the adults always seem to be the enforcers of the status quo, and the youth do not have the perspective yet to see that their rebellion has also been absorbed into that status quo, generation after generation of young people are able to make the mistake of identifying older people themselves as the source of their misfortunes rather than realizing that these misfortunes are the result of a larger system of misery. They grow older and become bourgeois adults themselves, unable to recognize that they are merely replacing their former enemies, and still unable to bridge the so-called generation gap to learn from people of other age groups ... let alone establish some kind of unified resistance with them. Thus the different generations of the bourgeoisie, while seemingly fighting amongst themselves, work together harmoniously as components of the larger social machine to ensure maximum alienation for all.

The Myth of the Mainstream

The bourgeois man depends upon the existence of a mythical mainstream to justify his way of life. He needs this mainstream because his social instincts are skewed in the same way his conception of democracy is: he thinks that whatever the majority is, wants, does, must be right. Nothing could be more terrifying to him than this new development, which he is beginning to sense today: that there no longer is a majority, if there ever was.

Our society is so fragmented, so diverse, that at this point it is absurd to speak of a “mainstream.” This is a myth partly created by the anonymity of our cities. Almost everyone one passes on the street is a stranger: one mentally relegates these anonymous figures to the faceless mass one calls the mainstream, to which one attributes whatever properties one thinks of strangers as possessing (for the smug salesman, they all envy him for being even more respectable than they are; for the insecure bohemian rebel, they must disapprove of him for not being like they all are). They must be part of the silent majority, that invisible force that makes everything the way it is; one assumes that they are the same “normal people” seen in television commercials. But the fact is, of course, that those commercials refer to an unattainable ideal, in order to keep everyone feeling left out and insufficient. The “mainstream” is analogous to this ideal, as it keeps everyone in line without ever actually making an appearance, and possesses the same degree of reality as the perfect family in the toothpaste advertisement.