Darren Allen

Self and Unself

[Front Matter]

[Title Page]

[Copyright]

Published by Expressive Egg Books

www.expressiveegg.org

Copyright © 2021 Darren Allen. All rights reserved.

Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the prior written permission of the publisher.

First published in 2021, in England

Darren Allen has asserted his moral rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Front cover illustration by Ai Higaki.

ISBN: 978-1-8384073 3 9 (hardback)

ISBN: 978 1 8384073 0 8 (paperback)ISBN: 978 1 8384073 1 5 (ePub)Also available for Kindle.

Disclaimer: the author and publisher accept no liability for actions inspired by this book.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Acknowledgements

This book is dedicated to the memory and spirit of Ivan Illich, Arthur Schopenhauer and Barry Long.

I would also like to thank the people who generously donated to my fund-raiser to help me take the time to write this book. Particular thanks to Antony Floyd, Scott Newman, Jake Reilly, Jeanne Campos, Philip Cade and, of course, Ai Higaki. ‘Imagine a large castle on an island, with almost inescapable dungeons. The jailor has installed every device to prevent the prisoners escaping, and he has taken one final precaution: that of hypnotizing the prisoners, and then suggesting to them that they and the prison are one. When one of the prisoners awakes to the fact that he would like to be free, and suggests this to his fellow prisoners, they look at him with surprise and say: “Free from what? We are the castle.” What a situation!’ Colin Wilson, The Outside ‘People can be very different from each other, but their dreams are not, because in their dreams they award themselves the three or four things they desire, sooner or later, to a greater or lesser extent, but they always get them, everyone does; there is no one who seriously dreams himself empty-handed. That’s why no one discovers himself in his dreams.’ Jens Peter Jacobsen, Niels Lyhner

Introduction

Ego made this world. Ego and world are each a metaphor for the other, with a common origin which, when consciously experienced, can free the individual self from both. This experience is neither objective nor subjective — it is what I call panjective — which means it can neither be literally described nor solipsistically moodied up, only gestured towards; by critically exploring what it is not and by metaphorically describing what it is like. This is what the present work does.

To put this another way, reality is ultimately mysterious, a mystery that is everywhere you look — because it is that which is looking. This doesn’t mean that unmysterious thought — the kind that reasons about subjective impressions and objective things — is useless, or that the facts that it handles are illusions. It means that such thought reaches a limit beyond which it cannot pass. Something else has to cross over, a something else which, obviously enough, cannot be expressed with the thought it had to leave behind. If it does think, or reason, or attempt to express itself, it has to do it in another way; through the means of expression we call metaphor. And again, this is what this book aims to do.

·

Although it has to be presented as a linear a-to-b account, every part of the book is both connected to every other part, and also connected to the whole. This means, firstly, that it should be read twice, as only the linear account will be grasped the first time while, the second time, knowledge of what is to come will inform what is bringing the whole into focus. Secondly, some ideas presented at the beginning, particularly those referring to unself, consciousness and context, will initially appear rather hazy (or confusing, or even unpleasantly abstract). This is because the key terms in this book cannot be literally defined, or at least not all at once, and must either appear later, or ‘reveal themselves’ implicitly, gradually, in the whole. On a second reading, the difficult earlier sections will feel clearer and realer and erroneous objections — and, worse, opinions — will not get in the way.

Opinions have almost nothing to do with experience. You can have an opinion about love and death, but only while you’re not experiencing them. So it is with everything of importance that I cover in this book. Please put your opinions aside as you read, not in order to blindly accept what I have to say, but to ensure that your experience is not filtered by second-hand ideas, as so often happens, particularly when reading a critique of that filtering mechanism.

This filtering mechanism is the self. It is a kind of psychological tool which has taken over the consciousness of mankind and become what we call ego. Ego doesn’t like to be criticised and employs various strategies to deal with the threat of criticism. Its usual response is to ignore the threat, ridicule it, drown it out with opinion or attempt to refute it with some kind of ‘reasoning’; an avalanche of facts disconnected from the point. But because ego is not merely conceptual, but also affective, it will start to feel under attack before it has discovered the intellectual reason why. Something will feel ‘off’, something not quite right here. Ego will then start looking for reasons why it feels uncomfortable. It will find sentences it does not understand and accuse the author of being pretentious, or deliberately obfuscating, or a poor stylist. It will look for and find evidence that the author is not properly qualified to speak, or it will look for, and again find, inconsistencies in the system here presented and dismiss the whole thing as factually incorrect woo, or it will take ideas out of context and accuse the author of being racist, sexist, homophobic, hypocritical or downright evil. Ego will find these reasons, and it will then declare that the reasons have created the feelings, when the opposite is true, as it nearly always is. Nobody ever reacts negatively to a truthful philosophy because of what it says, but because of how it makes them feel.

·

Some parts of this book are quite difficult. It demands some effort, particularly at the beginning, where I have had to outline the metaphysical foundations and explain the key terms that follow in the [lighter, and more entertaining] main body of the work. Metaphysics is, actually, straightforward and enjoyable. One reason it appears, particularly for us in the West, difficult, dense and abstract, is because we are forced to talk about it in a language that has been degraded by thousands of years of unconscious use. This language has to be unpicked or reimagined, which doesn’t always make for easy reading, particularly after a hard day’s work.

I have been forced to use some ordinary words in a new way — chief among these self and ego (and ‘selfish’ which has a much broader meaning here that it usually does) but also various value-laden words, such as beauty, truth, sanity, love, quality and so on, along with a few less common technical words, such as physicalism and solipsism, all of which also have here a much wider meaning than they normally do. I have also invented a few new terms, such as unself (that which is not self), panjective (that which is neither objective nor subjective), and nous, soma, thelema and viscera (terms taken from Greek and Latin and adapted to describe the various fundamental elements of the self). Once you get a feel for these terms, the reading will be more agreeable.

That said, I have largely used language as it comes. This means that, as with all ordinary language, what I have to say takes its meaning not from diamond-like logical precision, but from the context — from the context that we share, and from the context of what I am saying in this particular book. I must therefore ask for a charitable interpretation of what I am saying; which of course is how friends communicate.

We are unlikely to be friends if you are in the habit, as many are, of taking language to be reality, or of taking language as it comes to be an adequate representation of reality. My criticism of ideas and attitudes which are not real will then appear to be an intolerable attack on reality — or perhaps on the real people who hold these ideas and attitudes, or perhaps on you? — and my reimagined, contextually oriented language will appear to be quite outrageous, perhaps unsettling, as if reality itself is being rearranged. This will give you an irresistible urge to view what you disagree with as opinion (what you agree with will seem like cold, hard, obvious fact), and counter what I say with opinion — your own opinion, mass-opinion, expert-opinion, dictionary-opinion, rich-and-famous-opinion — or you’ll zero in on inconsistencies, or on the style of my writing, or on me, in order to ‘prove’ me wrong, or to win an internal argument.

In the end, it is better that people who find my style annoying, or who are already starting to feel a bit put out, stop reading as soon as possible; that those who are offended by my use of ‘man’ to refer to ‘humanity’ (because it is stylistically superior) give up in a huff; that those who wish to enjoy a beautiful view, but aren’t prepared to burn a few calories to do so, don’t bother climbing; that literalists (atheists and theists, rationalists and empiricists, physicalists and idealists) give up trying to literally understand the non-literal truth of what I say; and that readers who are attached to their beliefs and personalities, and who feel swelling outrage when they read an attack on all beliefs and personalities, throw the book out the window. It is better that the easily offended, and the aggressively contentious, and the entirely conventional, and the completely rational, and the completely irrational read books that they agree with, that are popular, that sell well, that are ‘of the time’. I haven’t written Self and Unself for them. In fact I have deliberately written a book that is out of step, not just with the time this time, but with time itself; because I only wish to speak with people who are. Even if there are only the two of us.

Map

·

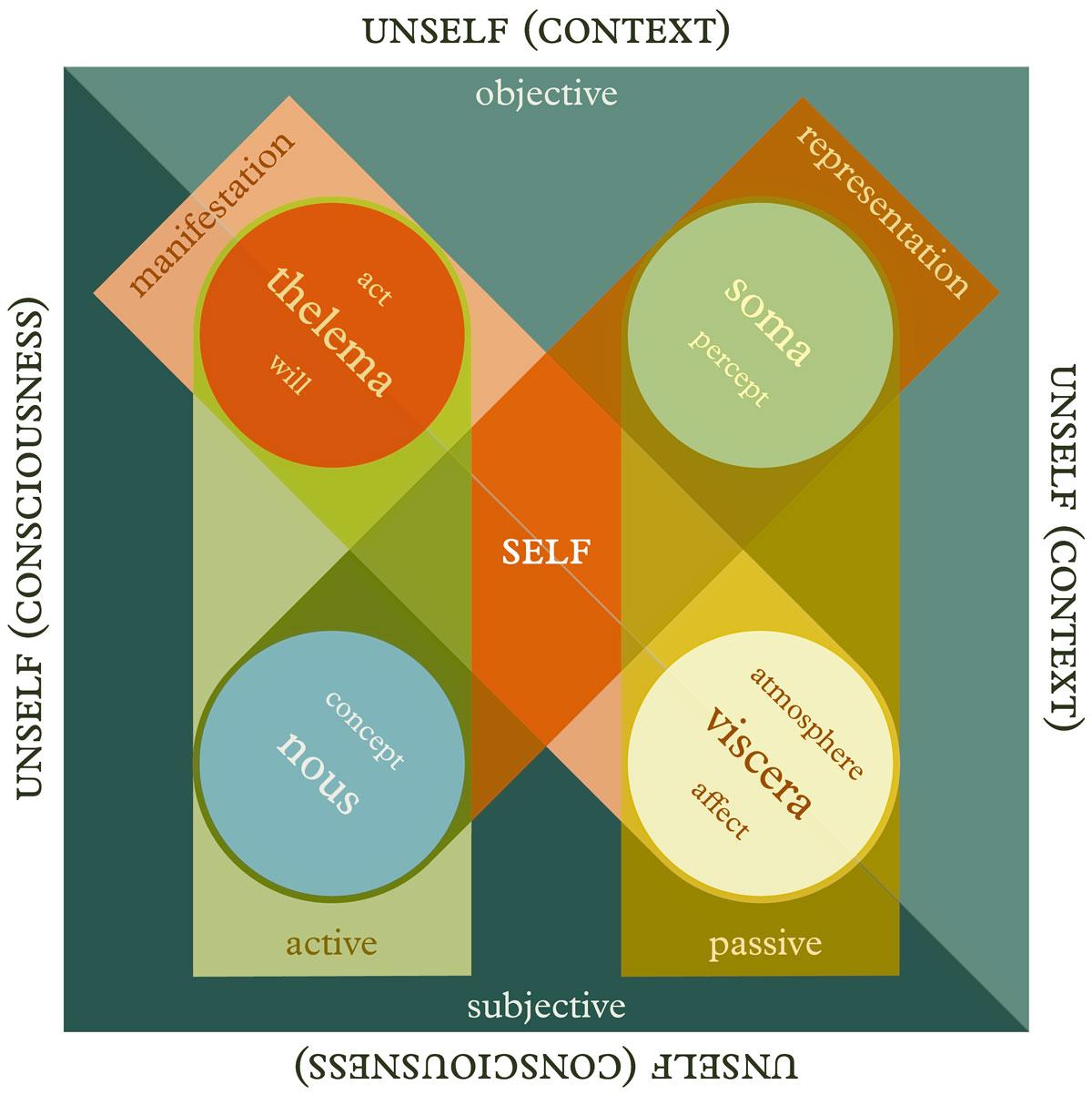

Self can be said to be composed of four modes (or modalities). The boundaries between them are not fixed and definite, but we can say that soma comes to us as body, sensation, perception or matter, nous appears as thought, idea, conception or mind, viscera as feeling, affection, psyche or atmosphere and thelema as will, energy, action or movement.

These modalities can be divided into three sets of poles (or polarities): subjectivity and objectivity, activity and passivity, and manifestation and representation.

Maps represent the knowable parts of a terrain in knowable relation to each other. In this they are useful. This map, however, shows the knowable self in relation to something which is unknowable; unself. Such a relation must, therefore, not be taken literally, but as a metaphor. All references to such metaphorical “relationships” in this book are enclosed in double “scare quotes”.

Self and Unself

There are true flowersin this painted world

§1.

There is a self here reading these words, which I call me. It is a caused, three-dimensional fact existing in what I call space and passing through or changing in what I call time.

The ‘purpose’ of the self is to generate the world-for-me from the world-in-itself. The experienced world of the self is not of reality as it actually is, but is an image or reflection of reality, a representation or manifestation of something else.

This something else that representations and manifestations are “of” is inaccessible to the self. It appears to self either as an unfathomable distal context, “beyond” objective representation, or it appears as an unfathomable proximal consciousness, “behind” self experience.

Self, in other words, does not and cannot know who I really am or what anything really is. Self can only know its own medial experience. Anything else — if there is anything else — is “beyond” or “behind” a wall which self cannot surmount.

§2.

Self, by itself, can never be sure what its representations and manifestations are of. It can be sure enough that, for example, another self exists (which I call you or it) and it can be sure enough about where you or it comes from (God perhaps, or a granule of DNA), but it can never know what you really are or what anything really is. To the extent that I am a self, I am effectively imprisoned. Even though you are obviously somehow a self like me, even though the carpet is still obviously somehow a thing like me, you and it are still only actually being experienced within my self. What you and it really, finally are is, ultimately, inaccessible to the self.

This is reasonably obvious for so-called secondary properties, such as hardness or colour. It’s clear to most people that the green of the grass, for example, is not the actual green, but an interpretation in the mind; of light-frequency data that comes to the mind through the optic nerve. We do not see light frequencies, we see, or self experiences, colour. We do not hear vibrations in the air, we hear, or self experiences, sound. Frequencies and vibrations exist independently of mind, but there is no such thing as an ‘unheard sound’ or an ‘unseen colour’ because sounds and colours are functions of mind. If a tree falls in a forest and there’s nobody around to hear, it obviously makes something — but that something, equally obviously, cannot be our experience of sound.

This doesn’t mean secondary properties are completely invented by the mind. There is, quite clearly, a fundamental connection between our experience of green, in here, and the actual nature of the light, out there, ‘bouncing off’ an oak leaf, or between the crashing sound we hear when a tree falls, and the actual sound waves rocking through the air. This is how we all know, despite fanciful philosophical speculation, that we are sharing the same world of greeny greens and crashy crashes. We all know that our senses are almost completely reliable; but we also know that, somehow, they are not; that there is a personal aspect to sensory experience. Even so-called realists concede that mind somehow creates experience from sensation; that the self doesn’t just report, it also interprets. This is clear to most people, which is why it forms the basis of practically every theory of perception ever proposed. Far less clear, far more difficult to accept, is the idea that the self generates our experience of the primary property of literality.

§3.

Literalism is the belief or experience (the former arising from the latter) that representations are analogous or abbreviated expressions of knowable things. For the literalist, the noetic tree (the idea, word or symbol that represents tree) and the somatic tree (that big, beautiful brown and green thing over there) are fundamentally the same as the actual tree; as the ‘tree-in-itself’. Literalist definitions can be flexible and literalist logics can be ‘fuzzy’, but all forms of literalist thought and expression are completely or essentially knowable (describable as an idea, or thinkable in symbolic thought, or graspable as an emotion) and founded on the assumption — and it only ever can be an assumption — that reality is also, in the same way, knowable. There is, in other words, nothing elusive, ineffable or mysterious about the literalist tree; the eye can see it, the mind can know it, the heart can like or want it.

Self-generated objective literality can be said to comprise two equally unmysterious, comprehensible laws; the law of facticity and the law of causality. Facticity means that every thing must either be a literal thing or a literal non-thing (x is either x or not-x) and causality means that every literal thing must have been literally caused by some other thing (If x then y), all these things known, and only quantitatively known, in their relation to one other, which is to say relatively.

The whole ordinary world, what the self calls ‘the real world’, is a massive collection of caused facts existing within, and related to each other by, the self. Self, in other words, generates space and time. As with secondary properties of sound and colour, the fact that this experience is ‘generated’ doesn’t mean that it’s invented, that there isn’t something literally ‘spacetimey’ out there, that the tree my mind thinks of and the tree my mind sees are illusions, or that factual and causal relations are a battery of ad hoc assumptions and arbitrary inventions, or that mathematics and logic are entirely subjective, or that the word ‘literally’ is literally meaningless. Only an abstract philosopher or postmodern artist or complete madman could seriously believe that an unperceived tree, or planet, or Pharaoh, does not exist at all, or that language and logic are literally meaningless, or that there is no difference between dreams and waking reality. The fact that you are reading these words and that you even approximately understand them is almost indisputable evidence that something mind-graspable exists beyond your self. All manifest communication would be impossible — including communication with completely new cultures — if there weren’t something in reality which was literal, that we unquestionably share. What the self-made nature of literality means is that ultimately self doesn’t, and cannot, take literal, factual, causal experience from the world: it brings literal experience to the world.

§4.

Self does not learn objective literality like it learns the individual facts and causes that comprise it, for self is itself a literal thing. The spatial position of my subjective self, its experience of your objective self, the causal relation of that experience to who you actually are, the relation of you to him, to her, to them, to it… all of these relations somehow exist out there, but their literalness, their ‘graspableness’, is a function of the inherent, fundamental nature of self, not ultimately learnt from anything external to self. It is clearly the case that self can be said to somehow learn facticity and causality. A developing baby does learn to separate thing from thing, object from subject, babself from mumself; but it evidently does not, and cannot, learn this from facts and causes, the existence of which are presupposed by the very self that is grasping them.{1} How can self learn facticity and causality from experience of the world, when facticity and causality are the essential prerequisites for that experience? How can you learn that objects are separate from each other in space, without first being able to separate objects from one another? How can we ever be sure that perception and conception provide us with an accurate picture of the world, without relying on perception and conception?

What self does learn from experience are secondary properties; the causal facts, or factual causes, that make up the world. Because these are acquired, they can be lost by self or, in the case of impaired selves, not acquired at all. You can be born blind to light and colour, but you cannot be born blind to time and space. Likewise, secondary properties can be experimentally ‘thought away’; self can imagine an object without position, colour, form, substance and state, but, as Immanuel Kant pointed out,{2} it can never think away the primary properties of facticity and causality. It can neither perceive nor conceive of a factless, causeless object because it is born with this understanding ‘hardwired’ into perception and conception. Our experience of space and what we call ‘time’ would be impossible unless we brought facticity and causality to our experience. There is no way even to imagine how it could be otherwise.

§5.

What then is the nature of reality, “behind” the literal, objective representation of self? What, that is to say, is the nature of the thing-in-itself{3}? Self alone only has two options. Either it can concede that self cannot experience the thing-in-itself (or deny that it exists at all); in which case anything goes. This is the position of the solipsist, or subjectivist, for whom everything is self. The other option is to assume that although the thing-in-itself, the universe “beyond” me, is fundamentally unreachable, it is still essentially and entirely literal. This is the position of the physicalist, or objectivist.

Although physicalists and solipsists are constantly at odds, and although both positions are superficially distinct, they are fundamentally the same. The reality of the solipsist is subjectively literal — there is nothing “prior” to the subjectivities of the self — just as the reality of the literalist is objectively so — there is nothing “beyond” the objects of the self. Thus we can speak of solipsism and physicalism as distinct, but they are, ultimately, both self-located, or egoic worldviews; which is why each, two poles on the same continuum, ultimately entails the other. Objectivity at its subjectless extreme collapses into complete, solipsistic, subjectivity — for all I can actually find in the objects of self’s experience is self, or self-generated representation — while subjectivity in turn, at its limits, reveals total objectivity — for if I am the world in toto, there can be no [objectively] validated I to be found in that world, no true consciousness; just a chaos of objective bits.

Egoism — solipsistic / physicalist literalism — began at some point towards the end of the Palaeolithic era, with what we call idealism and dualism, the semi-literal / semi-solipsist idea that reality (for the idealist) literally is, or (for the dualist) is somehow caused or magically animated by, mind (or by ‘soul’ or ‘God’). The normal word for idealism-dualism today is superstition or, in its most extreme form, religion. Around five hundred years ago the useless magical element was ditched in favour of what we now call ‘physicalism’ (also known as ‘materialism’ or, more absurdly, ‘realism’), the idea that reality is a fully literal thing, which self — specifically the rational mind — can indirectly access. Today, we usually call physicalism science or, in its most extreme form, scientism.

§6.

Scientism is an extreme form of literalism, but some form of literalism has been the assumed foundation of all institutional thought since institutions began, around 6,000 years ago. There are, however, four catastrophic problems with literalism and all the scientific-religious philosophies built upon it;

i. Self can never know what lies beyond its reach in space, if anything does, because self creates space. It cannot judge its own reliability without first presupposing it. Self just proceeds as if the thing-in-itself out there matches the literal representation it experiences in here. For the literalist, an essentially comprehensible universe walks into the self where it is literally doubled as my experience of it.{4} Self then assumes that what it generates as space and time reflects a universe that fundamentally is spatio-temporal. The literalist can never be sure if this is so — if there isn’t something else, beyond its grasp — so he has to assume it. Not because, as he declares, this modus operandi ‘works’ (indeed and of course it does) but because he has to assume it. He has no choice; the literal self can only experience meter readings (its own, or those of the tools it builds), which means that the literalist must posit a miraculous ghost world beyond experience to explain what those readings are of; if, that is, he seriously reflects on such matters, which is rare. Vague gestures towards ‘God’, ignoring the question of what anything actually is, or pretending it is meaningless to ask such questions are more common, all of which allow the modern assumption that the objective universe is as it appears to rest without question.

The physicalist in particular is forced to cling to the ‘meter reading’ view of the universe — to assume that the meter readings of the self accurately reflect objective reality — even when they inform him that he is in error. Physicalist philosophers believe that philosophy should limit its claims to what the natural sciences can discover — that philosophy is really just a preliminary stage, or ‘handmaiden’, to the ‘real’ work of the physicalist scientist. But when, in the first half of the twentieth century, those same scientists discovered that ultimately [quantum] reality cannot be literally grasped by the self, their discoveries were effectively ignored. The problems that physicalist thinkers endeavour to solve, such as the relation between mental and physical phenomena, are implicitly founded on a literal logic that has been discovered, by the same science they uphold, to be incompatible with ‘objective’ reality.

ii. Just as the literal self cannot know what lies beyond spatial representation, so it is incapable of grasping the cause of its experience in what it calls time. It has no idea of how facticity and causality — a.k.a. the universe — could have causally emerged from non-facticity and non-causality; because it can have no idea. This is not a question of ‘not knowing’ something, of not yet having the right theory or enough data. There is no way to think about how time and space could ‘emerge’ from non-time and space; and so literalists just ignore the matter, or focus on the measurable effects of this ‘emergence’ or, again, they posit miracles to explain it. While theist literalists are quite open about this, informing us that [an equally literal] ‘God’ created the universe, atheist literalists, embarrassed by magic, prefer either to wave the problem away with ‘well it must have happened’ and pretend that this happening can’t have been miraculous, or they sneak causality into their assumptions, using words like ‘happen’, ‘came to be’ and ‘emerge’ to describe the source of causality itself. But however the miracle is framed, a miracle remains the only way for literalists to explain or accept the incoherent absurdity — at the heart of both standard modern theism and standard modern atheism — that causelessness caused causality.

iii. Literalism cannot explain the cause of experience, or what it calls ‘consciousness’. For the literalist, consciousness somehow emerged from non-consciousness; conscious human beings somehow emerged from unconscious rocks and amoebae (‘phylogenetically’), and conscious adults somehow emerged from unconscious chromosomes and embryos (‘ontogenetically’). But again, there is no way even to think about how this could happen; how something non-experiential can possibly generate experience (or, alternatively, how quantity can generate quality) without reducing the latter to the former. We can imagine, and so predict, how sand-dunes can ‘emerge’ from sand, or ice from water, or ecological breakdown from human activity. There is something quantitatively detectable in the latter which conceivably, or scientifically, leads to the former. But there is nothing in non-experience that can conceivably lead to experience or predict its emergence. Qualitative consciousness ‘emerging’ from quantitative matter is as feasible as language emerging from biscuits. It’s not merely amazing that it happened (the so-called ‘argument from incredulity’ which physicalists are very eager to dismiss) but impossible to imagine that it could happen, at least causally; so the literalist just says ‘God did it’ or, these days, ‘emergentism did it’, which amounts to the same thing.

This leaves two further puzzles for the literalist. One is how the material mind can cause immaterial consciousness, and the other is how non-physical consciousness can influence physical matter. These, the so-called ‘mind-body problem’ and ‘problem of mental causation’, are insoluble mysteries for literalists. They come up with plenty of theories (or souls or gods) that they think can explain them, but none addresses the inherent absurdity of the problems, which is why nobody has come anywhere near answering them. Those answers which are offered all beg not one but two questions; the first is what the matter is that mind is supposed to influence or emerge from, which remains impregnable to, and untouched by, any kind of literalism, and the second is what the consciousness is that experiences that matter, which is either declared to be a quantitative, literal thing like any other literal thing or to be an ‘epiphenomenal illusion’, which is to say, to not exist at all.

iv. The fourth literalist enigma is literal, objective knowledge itself, or rational thought, which is assumed, from the beginning of the literal, objective world, to have a fundamentally one-to-one correspondence with reality. But how is the literalist to know? How can literal thought determine whether literal thought is literally representing reality? Just as there can be nothing within an android that can validate whether it is conscious, so there can be nothing within rational thought that can validate thinking itself. One can only judge the accuracy of thought, meaning the fundamental thinkableness of reality, by experiencing from a standpoint “external” to rationality, but this is something the literalist cannot do.

This problem (called the ‘no independent access’ problem{5}) cripples the progress of physicalist understanding that modern literalists appeal to. How is one to further knowledge, or discover a more elementary law than those which currently obtain, unless one steps out of the known and introduces a new hypothesis which is ultimately unrelated to the interconnected network of perceptions and conceptions that physicalism is based on? This, one of the great mysteries of science, is unsolvable by science, because you have to make a non-literal leap over the factual-causal fence in order to do so. Immanuel Kant, Henri Poincaré, Albert Einstein and Max Planck all made this point, as did, in a different way, David Hume{6}, who argued that experience can never lead to reliable general principles, because such principles rest on a dependable regularity which can never be found in experience. We can never be completely sure that the next swan we come across won’t be bright red. While we remain within the coordinates of the knowable we can never be sure that the laws of nature don’t change or evolve, or that an untested hypothesis (of which there are an infinite number) doesn’t more accurately fit the facts. Hume himself was driven to despair by his famous ‘problem of induction’, because it invalidates scientific certainty; which is, once again, why physicalists pretend that it doesn’t exist or is of no importance.

·

Extreme literalists — physicalists — consider the universe to be entirely composed of separate comprehensible parts, particles or granules relating to each other in predictable ways in order to produce a measurable outcome; that the universe, or reality, is, like the self, a kind of machine. They are unable to view reality as something non-mechanical, something which, despite clearly having a literal machine-like component, is also ultimately, unpredictable, immeasurable, spontaneous and uncaused; the state of experience we call alive.

Perhaps, you might think, the physicalist considers the mechanistic universe to be just a metaphor? But if that’s the case, why is it preferred over an organic metaphor? Or maybe it is literally true; but then how are we to know? What kind of test could be devised to confirm such a theory? How could it ever be refuted? Of course it could not. There is no way, ever, to test whether the world is mechanical with mechanical tests, any more than rationality can determine whether rationality can, ultimately, know the world.

Literalism is founded on facticity and causality, but is unable to explain how non-facticity and non-causality could have created facticity and causality — how the universe, consciousness, experience or knowledge came to be — for the transparent reason that it is impossible; and so all literalists, of whatever stripe, have to posit miracles to explain it, or redefine the problem out of existence, or knock up a smokescreen of philosophical-technical jargon to hide their ignorance, or, the most common approach, just pretend it doesn’t exist (management never addresses consciousness, politicians never mention the universe and the word ‘ineffable’ is never heard in the lab), proceeding as if consciousness is either an illusion, or a literal material object inhabiting an essentially comprehensible clockwork universe that just happened.

This bizarre reality, a conscious universe spontaneously springing from the head of Zeus, mirroring in some equally fantastic way a reality that can never be directly experienced, is the one that most people in the world inhabit today. Nobody seriously explores the nature or the limits of this make-believe ideology, our ‘worldview’, at least not at work. It is assumed to be the only explanation of the universe, although that assumption cannot itself be literally justified without getting sucked into a tautologous mindwarp — you can’t literally prove that literal proof is the only method of discovering truth without automatically ruling out non-literal methods. Thus, all non-literal accounts of reality are not reasoned away, but reflexively dismissed — as insane forms of subjectivist solipsism.

§7.

Solipsism is the only way to reject physicalism within the confines of the self. The solipsist denies objective facticity and causality, either rationally concluding (as Hume, one of the godfathers of modern solipsism, did) that neither can be found in the world, or irrationally dismissing them as forms of control by external agencies (souls, gods, governments, aliens, them). Instead of the factual and the causal, the solipsist adheres to the unreal and the arbitrary; a subjective reality which has no objective counterpart, and therefore is based on random choice, personal whim or whatever association (association, based on similarity, being ‘solipsistic causality’) is at hand.

The extreme solipsist — the schizophrenic — is confined to a catatonic universe of self-generated illusion, but most solipsists can function perfectly well in the world without retreating to an inner world of concepts. The high-functioning solipsist inhabits the same egoic world as the physicalist, making the same literal distinction between the inner subject and the outer object, but solipsistic meaning is handed over to the subject in order to serve the temporary needs of ego, which frequently demands that rationality, objectivity and causal reason be abandoned so that it can justify itself and lie to others.

While orientation towards the objective-world of physicalism is favoured by businessmen, managers, scientists and men, the subjectivity of solipsism is the preferred philosophy of liars, artists, addicts and women. The former require a useful representation of the world which they can rationally defend, the latter a useless representation which they can irrationally defend. Because both are essentially egoic — essentially the same — and because life is a complex affair, self can leap from one to the other, choosing which to adhere to over the course of a life, or even a day. A man may be a rational literalist in class, a semi-rational solipsist in Church, a practical literalist in the office, an airy-fairy solipsist at the guitar or in the art-gallery, an android-like physicalist when he is arguing with his wife and a self-absorbed hyper-idealist when he has a breakdown and just can’t take it anymore.

§8.

If there is something else in reality, something in the thing-in-itself that is not physically or solipsistically self, then it can neither be represented by self nor make sense to it. If, that is to say, there is something in reality that is inaccessible to a self which is either a literal object or an unreal subject, then that something else must be both object and subject, both non-literal and real. Here, this is called panjective.

Non-literal means non-factual, or paradoxical (x is both x and non-x) and real means not self-generated; it is uncaused (x is always x). Panjective reality is, therefore, absolute, meaning that it is real but is not ‘known’ through the quantitative relations of its literal factual-causal parts. If the thing-in-itself is in any way absolute, self can create self-graspable perceptions, conceptions, affections and motions “from” it, but there is something in the thing-in-itself “beyond” both objective knowledge, or fact, and subjective knowledge, or invention.

The absolute nature of the thing-in-itself doesn’t just mean that it is ultimately ineffable to self, but that its “relationship” to the world is also ineffable.{7} Self can say that the thing-in-itself spatially “precedes” or temporally “causes” the experience of self — self can express itself dualistically — but if the thing-in-itself is somehow unselfish, then such dualism can only ever be non-literally, or metaphorically, true; for, ultimately, there can be no relation between reality and representation.

These are rather unusual ideas. If, ultimately, reality is absolute, there is not just ‘something else’ in the thing-in-itself, forever beyond the relative self, there must also, somehow, be nothing but something else. If there are ultimately no separate facts and no separate causes (or factual associations) — no time and space in the thing-in-itself — there can be, ultimately, no difference between anything and anything else, which means that, again, ultimately, there can be no difference between me and the rest of the universe, at any time.

This literally unbelievable idea is, you would think, easy to verify. If I look around and find that I am surrounded by separate things which are not each other and not me — things which include the entire past and future of the universe — then I can probably conclude that I am not all things at all times, that I am ‘just me’, my ordinary self. The question, however, is not what I am ‘looking around’ at, but what the ‘I’ is that is doing the looking. It may be obvious that my self is not everything else, but it is far from obvious that I am my self.

§9.

Who am I? It is such a simple question, and yet I keep getting it wrong. I get it wrong by looking for, and finding, answers. There can be no definitive self-knowable answer to the question ‘who am I?’ because self only has its own experience to judge by. If I am somehow “more” or “other” than self, self cannot know it, any more than a torch can ‘know’ darkness.

The torch of self can reason itself to the limits of its light — it can know it cannot know beyond a certain point — but it cannot experience what lies beyond what it knows, for, self-evidently, self cannot be what it is not, any more than torch-light can be dark. Self therefore, by itself, concludes that either there is nothing beyond the known, or, if there is, that there is nothing beyond the known that is not self-like.

It is night and a drunk man is looking for his keys in a pool of light under a street lamp. A friend comes along and asks him what he is doing. ‘I’m looking for my keys’, he says. ‘Where did you drop them?’ the friend asks, and the man points into the darkness. ‘Over there’, he says. ‘Over there? Then why aren’t you looking over there?’ ‘Because’, says the drunk man, ‘the light is here’.{8}

This famous allegory more or less describes the activity of self, which looks with self for something other than self; because ‘that’s where the light is’. The difference being that ‘the light’ doesn’t just limit what self sees, but what it is — and therefore can see. Self, by itself, is identified with the ‘light’ of the noetic, visceral, thelemic and somatic self, and so it cannot say, of the object of its search, that it is in the darkness because, for the self, there is no such thing. If the story were to continue it would end with the drunkard and his friend arguing about the existence of the night.

Self does not conclude that the universe is entirely self-like by inspecting facts and causes — or ‘evidence’ — because facticity and causality are, despite accurately applying to self-like aspects of the thing-in-itself, ultimately self-made. There can be no fact or cause within self that can determine whether facticity completely applies to reality “beyond” self. Because self can only inspect facts, and strings of causal (or associative) reason, it can only assume that reality beyond its representation is completely factual and causal. This assumption forms the sand-like foundation of all egoic, literalist, philosophies, whether physicalist, solipsist, dualist or idealist.

§10.

Everything that self experiences is a representation of something else which is ultimately an inaccessible mystery to it, to me. Self must therefore guess whether that mystery is actually mysterious, or if it just seems so because it is inaccessible. Self can be completely confident about that within the thing-in-itself which is knowable, but it can never know whether there is something “within” the thing-in-itself that is unknowable, because it cannot step outside of itself and experience, or be, that which its meter readings are of.

With one exception. There is one thing-in-itself in the universe, and only one, that I do not need to ‘read’ from the meter of the self to experience, one thing-in-itself in the universe that I can be, that I am, immediately and directly, that I do not have to go via my self to experience, and that is consciousness, the experience or state I call I.

I am, unquestionably, the one thing in the entire universe that I have direct, inward access to. I am the only thing in the universe which is that which representation is of. I am the consciousness which self — the entire apparent universe — only ever appears to. I, like every other thing-in-itself, appear or manifest as self, but, ultimately, I qualitatively “precede” quantitative self-perception, self-conception, self-facticity and self-causality. Ultimately, to put it simply, I am not my self.

I am unself.

§11.

If literalism holds, unself is just inaccessible self. They are essentially the same, except that the former is out of reach. Modern literalists sometimes call such an out-of-reach self the ‘unconscious’, a hidden realm said to mysteriously influence the functioning of self. This inaccessible subjective realm ‘inside’ of self is conceived of in the same way as the inaccessible objective realm ‘outside’ of self, which is to say, once again, literally. We can deductively piece the bits of the unconscious together by psychoanalytically studying its effects, but we can never access it directly, and therefore can never be sure what it literally is, or even, rather more seriously, if it literally is.

If, however, the literalist account of the thing-in-itself is fundamentally false, if there is anything non-literal about the unselfish thing-in-itself of self, then it is somehow non-factual and non-causal. Not completely non-factual and non-causal; something “within” the thing-in-itself must be isolable, factual and causal — representable — otherwise nothing would make sense. It is only through our connection with a vast and interconnected, coherent and completely dependable tapestry of facts, sewn together with causal threads, that we know with total confidence that we are not dreaming. But there is no reason to suppose that consciousness is entirely literal or indeed entirely inaccessible; reasons themselves are accessible, literal things. If the thing-in-itself that I am transcends literality, then it must somehow be both paradoxical and uncaused (or unthinkable and eternal), and if it is somehow paradoxical and uncaused, then there must, first of all, somehow be no separation between the unself that I am here, which I call consciousness, and the unself that everything is there, which I call context. Even more extraordinarily, there must somehow also be no separation in space or time between the unself that I am here and now and every “other” unself in the universe out there. Ever.

Thus, although the fact that I am the only thing in the universe I can access from within appears to be solipsism, nothing that appears to the imagination can ever be an accurate idea or image of unself. The idea that ‘my unself is every other unself’ may evoke in the imagination of the self a fabulous — bordering on insane — literal image of separate glowing minds conglomerating in some kind of single solipsistic gas, but only by literally cutting off consciousness (here) from the [imagined] context (there). If, however, literalism doesn’t hold, then I am somehow one with the context, with the entire universe; the absolute opposite of solipsism. In fact it is the self, which can only ever experience itself, which is, or inevitably terminates in, extreme solipsistic subjectivism.

If unself is in any way non-literal, it must be the case that consciousness and context are one, but there is no thing ‘here’ and ‘now’ which merges with, or turns out to be the same as, a thing ‘there’ and ‘then’, because there are no separate things; there are no other things, no prior things and no subsequent things. This leaves the solid, real, reliable, shared representation of the objective world, and the personal, insubstantial but equally real representation of the subjective world, completely intact, while transcending objective and subjective dominance of that world, allowing something else to take the wheel.

§12.

Self, by itself, rejects unself. Somatically, self takes unself to be invisible, non-factual, supernatural and impossible to locate in the world (either in the objective, literal world or in the subjective, solipsistic world). Noetically, self finds unself inconceivable, contradictory, absurd and indistinguishable from fantasy, invention, madness and even fascism. Viscerally, self is irritated, bored, confused or disturbed by unself, and all talk of it, whether meaningful or meaningless. Self doesn’t have to try and react in this way, or to deny that unself exists by appealing to the ideas, sensations, feelings and actions of self, any more than it has to try or learn to experience caused facts in space. Self, insofar as it is only self, automatically rules out unself. It cannot experience something else essentially different to itself any more than an ear can hear the colour blue. For the dualist self something else does exist — a soul, or a ‘mind’ — but it is self-like (i.e. not something else), while, for the physicalist and the idealist, nothing else exists; there is just self. In both cases, if there is something else, self alone cannot experience it. Unself can no more exist to self than a fact or idea within a dream can prove the existence of a waking world; if I have never been awake. Only knowledge of a consistent, objective waking world can throw an inconsistent, subjective dream world into doubt. Without the former there is no standard by which to judge the reality of the latter.

Imagine a blind man who believes that colour is a conspiracy. He hears talk of colour, but he refuses to believe it really exists. Or imagine a deaf man who watches people listen to music, smile with pleasure or get up and dance to it. He constructs a theory that music is a kind of electricity that makes people restless, that twitches their faces and jerks their muscles. ‘Well yes’, you might say, ‘so it is; but that electricity has quality, like the lovely colours you see in a beautiful painting or the lovely odour from baking bread’. And then, from your metaphor, he will understand. But what if he is blind to quality? Like an alien, or a manager, who doesn’t understand humour? Then what metaphor can you offer to bridge the gap?

Likewise, because for self everything within the world is a fact caused by another fact, there can be no place within this world for ‘radical initiation’ — an uncaused act of free will — so self must either assume that such acts are impossible, or impute them to some literal thing beyond the world. As self can find no evidence within the world for this literal thing, it must either spin it from its own imagination, which is to say invent a divine being, or soul, which freely causes what we experience, or dismiss that same being or soul, along with free-will, as a ridiculous fantasy. When free will is viewed through the lens of self — sensually, rationally, verbally, emotionally — it vanishes. It cannot exist, because the matter of self is subject to the same inevitable causality as all matter.{9}

This difference between an unspeakable freedom of consciousness “within” self and world, and a comprehensible determinism reigning as self and world, is why the former is so much more obvious to us (unless of course we wish to blame someone or something for our fears, lies and vices; then we’re suddenly, helplessly, unfree), while the latter must be arrived at by intellectual effort. It’s also why when we attempt to articulate our instincts for freedom, the importance of it, we often run up against ‘reasonable objections’ which miss the point; by being reasonable. Take, as an example, the demand for free speech. As soon as it becomes explicit, we find we do not want literal ‘freedom’ to shout ‘fire’ in a packed space when there is no fire, or literal ‘freedom’ to incite mass murder, or literal ‘freedom’ for people to rain mindless abuse down upon our heads; ‘freedom’, that is to say, for self to say what it wants. The freedom of speech we demand is for consciousness to be able to say what it pleases, no matter what explicit form it takes. The lawmakers of the egoic world cannot tell the difference, which is why they ban the word ‘fire’, while allowing panic to spread by non-literal means.

Self, therefore, can never discover freedom. It can only discover slavery. If free will exists it can only be in the absence of self; meaning the absence of causality, and therefore compulsion, and in the absence of facticity, and therefore boundary; which is to say, in unselfish consciousness.

§13.

When self talks about consciousness, it is only ever talking about self; self-willed attention to the percepts, concepts, affects and actions of self. When literalist philosophers of mind use the term ‘consciousness’, they are usually referring to egoic focus on some thing; an isolated sensation, feeling, thought or act. When self investigates attention, or focused awareness, it finds only a series of disconnected sensations, feelings, thoughts and acts. It then logically concludes that ‘really’ no unified or “prior” consciousness exists. This is like a man who walks around a room looking for himself, closely inspecting everything, realising that each thing in the room is not him, and then finally concluding that he’s not really there.

The room is unself; the thing-in-itself which appears to me from within as consciousness and from without as the context, which I consciously experience. Self focuses on, picks out or isolates bits of the thing-in-itself — things or facts — into its spatial attention. These things are not just subjective, coming from within the body (volition, conception, affection) or objective, coming from without (action, character, perception) but subjectivity and objectivity (factual-causal separation) are themselves brought into being by the isolating activity of self. The objective form of the world (its primary and secondary qualities — its colours, flavours and states, and its factual-causal existence in space) is not just created by, or is indistinguishable from, the subject; the difference between subject and object itself comes into being through the activity of the self. The corresponding subjective attention of the self — the thinking, feeling and willing that I experience as a knower — may ‘come from’ or be a ‘result’ of the various objective things of the world, which are, to the self, the known, but before the self forms, when I am extremely young, or when self is softened or suppressed, there is no knower and known, no subject and object, just a felt totality in which that and thou are indistinguishable from I and me. In such a state, I experience unself as the one and only, as nature’s sole, ontological and essentially unknowable primitive.

§14.

When self looks for consciousness or context — for unself — it only ever finds parts; perceptions and conceptions, things and facts, ideas and expressions, subjects and objects. It can no more find the whole than a bitmap image or mosaic can display a continuous gradient. The harder the ‘bit-making’ self looks for unself, the more confused it gets. Eventually it concludes that only functional bits exist, which is to say; a unified unselfish consciousness and context do not exist.

Self creates subjects and objects from unself, then asks whether consciousness and context are subjective or objective — for that is the only question it can ask — which automatically disposes of unself. If unself is objective, then it can be discovered with scientific method; which means it’s a thing, which means it’s not unself. If it is subjective, then it can be whatever you like, which means it’s not real. Physicalist philosophers and scientists are forced to conclude that unself does not exist, that consciousness is ‘really’ isolating attention upon a ‘bundle’ of self-modes which we take to be consciousness, that the context is ‘really’ a collection of things which the mind grasps piecemeal. For the physicalist, what we ‘really’ experience are elements of the mechanical self, not anything like a unified operating consciousness or an unfathomable present, which are illusions. The possibility that both subjectivity and objectivity are “secondary” to a “preceding” consciousness eludes the literalist; he cannot imagine that although measurable objective brain activity logically correlates with subjective states of self, and vice versa — for they are the inner and outer states of the same thing — both are, ultimately, the “result” of something else which can be detected by neither. We cannot find this something else with the subjective or objective self any more than a torch can find a shadow; it is only by switching off the torch that darkness ‘appears’.

Solipsists, equally blind to the unifying whole of contextual-conscious experience — but rejecting literalist accounts of a reliable objective world — are forced to conclude that consciousness does exist, but that it is all me; all my literal self. For the solipsist what you really experience is an unknowable illusion. You might believe you exist in a reliable world, just as a torch might believe it creates light, but, says the solipsist, really your entire self is sustained by my ‘electricity’ (or by that of various symbolic / associative substitutes for me, such as God, the devil, the Rothschilds, the right, the left, etc., etc.).

Such accounts can make nothing of either the actual experience of a unified consciousness which transcends subjectivity and objectivity, or the evident necessity for one. Conscious experience (meaning heightened conscious experience) requires no object (it arises for no reason) and decreases subjectivity (it takes you out of yourself). What’s more, not only do we experience reality from a unified I, but we couldn’t possibly make sense of experience without it. Without a continuous sense of I, subjective and objective experience would be fractured into static shards, or a nightmarish flip-book of isolated moments with no identity threading through them, everything real, all too horrifically real, yet muffled in a soup of incoherent pointlessness. In fact, some people do have this experience. In fact, many people do.

§15.

There is no actual division anywhere in the universe of the self, no dividing line that can be found between solipsist subject and physicalist object, or between nous, soma, viscera and thelema. Self makes these divisions, as it makes divisions between red and yellow, or between the whiteness of the snow and its softness, or between the feathers of a cockatoo and its squawk, or between language and meaning. Really there is just the inscrutable whole of the colour, snow, cockatoo and communication. The philosopher who puzzles over self-generated divisions is like a man looking at a hundred photos taken over the course of a stranger’s life and wondering how all these ‘different’ people are related. ‘They must be related’, he thinks, ‘look how similar they all are!’

Self creates a universe of isolated facts, causally connected and conceptually related to each other, and knitted into a world of knowledge which it then takes to be, in principle, the same kind of thing as reality. It’s not just that the map is taken to be the terrain, but that the self must consider the terrain to be essentially map-like. What the map is actually of cannot be found on it, and neither can the person reading it, nor why he is travelling at all. Looking for something non-symbolic on a map is the very essence of madness.

Arthur Schopenhauer made a related point about the facts revealed by scientific investigation, the various conceptually named percepts of the self, which we can grasp as things related to other things, but never that to which these things appear, or from which they originate. The world of science, Schopenhauer said,{10} is like a party comprising innumerable guests to which I am presented with introductions along the lines of ‘this lady is that man’s auntie, and that man is her friend, and those two are his children…’ Meanwhile I think to myself, ‘yes, yes, but what the devil do they all have to do with me?’ ‘Me’, in this case, is my consciousness, with which such facts have, for me, nothing ‘to do’, for the simple reason that, finally, their relationship to me does not exist. It is ‘picked out’ from experience as a finger is picked out from an arm. The philosopher then comes along and then wonders what this bizarre finger is — this ‘consciousness’, this ‘meaning’, this ‘truth’ — and how it is related to the arm. Indeed this — continual puzzlement over maps for lands that nobody lives in — is philosophy, or rather abstract philosophy in the Western tradition, the activity of a mind writhing in the coils of a series of insoluble riddles brought about by the autonomous existence of the very mind that is trying to unravel them.

§16.

Abstract philosophy is the exclusive use of the thinking mind to find truth. This doesn’t just mean working out problems in the head, but also perceiving abstractly; seeing and hearing the world divided up noetically, through the ‘screen’ of the thinking mind, and assuming that this divided representation is the world. This activity is so common that you’d be forgiven for thinking that the world it presents is reality, just as you’d be forgiven for thinking that all reasoning about it is philosophy.

Abstract thinking about abstract experience is the only thing that happens in universities and just about the only thing you’ll find in the philosophy section of a bookshop or library. When people use the word ‘deep’, they’re usually thinking of the kind of difficult ideas that abstract philosophers talk about. Not that anyone really knows what abstract philosophers talk about, because what they say is extremely boring, absurdly difficult, irrelevant to ordinary life or outrageously self-absorbed, so nobody pays any attention to it.

Abstract philosophy is difficult, boring and pointless because, first of all, abstract philosophers are really only writing for other abstract philosophers, which is like chefs who only make food for other chefs, or doctors who only heal other doctors; and secondly, because they rely exclusively on the thinking mind to understand truth, which is like relying exclusively on cookbooks to understand food, or textbooks to understand the human body. It’s fair to say that most philosophers, psychologists and cognitive scientists believed and still believe — either explicitly or implicitly — that abstract reason and reality are more or less the same thing, that consciousness is thinking or self reflection, that only thought can grasp the essence of reality, that the essence of things is literally a form of thought, or that there is no point of view outside of reason from which reason can be judged. Even so called sceptics and empiricists, who appear to be focusing on the so-called sensory world and doubting the power of the mind to reveal that world, do so through the filter of standard, abstract, reasoning and isolating perception, which creates the isolated things they then reason about. If something cannot be conceived, if it is paradoxical, or silent, or eternal, then it can be, and is, dismissed out of hand.

This is why so many philosophers are baffled by reality. They take experiences which cannot be completely reduced to thought, think about them, and then find their thoughts perplexing. One of the earliest philosophers, for example, Zeno of Elea, who lived around 2,500 years ago, was a very confused man. He reasoned that no object — an arrow, for example — can ever get anywhere, because there are an infinite number of halfway stages it must first reach en route.{11} A century later, Socrates and his disciple Plato became famous for the vast number of things they were confused about; such as what ‘virtue’ is, what ‘knowledge’ is and what ‘thing’ thought is ‘of’. Eight hundred years later, Augustine of Hippo couldn’t work out where the past and future are, or how time can ever be measured. A thousand years later, it was René Descartes’ turn to be baffled by the contents of his own mind. He split experience into mind and matter and was then mystified by how thought could interact with a non-thinking body; a problem which has menaced professional minds ever since. A hundred years later, Hume couldn’t understand what consciousness was, or morality, or causality, because none of them seem to exist in the objective world.

And so it goes on. There are thousands of cases of the same sort; straightforward affairs made puzzling by thought. Just as management exists in order to solve problems created by management, and teachers exist in order to educate people made stupid by the existence of schools, and technology exists in order to solve problems created by technology, so the source and root of these fanatically rational activities, abstract thinking, sets about trying to philosophically solve problems that it has created by thinking. Zeno’s arrow, like Augustine’s time, is not a series of discrete mind-isolated moments or steps, and Plato’s ‘good’, like Hume’s ‘morality’, is not an abstract idea. They are all brought into existence, like Descartes’ perplexing subjects and objects, by the thinking self. The hyper-focusing mind creates mental objects of will, motion, meaning, the good and so on — it creates knowledge — and then is mystified at how they can be objects; how, for example, as Ludwig Wittgenstein asked, I can ‘know your pain’ — as if it were a nasty drink that I could dip a straw into; or how I can ever remember anything — as if memories were books on shelves that a little man in my mind has to index and retrieve; or how I can ever understand anything anyone says — as if I have to consult a dictionary to ‘look up’ all the words they utter.

The reason that so few philosophers ever criticise this activity, the conversion of experience into ‘knowledge’, into a kind of substance which can be produced and consumed, is that they are its producers and we are its consumers. Knowledge as a thing which can be owned, managed, packaged and consumed, automatically turns it into a scarce resource,{12} which, like any other scarce resource, acquires a value which stigmatises the many, the very many, who cannot get their hands on it. Any thinker who rejects this state of affairs — the iniquitous foundation of the gnosocratic{13} knowledge and ‘education’ industry — is ridiculed, rejected or ignored, or, at best, misunderstood by the academic world.

§17.

What abstract philosophers miss in the activity of abstract thought is that the knowledge they seek to acquire about experience is in experience, which, as their lives and their work demonstrate, they don’t actually find very interesting. They speculate about experience, but they don’t really have any, and so when they use the ‘higher faculty’ of reason to inspect consciousness, for example, or life, they find they are very confused and that they have nothing to say — like a man who empties a box to see what is inside it. In order to convince themselves and others that what they are doing is not an absurd waste of time, they close the box, and then describe it with extremely complicated ideas and arguments so that the reader is unable to guess that the box is actually still empty.

This isn’t to say that valid arguments and proofs are not prodigiously useful, or that reasoning should be abandoned, or that faulty reasoning doesn’t often reveal prejudice or obsession, but, for the most part, formal logic, for all its use (particularly in exposing deliberate attempts to deceive), is not employed by people who wish to understand life, but by those who wish to win arguments. It is perfectly possible to ‘win an argument’ and to ‘devastate an intellectual opponent’ using faultless logic that is based on empty, ridiculous or even insane premises and assumptions (very often sneakily omitted). A philosopher who argues that pederasty helps keep populations down (Aristotle), or that animals are essentially machines (Descartes), or that the only reason we don’t cause pain to other people is because we are scared of revenge (Nietzsche), or that children are born with the innate ideas of carburettor and bureaucrat (Chomsky) or that reality needs fiction to conceal its emptiness (Žižek), is in this respect no different to a boyfriend who argues that he has fallen out of love with his girlfriend because love is a chemical, or a madman who argues that Genghis Khan lives in his fridge. When we say of such people that they have ‘lost their minds’, we mean that they have lost everything but their minds.{14}

§18.

No idea, no reasoning, nothing that the thinking mind can do, has meaning without meaning first being present. It is impossible for an argument to produce any value that isn’t in the premises. If, after a long train of reasoning, I confidently reach a conclusion that, say, the president of the United States is always the wisest man in the country, somewhere in the premises there is an unreasoned assumption about the nature of wisdom (or its absence) which I may develop by thinking, but cannot create by thinking.

There are three consequences of this.

i. All reasoning, philosophical or otherwise, must begin with what are often dismissed as ‘mere’ assumptions and assertions; unreasoned declarations of truth such as ‘consciousness exists and I am it’, or ‘something is happening’ or ‘pain hurts’. Although it is absurd to deny such things, there is no way to ever prove them, or argue them into existence; indeed if they could be proved or disproved they would cease to have any real, qualitative meaning to anyone but an android which, like the abstract philosopher, deals entirely in quantities.

ii. When difficult philosophies are translated into ordinary language they come down to simple assertions that anyone can test for themselves as being true or false (‘childish theories without the charm of childhood’, as Wittgenstein put it{15}); because those assertions didn’t come into being through rational thought. This is why abstract philosophers are reluctant to make simple assertions, or to give clear examples, and why reason cannot bring anyone any closer to a change of heart about their fundamental beliefs. People cannot be reasoned out of base premises that they did not reason themselves into. Devastate every fallacious argument in the world, expose every self-deception, dismantle every misguided or prejudicial worldview and it would make no difference to the assumptions that unfounded beliefs are anchored to. Something other than reason (and emotion) is required.

iii. The third consequence of meaning “preceding” reason is that one of the chief weapons in the abstract philosopher’s armoury, the Mighty Fallacy, ultimately has no bearing on the truth content of a statement. Although classic fallacies are guides to incoherence, their absence does not validate an argument, and their presence does not invalidate it. Presenting personal information as evidence for example (the ‘anecdotal fallacy’), or pointing out that a desired quality exists in the natural world (‘the appeal to nature’) or in traditional culture (the ‘appeal to culture’), or caricaturing a position in order to critique it (the ‘straw man’), or dismissing someone’s position based on their hypocrisy (the ‘appeal to hypocrisy’) may be sloppy or illogical, or apt and carefully reasoned, but in neither case is the truth or falsehood of the premise affected.

·

Value, in the sense of philosophical truth, does not come to us through the activity of abstract philosophy, but through the activity of living.{16} If reasoned argument can never arrive at conclusions that are not somehow contained in the premises, those premises must ultimately come from experience. This is the bedrock of any truth that can be shared, an unspoken agreement that my experience and yours are ultimately the same. Similarly, although error and lies may be prevented from advancing by a philosopher criticising the reasoning of those who went before him, the truth is only advanced when someone brings new qualities to the undertaking, qualities which he has already experienced, prior to any quantitative reasoning. This is why writers and teachers with anything meaningful to say have always led meaningful lives. They are not, first and foremost, impressive writers and teachers, but impressive human beings. It’s also why a philosopher with something meaningful to say usually has more in common with children and animals than with his colleagues.

§19.

The literalist philosopher conflates a unified consciousness with attention; a rational kaleidoscope of self-created parts. He then concludes that ‘consciousness’, like meaning and quality, doesn’t really exist. He correctly reasons, for example, that most somatic activity goes on without attention (I travel to work without realising or remembering anything that happened), that we don’t need attention to learn (which frequently happens without knowing it), to make judgements (which often precede attention) or to act effortlessly (which becomes stilted if I do pay attention to what I am doing), that attention doesn’t seem to have a location (different cultures put it in different parts of the body) and that the objects of attention are only ever a ‘bunch’ of impressions which we are fooled into thinking are experienced by a consistent, persistent self (when I go looking for the self, I never seem to find it). There is no enduring attention says the literalist, again correctly; no unique private self — which pre-civilised cultures rarely recognise — and so, for the physicalist, there is no enduring ‘consciousness’, for the two are, to him, the same. For the dualist, on the other hand, there is an enduring consciousness (which he calls ‘soul’ or something similar), but it literally exists (i.e. is a kind of Magical Mind, or Godself).

The idea that consciousness and attention are fundamentally, qualitatively different is impossible for the literalist to grasp; because he is unconscious. He concludes that consciousness literally does or does not exist, because he cannot stop being a literal self; he cannot ‘soften’, ‘slacken’ or ‘sacrifice’ his self to unself in his actual, as opposed to his merely professional, life. He cannot experience the non-literal, so he assumes it is a literal non-thing or a literal thing. It’s not unlike a compulsive worrier concluding that because he cannot stop thinking and emoting, ‘peace of mind’ either does not exist, or it is a literal thing which he cannot get. All literalists are given to worrying in this way.

§20.

Ultimately, all philosophy has as its subject consciousness, but what philosophers know of consciousness is not a question of what they think about it, what facts they have acquired about it, or what theories they have advanced as to its nature; all of this is to ask about their personal relationship to the objects of consciousness. Consciousness is, self-evidently, what the philosopher is; thus, to actually discover what he knows of it, is to ask the most terrifying question for all academic philosophers; how conscious is this man?

The problems of philosophy arise from the problems that philosophers have in their actual lives. Philosophies all attempt to explain what is, but ‘what is’ to the academic mind of an insensitive bore or to an over-emotional egomaniac is very different to the ‘what is’ of someone who has lived an interesting, meaningful life. Someone who has had to contend with life or death questions in profound experiences of uncertainty, or has sacrificed an ordinary life in order to make something meaningful of their existence, asks very different questions about life to someone who has grown up in an entirely mediated modern household, who was raised by ordinary modern parents in an ordinary modern marriage, who went from being educated in an institution to earning their living from one, who has never really had to mortify themselves, or take any real risks, or face the world as it actually is. Such people are insensitive to the pain of being unconscious — in fact are rewarded for and pacified by it — and so take no meaningful steps towards uprooting or investigating it, which is reflected in the superficial problems they tackle and the superficial conclusions they reach, if any.

This aspect of philosophical truth is repellent to professional philosophers, as it is to all those who do not lead meaningful lives, who are not impressive human beings or who do not wish to be. The idea that a great artist, a great thinker or a great teacher must be a great human being is instantly rejected by mediocre human beings, along with the idea that there can even be such things as ‘greatness’ and ‘mediocrity’. In fact, this rejection makes up much of what abstract philosophers actually say, which, once you’ve battled your way through the forest of intellectual thorns they grow around their tiny plastic castles, turns out in many cases to be little more than ‘quality is an illusion’ or ‘consciousness is an illusion’ or ‘love is an illusion’ or ‘sanity is an illusion’ and similar crude and boring defences against nuance, variation and simplicity. In this they are no different from anyone else, but where ordinary people will use unsophisticated, perhaps even downright childish, reasoning to defend their desolate or cosmetic beliefs, or will refuse to reason, preferring to wave away difficult questions or exterminate those who raise them, philosophers will hide behind specialist language and formidably difficult abstract systems.

§21.

A great thinker does not hammer truth to the wall of the mind with the nails of a system, because he knows in doing so the truth will die. Instead, he presents, filtered through his learning, his conscious experience, either structuring this with an easily understood (and easily discarded) system, or he ignores maps and models altogether. It is life which matters to our greatest philosophers, which is why their work is like life; lucid, vivid and elusive. More like a novel. Great philosophy, taking the principle of nature as its source and subject, is like something in nature, the growth of ivy perhaps, or the song of a wren, or the activity of an ant’s nest; messy perhaps, erratic here and there, but it holds together as one, and it speaks.

Abstract philosophy, by contrast, resembles a power-tool; well reasoned, internally coherent, but lifeless, humourless and mechanical. It is conspicuously bereft of interesting examples or meaningful metaphors from life, or even a sense that life, the living reality we humans are part of, is anywhere involved, for the simple reason that abstract philosophers do not really live. If they started addressing life, putting in examples and metaphors from it, the chronic poverty of their lives would be instantly exposed, and that won’t do. Better to rumble on and on about matters of no interest or concern to anyone but dried up philosophical bean-counters.

Academic philosophers spend most of their lives in institutions. They are institutionalised, and paid to manufacture justifications for an institutional — which is to say, hyper-specialised and unreal — existence. This is why they never have anything to say in any other medium, or even any other field. Nothing creative, certainly, nothing personal or human that would enable you to experience that from which such qualities arise, their character or our context (the world that appears in the work of professional philosophers is completely unrecognisable to anyone who is on the receiving end of it). It’s also why you so very rarely get the sense reading philosophy that there is a real human being behind the words, an individual who lives in the real world, a friendly companion. It’s the same with the science that so much philosophy trails after, where use of the word ‘I’ evokes a sense of shame, masquerading under an almost obsessive need to be ‘objective’.

The individual, the selfless I, is irrelevant to matters of fact, and that, we are told, is what we are dealing with here. Except it isn’t, is it? Philosophy is not primarily about matters of fact, but about the ultimate “cause” and quality of those facts. Philosophy is supposed to address itself to pressing questions of existence, to the reality and nature of consciousness, love, art, beauty, god, self, sex, death, creativity, madness, addiction and freedom, none of which can be reduced to rational fact and logical argument any more than the taste of orange juice can be reduced to a description of the effect of water, sugar and citric acid on the relevant cells of the body.

This is why many students who take philosophy degrees have the distinct feeling that they’ve got on the wrong train. They expect to be dealing with the towering mysteries of human existence, they expect to be studying the accounts of the immortals who went before us, who attempted to scale the same heights, they expect to be guided on this odyssey by interesting people who have made the same journey and returned with pristine insights into the path ahead. What they find instead is a cross between a librarian and an accountant piling up items of knowledge like coloured beads then handing them out to confused and bored young people who are expected to categorise them in, at best, a slightly different way to those who preceded them.

§22.