David Graeber & David Wengrow

The Dawn of Everything

A New History of Humanity

Foreword and Dedication (by David Wengrow)

1. Farewell to Humanity’s Childhood

WHY BOTH THE HOBBESIAN AND ROUSSEAUIAN VERSIONS OF HUMAN HISTORY HAVE DIRE POLITICAL IMPLICATIONS

HOW THE CONVENTIONAL NARRATIVE OF HUMAN HISTORY IS NOT ONLY WRONG, BUT QUITE NEEDLESSLY DULL

WHY THE ‘SAPIENT PARADOX’ IS A RED HERRING; AS SOON AS WE WERE HUMAN, WE STARTED DOING HUMAN THINGS

WHAT BEING SAPIENS REALLY MEANS

4. Free People, the Origin of Cultures, and the Advent of Private Property

IN WHICH WE ASK WHAT, PRECISELY, IS EQUALIZED IN ‘EGALITARIAN’ SOCIETIES?

IN WHICH WE FINALLY RETURN TO THE QUESTION OF PROPERTY, AND INQUIRE AS TO ITS RELATION TO THE SACRED

IN WHICH WE FIRST CONSIDER THE QUESTION OF CULTURAL DIFFERENTIATION

WHERE WE MAKE A CASE FOR SCHISMOGENESIS BETWEEN ‘PROTESTANT FORAGERS’ AND ‘FISHER KINGS’

CONCERNING THE NATURE OF SLAVERY AND ‘MODES OF PRODUCTION’ MORE GENERALLY

IN WHICH WE ASK: WOULD YOU RATHER FISH, OR GATHER ACORNS?

IN WHICH WE TURN TO THE CULTIVATION OF DIFFERENCE IN THE PACIFIC ‘SHATTER ZONE’

PLATONIC PREJUDICES, AND HOW THEY CLOUD OUR IDEAS ABOUT THE INVENTION OF FARMING

IN WHICH WE DISCUSS HOW ÇATALHÖYÜK, THE WORLD’S OLDEST TOWN, GOT A NEW HISTORY

HOW THE SEASONALITY OF SOCIAL LIFE IN EARLY FARMING COMMUNITIES MIGHT HAVE WORKED

ON BREAKING APART THE FERTILE CRESCENT

ON SLOW WHEAT, AND POP THEORIES OF HOW WE BECAME FARMERS

TO FARM OR NOT TO FARM: IT’S ALL IN YOUR HEAD (WHERE WE RETURN TO GÖBEKLI TEPE)

ON SEMANTIC SNARES AND METAPHYSICAL MIRAGES

WHY AGRICULTURE DID NOT DEVELOP SOONER

ON THE CASE OF AMAZONIA, AND THE POSSIBILITIES OF ‘PLAY FARMING’

BUT WHY DOES IT ALL MATTER? (A QUICK REPRISE ON THE DANGERS OF TELEOLOGICAL REASONING)

IN WHICH WE FIRST TAKE ON THE NOTORIOUS ISSUE OF ‘SCALE’

IN WHICH WE SET THE SCENE BROADLY FOR A WORLD OF CITIES, AND SPECULATE AS TO WHY THEY FIRST AROSE

ON MESOPOTAMIA, AND ‘NOT-SO-PRIMITIVE’ DEMOCRACY

IN WHICH WE CONSIDER WHETHER THE INDUS CIVILIZATION WAS AN EXAMPLE OF CASTE BEFORE KINGSHIP

CONCERNING AN APPARENT CASE OF ‘URBAN REVOLUTION’ IN CHINESE PREHISTORY

10. Why the State Has No Origin

ON AZTECS, INCA AND MAYA (AND THEN ALSO SPANIARDS)

ON POLITICS AS SPORT: THE OLMEC CASE

CHAVÍN DE HUÁNTAR – AN ‘EMPIRE’ BUILT ON IMAGES?

ON SOVEREIGNTY WITHOUT ‘THE STATE’

IN WHICH, ARMED WITH NEW KNOWLEDGE, WE RETHINK SOME BASIC PREMISES OF SOCIAL EVOLUTION

CODA: ON CIVILIZATION, EMPTY WALLS AND HISTORIES STILL TO BE WRITTEN

IN WHICH WE TELL THE STORY OF CAHOKIA, WHICH LOOKS LIKE IT OUGHT TO BE THE FIRST ‘STATE’ IN AMERICA

Front Matter

[About the Authors]

David Graeber was a professor of anthropology at the London School of Economics. He is the author of Debt: The First 5,000 Years and Bullshit Jobs: A Theory, and was a contributor to Harper’s Magazine, The Guardian, and The Baffler. An iconic thinker and renowned activist, his early efforts helped to make Occupy Wall Street an era-defining movement. He died on 2 September 2020.

David Wengrow is a professor of comparative archaeology at the Institute of Archaeology, University College London, and has been a visiting professor at New York University. He is the author of three books, including What Makes Civilization?. Wengrow conducts archaeological fieldwork in various parts of Africa and the Middle East.

[By The Same Authors]

David Graeber:

Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value: The False Coin of Our Own Dreams

Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology

Lost People: Magic and the Legacy of Slavery in Madagascar

Direct Action: An Ethnography

Debt: The First 5,000 Years

The Democracy Project: A History, a Crisis, a Movement

The Utopia of Rules: On Technology, Stupidity, and the Secret Joys of Bureaucracy

Bullshit Jobs: A Theory

David Wengrow:

The Archaeology of Early Egypt: Social Transformations in North-East Africa, 10,000 to 2650 BC

What Makes Civilization? The Ancient Near East and the Future of the West

The Origins of Monsters: Image and Cognition in the First Age of Mechanical Reproduction

List of Maps and Figures

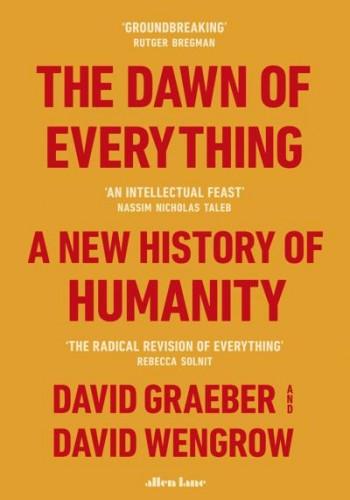

1. North America as defined by early-twentieth-century ethnologists (inset: the ethno-linguistic ‘shatter zone’ of Northern California)

(After C. D. Wissler (1913), ‘The North American Indians of the Plains’, Popular Science Monthly 82; A. L. Kroeber (1925), Handbook of the Indians of California. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 78. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.)

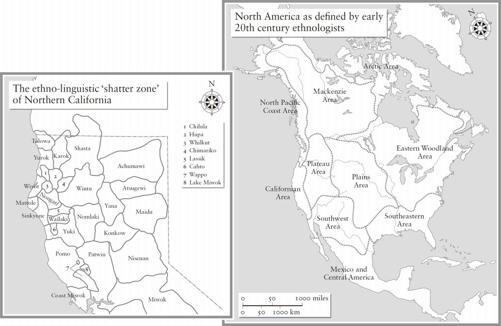

2. The Fertile Crescent of the Middle East – Neolithic farmers in a world of Mesolithic hunter-foragers, 8500–8000 BC

(Adapted from an original map by A. G. Sherratt, courtesy S. Sherratt.)

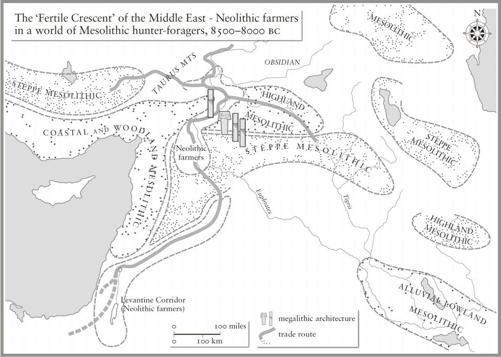

3. Independent centres of plant and animal domestication

(Adapted from an original map, courtesy D. Fuller.)

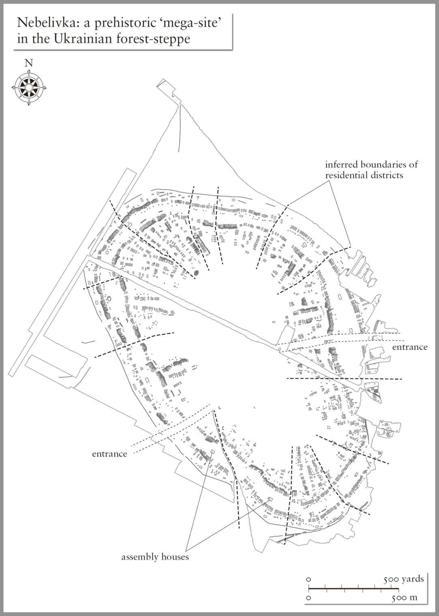

4. Nebelivka: a prehistoric ‘mega-site’ in the Ukrainian forest-steppe

(Based an original map drawn by Y. Beadnell on the basis of data from D. Hale; courtesy J. Chapman and B. Gaydarska.)

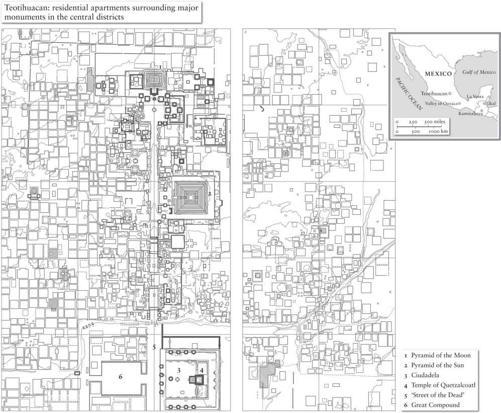

5. Teotihuacan: residential apartments surrounding major monuments in the central districts

(Adapted from R. Millon (1973), The Teotihuacán Map. Austin: University of Texas Press, courtesy the Teotihuacan Mapping Project and M. E. Smith.)

6. Some key archaeological sites in the Mississippi River basin and adjacent regions

(Adapted from an original map, courtesy T. R. Pauketat.)

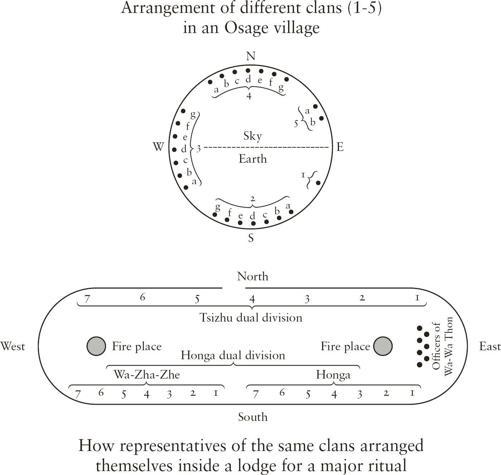

7. Above: arrangement of different clans (1–5) in an Osage village. Below: how representatives of the same clans arranged themselves inside a lodge for a major ritual.

(After A. C. Fletcher and F. La Flesche (1911), ‘The Omaha tribe’. Twenty-seventh Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1905–6. Washington D.C.: Bureau of American Ethnology; and F. La Flesche (1939), War Ceremony and Peace Ceremony of the Osage Indians. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 101. Washington: US Government.)

Foreword and Dedication (by David Wengrow)

David Rolfe Graeber died aged fifty-nine on 2 September 2020, just over three weeks after we finished writing this book, which had absorbed us for more than ten years. It began as a diversion from our more ‘serious’ academic duties: an experiment, a game almost, in which an anthropologist and an archaeologist tried to reconstruct the sort of grand dialogue about human history that was once quite common in our fields, but this time with modern evidence. There were no rules or deadlines. We wrote as and when we felt like it, which increasingly became a daily occurrence. In the final years before its completion, as the project gained momentum, it was not uncommon for us to talk two or three times a day. We would often lose track of who came up with what idea or which new set of facts and examples; it all went into ‘the archive’, which quickly outgrew the scope of a single book. The result is not a patchwork but a true synthesis. We could sense our styles of writing and thought converging by increments into what eventually became a single stream. Realizing we didn’t want to end the intellectual journey we’d embarked on, and that many of the concepts introduced in this book would benefit from further development and exemplification, we planned to write sequels: no less than three. But this first book had to finish somewhere, and at 9.18 p.m. on 6 August David Graeber announced, with characteristic Twitter-flair (and loosely citing Jim Morrison), that it was done: ‘My brain feels bruised with numb surprise.’ We got to the end just as we’d started, in dialogue, with drafts passing constantly back and forth between us as we read, shared and discussed the same sources, often into the small hours of the night. David was far more than an anthropologist. He was an activist and public intellectual of international repute who tried to live his ideas about social justice and liberation, giving hope to the oppressed and inspiring countless others to follow suit. The book is dedicated to the fond memory of David Graeber (1961–2020) and, as he wished, to the memory of his parents, Ruth Rubinstein Graeber (1917–2006) and Kenneth Graeber (1914–1996). May they rest together in peace.

Acknowledgements

Sad circumstances oblige me (David Wengrow) to write these acknowledgements in David Graeber’s absence. He is survived by his wife Nika. David’s passing was marked by an extraordinary outpouring of grief, which united people across continents, social classes and ideological boundaries. Ten years of writing and thinking together is a long time, and it is not for me to guess whom David would have wished to thank in this particular context. His co-travellers along the pathways that led to this book will already know who they are, and how much he treasured their support, care and advice. Of one thing I am certain: this book would not have happened – or at least not in anything remotely like its present form – without the inspiration and energy of Melissa Flashman, our wise counsel at all times in all things literary. In Eric Chinski of Farrar, Straus and Giroux and Thomas Penn of Penguin UK we found a superb editorial team and true intellectual partners. For their passionate engagements with and interventions in our thinking over many years, heartfelt thanks to Debbie Bookchin, Alpa Shah, Erhard Schüttpelz and Andrea Luka Zimmerman. For generous, expert guidance on different aspects of the book thanks to: Manuel Arroyo-Kalin, Elizabeth Baquedano, Nora Bateson, Stephen Berquist, Nurit Bird-David, Maurice Bloch, David Carballo, John Chapman, Luiz Costa, Philippe Descola, Aleksandr Diachenko, Kevan Edinborough, Dorian Fuller, Bisserka Gaydarska, Colin Grier, Thomas Grisaffi, Chris Hann, Wendy James, Megan Laws, Patricia McAnany, Barbara Alice Mann, Simon Martin, Jens Notroff, José R. Oliver, Mike Parker Pearson, Timothy Pauketat, Matthew Pope, Karen Radner, Natasha Reynolds, Marshall Sahlins, James C. Scott, Stephen Shennan and Michele Wollstonecroft.

A number of the arguments in this book were first presented as named lectures and in scholarly journals: an earlier version of Chapter Two appeared in French as ‘La sagesse de Kandiaronk: la critique indigène, le mythe du progrès et la naissance de la Gauche’ (La Revue du MAUSS); parts ofChapter Three were first presented as ‘Farewell to the childhood of man: ritual, seasonality, and the origins of inequality’ (The 2014 Henry Myers Lecture, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute); ofChapter Four as ‘Many seasons ago: slavery and its rejection among foragers on the Pacific Coast of North America’ (American Anthropologist); and of Chapter Eight as ‘Cities before the state in early Eurasia’ (The 2015 Jack Goody Lecture, Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology).

Thanks to the various academic institutions and research groups that welcomed us to speak and debate on topics relating to this book, and especially to Enzo Rossi and Philippe Descola for memorable occasions at the University of Amsterdam and the Collège de France. James Thomson (formerly editor-in-chief at Eurozine) first helped us get our ideas out into the wider world with the essay ‘How to change the course of human history (at least, the part that’s already happened)’, which he adopted with conviction when other publishing venues shied away; thanks also to the many translators who have extended its audience since; and to Kelly Burdick of Lapham’s Quarterly for inviting our contribution to a special issue on the theme of democracy, where we aired some of the ideas to be found here in Chapter Nine.

From the very beginning, both David and I incorporated our work on this book into our teaching, respectively at the LSE Department of Anthropology and the UCL Institute of Archaeology, so on behalf of both of us I wish to thank our students of the last ten years for their many insights and reflections. Martin, Judy, Abigail and Jack Wengrow were by my side every step of the way. My last and deepest thanks to Ewa Domaradzka for providing both the sharpest criticism and the most devoted support a partner could wish for; you came into my life, much as David and this book did: ‘Rain riding suddenly out of the air, Battering the bare walls of the sun … Rain, rain on dry ground!’

1. Farewell to Humanity’s Childhood

Or, why this is not a book about the origins of inequality

‘This mood makes itself felt everywhere, politically, socially, and philosophically. We are living in what the Greeks called the καιρóς (Kairos) – the right time – for a “metamorphosis of the gods,” i.e. of the fundamental principles and symbols.’

C. G. Jung, The Undiscovered Self (1958)

Most of human history is irreparably lost to us. Our species, Homo sapiens, has existed for at least 200,000 years, but for most of that time we have next to no idea what was happening. In northern Spain, for instance, at the cave of Altamira, paintings and engravings were created over a period of at least 10,000 years, between around 25,000 and 15,000 BC. Presumably, a lot of dramatic events occurred during this period. We have no way of knowing what most of them were.

This is of little consequence to most people, since most people rarely think about the broad sweep of human history anyway. They don’t have much reason to. Insofar as the question comes up at all, it’s usually when reflecting on why the world seems to be in such a mess and why human beings so often treat each other badly – the reasons for war, greed, exploitation, systematic indifference to others’ suffering. Were we always like that, or did something, at some point, go terribly wrong?

It is basically a theological debate. Essentially the question is: are humans innately good or innately evil? But if you think about it, the question, framed in these terms, makes very little sense. ‘Good’ and ‘evil’ are purely human concepts. It would never occur to anyone to argue about whether a fish, or a tree, were good or evil, because ‘good’ and ‘evil’ are concepts humans made up in order to compare ourselves with one another. It follows that arguing about whether humans are fundamentally good or evil makes about as much sense as arguing about whether humans are fundamentally fat or thin.

Nonetheless, on those occasions when people do reflect on the lessons of prehistory, they almost invariably come back to questions of this kind. We are all familiar with the Christian answer: people once lived in a state of innocence, yet were tainted by original sin. We desired to be godlike and have been punished for it; now we live in a fallen state while hoping for future redemption. Today, the popular version of this story is typically some updated variation on Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Discourse on the Origin and the Foundation of Inequality Among Mankind, which he wrote in 1754. Once upon a time, the story goes, we were hunter-gatherers, living in a prolonged state of childlike innocence, in tiny bands. These bands were egalitarian; they could be for the very reason that they were so small. It was only after the ‘Agricultural Revolution’, and then still more the rise of cities, that this happy condition came to an end, ushering in ‘civilization’ and ‘the state’ – which also meant the appearance of written literature, science and philosophy, but at the same time, almost everything bad in human life: patriarchy, standing armies, mass executions and annoying bureaucrats demanding that we spend much of our lives filling in forms.

Of course, this is a very crude simplification, but it really does seem to be the foundational story that rises to the surface whenever anyone, from industrial psychologists to revolutionary theorists, says something like ‘but of course human beings spent most of their evolutionary history living in groups of ten or twenty people,’ or ‘agriculture was perhaps humanity’s worst mistake.’ And as we’ll see, many popular writers make the argument quite explicitly. The problem is that anyone seeking an alternative to this rather depressing view of history will quickly find that the only one on offer is actually even worse: if not Rousseau, then Thomas Hobbes.

Hobbes’s Leviathan, published in 1651, is in many ways the founding text of modern political theory. It held that, humans being the selfish creatures they are, life in an original State of Nature was in no sense innocent; it must instead have been ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short’ – basically, a state of war, with everybody fighting against everybody else. Insofar as there has been any progress from this benighted state of affairs, a Hobbesian would argue, it has been largely due to exactly those repressive mechanisms that Rousseau was complaining about: governments, courts, bureaucracies, police. This view of things has been around for a very long time as well. There’s a reason why, in English, the words ‘politics’ ‘polite’ and ‘police’ all sound the same – they’re all derived from the Greek word polis, or city, the Latin equivalent of which is civitas, which also gives us ‘civility,’ ‘civic’ and a certain modern understanding of ‘civilization’.

Human society, in this view, is founded on the collective repression of our baser instincts, which becomes all the more necessary when humans are living in large numbers in the same place. The modern-day Hobbesian, then, would argue that, yes, we did live most of our evolutionary history in tiny bands, who could get along mainly because they shared a common interest in the survival of their offspring (‘parental investment’, as evolutionary biologists call it). But even these were in no sense founded on equality. There was always, in this version, some ‘alpha-male’ leader. Hierarchy and domination, and cynical self-interest, have always been the basis of human society. It’s just that, collectively, we have learned it’s to our advantage to prioritize our long-term interests over our short-term instincts; or, better, to create laws that force us to confine our worst impulses to socially useful areas like the economy, while forbidding them everywhere else.

As the reader can probably detect from our tone, we don’t much like the choice between these two alternatives. Our objections can be classified into three broad categories. As accounts of the general course of human history, they:

1. simply aren’t true;

2. have dire political implications;

3. make the past needlessly dull.

This book is an attempt to begin to tell another, more hopeful and more interesting story; one which, at the same time, takes better account of what the last few decades of research have taught us. Partly, this is a matter of bringing together evidence that has accumulated in archaeology, anthropology and kindred disciplines; evidence that points towards a completely new account of how human societies developed over roughly the last 30,000 years. Almost all of this research goes against the familiar narrative, but too often the most remarkable discoveries remain confined to the work of specialists, or have to be teased out by reading between the lines of scientific publications.

To give just a sense of how different the emerging picture is: it is clear now that human societies before the advent of farming were not confined to small, egalitarian bands. On the contrary, the world of hunter-gatherers as it existed before the coming of agriculture was one of bold social experiments, resembling a carnival parade of political forms, far more than it does the drab abstractions of evolutionary theory. Agriculture, in turn, did not mean the inception of private property, nor did it mark an irreversible step towards inequality. In fact, many of the first farming communities were relatively free of ranks and hierarchies. And far from setting class differences in stone, a surprising number of the world’s earliest cities were organized on robustly egalitarian lines, with no need for authoritarian rulers, ambitious warrior-politicians, or even bossy administrators.

Information bearing on such issues has been pouring in from every quarter of the globe. As a result, researchers around the world have also been examining ethnographic and historical material in a new light. The pieces now exist to create an entirely different world history – but so far, they remain hidden to all but a few privileged experts (and even the experts tend to hesitate before abandoning their own tiny part of the puzzle, to compare notes with others outside their specific subfield). Our aim in this book is to start putting some of the pieces of the puzzle together, in full awareness that nobody yet has anything like a complete set. The task is immense, and the issues so important, that it will take years of research and debate even to begin to understand the real implications of the picture we’re starting to see. But it’s crucial that we set the process in motion. One thing that will quickly become clear is that the prevalent ‘big picture’ of history – shared by modern-day followers of Hobbes and Rousseau alike – has almost nothing to do with the facts. But to begin making sense of the new information that’s now before our eyes, it is not enough to compile and sift vast quantities of data. A conceptual shift is also required.

To make that shift means retracing some of the initial steps that led to our modern notion of social evolution: the idea that human societies could be arranged according to stages of development, each with their own characteristic technologies and forms of organization (hunter-gatherers, farmers, urban-industrial society, and so on). As we will see, such notions have their roots in a conservative backlash against critiques of European civilization, which began to gain ground in the early decades of the eighteenth century. The origins of that critique, however, lie not with the philosophers of the Enlightenment (much though they initially admired and imitated it), but with indigenous commentators and observers of European society, such as the Native American (Huron-Wendat) statesman Kandiaronk, of whom we will learn much more in the next chapter.

Revisiting what we will call the ‘indigenous critique’ means taking seriously contributions to social thought that come from outside the European canon, and in particular from those indigenous peoples whom Western philosophers tend to cast either in the role of history’s angels or its devils. Both positions preclude any real possibility of intellectual exchange, or even dialogue: it’s just as hard to debate someone who is considered diabolical as someone considered divine, as almost anything they think or say is likely to be deemed either irrelevant or deeply profound. Most of the people we will be considering in this book are long since dead. It is no longer possible to have any sort of conversation with them. We are nonetheless determined to write prehistory as if it consisted of people one would have been able to talk to, when they were still alive – who don’t just exist as paragons, specimens, sock-puppets or playthings of some inexorable law of history.

There are, certainly, tendencies in history. Some are powerful; currents so strong that they are very difficult to swim against (though there always seem to be some who manage to do it anyway). But the only ‘laws’ are those we make up ourselves. Which brings us on to our second objection.

WHY BOTH THE HOBBESIAN AND ROUSSEAUIAN VERSIONS OF HUMAN HISTORY HAVE DIRE POLITICAL IMPLICATIONS

The political implications of the Hobbesian model need little elaboration. It is a foundational assumption of our economic system that humans are at base somewhat nasty and selfish creatures, basing their decisions on cynical, egoistic calculation rather than altruism or co-operation; in which case, the best we can hope for are more sophisticated internal and external controls on our supposedly innate drive towards accumulation and self-aggrandizement. Rousseau’s story about how humankind descended into inequality from an original state of egalitarian innocence seems more optimistic (at least there was somewhere better to fall from), but nowadays it’s mostly deployed to convince us that while the system we live under might be unjust, the most we can realistically aim for is a bit of modest tinkering. The term ‘inequality’ is itself very telling in this regard.

Since the financial crash of 2008, and the upheavals that followed, the question of inequality – and with it, the long-term history of inequality – have become major topics for debate. Something of a consensus has emerged among intellectuals and even, to some degree, the political classes that levels of social inequality have got out of hand, and that most of the world’s problems result, in one way or another, from an ever-widening gulf between the haves and the have-nots. Pointing this out is in itself a challenge to global power structures; at the same time, though, it frames the issue in a way that people who benefit from those structures can still find ultimately reassuring, since it implies no meaningful solution to the problem would ever be possible.

After all, imagine we framed the problem differently, the way it might have been fifty or 100 years ago: as the concentration of capital, or oligopoly, or class power. Compared to any of these, a word like ‘inequality’ sounds like it’s practically designed to encourage half-measures and compromise. It’s possible to imagine overthrowing capitalism or breaking the power of the state, but it’s not clear what eliminating inequality would even mean. (Which kind of inequality? Wealth? Opportunity? Exactly how equal would people have to be in order for us to be able to say we’ve ‘eliminated inequality’?) The term ‘inequality’ is a way of framing social problems appropriate to an age of technocratic reformers, who assume from the outset that no real vision of social transformation is even on the table.

Debating inequality allows one to tinker with the numbers, argue about Gini coefficients and thresholds of dysfunction, readjust tax regimes or social welfare mechanisms, even shock the public with figures showing just how bad things have become (‘Can you imagine? The richest 1 per cent of the world’s population own 44 per cent of the world’s wealth!’) – but it also allows one to do all this without addressing any of the factors that people actually object to about such ‘unequal’ social arrangements: for instance, that some manage to turn their wealth into power over others; or that other people end up being told their needs are not important, and their lives have no intrinsic worth. The last, we are supposed to believe, is just the inevitable effect of inequality; and inequality, the inevitable result of living in any large, complex, urban, technologically sophisticated society. Presumably it will always be with us. It’s just a matter of degree.

Today, there is a veritable boom of thinking about inequality: since 2011, ‘global inequality’ has regularly featured as a top item for debate in the World Economic Forum at Davos. There are inequality indexes, institutes for the study of inequality, and a relentless stream of publications trying to project the current obsession with property distribution back into the Stone Age. There have even been attempts to calculate income levels and Gini coefficients for Palaeolithic mammoth hunters (they both turn out to be very low).[1] It’s almost as if we feel some need to come up with mathematical formulae justifying the expression, already popular in the days of Rousseau, that in such societies ‘everyone was equal, because they were all equally poor.’

The ultimate effect of all these stories about an original state of innocence and equality, like the use of the term ‘inequality’ itself, is to make wistful pessimism about the human condition seem like common sense: the natural result of viewing ourselves through history’s broad lens. Yes, living in a truly egalitarian society might be possible if you’re a Pygmy or a Kalahari Bushman. But if you want to create a society of true equality today, you’re going to have to figure out a way to go back to becoming tiny bands of foragers again with no significant personal property. Since foragers require a pretty extensive territory to forage in, this would mean having to reduce the world’s population by something like 99.9 per cent. Otherwise, the best we can hope for is to adjust the size of the boot that will forever be stomping on our faces; or, perhaps, to wangle a bit more wiggle room in which some of us can temporarily duck out of its way.

A first step towards a more accurate, and hopeful, picture of world history might be to abandon the Garden of Eden once and for all, and simply do away with the notion that for hundreds of thousands of years, everyone on earth shared the same idyllic form of social organization. Strangely enough, though, this is often seen as a reactionary move. ‘So are you saying true equality has never been achieved? That it’s therefore impossible?’ It seems to us that such objections are both counterproductive and frankly unrealistic.

First of all, it’s bizarre to imagine that, say, during the roughly 10,000 (some would say more like 20,000) years in which people painted on the walls of Altamira, no one – not only in Altamira, but anywhere on earth – experimented with alternative forms of social organization. What’s the chance of that? Second of all, is not the capacity to experiment with different forms of social organization itself a quintessential part of what makes us human? That is, beings with the capacity for self-creation, even freedom? The ultimate question of human history, as we’ll see, is not our equal access to material resources (land, calories, means of production), much though these things are obviously important, but our equal capacity to contribute to decisions about how to live together. Of course, to exercise that capacity implies that there should be something meaningful to decide in the first place.

If, as many are suggesting, our species’ future now hinges on our capacity to create something different (say, a system in which wealth cannot be freely transformed into power, or where some people are not told their needs are unimportant, or that their lives have no intrinsic worth), then what ultimately matters is whether we can rediscover the freedoms that make us human in the first place. As long ago as 1936, the prehistorian V. Gordon Childe wrote a book called Man Makes Himself. Apart from the sexist language, this is the spirit we wish to invoke. We are projects of collective self-creation. What if we approached human history that way? What if we treat people, from the beginning, as imaginative, intelligent, playful creatures who deserve to be understood as such? What if, instead of telling a story about how our species fell from some idyllic state of equality, we ask how we came to be trapped in such tight conceptual shackles that we can no longer even imagine the possibility of reinventing ourselves?

SOME BRIEF EXAMPLES OF WHY RECEIVED UNDERSTANDINGS OF THE BROAD SWEEP OF HUMAN HISTORY ARE MOSTLY WRONG (OR, THE ETERNAL RETURN OF JEAN-JACQUES ROUSSEAU)

When we first embarked on this book, our intention was to seek new answers to questions about the origins of social inequality. It didn’t take long before we realized this simply wasn’t a very good approach. Framing human history in this way – which necessarily means assuming humanity once existed in an idyllic state, and that a specific point can be identified at which everything started to go wrong – made it almost impossible to ask any of the questions we felt were genuinely interesting. It felt like almost everyone else seemed to be caught in the same trap. Specialists were refusing to generalize. Those few willing to stick their necks out almost invariably reproduced some variation on Rousseau.

Let’s consider a fairly random example of one of these generalist accounts, Francis Fukuyama’s The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution (2011). Here is Fukuyama on what he feels can be taken as received wisdom about early human societies: ‘In its early stages human political organization is similar to the band-level society observed in higher primates like chimpanzees,’ which Fukuyama suggests can be regarded as ‘a default form of social organization’. He then goes on to assert that Rousseau was largely correct in pointing out that the origin of political inequality lay in the development of agriculture, since hunter-gatherer societies (according to Fukuyama) have no concept of private property, and so little incentive to mark out a piece of land and say, ‘This is mine.’ Band-level societies of this sort, he suggests, are ‘highly egalitarian’.[2]

Jared Diamond, in The World Until Yesterday: What Can We Learn from Traditional Societies? (2012) suggests that such bands (in which he believes humans still lived ‘as recently as 11,000 years ago’) comprised ‘just a few dozen individuals’, most biologically related. These small groups led a fairly meagre existence, ‘hunting and gathering whatever wild animal and plant species happen to live in an acre of forest’. And their social lives, according to Diamond, were enviably simple. Decisions were reached through ‘face-to-face discussion’; there were ‘few personal possessions’ and ‘no formal political leadership or strong economic specialization’.[3] Diamond concludes that, sadly, it is only within such primordial groupings that humans ever achieved a significant degree of social equality.

For Diamond and Fukuyama, as for Rousseau some centuries earlier, what put an end to that equality – everywhere and forever – was the invention of agriculture, and the higher population levels it sustained. Agriculture brought about a transition from ‘bands’ to ‘tribes’. Accumulation of food surplus fed population growth, leading some ‘tribes’ to develop into ranked societies known as ‘chiefdoms’. Fukuyama paints an almost explicitly biblical picture of this process, a departure from Eden: ‘As little bands of human beings migrated and adapted to different environments, they began their exit out of the state of nature by developing new social institutions.’[4] They fought wars over resources. Gangly and pubescent, these societies were clearly heading for trouble.

It was time to grow up and appoint some proper leadership. Hierarchies began to emerge. There was no point in resisting, since hierarchy – according to Diamond and Fukuyama – is inevitable once humans adopt large, complex forms of organization. Even when the new leaders began acting badly – creaming off agricultural surplus to promote their flunkies and relatives, making status permanent and hereditary, collecting trophy skulls and harems of slave-girls, or tearing out rivals’ hearts with obsidian knives – there could be no going back. Before long, chiefs had managed to convince others they should be referred to as ‘kings’, even ‘emperors’. As Diamond patiently explains to us:

Large populations can’t function without leaders who make the decisions, executives who carry out the decisions, and bureaucrats who administer the decisions and laws. Alas for all of you readers who are anarchists and dream of living without any state government, those are the reasons why your dream is unrealistic: you’ll have to find some tiny band or tribe willing to accept you, where no one is a stranger, and where kings, presidents, and bureaucrats are unnecessary.[5]

A dismal conclusion, not just for anarchists but for anybody who ever wondered if there might be a viable alternative to the current status quo. Still, the truly remarkable thing is that, despite the self-assured tone, such pronouncements are not actually based on any kind of scientific evidence. As we will soon be discovering, there is simply no reason to believe that small-scale groups are especially likely to be egalitarian – or, conversely, that large ones must necessarily have kings, presidents or even bureaucracies. Statements like these are just so many prejudices dressed up as facts, or even as laws of history.[6]

ON THE PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS

As we say, it’s all just an endless repetition of a story first told by Rousseau in 1754. Many contemporary scholars will quite literally say that Rousseau’s vision has been proved correct. If so, it is an extraordinary coincidence, since Rousseau himself never suggested that the innocent State of Nature really happened. On the contrary, he insisted he was engaging in a thought experiment: ‘One must not take the kind of research which we enter into as the pursuit of truths of history, but solely as hypothetical and conditional reasonings, better fitted to clarify the nature of things than to expose their actual origin …’[7]

Rousseau’s portrayal of the State of Nature and how it was overturned by the coming of agriculture was never intended to form the basis for a series of evolutionary stages, like the ones Scottish philosophers such as Smith, Ferguson or Millar (and later on, Lewis Henry Morgan) were referring to when they spoke of ‘Savagery’ and ‘Barbarism’. In no sense was Rousseau imagining these different states of being as levels of social and moral development, corresponding to historical changes in modes of production: foraging, pastoralism, farming, industry. Rather, what Rousseau presented was more of a parable, by way of an attempt to explore a fundamental paradox of human politics: how is it that our innate drive for freedom somehow leads us, time and again, on a ‘spontaneous march to inequality’?[8]

Describing how the invention of farming first leads to private property, and property to the need for civil government to protect it, this is how Rousseau puts things: ‘All ran towards their chains, believing that they were securing their liberty; for although they had reason enough to discern the advantages of a civil order, they did not have experience enough to foresee the dangers.’[9] His imaginary State of Nature was primarily invoked as a way of illustrating the point. True, he didn’t invent the concept: as a rhetorical device, the State of Nature had already been used in European philosophy for a century. Widely deployed by natural law theorists, it effectively allowed every thinker interested in the origins of government (Locke, Grotius and so on) to play God, each coming up with his own variant on humanity’s original condition, as a springboard for speculation.

Hobbes was doing much the same thing when he wrote in Leviathan that the primordial state of human society would necessarily have been a ‘Bellum omnium contra omnes’, a war of all against all, which could only be overcome by the creation of an absolute sovereign power. He wasn’t saying there had actually been a time when everyone lived in such a primordial state. Some suspect that Hobbes’s state of war was really an allegory for his native England’s descent into civil war in the mid seventeenth century, which drove the royalist author into exile in Paris. Whatever the case, the closest Hobbes himself came to suggesting this state really existed was when he noted how the only people who weren’t under the ultimate authority of some king were the kings themselves, and they always seemed to be at war with one another.

Despite all this, many modern writers treat Leviathan in the same way others treat Rousseau’s Discourse – as if it were laying the groundwork for an evolutionary study of history; and although the two have completely different starting points, the result is rather similar.[10]

‘When it came to violence in pre-state peoples,’ writes the psychologist Steven Pinker, ‘Hobbes and Rousseau were talking through their hats: neither knew a thing about life before civilization.’ On this point, Pinker is absolutely right. In the same breath, however, he also asks us to believe that Hobbes, writing in 1651 (apparently through his hat), somehow managed to guess right, and come up with an analysis of violence and its causes in human history that is ‘as good as any today’.[11] This would be an astonishing – not to mention damning – verdict on centuries of empirical research, if it only happened to be true. As we’ll see, it is not even close.[12]

We can take Pinker as our quintessential modern Hobbesian. In his magnum opus, The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (2012), and subsequent books like Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress (2018) he argues that today we live in a world which is, overall, far less violent and cruel than anything our ancestors had ever experienced.[13]

Now, this may seem counter-intuitive to anyone who spends much time watching the news, let alone who knows much about the history of the twentieth century. Pinker, though, is confident that an objective statistical analysis, shorn of sentiment, will show us to be living in an age of unprecedented peace and security. And this, he suggests, is the logical outcome of living in sovereign states, each with a monopoly over the legitimate use of violence within its borders, as opposed to the ‘anarchic societies’ (as he calls them) of our deep evolutionary past, where life for most people was, indeed, typically ‘nasty, brutish, and short’.

Since, like Hobbes, Pinker is concerned with the origins of the state, his key point of transition is not the rise of farming but the emergence of cities. ‘Archaeologists’, he writes, ‘tell us that humans lived in a state of anarchy until the emergence of civilization some five thousand years ago, when sedentary farmers first coalesced into cities and states and developed the first governments.’[14] What follows is, to put it bluntly, a modern psychologist making it up as he goes along. You might hope that a passionate advocate of science would approach the topic scientifically, through a broad appraisal of the evidence – but this is precisely the approach to human prehistory that Pinker seems to find uninteresting. Instead he relies on anecdotes, images and individual sensational discoveries, like the headline-making find, in 1991, of ‘Ötzi the Tyrolean Iceman’.

‘What is it about the ancients,’ Pinker asks at one point, ‘that they couldn’t leave us an interesting corpse without resorting to foul play?’ There is an obvious response to this: doesn’t it rather depend on which corpse you consider interesting in the first place? Yes, a little over 5,000 years ago someone walking through the Alps left the world of the living with an arrow in his side; but there’s no particular reason to treat Ötzi as a poster child for humanity in its original condition, other than, perhaps, Ötzi suiting Pinker’s argument. But if all we’re doing is cherry-picking, we could just as easily have chosen the much earlier burial known to archaeologists as Romito 2 (after the Calabrian rock-shelter where it was found). Let’s take a moment to consider what it would mean if we did this.

Romito 2 is the 10,000-year-old burial of a male with a rare genetic disorder (acromesomelic dysplasia): a severe type of dwarfism, which in life would have rendered him both anomalous in his community and unable to participate in the kind of high-altitude hunting that was necessary for their survival. Studies of his pathology show that, despite generally poor levels of health and nutrition, that same community of hunter-gatherers still took pains to support this individual through infancy and into early adulthood, granting him the same share of meat as everyone else, and ultimately according him a careful, sheltered burial.[15]

Neither is Romito 2 an isolated case. When archaeologists undertake balanced appraisals of hunter-gatherer burials from the Palaeolithic, they find high frequencies of health-related disabilities – but also surprisingly high levels of care until the time of death (and beyond, since some of these funerals were remarkably lavish).[16] If we did want to reach a general conclusion about what form human societies originally took, based on statistical frequencies of health indicators from ancient burials, we would have to reach the exact opposite conclusion to Hobbes (and Pinker): in origin, it might be claimed, our species is a nurturing and care-giving species, and there was simply no need for life to be nasty, brutish or short.

We’re not suggesting we actually do this. As we’ll see, there is reason to believe that during the Palaeolithic, only rather unusual individuals were buried at all. We just want to point out how easy it would be to play the same game in the other direction – easy, but frankly not too enlightening.[17] As we get to grips with the actual evidence, we always find that the realities of early human social life were far more complex, and a good deal more interesting, than any modern-day State of Nature theorist would ever be likely to guess.

When it comes to cherry-picking anthropological case studies, and putting them forward as representative of our ‘contemporary ancestors’ – that is, as models for what humans might have been like in a State of Nature – those working in the tradition of Rousseau tend to prefer African foragers like the Hadza, Pygmies or !Kung. Those who follow Hobbes prefer the Yanomami.

The Yanomami are an indigenous population who live largely by growing plantains and cassava in the Amazon rainforest, their traditional homeland, on the border of southern Venezuela and northern Brazil. Since the 1970s, the Yanomami have acquired a reputation as the quintessential violent savages: ‘fierce people’, as their most famous ethnographer, Napoleon Chagnon, called them. This seems decidedly unfair to the Yanomami since, in fact, statistics show they’re not particularly violent – compared with other Amerindian groups, Yanomami homicide rates turn out average-to-low.[18] Again, though, actual statistics turn out to matter less than the availability of dramatic images and anecdotes. The real reason the Yanomami are so famous, and have such a colourful reputation, has everything to do with Chagnon himself: his 1968 book Yanomamö: The Fierce People, which sold millions of copies, and also a series of films, such as The Ax Fight, which offered viewers a vivid glimpse of tribal warfare. For a while all this made Chagnon the world’s most famous anthropologist, in the process turning the Yanomami into a notorious case study of primitive violence and establishing their scientific importance in the emerging field of sociobiology.

We should be fair to Chagnon (not everyone is). He never claimed the Yanomami should be treated as living remnants of the Stone Age; indeed, he often noted that they obviously weren’t. At the same time, and somewhat unusually for an anthropologist, he tended to define them primarily in terms of things they lacked (e.g. written language, a police force, a formal judiciary), as opposed to the positive features of their culture, which has rather the same effect of setting them up as quintessential primitives.[19] Chagnon’s central argument was that adult Yanomami men achieve both cultural and reproductive advantages by killing other adult men; and that this feedback between violence and biological fitness – if generally representative of the early human condition – might have had evolutionary consequences for our species as a whole.[20]

This is not just a big ‘if’ – it’s enormous. Other anthropologists started raining down questions, not always friendly.[21] Allegations of professional misconduct were levelled at Chagnon (mostly revolving around ethical standards in the field), and everyone took sides. Some of these accusations appear baseless, but the rhetoric of Chagnon’s defenders grew so heated that (as another celebrated anthropologist, Clifford Geertz, put it) not only was he held up as the epitome of rigorous, scientific anthropology, but all who questioned him or his social Darwinism were excoriated as ‘Marxists’, ‘liars’, ‘cultural anthropologists from the academic left’, ‘ayatollahs’ and ‘politically correct bleeding hearts’. To this day, there is no easier way to get anthropologists to begin denouncing each other as extremists than to mention the name of Napoleon Chagnon.[22]

The important point here is that, as a ‘non-state’ people, the Yanomami are supposed to exemplify what Pinker calls the ‘Hobbesian trap’, whereby individuals in tribal societies find themselves caught in repetitive cycles of raiding and warfare, living fraught and precarious lives, always just a few steps away from violent death on the tip of a sharp weapon or at the end of a vengeful club. That, Pinker tells us, is the kind of dismal fate ordained for us by evolution. We have only escaped it by virtue of our willingness to place ourselves under the common protection of nation states, courts of law and police forces; and also by embracing virtues of reasoned debate and self-control that Pinker sees as the exclusive heritage of a European ‘civilizing process’, which produced the Age of Enlightenment (in other words, were it not for Voltaire, and the police, the knife-fight over Chagnon’s findings would have been physical, not just academic).

There are many problems with this argument. We’ll start with the most obvious. The idea that our current ideals of freedom, equality and democracy are somehow products of the ‘Western tradition’ would in fact have come as an enormous surprise to someone like Voltaire. As we’ll soon see, the Enlightenment thinkers who propounded such ideals almost invariably put them in the mouths of foreigners, even ‘savages’ like the Yanomami. This is hardly surprising, since it’s almost impossible to find a single author in that Western tradition, from Plato to Marcus Aurelius to Erasmus, who did not make it clear that they would have been opposed to such ideas. The word ‘democracy’ might have been invented in Europe (barely, since Greece at the time was much closer culturally to North Africa and the Middle East than it was to, say, England), but it’s almost impossible to find a single European author before the nineteenth century who suggested it would be anything other than a terrible form of government.[23]

For obvious reasons, Hobbes’s position tends to be favoured by those on the right of the political spectrum, and Rousseau’s by those leaning left. Pinker positions himself as a rational centrist, condemning what he considers to be the extremists on either side. But why then insist that all significant forms of human progress before the twentieth century can be attributed only to that one group of humans who used to refer to themselves as ‘the white race’ (and now, generally, call themselves by its more accepted synonym, ‘Western civilization’)? There is simply no reason to make this move. It would be just as easy (actually, rather easier) to identify things that can be interpreted as the first stirrings of rationalism, legality, deliberative democracy and so forth all over the world, and only then tell the story of how they coalesced into the current global system.[24]

Insisting, to the contrary, that all good things come only from Europe ensures one’s work can be read as a retroactive apology for genocide, since (apparently, for Pinker) the enslavement, rape, mass murder and destruction of whole civilizations – visited on the rest of the world by European powers – is just another example of humans comporting themselves as they always had; it was in no sense unusual. What was really significant, so this argument goes, is that it made possible the dissemination of what he takes to be ‘purely’ European notions of freedom, equality before the law, and human rights to the survivors.

Whatever the unpleasantness of the past, Pinker assures us, there is every reason to be optimistic, indeed happy, about the overall path our species has taken. True, he does concede there is scope for some serious tinkering in areas like poverty reduction, income inequality or indeed peace and security; but on balance – and relative to the number of people living on earth today – what we have now is a spectacular improvement on anything our species accomplished in its history so far (unless you’re Black, or live in Syria, for example). Modern life is, for Pinker, in almost every way superior to what came before; and here he does produce elaborate statistics which purport to show how every day in every way – health, security, education, comfort, and by almost any other conceivable parameter – everything is actually getting better and better.

It’s hard to argue with the numbers, but as any statistician will tell you, statistics are only as good as the premises on which they are based. Has ‘Western civilization’ really made life better for everyone? This ultimately comes down to the question of how to measure human happiness, which is a notoriously difficult thing to do. About the only dependable way anyone has ever discovered to determine whether one way of living is really more satisfying, fulfilling, happy or otherwise preferable to any other is to allow people to fully experience both, give them a choice, then watch what they actually do. For instance, if Pinker is correct, then any sane person who had to choose between (a) the violent chaos and abject poverty of the ‘tribal’ stage in human development and (b) the relative security and prosperity of Western civilization would not hesitate to leap for safety.[25]

But empirical data is available here, and it suggests something is very wrong with Pinker’s conclusions.

Over the last several centuries, there have been numerous occasions when individuals found themselves in a position to make precisely this choice – and they almost never go the way Pinker would have predicted. Some have left us clear, rational explanations for why they made the choices they did. Let us consider the case of Helena Valero, a Brazilian woman born into a family of Spanish descent, whom Pinker mentions as a ‘white girl’ abducted by Yanomami in 1932 while travelling with her parents along the remote Rio Dimití.

For two decades, Valero lived with a series of Yanomami families, marrying twice, and eventually achieving a position of some importance in her community. Pinker briefly cites the account Valero later gave of her own life, where she describes the brutality of a Yanomami raid.[26] What he neglects to mention is that in 1956 she abandoned the Yanomami to seek her natal family and live again in ‘Western civilization,’ only to find herself in a state of occasional hunger and constant dejection and loneliness. After a while, given the ability to make a fully informed decision, Helena Valero decided she preferred life among the Yanomami, and returned to live with them.[27]

Her story is by no means unusual. The colonial history of North and South America is full of accounts of settlers, captured or adopted by indigenous societies, being given the choice of where they wished to stay and almost invariably choosing to stay with the latter.[28] This even applied to abducted children. Confronted again with their biological parents, most would run back to their adoptive kin for protection.[29] By contrast, Amerindians incorporated into European society by adoption or marriage, including those who – unlike the unfortunate Helena Valero – enjoyed considerable wealth and schooling, almost invariably did just the opposite: either escaping at the earliest opportunity, or – having tried their best to adjust, and ultimately failed – returning to indigenous society to live out their last days.

Among the most eloquent commentaries on this whole phenomenon is to be found in a private letter written by Benjamin Franklin to a friend:

When an Indian Child has been brought up among us, taught our language and habituated to our Customs, yet if he goes to see his relations and make one Indian Ramble with them there is no persuading him ever to return, and that this is not natural merely as Indians, but as men, is plain from this, that when white persons of either sex have been taken prisoner young by the Indians, and lived awhile among them, tho’ ransomed by their Friends, and treated with all imaginable tenderness to prevail with them to stay among the English, yet in a Short time they become disgusted with our manner of life, and the care and pains that are necessary to support it, and take the first opportunity of escaping again into the Woods, from whence there is no reclaiming them. One instance I remember to have heard, where the person was to be brought home to possess a good Estate; but finding some care necessary to keep it together, he relinquished it to a younger brother, reserving to himself nothing but a gun and match-Coat, with which he took his way again to the Wilderness.[30]

Many who found themselves embroiled in such contests of civilization, if we may call them that, were able to offer clear reasons for their decisions to stay with their erstwhile captors. Some emphasized the virtues of freedom they found in Native American societies, including sexual freedom, but also freedom from the expectation of constant toil in pursuit of land and wealth.[31] Others noted the ‘Indian’s’ reluctance ever to let anyone fall into a condition of poverty, hunger or destitution. It was not so much that they feared poverty themselves, but rather that they found life infinitely more pleasant in a society where no one else was in a position of abject misery (perhaps much as Oscar Wilde declared he was an advocate of socialism because he didn’t like having to look at poor people or listen to their stories). For anyone who has grown up in a city full of rough sleepers and panhandlers – and that is, unfortunately, most of us – it is always a bit startling to discover there’s nothing inevitable about any of this.

Still others noted the ease with which outsiders, taken in by ‘Indian’ families, might achieve acceptance and prominent positions in their adoptive communities, becoming members of chiefly households, or even chiefs themselves.[32] Western propagandists speak endlessly about equality of opportunity; these seem to have been societies where it actually existed. By far the most common reasons, however, had to do with the intensity of social bonds they experienced in Native American communities: qualities of mutual care, love and above all happiness, which they found impossible to replicate once back in European settings. ‘Security’ takes many forms. There is the security of knowing one has a statistically smaller chance of getting shot with an arrow. And then there’s the security of knowing that there are people in the world who will care deeply if one is.

HOW THE CONVENTIONAL NARRATIVE OF HUMAN HISTORY IS NOT ONLY WRONG, BUT QUITE NEEDLESSLY DULL

One gets the sense that indigenous life was, to put it very crudely, just a lot more interesting than life in a ‘Western’ town or city, especially insofar as the latter involved long hours of monotonous, repetitive, conceptually empty activity. The fact that we find it hard to imagine how such an alternative life could be endlessly engaging and interesting is perhaps more a reflection on the limits of our imagination than on the life itself.

One of the most pernicious aspects of standard world-historical narratives is precisely that they dry everything up, reduce people to cardboard stereotypes, simplify the issues (are we inherently selfish and violent, or innately kind and co-operative?) in ways that themselves undermine, possibly even destroy, our sense of human possibility. ‘Noble’ savages are, ultimately, just as boring as savage ones; more to the point, neither actually exist. Helena Valero was herself adamant on this point. The Yanomami were not devils, she insisted, neither were they angels. They were human, like the rest of us.

Now, we should be clear here: social theory always, necessarily, involves a bit of simplification. For instance, almost any human action might be said to have a political aspect, an economic aspect, a psycho-sexual aspect and so forth. Social theory is largely a game of make-believe in which we pretend, just for the sake of argument, that there’s just one thing going on: essentially, we reduce everything to a cartoon so as to be able to detect patterns that would be otherwise invisible. As a result, all real progress in social science has been rooted in the courage to say things that are, in the final analysis, slightly ridiculous: the work of Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud or Claude Lévi-Strauss being only particularly salient cases in point. One must simplify the world to discover something new about it. The problem comes when, long after the discovery has been made, people continue to simplify.

Hobbes and Rousseau told their contemporaries things that were startling, profound and opened new doors of the imagination. Now their ideas are just tired common sense. There’s nothing in them that justifies the continued simplification of human affairs. If social scientists today continue to reduce past generations to simplistic, two-dimensional caricatures, it is not so much to show us anything original, but just because they feel that’s what social scientists are expected to do so as to appear ‘scientific’. The actual result is to impoverish history – and as a consequence, to impoverish our sense of possibility. Let us end this introduction with an illustration, before moving on to the heart of the matter.

Ever since Adam Smith, those trying to prove that contemporary forms of competitive market exchange are rooted in human nature have pointed to the existence of what they call ‘primitive trade’. Already tens of thousands of years ago, one can find evidence of objects – very often precious stones, shells or other items of adornment – being moved around over enormous distances. Often these were just the sort of objects that anthropologists would later find being used as ‘primitive currencies’ all over the world. Surely this must prove capitalism in some form or another has always existed?

The logic is perfectly circular. If precious objects were moving long distances, this is evidence of ‘trade’ and, if trade occurred, it must have taken some sort of commercial form; therefore, the fact that, say, 3,000 years ago Baltic amber found its way to the Mediterranean, or shells from the Gulf of Mexico were transported to Ohio, is proof that we are in the presence of some embryonic form of market economy. Markets are universal. Therefore, there must have been a market. Therefore, markets are universal. And so on.

All such authors are really saying is that they themselves cannot personally imagine any other way that precious objects might move about. But lack of imagination is not itself an argument. It’s almost as if these writers are afraid to suggest anything that seems original, or, if they do, feel obliged to use vaguely scientific-sounding language (‘trans-regional interaction spheres’, ‘multi-scalar networks of exchange’) to avoid having to speculate about what precisely those things might be. In fact, anthropology provides endless illustrations of how valuable objects might travel long distances in the absence of anything that remotely resembles a market economy.

The founding text of twentieth-century ethnography, Bronisław Malinowski’s 1922 Argonauts of the Western Pacific, describes how in the ‘kula chain’ of the Massim Islands off Papua New Guinea, men would undertake daring expeditions across dangerous seas in outrigger canoes, just in order to exchange precious heirloom arm-shells and necklaces for each other (each of the most important ones has its own name, and history of former owners) – only to hold it briefly, then pass it on again to a different expedition from another island. Heirloom treasures circle the island chain eternally, crossing hundreds of miles of ocean, arm-shells and necklaces in opposite directions. To an outsider, it seems senseless. To the men of the Massim it was the ultimate adventure, and nothing could be more important than to spread one’s name, in this fashion, to places one had never seen.

Is this ‘trade’? Perhaps, but it would bend to breaking point our ordinary understandings of what that word means. There is, in fact, a substantial ethnographic literature on how such long-distance exchange operates in societies without markets. Barter does occur: different groups may take on specialities – one is famous for its feather-work, another provides salt, in a third all women are potters – to acquire things they cannot produce themselves; sometimes one group will specialize in the very business of moving people and things around. But we often find such regional networks developing largely for the sake of creating friendly mutual relations, or having an excuse to visit one another from time to time;[33] and there are plenty of other possibilities that in no way resemble ‘trade’.

Let’s list just a few, all drawn from North American material, to give the reader a taste of what might really be going on when people speak of ‘long-distance interaction spheres’ in the human past:

1. Dreams or vision quests: among Iroquoian-speaking peoples in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries it was considered extremely important literally to realize one’s dreams. Many European observers marvelled at how Indians would be willing to travel for days to bring back some object, trophy, crystal or even an animal like a dog that they had dreamed of acquiring. Anyone who dreamed about a neighbour or relative’s possession (a kettle, ornament, mask and so on) could normally demand it; as a result, such objects would often gradually travel some way from town to town. On the Great Plains, decisions to travel long distances in search of rare or exotic items could form part of vision quests.[34]

2. Travelling healers and entertainers: in 1528, when a shipwrecked Spaniard named Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca made his way from Florida across what is now Texas to Mexico, he found he could pass easily between villages (even villages at war with one another) by offering his services as a magician and curer. Curers in much of North America were also entertainers, and would often develop significant entourages; those who felt their lives had been saved by the performance would, typically, offer up all their material possessions to be divided among the troupe.[35] By such means, precious objects could easily travel very long distances.

3. Women’s gambling: women in many indigenous North American societies were inveterate gamblers; the women of adjacent villages would often meet to play dice or a game played with a bowl and plum stone, and would typically bet their shell beads or other objects of personal adornment as the stakes. One archaeologist versed in the ethnographic literature, Warren DeBoer, estimates that many of the shells and other exotica discovered in sites halfway across the continent had got there by being endlessly wagered, and lost, in inter-village games of this sort, over very long periods of time.[36]

We could multiply examples, but assume that by now the reader gets the broader point we are making. When we simply guess as to what humans in other times and places might be up to, we almost invariably make guesses that are far less interesting, far less quirky – in a word, far less human than what was likely going on.

ON WHAT’S TO FOLLOW

In this book we will not only be presenting a new history of humankind, but inviting the reader into a new science of history, one that restores our ancestors to their full humanity. Rather than asking how we ended up unequal, we will start by asking how it was that ‘inequality’ became such an issue to begin with, then gradually build up an alternative narrative that corresponds more closely to our current state of knowledge. If humans did not spend 95 per cent of their evolutionary past in tiny bands of hunter-gatherers, what were they doing all that time? If agriculture, and cities, did not mean a plunge into hierarchy and domination, then what did they imply? What was really happening in those periods we usually see as marking the emergence of ‘the state’? The answers are often unexpected, and suggest that the course of human history may be less set in stone, and more full of playful possibilities, than we tend to assume.

In one sense, then, this book is simply trying to lay down foundations for a new world history, rather as Gordon Childe did when, back in the 1930s, he invented phrases like ‘the Neolithic Revolution’ or ‘the Urban Revolution’. As such it is necessarily uneven and incomplete. At the same time, this book is also something else: a quest to discover the right questions. If ‘what is the origin of inequality?’ is not the biggest question we should be asking about history, what then should it be? As the stories of one-time captives escaping back to the woods again make clear, Rousseau was not entirely mistaken. Something has been lost. He just had a rather idiosyncratic (and ultimately, false) notion of what it was. How do we characterize it, then? And how lost is it really? What does it imply about possibilities for social change today?

For about a decade now, we – that is, the two authors of this book – have been engaged in a prolonged conversation with each other about exactly these questions. This is the reason for the book’s somewhat unusual structure, which begins by tracing the historical roots of the question (‘what is the origin of social inequality?’) back to a series of encounters between European colonists and Native American intellectuals in the seventeenth century. The impact of those encounters upon what we now term the Enlightenment, and indeed our basic conceptions of human history, is both more subtle and profound than we usually care to admit. Revisiting them, as we discovered, has startling implications for how we make sense of the human past today, including the origins of farming, property, cities, democracy, slavery and civilization itself. In the end, we decided to write a book that would echo, to some degree at least, that evolution in our own thought. In those conversations, the real breakthrough moment came when we decided to move away from European thinkers like Rousseau entirely, and instead consider perspectives that derive from those indigenous thinkers who ultimately inspired them.

So let us begin right there.

2. Wicked Liberty

The indigenous critique and the myth of progress

Jean-Jacques Rousseau left us a story about the origins of social inequality that continues to be told and retold, in endless variations, to this day. It is the story of humanity’s original innocence, and unwitting departure from a state of pristine simplicity on a voyage of technological discovery that would ultimately guarantee both our ‘complexity’ and our enslavement. How did this ambivalent story of civilization come about?

Intellectual historians have never really abandoned the Great Man theory of history. They often write as if all important ideas in a given age can be traced back to one or other extraordinary individual – whether Plato, Confucius, Adam Smith or Karl Marx – rather than seeing such authors’ writings as particularly brilliant interventions in debates that were already going on in taverns or dinner parties or public gardens (or, for that matter, lecture rooms), but which otherwise might never have been written down. It’s a bit like pretending William Shakespeare had somehow invented the English language. In fact, many of Shakespeare’s most brilliant turns of phrase turn out to have been common expressions of the day, which any Elizabethan Englishman or woman would be likely to have thrown into casual conversation, and whose authors remain as obscure as those of knock-knock jokes – even if, were it not for Shakespeare, they’d probably have passed out of use and been forgotten long ago.

All this applies to Rousseau. Intellectual historians sometimes write as if Rousseau had personally kicked off the debate about social inequality with his 1754 Discourse on the Origin and the Foundation of Inequality Among Mankind. In fact, he wrote it to submit to an essay contest on the subject.

IN WHICH WE SHOW HOW CRITIQUES OF EUROCENTRISM CAN BACKFIRE, AND END UP TURNING ABORIGINAL THINKERS INTO ‘SOCK-PUPPETS’

In March 1754, the learned society known as the Académie des Sciences, Arts et Belles-Lettres de Dijon announced a national essay competition on the question: ‘what is the origin of inequality among men, and is it authorized by natural law?’ What we’d like to do in this chapter is ask: why is it that a group of scholars in Ancien Régime France, hosting a national essay contest, would have felt this was an appropriate question in the first place? The way the question is put, after all, assumes that social inequality did have an origin; that is, it takes for granted that there was a time when human beings were equals – and that something then happened to change this situation.

That is actually quite a startling thing for people living under an absolutist monarchy like that of Louis XV to think. After all, it’s not as if anyone in France at that time had much personal experience of living in a society of equals. This was a culture in which almost every aspect of human interaction – whether eating, drinking, working or socializing – was marked by elaborate pecking orders and rituals of social deference. The authors who submitted their essays to this competition were men who spent their lives having all their needs attended to by servants. They lived off the patronage of dukes and archbishops, and rarely entered a building without knowing the precise order of importance of everyone inside. Rousseau was one such man: an ambitious young philosopher, he was at the time engaged in an elaborate project of trying to sleep his way into influence at court. The closest he’d likely ever come to experiencing social equality himself was someone doling out equal slices of cake at a dinner party. Yet everyone at the time also agreed that this situation was somehow unnatural; that it had not always been that way.

If we want to understand why that was, we need to look not only at France, but also at France’s place in a much larger world.

Fascination with the question of social inequality was relatively new in the 1700s, and it had everything to do with the shock and confusion that followed Europe’s sudden integration into a global economy, where it had long been a very minor player.

In the Middle Ages, most people in other parts of the world who actually knew anything about northern Europe at all considered it an obscure and uninviting backwater full of religious fanatics who, aside from occasional attacks on their neighbours (‘the Crusades’), were largely irrelevant to global trade and world politics.[37] European intellectuals of that time were just rediscovering Aristotle and the ancient world, and had very little idea what people were thinking and arguing about anywhere else. All this changed, of course, in the late fifteenth century, when Portuguese fleets began rounding Africa and bursting into the Indian Ocean – and especially with the Spanish conquest of the Americas. Suddenly, a few of the more powerful European kingdoms found themselves in control of vast stretches of the globe, and European intellectuals found themselves exposed, not only to the civilizations of China and India but to a whole plethora of previously unimagined social, scientific and political ideas. The ultimate result of this flood of new ideas came to be known as the ‘Enlightenment’.

Of course, this isn’t usually the way historians of ideas tell this story. Not only are we taught to think of intellectual history as something largely produced by individuals writing great books or thinking great thoughts, but these ‘great thinkers’ are assumed to perform both these activities almost exclusively with reference to each other. As a result, even in cases where Enlightenment thinkers openly insisted they were getting their ideas from foreign sources (as the German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz did when he urged his compatriots to adopt Chinese models of statecraft), there’s a tendency for contemporary historians to insist they weren’t really serious; or else that when they said they were embracing Chinese, or Persian, or indigenous American ideas these weren’t really Chinese, Persian or indigenous American ideas at all but ones they themselves had made up and merely attributed to exotic Others.[38]

These are remarkably arrogant assumptions – as if ‘Western thought’ (as it later came to be known) was such a powerful and monolithic body of ideas that no one else could possibly have any meaningful influence on it. It’s also pretty obviously untrue. Just consider the case of Leibniz: over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, European governments gradually came to adopt the idea that every government should properly preside over a population of largely uniform language and culture, run by a bureaucratic officialdom trained in the liberal arts whose members had succeeded in passing competitive exams. It might seem surprising that they did so, since nothing remotely like that had existed in any previous period of European history. Yet it was almost exactly the system that had existed for centuries in China.

Are we really to insist that the advocacy of Chinese models of statecraft by Leibniz, his allies and followers really had nothing to do with the fact that Europeans did, in fact, adopt something that looks very much like Chinese models of statecraft? What is really unusual about this case is that Leibniz was so honest about his intellectual influences. When he lived, Church authorities still wielded a great deal of power in most of Europe: anyone making an argument that non-Christian ways were in any way superior might find themselves facing charges of atheism, which was potentially a capital offence.[39]

It is much the same with the question of inequality. If we ask, not ‘what are the origins of social inequality?’ but ‘what are the origins of the question about the origins of social inequality?’ (in other words, how did it come about that, in 1754, the Académie de Dijon would think this an appropriate question to ask?), then we are immediately confronted with a long history of Europeans arguing with one another about the nature of faraway societies: in this case, particularly in the Eastern Woodlands of North America. What’s more, a lot of those conversations make reference to arguments that took place between Europeans and indigenous Americans about the nature of freedom, equality or for that matter rationality and revealed religion – indeed, most of the themes that would later become central to Enlightenment political thought.