Doug Sanders

Luna landing

Julia Butterfly Hill has gone from anonymous protester to media star since her two-year stay in a redwood. The preacher’s daughter knows how to use her strength of conviction to persuade others.

In Italo Calvino’s great novel The Baron in the Trees, the young hero escapes his cruel, nonsensical world by climbing to the roof of the forest and spending the remainder of his life there. He’s apart from the human community yet can engage with it. “He understood something else,” the tree-dweller’s brother explains, “something that was all-embracing, and he could not say it in words but only by living as he did.”

Who wouldn’t want to meet such a figure, if not be him? Or her, as it turned out. From the beginning, Julia Butterfly’s story had appeal: She lived for two years high in a tree she called Luna, a thousand-year-old redwood on the Northern California coast, on a plywood platform with rustling tarps and dangling ropes, barefoot and shivering, never setting foot on the Earth yet maintaining contact with its inhabitants through pulley-hoist visits and solar-powered phone calls.

She lowered herself to the ground this past December, after persuading a lumber company not to cut the tree down. Her book. Vie Legacy of Luna, will not need any Oprah endorsements or literary bona fides to capture our interest. It might better be called I Lived In A Tree, one of those singular facts like “I broke out of jail,” that trumps anything else this book might contain in Its 256 post-consumer-re-cycled, chlorine-free-bleached, aboriginal-produced, soy-ink-printed pages.

Tree girl did not seem entirely out of place in Beverly Hills on Saturday, when I met her before she spoke at an animal-rights awards ceremony. And yet she certainly did stand out Tall, elegant and pale, in a flowing red silk dress, she was the most charismatic person in a room full of professional eyefuls. She greeted me with a muscular handshake and a warm smile. “I’d sit down, but I don’t want to wrinkle this dress — it’s hemp,” she said. She looked around the antiseptic room. “I’d really prefer to be in nature. Can we go outside?”

We went outside, under a stand of palms and ferns, as Jaguars and Mercedes drifted by, and stood. “Any time I need that feeling of nature, I just go find it. Like this — I will go and hug a bush if that’s all! have, just to ground me with nature,” she said in carefully articulated tones. “I think one of our roles in society is placing value in the intrinsic nature of our soul, something deeper within us that’s not how much we make and spend. So I can find that fulfilment in nature anywhere — a mountain, a river, a stream, or, a palm tree next to a sidewalk.”

Julia Hill — Butterfly is her “forest name,” adopted by all tree-sit protesters, or bark-a-loungers as they sometimes call themselves — is the daughter of an itinerant preacher from Arkansas; the only schooling she received to the age 15 was at his side. You don’t need to be told this. She speaks with the cadence and force of a sermon, fixes you with a riveting stare and a sure voice, and has a proselytlzer’s skill at bringing any conversation around to the all-consuming concern of saving humanity.

She is both a gift and a nightmare to conventional environmentalists. She has brought a romantic heroism back to a movement that hasn’t seemed so exciting in years. After the great battles of the 1970s, environmentalism changed from a protest movement into an official bureaucracy, and ecology became just another branch of government. It is now about forestry-practices management debated between lawyers and regulators, and only Hill’s obstinate single-mindedness could cut through the tedium. Her supporters hope she will attract hundreds more activists.

On the other hand, because she does not speak their language, environmentalists fear she will begin speaking some other language altogether, or possibly start speaking in tongues. Hill writes of a car accident at age 17 that caused brain damage, shifting her consciousness from somewhat right-brained and practical to entirely left-brained and creative: She dropped out of her college hotel-management program and began hitchhiking across the country. It also seems to have turned her deep inside herself, to the point that human company no longer seemed important (when a TV producer asked her about her personal life last year, her answer was characteristic: “Who needs a boyfriend? I have a tree”). And it made her religious, complete with visions and voices from the woods.

While she is readily conversant in the minutiae of forestry economics and conservationist legislation, Julia Butterfly Hill’s mission is spiritual. Vie Legacy of Luna may be read as an environmentalist polemic or a Swiss-Family-Robinson adventure, but it only fully makes sense as the trial of a saint. There’s the long wandering ending with a calling (literally — after hitchhiking with friends, the tree spoke to her), the isolation from human society, the asceticism arid self-flagellation, the divine signs and the realization of a higher truth. She prays twice a day, and likens Luna’s trials to those of Jesus Christ, the loggers providing a ring of thorns, although she Is not a Christian. (She calls her deity the Universal Spirit, although her faith has many of the trappings of Christianity, including the fundamental guilt and repentance.)

“When I climbed into the tree, my consciousness was one where I thought our society was doing well,” she says. “Then I came out to the redwoods and said, oh my God, we’re still cutting down 2,000-year-old beings even though 97 per cent of them are already gone — what are we thinking? And then when I climbed into the literal perspective of the tree, it gave me a complete new figurative perspective on the world.”

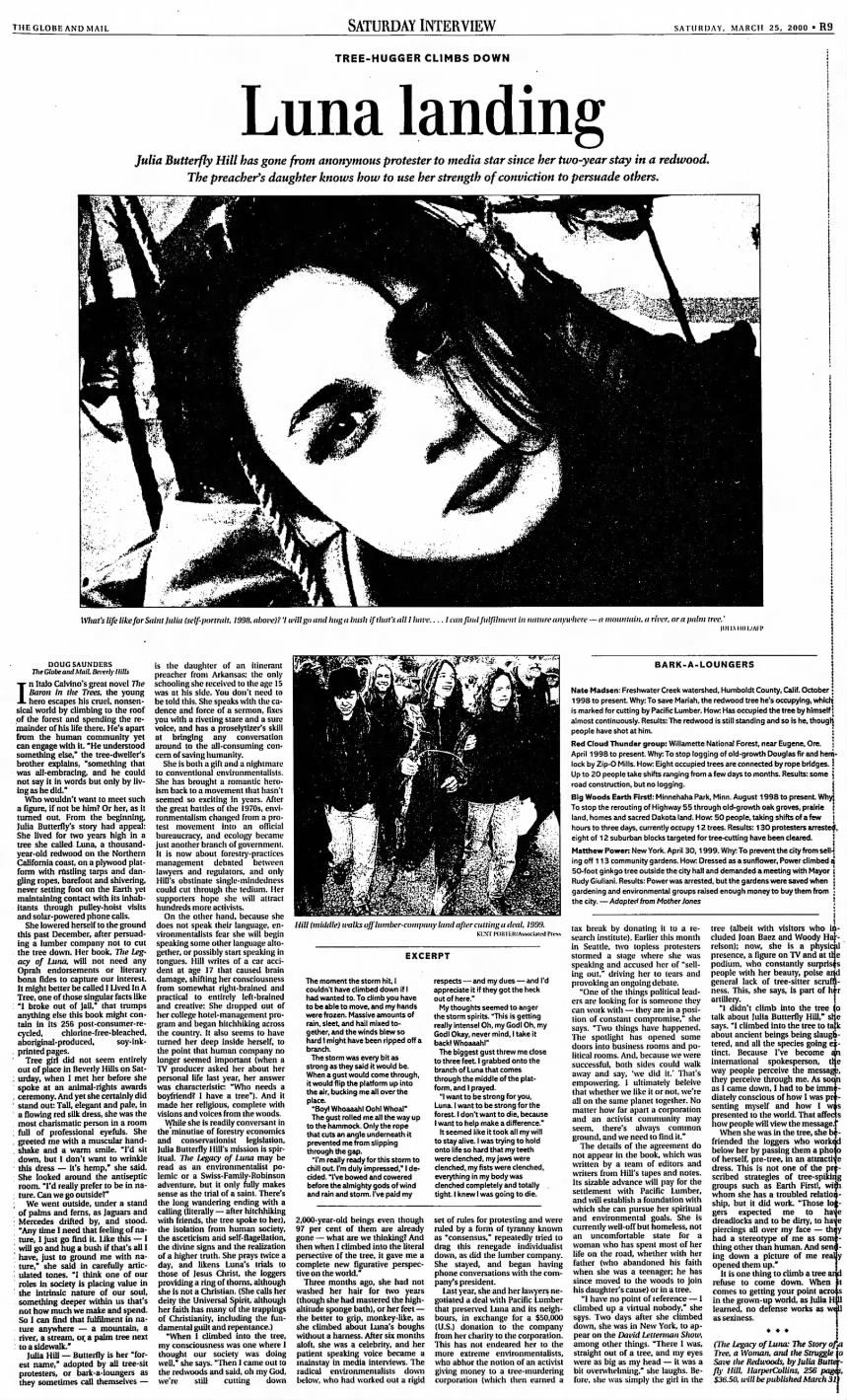

KENT PORTER/Associated Press

EXCERPT

The moment the storm hit. I couldn’t have climbed down if I had wanted to. To climb you have to be able to move, and my hands were frozen. Massive amounts of rain, sleet, and hail mixed together, and the winds blew so hard I might have been ripped off a branch.

The storm was every bit as strong as they said it would be. When a gust would come through, it would flip the platform up into the air, bucking me all over the place.

“Boy! Whoaaahl Oohl Whoa!”

The gust rolled me all the way up to the hammock. Only the rope that cuts an Jingle underneath it prevented me from slipping through the gap.

“I’m really ready for this storm to chill out I’m duly impressed,” I decided. “I’ve bowed and cowered before the almighty gods of wind and rain and storm. I’ve paid my respects — and my dues — and I’d appreciate it if they got the heck out of here.”

My thoughts seemed to anger the storm spirits. “This is getting really intensel Oh, my Godl Oh, my Godl Okay, never mind, I take it backl Whoaaahl”

The biggest gust threw me close to three feet I grabbed onto the branch of Luna that comes through the middle of the platform, and I prayed.

“I want to be strong for you, Luna. I want to be strong for the forest I don’t want to die, because I want to help make a difference.”

It seemed like it took all my will to stay alive. I was trying to hold onto life so hard that my teeth were clenched, my jaws were clenched, my fists were clenched, everything in my body was clenched completely and totally tight. I knew I was going to die.

Three months ago, she had not washed her hair for two years (though she had mastered the high-altitude sponge bath), or her feet — the belter to grip, monkey-like, as she climbed about Luna’s boughs without a harness. After six months aloft, she was a celebrity, and her patient speaking voice became a mainstay in media interviews. The radical environmentalists down below, who had worked out a rigid set of rules for protesting and were ruled by a form of tyranny known as “consensus,” repeatedly tried to drag this renegade individualist down, as did the lumber company. She stayed, and began having phone conversations with the company’s president.

Last year, she and her lawyers negotiated a deal with Pacific Lumber that preserved Luna and its neighbours, in exchange for a $50,000 (U.S.) donation to the company from her charity to the corporation. This has not endeared her to the more extreme environmentalists, who abhor the notion of an activist giving money to a tree-murdering corporation (which then earned a tax break by donating it to a research institute). Earlier this month in Seattle, two topless protesters stormed a stage where she was speaking and accused her of “selling out,” driving her to tears and provoking an ongoing debate.

BARK-A-LOUNGERS

Nate Madsen: Freshwater Creek watershed, Humboldt County, Calif. October 1998 to present Why: To save Mariah, the redwood tree he’s occupying, which is marked for cutting by Pacific Lumber. How: Has occupied the tree by himself almost continuously. Results: The redwood is still standing and so is he, though people have shot at him.

Red Cloud Thunder group: Willamette National Forest near Eugene, Ore. April 1998 to present. Why: To stop logging of old-growth Douglas fir and hemlock by Zip-O Mills. How: Eight occupied trees are connected by rope bridges. Up to 20 people take shifts ranging from a few days to months. Results: some road construction, but no logging.

Big Woods Earth First!: Minnehaha Park, Minn. August 1998 to present Why: To stop the rerouting of Highway 55 through old-growth oak groves, prairie land, homes and sacred Dakota land. How: 50 people, taking shifts of a few I hours to three days, currently occupy 12 trees. Results: 130 protesters arrested, eight of 12 suburban blocks targeted for tree-cutting have been cleared.

Matthew Power: New York. April 30, 1999. Why: To prevent the city from selling off 113 community gardens. How: Dressed as a sunflower, Power climbed q 50-foot ginkgo tree outside the city hall and demanded a meeting with Mayor Rudy Giuliani. Results: Power was arrested, but the gardens were saved when gardening and environmental groups raised enough money to buy them from the city. — Adapted from Mother Jones

“One of the things political leaders are looking for is someone they can work with — they are in a position of constant compromise,” she says. “Two things have happened. The spotlight has opened some doors into business rooms and political rooms. And, because we were successful, both sides could walk away and say, ‘we did it.’ That’s empowering. I ultimately believe that whether we like it or not, we’re all on the same planet together. No matter how far apart a corporation and an activist community may seem, there’s always common ground, and we need to find it.

The details of the agreement do not appear in the book, which was written by a team of editors and writers from Hill’s tapes and notes. Its sizable advance will pay for the settlement with Pacific Lumber, and will establish a foundation with which she can pursue her spiritual and environmental goals. She is currently well-off but homeless, not an uncomfortable state for a woman who has spent most of her life on the road, whether with her father (who abandoned his faith when she was a teenager he has since moved to the woods to join his daughter’s cause) or in a tree.

“I have no point of reference — I climbed up a virtual nobody,” she says. Two days after she climbed down, she was in New York, to appear on the David Letterman Show. among other things. “There I was, straight out of a tree, and my eyes were as big as my head — it was a bit overwhelming,” site laughs. Before, she was simply the girl in the tree (albeit with visitors who included Joan Baez and Woody Harrelson): now, she is a physical presence, a figure on TV and at the podium, who constantly surprises people with her beauty, poise arid general lack of tree-sitter scruffiness. This, she says, is part of her artillery.

“I didn’t climb into the tree to talk about Julia Butterfly Hill,” she says. “I climbed into the tree to talk about ancient beings being slaughtered, and all the species going e -tinct. Because I’ve become an international spokesperson, the way people perceive the message, they perceive through me. As soon as I came down, I had to be immediately conscious of how I was presenting myself and how I was presented to the world. That affects how people will view the message.)’

When she was in the tree, she befriended the loggers who worked below her by passing them a photo of herself, pre-tree, in an attractive dress. This is not one of the scribed strategies of tree-spiking groups such as Earth First!, with whom she has a troubled relationship, but it did work. “Those loggers expected me to have dreadlocks and to be dirty, to have piercings all over my face — they had a stereotype of me as something other than human. And sending down a picture of me really opened them up.”

It is one thing to climb a tree and refuse to come down. When it comes to getting your point across in the grown-up world, as Julia HUI learned, no defense works as wall as sexiness.

* * *

(The Legacy of Luna: The Story of a Tree, a Woman, and the Struggle to Save the Redwoods, by Julia Butterfly Hill. HarperCollins, 256 pages, $36.50, will be published March 31)