Douglas M. Kelley, M.D.

22 Cells In Nuremberg

A Psychiatrist Examines the Nazi Criminals

Chapter One: Pan-Germanism and Nazi Ideology

Chapter Four: Alfred Rosenberg

Chapter Seven: Baldur Von Schirach

Chapter Eight: Joachim Von Ribbentrop

Chapter Nine: Constantin Von Neurath & Franz Von Papen

Chapter Ten: Alfred Jodl & Wilhelm Keitel

Chapter Eleven: Karl Doenitz & Erich Raeder

Chapter Twelve: Ernst Kaltenbrunner

Chapter Thirteen: Julius Streicher

Chapter Sixteen: Wilhelm Frick & Arthur Seyss-inquart

Chapter Seventeen: Hjalmar Horace Greeley Schacht & Walther Funk

Chapter Eighteen: Albert Speer & Fritz Sauckel

IN NUREMBERG PRISON WERE....

THE MEN WHO TORTURED MILLIONS...

THE MEN WHO SENT OTHER MILLIONS

TO THEIR DEATH...

THE MEN WHO CAME CLOSE TO RULING

THE ENTIRE WORLD...

BUT WHEN THE BLACK UNIFORMS AND GOLD BRAID WERE STRIPPED AWAY—WHEN THE HIGH POLISHED BOOTS AND DREAD SWASTIKAS WERE REMOVED—WHEN THE SWAGGER AND THE BOMBAST WERE GONE—THEN WHAT MANNER OF MEN REMAINED?

DOCTOR KELLEY TALKED TO THEM AND LISTENED TO THEM AS THEY WAITED IN THE 22 CELLS IN NUREMBERG. HE TESTED AND EXAMINED. HE WATCHED AND STUDIED. THIS BOOK IS THE RESULT AND—FINALLY—WE CAN SEE THE RULERS OF NAZI GERMANY AS THEY REALLY WERE.

“I CONSIDER DOUGLAS M. KELLEY’S 22 CELLS IN NUREMBERG ONE OF THE THREE OR FOUR MOST IMPORTANT BOOKS THAT HAVE COME OUT OF WORLD WAR II.”

—Lewis M. Terman

Emeritus Professor of Psychology

Stanford University

Dedication

To June and Doc

This Book is the complete text of the hardcover book

A Macfadden Book ... 1961

COPYRIGHT 1947 BY DOUGLAS M. KELLEY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

PUBLIHED BY RRANGEMENT WITH CHILTON COMPANY,

PUBLISHERS

MacFadden Books Are Published by

MacFadden Publications, Inc.

205 East 42nd Street, New York 17, New York

PRINTED IN U.S.A.

Introduction

THIS IS NOT A BOOK FOR PSYCHIATRISTS, HISTORIANS, OR the uninformed. Psychiatrists and psychologists will find in the professional journals the reports of which this book is at the same time an abstract and an elaboration. For historians, the transcripts of interviews and other records from which much, but by no means all, of the data was taken will, I assume, eventually be made available. As for the third class—I am not inclined to burden this report with more detail than I judge a moderately well-informed reader will require to understand the personalities under examination.

No reader of newspapers, magazines, or contemporary historical literature needs to have retold the history of the Nazi Party. You will not find here a warmed-over account of Hitler’s rise to power, or the Munich Putsch, of the 1934 purge, or the 1944 assassination attempt. What you will find, I trust, is an intelligible analysis of the personalities which were able to warp and control the actions of 80 million Germans.

One of the most important values in civilization is what Korzybski has called “time binding”—the ability to learn from the past experience of others without having to go through it ourselves. It is imperative that we appreciate the horror of the Third Reich without experiencing it. The devastation of Europe, the deaths of millions, the near-destruction of modern culture will have gone for naught if we do not draw the right conclusions about the forces which produced such chaos. We must learn the why of the Nazi success so we can take steps to prevent the recurrence of such evil.

My method in this book will be to relate my conclusions about Nazism to what I learned from and about the top Nazis themselves. During the five months I served as Psychiatrist to the Nuremberg Jail, I interviewed every day at length some of the 22 men held there as war criminals. Except for the insane Hess, this was the first thorough mental checkup any of them had been given.

In addition to careful medical and psychiatric examinations, I subjected the men to a series of psychological tests. Such tests are of accessory value in supplementing medical observations and providing objective data for the case history. The most important technique employed was the Rorschach Test, a well-known and highly useful method of personality study. A few of the criminals were given Thematic Apperception Tests, a projective technique utilizing standard pictures about which the subject makes up a story. The intelligence estimations were made from a German adaptation of the Wechsler-Bellevue Test devised by my assistant, Dr. Gustave Gilbert, the prison psychologist and then a captain in the A.U.S. Dr. Gilbert was also assigned to my office as an interpreter and, at my direction, made records of many of the conversations which I had with these prisoners and which are reported in this book.

The language problem was an important one in some instances; but for the most part, the chief criminals spoke fairly good English. I always used interpreters to prevent misunderstandings, however, in important discussions. Frequently, I would rotate interpreters on different days, getting the same information through rephrasing the questions. In this way I was able to check on the quality of the interpretations and properly evaluate my findings.

As a psychiatrist, I interviewed first of all the men themselves. But, realizing that their prison personality patterns would naturally reflect a desire to curry favor, and for the further reason that any honest testimony is usable in psychiatric synthesis, I also obtained interviews with and written reports from a number of persons who had known the Nuremberg Nazis when they were at the top of the heap.

Such outside evidence provided confirmation that all of the prisoners were exhibiting various degrees of depression. The following excerpts from a letter which one of them wrote to his wife is generally indicative of the hopelessness and discouragement all 22 displayed in greater or lesser degree.

“I doubt whether anyone can understand our state of mind without having experienced all this. The worries about the closest members of the family, the sons missing in action, the destroyed property, and all the personal pain about the whole country, about other relatives, the painful thoughts about the future without any regard to our own fate—all this is so unique that it can only be compared with the Thirty Years’ War of destruction. The great difference is that the catastrophe came within two years and to an extent never witnessed before. We intended to build a more beautiful Germany; instead we now have a heap of rubbish, unimaginable, and not to be eliminated in decades.”

Such a wealth of data was available—from associates, moving pictures, speeches, writings, and other records—that I was able to verify virtually every facet of character of every person under examination. For the record, all historically significant material in this report is based on a minimum of two, and generally three, witnesses. In many instances, I have not revealed the source of my information. But each has been authenticated, and the information is available to interested and qualified individuals.

Complete studies of the personalities discussed in this book are under way. They will be published in the professional journals in due time.

I wish to express here my deepest appreciation to Lt. Col. Renee Juchli who, as Chief Medical Officer of Nuremberg Jail, gave wholehearted support to my studies. I am grateful also to the other members of the medical and nursing staff and, particularly, to Lt. Dorothy Mears who was instrumental in obtaining data from the female prisoners among the lesser Nazis in the jail. I am also grateful to the Commanding Officer of the Internal Security Detachment, Col. B. C. Andrus, who facilitated my work at every step.

Without the support of Drs. Richard M. Brickner, D. Ewen Cameron, Nolan D. C. Lewis, John A. P. Millet, and Margaret Mead, I should never have attempted a book for the lay reader. Without the generous aid of Mr. Nathan Schulman, I should certainly never have completed it.

I owe a debt of thanks also to the many translators who aided me in obtaining various manuscripts and in converting them to English for my use. The Department of State Publication #1864 and other translations were most helpful, as was the work of Mr. T. H. Tetens, head of the Germanic Library in New York City.

Mr. Charles Burnes shared the burden of editorial collaboration in preparation of the manuscript, and I am deeply indebted to him for the time and energy he put into this most difficult task.

Part One: The Environment

What is normal for a pagan barbarian may not be for a creature of a Christian-industrial-twentieth-century culture. Since my return from Europe where I was Psychiatrist to the Nuremberg Jail, I have realized that many Americans—even well-informed ones—do not grasp that concept. For too many of them have said. to me:

”What kind of people were those Nazis really? Of course, all the top fellows weren’t normal. Obviously they were insane, but what sort of insanity did they have?”

Insanity is no explanation for the Nazis. They were simply creatures of their environment, as all humans are; and they were also—to a greater degree than most humans are—the makers of their environment. Though this is not the place to recapitulate the growth of their ideologies, or of their Party, nonetheless I believe that the psychological bent of the 22 Nuremberg Nazis will be more readily apparent if we refresh our memory by recalling the cultural matrices by which they were conditioned.

Chapter One: Pan-Germanism and Nazi Ideology

THE NAZIS AND THE GERMANY THEY MADE ARE EXCELLENT proof of the hypothesis that cultural retrogression can be fostered perhaps more readily than cultural progress. The seeds of progress are always present in every culture, but they need careful cultivation and weeding, encouraging sunlight and showers.

Also present in every culture are the roots of primitive loyalties and hatreds requiring only stimulation to spurt into rank growth. The Nazis guided and led Germany into neo-paganism and barbarism simply by applying a heavy dressing of hate-rousing propaganda and then effective direction to forces already latent in the nation’s makeup. Let me illustrate with three quotations:

First: “It is necessary that our civilization build its temple on mountains of corpses, on an ocean of tears, and on the death cries of men without number.”

Second: “Frankly, we are and must be barbarians... Every act, no matter what the nature, committed by our troops for the purpose of discouraging, defeating, and destroying our enemies is a brave deed, and is fully justified... We should not worry about the opinions and reactions in neutral countries... They call us barbarians. What of it? We scorn them and their abuse... Our troops must achieve victory. What else matters?”

Third: “The new Europe will be a continent restored to barbarism... And this time the foundation for the new Europe will be laid, not by priests and diplomats, but by pirates of destiny... Now, at last, we may frankly confess that the Gospel has lost all meaning for us.”

The origins of those three statements of policy—and, make no mistake, they voiced a continuing German policy—are: For the first, General Count von Haesler, in an address to his troops in 1893; for the second, Major General von Disfurth, in the Hamburger Nachrichten, November, 1914; for the third, Jankow Janeff of the staff of Alfred Rosenberg, in his book Heroism and World Fear, 1937.

It is evident that the Nazis alone did not reverse the stream of German culture; the cult of barbarism had live roots there still in 1923.

Nor did Hitler and Rosenberg invent the myth of the German super-race. Here is evidence in the same sequence: “We are the salt of the earth ... God created us so that we should civilize the world.” (Kaiser Wilhelm II, in his Tangier speech, 1905.)

“The Germans are the chosen people of the earth. They will accomplish their destiny, which is to direct the world and to govern other nations for the good of humanity.” Professor von Seyden, Frankfurter Zeitung, 1914).

“... The Government has decided to extend the German order over the whole world. The world will have to reckon with German economy, with German soldiers, and cannon.” (Dr. Goebbels, in a speech on March 23, 1936.)

The depreciation of ethics, of conscience as a guide to conduct, reached its prime expression in the Nuremberg Nazis. But the way had been prepared. Pedants, generals, and priests had long taught that no moral scruples should stay a hand raised to strike for the German State. Some persons may assume that a higher morality guided Germany’s rulers during the years of the Weimar Republic, but the evidence does not support wishful assumptions. Here is the boastful testimony of Dr. Karl J. Wirth, leader of the Catholic Center Party and Chancellor of the Republic from 1921 to 1922, from the Luzerner Tageblatt, August, 1937:

“As to the rearmament of Germany, Hitler has only continued the rearmament that had been prepared by the Weimar Republic. I, myself, deserve great credit for this prepation ... The great difficulty was that our military efforts had to be kept secret from the Allies ... When Hitler came to power he no longer needed to concern himself with the quality of the German Army but only with the quantity. The real reorganization was our work.”

What of Nazi Germany’s slave-labor policy? The following statement of Ernst Haase, Leipzig University professor and President of the Pan-German League, dates back to 1905, and anticipates the crimes of Frank, Rosenberg, and Sauckel.

“Who in the future is to do the heavy and dirty work which every national community based on labor will always need? ... Is it to be left to any part of our German people to occupy such slaves’ positions? The solution consists in our condemning alien European stock, the Poles, Czechs, Jews, Italians and so on... to these slaves’ occupations.”

These are but a few, not one-hundredth of the whole, of the specific incitements with which the German people were bombarded over the last half century. One can add to them nearly two hundred years of philosophical generalizations in the same tone—the writings of Herder, Schlegel, Schelling, Hegel, Mueller, List, Gobineau, Wagner, and Chamberlain. It was the racial theories of Richard Wagner and his English son-in-law, Houston Stewart Chamberlain, which aroused the nineteenth-century anti-Semitism of Germany and prepared the people for the appalling pogroms of the Nazis.

Other German ideas which the Nazis utilized were those of the Fuehrer Principle, the Folk Hero (Hitler), and the Elite Class (the Party). What Hitler did was to take over these established German concepts and simplify them, make them more primitive. They were already emotionally a part of the people; and when Hitler re-emphasized them, he mobilized the entire emotional content of the people for his Reich.

It is when we understand this that we realize how Hitler and his henchmen were able to take over 80 million men, women, and children, bodies and minds.

Hitler found a people previously conditioned to several explosive ideologies, frustrated by defeat, hungry, wearied by inflation—and homogeneous. He won their attention by promising them solutions for the most pressing problems—food and shelter, and the indignities of defeat. He next captured emotional control of them by appealing to their conditional beliefs and concepts—anti-Semitism, the tribal mores of a warrior nation, and so on. From then on he did with them what he wished.

It is an established scientific fact that a person who is thinking with the emotional (thalamic) brain centers cannot think intellectually (cortically). Hitler had an entire people thinking with its thalamus. In such state they fell easy prey to Goebbels, Streicher, Ley, and the other propagandists. For those who refused to think emotionally and follow him there were such even after 1933—he contrived the concentration camp. And there was always the bullet-pitted prison wall.

Chapter Two: Nuremberg Jail

NUREMBERG WAS A “TOUGH” JAIL. THE FACT THAT TWO of the 22 top Nazis imprisoned there managed to commit suicide does not change that fact. In Nuremberg Jail the former elite of Germany tasted the bitter gall of their own boastful words. All of them ate there their promises of victory; many of them re-ingested the hosannas they had spewn to Hitler. Since this jail, with its implications of defeat, frustration, and indignities, was the environment of these men during the period they were studied, it is worth while to review briefly just how it was run.

The prison block which housed the war criminals was a three-storey structure with a wide corridor running the length of the ground floor. Cells lay on both sides of the corridor, and at either end circular stairways led to the two upper tiers of cells. The catwalks along these upper tiers were screened to prevent any suicidal leap to the corridor. Before and during the trial, the major Nazis were all housed on the ground floor. In the end only those sentenced to be hanged remained there, and the others were moved to upper tiers before they were finally taken away to Spandau Prison in a Berlin suburb.

The individual cells were about nine by thirteen feet. A heavy wooden door several inches thick was centered in the nine-foot wall, on the corridor side. Opposite it was a high, barred window opening into a court. In the center of the door at about chin height was a small drop door about fifteen inches square. This was kept open at all times. The door, opening down, jutted out at right angles into the cell and formed a small shelf on which the prisoner’s meals were placed.

The cells were furnished each with a steel cot fastened to the wall at one side of the door. Opposite it were a lavatory bowl and toilet, the latter without wooden cover or seat. The only other furnishings were a straight chair and a flimsy table on which prisoners were allowed to keep pencil, papers, family photographs, tobacco, and toilet articles. All other personal possessions had to go on the floor. Most of the prisoners kept extra clothes, linen, and so forth, arranged in piles between the foot of the cot and the window. Hess added to these the various small packages of food which he persisted in saving to submit to chemical analysis, one of his delusions being poisoned food.

The only time when a prisoner could be out of sight was when seated on the toilet. Even then his feet remained visible to the guard. Prior to the suicide of Robert Ley, one guard was assigned to watch each four prisoners; thereafter, a guard was on duty at each cell door twenty-four hours a day.

The cells were lighted by an electric bulb in a reflector fastened to the outer side of a grille which fitted into the small door. This light burned with constant brilliance, except during sleeping hours when it was dimmed. Even then it remained bright enough for reading. The reflector was about twelve inches in diameter and covered most of the grille, forcing the guard to peer around the edges at the prisoner.

It was the Jail’s strict rule that head and hands of the prisoner must remain visible all the time he was in bed. Prisoners who snuggled down too cozily during the cold winter nights were brusquely wakened by worried guards, occasionally forced to turn ends about on the cot and sleep facing into the light where they could be better watched.

But, tough as it was, nearly 10 per cent of its top Nazi criminals “escaped” the jail by suicide. The human element is the decisive one in even the harshest prisons. The four-cell guard never suspecting Ley’s “puttering” in the toilet area as he prepared his own strangulation. Goering’s guard never saw him slip into his mouth the tube of potassium cyanide. In any event, once Goering had the poison in his possession, the guard could not have prevented his suicide.

The cell searches, which it was admitted might have been “perfunctory” in the days before the suicide and executions, were another practice typical of a tough prison. Once a week, twice, perhaps four times or oftener, the prisoner could expect a “shakedown.” In this the prisoner was forced to strip and stand in a corner of the cell while M.P.’s went carefully through his bedding, clothing, papers, and other impedimenta. In my months at Nuremberg these shakedowns were so thorough that prisoners needed some four hours to restore their cells to order.

Once a week the prisoners were marched to a shower room where they bathed under supervision. They were allowed to keep one outfit of their own clothing, with several changes of linen, socks, and so on in their cells. Class X (unfit for further Army use) fatigues were issued for lounging and policing their quarters. These “beat-up” GI work clothes were the only garments Streicher and Ley had for months. Before the trial began, the United States Army secured from their families one suit for each prisoner to wear into court.

No suspenders, belts, or shoelaces were allowed in the cells; nor, of course, was anything remotely resembling a weapon. During the trial all laces, braces, and such items were taken away from the prisoners as soon as they returned from courtroom to cell. At first no string of any sort was allowed but, eventually, each of the elderly men who wore shoes was issued two four-inch pieces of thin string to tie through the top holes of his shoes so he need not shuffle as he moved about his cell and the exercise yard.

This yard, about a block square, lay at one side of the cell block. One prisoner would walk fifteen minutes at a time up and down one side of the walled yard while another, within hailing distance but forbidden to communicate, paced up and down the other side.

When the prisoners were moved from Mundorf to Nuremberg some two months before the trial, they had been in confinement for three months. Goering I had seen and treated regularly for his drug addiction at Mundorf; Hess (who reached Nuremberg some time later) had been under British medical care. The others were held virtually incommunicado. Their guards maintained a stony silence except to correct them harshly for some breach of the strict discipline; even the waiters who brought their food were forbidden to return their greetings.

When I came to Nuremberg, therefore, I found a group of “patients” eager to talk. Seldom have I found psychiatric interviews so easy as were most of these. Then and thereafter they talked almost without probing or prompting.

There were exceptions, of course. It is a psychiatrist’s technique to gain the confidence of those in his care—by honestly earning it. But I never succeeded in getting Hess, for instance, to let down the barriers he had erected between himself and reality. Jodl, Raeder, and Seyss-Inquart remained relatively stiff and formal throughout our acquaintance. Doenitz and Ribbentrop, on the other hand, became quite friendly in their attitude toward me, while Goering was positively jovial over my daily coming and wept unashamedly when I left Nuremberg for the States.

As a scientist I regarded my duty in the Jail to be not only to guard the health of men facing trial for war crimes but also to study them as a researcher in a laboratory. I shared the opinion of ethnologists and politicians alike that Nazism was a socio-cultural disease which, while it had been epidemic only among our enemies, was endemic in all parts of the world. I shared the fear that sometime in the future it might become epidemic in my own nation.

Medical men know that when they isolate the germ or virus that causes disease among men, they can prepare a vaccine or serum that will protect us against it. I had at Nuremberg the purest known Nazi—virus cultures—22 clay flasks as it were—to study, and with but a short time in which to work. I took upon myself to examine the personality patterns of these men and, to a degree, the techniques they employed to win and hold power. Though my work was hurried and incomplete, I believe it was sufficiently fruitful to indicate which way we Americans should turn our thoughts and our education, our policies and our political methods, if we are to avoid the sad fate of the Germans.

The Criminals

| Rudolf Hess | b. Jan. 12,1893 | Serving life imprisonment |

| Alfred Rosenberg | b. April 26,1896 | Hanged, Nuremberg Jail, Oct. 16, 1946 |

| Hermann Goering | b. Jan. 12,1893 | Committed Suicide, Nuremberg Jail, Oct. 15, 1946 |

| Hans Fritzsche | b. April 21,1900 | Freed by International Tribunal |

| Baldur von Schirach | b. May 9,1907 | Serving 20 years’ imprisonment |

| Joachim von Ribbentrop | b. April 30,1893 | Hanged, Nuremberg Jail, Oct. 16, 1946 |

| Constantin von Neurath | b. Feb. 2,1873 | Serving 15 years’ imprisonment |

| Franz von Papen | b. Oct 29,1879 | Freed by International Tribunal |

| Alfred Jodi | b. May 10,1890 | Hanged, Nuremberg Jail, Oct. 16,1946 |

| Wilhelm Keitel | b. Sept. 22, 1882 | Hanged, Nuremberg Jail, Oct. 16,1946 |

| Karl Doenitz | b. Sept 16,1891 | Serving 10 years’ imprisonment |

| Erich Raeder | b. April 24, 1896 | Serving life imprisonment |

| Ernst Kaltenbrunner | b. Oct. 4, 1903 | Hanged, Nuremberg Jail, Oct. 16,1946 |

| Julius Streicher | b. Feb. 12,1885 | Hanged, Nuremberg Jail, Oct. 16,1946 |

| Robert Ley | b. Feb. 15,1890 | Committed suicide, Nuremberg Jail, Oct., 1945 |

| Hans Frank | b. May 3,1900 | Hanged, Nuremberg Jail, Oct. 16,1946 |

| Wilhelm Frick | b. March 12,1877 | Hanged, Nuremberg Jail, Oct. 16,1946 |

| Arthur Seyss-Inquart | b. July 12,1892 | Hanged, Nuremberg Jail, Oct. 16,1946 |

| Hjalmar Horace Greeley Schacht | b. Jan. 22,1877 | Freed by International Tribunal |

| Walther Funk | b. Aug. 18,1890 | Serving life imprisonment |

| Albert Speer | b. March 19,1905 | Serving 20 years’ imprisonment |

| Fritz Sauckel | b. Oct. 27, 1894 | Hanged, Nuremberg Jail, Oct. 16,1946 |

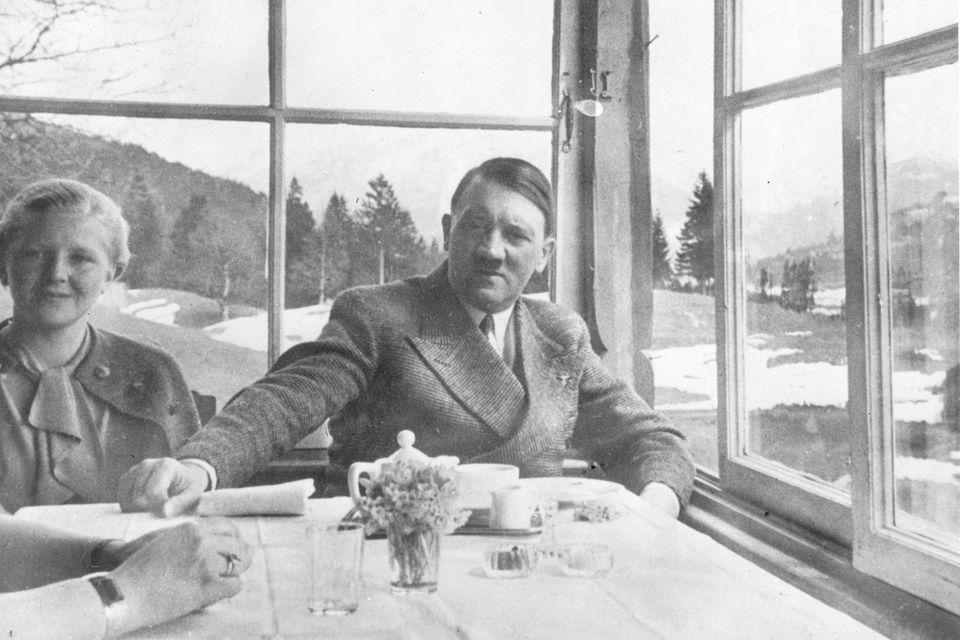

| ADOLF HITLER | b. April 20, 1889 | Fate undetermined |

Part Two: The Policy Makers

Adolf Hitler was without question the principal maker of policy for the Nazis tried at Nuremberg, as well as for the National Socialist Party and, between February, 1933 and May, 1945, for all Germany. My analysis of what manner of man Hitler was will follow all the others for the reason that my information about him was largely obtained from his imprisoned aides. And for the further reason that, in the psychiatric profile of each of them, the reader will find some feature which bears a trace of Hitler influence. When we are through with all the rest, these trace elements of character will lend detail to the picture of Der Fuehrer. I shall discuss here, therefore, only three policy makers—Hess, Rosenberg, and Goering.

These three men were among the “elite” whom the Nazi Party, faithfully following the ancient German recipe, developed as officers directly subservient to Hitler and acting as his advisers (insofar as anyone dared). Not all of the officers were policy makers. The men who actually were important in the policies and affairs of state were few. Two, Goebbels and Himmler, committed suicide and were never tried. Of the lot that stood trial, only Goering, Rosenberg, and Hess were really influential. They were actually responsible for parts of Hitler’s basic theory—Hess and Rosenberg in the twenties and early thirties, and Goering after the Party came to power.

Chapter Three: Rudolf Hess

PROBABLY NO FIGURE IN RECENT YEARS HAS BEEN THE subject of so much publicity and wild guessing as has the one-time deputy of Adolf Hitler, Rudolf Hess. Until May 10, 1941, when he made his dramatic flight to England, Hess’s role in German history was simple and unimpressive. Since that time, however, virtually every intelligent, informed person in the world has at some time speculated on the personality of this puzzling Nazi and the reasons for his flight. Hess’s action is logical only if we can understand his basic psychic structure.

Because Hess had had a psychotic episode while under detention by the British, and because I wanted to clear his mind and keep him in shape for trial, I spent hours at a time, for weeks on end, in his cell. Though he spoke English well and answered most questions quite readily, I never succeeded in getting him to be friendly. He was almost constantly on guard, aloof, clicking his heels and saluting. One day when the question of his treatment came up he explained his attitude: “You are kind, yes. But I do not know if you are a friend. I shall wait until the trial is finished. Then I will know if you are a friend or not a friend.”

Though he was not insane while under my care, Hess could not at any time be called a normal person. He had left Germany at a time when the Reich was master of Europe and potential master of the world. He believed passionately in Germany’s final triumph. As time wore on and the tide of battle turned, his fanatical mind would not accept the growing magnitude of Germany’s defeat. When the end did come, he still insisted upon childish play acting as the deputy of a Fuehrer who was no more. The answering of personal questions he regarded as beneath his dignity.

Hess was an Ausländer, born in Alexandria, Egypt. He was taught by a private tutor until he was fifteen, when he was sent to Germany to complete his education. As a university student he met Karl Haushofer, the famous German professor of geopolitics, who became a sort of second father to him.

When the First World War began, Hess joined immediately the same regiment to which Hitler belonged. Apparently he did not then meet the future Fuehrer, though they served together for three years. Hess left the regiment after receiving a chest wound in 1917. He transferred to the air force and had just become a flier when hostilities ceased.

Following the defeat, Hess drifted to Munich where he took part in the hoodlumism of an anti-Semitic group and, during one street fight, was wounded in the leg. Here he again came under the influence of his old professor, Haushofer, at whose urging he eventually became a member of the Nazi Party.

A vigorous, belligerent member of the early Nazi fighting group, Hess suffered various injuries in many brawls. A quarter of a century later he still boasted scars. In the putsch of November 9, 1923, he played an important role, being assigned to seize several Bavarian leaders as hostages. When the putsch failed, Hess escaped into Austria but later returned and was sentenced to prison in Landsberg Fortress where Hitler was also incarcerated.

Here Hess served as Adolf Hitler’s secretary, taking down, to Hitler’s dictation, the greater part of the Nazi bible, Mein Kampf. (Hess had studied stenography before the war in anticipation of returning to his father’s export-import business.) But he did more than merely set down the words of his master. He instilled into Hitler and into the book the “science of German conquest” which Haushofer had taught him. (Rosenberg, a regular visitor to the prison, also contributed his bit to the book.) It was during this period, in a relatively pleasant prison, that Hess became a close confidant of Hitler and achieved the status which made him finally Deputy Fuehrer of Greater Germany.

From this time forward, Hess was Hitler’s staunchest supporter, constantly demanding wholehearted support from other Nazis. His service to Hitler consisted in acting for the Fuehrer, partly as secretary and partly as deputy at minor state affairs. He developed some antagonism to Goering during the early power period. The two competed for control of various aspects of aviation, and Hess always came off second best. Throughout his entire political life, in fact, Rudolf Hess ran a good second, but always second, to somebody else in the Nazi Party.

Hess was tremendously enthusiastic about the ideals of the Party and was carried away by the organization, its uniforms and parades, its bands and spectacles. He apparently believed in the Nazi theories and worshipped Adolf Hitler as a god. As Nazism succeeded, Hess became more and more attached to and dependent on the Fuehrer who assumed the role of a mystic father in the eyes of his deputy. Hess, whose own father had sent him to Germany to school when he was only fifteen, told me of his relationship to Haushofer and Hitler. He stated that the former took him into his household where “I became as one of the family.” Alone in what to him was a foreign country, he became very attached to Haushofer and readily substituted his teacher for his father. This early break from his own parents, and his refusal to follow in his father’s footsteps as an exporter to Egypt, made his later attachment to Hitler psychologically easier. The break had cast him adrift; in consequence, his juvenile personality sought someone to dominate him. Hitler supplied this need. We find Hess readily running Hitler’s errands, acting as his secretary, doing odd jobs, and in general acting as Hitler’s “little boy.” All through his life Hess has carried out this pattern. His emotions were primarily directed toward his superiors, his father surrogates, rather than toward his wife and children with whom he spent little time and to whom he demonstrated little affection.

As an official, Hess was an extremely hard worker. Everything about his office was well organized. He demanded a tremendous amount of work from his associates and was particularly concerned whenever he had to make a speech. Goering once snorted, “Whenever he had to talk in public, Hess sweat blood.” Baldur von Schirach, Hitler’s youth leader, made much the same comment.

Hess was a constant sufferer from physical complaints which obviously were psychological in origin. He went for years from physician to physician trying all sorts of cures, and if a result was not achieved in a week or two, he would get a new doctor. Finally he lost confidence in the entire medical profession, and thereafter resorted to quacks, nature healers, and astrologers. He eventually established the Rudolf Hess Hospital for the sole purpose of testing cures which were not recognized by the medical profession. All his own searches for cures were apparently fruitless, for his complaints, primarily pain in his stomach, were not cured.

One day I was talking with him about diagnosis when he inquired, “Do you know about the studies of the size of the pupil of the eye?”

I said, “You mean studies of the back of the eye with an ophthalmoscope?”

“No,” he replied, “I mean the pupil—the black opening in the eye.”

“Well,” I said, “I know it expands and contracts.” He interrupted me a bit scornfully, since I obviously did not know what he was driving at. “I mean the science of diagnosis based on the size and shape of the pupil. Haven’t you heard of it?”

He had me there, and I admitted it.

Hess then went on, “It really hasn’t been accepted by doctors in Germany either, but a scientist—he wasn’t a medical man and I studied it a long time. By the change in the pupil, you can not only tell what is wrong with anyone, you can tell where his illness is.”

When I expressed a bit of doubt, Hess became aloof and distant. “I quite realize that an American medical man would not believe this,” he said, “but it is quite true; even I can do it a little.”

He fixed his eyes on mine, and for a moment I was afraid he would label me with some disease. Apparently all he discovered was disbelief, for he indicated that the interview was at an end.

Later I found out that he had a long talk with the German physician, who was helping us, about my qualifications, and referred to the “poor training” given in the United States, where they did not even know about this technique.

The next day Hess felt better about it. He said he realized that I did not know too much of such methods, but after the trial he would look up his associate and see if he could train me! I expressed sincere appreciation. I would like to meet a man who could sell such an idea to anyone—even the gullible Hess.

A highly introverted individual, Hess was known as a polite and chivalrous man. He seldom expressed anger with anyone but always “swallowed his ire” and buried his annoyance within himself. In a group characterized by hedonism, he was outstanding for his lack of bad habits, and for the staid sobriety of his personal life.

His colleagues were inclined to view as his only “vice” his ardent belief in astrology. All the high Nazis mentioned this “weakness” of Hess’s and swore that it was only he, and not Hitler, who collected horoscopes and followed their prognostications in the conduct of his own—and state-affairs.

Never sound, Hess’s health gradually became worse after the years of easy victories over the German people. From Munich on, he lost weight; his determination and drive seemed to be burned out; and he frequently spent long periods at his desk gazing into space. In addition, he grew extraordinarily suspicious of his colleagues—probably unconsciously imitating Hitler who exhibited the same mood of suspicion at this time. (From his history it was obvious to me that he was a basic psychopathic personality with marked hysterical bodily symptoms and fundamental paranoid trends.) By 1940 he was in a state of mind bordering on a severe neurotic breakdown.

His grievous mental state can probably be traced to his discovery, after the Polish war began, that his father substitute, Hitler, was not a god but a cruel and violent person. This must have been deeply disturbing to Hess’s tender mind. The shock was not lessened when he learned, early in 1941, that Hitler planned to violate a basic precept of his earlier father substitute, Haushofer: never to engage in a two-front war by attacking Russia.

In this unhappy circumstance, physically and mentally ill and no doubt brooding over his own always-secondary status, Hess conceived his plan. To him it was logical. It was even brilliant. His logic was that of a sick man fed on fallacies: Were not the Nordic Germans the world’s finest men, led by the world’s greatest man? Would not the English gladly grant that the Germans had already won the war? Would not they, being themselves only slightly mongrelized Nordic cousins of the Germans, recognize the threat of Oriental Communism and approve a German attack to the East?

In Hess’s reasoning the only answer to each of these questions was “yes.” Therefore, all he need do to establish his undisputed right to be Hitler’s successor (and crowd out once and for all the gross Goering) was to achieve, by one brilliant stroke of statesmanship, peace between Germany and England.

In the end, Hess told me, more than “logic” played a part in his decision to fly to England. In late 1940, one of his astrologers read in the stars that Hess was ordained to bring about peace. Later his old professor, Haushofer, told Hess of a curious dream he had had of Rudolf Hess, the German born in Egypt, striding through the tapestried halls of English castles, bringing peace between the two great nations, peace to all the world. All this was strong incitement. How could weak Hess, emotionally immature, an intellectual adolescent, withstand such pressure? He couldn’t. As a matter of fact, he told me he had been so eager to fill his great role that he had made two hasty attempts before he succeeded in reaching Britain. Both attempts were turned back by bad weather. Finally, on May 10, 1941—six weeks before Hitler’s D-Day in Russia—Hess flew over Scotland and parachuted from a height of 20,000 feet. I asked him why he jumped and he said, “I had never flown that type of plane before and wasn’t sure I could land it. Then, too, I was uncertain of the location of the English fields. I did a good job, though, and struck the ground thirteen feet from where I planned.”

Hess was dressed in the uniform of a captain of the German Luftwaffe and gave the name of Alfred Horn, stating that he was on a special mission to the Duke of Hamilton. Haushofer had told him the Duke was an Englishman who would understand the German point of view.

Instead of arranging a treaty through the Duke of Hamilton or any others he asked to see, Hess was thrown into jail. His claim to plenipotentiary status was laughed at. His ego was bruised but, still basing his acts on the assumption that the English regarded themselves as certain to be defeated, he offered ridiculously one-sided terms. Germany would retain all conquered territories, repossess its former colonies, and be free to conduct any type of armed aggression against Russia. In exchange, Germany would magnanimously yield England a free hand in its own Empire. Hess added one other term: since the Churchill government was definitely anti-German, an entirely new English government would have to be selected. It was incomprehensible to him that the British would not discuss his terms.

Four and a half years afterward he was still angry. He told me of his treatment:

“I was taken to a prison somewhere in England where all they did was ask me military questions. I denied any knowledge of military events, and demanded my rights as an emissary. The English would then ask me, ‘Do you have anything to show that you are an emissary?’ I would reply, ‘Of course not. I am the Fuehrer’s deputy.’ They would then ask, ‘Did the Fuehrer send you?’ I would reply, ‘He knows nothing about my mission.’ So the English would say, ‘Then you are a captured aviator, a prisoner of war. Tell us about the disposition of your troops.

“I would ask to see the Swiss envoy, and they would reply that the Swiss envoy did not see ordinary prisoners of war—and what was the disposition of our air force? Then I would demand that they take me to see the highest representative of the king. They would say that certainly this would be done in a few days—and what was the disposition of our U-boats?

“I became extremely angry and said I would not answer questions dealing with military matters, that I was on a diplomatic mission and should be rendered full diplomatic privileges. Then the English would say, ‘Didn’t you bail out over Scotland in the uniform of a captain in the German air force?’ I would say, ‘Naturally. I didn’t want to be taken for a spy.’ So the English would reply, ‘Then, as far as we’re concerned you will be treated as a captain in the air force. Come along now, tell us about the disposition of our troops.”

Hess was held prisoner by the British from the date of his arrival until October 10, 1945. Under the constant badgering of questioners, he at first became depressed over the failure of his mission, and then later developed definite insanity, characterized by delusions that the English were poisoning his food in an attempt to kill him or make him lose his mind. While insane, he made two attempts at suicide. At length he developed a total amnesia.

With the development of the amnesia, his insanity cleared. Then, in the spring of 1945, the amnesia itself also disappeared. At this time he wrote a letter claiming that his amnesia had been entirely false, but observations of the British psychiatrists indicated that much of it had undoubtedly been real. (In fact such fallacious claims are typical of his personality, and he later made the same claims during the trial.) Just prior to the end of the war, this amnesia recurred and was at its height when he was flown to Nuremberg.

Rudolf Hess first came under my care on the evening of October 10, 1945. On his arrival at Nuremberg Jail he was met by the Commandant, Col. B. C. Andrus, who explained that prison regulations required the removal of all personal possessions. Hess objected violently, fuming that he was a prisoner of war and a ranking Nazi officer. He demanded that all his personal possessions be placed with him in his cell.

Colonel Andrus patiently re-explained the rules, and Hess finally agreed to relinquish everything except a number of small parcels. He insisted that these contained material for his defense, including drugs and food which he had brought from England for chemical analysis by an impartial chemist. He offered to permit a guard to remain in his cell twenty-four hours a day, provided these items could be left with him.

In the end Colonel Andrus impressed on him that his rights and privileges were no different from those of any other German prisoner and that his precious parcels would be sealed and locked up in the presence of witnesses. Hess accepted this ultimatum and was escorted to the cell which was to be his home for more than a year.

On arrival at the jail, Hess was, physically, in good shape, but thin. He was dressed in his Luftwaffe uniform, though without insignia. However, his heel-clicking stiffness and somewhat incongruous flying boots—high and black, thickly lined, and made of soft leather with two zippers on each—lent him a military bearing that no array of insignia could have given.

Psychiatrically, he was alert and responsive. His approach was reserved and his general attitude formal, but he gave the impression of making a real attempt at cooperation. His stream of thought was curtailed as a result of his amnesia, the majority of his responses being, “I do not know,” or “I cannot remember.” He claimed to be unable to remember his birth date, birthplace, date of leaving Germany, or any fact or detail whatsoever of his early life.

The next morning when I examined him again, he claimed he could not remember anything that had taken place during his imprisonment in England, and only vaguely remembered the plane trip to Nuremberg across the Channel. He could remember very little of the details of his admission to the prison, but did recall his parcels, and again asked for assurance that they were in a safe place where they could not be tampered with.

At this time Hess’s mood was somewhat depressed, but he showed generally normal reactions. In every way, except for memory, he seemed quite competent and showed no abnormal projections of any type. He continued to be observed daily and was given special examination, including the Rorschach Ink Blot Test. I explained to him the nature of this test—that it was designed to give me an idea of how his mind functioned, without, however, involving the memory.

This test is generally known to psychiatrists and psychologists and is the most useful single technique in a mental examination. It was invented in 1921 by Herman Rorschach, a Swiss psychiatrist, and gained popularity in the United States around 1938. During the war it was extensively used in the armed forces, and I relied heavily upon it in conducting my examinations of the major war criminals. Briefly, it consists of ten cards, on each of which is a reproduction of an enlarged ink blot. Five of the blots are black and white, two are black and red, and three are in assorted colors. Each subject is always shown the same blots in the same order. Then from his reactions—that is, from his description of what each blot may seem to him to be—a complete picture of his personality can be deduced. The test works in a manner analogous to the word association tests, except here the stimuli are meaningless—they actually are ink blots. Consequently, the subject who sees something in the blot must see it because he projects it from himself onto the blot. This is why this method is called a projective technique. The test really represents a small example of the subject’s behavioral reaction when faced with new and meaningless stimuli. During the test, he can do pretty much as he likes, take as long as he wants, turn the cards around, and give as many responses to any of the blots as he desires. The examiner is not so much interested in what he sees as in his behavior during the test, and particularly in how he sees each response. That is why this technique is so useful with people like Hess. Hess concentrated on what to say in order to confuse the psychiatrist, whereas I was mainly interested in how he used the cards.

Empirically, after giving many tests and studying the results of countless thousands of tests published in the professional literature, an examiner can tell a tremendous amount about a person by using the results of this technique. A skilled Rorschach worker can, for example, determine an intelligence level in an individual by checking the accuracy of the responses as to form and quality—that is, how well the responses are seen. Well organized, whole responses (where the whole blot is used), and good human movement responses (where the ink blots or parts of them are seen as humans in action) also indicate high intellect. Hess showed only slightly better than average movement responses, but his form accuracy was good. An I.Q. of between 115 and 120 was disclosed by the Rorschach and confirmed by a straight intelligence test given by the prison psychologist.

In addition to intelligence, the Rorschach responses reveal certain personality patterns—introversion and extroversion, rigidity, preoccupation with tiny details of life in contrast to a more general outlook, etc. It also reveals morbid trends, and with it, pathological traits of every type can be distinguished.

For example, in the second card Hess saw “two men talking about a crime, blood is on their minds.” This response is not exactly rare, but Hess was unable to interpret properly certain details of the card; he became preoccupied with the “bloody thoughts.” This sort of response represents a projection of his own thoughts into the ink-blot figures and tells us that in spite of his alleged amnesia he still carries “bloody memories.” He later admitted the accuracy of this reasoning.

Certain bizarre responses, such as a “cross-section of a fountain” in the ninth card, demonstrate inner anxiety and tension as well as a tendency to deviate from the usual in his everyday thinking.

Hess was quite cooperative in this test situation, partly from curiosity and partly because he felt he could control his responses, not knowing how revealing even the most banal answer could be. He spoke excellent English, but an interpreter was available in case of need.

Seated side by side on his cot (Hess in the center, and I and my interpreter on either side of him), we “ran” a very careful Rorschach, recording his every remark. From it, and from the results of the intelligence tests and personal observations, I diagnosed Hess as suffering from a true psychoneurosis, primarily of the hysterical type, engrafted on a basic paranoid and schizoid personality, with an amnesia, partly genuine and partly feigned.

In less technical terms, Rudolf Hess was an introverted, shy, withdrawn personality who, suspicious of everything about him, projected upon his environment concepts developing within himself. The paranoid element was emphasized in his suspiciousness, his desire to have everything just so his Rorschach responses, however, were not sufficiently de viate to indicate a really active paranoid process at the time but did indicate the possibility of a psychotic episode in the past and the likelihood of such development in the future

On October 16, 1945, I forwarded a summary of his psy chiatric status to Justice Robert Jackson, the American prosecutor. My report summed up all my findings and pointed out that some of Hess’s amnesia was probably genuine and some of it was obvious malingering. It also suggested that contact with his confreres would result in improvemen of his condition.

In this report to Justice Jackson, I requested permission to try to break Hess’s amnesia by the use of hypnosi reinforced by intravenous sedatives such as sodium amyta or pentothal. These drugs, given in small doses, put the subject in an hypnoidal state, assisting the physician in his direct suggestion. I have never had a failure in their use, no any but a beneficial result in many hundreds of cases. It i true, however, that in extremely rare instances people ar sensitive to these drugs and the injections may prove dan gerous. If proper precautions are taken there is really no risk, and the technique is nowhere near as hazardous a crossing a busy street intersection.

Justice Jackson, although he stated he would advise this treatment for a case of amnesia in his own family, felt that in Hess’s instance, any therapy involving the remotest chance of danger would be unwise. If anything happened to Hess, if he caught cold or stumbled and broke his neck two weeks later, it would probably have been attributed to the treatment. I talked to Hess himself at great length about the technique. He was at first willing to try it, stating that he was sure it would fail. When I told him that it always worked, he rapidly changed his mind. He also refused to be hypnotized, and in fact refused any type of treatment. For a long time he even objected to our taking blood for a Wassermann test, but on this count we were sustained by the higher authorities.

Since I was not permitted to treat Hess’s amnesia, I requested consultants to check my findings. Three Russian, a French, three English and three American psychiatrists were assigned to the task. Their findings confirmed my own. All agreed that Hess’s basic personality patterns were hysterical and paranoid. They also agreed that his amnesia, if maintained, would be a hindrance to his defense. Hess’s action on the stand on November 30, 1945, when he made his famous statement—“My memory is again in order. The reason why I simulated loss of memory was tactical”—was a typical dramatic, hysterical gesture which confirmed my opinions and those of the consulting psychiatrists.

This refusal to admit that anything has gone wrong with one’s mind is very common. Frequently people who have been insane, on recovery will state that all their symptoms had been mere pretense. This mechanism protects their ego. It permitted Hess to scoff at the idea that he, the deputy of the Fuehrer, could ever have lost his mind.

I went to see Hess in his cell immediately after his performance in court and asked him why he had done it. He was quite unaware that he had upset his attorney far more than ours. All he could think of was the show he had put on. In fact, he was quite like an actor after a first night.

“How did I do? Good, wasn’t I?” he asked, adding, “I really surprised everybody, don’t you think?” I shook my head and said I didn’t think “everybody.”

Hess stopped for a moment his excited pacing. “Then I didn’t fool you by pretending amnesia? I was afraid you had caught on. You spent so much time with me.”

I asked Hess if he remembered some movies that had been shown earlier of the top Nazis at the peak of their glory. At the time he claimed he could not recognize the men, even himself, in the newsreel.

Now he said: “Yes, I remember. I remembered when the pictures were shown. I thought then that you knew I was pretending. All the time you looked only at my hands. It made me very nervous to know you had learned my secret.”

I had not, of course, learned his “secret” in quite the way he thought. I knew only that he remembered more than he admitted. I had stared at his hands, however, in a deliberate effort to make him crack.

While he had had considerable practice in keeping a straight face, he still became nervous when shown old, familiar scenes. This tension was manifested by a tightening of his hands, readily visible to anyone looking for this symptom. He certainly recognized some of the scenes shown in that picture, although his denial was complete. He realized his inner tension and perhaps recognized its manifestation in the tightening of his fingers. After the picture, he tried to avoid me and kept our conversation to a minimum.

Of course, even after his dramatic disclaimer, Hess still had some amnesia. His mind never did entirely clear, though his memory did improve. In fact, within two weeks of the denouncement in court, there was a marked improvement which Hess himself noted and commented on to me.

From that time forward it became possible to trace the development of his amnesia. In England, during the period of intensive interrogation, Hess had discovered that when in answer to any question he said, “I don’t know,” the British would keep returning to it and hammering away at that particular query. But if he said, “I don’t remember,” the intelligence men seemed inclined to drop the question. Da after day and month after month, he was questioned s interminably, and so often replied, “I don’t remember,” that finally, large sections of his life simply slipped below the threshold of memory. In the end, he was a genuine victim of an induced, even rationalized, amnesia state.

Hess eventually confessed that much of his amnesia had been real and that his boast in court had been false. He even took pride, in time, in reporting the progress of his “cure.” But, though his mind was improving, he once assured me, it was “still weak and my brain tires easily.” This admission was interesting primarily because such a conviction is a typical symptom of the hysteria which is basic for the Hess diagnosis.

If final proof is needed that Hess’s hoax claim was phony it lies in the fact that the “tactical” advantage he claimed have gained—time and opportunity to prepare his defense—simply was not true. At no time did the amnesia favor his defense. In fact, it handicapped his lawyer. His hysterical structure is best revealed in the fact that he chose to thrust himself into the limelight by rejecting his amnesia, fatal as such a step might become, instead of attempting to escape by continued pretense. Such reactions are common among hysterics and are precisely what the psychiatrists expected to happen in his case as the trial progressed.

Also while in prison Hess manifested vague paranoid symptoms, at various times suspecting that his food had been poisoned. These were the same sort of symptoms manifested in England, and I could only conclude that Rudolf Hess, while not actually insane during the months he was under my eye, was certainly a potential candidate for an asylum. Diagrammatically, if one considers the street as sanity and the sidewalk as insanity, then Hess spent the greater part of his time on the curb.

Hess might be called a self-perpetuated hysteric. That is, he maintained his hysterical symptoms in good working order by refusing all types of therapy. It would have been comparatively easy to relieve him of his symptoms if he could have been persuaded to cooperate. But he preferred to suffer, usually selecting periods for the suffering when he was certain of the largest possible audience.

The attention his displays earned gratified his ego, but his colleagues were disgusted with his behavior. Goering in particular was upset, partly because Hess had completely fooled him with his pseudo-amnesia and partly because Goering wanted to preserve the fiction that the Nazi Party was made up of strong men. Not that he ever considered Hess strong. On the contrary, he told me that he had always considered Hess too weak even to be the ideal deputy.

In this connection, Goering one day told me a revealing anecdote. Hitler, anticipating his own death, early in the war publicly named Goering as his successor and Hess to succeed Goering in the event of the latter’s death. “When Hitler told me of it,” said Goering, “I was pleased for myself, though it was only what I expected. But I was furious that Hitler should name that nincompoop Hess to be my successor. I told Hitler so, too, and made a big fuss.”

Goering was sitting on his cot as he told the story. Now he placed his big hands on his knees and leaned forward. “Do you know what Hitler said? He said, ‘Now Hermann, be sensible. Rudolf has always been loyal, a hard worker. I must reward him, so I give him this public recognition. But, Hermann, when you become Fuehrer of the Reichpoof! You can throw Hess out and appoint your own successor.’” And as he explained to me the inner politics of the Party, Goering’s eyes gleamed with admiration for Hitler’s grasp of the fuehrer principle and his casual genius for handling men.

As the trial progressed, Hess became more and more disturbed; transitory amnesic episodes and an increased paranoid reaction—suspicion of everyone, fear of poisoning, and so on—were growing proof of his worry. In the face of the accumulated evidence—all of it testifying to the viciousness of his associates—he sought refuge in recurrent amnesia, and finally became so disordered that he was unable to take the stand in his own defense. As a result, he was considered insane.

Here the Tribunal indicated its good judgment. Death sentences for insane persons are not a part of civilized, democratic law; so the Tribunal compromised by a sentence which will place him behind walls for life.

From the psychiatric point of view, he was definitely a deviate from normal. He was emotionally juvenile, as evidenced by his love of uniforms and spectacles and as emphasized by his flight to England. He was the only prisoner who failed to recognize the reality of his situation; instead he firmly maintained his importance as the Fuehrer’s deputy, refusing to admit the total defeat of Nazism or to abandon the idea that he was not an outstanding patriot.

These, then, are the distinctive aspects of Hess’s personality: the paranoid and childish individual, with gross hysterical manifestations, who had always failed in whatever he attempted and who failed in the most spectacular effort of his life.

Later, as he realizes that he will not hang, he may relax and appear to recover. Such response will, however, be only superficial; and Hess will continue to live always in the borderlands of insanity.

Chapter Four: Alfred Rosenberg

ALFRED ROSENBERG, THE NAZI PARTY PHILOSOPHER, was a tall, slender, flaccid, womanish creature whose appearance belied his fanaticism and cruelty. His conversation, however, did not. He would willingly begin a discussion on any subject under the sun, but no matter from what starting point he began, within five minutes he would be rolling off his tongue the phrases he had worn smooth and round in constant discussion of his own theories of blood and race. Whether one began talking about history, horticulture, or a paratrooper’s high boots, Rosenberg’s quick switch to the subject of blood and race was so certain that one could almost plot it mathematically. Rosenberg gave a remarkable demonstration of the single-track mind in action; and he proved a sore trial to the men who questioned him.

To me, Rosenberg was of constant interest. He was the first, as it were, ordained and official philosopher I had ever known in the flesh, and I must confess that my concept of a philosopher had not prepared me for him. My studies forced me to conclude that Rosenberg was a relatively dull and a frightfully confused man. A large part of his confusion lay in the fact that he was unaware that he could not think straight, and he was further befuddled by the fact that he never realized his intellectual limitations.

Many persons were surprised by the result of our intelligence tests which showed, beyond doubt, that the famous Nazi philosopher was of low—average intelligence. The fiction of his brilliance, I am sure, is the sort of thing which literary German, particularly the literary efforts of German scholars, encourages. So involved and obscure are German philosophical works traditionally, that when Rosenberg wrote a book which no one could make sense of, instead of admitting that they couldn’t understand it, they accepted it as gospel.

But Rosenberg is not a man lightly to be laughed off. As a result of his close contact with Adolf Hitler, his influence on the Nazi Party was probably greater than that of any other single subordinate.

Rosenberg was another Ausländer, a factor of importance in his development. His father was a German executive in a trading company in Revel, Russia, and his mother is recorded as Latvian. He attended school in Germany, and there, as well as at home, he acquired the strong nationalistic feeling common to German families living abroad. In his teens he studied architecture and engineering in Riga, and when the war broke out in 1914, he went to Moscow. There, in 1918, he received his diploma in architecture.

In Moscow he witnessed the Bolshevist Revolution and developed an intense suspicion and hatred of everything Bolshevistic and Russian. Identifying these two hates, he soon coalesced with them all Judaism, constructing for himself a triune hatred to balance his strong affection for the unknown Fatherland. This violent, anti-Semitic, anti-Russian, anti-Bolshevistic attitude was basic in his contribution to Mein Kampf. Naturally, his zeal served to strengthen the same attitudes in Hitler and other Nazis.

Rosenberg returned to Revel in 1918 and undertook an assignment propagandizing against the Reds who had not yet won over Esthonia. However, the Revolution was on the march and, as Red forces approached Esthonia, Rosenberg fled to Germany. In Munich he resumed writing and speaking against Bolshevism and shortly became associated with the National Socialist Party through the influence of Dietrich Eckhardt, the Nazi poet. Rosenberg and Eckhardt were thus among the earliest members of the Party; Hitler did not attend a meeting of the group until almost a year later, near the end of 1919.

Thereafter Rosenberg was at all times one of Hitler’s most constant collaborators. He participated in the 1923 putsch, but was overlooked in the crowd and suffered neither injury nor arrest. When the Nazi Party was recognized officially, Rosenberg was one of three active chiefs of the underground organization. He visited Landsberg Prison virtually every day during Hitler’s term, and there is no doubt that his racial and nationalistic philosophies were written into Mein Kampf at that time.

As the Nazi Party developed, Rosenberg became editor of the newspaper Voelkischer Beobachter, and through it and numerous other publications continued to inject into the Party his theories of the virtues of German blood, the sin of mixing races, the threat to culture embodied in Russian-Jewish Communism. He became established as the Party philosopher and, in 1929, was placed in charge of one branch of propaganda.

In the thirties, Rosenberg made an attempt to take over the Foreign Ministry. However, after a series of unhappy experiences in London—one of his mistakes was placing a swastika wreath on the tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Westminster Abbey—he was recalled, and his diplomatic apprenticeship ended. Ribbentrop eventually replaced him.

Rosenberg retired into the impregnable position of philosopher to the Party and was given a title which, with typical German ebullience, ran as follows: “Deputy to the Fuehrer of the National Socialist Party for the Entire Spiritual and Ideological Training and Education of the National Socialist Party.” His functions were even vaguer than his title, but under its authority Rosenberg had ample opportunity to implement his anti-Semitic, anti-Communistic beliefs.

It was during this “spiritual and ideological training and education” period that he supervised the rewriting of German history. It seems scarcely necessary to point out that the Rosenberg histories, though often contrary to the facts known to the rest of the world, tended to place the Third Reich in the best possible light.

At this time also, Rosenberg wangled, or was rewarded by, appointments to numerous organizations dealing with culture. We find him interested in the physicians’ league, the veterans’ organization, the German Labor Front, adult education programs, the development of German pagan concepts, the Strength-Through-Joy organizations, the schools, universities, and teachers’ training programs. In addition, he undertook the control of literature, the development of German folk studies, and the establishment of an academy for ideological training. He continued as editor of several journals, made countless speeches, and published a large number of pamphlets and books.

This rash of activity in so many fields inevitably resulted in arousing considerable antagonism against Rosenberg within the Party, for he was an outspoken, contentious individual. He fought with nearly everyone and every group in Germany at some time or other. With all universal religions, Catholic and Protestant as well as Jewish, he was in constant warfare.

During this period of intense activity, Rosenberg republished at frequent intervals the Protocols of Zion, which he had first published in 1920. Some writers have maintained stoutly that Rosenberg first discovered the Protocols in Russia. Konrad Heiden’s book, Der Fuehrer, gives a very circumstantial account of Rosenberg’s first acquaintance with the Protocols—one which only Rosenberg could have told. When I cited this book to him, Rosenberg flew into a fury and called Heiden several sorts of a liar, insisting that, though he had heard of them in Russia, he had first seen Protocols in Munich in 1919. He felt at once that they were of “great value in revealing the International Jewish Plot, and I determined to keep them before the public.”

For his multiple activities, Rosenberg was amply rewarded by his old friend, Adolf Hitler. Hitler singled him out for special honor in 1937 by giving him the first German National Art and Science Award at Nuremberg. This was the Nazi equivalent of a Nobel Prize which, it will be recalled, the Nazis had forbidden Germans to accept after the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded in 1936 to Carl von Ossietzky, a pacifist who was at the time a prisoner in a Nazi concentration camp.

Hitler’s backing of Rosenberg continued virtually to the end, in spite of the conviction on the part of other top Nazis that his activities should be confined to purely intellectual ruminations and that he should never be given executive authority.

Shortly after the war began, Rosenberg was put in charge of education. True to form, he began expanding his activities and, in order to obtain educational material, developed a staff which moved into France and confiscated libraries, art collections, and other cultural treasures for the enrichment of the archives of the Nazi Party. These collections, naturally, were made without bothering to get the consent of, or offer compensation to, the owners.

Having stripped France and the Lowlands, Rosenberg in 1941 received his most important executive assignment—one which he was wholly unfitted to fulfill. He was made Reichs-minister for the Eastern Occupied Territories. I suspect that Hitler may have acted partly from a desire to get Rosenberg out from underfoot and partly because, having been born in Esthonia, Rosenberg was assumed to be familiar with the people and problems of western Russia.

As an administrator, Rosenberg failed miserably; as an exterminator, he succeeded almost beyond belief. Here at last was his opportunity to exercise his triple hatred to the extreme. In captured documents I found evidence that he had literally millions of the inhabitants of the area either deported or exterminated. There is little doubt that conquered Russia territories suffered more under Rosenberg than any other area under Nazi domination. Such looting and destruction has never elsewhere been seen.

Had it not been for the record, it would have been difficult to imagine the bumbling prisoner I knew as a mass murderer. He seemed, outwardly, a fairly “normal” man of scholarly mien and habits, in good physical health except for a chronic but not severe rheumatism. He seldom spoke of his family, though he had been married twice. He was divorced from his first wife in 1923 when she, suffering from a lung disease, left him to go to Switzerland to seek a cure. He remarried in 1925 and had one living daughter.

Ordinarily Rosenberg’s face wore a somewhat mild and somnolent expression; but it came awake, alive, and flushed with excitement, when he discussed his theories of his major work, Myth of the Twentieth Century. This opus was the foundation of his prestige, a basic book of the Nazi Party, and the authority on all racial problems. In it he had delineated his theories, but in unbelievably obscure and hazy fashion.

Baldur von Schirach, the youth leader, once swore to me that no one in the Party had ever really read the book. He himself had made a survey of his own subordinates and found that, while every youth leader possessed a copy, not a single one had ever been able to wade through the labyrinth of deviation and free association that characterizes all Rosenberg’s writings. Von Schirach went even further and, with sarcastic humor, commented that since every Nazi had to buy a copy of the book, “Rosenberg should go down in history as the man who sold more copies of a book no one ever read than any other author.”

Though I actually read the book and discussed it with him for hours on end, it took me a tremendously long time to piece together the basic philosophy which had guided his life. Eventually, much to his delight, I succeeded in putting it into fairly precise, if not simple, form.

First of all, Rosenberg believed that all races possess specific and differing physical and mental characteristics. Europeans he divided into five general racial types. He admitted that these five races have so intermingled that it is impossible to separate them at present and that, in consequence, European nations are not true races but are simply nationalistic groups. However, the Nordic racial group, found primarily in Germany, in the Scandinavian countries, and in England, is the purest; and the German (Rosenberg) idea was to remove the impurities in order to re-establish its status as a truly pure race.

On the other hand, Rosenberg maintained that the Jewish people was not a true race, but a nation composed primarily of Oriental (or Arabic) and Armenian types. Because of its religion, however, this nation had not intermingled with others and so, Rosenberg solemnly concluded, must be considered not only a distinct nation but a distinct race. That is Rosenbergian simplicity!

Rosenberg further contended, basing his assumptions primarily on Madison Grant’s The Fall of a Great Race, that the Greek nation deteriorated when it commenced to intermarry with other Mediterranean peoples. Consequently, he preached, the problem in Germany was essentially simple. All the Germans had to do to purify their Nordic race was to prohibit intermarriage with the Oriental-Jewish race and, in a period of time, their blood would again become pure and non-mixed. That is, after mixture was interdicted, the already mixed Nordic blood would slough out its “impurities” and automatically “purify” itself. More simplicity.

Actually Rosenberg’s ideas on German blood were suggested by Darré who in his work Blood and Soil related the basic German blood of the peasant to the soil which he worked. Darré visualized a cycle in which the peasant in life worked the soil into which, on his death, he would be reconverted. Meanwhile his ancestors’ blood was his daily food—in the fodder he fed his meat animals and in the crops which he consumed directly. So German blood, through fertilization of German soil by German bodies, goes from German generation to generation.

Rosenberg, ebulliently fuzzy, said it thus in his major work:

“New faith is arising today. The Myth of the Blood, the faith to defend with the blood the divine essence of man; the faith embodied in clearest knowledge that the Nordic blood represents that mysterium which has replaced and overcome the old sacraments.”

I was more than casually interested as a psychiatrist to find in Rosenberg an individual who had developed a system of thought differing greatly from known fact, who absolutely refused to amend his theories, and who, moreover, firmly believed in the magic of the words in which he had expressed them.

This last characteristic was typically demonstrated one day when I was struggling with the Myth. I was having read back to him various chapters of the book which I had asked him to explain. My interpreter on this occasion was an American officer who had been born in Luxemburg and who had previously interrogated Rosenberg for Army Intelligence. Rosenberg, therefore, knew him and also knew that he was a Roman Catholic.

Consequently, when he started to put my questions to Rosenberg, the philosopher reached over, took the open book from his hands and closed it firmly. I asked him why he had done that, and he very seriously told me that any other interpreter would do but that he did not wish this particular interpreter to have anything to do with his book.

Both my assistant and I were somewhat startled and pressed him for a full explanation. Rosenberg rather loftily replied: “This young officer is working for his country. He is a good soldier and also a good Catholic, and I do not wish to change his way of life. If he were ever to read this book, he would renounce the Church immediately.”

This incident, remember, occurred while Rosenberg was on trial for his life for implementing the ideas in his book! Few authors, “philosophers” or not, are blessed with so firm and fixed a belief in the power of their writings.

Apparently Rosenberg felt that, as a psychiatrist, I could not be further corrupted, for he was quite free in giving me the benefit of his racial wisdom. He was particularly emphatic in pointing out that, as an American, I should be made aware of the dangers of minority groups in this country. It was Rosenberg’s conviction that the only thing wrong with the Nazi Party was that it had developed fifty years too soon, and he prophesied that only a few decades would pass until “the rest of the world will be able to understand us.”

He assured me that the African and Syrian-Oriental races in themselves are respectable; but that only evil and ill fortune come of mixing them with “whites.” He was certain that in America our major problems lie with the Negro race, the Oriental race (on the West Coast), and the “European Oriental” or Jewish race. “A wise politician would have left the Negroes in the country and would have allowed them to execute their own authority in manners and customs,” he warned me. This typically hazy verbalism was part of a harangue on the danger of mixing races in cities where they are apt to intermarry.