Translated by Will Schutt and Alberto Prunetti.

Edited by Alice Parman.

Dedication: To Gioia, my 6-year-old daughter whose profound wisdom has taught me to understand the unspoken language of tenderness, to rediscover the wonders of the colors of flowers and to see perfectly with my eyes closed. To she who has also made me understand what strength lies beneath our natural longing for independence. And to think that we adults force children to become like us instead of learning from them!

Enrico Manicardi

Free From Civilization

Notes Toward a Radical Critique of Civilization’s Foundations: Domination, Culture, Fear, Economics, Technology

Prologue: What is civilization?

Part 1: The Mentality of Domination (A critique of domination)

2. Alienation, Reification, Domestication

3. Order or Harmony: Egocentric mentality or egocentric perspectives?

5. The Use and Consumption of Animals

6. Social Stratification and the End of Equality among Humans

7. Male Supremacy and Patriarchal Society

8. Human Slavery and Productive Work

9. Socialization and Robbed Identities

1. Conscious Domination, Unconscious Ideology: knowledge as power

2. The Rebellion Against the Rule of Science

3. Will Civilization Eventually Manage to Put the Stars in Line?

Part 2: The Primacy of Symbolic Culture (A critique of culture)

III. Emancipation from Abstract Knowledge

1. Culture as Programmatic Separation and Isolation

2. Culture as an Ideology of Civilization

1. The Symbolic Foundations of Social Control: ritual, art, myth, religions

2. Take Up Art and Place the World Apart: Art as a Substitute Effect

3. In the Shadow of Babel: the birth of language and its meaning

4. Civilization as graphocentric society

5. Mathematics is Not an Opinion: the Concept of “Numbers” and its Absolutizing Valence

6. From Numerical Absolutism to the Absolutism of Reason: Abstract Analytic Thought as Dogma

7. Chronocracy: The Tyranny of Time in the Civilized World

Part 3: The Doctrine of Fear (A critique of fear)

V. Fear as the Psychological Foundation of Civilization

1. Fear as Fear, Fear as Terror

1. The Politics of Terror, Politics as Terror

VII. Ethics Of Fear, Ethics Of Unhappiness

1. Fear of Death, Fear of Life: Unhappiness in Civil Society

2. Fear, Aggression, Violence: Birth of War, Disavowal of War

Part 4: The Power of the Economy (A critique of economics)

VIII. Economics And Utilitarian Logic

1. What is Economics? Economics is Thievery!

2. The Lie of Homo Economicus and the Give and Take Attitude

IX. From Gift Exchange To Economic Rule

1. The Genesis of the Economic Model: From Giving Freely to Demanding Reward

4. Poverty and Civilization: Money as the Architect of Poverty

7. Assault of Production, Resistance to Development

X. Mercantilism: Dirty Business, Slavish System

Part 5: The Technological Imperative (A critique of technology)

XI Technological Expropriation

2. Tools and Technology: The Psychological Approach to Technology

1. Against So-Called Neutrality in Technology

2. Technicist Ethics, Technical Propaganda: Technology as a Tool for Power

3. Technology and Totalitarianism

4. Cold Comfort: A Critique of Modern Comforts

5. Necrophilia and Technology: the Dead World of Civilization

Preface

Enrico Manicardi has given us a book of great importance. It is, to my knowledge, the most comprehensive treatment of civilization critique in any language. In Italy, Liberi Dalla Civilta joins the work of such scholars and writers as Stefano Boni and Alberto Prunetti. This book is an in-depth introduction to a new movement, and shows why a growing number of people are calling civilization itself into question.

A further strength, which I find quite moving, is the voice and tone Enrico has used to write this book. Starting with his introduction, he expresses what it means to be living within civilization, and how it feels. This reminds me of the best of Derrick Jensen’s work. I am profoundly struck by this combination of passion and analysis, and I predict that many readers will be equally moved.

As the crisis deepens, spreading into every part of our planet, it replicates the anti-life trajectory of civilization’s domesticating, controlling, smothering force. At the same time, this unfolding reality is awakening a desire for fundamental change, for a paradigm shift. Faced with intolerable, unhealthy threats, we open up to new ways of thinking. These new thoughts must be profound and creative enough to match the dire forces now overtaking us. I am encouraged by signs of such new thinking and new approaches in many countries ––not recognized officially, but developing rapidly, and transcending both Right and Left.

Mass society, industrial life, the end of nature, the techno-culture… we can use various terms for this barren reality. It is all turning out badly. Very badly. We are here, and we need to be somewhere else. Free From Civilization is an invaluable guide. Thank you, Enrico!

John Zerzan

Introduction

Why write an essay that critiques civilization today, when civilization is presented everywhere as the only means of escape from a world that is drifting away? Why stigmatize, down to its foundations, the mix of values that distinguish civil life when these values are elevated on the basis of high-sounding propaganda as promises of future welfare and happiness? It would be too easy to answer that we cannot believe such promises anymore, that they are mere propaganda; that a “Better Future” has been pompously heralded for a long time without any celebration following the many announcements. But the problem is certainly more complex.

If we look closely at the conditions of the modern world, we see not only a medley of broken promises of happiness, but also a series of perfectly kept promises of unhappiness. When we are told that in order to live better someone else must be worse off, when we are asked to be patient a while longer, to tighten our belts, grit our teeth and accept those sacrifices that will make the sun shine again, we are facing just those sorts of kept promises. Which is exactly what happens when we are asked to work even more, hurry up even more, consume everything and everybody in order to sustain Economy, Progress, Development, Democracy, etc.

In the world there are no absolutely negative or positive situations. Even something that makes us extremely happy can cause some suffering (romantic love is perhaps the most illustrative example); on the other hand, what we consider negative can help us grow up and may not be totally unfavorable. Like any human condition, civilization is distinguished by these mixed features. The point is not to judge it as totally disadvantageous (or absolutely free of inconveniences), but to try and understand it in terms of its entrenched patterns, principles, developments and effects, so as to look at civilization from a vantage point that allows us to establish if it can still be worthwhile to follow its path or if it is better to change our route. There is a price we pay everyday to safeguard civilization and to permit it to spread further: this price should be the stake of the game revolving around our willingness to accept all this.

Here is a simple example: all of us can acknowledge that a cell phone is a very useful tool. It undoubtedly is, but at what price? We just don’t have to think about the damage it causes to our health due to the noxious waves it emits (by using it, by not using it and even when it is on stand-by). We just don’t have to think about the damage it inflicts on the environment—by spreading cell phone towers all over the Earth’s landscape; by favoring a massive production of the super-polluting materials it is made of (plastic, paints, batteries); by becoming toxic waste when it is not used anymore. We also don’t have to think about the relational isolation where it imprisons us all, making face-to-face communication less and less likely as well as, for many young people, the ability to express their opinions (and even their feelings) in person. And we don’t have to think about the financial interests of the entire cell phone industry, about the financial speculation it encourages, about the environmental and human exploitation it brings about (some of the materials cell phones are made of are unearthed from deep mines where still today many enslaved people work and die). Finally, we don’t have to think about the technological and military development programs that are nourished by the mobile phone phenomenon, making social control more and more invasive and wars even crueler. In short, we don’t have to think about all this (and much, much more) if our cell phone is to appear only as a very useful tool.

Civilization—just like cell phones—has a really high price, and even if this price is usually carefully concealed and underestimated, it is there nevertheless. Acknowledging this is a first important step towards the evaluation of its acceptibility.

In this civilized world we have a bad life, and it is getting even worse. Not just because of hunger, or of the excruciating death of children exterminated by disease, famine or lack of drinking water. Our life is bad even in the opulent regions of this planet, in what is generally presented as the land of plenty. Multiplying forms of addiction: tobacco addiction and alcoholism are spreading among the young, together with any kind of more or less legal psychotropic drugs, medications, video games, sex industry, and gambling; the spreading of nervous diseases—anorexia, bulimia, panic attacks, chronic fatigue, sleep disorders; the various obsessive compulsions—to run faster, buy everything, collect anything, to hygienize and sanitize every single item; the exponential increase in violent episodes, from bullying to serial killers; all tell us that where the “national welfare state” has been officially proclaimed, civilization spares no one. Irreparably articulated in the routine on which our dismal everyday life is based, accompanied by a continuous distress and by the isolation that derives from a growing object- and service-mediated existence, this sense of inner emptiness becomes more urgent and looming and submerges us all—whether dissidents, faithful supporters of civilization, or opinionless people. The feeling of stress connected with the agonizing industriousness in which we try to drown our pain, and the boredom that overwhelms us as soon as we come out of these wearing cycles of hyperactivity convey an unmistakable truth: when life is domesticated and subdued to the System, its quality does not improve—whatever the GDP indexes, institutional statistics or parliamentary reports may tell us. More and more vehement and contrasting fundamentalisms, and the rise in self-destructive acts in the developed world, seal this bitter statement in a most dramatic way.

However, humans are not the only subjects who suffer because of the civilized world. The whole planet is groaning with us. Floods, downpours, typhoons, tropical storms, more and more violent hailstorms, acid rain, nano-particles, a growing number of endangered species, global warming, drought, desertification, deforestation, and overbuilding are turning the Earth into a dead zone—a toxic, inhospitable wasteland whose existence is doomed by the same devastating trajectory guiding the attack on human life.

The price we pay for civilization to keep trampling on the planet’s—and its inhabitants’—destinies finds its ideal expression in our increasing “detachment” from life and from the sense of life. In the civilized world, the natural foundations of our existence—our genetic constitution, our multi-sensuousness, the free perception of reality, direct experiences, autonomy, sharing, sympathy, mutual help—are continuously attacked by a techno-mechanized, competitive and calculating universe that is making these aspects unknown even to ourselves—when they are not explicitly suppressed in a laboratory. In our world there are actually categories which we have learned to deem hugely important and that civilization has taught us to consider absolute and neutral. Authority and Bureaucracy, Science and Technology, Economics and Overpopulation, Property and Work, Education and the symbolic forms of culture (Art, Ritual, Myth, Religion, Language, Writing, Number, Time, Money, Law, Social Role) are not universal or unbiased loci. They are conceptual categories that were established together with civilization and have become untouchable. Starting to look critically at these categories means looking without too much awe at our way of living (and of thinking); it means trying to understand what constitutes the high price we are forced to pay for civilization to keep expanding. And it also means trying to trace the causes of the widespread malaise that none of the services marketed by civilization is able to “heal”.

Generally, when we try to investigate the causes of the current degradation, we tend to go back just a few decades or centuries at most: back to the rise of consumer society, of mass organization and of successful industrialization. All these phenomena have undoubtedly contributed to the current situation. But should we really stop at the beginning of the nineteenth century and at the date of birth of industrial capitalism to identify the sources of today’s crisis? The traditional antagonist movement’s answer to this question has always been positive. Personally, I think the opposite is true.

While it is a fact that the world’s commodification, an extraordinary consumerist mentality, and a celebration of absolute utilitarianism that turns everybody into downright speculators are all direct products of the capitalistic ideology (it was Adam Smith, the ideologist of modern capitalism, who promoted the crazy idea that if we follow our personal interest, we will indirectly favor everybody else), it is also true that the abolition introduction of this cynical ideology alone would not suffice to restore a free and satisfying lifestyle. After all, the mindset of domination was established much earlier than in the nineteenth century, just like authoritarianism, chauvinism, and patriarchal society. Economics already existed before the rise of the industrial society, exactly like politics, with its demagogic flatteries; social control, with its invasive teachings of forced cohesion; science, with its totalitarian warnings; and technology, based on exploitation of wildlife and the environment, and the source of pollution. To say nothing of war and slavery, invented long before capitalistic society.

If we want to try to go back to the roots of our current crisis, if we want to try to understand what is happening to our present world that is becoming hollower and more elusive by the day, we cannot simply consider the damage that was set in motion two hundred years ago; we need to go back much further. To what period exactly?

This discussion seems to raise very precise questions: has an age ever occurred when human beings lived in an utterly peaceful, playful, respectful way? Was there an age when people did not fight, dominate or exploit each other, when they did not confine themselves in hierarchically structured social organizations that regulated relationships according to a fixed and compulsory set of rules? Has an age ever occurred, when humanity could live basically free from forms of social control, from the logic of economic exchange and production, from rubrics of ideological efficiency, performance and power? Have we ever ascertained the existence of a time when men, women and children enjoyed a profound communion with nature, without any prospects of pollution or environmental consumption, and were immune from the condition of alienation in which our current existence is confined? Starting half a century ago, several studies have been carried out on this subject, offering surprisingly positive answers: according to them, the passage from a free and satisfying human life to an ever increasing regimentation into the values of the modern world coincides with the birth of civilization.

When discussing civilization, we first need to clear up a misunderstanding. Too often the term “civilization” is supposed to overlap with “humanity,” so that human beings are thought to have been civilized since they appeared on this planet. This is not true. Civilization was not born together with the human race. In fact, if we consider the history of the ancient past, civilization is a quite recent phenomenon. The famous American physiologist and bio-geographer Jared Diamond estimates that the human species split from the anthropomorphous apes approximately 7 million years ago; 3 million years ago humans assumed an erect posture, and around 2.5 million years ago they entered the so-called Paleolithic age and acquired all the abilities and skills (also at a mental and intellectual level) of a modern individual. However, civilization is commonly thought to have begun with the introduction of agriculture (at the beginning of the Neolithic age) and is dated back to just 10,000 years ago. Two and a half million years of human life against just ten thousand years of civilized life. If we use the example of monetary units, this difference is even more striking: two and a half million euros, ten thousand euros…

Actually, for a hundred and fifty thousand generations, our human ancestors lived in a non-civilized world, as nomadic gatherer-hunters. This means that they were individuals with no fixed abode, no possessive mentality or conquering obsessions, and they lived free from restrictions, immersed in a pristine nature and far from the overwhelming preoccupations of the developed world. They were not suffocated by bureaucracy, money or hierarchies because there were no centralized socio-political entities that had to be managed (be they kingdoms, nations, states, or empires); they formed small communities (bands) consisting of a few dozen people, that were profoundly co-operative and egalitarian and where anybody could express their personality, to the point of being free to leave the group at any moment.

Comparing the length of time in which the human race has existed with a 24 hour day, we have lived outside of civilization for over 99.6% of our lives—from midnight to 11.55 p.m.—and then submitted to civilization in the last five minutes of the day. But in these five minutes we have destroyed, devastated, jeopardized everything, until we endangered our own and the whole world’s existence.

In that long uncivilized past we can find many suggestions for our present. This is what this essay will try to do, through continuous reference to the origins of civilization and to our pre-Neolithic ancestors’ lives, considered especially through the experience of the communities of gatherer-hunters who still inhabit this planet—though besieged, contaminated, exterminated by the civilized world and always confined to the most impenetrable regions of the Earth. A very long uncivilized past has existed and its lively presence has been preserved up to the present day; an attentive gaze to the experiences of these indigenous people will not only be the leitmotif, but also a frequent reference of this work. This is not because such an investigation can be a an excuse to present a world view which must be necessarily projected towards a “return to the origins,” but because we can thus learn from the existence of our primitive ancestors and counter today’s degraded life experience with ideas and practices from an uncivilized life. The aim is the same as always: trying to enrich the analysis of our own time with any element which may be worth considering; not in order to idealize a certain past, but to try to make our present livable. This partly explains the reason why we will also find guidance in the wisdom of children, whenever possible. In the end, if what we want is an opportunity to live in a playful, free, responsible way, in an environmentally healthy and relationally vital world, then observing the experience of those who, in the past as well as in the present, can give us good advice can only be helpful.

Some will find this book too theoretical, aimless as regards practical action. If we look at things from the perspective dictated by our mentality, it seems clear that any introduction spirit of transformation must start from ideas in order to spread into our bodies and into our hearts. But in today’s society there is no freedom of thought. As Jerry Mander denounced, much earlier than Latouche, our lives are suffocated by an imagination that is completely colonized by the values of the dominant culture. So what we need to do first is try to free ourselves from this conditioning as much (and as long) as possible. Free from Civilization does not contain any magical recipes, instructions or precepts, decrees, or commandments. The libertarian pedagogist Marcello Bernardi believed that the solutions to our problems can never be found in someone else’s dogmatic prescriptions but only inside ourselves, and everybody needs to search, imagine and apply her own solutions. Other people’s opinions can at most serve as a foundation for the development of one’s own ideas; it is in this interactive dimension that this text is situated. The following argumentations will not aim therefore at gathering converts, but rather at raising doubts and questions, at spurring reflection. This essay, in short, will never try to imbue its readers with absolute truths, but rather to question the false claims on which the civilized world is based. If we don’t accept that civilization may be the problem of the world we live in, no current paradigm will be ever seriously questioned, and the process of destruction that started with the introduction of agriculture will keep expanding—progressively, unavoidably, relentlessly. The first revolution against civilization must therefore start from within ourselves, in the form of an openness to criticize the ideological foundations of this annihilating universe.

This essay is not meant as an accusation against someone in particular (against farmers or against the puppet-stars of this age of entertainment), but rather as a collection of critical considerations aimed at questioning the entire pervasive and creeping system we call civilization. This system has curbed us, turning us into addicts and leaving us at our own mercy, to the point that we, starting from myself, are now unable to honestly admit it.

The content of this volume is indeed the product of fingers ticking away at a keybord, documentary researches (also on the Internet), the usage of the grammar and syntactic structures of a language that was learned in a family, perfected at school and used in all the contexts where the author’s social and personal life unfolds. The author of this book has a working life as most other people; he uses a car, heals himself through medicine (a natural medicine whenever possible, but medicine nonetheless), composes and listens to music, and “loves” cinema. This author carries an ID card in his pocket as any other Italian citizen; he travels around the world by using trains, ferries and planes and shows his passport to the border authorities.

A critique of the world we live in must not find its legitimation in an unattainable absolute consistency, otherwise there could be no space for critiques. Each one of us has his own skeletons in the closet, as well as some weaknesses; each one of us is pushed into a corner by this generalizing universe, and we often do what we can instead of what we wish. Pure coherence does not exist in the civilized world, unless you absolutely and passively accept it; or perhaps not even then.

Nobody’s words, least of all mine, should be taken as unquestionable truth. Nobody, least of all me, can claim to act as humanity’s judge. No word in this book is meant to imply that someone can walk on water. But there is a way of thinking, feeling and acting that justifies and supports the set of principles on which this declining world rests, and another way that tries instead to understand what is wrong and to radically overcome every prejudice. The radical critique of the foundations of civilization contained in this volume is meant to be a further small contribution to everybody’s consciousness: to a consciousness of what we are and of what we might become. Here is, in short, a further small contribution for everybody’s minds, bodies and hearts, so that our thoughts, our feelings and our everyday actions (however small), really start to turn against the support of this unlivable world instead of favoring it.

Prologue: What is civilization?

Civilization leads to death.

Nikolai Berdyaev

What would we think if someone invited us to take part, as legitimate children, in a family’s life in which parents force their young offspring to live in inhuman conditions? What if parents forced them, for instance, to live in hardship, confined in crowded spaces with polluted air and the odor of noxious fumes? Or if they kept them from moving freely, forcing them—even during their childhood, and for their whole existence—to sacrifice their lives to activities that are more or less alien to their need to move, play, sustain themselves, and are always uselessly repetitive, exhausting, damaging, and stressful? What if these parents educated their children to accept these sacrifices as an effect of a setup that requires people to acquire a certain quantity of “participation tokens” as the only way to reach, as expected, an otherwise unattainable minimum survival condition—meaning: clothes, a shelter against bad weather, sunlight to feed our body cells, affection, care, daily nutrition? And what if even this costly survival license could be questioned by parents at any time, and at their sole discretion? And if one’s shelter could be seized overnight, if sunlight could be overwhelmed by artificial light, if affection and care were made inaccessible and denied, if daily meals were poisoned and those participation tokens could be confiscated or their conventional value could be eroded?

What would we then think if we learned that, in the face of these poor kids’ manifest distress, their parents tried to deceive them, pushing them to a passive acceptance of their fate? Or, in fact, if they preemptively acted to ensure a most effective suppression of any potential manifestation of this discontent, and accustomed their children to the use of narcotic and psychotropic agents to distract them from their pain, to avert their minds from their discomfort, to blur their analyzing skills, filling their tormented souls with the belief that this is how it has always been and that therefore this is how it will be forever?

Would we accept life in such a family?

The likeliest answer is: no. All of us, however compliant, would eventually judge this existence unacceptable and persecutory. Even if we were forced to consider it the most desirable (or the most common) existing condition in this world, it would still be what it is: a tremendous plot against life. In the face of this ferocious imperiousness, our body and our spirit would soon end up rebelling, perhaps letting out their suppressed suffering through a disease or an aggressive thrust (against ourselves or others).

With all the limits of this simplification, the metaphor of the “unconscious family” adequately describes the reality of the modern world—of the great and ever more globalized and standardized family that is embodied by today’s techno-industrial society dominating the Earth. This is the reality we live in now: this is civilization.

Of course, comparing human life with a family life where the parents’ (or the dominating elites’) responsibilities are formally separated from the children’s (or the governed people’s) responsibilities is quite a contrast with a vision of humans capable of autonomous control over their own existence. Yet such a distribution of tasks is not only the framework that sustains the institutions of the civilized world (which is, by default, based on delegation and representation), but also the main pillar of its structure. In the modern world, everything is organized so as to distinguish between those who do something professionally—from the management of private disputes to the care of souls, from education to information—and those who should simply use the relevant services while carefully adhering to their instructions—tax-payers, users, believers, clients, patients, voters, spectators... And while any substantial critique of this strict organizational scheme is scorned, everyone is formally accorded freedom to play this role game, so that this model can be officially approved. With the possibility that everyone will someday play a crucial role for someone (as parent, spouse, teacher, technician, artist, specialist, senior clerk or leading politician), the system assumes a democratizing appearance and is eventually perpetuated by those same people who have been induced to accept it with servile obedience. Naturally, this call to submissive approval does not favor harmonious social participation, let alone deep self-fulfillment. Sooner or later, every individual living in the domesticated world will end up suffering from it. Reaching the breaking point is only a matter of time. Nervous disorders, disease, violence, apathy, general dismay, the urge to command and to be commanded, to own and to be owned eventually reveal the heavy implications of this crisis.

The greater the impulse towards existential distress, the greater the force applied by civilization to preserve itself. Causing us to lose our bearings, giving us deceiving targets, channeling the best energies toward the consolidation of the status quo, deflecting any critical acknowledgment. And the more civilization pushes us off the track, the more insistently it refuses to recognize the symptoms of the discontent it forces upon us. As though it were possible to keep a bottomless boat afloat, we are all called on to a meticulous maintenance of its sides by filling up, with the most innovative artificial resins, every tiny crack and dent; which will not result at all in the boat floating, of course. Since the boat is deprived of its basic structure, water will keep flowing into it, and the unwillingness to look at the original causes of this disaster explains why we keep looking somewhere else for the causes of this wreckage. The problem does not lie, someone has started theorizing, in the construction we designed—a bottomless boat—but in a mischievous and uncontrollable sea. So it is on this element that we should focus our efforts, in order to subdue it even more to our techniques, inventions, and power. According to this view, the existential anxiety that devours us is not due to the unbearable sadness and bottomlessness of the world that we have superimposed on a natural and free existence, but rather to that same spontaneous existence, which has to learn to bend even more to the requirements of the social system. In this perspective, it was easy to turn the crisis of our time not into a symptom of an underlying problem (civilization), but into an independent degenerative effect that must therefore be further suppressed.

In the world we live in, every manifestation of suffering is divested of its symptomatic character. It is simply “purged” through the most common methods applied to preserve this model: preemptively, devising whatever may be needed to let this distress out or to suppress it; and repressively, treating distress as a matter of law and order. In concrete terms: (1) entertaining people so as to distract their attention from their existential suffering (the logic of leisure, the ideology of competition, the obsession of celebrities, the longing towards possession); (2) comforting them with Hope when distractive activities become ineffective (Religion, the myths of Progress, of Development, of a Better Future); (3) punishing or “healing” them if they cannot fit in otherwise.

The results of this process aimed at concealing the actual causes of the crisis that is consuming us—as well as the effects of the suppression of any sign of distress—are clearly inscribed in the expansion of this crisis. While the rhetoric of “good governance” keeps reassuring everyone that everything is getting better is moving forward smoothly, we witness every day the complete devastation of this planet, the sterilization of any form of human relationship, and the reduction of individuals to factors in production and to objects in Politics, Bureaucracy, Science and Technique.

Life does not consist anymore in what we are, but in what we represent for the civilized world—in the function we must learn to perform through the years. Of course, in such a context there is no chance of asserting the prevalence of the living over what is built (or organized, structured, superimposed), and it is only possible to speed up the degeneration process that is excluding us (as well as the natural world) from modern preoccupations. The overwhelming impacts of this particular world view are plain for all to see. Today toxic agents are faithful allies of civilized life: those we are forced to breathe are not very different from those we are accustomed to drink, or the ones that enrich the industrial food we have learned to eat. Meant as an activity that is separated from life, work takes up most of our time and influences every moment of our existence—from the hours wasted within the shrines of the “sacred” economic production to the time we are allowed to spend away from them. Money, a monetary symbol of things, has been raised to the object of worship in any human relationship. Without money’s intercession, it is almost impossible to establish any kind of relation, and without money there can be no expectation of protection—from bad weather, disease or isolation. Even the fruits of the Earth are subjected to the laws of the market, and the establishment of civilization gradually implied that a price had to be paid to obtain them.

Likewise, the places where our modern existence takes place are increasingly unnatural—from the little boxes where we live far from any direct contact with the Earth, to the unhealthy sites of industrial production. The dullness of urban concrete overwhelms the fragrance of nature, and the roar of engines has invaded our homes in the form of fans, saws, drills or lemon squeezers. This noise vies for primacy against the hubbub of traffic, building sites, and trade and manufacturing activities that had already wiped out the experience of silence a long time ago.

Today everything around us is adulterated. Food is potentially an entity that can be recreated in a laboratory through genetic recombination or through systematic procedures of electronic calculation; pleasure is ready-made; time is scheduled. Even air has been artificially reproduced, and we call this process “conditioned”. “What we call ‘natural’ today”, Raoul Vaneigem noted, “is about as natural as Nature Girl lipstick”{1}. Besides, human contacts are increasingly mediated by machines, our personal isolation is continuously exalted by IT and even our biological life is becoming a lifeless wasteland that will soon be entirely colonized by science and technology. “The absolute pleasure associated with an everyday contact with nature”, observes the ethnobotanist Michele Vignodelli{2}, “has been replaced through over-stimulation by artificial, coarse, mechanical inputs, through fashions, revivals, disco music, roaring toys, cult actors, events... a whole flamboyant, uproarious and desperately hollow world. A rising wave of fleeting inputs, a multitude of fake interests and fake needs where our emotional energies are swept away, drowning us into nothingness … This sumptuous parade seems to consist substantially in the stream of toxic, hidden grudges that flows beneath a surface of politeness, in the corridors of industrial hives; it consists in the snarling defense of one’s own niche, to protect ‘freedoms’ and ‘rights’ that are sanctioned by law, in a deep loneliness which is increasingly hidden in mass rituals, in a universal inauthenticity of relationships and experiences”. Could we ever think that such an existential situation leads to happiness? In fact, sadness and depression desperation [no-one ever killed themselves because of a bad temper. Maybe they broke a few dishes. dominate the civilized world. In the U.S., two million teenagers try to commit suicide every year. And the recent alarm raised by the impressive number of American children who manage to kill themselves on a yearly basis (about 300 among 10- to 14-year-old children, amounting to nearly one child a day!){3} confirms that desperation is not a prerogative of marginal regions at the outskirts of civilization, but is a common reality in the whole modern world. While in those marginal regions people die from hunger and thirst, here we die from an incurable sickness called mal de vivre. Lately a “soul sickness” and a “civilization sickness” have also been openly discussed.

It has been recently noted that “People in industrialized countries may prefer to drown and die in the opulence of welfare and cell phones—but some figures seem to show a different truth. In the United States 600 people out of 1,000 use psychoactive drugs regularly. This means that in the richest and best-off nations in the world, in a country at the forefront of today’s model of development, one person out of two is not at ease in her own existence. And in Europe, suicides have nearly had a tenfold increase starting from the middle of the seventeenth century, growing from 2.6 in a population of 100,000 to the current ratio of 20 out of 100,000 inhabitants”{4}.

Even for Émile Durkheim, a relentless champion of the primacy of society over individuals, the huge increase of suicide rates that was observed as early as the late nineteenth century had to be considered “the ransom-money of civilization”{5}, a result of “the general unrest of contemporary societies”{6}. According to the French sociologist, “The exceptionally high number of voluntary deaths manifests the state of deep disturbance from which civilized societies are suffering, and bears witness to its gravity. It may even be said that this measures it”{7}. Indeed, the massive use of antidepressants, the rampant anorexia/bulimia cases, the establishment of a culture of “anesthetizing numbness” that leads individuals to seek comfort in the use of narcotics, noises, crowds, myths, religions, extreme physical performances, and deathly challenges, or imprisons them in an addiction to pornography, to the possession of technological palliatives and to the mysticism of appearance, point to the fact that “modernity has managed to inflict suffering even on those who are healthy”{8}.

Things, services, titles, rank, status symbols—the material opulence the developed world pours on us, with a claim to keep spirits high, cannot fill the void that has been created inside and outside us by that same abundance. The detachment with which we lead our lives within the strict boundaries of a world of objects suggests that our existence is drifting away instead of pulsating with life. Activities, thoughts, feelings and relationships are increasingly separated from their actors, taking place far away from us, as though they were something alien. Even happiness does not belong to our present anymore—it is a myth we should tend to, something untouchable that is projected toward an ever yet to be future: tonight after work, next weekend, next summer, when I buy a home, as soon as my son graduates, the day I retire…

How often have we exultingly looked forwards to our coming holidays? “Just imagine, my child”, a young grandmother said once to her granddaughter before they left for their summer vacation, “in a few days we’ll go to the seaside and we’ll have two whole weeks to have fun!” It is so: two weeks to have fun. If we consider the length of human life, being forced to rejoice for one peaceful fortnight a year means that we have really learned to be satisfied with little. We are all aware of this, and it makes us suffer. And we suffer even when we manage not to show it. Even when we pretend that this is the right way to live. Even when we remind ourselves that in the amazing world we live in many people don’t even have this rare opportunity. But this is the problem. A life that could be lived with intensity but is constantly set aside, suffocated by an unending series of urgent tasks, of duties that cannot be postponed, of conventions that must be accepted, of all-round commodification, of bloodshed that has turned into routine, of flattering and grudges, hypocrisy and humiliation, coercion and indifference that exclude the possibility of ever being happy, is not a proper life. All the more if we consider that the first prospect offered by the civilized world to tackle the distress it generates is always one of forbearance—suggesting not to think about it too much. Escapist activities, escapist shows, pills to escape: there is a whole range of them, for every taste and for every age. If the world we live in were not a huge cage, we would not have to wish to escape.

****

We have become a product of the cultural and moral patterns that draw the boundaries of our existence, to the point that for centuries even viewing civilization as the cause of our problems has seemed dangerous. However, a critical acknowledgment of our distinctive way of looking at things has eventually breached this bias for some. Also in this sense, considering the past—the existence of those people who lived as uncivilized individuals for million of years and then vigorously resisted the invasion of the civil world—is inevitable.

Today, the idea that our pre-Neolithic ancestors lived in hardship and that their lifespan was considerably shortened by the threat of most atrocious diseases and most terrible forms of violence is only still to be found in the field of propaganda that was exploited for centuries by a certain colonialist ethnocentrism and finally yielded to its obvious unsustainability. Even scientific orthodoxy tends now to deny that the existence of our uncivilized ancestors was characterized by raging, unstoppable misery and by fierce attacks of wild animals, and influenced by a human leaning to mutual aggression within a social background where abuse and oppression prevailed. Anthropologists as well as ethnologists and archaeologists have developed a view of the primitive world that actually clashes with what is envisioned by those who tend to conceive of the past as a calamity we are gradually getting rid of.

Thanks to “field studies” of peoples who still today embrace a lifestyle consisting in gathering the spontaneous fruits of the Earth and in hunting wild animals—the so-called gatherer-hunters{9}—it could be ascertained that they can enjoy a relatively free, simple and joyous life. Joined together in a harmonious context of profound communion with nature, these people could and can benefit from privileges that are perfectly unknown to developed beings; peaceful and respectful, responsible and thoughtful, sensitive and indulgent (especially with the young), they lack any hierarchical or politically centralized organization, as well as social control devices; they don’t know what private property, discrimination or poverty are, and they are often also immune from suicide, crime and war; adult community members (both men and women) usually participate in an egalitarian and informal way in the group’s decisions, turning co-operation into a “social strength” and choosing a nomadic lifestyle. Furthermore, they rarely face diseases and lead a life whose duration is basically similar to the First World’s lifespan, but which is incomparable in terms of satisfaction—free from stress, from the unnerving burdens and duties of the civilized universe, they spend a great amount of time playing (also with children) and devote themselves to recreational activities, company (including paying visits to other camps and entertaining guests), relax, sleep, and even indulging in idleness since the search for food does not take more than three or four hours a day.

In fact, these people are fully satisfied by the pleasure of a present totally their own. Kevin Duffy, a researcher who spent some time with the Mbuti Pygmies (a gathering-hunting community living in the Ituri Rainforest, in the northeast Democratic Republic of the Congo, formerly called Zaire), offers concise and emblematic considerations on the subject: “Try to imagine a way of life where land, shelter, and food are free, and where there are no leaders, bosses, politics, organized crime, taxes, or laws. Add to this the benefits of being part of a society where everything is shared, where there are no rich people and no poor people, and where happiness does not mean the accumulation of material possessions”{10}.

While we should refrain from idealizing prehistory and from raising it to a symbol of a (nonexistent) ultimate perfection, and while, as a consequence, we should not go back to the furthest past of humanity to look for a mythical “Golden Age” and duplicate it, neither should we turn our gaze away from the evidences of a primitive past that found outside civilization its most successful and long-lasting form, in complete harmony with the surrounding world. If we did, we would just give credit to a similarly biased attitude. Undeniably, a “nature-friendly” universe should not find its legitimation only in a faithful reproduction of the past, but in a process that starts from our present and does not need historical proofs or scientific-institutional acknowledgments to be turned into practice; but on the other hand, it is also undeniable that an analysis of civilization aimed at investigating its fundamental features implies a careful observation of those life experiences which, free from the fury of civilization, could offer, for millions of years, a free, peaceful and satisfying existence. If we open up to primitive experiences the reflection on the condition of today’s world, a critical enrichment will surely ensue; trying to reach a synthesis between that past wisdom and the motivations that make us dream a world free from our current torments is the challenge we have to face with our creativity, as men and women of the present time.

****

Far from the values that sustain civilization, human beings lived in tune with nature, refusing to bend it overbearingly to their needs and co-existing with it without doing harm. When humanity ceased to feel entirely intertwined with nature and then separated from it—when we conceived of humans as a distinct entity—that respectful and peaceful co-existence stopped. That primeval sense of strong union with the world found its expression in a collective, not only human consciousness, that led to a complete identification with the energies, elements and creatures of the Earth (in what the French paleontologist F.M. Bergounioux called “cosmomorphism”{11}); when it was interrupted individuals began to subjugate their world, manipulating it to submit it to their needs. That day civilization was born. Even if it has given rise to diverse socio-cultural models, civilization is the essence of this separation. Whatever customs it assumed in time and space—from the Sumerian to the Babylonian, Egyptian, Semitic, Chinese, Greek, Roman, Viking, Arab, Maya, Aztec, Inca, or modern Western society—civilization has always had, whenever and wherever, one identical feature: the detachment of individuals from nature and the establishment of domination over nature.

It is no coincidence that the birth of civilization overlapped, historically, with the advent of agriculture. This practice arose around ten thousand years ago{12} in the so-called Fertile Crescent{13}, forcing Earth to serve human beings according to rules, schedules, cycles, yields, planting regulations– wheat here, corn there, rice over there—that were never in keeping with nature as an “inseparable whole,” but bypassed it in order to please the very people who had separated from nature to become its self-proclaimed owners. With agriculture, the frame of reference changed radically: instead of enjoying the spontaneous fruits of the Earth, humans began to submit nature to a forced, ever-increasing productivity. Instead of nature freely giving, people claim its fruits as masters of nature.

Of course, this transformation of Earth into a productive zone had a huge and lasting impact. As individuals ceased to participate in the living world and started to use it, the world turned into an object. And if its self-proclaimed masters wanted to keep subjugating it, this object had to be tamed. So everything was domesticated, from the surrounding reality (the fields, as well as vegetables, animals, minerals, and the energies of Earth), to people, human imagination, mind, perception, vitality, and relationships (with oneself, with others, with nature). Everything had to be gradually brought under control and changed, manipulated, and shaped to the purpose of this control.

In this sense, civilization meant from the start not only that we had to become numb to the world around us, but also that each aspect of nature had to be controlled.

To look critically at this ambition is to reconsider the roots of how we understand the world. For civilization is first of all a precise conception of the world, which is based on and defends certain values. These include not only the principle of domination, but also the logical-rational abstract way of thinking that leads to knowledge-as-power (culture, science, technology); a utilitarian world view, based on the practice of equivalent exchange and on the transformation of any existing entity into a production factor; and the notion of a centralized, bureaucratic organization of social life, founded on the irreplaceable roles of terror and of the cult of Future. To critique the origins of this world view we must try to unveil the falsity and oppression of life in our modern world. We must, in short, look for questions that address the causes of our ever-growing misery.

****

The term “civilization” derives from the Latin word civis, “citizen”{14}, so its root hides an undeniable truth—that civilization rests on the principle of separation between humans and nature. Indeed, even without dwelling on the definitions by noted Western thinkers who emphasized this separation (from Rousseau{15} to Kant{16}; from the authors of the Encyclopédie Française{17} to Alfred Weber{18}; from the American sociologist Lester Ward{19} to Robert MacIver{20}), civilizing means, according to its origin, turning someone into a citizen. And isn’t a citizen someone who leaves the countryside, the land, nature as an organic entity, to enclose herself in a city—a falsely protective fortress where everything is artificially reproduced or mediated?

Cities, unlike nature, do not offer any food, which must be bought in shops. Cities, unlike nature, do not offer access to the landscape, which is overshadowed by a planned architecture of overpopulation. Nor do cities redeem the human sense of vitality, since they are but a wasteland: from the barren asphalt that covers their streets to the pollution that engulfs them; from their congealed, standardized form to their cold bargaining, apathy and suspicion dominate among the city’s inhabitants.

Urbanization created a growing population density in a habitat built over forests that were razed to the ground. Planned in every aspect, paved, built, sterilized to expunge any contact with life, the city was offered to people who grew less and less humane and could gradually forget the ability to look after their own subsistence processes (gathering genuine food, finding shelter from bad weather, making tools, moving in a totally free and unconditioned way). Social anthropologist Jack Goody summed it up: “No one in the towns is self-sufficient”{21}, acknowledging that urbanization forces us into a state of dependency. Forbidding any direct relationship with nature, cities only allow relationships mediated by the inventions of civilization (culture, science, technology, politics, economics). And as Aldous Huxley pointed out, in cities “People are related to one another, not as total personalities, but as the embodiments of economic functions”{22}.

While the race towards the civilizing of the whole universe is presented today as an urgent need (and escape from nature is promoted as a logic effect that should be casually accepted), a growing number of people are realizing that the self-destructive competition underlying our social existence can be stopped.

Despite the propaganda spread by (supposed) vested interests to safeguard the monstrous artifact known as civilization, it is undeniable that an uncivilized lifestyle can ensure a harmonious co-existence of every part of the Earth—whether human or not—far more than the environmental destruction produced by the civilized world. This holds true not only when there is a “peaceful” relationship among the natural forces, but also when calamities are inflicted on the Earth by nature itself. One example is the tsunami that hit South-East Asia on December 26, 2004, spotlighting the weaknesses of a civilized system that was unable to cope. Death and devastation were inevitable along the Asian shorelines which had been devastated by the culture of holiday pillage. Room-with-a-view resorts have swept away protection by the natural vegetation (especially mangroves) to make room for palatial comforts for powerful Westerners, in contrast with set-apart, discreet, and usually viewless fishing communities that barely manage to survive at the edges of this sumptuous society.

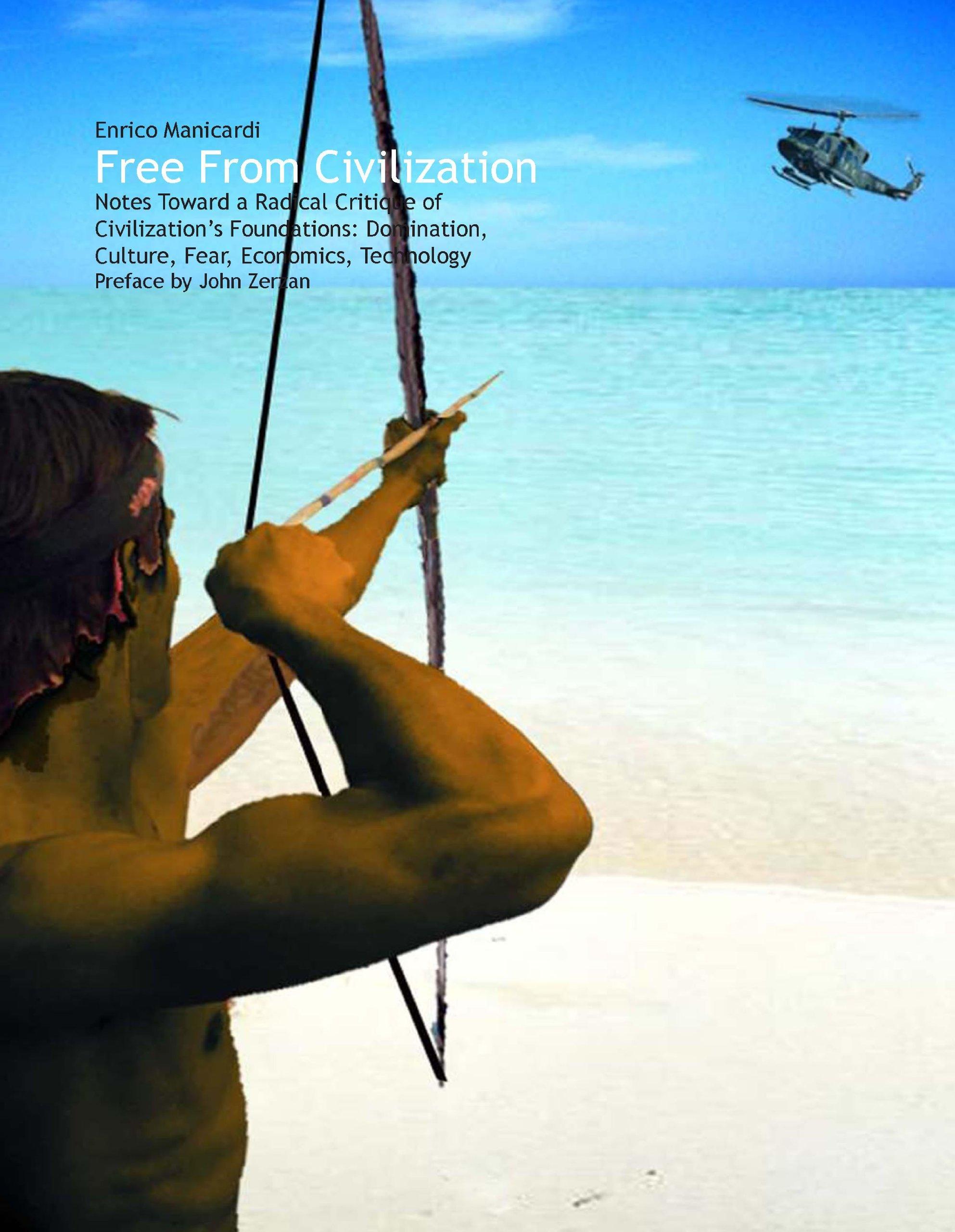

Yet, not far from these marvelous lands that have been unscrupulously looted by this devastating progress, in a tropical paradise which is luckily rather unknown, uncivilized peoples live in the remotest atolls of the Andaman Islands (West from Thailand, in the middle of the Indian Ocean). These populations (Sentinelese, Jarawa, Onge, Akabea, Akakede, Aka-bo, Aka-ciari, Oka-giuvoi, etc) have no leaders, ignore most kinds of symbolic representation of reality (art, mathematics, writing, money, law, religion), do not breed domestic animals, and do not practice agriculture. They eat wild fruits, hunt land animals and fish along the shores, using bows and arrows and other simple tools. Although geographically closer to the seismic epicenter than some of the most devastated nations (Thailand, India, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, the Republic of Maldives), these communities of gatherer-hunters did not suffer any casualties due to the sea-quake.

In fact, despite a decline that began some 150 years ago with British and Indian colonization (genocide, deforestation, road building, poaching, overfishing and enforced sedentism were the gifts offered by civilization to these indigenous peoples) native people of the Andaman Islands have preserved a primeval harmony with the living world. The Andamanese enjoy that vision of life which has stopped elsewhere with civilization, consisting in a deep-felt union with nature. This union allowed them to simply find a safe place during the sea-quake, as did every free animal living in the areas hit by the tsunami. What helped the Andamanese natives save themselves, reported Francesca Casella from the Italian branch of Survival International, was “their sophisticated and profound knowledge of the ocean and its movements, gathered in thousands of years of life on those islands and passed from one generation to the other. We know, for instance, that the Onge escaped to the hills as soon as they saw the waves retreating, as they were aware of the risk of flooding. Apparently, some groups were alarmed by the wind, the flight of birds and the movements of animals”{23}. Geologist Mario Tozzi, a well-known Italian anchorman, recently wrote in his book Catastrofi that, during the 2004 tsunami, “luckily no ‘savage’ got extinct. How so? These are tribes who live at close contact with nature… they don’t practice agriculture, and lead their existence much as our ancestors from ten thousand years ago. They have no technology… always acted simply according to the laws of nature, keeping in mind Earth’s memory more than any expert or commentator ever could… Many indigenous people who were on the shores immediately fled to the bush as soon as they realized that the tide was out of tune with the usual tidal rhythm… Aren’t perhaps the ‘primitives’ right? Isn’t someone else wrong somewhere?”{24}.

Tozzi’s question seems quite relevant. In fact, while these natives simply grasped the warning signals that nature always sends before a cataclysm and saved themselves, civilized people were not able to do so. Even those who lived in those very islands but had adapted to a modern lifestyle did not survive. Having become deaf to the warnings of their environment, they were unable to understand what was happening and tragedy was inevitable for them too: “in the civilized part of the Andaman islands—where a ‘Tourism Festival’ should have taken place on the 7th January—there were 9,571 casualties and 5,801 missing people”{25}. The same situation was observed not far away in the Nicobar Islands: while the 380 natives of the Shompèn community who live from gathering and hunting in a remote area of Great Nicobar were completely safe, the rest of the Nicobarese, who “are not hunter-gatherers but small farmers… who have mostly been converted to Christianism… were swept away by the waves and suffered many casualties”{26}. Meanwhile, a sophisticated tsunami detection system created by the United States, based in Hawai’i, registered the tsunami without grasping its power, or warning the region of oncoming danger.

What is perhaps most remarkable about this disastrous event is that most people in the civilized world never stopped to think about what had happened. Of course there was general distress, unanimous mourning and wide solidarity, but there was no willingness to look into the causes of that disaster (or those that followed). Rather than try to understand what has happened, people in the civilized world prefers to close our eyes: it is nature’s fault, calamities are inevitable, it was an act of God. Having dismissed the tsunami as a “natural” disaster, civilization, numb and self-important, continues on a straight line toward its dead end. Mario Tozzi’s questions do not undermine the developed world’s certainties, and as Giuseppe Castiglia noted while observing the aftermath of this tragedy that swept away 230,000 people in few hours, and left more than two million homeless, we can all see that “the great machine of international, global donations is mainly anxious to restore the existing situation, to rebuild and re-create those artificial paradises, as though we wished to erase and suppress a nightmare without wondering too long how come we experienced it”{27}. What civilized humanity has ceased to understand, namely the living world, is subjected to its logic-rational knowledge and thus fails; what civilized humanity has ceased to feel, namely the language of the Universe, is deciphered through machines and thus fails; what civilized humanity has ceased to respect, namely the harmonious progress of nature, is transformed according to her will and thus fails.

The ghost of the arrogant ideology we call civilization looms more and more over people’s fates. It has turned human beings into caricatures, leaving them to the mercy of nature, which they forgot how to understand but over which they claim to be masters—the strongest, most intelligent masters. The more humanity wears the tragic cloak of anthropocentrism, the more we estrange ourselves from nature, and see nature as hostile, adverse and brutal. In the end, the only way to combat nature’s hostility is to impose an implacable formal order.

This process has already reached an advanced state of degradation. Having turned nature into a foe, we see only enemies all around. The sun burns our skin accustomed to closed spaces, diseases become incomprehensible threats to our health, physical pain is a curse that must be averted at all costs. Even death is not viewed as a natural event anymore. In the Dionysiac sphere of people drunk on civilization, the end of life is simply banned, cancelled, eliminated. Death is materially hidden from our gaze (through compulsory hospitalization and burial in secluded places outside human settlements). Death has been even ideologically suppressed inside our hearts (through the religious myths of resurrection, reincarnation, rebirth, eternal return, transmigration of the soul, or metempsychosis; or through the secular myths of civil immortality: glory, fame, prestige, celebrity).

Seen through the eyes of someone who has lost any contact with their balance, gloomy autumn days turn into an unbearable downpour, fog becomes a senseless hindrance to traffic and wind is a challenge to our costly party hairdo. In the civilized world, we always blame natural conditions, not the circumstances which have been generated by the altered superimposed context that has compressed and disrupted them. Asphalt is made slippery by rain, not rain that cannot drain through asphalt. Age is at risk of disease (heart attacks, diabetes, osteoporosis), not diseases that are a consequence of our unhealthy lifestyle. Forests are dark and treacherous, not our disaffection towards a natural life. The Andamanese gatherer-hunters—just as any other primitive community—know perfectly well that their existence is not menaced by nature but by civilization, and showed this also after the tsunami. After that sweeping wave, the Indian government sent its helicopters to the islands to gather corpses and provide the survivors with “help” (canned food, medicines and whatever could make the natives dependent on the remedies of the modern world). However, far from finding any dead natives, or a frightened or needy people, they encountered a united and solid community that was not enthralled by those flying machines (or by the fake support offered by their passengers). The Andamanese people launched a shower of arrows to discourage the pilots from landing—as if to say: “Keep your civilization to yourselves and go away!”

****

We have ceased to understand nature, and this ignorance is turning against us. An increasingly militarized domination of the world will not be sufficient to reassure us; a stricter and more formal order will not be sufficient to restore a peaceful existence in this environment. Instead, the more austere and universal this order becomes, the more we will be exposed to new disasters that we will keep calling “natural”, denying our responsibility as exterminators of the balance in our ecosystem. The devastation carried out by civilization against our planet with increasingly sophisticated and invasive means will not be limited by new safety rules, more sophisticated devices or seismic upgrades.

As though it were possible to protect public health by limiting air toxicity—instead of rebelling against the logic that lies behind this pollution—we focus on limits, benchmarks, acceptability comparisons, formal references (in terms of regulations, scientific criteria and economic production). As though it were possible to win freedom back by painting the walls of our prison, we are seduced by the guards/painters’ flatteries, promising us a more colorfully decorated cell. However cleaned up and whitened, a jail is a jail, just as a lawfully poisoned world is poisoned. Indeed, a beautiful jail is even more difficult to demolish, since its beauty hides its restrictive function. The same applies to the pollution of our planet, which, once legalized, becomes untouchable.

Civilized society knows how to regenerate itself even without overt brutality; the subliminal weapons of persuasion are sometimes much more effective. Drawing its strength from the passivity it creates, civilization is able to expand, fortify, and get established in our minds, hearts and bodies even before it gets established in everyday life. And after it has neutralized the “dreams of freedom” dreamed by an unshakable part of the youth’s imagination in the face of such a clearly unbearable reality, civilization teaches us that adults don’t protest and are not ashamed or outraged by the conditions in which we must live day after day. We learn that the only feasible response to the devastation of everything and everyone is to fight for a “sustainable” devastation.

We shouldn’t aim for a lawfully polluted world, but a non polluted world. What will make us feel liberated is not a life contained in a newly painted cell, but a life enjoyed in the open air. Letting the pervasive system where we are domesticated and set aside from the others dominate our lives will not help us restore meaning to our lives. Failing to oppose the pervasive system that uproots us from the living world and puts us to work for civilization will not help us assert the dignity of a life that wants to live, not simply to “be lived”. “The world must be remade”, Vaneigem protested{28}: patches, buffers, expedients will lead us nowhere. Pursuing the target of an “acceptable” decay will not set us free from decay. Making civilization more just will not free us from its deceptions, dependencies and cages.

To replace the consoling expectation of a better tomorrow with an alive and kicking present, we must invigorate the will of an all-pervasive life—a life to be felt on our skin, to be led with creativity, independence and desire. A life that thoroughly heals the fracture which kept us too long separated from the Earth, in a union of co-operation instead of competition, of freedom rather than of discipline, of respect rather than of reverence, of sympathy rather than of apathy, of communication rather than of confrontation, of interaction rather than of exchange, of real contacts rather than of simulation, of pleasure rather than of boredom. In a phrase: a life to be lived rather than managed.

Making civilization seem natural was civilization’s first strategy to perpetuate itself. Civilization’s paradigms, comforts and alleged truths are all means to this end. We must expose the reality behind these measures, drawing everybody’s attention to them, confronting their role in perpetuating the toxic wasteland that imprisons us. We must try to look at civilization without its scepter, without the aura of solemn venerability that makes it mythical—and therefore inviolable and inevitable—to our eyes.

The acknowledgement that civilized existence is fundamentally a total defeat of life flows through us in form of discouragement. Everybody has felt that sense of disappointment that stems from our realization of the low quality of our accustomed existence. If we don’t want this graveyard of civilization to imprison us forever, we must try to regain control of our lives. We must unveil the root cause of our everyday distress: the wretched process we call “civilization”. After all, if terror is to blame, we know what generates it; if war is to blame, we know what theorizes it; if exploitation is to blame, we know what desperately needs it for its very existence—civilization.

Part 1: The Mentality of Domination (A critique of domination)

I. Dominion over Being

1. Abomination of Domination

To exert power in every form was the essence of civilization.

— Lewis Mumford, The City in History: its origins, its transformations, and its prospects

Dominating means subjugating, owning, submitting to one’s own super vision; in sum, it means regulating according to one’s command. Imbued with a perspective that is irreducibly linked to the will to submit, thereality of the civilized world is fully permeated by relationships of mastery and subjection. In the modern world, everything can be explained by the practice of power of somebody over somebody or something: of parents over children, of teachers over pupils, of employers over employees, of rulers over citizens, of humans over nature. Instead of trying to get in touch with the reality around us, we are used to looking at everything from top to bottom (or from bottom to top): the goal is never to “get closer” but to “stay on top”, to master, to determine. To control, as Italians say “to keep in one’s power”, defines our relationships with the world, starting from the way we perceive the world ( to know something, you must master it). There is no place in civilization for disorder, dynamism, astonishment, wonder, for the ineluctability of life. Only what looks manageable (even mentally) is allowed: the predictability of events, the groundwork and arrangement of things, their exact understanding through fixed patterns of a logical-scientific rationality from which no digression is permitted. Things must be constantly organized, structured, transformed, shaped according to our will. If something is not “right”, it has to be “right”, whatever the cost. Life, to a civilized person, is never a creative openness to existence. It is a busy activity of world subjugation, initiation into a system of rigid rules to be respected and imposed upon others.

We are so distant from natural life that disorganization is frightening to us, spontaneity does not belong to us and genuineness make us feel uneasy. Terms such as “improvisation”, “naivete”, “instinct” now have a negative connotation. The same has happened to adjectives referring to a natural way of life as “feral” or “wild”. A “wild” place is thought to be inhospitable, scary, inaccessible. A “feral” person has to be irritable, shy, a misanthrope. In a few words, nature has been “intellectualized” (Lévy-Bruhl’s term[1])—brought from the soul to the head, and thence pushed out to be scrutinized. Then nature can be used, exploited, dismantled and assembled at will. Method, procedure, logical and rational thinking are the only way to connect with life. Obviously, if you keep the world at distance, you don’t get closer to it. Under the weight of prejudice and ideology—the only tools to think about ecology and environment—we set nature apart. Unknown and misunderstood, nature comes back only after eluding our sovereignty with unexpected, unrestrainable forces.

In this mastery/subjection framework, you are either subject to the authority or an enemy. So, far from being an element of inspiration, nature has turned into a threat. A vindictive and oppressive power, not a harmonic set of elements linked with the human world. Nature always looks obscure and brutish. The natural world seems distant to us; it is threatening, not fascinating. Our environment is hostile.

In the civilized world being natural is not natural—it is an eccentricity/oddity. For instance, a couple of parents have been defined as “hard-bitten” by a pediatrician because their 3-year-old daughter, who was absolutely healthy, was born in a private house, and had had no religious consecration or medical initiation (vaccines, antibiotics, repression of her liveliness through drugs). Being born and living according to nature nowadays makes you “strange”, “excessive”, “extremist”. Even pleasure has lost its natural connotation, becoming a cultural process, a taboo: something to hide, to turn into a sacrifice (work, social roles, orders to be performed). We don’t feel comfortable when talking about a lazy day; we are proud to talk about a life marked by labor, by mechanical repetition of the same gestures. Masochism towards ourselves; sadism against the others. People around us must learn to suffer as we suffer; to slog away as we labor; to accept the unbearable as we do. Obviously children are the first victims of our frustrations: it seems unnatural to leave them alone, without teachers, sport trainers, educators; it seems harmful to leave them in their living universe, in tune with the energies of the land; it seems unproductive to leave them free to explore the world, only to jump, to climb, to run in the open air from morning till evening. There’s nothing bad in playing, we say, but don’t forget the real world, we add to justify our repressive behaviour. Only the real, serious world makes sense to us: the serious things of a serious world in which there is no place for joy.

Nothing to laugh about where power prevails: go to a church or to a monastery, and you get it. Supremacy asks for darkness and austerity. As Umberto Eco suggests in The Name of the Rose, laughter has nothing to do with ruling, with command. No jokes in the civilized world. Yes, seemingly it looks shining, sparkling, like a party, but there are no jokes. No jokes with Power. No jokes with Duty. No jokes with Religion, with Money. Not even with Business, nor with Education, Schooling, Ethics and the Defense of Values: Homeland, Family, Law, Order. The free spirit of our ancestry, according to Marcello Bernardi, “has been replaced by an unpleasant state of being: alienated labor, competition, an obsessive hunt for success, the need to mask our real personality, to lie, to simulate, in order to look different, better, stronger, more important.... and so minding carefully about what we say and what we do. What a hell of life. But society wants that and usually we adapt. We come to think that accommodating to the needs of economy and society is the only way to survive.”[2]

In other words, we are upset with free life and indulgent with alienation; aggressive with nature and tame with law. We oblige our children to turn their activity into “labor”, their desire into a “duty”, their playing into a “challenge”. We are reassured to put them in a line, stuffed with notions, still on their school bench (for the same 8 hours that we suffer). We love our children, but control (of nature, of our nature) makes us insensible to the pain of authority. That’s how alienated we are from our true selves. Culture, not nature, is beyond criticism, in a civilized world.

In the beginning, the oneness of the human and the natural world was a safe landmark of our identity. In the words of Kirkpatrick Sale, one of the founders of the North American Bioregional Congress, “the Indo-European word for earth, dhghem, is the root of the Latin humanus, the Old German guman, and the Old English guman, all of which meant ‘human’, The only remnant of this sensibility I can think of today in our everyday language is humus, the rich, organic soil in which things grow best”.[3] Humans find the roots of their identity in the land, even before that in their name, language, local traditions and customs. The living ecosystem we call “Nature” is our “home”: the term ôikos, “eco-” (from the Greek “home”) is the first element of all the composed words referring in a scientific language to “nature”: ecology (science of the nature), economy (administration of nature), ecocide (the killing of nature).

In Nature humans and non-humans can develop their lives, make experiments, express their personalities, arrange relationships. But Nature is not a uniform framework, a priori determined by reason. Nature is alive, and humans knew it, until the moment in which they were trapped by the ruling dynamics of civilization.

For our early primitive ancestors, the world around and all its features—springs, rivers, clouds, mountains—were regarded as alive, endowed “with the spirit and sensibility every bit as real as those of humans, and in fact of exactly the same type and quality as a human’s”[4]. For children, women and men living in the Planet Earth for 99.6 percent of the duration of human life, “there was no separation of the self from the world as we have come to learn, no division between the human (willed, thinking, superior) and the non-human (conditioned, insensate, inferior).”[5] Before civilization taught us to develop an individual “self” in order to built walls against the external world, there was no hostility against nature. Life was flowing with no need of determining it or controlling it. Living was only living. Today our life follows the rules of order and discipline. We live according to a script. From dawn to dusk our life is scheduled, organized, determined.

We are part of a mechanism that separates us from the natural world and we are more and more addicted to this mechanism. Science and Technology make us dependent on their devices. Education teaches us to follow instructions. Economics pretend that we cannot live without economy. Power makes us subjects of authority and Money greedy for dollars. We no longer feel ourselves connected with the earth. We feel linked with culture and ideology, the superstructure used to master nature, and we need them because we have lost the consciousness of our oneness with the living earth. We do not think of ourselves as subject to Nature but as hegemonic individuals. Concepts like “inferior” or “lowest”, no longer considered correct when applied to humans, are welcomed as labels for non-humans (animals, or a tree or a forest). And when the civilized world tries to respect nature, an equality gap is evident: it is a false respect based on a hierarchy that puts humans on top: humans, then animals, then plants, and finally minerals.

Ruling asks for subjection, and with subjection you have no equality: soon the exploitation of the subject will appear. The force of primitive life was the refusal to rule the world. Our paleolithic ancestors, as part of nature, refused to dominate the world. Symbols like doves for peace, flowers for marriage, rice for fertility, or rites such as decorating a Christmas tree or burying a dead person in the earth, can be read as a memory of this lost oneness of humans and nature, the psychological and material environment of our ancestors during millions of years. Robinson Jeffers wrote in The Answer, “The greatest beauty is organic wholeness, the wholeness of life and things, the divine beauty of the universe. Love that, not man apart from that.”[6] To forget that precept means forgetting ourselves, going away from ourselves, disavowing ourselves.

2. Alienation, Reification, Domestication

Terms like reification and alienation, in a world more and more comprised of the starkest forms of estrangement, are no longer to be found in the literature that supposedly deals with this world. […] the conversion of the living and autonomous into things, into objects, is the foundation of civilization. Domestication is its pronounced realization.

— John Zerzan, Running on Emptiness