Gary Greenberg

In the Kingdom of the Unabomber (Author's Edition)

In 1998, the author, a psychotherapist and occasional college professor, began a correspondence with Theodore J. Kaczynski. Herewith, the results so far.

I. Please Forgive My Intrusion Into Your Life.

II. A Letter With Five Footnotes.

IV. A Brief History of the U.S. Postal Service.

VI. "He Probably Never Felt a Thing."

VIII. In Which the Author Discovers That 'the Unabomber is a Complicated Man.

IX. The Six Stages of Moral Development.

XI. Dr. A. Tumbles Down the Oubliette.

XII. The Unabomber Plays Shrink.

XV. "If I Were a Tattletale ..." (the Greenberg Embargo.)

I. Please Forgive My Intrusion Into Your Life.

THE FIRST TIME I got a letter from the Unabomber, I had my wife open it.

I was at work, the letter had come to my house, and neither of us wanted to wait to see what Ted Kaczynski, whose outgoing mail was by then inspected by the United States Bureau of Prisons, had to say. Sealed in a #10 envelope, the letter was addressed in the careful block capitals chat the post office says will guarantee maximum efficiency. He even put his return address, in the same frank print, in just the right spot. No fool, Kaczynski knows that the mails will only work for you if you work with them.

The first letter, which arrived in mid-June of last year, had not come unbidden. Six mo1:1ths earlier, just after he'd pleaded guilty to the Unabom crimes, I'd written Kaczynski a letter. Although I had paid dose attention to his case for nearly three years, from his emergence as a composite sketch demanding space for his manuscript in a national publication to his arrest, incarceration, and abortive trial, my letter wasn't fan mail. Instead, it was a pitch.

Here's how it went:

January 24, 1998

Dear Mr. Kaczynski:

Please forgive my intrusion into your life. I am not sure if this letter will gain a sympathetic reading, or any reading for that matter. But after thinking long and hard about writing it, I'm taking the chance.

I would like you to consider allowing me to write a biography of you. I am sure you have had many requests from other people to do this, and for all I know you are already working with someone. Or, for that matter, you may be opposed in principle to the very idea. In the event, however, that neither of these are the case, I hope you'll read on and think about my request.

I know nothing of you, of course, except what the news media have decided to tell me, so what I am about to say is no doubt presumptuous – it's just my reading between the Iines. It seems to me that you are one of the notable antimodemists of our age. At least since saboteurs hurled their sandals into machines and Luddites rioted in factories, people have deeply (and sometimes violently) objected to the fundamental tenets of the modem world. This protest is not against one or the other work of technology - against, say, nuclear weapons or automobiles - but rather against the world view that underlies and makes possible the creation of any particular machine or device. And, as many antimodernists have discovered, this world view does not tolerate radical protest. It must either co-opt it or eradicate its opposition, the latter through outright killing or mere discrediting. I believe this is one of the reasons that there has been so much interest in finding a psychiatric diagnosis for you: not, as the various lawyers have claimed, to ensure that you are competent or sane to stand trial, but rather to dismiss your protest as the ravings of a lunatic.

I should acknowledge here that I have firsthand knowledge of this misuse of the mental health profession, as I am a psychologist. My research and writing, however, have always been deeply critical of many of the practices of my profession, particularly insofar as it tends to pathologize what it does not understand or cannot tolerate. I have no wish to understand you as "schizophrenic" or "paranoid" or any of the other labels that have seen thrown at you. To the contrary, I wish to tell your story partly in order to show how limiting and harmful those labels can be, both for the person who is labeled and for the society which might otherwise benefit from listening to him or her.

I should also mention that I know something of what it is like to try to live by antitechnological principles. Like many of our generation, I spent a number of years in a cabin in the woods with no plumbing or electricity, trying to live off the land. Circumstances forced me out of my refuge, but I will always remember both the difficulty and the joy of life off the grid. I will always remember the suspicion and outright dislike I aroused in people who could not understand what I was doing. and how precious the few who did understand were to me. Without wishing to seem presumptuous, I think I recognize in your story some of my own, and I think I see in your decision to live as you have an integrity that I deeply respect.

I believe your story deserves to be told with a sympathetic voice in a manner that does justice to the deep truth of your principles. I feel certain that I can tell it this way. I am an experienced writer and interviewer, and I would greatly appreciate the chance to use my skills and talents on your behalf.

If you are interested in pursuing this any further, you are welcome to use the enclosed envelope to write me or to call collect if you can arrange for that. Or, if you like, I can come to see you. Whatever you decide, I wish you well, and I hope to hear from you soon.

Regards,

Gary Greenberg

My prospective subject was interested enough in the project to ask, through his lawyer, for more information about me. So, during the spring, I wrote Kaczynski a short autobiography. I told him about my therapy practice and my teaching, even a little about my personal life, and I sent him some of my academic writings - two articles and a book. I heard nothing directly, and in mid-May, 1998, after he'd been sent to the Supermax prison in Florence, Colorado, I sent him a gentle reminder of my existence. His first letter came in response.

Kaczynski couldn't know that he had written this letter on my 41st birthday, but despite myself, I allowed the coincidence to take on some meaning. Midlife had left me wondering about my professional craft, hard-pressed to fulfill therapy's promised miracle - not the offer of quick cures for psychic suffering, but the extension of a hope as American as Plymouth Rock: that with honest hard work, some weeping here and some soul-searching there, anyone can pursue and find happiness. The miracle embedded in this promise is that it keeps alive the possibility of a good life amid the execrable social order that Ted Kaczynski wanted to destroy.

The first letter itself wasn't much: a four-page, single-spaced document, handwritten with pencil. There were no signs of erasures or corrections. The prose didn't so much flow as march steadily from the beginning of an idea to its end, with nary a false logical step in the parade. Above all else, the letter conveyed a calm rationality, a sharp intellect, and a distinct courtliness. Kaczynski had detected my impatience to hear from him and explained, without complaint or self-pity, the restrictions under which he labored, the difficulty in getting money for stamps, the necessity of submitting letters to prison officials, the fact that he did not get my book because, according to some inscrutable prison regulations, he was not allowed hardcover editions. He informed me, out of fairness he said, that he was probably going to write an autobiography, but he allowed that a book by someone else would still be a worthwhile addition to the knowledge about him. He seemed accustomed to thinking of himself as a historic figure.

And then he asked me a question, based on the articles I had sent him: Did I really believe, he wondered, that there was no such thing as objective truth? After all, he said, a nuclear bomb's effects are predictable and deadly regardless of the culture in whose midst it explodes. He wanted to know how my relativism, which he'd detected in my critique of psychiatric practice, could encompass this fact.

I wanted to know why he chose that particular example.

Even more, I wanted to know how the person who had fashioned this note, with its politeness and sensitivity, its levelheaded clarity, its measured expression of frustration - how this person had spent 17 years of his life perfecting. a technique for building bombs and delivering them to people he didn't know.

But most of all, I was taken with the queer quiddity of it, the fact that I was holding in my hands a letter from the Unabomber. I don't have much sense of the allure of the artifact. I've stood in Monticello's preserved rooms, passed in front of the liberty Bell, trod the ground at Gettysburg, paid due respect to the cause or the person or the event without hearing history speak or feeling the moment. But holding this letter, I glimpsed the engine that drives the history buff, the collector of autographs, the high bidder at auctions of John F. Kennedy's clothing. I wasn't finding my place in the flow of histo.cy, in the great unfolding of human events. None of that matters anymore anyway. All that's left is spectacle, and I had something spectacular in my hands: a letter from a man whose name everyone knew. Ted Kaczynski had written me a letter - by hand, no less. He wanted to know what I thought about heady philosophical matters. I felt hooked up, plugged in, reached our and touched. I went out and rented a safe deposit box.

II. A Letter With Five Footnotes.

THE SECOND LETTER I got from Kaczynski came in early July; it was 20 pages long. It was addressed, "Dear Gary," and signed, "Best regards, Ted Kaczynski." From then on, we were on a first-name basis.

Some of the letter was personal: Kaczynski agreed with me that living in the woods was alienating, but that hadn't bothered him as it had me. Some of it was revealing: he told me that he had long had a recurring nightmare in which he and his cabin were transplanted to an island in the midst of a huge shopping mall. He paid me a compliment, telling me that he thought I was someone with whom it was possible to have a rational conversation. He insulted me, using one of my papers as an example of the way that philosophical writing buried its insights in "bullshit." Most of the letter was as dry as a math textbook. It had five footnotes, which ranged from simple amplifications of what he was saying to quibbles with me about my interpretation of early Christian martyrdom. The Unabomber had written me a treatise.

I should explain the occasion for this outpouring. The paper he criticized had nonetheless hit close to home for Kaczynski; it had an indirect but significant bearing on his case. The article was about a curious development in my profession. On a day in 1973, the psychiatric industry had eradicated a disease that had theretofore resisted all attempts at treatment and ruined many lives. After two years of contentious meetings, disrupted conventions, and what one psychiatrist called "fevered polemical discussion," the American Psychiatric Association officially deleted homosexuality from its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. The love that dared not speak its name was now safe to discuss with the doctor. Not only was homosexuality no longer an illness, it had never been. It was all just a misunderstanding, and the doctors were very, very sorry.

This change was both good and bad news for the industry. The good news was that it explained why those millions of couch hours had failed to make desire flow in its proper channels. The psychiatrists hadn't lacked skill; they had just tried to use it to fix something that wasn't really broken.

This good news led to better: a new disease called "ego-dystonic homosexuality." To the relief of therapists everywhere, gay people still needed professional help no longer to try to reorient their sexual compass, but now to combat the effects of living in an intolerant society. Homosexuals were suffering not from homosexuality but from internalized oppression. The very doctors who had legitimized the stigma now stood at the ready to help its victims reclaim their dignity and accept what they once sought to eliminate. Of course, no one was going to get their money back, or even credit toward treatment of the new disease. This wasn't penance or community service, but capitalism at its most exuberantly irrational.

The bad news, though, was grim. As one psychiatrist said, "If groups of people march and raise enough hell, they can change anything in time Will schizophrenia be next?" You can see the problem: all the hellraising in the world won't stop cancer from eating up your insides, but enough marching might relieve psychiatrists of the power to make pathology out of deviant behavior. This would be a disaster for the industry. And even if it didn't materialize, its very possibility was troublesome. The unmistakable hustle of therapists to keep up with the times, to avoid eating the dust of the sexual revolution, revealed psychiatry's darkest secret: that most diagnoses are moral judgments wrapped in medicine's cloak, and that therapists are really clerics disguised as scientists.

My paper was about the industry's response to this bad news, how it had been caught with its pants down but still managed to maintain its professional dignity and protect its franchise on the scientific understanding and treatment of human behavior. It's one of the great public relations coups of the 20th century, and it was of vital interest to Kaczynski because, in his view, if psychiatry had lost its franchise, he might not be in his current position: left to rot in Supermax, where his bed and table are m de out of molded concrete and exercise takes place in a kennel.

Instead, he'd be dead, or at least under a death sentence.

To understand why my paper got a 20-page rise out of Kaczynski, you have to know a little Unabomber history.

Kaczynski's lawyers knew a hopeless case when they saw one. There was a warehouse of evidence against him: bomb-related hardware, journal entries lamenting his failures and applauding his triumphs, various eyewitnesses to his whereabouts. Even Hamilton Burger couldn't have booted this one. Worse, the federal government had a new death penalty, and the Unabomber seemed a fitting early target: he'd committed heinous crimes, embarrassed the FBI by eluding them for almost two decades, and seemed entirely unrepentant. To his lawyers, this meant that there was only one possible plan: to find a defense that would minimize their client's chances of getting executed. But to Kaczynski, this was an end that served the lawyers more than their client. And this wasn't fair, as he wrote to attorneys whose support he sought after he had been convicted:

The principle that risk of the death penalty is to be minimized by any means possible... is very convenient for attorneys because it relieves them of the obligation to make difficult decisions about values or to think seriously about the situation and the character of the particular client.

The problem, in Kaczynski's view, was that the single course that would save his life was to turn to the psychiatrists and make him out to be a crazed killer. After all, if you're going to kill in cold blood, which is what a juror is asked to order, your victim had better be a villain and not someone to whom you can, as we therapists say, relate. Fortunately for defendants with good lawyers, there is no end to my profession's ability to commonly denominate the most heinous act or the most loathsome personality: Charles Manson had a mother too. Thus is revulsion turned to empathy, and all transgression's horror reduced to the banal recitation of trauma everyone might share.

So the defense rounded up its investigators and psychiatrists to prove that this hermit, with his poor hygiene and inscrutable mailing list, was a nut. They even arranged, in a strange fulfillment of Kaczynski's bad dream, to bring his cabin to Sacramento for the jury to examine.

"You've got to see this cabin to understand the way this man lived," said Quin Denvir, his lead defense lawyer. What you would see, Denvir explained to the press, is the external manifestation of a demented mind. "The cabin," he said, "symbolizes what had happened to this Ph.D. Berkeley professor and how he came to live. When people think about this case, they think about the cabin."

Back in the early 80's, when I lived in my little cabin, I knew people who thought I was nuts simply by virtue of my chosen lifestyle. If I had had legal trouble, I don't think I would have wanted my lawyer to be among these doubters. But that was Kaczynski's situation. His lawyers wanted to save him from, execution, and to do so they were willing to turn the better part of his adult life into a case study. Kaczynski didn't want his life saved chat badly.

He did manage to make the psychiatrists and psychologists they sent his way aware of his opposition. The doctors went in under various covers: to help him with his sleeplessness in the noisy jail, a condition that one doctor called Kaczynski's "oversensitivity to sound"; to give him tests that might prove that he was neurologically intact; to assist in the preparation of his defense. And they all came back empty-handed: no raving lunacy or other florid symptom to report. Kaczynski refused to talk about his feelings, terminated interviews when clinicians started to talk about his mental illness, and told his lawyers repeatedly that he would not cooperate with their defense.

Kaczynski had opted out of American culture in the late 60's, at just the time that everyone was learning to speak the language of therapy, but it wasn't ignorance that kept him from a crying confession of psychic pain. He knew just what the shrinks were up to - not only in terms of his trial, but in the larger sense: they were trying to tell his story in their language, which was unacceptable to him.

Many clients refuse to accept the therapist's authority, but most are reduced to the squirming prevarication we call ''resistance": missing appointments, changing the subject, disavowals of feeling. But Kaczynski just up and said it. Dr. David Foster, who met with him five times in 1997, wrote, "Early on in our sessions, he looked me in the face and said, 'You are the enemy."' For an academic paper I wrote about his psychiatric diagnoses, Kaczynski elaborated on this comment:

[What I was doing at the time] was simply laying on the table in a civil, or even friendly way, as a matter that needed to be taken into account in our discussions, the fact that Foster and I were on opposite sides of the ideological fence, that he as a psychiatrist was an important part of the system I abhorred, and that he was in that sense an enemy.

Now, there's only one thing to do with a person who won't behave like a client: throw the book at him. In Foster's version, Kaczynski's candor reflected "his paranoia about psychiatrists," itself part of his "symptom-based failure to cooperate fully with psychiatric evaluation." Thus, there are no principles in this world, only symptoms; no politics, only pathology. Of course, Foster, like all the others, knew what everyone else knew: that this man was the Unabomber, so he must be crazy. The fix was in from the beginning. Even his defense lawyers were in on the game, ultimately arguing that Kaczynski's disagreement with them about the mental-defect defense was more evidence of his mental defect. No wonder they all thought he was paranoid - they were out to get him.

Finally, after months of trying to resolve this conflict, after endless motions and counter motions and chambers conferences, even after some highly unusual letters from Kaczynski to Judge Garland, Burrell - virtually begging him to relieve him of his lawyers - on January 5, 1998) the day his trial was to begin, Kaczynski stood up and said, "Your honor, before these proceedings begin, I would like to revisit the issue of my relations with my attorneys. It's very important." Kaczynski and the lawyers filed back into the judge's chambers) where he once again explained that he could not endure the daily injustice of a portrayal that could not be refuted. And now, he said, he was done with these lawyers. He wanted a new one: Tony Serra, a San Francisco lawyer who had lurked on the margins of the case for 21 months, and who had promised to nor use a mental defect defense.

Serra proved to be unavailable. On January 7, Burrell ruled that Kaczynski's lawyers could introduce mental-status evidence, even against their client's wishes. Later that day, Serra finally surfaced, offering to take over the case, but not for nine more months, a delay that Burrell was unwilling to grant. Here is Kaczynski's account of what happened next, taken from his appeal. It's in the third person; Kaczynski the lawyer referring to Kaczynski the client:

During the night of January 7-8, Kaczynski attempted suicide by strangulation. When he applied the arrangement he had devised for strangling himself, he felt that his sight was growing dark and that he was losing consciousness; but too slowly, so that he feared he might become unconscious yet not die, and might perhaps be left with disabling brain damage. Hence he released the strangulation device, intending to try again with a better arrangement.... On the morning of January 8, before court opened, Denvir and Clarke [his lawyers] came to see Kaczynski at the holding cell outside the courtroom. Kaczynski said to them in agitated tones, "Look, I can't take this… Isn't there any chance that the judge might still let me represent myself?"

Denvir and Clarke were shaken by Kaczynski's obvious desperation, and they agreed to help him secure his right to self-representation.

But Kaczynski was crazy, or so the psychiatrists said, and a crazy man cannot represent himself. Now, at long last, the Unabomber was going to have to submit to the mental health experts: Judge Burrell refused to rule on the request for self-representation until Kaczynski cooperated with a psychiatric evaluation. Sally Johnson, a psychiatrist who had come to prominence when she determined that John Hinckley was insane, was flown in,

Johnson worked at amphetamine speed. In five days, by her own report, she read the full Unabomber archive, which by now took a single-spaced page simply to list and included "the complete set of writings obtained from Mr. Kaczynski's cabin in Montana," reportedly some 20,000 pages long. She interviewed all the lawyers on both sides, his mother, his brother, all but one of the seven experts who had weighed in on his mental status, and the town librarian in Lincoln, Montana. She made a pilgrimage to Kaczynski's cabin in its new home in an airplane-hangar-turned-warehouse in Sacramento.. And she met with the defendant himself for 22 hours. Then she wrote a 47-page, single-spaced report that concluded, provisionally, that Kaczynski was a paranoid schizophrenia.

This in itself was nothing new; it had been the conclusion of all the other doctors, but they had had to coax the diagnosis either out of Kaczynski's known history or his current orneriness. They had, for instance, taken the fact that he used his own composted shit to ,fertilize his garden (a practice not quite so unusual as it sounds; there's even a name for it: humanure) as evidence that he suffered from "coprophilia," an unhealthy interest in feces. His hardscrabble, third-world life showed a lack of self-care. And his failure to accept that he was trµly deranged was "anosognosia," the condition of being too sick to agree with the psychiatrist, a hallmark feature of schizophrenia, and a word to bear in mind the next time you disagree with a psychiatrist. But Johnson needed to do no diagnostic conjuring. In 22 hours, she had taken the measure of the man, gotten a full frontal view of the Unabomber, and she'd concluded that he was reaHy and truly crazy, at least provisionally.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association, which is a sort of Audubon Field Guide to human foibles, is very clear that paranoid schizophrenia is not just one of those diagnoses you send in to the insurance company to ensure reimbursement. It's really not enough simply to think psychiatrists are the enemy, at east not in the current edition. You also have to have delusions, and Johnson thought she had found them, as she wrote toward the end of her report:

In Mr. Kaczynski's case, the symptom presentation involves preoccupation with two principle [sic] delusional beliefs. A delusion is defined as a false belief based on incorrect inference about external reality that is firmly sustained despite what all most [sic] everyone else believes, and despite what constitutes incontrovertible evidence to the contrary.... [I]t appears that in the middle to late 1960s he experienced the onset of delusional thinking involving being controlled by modem technology. He subsequently developed another strong belief that his dysfunction in life, particularly his inability to establish a relationship with a female, was directly the result of extreme psychological verbal abuse by his parents. These ideas were embraced and embellished, and day-to-day behaviors and observations became incorporated into these ideas, which served to further strengthen Mr. Kaczynski's investment in these beliefs.

So here was the final proof that Kaczynski was crazy: he thought technology controlled his life, and he believed that his parents had made mistakes that had made his life miserable.

As delusions go, these are problematic. Technology surely mediates our lives, even if it does not control them outright. And the question of parental abuse is an epistemological black hole. Rarely, if ever, does a therapist get corroboration (or incontrovertible contradiction) of a client's claim that he or she was subjected to bad parenting. Indeed, it is often the case that therapists "help" their skeptical clients to see that they were abused.

Dr. Johnson would have had a partial answer to these objections: it wasn't what Kaczynski believed so much as the tenacity of his belief that was troublesome. Try as she might, she couldn't persuade him of the folly of either of his "delusions." "When challenged on the initial premise [of either belief}," she wrote, "he appeared perplexed and it was evident that he did not challenge the belief system on his own regardless of existing evidence." Even worse, "he does not challenge {his beliefs} in response to new information."

Johnson promised to give Kaczynski her notes from their interviews but never did. That's too bad, because it would be interesting to see just how this conversation between two people who disagreed on basic premises went. One thing is clear, though: there was no way for Kaczynski to respond (other than agreeing with Dr. Johnson that technology wasn't such a bad thing and that his family was functional) that would not reinforce his diagnosis. What the psychiatrist overlooked, however, was that by her logic - in which their disagreement was about not politics, but reality itself- one of them had to be crazy. But it might not have been Kaczynski.

So Kaczynski was found guilty of schizophrenia, but still competent to stand trial, which meant that he was competent to defend himself. But Judge Burrell, whose knickers had been twisted by this mathematician's unassailable logic and dogged insistence on obtaining the protections of the system he hated, played his last card. When he denied Kaczynski's motion to represent himself, Burrell made no use of Johnson's report; he simply ruled that the motion had come too l te," even if Kaczynski had repeatedly indicated that he was ready to proceed immediately. He had to go through with his lawyers' defense.

Kaczynski had been bamboozled. Now he had the worst of both worlds: the psychiatric exam he had never wanted, and the certain prospect of hearing its findings reiterated in open court. He felt he had no choice but to plead guilty. Again, from his appeal:

After Judge Burrell's ruling, Kaczynski had to choose one of two alternatives. He had to either accept the plea bargain, or allow Denvir and Clarke to begin immediately their portrayal of him as a grotesque and repellent lunatic. With extreme reluctance, Kaczynski chose the plea bargain.

Five months after he made this choice, when Kaczynski got my paper on the bankruptcy of psychiatric diagnosis, he must have thought that even if I didn't already know all that had happened to him, I would probably understand and believe him when he said he'd been bushwhacked. That might be why he wrote me a 20-page letter in response. There was someone inside the industry who wouldn't chink he was crazy simply because he didn't like psychiatry. He must have figured he could use such a person, and he turned out to be right.

III. The Franchiser.

SO WHAT'S A NICE GUY like me doing with the Unabomber for a pen pal? If, as Kaczynski himself once asked me, I objected to his diagnosis, why not just write a paper for some professional journal and be done with it? Why cultivate a relationship with him? These questions should come up with any journalistic foray into another person's life, but because Kaczynski is a killer, they require answers.

One answer is that we had some common interests: we'd both lived in cabins without modern conveniences, shaken our fists at airplanes, and read Jacques Ellul. That's what I explained in my first letter to Kaczynski. But there was something else we had in common, something I'd left unsaid: Both of us wanted to get published.

Is this too glib? Perhaps, but surely there's no author or aspiring author who didn't recognize Kaczynski's wish to be heard and resonate with its desperation. No over-the-ransom prayers or letters to agents or walls plastered with terse rejections. He got what hardly anyone gets, let alone someone who lives in the woods: a virtual power lunch with Katharine Graham and Arthur Sulzberger. It's a comment on many things other than Ted Kaczynski's character that a person goes to such great lengths to achieve such ends.

But more was at work here than a grudging respect, something more personal: he'd run some serious interference for me, clearing an opening at exactly the time I was figuring out how the game was played. Just before his trial began, and before I sent my first letter to Kaczynski, my own book proposal, submitted in the normal way, had been rejected. The book was going to be called either Is Your Bathroom Breeding Drug Users? or Oxygen Was My Gateway Drug. My plan was to report on the cultural side of t:he drug war, all those Just Say No posters,

D.A.R.E. classrooms, and drug-free workplace initiatives deployed in the battle to convince the citizenry that it's in their best interests to stay off drugs other than nicotine, caffeine, alcohol, and Prozac. I was going to go behind enemy lines, as it were, talk about how this war machine looked to one of its targets. A major publishing house agreed to consider it.

My agent delivered the news. "They think it's a really good idea. But the first thing someone is going to do in a bookstore is look at the cover and say, 'Who is this guy? Why should I listen to him?' Gary, You just don't have a name."

"But that's the point," I said. "The book is about what happens when a guy no one knows starts to poke around in big things. It's an Everyman thing. Think," I said, imagining how a real writer would pitch it, "Michael Moore on drugs." I winced at the inadvertent (and unappealing) double entendre, and decided to tack.

"Well, what do I do to get a name?"

"Just get an article published in Rolling Stone or somewhere like thar. The Wall Street journal, Playboy- al\ywhere really. Except High Times. Don't get published in High Times."

The funny thing is that she ,was serious. I hung up. And I swear this really happened: the words came to my mouth. "You want a name?" I said to the phone. "How about Ted Kaczynski?"

Stanley Elkin, who never quite got himself a name, wrote a novel called The Franchiser about a man who gains a strange inheritance from his wealthy godfather. He is given the right to borrow money at the prime rate in perpetuity. This lucky legatee, Ben Flesh by name, uses the leverage to buy franchises: Burger Kings, Travel Inns, Texaco service stations, all the roadside's hideous familiarity. He spends his days driving from one franchise to another, a man with nothing but names, none of which is his own and all of which he owns. It's a Great American Novel.

Elkin recognized the peculiar genius of franchising: you don't buy anything but a name, and then you are simulraneously made someone and freed from the burdens of actually being anyone. So when Michael Jordan, announcing his retirement, referred to himself as "Michael Jordan," or when Bob Dole, running for President, referred to himself as "Bob Dole," it wasn't some kind of identity problem or rhetorical affectation; it was the exercise of the franchisee's greatest privilege: to trumpet a name that means so much to so many.

So I was going to try to get a name like Elkin's franchiser did: by going out into the marketplace and procuring one, which in this case meant convincing the owner to sell it.

As names go, Ted Kaczynski was not without its burdens. This man had, after all, killed people in a most terrifying way, people who were doing nothing more than sitting down to open their mail. Surely, I could find a name with less opprobrium attached.

But I recognized something familiar in Kaczynski's antimodern, anti-technology politics. In his pamphleteer style, he had written about things I'd studied and written about in my academic career: notably, that technology wasn't simply an assemblage of cools that awaited our use, wise or foolish. Rather, technology was a way of being in the world, one with some very peculiar psychological characteristics and social consequences. For, as various philosophers and novelists had been pointing out for some 200 years, it seemed to leave us fully aware of, but unable to do anything about, the way our devices alienated us from each other and the natural world, and, more to the point, threatened great peril.

The problem, in Kaczynski's view, was that technology had a life of its own, because technical progress had trumped all other possible ends to which humanity might be put. He made the point this way in "Industrial Society and its Future," better known as the Unabomber Manifesto.

The system does not and cannot exist to satisfy human needs. Instead, it is human behavior that has to be modified to fit the needs of the system. This has nothing to do with the political or social ideology that may pretend to guide the technological system. It is the fault of technology, because the system is guided not by ideology but by technical necessity. Of course the system does satisfy many human needs, but generally speaking it does this only to the extent that it is to the advantage of the system to do it. It is the needs of the system that e paramount, not those of the human being.

The worst of it, according to the Manifesto, was that technology didn't take away our freedom forcibly, in a manner that would have us up in arms like the villagers in Frankenstein. Rather, enchanted by its near-magic powers, we had become collaborators in our own enslavement:

When skilled workers are put out of a job by technical advances and have to undergo "retraining," no one asks whether it is humiliating for them to be pushed around in this way. It is simply taken for granted that everyone must bow to technical necessity and for good reason: If human needs were put before technical necessity there would be economic problems, unemployment, shortages or worse. The concept of "mental health" in our society is defined largely by the extent to which an individual behaves in accord with the needs of the system and does so without showing signs of stress.

None of this was original to Kaczynski, although it had probably never appeared in The Washington Post before. The Industrial Revolution has always had its naysayers, artists and philosophers and social theorists who question what it is doing to us. Crucial among these questions, at least for a psychologist, is how we manage to be shaped by technology without either knowing it or being able to do anything about it. William Blake, an early antimodernist, captured this process with his image of "mind-forged manacles," shackles that are so compelling and comfortable that they become undetectable, and show up only obliquely, as symptom. That's the job of the therapist: to come along and reveal to a person the way they are, without knowing it, imprisoned by their own unacknowledged history. But some cases of self-imprisonment are harder to understand and point out than others. And the one that Kaczynski noted is perhaps the hardest of all. Technology not only helps us to accomplish things, with the occasional failure or accident or frustration; it also constructs us as the kind of people who are hard-pressed to be sufficiently critical of technology.

Perhaps the mental health industry, as Kaczynski implied, is inescapably another of the sorcerer's apprentices. That's one way to explain the difficulty of understanding, at least in psychological terms, this central mystery of technology, the way it seems to keep us blind to itself. But the fact is that no one really understands how we can listen to another report about the greenhouse effect even as we drive our cars, festooned with "Save The Earth" bumper stickers, to fetch a loaf of bread. No one really knows how we sustain this level of what psychologists call cognitive dissonance or why we barely perceive it. Neither can anyone explain why we are not wracked by guilt and anxiety or at least repelled by our own bad faith. And because we (psychologists, that is) don't really understand these things, we can't do anything about them) even if we want to. Such has always been the problem with thoroughgoing indictments of modernity: they're long on critique and short on solution.

The Manifesto's proposed therapy parted ways with this aspect of antimodernism:

The only way out is to dispense with the industrial-technological system altogether. This implies revolution, not necessarily an armed uprising, but certainly a radical and fundamental change in the nature of society.

And it offered a very loose treatment plan.

It would be better to dump the whole stinking system and take the consequences.

My philosophical kinship with Kaczynski - in which I don't think I was by any means alone; as Robert Wright wrote in Time, "There's a little bit of the Unabomber in most of us" - stopped short of this let-the-chips-fall confidence. I like the fact that I don't have to worry about getting smallpox, and I'm not quice willing to s y that the whole system ought to be jettisoned) or the citizenry rallied to arms by random violence, as Kaczynski evidently wanted.

But the face that he was a killer perhaps only increased my interest. Was it possible that Kaczynski's moral depravity was understandable as the snapping of a weak link in a chain pulled too right? Was it possible that his terrorism was only the leading edge of a series of even more desperate aces to come as that cognitive dissonance came to be less and less tolerable? That his very character seemed to bear the imprint of large social and historical forces, that he seemed to know what those forces were, and that he was very, very famous - all this made the franchise irresistible, despite my squeamishness.

But there was a problem even beyond the obvious ethical one: in the public eye, Kaczynski had only been a political figure for a blink. Quickly, as William Glaberson of The New York Times reported, he'd been transformed into a pathetic lunatic.

It seems hard to believe now, but it wasn't very long ago that the Unabomber seemed like a serious person. To read about him in many newspaper and magazine accounts was to hear of a mysterious philosopher: dangerous yet compelling, brilliant, intriguing. Yes, he was troubled, even evil - but he was a man of ideas.

Now he's just a nut. Or, perhaps worse, a fraud.

Glaberson reviewed "scores" of articles and TV news accounts to chronicle this shift, singling out The Washington Post and The Los Angeles Times (and leaving out his own paper, which had undoubtedly known all along that the guy was a sandwich short of the whole picnic) for their about-faces. He got professional counterculturist Todd Gitlin to explain the Kaczynski jokes:

In many of the jokes, the Unabomber seems "pathetic more than evil," said Professor Gitlin.

It may be that the humor comes from a deep fear of the harm that a disturbed criminal can do. "There is something that is very difficult for society to confront, and that is that crazy people have the means to do damage," Professor Gitlin said. "If you think of him as a joke, then you don't have to confront that He has become shtick."

Environmental terrorist to madman-bomber to punchline: the metamorphosis is so complete that Gitlin forgot that Kaczynski started out as something even more scary than a disturbed criminal.

Celebrity culture doesn't just hand out names for free. Kaczynski, having gotten famous (and published) by unsanctioned means, had to pay the price. He couldn't be forgotten, and he certainly couldn't be bought our of his beliefs. So he had to be turned into kitsch. And, to make things worse, his fashioning as a pop-culture trinket was largely brought about by his own lawyers, at least according to Glaberson:

The shift in public image which began with Mr. Kaczynski 's arrest for carrying out an 18-year campaign of bombings that killed 3 and injured 28, accelerated after his lawyers said he was a delusional paranoid schizophrenic who believes people have electrodes implanted in their brains.

To keep Kaczynski safe for democracy, his license to seriousness had to be revoked. If he's crazy, after all, then he can be famous without being meaningful, his unsettling denunciation of modern technology reduced to the entertainment of a lunatic's raving.

And who, besides the lawyers, was responsible for this outcome, this down-the-rabbit-hole reversal of logic whereby a rational, if contentious, belief- thar there's something wrong with the way technology has colonized our landscapes, both interior and exterior - becomes the mark of insanity? Therapists, of course, the people trusted, for no particularly good reason, with the authority to decide who is a genuine apostate and who is just plain nuts, whom we should listen to and whom we can dismiss. The first person who might have predicted this outcome was Kaczynski himself, who worried a lot more about therapists' inability to distinguish pathology from dissent than about their implanting electrodes in his brain. The culture indulged his anxiety, and its agents were my own colleagues.

In the end, I'd just as soon forgo franchising and stick with my own name. But Ted Kaczynski - the antimodernist, cabin-dwelling, diagnostically labeled, famous murderer/writer with a cause - that name was the next best thing, a name I could use without too much misgiving at the fact that I was a user.

Does this mean that I am guilty of exploitation with intent? In trying to explain how his identity was constructed by the mass media, Kaczynski and I corresponded about Ja er Malcolm's famous passage in The Journalist and the Murderer: "Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to' notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible." Malcolm, who has turned self-reflection into a writing style that defies Zeno's paradox, is getting at the way that all journalists must be franchise-seekers and thus must use others for their own gain. Some writers, like Malcolm, manage to franchise themselves; others get their name recognition from the journals they write for; but the rest of us don't have these luxuries. The writer must be determined in his attempt to get the other to give him a name, particularly. when his subject is not for sale.

I never hid my ambition from Kaczynski, never claimed that I was in it solely for the intellectual stimulation or to make the world a better place. As our correspondence unfolded in August and September, he often asked me why I was so interested in him and his case. So I wrote to him about my ambition and my misgivings about my ambition:

My wanting to write about you... is, after all, an act of appropriation; I am seeking to take something from you and weave it into something of mine Much as I might not want to, I must admit to being among those who want to get in on the ground floor with you. I have certain aspirations as a writer and a commentator on modem mental health practice, and getting to know you serves them. I don't know how this makes you feel (although I'd be glad to hear), but it would be disingenuous of me to claim this was not the case. All I can do is try very hard to make sure that my aspirations do not lead me to exploit or otherwise hurt you....

I don't know if I would have been so honest had I not figured Kaczynski for someone exquisitely sensitive to being manipulated. Here is the truth of what Malcolm says. Ir is impossible even for me - the agent of these words and acts -- to say if my honesty was in service of the Right and the Good, or if it was just another sales pitch. In fact, it's hard to say if this kind of confession without absolution is cheap or noble or just superstitious: if I'm only frank enough about my sins, then I can continue to get away with them.

That's why later on, when another of Kaczynski's associates called me a fibber, I didn't object. Somehow, I thought he had a point.

But I'm not sure that honesty, even for the best reasons, is a good moral defense. I mean, there I was worrying about how it made the Unabomber feel that I might be exploiting him, confessing my wish to appropriate his story to a man who had appropriated the very lives of other people. Either I'm casting scruples before swine or turning the truth into a shill.

In the end, it's hard to know if the wish to be heard is about the message more than being the famous messenger. We know ourselves too well to parse motive. Honesty just isn't up to the job.

IV. A Brief History of the U.S. Postal Service.

OR MAYBE MOTIVE is simple to understand, as simple as an explosion.

Terrorism, after all, is about finding the fulcrum. The terrorist takes a little powder and salt and places it in the best possible proximity to the place where things pivot, thus turning his marginality to Archimedean advantage. leverage is a form of laziness, really.

The postal service was Kaczynski's ultimate and best fulcrum. It wasn't enough to leave bombs in parking lots and university labs, as he had in the early stages of his terror campaign. Even when a Sacramento businessman, apparently clearing away a bomb disguised as a road hazard to spare someone else a flat cire, was killed, it didn't, perhaps, attract a concerted enough focus. This may be because altruism is not a critical pivot point of our society. That someone got killed when he stopped minding his own business might inspire as much contempt for him as fear for ourselves.

But the postal service, that's something else entirely. It's the most primitive and venerable of the ligatures that hold us together. The engineers of our republic were so convinced of the importance of a trustworthy post to a functioning and cohesive society that they made its establishment an early order of business. The Continental Congress, in a symbolic shot across Britain's bow, appointed Benjamin Franklin to wrest the delivery of mail from the Redcoats in 1775. The Articles of Confederation put aside their fear of central government long enough to establish a national post office as a power superseding state control. And the Marshall Court's famous implied powers doctrine determined. that a post office was essential to Congress's ability to execute its Constitutional duties. Some people even think the post office was what made it possible to keep such far-flung territories as California on board with the rest of the Republic.

No doubt chis history, like most history, is far from the mind of millions of Americans opening their day's mail. And that's the point. No one wants to wonder if the next package is a bomb. All the protections implied in those ominous signs about tampering with the mail, in the inviolability of the envelope's seal, is evidence that Kaczynski indeed had found a pivot close to the heart of things.

The postal service was, in any event, a fitting way to communicate with a man who eschewed and hated modern technology, and who wrote very good letters to boot. I could communicate with all the other important people in my life face-to-face, or with the quick ease of email or telephone. But it took us 18 days, at a minimum, to accomplish one exchange of letters. An Express Mail letter could take as many as seven days to get from my post office to his cell. Much of the delay was easy to account for: letters had to be read going in and out, presumably to be certain that he and I weren't conspiring to commit mayhem. (Indeed, I often wondered what the readers made of our letters, which discussed everything; I think of them as the silent witnesses to our relationship.) But I always thought it was possible that the deliberate pace of our exchanges was the post office's means of revenge.

If that's true, then it's just more evidence that Kaczynski found the right fulcrum. This discovery, of course, is the terrorist's best hope. But, you may rightly wonder1 what did he want to do with his leverage? David Gelernter, whom the Unabomber maimed, has written of his be1ief that Kaczynski was just trying to find a way to get his name in lights the easy way. I think Gelernter’s at least half right. I don't believe chat Kaczynski really wanted to get famous or rich. But I do think he wanted badly to be herd, not only because he wanted to point out the disaster of what he called industrial society but because he knew that it was in the nature of that society to drown out a voice like his own. He knew he had no chance of having a voice through the conventional means, so he set out to cheat.

So there's your motive. Kaczynski had found a fulcrum. And he was going to be my lever.

V. The Mark of Zorro.

BUT WHAT ABOUT the rest of the letters? a reader must be asking at this point. My answer is, I'm getting there.

I'm not crying to be coy. It's just that the letters tell a story, but without their context, they are only pure commodity. I never said it straight out, but I'm sure I implied to Kaczynski that I wouldn't be so baldly exploitative, just as I'm sure I implied that I wouldn't quote from them without his permission. That's why, even though lawyers tell me I could make a case to do so, I've refrained; not only because, as one magazine editor put it to me, "He doesn't have much better to do than file lawsuits from prison," but because I have to live with myself.

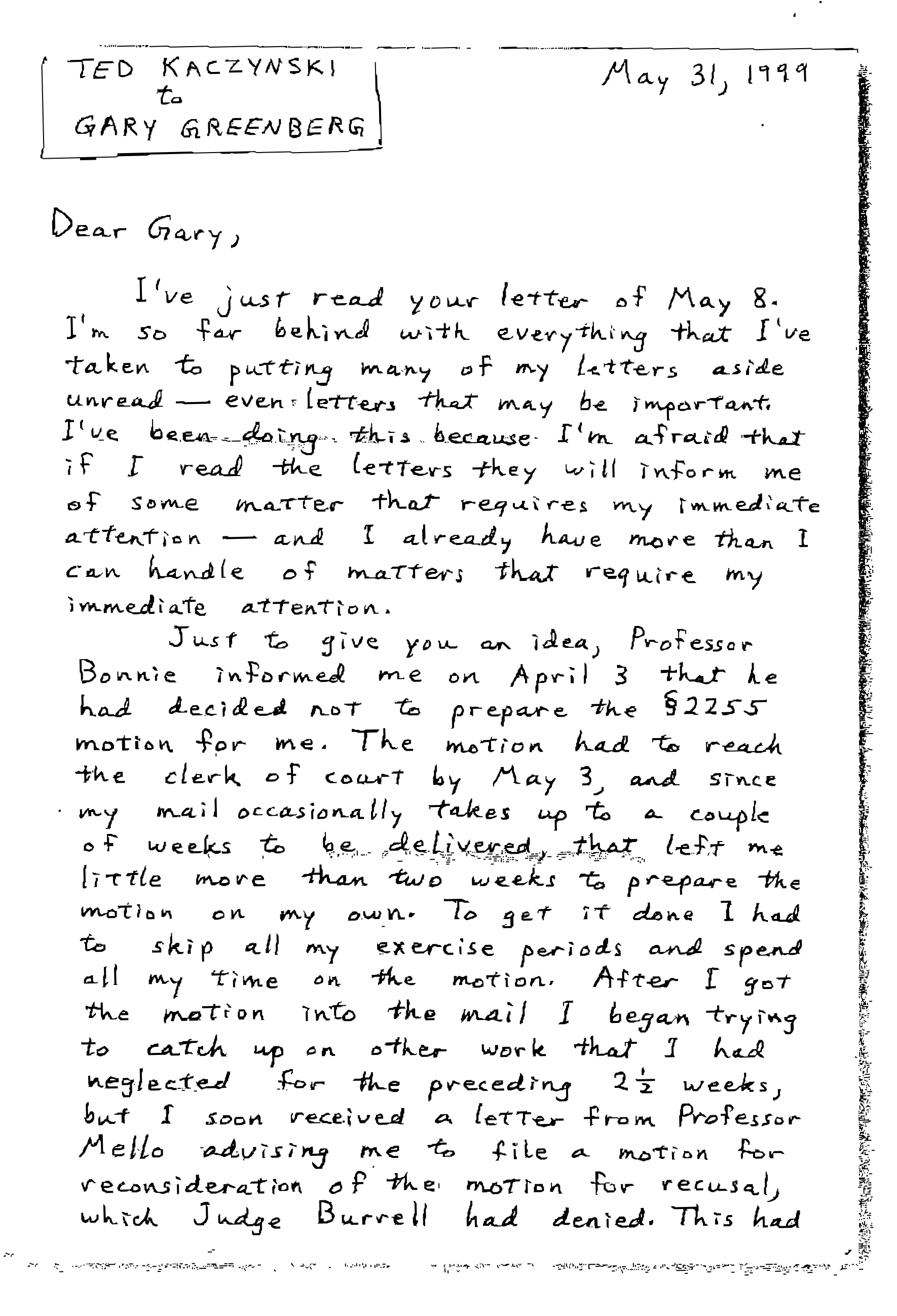

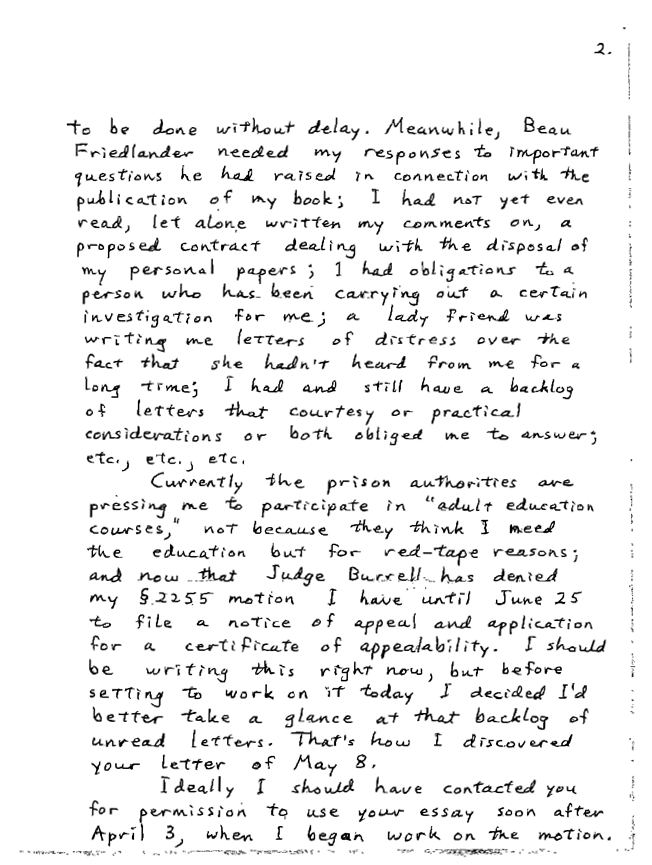

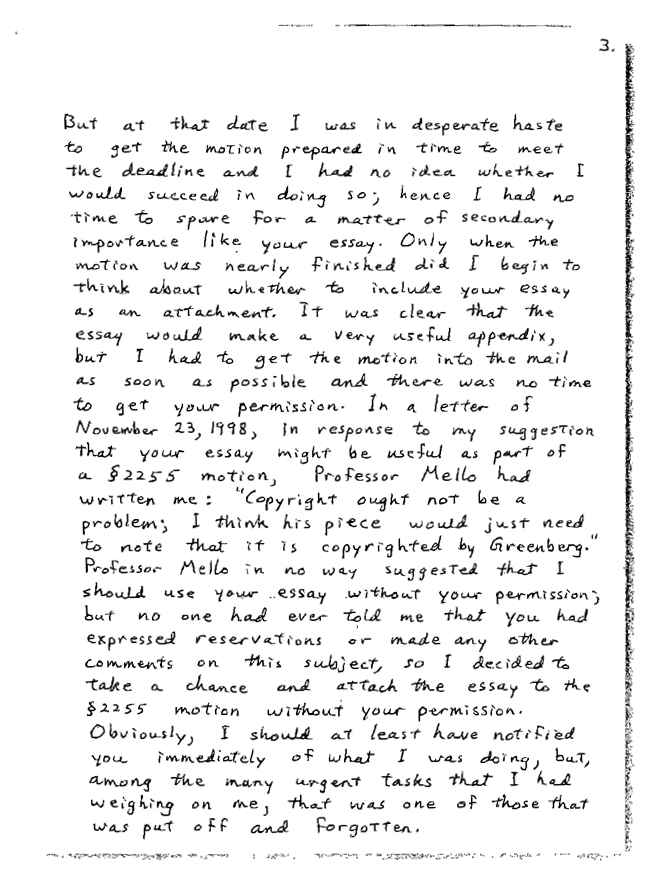

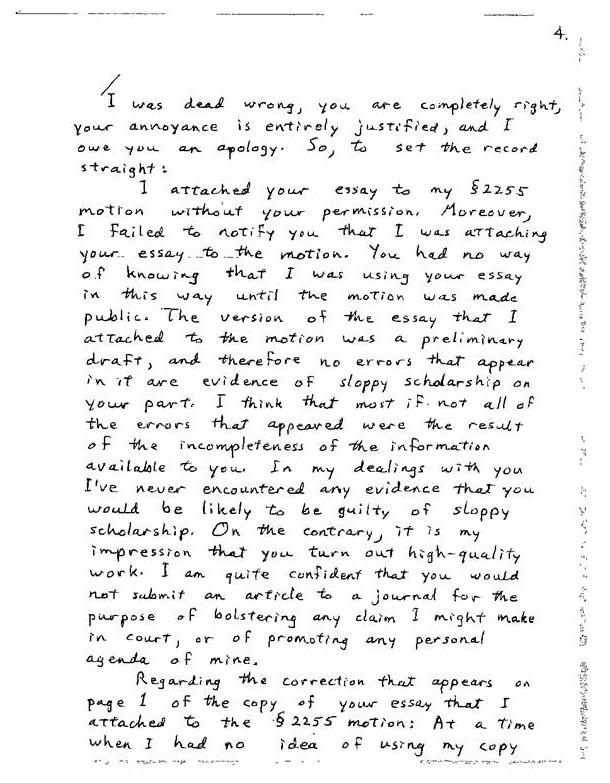

Fairness, though, demands and allows at least some description. There are 27 letters, a stack one inch thick. They date from June 9, 1998, to June 1, 1999. Twenty of them came between August 11 and December 11 of last year. They're on lined, usually white but occasionally yellow paper, mostly written in pen. Kaczynski's evenly spaced block letters are neat and unadorned. His left margin is ruler-straight, his right taken to the edge of the page unless tha.t would disrupt the orderly rhythm of his print. Perhaps Kaczynski's penmanship is his attempt to mimic his impounded typewriter, the one on which he wrote the Manifesto. Maybe he misses it.

Kaczynski's grammar and syntax are as precise as his handwriting. His carefully unbroken infinitives and faithfully maintained parallel structures read like examples from Strunk and White. I imagine sometimes a schoolboy's pride in following the rules, his relish of a job well done, lurking in all this compliance; Kaczynski's rebelliousness, his love of the wild, stops here.

In his letters, Kaczynski is sometimes pedantic and other times argumentative. But leavening them throughout, in addition to his unfailing politeness and moderation of tone, is a sense of humor that stops just short of wiseass. In this, he reminds me of a very smart adolescent boy whose sharp intellect and way with words can, if only momentarily, put his insecurity out of mind. In a word, Kaczynski's letters are jaunty, a quality that I don't have to quote in order to show. I just have to tell you that when he signs his name, he often underlines it with a scrawled "Z" that looks, for all the world, like the mark of Zorro.

VI. "He Probably Never Felt a Thing."

ONE LAST WORD on motive. The problem that grabbed my attention went way beyond Kaczynski's image. The real opportunity here, the one that made the franchise seem valuable to me, was to write about the way all things Unabomber had been fashioned. Kaczynski hadn't thrown a wrench into the machinery of mass culture so much as he had kicked it into high gear.

Take, for instance, the story of Hugh Scrurton, the man killed by a bomb Kaczynski left in a parking lot in Sacramento in December 1985. Here's how the Government Sentencing Memorandum describes the victim:

Friends recall Hugh as a man who embraced life, a gentle man with a sense of humor who had traveled around the world, climbed mountains, and studied languages. He cared about politics, was ''fair and kind" in business, and was remembered as ''straightforward, honest, and sincere." He left behind his mother, sister, family members, a girlfriend who loved him dearly, and a circle of friends and colleagues who respected and cared for him.

And here's Kaczynski's account of the killing, decoded by the Government and presented in the same memorandum.

Experiment 97. Dec. 11, 1985. I planted a bomb disguised to look like a scrap of lumber behind Rentech Computer Store in Sacramento. According to the San Francisco Examiner, Dec. 20, the "operator" (owner? manager?) of the store was killed, "blown to bits, on Dec. 12. Excellent. Humane way to eliminate somebody. He probably never felt a thing. 25,000 reward offered. Rather flattering.

The contrast couldn't be clearer. One man - chortling to himself in his ramshackle cabin - exults over having obliterated another - an honest, hardworking man who was performing what the sentencing memorandum called a "simple act of courtesy, trying to remove what looked like a potential hazard to others." It's effective rhetoric: no one can read this account and not be moved or think that the killer deserves to lose the same rights he stole from the victim.

But here's an interesting thing, one that tells us that more is at stake here than simple justice: The "act of courtesy" by which the Government said Scrutton was killed seems to be a fiction, one of those tales that gains its truth by some combination of plausibility and repetition, that takes hold because the cultural climate is just right for it. It's a little piece of mythic filigree that was added to the story slowly and imperceptibly over the 13 years between the murder and Kaczynski's sentencing.

Scrutton's violent and untimely end is awful enough, so awful, one might say, that it doesn't matter if the Good Samaritan story isn't precisely true. But by the same token, one might also reasonably wonder why and how the embellishment came about in the first place.

At first, the simple horror of the death could be conveyed in a workmanlike account like The Sacramento Bee's:

A Sacramento businessman was killed Wednesday when a bomb that had been left behind his store blew up in his face, authorities said.

The blast shortly after noon mortally wounded Hugh Campbell Scrutton, 38, owner of RenTech Computer Rentals in the Century Plaza shopping center...

The device exploded just moments after Scrutton left his store through the back door and headed for the parking lot, according to reports. The blast blew Scrutton about 10 feet.

The first person to arrive at the scene said Scrutton cried out, "Oh my God! Help me!"

Scrutton, of Carmichael, was pronounced dead at 12:34 p.m. at University Medical Center. He reportedly took the full force of the blast in his chest. There were no known witnesses.

Investigators placed the time of the blast at 12:04 p.m. They said Scrutton was on his way to the parking lot when, they believe, he spotted an object, which may not have been identifiable as a bomb.

[Sgt. Roger] Dickson said it appeared that Scrutton, who had only keys in one hand and a book in the other, may have leaned over to examine or move the object when it exploded. "The injuries were consistent with that kind of movement."

Eight days later, the Bee put a little more face on Scructon.

"Mr. Scrutton was an exemplary citizen with an unblemished character. I am certain that he was not a specific victim of the bomber," said Lt. Ray Biondi, head of the Sacramento County Sheriff's Department homicide bureau. "Anyone who happened by the business could well have been the victim."

Three months later, Scructon was still on Sacramento's mind - now as the victim of an unsolved crime. And, the Bee reported, he was still an exemplar.

"Hugh was the best boss I ever had," said a RenTech employee, who asked that his name not be printed. "He was an honest, kind person. And that really makes it harder, because it's such a shame when someone that nice is taken from you."

So far, the mythmaking is gentle and slow and almost invisible: a good and law-abiding man had gotten blown to pieces in a parking lot. Even unadorned, it shows us that the terrorist had found his pivot: The dead man could have been you or me.

By 1994, however, it began to seem that Scrutton's death was one in a series of bombings carried out by someone Playboy called "The Scariest Criminal in America." And suddenly, Scrutton had a motive:

It is five minutes before noon on December 11, 1985. Hugh Scrutton, 38 years old and single, opens the back door of his computer rental store in Sacramento and steps out into a bright day, where his death waits just a few feet away in a crumpled paper bag. Sunlight glints off the chrome of cars and pickups parked in the big asphalt lot that opens to the west. A 15-mile-per hour wind blows south off the eastern hip of California's Coastal Range and rattles the bag. Scrutton steps past it, then turns.

There are two Dumpsters right by the door, he thinks. Why do people do this? Jesus, just drop the damn thing in.Scrutton bends down and reaches for the bag with his right hand. There is no time to consider what happens next.

It's. hard to understand how a Playboy fact checker could fail to question a reporter's claim to know Scrutton's thoughts at the moment of his death. But the flourish of altruism, first spotted here, fits in, certainly better than if Playboy had had Scrutton seized by a need to keep his parking lot clean or a hope that the bag contained cash. Scrutton isn't quite yet the Good Samaritan, but he is good enough to hate litter. He may be better than you or me.

The embellishment was soon an integral part of Scrutton's story. The month after the Playboy article appeared, Thomas Mosser, a New Jersey advertising executive was killed by a bomb in his home. Mosser's death was almost immediately identified as another in the series, and Newsday reviewed the earlier victims, including Scrutton.

Hugh Campbell Scrutton walked out the back door of his RenTech computer rental store. He bent down to clear what looked like clutter, about two feet from the door.

Sgt. Dickson's 1985 speculation has now become a fact, even for the paper that initially reported it as a theory: "Scrutton ... bent to pick up what appeared t0 be a pile of litter," the Bee reported in November, 1997. He didn't just trip on or idly kick the bomb. He had a motive, one that, six months later, became part of the United States Government's official story about Hugh Scrutton.

Robert Graysmith's true-crime book, Unabomher: A Desire to Kill, gives us this version of the Good Samaritan story:

On December 11, 1985, only two weeks before Christmas, Scrutton got up from his desk and made ready for a lunchtime appointment.... He opened the rear door of his store and looked out upon a windswept parking lot in the strip mall and pulled up his collar. Near a Dumpster he saw a block of wood about four inches high and a foot long. There were sharp nails protruding from the block, a road hazard or, even worse, a real danger to the trash men or the transient who occasionally came by to pick through the Dumpsters. He bent over to move it. It was heavy. Lead weights had been inserted in the lower two inches of the block.

Graysmith's rhetorical economy here is remarkable, each image used for all it is worth and then some. Bums and trash men in need of the protection of a hardworking businessman, an inhospitable parking lot, a lead-heavy road hazard (not just trash, but dangerous and inconvenient trash), the now-famous wind, and, serendipity for the storyteller, Christmas. Graysmith hardly needs to take up residence in Scrutton's blasted life to venture this explanation. He just needs to know his audience.

Decorated as a Good Samaritan, the innocent but hapless bystander takes on the glow of decent people's highest aspirations. It's not enough to vilify the bomber simply for murdering someone or to appeal to the usual explanations -- passion or dementia, revenge or hatred - to account for Scrutton's death. Because these are political crimes. The Unabomber was a subversive, in the most elemental sense of the word. He wanted to turn things upside down. What kept Industrial Society going, in his view, was a belief in technology that amounted to a dangerous delusion. And he wanted to disabuse the rest of us of our illusion by blowing up whichever you or me kicked or tripped on or tried to steal or safely discard the parking-lot bomb. Not because he was crazy or randomly depraved, but because he believed something that was at least coherent.

And that's why Scrutton's story had to be adorned, why he couldn't be left as the victim of random cruelty. At stake, after all, is this central problem of modern life: that we pursue and sometimes achieve happiness with such blithe disregard for consequence. The filigree tells us just what terrible kind of monster Kaczynski is: the kind that would kill an altruist.

VII. The Plea Bargain.

BUT IF KACZYNSKI was so bad, then why was his plea bargain - which, after all, ensured that he would not be put to death - met with such relief? Why was George Will left to weigh in virtually alone with his thin-lipped outrage at a society too namby-pamby to strap a convicted murderer to a gurney and shoot him up with lethal drugs?

The editorial pages, which from coast-to-coast declared justice the victor, had their own explanation, perhaps best summed up by The Los Angeles Times.

With Kaczynski's guilty plea, the victims, the nation and federal prosecutors should gain some satisfaction. His admission that he committed these horrific crimes should bring a measure of solace to the Unabomber's surviving victims and the families of victims. His incarceration ... will keep him safely locked away for life. Moreover, federal prosecutors and taxpayers save the millions of dollars a Sacramento trial and, later, a federal trial ... would have cost.

In management-consultant parlance, it was a win-win deal. The defense lawyers had saved their client's life, despite overwhelming evidence that he had murdered with malicious intent. The prosecution had avoided uncomfortable questions about the FBI crime lab's work in the case and the legality of the search of Kaczynski 's cabin. David Kaczynski, the Unabomber's brother, who had turned him in only after the Government assured him they would not seek the death penalty, had been spared the mark of Cain.

But, as with Scrutron's altruism, there's more to this story, something first made clear by William Finnegan, reporter for The New Yorker and author of the most perspicuous account of the trial's abrupt end. Behind the Kaczynski trial, he said, lurked the O.J. trial. In his view, the most relieved party was the presiding judge, Garland Burrell, who had sidestepped the shit that his colleague Lance Ito was still scraping off his shoes. The ill-fitting glove, the lying detective with an interest in screenplays, the race card, the strange coincidence of a dog and a houseboy both named Kato - these icons of humiliated justice would be denied their Unabomber equivalents.

The Sacramento Bee, the hometown paper, recognized this motive. The Bee, presumably read by people close to the victims (not to mention the disappointed restaurateurs and hoteliers, the street vendors and cab drivers who had watched the O.J. trials and anticipated the arrival of the medicine show to their Main Street), had to explain the whimpering ending with something less abstract than justice. After reciting all the winners and remarking that closure had been achieved, the Bee drew a bead on another thought.

In addition, this result avoids the spectacle of having the government prosecute an obviously deranged defendant or - worse yet - watching him meander through reality attempting to defend himself.

Although judged competent to stand trial, it has become increasingly evident that Kaczynski is greatly disturbed. His behavior, the contentions of his lawyers and the diagnosis of a respected government psychiatrist have made that clear. No good would be served by the circus that his trial could so easily have become, that could only have brought disrepute on the process.

The New York Times also noted that "Mr. Kaczynski's mental illness threatened to disrupt the progress of any trial," turning it into what The New York Post worried could only be a "distasteful spectacle." Even Butch Gehring, described by The San Francisco Chronicle as "the closest thing Kaczynski had to a friend in Lincoln, Montana," had '"worried that [Kaczynski] was going to turn this into a weird sideshow, and that wouldn't have been good for anyone."' The Unabomber trial had packed its tents and gone, and the citizenry was safe from its freaks and barkers, and, most of all, its deranged ringmaster.

Listening to these protests over the degradation of public discourse and of the otherwise reputable justice system, you have to wonder whose satellite dishes those were outside Ito's courtroom, who wrote all those front-page headlines, who dispatched an army of America's reporters to broadcast each evening's lead live from Los Angeles in the first place. Did the unanimous consent to the Kaczynski verdict signal the newsies' own shame at what had just unfolded? Or were they simply relieved that temptation too great to pass up - a cold-blooded murderer meandering his way through reality just can't be bad for ratings - had been removed from their reach?

Of course, it's also possible that the production values of this spectacle were all wrong. The O.J. trial had so many things going for it: a well-dressed celebrity defendant, colorful lawyers, a media-friendly judge, the Hollywood backdrop. All the players seemed to know their parts. And the "deep cultural issues" reiterated as the excuse for carpet-bombing America with OJ. news - domestic violence, the cost of a good legal defense, racism - were perfect for a viewership desperately in. need of reassurance that all these hours of watching and talking and reading about it were something more than shallow self-indulgence. These themes could be endlessly indulged without anything important ever getting said or anyone important ever changing anything.

But Kaczynski took control of his own spectacle, made life impossible for the scriptwriters. Even after he was put in jail, he eluded capture by headline and soundbite. Every time the posse caught up with him, he beat it cross-country and left a cold trail. Was he the pedantic pamphleteer? The Last Honest Man, holding out for a world safe for spotted owls and self-reliance? The supremely confident terrorist? The brilliant but troubled recluse? The paranoid schizophrenic who had judges and lawyers (and reporters) chasing their own tails? One-and-a-half years after his arrest, they still didn't have him figured out.

Kaczynski's ability to keep everyone guessing should not have come as a surprise. He was, after all, an expert at finding the fulcrum, measuring the exact length of the lever necessary to get the job done. He'd gotten America's newspapers of record - papers that are generally very clear about what and whom they publish - to print> at their own expense, a 35,000-word manuscript that systematically denounced everything they stood for. And if the events leading up to the plea bargain were any indication, this prank was small potatoes compared with the havoc this man could wreak if he got the whole apparatus of spectacle under his control. No wonder they were relieved.

VIII. In Which the Author Discovers That 'the Unabomber is a Complicated Man.

JULY AND EARLY AUGUST brought more letters. They took a surprising and unsettling tum toward the personal, at least insofar as we seemed to be searching for common ground.

This wasn't all that hard to find. Partly that was because certain subjects were off-limits, notably anything to do with the Unabomber crimes. Kaczynski had made it clear from the beginning that he wasn't going to put anything in writing that affirmed his guilt, as all he had really done at his plea bargain was to concede that the Government was probably going to win its case. He needed to keep his options open for a possible appeal.

So we discussed our mutual interests' - back-co-the-land living, the politics of psychiatry, books. Kaczynski asked me to send him a book, Ecoterror, by Ron Arnold, free marketeer. The book linked the Unabomber and. Earth First! terrorism to Al Gore's wonky environmentalism, arguing that all this concern with spotted owls and old-growth redwoods was just cover for people too faithless to place their fate (and that of the earth) in the care of the "invisible hand." I thought the book might make Kaczynski angry, and I told him so (wondering what an angry Kaczynski would be like in writing), but he surprised me by saying that he liked it quite a bit, because it polarized issues, and without polarization, revolutionary change just can't happen. This had been one of the Unabomber Manifesto’s first points: that liberal politics were bound to fail to reform anything because Leftists were too busy being nice. Kaczynski liked the trenchant tone of Arnold's argument: he recognized him as a fellow polemicist.

Kaczynski's letters were dense, carefully argued, and full of promise. He stopped short of saying he'd cooperate with me in writing his biography, but he was clearly willing to discuss the matter. Even more promising, he had told me I could come to visit him, although, as I found out in early August, he was currently unable to get his visitor's list approved by the prison.

I spent a good part of the summer getting to know the Unabomber. I was trying to convince him that I was a worthy writer and interlocutor, someone he'd be wise to trust his life story ro. But I was also interested in a way I had not anticipated: Kaczynski's thinking was careful and calm and deep, and his material ranged from Russian history to Hobbes' Leviathan to Desmond Morris. He pulled out obscure facts from his mental archive - telling me once, for instance, that he didn't bathe very often when he lived in Montana, but that bathing wasn't all it was cracked up to be, and in fact there was a law on the books in Indiana (he thought) that made it a crime to bathe in the wincer, which Kaczynski thought meant that pneumonia was more of a problem than body odor. (He often apologized if he couldn't cite sources, but I never thought he was making this stuff up.)

Although I resisted treating Kaczynski as a case study, I couldn't help but make some clinical observations about him. I was discovering that he was just as complicated and full of self-contradiction as the rest of us. While he tried to live a life of complete consistency between his beliefs and his actions, in some ways he embodied the biggest opposition of all. He was at once a mathematician, a man of science, entirely convinced of reason's superordinance as a means of negotiating the world, and at the same time a savage critic of rationality's greatest achievement: technology. It's impossible to divorce Descartes's ego cogitating its way to certainty from Henry Ford's Model T slipping down the conveyor belt - both grow from the desire to hold the world firmly in our grasp, to make it yield to us. Most of us see the resulting, nest-fouling problem. Kaczynski saw it too, but he seemed unable to turn this infinite loop of alienation into the wry irony the rest of us are so good at. It just pissed him off.

A differently constituted man might find the tension of being stretched across this great rife of modernity unbearable. Perhaps this is why the psychiatrists who evaluated him found him to be schizophrenic even though, at least in their presence, he never behaved like a schizophrenic. Maybe they divined the desperate, irreconcilable conflict in his politics, and concluded that a man unable to gloss over this problem like the rest of us ought to be crazy.

That's as far as my clinical speculation went. And though I'd known going in that I wasn't courting Kaczynski as fodder for some pet theory of mine, I wasn't prepared when I discovered that, instead, I was beginning to like him.

That didn't mean, however, that he couldn't be difficult.

I wasn't the only person who wanted to get to know the Unabomber. Kaczynski complained throughout the summer about all his correspondents and the inefficiencies they caused him. So in August, he decided to do something abo\lt it: he introduced us to one another. His idea was that we would cooperate, stop asking him the same questions separately and help him to cut down on his workload. We were to share his letters among ourselves, garnering more information than we would individually. He wanted to hold a slow-motion press conference.

I did wonder what else a man kept in a prison cell 23 hours a day had to do. But the letters were clearly labor-intensive - long, interesting, and handwritten with no sign of revision. Either thoughts sprang fully formed from his head to the page or he was drafting multiple attempts. I wouldn't have minded a scratch-out here, a logical slip there, but this would have been intolerable for him. He was, after all, the man who complained to his journal about all the time and trouble he had to go to in order to perfect his bomb-building techniques. Human frailty, at least the variety revealed in failed bomb experiments or poorly turned phrases, was an abomination to him. Better to wrangle us than his own perfectionism.

His method for winnowing his workload was, well, methodical. He divided his correspondents into groups and wrote a letter to each group introducing its members to one another and urging them to work together. (He cc'd the letters and was perhaps the last man in the industrialized world who used actual carbon paper to do so.) Kaczynski divided us into three phyla. First, the authors: Vermont Law School professor Michael Mello, and Montana-based writer Alston Chase, and me. Next, the social theorists, the people who wanted to talk about the Unabomber's ideas: Russell Errett, Derrick Jensen, and me. And finally, the shrinks who wanted to explain the Unabomber to the world: a forensic psychiatrist and me. I didn't know exactly what to make of my inclusion in three groups, but I took it as a good sign.

What I did know was that, like much of what Kaczynski did, this act was at once strange and reasonable, obnoxious and considerate, obtuse and clever, naive and subversive. It was, at one level, all pure and equal exchange: we would get more bang for our 32 cents and he would get relief from his writer's cramp and crowded calendar. Didn't that make sense? At another level, it was revolutionary, detesting competition itself and maybe building anti industrial cadres in the bargain.

But what kind of self-respecting writer lets others ask his questions? What kind of entrepreneur cooperates with others? We all wanted to tap the Unabomber's well, and he wanted us to share. More to the point, he thought one of us was just as good as the next. His was a kingdom of equals in which no one had a unique claim on his attention. It's a stunning appraisal: that a group of people full enough of themselves to think they could consort with this icon of monstrosity could cooperate in this fashion simply because Kaczynski had determined that it made sense to do so. Even more stunning, though, was that no one appeared to object to the terms.

Because what are you going to do when you want something badly from someone? There's only one Unabomber, and he knew it. His move may have reflected his own commitment to reason above all else and his tone deafness to the subtle music of human interaction. But it also was born of the sheer imperiousness enabled by his emergence into the public eye. He seemed to have an innate knowledge of how to handle his new situation: he responded to our clamor by telling us to work it out among ourselves and get back to him with the results. Maybe he couldn't send out bombs anymore, but he could still use the mails to treat people as pure abstraction. I imagined him reveling in his new found popularity, this man who had been described over and over as the consummate nerd. Terrorism in the age of celebrity had suddenly given him friends and influence.

IX. The Six Stages of Moral Development.

Kaczynski’s taxonomy of correspondents provided more than insight into his character. It was also a passport to other parts of the Unabomber kingdom. It's a great conversational entree: "Hi, this is Gary Greenberg calling. I got a letter today from Ted Kaczynski suggesting I get in touch with you." So all the Unabomber's men were willing to interrupt their breakfasts, to talk about Kaczynski with an understated delight.