George Caffentzis and Silvia Federici

Commoning

1. In Conversation with George Caffentzis and Silvia Federici

3. The Radical Subversion of the World

Silvia Federici’s Work as a Toolbox for Building Bridges, Opening Channels and Creating Bonds

The Radicalness of the Call to Struggle

4. Strange Loops and Planetary Struggles: A Postscript to Midnight Notes

5. Cogito Ergo Habo: Philosophy, Money and Method

6. Thomas Spence’s Freedom Coins

7. Standardisation and Crisis: The Twin Features of Financialisation

Craft, the Inside Contract and Standardisation

The Pursuit of Standardisation and the Bureaucratic Organisational Form

Class Composition and the Realignment of the Machine Process and Business Enterprise

Class Composition and the De-coupling of the Machine Process and the Business Enterprise

8. Reading ‘Earth Incorporated’ through Caliban and the Witch

Primitive Eco-Accumulation: Enclosing the World’s Body as ‘Earth Incorporated’

Calculating ‘Earth Incorporated’

A Concluding Comment on Continuing Enclosures and Erasures

10. Extending the Family: Reflections on the Politics of Kinship

Pregnancy, or a Ball Starts Rolling

Care, Reproduction and Belonging

Beyond the Sovereign Individual

Presence, Elders and Collective Memory

11. They Sing the Body Insurgent

12. The Separations of Productive and Domestic Labour: An Historical Approach

Slavery, Motherhood and Resistance

14. Along the Fasara - A Short Story

15. The Strategic Horizon of the Commons

In the Environment of the Commons: the Enclosing and Coopting Force of Capital and the State

The Theoretical Roots of ‘All in Common’

The Strategic Horizon of Reproduction

16. A Vocabulary of the Commons

The Structure of the Water War

A Place of Social Reproduction

17. A Bicycling Commons: A Saga of Autonomy, Imagination and Enclosure

Bicycling: A Window to Larger Changes

19. The Construction of a Conceptual Prison

20. In the Realm of the Self-Reproducing Automata

Automation, AI and Autonomists

Service Work and Sweatshop Labour

21. Notes from Yesterday: On Subversion and the Elements of Critical Reason

On Critical Reason: Beyond Personalisation

22. Sunburnt Country: Australia and the Work/Energy Crisis

Energy Crisis and Theoretical Deadlock

The Development of Renewables is a Revolution in the Cost of Creating Energy

Rising to the Question of Organisation

24. Practising Affect as Affective Practice

New People - New Women and Girls

‘We need to struggle, perhaps more than ever, given the magnitude and the character of the current destruction of everything – nature, society, culture, the very social fabric allowing us to live together. We need compas. We need, particularly, comrades with a clear sight and an open, affective heart. Many of us have found in George Caffentzis and Silvia Federici that company. They have led and accompanied us in many struggles, big and small, in great events and mobilizations or in small coffee talks. And here they are, to celebrate them, with an exceptional cohort of intellectuals/activists, with compas, who are saying today what needs to be said to continue the struggle, to resist the horror and to create a new world’.

– Gustavo Esteva, activist, ‘deprofessionalised intellectual’ and founder of Universidad de la Tierra in Oaxaca, Mexico

‘This collection offers an extraordinary kaleidoscope of critical reflections on social reproduction and class struggle. More than that, it is fitting testimony to the inspiration and grounding that Silvia and George continue to provide for those seeking a life beyond the sway of capital’.

– Steve Wright, author of Storming Heaven: Class Composition and Struggle in Italian Autonomist Marxism

‘No one has taught us more, and more generously, that communism is with us than George Caffentzis and Silvia Federici. Indeed, to be in their presence, to be with their writing and interviews, is to feel intimately the social wealth we are struggling to defend and expand in the face of the geocidal and genocidal plans of the policy class and its backers. That we are the sources not only of that wealth but also of the social transformations necessary to survive in abundance, this is the insight, the lifeline, the hug we receive from the greatest living theorists of commoning’.

– Stefano Harney, coauthor of The Undercommons:

Fugitive Planning and Black Study

‘In this labour of love, radical theory joins passionate praxis to honour the social thought and political vision of Silva Federici and George Caffentzis, whose work together and apart offers hope that another world can be made.’

– Eileen Boris, coauthor of Caring for America: Home Health Workers in the Shadow of the Welfare State

Commoning

With George Caffentzis and Silvia Federici

Edited by Camille Barbagallo,

Nicholas Beuret and David Harvie

First published 2019 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 7453 3941 2 Hardback

ISBN 978 0 7453 3940 5 Paperback

ISBN 978 1 7868 0466 2 PDF eBook

ISBN 978 1 7868 0468 6 Kindle eBook

ISBN 978 1 7868 0467 9 EPUB eBook

This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin.

Typeset by Riverside Publishing Solutions, Salisbury, United Kingdom

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction: Always Struggle - Camille Barbagallo, Nicholas Beuret and David Harvie

I - REVOLUTIONARY HISTORIES

1. In Conversation with George Caffentzis and Silvia Federici - Carla da Cunha Duarte Francisco, Paulo Henrique Flores, Rodrigo Guimaraes Nunes and Joen Vedel

2. Comradely Appropriation - Harry Cleaver

3. The Radical Subversion of the World - Raquel Gutiérrez Aguilar

4. Strange Loops and Planetary Struggles: A Postscript to Midnight Notes - Malav Kanuga

II - MONEY AND VALUE

5. Cogito Ergo Habo: Philosophy, Money and Method - Paul Rekret

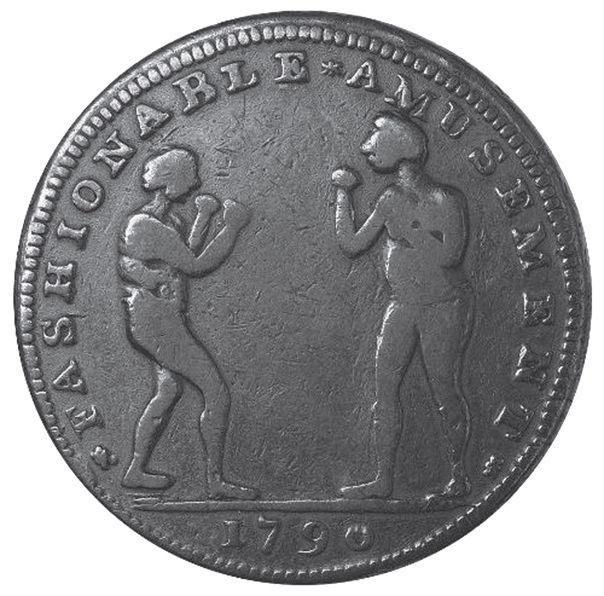

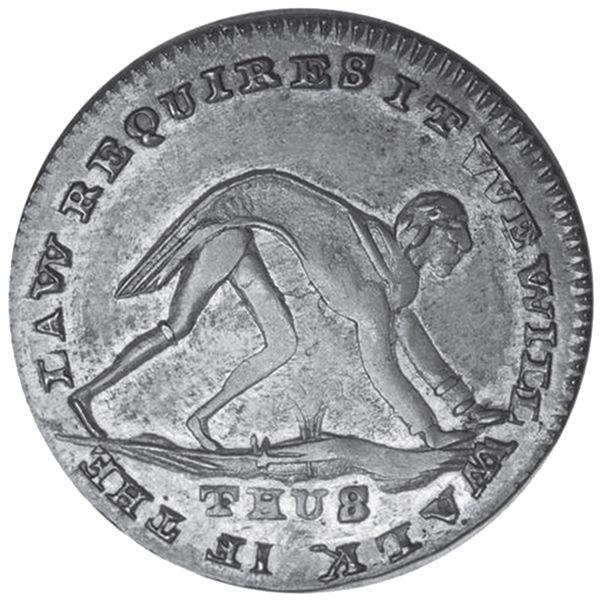

6. Thomas Spence’s Freedom Coins - Peter Linebaugh

7. Standardisation and Crisis : The Twin Features of Financialisation - Gerald Hanlon

8. Reading ‘Earth Incorporated’ through Caliban and the Witch - Sian Sullivan

III - REPRODUCTION

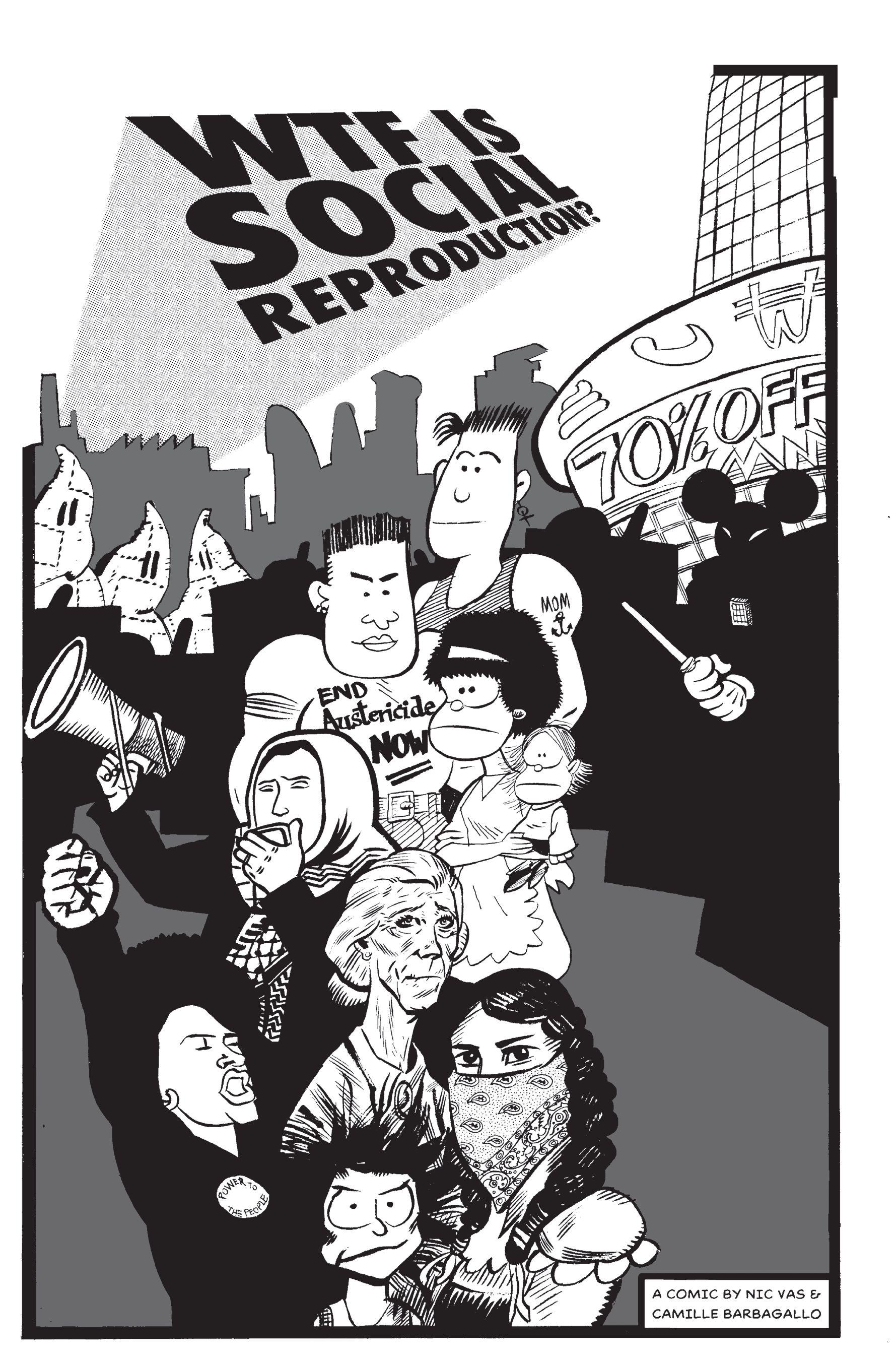

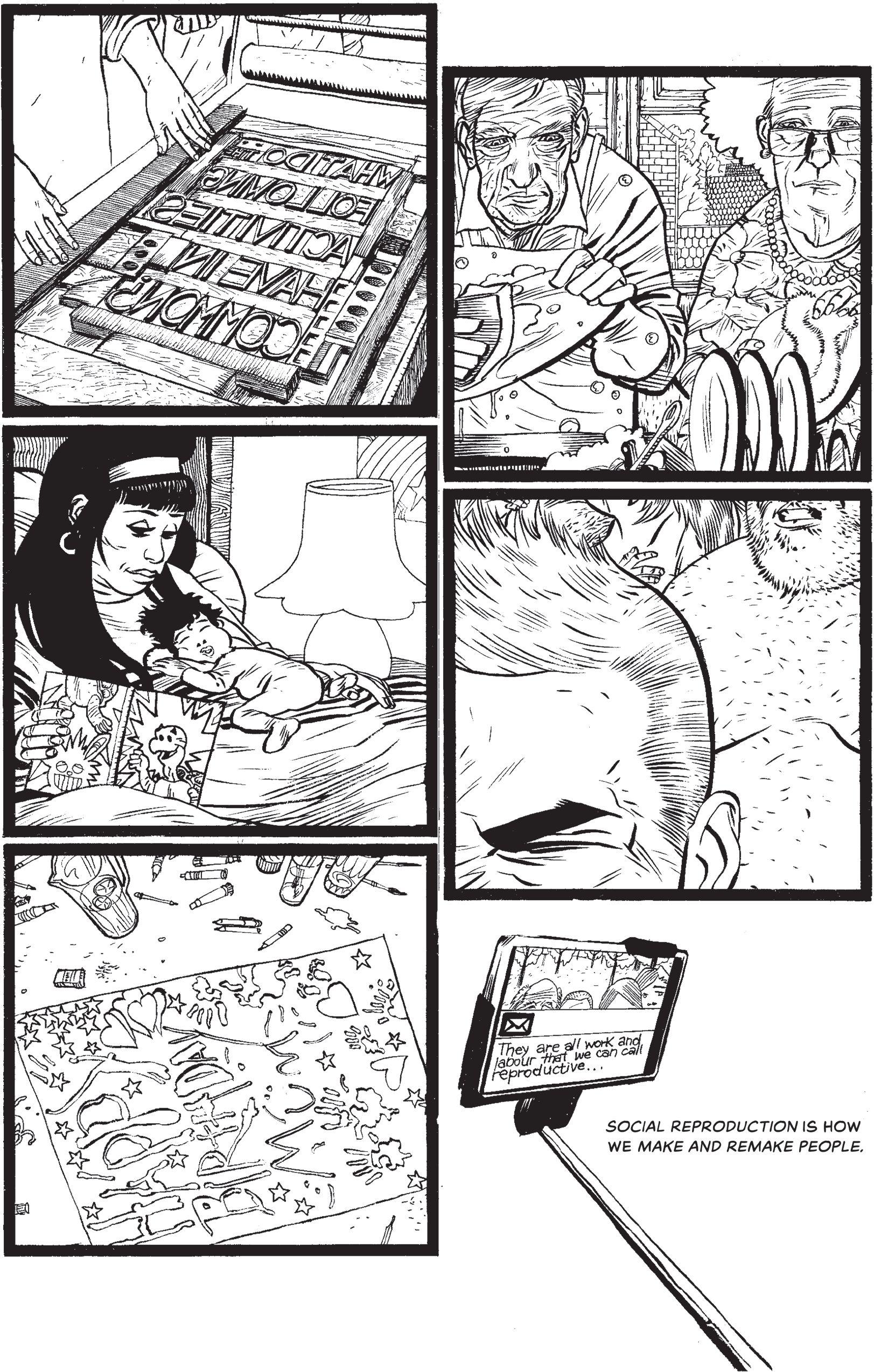

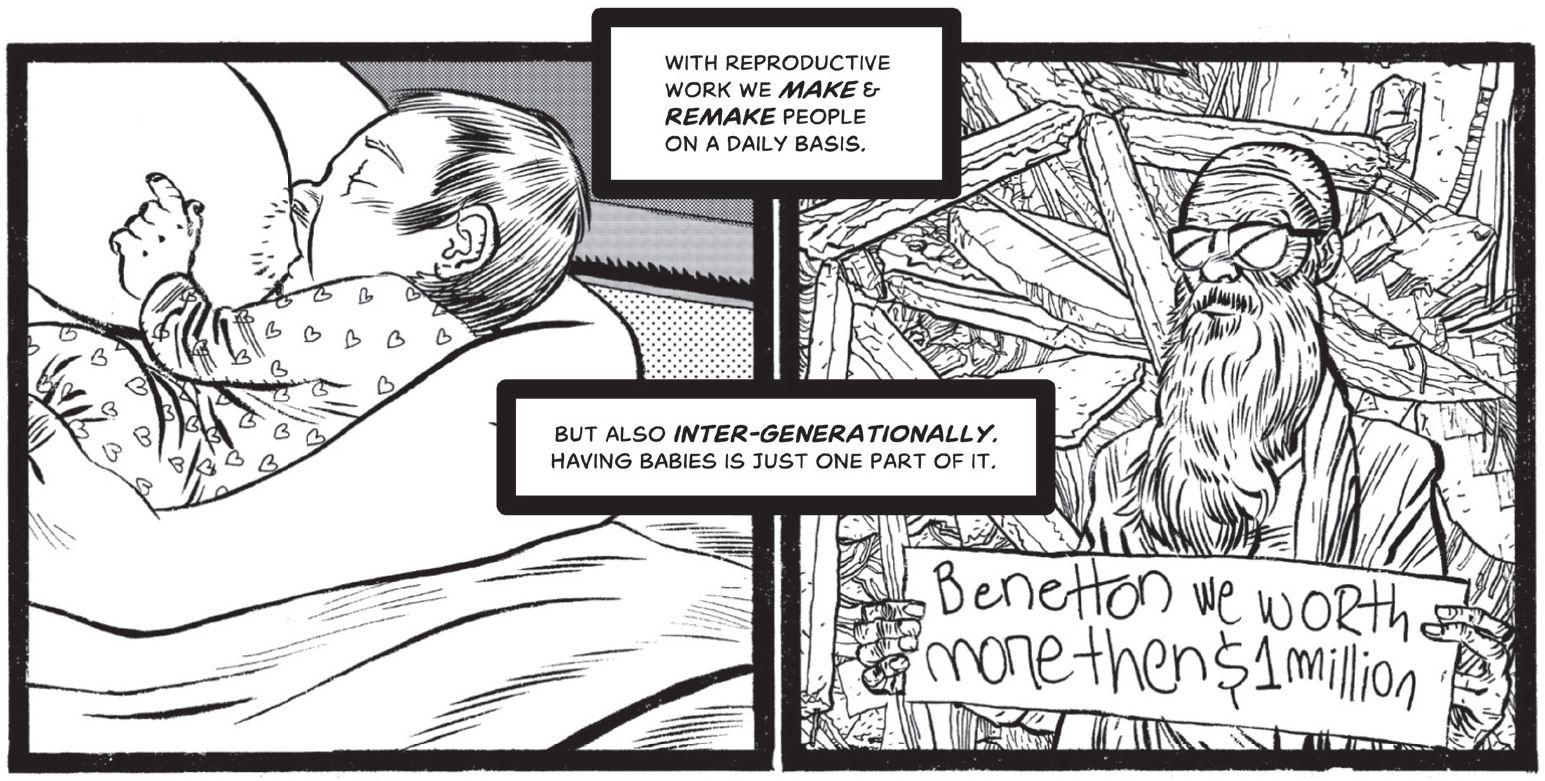

9. WTF is Social Reproduction? - Nic Vas and Camille Barbagallo

10. Extending the Family: Reflections on the Politics of Kinship - Bue Rübner Hansen and Manuela Zechner

11. They Sing the Body Insurgent - Stevphen Shukaitis

12. The Separations of Productive and Domestic Labour: An Historical Approach - Viviane Gonik

13. Another Way Home: Slavery, Motherhood and Resistance - Camille Barbagallo

14. Along the Fasara – A Short Story - P.M.

IV - COMMONS

15. The Strategic Horizon of the Commons - Massimo De Angelis

16. A Vocabulary of the Commons - Marcela Olivera and Alexander Dwinell

17. A Bicycling Commons : A Saga of Autonomy, Imagination and Enclosure - Chris Carlsson

18. Common Paradoxes - Panagiotis Doulos

19. The Construction of a Conceptual Prison - Edith Gonzalez

V - STRUGGLES

20. In the Realm of the Self-Reproducing Automata - Nick Dyer-Witheford

21. Notes from Yesterday: On Subversion and the Elements of Critical Reason - Werner Bonefeld

22. Sunburnt Country: Australia and the Work/Energy Crisis - Dave Eden

23. Commons at Midnight - Olivier de Marcellus

24. Practising Affect as Affective Practice - Marina Sitrin

Contributor Biographies

Index

Introduction: Always Struggle

Camille Barbagallo, Nicholas Beuret and David Harvie

.. .ideas don’t come from a light-bulb in someone’s brain; ideas come from struggles — this is a basic methodological principle. - George Caffentzis[1]

The militant scholarship of George Caffentzis and Silvia Federici has never been more needed. Together and separately, they have, over a half-century, developed a radical political perspective and praxis. Today, activists and militants across the world are engaging more widely with their many insights and methods. The commons, the uptake of ideas of social reproduction, the integration of ecological and energy concerns with Marxist analysis, and a renewed radical critique of technology are all contemporary themes that they have helped develop over the past decades.

What connects all of these ideas and perspectives is the concept of struggle. There are three ways to understand struggle in George and Silvia’s work: as practice, as theory and as method. The first is reflected in the practice of Silvia and George themselves. For more than 50 years - from the 1960s’ anti-Vietnam war movement, through feminist movements, including Wages for Housework in the 1970s, various workers’ and anticolonial struggles, anti-nuke movements from Three Mile Island to Fukushima, campaigns against the death penalty, the Gulf War, the second Gulf War, to Occupy Wall Street and debtors’ movements - George and Silvia have always involved themselves in social struggle of one form or another. The second is as the source of theory - of ideas and praxis. Theory as something that comes not only from struggle, but also from a commitment to struggle as that which drives social change. The third is to see struggle as a method for understanding crises, events, social and political relations, and movement.

The work of George and Silvia converges on and flows out of these interconnected understandings of struggle. More than that, they both - separately, together, with others - have worked tirelessly to expand and deepen our understanding of the terrain of struggle. Of who it is that struggles, how struggles come to matter or count, and of the significance of struggles across the social field.

This volume explores the life and scholarship - the main themes and key insights - of George and Silvia. It is a celebration of two comrades, a chance to revisit their writings and appreciate the wealth of their contribution, and at the same time a continuation of the circulation of militant ideas, theories and histories - a continuation of their own practice.

Through militant lives that became intertwined in the 1970s George and Silvia developed a particular orientation to radical politics, one that started in conversation with the Italian Marxist tradition of operaismo, and continued through the perspective developed by Wages for Housework. They experienced first-hand - and struggled against - the emergence of neoliberalism with the ‘structural adjustment’ of New York City in the mid- 1970s; a little later, their experiences in Nigeria deepened their understanding of colonialism, imperialism and energy struggles, which in turn sparked an engagement with ‘primitive accumulation’ and a rediscovery of the commons. On returning to the United States, they became heavily involved in the emerging counter-globalisation movements; by chance arriving in Mexico at the beginning of 1994 they witnessed the Zapatistas’ uprising and went on to spend considerable time in Latin America. What these examples - just a handful out of many - demonstrate is the extent to which Silvia and George have always been grounded within revolutionary and other rebellious movements and currents.

The concept of struggle reflects a feature of the world: there is always struggle. Here we understand struggle most broadly as class relations. As Werner Bonefeld reminds us in his chapter in this volume, ‘history does not unfold at all. “History does nothing”’. There are just human beings, pursuing our ends - struggling. We cannot understand the development of the capitalist mode of production or other social forms without understanding the struggles of millions, and now billions, of human subjects. In this sense, George and Silvia’s work is in dialogue with the insight that opens The Communist Manifesto: ‘the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggle’.

For both George and Silvia the ‘Copernican inversion’ of Marxist theory developed within operaismo, where working class struggles are understood as primary - primary in the sense that it is struggle that militants must be concerned with and theorise, and primary to capitalist development, where struggle precedes capital’s transformations - marked a turning point in their own political development.

The first set of ideas came out of the Italian operaista movement... We begin to look at class struggle as a field, instead of certain spots or sites - that there’s this field of struggle that takes place all across the system. You look at buildings and you begin to see not the thing itself but the processes that went on, the sufferings, the struggles that went on to make the thing. It was like an opening of the eye, really. - George Caffenzis[2]

From the Operaist movement... we learned the political importance of the wage as a means of organizing society. From my perspective, this conception of the wage. became a means to unearth the material roots of the sexual and international division of labour and, in my later work, the ‘secret of primitive accumulation’. - Silvia Federici[3]

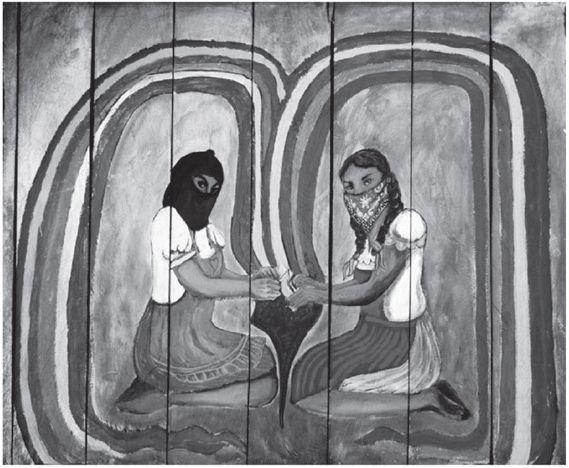

It is here that struggle becomes something ordinary, everyday. It is not a matter of unions, parties or parliaments, but of the daily actions of workers in work - and struggling against and beyond work. Within this tradition, the refusal to work figures as a key weapon of the proletariat, one through which autonomy from both capital and the state is asserted. Silvia and George have helped extend this tradition to encompass and speak to women struggling against patriarchy, people of colour struggling against racism, peasants struggling against ‘progress’ and ‘development’. In the words of the Zapatista Ana Marfa, ‘Behind us we are you, . behind, we are the same simple and ordinary men and women who repeat themselves in every race, who paint themselves in every colour, who speak in every language and who live in every place’.[4]

When the capitalist counter-offensive of the 1970s took hold, George and Silvia responded by staying within the struggles around them. They ‘stretched’ Marx and his categories in order to develop an account of the wage that foregrounded the crucial role of the wageless - ‘housewives’, peasants, students, for example - of how people devalued, made invisible or less-than-human laboured to underpin capitalist accumulation through their partial and total exclusion from the wage relation. Thus throughout their work we find an emphasis on expanding and developing our understanding of the composition of the proletariat, with this insistence that the struggles of the unwaged are as important - sometimes more so - as those of the waged. Rejecting forms of autonomist Marxism that flee the question of value, George and Silvia instead develop a current in which Marx’s ‘law of value’ - appropriately ‘stretched’ of course - is as important as ever. In their expansive conception, we find a broadening of the field of struggle. This allows them - and us - to continue to pose the questions of energy, war, money and debt, and automation in a manner profoundly relevant for contemporary political debates and antagonisms around climate change, environmental destruction, automation and the role technology can and does play in shaping our world and those worlds to come.

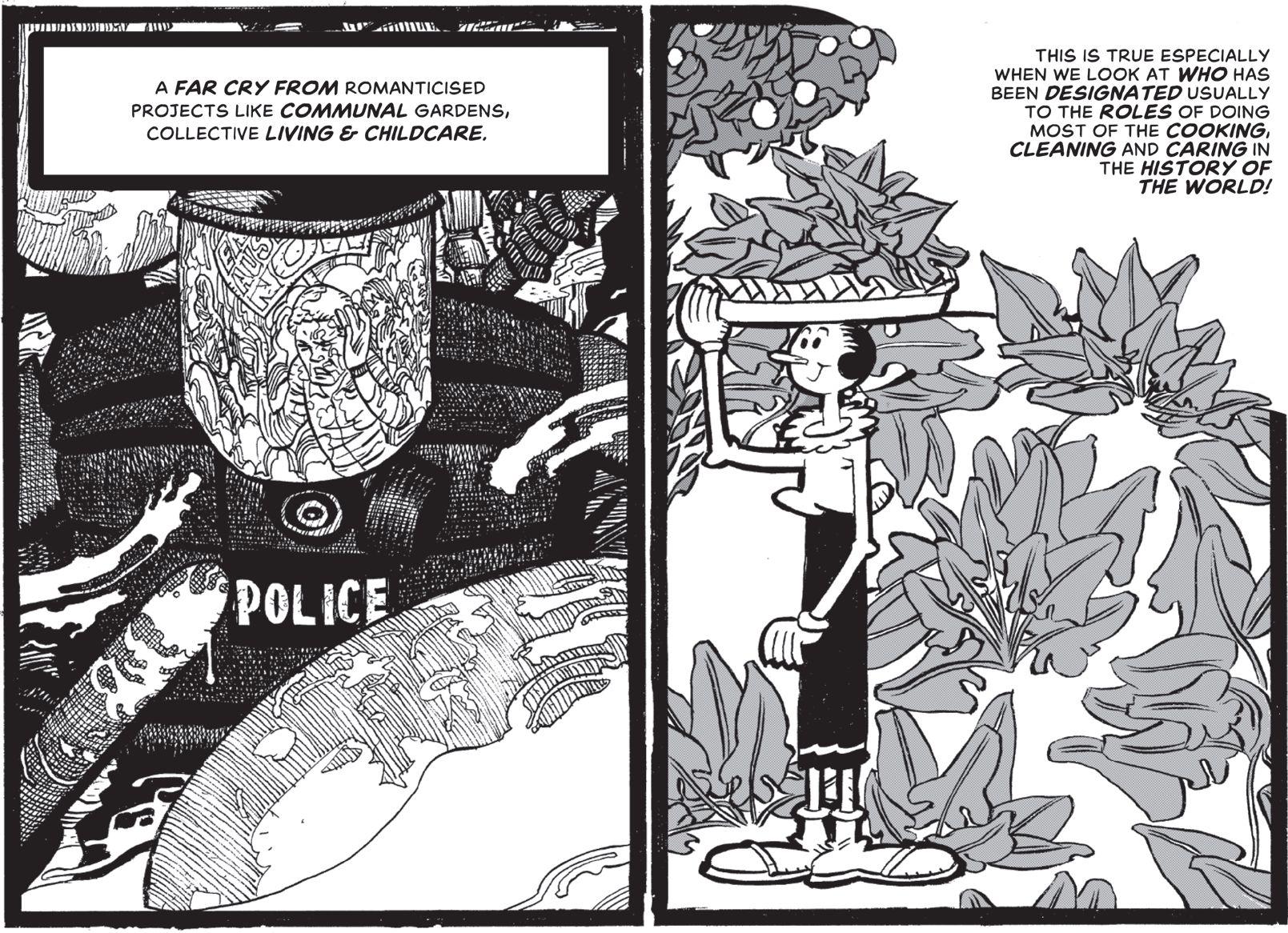

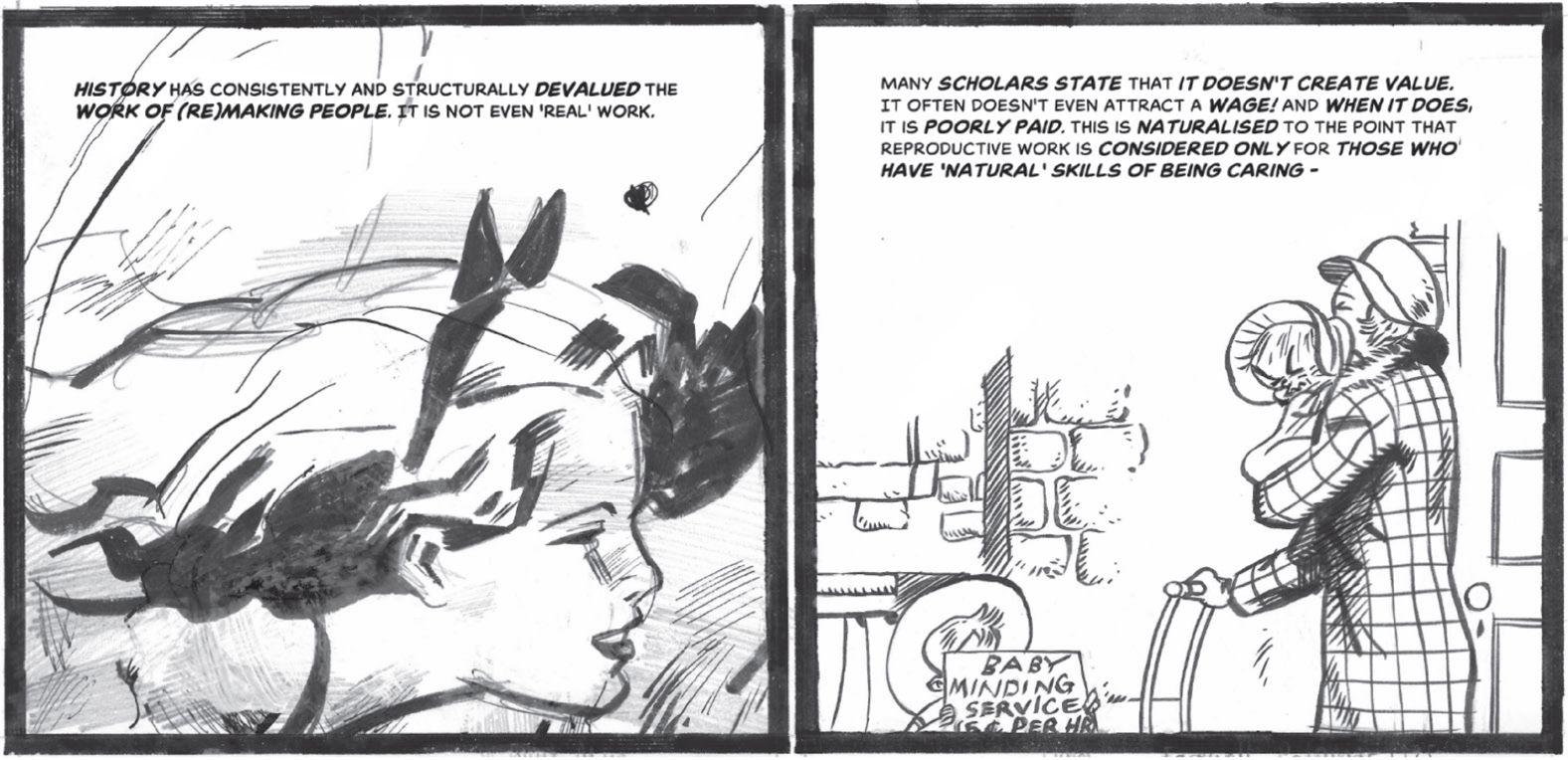

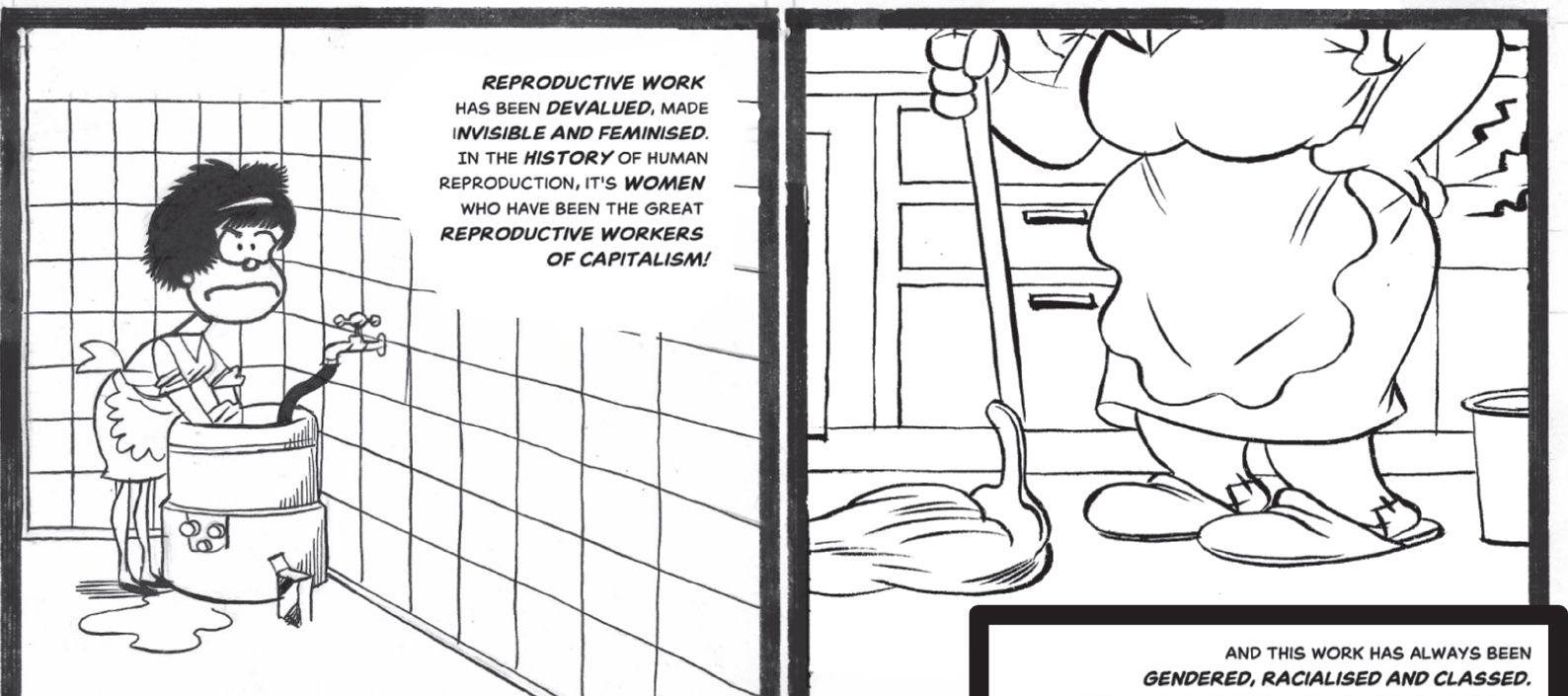

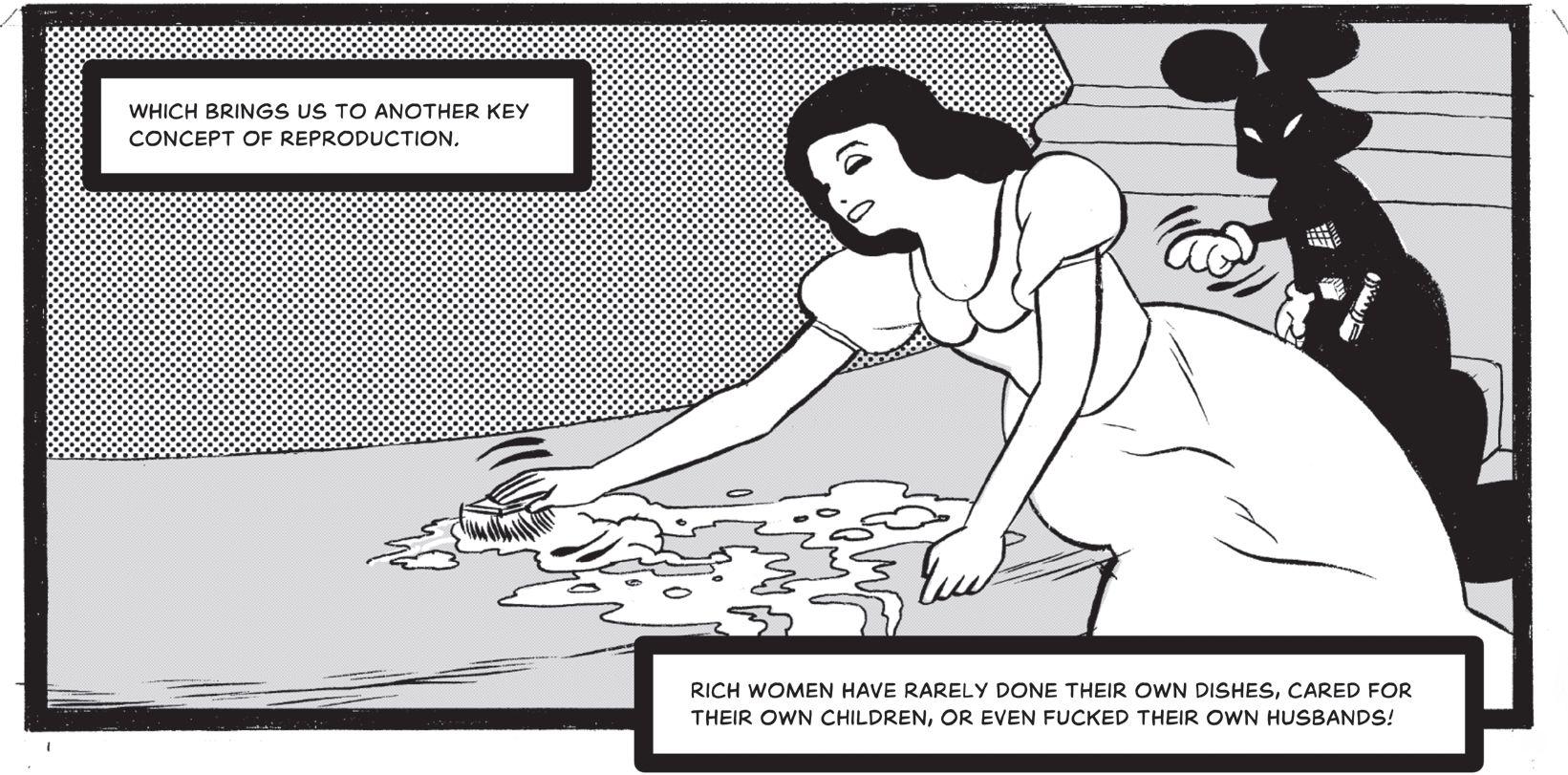

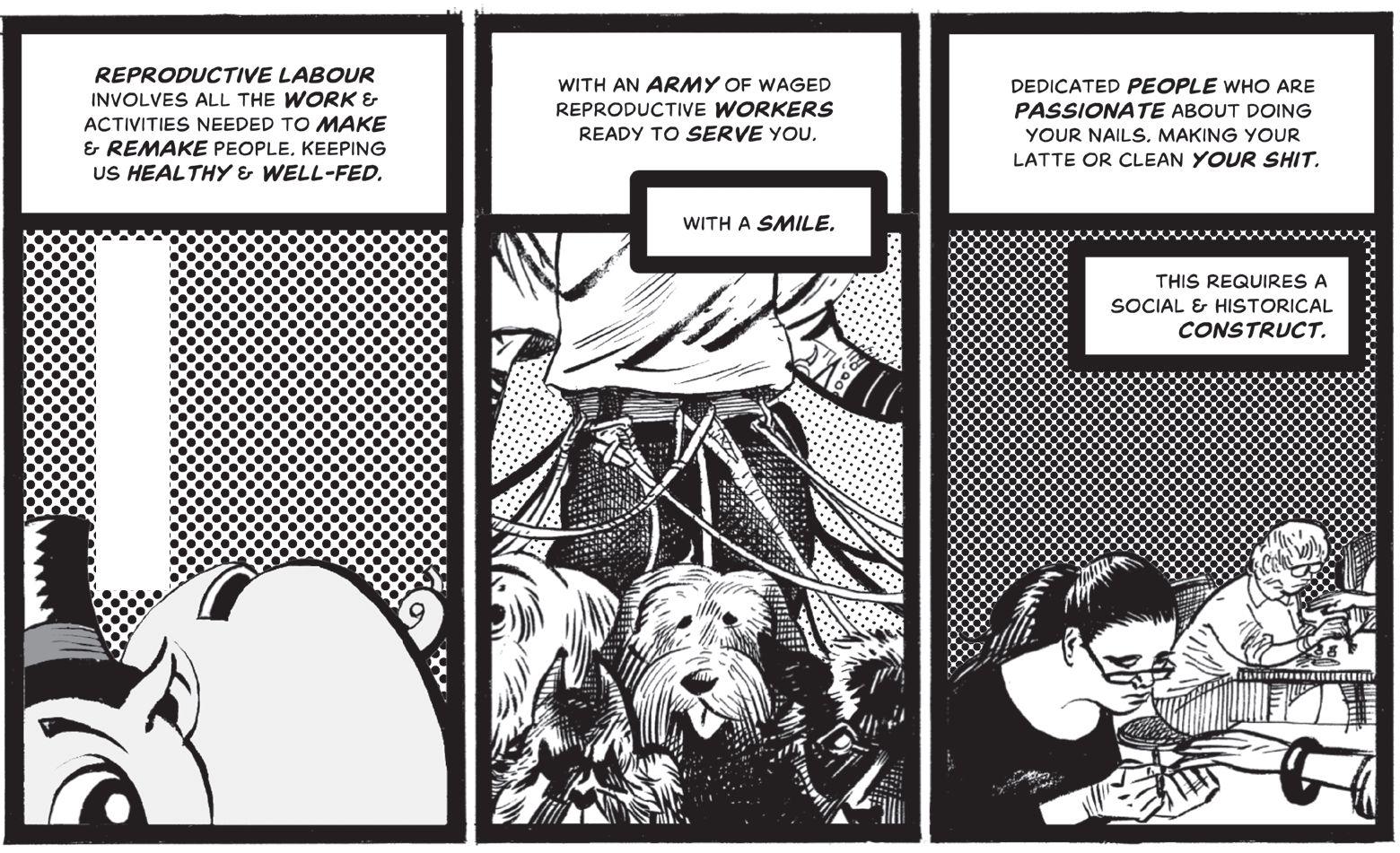

Social Reproduction

I saw the struggle, that feminism really had a class dimension, once we understood the feminist movement as one that confronted the revolt against one of the major articulations of the capitalist organisation of work, which is the work of reproduction. - Silvia Federici[5]

It is well known that Silvia was a founding member of the International Wages for Housework Campaign as well as organising numerous other militant feminist collectives and initiatives. In connected ways, the feminist movement in general, and Wages for Housework in particular, were formative for George as well. Wages for Housework was more than the source of theoretical insight. It was both part of a struggle against capital and the state and, at the same time, a critique of the radical social movements of the time. Seeing housework and social reproduction as work, as a site of labour and exploitation, situated women as workers. It was a political praxis that generated considerable conflict within both the left and feminism. Understanding social reproduction in this way was a provocation that led to the ‘opening up [of] a new terrain of revolt, a new terrain of anticapitalist struggle directly’ and no longer acting as just supporters to men’s struggles.[6] These insights remain as important now as they were in the 1970s - for these struggles and tensions, within social and left-wing movements, and within feminism, continue today, albeit under different names.

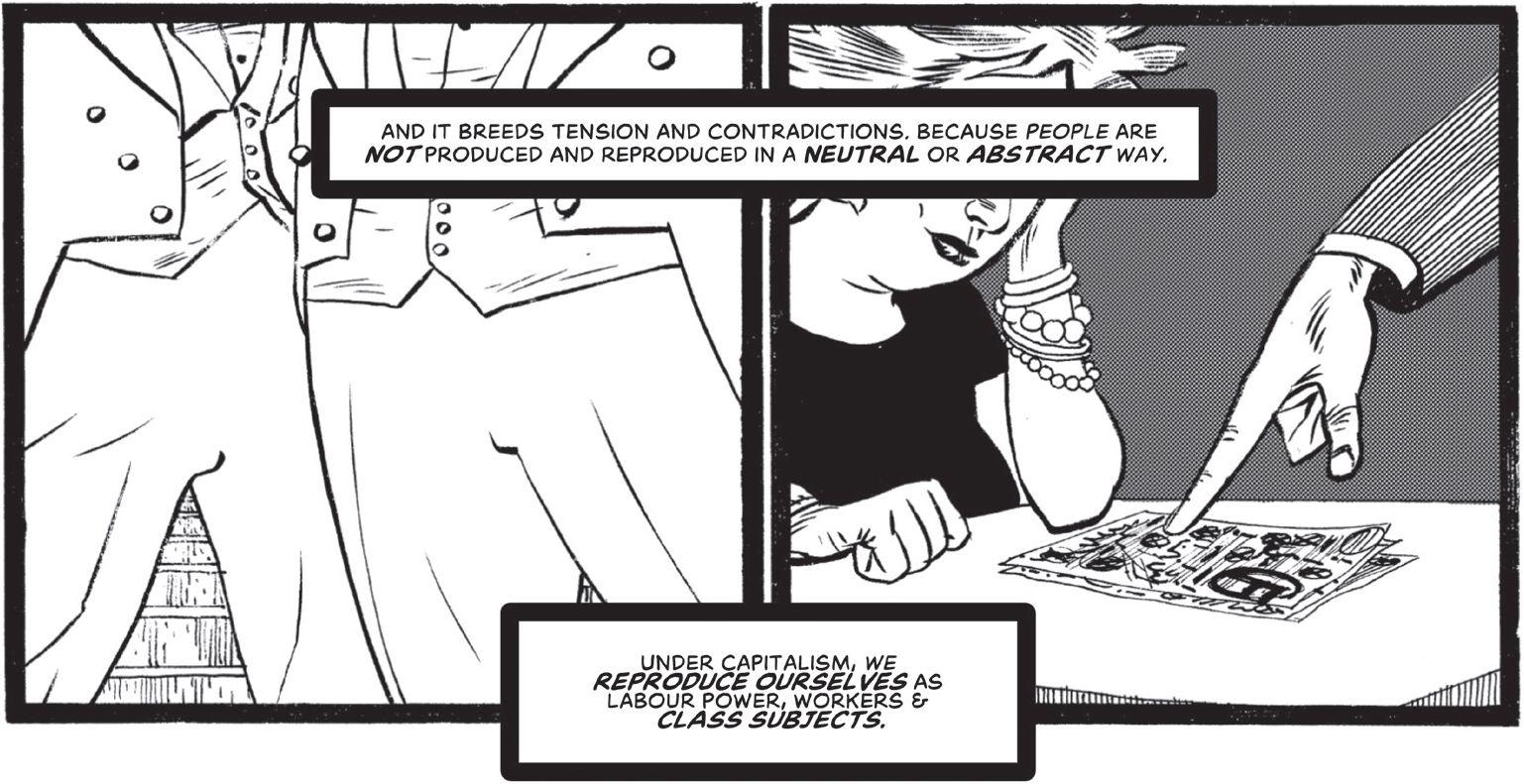

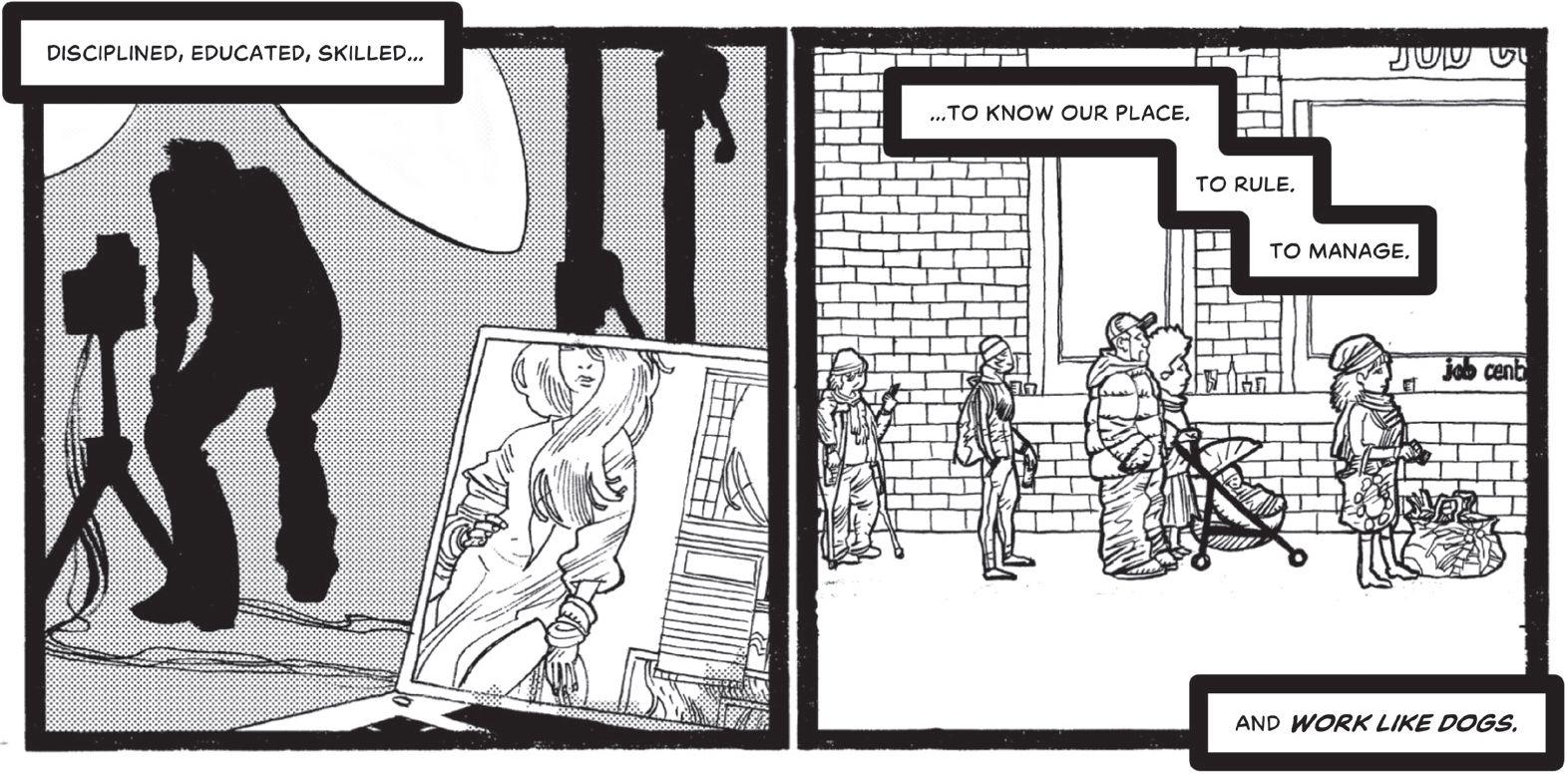

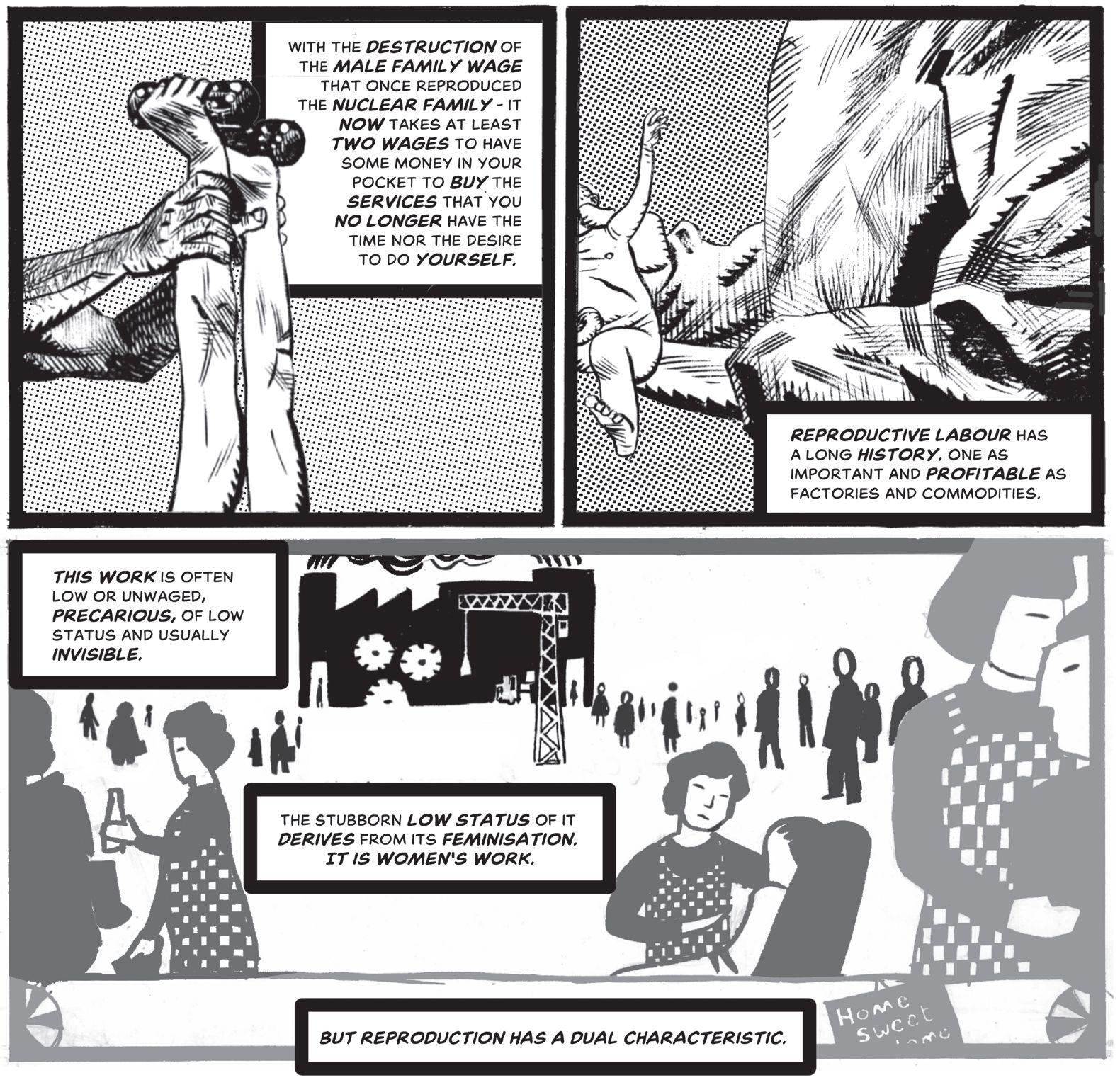

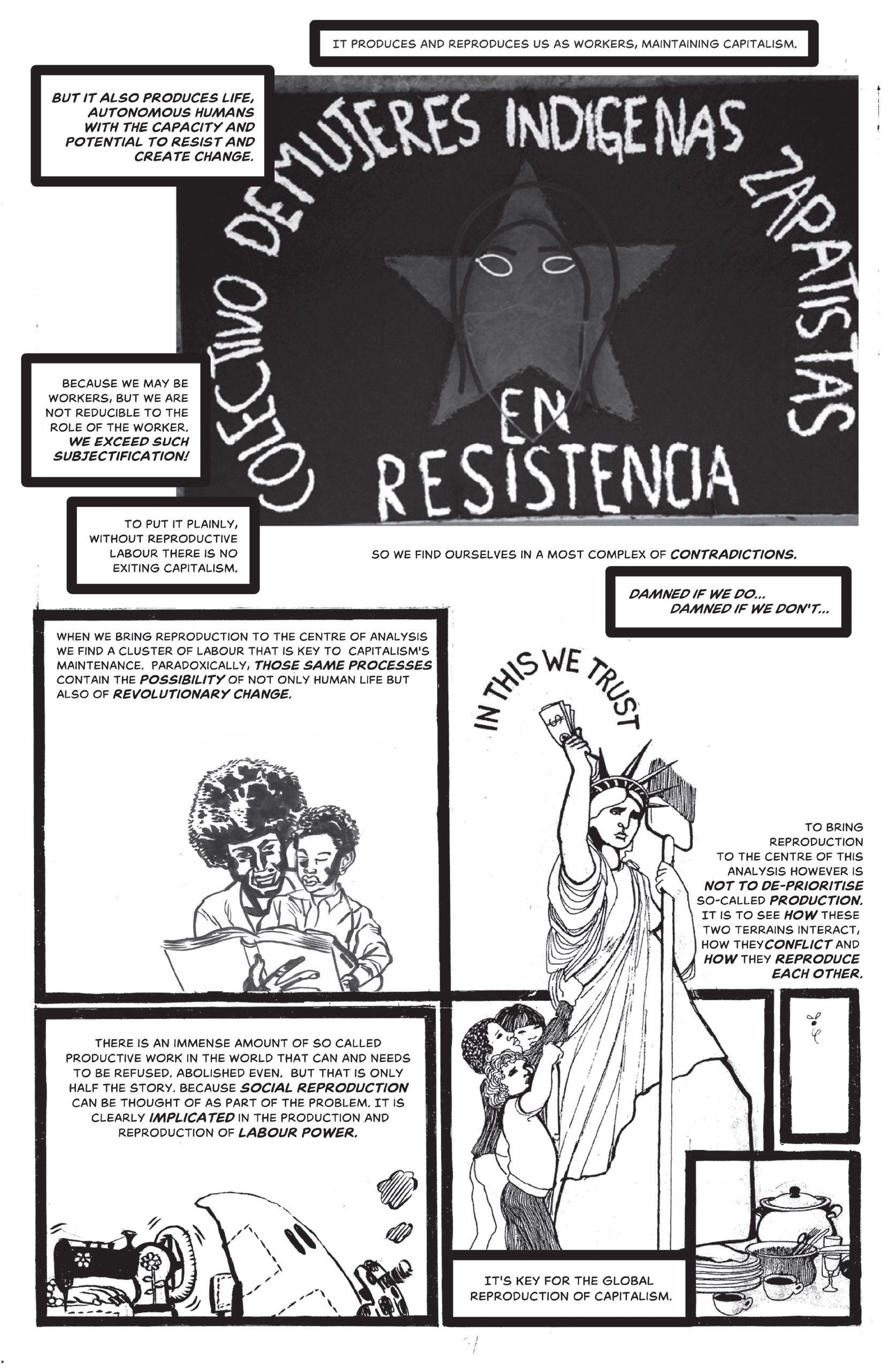

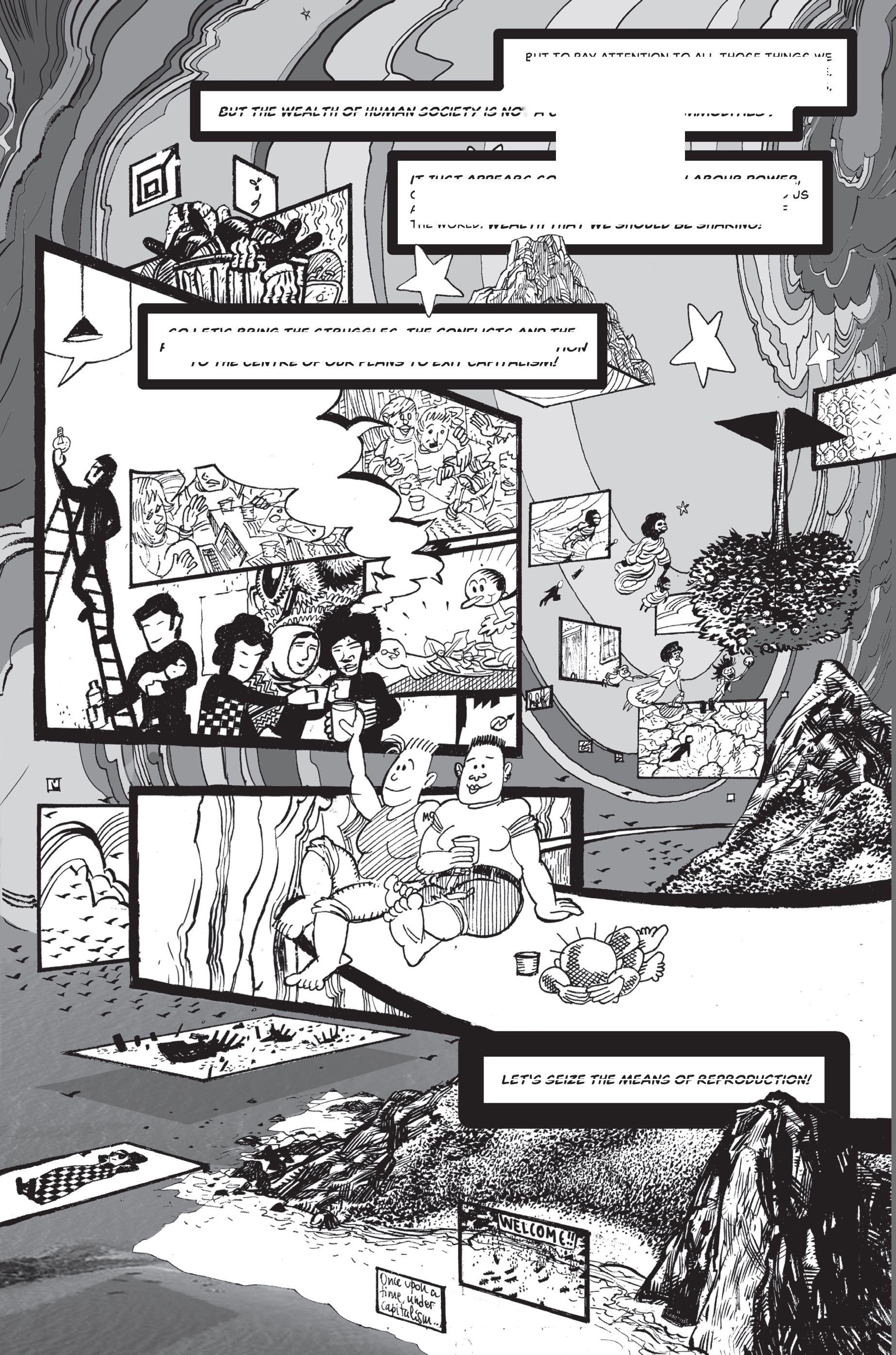

Connected to the definition of reproduction as a labour process is the Marxist feminist argument that, at the same time that reproductive labour makes and remakes people, it also produces and reproduces that ‘special commodity’, labour-power - a process which Silvia refers to as the ‘dual characteristic of reproduction’. In positing reproduction as possessing a duality, it becomes possible to both revalue this work and, at the same time, identify the practices and processes that are implicated and foundational in the maintenance of capitalist social relations. The dual characteristic of reproduction draws attention to the tensions and contradictions at the centre of the processes of social reproduction; a tension that is directly related to what reproduction does within capitalism and how it operates.

In societies dominated by capitalism, people are reproduced as workers but also, at the same time, they are reproduced as people whose lives, desires and capabilities exceed the role of worker. People are more than their economic role; they are irreducible to it. This is one aspect of why labour-power is ‘special’ - if we did not exceed our economic role, we would not be capable of producing surplus-value. People struggle, are involved in conflict and, frequently, resist. In this way reproductive labour can be said to have two functions: it both maintains capitalism in that it produces the most important commodity of all - labour-power - and, at the same time, it has the potential to undermine accumulation, by producing rebellious subjects.

The Commons

.. .when we returned to the United States - other comrades had already left the US during this period. And we all returned and had pretty similar stories to tell. So we began to work on this notion of the commons and enclosures. Being the way in which we can talk about the class struggle in this period. - George Caffentzis[7]

George and Silvia are also well known for their work on the commons. They have credited their experiences in Nigeria in the early-to-mid-1980s as being the genesis point on their thinking around commons and their antithesis, enclosures. But potentially as significant is the New York they left behind them. That city was declared bankrupt in 1975: capital’s response was one of the world’s first ‘structural adjustment programmes’, a weapon that would become well-established in neoliberal globalisation’s armoury. This restructuring used the city’s ‘debt crisis’ to enforce a series of privatisation programmes, savage cuts to the social wage and attacks on working conditions and workers’ rights to organise. When George and Silvia witnessed first-hand another ‘structural adjustment’ in Nigeria, they could see how capital’s various restructurings were in fact different manifestations of one global process, in which questions of the social wage, land and stillexisting commons - in Third World as well as First - all intersected.

The transnational character of ‘structural adjustment’ and capital’s offensive against commons led directly to an engagement with the continuous nature of what Marx called ‘primitive accumulation’. George and Silvia, as a part of the Midnight Notes Collective, described these ongoing instances of primitive accumulation as ‘new enclosures’.

The Enclosures. are not a one time process exhausted at the dawn of capitalism. They are a regular return on the path of accumulation and a structural component of class struggle. Any leap in proletarian power demands a dynamic capitalist response: both in the expanded appropriation of new resources and the extension of capitalist relations.[8]

Midnight Notes’ work on the new enclosures covered struggles spanning the globe. It emphasised not only the central importance of land as a site of struggle and dispossession, but also debt as a mechanism of dispossession. This recognition of the tight connection between debt on the one hand and enclosure on the other forms a crucial part of George and Silvia’s work on the commons. Insights developed to understand capital’s creation and exploitation of an ‘international debt crisis’ in the 1980s continues to inform their work today, on microfinance, say, or in their involvement in the Occupy movement.

But against the capital’s various mechanisms to dispossess and to enclosure, just as crucial is the recognition of the commons’ role in facilitating resistance: in Nigeria, the commons ‘made it possible for many who are outside of the waged market to have collective access to land and for many waged workers with ties to the village common land to subsist when on strike’.[9]

Even when urbanized, many Africans expect to draw some support from the village, as the place where one may get food when on strike or unemployed, where one thinks of returning in old age, where, if one has nothing to live on, one may get some unused land to cultivate from a local chief or a plate of soup from neighbours and kin.[10]

Here we also have the recognition that commons may have the potential, not only to enable struggle against capital, but also provide a foundation for the creation of worlds that exist outside and beyond capital and the state.

This scholarship has directly inspired and influenced more recent theoretical work on the present-day relevance of commons and enclosures.[11] It also predates by a decade and a half David Harvey’s discovery of ‘accumulation by dispossession’?[12] Through it, George and Silvia have connected the ‘old’ Enclosures - and the struggles of English and Scottish commoners against these - to the wide range of present-day European and non-European commons that continue to be fiercely contested. But, more than this, Silvia and George present to us the commons as a political project. Commons are not things, but social relations - of cooperation and solidarity. And commons are not givens but processes. In this sense, it is apt to talk of commoning, a term coined by one-time Midnight Notes collaborator Peter Linebaugh?[13] Neither George nor Silvia argue that commons as projects are a panacea for the issues that beset the contemporary left, feminist, anti-racist, anti-colonial or environmental movements. However, the commons fill a lacuna in radical thought, providing a way in which we might practically work out how we are to live with each other and the world without the violence of the state or the rule of capital. That is, when we pose the question, as urgent now as ever, What sort of world do we want to live in? commons must surely be part of the answer.

In the chapters that follow a wide range of comrades explore and develop the themes woven above, as many other concepts and struggles that George and Silvia have addressed. We begin with George and Silvia’s engagements with history. This first section opens with an interview in which they outline their own experiences - the interview both lays the groundwork for later chapters but also emphasises the role historical thought has played in their work. In Section II we turn to questions of money and value. As we noted above, George and Silvia insist on the continued relevance of value - with money as its expression - as organiser of human activity and the contributions here explore various historical and contemporary aspects of the way the ‘law of value’ operates - and is resisted. The subject of Section III is reproduction. The chapters in this section address the modes in which human beings are ‘produced’ and reproduced, and the separations between spheres of ‘production’ and ‘reproduction’; we also include here a speculative account of the way an entire society might transition from one way of life to another - and the consequences of this. The book then turns - in Section IV - to the commons, working through both practical and theoretical engagements with the concept. Finally - and appropriately - we end - in Section V - with five chapters which engage with the idea and reality of contemporary struggles.

We cannot do justice in this collection to the extent of the contribution George Caffentzis and Silvia Federici - singly, together and in collaboration with others, such as the Midnight Notes Collective - have made to militant feminist and anti-capitalist scholarship. It goes without saying that we recommend readers explore their many writings - if they haven’t already.[14] We are delighted how enthusiastically our invitation to contribute to this volume was received. This is testament to the esteem and affection with which George and Silvia are held by comrades around the world. And yet we haven’t been able to represent the breadth and depth of their contributions over half a century, touching militants on every one of our planet’s inhabited continents. All we have been able to do is sample. The contributions here are, nevertheless, extremely varied. In content. In style. In tone. And spanning several generations. This diversity is testament to the wide reach of the influence of George and Silvia and their care.

I. Revolutionary Histories

1. In Conversation with George Caffentzis and Silvia Federici

Carla da Cunha Duarte Francisco,

Paulo Henrique Flores, Rodrigo Guimaraes Nunes and Joen Vedel

George:

The 1960s, maybe the early 1960s, was the first experience I had of a political struggle in the United States. I’ve always wondered what happened to me as a young person, a teenager, and why my political path was so different from the rest of my family. Because you might not know it, but Greek Americans are very conservative, in general, from the point of view of US politics. So I’m one of those rare birds. I used to joke that you could count radicals of Greek-American origin on your right hand. What led me to this path, I’m not sure. I’ve done some investigations, and it appears that I went to Greece in 1958. This was a breaking point. It was the first time after a long period of repression that the forces of the left came out on the streets officially, actually to protest the American bases in Greece. I’m projecting back that it was that experience - and because my family in Greece was much more on the left - that it had a profound impact upon me and I picked up that path. Of course, this is all in retrospect.

What then happened is, I begin to try to understand what a left-wing path would be in the US during the time of McCarthy and so on. I began to - in high school - read Marx, especially the young Marx, the 1844 Manuscripts and so on, that were just becoming available at that time, and I began to question the type of left-wing politics that had been available in the United States, especially the Communist Party. I got drawn into the civil rights movement at that time, because that was the place to be. I got arrested, on various demonstrations and so on. And along with that I met Harry Cleaver; he is my oldest childhood friend, if you can say that childhood goes on to 18 or 19. So we began to explore the kind of thinking that would be appropriate, politically, for this kind of period.

During the great student strike in the wake of the Kent State killings,[15] I and a number of other comrades in the movement began to think of a project that would make permanent much of the political thought that had begun to develop in the United States. And so we decided that we would write an anti-Samuelson textbook. A counter-textbook for a counter-course that would really, not only criticise the work of Samuelson and bourgeois economics, but also begin to see what this critique would lead to in terms of politics. So, I basically, with these comrades, spent three years reading Marx and criticising Paul Samuelson’s work.[16] We published a four-volume book in East Germany for this counter-course that, by the time of 1973, was appealing to a movement that had largely spent its energy.

But 1973 became an important year for me. I call it my annus mirabilis, my year of - at least intellectual - miracles. Marvels. Because it was in that year that I met a whole group of political activists and theoreticians, one group coming from Italy, and the other group coming from the feminist movement. I began to recognise some themes that would become part of my permanent conception of how the system works and ways in which it could be overturned. Let me take them in order.

The first set of ideas came out of the Italian operaista movement, with the conception that capitalism is not something that is confronted and this class struggle is not something that takes place on the formal level between unions and parties and the capitalist state. That in fact the struggle takes place not only in the strike lines but also within the centres of production. We begin to look at class struggle as a field, instead of certain spots or sites - that there’s this field of struggle that takes place all across the system. If you want to understand how capitalism operates, you have to see it on the micro level. That was an eye-opener, because as you walk around, you hear the voices of these struggles speaking to you in the same way as with the labour theory of value. You look at buildings and you begin to see not the thing itself, but the processes that went on, the sufferings, the struggles that went on to make the thing. It was like an opening of the eye, really. I was very pleased by this experience, because it opened up a political connection that led to the publication of a journal called Zerowork.[17]

Now simultaneously, almost, with this experience, came my exposure to Wages for Housework. In fact, much of this took place with Silvia, and I met Mariarosa Dalla Costa and Selma James, and began to personally understand the thinking that was taking place in the Wages for Housework movement. It was very important for me as, well, I don’t know, as the patriarchal tradition was behind me. I was a young Greek-American child of immigrants and so on, and I must say, I brought from Greece much of this patriarchal bedrock, you might say, this psychological bedrock, and it needed to be blasted! I began to understand the depth of the work that was being done by Wages for Housework and it re-transformed my conception of what capitalism is.

The first edition of Zerowork [published at the end of 1975] was an attempt to bring together these two insights, theories, ways of seeing capitalism and our collective struggles.

So, with that there was an experience of going in the height of the Reagan reactionary period, and Silvia and I discussed our need to take a step out of the United States. So I started again to apply for jobs, all around the world.

Silvia:

The beginning of the 1980s is neoliberalism... Reaganomics, Thatcherism, this move to the right, it’s the rise of the new model majority, which presents a big attack on women, you know, the attempt to recuperate against the feminist movement. It’s also a time of the institutionalisation of the feminist movement, so you have together these two things. On one side, there’s an affirmation of the feminist movement coming from a very institutional position - the United Nations, the American government, the more enlightened part of the government sees the possibility in using women’s labour, of using women’s demand for the economy, to relaunch their - to regain control of our work. To get out of the crisis - of the labour crisis - which they had faced in the 1970s. And on the other side, is this very right-wing, this moral majority, who wants to go back, let’s pick up our children, let’s get the women back into the kitchen. So we were confronting on one side the institutional feminists - and then on the other. so in any case, to make it short, after a while, both George and I started applying for going out of the country. We decided, let’s leave! Also, it was a time, the late 1970s, where it was very difficult to organise in New York. Because [in] 1975, New York declared bankruptcy. And that began a very very tough period. New York was the first structurally adjusted country in the world.

George:

The first position that opened up was in Nigeria.

Nigeria had a profound effect on my body, and on my sociology, and on my understanding of class struggle. Because in Nigeria, in actual practice, there was an immense amount of common land that was being used for subsistence production. Everywhere I went, the idea that, for example, ‘this is your property, this is state property’ was often taken with a pinch of salt, because most property was communal property, and it took me a long time to understand that. I remember when I looked at this big field behind my house, and I would wonder, ‘where are all these people going?’ They would walk in at any time of day or night and there would be all this cultivation going on. I thought there were all these little plots that each individual owned. But in actual fact that was not the case. This large plot of land was actually being organised for subsistence production by the village. This took some time to understand. Instead of the idea that common land was a concept that was lost sometime in the sixteenth century, we began to see that actually there was a tremendous amount of communal land, at least in Africa, that was actually existing but needed to be defended.

Silvia:

George went in 1983 to Nigeria. Then in 1984 the job I had came to an end, I was ousted from my house, I was in a real crisis and I decided to go and visit him. And very shortly after that I was offered a job, and I moved to Nigeria. And for three years I was there. Nigeria opened up an amazing... you know Nigeria was another born again. I cannot explain it how powerful that experience was. As George said, Nigeria was discovering the commons, it was discovering land. Land is a key element in a struggle.

But we went to Nigeria at a time when it was under the pressure from the World Bank and IMF to adjust its economy. There we learned about the farce of the debt crisis, we saw how the debt crisis was totally engineered, and was used as an instrument of recolonisation. That actually what they called structural adjustment was used as a tool of recolonisation. Because in the 1970s they gave a lot of loans cheaply to countries like Nigeria coming out of struggles of independence, at variable interest, almost no interest but variable, then at the end of the 1970s, the Federal Reserve raises the cost of money, and the debt, of the Nigerian or Mexican country, which had been taken, which had been manageable after the point, became unmanageable, and so begin the crisis. Because then the IMF comes in, and they use the crisis to impose structural reform, the classic structural reform. Re-adjust your economy towards export, devalue your currency, the same thing they did in Brazil. Freeze wages, freeze investment in any public service, schools, hospitals, roads, everything that is for the poor. Basically disinvest in the reproduction of your workforce. Disinvest and instead bring all this money out to your coffers of the banks in New York, Geneva, Paris, London, whatever it is. This is what we saw - so we arrived in the middle of an incredible debate, especially in the schools, in the newspaper, everybody, ‘IMF = DEATH!’ .

George:

Poison pill!

Silvia:

We hardly knew what the IMF was when we went there but we got educated very quickly! And we saw together with the attack on the university, on the student movement, came the criminalisation of so many things. They started shooting people who had stolen things. Who had stolen some yams, stolen a keg of beer, maybe they had a machete in their hands but they didn’t use it. They would have execution squads. So, to make this story short, eventually we left, we couldn’t survive any longer because our cheques were bouncing. But when we went back, for a long time, our political experience in America was shaped by Nigeria.

George:

In the late 1980s we returned to the US, and began to continue the work of Midnight Notes, a collective that we founded in the late 1970s. It was in 1989 that we began the process of putting together a general issue called The New Enclosures. We began to see that although the wage struggle was, of course, still profoundly important, the struggle for the defence of the commons against the enclosures that were taking place was another dimension that is very important to understand. The reason being that land makes it possible for workers either to refuse work or to have more power in their negotiations with the capitalists. It’s a logical point, but it has a very profound historical appearance. So this constituted my third political-intellectual discovery. Much to our amazement, after the publication of The New Enclosures in 1990, we saw before our own eyes the Zapatista revolution in Mexico. It just so happens that Silvia and I and a number of students from our university were in Mexico at the beginning of the Zapatista rebellion. We arrived on the 1st January 1994 and spent the month in Mexico. Since then Midnight Notes has had a close relationship with the Zapatista and all that that means.

Silvia:

As you know I’m 74 years old, 74-and-a-half actually. So it’s a long history. I like to see the development of my political trajectory from my childhood, because very early on in my life, from the time I could understand anything, and even before that, my life was profoundly affected by World War II. The first conversation I recall from my mother was, ‘what about the bombs falling on our head?’ - and I was a little child. For all of my childhood, whenever my parents got together and they talked, it was always about the war. So from very early I knew that I was born in a very bad world and that it was a miracle I was alive. Many tales were told of all the times that my parents escaped, just by one hair, they escaped total destruction. When I was a young teenager we moved to the countryside because my parents were kind of refugees, because our town was bombarded all the time. Then of course I came back, we returned to the town and, in my teenage years, I grew up in a town that was a communist town. Parma, part of the Red Emiglia, which at the time was very significant, because first of all the Communist Party still had some element of contestation against the social system. They were coming from the experience of the partisans. It was also significant because in the period immediately after the war, Italy went through a tremendous repression. We were liberated into a great repression. Actually, the liberation was produced mostly by the partisans. But the official story is that we were liberated by the Americans. Immediately after the war, one of the first tasks of the new government, together with the American embassy was to ensure that any possibility of a left takeover, or even a left government in Italy, would be eradicated. So this was a period in the 1950s that had the police in the factories, in which fascists were integrated into positions, and leftists in particular, working-class people, were severely repressed. In Fiat, in the 1950s, you had police in the factories.

This was the moment of the great union between the Vatican, the political structures of the American embassy and the Christian Democratic party, that was put into place practically by our ‘liberators’. Nineteen-fifty- one was the beginning of an anti-communist crusade and, because of that, to grow up in a town that was Communist was something very different. I grew up in an environment that was quite anti-clerical, and as we went to school, we were breathing a bit of a different atmosphere. Then, of course, in the end of the 1950s, in the years of high school an amazing international transformation... I was in high school when the Cuban Revolution took place... the anti-colonial struggles, I remember the stories of the Mau-Mau rebellion in Kenya. There was a sense that all over the world, despite this closure in Italy, there was a sense of forces, of the world that was changing.

I also had a great teacher, he was a mad man but a great teacher, a communist, in high school, who I think helped to form a whole generation of youth. I went to university, I studied in Bologna, and once I was finished at university, I had this desire to leave. I was really suffocated, particularly on a personal level, living at home. By this point I was in my early twenties, and I couldn’t make any money. I was working hard, very hard, doing substitute teaching, going up the mountain, getting up at five in the morning, teaching kids that, you know, the only future that they would have is to be farmers. So I decided OK, I need to see the world. I started applying for all kinds of scholarships, and the first that I got was to go to the US. So, in 1967, I went to the United States. I ended up in the town of Buffalo, because I had enrolled in Philosophy. My teacher - he was a teacher in aesthetics - wanted me to go to Buffalo because Buffalo was a centre for phenomenology, and he thought this is what I was supposed to study. In any case, I went to Buffalo, and sure enough it was a centre for phenomenology, but I met something very different. I arrived to Buffalo campus, a campus in revolt, because in the summer of 1967, two things happened - a major riot in the black community, which ended up with the imprisonment of a guy who became kind of a hero. The other was the trial of the nine youths who had tried to cross the border and been arrested, the Buffalo Nine.[18] So that’s how I was introduced to the campus - and for the three years I was there, from 1967 to 1970, the campus was always very active. At one point we had the police on campus every day, and we had them on the roofs, we had teargas, clouds of tear gas everywhere, constant meetings, so I got drawn into it in different ways. I started working for a theoretical journal that was called Telos, that was produced in the department.

* * *

Mario [Montano] and I worked an article that became ‘Theses on the mass worker and social capital’.[19] It was an attempt to apply the principles of Operaismo to a reading of the history of the class struggle in the nineteenth and twentieth century. Mario and I spent quite a lot of time together, translating, discussing and in this process he said, ‘you know, here’s all these articles, and take a look, there’s this one that’s really interesting, by these feminists’. You know, this was Mariarosa [Dalla Costa]. So I began my encounter with the feminist movement. I was in Buffalo through 1969 and I moved to New York in 1970, in fact it was 20th August 1970, everything happened in August. The feminist movement in the United States really takes off in the fall of 1969, because in the summer of 1969, there was a famous meeting [in Chicago] of SDS [Students for a Democratic Society]; they [feminists] presented their demands, they were denied and there was a walkout. A walkout of the women and the walkout of the Weathermen, these were the two things that came out of Chicago.

So the fall of 1969 was very alive, and Buffalo was one of the liveliest campuses for the growth of feminism. There had been groups of women calling themselves feminist around Shulamith Firestone, some who called themselves radical feminists, but that was really the spark, that conference, and from that moment feminism took off very strongly. Then I went to New York in 1970 and in New York - these two speak of parallel worlds, because by 1970, before meeting the Italian comrades, by 1970 I had been involved in a few feminist activities. One had been the Women’s Bail Fund, which was a broad organisation that organised around women in jail. It was an organisation that brought together different strands, it was very powerful, very interesting. There were women from the Young Lords, women from the Black Panthers, and then from the surging feminist movement. In fact, in New York, there was an organisation called WITCHes, Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell.

In 1972, after I read Mariarosa’s article, for me it was like, ‘this is it!’, because I had all these questions, but to me it made perfect sense. So this happened in the spring, in the summer I went to Italy, and I went to Padua, at the time there was going to be a big meeting. At the end of this we had another meeting, and at the end we formed the International Feminist Collective, this was July 1972. We went separate ways with the common idea that we would all form a common network that would launch a Wages for Housework campaign in our respective countries. And that’s what I did. For the next few months, when I went back to New York at the end of August 1972, I began to look for people who would want to do things. I met another woman from Switzerland, Nicole, and we started doing some stuff together, but it was only early in 1973, when Selma and Mariarosa came to the US for a political tour that the group took off. It’s very easy, you know, when someone comes from outside, they come to speak, there’s enthusiasm generated. So we took the enthusiasts, we started having meetings, and that’s how the Wages for Housework Collective was born. We called ourselves a committee, and then by the fall of 1974 we had our first international conference. And by that time we had groups, we had a little network. We had women from Italy, from England, from Canada, from Philadelphia, some from Boston. And at the end of the meeting we wrote a manifesto: Theses on Wages for Housework.[20]

George:

Ideas don’t come from a light-bulb moment in someone’s brain. Ideas come from struggles - this is a basic methodological principle. It’s when the wageless begin to speak... and let’s not forget that Marxism and the interpretations of Marx have been open to many interpretations. When we say ‘traditional Marxism’, we only mean one strand, because Marx’s texts - if we are going to take them as the origin of our discussion - Marx’s texts are open and are for reconsideration. This is what makes it possible for us to continue dealing with Marx and Marxist texts, because often you are asking yourself ‘Why am I dealing with this twenty-first century phenomenon using a nineteenth century theory?’ It has to do with the fact that the theory that you’re using has been transformed by many people in and through struggle.

The anti-colonial struggles forced us to stretch Marx’s concepts. This is what [Franz] Fanon said he had to do. The reason he had to do this was because he was working with unwaged labourers. Workers who are on the verge of slavery in the colonial interior. So the colonial class struggle needed to have new categories. But not new, because the unwaged workers or low-waged workers in the colonies, and the waged workers in France or England, were connected, both materially and via capital. Also other struggles, because the anti-colonial struggle included Vietnam and that was the source of so much of our politics - a support for movements that were demanding control over their land. I think that the question of Marxism and the interpretation of Marxist texts is still very open. Because this is what’s happening now, and I am very pleased to see that there has been an interest in Marx’s work from an ecological perspective. Often you realise that when Marxists are saying this, it’s a stretched Marx.

The question is whether the stretch breaks the rope, right? I think our interventions - the introduction of the struggle against work as a field throughout this society and the conception of the struggle of unwaged workers in reproduction of labour-power - are essential to our understanding of capitalism. The whole conception of the commons, in the capitalist sense, to enclose the commons, these are ways of restructuring our understanding of capitalism. So now we look at the chapters on primitive accumulation [in Capital, vol. 1], not as a distant conclusion or as a line of argument, but actually as the foundation of our understanding of capitalism, as well as of Marx’s texts. This is my understanding of the story of where we are with Marx and Marxism. With these key questions, politically and textually, you have to ask yourself, why are you reading this?

Notes

The conversation took place in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in 2016. It was transcribed by Gloria Loris and abridged by Barbagallo, Beuret and Harvie.

2. Comradely Appropriation

Harry Cleaver

Some years ago, while teaching a course on the political economy of education - created in response to demands by activist students - I experimented with an alternative to ‘testing’. I asked students to write about what, if anything, of the ideas we were studying they could appropriate for their own purposes - as useful to the further elaboration of their personal trajectories, both intellectual and through life in general. I thought this rather straightforward, in as much as I had long studied in this manner.

Upon reading their first essays, however, I discovered that most were puzzled by what I was asking them to do. In response, I eventually drafted an essay on ‘Learning, Understanding and Appropriating’ to explain and illustrate the kind of self-reflection I had in mind.[21] Some of the illustrations were excerpted from classical autobiographies by Marcus Aurelius, Augustine of Hippo and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. But suspecting that they might be able to relate better to a more immediate example, I recounted a few of my own appropriations - from my school years - elementary through graduate school - in which new ideas had an impact not only on my thinking, but also on my behaviour, in some cases on my political actions. The last of those examples concerned my return to Marx after completing my PhD, because of dissatisfaction with the ability of the Marxist writings I had been using to frame my dissertation to adequately illuminate the history I had discovered while writing it. That return began shortly before encountering, evaluating and appropriating some ideas from George and Silvia in the mid-1970s. Although I have learned much from both in the years since, I describe below some of those early appropriations that led to changes in both my thinking and my political behaviour. First, some background.

George, I have known since our undergraduate years at Antioch College in the early 1960s, where we spent many a long evening listening to ‘cool’ jazz, debating Sartre, the Beats, imperialism and many an other subject. (Probably the most important thing I discovered through George in those

days were the writings of Nikos Kazantzakis.) We also marched together in a civil rights demonstration in Yellow Springs, were arrested and shared a Greene County jail cell. Thereafter, our studies and jobs led us along different paths, somewhat parallel but distinct. I pursued graduate studies in economics at Stanford; George did the same in the philosophy of science at Princeton. We were both heavily involved in the anti-Vietnam War movement. While I was digging up dirt on Stanford’s involvement in the war and helping Professor John Gurley put together his first course on Marx, George was reading Marx and collaborating with Marc Linder and Julius Sensat to prepare chapter-by-chapter critiques of Paul Samuelson’s iconic textbook Economics - eventually published by Linder as Anti-Samuelson (1977). After graduate school, I went off to teach in Quebec at lUniversite de Sherbrooke, while George found a teaching job at Haverford College in Pennsylvania. Our geographical paths converged in New York City in the fall of 1974 when I accepted a job at the New School for Social Research; George had found one at Brooklyn College of CUNY the year before.

Silvia, I met through George after moving to New York City. She was, at that time, a stalwart member of and important spokeswoman for the Wages for Housework Movement/Campaign. She would soon be publishing - and I would be reading - influential essays as contributions to that Campaign.

In the exciting, often urgent, back-and-forth of collective thinking and struggle, I have often found it difficult to pinpoint the unique contribution of individuals to the unfolding of ideas and political action. I first realised this during the anti-Vietnam War movement. Sustained collective efforts, I discovered, engage large numbers of people, from different backgrounds, who draw upon a variety of ideas and political orientations to undertake a wide variety of activities that contribute to the growth and effectiveness of collective action. The form and content of individuals’ contributions may vary over time, shifting with collective needs - doing research at one moment, writing an article or pamphlet at another, handing them out at yet others, organising food or baby-sitting during building take-overs, participating in organisational meetings again and again. Each of these contributions is influenced by past ideas, recent reading, contemporaneous conversations and debate - all involving other people’s ideas and actions, often those of many other people. True during the anti-war movement, true amongst those who supported the Wages for Housework movement, which developed in New York City in the mid-1970s.

That period was one of global crisis for post-World War II Keynesian (or Fordist) policies - a crisis caused by an international cycle of workers’ struggle.[22] The capitalist response included both anti-worker austerity and monetary manipulations, foreshadowing the strategies of neoliberalism at a global level. Locally, in New York City, the crisis took the form of a ‘fiscal crisis’ in which city government borrowing to cope with workers’ struggles, especially those of city employees and those on welfare, were suddenly cut off by its lenders, the big banks, which refused to roll over the government’s debt.[23]

Against this backdrop, women organised the local Wages for Housework (WfH) Campaign, almost completely autonomously from men. Such autonomy was not new in the United States; many women had been organising autonomously since the self-organisation of second-wave feminism in the late 1960s. One implication for men who supported such efforts was to undertake their own separate organisational efforts. Amongst those with whom I began to collaborate after moving to the city, the results were twofold. One, launched before I arrived, was Zerowork, first a collective of men located in the United States and Canada and then a journal of the same name, prepared as a political intervention into Left discussions debating the crisis of Keynesianism. The other result was the formation of militant groups, one of which called itself New York Struggle Against Work (NYSAW) that organised opposition to local austerity programmes.

Those in both Zerowork and Wages for Housework drew on ideas and previous political experience from both sides of the Atlantic, dating - I would later discover - back to the 1940s.[24] More recently, those ideas were elaborated with exceptional theoretical refinement in Italy by opponents of the policies of the main left-wing political parties and trade unions, which had been collaborating with Italian capital’s efforts to rebuild after World War II. Eventually the internal gender dynamics of such opposition led to women organising autonomously from men - as had similar dynamics in the American anti-war and student movements. Central to much of that opposition were notions of the ‘refusal of work’ - as a strategy pitted against capitalist development - and demands by groups such as Potere Operaio that some unwaged work, such as that of students, be recognised as work- for-capital - producing their own labour-power - and be properly remunerated. That recognition flowed from a more general understanding of how capital, through social engineering, has sought to extend its management from the shop floor throughout society, turning it into one large social factory.

The case for capital paying wages for the housework of producing and reproducing the labour force was most clearly enunciated by women, a renewal of a demand that had been made, off and on, by previous generations of women since the early twentieth century. The key text that set out a clear Marxist analysis of the role of housework in capitalism was written by Mariarosa Della Costa for a women’s group in Padua, Italy in 1971 and was titled Donne e sovversione sociale, usually translated as ‘Women and the Subversion of the Community’.[25] That essay became a founding document for both an International Feminist Collective and the Wages for Housework Campaign. As that Campaign spread across Europe and the Atlantic to North America, the essay also set off a firestorm of opposition.

The argument that women should fight to be paid for their labour producing and reproducing labour-power infuriated a wide range of leftists who promptly attacked both the strategy and the underlying theory. One bit of heated opposition echoed old arguments against wage struggles in general and can be summarised as ‘a little more money for waged workers or a little money for the hitherto unwaged doesn’t change the social relationship, the one strengthens existing chains and the other creates new ones’. Flaming opposition to ‘creating new chains’ was particularly strong among those who defended the home as an oasis of healing and solace from the ills inflicted on waged labour and argued that to demand wages for housework amounted to inviting capital in, which would inevitably pollute that oasis. One line of theoretical attack argued against the idea that unwaged housework resulted in more surplus value. It was wrong, some claimed, to equate unwaged housework with surplus-value-producing waged labour. As you might suspect, those of us in New York Struggle Against Work read these attacks and debated their validity.

Although George and I had been friends much longer, and were both members of the New York Struggle Against Work group and contributors to Zerowork, I want to begin with a discussion of how Silvia’s response to that firestorm of opposition offered ideas and analyses that not only NYSAW and the Zerowork Collective adopted, but that I, personally, appropriated as important new weapons in my efforts to understand and oppose capitalism.

Silvia:

In 1975, in response to those heated attacks, Silvia wrote two essays, Wages Against Housework, and Counter-Planning from the Kitchen, both originally published as pamphlets by Falling Wall Press in Bristol, England, but quickly circulated throughout the Campaign.[26] The very title of Wages Against Housework, as the essay explained, emphasised how the demand for wages for housework was not merely a demand to be paid, but a means to force recognition of the value of housework to capital and a vehicle for this hitherto unwaged mass of workers - mostly women - to be accepted as integral parts of the working class and their struggles to be valorised as every bit as vital as those of waged workers. The demand for wages for housework, she argued, was a political perspective on both the dynamics of capitalism and prospects for transcending it.

This perspective offered an alternative to a tendency by some on the left, ever since Citizen Weston, to dismiss wage struggles as futile,[27] and since Lenin to marginalise them as ‘economistic’, not rising to the level of the class interest as defined by the Party. Nevertheless, most of those who support struggles against capitalism have recognised that wage workers winning higher wages (or avoiding cuts), if they lead to new, more comprehensive demands, can be intermediate steps on the way to the revolutionary abolition of wage system and capitalism. And that, Silvia argued, was the character of the demands by the unwaged for wages. She wrote, ‘To say that we want wages for housework is the first step towards refusing to do it, because the demand for a wage makes our work visible, which is the most indispensable condition to begin to struggle against it.’ Making visible how housework serves capital, she argued, strikes at the heart of a fundamental vehicle through which capital controls workers - the division between waged and unwaged - and lays the basis for working class collaboration across that divide.

Unlike too many workers, Silvia and others in the WfH Campaign argued, capitalist policy makers understand the essential role of housework and their understanding has guided policies made in moments of crisis. Some such moments have followed wars, e.g. World War I, where high death rates depleted the ranks of the labour force and capital, through the state, enacted pro-natalist laws that paid women to have more children. When forced, by working-class struggle, to generalise such policies, however, those policy makers cloaked their concessions under the rubric of ‘welfare’ rather than admit they were paying for housework. The political problem, to which the Campaign offered a solution, was to reveal how such payments amounted to a camouflaged form of wages for procreation and child rearing, for the work of producing labour-power.[28]

This demand for making unwaged work-for-capital visible, in a way that exposes its integral role in the expanded reproduction of capital, struck me forcibly. Marx had made the point of how the wage hides the existence of exploitation. However, when he analysed the unwaged in the various ranks of the ‘surplus population’ or ‘reserve army of labour’ - he did not apply the kind of reasoning that Silvia was making in this essay. How unwaged housework in the home, or schoolwork in schools, was structured to produce and reproduce labour-power - the key commodity in capitalism, the one that makes all the others possible - was clear enough. But I came to her essays almost directly from writing a dissertation on capitalist efforts to manage the struggles of unwaged peasants in the Third World. What about their work? And what of the work of others in the ‘reserve army’?

The theory that had guided me in studying capitalist efforts to deal with peasant unrest, at least to some extent, was appropriated from Marxist anthropology, one that framed such efforts in terms of the capitalist mode of production imposing itself on non-capitalist ones. This fit with another traditional Marxist tendency to generalise Marx’s analysis of primitive accumulation in Britain in a way that led to seeing all peasants not yet pro- letarianised as outside of capital and their struggles marginal, doomed and irrelevant to those of waged workers. Even Mao, who discovered in 1927 that peasants had started the revolution without him, sought to subordinate them to the Party, which he thought represented the interests of waged workers. The mode-of-production framework could identify, but offered no tools to analyse, the struggles of peasants, or to situate them as moments within accumulation - understood as the accumulation of antagonistic classes in conflict.

My studies of capitalist agrarian policies in the post-World War II period had shown me the continuing relevance of Marx’s location of peasants - ‘those working in agriculture, not yet repulsed from the land’ - in the latent ranks of the reserve army. At that time, partly as a result of their analysis of the ‘loss of China’, capitalist policy makers frequently supported land reform. Whether in Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, the Philippines, India or elsewhere, they sought, by responding positively to peasants’ struggles for better access to land - by legal changes in either tenure or ownership - to stabilise the peasantry as a non-revolutionary labour reserve. Not motivated by some version of Jefferson’s agrarian democracy, the objective was to keep them on the land until needed elsewhere, at which point various measures could force them from the latent into the ranks of the floating reserve, i.e. joining others actively looking for waged jobs. Within such a situation, Silvia’s analysis, by focusing on the work of the unwaged, provided further insights.

Although her essay didn’t discuss labour-power in exactly these terms, I found her analysis of housework a nice illustration of my own formulation of labour-power as ‘the ability and willingness’ to do commodity-producing work for capital. She pointed out how women had to be convinced to do housework - be made willing - by various means, from being taught it was in their nature to the seductions of romantic love. Like Simone de Beauvoir before her, Silvia painted a picture of how so many women have discovered, to their dismay, that the apparently rosy path to life as beloved wife led through a gloomy, dark wood to a domestic hell of endless and often thankless work - all too often including psychological and physical abuse.[29]

In the case of peasants, both their attachment to the land, often spiritual as well as material, and the satisfaction of having autonomous control over their lives, in both work and non-work, has often meant only dire necessity - forcible enclosure or the threat of starvation due to flood or drought - could convince them to search for waged jobs. Certainly, this was the case during the early centuries of capitalist development when waged jobs off the land could only be found amongst the satanic mills and teeming pauperism of capitalist cities. In more recent years, with the development of those cities and mass media portrayal of their bright lights, diverse entertainments and illusions of hopeful futures for everyone ‘willing to work hard’, less force and poverty has been required to seduce many young people to leave the land. What they have found, of course, has often been like the discoveries of love-besotted women, a hard-scrabble existence in barrios and favelas where good waged jobs are few, steady income hard to come by and survival dependent on integration into the networks of the so-called informal sector.

Those in the ‘welfare’ sector of the latent reserve share conditions of life similar to both those in the informal sector and job hunters. With welfare payments kept near subsistence, to remove any disincentive to move from the latent into the floating reserve, living on those low payments is far more work than normal housework for those with access to a decent wage. Moreover, just as those seeking unemployment compensation have to provide evidence of job search, so too have those on welfare been forced to expend vast amounts of energy meeting the requirements of welfare officials.[30]

I eventually realised, in reading Silvia’s essays and then discussing them with others in our New York Struggle Against Work group, that she and other feminists before her, whether thinking in Marxian terms or not, were replicating, in the case of unwaged housework, the kind of close analysis of both the technical division of labour and the political composition of factory work that had been undertaken by Marx in the nineteenth century and renewed, after World War II, by some of his followers on both sides of the Atlantic. Men such as Martin Glaberman, Matthew Ward and Paul Singer in the United States, G. Vivier and Daniel Mothe in France, Danilo Montaldi, Romano Alquati and Raniero Panzieri in Italy, had taken up, once again, Marx’s efforts to analyse and understand exactly how capital imposed waged work on the shop floor and how worker resistance led to changes in the forms of that imposition.[31] I saw that just as these men had studied this in factories, and Silvia had studied it in bedrooms and kitchens, so too could we study, in a similar manner, every other sphere of activity of the unwaged - throughout Marx’s ‘reserve army’ and beyond. The immediate implication was that his army was ‘in reserve’ only in relation to waged work; capital has been very busy in the years since he wrote trying to organise the activities of those ‘in reserve’ as work contributing to the expanded reproduction of the class relation.

All workers in the floating reserve, for example, face the problem of finding jobs, not just recent rural-urban peasant migrants. Looking for work is work, not just in the sense of requiring a lot of effort, but because it produces and reproduces the labour market! In a few cases, capitalists - in the form of labour contractors for low-waged positions or ‘head-hunters’ for high-waged ones - actually go out and search for workers. But more often, workers must shoulder the frustrating work of looking for jobs. For the most part, only the ‘supply’ side of the market searches; the ‘demand’ side sit at a desk, and wait for anxious workers to knock on factory gates or office doors and beg for a job and a wage or salary. For some, looking for work only requires local efforts; for others, it requires dangerous treks across borders, deserts or oceans, risking the violence of all those who prey upon or repress multinational workers. Those waged workers who have lost jobs and need some form of ‘unemployment compensation’ to carry them over while they look for a new one, often must prove that they have actively sought jobs by providing evidence from job interviews. Analysing what economists call ‘job search’ in the ways Silvia analysed housework reveals it to be work for capital. Usually treated as a kind of welfare, ‘taking care of those willing souls who have lost their jobs through no fault of their own’, ‘unemployment compensation’ actually amounts to payment for the work of making the labour market function.

But if everyday life for those in the latent and floating reserves involves the work of producing and reproducing labour-power, and sometimes making the labour market function, what of the stagnant, that third sector of Marx’s ‘surplus population’? Examination of his discussion of this sector in Chapter 25 of Volume I of Capital reveals that those he included in this sector consisted of people who were working, some waged, some unwaged, but still contributing, in one way or another, to accumulation. Indeed, the ‘chief form’ through which such workers were organised, he identified as ‘domestic industry’ - outsourced labour, working in homes or tiny workshops - what a hundred years later Italians would call la fab- brica diffusa or diffused factory. Workers employed in this way were only ‘surplus’ to the factory proper, and were stagnant mainly in the sense that, alienated from the higher-waged factory proletariat, they had little chance of improving their condition and could gain income only in the worst jobs at the lowest wages. Also as part of this sector, he included the lumpenproletariat - vagabonds, criminals, prostitutes - and those too old or too disabled to work at waged jobs.

But within the ranks of this stagnant reserve, Marx clearly saw resistance, e.g. the unwillingness of vagabonds and criminals to look for waged jobs.[32] Their refusal of the labour market we can see as akin to the resistance of peasants to being forced off their land - a refusal so strong as to require the ‘bloody legislation’ described at length in Chapter 28 of Volume I.

Shifting focus from capital’s efforts to impose work on the unwaged to their resistance, reveals whole new realms of working-class struggle. In the United States, think of the march of Cox’s Army of the Unemployed in 1932, a revolt by members of the floating ranks of the reserve army. Or, of efforts of Welfare Rights and student movements of the 1960s, also members of the latent ranks demanding compensation for the work of producing and reproducing labour-power. Or, the ‘EMA [Educational Maintenance Allowance] Kids’ of Britain’s 2010 student movement. Or, of those increasingly militant demands made by members of the Black Power and Brown Power movements, often seen as rising from the ranks of Marx’s lumpenproletariat. Or, the armed peasant resistance in rice paddies, rubber plantations and jungles to forcible subordination to colonial or neocolonial exploitation. And finally, of course, the swelling revolt of women - both waged and unwaged - that gave birth to, among other efforts, the Wages for Housework Campaign and Silvia’s analysis.

This shift in focus, was highlighted as the first methodological principle enunciated in the Introduction to the initial issue of Zerowork.[33]

First [we begin with] the analysis of the struggles themselves: their content, their direction, how they develop and how they circulate. It is not an investigation of occupational stratification nor of employment and unemployment. We don’t look at the structure of the workforce as determined by the capitalist organization of production. On the contrary, we study the forms by which workers can bypass the technical constrictions of production and affirm themselves as a class with political power.

The second principle derived explicitly from the work of Silvia and others in the Wages for Housework Campaign.

Second, we study the dynamics of the different sectors of the working class: the way these sectors affect each other and thus the relation of the working class with capital. Differences among sectors are primarily differences in power to struggle and organize. These differences are expressed most fundamentally in the hierarchy of wages, in particular, as the Wages for Housework movement has shown, in the division between the waged and the wage-less. Capital rules by division. The key to capitalist accumulation is the constant creation and reproduction of the division between the waged and the unwaged parts of the class.

This explicit derivation was a clear statement of how those involved in producing Zerowork had appropriated the arguments in Mariarosa Dalla Costa’s original essay and in Silvia’s responses to critics.

My own writing of that period also made my appropriation of these ideas explicit. First, in a 1976 essay for a conference at the Sinha Institute in Patna, Bihar (India) later published in the Economic and Political Weekly (Mumbai), I critiqued the results of applying mode-of-production analysis to the Indian peasantry and offered the kind of analysis laid out in Zerowork as an alternative?[34] 'Then, in a 1977 essay for the second issue of Zerowork on ‘Food, Famine and International Crisis’, I applied the analysis more or less worldwide, West and East, North and South, to understand the widespread famine and food riots of the 1970s and as an intervention into the ‘food movement’ that had arisen in response to famine?[35] In the years since, these ideas have informed many of my essays on various topics. The debt has been long-lasting.

George:

Because George and I both participated in the NYSAW group and in the Zerowork collective, and because of many conversations during the summer of 1975, when I was rethinking Marx’s labour theory of value, through 1975-6, when I was elaborating a critique of the mode-of-production analysis to understand the relationship between capitalism and the peasantry, it is difficult for me to identify, precisely, all of George’s unique contributions to the evolution of my thinking in that period. However, one set of appropriated insights, easy to point to, were plucked from George’s contribution to the analysis of schoolwork and the struggle against it.

During the NYSAW struggles in New York City, and during the preparation of the first issue of Zerowork, George collaborated with two graduate students, Monty Neill and John Willshire-Carrera studying ‘radical’ economics in the Graduate Program of Economics at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. George and the students together wrote and published a critique of education: a pamphlet, in the form of a blue book, titled Wages for Students.[36] Drawing on the theoretical framework of WfH, the pamphlet analysed schoolwork as work-for-capital, primarily structured to impose work discipline for the benefit of future employers. The essay critiqued the usual arguments by economists that education is both a consumption good and a good investment. The former, they argued, was patently false because schoolwork is work and gets in the way of consumption. The second was no longer true on a personal level because high unemployment in the 1970s made future payoffs less likely. Left professors’ support for extra work, in the name of raising social and political consciousness, they also claimed, merely forwards capital’s agenda. Pointing to how student wagelessness put a burden on parents or forced students to add waged jobs to their unwaged schoolwork, the essay argued that regular students should be paid by capital much as some corporations pay for employee training. This demand clearly echoed the one made by Potero Operaio in Italy that had influenced Mariarosa Dalla Costa’s analysis and the demand for WfH. Many of the ideas elaborated in their pamphlet were incorporated into George’s contribution to Zerowork #1: ‘Throwing Away the Ladder: The Universities in the Crisis’.[37]

As with the other essays in Zerowork, his essay offered an analysis of concrete, historical developments in the class struggles that had brought on the crisis of Keynesianism mentioned above. In it, he traced how the crisis of education had been brought on by student struggles and how capitalist counterstrategies included abandoning the old ‘career ladder’ in favour of a set of precarious footstools. It was also the only essay devoted solely to the unwaged.

Having been engaged in student struggle and, like George, having become one of those ex-protestors who had found a spot teaching, his article - written before I joined the collective - was of particular interest to me. His analysis of student struggles rang true and his analysis of recent capitalist responses brought new aspects of the conflict to my attention. My appropriation of elements of his analysis - especially the emphasis on how student struggles often involved a refusal of work - quickly informed both my retrospective understanding of the struggles in which I had been involved and my teaching behaviour. Here follows a few words on each.