Joey Hong

In Defense of Lovesickness

I indict our mass intoxication with capitalism for the loss of lovesickness. By this, I do not mean to suggest our society entirely overlooks the experience of lovesickness. However, a toxic dating culture, steeped in capitalism, viewing individuals as selectable and replaceable goods, is playing a significant role in the elimination of lovesickness from our radar. Philosopher Byung-Chul Han refers to this tendency in his book The Agony of Eros as the “overabundance of options” within capitalist society. This makes it impossible for one to experience eros, a concept defined as “a relationship to the Other situated beyond achievement, performance, and ability.” Put simply, eros is not just a romantic or sexual desire, it is a deep connection with a stranger transcending material advantages. This endangered eros threatens capitalist values.

We may call this the neoliberalization of dating culture—people seek partners as they search for books, based on blurbs and ratings. These days, people simply do not have enough time to be lovesick. Why should you suffer? If your beloved is not meant for you, simply look for a better and more suitable “option” out there in the market. In users’ dating app profiles “qualifications” are advertised as attractive “goods” with marketable perks such as educational background, annual income, hobbies, body measurements, and even MBTI types. The goal is to land the “best” choice based on a prospective partner’s “product details.” Not right for you? Swipe or scroll on. At the same time, promote yourself effectively by following some tips!

After one achieves this “love,” it is treated as an investment—one should commit only if the returns are certain and worthwhile. Loving someone who may not return our feelings risks relinquishing control over individualism, self-optimization, productivity and, perhaps, a future. Capitalism instead urges us to spend time efficiently; we must always be “moving on” and “growing” rather than longing or pining.

Non-instrumentalized love works differently. It can’t satisfy the capitalist market since it is not an investment. How else are we to explain elusive yet persistent “love at first sight”? Often, love occurs without data or statistics about the object of desire. In The Oxford Handbook of the Philosophy of Love, philosopher Aaron Smuts introduces the “no reasons view”: love is not replaceable like products, and we are frequently drawn to love not based on a person’s particular qualities, but out of groundless attraction. Smut’s perspective resonates with Han’s concept of eros, embracing the Other “beyond” merits.

If love is so unquantifiable, why is an intense and unconditional crush so, well, valuable? At a glance, lovesickness is no more than an adolescent whim or turmoil that one should grow out of—the faster, the better. This is not entirely wrong. Lovesickness taxes the body and emotions, leading to depression, insomnia, and loss of concentration.

Nonetheless, I defend lovesickness precisely because it challenges capitalism’s craven emphasis on meritocratic lifestyle while opening up us to uncharted adventures. Lovesickness refuses constant productivity; with lovesickness we may exit the rat race and possibly we can evolve into a less instrumentalized state.

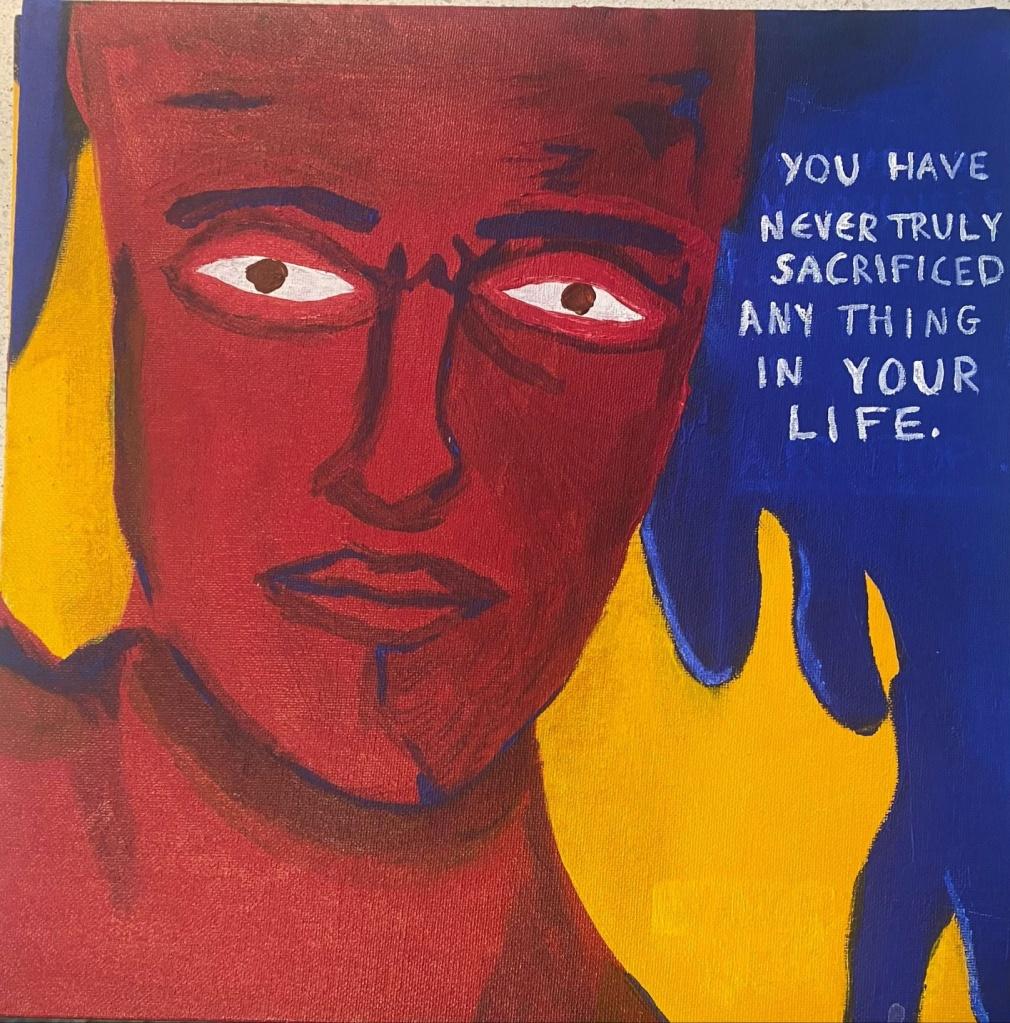

In his discussion of love, Byung-Chul Han critiques “achievement society,” a culture “dominated by ability, and where everything is possible and everything occurs as an initiative and a project.” In other words, the achievement society stresses individuals’ agency and ability to win something they desire by self-exploitation. This mode of life sustains neoliberalism, prompting people to stay productive, efficient, and competitive. However, lovesickness rejects meritocracy by opening up powerlessness. In a state of lovesickness, infatuation is neither predictable nor controllable. An input of labor into a desired relationship may not earn the output of the beloved’s heart. Simply, love does not play by the rules of productivity. You can’t earn it. Or, in the infamous words of the Beatles, Can’t buy me love.

Lovesickness also embodies “queer temporalities” coined by Jack Halberstam in In a Queer Time and Place. In other words, it refutes capitalism’s obsession with “heteronormative time.” In heteronormative society, life is expected to follow a clear trajectory—meet, date, commit, and settle down! This heteronormative, linear progress reflects the logic of capitalist productivity, where every phase of life must be a means to an end. In love, this goal is often reproduction. Love masks the compulsory dictum to form a nuclear family and reproduce a future labor force to sustain the capitalist market.

Lovesickness, in contrast, disrupts this linear progression. It leaves us suspended in longing, desire, and uncertainty rather than propelling us to keep moving forward into the reproductive future. To put this idea differently, lovesickness serves as an alternative temporality that helps us reclaim the right to linger in love and to embrace the uncertainty of longing. At the same time, lovesickness opens us to self-discovery: we might discover new ways of feeling and learn more about our desires and preferences as we grapple with loss and lack.

From the capitalist perspective, lovesickness is merely an obstacle in one’s fast-paced, over-achieving life. It undermines work productivity, courting uncertainty and liminality. However, without this risk, how are we to mature, gain courage, or embrace the open-endedness of life?

Lovesickness is an excitingly paralyzing aspect of human existence, especially considering that the object of love may not even necessarily be a human being. One may long for participation in an activity, a dwelling, or an egalitarian society. This yearning may never be achieved. But its pursuit will be a source of learning, even if it is only the lesson taught to us by Lauren Berlant, that capitalism offers the dreamer only “cruel optimism.”

I am not arguing that love is inherently painful nor that we should pursue a masochistic course of suffering. Nor am I saying that we should never give up on our love objects. Rather, lovesickness exposes us to a mode of life in which loneliness or lack need not always be swiftly resolved or optimized. By dwelling in feelings induced by lovesickness, we may discover new aspects of ourselves, our desires, and the world—a transformative adventure, so to speak.

I do want to believe that this “adventure” will expand our universe and perspective about life. Down with capitalism; long live lovesickness!

Author Bio

Joey Hong is currently a PhD student in English.

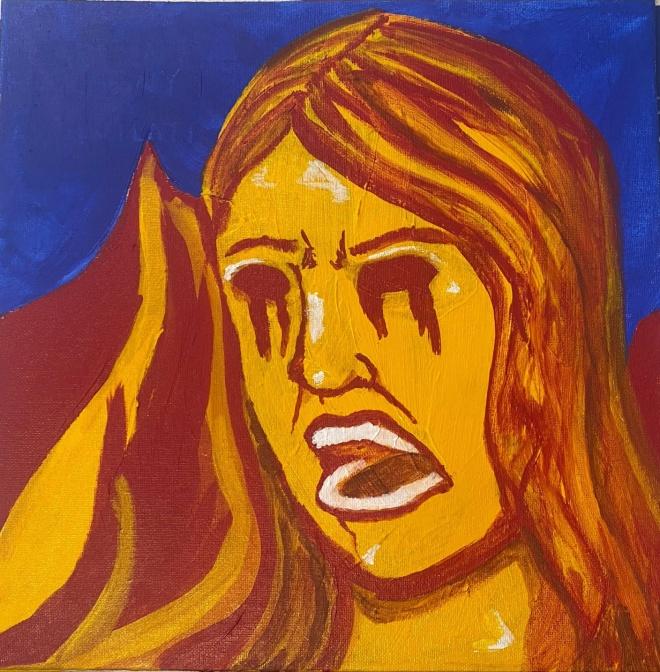

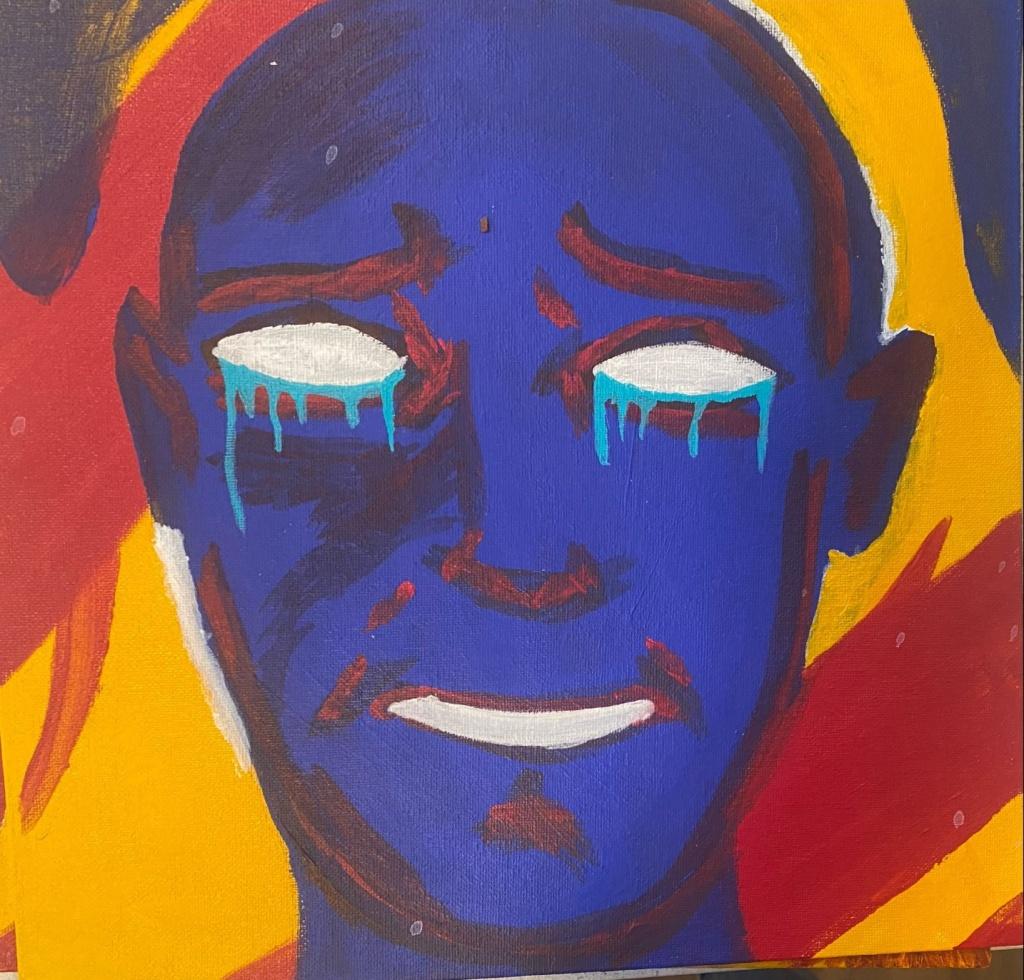

Artist Bio

Addison B. Conn is a second-year PhD student at Washington University in St. Louis and he studies Black literature and design in fiction. He is currently working on designs of animality in Harlem Renaissance literature. He loves to paint, do collage, and read.