Juanita H. Williams

Psychology of Women

Behavior in a Biosocial Context

1. Myths, stereotypes, and the psychology of women

Woman as enchantress-seductress

From Myth to Stereotype: The Virtuous Woman

The Psychology of Women: Philosophical Origins

A minor theme: the argument for equality

The Psychology of Women: Science and Social Values

On Understanding Women: Contributing Sources

2. Psychoanalysis and the woman question

The early development of psychoanalysis

Freud’s theory of female development

Psychoanalytic research and psychotherapy

Epilogue: Emma Eckstein and the seduction theory

Narcissism, passivity, and masochism

Sexuality and the feminine role

Psychosocial development: the “eight ages of man”

Sex differences and the use of space

3. Woman and milieu: innovative views

4. Sexual dimorphism, biology, and behavior

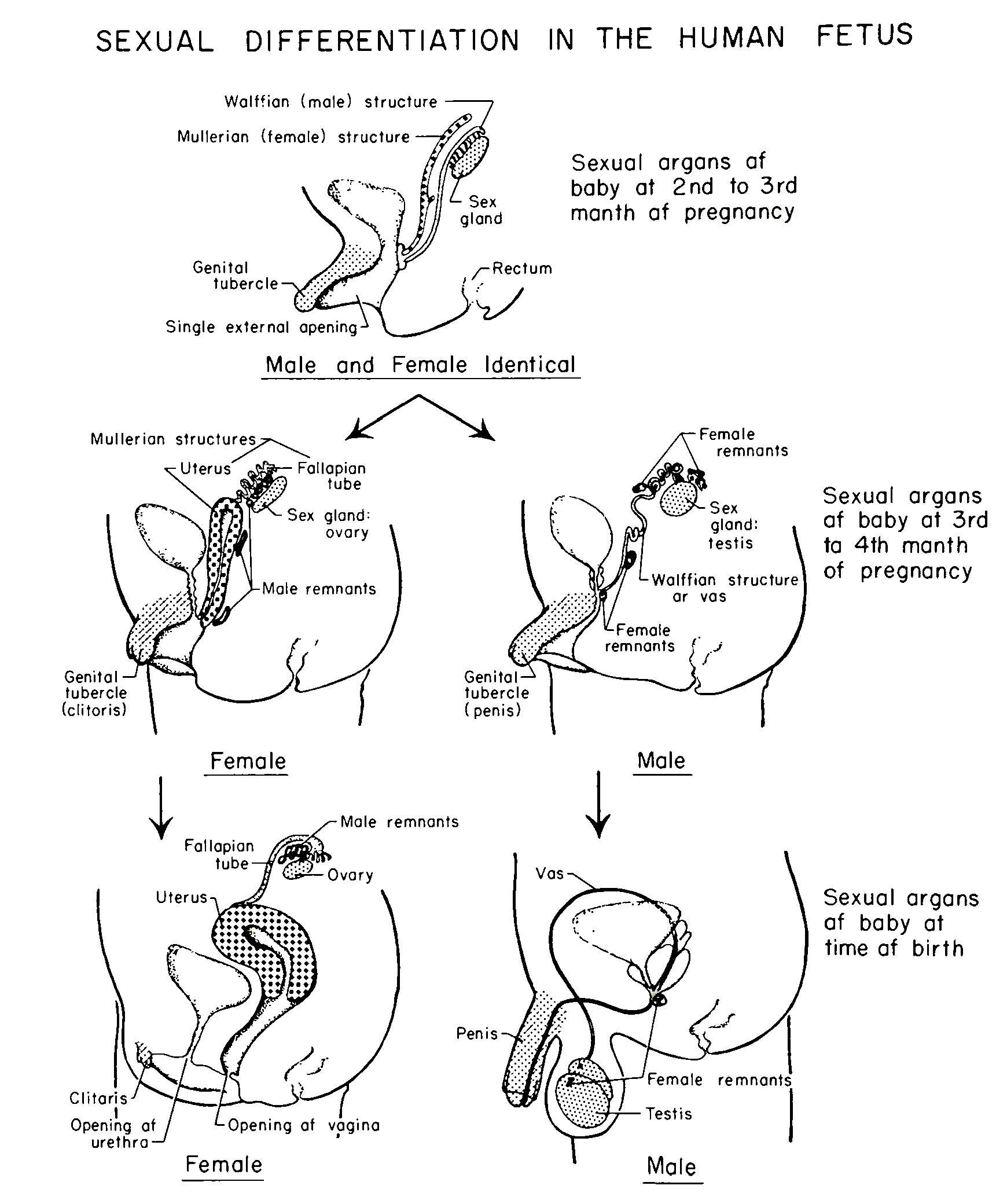

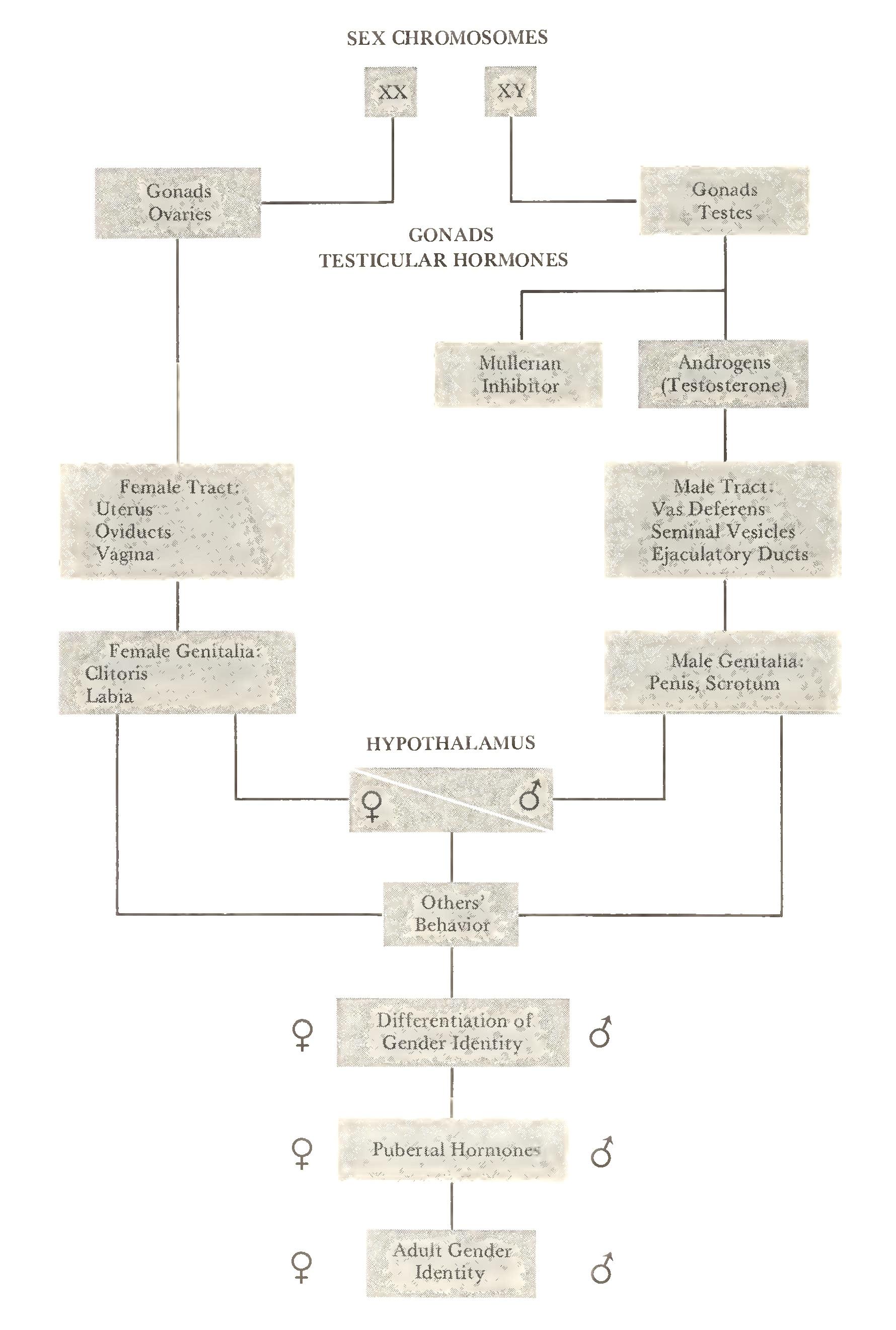

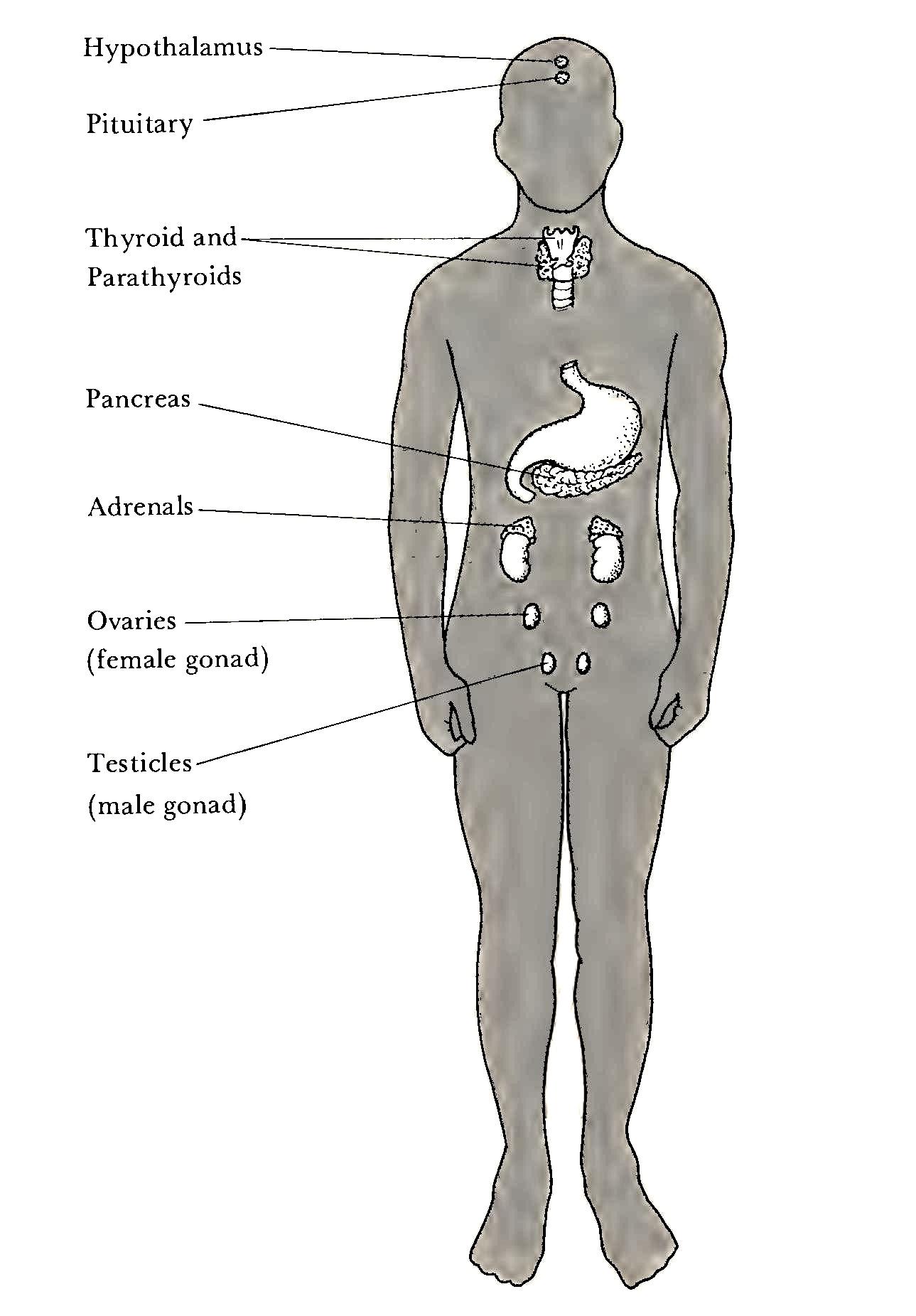

Determinants of Sexual Differentiation

The animal model: experimental studies

Puberty: Physical and Hormonal Changes

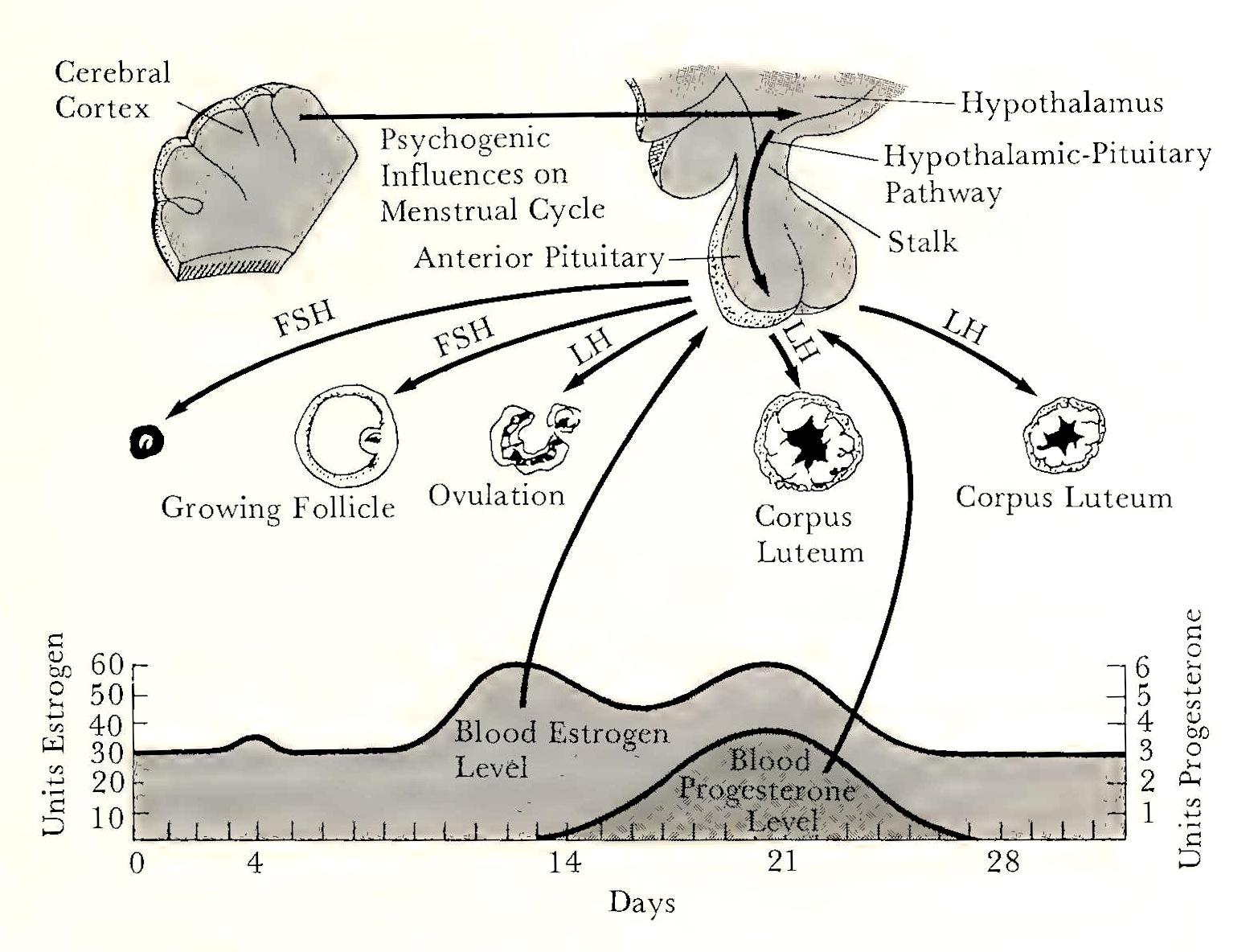

Menarche and the Menstrual Cycle

Dysfunctions Associated with the Menstrual Cycle

Behavior and the Menstrual Cycle

Why Do Women Live Longer Than Men?

Sociobiology: The New Biological Determinism

5. The emergence of gender differences

Social class and cognitive development

Determinants of gender differences

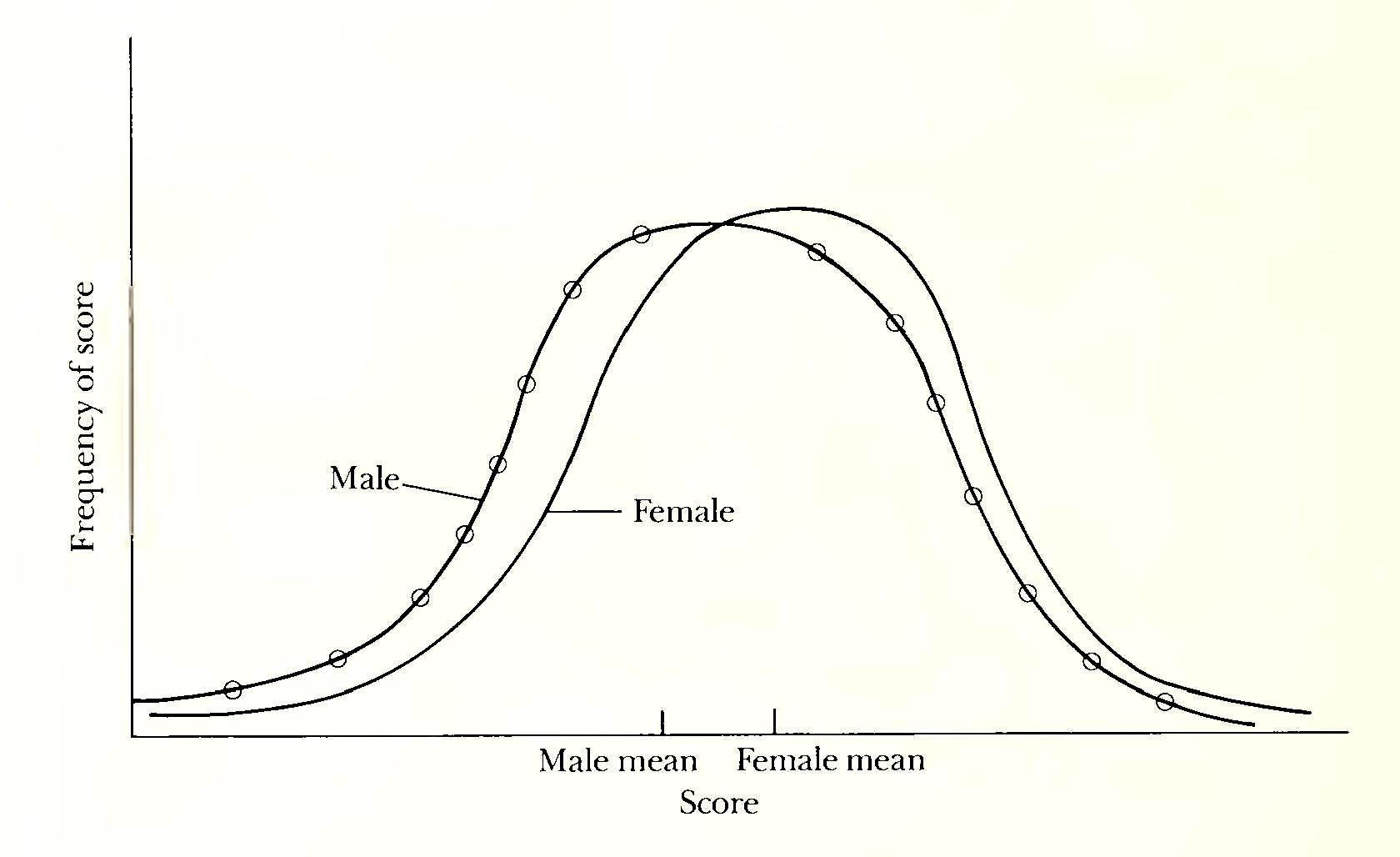

What Do We Know about Gender Differences?

Cognitive-developmental theory

Development of Gender-Role Identification

Parental Identification in Adolescent Girls

The Daughter-Parent Relationship

The mother-daughter relationship

The father-daughter relationship

Sex Typing and Socialization Experiences

The Menarche: Socialization Effects

Achievement: Conflict and Resolution

Other Influences on Achievement

The Development of Competence in Girls

Moral Development: In a Different Voice?

Women and Sexuality: Historical Perspective

Only Yesterday: The Victorian Context

Etiology of Sexual Dysfunction

Treatment of Sexual Dysfunction

Social Values and Birth Control

The Billings method: “natural birth control”

Teenagers, Sex, and Birth Control

Abortion: The Continuing Controversy

Birth Control and Public Policy: The China Example

Birth Control: A Woman’s Right

Motivations for Having Children

Cross-cultural attitudes and practices

Alternative experiences in childbirth

Psychological Aspects of Pregnancy

Relationship with one’s mother

The Postpartum Period: Mother-Infant Bonding

The Postpartum Period: Reactions and Adaptations

10. Women’s lives: tradition and change

Women’s careers: “Dream vs. Drift”

Black Women: The Minority Experience

Lesbianism in History and Culture

“Romantic friendship”: bonding in a female world

Lesbianism and the Medical Model

“Once We Were Sick and Now We Are Well”: The Shift in Perspective

Dimensions of Lesbian Experience

12. Psyche and society: women in conflict

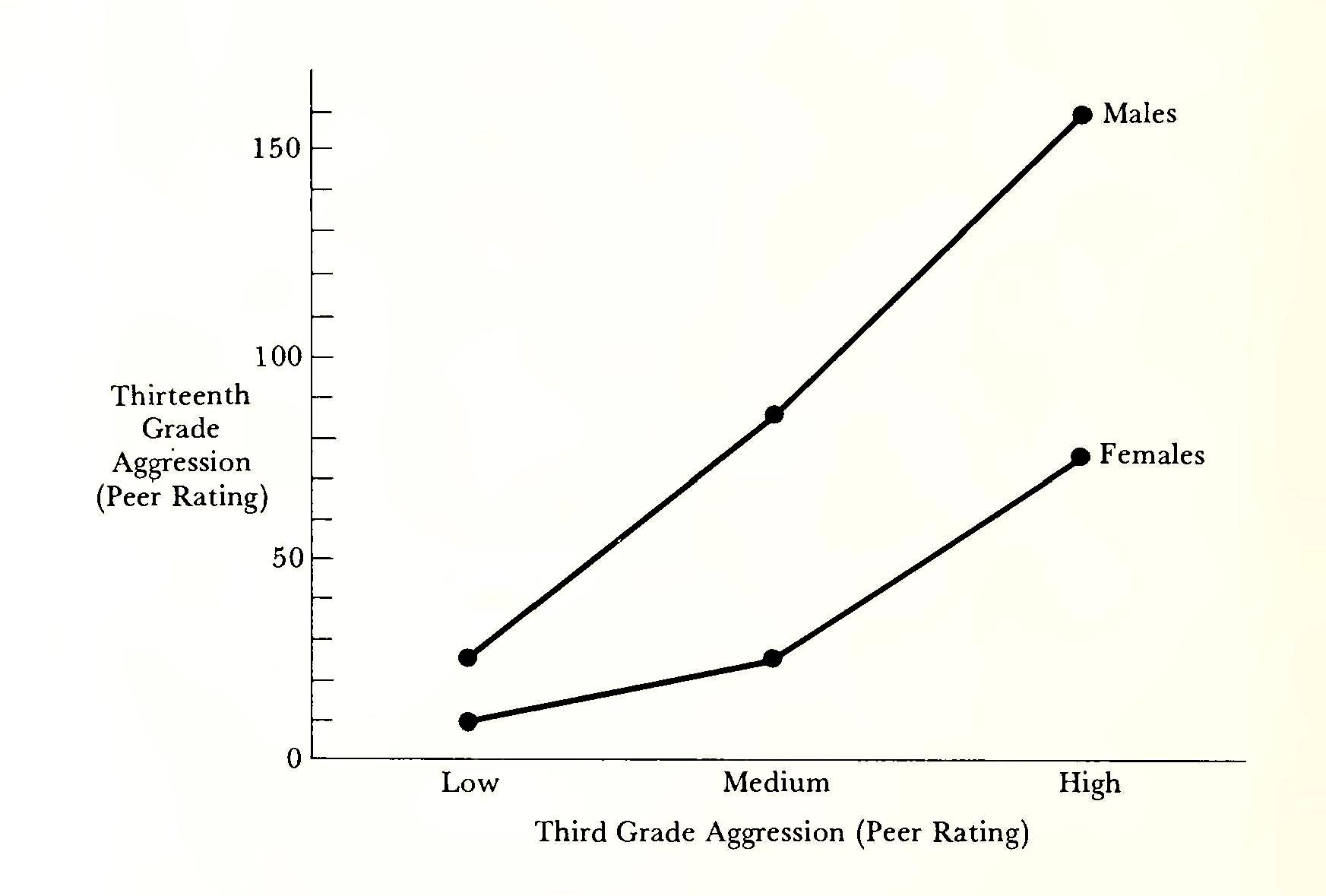

Early Life Adaptation of Girls

Woman as Victims: Violence and Intimidation

Mental and Emotional Disorders of Women

Social Roles and Mental Disorders

The Double Standard for Mental Health

[Front Matter]

Juanita H. Williams is also the editor of

Psychology of Women: Selected Readings

Second Edition

[Title Page]

Psychology

of Women

Behavior

in a biosocial

context

Third Edition

Juanita H. Williams

Professor of Psychology and Women’s Studies

University of South Florida

W • W • NORTON & COMPANY

New York • London

[Copyright]

Copyright © 1987, 1983, 1977, 1974 by Juanita H. Williams

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Williams, Juanita H., 1922-

Psychology of women.

Bibliography: p. 507

Includes index.

1. Women—Psychology. 2. Women—Physiology.

3. Women—Sexual behavior. I. Title.

HQ1206.W72 1987 155.6’33 86–21655

ISBN 0-393-95567-2

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y 10110

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 37 Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3NU

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0

[Dedication]

To my mother,

Anna Bryant Hingst,

with love

and appreciation

Preface

The psychology of women is now established as a discipline, and most colleges and universities have courses focusing on the female experience. Since the first edition of this text in 1977, scholarly work in the area has flourished and today finds the interest and involvement of researchers even stronger. The rapid growth of the field with its many new discoveries makes this third edition necessary. As before, the text is organized on a life cycle perspective that emphasizes critical patterns of events that are likely to be experienced by most women. Much new content has been added. A full chapter (11) on lesbian identity, including the tradition in culture as well as the earlier medical model and the contemporary research-based perspective that has replaced it, informs students of the important issues. A major section, in chapter 10, on the black female experience adds balance to discussion of the psychology of women. In addition, references to research on black girls and women appear in other relevant contexts.

The early chapters that provide the historical setting for the work now include the new controversy over Freud’s seduction theory, and the work of Leta Hollingworth, an early twentieth-century psychologist whose research portended some of today’s issues. New topics include research on why women live longer, a critique of sociobiology, and updated material on gender differences. Carol Gilligan’s work on women’s moral development is reviewed, along with teenage sexuality and birth control, an expanded treatment of abortion, and China’s one-child policy and its effect on women. Also new is the “dream vs. drift” conflict in women’s career decisions, the “having it all” syndrome, and a full new section on pornography and the controversy within feminist circles as women struggle with issues of morality and repression. The incorporation of DSM III permits the latest examination of gender differences in mental disorders, suicide, and eating disorders with analysis of some of the factors that underlie these differences. More positive attitudes coming from research on aging are presented. All chapters have been brought up to date by inclusion of the latest research and theory in the field.

This edition continues to reflect the underlying perspective that the behavior of women occurs in a biosocial context and can only be understood within that context. While women have in common certain biological experiences, they live in drastically different social settings under varying moral codes and conditions of life. No understanding of the psychology of women is possible without taking into account this social context with its permissions and prohibitions. Further, the psychology of women cuts across all the subdisciplines in psychology; it looks at the whole spectrum of behavior as it is shaped from all its sources: the personal, the social, and the biological.

Most of the recent research on the psychology of women has been done by women, an observation reminiscent of John Stuart Mill’s prophetic comment in Subjection of Women over a hundred years ago that no understanding of women would ever be possible until women themselves began to tell what they know. The authenticity of women’s knowledge about themselves and of the kinds of questions that science can ask about them is now recognized by women and men alike. We are assuming more instrumental and authoritative roles in seeking out the answers.

It is now fifteen years since I began teaching courses on the psychology of women. My students continue to inspire me, and I want to thank them again for their interest and enthusiasm. I would also like to thank Marian Johnson at Norton for her careful attention to detail as she edited the new copy. My editor, Don Fusting, has worked with me on all three editions of this book, and his knowledgeable assistance and concern with quality have helped to make each one better than the last.

Once again I appreciate my husband Jim’s support (especially his culinary skills) during my days at the typewriter, and the unfailing interest and curiosity of my daughters, Karen, Anita, Gretchen, and Laura.

J. H. W.

Tampa, 1986

1. Myths, stereotypes, and the psychology of women

It is always difficult to describe a myth; it cannot be grasped ar encompassed; it haunts the human consciousness without ever appearing before it in fixed farm. The myth is so various, so contradictory, that at first its unity is not discerned.... [W]oman is at once Eve and the Virgin Mary. She is an idol, a servant, the source of life, a power of darkness; she is the elemental silence of truth, she is artifice, gossip, and falsehood; she is healing presence and sorceress; she is man’s prey, his downfall, she is everything that he is not and that he longs for, his negation and his raison d’etre.

—Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 1953

Mythic Woman

Over the millennia women have been variously observed and understood, and the derived wisdom recorded in literature, art, and religion for the enlightenment of all. Mostly, understandings of women have taken the form of strongly held beliefs which served to validate and to order experience, or have emanated from such authoritative sources that few would question them. Thus women have been seen as incarnations of both the highest good and the basest evil, of chastity and of lust, of virtue and deceit, and of the sacred and the profane. Men, and women who are co-opted by the prevalent male view, have rarely been able to perceive women simply as human beings with the same range of idiosyncracies as themselves. Rather, they have had to make myths to explain their awesome differences and their strange powers. Occasionally, in time of great stress, when women’s brains, hands, and backs are needed to win a war or tame a frontier, they are seen for a while as simply human— though with certain disabilities, to be sure. But myths do not swirl about the form of the grandmother who matter-of-factly digs a trench for the children to sleep in, nor does a mystique lie about the woman who guides a plow and mule down the rows of some remote farm newly developed from the wilderness.

Aside from such unusual exigencies, however, man has always felt the need to explain and to codify woman, to come to terms with her presence on earth and to accommodate her within his rational system. As he made myths to explain other phenomena of the universe, so he devised explanations of the phenomenon woman which expressed significant truths about her, and images such as old maid or virgin that bring to mind the essential features thought to characterize all persons so called. Such beliefs are ways of knowing; they predate but continue to exist alongside the attempts of science to explain human behavior. The tenacity and continuity of these beliefs in different eras and cultures must mean that they serve potent needs in the human experience.

In addition to their explanatory power, myths also provide man with the hope that he can control the frightening and inexplicable phenomena with which they deal. For example, he sees that a natural event like a prolonged drought threatens his existence. If his mythology includes a responsible god who expresses his displeasure by visiting him with droughts, and who can be placated with gifts, then he can end the drought by making sacrifices to that god. Thus he perceives that he has a measure of control over his own destiny. If the procreative and sexual powers of women awe and frighten him, he can hedge them about with taboos, confine them to special places, or devise elaborate rituals whereby he can deal with the mythic female power. Myths thus introduce a semblance of understanding and order into the apparent chaos of the universe.

Myths about the powers, motives, and special qualities of women have been reflected in the literature and religion of most cultures from earliest times. Although they occur in myriad forms, certain themes have been observed to be universal, and to have continuity with the present. They have been analyzed in detail elsewhere (e.g., Campbell, 1959; de Beauvoir, 1953; Diner, 1973; Figes, 1970; Janeway, 1971). After briefly describing a few of these myths, we shall look at one of them more closely because of its relevance to contemporary ideas about women.

Woman as mother nature

The analogy between woman and the earth as sources of life has always inspired the myths and poems of men and caused them to create their earliest religions and figures of worship. Myths of the Great Mother were part of all the cultures that contributed to the stream of Western civilization. Whether she was called Demeter, Isis, Ishtar, or golden Aphrodite—the goddess of a hundred names—she was the mother and nurturer of both gods and men (Diner, 1973).

A curious reciprocity pervades the mythic concepts of woman and nature. The fecundity of nature, earth bringing forth fruit and grain, sea and river yielding their fishes, all are symbolized by woman. The French author Simone de Beauvoir, tells how an Indian prophet warned his disciples against spading the earth, because it is a sin “to tear the mother of us all in the labors of cultivation” (1953, p. 145). The reciprocity lies in the reversal of these images in the assimilation of nature’s forms to woman. One could find hundreds of examples of comparisons of woman and her various parts to the flora and fauna of nature. Surely one of the most beautiful of these is in the Old Testament Song of Solomon:

Thy belly is like an heap of wheat, set about with lilies ...

This thy stature is like to a palm tree, and thy breasts to clusters of grapes (Solomon 7: 2,7).

The identification of nature with woman and the description of woman in terms of nature suggests an affinity between the two. Man could reside and make his mark, could observe and comment, but it was woman who linked him to earth. “Literally woman is Isis, fecund nature. She is the river and the riverbed, the root and the rose, the earth and the cherry tree, the vine-stock and the grape” (de Beauvoir, 1953, p. 145). She was closer to the mysterious scheme of things, to the heart of the matter, than he was. Did not her very body share with the moon its periodicity, and with the earth its power of generation? Thus she was part of that nature which he could not control, which could destroy him with her capricious whims. To effect a separation of the mortal woman from the identity he feared she had with that power, he had to neutralize her magic by setting up systems which would protect him and would give him some control over the unspeakable contingencies emanating from that identity: “That is why she is never left to Nature, but is surrounded by taboos, purified by rites, placed in charge of priests; man is adjured never to approach her in her primitive nakedness, but through ceremonials and sacraments, which draw her away from the earth” (de Beauvoir, 1953, p. 169).

Woman as enchantress-seductress

Myths of the woman who enchants man with her magic charms and seduces him away from the high paths of his holy mission are as old as communication and as persistent as the sex drive itself. On one level, they are stories, simple or epic, about man rendered powerless, having no choice but to surrender to her who has only the frail weapons of her body and her eyes, and, of course, her special connections with potent forces in those occult dimensions which defy the rational mind. On another level, they represent his projections upon her of his own worst fears about himself, of that dark part of his nature with which he constantly struggles, that part most resistant to being tamed into the service of his higher being. Thus for the statement “Against my better judgment I did something that was very bad,” he substitutes, “She bewitched me, and caused me to do something which I would otherwise never have done.”

Mythic enchantresses, bent upon diverting man from his noble tasks, causing him to abandon reason, and eliciting his essential wickedness, which he had repressed with such pain, are part of our earliest chronicles. The common motif in such accounts is that woman, otherwise powerless, gets what she wants by using devious, cunning means in which her sexual attraction is a strong element to effect the downfall of her prey, man (Figes, 1970). Odysseus, for example, was delayed in his attempt to return home from the Trojan War by the goddess Circe, who, having turned his men into swine, seduced him and kept him on her island for a full year.

Sometimes the fear of being emasculated is brought out in masked form in stories where women cause men to lose their strength, to become like women. Such a woman was lole who feminized the mighty Hercules in an account by Boccaccio. To get even with him for killing her father and carrying her off, she pretended to love him. “With caresses and a certain artful wantonness,” she made him desire her so much that he could deny her nothing. Once he was in this state, she had him take off his lion skin and lay aside his club and quiver of arrows. Defenseless, he submitted to having his beard combed and his body anointed with oils. Adorned with garlands and clad in a purple robe, he came finally to such a pass that he would sit among the women and spin wool. The deceitful lole had more surely destroyed him than if she had used a knife or poison (Figes, 1970).

Other members of the sisterhood who were invested with the myth were the witch and the prostitute. That vision of women which caused millions of them to be tortured and put to death between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries was presented most vividly by Jacob Sprenger, a fifteenth-century Dominican and a witchcraft inquisitor. In the Malleus Maleficarum—“hammer of witches”—he set forth the doctrine that large numbers of women were in unholy alliance with Satan, and were a horrible threat to man, particularly to his genitals. The worst vice of these women was their insatiable lust, which led them to copulate with the Devil and become his intermediary, working his mischief on the body of man. This idea persisted in less virulent form in later ministerial invocations against the prostitute. She aroused men like Henry Ward Beecher, the famed nineteenth-century American preacher, to passionate rhetoric: “What horrid wizard hath put the world under a spell and charm, that words from the lips of a STRANGE WOMAN shall ring upon the ears like tones of music.... [F]rom the lips of the harlot words drop as honey and flow smoother than oil; her speech is fair, her laugh is merry as music.... [T]rust not thyself near the artful woman, armed in her beauty, her cunning raiment, her dimpled smiles, her sighs of sorrow, her look of love” (Walters, 1974, p. 70).

Woman as necessary evil

The perception of woman as necessary evil, as inferior, insignificant nonperson who is barely tolerated for the services she performs, is true misogyny. Necessary to perform the functions of sex object and child bearer, she is otherwise unimportant, rightfully excluded from the company and affairs of men. While the fortunes of women have varied in different societies at different times, it is a universal observation that men have held women to be lesser persons than themselves and have ascribed to them an inferior status (Bullough, 1973). A very early example is Hesiod’s eighth century b.c. account of Pandora, the Greeks’ version of the first woman. Pandora came to the first man as a gift from the gods, who had given her a box never to be opened. All too mortal, she could not contain her curiosity and loosed all the evils and diseases which have plagued humans ever since. Hesiod pointed out that it was from her that all women descended, that troublesome tribe who brought man nothing but misery whether he married them or not. A wife was a constant financial drain who could not be trusted in any case. Without her, however, he would have no heirs and no one to nurse him in his old age.

During most of the history of Western civilization, women have been regarded basically as property, with no rights of their own. A strong tenet of Puritan belief, for example, was the requirement that women be kept in a subordinate position. The Puritan poet John Milton insisted on the inferiority of women and the need for men to guard their authority over them to keep them from foolish action. He expressed the not uncommon theme of woman as a kind of intrusive nuisance in man’s world in Paradise Lost, when he has Adam plaintively ask, after the Transgression, why God created “this novellie on earth, this fair defect,” instead of filling the world with men, or finding some other wax’ to generate mankind (Rogers, 1966). 1 his mythic perception of woman as necessary evil has persisted through the ages, and has survived the evolution of ideas and intellectual changes. As one of the earliest and most influential views of women, it has dominated not only religious teaching but philosophical thought as well. Schopenhauer, the nineteenth-century German philosopher, is only one example of a cohort of the period whose ideas about women ranged from patronizing to loathing. His essay On Women starts out with an innocuous tribute to woman’s contribution to man’s infancy, maturity, and old age, then gets on with his theme. Women are fitted to nurse and teach children because thev are themselves childish and frivolous—an intermediate stage between the child and the full-crown man. Nature lavishes beautv on the young female so that she can capture a man, who, bereft of reason, takes on the burden of her care forever. The fundamental fault of the female character is that she has no sense of justice, being defective in the powers of reasoning and deliberation. In compensation. Nature has caused her to excel in dissimulation, faithlessness, treachery, lying, ingratitude, and so on. Only the man whose sexual impulse has beclouded his reason would call her the fair sex, for she is in fact undersized, narrow-shouldered, broad-hipped, and short-legged. She looks upon everything as a means for conquering man. Thus, she has no genuine interest in any art. and no genius whatsoever.

We shall see later how such vindictiveness encountered a stifling effect with the ascendancy of another myth about women. Even so. the underlying hostility could continue to be vented toward such deviants as old maids—women whom no man had found desirable enough to marry—and feminists, who insisted upon violating the boundaries of woman’s place by demanding a role in the institutions which man had created. Ebe basic ideas of woman’s inferiority and unfitness to be man’s equal continue to be thematically important as determinants of attitudes toward her.

Woman as mystery

The seeming perversity of woman’s behavior, the wonderment she excited with her strange powers, the ways she was different from man gave rise to another myth, which was that her mental processes, her behavior, and the whole of what she was, made up a feminine essence which was beyond the power of philosopher, scientist, or any ordinary baffled male to understand, just as there were other natural phenomena which did not yield to reason or empirical science, so there was woman, with her unpredictable ways and her enigmatic face. This myth, in a way, is a supplement to all the others. Failing any other explanation, she can be viewed as a different order of being, to whom the laws and rules by which behavior and thought are normally understood do not apply.

Simone de Beauvoir in an analysis of the myth of feminine “mystery” pointed out its advantages. First, it permits an explanation which will fit all manner of events. Caprices, moodiness, strange excursions—-whatever about her man does not understand, he can attribute to that quality of hers he is sure of, her essential mysteriousness. Instead of admitting ignorance, he can relegate her to that category of events which are simply inexplicable. Second, he can protect himself from disturbing insights. If she changes in her affections, if she talks in riddles, the mystery explains it all. Last, and perhaps most important, it permits man to remain alone as the One who works, judges, and defines reality. She is the Other, and since he cannot understand her, he is exempt from the effort of building an authentic relationship with her. If he cannot understand her, she cannot be understood, and authenticity cannot occur in the absence of understanding. Thus even when he is with her he stands alone, in charge, an alternative to the admission and sharing of their common humanity (de Beauvoir, 1953).

Upon what basis could such a myth be founded and perpetuated? The mystery is in the inability of man and woman to communicate across the distance that separates her world from his. As de Beauvoir observed, humans are defined by their acts. When a woman is kept by a man, she is a passive recipient of the advantages he bestows upon her as long as he cares about her. But this role is not a vocation and does not bestow identity upon the woman. Her dependency causes her to dissemble, as all subordinates learn to dissemble with their masters, concealing their real thoughts and feelings under an enigmatic exterior. “And moreover, woman is taught from adolescence to lie to men, to scheme, to be wily. In speaking to them she wears an artificial expression on her face; she is cautious, hypocritical, play-acting” (de Beauvoir, 1953, p. 259).

By defining her as mysterious Other, man spares himself the necessity of analyzing her behavior and understanding it as a consequence of her position vis-à-vis him. To do that would require acknowledgement of her oppression, and a possible shift in their power relationship. The price would be very high.

Behavior theorists of modern times have had much to say about women, some of it helpful, some of it not, in furthering understanding. Freud was less sure than some of his followers that either he or the theories he developed had revealed the mystery. His biographer, Ernest Jones (1955), said that Freud found the psychology of women “more enigmatic” than that of men, and reported him as having asked a female colleague, “The great question that has never been answered and which 1 have not yet been able to answer, despite my thirty years of research into the feminine soul, is ‘What does a woman want?’ ” (p. 421). And in 1933, in his last paper on female psychology, he spoke of femininity as a riddle—to men but not to women, since they were considered the problem. If one wanted to know more about women, he said, one could ask of one’s own experiences, or turn to the poets, or wait for science to give the answers (Freud, 1965).

The influences and remnants of these mythic explanations for woman, as Mother Nature, as spellbinder, as necessary evil, and as mystery, are not difficult to find in the popular culture of today. There is another, however, which has probably had more influence on the lives of women in our society because it is perfectly in keeping with the ideal model for womanhood which has persisted until recent times. It is the myth of female goodness, of woman as the embodiment of virtue. This myth told women how they ought to be and described the rewards. From its beginning with the virtuous wife to today’s stereotypes of the feminine woman, this myth more than any of the others has defined woman’s place and her behavior in it.

From Myth to Stereotype: The Virtuous Woman

The model of the virtuous woman has occupied writers, priests, and moralists since earliest times. Throughout history there has been remarkable agreement on her characteristics. She is a faithful, loyal, and submissive wife; a dedicated, loving mother; a competent, diligent housewife; and an unquestioning supporter of the moral and religious values of her society. Although emphasis on the importance of each of these qualities has varied in different periods, the basic elements are nearly always discernible. Together they have defined her place. More than the definition of her physical setting, it has included the constellation of personal characteristics and permissible behaviors which distinguish her from the male and describe her status relative to his. As long as she observed her place and behaved in accordance with its prescriptions, no fault was found in her. In fact, during some periods she was so elevated that men were figuratively if not literally on their knees before her, overcome by the moral qualities of her being, so different from their own.

The Book of Proverbs contains an Old Testament description of what constituted goodness in women:

She riseth also while it is yet night, and giveth meat to her household, and a portion to her maidens.

She considereth a held, and buyeth it; with the fruit of her hands she planteth a vineyard ...

She layeth her hands to the spindle, and her hands hold the distaff ...

She stretcheth out her hand to the poor; yea, she reacheth forth her hands to the needy ...

She looketh well to the ways of her household, and eateth not the bread of idleness.

Her children rise up, and call her blessed; her husband also, and he praiseth her ... (Proverbs 31: 15–28).

This description of industry and household productivity was supplemented by the statements of early Christian writers on the proper role of women. Women were constantly admonished to obey their husbands. “Wives, submit yourselves unto your own husbands, as it is fit in the Lord” (Colossians 3: 18). St. Augustine, the fourthcentury Christian scholar, presented a model of motherhood in a reverential description of his mother, Monica. He praised her for putting up with his father, an unbeliever and adulterer, for praying for him, and above all for never chastising him or showing any temper. Monica had even instructed other women who complained about their husbands that they were bound by the marriage contract to serve, to remember their condition, and not to defy their masters (Figes, 1970).

The ultimate prototype of the model wife, however, was the patient Griselda, whose story was told by the celibate clerk in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales of the fourteenth century. Griselda was a serf, whose noble husband had married her on the condition that she would be completely obedient to his every wish. To test her he had her two children taken away, saying that they must be put to death. She acquiesced graciously. He later told her that she must return to her father’s hovel, as he had decided to take a younger wife. She agreed to her unworthiness and cheerfully left, thus finally convincing him that she was indeed a good wife. Thereupon he returned her children and brought her back to be his wife. Griselda thanked him copiously, and said that she would die happy knowing that she had found favor in his sight.

During the Middle Ages, there arose the convention of romantic love, a passionate, despairing devotion directed toward an impeccable and unattainable (in theory) lady. Chivalry, the code prescribing that women should be given precedence by a gentle, courteous male, arose from this convention (Bullough, 1973). The man in love, usually a knight, minstrel, or noble, was in a state of total adoration, “in thrall,” indeed. Whether he was rewarded or not, the fact that he was in love had great positive value for him, making him more skillful and valiant at his pursuits, usually war or practice for it. The woman, though she herself was a passive recipient of his ardor, had ennobling qualities: she inspired in him courage, skill, and honor. While very few women benefited from this novel adulation, it marked the beginning of the tradition of courtly love, of the feminine mystique, and of the vision of woman on a pedestal which has been one line of approved wisdom ever since.

Rarely have women been idealized and worshiped with such unrelenting fervor as in the American South during the nineteenth century. This attitude spread to other parts of the country as well and was responsible with some modification for the prevalent view of woman during the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century.[1] Southern womanhood became a symbol for the Southern male, who imbued her with qualities of purity and goodness which had to be protected and defended against any hint of defilement or threat to her honor. The ideal woman was described in The Mind of the South as a combination of “lily-pure maid” and “hunting goddess”: “And she was the pitiful Mother of God. Merely to mention her was to send strong men into tears—or shouts. There was hardly a sermon that did not begin or end with tributes in her honor, hardly a brave speech that did not open and close with the clashing of shields and the flourishing of swords for her glory” (Cash, 1960, p. 89).

This romanticization of women was an important social motif in mid-nineteenth-century America, epitomized by the “cult of true womanhood” (Welter, 1973). The true woman, a Victorian adaptation of earlier models of the virtuous woman with strong Puritan and moralistic overtones, had four virtues: piety, purity, submissiveness, and domesticity. So identified, she was secure on her pedestal, and reverential paeans were sung in her honor. Her religious piety made her the moral arbiter of the home and the society; by her doing, souls would be saved; erring men, always more subject to temptation than she, would repent; and fallen women be brought to salvation. Purity meant chastity until the wedding night, an event to which she brought her greatest gift, her virginity. Girls were warned over and over again about the perils of sitting too close to males, of dancing, of inflaming the senses with novels, of listening to “the siren voices of vicious pleasure.” For “the sin against chastity was a graver, deeper sin, than any other; ... the white robe of innocence once soiled, could never again be restored to its former purity” (Brockett, 1869, pp. 213–17). In the sexual relationship, it was woman’s responsibility to set the pace and to keep a healthful balance. Physicians taught that women had little or no sex drive and responded to their husbands only to keep them from going to prostitutes. Woman’s lack of desire was nature’s way of taming man’s animal lusts, thus avoiding the drain on his vitality that too frequent or prolonged intercourse would have (Haller, 1974). This view of female sexuality contrasts remarkably with that of its counterpart, the seductress, who was invested with such insatiable appetite that man must be ever on his guard against her.

The third virtue, submissiveness, was the God-imposed role of good women, who deferred to their husbands in all things. The woman who questioned this, or took independent action, was a threat to the sacred order of the universe. It was mostly on this point that the antifeminist argument rested. The suffrage movement, for example, was seen as an assault against Christianity, the home, and the institutions of marriage and the family. The physician James Weir, Jr., in 1895, “proved” that the woman who advocated equality of the sexes had “either given evidence of masculo-feminity (viraginity), or had shown conclusively that she was a victim of psychosexual aberrancy” (Haller, 1974, p. 77). The view that submissiveness was natural and therefore good for women was supported in countless books and treatises which documented sex differences in brain and physique to support the point that woman was delicate, frail, and weak, and that too much intellectual or otherwise assertive activity would damage her health irreversibly (Bullough, 1973). It was common for the medical men of the time to assert that overexercise of the female brain in study would cause mania, sterility, and deterioration of health.

Finally, the true woman was revered for her domesticity. The care of the home and its occupants was her highest calling. To her family she was a comforter and a ministering angel. Gentle, patient, and merciful, she was a perfect nurse, teacher, and inculcator of values. She formed the mind of the infant, the holiest of tasks, and made it possible for the successful man to give her the ultimate accolade, “All that I am I owe to my sainted mother.”

The myth of female goodness, building as it did upon the belief in woman’s special nature and her moral character, was in fact for women a two-edged sword. On the one hand, it set her apart from the world in a small sphere of her own defined by rigid conventions and artificial pretensions. As long as she observed her place and her duties, she was the object of esteem and adoration, was “better,” in fact, than the male whose life was too rough and competitive to permit such refinement of taste and decorum. But this elevated status had very little material reward or prestige, other than that ascribed to her by her husband’s position. She had no legal or political power, very little personal freedom, and no way to achieve economic independence. But secure in her place, and venerated as she was, what need had she of these? Thus was she rewarded for her meekness and compliance, and told that she was too good and too delicate to participate in the affairs of men.[2] Women who refused to conform to this model, such as the feminists and other radicals, were castigated in pulpit and press as anarchists and perverts, as unnatural and morally defective.

Another major problem with the myth was that it conflicted with reality. Most Americans of the time still lived on farms, and women did not have the leisure or the means to cultivate the manners and life style of the proper female, as prescribed by the cult of true womanhood (Bullough, 1973). But while probably only a small minority of American women ever lived the myth in all its connotations, it was still the official style of being female and was promoted in the printed media and from the pulpit until recent times. In fact, the same rhetoric has recently reverberated through the land, in support of the arguments of those opposed to the Equal Rights Amendment. Opponents contend that women are a special class of being, and need special protection; not man’s equal, they are his superior. Those who demanded equality and liberation from the old shackles of role and place were rejecting their femininity. They were frustrated harridans or lesbians or both. The more things changed, it seemed, the more they remained the same.

The Psychology of Women: Philosophical Origins

The mythic models of women described above were constructed and maintained mostly in literature, religion, and the popular culture. While they have survived historically in the attitudes and beliefs of people of all statuses and walks of life, it is interesting in particular to note their presence in the thinking of many of the great philosophers of the Western intellectual tradition.

The reason for this is that psychology as a scientific discipline has its roots in philosophy, as well as in the natural sciences. For example, Aristotle, the great fourth-century b.c. Greek philosopher whose ideas about women we shall look at later, made contributions to both these branches of knowledge that are evident today in psychological assumptions and methodologies. These include the construction of a system of knowledge whereby the behavior of living organisms may be studied, both empirically and rationally; the assumption of the intimate relationship between the mind (“soul”) and the body; and the practice of recording and interpreting human behavior and experience in concrete terms. Psychology emerged as a separate discipline in the late nineteenth century as it adapted scientific methodology to the study of behavior and began to move closer to the natural sciences with their emphasis on measurement, experimentation, and control. The link with philosophy has remained strong, however, and manifests itself in modern times in the work of such psychologist-philosophers as, for example, William James (1890), John Dewey (1930), and Rollo May (1953).

For these reasons it is enlightening to look at the ways in which women have been conceptualized by our philosophical mentors. And the inescapable observation is that most of the best-known historical philosophers had a strong antiwoman bias that ranged from condescension to virulent misogyny:

Most famous philosophers made sexist remarks or formulated misogynist theories in their lesser-known writings. Now feminists have realized that these are not just incidental comments reflecting the assumptions of the time but integral parts of these philosophers’ larger theories which cannot be quietly expunged or passed over with a sigh (English, 1978, p. 825).

Philosophy is concerned with inquiry into principles of reality, such as human nature, human values, and so on. Analysis of many philosophers’ theories of “human” nature reveals, however, that “human” means “man” and that women are explicitly excluded on the grounds that they lack some essential human capacity possessed by males only, which relegates them, along with children and slaves, to an inferior category. Aristotle was very clear in his view that woman was to man as the slave to the master—that she was an unfinished man, being on a lower level of development. The male, he thought, was fitted to rule by reason of his natural superiority. Women were weak of will and incapable of independence; therefore, their best condition was a quiet home life.. the courage and justice of a man and of a woman are not, as Socrates maintained, the same; the courage of a man is shown in commanding, of a woman in obeying.... [A]s the poet says of women, Silence is a woman’s glory, but this is not equally the glory of man” (Bishop and Weinzweig, 1979, p. 46).

One of the greatest proponents of individual freedom was the French Enlightenment figure Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712—78). Believing that the maintenance of political liberties depended upon an educated populace, Rousseau set forth his ideas on education in Emile, a treatise describing the difference between males and females, their places in society, and how they should be trained for them. The emphasis for the boy is on freedom of intellectual expression, so that his mind may develop to its full power, fitting him to take his place in a democratic society. The girl, however, is to be prepared for a future when she will be totally dependent upon a man, “at the mercy of man’s judgment”:

A woman’s education must therefore be planned in relation to man. To be pleasing in his sight, to win his respect and love, to train him in childhood, to counsel and console, to make his life pleasant and happy, these are the duties of woman for all time, and this is what she should be taught while she is young.... What is most wanted in a woman is gentleness; formed to obey a creature so imperfect as man ... she should early learn to submit to injustice and to suffer the wrongs inflicted on her by her husband without complaint ... (Rousseau, 1979, pp. 365–67).

Rousseau also pronounced that girls should be trained to be docile, that it is more important to show a woman what to believe than to explain to her the reasons for belief: “Unable to judge for themselves, they should accept the judgment of father and husband as that of the church” (p. 369). Though hailed for two hundred years as a champion of human liberty, Rousseau, too, saw “human” as meaning “man.” Woman was still the Other.

A final example of the tradition of misogyny in historical philosophy is Friedrich Nietzsche, for his time the most influential of the nineteenth-century German philosophers. Nietzsche grew to manhood during the flowering of feminism in Europe and the United States. He thought that the ideas of feminism, with its philosophy of sexual equality, were ridiculous, part of the “litter of democracy,” as were any other notions that people had any inherent right to equal treatment in the society. Equality between man and woman is impossible, he said, as well as dangerous. A woman will be content with subordination if the man is truly a man. Anyway, her perfection and happiness lie in motherhood. “Man is for woman a means; the end is always the child. But what is woman for man? ... A dangerous toy.... Man shall be educated for war and woman for the recreation of the warrior; everything else is folly” (Nietzsche, 1964, p. 75).

Aristotle, Rousseau, and Nietzsche are not selected for comment here because they are special in their thinking about women; rather, in the long history of philosophy until very recent times these giants of Western philosophy are typical in their derogation of women and in their assumption, rarely questioned, that women are an inferior order of being for whom equal status with men is unthinkable. It was not until the 1970s that feminist analyses of philosophy began to reveal the systematic flaw of misogyny in the science that seeks truth through reason and logic (English, 1978; Moulton, 1976; Pierce, 1975).

A minor theme: the argument for equality

Though the inequality of women with men was a basic assumption in almost all the great philosophical systems from the Greeks to modern times, we can still discern among them the thin thread of another argument: that, even allowing for some basic differences between the sexes, women and men should be judged as individuals and should have access to positions of equality in the society and in the law, and that women should not be dominated by and subjugated to men.

The earliest of these, and in some ways the most remarkable, was Plato, a fourth-century Greek philosopher and teacher of Aristotle. In the Republic, Plato’s construction of a utopian society, women were included among the ruling elite, the guardians, though within that class men as a whole had higher status. Private property was eliminated, as was monogamous marriage and the private family. Plato argued that men and women were similar in all respects except physical strength and the bearing and begetting of children. Therefore female and male guardians were to be educated alike in preparation for their assignments in the society. Women would strip for exercise like the men did, and they would not bear children until the age of twenty, in contrast to the child-mothers of his own city, Athens. Considering the time in which he lived, perhaps one of Plato’s most remarkable contributions was his recognition of individual differences among women, as well as among men: “... there is no special faculty of administration in a State which a woman has because she is a woman, or which a man has by virtue of his sex, but the gifts of nature are alike diffused in both ...” (Bishop and Weinzweig, 1979, p. 44).[3]

Male feminists in the nineteenth century were rare, but one such was John Stuart Mill, English philosopher and political economist. In On The Subjection of Women (1869), he stated flatly that the legal subordination of women to men was wrong and should be replaced by a principle of perfect equality, “admitting no power or privilege on the one side, nor disability on the other....” Mill pointed out that the subjection of women is different from that of other oppressed classes, in that men, the masters of women, want not just service but sentiment, too. In other words, he said, men want a willing servant, not one who is inspired by fear. Therefore, women have had to be trained from the cradle to live for others in total self-abnegation. Since any pleasure or privilege that women want can in general only be obtained through men, the object of being attractive to them becomes the guiding star of women’s education and formation of character. Men then use this by representing to women that what they want, that what is sexually attractive to them, is meekness and submissiveness. Thus women take on the yoke of servility and become what men want them to be because they have no other choice.

But as with Plato, Mill had his stopping point. He believed in equal educational opportunities for women and in women’s right to seek careers. But, he wrote, marriage was itself a career, and because of certain psychological differences between the sexes, women should not try to combine a career with motherhood (Annas, 1977).

The Psychology of Women: Science and Social Values

Philosophers, whether misogynistic or egalitarian, probably had little effect upon the realities of women’s lives in the late nineteenth century. Attitudes expressed by opinion leaders such as ministers and educators partook of neither the extreme negative bias of, for example, Nietzsche, nor the egalitarian recommendations of Mill. Rather, the prescription of domesticity and the sentimental idealization of woman and her role were descriptive of the socially valued model of woman’s behavior in both Europe and the United States at the time. At the same time there coexisted the notion of woman as a different order of being. A major feature of her difference was her relative lack of characteristics valued in males, such as originality, creativity, emotional control, and educability—in short, a generalized notion of her inferiority. These two ideas were perfectly compatible with each other, the latter being a rationalization for excluding women from public life and confining them to that sphere in which they could exercise their special qualities of tenderness, nurturance, and devotion to the well-being of others. By virtue of her exercise of these qualities, woman and her place were imbued with a romantic aura that was held to be ample compensation for her inability to do the kinds of things that men did, such as acquiring an education and becoming economically productive. This view of how woman was and how she ought to be was the mode when the young science of psychology began to examine her around the turn of the century.

Psychology is the field of study whose goal is to describe, understand, predict, and control the behavior of humans and other animals. During its early development, in the latter years of the nineteenth-century, little attention appears to have been given to the study of women separate from the study of the adult human. Around 1900, however, there developed in the United States a school of psychology known as functionalism, whose defining feature was its incorporation of evolutionary theory into the subject matter of psychology, emphasizing the concept of adaptation and adjustment to a particular environment. The idea that humans had evolved from lower animals and thus were biologically related to the rest of the animal kingdom influenced the functionalists to apply the concept to behavior as well. Human behavior was seen as the end result of a long process of adaptation and adjustment to the environment, and most important for our subject, it included certain innate components which were biologically based and which humans shared with other animals—such as the maternal instinct. The effect of this trend of thinking gave rise to studies of the biological bases of human behavior, and to studies of individual differences, including the study of gender differences. The Significance of the marriage of evolutionary theory and psychology for the beginning of the scientific study of female behavior was demonstrated in a paper which describes the bridge between myth and science, and shows how, in this case, they served each other (Shields, 1975).

The observable sex differences in brain size, in intellectual and cultural achievement, and in nurturing behavior had long been ascribed to the fact, put forth and advocated by the great authorities of religion and philosophy alike, of the inferiority of the female. For the religious authorities she was a lesser being because of her derivative creation and her fateful behavior in the Garden. The European philosophers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, however, attributed her inadequacies to her lack of male virtues, to the fact, ultimately, that she was not male. In either case her inferiority necessitated her subordination to the male and her relegation to the only role that was natural and suitable for her, owing to her biological endowment.

For scientists, such explanations would not suffice, and thus began the search for more sophisticated ways for understanding what was patently observable: the behavioral differences between males and females. The search began, however, with the same old assumptions that woman’s lesser cultural contributions to the society and her behavior in the domestic role were part of the natural order of things. The problem was to find the underlying mechanism to account for these at a level that would satisfy the scientific intellect. To this end did attention turn to topics which had an early relevance to the psychology of women. Three of these were differences in male and female brains, the variability hypothesis, and the maternal instinct. The history of scientific attention to each of these topics shows how their importance as issues lay in the extent to which they explained contemporary beliefs about women and about sex differences (Shields, 1975).

The notion that sex differences in brain size and in development of different areas of the brain explained sex differences in achievement and personality traits was held by neurologists as well as nonscientists until well into the twentieth century. The investigation of its validity became irresistible once tests for measuring intelligence and other abilities became available. Although interest in the issue diminished rather early owing to lack of corroboration within the testing movement, it reappeared, in a paper associating brain size with the maturing of “other powers” (Porteus & Babcock, 1926). Males, because of their larger brains, would have more of these powers and would thus be more competent and achieving. Such proposals, coming from psychologists, fit readily into the social value system and so could be assimilated under the aegis of science.

The variability hypothesis proposed that males vary more from the norm than females do on certain characteristics, including intelligence. This means that a greater percentage of males compared to females would be found at the upper and lower extremes on measures of those characteristics. Thus, for intelligence, the hypothesis is that males would be more likely to manifest both genius and mental deficiency. This explanation would account for the greater achievement and productivity of men, as well as for the observed greater number of men in institutions for the mentally deficient. The popularity of this hypothesis “did not stem from intellectual commitment to the scientific validity of the proposal as much as it did from personal commitment to the social desirability of its acceptance” (Shields, 1975, p. 744). The corollaries of the hypothesis obviously had strong social implications for women. If genius was a peculiarly male trait, then one would not expect so much from women; therefore, their education should fit them not for the wider world, but for their place in it, and their roles as wives and mothers. The variability hypothesis as one explanation for gender differences has continued to be a topic of interest for psychology. Recent evaluations of the relevant research conclude that the available data are contradictory, and are not in general supportive of the hypothesis (Maccoby and Jacklin, 1974; Shields, 1974).

The concept of maternal instinct, which maintains that women’s nurturing behavior is an innate, biological determinant shared with other female animals, was readily incorporated into the early doctrines of psychology. The idea of maternal instinct in human females was quite compatible with evolutionary theory. Along with it went the broader concept that woman’s reproductive physiology was intimately and causally related to her behavior in general. That most of her energy, both mental and physical, was consumed by the functions of reproduction accounted for the lack of development of other qualities. I he parental instinct of the male was seen as a more abstract, protective attitude toward weak and dependent ones, such as wives and children, whereas it was the nature of the female to respond with specific nurturant behavior to the helpless infant.

The notion of the innateness of maternal behavior was not disputed until the advent of the behaviorist school of psychology in the mid-1920s. The behaviorists successfully challenged the entire concept of instinct in humans, holding that most human behavior was learned. Consequently, interest in the maternal instinct appears now in experimental studies of nurturant behavior in other species. Even so, the idea that women’s greatest fulfillment is motherhood has been remarkably persistent: “as much as women want to be good scientists or engineers, they want first and foremost to be womanly companions of men and to be mothers” (Bettelheim, 1965, p. 15).

Explanations of social and behavioral sex differences which rely on differences in brain size, variability, and the maternal instinct seem quaintly archaic to us now, but it is very easy to see how neatly these concepts met the need of behavioral scientists of a few decades ago to understand the social phenomena of their world. In attempting to move from myth to science, they created new myths which would both explain and justify the social order. “That science played handmaiden to social values cannot be denied” (Shields, 1975, p. 753). Though these issues are now of historical interest only, the search for biological bases of behavior and gender differences continues.

Explanations for the phenomena of female behavior have moved from their mythic beginnings to persistent stereotypes whose acceptance by scientists and lay persons alike impeded deeper understanding, probably being sufficiently satisfying at the time to make further inquiry seem unnecessary. As the influence of functionalism declined from the thirties onward, so too did interest in research on female behavior. Except for continued interest in the topic of gender differences, there was little attention to the scientific study of women by psychologists until the late sixties. Since then research has begun to move beyond the mythic and stereotypic ways of viewing woman toward a sounder understanding of the real determinants of her behavior.

On Understanding Women: Contributing Sources

Knowledge about women is less imperfect and superficial today than it was when the British philosopher John Stuart Mill exposed prevailing beliefs of his time about the nature of women for what they were: inventions of a patriarchal society whose purpose was to justify and to maintain the social order. Women today are becoming conscious of themselves, of their commonalities, and of the influences, only now perceived and articulated by large numbers of them, which have affected their lives and their destinies. Women have begun to reflect upon themselves and their lives, to formulate their own questions, to study women, and to tell what they know. Perhaps in the past, as Mill suggested, women had a stake in preserving the mystique which lay about their behavior, since their status relative to men was one of subordination. It was wiser not to reveal oneself, one’s thoughts and feelings, because such revelation entailed too great a risk to one’s already too-vulnerable position. As woman becomes free standing and attains equal status with man, she can afford to let herself be known. Where are we now in the process of understanding women? Some old problems which impeded understanding have been identified, and some still unresolved issues have been raised.

Human behavior emerges from the neonatal repertoire and becomes organized in a social context. It becomes purposeful and responsive and theoretically predictable. Contrary to popular belief, the behavior of women is not more capricious, cryptic, or occult than the behavior of men. It has, however, been less well understood in any scientific sense because theoreticians and researchers most of whom were men shared certain basic assumptions about women and men which diverted their attention from the critical questions whose answers could have dispelled the mysteries about female behavior.

Not infrequently, when women have been included in research samples, their performance has turned up inexplicable sex differences which constituted an anomaly to the existing theory. Their behavior did not fit with the model which was supposed to predict the behavior under investigation. Confronted with this embarrassment, what alternatives has the investigator? First, he can regard the anomaly as uninteresting and simply ignore it by studying males only. An example of this is the research on the achievement motive, an area which has drawn considerable attention during the past two decades. At the height of this attention, a major review of personality research contained the following:

In general, studies of achievement motivation have been confined to samples of males. The few available reports of experiments on women have been ambiguous and inconclusive (London and Rosenhan, 1964, p. 461).

It was not until 1970, that the anomaly of women’s achievement behavior began to be understood (Horner, 1970).

A second possibility is to interpret the female anomaly in such a way that it can be fitted into the theory, or even to extrapolate from or to add onto the theory to make it cover the incidental other.

The female case has often been neglected, and too frequently forced into inappropriate male categories.... [Psychologists have often set up dimensions where the female can only come out as “not male” (weak instead of strong, small instead of large, etc.). And the persistent tendency to read “different” as “deficient” leads to less than rational controversy in this field, especially where it touches on delicate social balances and cherished mythologies (May, 1966, p. 576).

As we will see, the best (and best-known) example in personality theory, which is basically a masculine model, is that of Sigmund Freud. His basic model of psychosexual development based on the male was adapted to fit the female, and the adaptation utilized primarily the fact of her difference from the male.

The problem with these ways of trying to explain women is that they have a point of view which imposes an inherent necessity on them to explain women in terms of men. Hence, they try to fit woman’s behavior into a conceptual scheme devised from a male stance to explain male motivations and behavior.

The fact that humans occur in two basic biological types, male and female, has made further comparisons between them irresistible. The very large literature on sex differences attests to the fascination that such inquiry has for scientists as well as for lay persons (e.g., Maccoby and Jacklin, 1974). But the practice of studying woman by looking at the ways in which she is different from man has the clear potential for reinforcing the use of a masculine model as a standard for humans, or even for raising a new standard, now built on female criteria. Neither of these is more acceptable than the other. Further, an emphasis on sex differences implies a categorical distinction, a dichotomy of opposites, which is not justified. Woman is not the opposite of man, each being more like the other than either is like their same sex in any other species. The intrasex differences in most psychologically relevant variables are so large, and overlap between the sexes is so extensive, that identification by sexual category offers little in the way of prediction of behavior.

Instead of ignoring female behavior, trying to explain it in terms of models developed from studying males, or emphasizing differences between groups of females and males, one can, alternatively, undertake the serious study of women as women, using interdisciplinary conceptual tools and methods that will illuminate the dark spaces in our knowledge about them.

Understanding women requires that attention be paid to a number of determinants which interact to influence the behavior of any particular woman or narrowly defined groups of women. These include biology, socialization within a social order, life chances, and personality. As determinants of behavior, they range from the widely shared (biology) to the unique (personality).

Biology

In the popular wisdom the psychology of women, their motivations, personality, and behavior, has been closely tied to the events of their bodies. Theorists have attempted to explain women in terms of their bodies, and researchers have looked for the demonstrable effects of women’s bodies on their behavior. All of these approaches suggest a basic assumption that for women the relationship between biology and behavior is a uniquely strong and intimate one. While this assumption may be valid, it has yet to be demonstrated as a universal principle by the conventional methods of science.

It is plain that the biological distinctions between the sexes in infancy do not mediate the development of a feminine or masculine gender; rather, with certain rare exceptions (Stoller, 1972) the sense of oneself as female or male grows from innumerable noncontradictory communications from others, which are normally contingent upon the appearance of the external genitalia (Money, 1972). But that sense is less a function of biological sex than it is of parental reaction; thus the crucial factor is psychological, not biological (Stoller, 1974).

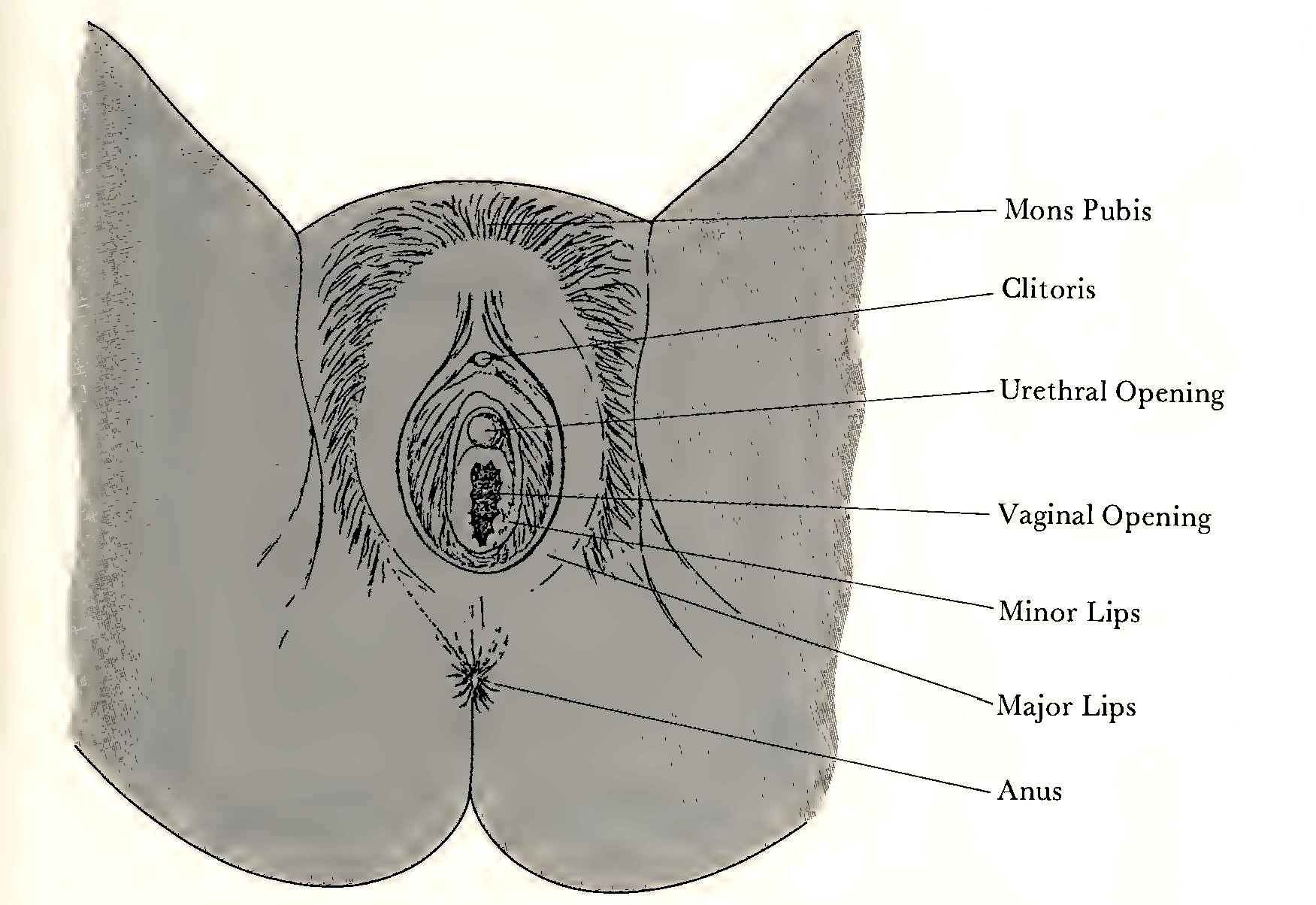

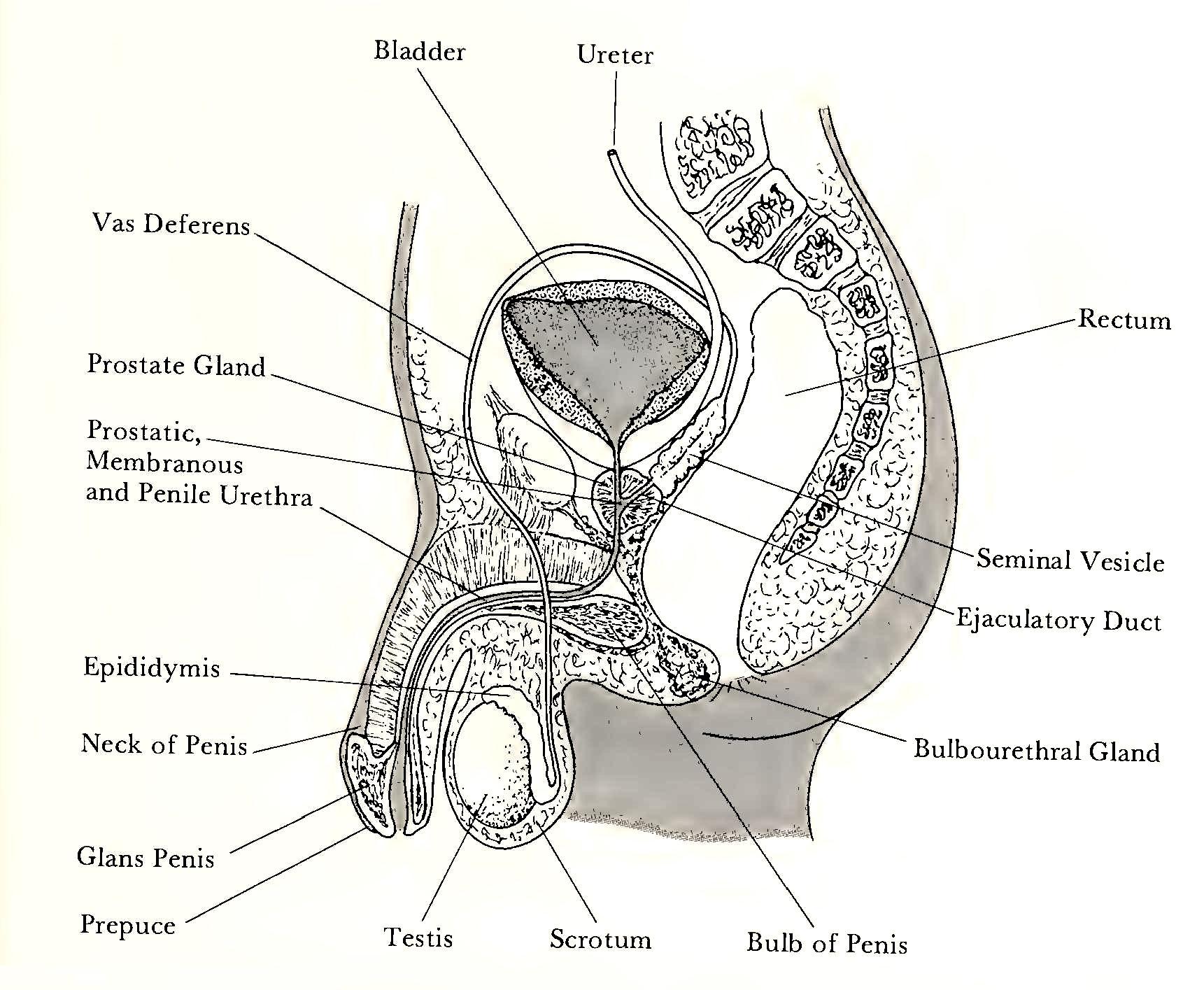

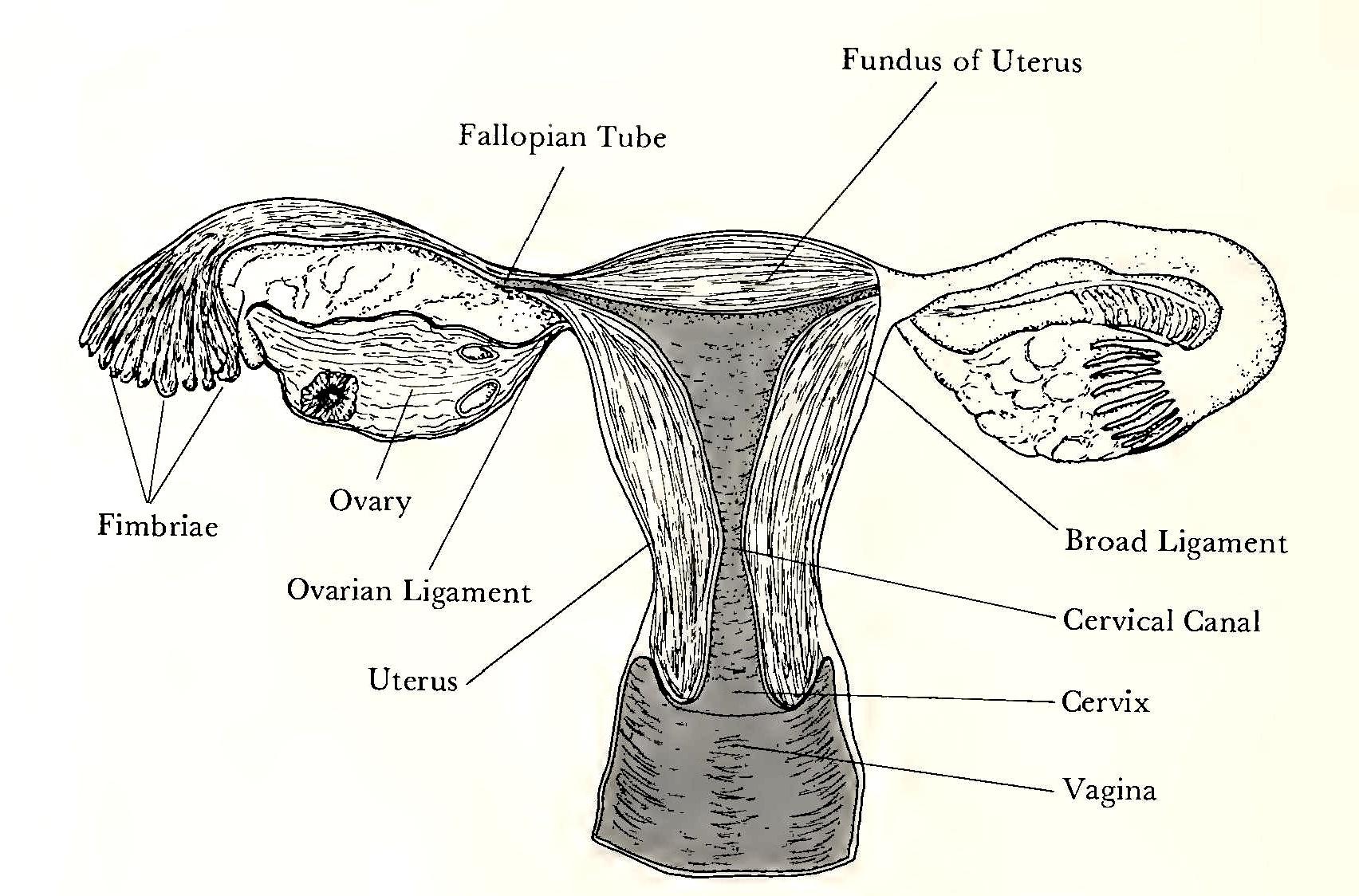

Woman’s body, however, is productive of a number of uniquely female events, shared by almost all women to a greater or less extent and reflected in their experiential histories and in the patterns of their lives. These events include the menarche and the subsequent rhythm of menstruation, breast development, pregnancy, parturition, lactation, and menopause. All are relevant to woman’s role as childbearer and nurturer, and none of them has a counterpart in man’s experience of his body. Thus the biological referents of the social roles of mother and father are not even comparable, let alone equal.

Surely all these are important events in the lives of women. But the search for a direct effect of the attendant body changes on the psychology of women has so far been a fruitless one. Rather, the effects are indirect, linked to the consequences of these events and to the meanings they have for the woman and for relevant others.

The menstrual cycle, for example, is a rhythmic reminder to women of their bodies, and much has been made of its hormonal fluctuations and associated discomforts. But there is no evidence whatsoever that menstruation constitutes a handicap for women in the pursuits of their daily lives or that it noticeably deters them from performing as capably as nonmenstruating people, other factors being equal (see Chapter 4).

When we speak of the importance of women’s biology for the psychology of women we are talking about reproductive biology. Today, the issue is less whether and how her biology affects her behavior than it is how much she is in control of her body and can choose how she will use it. So far, valid and reliable psychological correlates to the biological events of women’s bodies have not been demonstrated. Thus there is no scientific basis for the systematic differential treatment of women on the grounds that their behavior is functionally related to the great and small rhythms of their bodies.

Gender-role socialization

The differential ways that boys and girls are socialized to conform to the appropriate behavioral norms derive primarily from the long history of division of labor along sex lines, which was necessitated by the biological and socioeconomic facts of life. Most social systems use the facts of biological sex to organize the responsibilities and opportunities that men and women have: “... we observe that women almost everywhere have daily responsibilities to feed and care for children, spouse, and kin, while men’s economic obligations tend to be less regular and more bound up with extrafamiliar sorts of ties ...” (Rosaldo, 1980, p. 394).

Such sex-related role differentiation would not necessarily in itself be problematic for women, except for another “universal fact”: because of the content of women’s roles, an asymmetry is set up whereby human cultural and social forms are dominated by men. But such differentiation is functional in societies in which the greater strength of males is put to good use in hunting and foraging activities or in physical defense and conquest; and where the bearing and rearing of children is left to the women. In industrialized societies in which physical strength for work or for war is not so important, the rationale for such bifurcation of personality into male and female models seems not only unwarranted but restrictive and growth inhibiting. A general cultural diminution of sex-role differentiation goes along with a greater valuing of the individual and of ideals of personal freedom, such that the boundaries between behaviors designated as “male” and “female” become more permeable and less rigid.

As jobs and other societal roles are less often tagged as male or female, it is inevitable that socialization practices will change too. They will change together, however. There is little point in desexing child-rearing practices unless both boys and girls have the chance to try out their skills along a continuum of ways of being. Nor will the opening of new work roles be meaningful or successful unless the hitherto ineligible persons have the cognitive styles and personalities to function in them.

Many studies have supported the positive value of moving toward androgynous norms for the socialization of children. Men can be permitted closer contact with their feelings and can develop qualities of empathy and greater concern for others, along with an attenuation of macho need for dominance and display of high activity level and aggression. Women can help both men and themselves by practicing assertion, independence, and poise, and by abandoning the unnatural postures of childishness, helplessness, and docility.

Life chances

Characteristics such as sex, race, ethnic origin, size, physical handicaps, and so on are socially defined. That is, they are given meaning in terms of social norms. On the bases of these meanings, the individual is provided with differential opportunities, which are called life chances. In the past her sex was always a major determinant of woman’s life chances all over the world, the fact that she was born female being the single most important determinant of what she would be doing thirty years hence. Today, the importance of her sex as a predictor is quite variable. The chance that a woman has to escape from traditional role requirements and to exercise some degree of control over her own life depends to a substantial degree on the country, class, and ethnic group into which she was born. Childrearing practices, important as they are, only reflect these variables and the value systems associated with them.

For example, consider a report that offered a global perspective and addressed what may be the most important problem of all: the relation between women’s equality of opportunity and their fertility in both developed and undeveloped countries all over the world (Dixon, 1975). Based on data gathered for a United Nations report on the status of women, the report contained compelling evidence of a strong relationship between women’s status in education, employment, the family, and public life on the one hand, and their reproductive behavior on the other. If one grants that education, employment opportunity, the right to self-determination in one’s personal life, and participation in public life all convey power on the person who has them, and that the extent to which one has power or is powerless relative to others is a determinant of behavior, then these factors become important to the psychology of women.

Personality

The word personality is defined and used in a bewildering variety of ways, to mean everything from an evaluation of one’s charm and vivacity to a description of a set of characteristics which define one as unique from all others. That personality, unlike constructs in the physical sciences such as electricity, eludes precise definition is generally recognized by psychologists. But some definitions are more widely used and respected than others, and one of those is that personality is the dynamic organization within the individual of those psychophysical systems that determine his characteristic behavior and thought (Allport, 1961, p. 28).

Certain key words in this definition merit attention, especially within the context of thinking about the psychology of women. Dynamic organization means that personality is always changing and developing, that it is a process, while at the same time it has a systematic unity which relates its components to each other. This attribute accounts for the stability of a person’s behavior across time and situations. Psychophysical systems recognizes that personality has both psychic and physical components, its organization drawing from both mind and body and fusing them into a unity. The word determine means that personality is an active agent in the patterning of the individual’s behavior. Finally, characteristic emphasizes the individuality of personality, the uniqueness of its particular organization in the individual.

At this point, an emendation of Allport’s definition is in order. Personality alone does not determine behavior. A person, for example, may characteristically be shy and reserved in social situations but under certain conditions may become quiet animated and gay. Therefore, to avoid the implication that personality is the determinant of behavior, let us change it to read:

Personality is the dynamic organization within the individual of those psychophysical systems that interact with situational variables to determine an individual’s characteristic behavior and thought.

The term temperament should be distinguished from personality. Temperament refers to dispositions that are largely biologically derived, such as sensitivity and reactivity to stimulation, emotional lability, and so on, dispositions which are manifest quite early in life, before learning has either attenuated or enhanced them. Temperament has been considered to reflect innate, largely hereditary predispositions to behave in certain ways. Thus, along with such attributes as intelligence and physique, it can be thought of as the raw material of personality (Allport, 1961).

To speak of temperament as biologically derived, as a spectrum of genetically determined predispositions to behave in certain ways, should not suggest that personality traits are inherited, and certainly not that the “feminine personality” is passed down from mother to daughter. It is reasonable to assume that the distribution of such predispositions is the same for both sexes. That is, the “raw material” with which environmental events will interact to shape the person is not systematically different for the two sexes. Although males have a greater predisposition to behave aggressively early in life, they exhibit a wide range of individual differences in the display of aggression, as do females. Clearly, aggressive impulses can be shaped by environmental intervention in the direction either of repression or of release.

Although theorists emphasize different aspects of the various factors that contribute to the development of personality, most would agree that the outcome is determined by the experiential history of the person, the kind and degree and pattern of experiences she has had, impinging upon and affecting the development and maturation of the basic or innate qualities that were there at birth. The behavioral repertoire of the neonate is not large, consisting mostly of motoric and unlearned reflexive behavior like crying and sucking. But individual differences in temperament are observable in very young infants. Thus the uniqueness of the developed personality comes about through the interaction of the person’s unique experiential history, which begins at birth, with a unique set of “givens,” the result being an infinite array of individuals, no two alike.

The importance of this for the psychology of women is that intrasex variability is very large, a fact that is often forgotten in the enthusiastic search for gender differences. Acting on a spectrum of predispositions which may become manifest at different maturational levels are thousands of complexes of events producing reactions which are themselves events, all shaping the personality of the individual woman.

We have discussed four sources which influence the behavior of women. At the present time we have no idea what the relative importance of their contribution is to the behavior of any particular woman. Each person, it has been said, is like all other persons, like some other persons, and like no other person (Kluckhohn and Murray, 1949). If we apply this truism to the study of women, we see that its categories describe the contributory sources of behavior that we have been talking about: biology, socialization, life chances, and personality.

From birth woman confronts the world with a body which is more like all other women’s than it is like any man’s. The socialization pressures of family and school are similar to those experienced by many others in her society. She shares life chances with others of her social class, her race, her neighborhood, and her qualities of health, beauty, and so on. From all this material is organized her ineffable and unique personality, with its substratum of temperamental dispositions.

A general theory of the psychology of women must take all these into account in attempting to formulate explanatory concepts about women. In the meantime, however, it is important to look at some early influential theories of the psychology of women. The theories derive not from psychology itself but from psychoanalysis—a system of human behavior whose explanations of female personality are the subject of the next chapter.

2. Psychoanalysis and the woman question

And now you are already prepared to hear that psychology too is unable to solve the riddle of femininity....In conformity with its peculiar nature, psycho-analysis does not try to describe what a woman is—that would be a task it could scarcely perform — but sets about enquiring how she comes into being, how a woman develops out of a child with a bisexual disposition.