Lisa Downing

Selfish Women

The rise of the selfish woman = the fall of Western society

On critiques of the neoliberal subject

Female “self-fulness,” feminist selves

1. The Psychopathology of Selfishness

On narcissism and norms of gender

Freud’s female narcissist - a deviation from a myth

Rachilde: A female narcissist before (and against) Freud

Post-Freudian views of narcissism

The American Psychiatric Association’s narcissistic personality disorder (NPD)

Towards a conclusion: On the age of selfies and selfish capitalism

2. The Philosophy of Selfishness

On Ayn Rand and rational self-interest

The sentimental education of a selfish woman

Rand’s reverse discourse and its limits

3. The Politics of Selfishness

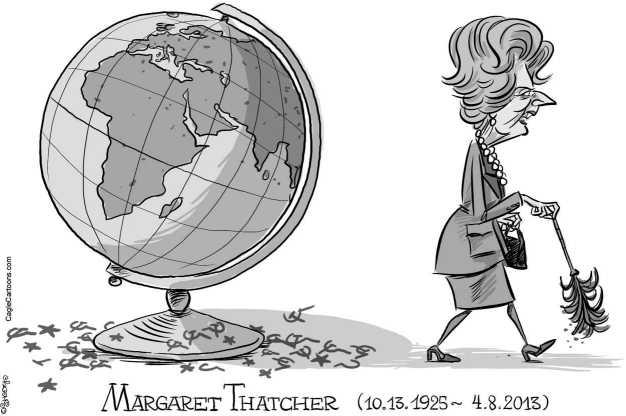

Thatcherism: “I Did It My Way”?

Thatcher’s persona: Between virility and hyper-femininity

Monstrous woman/monstrous mother

4. Personal and Professional Practices of Selfishness

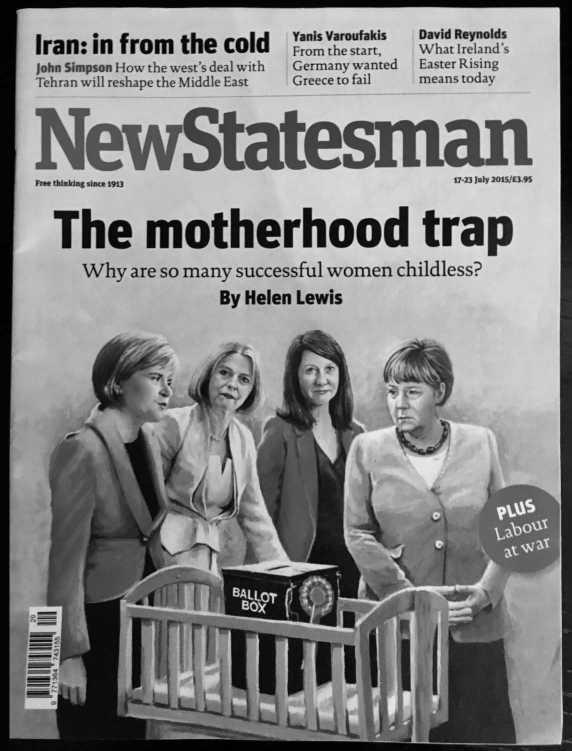

On babies, boardrooms, and ballot boxes

To mother or not to mother? That is the question

5. A Feminist Ethics of Selfishness?

Intersectional feminism and “centring the other”

Radical feminism - and radical self-fulness

Front Matter

Abstract

This book proceeds from a single and very simple observation: throughout history, and up to the present, women have received a clear message that we are not supposed to prioritize ourselves. Indeed, the whole question of “self” is a problem for women — and a problem that issues from a wide range of locations, including, in some cases, feminism itself. When women espouse discourses of self-interest, self-regard, and selfishness, they become illegible. This is complicated by the commodification of the self in the recent Western mode of economic and political organization known as “neoliberalism,” which encourages a focus on self-fashioning that may not be identical with self-regard or self-interest.

Drawing on figures from French, US, and UK contexts, including Rachilde, Ayn Rand, Margaret Thatcher, and Lionel Shriver, and examining discourses from psychiatry, media, and feminism with the aim of reading against the grain of multiple orthodoxies, this book asks how revisiting the words and works of selfish women of modernity can assist us in understanding our fraught individual and collective identities as women in contemporary culture. And can women with politics that are contrary to the interests of the collective teach us anything about the value of rethinking the role of the individual?

This book is an essential read for those with interests in cultural theory, feminist theory, and gender politics.

About the Author

Lisa Downing is Professor of French Discourses of Sexuality at the University of Birmingham, UK. A cultural critic of repute, she was the recipient of a Philip Leverhulme Prize in 2009. Downing is a specialist in interdisciplinary sexuality and gender studies, critical theory, and the history of cultural concepts, with an enduring interest in questions of exceptionality, difficulty, and (ab)normality. She is author or co-author of numerous books, journal articles, and book chapters, and is editor or co-editor of a number of book-length works. Recent titles include The Cambridge Introduction to Michel Foucault (2008); Film and Ethics: Foreclosed Encounters (co-authored with Libby Saxton, 2009); The Subject of Murder: Gender, Exceptionality, and the Modern Killer (2013); Fuckology: Critical Essays on John Money’s Diagnostic Concepts (co-authored with Iain Morland and Nikki Sullivan, 2015); and After Foucault (as editor, 2018). Her next book project is a short manifesto entitled Against Affect.

Praise for the book

”This is a startling, trenchant, and original book. It is written with clarity and passion. It shakes up feminism today in productive and sometimes disturbing ways. Downing’s critical brilliance, command of the material, and uncompromising approach are dazzling.”

Emma Wilson, University of Cambridge

”This is a book that will challenge conventional views of feminism, and of various women who have made a significant impact on modern culture and politics. It fills a significant gap in the scholarly literature and is written in a crisp, accessible style that will invite readers from all ends of the ideological spectrum to re-evaluate their own perspectives.”

Chris Matthew Sciabarra, New York University

”[this book] is going to be a ‘game-changer’ in feminist thinking ... It dialogues with and deconstructs brilliantly French philosophy and ideas on feminism from the previous ‘waves’ to argue that ‘we might adopt the term “self-ful” to describe an ethically aware strategy of self-regard.’ The author’s critical readings of images and discourses and well-known critics are razor-sharp and full of insight on how Western societies construct a toxic mix of praise and misogyny towards ‘exceptional’ ‘selfish’ women.”

Katharine Mitchell, University of Strathclyde

Title Page

Taylor &. Francis

Taylor & Francis Group

http://taylorandfrancis.com][http://taylorandfrancis.com

SELFISH WOMEN

Lisa Downing

Publisher Details

Taylor &. Francis Group

LONDON AND NEW YORK

First published 2019

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

© 2019 Lisa Downing

The right of Lisa Downing to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Downing, Lisa, author.

Title: Selfish women / Lisa Downing.

Description: Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, 2019. |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019009499 (print) | LCCN 2019011466 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780429285349 (ebook) | ISBN 9780367249878 (hardback: alk. paper) |

ISBN 9780367249892 (pbk.: alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Women—Identity. | Selfishness. | Feminism.

Classification: LCC HQ1206 (ebook) | LCC HQ1206 .D74 2019 (print) | DDC 179—dc23

LC record available at[[https://lccn.loc.gov][ https://lccn.loc.gov/2019009499] ]

ISBN: 978-0-367-24987-8 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-0-367-24989-2 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-0-429-28534-9 (ebk)

Typeset in Bembo by codeMantra

Figures

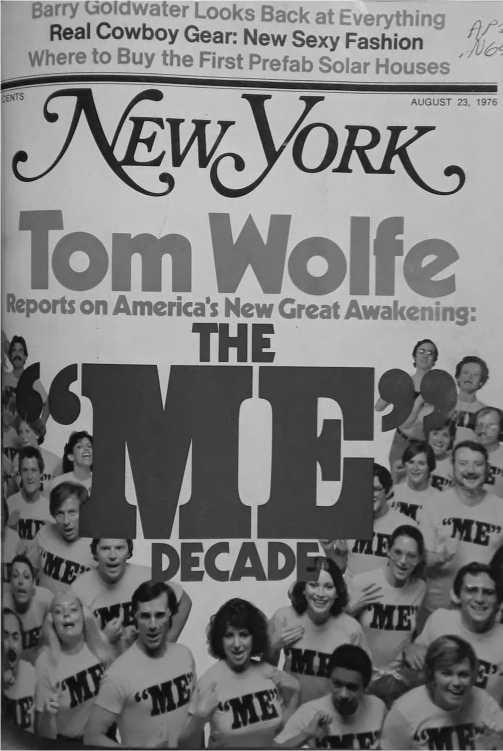

1.1 Cover of New York, 23 August 1976. Photograph by Erna Cooper

3.1 Thatcher swipes Soviet influence off the globe using her feather duster. Reproduced with permission ofCagleCartoons.com

3.2 Thatcher waltzes with Ronald Reagan: “Still the best man in Europe.” Reproduced with permission ofCagleCartoons.com

4.1 Cover of the New Statesman, 17—23 July 2015. Photograph by

Lisa Downing

5.1 Cover of Time, 29 June 1998. Photograph by Rachel Mesch

Acknowledgements

This book began life as my inaugural professorial lecture, delivered at the University of Birmingham in November 2014. For according me two semesters of leave to begin writing this book, I am grateful to the College of Arts and Law at the University of Birmingham. For their individual and collective support in encouraging me to complete the project (including participating in a lunchtime workshop on “overcoming writer’s block”), I thank my colleagues in the Department of Modern Languages, with especial thanks to Monica Jato for her exceptional kindness.

For inviting me to present my material at their conferences, seminar series, or exhibitions, and for giving their time, intellect, and energy to reacting to my ideas, I thank Jennifer Barnes, Sam Bean, Larry Duffy, Jana Funke, Fiona Handyside, Navine G. Khan-Dossos, David Sorfa, Michael Syrotinski, and Edward Welch. A huge “thank you” in particular goes to Bob Brecher and his colleagues at the University of Brighton — Abby Barras, Jacopo Condo, Hannah Frith, Pam Laidman, Toby Lovat, Victoria Margree, Chrystie Myketiak, Carlos Peralta, Liliana Rodriguez, Ian Sinclair, Matt Smith, and Laetitia Zeeman — who workshopped my book prior to publication, commenting in detail on a whole draft of it.

For sharing a pre-published draft of her book Mean Girl: Ayn Rand and The Culture of Greed with me, I thank Lisa Duggan. For helping me to hunt down references or source images and permissions — and going beyond the call of duty in doing so in some cases — I thank Deborah Cameron, Erna Cooper, Martin Farr, Julie Lokis, Rachel Mesch, and Julie Rodgers. For their encouraging comments about, and helpful suggestions on, the manuscript of the book, I thank the expert readers approached by Routledge: Emma Wilson, Chris Matthew Sciabarra, and Katharine Mitchell. All read with tremendous care, insight, and generosity and I am so grateful to them for “getting it.” I also owe a debt of gratitude

x Acknowledgements

to my commissioning editor at Routledge, Alex McGregor, who has been a model of patience and efficiency throughout, and to my trusty expert indexer, Ralph Kimber.

For discussing selfishness and the process of writing about it with me (selflessly and at length), I thank Lucy Bolton, Lara Cox, Tim Dean, Alex Dymock, Robert Gillett, Miranda Gill, Libby Saxton, Nicki Smith, Ingrid Wassenaar, Andrew Watts, and Hannah Yelin. Your friendship and solidarity made the writing process a lot more bearable. And lastly, but very much not least, I need to thank — as always — that incomparable individualist M.B.D., without whom everything in life would be different and lesser.

An earlier and shorter version of my critique of contemporary iterations of intersectional feminism, which appears inChapter 5of this book, was published in a section of Lisa Downing, “Antisocial Feminism? Shulamith Firestone, Monique Wittig, and Proto-Queer Theory,” Paragraph, 41:3, 2018, 364—379. Adapted and extended material from it appears here with the permission of the editors and Edinburgh University Press.

Introduction

Selfish — a judgment readily passed by those who have never tested their own power of sacrifice.

(George Eliot, Silas Marner, 1861)

Selfishness: nothing, perhaps, resembles it more closely than self-respect.

(George Sand, Indiana, 1832)

Selfishness is a profoundly philosophical, conceptual achievement.

(Ayn Rand, “Selfishness Without A Self,” 1973)

“Selfishness” is an exceptionally timely concept for critical consideration; indeed, it is sometimes said to characterize the very cultural epoch in which we live. As a personal attribute, “selfish” is almost always a label levelled against another, and both negatively connoted and morally weighted. Yet it is also a heavily gendered concept, with female selfishness being understood very differently from, and as more reprehensible than, its male counterpart for reasons that are deeply embedded in cultural understandings of the nature and function of women and that work in the interests of a patriarchal status quo. Given that men are supposed to be “full of self” (assertive, confident, self-assured, driven), male selfishness is a minor infraction. For women, who are supposed, in this binary logic that casts them as the mere complement of men, to be life-giving, to be nurturing, to be for the other, and therefore literally self-less, it is a far more serious transgression to be selfish while a woman — indeed it is a category violation of identity. Elsewhere, in a critique of contemporary identity politics, I have developed the concept of “identity category violation” to describe those individuals whose political affiliations or personal actions are at odds with the perceived normative characteristics]]of the group to which they are ascribed. A “selfish woman” is, in this sense, an example of identity category violation.[1] We might also think back to the fact that, in 1792, Mary Wollstonecraft had identified the so-called “feminine virtues” as perversions of true virtues, that is as a way of flattering women while trapping them in a series of unsatisfying roles.[2] There are few “feminine virtues” of which this is a more accurate description than “selflessness.” A contention of this book, then, will be that female selfishness, as a radical and deviant departure from the expected qualities of “woman,” may indeed be properly considered to be a strategic, political, and personal achievement.

Hence, it is not coincidental that the first two quotations of my epigraph above, about what selfishness is and how it may be misrepresented, were produced by nineteenth-century female authors (who also happen to be two of my favourite female Georges). Women artists in eras unconducive to female autonomy were positioned vis-a-vis power in such a way as to have an acute sense of which kinds of people, exhibiting what kinds of behaviours, and threatening what sorts of hierarchies, are likely to attract to themselves the label of “selfish.” According to the third quotation by Ayn Rand, the Russian-American writer who has been dubbed the “prophetess of capitalism,” selfishness should properly be understood as an achievement at a philosophical level in the context of a Christian worldview that promotes self-sacrifice as the highest human virtue. Rand was no straightforward feminist and her statement here deliberately does not ascribe a sex to that selfishness that is an achievement. While not proposing that “Rand was right” in any blanket way, for her pursuit of a project historically denied to women she deserves serious re-reading on her own terms. The fact that, for the most part, she is either vilified or ignored within feminism and the academic humanities, with a few key exceptions, bespeaks a strange sort of ideological purism that passes as ethical but that presses pause on critical thought and intellectual curiosity.

The association made in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries between positions that are explicitly in the interests of the individual and the often illunderstood, yet much critiqued, economic and political philosophy of neoliberalism has had the effect of tainting both the concept of individualism (perhaps understandably) and also that of individuality for those broadly on the left. The classical liberal concept of individualism holds that individual freedom is a more important social principle than shared responsibility, but considers harm to (the freedom of) the other as its ethical limit, while individuality can simply be understood as the notion that human beings need to be acknowledged as different from each other, with valid needs, wants, and equal rights. The pervasive spread of neoliberalism and the perceived severity of its social effects have resulted in the reinforcement of a simplistic moral binary that holds that a focus on the individual self is both selfish and “bad,” while a focus on the other, or the collective, is concomitantly necessarily altruistic and “good.” “Neoliberalism” is too often used interchangeably with “selfishness,” or “individualism,” without reference to the economic component of the system it describes, or the specific history of]]the concept. That said, the concepts overlap in a number of ways in our present moment, and the effects of this overlap are key to how we may think “self” currently and in recent history. Crucially for this project, one of the architects of the neoliberal economic and social project, and a vocal exponent of viewing the individual, rather than collective society, as the basic political unit, was a woman: Margaret Thatcher. Like Rand, Thatcher is a figure disavowed by feminism. She is often described as an “exceptional woman,” a female individual who attained a position of power for herself but left intact the systems that prevent other women from progressing. The representation and self-representation of this exceptional woman are crucial indices of how selfish women are perceived.

Yet, the label of female selfishness is valid not only when considering exceptional and extreme women such as Rand and Thatcher. It is a means by which women are routinely policed and encouraged to self-police, whatever personal and political choices they might make. The decisions that women in the West[3] are charged with making — considering ambition, career, children, family, sexuality, and feminism — are shot through with value-judgment-laden discourses of selfishness, as recognized in the titles of recent books such as Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers on the Decision Not to Have Kids.[4] Yet, while childfree women are routinely demonized for rejecting the role that has traditionally been seen as woman’s “proper” one, women who do become mothers are not exempt from similar charges and also face gruelling amounts of cultural surveillance regarding their level of commitment to motherhood, measured by the various associations that accrue to staying at home or working outside of the home in popular cultural and media contexts and, in psychiatric and psychological ones, by suspicions of narcissistic mothering and “helicopter parenting.”

By reading selfishness in terms of historical and contemporary expectations of gendered subjects, this book proposes to problematize the values commonly ascribed to the selfish/altruistic and individualistic/collectivist binaries. It also sets out to demonstrate the strategic value of a concept of selfishness for specific feminist or pro-woman aims. That is, the book proposes a way of exploring how selfishness and its close neighbours from varied disciplines and contexts — “self-interest,” “self-regard,” “self-actualization” — may be, not only tangentially expedient for a feminist political project in the twenty-first century, but programmatically necessary to it. In order to avoid both the conflation of these terms and the semantic slippage that is inevitable with such overused and freighted words, I will coin a term to exemplify the specific kind of strategic female selfishness that I am going to be considering. To do this job, I propose the term “self-fulness,” as both the direct antonym of what women are traditionally exhorted to be — “selfless” — and as a value-judgment-free alternative to selfishness. The linguistically jarring nature of the neologism “self-ful” is intended to reflect the epistemologically and ontologically jarring nature of the very concept it is designed to describe, as it conjures up something rare, occluded, forbidden, nascent, or not yet fully brought into being.

The rise of the selfish woman = the fall of Western society

In August 2017 the Australian political and literary publication, Quadrant Online, featured an article by Michael Copeman entitled “The Rise of the Selfish Woman.”[5] As an example of the discourses commonly used to coerce women into fitting the stereotypes expected of them, and the logic used to condemn those who refuse, this otherwise pedestrian article is virtually a textbook — and I will use it here to demonstrate exactly what it is that women are up against when they wish to be seen as “selves.” The article begins by describing the cultural changes that have occurred in recent years with regard to the roles allocated to women:

For millennia, almost all women had giving, unselfish roles thrust upon them. And they took these up with alacrity, despite great personal tolls [...] In the meantime, [Western] women have become “liberated” — allowed to work outside the home, to own property, to vote, to pursue secondary and then higher education, and to choose with whom and how often they have children.[6]

For any feminist scholar used to scrutinizing discourse for sexist assumptions, alarm bells ring from the off. These bells announce more than a mere quibble; indeed they sound the need to object vigorously to the redefinition of political history engineered by Copeman in insouciantly slipping in the suggestion that women have been “allowed” to work outside the home, to own property, vote, and so on, as if these “allowances” are acts of generosity that it was up to men to grant in the first place. Rather, women campaigned, fought, and in some cases died to claim these rights as human beings.

The author then goes on: “the result, quite understandably, is that Western women have become more selfish — selfish in the way that men have always been”[7] and “[t]here are some skilled and devoted male nurses. But perhaps it is most men’s innate selfishness that stops most from ever contemplating a nursing career.”[8] There is a significant contradiction here in the status that Copeman seems to believe “male selfishness” to have. On the one hand, he seemingly understands in the first quotation that what he is calling “selfishness” is the result or by-product of socialization. That men have historically been encouraged to live a life that they can shape according to their individual desires, talents, and tastes means that (“most” — note his qualifier) men are especially comfortable with “selfishness.” On the other hand, however, in the second quotation (and despite the repetition of “most men”), he seems to suggest that selfishness is properly — indeed — “innately” male.

The argument that emerges about the rise of a generation of inconveniently selfish women in Copeman’s article focuses on losses to the healthcare profession and social care system heralded by the shortage of women willing to do caring work. He argues that, as a combined result of women becoming more educated,]]the professionalization of nursing as a high-level career, and more women choosing to train as doctors rather than as nurses, we are left with a “crisis” caused entirely by women’s pesky selfishness in seeking self-fulfilment and financial rewards, rather than being committed to caring for the other. “The worrying result,” he writes, “is that our ageing society, with many more of us living with some sort of disability that requires skilled nursing help, is running out of its most vital resource — devoted young nurses.”[9] Note: young women are not people with interests of their own here, but a resource to be deployed in the interests of the state. By referring emotively to “our” impending old age and vulnerability, Copeman makes a manipulative appeal to all right-minded readers to understand that instrumentalizing young women as carers — regardless of their wishes — is somehow morally right.

He goes on:

As young Western women’s options and aspirations have changed, so has the brave new (and more selfish) society they are creating. Today’s average woman does better at high school, is more likely to go to and to graduate from uni, is more able to gain stable employment, is more likely to gain early promotion, and in some areas (e.g. medicine) is coming to dominate professions that 150 years ago were off limits to the “fairer” sex.[10]

That boys doing better at school than girls is commonly seen as natural and desirable, and the opposite state of affairs as some sort of apocalyptic crisis, is a phenomenon oft-commented-upon by feminists. It is a trope routinely produced by Men’s Rights Activists (MRAs) and others who decry a “feminization” of education, allegedly correlated to, in Christina Hoff-Sommers’s words, “feelingscentered, risk averse, competition-free and sedentary” schooling styles,[11] as well as to the low number of men teaching in primary schools. That little to no substantive research supports these claims does nothing to calm the frothing anti-feminist zeal with which they are regularly produced.[12]

Copeman continues:

The flip side of this fast female advancement is that more men drop out of high school, fail to gain tertiary qualifications, have poor or unstable employment records — and are much more likely to be involved in risky behaviours (speeding, alcohol and drug abuse, gangs, criminal activities and suicide). Of course, those failures are not primarily women’s fault (although there is an argument that today’s mothers can/do devote less time to bringing up their boys to succeed, and thus more boys end up in low and risky avenues of life). Yet, today’s women pay a price if they are unable to find a partner who can equal or complement them, or even stay the course.[13]

These three sentences contain a plethora of strands and varieties ofwoman-blaming. First, an equivalence is made between “female advancement” and the sad plight]]of men, implying a relationship of correlation or even causation and suggesting that success is a zero-sum game of gender warfare. To this is added a swipe at women for not being sufficiently solicitous mothers of boys, for increasingly working outside of the home and/or beginning to view themselves as multifaceted human beings as well as parents. When it comes, the back-handed assurance that he is not blaming women for daring to want to be selves rings hollowly — and is, in any case, immediately undone with that fatal word “although.” Finally, the explicit heteronormative conservatism of this statement and of the article as a whole is made clear in the presumption that what women want most is inevitably and invariably to “settle down with a man.” Also obvious is the barely disguised epicaricacy of telling women who do want this outcome that their bloodyminded and emasculating independence is precisely what will deprive them of it.

This is an author who clearly considers the prospect of selfish women as something deeply unnatural. Consider the following: “But the sad truth may be — as women increasingly adopt a selfish male disregard for the less-well-off — that governments can’t keep up with the goals they have foolishly and deceptively set.”[14] Here, selfishness is understood again as properly male, and male self-interest is understood as appropriate, whatever its deleterious effects on the poor, old, and sick — as responsibility for them lies squarely with women. The continued survival and thriving of this “male selfishness,” regardless of societal consequences, is hoped for by the author; it is clearly the women inconveniently attending to their own self-interest who are the problem here. Had they stuck to their proper place, caring for the children, the sick, and the old, the men could continue being as selfish as they always had been — and “the government” would be exculpated for failing to meet its targets. Finally, Copeman comes clean: “In short,” he writes, “the rise of the selfish woman may be sowing the seeds of destruction of our socalled compassionate society.” A less compassionate society is, in fact, all women’s fault, despite his earlier, mealy-mouthed caveats to the contrary.

The lazy biological essentialism underpinning the argument is made explicit in the next statement:

No, there is nothing wrong in our society with anyone doing a job that requires unabashed service to others, and is rewarded more with satisfaction than oodles of cash. In fact, our society has always depended on most workers taking this approach. Yes, men should be enabled and encouraged to assist with all the formerly “female” tasks (except actually bearing children and breastfeeding) — but, no, their roles in these areas will never be equal to those of the more genetically-adapted and usually better-suited women.[15]

While pointing out that male-bodied people cannot give birth and breastfeed should be uncontroversial, the notion that women are somehow “more genetically-adapted” to the work of wiping bottoms and cleaning up mess that constitutes a large part of “caring” is an outrageous example of opportunistic false logic. In an article from 2003, concerning the legal ramifications of gender]]stereotyping assumptions, Caroline Rogus writes: “caregiving and childrearing are not necessarily instinctual, but are learned cultural experiences separate from the experience of pregnancy and birth.”[16] Yet, the deeply ingrained cultural belief that these are innate characteristics of women, of the same order as the biological capacity to give birth, leads not only to cultural stereotyping and prejudice, but to legal judgments that impact women. Rogus uses the example of the Nguyen v. Ins judgment in the USA, in which the son of a non-citizen mother and a citizen father, who had been found guilty on criminal charges, was treated in violation of citizenships laws, on the grounds that it was presumed that the child would have bonded more with the non-citizen mother because, using logic based “not in biological differences, but instead in a stereotype, [...] mothers are significantly more likely than fathers to develop caring relationships with their children.”[17] In this case, the statute governing the naturalized citizenship of children born to a citizen father and non-citizen mother was seen to violate the guarantees of the Equal Protection Clause. Rogus claims: “the Court’s decision could have a lasting impact on preconceived ideas of gender roles”[18] and that “sex-based generalizations both reflect and reinforce fixed notions concerning the roles and abilities of males and females.”[19] These fixed notions are not just the idle views of one journalist, then, but deeply pervasive cultural beliefs and fantasies that may shape the way that justice works, as well as the way that we understand culture and each other.

Returning to Copeman’s article, having repeated the well-worn canard about women’s biologically programmed propensity to care, he strikes the ultimate hyperbolic rhetorical blow: “The unmitigated rise of the selfish woman may [.] help hasten the fall of Western society — as we cease to provide the care that our weakest and oldest need.”[20]The fallaciousness of Copeman’s outrageous statement here is easily revealed. We are constantly warned that automation is in danger of taking away human jobs — in the light of this, why does he not suggest prioritizing the development of artificial intelligence applied to caring tasks? Such a suggestion may, in fact, be an extension of the logic of Xenofeminism, a recent branch of pro-technology feminism that has emerged as a response to impasses in feminist theorizations of care.[21] Yet the male journalist would much prefer that women return to their proper role — as he sees it — rather than fulfilling their individual ambitions (and, of course, the women most likely to be deployed in this way are working-class women, women of colour, and immigrant women — all of whom are the subjects most disenfranchised from lives built on considerations of choice and taste).

The journalist’s insistence that women have a duty to sacrifice their individual self-interest for the greater good may well lead the feminist-minded reader to consider the unpopular idea that a strategic dogged insistence on female individuality rather than social collectivity may lead to better outcomes for women. One major reason why such an idea is currently unpopular among some feminists can be laid at the door of discourses that circulate around the idea of “neoliberalism.”

On critiques of the neoliberal subject

Many critiques of the perceived selfishness of our age in the highly developed industrial nations of the West are linked to the pervasiveness of the effects of “neoliberalism” and the ways in which its logic has insinuated itself into all facets of life — including into feminism.[22] In the introduction to a Special Issue of New Formations on “Righting Feminism,” Sara Farris and Catherine Rottenberg write that neoliberal capitalism has “incorporated feminist language in order to further intensify capital accumulation — and that this incorporation was facilitated by feminists’ abandonment of a materialist critique.”[23] They go on:

Using key liberal terms, such as equality, opportunity, and free choice, while displacing and replacing their content, neoliberal feminism forges a feminist subject who is not only individualised but entrepreneurial in the sense that she is oriented towards optimising her resources through incessant calculation, personal initiative and innovation.[24]

Allowing the taint of “neoliberalism” to provoke suspicion of all iterations of the liberal values set out here — especially choice and individualization — runs the danger of sacrificing them in the interests of ideological purity. This would be a strategic error for feminist thinking, if that feminism wishes to work in women’s interests. What is partly at stake in such critiques of both liberal and neoliberal concepts is the fact that too much focus on the individual is itself felt to be deeply unfeminist by many. In part, obviously, this is because of the collective origins of feminism as a social movement and its association with the left. But also, I contend, this is because the phantasy of woman as innately caring, collective, and compassionate, as discussed in the context of Copeman’s article above, is the ghost that haunts feminism every bit as much as it haunts patriarchy.

Accordingly, it is possible, though seldom attempted, to make a feminist argument that living in a “neoliberal” world may have some compensations for women. One such compensation may be the fact that, at the very least, it provides some frameworks through which women might think themselves as independent individuals for perhaps the first time in a long history that has seen women as the possessions of fathers and husbands. The results of a combination of feminist struggles for rights of personhood (liberal struggles) and the current focus on the production of economic subjects mean that the much-critiqued “atomization” of society has — at least — created the possibility for those women who want to live outside of a milieu restricted to, and entirely predicated on, family and community to articulate and imagine these desires. However, the flip side of this potential is the hard cold fact that neoliberal policies, such as the deregulation of the banks in the USA and UK, in combination with wage stagnation, has led to a housing bubble putting affordable homes out of the reach of many women who would love to live as the “individuals” that neoliberalism promises they can be — i.e. alone — as well as out of the reach of families. Indeed, the]]negative financial effects of neoliberal policies may justify critiques of the system, but unfortunately this too often leads to a conflation of these negative economic effects, that have been argued to disproportionately affect women,[25] with the very idea of individuality which the figure of the neoliberal subject has helped to shape and describe. The result is that the valid female desire for individuality is demonized along with the current system in which the desiring is taking place. While not defending neoliberalism as an optimal mode of social organization, then, I would nevertheless like to make room to consider that some of the premises of neoliberalism may — at the very least — be a mixed bag for women and I would also counsel taking care to separate an ideal of individuality from a particular mode of governance.

It is worth noting that critics of neoliberalism are often unclear or in disagreement about their definition of the term, despite its pervasiveness as a generic term for our various contemporary ills. In A Research Agenda for Neoliberalism, Kean Birch argues that “[n]eoliberalism is [...] a word predominantly, if not exclusively, used in left-wing or centre-left circles.”[26] And:

It is primarily used as a derogatory or pejorative term to refer to someone who holds certain beliefs. Namely, that markets with no or very limited government intervention in restricting competition are the best — or “natural” — way to organize our economies and also our societies. This is based on the claim that markets are efficient, in that they lead to the lowest cost and resource use, and also moral, in that they support individuality, autonomy and choice.[27]

In a review of Birch’s book, Christopher May concurs that

students from undergraduate to PhD level, as well as academics and other commentators, use the term as if we all knew what it meant, and as a catch-all prejudicial accusation levelled at any aspect of the contemporary political economy they find unacceptable or malign.[28]

The term itself is often thought to have originated at the Colloque Walter Lippmann, organized in Paris in 1938 by French philosopher Louis Rougier, but even this point of origin is disputed. Its development is associated with several separate, but contemporaneously emergent, economic schools, including the Austrian school of economy, represented by Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises; the Chicago School of Milton Friedman and Gary Becker; and the German Freiberg or “Ordoliberal” School associated with Wilhelm Ropke and Alexander Rustow. Following the Second World War, a number of Centre-Right think tanks were set up to theorize the deployment of free market economics for recovering Western economies, including, in the UK, the Institute of Economic Affairs (established in 1955) and the Adam Smith Institute (1977), and, in the USA, the Heritage Foundation (1973) and Cato Institute (1974) which emerged]]as reactions against the interventionist governmental policies associated with the “New Deal.” These institutes promoted free-market ideology up to the governance of Reagan and Thatcher who implemented it on a large scale in their countries’ respective economic policies.[29] Until the 1980s, so-called “neoliberals” had often used the term to describe themselves and their political position. It became a pejorative term in the 1980s, following the effects of Thatcherism and Reaganism. Increasing globalization and the domination of large corporations with influence over governments have been theorized as responsible for recent electoral decisions such as the vote to leave the European Union in the UK and the election of protectionist, nationalist presidential candidate Donald Trump in the USA. Writers such as Naomi Klein and George Monbiot lay such phenomena at the door of “neoliberal” policies.

Those propounding a left-wing condemnation of neoliberalism tout court tend to assume that it contains no elements intended to improve life for citizens and that, as a model, it is in some way inherently dehumanizing in comparison to more collectivist or socialist models. In an article for The Week entitled “What Neoliberals Get Right,” Damon Linker writes:

A libertarian or far-right Republican treats the market as sacrosanct and the government as a parasite that contributes little of value. A socialist begins with the state and the substantial list of social goods it should provide and views with suspicion the economic activity that takes place in the private sector. A neoliberal differs from both in regarding the market and the government as potential and rightful collaborators in generating opportunity and providing protections that will elevate standards of living and improve overall quality of life for the greatest possible number of citizens.[30]

While many would argue that the aim of “elevating standards” and “improving quality of life” has failed for the majority, the philosophy that underpinned what has become known as “neoliberalism” itself deserves more scrutiny for the potential it contained. In fact, it was a philosophy that fascinated Michel Foucault, a theorist and critic of systems of power as well as an exponent of new ways of imagining freedom, in his last years. Foucault’s 1978—1979 lectures at the College de France, translated into English under the title The Birth of Biopolitics, focus, despite their title, not on biopower, but on the form of governance that is now known as neoliberalism.[31] The lectures were delivered at the very moment that Thatcherism and Reaganism took hold in the Anglosphere, and they were published in English at the height of the global financial crisis in 2008.[32]

Foucault’s lectures build up a history — or better genealogy — of forms of governance, from a “classical” liberal economic model to the emergent “neoliberalism” of the late-twentieth century. Building on the model of panoptical power introduced in Discipline and Punish (1975), Foucault expands the metaphor from that of a literal panopticon, as per Bentham’s prison architecture as a structure in which self-surveillance and self-policing are encouraged, to a way]]of understanding liberal economic philosophy. He describes how an early liberal form of governance can be understood as connecting state and market by promoting disciplinary techniques of surveillance that enable economic freedom. So, the state creates conditions of market freedom and then surveys the behaviour of the market, with intervention as a last resort.[33] Neoliberalism, by contrast, is understood by Foucault as a departure from classical economic liberalism with the free market placed at the very heart of governance. Focusing particularly on the German Ordoliberal group’s revisionist model, Foucault notes the move towards adopting “the free market as an organizing and regulating principle of the state [...] In other words a state under the supervision of the market rather than a market supervised by the state.”[34] In tandem with this change of organization, there is a shift in focus from the market understood in terms of free exchange, as for a classical liberal such as Adam Smith, towards the market understood as a mechanism of both exchange and competition.

Turning from the German model to the American one, Foucault notes that in the US context, in contradistinction to the European one, liberalism has been “the recurrent element of all the political discussions and choices of the United States.”[35] Focusing on the work of Gary Becker, Foucault highlights the kind of subject produced by US neoliberalism: an individual who makes choices, called homo economicus. Economics thus becomes the business of “the internal rationality of [.] human behavior,”[36] such that “homo economicus is an entrepreneur, an entrepreneur of himself.”[37] In an overview of Foucault’s history of neoliberalism, Nicholas Gane describes this as “the birth of a subject that can be reduced to a form of capital and individualized according to its choices and behaviours.”[38] Gane summarizes that the trends Foucault charts mark a shift towards more and more aspects of life being viewed through an “economic grid,” including even “relationships between mother and child, which can ‘be analyzed in terms of investment, capital costs, and profit — both economic and psychological profit — on the capital invested’.”[39]

Scholars of Foucault and neoliberalism differ on the question of whether the French thinker offered merely a descriptive and analytical genealogy of the emergence of an idea in his lectures or whether he was attracted to the philosophy of neoliberalism and the subject positions it potentiated.[40] Some believe that, owing to the partiality of the history, the ways in which neoliberal politics expanded after Foucault’s death (with the extent of the influence that multinational corporations would go on to have, in particular, being unimaginable at the time of his writing), and the suspicion hovering over Foucault’s approval of the concept, his lectures are of limited use as critical insights into the emergence of neoliberalism.[41] Others argue that they provide a useful basis for consideration of the implications of neoliberal spread beyond the end of the 1970s.[42] Michael Behrant points out some of the ways that the broader precepts of Foucault’s system of thought share features with neoliberal reason. Primarily, the model of power Foucault developed, that is understood as normative and reactive, rather than top-down or juridical, resembles a neoliberal form of power more closely]]than a Marxist dialectical one. Further, Foucault was suspicious of the powers of the state and of small statism and critical (to the horror of many of Foucault’s followers) of social security, viewing it as “the culmination” of biopolitical control.[43] Gane writes of what he sees as the most valuable aspects of Foucault’s lectures: first that he “refuses to treat neoliberalism as a single discursive entity” and second that he recognizes “neoliberalism as a form of political reason,” that is “as a serious political and epistemological project rather than [...] as mere ideology.”[44] To conclude, Gane suggests that we consider the ways that Foucault’s lectures pose the key question: “what can truth and the self be outside of their current capture by the market?”[45]

Foucault’s methods and theories have undoubtedly been relevant for many feminist critiques of the neoliberal female self, such as Rosalind Gill’s notion of “sexual subjectification” and her critique, with Shani Orgad, of “confidence culture” (the glut of recent confidence-building techniques and technologies, including self-help, confidence coaching, and assertiveness training, especially aimed at women).[46] While nominally sharing Foucault’s open and speculative analytical energies — they claim to be thinking “about the relation between culture and subjectivity in a way that is not reductive, deterministic, or conspiratorial’[47] — the logic of Gill and Orgad’s formulations, like many other left-oriented analyses, presuppose that the forms of subjectivity produced under conditions of neoliberalism are inevitably and only negative, and that the antidote to “individualism’ must be collectivism, rather than, for example, a restoration of the values of earlier modes of liberalism. For example, they state that truth can never be found in seeking “individual solutions to structural problems.’[48] While this is, of course, true, equally looking only to collectivism as a catch-all “cure’ ignores the crucial importance of nourishing individuality.

Similarly, in an article on the expectations placed upon twenty-first-century women to aspire to perfection, Angela McRobbie argues that “an ethos of competitive individualism’[49] predominates in culture, with some horrific consequences, such as the example of teenage girls who commit suicide as a result of being bullied “for some breech of teenage female etiquette.’[50] Like Gill, McRobbie underpins her reading with a Foucauldian model of subjectification, as seen when she defines perfection as “a heightened form of self-regulation based on an aspiration to some idea of the ‘good life’.’[51] McRobbie writes of the way in which neoliberal iterations of feminism equate “female success with the illusion of control, with the idea of ‘the perfect’.’[52] Like Gill and Orgad, she blames this turn to “individualistic striving’ on the discarding of the “older, welfarist, and collectivist feminism of the past.’[53] One possible objection that could be made here is that the character of the technologies of “individualized perfection’ critiqued by McRobbie is that of conformism; it is not a matter of individuality at all. To the problem of the “atomization’ of “neoliberal’ culture, the “welfarist and collectivist’ imperative is posed as the properly female, feminist solution. However, the path to self-fulness, I would argue, can lie in neither direction (unthinking compliance with neoliberal norms or an idealization of collectivism), but must be found in a third way.

Both articles also agree that techniques such as those promoted by “confidence culture” and the culture of perfection are totalizing insofar as they encourage “turning inwards and working on the self through self-monitoring, constant calculation and the inculcation of an entrepreneurial spirit.”[54] Although these features of contemporary culture are immediately recognizable, I wonder about the insistence on the term “constant” and the suggestion that there is no way of countering the trend described. What is absent in the analysis of confidence culture here is the understanding that these are strategies and technologies that individuals can partially use, accept fully or, indeed, resist. (The key Foucauldian notion of resistance is, in fact, greatly downplayed in these works.) The phenomena that Gill and Orgad and McRobbie discuss may be culturally widespread, but they are not totalitarian. Neoliberalism’s modus operandi is, I would contend, pervasive, not coercive. Its power consists in its ability to insinuate itself into all corners of life, like the “lines of penetration” Foucault evokes to describe the workings of modern power, at the point of convergence of which are our bodies and selves, and against which there is “no single locus of great Refusal,” rather “a plurality of resistances, each of them a special case.”[55] And, in line with the Foucauldian conception of power and resistance, I would argue that in each case described by these writers, it is incumbent upon women to question whether a given cultural current or trend works in or against their own self-interest; whether a strategy is worth adopting, using against the grain, or resisting. To deny this possibility (ethical exigency?) is to assume that living “under neoliberalism” renders the individual entirely incapable of evaluating critically the materials encountered in daily life or of engaging in strategic deployment/rejection of the technologies with which one comes into contact.

The current book does not attempt to provide a wholesale defence of neoliberal subjectivity (indeed, the analysis inChapter 5will offer a critique of some discourses and phenomena within postfeminism and certain recent iterations of intersectionality that seem to use a logic that may be termed “neoliberal” on the grounds that they are not conducive for imagining a more productive female self-fulness). However, throughout, I will attempt also to consider the possibility that the individualization of culture in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, often assumed to be the outcome of neoliberalism, might in some ways have offered and continue to offer women a better deal than a purely collectivist social alternative. This experiment in thinking should not, in turn, preclude our imagining more creative and productive forms of individuality after, beyond, or in excess of neoliberalism.

Female “self-fulness,” feminist selves

The counterintuitive, because counter-discursive, phrase “the virtue of selfishness” is heavily associated with Ayn Rand, who gave this title to her 1964 collection of essays. In The Virtue of Selfishness (1964), Rand provides the following, simple definition of selfishness: “selfishness is concern with one’s own interests.”[56] She goes on to state that being “the beneficiary” of one’s own “moral actions” is “the essence of a moral existence.”[57] The Oxford English Dictionary’s definition of selfishness, however, caveats the term in a way that Rand’s definition doesn’t. Here, selfishness is being “devoted to or concerned with one’s own advantage or welfare to the exclusion of regard for others.” Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary similarly defines it as “regarding one’s own comfort, advantage, etc., in disregard, or at the expense, of that of others.” Peter Schwartz, author of a provocatively entitled, Objectivism-influenced book, In Defense of Selfishness, claims that the term “selfishness” is commonly used as a straw man and argues that “defining selfishness in this manner makes it seem that the harming of others is an integral part of the concept.”[58] Indeed, feminist Rand scholars Mimi Gladstein and Chris Sciabarra explain that “Rand [...] opposed ‘brute’ selfishness, which posits the sacrifice of others to one’s own ends.”[59] A key precursor of this idea of a rational selfishness is German philosopher Max Stirner, assumed to be an influence on Friedrich Nietzsche and the existentialists, who wrote in 1844 of a kind of rational egoism in which “self-ownership” of the individual is a moral and psychological good. Stirner theorized that the “willing” egoist satisfies their own desires while imagining those desires to be greater than the self, or transcendent, while the “unwilling” egoist is aware that the exercise of their will is in pursuit of their subjective needs, but achieves a kind of transcendence through it. This transcendence is not theistic, but is one in which the exaltedness of the human is realized.[60] One aspect that many commentators ignore in critiquing or defending selfishness or egoism, however, is that both the moral-value-judgment-laden dictionary definitions of selfishness and Stirner’s and the Randians’ (albeit very different) attempts to achieve a descriptive version of it, that frees it from its association with vice or sin in a Judeo-Christian tradition, have particular significance when applied to women that they do not have when applied gender neutrally (or indeed to the bearer of the masculine pronoun that Rand and her followers relentlessly — and regressively — use as their universal).

If, for the moment, then, we take “selfishness” to mean no more than “concern with one’s own interests” or “self-interest,” it opens up two obvious questions, that are at the heart of both philosophy and feminism: (1) What is meant by “self” and (2) how are we to know if a given action or decision is in the interests of that elusive “self,” especially in the light of analyses that argue that, in the present moment, the neoliberal machine co-opts the possibility of perceiving real self-interest? Much work in feminist philosophy has problematized what Cynthia Willet, Ellie Anderson and Diana Meyer describe as the “dominant modern western view of the self.”[61] This hegemonic figure is modelled on a white, male, heterosexual, upper-class subject (though this is not, of course, acknowledged in the Ur-texts) following broadly two models: first, that of Kant’s ethical subject, who uses reason and will to transcend the norms imposed by culture; second, the “homo economicus,” discussed by Foucault in the context of the birth of neoliberalism, who operates strategically and hierarchically within a market-based field to satisfy selfish desire.[62] Both of these models are of individuals existing]]apparently in isolation, seeking their own ends. Feminist philosophers have recognized that a cultural dimension obtains in the formation of the idea of self. This is key not only to understanding the bias written into the concept, but also to identifying the lack of awareness of such bias on the part of those who did the defining. Willet et al write: “It is precisely the failure to acknowledge that the question of the self is not narrowly metaphysical that has led to philosophy’s implicit modelling of the self on a male subject.”[63] They argue that a notion of self, devoid of cultural contextualization and devoid of an awareness of power relations, is perforce partial.

While some liberal thinkers (including non-feminist-identified theorist of selfishness, Ayn Rand) would merely wish to make the existing category of self flexible enough to incorporate women too, where historically it has legally and practically excluded them in the context of their status as chattel, others have declared this “masculine” idea of “self” unfit for purpose for women, since it has been constructed not to exclude women accidentally or contingently, but rather to do so systematically and structurally. As Simone de Beauvoir writes, borrowing the Hegelian logic of the master-slave dialectic: “He is the Absolute. She is the Other,”[64] and “Man dreams of an Other not only to possess her, but also to be validated by her.”[65] Beauvoir identified the absence of a fully conceptualized female self as a given in Western thought and culture to be the key ontological and political problem facing women. Woman, as “complement,” has by definition not been in possession of self. Since the female subject is defined in contradistinction to what man is, Willet et al. point out that: “one corollary of selfhood is that women are consigned to selflessness — that is to invisibility, subservient passivity, and self-sacrificial altruism.”[66] It is according to this understanding, then, that a selfish woman is culturally apprehended as unnatural. She is filled with something she properly ought not to have; she is, to use my term, too “self-ful.”

Some feminist philosophy has attempted to rethink selfhood in ways that more adequately represent female experience than the available Western models of an atomized self described above. Drawing on Beauvoir’s claim that it is the strong association between woman and body, and especially woman’s role as childbearer, that traps her in the realm of immanence (socio-historical and personal contingency), rather than allowing her equal access to the transcendental (the realm of radical freedom with regard to one’s capacity to make one’s life into a chosen project), attempts have been made to revalue the bodily realm of experience as central to selfhood. This is not Beauvoir’s strategy to respond to the problem she identifies, it should be noted. Beauvoir instead urges both men and women to renegotiate their positions with regard to immanence and transcendence, allowing the maximum potential for freedom, while contesting the radical independence of the Kantian model of self for any one of us, since we are all socially, historically located subjects.

Some philosophers working in the traditions of Continental philosophy, such as Luce Irigaray, and Africana philosophy, such as Patricia Hill Collins, have]]proposed in place of the model of sovereign individualism an “ethics of eros.”[67] This describes a connected, affective mode of being in which the self is understood as relational. In the Anglophone analytical tradition, a parallel “ethics of care” emerged through the work of Carol Gilligan, Sara Ruddick, Hilde Lindemann, and others. These parallel paradigms from different traditions highlight the relational self, the self that comes into being through giving birth, being born, and interacting in social networks. They foreground the notion of bondedness that is seen as essential to subjectivity and as disavowed by what is perceived to be the masculinist model of individualism. The varieties of eros ethics discussed here draw on the idea that the damaged or severed social bond may be repaired through the freeing of libidinal drives, taking inspiration both from psychoanalysis (in Irigaray’s case) and from non-white traditions of “othermothering” (i.e. nurturing bonds beyond biological kinship), in the case of Africana feminisms. This strategic way of thinking female selfhood emphasizes the properly agentic nature of childbirth and caregiving. Critiques of the “masculinist” concept of a radically independent self point to the extent to which such models tend to involve a negation of being woman-born and brought into the world by another. In the North American tradition in particular, much emphasis is placed in ethics of care literature on decisions that women have to make around pregnancy, birth, and/or abortion, leading to the creation of what Lindemann describes as the “practice of personhood.” This is the practice of “initiating human beings into personhood and then holding them there.”[68]

While these are valuable ways of redressing and relativizing the dominant model of Western subjectivity, taking on board both biological female lived experience and the realities, priorities, and differences of non-white cultures, these models may risk overvaluing the ethical import of female biological processes to a degree that may seem essentializing, normative, and regressive to many of us today. While I fully appreciate the creative attempt to redeploy against the grain the masculinist view of what self is, and what women as not-quite-selves are, and to value that which has been despised for being related to femaleness and femininity, one objection I have to feminist projects of this kind is that they assume that the experience of women under patriarchy is the expression of a “self” that will also best be suited to the freedom from patriarchy that is feminism’s aim.

If the self is indeed more mutable and less absolute than the masculinist phantasy of it,[69] it seems unhelpful in some ways to base the revised feminist self on an iteration of woman’s subordinate role. Another objection is that while we are all — whatever our gender — indisputably born and therefore linked through birth to others, not all women give birth, want to care for others, or — taking on board concerns from disability, intersex, and trans activisms and theory — are biologically equipped to give birth or to feed a child, even if they wished to do so. One of the dangers, then, of basing selfhood on normative female biological behaviours is that it excludes non-normative women. A concept of personhood that depends on biological reproduction cannot help but feel somewhat reductive, essentialist, Darwinian, and unfriendly to a more queer-inflected view of self.

Finally, to emphasize feeling when re-imagining female selfhood is already to be in the position of repeating, and so having to recuperate, a patriarchal, binary discourse that puts women on the side of emotion or unreason. As Laura Sjoberg and Caron E. Gentry posit in their study of violent women, “Very few researchers actually depict violent women as rational actors.”[70] The same can be said, as we shall examine in this book, of selfish, individualistic, and exceptional women, whose violence is only symbolic. And, more generally and damningly, the same can be said of women in general. To adopt rationality as a strategic part of a re-imagined female selfhood can be seen as an audacious riposte to the original masculinist co-opting of reason for men and ascription to “the other” — to women — of emotionalism. It is for this reason that when emphasizing the strategic use of reason in the construction of female lives I shall borrow Rand’s favoured term “self-interest,” in preference to “selfishness” or “self-fulness.”

Methods and contents

In the analyses that follow in this book, I will employ, borrowing a term from the writings of Foucault, a diverse “toolkit” of critical and analytical methods for interrogating the concept of gendered selfishness and the discourses that treat it, rather than a single, unified theoretical framework. The first tool in my kit is a particular feminist lens. This whole book is underpinned by a definition of feminism that I particularly like, namely “the radical notion that women are people,” coined by Marie Shear.[71] Such a definition centres on women as human beings, who are just as complex in their tastes, needs, political affiliations, and so forth, as men. Some women will be caring, but others will be self-interested, ambitious, and power-seeking. It is my assertation that an imposed ontological category label — “woman” — should not be permitted to sanitize and excise such human differences (individuality). On the other hand, the analyses in the book are critical of certain tenets of some branches of feminism. These include the feminist suspicion around the notion of exceptionality, encapsulated in the pejorative concept of “exceptional woman syndrome.” The argument goes that “by making a point of the exception, the rule is reinscribed,”[72] such that female excellence becomes the object of suspicion, considered as something with which to keep down other, “ordinary” women, rather than as something that could be inspirational or transformative. It is to this degree that Julia Kristeva, in considering the power of “female genius,” wonders whether she can even call herself a feminist since she celebrates and valorizes exceptional women.[73] Another discourse issuing from feminism about which I have some concerns is the exhortation, made in some contemporary branches of feminism that have taken up (and, I would argue, deformed), the notion of “intersectionality” to “decentre” the self and one’s self-interest in an effort always to raise up the interests of any perceived more vulnerable sub-group or sub-category than the one to which you “belong.” I shall examine my objections to this trend at length inChapter 5.Thus, while feminist analysis is one of my tools, it is also one of the objects of my scrutiny, and different branches of feminism, where they undermine a message of female self-fulness, will be critiqued in these terms.

My second major tool, drawing on my long-standing Foucauldian leanings, will be a specific kind of discourse analysis that is especially sensitive to, and aware of, the reverse-discursive function that concepts such as “selfishness” may serve. This means that when female selfishness is embraced as a good, this has to be understood in the context of a political-discursive field in which female altruism is the coerced norm, and in which selfishness attracts knee-jerk vilification. In such a context, the weight of “selfishness” is counter-normative and resistant. My approach to selfishness itself, then, is not value-judgment-laden in any straightforward way. The term is used descriptively, not prescriptively, though I will also suggest at moments throughout the book that it may be further strategically redeployed and that it should remain open to repurposing and expanding via my concept of “self-fulness.”

The data to be analyzed in the book include psychiatric, philosophical, political, literary, print and online media texts. A broadly cultural studies-informed methodological approach is used. However, for reasons already set out, the assumed left-wing bias of cultural studies methods (that have led latterly to paranoid alt-right accusations of a “cultural Marxism” issuing from the humanities departments of universities — and taking over broader culture[74] ) will not be a feature of my reading method or underpinning ideology. In an attempt to set aside the approximate and often unhelpful left-right dichotomy, I will interrogate both Marxian-influenced, class-based analyses, such as those produced by radical feminism, and pro-individualistic ideology, such as that produced by Rand and her followers, with the aim of breaking down the workings of the deployment of “selfishness” as rhetorical and moral marker. If this book has a political leaning at all, it is perhaps only an anti-authoritarian one that asks that we be open to reading all texts, and considering all ideas and taking them seriously on their own terms, rather than narrowing debate and analysis to a small number of “approved” views, ideologies, and texts. The book actively seeks out the words and ideas of prominent women commonly considered unpalatable and rebarbative and asks what they may contribute to debates about the meaning of “woman” and “self” in an epoch in which both are matters of urgency.

Over five chapters, via case studies from a range of European and Anglophone contexts and from different disciplines and discursive sites, the book explores how female selfishness has come to be constituted as aberrant, and how it is currently understood. The first chapter examines the historical construction of the pathological version of selfishness — “narcissism” — and its gendering, from Freudian psychoanalysis to late-twentieth-century American psychiatric and popular psychological accounts, paying particular attention to the figure of the “narcissistic mother,” which has entered everyday parlance.Chapters 2and3present case studies of two prominent selfish women who proudly claim individualism as a virtue or are strongly associated with having done so: inChapter 2,Ayn Rand, who declared that “there is no such entity as ‘society’, since society is only a number of individual men”[75] and, inChapter 3,Margaret Thatcher, who would take this very idea as central to her whole political message and agenda (without attributing it to Rand). In undertaking these case studies, I pay close critical attention to the specific ways in which discourses of selfishness, gender, and ideas about the political right wing intersect in the cultural imagination to create meanings and reinforce assumptions. The last two chapters of the book ask what gendered selfishness means currently, and has meant in modern times, for the lives of women.Chapter 4 considers the place of “self” in pervasive popular cultural and media narratives about women’s personal and professional lives. It explores the double standards and double binds involved in both motherhood and child-free life choices (both of which can, by misogynistic sleight of hand, carry implications of inappropriate female selfishness), and examines the imperative to care that is intensely gendered, by revisiting the literature of “ethics of care,” especially Carol Gilligan’s classic text, In a Different Voice (1982). It also interrogates discourses of female ambition and female leadership, which fail to conform to a specifically gendered expectation of self-sacrifice. Creative — but not necessarily feminist — selfish or self-ful forms of resistance to these gendered expectations are explored via the writings of controversial novelist and journalist Lionel Shriver. Finally,Chapter 5considers feminism’s fraught historical — and present — relationship with the idea of selfishness, self-interest, and individuality. It looks at branches and philosophies of feminism — radical, intersectional, and postfeminist — that each treat the self-other dynamic and the ethics that accrue to it in different ways. It examines the ways in which a feminist agenda might be seduced by, or resist, recent narratives of “empowerment,” and it asks if it is possible to articulate a vision of the feminist self — of feminist self-fulness — beyond the bounds of the freighted and over-simplistic dichotomy of collectivism and individualism.

In short, then, this book both explores how avowedly and vocally “selfish women” in history have viewed self, feminism, and, indeed, women, and examines the character of both feminist and mainstream cultural, political, and psychological discourses about women who refuse an ethical commitment to collectivism and to the other. The book is also interested in the rhetoric of “extremism” when it comes to women expressing strongly held opinions. Writing, speech giving, and discourse that are highly polemical and uncompromising often risk being dubbed totalitarian or fundamentalist when they are authored by subjects who are not supposed to express decided conviction. When women write this way, they tend to face criticism from men, for being “unfeminine,” and from feminists for being bad sisters. Along with Rand and Thatcher, radical feminist writing of the “second wave” shares this tendency, and is also often rejected by contemporary forms of feminism for being too doctrinaire and uncompromising.[76]

The book is aware of, and celebrates, the audacity of thinking about selfishness neutrally, or even in strategically positive terms, in an epoch in which the term is most often linked to global capitalism and punitive austerity policies, seen as the cause of increasing misery for the majority. Politically, selfishness]]is generally assumed to be of the right. Yet, I would argue, those considering themselves feminist and/or progressive might do well to understand and take more account of strategic self-interest rather than simply considering it, unquestioningly, as a moral evil.

1. The Psychopathology of Selfishness

On narcissism and norms of gender

The vices attributed to individualism by its critics are self-absorption, narcissism, unscrupulous competition, alienation, atomism, privatism, deviance, rationalization, worship of objectivity, relativism and nihilism.

(Alan Waterman, The Psychology of Individualism, 1984)

Much of our distress comes from a sense of disconnection. We have a narcissistic society where self-promotion and individuality seem to be essential, yet in our hearts that’s not what we want. We want to be part of a community, we want to be supported when we’re struggling, we want a sense of belonging. Being extraordinary is not a necessary component to being loved.

(Pat MacDonald, cited in The Guardian, 2 March 2016)

I think writers and artists are the most narcissistic people. I mustn’t say this, I like many of them.

(Sylvia Plath, interview with Peter Orr, 1962)

Narcissism is one of those terms that has both a lay meaning and a technical one. In everyday social discourse, narcissism has come to mean vanity, toxic selfobsession, egotism, and — most literally — excessive self-love. In the psy sciences its definition has evolved over time from Freud’s turn-of-the-century Vienna, where it is understood as a failure of mature, adult “object love” to its current manifestation as a “personality disorder” in twenty-first-century psychiatry. It is a fascinating and timely concept, as it is at once an individual diagnosis of pathology with a discrete clinical history, and yet also it has become a metaphorical descriptor of our modern and post-modern Western cultural Zeitgeist. Certain periods of European and North American history have been characterized as eras with an especially narcissistic character. These include the nineteenth-century]]fin de siecle, characterized by the rise of the modern individual and by Decadent solipsism, the “permissive” post-1960s era (with the 1970s being dubbed the “Me Decade”[77] ), and most recently, the decades characterized by what is often known as “neoliberalism,” an economic philosophy of free markets that has allegedly led, according to critics, to selfish, atomized, unhappy citizens who view themselves first as consumers and a generation of young people obsessed with image and surface. (Psychologist Oliver James and psychoanalyst Paul Verhaeghe have both written searing critiques of the effects of this worldview on the subjects living with it.[78] ) In 2000, psychoanalytic critic Jessica Benjamin stated that in our consumerist and celebrity-obsessed culture, “Narcissus has replaced Oedipus as the myth of our time.”[79] Yet, while there may be some validity to seeing narcissism as a description of the collective character of our culture, it is also the case that both diagnoses of individual narcissism as a pathological clinical entity and accusations of cultural narcissism as a more widespread phenomenon can reveal much about attitudes to gender in contemporary culture, since narcissism has a particularly gendered history.[80]

In this chapter, I will explore the history of the gendering of the clinical concept of narcissism in the psy sciences. My history will cover narcissism in the foundational texts and ideas of psychoanalysis that were produced in Europe at the turn of the century, in twentieth-century American ego-psychology (which both built on and deviated from psychoanalysis), and in the American Psychiatric Association’s diagnostic schema which first included “narcissistic personality disorder” in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in DSM III, published in 1980. I will also read the foundational text of psychoanalytic theory about narcissism, Sigmund Freud’s “On Narcissism: An Introduction” (1914), with and through historically contemporaneous literary portrayals of female “narcissism” by the French Decadent writer Rachilde (Marguerite Vallette-Eymery, 1860—1953). I will then contextualize later psychological and psychiatric theories of narcissism by reading them alongside social commentary about cultural narcissism in order to further our understanding of the process of subjectification of the gendered narcissistic subject. I mean this, of course, in the broadly Foucauldian sense of a “specified individual,”[81] who comes about, can be thought, and can think themselves only as a result of the meeting of particular historical epistemological disciplines and discourses. In this case, those discourses are clinical psychology and psychiatry, the rise of economic/philosophical ideologies of individualism, and the socially changing gender roles brought about by the women’s liberation movement and the branches of feminism which have followed on from it. I will conclude by making some broader points about the ways in which the conceptualization of specifically female narcissism may say as much about attitudes to women in modern Western culture, as about the so-called narcissistic women in question. I want to ask what notions of female narcissism reveal about the forms of female selfhood that are psychosocially allowed for. I also want to explore the extent to which narcissism really can be understandable as self-love or self-regard (the focus of this book), as distinct from their opposite — a compensation for damaged self-regard — since narcissism is a knotty concept that seems, according to those experts who write on it, to have as much to do with fragility as self-valuation, and to be far from a straightforward synonym for extreme selfishness or self-interest. Indeed, for Nathaniel Branden, the father of the modern self-esteem movement and Ayn Rand’s sometime intellectual heir, narcissism is not a manifestation of genuine self-worth — excessive or otherwise — but, rather, a counterfeit form of it.[82]

Freud’s female narcissist - a deviation from a myth