Lynn Saxon

Sex at Dusk

Lifting the Shiny Wrapping from Sex at Dawn

Chapter One: Darwinian Natural Selection

Geoff Parker and sperm competition

Chapter Two: The Birds and the Bees for Adults

Six hundred million years in a few pages

Direct and indirect benefits in female mate choice

Why are there still ‘loser’ males?

Extended sexual receptivity and concealed ovulation

Partible paternity in the Amazon

The false promise of promiscuity

Evolutionary History of Hunter-Gatherer Marriage Practices

Chapter Five: Parenting and Marriage

Chapter Six: Monogamy and Jealousy

Chapter Seven: The Way We Were?

Egalitarianism, the sexual division of labour, and the family

The (not so) mysterious disappearance of Margaret Power

Pair bonds made it all possible

Chapter Nine: Let’s Hear It for the Girls

(Though Mostly It’s Still About the Boys)

Copyright

Copyright © 2012 Lynn Saxon

All rights reserved.

ISBN-10: 1477697284

ISBN-13: 978-1477697283

eBook ISBN: 978-1-62345-417-3

Preface

In the summer of 2010 my attention was drawn to a new book titled Sex at Dawn by Christopher Ryan and Cacilda Jethá. Not evolutionary biologists (their interests are psychology and Ms Jethá is a practicing psychiatrist) the authors presented an attack on what they called the ‘standard narrative’ of evolutionary psychology. This ‘standard narrative’ argument, they say, is based upon false beliefs about how we lived as modern humans (from about 200,000 years ago), especially the ‘false’ belief that we lived in sexually monogamous nuclear families with varying degrees of deceitful extrapair sex.

Ryan and Jethá have presented an alternative argument: we are not naturally monogamous today so our ancestral breeding system must have been one of open multiple simultaneous sexual pairings. They argue that this would not have involved jealousy or deceit or any concern about known paternity but would have been based on sharing: because resources such as food would have been shared in our egalitarian ancestors, so would sex.

While evolutionary psychology is not my main concern, evolutionary biology is. I have read and debated on the evolution of sex and the sexes for many years. Sex is a topic that interests so many of us yet there are few who have any real understanding of the place of sex and the sexes in evolution. When I saw that many of the books referenced by Ryan and Jethá are also on my bookshelves I decided that this popular book deserved to be read so that I might understand how they had reached their conclusions about human sexuality.

The basic argument that we are not naturally sexually monogamous is reasonably sound – anyone involved in evolutionary biology today would not argue against that. (Apart from anything else, to be naturally completely sexually monogamous we would have to be mating for life with our first sexual partner.) But Ryan and Jethá go much further than an argument for serial monogamy or monogamy with some extra-pair sex, and present us as being naturally bonobo-like – bonobos, in their understanding, live in groups where everyone regularly and casually has sex with everyone else.

Reading their book I felt increasingly concerned that their argument was presented as being backed by scientific evidence. There were many blatant errors and false representations which readers were accepting as factual evidence.

The authors have put their book forward as a means to create debate, so here I present evidence which I believe fills in many of their omissions and corrects many of the distortions and errors of their argument. Readers are possibly only interested in human sexuality but without a better understanding of the evolutionary biology of sex it is too easy to imagine things about our species which would put us outside of evolution. We’re not. Even if we think people today are able to escape ‘nature’ to a greater or lesser degree, the ancestors we are talking about here, from the common ancestor with the other African apes up to our recent ancestors 10,000 years ago, were naturally evolving in natural environments.

There is still, of course, much to learn about ourselves and our evolution but it would be wrong not to provide people with a chance to understand the evidence so far, even if some of it takes a little work to grasp. I am in the first instance presenting a fuller and corrected picture of the ‘evidence’ put forward by Ryan and Jethá, and then adding other evidence which has been omitted. While I have included some thoughts and interpretations that are my own, my main intent is simply to get across better and more honest information.

This book is obviously primarily aimed at readers of Sex at Dawn. I have also tried to make the arguments of that book as clear as possible so that those who have not read it but are interested in the arguments may be able to follow my response – and understand why it is necessary.

Introduction

We are apes. We are animals. Humans – Homo sapiens – share a common ancestor with the other African apes: chimpanzee, bonobo, and gorilla. If we trace our ancestry back through time we find that at about five to seven million years ago our ancestor joins with the ancestor of the chimpanzee and the bonobo, and about seven to nine million years ago that common ancestor meets with that of the gorilla.

We cannot know for certain what this common gorilla/chimpanzee/bonobo/human ancestor was like. Was it like a modern gorilla with a male twice the size of the females which he guarded in his little breeding group? Or was it more like the chimpanzee and the bonobo with multimale/multifemale groups and where males and females were much closer in size? And six million years ago at the Pan/Homo split (chimpanzees and bonobos are Pan troglodytes and Pan paniscus respectively), what kind of ape was that common ancestor? We cannot know for sure.

Add to this the various hominin fossils on the line between that common human/chimpanzee/bonobo ancestor to the modern human and we still do not know for sure how the sizes of males and females differed or not through time, or what kinds of social and breeding groups they lived in en route to Homo sapiens. Yet we look to whatever evidence we can find to try to piece together an understanding of our ancestors, often in an attempt to understand more about ourselves today: more about our ‘true’ nature, whatever that might be. One aspect of this nature we particularly like to debate is our ‘natural’ sexual nature, and in the modern Western world especially this has become a pressing issue as infidelity and divorce and ‘sexual liberation’ and ‘sexual dysfunction’ have changed the world from the one our grandparents knew (or at least thought they did).

Sex – just what is it all about? Don’t other species just get on with it? What are ‘men’ and ‘women’ and the relationships between them? What about the differences and the conflicts and the jealousies and all the pain and disappointments we so easily cause each other?

In the West in the mid-20th century there was a view of marriage that the eager bride drags the reluctant groom up the aisle. She is believed to be happy to have secured her mate and to be keen to live in monogamous bliss. He is only there because this is his best opportunity for sex on tap; how likely he is to stay monogamous depends only on how many other sexual opportunities come his way. Marriage and ‘the wife’ are not presented as something he really wanted but something socially expected, and perhaps his only opportunity for sex when women’s sexual behaviour was largely constrained by social attitudes. Monogamous marriage was seen, as it often still is (including as noted by Ryan and Jethá, p. 2[1]), as something like a prison sentence for the man, and the wife is his ‘ball and chain’.

Then came the women’s movement of the sixties and seventies which seemed to offer something a bit different: sexually liberated women who were less keen on being virginal brides and more keen on being like the men; women seeking economic independence and sexual freedoms to lift them from being the ‘second sex’[2] and put them on a more equal par with the ‘first sex’ – men. Yet four decades later we still seem none the wiser about sex and relationships. Just what is standing in our way? If the natural world runs so smoothly why is it so hard for us? Just who are the baddies standing in the way of our natural freedom, happiness, and sexual satiation?

Ryan and Jethá[3] in Sex at Dawn (p. 2) state that there is good reason to believe that marriage is the beginning and end of a man’s sexual life. And though they say that women fare little better, this, they say, is because the wife is left spending her life apologizing for being just one woman! The middle of the book does tell us about the supposedly natural wild promiscuity of the female of the species but this is sandwiched between clear arguments for the greater need for, and greater acceptance of, extramarital sexual encounters for men.

It is hard to imagine that people have ever really believed that the male of the species is ‘naturally’ sexually monogamous. But he often does want a wife, and children he knows to be his. Most human cultures have allowed polygynous marriage – one man with more than one wife – and many have not come down too hard on male infidelity and promiscuity. But for women there has more often been a strict control of their sexual behaviour so that a man could be sure he was only raising his own children. Certain ‘unfortunate’ women and girls as sex workers, or casual affairs kept going by false promises, have provided the extramarital sexual outlet for men.

Ryan and Jethá’s argument is that before about 10,000 years ago sexual constraints did not exist, paternity was hardly an issue, and men and women engaged in fairly free and casual sexual activity. Surely, they argue, our inability to sustain sexually monogamous marriages even with the constraints enforced by laws and religions and moralizers proves that open promiscuity must have been how our ancestors lived.

While many people do still sustain happy and sexually monogamous relationships it is also true that there are many who do not. Is this a clear sign that sexual monogamy is not ‘natural’ and, as the authors argue, that we are really as promiscuous as Pan (chimpanzees and bonobos)? Just why is ‘sex’ such a problem and relationships in such apparent crisis? What does the ubiquitous sex industry tell us about ourselves? Where does this leave the nuclear family unit? Where does it leave children? Has there been some false story-telling about pair-bonding in our evolution which has been used to support a false argument for a natural nuclear family unit going way back to the dawn of humankind? Have we all really been duped?

Ryan and Jethá criticize what they call “the standard narrative of human social evolution”. This, they say (p. 7), is the evolutionary psychology argument which says that men and women assess each other’s mate value as a reproductive resource, form pair bonds, and then jealously guard the resources they have acquired in each other while each follows a self-interested reproductive strategy of sexual cheating. The argument they are attacking, then, with this extra-pair sexual cheating, is not one of sexual monogamy after all. They are arguing that our ancestors not only were not sexually monogamous, they were also not socially monogamous, i.e., there were no bonded reproductive mates to cheat on. By removing social monogamy they can eliminate the nasty ‘cheating’ side of human sexual behaviour.

If, they argue, we see our ancestors as fiercely egalitarian, sharing all resources, then there is no need for laying claims to a specific individual as a reproductive resource, and every reason to believe sex itself would have to be shared. And they say they have the evidence for this: evidence in our bodies, in the habits of the remaining relatively isolated societies, and in certain aspects of contemporary Western culture.

In the chapters that follow I will look at the evidence again. Don’t expect easy answers as life is always more complex than we imagine – just as we think we have found one answer, new questions are often opened up. Will we find casual sexual behaviour or is there something about the human ape that made that very improbable? Just what does go on in the sex lives of chimpanzees and bonobos – and just how casual and sexy is sex in those bonobos? What clues can hunter-gatherer tribes give us?

The human female, more than the female of any other species, has had her sexuality socially controlled. She has often only been able to access resources through a man, exchanging sexual/reproductive access to her body for her access to food, shelter, and protection. How far back might that go? Are Ryan and Jethá correct that this is only a result of the shift to settled, agricultural communities? Or do we have evidence for anything similar in foragers, and even the other apes?

Modern Homo sapiens, people much like ourselves, have been around for about 200,000 years. What sorts of lives did these forager ancestors live? If egalitarianism and food sharing was enforced in tribal living do we have reason to believe, as Ryan and Jethá argue, that something similar was enforced in sexual behaviour?

The widespread anthropological agreement – not just that of evolutionary psychology – is that our evolution involved pair-bonding with some polygynous males having more than one wife but most mated men monogamously paired. Obviously with a more or less equal ratio of males and females one man’s gain of an extra wife is another man’s loss. While women were more likely to be officially mated to only one male there was also some (probably relatively hidden) polyandrous (multiple male) mating by females. Though sex was not ‘shared’ within groups there may well have been varying degrees of extra-pair sexual liaisons and relatively easy divorce and serial monogamy; divorces were most likely often due to those extra-pair sexual liaisons becoming known or intolerable to a spouse.

The big question is: do we have any reason to believe that there was a pre-agricultural promiscuity where men and women mated, often casually and openly, with many others? Does the necessity of the sharing of food and other resources amongst a relatively small group lead to the logical conclusion that mates would be shared too? And if not then why not?

I believe the strongest evidence is that pair-bonding, mate-guarding, and male parental investment in (usually) his own biological offspring extends far back in our evolution, and that casual sex within a group would not and could not have been workable for Homo sapiens – it could not have evolved. A norm of multiple open simultaneous pairings by women as well as men, I will argue, did not exist. Agriculture certainly changed a lot for humans but it was a change in degree of traits that were already well established rather than a change in kind.

If we are going to talk about groups and resources and sharing we need to understand what it is we are talking about. It is straightforward to understand what is meant by food and protection as resources and why they might be shared, especially if it is reciprocal exchange of like for like. But what do we mean when we talk of sex as a resource that can be shared? Just what is this ‘resource’, and how much of ‘it’ is there, and is it something that is the same for both sexes and exchanged like for like?

While multiple females may share the same resource of DNA coming from the same male, females are not transferring their DNA into males during sex. There is no two-way sharing between the sexes in this sense. The resource that the female provides in terms of maternal input into a single offspring cannot be shared between males. So what is meant by sex as a resource that, like food, can be shared?

Darwin treated sexual selection differently from the survival aspects of natural selection because he saw that its effects were quite different from those connected to survival. We need to understand why sex is different. Is it a need like food? Organisms do not die from the lack of sex – but the future of their genes does. This future for the genes, as we’ll see, even turns out to override the survival needs of the organism itself.

In the West we emphasize recreation rather than procreation in connection to our sexual needs, though why this particular recreational activity should have such a powerful control over us is not fully appreciated. We seek and expect the physiological rewards, which is what we think it is about, yet we despair at the negative aspects that also spoil the party. If sex is fun why is such misery connected to it? Only by understanding the evolution of sex and the sexes will we understand why this is, and understand how ‘recreational’ sex is inextricably tied to procreation and reproductive success.

Sex at Dawn constantly reminded me of a line from the novel Nice Work by David Lodge (1988):

“Literature is mostly about having sex and not much about having children; life’s the other way round.”

Sex at Dawn is almost all about sex and not much about children, yet evolution is very much about reproduction – variation in reproductive success is evolution.

For most of our history girls would have been having their first sex soon after puberty and, though puberty likely was later than it is today, would have become mothers by the time they reached their twenties. Today we have the luxury of avoiding parenthood altogether or extending the pre-parenthood period of our lives well beyond what our ancestors, especially our female ancestors, experienced. Children are far less a part of our lives than they were in our past and this is especially true for women who no longer have an infant strapped to their body from their late teens. This surely impacts our sexual behaviour.

Ryan and Jethá simply say that all men in the group will all equally share the parenting of the offspring because it is for the good of the group, but group selection arguments have been almost totally dismissed in evolutionary biology and with good reason. The unit on which selection acts is the ‘gene’, and the ‘gene’s eye’ view has given us the best (and sometimes the only) way to understand what we observe across species. If behaviour is about helping a close relative then it is helping shared genes in another body which is kin selection. Beyond this there can also be reciprocal exchange where one person’s excess shared on one occasion will be paid back on another occasion. Joint ventures can also provide the best outcome for individuals, and when we understand that the joint venture of sexual reproduction is most often between ‘strangers’ who do not share genes to the extent that close kin share genes, we can gain some insight into the conflicts of interest that arise.

Genes cannot be selected that sacrifice their own continued existence so that different genes can continue instead; self-sacrificing genes have no future. Genes that are good at producing traits that get more copies of themselves into new individuals spread, those that are bad at it don’t. When the production of new individuals by females is limited (as it most often is), genes that produce traits in males that make those males good at ensuring their genes are in those offspring are going to be selected over the alternative genes and traits in other males that are less good. A genetic indifference about success at achieving paternity cannot be selected. We will come back to this later as it is important though not always easy to understand or accept, not least because of the confusion between ‘selfish genes’ and ‘selfish individuals’.

We also have to remember that the members of family and social groups are not all closely genetically related individuals but comprise both close genetic relatives and marital/sexual ones. In kinship terms this is the distinction between consanguine (blood) relatives and affinal (marital) relatives. Thinking of a group as a bounded entity through time (and therefore a unit on which selection can act) is a mistake because individuals move between groups, usually in order to breed with non-relatives, and it is this that creates the gene-flow throughout a species; separate, bounded groups without gene flow between them would ultimately evolve into separate species.

So we have to take into consideration the difference between blood relatives and those non-genetic (or less closely genetic, as most genes are shared within a species) relations between people due to marriage and sexual reproduction, and how the membership of a group, both in terms of individuals and of genes, constantly changes through time. The group as the entity on which natural selection acts – its descendants out-numbering those of other groups – does not work because individuals, and therefore any selected genes and selected traits, move between groups.

Some of the things we will be looking at may take a little effort to follow but they are important considerations if we are to avoid simplistic and faulty conclusions.

If we just look at this thing called ‘sex’ as being a need and a resource on a par with food which is being ‘unnaturally’ or antisocially restricted, then removing restrictions so that the resource of sex can be shared seems a straightforward solution. But when we understand what sex is we can understand why it is different from food.

If we are going to look at chimpanzees and bonobos for clues about ourselves then we have to know what is actually going on in chimpanzees and bonobos and not merely take a few observations that fit a particular agenda and ignore everything else.

If we are going to use evolutionary biology in our argument then we have to understand evolutionary biology and not merely dismiss some evolutionary psychology accounts.

And if we are going to talk about what has been naturally and sexually selected then we have to understand natural and sexual selection.

Ryan and Jethá’s argument fails on all of these counts and they have substituted one evolutionary psychology story with another that has even less evidential support.

So now let’s look at the evidence, fill in some gaps, and make some corrections.

Chapter One: Darwinian Natural Selection

While evolutionary psychology seeks to explain current human psychology and behaviour by appealing to how we supposedly spent some two hundred thousand years of pre-modern evolution, it should not be confused with the sciences of evolutionary biology and natural selection. Evolutionary psychology is focused on current, usually Western, human behaviours, and it tends to easily lose contact with the science of evolutionary biology after taking in a few simple generalizations about males and females and applying them to all kinds of weird and wonderful things. And this includes the evolutionary psychology story told in Sex at Dawn.

In order to get a better understanding of the possible evolutionary influences on human sexual behaviour we first need to get a better understanding of the evolution of sex itself. I will go into this in some detail in this and the next chapter as we travel alongside the criticisms and arguments presented in Sex at Dawn.

Ryan and Jethá (p. 27) say they accept that female sexual reticence and choosiness – the ‘coy’ or discriminating female as described by Darwin – is a key feature in the mating systems of many mammals but they believe that it is not particularly applicable to humans or to the primates most closely related to us. Ryan and Jethá see ‘the standard narrative’ evolutionary psychology as an incorrect application of natural selection to humans but their mockery of Darwin and natural selection in respect of human sexuality is not obviously distinguishable from an attack on natural selection itself.

The absence of anything much in the way of an explanation of general evolutionary theory in Sex at Dawn means that their evolutionary story only really begins with bonobos and chimpanzees, quickly leaping to modern humans from 200,000 years ago, and therefore comprises only the failure, in their view, of evolutionary theory. Though the authors may accept that evolutionary theory does apply to other species there is no indication that they understand why this is so, i.e., why evolutionary theory and especially natural selection are such powerful concepts.

If Darwinian natural selection is to be mocked with regard to humans then we should at least start with some understanding of it as it does apply to other species. We cannot make a special case for human evolution without understanding something of the evolutionary mechanisms that have been in action for hundreds of millions of years in all our ancestors through all that time. We cannot, as religions do, make a special case for humans simply because we want it to be so.

Darwin and natural selection

Charles Darwin was a Victorian gentleman and his views on the two sexes reflected those of his time and social position. His interest was not so much in people specifically as in the whole of evolution and how different species evolved from a common ancestor. His 1859 book On the Origin of Species is his theory of how evolution works via the mechanism of natural selection: traits spread in a population down through generations because they aid survival in particular environments better than the alternative traits. But this left Darwin with a problem: many males have traits that hinder rather than help their survival.

To deal with this problem Darwin then went on to write The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (first published in 1871) about sexual selection, explaining the competition between males for females and female choosiness. While most people at the time could accept male-male competition and the selection of traits for vigour and strength in males, female choice was not accepted and, floundering under the arguments, it would be a hundred years before active female mate choice would be taken seriously. The ‘coy’ female who passively accepts the winning male was as far as female sexual behaviour could be viewed to go for it to be acceptable, and even Darwin’s more active female choice of aesthetically pleasing traits in males was too much for his contemporaries to handle (Cronin 1991).

The recognition that females may actually choose to mate with more than one male would be a long time coming, and so it is not surprising that Darwin does not seem to have considered wilful polyandrous mating by females, though he certainly was aware of it. In some of the barnacle species he studied he noted that he found a number of dwarf males inside the female. Writing to his friend, Charles Lyell, he described how the female in two of the valves of her shell:

“…had two little pockets, in each of which she kept a little husband; I do not know of any other case where a female invariably has two husbands…”

Darwin described these males as little more than bags of spermatozoa, and he went on to discover other barnacles with as many as 14 miniature males in a single female, speculating that any one of them might fertilize the female’s eggs (Birkhead 2000).

Females of many species are now known to mate more often than is necessary for the fertilization of their eggs, and females will also mate with multiple males rather than choosing only the best male. Discovering why this is so is an interesting and important topic in evolutionary biology, not least because mating is actually quite a costly endeavour in the natural world. These costs include reduced time for foraging, energy used in finding a mate, increased risks of predation, risks of injury in competition and even during mating itself, and risks of disease transmission; as we will see, mating is often resisted by the egg producers (and sometimes by the sperm producers). If this female resistance has been selected against in a species then it requires an explanation as to why.

Natural selection is the mechanism by which evolution occurs due to certain traits being selected over their alternatives. Traits that better enable survival and reproduction in a particular environment are the ones that, on average, are passed on to more offspring. Darwin did not know about genes and it would be many decades before they were discovered as the carriers of the recipe for development, and recognized as the means by which inheritance of traits occurs.

Evolution is now defined as the change in the frequency of genes, or alleles to be more precise – alleles are the different versions of the same genes, such as those that produce the different variants of eye colour. Natural selection is a mechanism of evolution which is recognized as being in action when particular traits spread down through the generations because they provide survival and reproductive advantages over the alternative traits. Evolution can, and often does, occur without natural selection: the different proportions of genes for different eye colours, for example, may vary down through generations without there being any survival or reproductive advantage that is being directly selected.

Serving eggs, serving sperm

What would become the two sexes began with the evolution of two types of sex cell: males (almost always) produce vast numbers of tiny sperm and can (potentially) make vast numbers of offspring, while females produce fewer and larger eggs. In most species most of the available eggs will be fertilized and most sperm will fail to fertilize. Being an egg producer or a sperm producer is how female and male came into being and it is how the sexes are defined in biology.

However much we as humans argue about and redefine ‘gender’, in the evolution of sex the two distinct sex cell types remain a fact that has enormous consequences in natural selection: two different – and sometimes very different – naturally selected[4] outcomes are found within the same species. This is a basic fact about sexually reproducing species which cannot be ignored. For the male of most species the number of copies of his genes that he passes on is limited less by his sperm production than by the limited number of available eggs and females. These eggs and females do not treat all sperm, or males, as equally desirable, and we should also note that males do not necessarily find all females equally desirable either.

When we look at most species, especially those that are not monogamous (and strict sexual monogamy is rare), we see that males and females can easily be distinguished. This is known as sexual dimorphism. In some species it is far from obvious that males and females are even of the same species; this was the case with the mallard duck which the father of taxonomy, Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), first classified as different species (Andersson 1994).

In some species, such as those barnacles Darwin studied, males are reduced to packets of sperm and live on or in the female. In many species we have brightly coloured males and drab females, or males with horns or antlers, or males twice the size, or a fraction of the size, of females.

Why?

It is because selection has acted differently on the two sexes.

Why?

Because in sexual selection genes spread when an individual out-reproduces others of the same sex. Selection is acting differently on the two sexes even though they are of the same species with the same genome. The physical and behavioural differences that arise between the two sexes of the same species are differences that serve the reproductive interests of their respective sex cells. Males have their male-specific traits because those traits help genes that are in sperm get into more descendants, females have their female-specific traits because those traits help genes that are in eggs get into more descendants.

It is the variation between the male bodies and behaviours that sexual selection acts upon, and the same, separately, with variations between the female bodies and behaviours. Selection pressures can be quite different on the two sexes with regard to reproductive success so the two sexes, while sharing the same genome, diverge in the traits that they express.

In deep sea angler fish species, for example, only the female becomes a full adult; the male larva develops to become little more than sensory organs which are needed in order to find a female. If the male does encounter a female he then bites into her body and melds with it, reducing to little more than male gonads attached to her body. There can be multiple males attached to one female in this way, kept alive by the female and providing sperm for her eggs when needed (Andersson 1994).

Many marine species have reduced males like this but we are more used to thinking about mammals, and thinking of males as being bigger and stronger than females and physically battling for status and ultimately sexual access to females. Most species, though, have smaller males than females often because a bigger female produces more eggs while the male can produce his sperm cells and remain small.

Males produce sperm, females produce eggs, and so traits that lead to greater reproductive success among sperm producers get passed on to more male offspring than do alternative traits, and traits that lead to greater reproductive success among egg producers get passed on to more female offspring. To put it more correctly, the traits are expressed in one sex or the other, as both sexes carry the same genes.[5] With the evolution of two sexes, mechanisms such as sex hormones evolved to limit the expression of sexually selected traits to one sex, though this is not always fully achieved.

These basic facts about evolution, and especially about sexual selection, need to be grasped in order for us to make proper suggestions and hypotheses about the evolution of any sexually reproducing species past or present. Evolutionary psychology may well be mocked and ridiculed, as Ryan and Jethá do (and can themselves be), for presenting unsubstantiated assertions about human adaptations for one thing or another but natural selection and sexual selection cannot. There are arguments about the details, and arguments as to whether selection has in fact happened or whether it is chance or some other non-selective mechanism that has led to a particular trait, but the foundations of natural selection are sound.

For humans we are also faced with the difficulty of being objective about ourselves and without self-interested agendas, and culture of course is also clearly highly relevant. But if we accept that we have evolved and we are going to use natural selection to understand ourselves or our ancestors, as Ryan and Jethá say they are, we need to take the science of evolutionary biology seriously.

Ryan and Jethá are correct when they say we have learned a lot more about animal sexual behaviour since Darwin, but in mocking Darwin in this respect the authors have failed to acknowledge that he did at least see the existence and importance of female mate choice and held on to this belief in spite of much opposition. Darwin argued for an active female role in evolution beyond the passive one argued for by his contemporaries; as we shall see, a passive female role is also the outcome of Ryan and Jethá’s argument for casual female promiscuity.

Female mate choice was finally, in the 1970s, given the full attention Darwin would have wanted. (This was also a time in the West of an active and significant women’s movement which may well have some connection.) As well as looking at how female mate choice led to display ornaments in males, such as showy feathers and bright colours, it also became obvious that females were often mating with more males than (from previous thinking) they needed to or, it was believed, did.

Recognizing that females in many species are not essentially monogamous has been an immensely important breakthrough but ‘why’ still needs to be understood. To argue, as Ryan and Jethá ultimately do[6], that it is because females are like males and simply want and enjoy sex in much the same way as do males, is really not good enough. This argument emanates partly from the desire for sexual equality that relies upon revealing women to be the same as men when traditionally that could only be seen as raising the status of women. While we do struggle more to unveil ‘natural’ or unconstrained female sexuality than male sexuality it would nevertheless be a mistake – and no less sexist – to assume that the sexes are both essentially ‘male’.

We now need to delve more deeply and to look at some of the people and ideas associated with evolutionary biology that are (mostly) mocked and dismissed by Ryan and Jethá.

Angus Bateman

Back in 1948 geneticist Angus Bateman carried out some experiments on fruit flies which at the time helped to establish empirical support for the promiscuous male/choosy female dichotomy. His results from a series of experiments showed male fruit flies increasing their number of offspring by mating with more females, while the females could not increase their number of offspring by mating with more males. These experiments are now known not to be as clear-cut as previously thought. The full results show that females produced progeny fathered by more than one male (though not necessarily a result of female ‘choice’) and in most cases female offspring numbers did increase (though less so than that of some of the males) when females mated with more males.

The species used, Drosophila melanogaster, is now known to have females able to store sperm for 3-4 days whereas in other fruit fly species the females cannot store sperm and they need to mate more often (in D. pseudoobscura every few hours) to acquire enough. If Bateman’s experiments had been carried out with a different species of fruit fly or had gone on for longer than the three or four days they did, then females would have been seen to be keen to remate. It has also been discovered that the male fruit fly’s seminal fluid contains chemicals which act as an anti-aphrodisiac to delay the female’s interest in mating with other males (Birkhead 2000, Tang-Martinez and Brandt Ryder 2005).

Because males – and this applies to all species – can potentially fertilize the eggs of a number of different females whereas the females have a limited number of eggs, the variance in the numbers of offspring from males is often greater than the variance in offspring numbers in females. In the 64 experiments by Bateman, 21% of males failed to fertilize any eggs while only 4% of the females failed to produce young (Hrdy 1986), so this does show the greater variance in male reproductive success compared to female which, Bateman said, was what determined the greater eagerness of males to mate. The males who successfully compete to fertilize more of the available eggs will pass their genes on to larger numbers of offspring while those who fail in the competition will pass theirs to few or none.

Ryan and Jethá (p. 52) say only that Angus Bateman “wasn’t hesitant to extrapolate his findings concerning fruit fly behavior to humans” when Bateman wrote that natural selection encourages “an indiscriminating eagerness in the males and a discriminating passivity in the females.”

To put this in context Bateman actually wrote (note that gametes are the eggs and sperm):

“The primary feature of sexual selection is to be sure the fusion of gametes irrespective of their relative size, but the specialization into large immobile gamete and small mobile gametes produced in great excess (the primary sex difference), was a very early evolutionary step. One would therefore expect to find in all but a few very primitive organisms, and those in which monogamy combined with a sex ratio of unity eliminated all intra-sexual selection, that males would show greater intra-sexual selection than females. This would explain why in unisexual organisms there is always a combination of an indiscriminating eagerness in the males and a discriminating passivity in the females. Even in derived monogamous species (e.g., man) this sex difference might be expected to persist as a relic.” (Bateman 1948)

Not exactly the sexist eagerness by Bateman to apply his findings to humans that is suggested by Ryan and Jethá.

It is hardly going against evolutionary science to look for evolutionary principles that apply across species, including humans. Any non-religious, evolutionary based ‘special case’ for humans will still need to be supported by evidence for evolved mechanisms able to produce ‘special case’ human traits. Evolutionary biology has moved on a lot since Bateman but there continues to be much about his work that remains relevant, and Bateman’s principles are still debated and potentially useful as, for example, the title of one paper: “Don’t throw Bateman out with the bathwater” (Wade and Schuster 2005) suggests.

Bateman’s basic insight that the greater variance in the reproductive output of one sex compared to the other leads to a greater eagerness to mate by that sex still stands, only rather than it being just the males who have the greater variance we now know that in some species it is the females. The sex – male or female – which has the greater variance in numbers of offspring is the sex most eager to mate. In species where the sex roles are reversed and the females have the greater variance in numbers of offspring it is the females who are most eager to mate and the males who are the choosy sex, as happens, for example, in phalarope shorebirds (Reynolds, Colwell, and Cooke 1986) as we’ll see below, and pipefish (Jones, Walker, and Avise 2001).

Robert Trivers

This brings in another important aspect of reproduction besides the mating: parenting. It is often when one sex is busy parenting a brood while the other sex has the eggs or sperm available for fertilization that the differences in eagerness to mate exist. It was Robert Trivers who went on to show that it was parental investment rather than the sex of the individual that was the important factor. The sex with the largest parental investment is a limiting resource for which members of the other sex compete (Trivers1972).

So here we have the use of the word resource as it applies to sex and reproduction. Males and females are not offering the same resources in equal measure. When the male is the one with the greater parenting resource, such as in the sex role reversed phalarope species of shorebirds, the females are larger and more aggressive and compete for the males. A female can produce a clutch of eggs for one male, and while he is incubating those eggs she can produce a second clutch for another male and even a third and a fourth. The resource we are talking about – parental investment – is a reproductive resource. For most species there are never enough eggs or there is never enough female parenting capacity for the number of available sperm, and in the case of species such as phalaropes there is never enough male parenting capacity for the available numbers of females and their eggs.

When females are removed from the ‘mating market’, such as in mammals due to the conception, gestation, and milk provisioning that falls exclusively to the female, the ratio of reproductively available males to females, known as the operational sex ratio, is often male-biased: there are many more males seeking females for their eggs than females seeking males for their sperm. Females are not expected to vary much in their number of offspring (the variance between females in reproductive success, and therefore female-female competition, is unfortunately a much neglected area for study) while males can potentially succeed in fertilizing the eggs of many females – or none.

Geoff Parker and sperm competition

Then something else came from the new look at sexual selection in the 1970s. Geoff Parker studied dung flies and specifically male-male competition. He watched as males would mate with a female only to be forced off by another male who then mated and so on. Females were routinely mating with multiple males and Parker realized that competition between males could continue between the sperm from different males within the female. With this realization he laid the foundations for the study of sperm competition, though Parker was still concerned with the competition between males, and the females were still viewed as the passive ground on which male-male competition played out.

But then in bird studies in the 1980s socially monogamous females were discovered to be actively seeking matings with more than one male so female mate choice became of interest again, this time including ‘cryptic female choice’ where the choice is made internally between different sperm that are potentially from different males (Birkhead 2000).

The selfish gene

I’ll return to sperm competition later but another shift in our understanding of natural and sexual selection also took place from about the 1970s. This was a shift away from seeing selection acting for the benefit of the group or the species to acting for the benefit of the individual and then, sometimes at odds with the individual, more specifically for the benefit of the gene (Dawkins 1976).

Evolution, as already stated, is the change in gene frequencies, with genes that are better at getting themselves into more offspring spreading in subsequent generations. Of course, there is no conscious intention involved, just a logical outcome that genes get more copies of themselves into more offspring if they are producing traits that make them more successful than the alternatives at being reproduced. This means that the well-being of the group, or the species, is certainly not of ‘concern’ to the gene but neither, necessarily, is the long-term well-being of the individual body in which they currently reside.

Perhaps this is best illustrated by the Australian mouse-like marsupial antechinus in which the male has a single mating season of two weeks at the end of his short (11.5 months) life. When it comes to the mating season this little male stops eating and frantically seeks females for sex. His digestive system breaks down and his levels of corticosteroids (stress hormones) skyrocket and his immune system fails. By the end of two weeks he is emaciated, ulcerated, infested, and completely physiologically beat – and dead. All his energy and focus has been devoted to competing with other males, mating (if successful), and even mate-guarding females with copulations lasting up to 12 hours (Lee and Cockburn 1985, Zuk 2007).

For the antechinus, male-male competition has led to this frantic intensive mating period at the end of which he simply drops dead. Females may live and breed for another year or two; obviously such frantic sexual behaviour in a female mammal would leave her genes with no future. But for the male the genes for this behaviour have been selected because they did better at getting passed on than their alternatives. So much for the individual!

To a lesser degree males of many species have evolved bodies and behaviours that lead to a shorter life expectancy than the female of the species. Some receive injury to their bodies, sometimes fatal, in their competition for mates. Those with the bright and sometimes cumbersome ornaments are at greater risk of predation. Others are sometimes eaten by the female during mating: males in many species try to avoid this fate but at least one, the redback spider, intentionally flips his body into a position above the jaws of the female in order to be eaten during mating. Redback spider males only have about a one in five chance of finding a female and if she feeds on the male at the same time as mating she will mate for longer so the male is then able to transfer more sperm and fertilize more eggs. Somewhere in their ancestry a male had a trait for this behaviour, copulated longer, and left more offspring also with this trait so its frequency spread in subsequent generations (Andrade 1996).

Selection has also led to some mothers becoming food for their offspring as in some spiders (Elgar 2005). Birds sometimes kill their siblings (Edwards and Collopy 1983), as do some sharks before they are even born (Prager 2011). New genes and gene variants arise, and if the traits they produce lead to greater survival and reproductive success than alternative traits then they spread.

Though the actual consumption of the mother by some spiders is an extreme example of the costs to the individual in providing a future for their genes, we can also consider more general costs involved in the maternal care of offspring. Why should an individual put so much time and effort into the well-being of resource-hungry other individuals that come out of her body? Why evolve such costly-to-the-self behaviour? Parental behaviour is often seen as the epitome of selfless behaviour but this selfless, individually costly behaviour has been selected for by the success of ‘selfish genes’.

We tend to overlook how ‘selfish gene’ natural selection has acted to produce behaviours such as mothering. Often we simply admire maternal sacrifice as a given, ‘selfless’ behaviour rather than recognizing it for what it really is: behaviour that benefits the future of the genes while carrying a (sometimes heavy) cost for the individual that is the mother.

If genes produce traits that lead to more offspring carrying those genes than carry the alternatives then their numbers increase. There is no greater plan going on, no concern about the future, and no ultimate goal.

Sexual conflict

There is now one more aspect of sexual selection that has become increasingly visible: sexual conflict. The joint project of sexual reproduction often hides the existence of conflict between male and female, as if the fact that each sex needs the other in order to reproduce means that their reproductive interests must therefore converge. As it is usually the males who potentially have more to gain from any one act of copulation (fertilizing eggs with possibly no further costs) and more to lose from not mating (missing perhaps the only fertilization opportunity that is coming his way), males have been noted to evolve sexual ‘persistence’ traits and females, in response, to evolve ‘resistance’ traits.

In a more general sexual selection context we can see this in, for example, the ornaments that evolve to greater and greater flamboyance in the attempt to persuade a female to mate. But there are also traits that evolve in males to achieve matings or fertilizations that are more obviously circumventing female choice and can even actually harm the female’s lifetime reproductive fitness. Sexual conflict is basically the conflict between the sexes over if, when, and how often to mate because the two sexes often have different naturally selected optima in these respects because of the different reproductive fitness outcomes that result.

Earlier I mentioned the fruit fly semen containing a chemical that acts as an anti-aphrodisiac on the female. The semen also has chemicals that increase the egg production rate of the female, and others which have evolved to incapacitate the sperm of rival males. These chemicals have evolved in the male for his reproductive benefit and not that of the female: the ‘sperm competition’ chemicals are similar to spider venom, are toxic to the female and can reduce her lifespan (Birkhead 2000).

The male fruit fly’s reproductive interest in a female is only in that single reproductive event with that female, so her reduced lifespan is of no consequence to him for there will be no future joint reproductive endeavour. Being able to increase his reproductive output with that female, even if it harms her by reducing her future reproductive output (which would be with other males), does not harm his genes but benefits them. Those genes and traits have been selected in the male.

Experiments have been carried out with fruit flies where the females were stopped from co-evolving with males and therefore were prevented from evolving counter-measures against the toxicity of male semen evolving for male-male sperm competition. In these experiments males evolved with semen which was increasingly damaging to females (Rice 1996).

Then experiments were done where monogamy was enforced in fruit flies, and now that the reproductive interests of male and female converged on the same offspring and male sperm competition was removed, the semen became less and less damaging to the females. In addition to this, males also evolved to be less aggressive in their courtship, and reproductive output actually increased over what it had been with the sperm competition (Holland and Rice 1999, Pitnick et al. 2001).

Sexual selection involves competition between individuals of the same sex to gain a greater genetic proportional representation in the next generation. If the mate’s reproductive success is harmed in the process then selection will not necessarily immediately or completely be able to act to counter that harm. Only with lifetime sexual monogamy can the interests of both parents converge on the very same offspring and extend together for both the parents’ lifetimes so that what harms the reproductive fitness of one sex harms that of the other too and is therefore not selected.

When traits in one sex do harm the reproductive fitness of the other sex and there is then selection in that sex to counter at least some of that harm it is known as sexually antagonistic co-evolution. It is similar to the co-evolution of predators and prey, or parasites and hosts, and is often described as an ‘arms race’: an advantage to the male leads to selection on the female to counter that advantage which leads to selection on the male again and so on.

Perhaps it is not how we would prefer to think of sex, reproduction, and the relations between the sexes but evolution is about the differential success of different genes and the traits they produce, not something that exists to please us.

Hermaphrodites

We can even see sexual conflict in hermaphrodites. Most hermaphrodites are invertebrates such as slugs, worms, snails, and flatworms. They are producing both sperm and eggs so we might expect them to just pair up and exchange their sex cells with little fuss – surely no battle of the sexes here? Actually we can see it even more because the ‘male side’ wants to mate so the ‘female side’ cannot just get away.

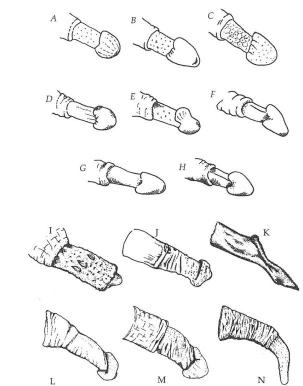

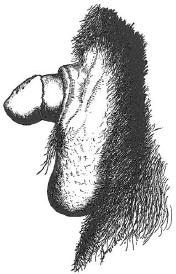

One of the most well-known conflicts in mating is in marine flatworms such as Pseudobiceros bedfordi (see overleaf) where the two individuals will ‘penis fence’ (P. bedfordi has two penises).

These duels can last for twenty minutes or more, each one trying to strike the other while avoiding being struck itself. A successful strike deposits sperm on the other which dissolves through the skin leaving it scarred. Flatworms have even been seen that have lost part of the body because the ejaculate has burned right through, though they are able to regenerate (Arnqvist and Rowe 2005).

(Photo: Nico Michiels)

Garden snails (also hermaphrodites) produce what has been called a ‘love dart’: a hard structure about 1cm or so in length and made of calcium carbonate. At the end of courtship a ‘love dart’ is sometimes forced into the body of the mate and then copulation proceeds. This dart introduces mucus into the mate which contains chemicals that make the reproductive system of the mate use the sperm for fertilization of eggs rather than digesting it as food; as little as 0.1% of delivered sperm escapes digestion if a darting has not been successfully achieved. ‘Love darts’ are not necessary for mating and are not always produced, and even when they are produced they fail to successfully reach their target more than 50% of the time (Rogers and Chase 2001, Arnqvist and Rowe 2005).

There are also a few fish that are hermaphrodites. In hamlet fish and harlequin bass, fertilization is external by spawning and each of the pair takes turns in releasing eggs and releasing sperm. Only a few eggs are released at a time and this is known as egg-trading. If all the eggs were released at once the mate could just release sperm and then leave without providing eggs for the other to fertilize. This egg-trading is what we would expect when, because more offspring can be produced via sperm than via eggs, the male role is the preferred sex role. These species are more likely to cheat by not providing eggs for fertilization because eggs are a more limited and costly resource to produce so they are choosier about releasing them for fertilization.

There are, though, species where the female role seems to be the preferred role. The sea slug Navanax inermis also takes turns at being ‘female’ and ‘male’, though in this case fertilization is internal and it is cheating on the provision of sperm which is more likely. In Navanax the individual that is most keen to mate provides sperm first, suggesting that it is the sperm that is the more valuable resource and is therefore used to encourage mating. In this species sperm can be stored and it can be digested, so the receiver has control over whether it is eventually used for fertilization or used as a food source (Leonard and Lukowiak 1991, Leonard 2005).

The production of sperm and the male role were thought automatically to be preferred because of the potentially high number of offspring that can be produced that way, but there is now more evidence and understanding for an advantage in producing eggs. In the female role there can be more control over fertilization and sometimes sperm is used as a food and digested. Egg producers also have more certainty of fertilization due to their limited availability compared to sperm, and sperm producers are always faced with the possibility of no fertilizations.

These hermaphrodites and fruit flies can seem a long way from humans, which indeed they are, but our understanding of many of these natural selection mechanisms can only first be obtained with species that can be observed over many generations in a laboratory (though we also need to consider the differences between laboratory conditions and natural populations). What happens in these species is due to natural selection and it shows how there often is natural conflict between the reproductive interests of the two sexes, or sex cells. It is basically a conflict over the control of fertilization, i.e., that most important of events in natural selection as it concerns the success or failure of genes to exist in the next generation.

Ryan and Jethá’s arguments about human sexuality are about a natural lack of conflict between the reproductive interests of the two sexes but they present that argument without even attempting to show any understanding of the discoveries about how sexual conflict does act in evolution. Readers of Sex at Dawn who have little or no previous understanding of evolution and natural selection are unlikely to question arguments about the evolution of human sexuality when only human evolution is addressed, albeit alongside some sparse information from other apes. But taking humans out of the whole of the evolutionary adventure to stand alone easily disconnects us from the rest of life, where we have come from, and all the evolutionary mechanisms that potentially apply, or have applied, to us. This, in effect, makes any such argument little different from any other origins myth, including religious ones.

It is relatively easy to understand why a male might be keen to mate with pretty much any fertile-looking female because selection has led to that being a successful strategy in the males of most species. When bodies have evolved to serve eggs things are a bit different, and female sexual motivation and strategies are often less obvious and more complex and therefore more difficult to elicit. When parenting is involved then selection acts differently again, and we are a species where parenting looms large.

Darwin did not know most of what we now do about sex but he did establish the basic understanding of natural selection and he brought to the fore the importance of sexual selection. We have come a long way from the promiscuous male and the ‘coy’ female but some, including the authors of Sex at Dawn, have been so struck by the fact that females in many species show something other than a monogamous passivity that they have become a little over excited and have sought to show female sexuality as being as indiscriminate as it can often be in the male.

We also tend to overlook male choosiness which also occurs in nature especially when males provide more than just sperm. Even if providing only sperm, males can be choosy in its allocation due to potential sperm depletion (Hardling, Gosden, and Aguilee 2008). Though sperm in terms of how much is potentially available to any one female from the many ready and willing males can be viewed as virtually unlimited, sperm production by any one male can be depleted. This is not something that the authors of Sex at Dawn deal with, preferring instead to give the impression that, at least in our pre-agricultural past, men naturally had an unlimited supply. And while Ryan and Jethá never directly mention male mate preferences there is much within their book that suggests that the human male, given the choice, would be focusing his sexual attention on young and fertile female bodies; this implicit male choosiness runs beneath their explicit argument that human females are naturally not choosy at all.

Darwin did not see a war between the sexes; he viewed species as having either an active male-male competition for a passive female receptivity or a male-male competitive display with active female aesthetic choice of some or other preferred male trait. Whatever cultures have done to shape or control human sexual behaviour, what the natural sexual behaviour of other species shows us (and we’ll be looking at it more) is that beneath the apparently cooperative reproductive endeavour there is invariably more unpleasantness than we would like to see connected to sex.

Whatever we may feel about the ‘unnaturalness’ of human marriage and monogamy, nature will not give us an alternative happy ending to the story of sex – there is in reality an unfortunate clash between what we might wish ‘natural’ sex to be and what it in fact is. When something is experienced as a natural and imperative pleasure it is hardly surprising that it leads to the creation of stories which depict some mythological natural world where sex is free and easy, the believers arguing that any constraints on their own pleasure must be due to ‘unnatural’ forces.

Women have rightly fought against the false representation of female sexuality as invariably passive, reluctant, and ‘coy’; it is women who have often been at the forefront of destroying this myth. Active female mate choice is a better representation of the reproductive self-interests of females and it will serve us well to understand the evolutionary biology behind the differences between the sexes. If females of some species evolve to mate more often than do females of other species then it is a valid question to ask why and to look at the different selection pressures experienced. A simplistic conclusion that females are just like males who just like sex does not fit with what we know about evolution and natural selection; it is as much male-biased thinking as anything produced by the Victorians.

When men latch onto the fact that women are not naturally monogamous we should not be surprised if some of them then pursue an agenda that encourages a belief that it is natural for females to simply want sex in the way men do. From the perspective of ‘selfish genes’ in male bodies there is an obvious benefit to be had from convincing multiple females that it is unnatural to refuse sex, perhaps not far removed from the young (and not so young) men trying to persuade their reluctant young girlfriends to have sex because it is ‘only natural’.

Regardless of evolutionary psychology, evolutionary biology is absolutely necessary for our understanding of the very real conflicts of interest that have evolved between the sexes, and the extent that the male will sometimes go to in order to access more of those eggs. In other species the males have no conscious awareness that their evolved behaviours are ultimately connected to accessing eggs and their own reproductive success; just because humans do know the connection between sexual behaviours and reproduction (and often deliberately avoid the latter) does not mean that sexual behaviours have dropped, or can drop, their evolved reproductive fitness baggage any more than a decision not to reproduce means we can drop sex.

The apparent removal of reproduction from the equation of sex does not equal the removal of the evolutionary history of ‘reproductive fitness’ selection for sexual behaviours in the two sexes. Perhaps we also ought to be especially cautious when the reproductive fitness baggage that is being argued should be dropped is only that of the female, leaving us all with just the male sexual promiscuity strategy (i.e., one giant piece of evolutionary fitness baggage carried by the male) for both sexes.

There was certainly a lot Darwin didn’t know and couldn’t know in his time but it would be wrong to come away from Sex at Dawn thinking that evolutionary biology has now discovered female sexuality and mate choice to be on a par with male sexuality and mate choice, or that sexual selection is unimportant or irrelevant with regard to sexual differences. Sexual selection, on the contrary, is turning out to be even more important and more relevant to our understanding of evolution.

Ryan and Jethá (p. 31) take great pleasure in mocking Darwin for using the voyage on the Beagle to study the bodies of other species rather than the bodies of the local young human females, saying, for example, that Darwin was too inhibited “to sample the dusky South Pacific pleasures that had inspired the sexually frustrated crew of The Bounty to mutiny”. Perhaps we should just take a moment to ponder what happened to some of those men whose mutiny was, no doubt, partly inspired by the attractions of living on a South Pacific island but mostly was due to the intolerably oppressive nature of The Bounty’s Captain Bligh.

In 1790 nine of the mutineers landed on Pitcairn Island with six male and twelve female Polynesians. That’s fifteen men and twelve women. When the colony was discovered eighteen years later there were ten of those women left but only one man (and numerous children). One of the men had committed suicide, one had died, and twelve had been murdered (Ridley 1994). After an initial peaceful four year period the community had fallen into turmoil – the disputes between the men over the women had resulted in the violent deaths of most of these men[7].

Darwin may well have been a buttoned-up Victorian gentleman but at least he laid the foundations for our understanding of natural and sexual selection – and therefore why it wasn’t ten men with one “dusky pleasure” left standing.

Thomas Malthus

Ryan and Jethá have a particular concern about Darwin’s use of the work of Thomas Malthus. Most of us would support an argument against the inevitability and acceptance of poverty and starvation in the modern world but as far as natural selection goes – and therefore Darwin’s use of Malthus – differential survival and differential reproduction are the mechanisms of evolutionary change.

For a sexually reproducing population to replace itself it needs only for each female to produce two offspring. So when we see flowers and trees and some animals such as oysters producing thousands, and sometimes millions, of offspring, and even mammals producing well above two per female, it is clear from actual numbers of adults that a minority of those born become parents themselves. Some become food for other species or die from infections or injuries or lack of resources, or simply fail to successfully reproduce. Some females produce fewer offspring than others because they get less or poorer quality food than the other females. As we’ll see later, getting access to more or better quality food is behind the evolution of social and sexual behaviours in female chimpanzees, bonobos, and humans.

Because all the individuals in a population vary and there are never enough resources to let numbers increase indefinitely (if at all) there is variation in successful access to those resources. Variants of traits that enable some to out-survive and out-reproduce others get passed on to more offspring in the next generation. Frequencies of the different gene variants change: evolution happens. Some variants will be better against parasites or against predators or prey, others may be better at exploiting a new resource or a new or changing environment.

This was what Darwin took from the writings of Malthus which provided the key to understanding evolution – differential survival and differential reproductive success amongst plants and animals. This is not a political argument but simply how evolution is; a fact. It does not exclude cooperation, at least between kin or for mutual benefit, but traits that are worse at fighting disease or avoiding predation or acquiring food or successfully reproducing compared to their alternatives are not going to be the ones that, on average, make it through. And it is important to note that just surviving is not enough: as far as evolution is concerned, genes in a successful survivor might as well be in one that was never born if they do not get passed to offspring.

Bodies and behaviours

Selected traits are both physical and behavioural; the two aspects are, after all, linked. Ryan and Jethá write that until E. O. Wilson wrote Sociobiology in 1975 evolutionary theory was only interested in how bodies came to be as they are. This is because they are again restricting themselves only to thinking about humans, and Sociobiology, though predominantly about the social behaviour of other animals, is the book that brought the inheritance of human social behaviour into the spotlight.

But animal behaviour had been an area of study for some time: ethologists such as Niko Tinbergen and Konrad Lorenz studied how animal behaviours evolved, and Darwin had also concerned himself with the natural selection of behaviours in his book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872). The human part of sociobiology became evolutionary psychology, but an interest in the natural selection of animal behaviour was not itself new.

Bodies and behaviours have both genetic and environmental input, and that includes human bodies and behaviours. Natural selection and sexual selection are robust theories with vast amounts of supporting evidence which needs to be incorporated into any theories we may wish to present about ourselves and our past. Reproductive behaviour is no trivial matter in evolution; neither, therefore, is sex.

So, can sex really have been, or become, no more than a casual pastime for any evolved species? Was it ever so for our ancestors?

Lewis Henry Morgan

Near the end of their CHAPTER TWO Ryan and Jethá (p. 42) attack evolutionary psychology for being founded on “the belief that male and female approaches to mating have intrinsically conflicted agendas” but they omit to say that evolutionary biology provides plenty of evidence for these conflicted agendas across species.

In opposition to Darwin’s sexual selection they introduce his contemporary Lewis Henry Morgan’s (1818-1881) hypothesis that promiscuity and group marriage simply had to be the original forms of our prehistoric social and breeding systems. Without providing any details of this hypothesis or any explanation as to why Morgan believed this to be so, Ryan and Jethá prefer instead to give the impression that Darwin himself was close to agreeing with Morgan.

They state earlier (p. 30): “If you’re a Darwin—basher looking for support, you’ll find little here”, so after knocking and mocking Darwin so much it is as if he then needs to be reinstated as a ‘great mind’ who was actually close to dropping sexual selection in favour of Morgan’s – and Ryan and Jethá’s – ideas on primitive human promiscuity.

To this end, this is how they order their quotes from Darwin:

Firstly, they write (p. 42) that Darwin believed “promiscuous intercourse in a state of nature [to be] extremely improbable.”

Then (pp. 43-44), influenced, they say, by Morgan, Darwin said that: “It seems certain that the habit of marriage has been gradually developed, and that almost promiscuous intercourse was once extremely common throughout the world.”

This (p. 44) is followed by their statement that Darwin agreed there were “present day tribes” where “all the men and women in the tribe are husbands and wives to each other.”

And lastly (p. 44) a quote from Darwin that: “Those who have most closely studied the subject, and whose judgement is worth much more than mine, believe that communal marriage was the original and universal form throughout the world… The indirect evidence in favour of this belief is extremely strong…”

It sounds, doesn’t it, like Darwin was swayed from thinking that Morgan’s ‘primitive promiscuity’ ideas were extremely improbable to coming close to being in agreement with him.

But to quote Darwin properly and in the correct order, he wrote (the third and then the fourth quotes above come first):

“Now it is asserted [note that Darwin is not agreeing] that there exist at the present day tribes which practise what Sir J. Lubbock by courtesy calls communal marriages; that is, all the men and women in the tribe are husbands and wives to one another…it seems to me that more evidence is requisite, before we fully admit that their intercourse is in any case promiscuous. Nevertheless all those who have most closely studied the subject…and whose judgment is worth much more than mine, believe that communal marriage (this expression being variously guarded) was the original and universal form throughout the world, including therein the intermarriage of brothers and sisters…”

Darwin then goes on to write:

“The indirect evidence in favour of the belief of the former prevalence of communal marriages is strong, [I cannot find any version that says “extremely” strong as Ryan and Jethá write] and rests chiefly on the terms of relationship which are employed between the members of the same tribe…” (my emphasis).

Then Darwin considers the influence of these “terms of relationship” on the ideas about communal marriage:

“The terms of relationship used in different parts of the world may be divided…into two great classes, the classificatory and descriptive, the latter being employed by us. It is the classificatory system which so strongly leads to the belief that communal and other extremely loose forms of marriage were originally universal. But as far as I can see, there is no necessity on this ground for believing in absolutely promiscuous intercourse; and I am glad to find that this is Sir J. Lubbock’s view. Men and women, like many of the lower animals, might formerly have entered into strict though temporary unions for each birth, and in this case nearly as much confusion would have arisen in the terms of relationship as in the case of promiscuous intercourse. As far as sexual selection is concerned, all that is required is that choice should be exerted before the parents unite, and it signifies little whether the unions last for life or only for a season.”

Now we get to the quote which Ryan and Jethá put second above:

“Although the manner of development of the marriage tie is an obscure subject…it seems probable…that the habit of marriage, in any strict sense of the word, has been gradually developed; and that almost promiscuous or very loose intercourse was once extremely common throughout the world.”

Going on to write:

“Nevertheless, from the strength of the feeling of jealousy all through the animal kingdom, as well as from the analogy of the lower animals, more particularly of those which come nearest to man, I cannot believe that absolutely promiscuous intercourse prevailed in times past, shortly before man attained to his present rank in the zoological scale.”

And finally his conclusion from which Ryan and Jethá took their first quote:

“We may indeed conclude from what we know of the jealousy of all male quadrupeds, armed, as many of them are, with special weapons for battling with their rivals, that promiscuous intercourse in a state of nature is extremely improbable. The pairing may not last for life, but only for each birth; yet if the males which are the strongest and best able to defend or otherwise assist their females and young, were to select the more attractive females, this would suffice for sexual selection”. (Darwin 1871 Chapter XX)

With the quotes in the right order and expanded and corrected it becomes clearer that, while Darwin did give some consideration to the possibility of promiscuous sex, his own understanding of sexual selection and his knowledge of other species made him believe it was extremely improbable.

Most importantly, what Ryan and Jethá omit is the consideration Darwin gives to the classificatory system used by tribes when a father’s brothers and male cousins will also be called ‘father’, leading to the belief by outsiders that any one of these men may be the actual father. We use a descriptive system where ‘father’ and ‘mother’ etc. are used for a specific person rather than a class of people, though we might also use these terms in other contexts such as ‘father’ for priests, godfathers, and ‘Father’ Christmas etc. without presuming some biological parentage.

Lewis Henry Morgan could not imagine anything other than promiscuous mating preceding the origins of the family, including sexual relations between brothers and sisters which for him would be an inevitable consequence of promiscuous group marriage (something Ryan and Jethá don’t acknowledge at all). This he based on what he saw among the Hawaiians who used the same term ‘father’ to refer to the father, the father’s brothers, and the father’s cousins. Morgan reasoned that it must mean that all these men in the past were potential fathers, and, together with the use of other such kin terms, he further reasoned that these terms must be survivals of group marriage (Chapais 2008).