Second edition, Chiang Mai, Silkworm Books, 1999. <michaelvickery.org/vickery1999cambodia.pdf>

Michael Vickery

Cambodia 1975-1982

Introduction to the 1999 Imprint

Chapter Two: Problems of Sources and Evidence

Refugees, The Sources for Recent History

Democratic Kampuchea, Themes and Variations

The Kratie Special Region, Damban 505

Themes and Variations, Some General Conclusions

Democratic Kampuchea, a Non-standard Total View

Politics in Democratic Kampuchea

Medicine in Democratic Kampuchea

Chapter Four: Kampuchea, From Democratic to People's Republic

Salvation Front—people’s Republic

Historical background and genesis

The Current Situation (1981-82)

Chapter Five: The Nature of the Cambodian Revolution

[Front Matter]

[Title Page]

CAMBODIA

1975-1982

MICHAEL VICKERY

SILKWORM BOOKS

[Copyright]

© 1984 by Michael Vickery

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise,

without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

ISBN 974-7100-81-9

This edition is published in 1999 by

Silkworm Books

Suriwong Book Centre Building, 54/1 Sridonchai Road, Chiang Mai 50100, Thailand

E-mail: silkworm@pobox.com

Website: www.silkwormbooks.com

Cover design by Trasvin Jittidejarak

Cover photograph: Khmer Rouge camp in 1976, courtesy of Phnom Penh Post Archives

Set in 10 pt. Garamond by Silk Type

Printed in Thailand by O.S. Printing House, Bangkok

Introduction to the 1999 Imprint

Perhaps the republication of a book like this without changes requires some explanation. The short answers are (1) no changes are required, and (2) there has been a continuing demand for it. Had the publisher’s and my own schedules permitted I would have added numerous footnotes for points which may not be sufficiently clear to non-specialist readers, and introduced some new material which would have contributed to the discussion, especially in chapter 5 on the nature of the Cambodian Revolution, but nothing has been revealed since I wrote it which seriously undercuts the arguments made in the original text.

In spite of its first publication by a small and controversial publisher which was unable even to buy advertising space in the mainstream press, and the refusal of that press, with one or two exceptions, to review it, the first printing of three thousand sold very quickly, and a second printing also went within a few years. Since 1991, at least, the book has been virtually unavailable except through direct orders to the publishers who still hold a few copies, or when I pirated it myself in photocopy for aquaintances..

Had I been more of a capitalist entrepreneur I would have made a few hundred copies to sell in Phnom Penh at the time of the UN intervention with its election in 1991-1993, for the demand was enhanced not only by word of mouth but by the apparently surprising circumstance that several of the international organizations involved in that intervention recommended the book as an introduction to contemporary Cambodia for their employees. “Apparently surprising,” because I had been criticized for relativizing the “genocidal Pol Pot regime.” That assessment was accurate enough, because I did not, and still do not, consider “genocide” to be an accurate term for the radical social and economic experiments in which Cambodia’s first generation of revolutionaries indulged, and because the effects of those radical policies differed widely over time and in different regions. I considered, and still do, that the total picture of Democratic Kampuchea (dk), the official name of the so-called “Khmer Rouge regime,” required a historical treatment as though viewed from a distance, in the manner in which the horrors of the Thirty-Years War (1618-1648) or the Napoleonic wars are studied by historians.

As was written in the first scholarly treatment of the “Khmer Rouge,” “we are going to claim that the events in Cambodia justify a rational type of analysis, like that applied in quite different situations.”[1]

By the time UNTAC (United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia) arrived in Cambodia in 1992, however, relativization of “Khmer Rouge horrors” was at the top of the agenda. The Paris Agreement of 1991 had bounced the “Partie of Democratic Kampuchea,” that is, the “Khmer Rouge,” back into international respectability, if that had not already been acomplished by the US-Chinese pressure to form the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea (cgdk) in 1982. That bastard child of Great Power Cold War diplomacy forced the royalists and the non-royalist anticommunists into an unviable union with the surviving military and administration of Democratic Kampuchea—a coalition of contras, cynically termed “the Resistance”—for the purpose of overthrowing the new government in Phnom Penh, simply because that government had allegedly been created by Vietnam and was developing with aid from Vietnam, the Soviet Bloc, and Cuba.

Throughout the 1980s and early ’90s a member of the real dk occupied Cambodia’s UN seat in the name of the CGDK. They were fully represented in the Supreme National Council, created to represent the Cambodian state under UNTAC, and “genocide” was a forbidden word in official UNTAC discourse. When in November 1992 the UNTAC Human Rights Component organized a colloquium on human rights questions in Cambodia Ben Kiernan was prevented from distributing literature critical of DK, and both he and I were forbidden entrance to the discussions. Human rights issues then meant accusations against the Phnom Penh government and its Cambodian People’s Party, not what had happened in 1975—1979.

This is why there was enthusiasm for Cambodia. 1975—1982 in UNTAC, while my second book on revolutionary Cambodia, Kampuchea: Politics, Economics, and Society, published in 1986, was never mentioned by, nor even known to, the newcomers who arrived with UNTAC. The transparent reason was that it was a sympathetic treatment of the post-1979 People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK)/State of Cambodia (soc) whose close relations with Vietnam, the bete noire of those countries dominant within UNTAC, made it a pariah regime, the removal of which was the transparent, if unavowed, goal of the 1993 election which untac was formed to stage manage.

Chapter 4 of Cambodia 1975—1982 was also supportive of the PRK, but, ending in 1982, its position could still be seen as tentative.

If the suppression of “genocide” from UNTAC discourse seemed perverse then, it has since been revealed as thoroughly dishonest, for the only indubitable evidence of a dk genocidal policy was discovered by untac intelligence in 1992—1993 and concerned dk policy then, not in 1975—1979. In interviews with defecting DK soldiers, UNTAC’s Cambodia specialists discovered that in late 1992 the DK leadership decided to target any and all Vietnamese, men, women, and children, for assassination. This was apparently covered up by untac authorities and was not revealed until 1996.[2]

Genocide, if the term is at all accurate, was also clearest with respect to Vietnamese in 1975—1979, but by 1975 there were too few Vietnamese left in Cambodia to give quantitative support to a genocide argument; and in any case, killing of Vietnamese was not of great interest to most of the international anti-DK community in those years, as was clearly shown when they switched in 1979 to support for the dk in further violence against Vietnam and a Cambodian state close to Vietnam. Killing Vietnamese was what Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman once called a “benign bloodbath.”[3]

Along with my implied criticism here of Heder’s treatment of the UNTAC silence on the new genocidal policy of dk in 1992—1993, I must note approvingly his support for relativization in general of the dk revolution. In an emotional plea for understanding Heder wrote that his encounter with the former dk soldiers in 1992-1993 “left this author [Heder] and other interviewers with a strong sense of the extent to which NADK [National Army of Democratic Kampuchea] combatants are ordinary Cambodians who are no less human than those who are found in the ranks of other political organizations or struggling to survive in the paddy fields, forests, cities, and towns of the nation. The interviews provided a demythologized picture of rank-and-file “Khmer Rouge. ’ some of whom were a danger to society as individuals; but the vast majority of whom were probably not. Discussion with them and with villagers in the areas from which they came also revealed the extent to which most individual NADK combatants, like their [Cambodian government] counterparts, were members of the local community who were not necessarily seen as particularly evil by those who knew them personally.”

Here is an eloquent answer to those who have fantasies of international tribunals pursuing former Khmer Rouge cadres down to village level— something which could ignite intra-village conflict and mini rebellions all over the country where surviving Khmer Rouge are integrated into their old communities. Then the steady, if very gradual, increase in peace and security in ever wider areas of the countryside resulting from the defeat of the contras in July 1997 might be reversed. Such an outcome, however, may be an unavowed, perhaps even not fully conscious, objective of those calling for a purge of ex-KR, for what infuriates them is the prospect of recovery under the People’s Party and Prime Minister Hun Sen.

Perhaps, however, the untac enthusiasm for Cambodia. 1975—1982 was an illusion. What they really meant was another book entitled Cambodia 1975— 1978. If so, it might nevertheless be seen as an even greater testimony to the success of my book, if such success may be measured by its imitators.

The latter work, edited by Karl D. Jackson and published in 1989, not only mimicked my title, but was designed as a sort of mirror image of Cambodia 1975—1982, with an introduction and seven of nine chapters written by four members of the US Foreign Service (Jackson, Timothy Carney, Charles Twining, and Kenneth Quinn).[4] It covers very much of the same material, with little difference in treatment of fact, but with a different “spin” on the details and interpretation. Surprisingly, given the different preconceptions and objectives of the authors, there was no attempt to criticize my work, which is mentioned in only two footnotes, both concerned with one of the most sensitive points in my book, the level of demographic disaster during the dk period.

In the first footnote to his introduction, p. 3, Jackson, after his estimates, wrote, “For a radically different assessment see Vickery 1984 [Cambodia 1975—1982].” This reflects the “spin” of Cambodia 1975—1978. My assessments to which Jackson referred were not all “radically different,” and where they were, they were rather well supported. I accepted roughly a halfmillion “war-related deaths before the Khmer Rouge victory,” not radically different from Jackson’s six to seven hundred thousand. But against his “less than 6 million” and “5.8 million survivors” for “the waning days of 1978” and “at the beginning of 1979,” I had proposed 6.5—6.7 million at that time, supported by late 1980 UN and fao estimates of 6 and 6.5 million people within Cambodia, not counting another half million or so in border camps and refugee centers. Jackon’s figures were apparently based on “most journalists estimated the total population at 5—6 million at the beginning of 1979,” a peculiar cover for writers pretending to be both scholars and Cambodia specialists, especially since the journalists concerned often got their information from Jackson’s collaborators, if they had any real sources at all.

In another context on the same subject, Carney (p. 86, note 8) cited my work as “others argue that estimates of deaths” were overstated, but added merely that “the question warrants a careful, nonpartisan study,” refusing thus to attempt criticism of my estimate of less than one million deaths over a normal peacetime death rate during 1975—1979.

The Cambodia 1975—1978 imitators opted out of another chance to engage m critical discussion of their “other,” to use a now trendy post-modernist term, when, Carney (p. 33, note 20) cited some “critical” and “sympathetic” treatments of the “Pol Pot regime,” and “works of authors with greater background or better judgement in Cambodian affairs.” The first were William Shawcross and Jean Lacouture, the second Gareth Porter, George Hildebrand and Laura Summers; and the last Francois Ponchaud and David Chandler.

Cambodia 1975—1978, like Cambodia 1975—1982, concluded with a discussion of what I called, in chapter 5, “The Nature of the Cambodian Revolution,” a treatment of its local precursors, comparison with other revolutionary situations, and a tentative sketch of possible intellectual historical backgrounds of dk ideology. Here also there is a mirror image quality in the last chapters by Quinn and Jackson, including some reverse intellectual history, less an explanation of sources contributing to dk ideology than an attempt to discredit the precursors via the disasters attributed to dk.

This is particularly the case in Jackson’s “Intellectual Origins of the Khmer Rouge,” where he abusively brings in Franz Fanon as a major influence on those Khmer Rouge intellectuals who had studied in France (also in pp. 73— 74 of Jackson’s earlier chapter, “The Ideology of Total Revolution”). The details of Fanon’s biography show that it is nearly impossible that those Cambodians ever met Fanon, and if they did, in the 1950s when they were in France, Fanon was then intent on becoming a doctor, not yet propagating revolution. Moreover, the only work of Fanon cited by Jackson, The Wretched of the Earth, did not appear until the early 1960s, when the future dk leaders were fully immersed in Cambodian politics; those who wrote never referred to Fanon, and it is quite unlikely that they would have been interested in anything deriving from African experience.[5]

It is in that part of my own work that I overlooked an interesting parallel, although citing it is the sort of reverse intellectual history evoked above. On one of my trips to Cambodia in the mid-1980s I met a Chilean engineer who had fled Pinochet’s regime, worked with the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, and then came to Cambodia. He had read Cambodia 1975—1982 and his first comment to me was that DK, as seen through my book, was “pure Illichism.” Until then I had paid no attention to the writing of Ivan Illich, but he was well known among the Latin American left, and his books Deschooling Society and Medical Nemesis: The Expropriation of Health do suggest the same radical restructuring of society as envisaged by the DK intellectuals.

The experience of working with Illich related by some of the participants in the language schools which he founded in Mexico suggests to me that he might not have been entirely serious in those two books, but rather wrote as a super-trendy radical of the time, out to epater les bourgeois. In any case Illich did not imagine, nor intend, that his prescriptions would result in the type of violent change seen in DK.

The subsequent trajectory of Regis Debray, whom I did discuss, suggests a similar pose. From a prophet of very radical revolution he became in the 1980s a French government representative sent to persuade Australia not to oppose French nuclear tests in the Pacific. At least Debray, in his radical phase, became engaged in the practice of his theories to the extent of putting his life on the line.

It is even less likely than with respect to Fanon that the DK intellectuals had ever heard of Ivan Illich, let alone taken him as a guide. Nor, to the extent that some of their projects paralleled his, did they foresee, any more than he, much less desire, the tragedies which ensued.

They believed, perhaps along with Illich in terms of simplifying education and medicine, and adapting them to the needs of a poor rural society, more certainly along with Debray in terms of submersion in the demands of that rural society as they saw them, that they would eliminate the enormous inequities which they saw ravaging Cambodian society, and develop a simple, healthy, and eventually prosperous country of equal citizens.

Whatever the possibilities of such a transformation in the most favorable circumstances, and the DK leaders, along with Illich and Debray, were probably mistaken in their presuppositions, they began their experiments in the worst circumstances, just after a war which had killed hundreds of thousands, destroyed much of the country, and transformed the irritating inequalities of peacetime Cambodia into violent class hatred of one part of the population for the other. They then added to their difficulties by appropriating and intensifying an ideological trait, not of their favored rural society, but of the urban petty-bourgeois milieu from which they had sprung, and which had been utilized by all previous elite regimes when chauvinistic fervor was found necessary to turn attention from internal problems. This was the suspicion, fear, and violent hatred of Vietnam and Vietnamese which led DK to its worst excesses, and just like Lon Nol’s Khmer Republic, to a hopeless war with a much stronger neighbor who could have provided valuable help for a different sort of DK.

This was the real tragedy of recent Cambodian history. The DK leadership, like earlier Cambodian nationalists, went “full circle: radical student - active guerilla fighter and revolutionary - anti-Vietnamese nationalist - finally offering support to the U.S. against revolution in Indochina,” and from 1979 to 1993 against peaceful rehabilitation of their own country.[6]

In offering this book again, with its critique of a journalistic Standard Total View (stv) of DK Cambodia, I would like to direct attention to a new, and even more aberrant because of the greater available information, STV, which needs to be addressed now in view of the projects for another international intervention, in the form of tribunals to try the “Khmer Rouge” tailored to the requirements of the United States or China or other international actors, not to the requirements of a fragile Cambodian society which is in the process of reconstruction.

The authors of the new STV repeat endlessly the mantra of “Strongman” Hun Sen who organized a “bloody coup” in July 1997 to eliminate his royalist opponents, when most of those authors, and most diplomats in Phnom Penh, realize that what happened was quite different, although only Tony Kevin, a former Australian ambassador who was then present in Phnom Penh, has been willing to publicly offer a different interpretation.[7]

The new stv also emphasizes “impunity” of the authorities, corruption, political, business, and society murders, as though those were specifically Cambodian defects, and the fault of the regime filled, in the terms of the STV, with “former Khmer Rouge,” when even casual perusal of the Thai press would show that with respect to those matters Cambodia is now no worse than its western neighbor which has always enjoyed favorable treatment, and was even qualified as a democratic member of the “Free World” during the forty or so years when it was run by military thugs. It is time to apply the same standards to Cambodia and the rest of Southeast Asia.

Presenting this book again may also stimulate the new generation of Cambodia specialists to continue and deepen research into the DK period as an interesting historical subject in itself, not just in a search for condemnation. The sources available when I wrote Cambodia 1975—1982 were minimal, mostly the oral accounts of recent refugees. Now the Cambodia Documentation Center in Phnom Penh and its former parent organization in the Yale Genocide Project possess thousands of documents from the DK period which may serve to fill out the history of DK society, economy, and administration, if they are used for that purpose, and not only for a narrow focus on condemnation of the DK leadership. So far as I know only one person has started that type of anthropological history, but material is available to keep many busy for years. Cambodia should be studied as an interesting variation among the many paths engaged by the formerly colonized Third World after independence, not condemned as a unique aberration.

Preface and Acknowledgments

This book is intended as a contribution to the history of Cambodia between April 1975 and 1982—the period of Democratic Kampuchea (the so-called “Pol Pot Regime”) from April 1975 to January 1979 and the first three years of the succeeding People’s Republic of Kampuchea (“Heng Samrin Regime”). The formulation “contribution to the history of Cambodia” has been chosen with all deliberation. I do not claim to have written the history of Cambodia, nor even a history of Cambodia for the period in question, primarily, as is explained in chapter 2, because the sources used are too incomplete and unrepresentative of the Cambodia population as a whole. Those sources merit the attention given them, but entire areas of information essential for the history of Cambodia remain untouched by them and cannot yet be studied adequately from other sources either.

If the form and emphasis of the book are determined in part by the sources used, they also depend in some measure on my own experiences of Cambodia, which began in 1960.

I first arrived in Cambodia in July I960 to begin work as an English language teacher in local high schools under one of the United States government aid programs to that country. In that capacity I spent nearly four years in Cambodia, the first two in Kompong Thom, the a year in Siemreap, and a fourth academic year in Phnom Penh, cut short in march 1964 as a result of Sihanouk’s termination of all United States aid projects.

During that time I acquired fluency in Khmer, began studying, through examination of old newspaper files and conversations with friends, the post-1945 political history of Cambodia and decided to make the country the main focus of academic research which I intended to undertake.

In March 1964 I was transferred to a similar position in Vientiane, Laos, where I remained for three more years and during which I was able to make regular extended visits to Cambodia.

Then, after spending three years (1967-70) at Yale University, I returned to Cambodia in late 1970 for nearly two years of dissertation research there and in Thailand; and except for one more brief visit in 1974 I was then cut off from direct contact with the country until 1981, when I was able to travel there for three weeks.

Although my original interest in Cambodia was in the contemporary period, I kept pushing further back into the country’s history until I produced a dissertation and other writings on the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries, something which occupied most of my research time from 1970 through 1977; and after 1973 I virtually ceased collecting or organizing material on the contemporary situation.

The turn taken by the revolution after April 1975 surprised me as it did nearly everyone else, but I found the first wave of atrocity stories over the next year suspect and felt that given the squalid record of my own country in Indochina, Americans who could not view the new developments with at least qualified optimism should shut up.

Until early 1980 I did not try to follow information about Democratic Kampuchea systematically. Besides the newspapers readily available in Penang, where I worked from 1973 to 1979, in Bangkok, and from late 1979 in Canberra, I read no more than Francois Ponchaud’s Cambodia Year Zero, Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman’s After the Cataclysm: Postwar Indochina and the Reconstruction of Imperial Ideology, to which I contributed impressions of a visit to a refugee camp in 1976, and a pre-publication draft of Ben Kiernan’s “Conflict in the Kampuchea Communist Movement.”

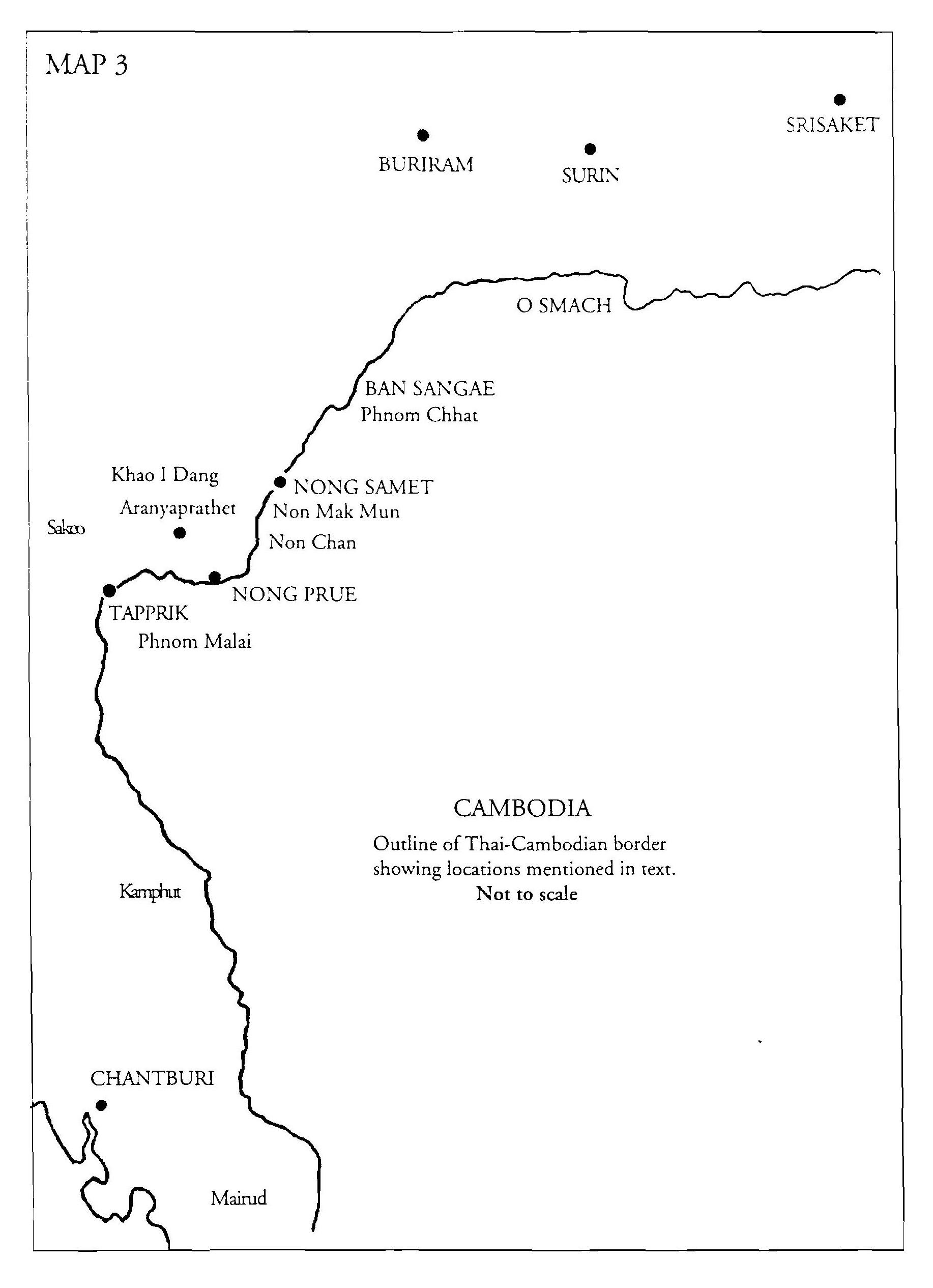

In February 1980 I receive word from a family whom I had known well that all twenty persons survived and were in the Khao I Dang refugee center in Thailand. Because of that news I went to Thailand in April, and during most of the next few months, until the end of September, worked for the International Rescue Committee’s educational program in the Khao I Dang and Sakeo camps, where I tried to collect information about life in Cambodia since 1975.

It was soon apparent that the refugees had a wide variety of experiences to report, that conditions in Cambodia during 1975—79 had differed significantly according to place and time, and that some of my doubts about the standard media treatment of Cambodia had been well founded. This was the main impetus to collecting the information which is presented here.

Only after returning to Canberra in October 1980 did I attempt to systematize the information as it is presented in Chapters 3 and 4; and it was only then that I read some of the material published earlier on Cambodia’s fate after 1975. I had only begun to read Stephen Heder’s work mid-way through my time at Khao I Dang, and I did not look at Barron and Paul’s Murder of a Gentle Land nor the work of Kenneth Quinn until November 1980. Thus the way in which the material for this book was collected and organized was very little affected by previous work on revolutionary Cambodia, and it resulted almost entirely from at first random contacts with refugees on the part of a foreign historian of Cambodia who had known the country fairly well before the war and who was a competent speaker of the language. To the extent that the contacts were not random, it was a result of a search for people who had lived in regions not well represented in Khao I Dang, that is, anywhere except the Northwest or pre-1975 Phnom Penh, whose inhabitants made up over 70 percent of the Khao I Dang population.

I have made no attempt to count the number of people with whom I talked, nor even the number of people whose stories have directly contributed to the present work. Interested readers can do that for themselves. There is no claim here for statistical validity nor, given the conditions, could any statistically valid study have been undertaken. I was admittedly most interested in people whose experiences were different from the stories which had been given prominence in the international press, and I found my most valuable sources among those whose variety of experience, education, or intelligence enabled them not only to report their own experiences but also to make wider observations about conditions in Cambodia. My purpose has not been primarily to chronicle individual experiences, but at a higher level of abstraction to deal with general situations over rather wide areas. That the results have probably not been skewed by the statistically insufficient number of informants is indicated by the circumstance that Ben Kiernan’s information from an entirely different body of informants agrees with the areal and temporal patterns I have inferred, and interviews conducted by others, to the extent that they have been presented in a comparable manner, also support those relative conclusions even if there is a difference of opinion about absolute levels of suffering.

Although there is a scholarly apparatus indicating the source of each item of information, the purpose, contrary to that of most such edifices, is to prevent, rather than facilitate, direct access to the sources by the reader. Some people requested anonymity for various reasons, and since many informants provided me with information contrary to the accepted view of Cambodia, and which they themselves might regret seeing in the context in which I have used it, I thought it best to protect them all from harassment which might ensue. Thus the anonymity of most sources has been protected by using only initials or pseudonyms, and the only exceptions are people whose names have already been published elsewhere. The same initials always indicate the same person, and there has been no further attempt to disguise their identities through alteration of the details of their stories.

Some of the previous published work on Cambodia has been discussed and its information integrated into my own construction. There has not, however, been any attempt to survey the literature about Cambodia during 1975—82.

I have given attention primarily to work which represents either personal experience (Pin Yathay, Ping Ling, Y. Phandara) or direct questioning of Khmers (Barron and Paul, Carney, Heder, Honda, Kiernan, Ponchaud, Quinn) and which either adds to the picture I present or which in my opinion requires critique. Unless they were useful for illustrating a particular point, I have neglected those writings which are at third-hand, which are commentaries on the work of those who deal with primary sources, or which are exegeses of exegeses. Thus there may be people who have previsouly said some of the things I say or imply here, and my neglect of their work should not be taken to imply either disapproval or ignorance. It is simply because I have chosen to limit my discussion principally to my own and others’ collections of primary material, and I did not read other secondary compilations until my own material had been organized.

Several important areas of the recent history of Cambodia have been ignored. Except for the conflict with Vietnam, foreign relations have not been discussed at all, and even if the intricacies of relations with China, for instance, are interesting, I consider that foreign relations and influences are very nearly irrelevant for an understanding of the internal situation, which is the subject of this book.

There is also very little here about the structure and function of the governmental apparatus of Democratic Kampuchea—how decisions were made, how the distribution of produce was organized, how policies were determined and instructions for their implementation transmitted. Beyond the impressions which are recorded, that information was not to be found among my sources, and it may still not be available anywhere. Most of the Democratic Kampuchea officials in positions to know are either dead or still part of the DK forces, and virtually no documentary evidence on such matters has been preserved within Cambodia.

More could have been said about the history of Cambodian communism and the organizations which have represented it, but the specialist on those questions, Ben Kiernan, is soon to produce a dissertation on the subject, and I have included here only what is necessary for clarification of the events of 1975-1982.

In addition to those whose stories are the material of this book, I wish to express thanks to a number of people who, beginning in I960, first helped me to learn about Cambodia or who since 1979 aided and encouraged my work.

My wife Anchina and her family, from Battambang, were invaluable guides into the lives of ordinary Cambodians, and the family was instrumental in arranging some of my most interesting contacts in Khao I Dang.

My trip to Thailand in 1980 was facilitated by research and travel grants from the Australian National University, where I held the post of Research Fellow in the Department of Pacific and Southeast Asian History, Research School of Pacific Studies, and the wide freedom offered by that institution provided the time necessary to complete the work.

The International Rescue Committee (irc), under its then director for Thailand, Pierce Geretty, by taking me on in their educational program, made possible free access to the Khmer refugee centers in Thailand, without which the research could not have been undertaken. Since IRC has acquired the reputation of promoting a certain political line, I wish to state that its personnel involved in Khmer refugee work did not show any such ideological limitations, and were sincerely working to improve the conditions of refugees and advance the eventual recovery of Cambodia.

A number of people in other aid organizations helped me in various ways to find interesting sources and collect material, and if I do not try to mention them by name it is because I know some of them require anonymity.

Timothy Carney, Stephen Heder, Ben Kiernan, and Serge Thion all provided me with information from their own research and shared their own insights into Cambodian problems; Noam Chomsky gave much encouragement and often sent published material which I might otherwise have missed; and David Chandler took great interest in the project from its beginning, offering helpful advice and searching out relevant historical material.

John Barbalet, David Chandler, Noam Chomsky, Otome Hutheesing, Ben Kiernan, David Marr, Glenn May, Alfred McCoy, Ansari Nawawi, William O’Malley, Sandra Power, Andrew Watson, and Gehan Wijeyewardene read parts or all of either an early draft or the finished manuscript, offering helpful criticisms. If I did not always incorporate their suggestions, it does not mean I did not give them careful attention or appreciate the thought which was involved. Many parts of the finished product have been greatly improved through their suggested revisions.

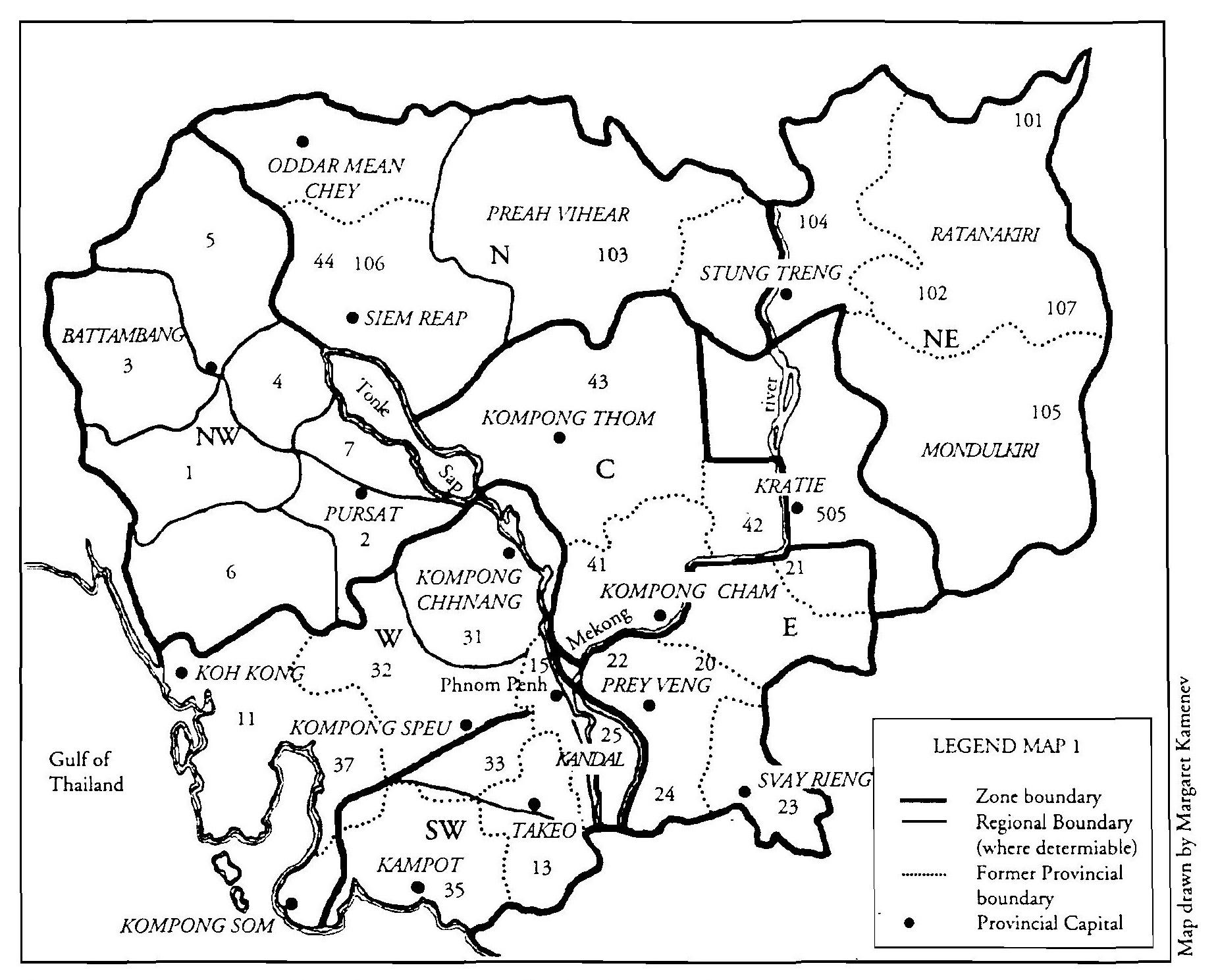

Map 1

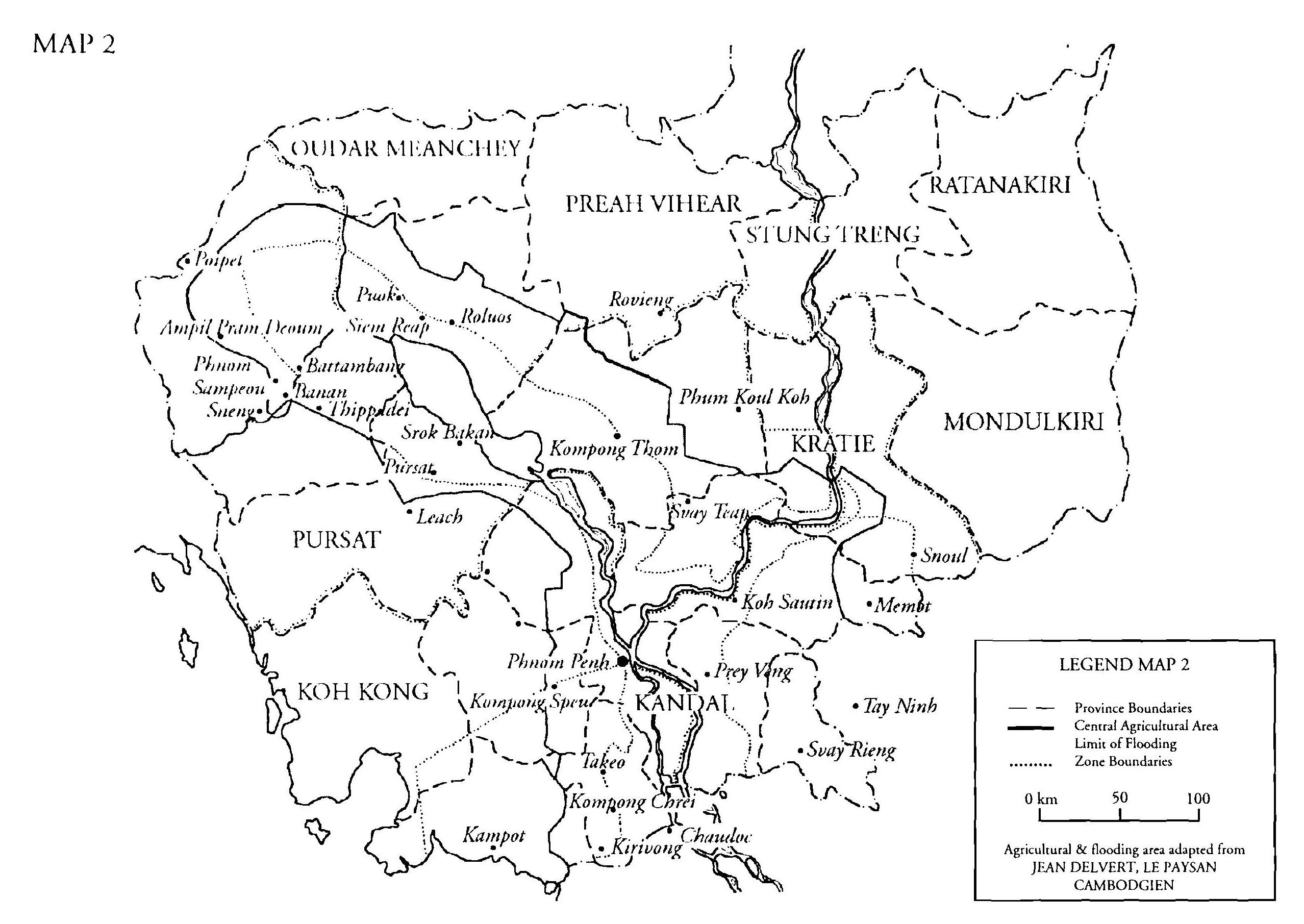

Map 2

Map 3

Chapter One: The Gentle Land

THE first thirty kilometers northwards from the main road were not too bad, and we covered them in half an hour. The next thirty over rough, dusty roads, took about twice as long, and toward the end of that stretch we saw something new to our experience—wild-looking boys, alone or in twos and threes carrying dead lizards strung on sticks like freshly caught fish. They were obviously hunting them to take home for the family dinner—a type of beast not eaten at all in any other part of the country I had seen. The last thirty kilometers to the village took about two hours, for the road had become nothing more than a track across dried-out former rice fields and there was a bump every few meters over what had once served as the embankments around the quadrangular plots.

On arrival in the village we stopped at the sala, an open pavilion found in all villages and used either for meetings or for temporary shelter. In fact, we expected that someone would invite us to his house to sleep and eat, as was common in Cambodian villages, but the people seemed strangely hostile. They grudgingly said yes, we could sleep in the sala, but they hoped we had brought our own food, for they had no rice—not having been able to plant any for three years because of drought. We also heard mutterings to the effect that they did not like city people anyway, for their arrival generally meant trouble.

The above is not an account of the arrival of “new” people, former city dwellers, arriving in a revolutionary village after April 1975, nor the report of a journalist in Cambodia in 1979—80, but impressions of a trip I made in 1962 to visit the Angkor-period temple of Banteay Chhmar.[8] Three of the details, however, recur constantly in the reminiscences of urban refugees: eating lizards and other exotic fauna, no rice, hostility of villagers toward city people; and it is this which makes the anecdote relevant as a starting point for a book about Cambodia from 1975 to 1981.

One of the most typical horror stories of Democratic Kampuchea (dk) is that of city families sent out to primitive villages or forest areas where there was little or no rice, where they had to forage for all sorts of unfamiliar food—lizards, snakes, field crabs, insects, roots; where the local people, if any, were hostile; and where many of them died of hunger and diseases, if not by execution.

The continuation of my own story is more cheerful. It is true that the Banteay Chhmar villagers had no rice, but they did not miss it, because they could find wild tubers and other vegetables in the forest, while protein was provided by chickens, pigs, fish caught in a pond not too far away, and of course the lizards caught by the boys along the road. Indeed, it seemed to be one of the healthiest backwoods villages I had seen, with large families of cheerful, robust children.

There was also an interesting, and potentially valuable, cottage industry. The villagers made beautiful silk, handling every stage of the process from raising the worms to dyeing and weaving the cloth. Perhaps, I first thought, this was their secret. They took their silk down to the market at Thmar Puok, twenty-five kilometers away, to trade for rice, sugar, and other goods. But my offer to buy some proved the contrary. The silk was for their own use; they had never sold any and did not want to; and when I tried to convince them I would give a good price which they could later spend in the market, they said there was nothing in the market they wanted. And I never did get any silk.

Another interesting feature of the village was the people’s dislike of anyone and anything from the towns of Cambodia. They had seen officials, some of very high rank, who had come to visit the temple or inspect the border area. The villagers hated their pretensions and false promises of aid and development. Most of all they disliked the officials’ wives, who minced about the footpaths in high heels with handkerchiefs held to their noses. Such people meant only trouble and it was best to avoid them and to hope that they never came to the village.

Thus for reasons of climate, inaccessibility, and incompatibility Banteay Chhmar village had evolved a nearly autonomous, autarkic lifestyle, wanting only to be left alone. Such villages were numerous outside the central rice plain and their inhabitants probably felt they had made successful adjustments to fate. At best they seemed healthy and happy, but had no access to modern medicine or to schooling beyond the bare rudiments, and often, as in Banteay Chhmar, did not have even a Buddhist temple or monks.

Perhaps it appears idiosyncratic to start a book about contemporary Cambodia with an anecdote about an excursion in 1962. But a major fault of most writing about recent events has been its ahistorical character, ignoring all that happened before 1970, 1975, or even 1979; and my purpose here is to emphasize that this is intended as an historical study, and to situate the events of 1975-81 within a view of earlier Cambodian society.

No precise estimate can be made of the number of such villages in pre- 1970 Cambodia, or the percentage of the total population living in them; but it is at least fair to say that the region of happy, Buddhist, rice-growing peasants of conventional-wisdom Cambodia was restricted approximately to the inundated area shown on map 2. Outside that area life was quite different, even if not to the extreme of Banteay Chhmar. This other Cambodia was virtually untouched by any kind of ethnographical or sociological study, but from the few glimpses we have, we can safely say that no assumptions about Cambodian life, attitudes, mores, and beliefs based on observations of the central rice-growing and gardening zones are likely to be accurate for the outer regions.

In some parts of the country these outer regions began within eight kilometers of provincial center. This was the case in Kompong Thom where immediately to the northest of the town was the forest homeland of the Kuy, who spoke a language related to Khmer but which was unintelligible to Khmer speakers, and whose way of life was very different from that of even the poorest Khmer peasants of the province.

The latter, in spite of appearing more “civilized,” must nevertheless have wished on occasion that their own relative isolation was more absolute. Officials on weekend picnics, or entertaining guests, would often drop into a village and request a housewife to kill a chicken and prepare a meal—and a request in those circumstances was equivalent to an order. If a foreign guest was present, the officials would take the occasion to deliver themselves of a little homily to the effect that the Cambodian peasant was so prosperous that a sudden requisition of food was no burden, and so hospitable that the task was not felt as an imposition. It is true that in those days—the early 1960s—no peasant family was going to starve by giving away a couple of chickens and a few bowls of rice; but on an occasion I witnessed, there was no doubt about the resentment which was felt.

The resentment could sometimes turn into overt hostility. Downriver a few miles from Kompong Thom, and well within the inundated region of “civilized” rice peasantry was a hamlet to which strangers were warned never to go, at the risk of being physically attacked. The precise reason was never made clear, but it was the result of some official action, possibly in French colonial days, which was perceived by the villagers as an atrocity and for which they threatened to take revenge if an opportunity arose.

In Siemreap the “other” Cambodia began on the north side of the artifical lake of the Western Baray and the park of Angkor and continued across the northern provinces to the Dangrek mountains. The population, at least between Siemreap and Phnom Kulen, was ethnic Khmer, living by forest gathering and hunting as much as by cultivation, and practicing strange rites rather than the official Buddhism. On the few occasions when I met them, while exploring the old temples of the region, they were not hostile, rather apprehensive in the presence of strangers, but clearly of a world entirely foreign to even a provincial town such as Siemreap, let alone Phnom Penh.

Exotic mores, as seen from Phnom Penh, could also be found well within the rice zone and among people who would count as ordinary, even comfortably prosperous, Cambodian peasants. On a trip downriver from Battambang to the Tonle Sap inland sea in 1966 I encountered a community where the most important ritual center was not Buddhist, but a spirit temple at whose foundation—apparently within living memory—a live pregnant woman had been buried; where the men—former Issaraks (Khmer postwar freedom fighters)—liked to joke over a fresh turtle dinner about the similarity in taste of that animal’s liver to the human variety; and where a woman who swallowed the raw gallbladders of freshly killed black dogs as a tonic was considered only mildly eccentric.[9]

In some places the line of demarcation between the two kinds of peasantry was apparently quite clear. One of my most useful informants at the Khao I Dang refugee camp,[10] speaking of his native district in Kamot province, told me that north of the road running between Chhouk and Kampot the population was isolated, hostile to everything urban, and, incidentally, revolutionary from long before 1970, while south of that road the peasants interacted with the market, were familiar with urban ways, and considered themselves part of wider Cambodian society. My informant was himself from north of the road, but had gone through high school and on to the university in Phnom Penh where he was caught by the downfall of the Lon Nol regime in 1975, sent back to Kampot as one of the “new” people, and forced to spend the next three and a half years working as a peasant. In this capacity, although he at first went to see his parents and former neighbors, he found it advisable to settle in a different hamlet where he was less well known, because of the general hostility to city folk, even those who were originally local sons.

I also met one of his friends who had had the same experiences, but whose origins were south of the road. The contrast between the two with respect to their feelings about pre-war society, their experiences of 1975-79, cooperation in the running of the refugee camp, and productive work in general was a vivid illustration of the two kinds of villagers, and one which did not redound to the credit of the “southerner.” In their accounts of the DK period these two men of identical economic, regional, and educational background and identical experiences during 1975—79 ordered their facts in such different ways and embellished them with such different value judgments that it would have been impossible to realize that they were telling, in essentials, the same story.

Cambodia, long before the enforced split into “old” and “new” people in 1975, was deeply divided. An important division was between town and country. But a more profound division lay between town plus town-related rice and garden peasantry and those rural groups who, through distance, poverty, ingrained hostility, or a conscious preference for autarky, remained on the outside of the Cambodian society which everyone knew and which Phnom Penh considered the only Cambodian society of any importance.

This outer society was not necessarly poorer. Food could be plentiful, and the people in Banteay Chhmar appeared healthy. Indeed, their knowledge of the environment and ability to cope with it were impressive. With no more than a sharp knife a man could go into the forest, build shelter, and find food; and such knowledge was still preserved among many of the real rice peasants as well.

Since they lived successfully in those conditions they probably saw no reason why other people, for instance the urban evacuees of April 1975, could not adjust; and they might easily imagine that failure to adjust was the result of laziness, corruption, or factiousness. Of course, there must also have been some schadenfreude at seeing the pretentious city folk brought down to their level, for villages like Banteay Chhmar, if they had not produced Communist soldiers or cadres, were at least part of the “old” people, of the base areas, whose long-suppressed resentment occasionally exploded in violence, however unjustified.

I remember in particular one spy they caught. He was very tough and wasn’t afraid of dying at all. He refused to confess, and only seemed to show some fear when they brought him to the edge of the burial pit. There at the edge the executioners hit him on the nape of the neck a couple of times with their clubs (made of kranhung hardwood, about one meter long, used to save bullets), he fell into the pit, twitched a bit, and then was still. For cruelty this was only an average execution, because the executioners were in a hurry. There were other methods really revolting to observe. One of them had a special name, srangae pen, literally “a field crab crawling around in circles.”

First of all the victim was beaten senseless. Then his arms were tied behind his back with the elbows together and he was made to kneel beside his grave. The soldiers stood around him in a circle and the executioner began to perform a ritual dance with a sword. While dancing he would suddenly come close to the prisoner and cut his neck just a little, just enough to make blood flow. Then he bent down and licked up the blood from the wounded neck and spat it onto the sword blade. This ceremony was repeated several times until finally the sword was plunged into the prisoner’s throat and he fell into the grave.[11] On another occasion a man believed to be an enemy agent was seized and interrogated. He denied the accusation and was threatened with death. He continued to deny his guilt and one of the interrogators struck him on the forehead with a pistol butt. Blood gushed from his head and mouth, but he still protested his innocence. Then they took turns kicking him in the stomach and he rolled on the ground in pain. Still he refused to confess and the group’s political leader decided they really didn’t have enough evidence on him. He was told he could get up and go away, but at about ten meters distance from the group they shot him in the back and killed him. Eventually it was discovered that the man was innocent, but that the cadres were angry with him for protecting his sister against their attempts at seduction and had fabricated evidence that he was a traitor.

These stories do not come from Pol Pot’s Cambodia, but from a book by Bun Chan Mol, published in 1973 and relating his own experiences among the Cambodian Issaraks in the 1940s.[12] He himself was political leader of the group carrying out the executions, the enemy for whom the prisoners were accused of working was the French colonial administration, and the title of the book is Ch arit Khmer, “Khmer Mores.”[13]

Bun Chan Mol gave up Issarak activities in 1949; and one of the reasons, he tells us in his book, was his inability either to tolerate or suppress the gratuitous brutality of his underlings who considered such methods a normal way of dealing with enemies and who took obvious pleasure in it. Besides their delight in inhuman torture, he complains about their indiscipline, refusal to investigate thoroughly before taking action, arbitrary exercise of power, sometimes for petty personal reasons, and suspicion of anyone who objected, including himself, their political chief. He calls these practices part of “Khmer Mores,” the title of his book, most of which deals with the decline of Khmer politics in the 1950s and 1960s.

Swift and arbitrary capital punishment was also not foreign to those early Cambodian rebels whose standards of discipline were high, who had an immense popular following, and who for years afterward were idealized by non-Communist progressives.

Son Ngoc Thanh, during his brief tenure as prime minister in 1945, was blamed for executions of political opponents, and later, in his maquis in northern Cambodia, harsh justice for infringement of rules was an accepted norm. In a French intelligence report of 1952 his lieutenant, Ea Sichau, who was considered both then and afterward a sincere idealist with high standards of morality, is said to have executed, on the grounds that they were enemy agents, a group of eight students and teachers who had found jungle life too difficult and wished to go home.[14]

In this respect, the one difference between Thanh and Sichau, and the earlier Issaraks or later Democratic Kampuchea cadres, is that the regulations of the first were consistent, equally and fairly applied, and recognized in advance by the people who joined them.

Issarak violence was not the specialty of the politically unstable frontier area of Battambang and Siemreap. Just thirty kilometers southwest of Phnom Penh, in a district of semi-urbanized rice peasants, “the Issarak were their own law . . . killed anyone they wanted to kill . . . sometimes siblings could not speak to one another because one was an Issarak and the other worked for the government in Phnom Penh”; and a number of families fled temporarily to Phnom Penh to escape from the threat of such Issarak extremism.[15]

Often the vocation of Issarak was no more than a device to give a patriotic cover to banditry, which had long been endemic in parts of rural Cambodia; and the “bandit charisma” may have been as strong a motive as nationalism in attracting men to Issarak life.[16]

Patterns of extreme violence against people defined as enemies, however arbirarily, have very long roots in Cambodia. As a scholar specializing in nineteenth century Cambodia has expressed it: “It is difficult to overstress the atmosphere of physical danger and the currents of insecurity and random violence that run through the chronicles and, obviously through so much of Cambodian life in this period. The chronicles are filled with references to public executions, ambushes, torture, village burnings and forced emigrations.” Although fighting was localized and forces small, “invaders and defenders destroyed the villages they fought for and the landscapes they moved across. Prisoners were tortured and killed ... as a matter of course.” Even in times of peace, there were no institutional restraints on okya [a high official rank] or on other Cambodians who had mobilized a following.[17]

Sudden arbitrary violence was still part of the experience of many rural Cambodians in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. A woman acquaintance told me how her father, a Battambang Issarak leader at the time of which Bun Chan Mol was writing, used to keep his prisoners chained up beneath the house without food or water and then execute them on his own firing range a few hundred yards beyond the back yard. He was not a pathological sadist either, but a good family man remembered fondly by his widow and children.

Later, in the Sihanouk years, the same woman was accused falsely by police of being involved in Dap Chhuon’s movement and threatened with torture.[18] She was saved, not because she was innocent, but because an uncle, who was a colonel in Phnom Penh, found out about her arrest and intervened.

Probably few Cambodians entertained doubts that traitors, or even enemies, should be killed. When a teacher friend in Kompong Thom in 1961, victim of a politically inspired denudation, was accused of conspiring with an “American agent” (myself) he had to resort to a highly placed uncle for protection. The latter intervened, but told his nephew that if he were really guilty of what had been alleged—in fact nothing more serious than political conversations with a foreigner—he deserved death. Likewise, a Cambodian student who returned from North Korea in 1976 accepted with equanimity that “traitors” were killed in Korea in the 1950s and in Cambodia after 1975. Like all the “left” bourgeoisie, he had expected to occupy a privileged position in the revolutionary regime, and he was only shocked by liquidations when he discovered that he himself fell into a category of political enemies. Another man, whose own brother, a pre-1975 acquaintance of mine, was executed, said, “it wasn’t so bad that they killed people, that could be understood, but that they chose to use such cruel methods.”[19] It should also not be forgotten that not until 1972 did the Lon Nol government, under pressure from unfavorable media attention to own atrocities, announce that Vietnamese prisoners would be treated according to international conventions.[20]

In spite of the slant of the foregoing stories, however, I do not believe that discussion of the “Khmer personality” or Khmer psychology is very useful in an explanation of the DK phenomenon. As Stephen Heder, a student of the Cambodian revolution, has noted, anti-Communist refugees tend “to understand the nature of and explain the atrocities of the Democratic Kampuchea regime in very clear class terms,”[21] and a search for such explanations in objective economic, social, and political circumstances is always preferable to nebulous psychologizing. It is important to realize, however, that Heder’s informants analyzed the peasant class, who were their enemies, on the basis of their own subjective impressions of peasant culture and psychology. Furthermore, even if the genesis of a revolution is explained through a rigidly objective class analysis, the specific behavior of the victorious peasants or workers, or of other formerly oppressed people, will be determined, at least in part, by the old habits of their culture. Thus Ebihara’s informants, along with some Cambodians I have met, and in particular Bun Chan Mol, are invaluable as participant observers who, beginning in the 1940s, saw as part of “Khmer mores” some signs of what is now considered as Pol Pot extremism; and if the broad structure of post-1975 developments is amenable to explanation from objective circumstances and high-level policy decisions, the details owe something to those old “Khmer mores.”

Much of the foregoing has dealt with traditions of violence, but what about the famous Khmer Buddhism with its “precepts and practices [which] pervade the values and behavior of the populace who accept this religion sincerely and devoutly” and which was “the very apprenticeship of tolerance”? Was it not supposed to be the source and guarantee of the gentleness which all observers believed they saw in Cambodia and which gave “inner serenity and the habit of kindness toward all”?[22] Were the Issaraks of the 1940s and the dk cadres of the 1970s not Buddhists? (At first their enemies, the French in the first instance and the Lon Nol government in the second, tried to claim they were not Khmer, but Vietnamese.) And since they must once have been Buddhist—i.e., they were Khmer and all Khmer are Buddhist—what accounts for their easy rejection of Buddhist mores for (more purely?) Khmer ones?

Probably more arrant nonsense has been written in the West about Buddhism than about any other aspect of Southeast Asian life. Like every other major religion, Buddhism as it is practiced in the countries where it has ancient roots is a concretion of certain admirable philosophical and moral principles with beliefs and practices which date from pre-Buddhist times, prejudices peculiar to the society, special relationships with ruling classes, and the ability to rationalize the pursuit of material gain, as well as a good many other actions which are contrary to its principles. That Buddhists may torture and massacre is no more astonishing than that the Inquisition burned people or that practicing Catholics and Protestants joined the Nazi SS.

Ebihara got very close to what Cambodian Buddhism really means: “the villager himself rarely conceives of observing separate religious traditions [Buddhist, Hindu, folk]. Rather, for the ordinary Khmer, Buddha and ghosts, prayers at the temple and invocations to spirits, monks and mediums are all part of what is essentially a single religious system.” Instructive also was the religious vocation of an eighteen-year-old girl who said, “I think I will go to three or four kathun festivals this year so that I will be reborn as a rich American.” [23]

One of the most important functions of Cambodian popular Buddhism is the opportunity it gives for making merit—by participating in certain festivals, by giving food to monks, or, for men, by becoming a monk oneself. The desire to make merit results from the Cambodian understanding of Buddhism as a fatalist doctrine which holds that our condition in the present life is the result of our past conduct, while our conduct in this life, good or bad, will determine our fate in future existences.

Moreover, the opportunity of making merit was not the same for all, something which has hardly been touched on in the anthropological literature. Almost all forms of making merit depended on giving up some part of one’s own economic surplus to, or for, the temple and monks. Cambodians did not believe that the poor man’s mite equaled the rich man’s gold. On the contrary, the more spent, the greater the merit accrued; and thus those who were already wealthy due to the supposed accumulation of merit in former existences had greater potential for accumulating further merit as insurance for the cosmic future.

Ebihara touches on this aspect of Cambodian Buddhism in her central Cambodian rice village. She notes that about three-fourths of the men over the age of seventeen had at some time been monks. But the poorest families could not always spare their young men from field work to become monks; and about 17 percent of all adult men fell into that category.[24] These poorest peasants, then, were deprived by their poverty’ of the main merit-making and cosmic insurance function of their society’s religion. We can surmise that some of them, at least, must have felt resentment, compounded perhaps by the fact that in traditional Cambodian society’ a period spent as a monk was essential to becoming a full adult with one’s own wife and family.

One would expect a tendency on the part of such men to reject Buddhism, at least the idea of accepting fate, and in fact Ebihara found, already by 1959, just such a tendency, not only among the poor, but among wealthier people as well. Modern life and secular education impelled them to work for the present and to lose interest in religion. In her village the number of men who had been monks was in inverse proportion to age, and none of the men in the ten- to nineteen-year-old group had any plans to follow this old tradition.[25] I found similar attitudes among my teacher colleagues in 196061. Of twenty or so teachers between the ages of twenty and thirty, half a generation older than Ebihara’s youngest group, only one had served his term as a monk, and most of the others openly ridiculed religious traditions, considering monks to be social parasites. This last attitude, then, was not the exclusive property of Pol Pot fanatics, but already ten years before the war existed among peasants and middle-class youth, most of whom in 1975 found themselves on the wrong side.

Even earlier, during the first Indochina war, certain anti-clerical tendencies which have since been associated with DK were already manifest.

French intelligence reports of June—July 1949 gave some attention to a band of rebels under one “Achar Yi,” who operated in Kandal and Prey Veng. They were apparently non-Communist, since on one occasion they announced an intention to “massacre the local Vietnamese, whether Viet Minh or not,” but they were also noted for burning the sacred scriptures in temples they suspected of following modernist tendencies.[26]

Thus chauvinism, linked to peasant traditionalism in a form which could countenance destruction of religious paraphernalia, already had roots in the Cambodian countryside.

There was also an iconoclastic tendency among some non-revolutionary, law-abiding people, including monks. In 1971, visiting a monk I had known for some years in Battambang province, I remarked on the almost disrespectful way he seemed to regard Buddha images in his temple. He explained that the images were really only useless idols, unimportant to a real understanding and practice of religion. It is impossible to ascertain how widespread this monastic sub-culture was; and it may be only a coincidence that this man and all his relatives and acquaintances had been part of the early Issarak bands described by Bun Chan Mol in the northwestern districts noted for violence both in those days and under DK.[27]

For those who wished to reject their religion, for whatever reason, poverty or modernism, it was, however, better to be Buddhist than Christian, for the former contains a nice escape clause for the backslider. As Pin Yathay put it, “you are responsible for yourself; you are your own master . . . Buddha is not a god . . . only a guide. He shows you the way ... it is for you to convince yourself that the way he indicates is good.”[28] Thus for those who rejected it there was no superior moral force to accuse or punish them. If in rejecting religion they also committed crimes, they would not be punished by a deity. They might risk cosmic demotion in a future life, but it was also possible to calculate that later good works could offset the bad on the cosmic balance sheet. Besides, the non-Buddhist folk practices which were a part of every Cambodian’s religious heritage provided many other sources of protection, both physical and spiritual.

In the face of gradual disaffection from traditional Buddhism which Ebihara noticed, the Cambodian elite sought to reemphasize religion as a technique for repressing the new desires for social mobility. In 1955, when revolutionary forces were threatening, a newspaper representing Sihanouk’s new coalition of the right maintained editorially that the country should be ruled by its natural leaders, who are the rich and powerful. The less fortunate should not envy them and try to take their places, for each person’s situation in the present is determined by his past actions. The poor should accept their fate, live virtuously, and try to accumulate merit in order to improve their station in another existence.[29]

At the same time, and perhaps in an effort to counter the anti-monastic disaffection of the youth, there were attempts to associate the monks with nation-building. Thus in one of Sihanouk’s glossy magazines a photograph of monks at work on a road or dike construction site was accompanied by the caption “monks within the framework of our Buddhist socialism participate in the work of nation-building.’ [30] This of course prefigures the DK treatment of monks, and for traditionalists could have represented sacrilege.

Even violence could be linked with the practice of Buddhism if it was in defense of the established order upholding the official religion. One of Lon Nol’s favorite themes, on which he composed a series of pamphlets, was “religious war” in which he tried to identify the Vietnamese and Khmer Communists with the thmil, the enemies of the true faith in old Buddhist folklore.[31] Violence in the service of the true faith could be used to link Khmer Buddhists and Islamic Chams, the largest indigenous minority in Cambodia. During the first two years of the war a Cham colonel, Les Kasem, gained fame with a Cham battalion which was reported to have systematically destroyed and exterminated “Khmer Rouge” villages which they occupied. Its notoriety was finally such that the government realized it was counterproductive and the battalion was split up among other units. Proreligious violence is also attractive to some Christans, like Ponchaud, who proudly retails the story of a Cham father who murdered his sons for accepting Communist discipline.[32]

It is no wonder that poor peasant youth returned from short Communist seminars full of anti-religious fervor.[33] Cambodian Buddhism was desecrated, long before the DK regime closed the temples, by the blatant class manipulation of the faith under Sihanouk’s Sangkum Reastr Niyum (Popular Socialist Community), followed in Lon Nol’s republic by the designation of temples as military recruitment stations.[34]

Long before the war the poorest had reason to feel some resentment of the religious structure, and the middle groups were losing interest for materialist reasons. For both, at bottom, the mixture of Buddhist principles, old Hindu rites, and ancient folk beliefs which together constituted Cambodian religion, represented techniques for ameliorating one’s material life, either now or in the future. If the religion was seen to fail in that respect, disaffection occurred.

Such disaffection was massively apparent among the refugees in camps in Thailand, where in 1980 there were more registered Khmer Christians than in all of Cambodia before 1970. To accuse missionaries of manufacturing rice Christians misses the point. As one particularly sophisticated family which I had known in Phnom Penh put it: “Look at what happened to Cambodia under Buddhism; Buddhism has failed, and we must search for some other faith.” [35]

Some fifty-odd years ago another such large-scale disaffection occurred. Around 1927, at a time of economic and political difficulties, thousands of Cambodian peasants took an interest in the Cao-Dai religion—a faith of the “hereditary enemy,” the Vietnamese—going to worship and participate in ceremonies at the Cao-Dai headquarters near Tay-Ninh. At the very least this “reflected the reaction of a disoriented peasantry ready to turn to the newly offered salvation that they believed would involve the regeneration of the Cambodian state.”[36]

Rejection of traditional religion and the proliferation of non-Buddhist violence are thus well within the Khmer cultural heritage, whether the specific manifestations are a temporary interest in Cao-Dai, Issarak savagery, modernist derision, or DK official atheism.[37]

If Buddhism proved to be no barrier to class antagonisms, or to violence, much in the country’s social and economic structure tended to encourage both. [38]

Traditional Cambodian society was formed essentially of three classes— peasants, officials, and royalty. Very few Khmers became merchants, and to the extent that an urban population apart from the court and officials existed, it was composed mainly of non-Khmers, generally Chinese. This division of society probably goes back to the Angkor period when national wealth was produced from the land and collected by officials, who channeled it to the court and religious apparatus where it was used largely for building the temples and supporting the specialized population attached to them. A part of the wealth collected by officials remained in their hands for their support in lieu of salary, but this was accepted as the way in which the system naturally functioned. Each of the classes had a function believed essential for the welfare of the society, and in which the king’s role was quasi-religious and ritual.[39]

Although the Angkorean state declined and disappeared, the old divisions of society persisted. For the mass of the population, social position was fixed, and it would have been almost unthinkable to imagine rising above the class into which one was born. Occasionally, perhaps in time of war, or for exceptional services to a powerful patron, someone from a peasant background might rise into the official class and thereby change the status of his immediate family; and clever children might be educated in an official family or at court to become officials; but such occurred too rarely for any expectation of social mobility to be part of public consciousness.

The possibilities of wealth accumulation were also limited. Land was not personal property, but in theory belonged to the king. An energetic peasant could thus not accumulate land and wealth through hard work and abstemiousness and move up the scale to rich farmer, entrepreneur, or whatever. The only possibility for wealth accumulation lay in an official career. Even there life was hazardous. Officials were of course more or less wealthy, and the official status of a family might continue for generations; but their status was not assured by any formal legality, and could be ended precipitously at royal displeasure—for instance, if an official showed signs of accumulating too much wealth or power. Even if a career did not end in disgrace, wealth accumulated in the form of gold, jewels, other precious goods, or dependents, might revert to the state at an official’s death rather than passing in inheritance to his family. There was thus no incentive, or possibility, to use wealth for long-term constructive purposes or entrepreneurial investment.

Village and family organization, especially if compared to China, Vietnam, or India, were extremely weak. Khmer villages were not cohesive units, as in Vietnam, dealing collectively with officials; and beyond the nuclear household, families easily disintegrated. Family names did not exist, records of previous generations were not kept, ancestors were not the object of a religious cult. Corporate discipline over the individual by extended families or by village organizations was weak, and once a person had fulfilled his obligations to the state—as a tax or corvee—there was little constraint on his activities. It is thus likely that a paradoxical situation of great anarchic individual freedom prevailed in a society in which there was no formal freedom at all.

The relations among royalty, officials, and peasantry, which did not begin to change under colonial impact until after 1884, were organized in forms of dependency. Everyone below the king had a fixed dependent status which served to determine his obligations to the next higher level and also provided protection. The provinces of the realm were given in appanage to the highest officials of the capital whose agents in the provinces collected the taxes and organized the corvee which were the raison d’etre for the system. Each peasant in theory, and in the central agricultural provinces in reality, was the dependent client of an official whose identity he knew.

Besides such dependence at all levels of society within the country, the Cambodian ruling class had for centuries been dependent on foreign overlords and protectors, usually Siamese and Vietnamese, but at one point in the 1590s, Europeans;[40] and French protection against Vietnam was sought in the nineteenth century even before the French were ready to impose it.[41]

There was thus no serious conception of self-reliance at any level of Cambodian society, and in a crisis everyone looked to a powerful savior from above or outside rather than seeking a local solution.

Kings looked to ever more powerful protectors both against their neighbors and their own people, a practice which even Sihanouk did not give up, in spite of his rhetoric to the contrary. His “crusade for independence” was imposed on him by challenges from the left, and the independence granted in 1953 was in a way a Franco-Sihanouk collusion to block a Cambodian revolution. All through the formally anti-United States years of the 1960s he never renounced the desire for an American protective shield against the Communist Vietnamese.[42]

Lesser members of the elite acted in similar fashion. The protest of Prince Yukanthor against the French protectorate in 1901 is often treated as an anticolonial manifestation, whereas in fact Yukanthor was berating the French for neglecting to provide adequate protection for the traditional elite against upstart commoners who were taking advantage of the expanding colonial bureaucracy to advance themselves economically and socially.[43]

At the lower levels of society peasants who felt oppressed would seek to change patrons, or if pushed to violence they turned to anarchic banditry, which caused more suffering to their fellows than to the oppressive officials. In contrast to the Chinese or Vietnamese mass peasant rebellions which occasionally took state power and started a new dynastic cycle,[44] no peasant or other lower-class rebellion in Cambodia before the 1970s ever snowballed into a movement which endangered the system.

This was no doubt in part due to the individual anarchy resulting from lack of corporate units above the family. The potential rebel wished to be bought off, not change the system. This is seen in the circumstance of the first stirrings of modern nationalist rebellion against the French, and contrasts with the earlier and more thoroughgoing organization in Vietnam. Soon after the murder of the only French official killed in the twentieth century by ethnic Khmers while carrying out his official duties, the guilty villagers “returned, ashamed, to the village, and before long were turning one another in to the police,”[45] and in the 1940s at the French political prison on Pulou Condore, the trusties, police spies, and torturers were all Khmers currying favor for individual special treatment, while the Vietnamese maintained a spirit of political solidarity and organized classes in Marxism.[46]

The same client mentality persisted right on into the 1970s, at least among one part of the population. Not only did Lon Nol and his coterie rely on foreign protection, but so did all those outside the revolutionary camp who saw the hopelessness of the government position. When it was clear by 1972 that a Lon Nol government could not win, those generals and civilian officials who might have retrieved the situation, instead of simply taking power, kept hoping vainly for the Americans to act in their favor. I suppose every American in Phnom Penh at the time shared my experience of friends and acquaintances asking in desperation, “Why doesn’t the CIA do something?”

In the end their dependency led them to acquiesce in, or even encourage, the devastation of their own country by one of the worst aggressive onslaughts in modern warfare, and therefore to appear as traitors to a victorious peasant army which had broken with old patron-client relationships and had been self-consciously organized and indoctrinated for individual, group, and national self-reliance.[47]

If the traditional system seems in retrospect oppressive, we must remember that before the twentieth century Cambodians, like most Asians, knew no other, and that the demand for wealth by the elites was generally limited to what could be consumed or spent within the country.

Although much of the formal system was changed by the French, there was not a corresponding change in attitudes and values. Officials continued to see their positions as ends in themselves, as situations in which to accumulate, for consumption, part of the wealth extracted from the peasantry and passed upward to the rulers. After they were put on a salary by the French, such additional accumulation was illegal, but as a traditional practice it was not felt to be immoral, and the corruption which later became such a serious problem began thus as a continuation of an accepted traditional practice. The exploitative character of colonialism thus merged easily with the exploitative character of tradiiional society, and intensified it; and for many of the Cambodian elites the evil of colonialism probably resided less in its exploitative character than in the fact that they were not in ultimate control.

I do not intend to argue that the Cambodian revolution was caused just by economic pressure on the peasantry. That would be incorrect. If it had not been first for the revolutionary movement in Vietnam and then for foreign military intervention with its attendant destruction, Cambodia might well have gone on for years with a level of insurgency too strong for the government to suppress, but not strong enough to take over state power.[48]

It is nevertheless important to stress that exploitation of the peasantry was increasing throughout the twentieth century and if it alone did not push Cambodians to revolution it was responsible for serious rural-urban antagonisms.

Taxes were increased by the French, particularly after World War I, and were the highest in Indochina, with part of the funds funnelled elsewhere in the federation rather than used in Cambodia. In particular, taxation was “heavy in terms of any benefits. . . returning to the peasant”; and the murder of a French official in 1925 was due to his attempt to collect taxes in arrears. There were also onerous corvees for public works, first of all roads; and in one infamous project, the construction of a resort at Bokor, nine hundred workers’ lives were lost in nine months, a statistic comparable to the human cost of a Pol Pot dam site.[49]

French efforts to reimpose their protectorate regime after a brief period of Japanese-sponsored “independence” in 1945 led to a multiplicity of guerilla operations by Issaraks representing all shades of the political spectrum, and in general directed against the French and the royal government of Prince Sihanouk. The years 1946—52 were increasingly violent, with the rebel forces eventually controlling large areas.[50]