Michael Dartnell

Action Directe

Ultra-Left Terrorism in France, 1979-1987

1 Interpreting Terrorism: A Case-study of Action directe

2 French Traditions of Political Violence and Protest

3 The Elusive Formula: Gauchistne, May 1968 and Action directe

4 The History of Action dire etc. From Gauchisme to Nihilism

5 The Ideological Trajectory of Action directs. Radicalization and Violent Protest

Appendix 1: Chronology of Action Directe, 1979-90

Appendix 2: Attacks by Action Directe, 1979-87

Appendix 2.2 Types of Political Violence in France

Appendix 3 Murders and Attempted Murders by 4c77(W 1979-87

Appendix 4.1: Attacks by the Croupe Bakounlve-gdansk-parisguatemala-salvador (Gbgpgs)

Appendix 4.3: Action Directs Trials and Imprisonment

Appendix 4.4: Action Directe Commando Units

Appendix 5.1: Coawunique Num£ro 7, 18 March 1980

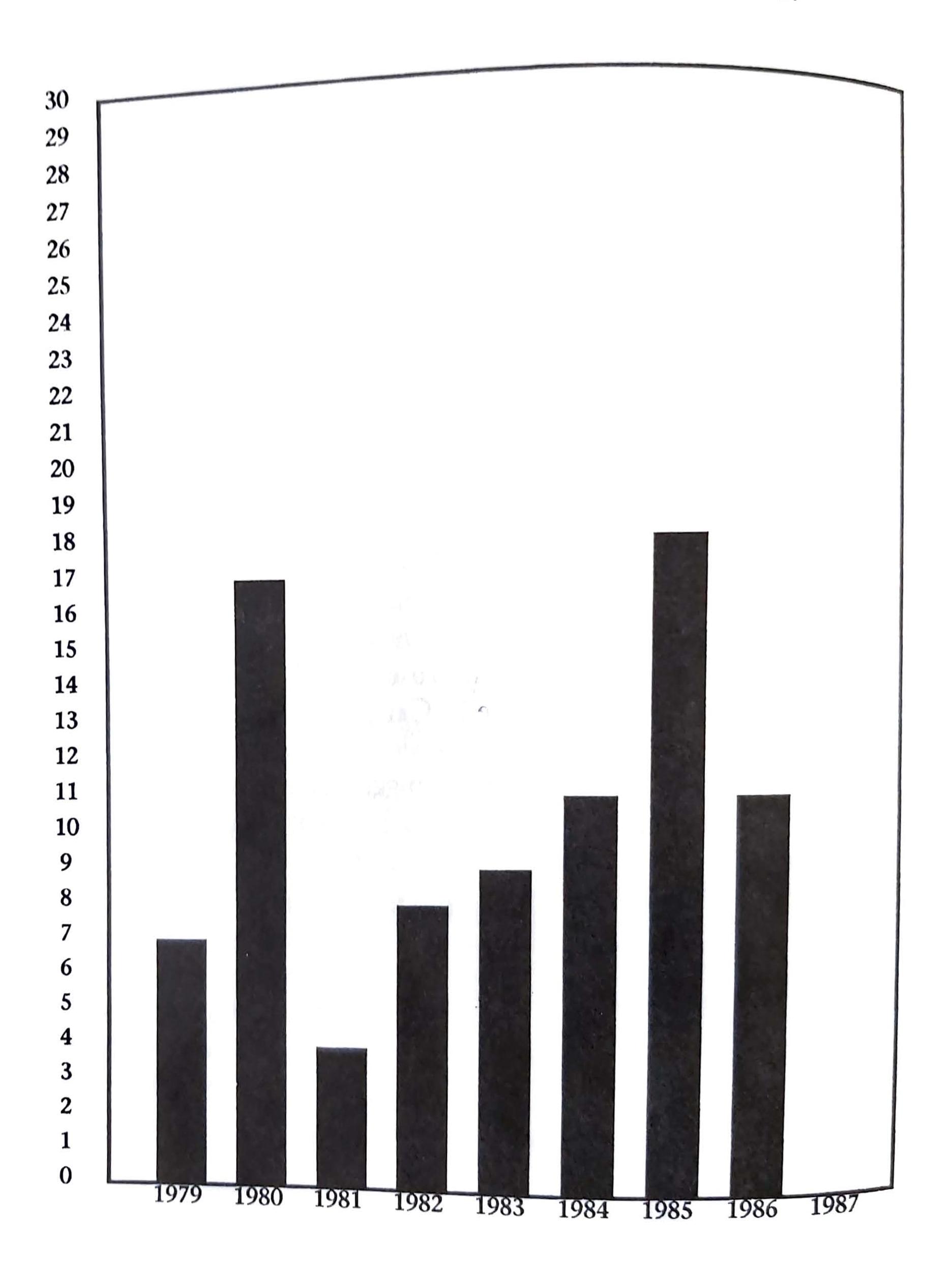

Appendix 5.2, Number of Attacks by Action Directe, 1979–87

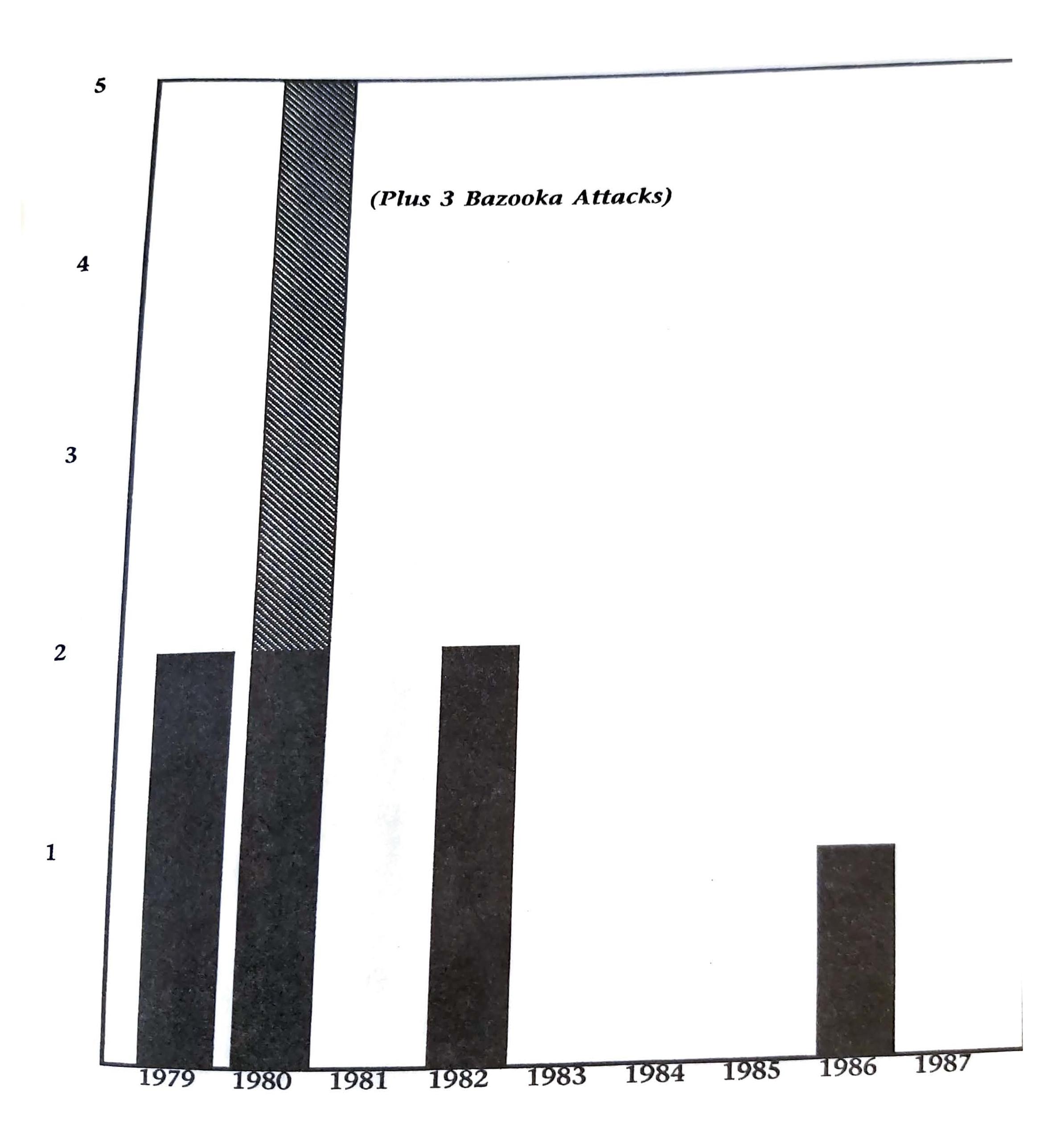

Appendix 5.3, Machine-Gun Attacks by Action Directe, 1979–87

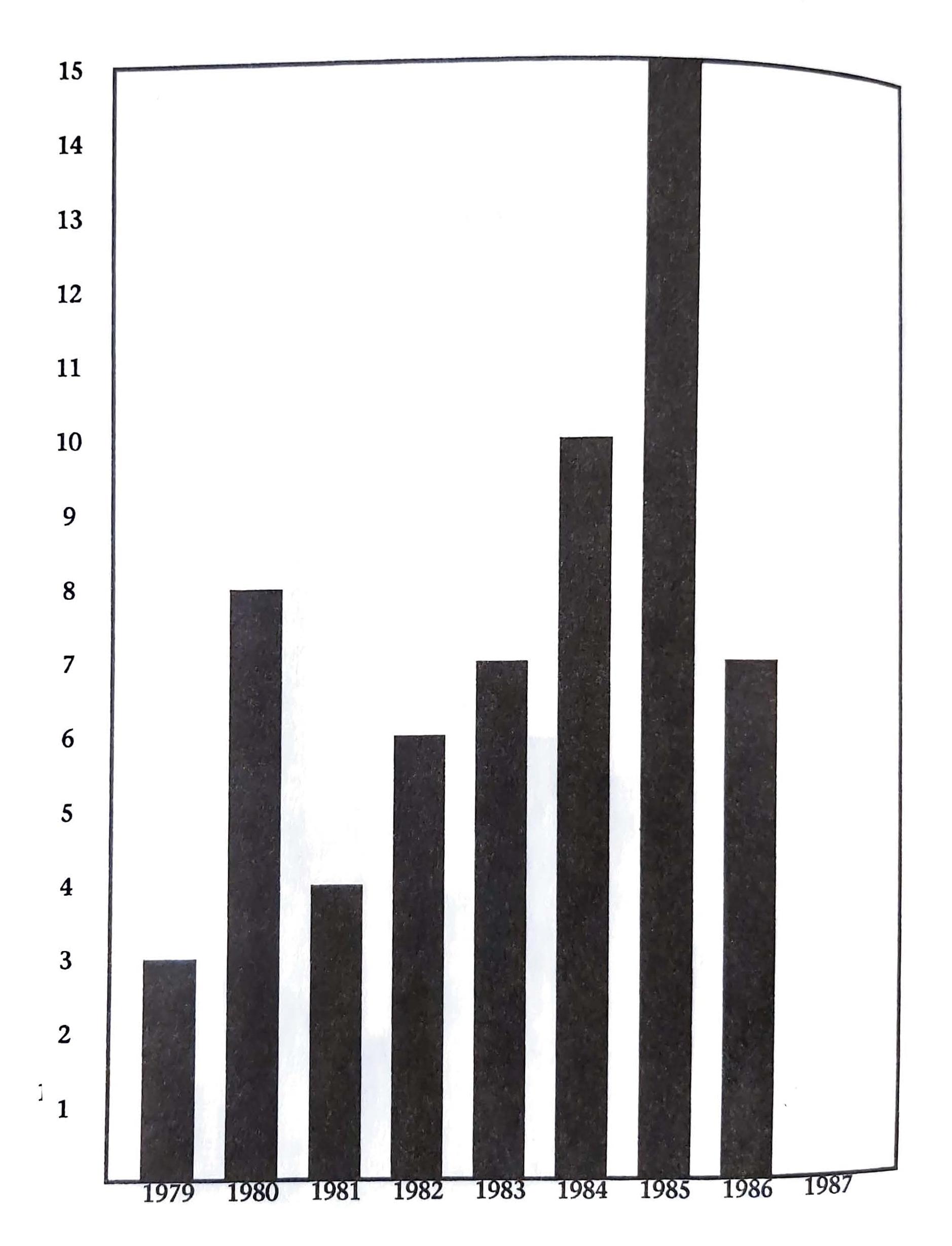

Appendix 5.4, Number of Bombings by Action Directe, 1979–87

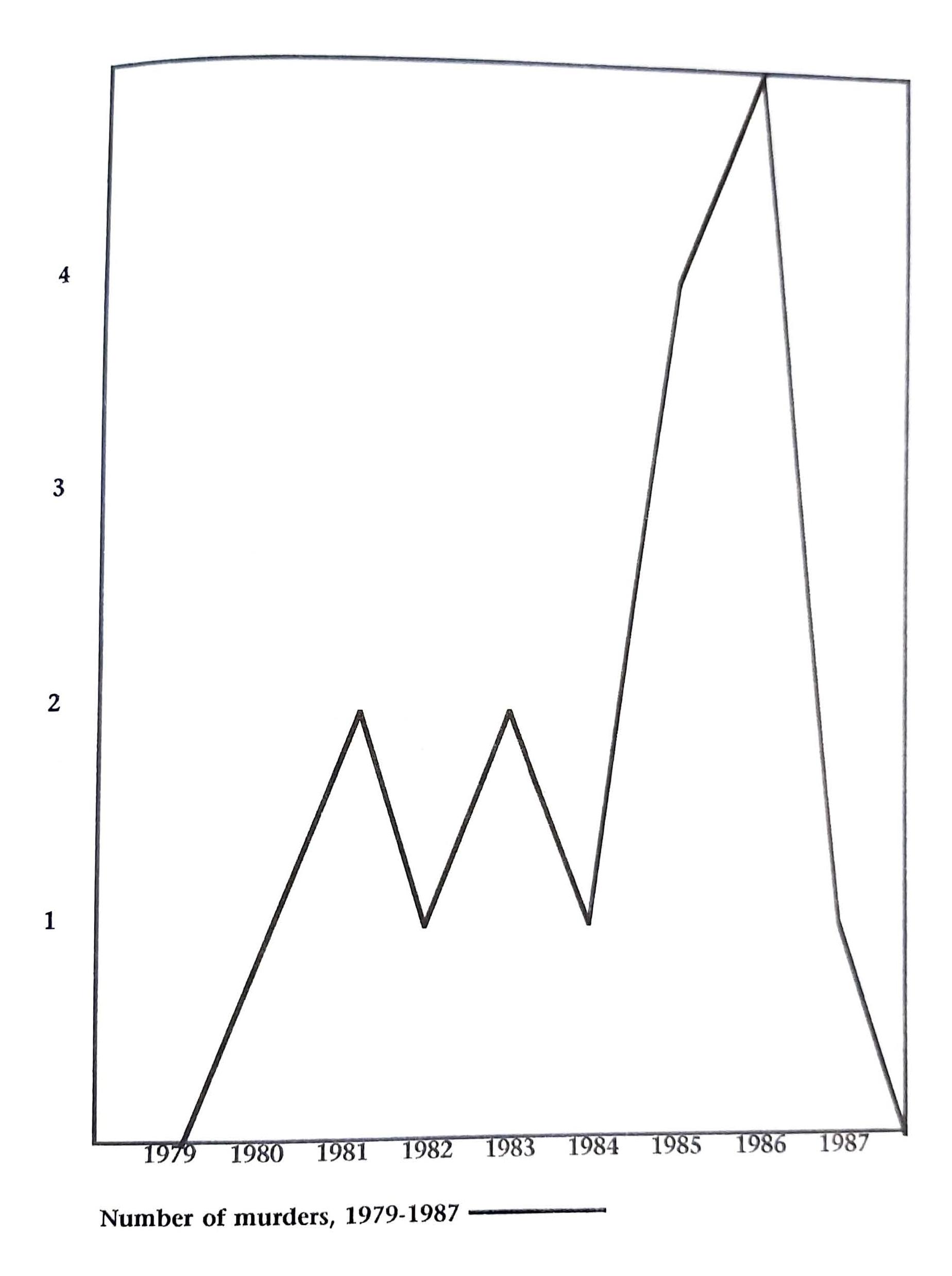

Appendix 5.5, Number of Murders by Action Directe, 1979–87

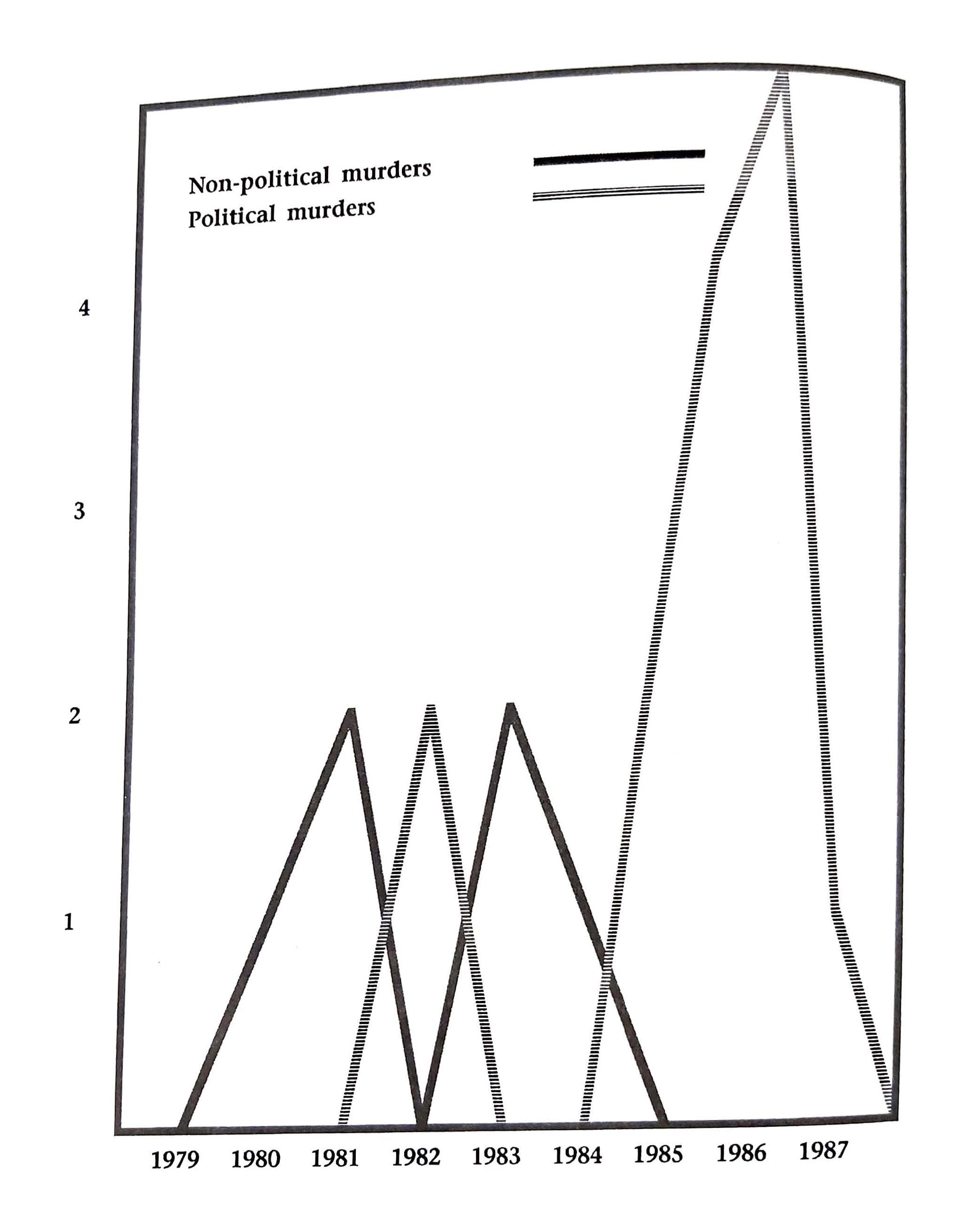

Appendix 5.6, Political and Non-political Murders by Action Directe, 1979–87

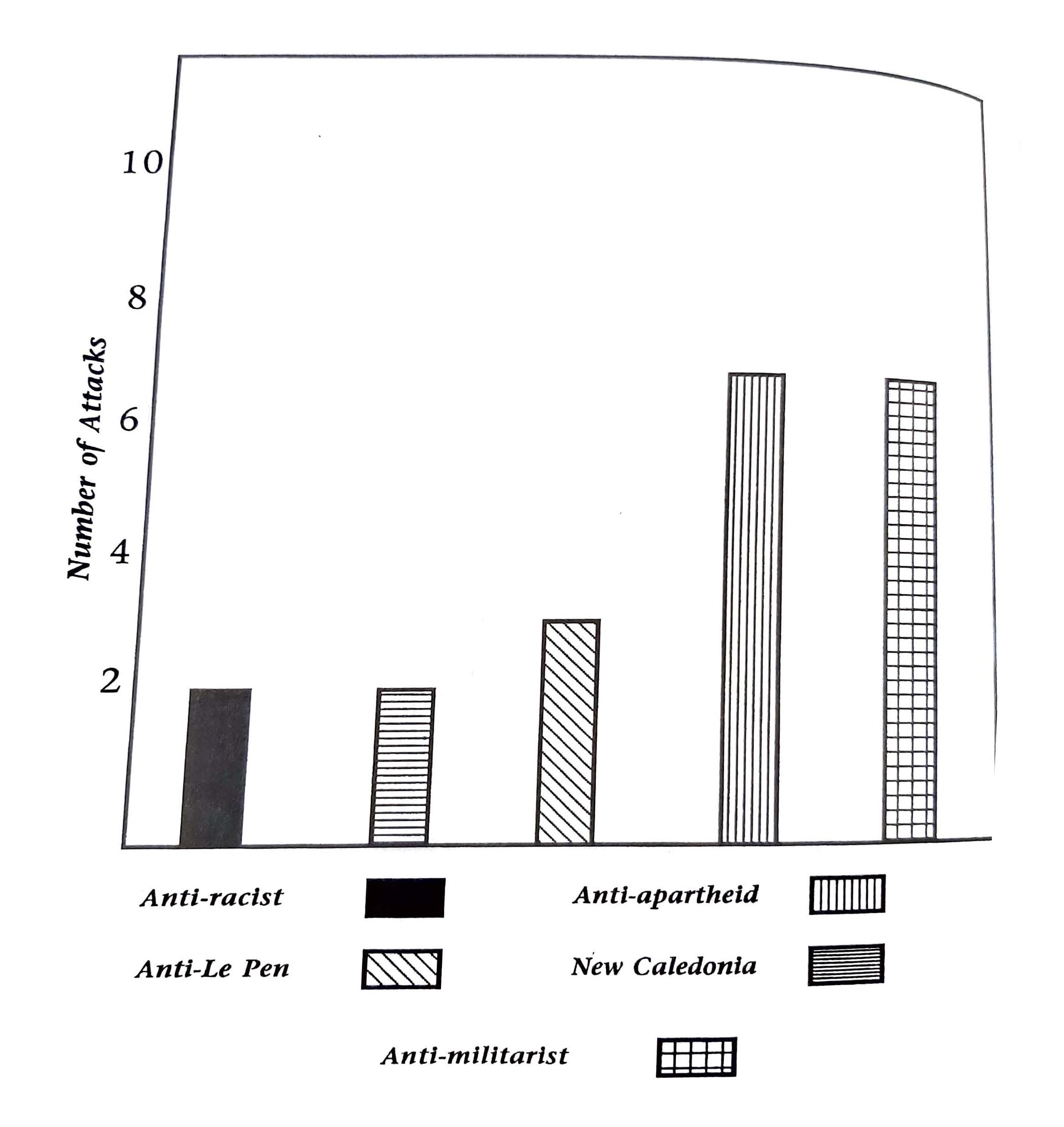

Appendix 6.1 Motivations for Action Directe, International Attacks, 1982-87

Appendix 6.2 Motivations for Action Directe, National Attacks, 1982-87

Action Directe Ultra Left Terrorism In France 1979 To 1987

ACTION DIRECTE

Ultra-Left Terrorism in France, 1979-1987

Michael Y. Dartnell

Concordia University, Montreal

FRANK CASS LONDON

Acknowledgements

It is a pleasure to acknowledge the contribution of many people to this text, 1 would first of all like to thank Professors Ross Rudolph, Steven Hellman and Robert Albritton at the Department of Political Science at York University, for their support, encouragement annd criticism. Ross Rudolph in particular patiently provided advice and encouragement throughout the preparation of the document despite his highly charged schedule. Steven Hellman supplied invaluable assistance through our discussions about the framework of the study, the peculiarities of France and its politics, and his own experience in Italy, He later provided detailed criticism of my drafts that helped me re-work and refine the raw 'trial runs’. In terms of research, I owe a great debt to Pierre-Marie Giraud of Agence France Prcsse in Paris for his patience, kindness and openness, I had a free run of all AFP documentation relating to Action directe. Without his assistance, my research would have taken much longer and been less complete.

While conducting research and writing in France between 1986 and 1990, I was able to discuss my work with several persons whose views helped me understand AD’s significance: Professor Alfred Grosser at the Institut d’etudes politiques de Paris; Daniel Hermant, director of the Institut frangais de polemologie at the Hotel National des Invalides; Professor Franqois Furet, director of the Ecole des hautes etudes en sciences sociales; and Dominique Rohn of Les Editions du Seuil. I also greatly benefited from the thoughtful comments of Dr Kenneth Robertson of the Graduate School of European Studies at the University of Reading and the encouragement of Professor Paul Wilkinson of the International Relations Programme at the University of Aberdeen. Dr Robertson and Professor Wilkinson read an early draft of Chapter 5 that was later published in Terrorism and Political Violence.

The gestation of my research pre-dated my travel abroad and graduate studies. Dr Claudia Wright of the Department of Political Science at the University of Winnipeg provided intellectual and personal inspiration and infected me with her interest in revolutionary movements. Dr Arthur Kroker, now at the Department of Political Science at Concordia University, stimulated my interest in political theory and intellectual audacity. Arthur provides students with an intellectually stimulating environment and a sense of freedom of the life of the mind. Dr IL Vincent Rutherford,

now retired from the Department of History' at the University of Winnipeg, became a good friend, teacher and firm advocate of[4]Operation Bootstrap’ (it works, Vince!). Dr Randi Warne of St Stephen’s College at the University of Alberta is an old friend with a sharp intellect and great sense of humour who said: ‘Hey, why don't you study one of those groups anyway?’ In addition, I would also like to thank Dr Shannon Bell and Dr Gad Horowitz, Francois-Pierre Le Scouarnec, Pcta Mathias, Barbara Shearer, Joanna Barker, Hugh Cawker, Marion Brcdin, Tamara Crist, Laurent Le Floch and Sheila Block for support, advice, patience and encouragement

I would also like to thank the institutions that provided me with financial support at various points in the time that led up to the present text* The University' of Winnipeg provided a bursary' and teaching assistantships from 1977 to 1979. The Birks* Jewellers Family Foundation paid my tuition fees from 1977 to 1987. The Faculty of Graduate Studies at York University' supplied assistantships during my residency. The Canadian Department of National Defence granted a scholarship that allowed me to travel to France for initial research from April to July 1984. Hitch-hiking through Provence, Languedoc-Roussillon, Midi-Pyrenees, the Massif Central, the Loire Valley and Brittany may not be a classic research method, but my knowledge of French language and culture grew on this foundation. York University’s Lamarsh Research Programme on Violence and Conflict Resolution also provided a grant to travel to France. Dr Desmond Ellis, then Lamarsh director, encouraged me to go ahead with the project* Columbia University’s Council for European Studies gave a small grant to attend its biannual conference in Washington DC in March 1990 and present a paper onzfrt/tw directs

Finally, I would like to thank Martin Chochinov, who has nurtured many more things than he perhaps realizes. His intellectual acuity, emotional centredness and proof-reading spurred me on in the final stages.

Montreal, 18 March 1993

Abbreviations

A2 - Antenne2

AD - Action direct?

ADi - Action direct? international?

ADn - Action direct? national?

AFP - Agence France Press?

AR - Affiche rouge

ATIC - Association treA/ri^ue de /’importation charbonniere

BNP - Banque national? de Paris

BR - Frigate Posse

BRB - Brigade de repression du banditisme

BW - Black War

CCC - Cellules combattantes communistes

CDP - Cause du peup/e

CFDT * Confederation fran^aise democratique du travail

CGT - Confederation generale du travail

CIRPO - Conference international? des resistances cm paj[j]s occupes

CLER - Comites de liaison des etudian/s revolutionnaires

Clodo - Comi/e liquidant ou dctoumant les ordinaleurs

CNPF - Conseil national du patronat franfais

CPSU - Communist Part}' of the Soviet Union

DPS - Detenusparticulierement signales

DST - Direction de la surveillance du territoire

EEC - European Economic Community

ESU - £/udiants socialisles unifies

FAHR - Front arm? honiosexuel revolutionnaire

FARL - Fractions armees revolutionnaires libanaises

FEB - Federation des entreprises beiges

FER - Federation etudiante revoluiionnaire

FHAR - Front homosexuet d'action revolutionnaire

FN - FrorH national

FRAP - Front revolutionnaire d’action proletarienne

FTP - Francs-tireurs partisans

GARI — Groupes d action revolutionnaires internalionalistes

GBGPGS - GroapeBai’oanfne-GdawsA’-Faris-CaafewaZa-Sa/wdor

GIGN - Grouped’intemmtion de lagetidannerienatioJiale

GP - Gauche proletarienne

GRB - Groupe de repression du banditisme

INLA - Irish National Liberation Army

JCR feunesse commtiniste revolutionnaire

LCR - Ligue communist# revolutionnaire

LO - Lutte ouvriere

MIL - Mouvement iberique de liberation

MLF - de Liberation des Femmes

MPPT - Alo/awtenZ tin parti des travai Hears

MRP - Afonvemen/ republicain populaire

NAPAP - Noyaux armes pour l’autonomiepopulaire

NRP - Nouvelle resistancepopulaire

OCI - Organisation communist# intemationaliste

ONI - Office national de rimmigration

PCF - Parti communist#fiangais

PCI - Partita Communisto Italiano

PCMLF - Parti communiste mamste-leniniste de France

PCR - Parti cotnmiinisie r&o/utionnaire (marxiste-lemnisle)

PS - Parti socialisle

PSU - Parti socialist# unifie

RAF - Rote Anne Faktion

RG - FmeignemenZs generaux

RPR - Rassemblementpour la Repttblique

SAT - Societe Anonyme de Telecommunications

SEMIREP - Societe mixte de renovation du quartier Plaissance

SFIO - 5m/o»yron^se de Z7n/en^Zio?z^/e o^riere

SONACOTRA - Sodete National# de Constructions pour les Travailleurs

TGV - train de grande vitesse

TRT - Telecommunications radioelectriques et telephones

UDF - Union pour la democratic franfaise

UEC - Union des etudiants communistes

UEO - Union de LEurope Occidental#

UJCml - Union des jennesses rommunistes - mams/es-ieninisres

UNEF - Union nafionate des etudiants fran^ais

L'TA - Union des transports aeriens

VLR - Five la revolution

1 Interpreting Terrorism: A Case-study of Action directe

'Brothers, when the time of triumph comes, with good fortune from both worlds as our companion, then by one single warrior on foot a king may be stricken with terror, though he oivn more than a hundred thousand horsemen?'[1]

The following study centres on explaining the emergence of a violent revolutionary protest faction in a stable Western political system. The explanation focuses on the group Action directe (AD), which was active in France between 1979 and 1987. It will demonstrate that AD’s ideology’ was based on rational motives that were derived from a reading of the context. In general, this analysis outlines AD’s values and goals to ‘take into account the sense that the actors themselves give their actions, and the constraints or norms (even if they are monstrous) to which they are subject'.[2] The discussion will also show that AD’s rational character did not help the group achieve the ends it set for itself. Most existing literature on terrorism does not help us understand AD since, by attempting to ‘generalize’ and compare, it is too broad to account for the specificities of one case. The French context is moreover extremely problematic for analyses based on the assumption that terrorism is a sign of instability'. France is a stable democracy in which violence appears on an episodic basis.

Several conclusions about the problems in the literature on terrorism guide this discussion. First, a general explanation of terrorism is not considered possible at this time since the analytical value of the term is limited and not applicable to a wide range of phenomena. ‘Terrorism’, as Jenny Hocking points out, has a general character that deters effective differentiation and explanation:

Terrorism is not a neutral or purely descriptive term. In die sense that its understanding is based on perceptions of legitimacy structured according to a bench-mark of political and social ‘normality’, ‘terrorism’ is an ideological construct.[3]

In the second place, this discussion is guided by the view that case-studies, not existing analyses of terrorism, are the most promising path towards a satisfactory examination of the significance of terrorist violence* To this end, the text focuses on a case that superficially resembles the so-called terrorist threat, but that is in fact quite different: AD was more endangered than were French institutions or society* Third, this text views an examination of motives as an effective means to explain ‘unpredictability’, a factor that is often cited by analysts of terrorism. Terrorists may articulate rational bases for action. In view of the fact that AD carefully articulated its motives and its attacks expressed goals,

A narrow perception of terrorism as essentially indiscriminate would consequently remove assassinations and the murder of specific ‘symbolic’ individuals from the realm of terrorism . . . much of the activities of terrorist groups . * . (have) been built upon a selection of targets chosen specifically for their position within the political and economic systems.[4]

Fourth, the discussion views the treatment of revolutionary terrorism as an aberration to be a misapprehension that equates ‘political violence with a single form of such violence - terrorism; and then implies, or assumes, that all terrorism is “revolutionary” or “aimed at the overthrow of governments”?[5] Finally, the text regards labelling terrorism as ‘indiscriminate’ to be missing the point The assumption implies that ‘terrorism’ has a single definition and ignores how violence ‘must be highly discriminate in order to provoke the type of response desired'?[6] Neglecting motives, obsession with left-wing revolutionaries, ignoring state terrorism and fixating on the arbitrary and random are all endemic to the literature on terrorism.

The development of a general theory of terrorism would certainly help to improve social science treatment of political violence in general. However, such a possibility is not imminent. The state of social science knowledge of many kinds of ‘terrorist’ groups is so limited that even comparisons between the so-called ‘Euro-terrorists* of the 1980s is hampered by lack of careful observation* What is known about the Italian and German wings of the phenomenon, especially that they emerged from broader social movements, immediately distances them from AD. Today’s analyses most often dissect terrorism into components that are compared across contexts. The resulting cross-casc analyses of specific aspects of terrorist violence hinder the development of a general theory because they fail to provide ‘frames of appreciation, cognitive maps, concept packages, and methodology' to comprehend complex phenomena that cannot be understood through decomposition into easier-to-analyze subelements’?[7] In the worst instances, analysts denounce terrorists as psychopaths, qualify their violence as new and extraordinary, and characterize terrorism as episodic, dysteleological, incoherent, abnormal and unacceptable. ‘Terrorism’ is characterized as ‘omnipresent’ and specific threats are rarely described as manageable or less than catastrophic. If incidents are unprecedented, analytical attention should turn to the ‘sets of ideas ..[that] . . . posit, explain, and justify ends and means of organized political action, irrespective of whether such action aims to preserve, amend, uproot or rebuild a given order’.[8] If the effects of terrorism are unpredictable, examining the motives in a specific case might help explain why this is so. An examination that focuses on a revolutionary political faction (AD) in a stable Western society (France) circumvents the problems inherent in interpreting terrorism. Procedures based on simplification and comprehensive approximation are premature since few individual incidents of ‘terrorism’ have been sufficiently examined. The resulting analyses are theoretically impoverished, lack contextual substantiation, exhibit poor taxonomical development and generalize on the basis of insufficient data.

At an early stage of theory-building, intensive examinations have limited applicability: ‘a single case can constitute neither the basis for a valid generalization nor the ground for disproving an established generalization’. Accordingly, the present study identifies the peculiarities of one group in order to respond to the lack of contextual research, poor taxonomical development and premature generalizations in existing literature. It draws its force from the fact that ‘intensive study and empathetic feel for cases provide authoritative insights into them’.[9] By isolating one example and avoiding comparison, the examination is a ‘basic data-gathering operation, and can thus contribute indirectly to theory-building’ ?° Rather than trying to define regular relations between cases, the study aims to formulate hypotheses for subsequent interpretations[11] The interpretation is in this sense ‘hypothesis-generating’ since it provides contextually specific ‘generalizations in areas where no theory exists yet’.[12] Although AD is not necessarily comparable with other cases, the study may ‘uncover relevant additional variables that were not considered previously ... or refine the definitions of some or all of the variables’?[13] Owing to the lack of well-researched examples to compare, examining one case is a research strategy that may

stimulate the imagination toward discerning important general problems and possible theoretical solutions . . . [It] ties directly into theory-building, and therefore is less concerned with overall concrete configurations?[14]

However, at the same time, a case approach does have limits, especially in relation to conspiratorial political factions. The latter are by definition difficult to examine since they operate without the mass relays that characterize contemporary Western political behaviour. Given the difficulties in observing a conspiratorial political faction like AD on a firsthand basis, the method selected for this study focuses on an ideological framework and symbols that ‘legitimize in morally unquestionable postulates the predatory use of such bargaining weapons as groups possess’.[15] AD used ritual violence as a way of symbolically communicating its goals and views to the French political system. These symbols are closely related to politics since:

every political act that is controversial or regarded as really important is bound to serve in part as a condensation [summarizing] symbol. It evokes a quiescent or an aroused mass response because it symbolizes a threat or reassurance,

Symbols are tools that distinguish ‘complex and undifferentiated feelings and ideas, making them comprehensible to oneself, communicable to others, and translatable into orderly actions’.[17] In AD’s case, metaphors such as ‘capitalism’, ‘revolution’, and ‘crisis’ gave its acts coherency, orientated strategies, and connected its ideology to French political traditions. The general orientations set by French political history are crucial to understanding AD. As in all political cultures, French ideologies are:

sets of attitudes, beliefs, and sentiments which give order and meaning to a political process and which provide the underlying assumptions and rules that govern behaviour in a political system. It encompasses both the political ideals and the operating norms of a polity ... A political culture is the product of both the collective history of a political system and the life histories of the members of that system. * ,[18]

Like other Western political organizations, AD used ideology in a ‘struggle to embody a new politics and a new society’.[19] However, unlike other political groups, it infiltrated the dominant symbolic order in an effort to ‘sacrifice’ the system and employed symbols for their ‘drawingtogether, intensifying, catalysing impact upon the respondent’.[20] Its ‘ritual’ violence is thus best explained in political-ideological terms that clarify ‘political acts remote from the individual’s immediate experience’.[21] These terms help to avoid the assumptions that human behaviour is uniform, that violence always has similar results, and do not ignore different intensities, types and meanings. Traditions and symbols help to delineate AD’s attempt to ‘relate lower-order meanings to higher-order assumptions, or to “ground” more surface-level meanings to their deeper bases’.[22] In the following discussion, AD’s ideology will be set in the context of extremeleft traditions that structure ‘particular culturally provided sequences of stylized actions’.[23] Extreme-left traditions shaped a revolutionary ideology in which attacking capitalist collaborators was conceivable. The persistence of these traditions in French history encouraged AD’s belief that it had a potential following and was providing a needed protest function. Accordingly, the group’s vocation was based on themes that the extreme left had discarded. This vocation effectively made the group a degenerated version of gauehis me.[24]

The weaknesses in the literature on terrorism are obvious in several of the approaches frequently employed. Psychological interpretations have been widely used. They are often based on theories of frustrationaggression and relative deprivation, although neither theoiy is now used widely by psychologists. Frustration-aggression theory is based on the idea that ‘aggressive behaviour always presupposes foe existence of frustration and, contrariwise, that the existence of frustration always leads to some form of aggression’?[25] Rather than verifying the claim by referring to specific cases, analysts have developed an approach that allegedly illustrates the deviant nature of political terrorism. Lawrence Freedman argues that frustration leads terrorists to believe that violence releases superhuman and extra-normal powers?[26] Frederich Hacker says they are deeply disturbed, non-political ‘justice collectors seeking remedy for injustice by unrestrained legitimation of all means used in the sendee of their cause’?[27] J. W. Clayton claims that frustration makes terrorists vulnerable to defeatism and leads to ‘overly high expectations of an idealized order’.[28] Other analysts use relative deprivation theory to balance the psychological bases of frustrationaggression theory with sociological insight. Ted Gurr argues that social conditions may amplify conflict if they raise expectations without increasing foe capacity to fulfil them?’ Gurr’s relative deprivation theory focuses more squarely on motives and rational concerns than does frustrationaggression theory. However, it offers no substantive explanation of significance because it lacks reference to active terrorists?[30] Although examining active terrorists might confirm its claims, the explanatory value of frustration-aggression theory is now limited by difficulties such as participants’ memories, their ‘editing' of events and accounting for conflicting motives.

Another set of theories is based on a systems theory approach. These analyses view terrorism as a product of poor normative integration and inadequate government response to social problems. Yezekiel Dror says an ‘inadequate institutionalization of inputs’ leads to violence. He argues that democracies must learn to respond to extra-normal pressures that are ‘both a danger of failure with immediate and long-term consequences and an opportunity to re-assert the requisites of a viable democratic capacity to govern’.[31] Similarly, Chalmers Johnson argues that terrorism results from 'the degree and nature of a social system’s dissynchronization and of the quality and timelessness of the efforts of its ruling elites to rectify the dissynchronization’?[32] However, he adds that where 'moral communities’ shelter individuals from random violence and supply clear social roles, terrorist violence is ‘a form of tyranny, not something to which people can become accustomed and thereby orient their behaviour’?[33] Another systems approach argues that terrorism results from a weak international order and the influence of non-Western values. These analyses allege that state intervention and international support underpin modern terrorism?[34] Claire Sterling, for example, contends that the USSR assisted ideologically amenable terrorists during the 1970s and 1980s: 'the whole point of the plan was to let the other fellows do it, contributing to Continental terror by proxy’?[35] Her rhetoric exaggerated the threat and was not based on systematic evaluations of cases. In many contexts, terrorism has not threatened democracy or international order?[36] Some analyses argue that modem terrorism has especially lethal potential because contemporary democracies have loosened social control. They advocate limited access to communications, transport, weapons and information technologies as a way of preventing nuclear or 'hi-tech* terrorism?[37] Other analysts argue that terrorism exposes the dangers of open, reasonable responsive democracies. Yonah Alexander argues that by providing information and ways to attract attention, equal access and pluralism increase the potential for violence?[38] His explanation stresses the irresponsibility of techno-terrorists and assumes that all governments use technology responsibly. However, it seems unlikely that terrorists would annihilate the political system with reference to which they articulate demands.

Another category of theories focuses on rights and ideologies. The best-known analyst of this school is Walter Laqueur, who links terrorist violence to socially transformative ideologies. Laqueur’s analyses set the paradigm for most literature on terrorism. He argues that the modern and left-radical variant of terrorism in many ways resembles tyrannicide, regicide and revolutionary conspiracy. Laqueur agrees with Anthony Quainton’s view that modem terrorism’s unrestrained behaviour, indiscriminate targeting, multinational networks and failure to attack dictatorships make it a refinement on age-old tactics of intimidation, intrigue and assassination?[39] In this light, Laqueur believes that examining motives is not important:

’left-wing’ and 'right-wing* terrorism have more in common than is usually acknowledged. Terrorism . .. was Fascist in the 1920s and 1930s but took a different direction in the 1960s and 1970s. In actual fact, however, underlying both ‘left-wing’ and ‘right-wing’ terrorism there is usually a free-floating activism - populist, frequently nationalist, intense in character but vague and confused.[40]

Irving Horowitz echoes Laqueur’s attitude toward motives. He says treating “radicalism” as a rerival of participatory democracy' and “terrorism” as a simple resort to violence is to miss the essential multinational mix'.[41]

Several other theories of rights and ideologies do assess the significance of motives. However, these interpretations also define ‘terrorism’ broadly and make sweeping generalizations about post-1789 Western politics that render specific contexts superfluous. Noel O’Sullivan says that terrorism is a consequence of the ideological politics that emerged during the French Revolution: ‘the modem enemies of limited politics never appear in that role but always present themselves as the champions of “the people”, of “true liberty”, and of “true democracy”’[42] His view is similar to that of Hannah Arendt, who argues that de-sanctifying the human values underlying Western law led to violence and threatens individual rights: ‘ the means overwhelm the end. If goals are not achieved rapidly, the result will be not merely defeat but the introduction of the practice of violence into the whole body politic.’[43] Paul Wilkinson also examines motives. He calls terrorism ‘inherently indiscriminate’, ‘essentially arbitrary and unpredictable’ and a denial of‘all rules and conventions of war’. He links terrorists’ ‘hideous and barbarous cruelties and weapons’ to motives such as transcendental ends, regeneration, catharsis, just vengeance or greater evil.[44] Wilkinson says these motives reflect the influence of Jean-Paul Sartre and Frantz Fanon, ‘philosophers of terrorism’, whose

almost mystical view of violence as an ennobling and as a morally regenerative force has been widely diffused among revolutionary intellectuals. So too has their advocacy and championship of terrorism, Sartre claims that revolutionary violence is ‘man re-creating himself.[45]

Similarly, Moshe Amon claims that terrorism emerged from the ‘ramshackle world of Western civilization, where religion is in a state of crisis and many established myths are losing their meaning and significance’.[46] He says that violence results from our civilization’s loss of coherence and continuity.

Overall, explanations based on assertions about long-term tendencies that affect modern Western civilization do not provide an effective framework to examine specific details or contexts. In particular, they provide no basis to explain violence that is non-revohitionary, provocative or protestoriented. Since generalizations draw their persuasiveness from a comparison of cases, the latter type of violence needs substantiation through research on specific examples[47] The above literature does not proceed in this fashion. It is based on an indiscriminate identification of‘terrorism’ across diverse settings that obscures difference. In so doing, it ultimately hinders explanation by failing to distinguish typologies that are ‘different from every other, both in content and in organization’[48] A comparison of cases should be preceded by research on factors such as ideology, history, international conditions, and organization. Without these foundations, the above theories explain the impact of terrorism better than they evaluate its significance. A general explanation would have to account for the different results shown by a cursory examination of apparently similar cases. Uruguayan terrorism, for example, led to ten years of military authoritarianism. The Italian extreme-leftists who emulated it actually helped to strengthen democracy. A general theory would help explain why democracy was strengthened in one context but weakened in another. It would also account for groups that do not try’ to overthrow governments. Beyond this, the wide variety’ of cases throws the possibility' of formulating a satisfactory general theory into doubt. Ignoring such issues, most analysts link terrorist violence to the unexpected. Laqueur contends that modern terrorism ‘is directed almost exclusively against permissive democratic societies and ineffective authoritarian regimes’/[49] His comparison ignores context and the relative rarity of truly lethal terrorism in Western democratic systems.

Not all the literature on terrorism is hampered by broad generalization. Some analysts have provided insights that were used to develop the approach employed in this discussion. In particular, the approach is based on Furet’s argument that the threat of violence seems palpable; ‘where power is abstract, government occurs through impersonal norms, and complex procedures exist to substantiate a popular presence, the terrorist substitutes the concrete universe of incarnated power/[50] This study is also informed by Edwy Plenel’s view that examining motives and ideology may help ‘take the exact — social, political, ideological - measure of the phenomenon'.[51] Peter Merkl, by responding to the weakness of general explanations with specificity, helped substantiate Plenel’s general statements. Identifying five types of violent groups in Weimar Germany,[52] he notes that ‘lumping them together in one category of violence against feeble public order is not very helpful . .. attempts at revolutionary uprising ... [are] . . . obviously different from assassinations and call for different approaches’.[53] In addition, this discussion was substantially aided by Hocking’s criticism of existing theory and Robin Wagner-Pacifici and Robert Drake’s case-studies of the Italian Red Brigades (BR)/[54]

The single greatest weakness in social science treatments of political violence is the lack of conceptual tools. Particularly marked at the level of taxonomical categories, this failing has retarded theoretical development. Although the violent factions we refer to as Terrorist' have long plagued political life, they have rarely been systematically examined due to two factors. In the first place, mass movements, representative government and democracy are the central concerns in modern Western political thought. Factional violence was always discussed in classical political thought, but largely written off as an anomaly after the late eighteenth century. Secondly, as AD itself illustrates, the secretive character of small conspiratorial groups does not lend itself to systematic examination. AD’s small size, lack of mass support and emphasis on elite action made it more like a pre-modern political faction than the formal-legalist organizations that preoccupy modern political science. As a result, analyses of terrorism are methodologically crippled.

The weakness of most analyses has been exacerbated by confusion over the term ‘terrorism’, In most analyses, Terrorism’ is defined as a technique: 'the use or threat of violence to effect change in the body politic’?[55] However, applying the definition to a wide variety of undifferentiated phenomena ignores differences between cases in favour of general explanations that cannot sustain close scrutiny. As a result, the types of political violence incorporated under the rubric Terrorism’ include: the Jacobin terror, suppression of the Paris commune, Russian nihilism, Nazism, the Algerian FLN, the Khmer Rouge and the Lebanese Hezbollah. The vocabulary to differentiate them remains underdeveloped. Beyond indicating that violence is employed to secure generally political goals, Terrorism’ cannot help explain the significance of particular organizations in specific environments. In some cases, violence seriously menaces socio-political order. In others, its impact is symbolic rather than lethal. Despite this, many analyses persistently view Terrorism’ as a threat to the state, ‘the primary symbol of political legitimacy, the focus of popular loyalties, and the basis of international order’[56] The seriousness of this claim dictates that it be validated with reference to specific goals, motives and context. In all its incarnations, Terrorism’ needs to be distinguished from officially sanctioned violence. The latter is allegedly manageable, manipulate and ‘nothing but the continuation of policy with other means’[57]

Violence is a regrettable, inevitable and persistent part of the Western tradition. Many forms of violence are sanctioned by the distinction that Judeo-Christian culture imposes between social and political violence. The separation disempowers specific groups and, for example, makes violence against women, homosexuals and visible minorities routine. In contrast, ‘political violence’ draws attention because it attacks patriarchal order. Research on family abuse, sexual violence and peace studies is now extending knowledge about violence. However, this research does not show that violence is increasing, only that its depth and range are finally being systematically examined. Analogous gaps in historical knowledge hampers many examinations of social and political violence. Extended social sendees and communications, for example, have unveiled previously tolerated sexual and family violence. However, the lack of long-term information about these phenomena limits evaluation in the same way that the lack of attention given 'terrorism[57] impedes general explanations of significance and character, What can be said is that the impact of'terrorism’ outstrips that of home, school and workplace violence.[58] Yet, theories of terrorism generally do not distinguish typologies of violence. They characterize a wide selection of types of violence as lethal and so amalgamate terrorism with cataclysm. In fact, the threat can only be clarified by surmounting‘continuing confusion about its [terrorism’s] general significance for modem political life, and in particular about its relationship to the democratic states?[59] The task could begin by distinguishing a range of types (fascist, neo-Nazi, Marxist-Leninist and anarchist) and demonstrating the significance of national symbols.[60]

The ultimate impact of terrorist violence lies in its violation of Western beliefs about democracy and representative institutions. This impact overwhelms our knowledge that ‘terrorism’ in the West is infrequent by comparison to the rest of the globe and other historical periods. Many analyses confound ‘terrorism* with ‘civil unrest’, ‘protest’ or ‘sabotage’, even though the threat is not especially lethal:

the number of Americans killed inside the United States in 1985 as the result of terrorist attack was two ... the total number of US civilians killed abroad between 1973 and the end of 1985 was 169 ... more Americans were killed by terrorists in 1974 (22) than in 1984 (16)?[1]

Examinations tend to ignore that ‘the actual amount of violence caused by international terrorism has been greatly exaggerated. Compared with the world volume of violence or with national crime rates, the toll has been small’?[2] Terrorism has an intense, non-physical, emotional and abstract impact, but this does not necessarily mean that individuals or society are vulnerable. In France, terrorism is a small portion of criminally motivated deaths and injuries.[65] Although the average French person is more likely to be raped, robbed or injured on an expressway, terrorism elicits a strong public reaction because it violates symbols of everyday continuity and security.[64] Terrorism leads to a sense of insecurity that arises from ‘an identification with the fate of actual victims to the extent that victims are interchangeable, but does not stem from an analysis of the statistical frequency of attacks’/’[5] However, a widespread impression that French society is increasingly violent has been accompanied by,

a significant regression in criminal violence . . . the evolution of violence has not at all followed the dramatic course that the dominant alarmist discourse would lead us to suppose ... the frequency of murders and assassinations is extraordinarily weak; the mortality rate due to homicide is about one for every' one hundred thousand persons (in traditional patriarchal societies, the rate was as much as fifty[r] times higher).[M]

AD has been selected for examination precisely because it is a case in which terrorists threaten socio-political order or indicate significant system dysfunction to a much lesser degree than initial impressions suggest.[67]

Method

This discussion focuses on one case of political violence in a Western system in order to discuss its rational bases and political character. AD is ‘rational’ in the sense that it consciously chose to behave in a certain manner derived from historical antecedents such as blanqutsme** The discussion begins with an overview of French political history' in order to show that political violence is a chronic element in that context. After this, the analysis shows that AD’s motives and goals follow French revolutionary’ traditions. The group was trying to carry' out a protest ‘role’ finked to changes that were under way in French political culture in the 1970s and 1980s. These alterations turned AD’s revolutionary project into a parody since its goals were not relevant to public debate. As a result, AD failed to menace political order and remained a fringe phenomenon. The recourse to a case approach thus reveals the group’s contradictory' status: AD was not a lethal threat to France’s socio-political order, but drew' on a long tradition of violent opposition to the establishment of the day.[69] The triple focus of the study is designed to avoid the pitfalls of existing analyses. The discussion concentrates on: (1) contextual information and specificity'; (2) political changes that set the scene for violence; and (3) the character of one organization. The first section outlines the French revolutionary' traditions that reduce politics to physical struggle and provided numerous, and recent, precedents for a rational course of action. The context set the stage for forms of political violence that are either strategic or tactical. While tactical violence secures specific ends, such as national security, independence or revolution, AD used violence strategically, It viewed force as an end in itself and aimed to create fear.

The specificity of AD’s case does not provide hypotheses to test against other examples or measure equivalency.[70] As a result, this analysis does not offer a generic explanation of political violence. The exclusive focus on French political traditions elucidates specific debates and influences. The single-case approach isolates the themes that help to substantiate AD’s rationality, such as extreme-left debate on how to battle capitalism. The approach, which made this highly specific ideological interpretation possible, was selected as the only methodology that could clarify the centrality of ideological motives for political violence in France. Ideology is the key that clarifies how AD used 'premeditated and purposeful violence ... in a struggle for political power[1].[71] AD’s goals and motives were motivated by a distinct political tradition[72] that is imbued with universalist values and reflects a unique historical experience. France is one of few Western political cultures that continues to view values derived from a specific historical experience as universally valid. The sense of historical-cultural superiority' that imbues France is another element that makes it difficult to compare AD to its fellow ‘Euro-terrorists' in Italy and Germany. In the latter two cases, the experience of fascism provided a markedly different set of conditions and attitudes toward the political system. AD’s choices were shaped by a political culture in which symbols, legitimacy and institutions emphasize

departure from men’s daily routine, a special or heroic quality in the proceedings they are to frame. Massiveness, ornateness and formality[1] ... are presented upon a scale which focuses constant attention upon the difference between everyday life and the special occasion.[73]

AD emerged in a period in which ideologies were changing and political consensus growing. The alteration was a highly significant one in twentiethcentury' French political history'. It was embodied by the Mitterrand presidency, a focus on the EC, racism, immigration and the social power of money, and expressed by terms such as altemance, cohabitation and

Like the extreme-right Front national (FN), AD believed that the shift was a threat to an authentic set of national values. Both groups feared marginalization, distrusted politicians, were deeply anti-American and tried to exploit racism, anti-immigrant sentiments and fear of EC integration.

This discussion characterizes AD as an extreme-left protest faction with a revolutionary vocation. The group contradicts many assumptions about violent political organizations in the literature on terrorism. Accordingly, this text argues that the group is always very left-wing and very French, which limits the possibilities for comparison with other seemingly similar samples. Rather than focusing on comparison, the argument concentrates on a political micro-culture, its meanings, and transmission of the central elements of those meanings from a more ‘elaborated’ host political culture. The resulting discussion focuses on how AD concluded that armed opposition was necessary, evaluates its threat and goals, and aims to elucidate a taxonomical category. AD’s early attacks were a symbolic protest. Deadly assaults on human beings only became systematic after five years of operation. Early AD (1979-82) was preoccupied by the proletariat. Later, /letion direct? national? (ADn) was preoccupied by national issues and behaved like a group of politicized criminals. Tirtrcw direct? international? (ADi) had an international orientation, methodically assassinated individuals and wanted to ‘reconstitute’ the proletariat at a global level. Both sections mirrored French society and, significantly, did not deviate from national ideological-political themes. As a unit, AD recapitulated national ideological traditions. It even split due to differences over national and international influences that also divided the mainstream left. Both ADs believed that revolution was historically necessary and inevitable and that human productive and technological capacities made egalitarianism a social and political imperative. To achieve its end, AD targeted a new global order. It was inspired by May 1968, the wartime resistance movement and French extreme-left traditions, but failed to attract a pool of like-minded groups. Their absence doomed AD’s emulation of May 1968 and made it anything but a ‘popular force’. ADi tried to circumvent this weakness by posing as an early stage of revolutionary struggle, However, it appeared just as exlra-parliamentary organizations lost steam and the mainstream left rose to power.

2 French Traditions of Political Violence and Protest

The following discussion clarifies the bases for the direct action tactics that AD adopted by outlining the main contextual factors that shaped its stance toward the host political system: the revolutionary tradition in French politics; the 'classic’ political order of the Third Republic; and the Fifth Republic consensus. All three influences provided the foundations upon which extreme-left terrorism took root in the late 1970s. Through an outline of these influences, the rise of extreme-left terrorism can be referred to French concepts of political legitimacy, the Actors, objectives, capabilities and certain stable aspects of the environment that attend the application of capabilities’? As a result of the above influences, AD adopted a revolutionary 'vocation’ that was explicitly linked to protest traditions and a distinct idea of legitimacy. Revolutionary opposition to the political establishment has in fact long functioned as an unexceptional component of the 'exceptional’ political culture formed through France’s original and complex history.

The influence of the 1789 revolution

Distinct geographical, historical and cultural influences shaped France’s political traditions. At the most fundamental level, a history of strong central authority shaped protest against a state that usually functions as 'no mere instrument of a sovereign general wall nor an arbiter among people but a positive good in itself, the bearer of values greater than the sum of individuals who made it up’.[2] The political system made little provision for independent cultural, social or political organization. Post-revolutionary institutions moreover generally embodied very specific notions of prestige, education and status:

The bourgeoisie triumphed through a battle, and the battle explains both the continuation of industrial development as an element of bourgeois drive and the energy with which the bourgeoisie defended itself against any push from the new lower class, the proletariat. The aristocracy has offered a long and heated resistance: hence both the bitter cqualitarian suspiciousness which pervaded French society and the deep impact which the aristocratic values nevertheless made on the bourgeoisie and even on workers’ attitudes?

The dramatic break of 1789 rendered all subsequent political regimes prey to revision by revolution* Without the unifying symbol of a monarchy, both right and left traditionally viewed legitimacy as conditional and historical, an attitude that endowed public life with a radical capacity that AD believed it could still exploit in the 1980s. In the traditional political culture, both ideological camps also bore mutually exclusive concepts of legitimacy that

are fundamentally built on the opposition betw een the partisans of a hierarchical society and the supporters of an egalitarian one ... a main line in French political life, even though its criteria evolve and the equilibrium varies.[4]

In French political culture, Anglo-American reformism has long appeared as one stance among a group of alternatives. Political struggles were often resolved by force in the nineteenth century. Both the extremeright and extreme-left repeatedly used violence to secure their interests and make themselves heard.

From 1789 to 1914, no government is acceptable for all citizens. Two irreducible legitimacies confront one another. A large part of the country remains faithful to the monarchical principle of the old regime: it wants a king who could take up again the dynasty that was driven from the throne in 1792. Another part is impassioned by the new principle of national sovereignty: it calls for power based on universal suffrage and public freedoms. They slaughtered each other as much for political regimes as class interests/

Despite the association of revolutionary change to the year 1789, the victoty of republicanism over its anti-republican and ultra-royalist opponents did not occur until about 1880. Many parts of the left were by this point deeply suspicious of the political establishment and the practice of compromise. For its part, the right did not trust left-wing intentions, and focused on the example of the 1793-94 terror:

The two camps were not only opposed over national management and development, but also over fundamental values. Between the Enrages ['fanatics’] and the Ultras ['ultra-royalists’] there was no common ground, only a mutual wish to finish one another off?

The left was locked out of power and actively persecuted in 1794,1815, 1848 and 1871. When it did form a government, it tended to turn on its enemies.[7] The radical dichotomy between right and left that AD later insisted upon was hardly aberrant. On the contrary, it has been one of the most persistent features of the post-1789 political culture. At the same time, French society remained ‘profoundly conservative in its modes of organization and its models of human relations . . . with a taste for revolt and a long tradition of utopian protest[1] .* The centralized state inherited from the old regime and reinforced by Napoleon combined with revolutionary predilections for political utopianism. Public institutions were fragile, and became even more so if the status quo did not entail sociopolitical advantage for certain political players. As AD did later, frustrated groups turned to sustained, rhetorically radical, and physically violent protest. Dramatic action, a method legitimated by the revolution, became a favourite tool for testing the strength of the authorities? If the state could not reinstate order, participants demanded better institutions. The resulting political culture was characterized by:

addiction, not merely to revolutionary talk, but to violence (to a degree considerably superior to what could be found even in industrial relations). In other words, the degree of willingness to observe the rules of the game when results fail to give satisfaction to the claims of the ‘political strata’ is low?[0]

Post-1789 French political culture was also influenced by the ideas of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. In particular, his focus on the allegedly direct democracy in the Greek nourished the ideal of a small, self-sufficient republic based on untutored participation. Nostalgia for organic community links and the consensus loss after 1789 led to the use of classical Greek symbols to legitimize authority. Rousseau’s ideas were also translated into policy. The Comite du salut public" prescribed the creation of rational social and political institutions: ‘in the interest of the people the state was to be interventionist, offering social services; it was to plan and guide the institutions of the country, using legislation to lift up the common man’.[13] The principles in the Declaration des droits deThonme™ were to be secured by education?*

Utopian egalitarianism thus had long-term influence on attitudes toward the political system. A split between left-wing advocates of liberty and equality in the 1790s further multiplied ideologies. Both wings of the left thereafter spread ideas that synthesized wnth traditionalist and modernist social concepts in an ambiguous manner:

France is perhaps the only country' in Europe that never really accepted the great break, the great intellectual, scientific and political reversal carried out in Enlightenment Scotland toward the end of the eighteenth century, a reversal that wanted itself to be-and really was - the birth act of modernity. Economic science, utilitarian philosophy and the political theory of liberalism all appeared at this time.’[5]

In France, left-wing movements based on libertarian and egalitarian ideas competed with other groups that had traditionalist values. Left-wing nostalgia for a small-scale political order resulted in ambiguous attitudes toward religion, the family, mass migration, political representation, technology[7] and urban industrialism. By referring authority' to a romantic vision of the classical Greek city[7] states, revolutionaries tried to create a consensus, However, this classicism was hardly ‘modernist* since the economic, social and cultural management of an imperfect, changeable and unacceptable nature contradicted the static equilibrium of the smallscale republic. The juxtaposition of tradition and modernization with liberty[7] and equality[7] greatly influenced perceptions of legitimacy?[6]

The 1789 revolution spawned a group of ideologies: jaabimsme, bonapartisffle, u/tra-roj'a/fcme, orlfanisme, b/anquiswe, socialism and republicanism?[7] These ideologies were not always easily distinguishable. Bonapartism, for example, blended rightand left-wing elements into an imperial style, foreign adventures and populist grandiosity. Republicanism varied greatly. Liberal republicans respected the will of Ie but feared social disruption. Democrats were sensitive to popular susceptibilities and less afraid of disruption. Republican social reformers, on the other hand, idealized populism. Each faction refused to be dominated by the others. These divisions in turn contributed to the formation of yet more splinters. All the while, counter-revolutionaries, socialists and, later, communists alternatively assumed the protest role. Opposition groups rarely formulated solutions to problems. Typically, they attempted to do just what AD later tried: paralyse public life and discredit the establishment. Political, social and economic problems were supposed to be solved by a central authority[7], as they were to have been under die old monarchy.

The spectacle itself is part of the whole drama of French authority, for the leader’s act is performed in a way that perpetuates nonparticipation - both because of his own way of turning the show into a monologue addressed to the whole people, instead of channeling the structured participation of his supporters cither in totalitarian or in democratic Tace-to-face* organizations, and because his insolent ‘personal power’ confirms his adversaries in their own purely negative association and in their distrust of strong leadership?[4]’

Modernization exerted a profound influence on political behaviour by spawning fundamental social and ideological differences. Throughout the nineteenth century, groups supported regimes on the basis of social changes that they made. Institutions were always fragile because "social consensus was not enough - a political consensus was missing; there was no agreement either on the objectives for which political power is to be used, or on the procedures through which disputes over such objectives can be resolved*.[20] Leadership and national authority fluctuated between periods of "routine’ authority, deadlock and immobility. If inertia developed, it was typically surmounted by a charismatic political hero who articulated a new consensus. Ironically, the mutable political culture was not as fragile as institutions and governments. Attitudes towards politics were unaffected by the many reorganizations of public life. The rationalist activism of political groups and France’s geographic location provided interior and exterior pressures that prevented a complete paralysis of public life. Further complicating the scenario, post-1789 ideologies coexisted with pre-revolutionary Roman legal, Catholic, feudal and absolutist traditions. Monarchists and republicans agreed that an interventionist state should safeguard France’s international stature. Since it established a minimal consensus and divided society less than other regimes, republicanism was slowly consolidated as the dominant public ideology. A republican regime excluded fewer groups and so alleviated the impact of alienated sectors that could seek revenge on incumbents. On the positive side, all of these influences endowed the state with historical flexibility (since alternatives existed) and structured the revolutionary-counterrevolutionarydispute:

all of nineteenth-century French history could be considered as the history of a struggle between the Revolution and the Restoration, through certain episodes that occurred in 1815, 1830, 1848, 1851, 1870, the Commune and 16 May 1877. Only the victory of the republicans over monarchists at the beginning of the Third Republic conclusively signified the victory' of the Revolution throughout the country.[21]

Because they viewed regimes as imperfect preludes to authentic revolution or counter-revolution, many participants were profoundly suspicious of authority and jealous of individual rights. Although society' was highly stable and the state powerfully centralized, popular discontent occasionally culminated in upheaval:

conflicts between individuals in a group or between groups will be much less resolved than stifled, "arbitrated’, perhaps temporarily assuaged, and quite likely perpetuated, by resort to higher authority'.

When protest occurs, it often expresses the same institutional intolerance of conflict in reverse, through demands for radical and definitive settlement or through dreams of frictionless harmony.[22]

These divisions had long-term effects on the political culture in which AD later developed. The left is still divided between libertarian and egalitarian interpretations of socialism. The radical egalitarianism that influenced AD is most directly associated with Auguste Blanqui. The rise of blamjuisme under the Second Empire set a significant precedent:

What was important for Blanqui was to take power and impose revolution on the rest of France through a Parisian dictatorship. To achieve this, he did not count on the working class at all since he did not judge it mature enough, but rather on a team of professional revolutionaries, devoted body and soul to the Cause; the labouring classes would then become the support for this revolutionary dictatorship, which would apply communist principles and spread them abroad.[23]

Repeated alternation between empire, restoration, constitutional monarchy and republic produced many political models. From 1789 to 1880, controversies over institutions and values repeatedly led to violence. Regimes were established in reaction to their predecessor:

During the nineteenth century, each new regime fundamentally repudiated its predecessor, set itself up on its debris and drew its legitimacy from this rejection - even if, by doing so, it referred itself to the regime before the preceding as in a game of leap-frog: the Restoration with the old regime, the Second Republic with the Convention, Napoleon III with the Empire, the Third Republic with the French Revolution/[4]

The 1789 revolution generated ideologies that still resonate in national political life. the most important ideological product of 1789,

was hn effect the party of the French Revolution... A radical was one who professed a loyalty towards the French Revolution that was analogous to that of royalists for their king*.[25] The Jacobins used the nation as a new political symbol. Under their influence, Trance has ideas as a means of expression and sign while under the king it had persons, whether physical or moral, as its means of expression and sign ... The French nation is a missionary nation, bearing a message/^ The nation was a symbol of political unity, rights and equality that replaced the ancient link between the monarch and people. The nation placed the people above monarchical privileges based on region, class, occupation, religion and economics. The Jacobins were egalitarian, individualist and rationalist: ‘the real Jacobin can be recognized since, from time to time, he says to himself: “I am clearly the only pure one”?[27] By using the people and nation, the Jacobins anchored nationalism and republicanism in public life. The nationalist view of language, custom and religion transformed traditional divisions into foci for unity. The revolutionaries used the symbol of the nation to rally the population to defend France against foreign invasion. In doing so, they also broadened their legitimacy: ‘the Revolution started by preaching fraternity among peoples, and a common crusade against wicked governments . . . [but). . . ended, however, by confining true fraternity to Frenchmen and French subjects’?[8] Jacobin universalism soon conflated humanity with the nation, 1789 with republicanism, and tied revolutionary ideals to a historical state. To replace social rank and productive or territorial associations, the Jacobins organized clubs that spread republican and nationalist ideas: ‘learned societies conflicted with natural or interest groups insofar as men met there to discuss, criticize, stir ideas, act through ideas*.[29] They launched a pan-European revolutionary crusade against oppressive aristocracies in the name of equality, liberty and fraternity.

Like Jacobinism, socialism joined the French ideological constellation after 1789. Socialist thought was strongly affected by the idea that the revolution evinced the inevitable rise of the masses. Saint-Just said socialism introduced ‘happiness ... a new idea in Europe’.[30] Jacobinism and socialism combined into an egalitarianism that advocated ‘a minimum of happiness for everyone, the potential for everyone to know those goods proper to human existence’.[31] The clash between this socialist egalitarianism and traditionalism placed religious and metaphysical quarrels at the centre of public life.

The socialist ideal is never exhausted by the realization of a particular end, while radical ideals underwent a crisis that still continues as a result: neither is the Christian ideal exhausted by a particular success, such as the life of a saint . .. While radicalism seeks to more or less peacefully eliminate religion, socialism aspires to replace it.[32]

The disestablishment of Catholicism accompanied the articulation of secular government principles and pushed several groups into a counterrevolutionary stance?[3] The ideological, institutional and educational struggles that ensued from the loss of consensus in 1789 were a pattern that later conditioned AD’s attitude towards political action and the system as a whole?[4]

77?£ classic French regime: 77?e Third and Fourth Republics

The Third Republic expressed the classical post-1789 political balance: institutions were accepted as a workable compromise. However, the regime was nor based on a viable consensus. The threat of revolutionary revision was ‘provisionally’ suspended and the Third Republic became the most long-lived post-revolutionary regime. Deeply rooted in political, social and cultural attitudes, political institutions coalesced the haute bourgeoisie^ lower middle class artisans, shopkeepers and peasantry. All of these groups favoured pre-industrial values and were averse to ‘modernist’ techniques and pragmatism?* However, the coalition was ill-adapted to urban industrialism. It resisted economically based decision-making, viewed work as a social activity, and preserved values such as the family, thrift, historically accumulated prestige and individualism. As a result, new technology was adopted reluctantly, labour-intensive methods were favoured and industry concentrated on the production of luxury goods. The new industrial labour force and bourgeoisie were pushed into opposition to the regime. They aroused the establishment’s fears of losing interests, positions, ‘old freedoms’ and ‘inherent rights’?[7]

To minimize change and avoid potential upheavals, Third Republic political institutions restricted the executive, excluded socio-economic alternatives and precluded dominance by any single parry. Hierarchy and political immobilisme[3]* were masked by equalitarian rhetoric. Plebiscites perpetuated a myth of the people and focused attention on change. The repeated resolution of crises fed a belief that the regime, though imperfect, was better than the available alternatives. At the pinnacle of power, charismatic figures periodically addressed monologues to the nation and perpetuated norms of non-participation:

the leader, an outsider who breaks in when the routine has broken down and the rituals have crumbled, has the double prestige of rebellion and prowess; he is the man who reasserts individual exploits after and against the impersonal, anonymous greyness of routine authority ?[9]

Counter-revolutionaries and the extreme left continually attempted to upset the Third Republic social equilibrium?[0] Intellectuals viewed revolution and the progression of national consciousness as principles that governed development of collective life. Under the influence of socialism and nationalism, political thought became a ‘quest for new general systems ... the recapturing of master}' over history by finding its intellectual key’?' Intellectual protest centred on universal human goals:

The republican tradition, even and especially when it wants to integrate modernity; in fact more or less consciously refuses the break that Anglo-Saxons entirely acknowledge. We fully saw this concerning political forms: the principle of government by the people was always superimposed over simple 'guarantees’ of individual rights/[2]

Opposition attitudes also reflected immobilhme. Direct parliamentary conflict was rare since the concerned parties were either physically absent or entrenched in maximal positions. Long negotiations that entailed questioning positions and compromise were associated with 'selling out’. Deadlocks were not resolved by recourse to principles but by appeals to charismatic authoritarians (such as Boulanger, MacMahon, Clemenceau and Petain):

conflicts are referred to a higher central authority . . . power is delegated to it so that the drama of face-to-face personal relations can be avoided bin only in order that, and as long as, the exercise of power from above remains impersonal and curtailed both in scope (subject-matter) and intensity (means of action) by general rules, precedents, and inhibitions.[43]

In many respects, the regime was profoundly anti-democratic and authoritarian. The episodic character of routine and influence of charisma hampered the development of political movements based on mass mobilization. Many social groups remained on the political fringe until the early 1930s. At the same time, the differentiation of behaviour into degrees of compromise or opposition to the regime gave resilience to the Third Republic political culture. To this day, the French distrust definitive solutions and 'managerial’ government.

Crisis, as a privileged means of bringing about change, may indeed be considered as the basic cultural trait conditioning the Frenchman’s favourite style of collective action. In the strategy[7] of human relations to which the French are accustomed, this style is characterized by a deep and constant opposition between the individual and the group: the group is perceived and experienced as an organ for defence and protection whose activities can only be negative, while it is for the individual himself to find new means of self-assertion/

Only on foreign policy issues did the Third Republic successfully establish a consensus that synthesized national history'. This was possible because all groups had 'the same identifying belief - that France was a pace-setter for the rest of the world’/[5] Foreign policy was based on a Roman ideal that also affected the old regime: belief that military' power and extent of national territory reflected influence and greatness* Military defeat and annexation of Alsace-Lorraine in 1871 provoked deep uneasiness, fear of Germany and led to alliances as a way to ensure territorial integrity and prestige. After the First World War, the French even supported appeasement, a British Ton[1] policy that contradicted national interests, due to fatigue and reluctance to prepare for another war. The ensuing disaster ended the Third Republic and threw France’s international credibility into serious doubt.

In setting up the post-war Fourth Republic, the French were obsessed by restoring their credibility and independence of action. The principles that underlay the new republic thus reacted both to Vichy and the Third Republic. The constitution attempted to block the charismatic embodiment of power by a new Petain by making the Assemblee Nationale the centre of government and by instituting universal suffrage (absent in the Third Republic)*[46] Nationalism was discredited as a political symbol and replaced by democracy. The right was tainted by collaboration even though the wartime resistance movement acknowledged that the Nazis exploited a mostly passive nation and that 1944 was a human, not French, victory. The once marginal PCF embodied resistance and liberation. Unity was provided by de Gaulle. Even though he left direct political activity in 1946, condemned party machinations and claimed he was external to political games, de Gaulle founded a powerful right-wing movement. The SFIO (Section franpiise de I'biternatimiale ouvriere- French section of the Workers’ International), MRP repiMaiinpopulaire-Popular Republican

Movement, a small progressive Catholic party) and PCF governed in coalition from 1944 to 1946. This tripartisme*' declined as the national emergency faded and political in-fighting and US anti-communist pressure grew. Under the leadership of Guy Mollet, the SFIO opposed PCF Stalinism and allied with the non-Gaullist right. The centre-Ieft MRP wanted socio-economic change but was constrained by its anti-Marxist progressive Catholic electorate/

The French state meanwhile urgently needed new institutions, public support, systematic reconstruction policies and a consistent foreign policy. Socio-political tension rose over inadequate housing, transport, poor access to higher education, weak unions, uneven modernization/'[1] and a political system that disenfranchised a large minority. It grew throughout the 1950s. The absence of foreign policy consensus made France dependent on US military and financial patronage. Many transformations were started in this period: (1) decolonization; (2) new military—civilian relations; (3) renewed nationalism; and (4) development of consensually based institutions* New policies focused on economic reform, the EEC. force de frappe/" industrial and urban modernization, and international economic competition. Renault was nationalized. The PCF and CGT {Confederation Generate du Travail - General Workers’ Confederation) participated in planning. The CNPF (Conceit National du Patronat Francis - National Council of French Employers), a pre-war centre of anti-unionism and anti-modernization sentiment, was discredited by collaboration. However, conservative and liberal Third Republic politicians rapidly upstaged the ‘modernizers’ and immobilisme returned in the 1950s. Traditional business thus benefited from Marshall Plan investment while state sectors failed to lead development. These factors confirmed extreme-left views that nothing had fundamentally changed and representative government simply masked capitalist domination.

After 1924, Third Republic politicians had routinely ruled by decree to circumvent conservative Senate majorities. The practice was effective but discredited democratic institutions. Fourth Republic institutions were designed to overcome this problem by ending factionalism and reinvigorating part}’ competition. Unfortunately, aside from Pierre Mendes-France’s government (June 1954-Fcbruary 1955), inertia persisted and right-left competition did not lead to consensus. A ‘regime of parties’ favoured parliamentary intrigue over national interests. It generated a diffuse and inconsistent authority that depended on alliances: 25 governments rose and fell between 1946 and 1958?[1] Cabinets were unable to concur over problems and solutions.[52] High-priority policies were shelved to presen e coalitions. The Fourth Republic became vulnerable to discontent, especially after the extreme-right re-emerged in the 1950s.[5]' By selectively supporting or resisting re forms, a number of social sectors effectively sabotaged institutions, Army leaders, for example, were generally republican, but believed decolonization threatened national prestige. The prospect of withdrawal from Algeria mortally wounded the Fourth Republic. Army traditionalists believed that they had to protect civilians from terrorism in Algeria and provide balance for domestic instability, incoherence and crisis. Contradictory government policy, lack of alternatives and cabinet and parliamentary fiascos hardened their resolve. Politicians followed two contradictory paths:

One is the war matched with repression: abroad, it leads to Suez while domestically it brings them to tolerate torture. The other response is the search for a diplomatic solution that does not call itself one and that, from the corridors of the UN to the ‘good offices’ of the US, passing by Rabat and Tunis, seems bereft of a clearly defined objective?[4]

The public feared a neo-Francoist coup and petainisme^ but also ‘drastic changes in France’s economic and international positions’[56] to accommodate a diminished international stature, colonial crisis and US indifference.

The Fifth Republic

Initially fashioned on the basis of de Gaulle’s criticism of the previous two republican regimes, the Fifth Republic was consciously designed to resolve the contradictory tendencies in post-1789 French political history. This effort explains why Fifth Republic institutions aroused the long-term hostility[7] of both extreme-left and extreme-right groups. In particular, it mixed elements that both groups opposed - an ‘authoritarian’ presidency and parliarnentarianism. The regime also explicitly attempted to polarize political stances and forces, a factor that explains the vehemence of protest movements such as^cAfwk'and the FN. Aside from propelling de Gaulle into power, ‘the two fundamental purposes that underlay the establishment of the Fifth Republic were most certainly to resolve the Algerian problem and to remake the state’/[7] The new institutions were initially identified with de Gaulle and the Gaullist movement, and were openly used to weaken the left:

the Gaullists were above all concerned with establishing institutions and procedures which could be both efficient and autonomous. Their critique of parliamentarianism was essentially that the Third and Fourth Republics had been too divided and weak to control the production, consumption and international functions which the state needed to assume out of necessity in an advanced capitalist society' operation within a complex w[r]orld economy.[515]

Only after the Algerian war ended in 1962 did direct presidential elections incorporate mass participation into political institutions. Legitimacy was then enhanced by separation of powers, clarification of presidential authority and establishment of a Cwtseil cousfiuui&tif/e/F Before this, it was unclear whether the Fifth Republic was a personal vehicle or hybrid: Tor years this constitution was the object of gloss “exegeses” that reduced it neither to a parliamentary nor to a presidential regime’.*[0] The regime was unusual in French political history since it sought ‘to transform neither human nature nor society'. The consensus included the main leftand right-wing political groups, excluding only extremes’/[1] In one sense, the new republic was orlearuste (a French version of the nineteenth-century British political system) because it blended institutional primacy: ‘an intermediary between a limited monarchy and the classic parliamentary regime, of which the 1830 Charter and Louis-Philippe d’Orleans are a very good example’.[62] Most significantly, the new constitution drew political conflict off the street. After two centuries of struggle, the regime institutionalized right-left coexistence by making

theoretical ‘cohabitation’ possible. De Gaulle, in 1964, rejected a pure presidential system because (a) in France, it was likely to lead to a paralysis of power, to an insoluble deadlock between President and Parliament, and (b) it would in fact result in a weak President, capable of governing only by yielding to the ‘will of the parties[1]/[5]

The left was pushed out of power for 20 years due to de Gaulle’s charisma and its association with the Fourth Republic* The PCF weathered the shock relatively well[64] but the SFIO, Radicals and MRP fell apart/’[5] The PSU (Parti socialist? unifie - Unified Socialist Party) claimed the left-wing contes tataire™ heritage, intellectually challenging the regime and mediating between the mainstream and extra-parliamentary left/[7] All the while, the ncw[f] institutions decreased revolutionary rhetoric, parfiamentarianism, policy paralysis and suspicion.

De Gaulle and his supporters have attempted to control and channel these processes of political change in two ways* The first of these has been to continue to attack the foundations of the traditional system; the second has been to construct partial alternatives especially geared to take advantage of the changing circumstances/*

All political parties changed after the Asscmblee Nationale was weakened by new legislative procedures, votes of confidence and the end of parliamentary supremacy. The left’s revolutionary orientations diminished after it made a strong 1965 presidential challenge and gains in the 1967 legislative elections* However, left-wing reformism helped spark gauchisme, an extreme-left movement that rejected compromise with Gaullism/[9] introduced new issues (feminism, environmental

ism, regionalism and gay rights) and was embraced by Maoist, Trotskyist and anarchist organizations: 'multiple, protean, ready to confront each other, each incarnating the true revolution in relation to which the others are traitors’.[76] However, the Fifth Republic proved able to integrate discontent: contraception, abortion, urban reform, open government, decentralization, regionalization and telecommunication reforms soon became mainstream policies.[71]