Paul and Percival Goodman

Communitas

Means of Livelihood and Ways of Life

Contemporary Criticism of Our American Way of Life

Inherent Difficulties of Planning

Technology of Choice and Economy of Abundance

The Importance of Planning in Modern Thinking

Part I: A Manual of Modern Plans

The Evolution of Streets from Village to City

Disurbanists and Functionalists

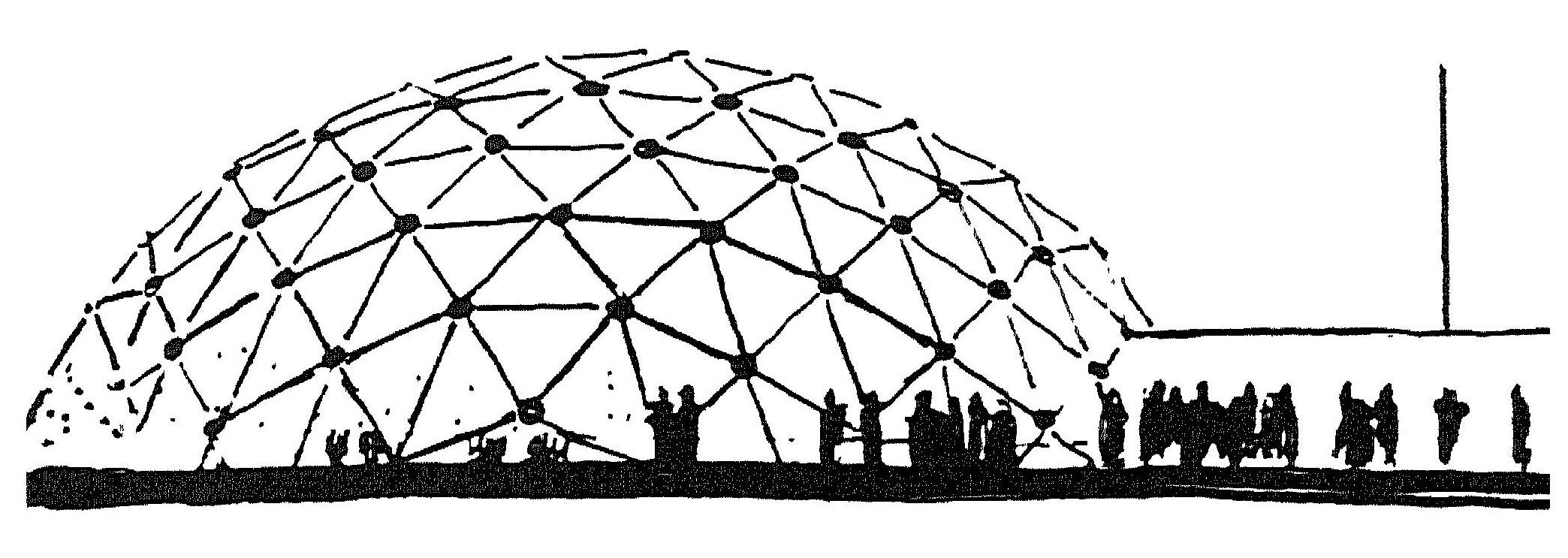

Dymaxions and Geodesics, 1929–1959

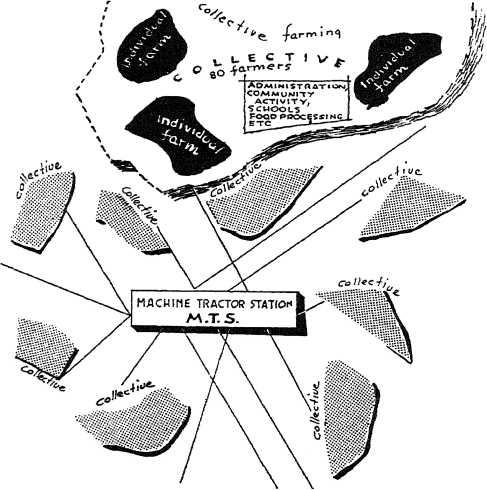

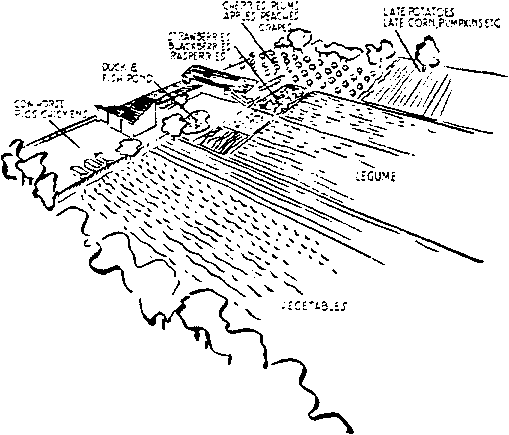

The Industrialization of Agriculture

Part II: Three Community Paradigms

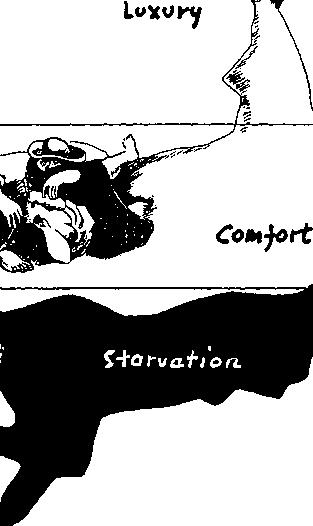

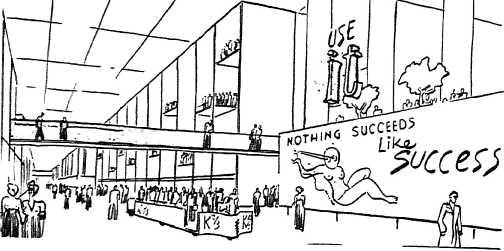

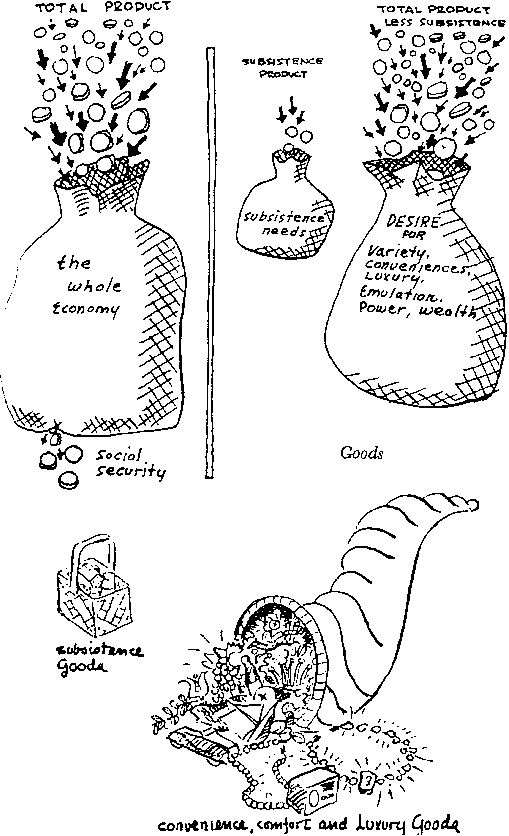

The Need for Planned Luxury Consumption

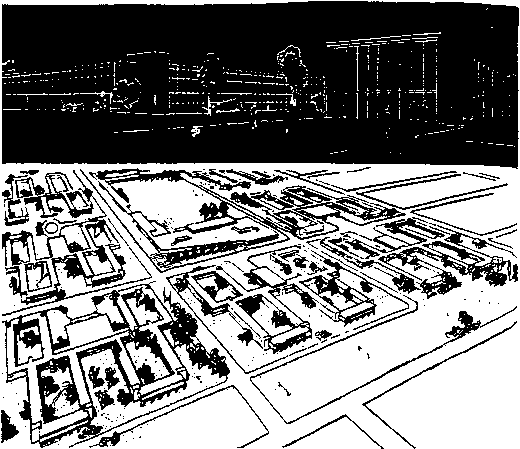

Chapter 5: A City of Efficient Consumption

The Metropolis as a Department Store

On the Relation of Production and Consumption

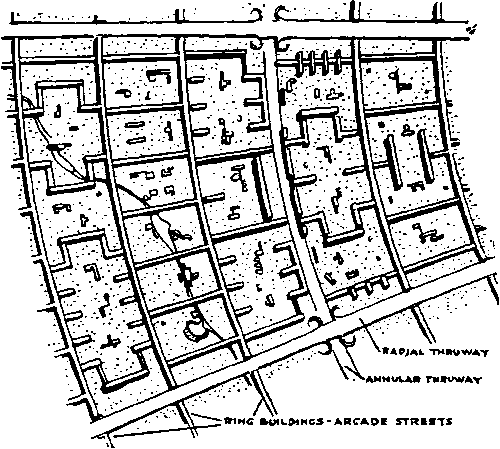

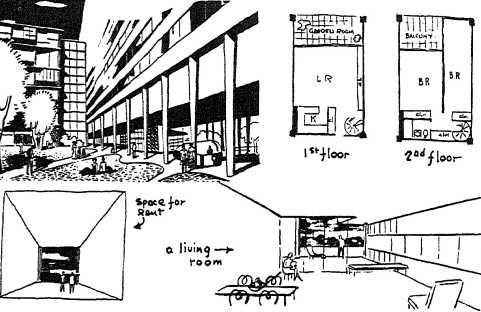

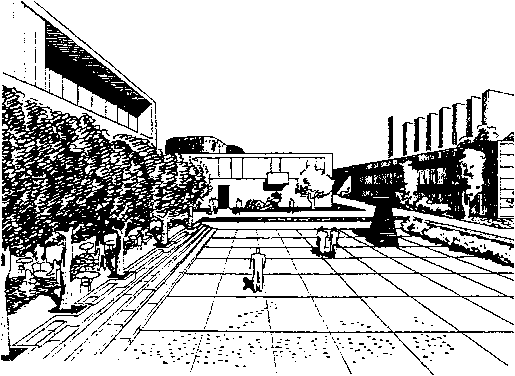

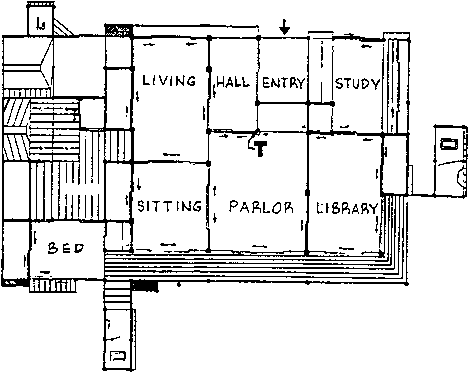

The Center: Theory of Metropolitan Streets and Houses

Chapter 6: A New Community: The Elimination of the Difference between Production and Consumption

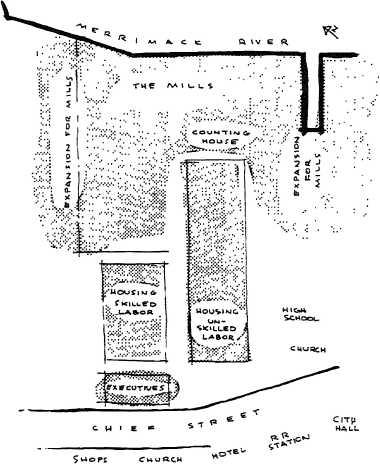

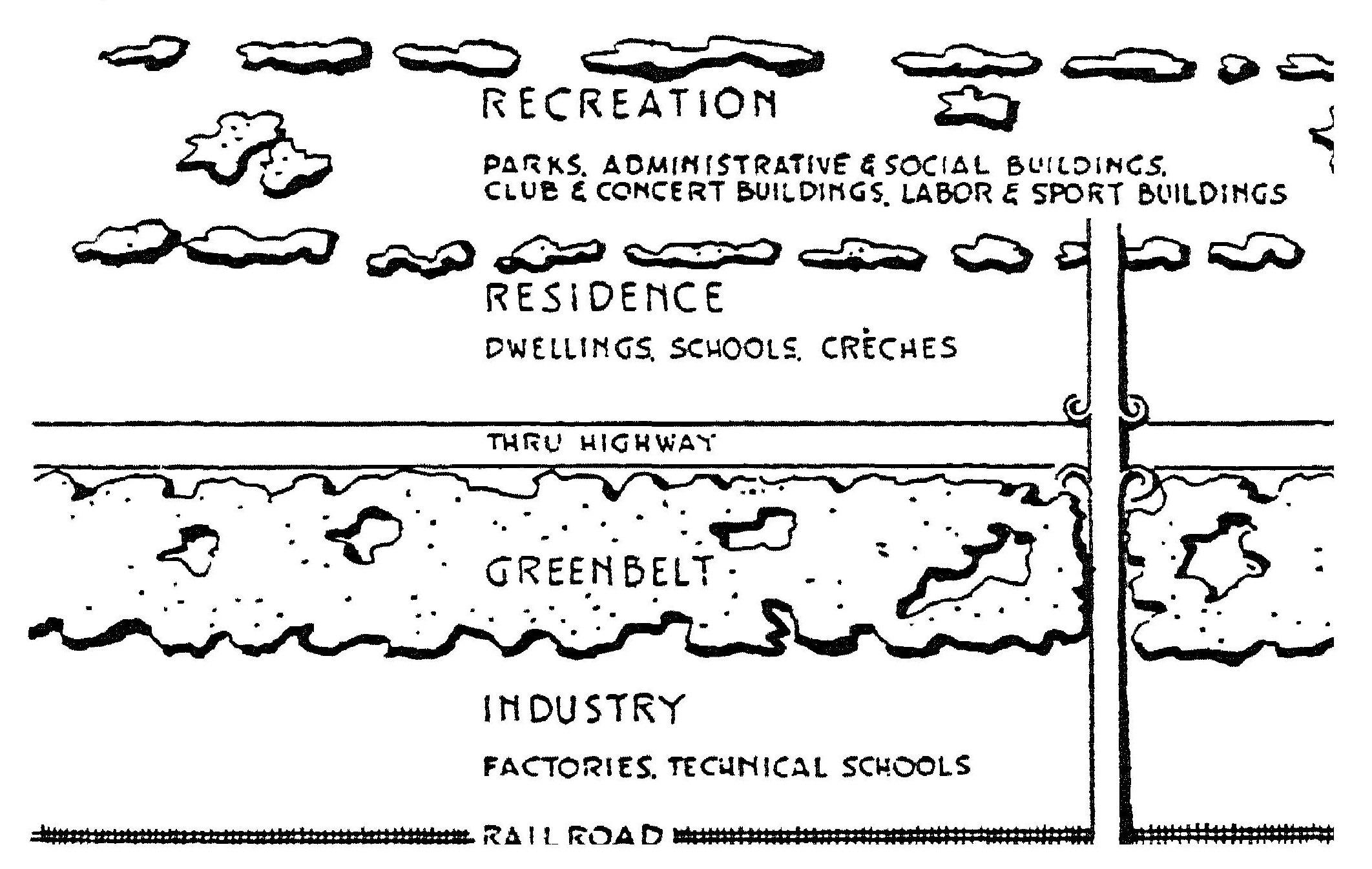

Quarantining the Work, Quarantining the Homes

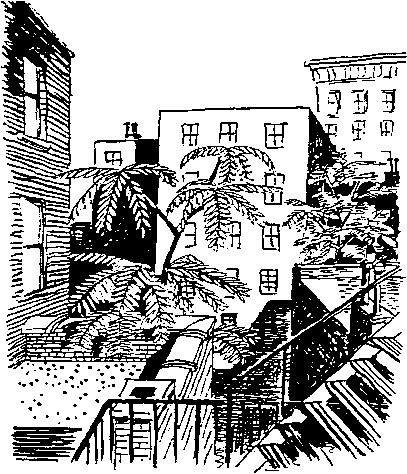

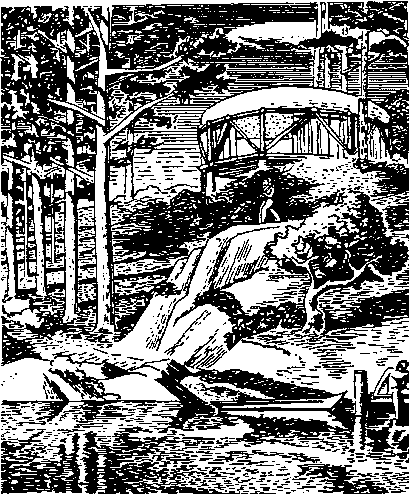

Notes on Neo-Functionalism: The Ailanthus and the Morning-Glory

The Theory of Home Furnishings

Public Faces in Private Places

Chapter 7: Planned Security With Minimum Regulation

The Sense in Which Our Economy Is Out of Human Scale

Social Insurance vs. the Direct Method

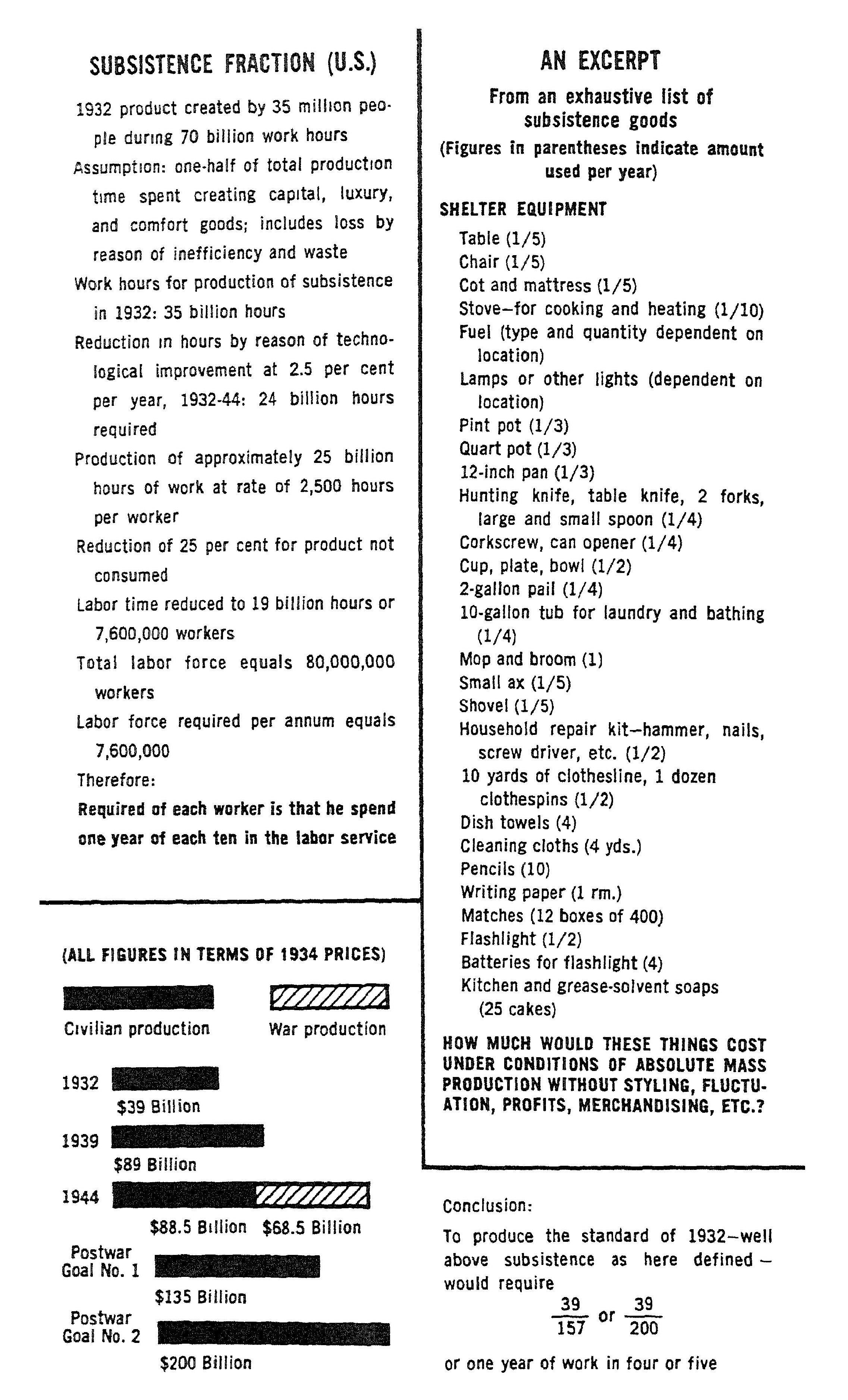

The Standard of Minimum Subsistence

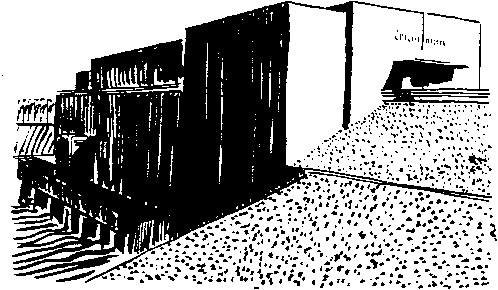

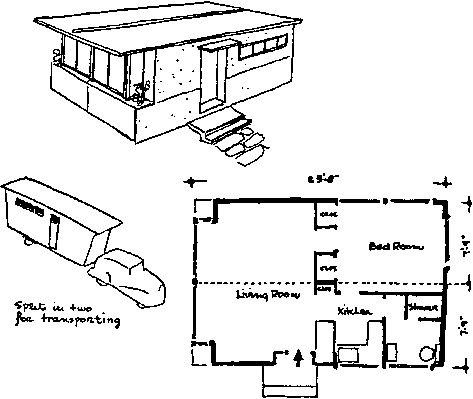

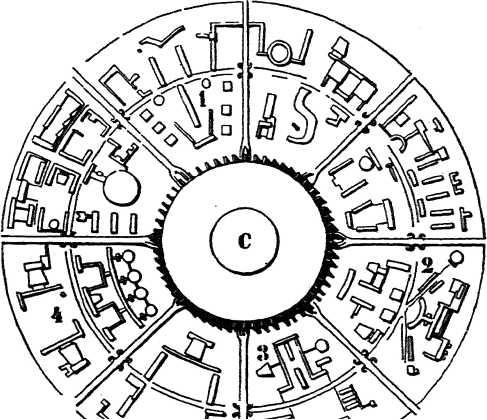

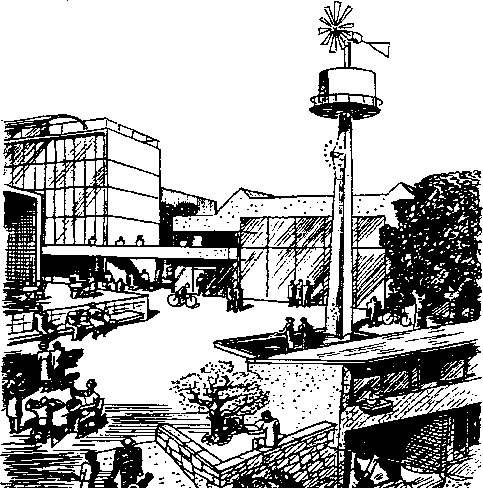

Architecture of the Production Centers

Teacher! Today Again Do We Have to Do What We Want to Do?

Jobs, Avocations, and Vocations

Vocation and “Vocational Guidance”

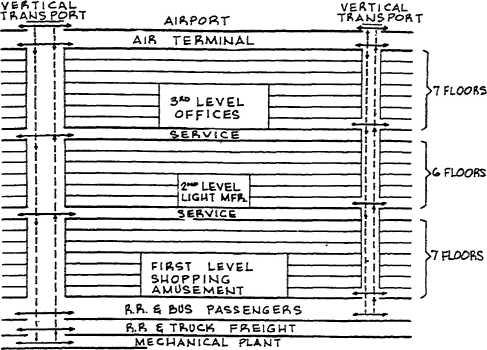

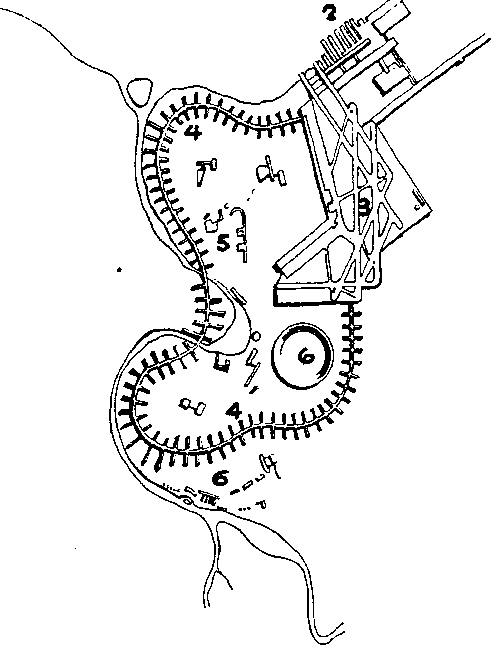

Scheme IV: A Substitute for Everything

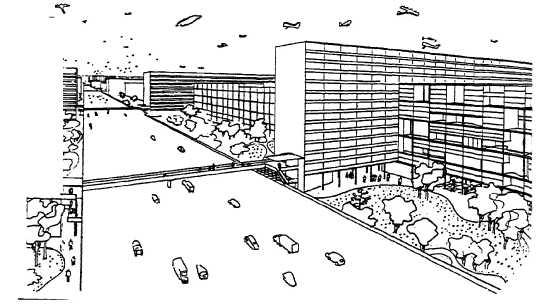

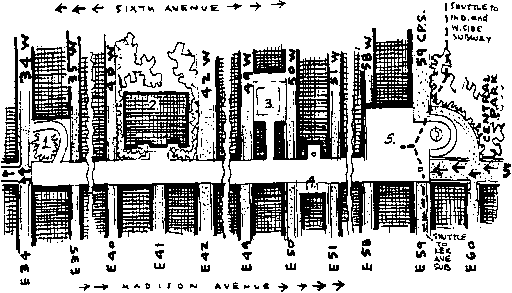

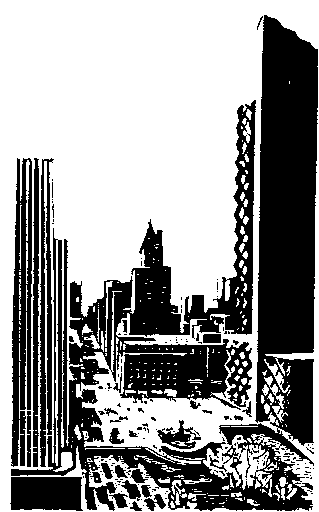

Appendix A: A Master Plan for New York

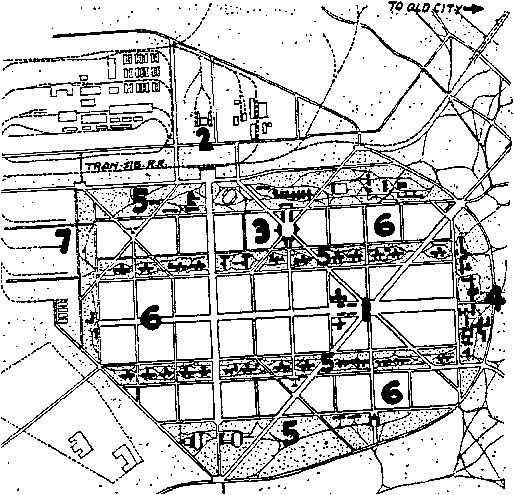

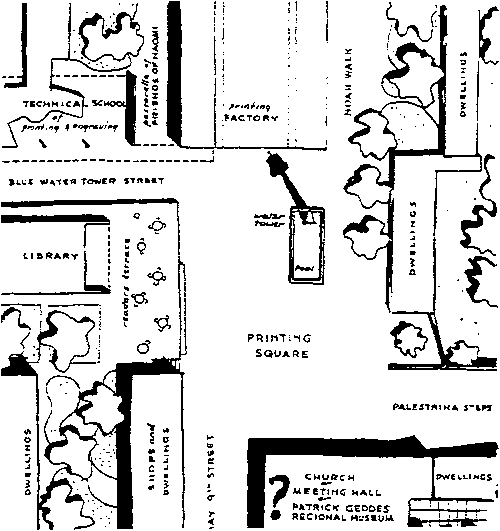

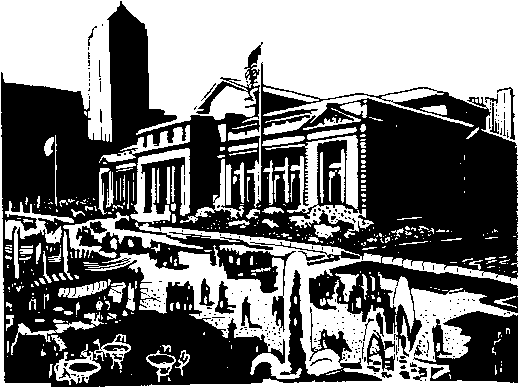

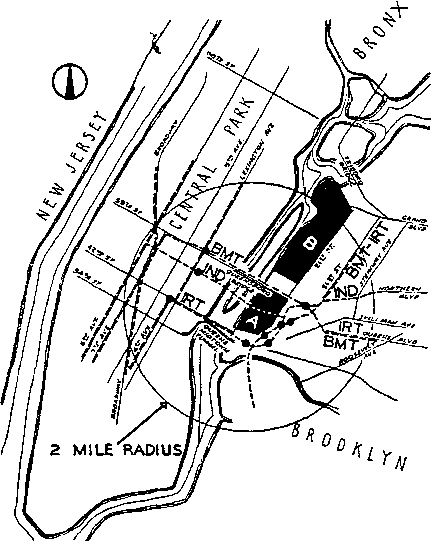

The Parts of the Physical Plan

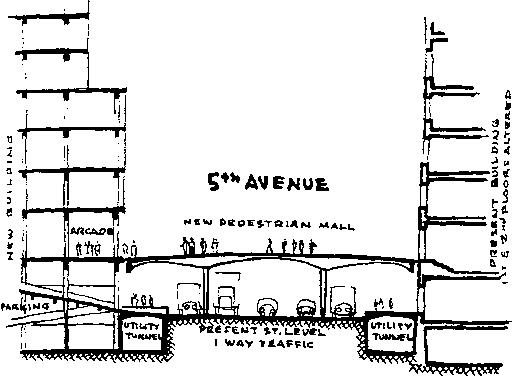

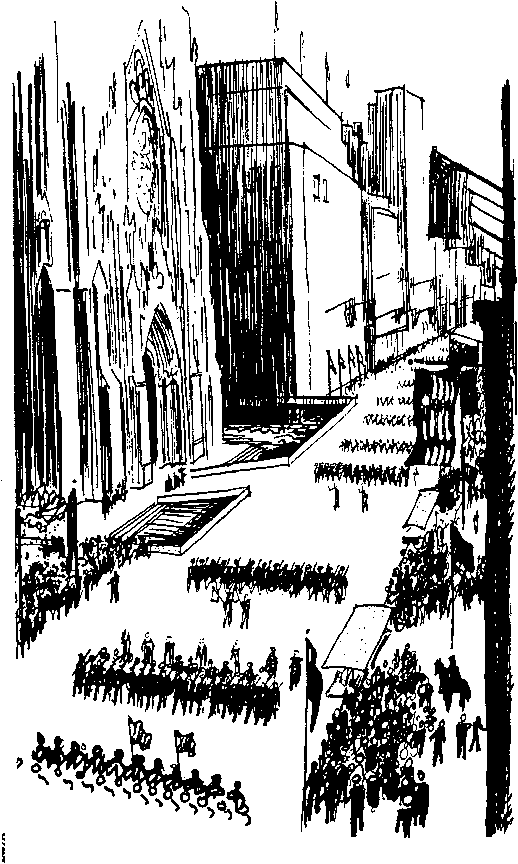

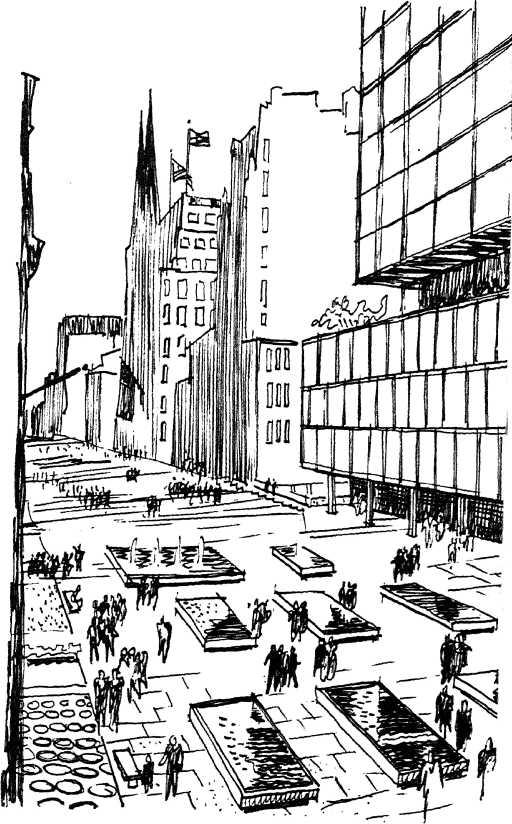

Appendix B: Improvement o£ Fifth Avenue

Appendix C: Housing in New York City

Appendix D: A Plan for the Rejuvenation of a Blighted Industrial Area in New York City (1944–45)

COMMUNITAS

Means of Livelihood

and Ways of Life

Percival and Paul

Goodman

VINTAGE BOOKS

A DIVISION OF RANDOM HOUSE

New York

© Copyright, 1947,1960, by Percival and Paul Goodman

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in New York by Random House, Inc., and in Toronto, Canada, by Random House of Canada, Limited.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 60–6381

VINTAGE BOOKS

are published by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

and RANDOM HOUSE, INC.

Manufactured in the United States of America

COMMUNITAS

Means of Livelihood and Ways of Life

Chapter 1: Introduction

Background and Foreground

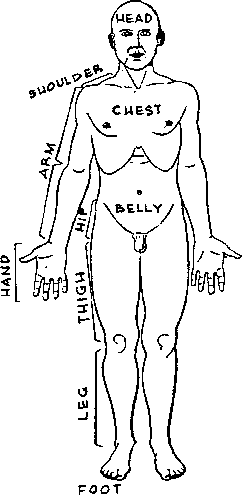

Of the man-made things, the works of engineering and architecture and town plan are the heaviest and biggest part of what we experience. They lie underneath, they loom around, as the prepared place of our activity. Economically, they have the greatest amount of past human labor frozen into them, as streets and highways, houses and bridges, and physical plant. Against this background we do our work and strive toward our ideals, or just live out our habits; yet because it is background, it tends to become taken for granted and to be unnoticed. A child accepts the man-made background itself as the inevitable nature of things; he does not realize that somebody once drew some lines on a piece of paper who might have drawn otherwise. But now, as engineer and architect once drew, people have to walk and live.

The background of the physical plant and the foreground of human activity are profoundly and intimately dependent on one another. Laymen do not realize how deep and subtle this connection is. Let us immediately give a strong architectural example to illustrate it. In Christian history, there is a relation between the theology and the architecture of churches. The dimly-lit vast auditorium of a Gothic Catholic cathedral, bathed in colors and symbols, faces a bright candle-lit stage and its richly costumed celebrant: this is the necessary background for the mysterious sacrament of the mass for the newly growing Medieval town and its representative actor. But the daylit, small, and unadorned meeting hall of the Congregationalist, facing its central pulpit, fits the belief that the chief mystery is preaching the Word to a group that religiously governs itself. And the little square seating arrangement of the Quakers confronting one another is an environment where it is hoped that, when people are gathered in meditation, the Spirit itself will descend anew. In this sequence of three plans, there is a whole history of dogma and society. Men have fought wars and shed their blood for these details of plan and decoration.

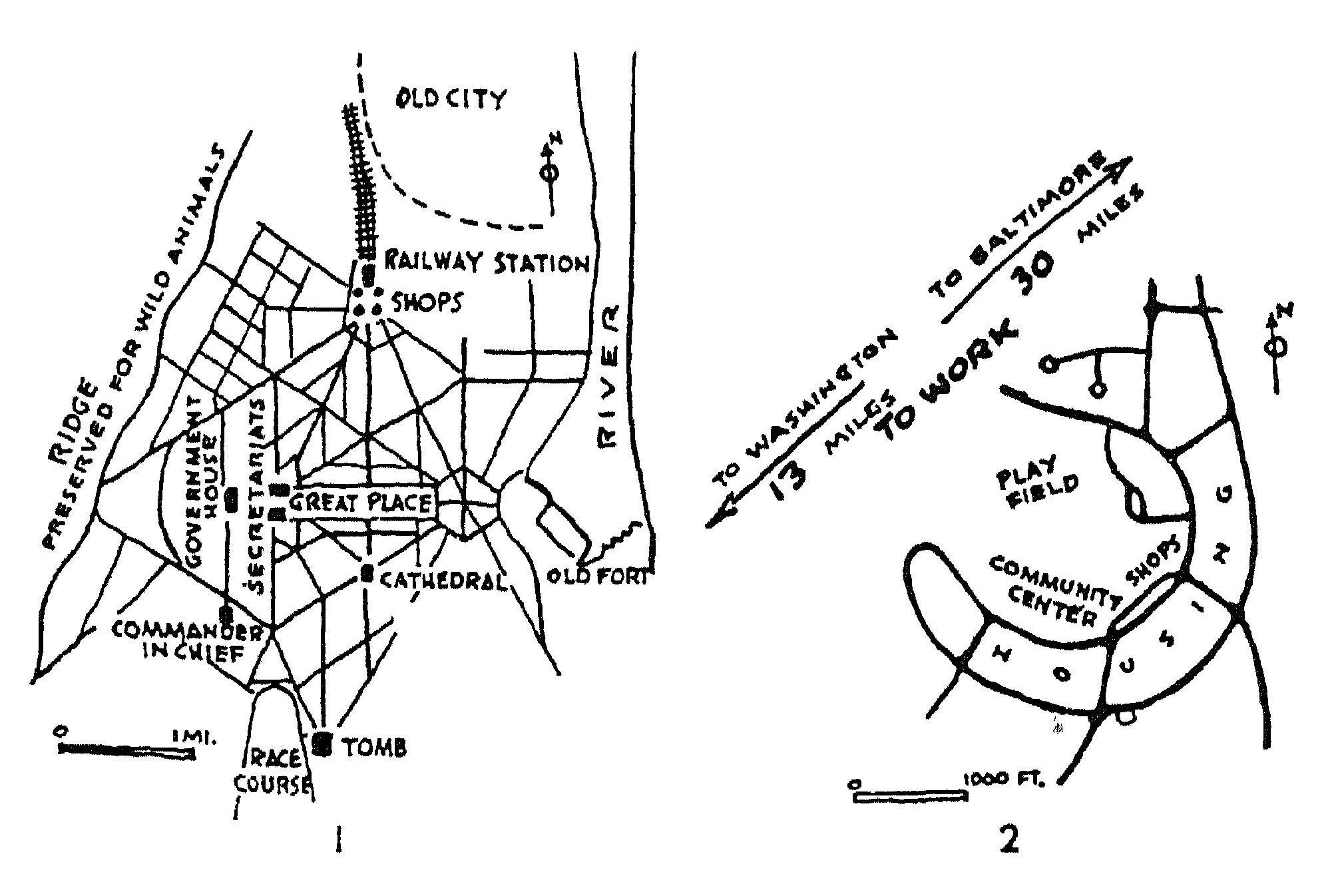

Just so, if we look at the town plan of New Delhi we can immediately read off much of the history and social values of a late, date of British imperialism. And if we look at the Garden City plan of Greenbelt, Md., we can understand something very important about our present American era of the “organization man.”

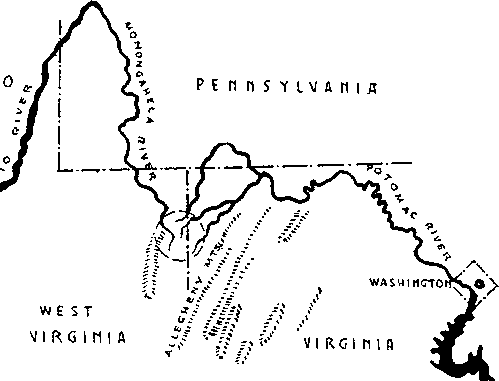

We can read immediately from the industrial map of the United States in 1850 that there were sectional political interests. Given a certain kind of agricultural or mining plan, we know that, whatever the formal schooling of the society may be, a large part of the environmental education of the children will be technological; whereas a child brought up in a modern suburb or city may not even know what work it is that papa does “at the office.”

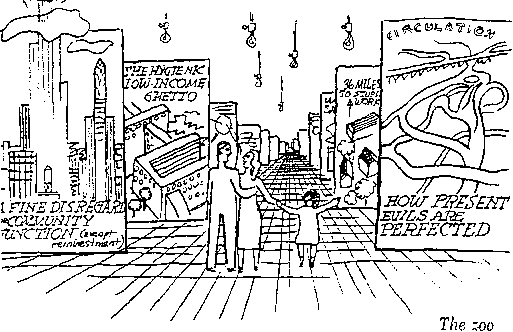

Contemporary Criticism of Our American Way of Life

For thirty years now, our American way of life as a whole has been subjected to sweeping condemnation by thoughtful social and cultural critics. From the great Depression to World War II, this criticism was aimed mostly at our economic and political institutions; since the war, it has been aimed, less trenchantly but more broadly, at the Standard of Living, the popular culture, the ways of work and leisure. The critics have shown with pretty plain evidence that we spend our money for follies, that our leisure does not revive us, that our conditions of work are unmanly and our beautiful American classlessness is degenerating into a static bureaucracy; our mass arts are beneath contempt; our prosperity breeds insecurity; our system of distribution has become huckstering and our system of production discourages enterprise and sabotages invention.

In this book we must add, alas, to the subjects of this cultural criticism the physical plant and the town and regional plans in which we have been living so unsatisfactorily. We will criticize not merely the foolish shape and power of the cars but the cars themselves, and not merely the cars but the factories where they are made, the highways on which they run, and the plan of livelihood that makes those highways necessary. In appraising these things, we employ both the economic analysis that marked the books of the 30’s and the socio-psychological approach prevalent since the war. This is indicated by our sub-title: “The Means of Livelihood and the Ways of Life.” (In social theory, this kind of analysis provides one necessary middle term in the recent literature of criticism, between the economic and the cultural analyses, which have usually run strangely parallel to one another without touching.)

Nevertheless, except for this introductory chapter, this present book is not an indictment of the American way of life, but rather an attempt to clarify it and find what its possibilities are. For it is confused, it is a mixture of conflicting motives not ungenerous in themselves. Confronted with the spectacular folly of our people, one is struck not by their incurable stupidity but by their bafflement about what to do with themselves and their productivity. They seem to be trapped in their present pattern, with no recourse but to complicate present evils by more of the same. Especially in the field of big physical planning, there has been almost a total drying-up of invention, of new solutions. Most of the ideas discussed in this book come from the 20’s or before, a few from the early 30’s. Since World War II, with all the need for housing, with all the productive plant to be put to new work and capital to invest, the major innovation in community planning in the United States has been the out-oftown so-called “community center” whose chief structure is a supermarket where Sunday shoppers can avoid blue laws.

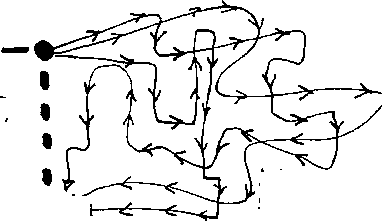

Typical American behavior is to solve a problem of transit congestion by creating a parallel system that builds up new neighborhoods and redoubles the transit congestion; but no effort is made to analyze the kinds and conditions of work so that people commute less. With generous intent, Americans clear a slum area and rebuild with large projects that re-create the slum more densely and, on the whole, sociologically worse, for now class stratification is built organically into the plan; but rarely is an effort made to get people to improve what they have, or to find out where they ought to move. (The exceptions—of the Hudson Guild in New York teaching six Puerto Rican families to make furniture and paint the premises, or of a block getting together to plant nine trees—are so exceptional that they warrant medals from the American Institute of Architects.) A classical example of our present genius in planning is solving the traffic jam on the streets of a great city in the West by making a system of freeways so fast and efficient with its cloverleaves as to occupy 40% of the real estate, whose previous occupants then move to distant places and drive back bumper-to-bumper on the freeways.

If, however, someone plans in a physicianly way to remedy the causes of an ill rather than concentrate on the symptoms, if he proposes a Master Plan to provide for orderly future development, if he suggests an inventive new solution altogether, then he is sure to be called impractical, irresponsible, and perhaps a subversive alien. Indeed, in the elegant phrase of the famous Park Commissioner of an Eastern metropolis, a guardian of the public welfare and morals in the field, such people are Bei-unskis, that is, Russian or German refugees who say, “Bei uns we did it this way.”

Inherent Difficulties of Planning

Yet even apart from public foolishness and public officials, big physical planning is confusing and difficult. Every community plan is based on some:

-

Technology

-

Standard of Living

-

Political and Economic Decision

-

Geography and History of a Place.

Every part of this is thorny and the interrelation is thorny.

There may be historical miscalculation—wrong predictions in the most expensive matters. Consider, for instance, a most celebrated example of American planning, the laying-out of the District of Columbia and the city of Washington. When the site on the Potomac was chosen, as central in an era of slow transportation, the plan was at the same time to connect the Potomac waterway with the Ohio, and the new city was then to become the emporium of the West. But the system of canals which would have realized this ambitious scheme did not materialize, and therefore, a hundred years later, Washington was still a small political center, pompously overplanned, without economic significance, while the commerce of the West flowed through the Erie Canal to New York. Yet now, ironically enough, the political change to a highly centralized bureaucracy has made Washington a great city far beyond its once exaggerated size.

Planners tend to put a misplaced faith in some one important factor in isolation, usually a technological innovation. In 1915, Patrick Geddes argued that, with the change from coal to electricity, the new engineering would, or could, bring into being Garden Cities everywhere to replace the slums; for the new power could be decentralized and was not in itself offensive. Yet the old slum towns have largely passed away to be replaced by endless conurbations of suburbs smothered in new feats of the new engineering— and the automobile exhaust is more of a menace than the coal smoke. Our guess is that these days nucleonics as such will not accomplish miracles for us, nor even automation.

The Garden City idea itself, as we shall see in the next chapter, has had a pathetic history. When Ebenezer Howard thought it up to remedy the coal slums, he did not contemplate Garden Cities without industry; he wanted to make it possible for people to live decently with the industry. Yet, just when the conditions of manufacture have become less noisome, it has worked out that the Green Belt and Garden Cities have become mere dormitories for commuters, who are also generally not the factory workers whom Howard had in mind.

Political Difficulties

The big, heavy, and expensive physical environment has always been the chief locus of vested rights stubbornly opposing planning innovations that are merely for the general welfare and do not yield quick profits. A small zoning ordinance is difficult to enact, not to speak of a master plan for progressive realization over twenty or thirty years, for zoning nullifies speculation in real estate. Every advertiser in American City and Architectural Forum has costly wares to peddle, and it is hard to see through their smokescreen what services and gadgets are really useful, and whether or not some simpler, more inexpensive arrangement is feasible. Since streets and subways are too bulky for the profits of capricious fads, the tendency of business in these lines is to repeat the tried and true, in a bigger way. And it happens to be just the real estate interests and great financiers like insurance companies who have influence on city councils and park commissioners.

But also, apart from business interests and vested rights, common people are rightly very conservative about changes in the land, for they are very powerfully affected by such changes in very many habits and sentiments. Any community plan involves a formidable choice and fixing of living standards and attitudes, of schedule, of personal and cultural tone. Generally people move in the existing plan unconsciously, as if it were nature (and they will continue to do so, until suddenly the automobiles don’t move at all). But let a new proposal be made and it is astonishing how people rally to the old arrangement. Even a powerful park commissioner found the housewives and their perambulators blocking his way when he tried to rent out a bit of the green as a parking lot for a private restaurant he favored; and wild painters and cat-keeping spinsters united to keep him from forcing a driveway through lovely Washington Square. These many years now since 1945, the citizens of New York City have refused to say “Avenue of the Americas” when they plainly mean Sixth Avenue.

The trouble with this good instinct—not to be regimented in one’s intimate affairs by architects, engineers, and international public-relations experts—is that “no plan” always means in fact some inherited and frequently bad plan. For our cities are far from nature, that has a most excellent plan, and the “unplanned” tends to mean a gridiron laid out for speculation a century ago, or a dilapidated downtown when the actual downtown has moved uptown. People are right to be conservative, but what is conservative? In planning, as elsewhere in our society, we can observe the paradox that the wildest anarchists are generally affirming the most ancient values, of space, sun, and trees, and beauty, human dignity, and forthright means, as if they lived in neolithic times or the Middle Ages, whereas the so-called conservatives are generally arguing for policies and prejudices that date back only four administrations.

The best defense against planning—and people do need a defense against planners—is to become informed about the plan that is indeed existent and operating in our lives; and to learn to take the initiative in proposing or supporting reasoned changes. Such action is not only a defense but good in itself, for to make positive decisions for one’s community, rather than being regimented by others’ decisions, is one of the noble acts of man.

Technology of Choice and Economy of Abundance

The most curious anomaly, however, is that modern technology baffles people and makes them timid of innovations in community planning. It is an anomaly because for the first time in history we have, spectacularly in the United States, a surplus technology, a technology of free choice, that allows for the most widely various community-arrangements and ways of life. Later in this book we will suggest some of the extreme varieties that are technically feasible. And with this technology of choice, we have an economy of abundance, a standard of living that is in many ways too highgoods and money that are literally thrown away or given away—that could underwrite sweeping reforms and pilot experiments. Yet our cultural climate and the state of ideas are such that our surplus, of means and wealth, leads only to extravagant repetitions of the “air-conditioned nightmare,” as Henry Miller called it, a pattern of life that used to be unsatisfactory and now, by the extravagance, becomes absurd.

Think about a scarcity economy and a technology of necessity. A cursory glance at the big map will show what we have inherited from history. Of the seven urban areas of the United Kingdom, six coincide with the coal beds; the seventh, London, was the port open to the Lowlands and Europe. When as children we used to learn the capitals and chief cities of the United States, we learned the rivers and lakes that they were located on, and then, if we knew which rivers were navigable and which furnished waterpower, we had in a nutshell the history of American economy. Not long ago in this country many manufacturers moved south to get cheaper labor, until the labor unions followed them. In general, if we look at the big historical map, we see that the location of towns has depended on bringing together the raw material and the power, on minimizing transportation, on having a reserve of part-time and seasonal labor and a concentration of skills, and sometimes (depending on the bulk or perishability of the finished product) on the location of the market. These are the kinds of technical and economic factors that have historically determined, with an iron necessity, the big physical plan of industrial nations and continents.

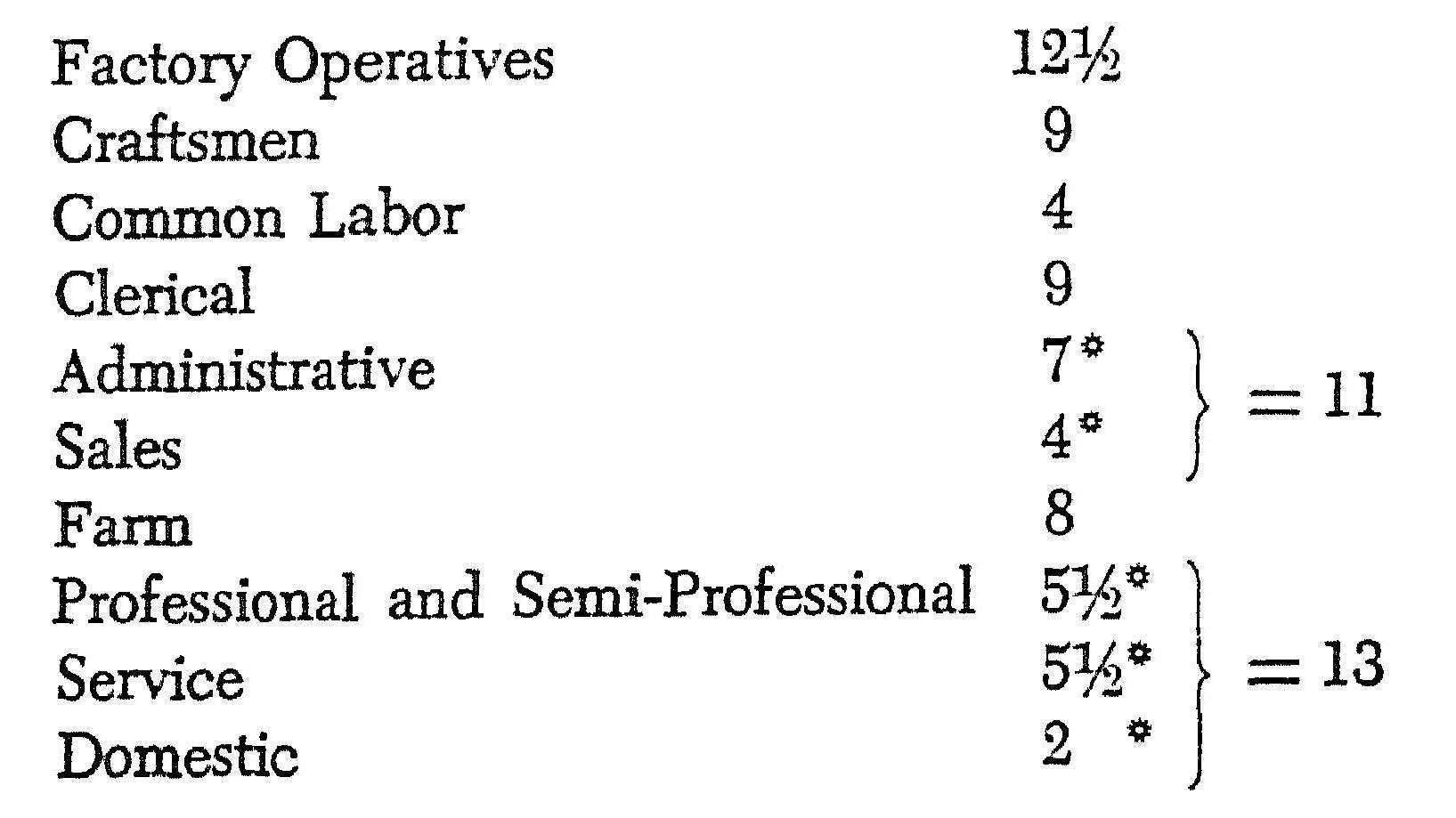

They will continue to determine them, but the iron necessity is relaxed. For almost every item that men have invented or nature has bestowed, there are alternative choices. What used to be made of steel (iron ore and coal) may now often be made of aluminum (bauxite and waterpower) or even of plastic (soybeans and sunlight). Raw materials have proliferated, sources of power have become more ubiquitous, and there are more means of transportation and lighter loads to carry. With the machine-analysis of manufacture, the tasks of labor become simpler, and as the machines have become automatic our problem has become, astoundingly, not where to get labor but how to use leisure. Skill is no longer the arduously learned craftsmanship of hundreds of trades and crafts—for its chief habits (styling, accuracy, speed) are built into the machine; skill has come to mean skill in a few operations, like turning, grinding, stamping, welding, spraying and half a dozen others, that intelligent people can leam in a short time. Even inspection is progressively mechanized. The old craft-operations of building could be revolutionized overnight if there were worthwhile enterprises to warrant the change, that is, if there were a social impetus and enthusiasm to build what everybody agrees is useful and necessary.

Consider what this means for community planning on any scale. We could centralize or decentralize, concentrate population or scatter it. If we want to continue the trend away from the country, we can do that; but if we want to combine town and country values in an agrindustrial way of life, we can do that. In large areas of our operation, we could go back to old-fashioned domestic industry with perhaps even a gain in efficiency, for small power is everywhere available, small machines are cheap and ingenious, and there are easy means to collect machined parts and centrally assemble them. If we want to lay our emphasis on providing still more mass-produced goods, and raising the standard of living still higher, we can do that; or if we want to increase leisure and the artistic culture of the individual, we can do that. We can have solar machines for hermits in the desert like Aldous Huxley or central heating provided for millions by New York Steam. All this is commonplace; everybody knows it.

It is just this relaxing of necessity, this extraordinary flexibility and freedom of choice of our techniques, that is baffling and frightening to people. We say, “If we want, we can,” but offered such wildly possible alternatives, how the devil would people know what they want? And if you ask them—as it was customary after the war to take polls and ask, “What kind of town do you want to live in? What do you want in your post-war home?”—the answers reveal a banality of ideas that is hair-raising, with neither rational thought nor real sentiment, the conceptions of routine and inertia rather than local patriotism or personal desire, of prejudice and advertising rather than practical experience and dream.

Technology is a sacred cow left strictly to (unknown) experts, as if the form of the industrial machine did not profoundly affect every person; and people are remarkably superstitious about it. They think that it is more efficient to centralize, whereas it is usually more inefficient. (When this same technological superstition invades such a sphere as the school system, it is no joke.) They imagine, as an article of faith, that big factories must be more efficient than small ones; it does not occur to them, for instance, that it is cheaper to haul machined parts than to transport workmen.

Indeed, they are outraged by the good-humored demonstrations of Borsodi that, in hours and minutes of labor, it is probably cheaper to grow and can your own tomatoes than to buy them at the supermarket, not to speak of the quality. Here once again we have the inevitable irony of history: industry, invention, scientific method have opened new opportunities, but just at the moment of opportunity, people have become ignorant by specialization and superstitious of science and technology, so that they no longer know what they want, nor do they dare to command it. The facts are exactly like the world of Kafka: a person has every kind of electrical appliance in his home, but he is balked, cold-fed, and even plunged into darkness because he no longer knows how to fix a faulty connection.

Certainly this abdication of practical competence is one important reason for the absurdity of the American Standard of Living. Where the user understands nothing and cannot evaluate his tools, you can sell him anything. It is the user, said Plato, who ought to be the judge of the chariot. Since he is not, he must abdicate to the values of engineers, who are craft-idiots, or—God save us!—to the values of salesmen. Insecure as to use and value, the buyer clings to the autistic security of conformity and emulation, and he can no longer dare to ask whether there is a relation between his Standard of Living and the satisfactoriness of life. Yet in a reasonable mood, nobody, but nobody, in America takes the American standard seriously. (This, by the way, is what Europeans don’t understand; we are not such fools as they imagine-we are far more at a loss than they think.)

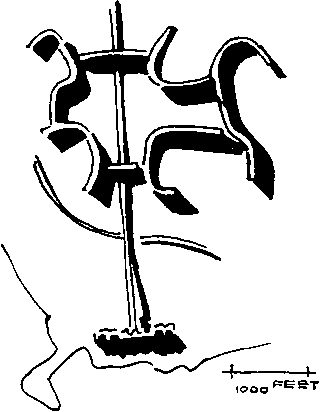

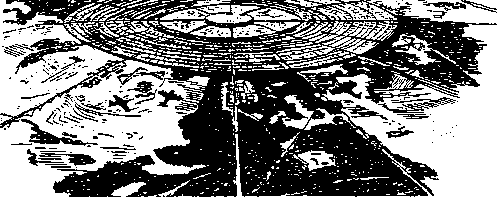

Still Another Obstacle

We must mention still another obstacle to community planning in our times and a cause of the dull and unadventurous thinking about it: the threat of war, especially atomic war. People feel—and they are bang right—that there is not much point in initiating large-scale and long-range improvements in the physical environment, when we are uncertain about the existence of a physical environment the day after tomorrow. A sensible policy for highways must be sacrificed to the needs of moving defense. Nor is this defeated attitude toward planning relieved when military experts come forth with spine-tingling plans that propose the total disruption of our present arrangements solely in the interest of minimizing the damage of the bombs. Such schemes do not awaken enthusiasm for a new way of life.

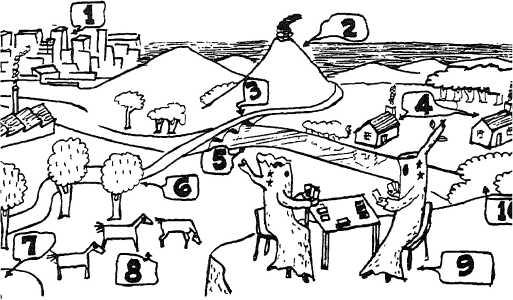

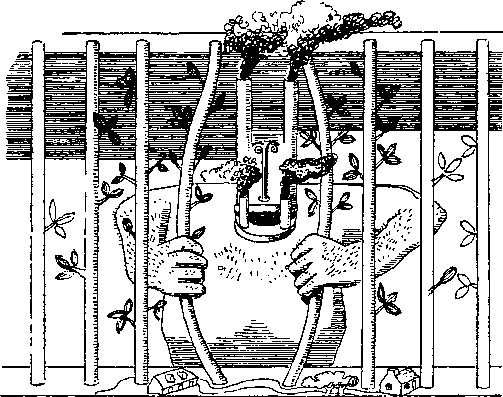

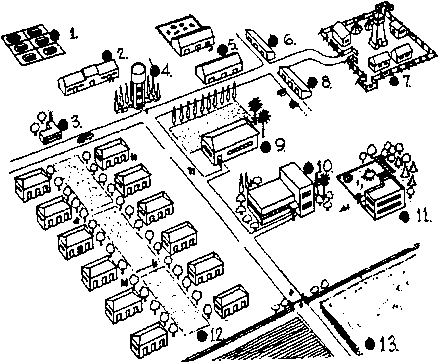

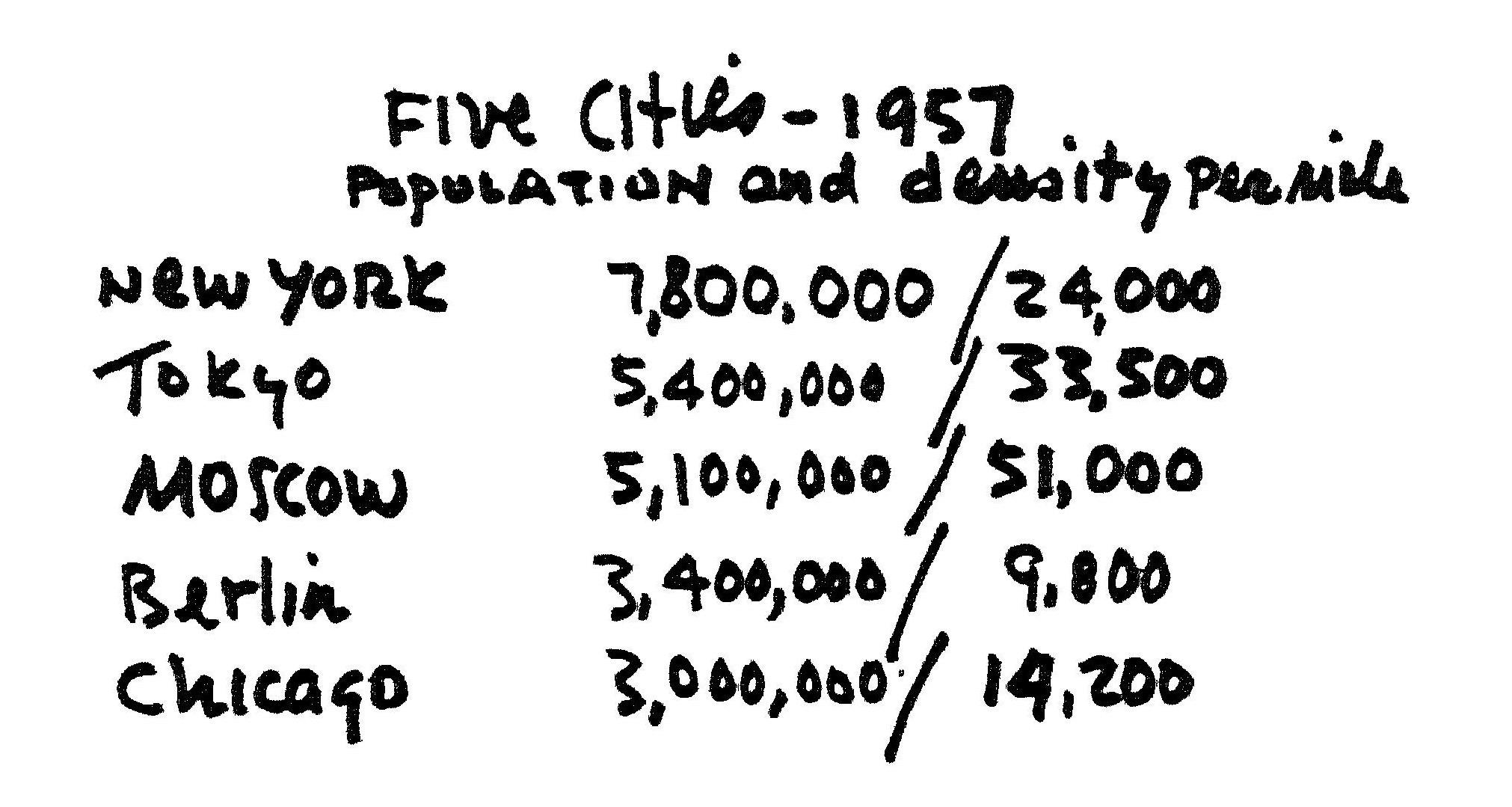

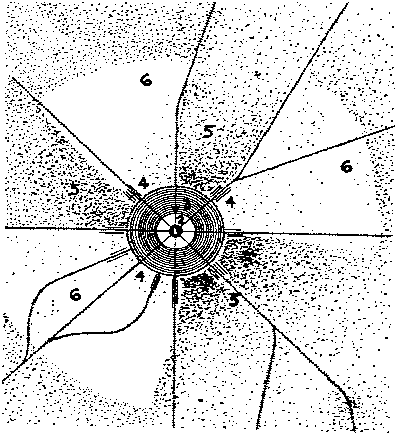

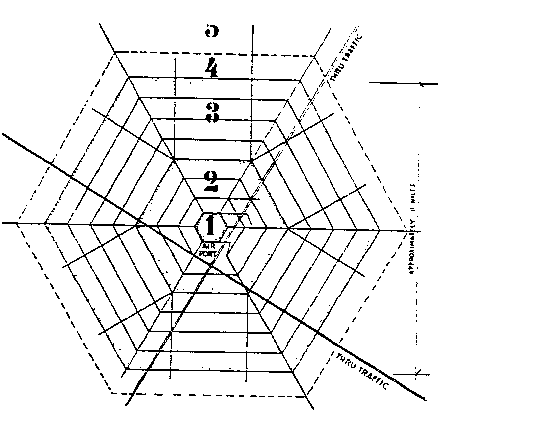

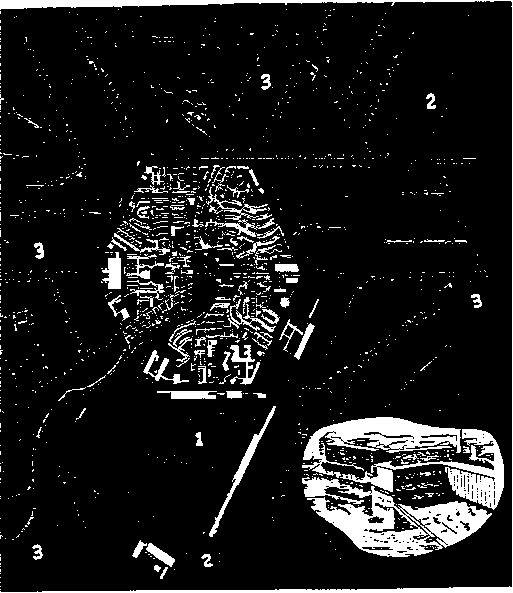

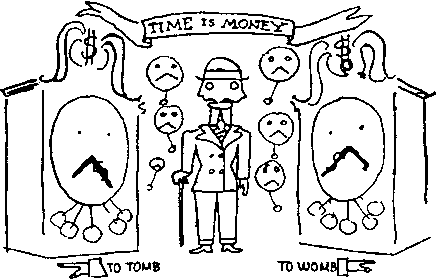

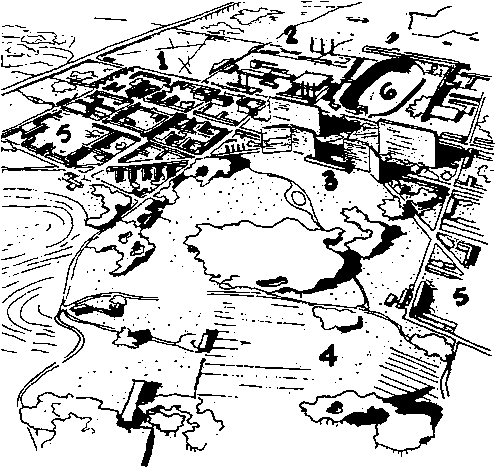

1. Abandoned city, could serve as decoy 2. Factory 3. Rocket Launching Platform 4. Entrances to Factory 5. Road under 6. Dwellings 7. Landing field 8. Trojan horses 9. Staff meeting 10. G.H.Q.

But even worse than this actual doubt, grounded in objective danger, is the world-wide anxiety that everywhere produces conformity and brain washed citizens. For it takes a certain basic confidence and hope to be able to be rebellions and hanker after radical innovations. As the historians point out, it is not when the affairs of society are at low ebb, but on the upturn and in the burst of revival that great revolutions occur. Now compare our decade since World War II with the decade after World War I. In both there was unheard of productivity and prosperity, a vast expansion in science and technique, a flood of international exchange. But the decade of the 20’s had also one supreme confidence, that there was never going to be another war; the victors sank their warships in the sea and every nation signed the Kellogg-Briand pact; and it was in that confidence that there flowered the Golden Age of avant-garde art, and many of the elegant and audacious community plans that we shall discuss in the following pages. Our decade, alas, has had the contrary confidence—God grant that we are equally deluded—and our avant-garde art and thought have been pretty desperate.

The future is gloomy, and we offer you a book about the bright face of the future! It is because we have a stubborn faith in the following proposition: the chief, the underlying reason that people wage war is that they do not wage peace. How to wage peace?

The Importance of Planning in Modern Thinking

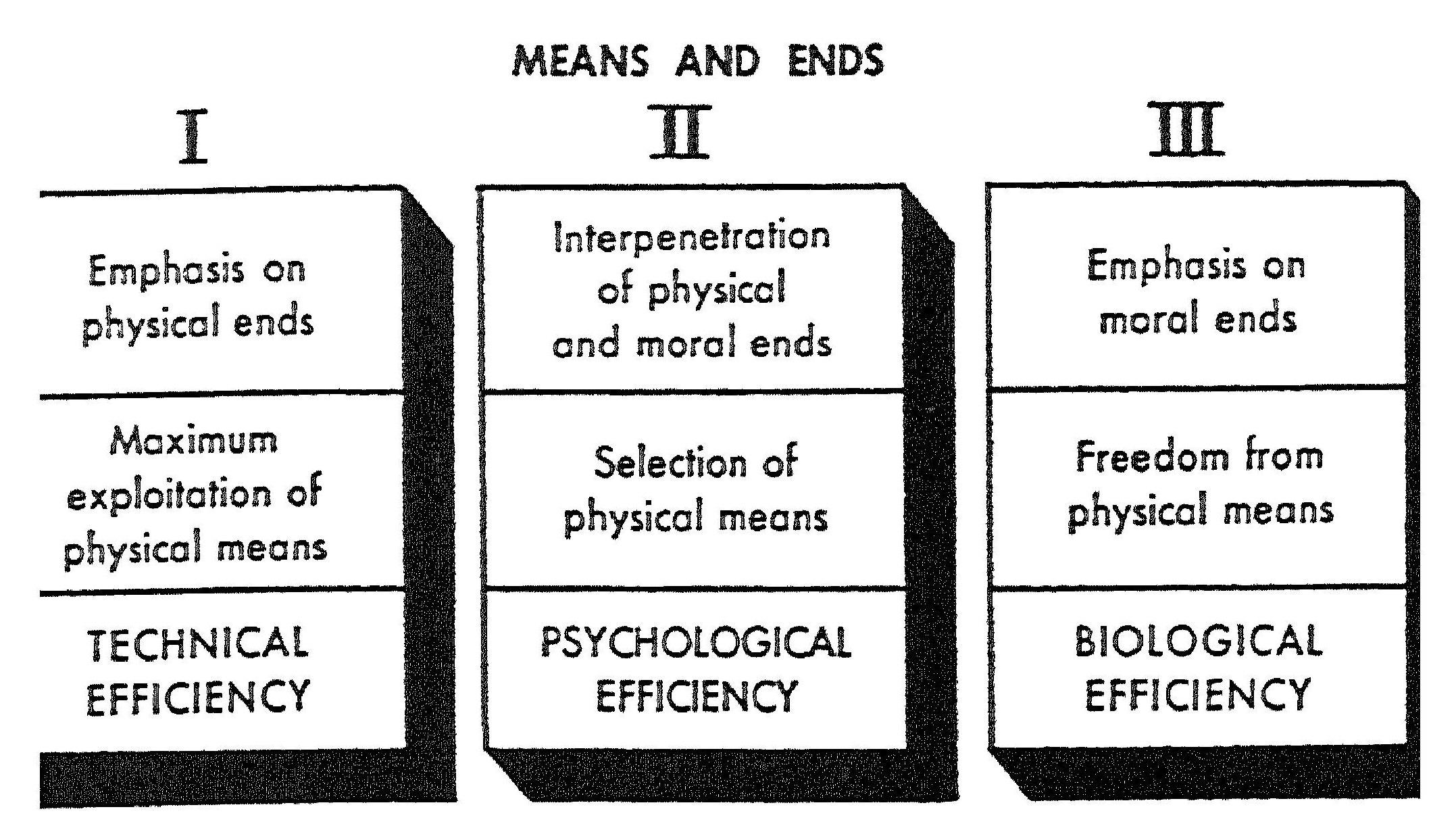

There is an important sense in which physical community planning as a major branch of thought belongs to modern times, to the past hundred years. In every age there have been moral and cultural crises—and social plans like the Republic—send also physical plans to meet economic, ecological, or strategic needs. But formerly the physical plans were simply technical solutions: the physical motions and tangible objects of people were ready means to express whatever values they had; moral and cultural integration did not importantly depend on physical integration. In our times, however, every student of the subject complains, one way or another, that the existing physical plant is not expressive of people’s real values: it is “out of Human scale,” it is existentially “absurd,” it is “paleoTechnological.” Put philosophically, there is a wrong relation between means and ends. The means”are too unwieldy for us, so our ends are confused, for impracticable ends are confused dreams. Whatever the causes, from the earhest plans of the modern kind, seeking to remedy the evils of nuisance factories and urban congestion, and up to the most recent plans for regional development and physical science fiction, we find always the insistence that reintegration of the physical plan is an essential part of political, cultural, and moral reintegration. Most physical planners vastly overrate the importance of their subject; in social change it is not a primary motive. When people are personally happy it is astonishing how they make do with improbable means—and when they are miserable the shiniest plant does not work for them. Nevertheless, the plans discussed in this book will show, we think, that the subject is more important than urban renewal, or even than solving traffic jams.

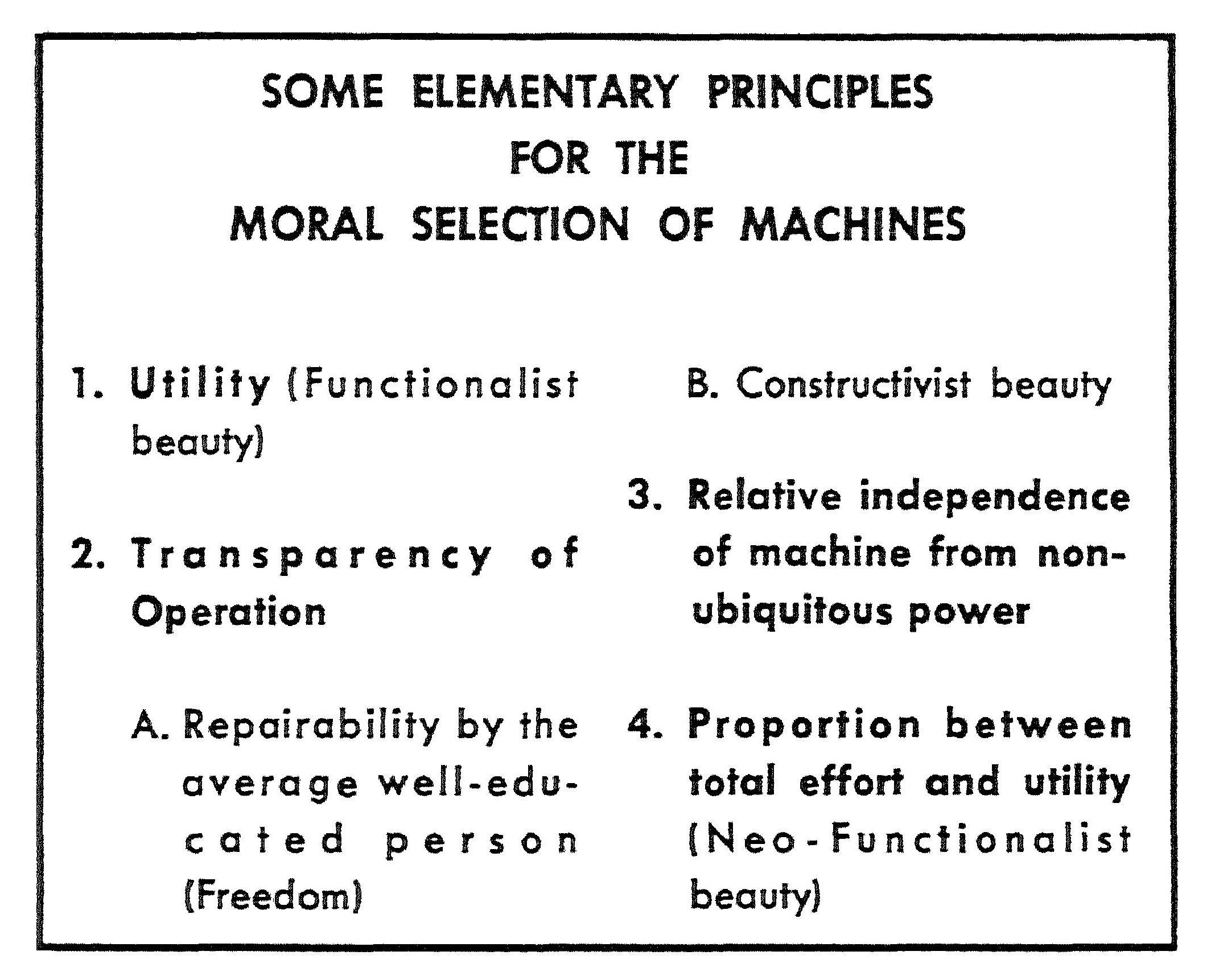

Neo-Functionalism

Finally, let us say something about the esthetic standpoint of this book. The authors are both artists and, in the end, beauty is our criterion, even for community planning, which is pretty close to the art of life itself. Our standpoint is given by the historical situation we have just discussed: the problem for modem planners has been the disproportion of means and ends, and the beauty of community plan is the proportion of means and ends.

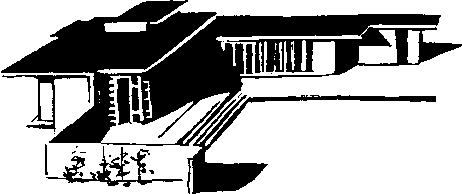

Most of modem architecture and engineering has advanced under the banner of functionalism, “form follows function.” This formula of Louis Sullivan has been subject to two rather contrary interpretations. In Sullivan’s original statement he seemed to mean not that the form grows from the function, but that it is appropriate to it, it is an interpretation of it; he says, “a store must look like a store, a bank must look like a bank.” The formula aims at removing the ugliness of cultural dishonesty, snobbery, the shame of physical function. It is directly in the line of Ibsen, Zola, Dreiser. But it also affirms ideal forms, given by the sensibility of the culture or the imagination of the artist; and this is certainly how it was spectacularly applied by Sullivan’s disciple, Frank Lloyd Wright, who found his shapes in America, in the prairie, and in his personal poetry.

In a more radical interpretation—e.g., of the Bauhaus— the formula means that the form is given by the function: there is to be no addition to the arrangement of the utility, the thing is presented just as it works. In a sense, this is not an esthetic principle at all, for a machine simply working perfectly would not be noticed at all and therefore would not have beauty nor any other sensible satisfaction. But these theorists were convinced that the natural handling of materials and the rationalization of design for mass production must necessarily result in strong elementary and intellectual satisfactions: simplicity, cleanliness, good sense, richness of texture. The bread-and-butter values of poor people who have been deprived, but know now what they want.

Along this path of interpretation, the final step seemed to be constructivism, the theory that since the greatest and most striking impression of any structure is made by its basic materials and the way they are put together, so the greatest formal effect is in the construction itself, in its clarity, ingenuity, rationality, and proportion. This is a doctrine of pure esthetics, directly in the line of post-impressionism, cubism, and abstract art. In architecture and engineering it developed from functionalism, but in theory and sometimes in practice it leaped to the opposite extreme of having no concern with utility whatever. Much constructivist architecture is best regarded primarily as vast abstract sculpture; the search of the artist is for new structural forms, arbitrarily, whatever the function. Often it wonderfully expresses the intoxication with new technology, how we can freely cantilever anything, span any space. On the other hand, losing the use, it loses the intimate sensibility of daily life, it loses the human scale.

We therefore, going back to Greek antiquity, propose a different line of interpretation altogether: form follows function, but let us subject the function itself to a formal critique. Is the function good? Bona fide? Is it worthwhile? Is it worthy of a man to do that? What are the consequences? Is it compatible with other, basic, human functions? Is it a forthright or at least ingenious part of life? Does it make sense? Is it a beautiful function of a beautiful power? We have grown unused to asking such ethical questions of our machines, our streets, our cars, our towns. But nothing less will give us an esthetics for community planning, the proportioning of means and ends. For a community is not a construction, a bold Utopian model; its chief part is always people, busy or idle, en masse or a few at a time. And the problem of community planning is not like arranging people for a play or a ballet, for there are no outside spectators, there are only actors; nor are they actors of a scenario but agents of their own needs—though it’s a grand thing for us to be not altogether unconscious of forming a beautiful and elaborate city, by how we look and move. That’s a proud feeling.

What we want is style. Style, power and grace. These come only, burning, from need and flowing feeling; and that fire brought to focus by viable character and habits.

This, then, is a book about the issues important in community planning and the ideas suggested by the planners. Our aim is to clarify a confused subject, to heighten the present low level of thinking; it is not to propose concrete plans for construction in particular places. We are going to discuss many big schemes, including a few of our own invention; but our purpose is a philosophical one: to ask what is socially implied in any such scheme as a way of life, and how each plan expresses some tendency of modern

mankind. Naturally we too have an idea as to how we should like to live, but we are not going to try to sell it here. On the contrary! At present any plan will win our praise so long as it is really functional according to the criterion we have proposed: so long as it is aware of means and ends and is not, as a way of life, absurd.

A great plan maintains an independent attitude toward both the means of production and the standard of living. It is selective of current technology because how men work and make things is crucial to how they live. And it is selective of the available goods and services, in quantity and quality, and in deciding which ones are plain foolishness.

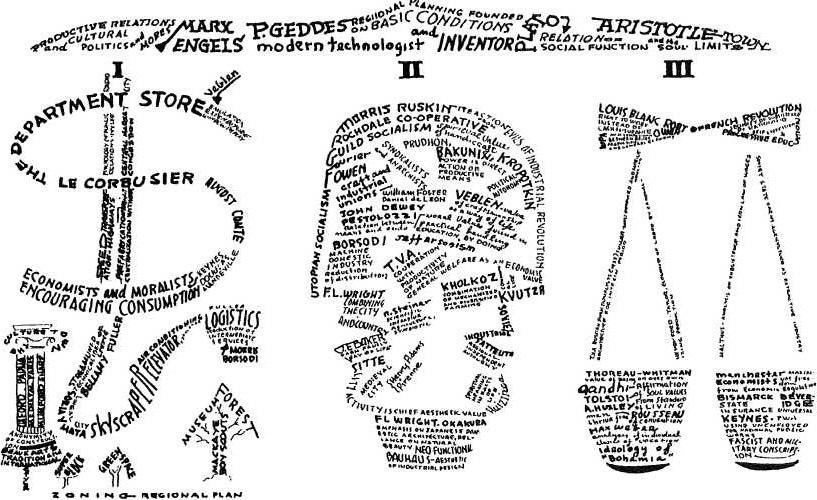

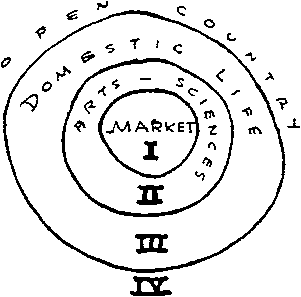

From the vast and curious literature of this subject during the past century, we have chosen a manual of great modern plans, and arranged them according to the following principle: What is the relationship between the arrangements for working and the arrangements for “living” (animal, domestic, avocational, and recreational)? What is the relation in the plan between production and consumption? This gives us a division into three classes:

A.

The Green Belt—Garden Cities and Satellite Towns; City neighborhoods and the Ville Radieuse;

B.

Industrial Plans—the Plan for Moscow; the Lineal City; Dymaxioh;

C.

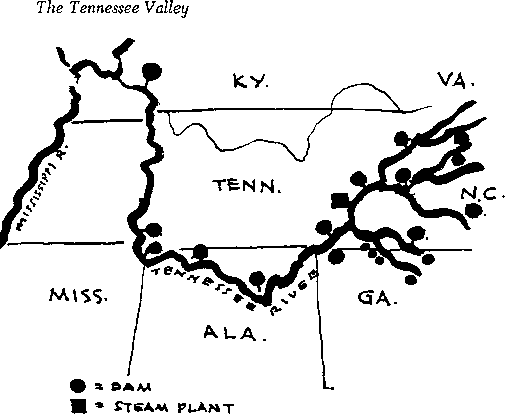

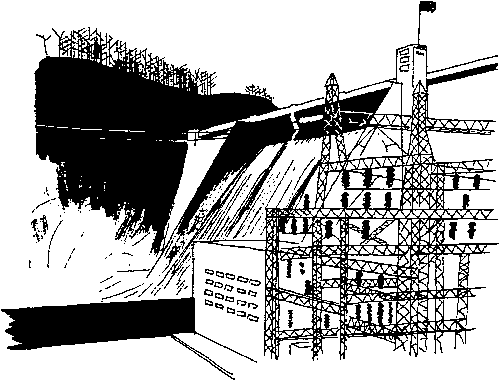

Integrated Plans—Broadacres and the Homestead; the Marxist regional plan and collective farming; the T.V.A.

The first class, controlling the technology, concentrates on amenity of living; the second starts from arrangements for production and the use of technology; the third looks for some principle of symbiosis. It does not much matter whether we have chosen the most exciting or influential examples—though we have chosen good ones—for our aim is to bring out the principle of interrelation. Certainly we do not treat the plans in a way adequate to their merit, for they were put forth as practical or ideally practical schemes—some of them were put into effect—whereas we are using them as examples for analysis.

The questions we shall be asking are: What do these plans envisage about:

Kind of technology?

Attitude toward the technology?

Relation of work and leisure?

Domestic life?

Education of children and adults?

Esthetics?

Political initiative?

Economic institutions?

Practical realization?

By asking these questions of these modern plans, we can collect a large body of important issues and ideas for the inductions that we then draw in the second part of this book.

Part I: A Manual of Modern Plans

Chapter 2: The Green Belt

The original impulse to Garden City planning was the reaction against the ugly technology and depressed humanity of the old English factory areas. On the one hand, the factory poured forth its smoke, blighted the countryside with its refuse, and sucked in labor at an early age. On the other, the homes were crowded among the chimneys as identical hives of labor power, and the people were parts of the machine, losing their dignity and sense of beauty. Some moralists, like Ruskin, Morris, and Wilde reacted so violently against the causes that they were willing to scrap both the technology and the profit system; they laid their emphasis on the beauty of domestic and social life, making for the most part a selection of pre-industrial values. Ruskin praised the handsome architecture of the Middle Ages, said things should not be made of iron, and campaigned for handsome tea cannisters. Morris designed furniture and textiles, improved typography, and dreamed of society without coercive law. Wilde (inspired also by Pater) tried to do something about clothing and politics and embarked on the so-called “esthetic adventure.” What is significant is the effort to combine large-scale social protest with a new attitude toward small things.

Less radically, Ebenezer Howard, the pioneer of the Garden City, thought of the alternative of quarantining the technology, but preserving both the profit system and the copiousness of mass products: he protected the homes and the non-technical culture behind a belt of green. This idea caught on and has been continually influential ever since. In all Garden City planning one can detect the purpose of safeguard, of defense; but by the same token, this is the school that has made valuable studies of minimum living standards, optimum density, right orientation for sunlight, space for playgrounds, the correct designing of primary schools.

Plans which in principle quarantine the technology start with the consumption products of industry and plan for the amenity and convenience of domestic life. Then, however, by a reflex of their definition of what is intolerable and substandard, in domestic life, they plan for the convenience and amenity also of working conditions, and so they meet up with the stream of the labor movement.

With the coming of the automobiles there was a second impulse to Garden City planning. To the original ugliness of coal was added the chaos of traffic congestion and traffic hazard. But there was offered also the opportunity to get away faster and farther. The result has been that, whereas for Howard the protected homes were near the factories and planned in conjunction with them, the entities that are now called Garden Cities are physically isolated from their industry and planned quite independently. We have the interesting phenomena of commutation, highway culture, suburbanism, and exurbanism.

The chief property of these plans, then, is the setting-up of a protective green belt, and the chief difference among the plans depends on how complex a unity of life is provided off the main roads leading to the industrial or business center.

We are now entering a stage of reflex also to this second impulse of suburbanism: not to flee from the center but to open it out, relieve its congestion, and bring the green belt into the city itself. This, considered on a grand scale, is the proposal of the Ville Radieuse of Le Corbusier. Considered more piecemeal, it employs the principle of enclosed traffic-free blocks and the revival of neighborhoods, as proposed by disciples of Le Corbusier, like Paul Wiener, or housers like Heniy Wright.

From Suburbs to Garden Cities

From the countryside, the scattered people crowd into cities and overcrowd them. There then begins a contrary motion.

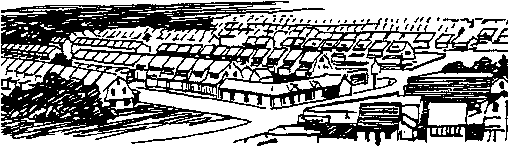

Consider first the existing suburbs. These are unorganized settlements springing up on the main highway and parallel railway to the city. They take advantage of the cheaper land far from the center to build chiefly one-family houses with private yards. The productive and cultural activity of the adults and even adolescents is centered in the metropolis; it is only the children who belong strictly to the suburb as such. The principal civic services—paving, light, water—are directed by the city; and the land is surveyed according to the prevailing city plan, probably in a grid. The highway to the city is the largest street and contains the shops.

Spaced throughout the grid are likely to be small developments of private real estate men, attempting a more picturesque arrangement of the plots. But on the whole the pressure for profit is such that the plots become minimal and the endless rows of little boxes, or of larger boxes with picture windows, are pretty near the landscape of Dante’s first volume.

Such development is originally unplanned. It is best described in the phrase of Mackaye as “urban backflow.” The effect of it is, within a short time, to reach out toward the next small or large town and to create a still greater and more planless metropolitan area. This is the ameboid spreading that Patrick Geddes called conurbation.

Culturally, the suburb is too city-bound to have any definite character, but certain tendencies are fairly apparent —caused partly by the physical facts and partly, no doubt, by the kind of persons who choose to be suburbanites. Families are isolated from the more diverse contacts of city culture, and they are atomized internally by the more frequent absence of the wage earner. On the other hand, there is a growth of neighborly contacts. Surburbanites are known as petty bourgeois in status and prejudice, and they have the petty bourgeois virtue of making a small private effort, with its responsibilities. There is increased dependency on the timetable and an organization of daily life probably tighter than in the city, but there is also the increased dignity of puttering in one’s own house and maybe garden. (It has been said, however, that the majority dislike the gardening and keep up the lawn just to avoid unfavorable gossip.) There is no local political initiative, and in general politics there is a tendency to stand pat or retreat.

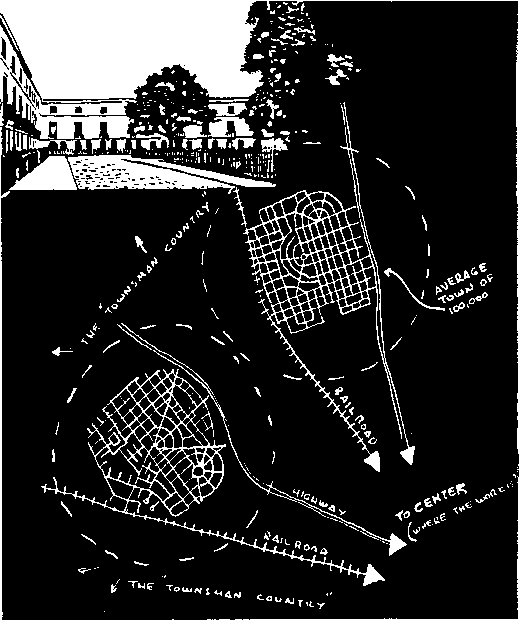

When this suburban backflow is subjected to conscious planning, however, a definite character promptly emerges. Accepting such a tendency as desirable, the city makes political and economic decisions to facilitate it by opening fast highways or rapid-transit systems from the center to the outskirts. An example is the way the New York region has been developed. The effect is to create blighted areas in the depopulated center, to accelerate conurbation at the periphery and rapidly depress the older suburbs, choking their traffic and destroying their green; but also to open out much further distances (an hour away on the new highways) where there is more space and more pretentious housing. This is quite strictly a middle-class development; for the highways draw heavily on the social wealth of everybody for the benefit of those who are better off, since the poor can afford neither the houses nor the automobiles.

This matter is important and let us dwell on it a moment. A powerful Park Commissioner has made himself a vast national reputation by constructing many such escape-highways: they are landscaped and have gas-stations in quaint styles; this is “a man who gets things done.” He has done our city of New York a disastrous disservice, in the interests of a special class. Imagine if this expenditure had been more equitably divided to improve the center and make liveable neighborhoods, as was often suggested. The situation in the New York region is especially unjust. Those who can afford to live in Nassau or Westchester Counties are able to avoid also the city sales and other taxes, although parasitically they enjoy the city’s culture; yet, having set up a good swimming pool across the city’s northern border, the people of Westchester have indignantly banned its use to Negroes, Puerto Ricans, and other poor boys, since they made it “for their own people.” The general outlook of these rich parkway-served counties is that of ignorant, smug parasites.

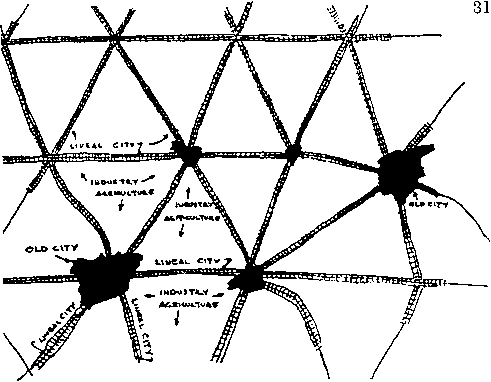

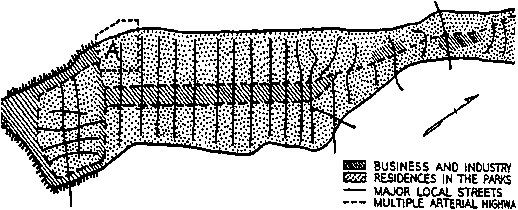

A more rational inference from the suburban impulse is the idea of the Ciudad Lineal (after Soria y Mata), proposed as long ago as 1882 for the development of the outskirts of Madrid. The Lineal City, continuous roadside development, is the planned adaptation of existing “ribbon development,” the continuous dotting of habitations along any road. It avoids the high rent and congestion of the city, has easy access to the city, and it minimizes the invasion of the forest and countryside, which begin immediately beyond the street off the highway. It is essentially a European invention, for this is in fact the form of the villages of Italy, France, Spain, or Ireland: row-housing on both sides of the highroad, and the peasants’ fields out the back door (whereas the English and Americans have historically spread over the fields with detached houses). The chief importance of the Lineal City, however, is not residential but industrial; it is the simplest analysis of the always present and always major factor of transportation (see later, plan of the disurbanists, p. 71)—a remarkable invention to have been made before the coming of the automobile.

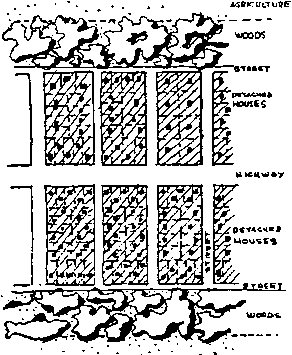

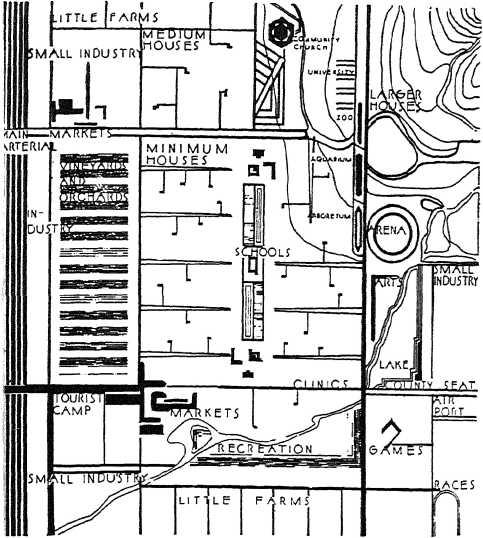

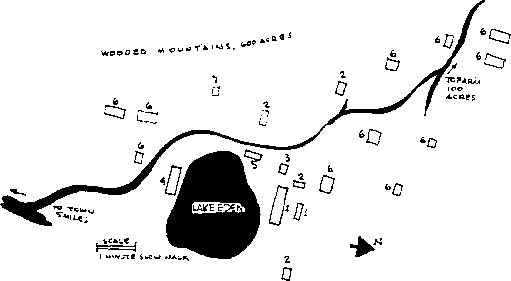

The climactic development of the suburban impulse in the English or American style is the Garden City in the form in which it is now laid out. This is a unified residential community of a size “sufficient for a complete social life,” with row as well as detached houses, but mainly detached houses with small gardens, and with its center off the highway.

Garden Cities

The classic Garden City, Letchworth (architects: Parker and Unwin, after Howard), is a place of light industry. But let us here speak rather of places completely dependent on commuting, e.g., Radburn (Stein), Welwyn (Unwin), or the New Deal Greenbelt, Greendale, etc. Radburn aims at a population of 25,000. After 35 years, Letchworth numbered 17,000.

The following exposition is taken from the well-known book of Raymond Unwin, Town Planning in Practice (1907; rev. ed. 1932). He is concerned throughout with residential convenience and amenity. On industry his first and last word is, “We shall need power to reserve suitable areas for factories, where they will have every convenience for their work and cause the minimum of nuisance.” One is struck by the expression “their work” rather than “our work.”

Amenity. It is by adding amenity to physical convenience, says Unwin, that we get a Garden City. This curious British term, variously applied by every English planner, and imitated by the Americans, means decency, charm of appearance and privacy. To Unwin its first implication is zoning: segregation from industry and business, and the restriction of density to “twelve families to the acre”; further, it implies planning with an esthetic purpose.

He proceeds to formal and informal plans, a distinction borrowed from English gardening. He himself prefers the formal or T-square and compass plan, obviously thinking of the delightful squares and crescents of London. (American designers, reacting to our undelightful gridirons, prefer ameboid shapes.) Next he speaks of problems of streetlayout and the arrangement of public plazas. (American designers, faced with a heavy volume of through traffic, employ the cul-de-sac.) Next, the uniformity of materials for general effect. On this point, one is struck with the remembrance of the lovely uniformity of old French or Irish villages, a natural uniformity created by having to use local building materials; but in the Garden City we come to a situation of surplus means and planned uniformity to avoid chaos of the surplus. Next, Unwin cites the unity of design of the separate blocks of houses.

Unwin devotes his last chapter to an idea of great value: neighborly cooperation. Planning, he says, is cooperative in its essence. It starts with the location of the necessities of the community as a whole—its schools, shops, institutes. It modifies the individual or suburbanite taste to its plazas and prospects. It proposes the orientation and construction of houses. It suggests the summation of private gardens into orchards, and perhaps a common. By cooperation all can have “a share of the convenience of the rich ... if we can overcome the excessive prejudice which shuts up each family and all its domestic activities within the precincts of its own cottage.” He asks for the common laundry and nursery, common library, common services. “More difficult is the question of the. common kitchen and dining hall.” Indeed more difficult! For along this line of community commitment there opens up a new way of life altogether, with strong political consequences.

Unwin’s book is admirably reasoned and well written; but how are the suburbanites of the beginning to become the fellowship of the end? Given the usual private or governmental projectors, unity of planning means sameness, and social landscaping means the restriction of children from climbing the trees like bad citizens. From the start he has isolated his community from the productive work of society. The initiative to cooperation does not rise from, nor reach toward, political initiative that always resides in the management of production and distribution. How far would that cooperation get?

What is the culture of Garden Cities? The community spirit belongs, evidently, to those who stay at home. As the suburb belongs to the children, here the community belongs to the children and some of the women. The women are neighborly; according to recent statistics, they spend ten hours a week playing cards and are active on committees. The men spend a good deal of the time on the prefabricated craftsmanship that we call “Do It Yourself.” There is golf, for talking business or civil service. These are the topics of conversation because a lustier workman is not likely to divert so much of his time and income from the more thrilling excitements of the city, such as they are; and rather than live in a Garden City, an intellectual would rather meet a bear in the woods.

obvius leoni!

Satellite Towns

To meet some of these objections the English planners have invented Satellite Towns, in a serious effort to plan for a culture full-blown rather than a week-end somnolescence. To recover a true urbanism from the man-eating megalopolis; and also to rescue from suburbia the countryside and the woods.

It seems to have been this latter purpose—the reaction to the fact that the spread-out Garden Cities encroach on the rural land—that has led the more recent generation of English planners, for example Thomas Sharp, to dissent from Howard. Whereas neither Howard nor Unwin has anything to say about the country as such, Sharp in his Town Planning devotes as much space to the amenity of the country as to the amenity of the town. Perhaps this reflects the great problem of an England stripped of its empire and needing to become more agriculturally self-sufficient.

(In America we have had the fine work of Mackaye, the creator of the Appalachian Trail. He is concerned to preserve the aboriginal woods as the vivifier of city life. Sharp too has a chapter on national parks for hikers and campers.)

Satellite towns are thought of as having a population of 100,000, where even Letchworth with its mills has less than 20,000. The “complete social life” of the Garden City is not a cultural life at all, for high culture is a defining property of cities. (A vast industrial concentration is not a city either, of course.)

More than any other plan the Satellite Town depends on belts of green, for the green must hem in not only the industrial center but also town from town, to protect the urban unity of each; and finally it must protect even the unity of the countryside.

A satellite town, then, is a true city economically dependent on a center and therefore on its highway, but laid out as if integral and self-sufficient. The ideal of the layout is taken directly from the squares and crescents of Christopher Wren and the Brothers Adam. The style proposed by Sharp is the “various monotony” of an eighteenth-century block, each of whose doorways and fan-windows is studied, the symbol that a man’s home, not his house, is his castle. Country houses, too, have urban dignity, and the fields have humane hedgerows.

At its worst the culture of such a place would be exclusive and genteel, but at its best it would be the culture of little theaters. Now little theater is not amateurish, not the lawn pageant that belongs to the complete social life of Garden Cities; nor is it prefabricated “Do It Yourself”; nor again, of course, is it professional (and standardized) entertainment for broad masses. It is devoted to objective art, the use of the best modern means, and it cultivates its participants. Primary education would be progressive and independent, and higher education would teach the best that has been thought and said and study “monuments of its own magnificence.” The countryside demonstrates how man can humanize nature and is a source of decent, not canned, food; and the national park revives us with the forthright causality of the woods. All conspires to the spiritual unity of the soul and the cultural unity of mankind (it is essential to the idea to mingle the economic classes)—all except the underlying work and techniques of society on which everything depends not only economically but in every big political decision and in the style of every object of use: these have no representation.

We are here in the full tide of cultural schizophrenia. When the suburbanite or Garden Citizen returns from the industrial center, it is with a physical release and a reawakening of cowering sensibilities. But the culture-townsman has raised his alienation to the level of a principle. What reintegration does he offer? The culture-townsman declares that we must distinguish ends and means, where industry is the means but town life is the end. Trained in his town to know what he is about, the young man can then turn to the proper ordering of society. In America this was fairly explicitly the program of Robert Hutchins. The only bother is that one cannot distinguish ends and means in this way and the attempt to do so emasculates the ends. Under these conditions, art is cultivated but no works of art can be made; science is studied but no new propositions are advanced; and living is central but there is no social invention. (But to be just, do we see any other communities that guarantee these excellent things?)

The form in which, at present, this plan is partly realized is the college campus and its neighborhood. It is a plan not for the children and women, but for the ephebes of both sexes and all ages. For the adults it is a conception appropriate to endowed rather than current wealth, and suspicious of change.

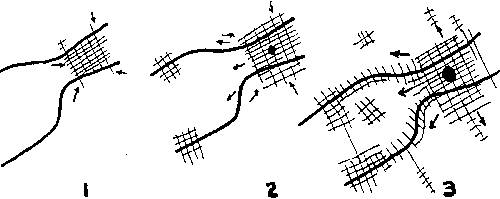

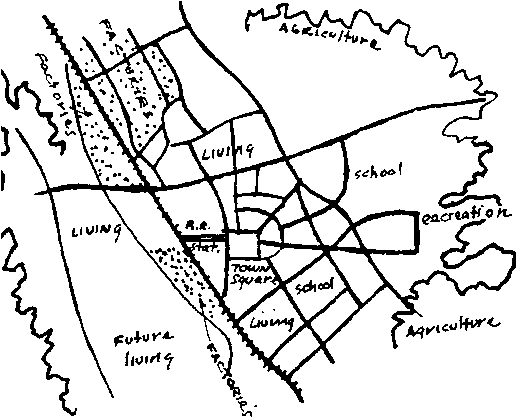

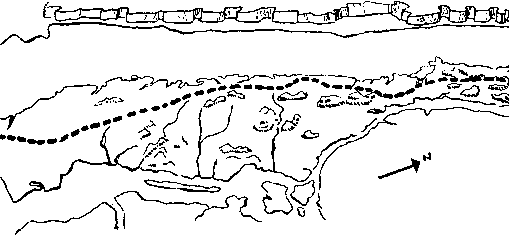

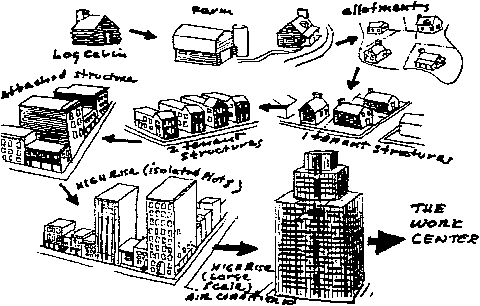

The Evolution of Streets from Village to City

We can tell the story of the inflow and backflow of a metropolitan population simply as a history of streets.

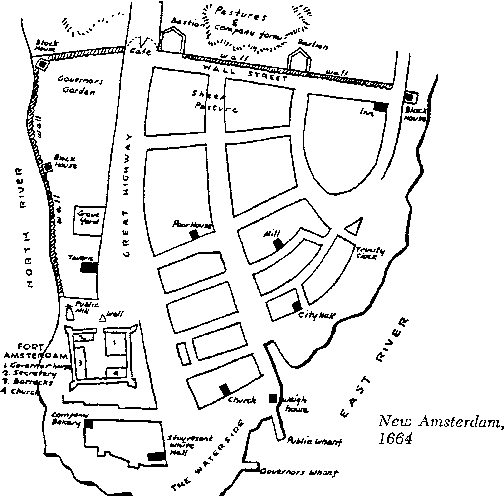

Starting new on Manhattan, in a territory from their point of view undeveloped, the Dutch first built a little town dependent on its own agriculture and on the commerce in furs. Their square faced on the dock, it was the place of the overseas market, of the imported government, and soon of the community church and school. People lived on small farms.

1664

As the commerce grew and attracted greater numbers, the original faims were subdivided for simple residence, and the farmers, more ambitious because their products were in demand both abroad and at home, took possession of great domains throughout the island and northward. They now found that the territory had already been somewhat laid out by the aborigines, and they made use of the main Indian trail, which to the Indians had run in the opposite direction toward their capital at Dobbs Ferry. (The way facing toward Europe was not so obviously downtown for the Indians.) And it is striking how many features of the aboriginal layout, topologically determined, persist in the modern city, though the topology itself has been much changed. The original lanes and highways of the Indians and the patroon proprietors formed the basis of some of the avenues of later days.

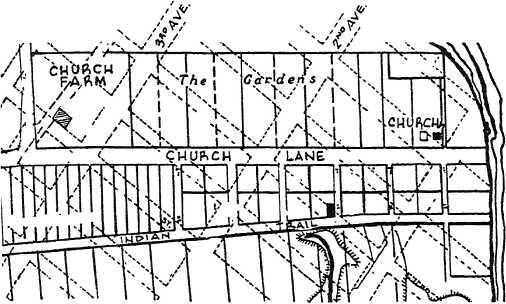

Very early some of the larger domains were subdivided and occupied as villages of the growing town. The first such was New Haarlem.

Finally, after the vicissitudes of the English occupation and the American Revolution, it was clear’ that none of the thriving commercial island would remain farm land, it would all be subdivided for commerce, manufacture, and residence. In 1807 almost the whole area was surveyed as a gridiron, that lay across the aboriginal paths and the early lanes and roads, unable to alter either the stronger topological features or the areas already built up, but dominating the future.

The rectangles of 1807 were subdivided by real estate speculators into the lots and back alleys of 1907.

But when the subdivision was complete, began the backflow to the outskirts. Under the domination of the center, these outskirts were surveyed in large rectangles and sold in small lots, for instance on Long Island. But since the impulse to suburban settlement is partly to escape the featureless and anonymous network, at least some of the rectangles have been arranged into “developments” with an artificial topology. This brings us back to the composite plan of 1807.

Let the impulse to escape continue, and a Garden City is laid out, off the main highway, deliberately demolishing the gridiron. It is a place of small gardens; the features of the topology again begin to appear; we are back to New Haarlem, except that the small gardens are not really small farms.

Lastly, in the ideal of a culture town, perhaps somewhere in Westchester or in Madison Avenue Connecticut, we return to the integrated town of 1640, built around its plaza. This plaza has perhaps a church, and perhaps a school, but no overseas market and no provincial governor. No farmers. No Indians.

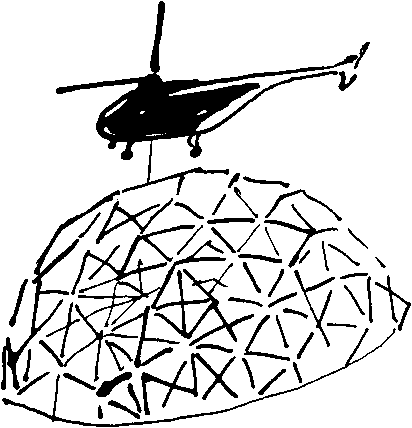

And the plan after the last-is the city without streets. With the advent of the helicopter, this apparently anomalous conception will no doubt come to exist—it has already been suggested by Fuller and others.

Another Version of the Same

Another way of looking at the same history of streets is to consider the steady growth of the old Weckquaesgeck Trail to become the Albany Post Road, then Broadway, then Route 9, and then the great Thruway.

The change to the Thruway is remarkable. For the first time the topological features are disregarded, and so, for the most part, are the settlements of population that are apparently served by the road. Instead, on these great superhighways we see developed a unique culture, with its own colors and eating habits, and a kind of extraterritorial law. Citizens of the Thruway, that stretches from coast to coast, must Go! Go! Not too fast and not too slow. Above all they must not stop. There are also new entities in pathology, such as driver’s instep and falling asleep at the wheel.

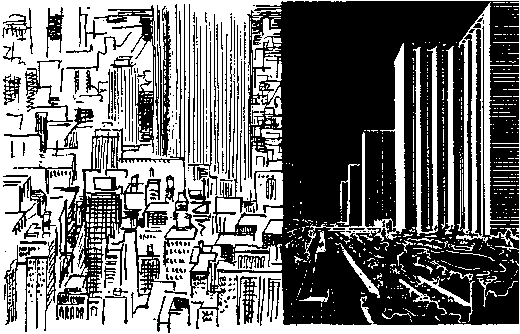

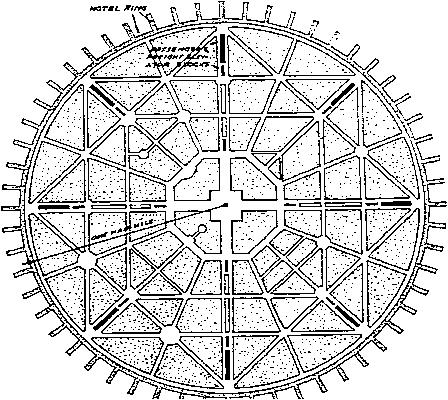

Ville Radieuse

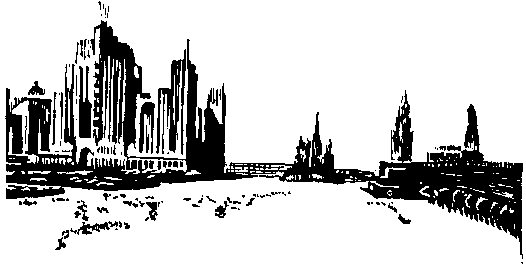

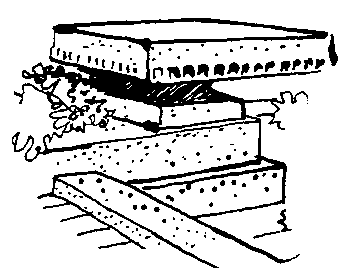

Let us now consider the contrary direction of green belt planning: to invade the center with green and set up Garden Cities in the megalopolis itself. Such a conception involves, of course, immense demolition, it is a surgical operation. And naturally, for such a “cartesian” solution, we must turn to the Ville Radieuse of Le Corbusier, a Frenchman (he is even a Swiss!). For Paris is the only vast city with beauty imposed on her; and Baron Hausmann long ago showed that you must knock down a great deal to get a great result.

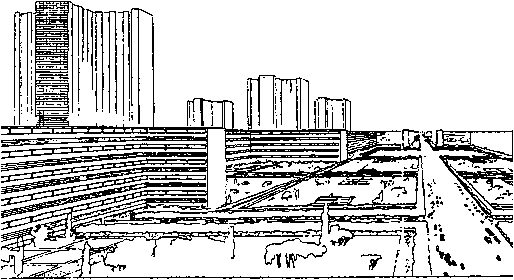

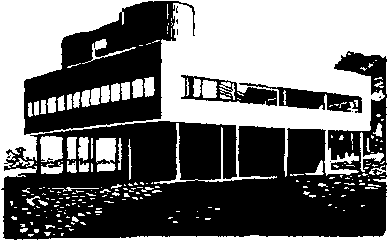

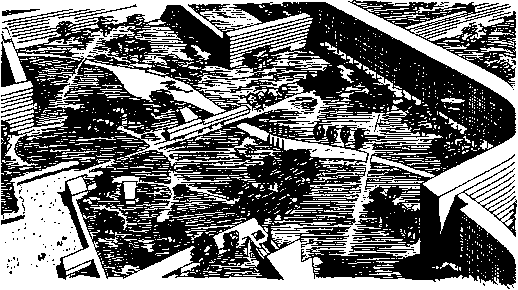

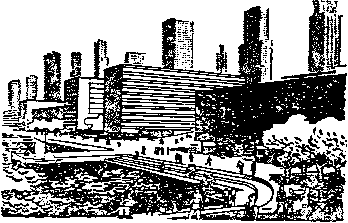

“To de-congest the centers—to augment their density— to increase the means of getting about—to increase the parks and open spaces”: these are the principles of the Ville Radieuse. The plan is extremely simple and elegant: either demolish the existing chaos or start afresh on a new site; lay out in levels highways and tramways radiating from the center; on these erect a few towering skyscrapers every 400 meters at the subway stations; and ring this new opened-out center with large apartment houses for residences, a Cité Jardin, the French kind of Garden City. Industry will be quarantined somewhere “on the outskirts.” (To Paris, Le Corbusier applied this scheme as the Voisin Plan; in the plan for Algiers, he replaced the residential rings by lineal cities.)

This is a prince of plans. It is a typical flower of the twenties, of the Paris International Style. Its daring practicality seems to rejoice in the high capitalism of the “captains of industry,” as Le Corbusier calls them, whose technology and financial resources can accomplish anything. We can see its shapes in Rio and Caracas and, grotesquely misapplied, in New York’s Radio City.

In the central skyscrapers, says the author, are housed the brains and eyes of society. Wherever industry may be located “on the outskirts,” its financial, technical, and political control is in these few towers. Ville Radieuse is a paper city; its activity is the motion of draftsmen, typists, accountants, and meetings of the board. Carried on in an atmosphere of conditioned air, corrected light, and bright decor, by electrical communications, with efficiency and speed. “The city that can achieve speed will achieve success. Work is today more intense and earned on at a quicker rate. The whole question becomes one of daily intercommunication with a view to settling the state of the market jnd the condition of labor. The more rapid the intercommunication, the more will business be expedited.” Had this ever before been so succinctly stated? The passage was written by an architect before the coming of the giant computers and before we had learned to use the magic words “cybernetics” and “feedback.”

Leaving the diffused center, we come to the rings of residence. The inner rings are commodious apartments for the wealthy, innermost like the first tiers at the opera. The outer rings are super-blocks of housing for the average, who travel either inward to the skyscrapers or outward, past the agricultural belt, to the factories.

The residences, great or small, are machines a vivre, machines for living, just as the skyscrapers are machines for communications and exchange, and the streets are machines for traffic. The plan extends inside the walls of the houses to the fittings and furniture. (Contrast this with the English Garden City planners who do not invade these private precincts.) The unit of living is the cell (cellule), standard in construction and layout and arranged for mass servicing. Its furniture, too, is standardized, so that it doesn’t matter in which cell a person lives, “for labor will shift about as needed and must be ready to move, bag and baggage.” The standards are analyzed, however, not only for efficiency but for beauty and amenity-though, in this gipsy economy, domestic amenity is not the fundamental consideration. An outside room or “hanging garden” is provided in the smallest flat. It is a Cité Jardin: the ratio of empty space is large, and there are fields for outdoor sports right at the doorstep, if one had a doorstep.

“There must never come a time,” says our author ominously, “when people can be bored in our city... In general we feel free in our own cell, and reality teaches us that the grouping of cells attacks our freedom, so we dream of a detached house. But it is possible, by a logical ordering of these cells, to attain freedom through order.”

Being standard, every part is capable of mass production. In the English plans, even where the aim was urban uniformity, this was not thought of as mass produced. The manner of construction, like the ideal of small cooperatives, was proper to craft unions. But Le Corbusier, planning for the captains of industry, has only contempt for the mason who “bangs away with feet and hammer.”

Esthetic interest is given by the variety of the grand divisions, seen at large and in long views, the skyscrapers towering on the horizon above the dwellings. “The determining factor in our feelings is the silhouette against the sky.” And we can take advantage of the grand social divisions of rich and poor to give the variety of the sumptuous apartments with their set-back teeth (!-the word is rodents’) as against the rectangles of the workers’ blocks.

The esthetic ideal is the geometric ordering of space, in prisms, straight lines, circles. It is the Beaux Arts’ ideal of the symmetrical plan. The basis of beautiful order is the modulus, whose combinations are countable, so that we should have to simulate mass production even if technical efficiency did not demand it. Space is treated as an undifferentiated whole to be structured: we must avoid topological particularity and build always on a level. (If the site is not level, make a platform on pilotis.) The profile against the sky is the chief ordering of space and the prime determinant of feeling. Space flows inside and outside the buildings; we must use a lot of glass and lay the construction bare. And to insure the clarity and salience of the construction it is best to emphasize a single material, reinforced concrete, and it is even advisable to paint over the surfaces in a single color.

What shall we make of this? In this International Style —of Le Corbusier, Gropius, Oud, Neutra, Mies van der Rohe—there are principles that are imperishable: the analysis of functions, clarity of construction, emphasis on the plan, simplicity of surfaces, reliance on proportion, broad social outlook (whatever the kind of social outlook). It is the best of the Beaux Arts’ tradition revivified and made profound by the politics and sociology of all the years since the fall of Louis XVI.

Yet in this version of Le Corbusier, the Ville Radieuse was the perfecting of a status quo, 1925, that as an ideal has already perished—it died with the great Depression—though as a boring and cumbersome fact it is still coming into being: society as an Organization. Le Corbusier was a poor social critic and a bad prophet. He gets an esthetic effect from a distinction of classes and a spectacular expression of this distinction just when the wealthy class was about to assume a protective camouflage, and indeed just when it was plunging into the same popular movie-culture as everybody else and ceased to stand for anything at all. The brains and eyes of society he calls “captains of industry/’ but their function was to study the market and exploit labor; they were financiers. It was to these captains that he pathetically turned for the realization of his plan; he proposed that international capital invest in the rebuilding of Paris—the increase in land values would give them a quick profit— “and,” he exclaimed, “this will stave off the war, because who would bomb the property in which he has an investment?” As it turned out, the unreconstructed Paris was not bombed.

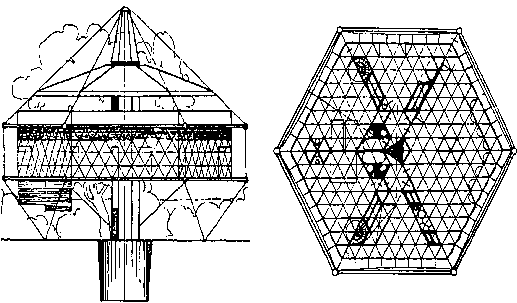

His attitude toward technology is profoundly contradictory. Superficially, the Ville Radieuse makes use of the most advanced means; even the home is a machine. But he suggests nothing but the rationalization of existing means for greater profits in an arena of competition, saying, “The city that can achieve speed will achieve success.” His aim is neither to increase productivity as an economist, nor, by studying the machines and their processes as a technologist, to improve them. Contrast his attitude with that of a technological planner like Buckminster Fuller, who finds in the machinery, for better or worse, a new code of values. Fuller is looking ahead of the technology to new inventions and new patterns of life; Le Corbusier is committed, by perfecting a status quo, to a maximum of inflexibility.

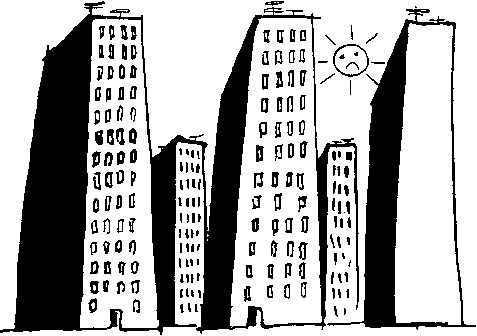

Caught in this Organization, what is the plight of the average man in the Ville Radieuse? The Garden Cities, we saw, were based on the humane intuition that work in which people have the satisfaction neither of direction nor craftsmanship, but merely o£ wages, is essentially unbearable; the worker is eager to be let loose and go far away, he must be protected by a green belt. (There are surveys that show that people do not want to live conveniently near their jobs!) Le Corbusier imagines, on the contrary, that by the negative device of removing bad physical conditions, people can be brought to a positive enthusiasm for their jobs. He is haunted by the thought of the likelihood of boredom, but he puts his faith in freedom through order. The order is apparent; what is the content of the freedom? Apart from a pecular emphasis on athletic sports and their superiority to calisthenics (!), this planner has nothing, but nothing, to say about education, sexuality, entertainment, festivals, politics. Meantime, his citizens are to behold everywhere, in the hugest and clearest expression in reinforced concrete and glass, the fact that their orderly freedom will last forever. It has 500 foot prisms in profile against the sky.

Le Corbusier wages a furious polemic against Camillo Sitte, author of Der Städtebau, who is obviously his bad conscience. He makes Sitte appear as the champion of picturesque scenery and winding roads. But in fact the noble little book of the scholarly Austrian is a theory of plazas, of city-squares; it attempts to answer the question. What is an urban esthetic? For in the end, the great machine of the Ville Radieuse, with all its constructivist beauty, is not a city at all.

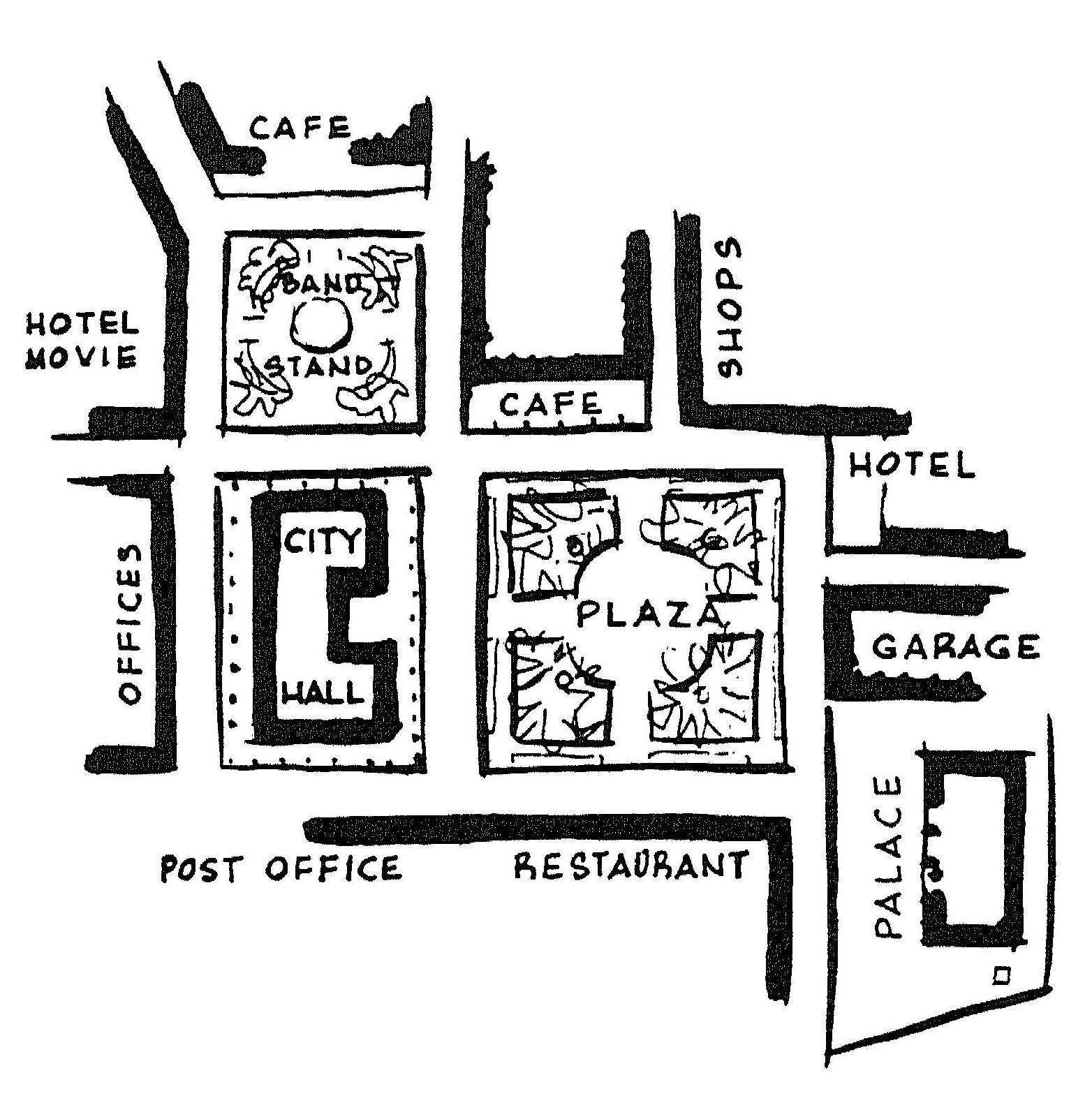

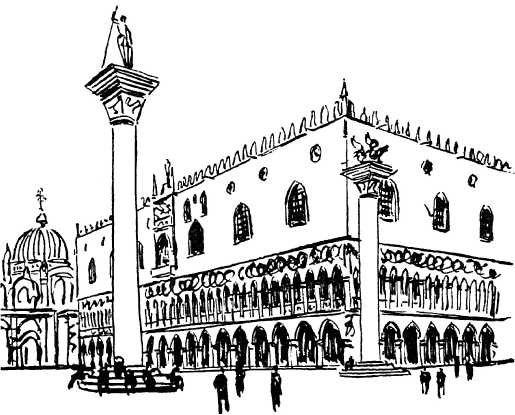

City Squares

A city is made by the social congregation of people, for business and pleasure and ceremony, different from shop or office or private affairs at home. A person is a citizen in the street. A city street is not, as Le Corbusier thinks, a machine for traffic to pass through but a square for people to remain within. Without such squares—markets, cathedral places, political forums—planned more or less as inclosures, there is no city. This is what Sitte is saying. The city esthetic is the beauty proper to being in or entering such a square; it consists in the right choice and disposition o£ structures in and around the square, and in the relation of the squares to one another. This was the Greek, medieval, or Renaissance fact of city life. A Greek, if free and male, was a city man, not a family man or an Organization man; he spent his time on the street, in the law court, at the market.

It is possible that this urban beauty is a thing of the past. Perhaps there are no longer real occasions for social congregation in the square. The larger transactions of business occur at a distance by “communication,” not face to face. Politics is by press, radio, and ballot. Social pleasure is housed in theaters and dance halls. If this is so, it is a grievous and irreparable loss. There is no substitute for the spontaneous social conflux whose atoms unite, precisely, as citizens of the city. If it is so, our city crowds are doomed to be lonely crowds, bored crowds, humanly uncultured crowds.

Urban beauty does not require trees and parks. Classically, as Christopher Tunnard has pointed out, if the cities were small there were no trees. The urban use of trees is formal, like the use of water in fountains; it is to line a street or square, to make a cool spot, or a promenade like the miraculous Stephen’s Green in Dublin. The Bois in Paris is a kind of picnic-ground for the Parisians, it is not a green belt. But when we come to the park systems of London, New York, or Chicago we already have proper green belts whose aim is to prevent a conurbation that would be stifling. (The effect in London and Chicago, of course, is that those cities stretch on and on and it is hard to get from one district to another.) And when finally, as in the Ville Radieuse, the aim is to make a city in the park, a Garden City, one has despaired of city life altogether.

Again, the urban beauty is a beauty of walking; and perhaps it has no place in the age of automobiles and airplanes. This raises the crucial question of standpoint, the point of view, in modern architectural esthetics. Again and again Le Corbusier proves that a place is ugly by showing us the view of the worm-heap from an airplane. Yet then, even the Piazza San Marco or the Piazza dei Signori, in Florence, which he cannot help but admire, merge indistinguishably into the worm-heap. Indeed, from a moving airplane even the Ville Radíense or New York aflame in the night lasts only a few minutes.

If the means of locomotion is walking, the devices described by Sitte—inclosure of streets, placing of a statuecan have a powerful architectural effect. If the means is the automobile, there is still place for architectural beauty, but it will reside mainly in the banking of roads, the landscaping, and the profile on the horizon. When our point of view-is the airplane, however, the resources of architecture are helpless; nothing can impress us but the towering Alps, the towering clouds, or the shoreline of the sea.

The problem, the choice of the means of locomotion, is an important one. For not only Le Corbusier, who has a penchant for the grandiose, but also his opposite number in so many respects, Frank Lloyd Wright, who stays with the human scale—both plan fundamentally for the automobile. Wright’s Broadacres, we shall see, is no more a city than the Ville Radieuse. On the other hand, there are those who cannot forget the vision of Sitte and want to revive the city. Their ideal for the vast metropolis is not a grand profile against the sky but the reconstitution of neighborhoods, of real cities in the metropolis where people go on their own feet and meet face to face in a square.

Housing

With the city squares of Sitte and the conception of neighborhoods as sub-cities, we return full circle from the suburban flight. Seduced by the monumental capitals of Europe, Sitte himself loses his vision and begins to talk about ornamental plazas at the ends of driveways; but the natural development of his thought would be community centers of unified neighborhoods within the urban mass, squares on which open industry, residence, politics, and humanities. (We attempt such an idea in Scheme II below, p. 162.)

An existing tendency in this direction is the community block, planned first as a super-block protected from arterial traffic, as in the Cité Jardin, but soon assuming also neighborly and community functions, analogous to the neighborly cooperation described by Unwin as the essence of the Garden City. Sometimes this development has led in America (as famously in Vienna) to a political banding together of the block residents, making them a thorn in the side of the authorities.

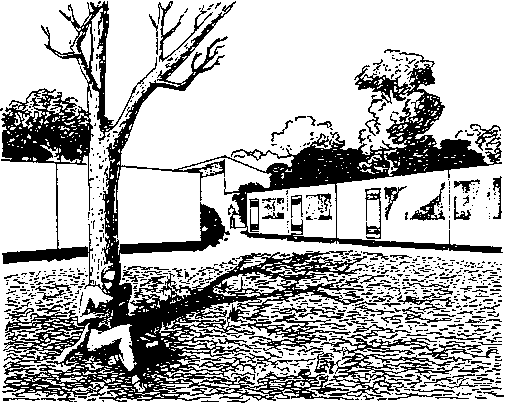

The community-block is now standard practice for all modern urban planners in all countries; but unfortunately, in this planning the emphasis is entirely on housing, and there are experts in applied sociology called “housers.” “Housing” is the reductio ad absurdum of isolated planning. There have been cases of “housing” for workers in new factories where no provision was made for stores in which to buy food. There was a case where there was no road to the industry they worked at. Stuyvesant Town, in New York City, was built to house 8500 families without provision for a primary school. (This wretched plan, financed by a big insurance company with handsome tax relief from the city, was foisted on the city by the Commissioner against the indignant protests of a crashing majority of the city’s architects. There it stands.) In better cases, the block is planned with a school and shops but not in connection with the trade or industry. The cooperative housing just now being constructed by the clothing workers’ union in New York, however, is adjacent to the garment center.

The planning of housing in isolation from the total plan has, of course, been caused by scarcity, slums, war-emergency; and such reform housing has had the good side of setting minimal standards of cubic footage, density of coverage, orientation, fireproofing, plumbing, privacy, controlled rental. The bad side is that the standards are often petty bourgeois. They pretend to be sociologically or even medically scientific, but they are drawn rather closely from the American Standard of Living. The available money is always spent on central heating, elaborate plumbing, and refrigerators rather than on more space or variety of plan or balconies. And the standards are sociological abstractions without any great imaginative sympathy as to what makes a good place to live in for the people who actually live there. They are hopelessly uniform. But where is the uniformity of social valuation that is expressed in the astonishing uniformity of the plans of Housing Authorities? They are not the values of the tenants who come from substandard dwellings from which they resent being moved; they are not the values of the housers, whose homes, e.g., in Greenwich Village, are also usually technically substandard (save when they live in Larchmont). Housers do not inhabit “housing.” Nor is it the case that these uniform projects are cheaper to build. The explanation is simply laziness, dullness of invention, timidity of doing something different.

To connect Housing and slum clearance is also a dubious social policy. Cleared areas might be better zoned for nonfamily housing or not for housing altogether; to decide, it is necessary to have a Master Plan. More important, it is disastrous to set up as a principle the concentration of distinct income-groups in great community-blocks. Suppose, for example, the entire emergency need of New York City after World War II, 500,000 units, had been met in this way; then every fifth block in the city would be marked as a tight class ghetto. To be sure such concentration presently exists, whether in slum areas or in fashionable neighborhoods; but it is worse to fix it as an official policy.

Ideally, the community block is a powerful social force. Starting from being neighbors, meeting on the street, and sharing community domestic services (laundry, nursery school), the residents become conscious of their common interests. In Scandinavia they start further along, with cooperative stores and cooperative management. Where there is a sense of neighborhood, proposals are initiated for the local good; and this can come to the immensely desirable result of a political unit intermediary between the families and the faceless civic authority, a neighborhood perhaps the size of an election district. (This is what the PTA should be, and is not.) Such face-to-face agencies, exerting their influence for schools, zoning, play-streets, a sensible solution for problems of transit and traffic, would soon make an end of isolated plans for “housing.”

But if the consciousness of a housing plan remains in the civic authority alone, then the super-block may achieve minimal standards and keep out through traffic, but more importantly it will serve, as we saw in the Cité Jardin of Le Corbusier, as a means of imposing even more strongly the undesirable values of the megalopolis.

Chapter 3: Industrial Plans

These are plans for the efficiency of production, treating domestic amenity and personal values as useful for that end, either technically or socially. They are first proposed for underdeveloped regions, whereas green belt planning is aimed to remedy the conditions of overcapitalization. Most simply we can think of a new industry in a virgin territory—Venezuela, Alaska—where a community can be laid out centering in a technical plant, an oilfield, a mine, or a factory, with housing and civic services for those who man the works.