Paul J. Tompkins

Human Factors Considerations of Undergrounds in Insurgencies

Assessing Revolutionary and Insurgent Strategies

Assessing Revolutionary and Insurgent Strategies

Preface to the First Edition, 1966

Changes Since the Original Edition

Acknowledgments of Original Authors and Aris Contributors

Part I: Undergrounds as Organizations

Chapter 2. Underlying Causes of Violence

Marginalization or Persecution of Identity Groups

Table 2–1. Code Guidance for Three Discrimination Categories From the Mar Dataset

History of Conflict in the Country or Conflict in Nearby Countries

Exploitable Primary Commodity Resources

Part I. Undergrounds as Organizations

Chapter 3. Organizational Structure and Function

Aligning Structure With Strategy

Secrecy and Compartmentalization

Evolution and Growth of Organizations

Underground and Aboveground Connections

Table 3–1. Organizational Features Illustrated by Three Cases.

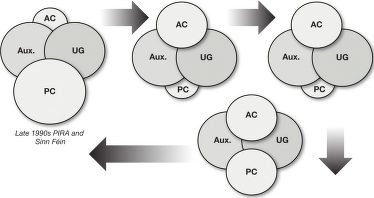

The Pira as a Regional Insurgency

Evolution and Growth of the Organization

Underground and Aboveground Connections

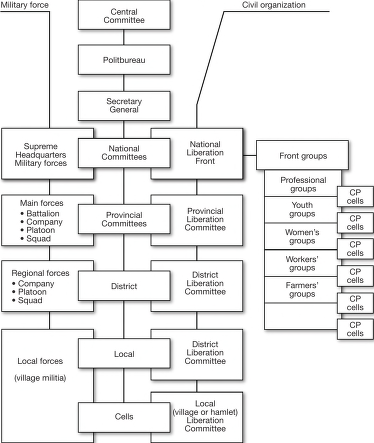

Communist Insurgencies as Organizations

International Command and Control

Chain of Command Between Committee Levels

The Role of Self-Criticism Sessions

Underground and Aboveground Connections

Infiltration of Mass Organizations and Use of “Front” Organizations

Methods of Controlling Mass Organizations

Aligning of Structure to Strategy

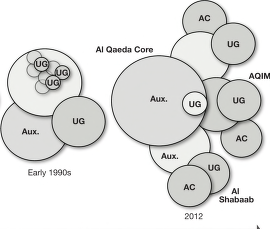

Al Qaeda as a Decentralized Network

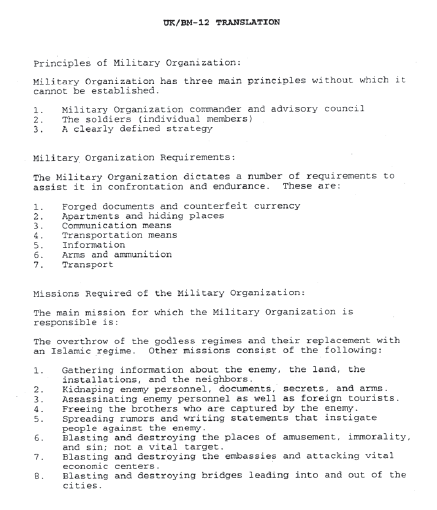

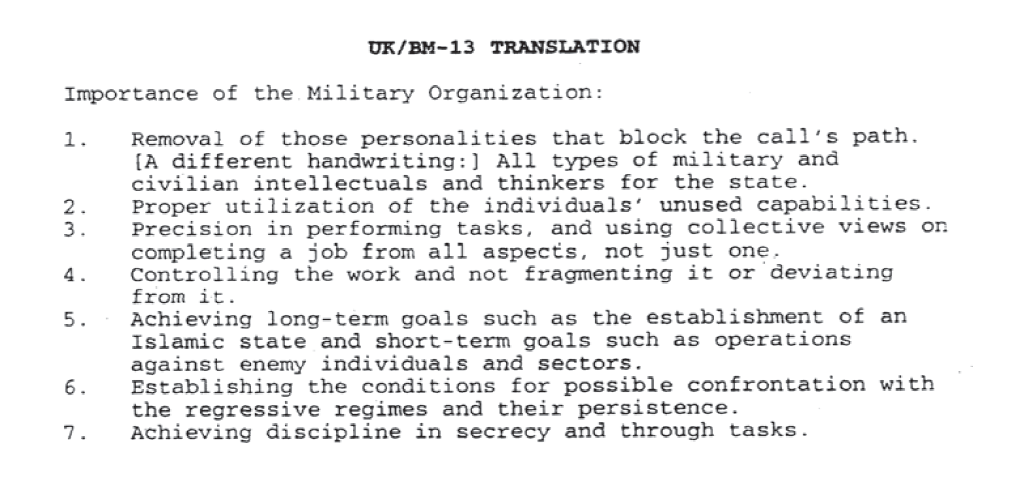

Secrecy and Compartmentalization

Evolution and Growth of the Organization

Aligning Structure to Strategy

Underground and Aboveground Connectivity

Transactional and Transformational Leadership

Charismatic Leadership in Undergrounds

A Case Study: Dr. Ayman Al-zawahiri

Chapter 5. Joining, Staying in, and Leaving the Underground

Recruitment in Rural Insurgencies: the Huks and the Viet Minh

PIRA Recruitment of Republican Sympathizers

Campus Recruitment by EIG: Filling a Void

Qutbism: Ideology of the Modern Global Salafist Jihad

Chapter 6. Group Dynamics and Radicalization

Social Psychology of Group Conflict

Social Identity Groups: Categorization and Salience

Out-Group Stereotypes and Discrimination

Mechanisms of Group Radicalization

Escalation of In-Group/Out-Group Conflicts

Radicalization Through Isolation

Radicalization Through Condensation or Splitting

Radicalization in Competition for the Same Base of Support

Rhetoric of Hate: Dehumanization and “Selective Moral Disengagement”

Radicalization Through Martyrdom

Chapter 7. Psychological Risk Factors

Introduction: is the Disease Model Applicable?

Axis I Disorders and “lone Wolf” Terrorists

Axis II: Developmental and Personality Disorders

Suicidality and Suicide Bombers

Personal Connection to a Grievance (Political or Otherwise)

Vicarious Experience of Grievance

Table 7–1. Radicalization Mechanisms and Their Relevance to the Zawahiri Case Study.

Part III. Underground Psychological Operations

Chapter 8. Insurgent Use of Media: Traditional, Broadcast, and Internet

Importance of Media to Insurgencies

Insurgent-Owned Broadcast Media

Recruitment and Radicalization

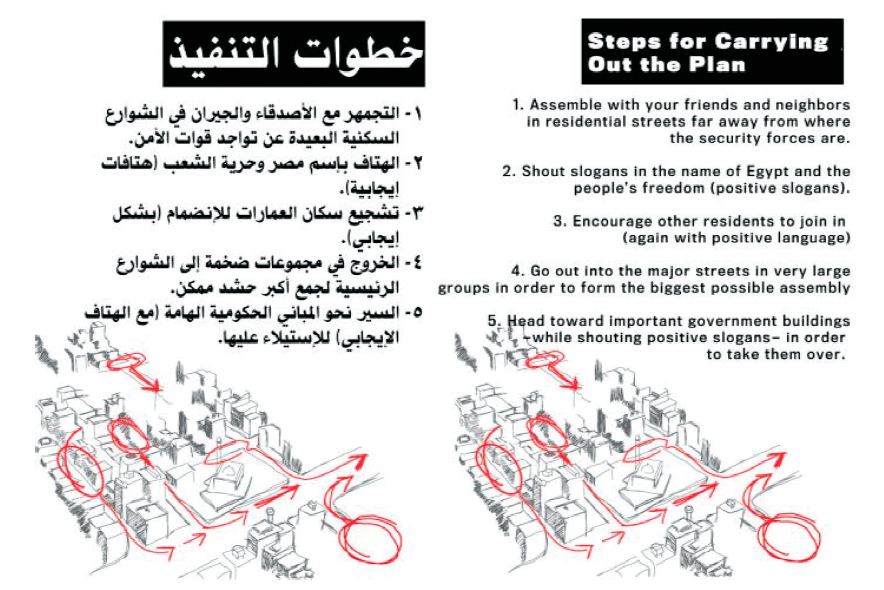

Steps for Carrying Out the Plan

Chapter 9. Psychology of Influence

Social Pressures and Social Networks

Influence as an Individual Process

Rumors as an Example of Message Transmittal

Promoting the Understanding and Retention of Messages

Presenting One Versus Both Sides of an Argument: Message Inoculation

Role of Narratives in Justifying Insurgent Movements

Table 9–1. Assessing Revolutionary and Insurgent Strategies (Aris) Dataset.

Table 9–2. Distribution of Narrative Themes Across Aris Categories.

Chapter 10. Nonviolent Resistance

The Methods of Nonviolent Protest and Persuasion

Disruption of Socioeconomic and Political Status Quo

Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance

Psychological Effects of Terror

Front Matter

Publisher Details

Assessing Revolutionary and Insurgent Strategies

HUMAN FACTORS CONSIDERATIONS OF UNDERGROUNDS IN INSURGENCIES

SECOND EDITION

Paul J. Tompkins Jr., USASOC Project Lead Nathan Bos, Editor

United States Army Special Operations Command

and

The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory National Security Analysis Department

Publisher Details

This publication is a work of the United States Government in accordance with Title 17, United States Code, sections 101 and 105.

Published by:

The United States Army Special Operations Command

Fort Bragg, North Carolina

25 January 2013

Second Edition

First Edition published by Special Operations Research Office, American University, December 1965

Reproduction in whole or in part is permitted for any purpose of the United States government. Nonmateriel research on special warfare is performed in support of the requirements stated by the United States Army Special Operations Command, Department of the Army. This research is accomplished at The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory by the National Security Analysis Department, a nongovernmental agency operating under the supervision of the USASOC Special Programs Division, Department of the Army.

The analysis and the opinions expressed within this document are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the U.S. Army or The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.

Comments correcting errors of fact and opinion, filling or indicating gaps of information, and suggesting other changes that may be appropriate should be addressed to:

United States Army Special Operations Command

G-3X, Special Programs Division

2929 Desert Storm Drive

Fort Bragg, NC 28310

All ARIS products are available from USASOC at www.soc.mil under the ARIS link.

Assessing Revolutionary and Insurgent Strategies

The Assessing Revolutionary and Insurgent Strategies (ARIS) series consists of a set of case studies and research conducted for the US Army Special Operations Command by the National Security Analysis Department of The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.

The purpose of the ARIS series is to produce a collection of academically rigorous yet operationally relevant research materials to develop and illustrate a common understanding of insurgency and revolution. This research, intended to form a bedrock body of knowledge for members of the Special Forces, will allow users to distill vast amounts of material from a wide array of campaigns and extract relevant lessons, thereby enabling the development of future doctrine, professional education, and training.

From its inception, ARIS has been focused on exploring historical and current revolutions and insurgencies for the purpose of identifying emerging trends in operational designs and patterns. ARIS encompasses research and studies on the general characteristics of revolutionary movements and insurgencies and examines unique adaptations by specific organizations or groups to overcome various environmental and contextual challenges.

The ARIS series follows in the tradition of research conducted by the Special Operations Research Office (SORO) of American University in the 1950s and 1960s, by adding new research to that body of work and in several instances releasing updated editions of original SORO studies.

VOLUMES IN THE ARIS SERIES

Casebook on Insurgency and Revolutionary Warfare, Volume I: 1933–1962 (Rev. Ed.)

Casebook on Insurgency and Revolutionary Warfare, Volume II: 1962–2009 Undergrounds in Insurgent, Revolutionary, and Resistance Warfare (2ndEd.)

Human Factors Considerations of Undergrounds in Insurgencies (2nd Ed.)

Irregular Warfare Annotated Bibliography

FUTURE STUDIES

The Legal Status of Participants in Irregular Warfare Case Studies in Insurgency and. Revolutionary Warfare—Colombia (1964–2009)

Case Studies in Insurgency and Revolutionary Warfare—Sri Lanka (1976–2009)

SORO STUDIES

Case Study in Guerrilla War: Greece During World War II (pub. 1961)

Case Studies in Insurgency and Revolutionary Warfare: Algeria 1954–1962 (pub. 1963) Case Studies in Insurgency and. Revolutionary Warfare: Cuba 1953–1959 (pub. 1963)

Case Study in Insurgency and Revolutionary Warfare: Guatemala 1944–1954 (pub. 1964) Case Studies in Insurgency and. Revolutionary Warfare: Vietnam 1941–1954 (pub. 1964)

Letters of Introduction

The foreword to Special Warfare’s 1966 Human Factors Considerations of Undergrounds in Insurgencies notes, “in the desire to understand the broad characteristics and societal impact of revolutionary movements we often neglect the study of the human element involved.” “To understand the individual, his reasons, his behavior, and the pressures that society places upon him is at the heart of the problem of social change.” The earlier study and this updated edition represent part of our intellectual investment in understanding the human domain. Understanding the human domain remains critical for future Special Warfare operations.

Since the inception of the United States Army Special Forces, understanding indigenous individuals and the human domain in which they exist has been a persistent Army Special Operations Forces cornerstone. Relationships with indigenous individuals enable Special Warfare. Understanding why individuals choose to join an underground movement, why law-abiding citizens are tempted to lead a dangerous underground life, why individuals stay in underground organizations, and what behaviors individuals use to survive are key questions that will reveal insights into the individuals that may be our partners. Special Warfare’s leverage of and reliance on indigenous forces offers a unique capability. This Special Warfare capability offers our nation’s leaders necessary and different strategic options. Our Special Warfare mission necessitates our continued educational and intellectual commitment to studying human factors. Our endeavor must include institutional and individual commitments. This updated volume offers a beginning, and the text will be integrated into our schoolhouse curriculums. The schoolhouse introduction represents only the starting point for each Army Special Operations Forces member’s continued learning. Our nation requires a Special Warfare capability. The Special Warfare capability requires intellectual investment and continuous evolution to understand the people that the human domain represents. I encourage each member to read, analyze, debate, and challenge this work as we endeavor to remain the premier Special Warfare capability in the world.

LTG Charles T. Cleveland

Commanding General, U.S. Army Special Operations Command

The first time I saw the original version of this book was when it was presented to me in 1979 at the Special Forces Qualification Course, and I have reread it multiple times in the years since. The original edition of this book, and the remainder of the series produced by Special Operations Research Office (SORO),[1] constitute some of the foundational references necessary to a full understanding of Special Forces operations and doctrine. Thirty-three years later, I still use it routinely to teach and mentor new and experienced Special Forces personnel.

This book is intended as an update to the original text. Basic human nature does not change, and much has remained the same throughout the history of human political conflict. The new edition therefore includes the enduring principles and methods from the original. The sections of the book discussing techniques, causes, and methods, however, required updating to reflect the many changes in the world and experiences of Special Forces in the last fifty years.

While the need to resist perceived oppression has not changed, the ways in which oppressed societies express this need through culture have changed significantly. Whereas insurgencies prior to the publication of the first edition of this book in 1963 were predominantly Communist-inspired, modern rebellions have been inspired by a greater number of factors. This increase in the causes of insurgency began with the fall of the Soviet Union, and accelerated with the attacks of September 11, 2001, on the United States.

In addition, technology has changed the world significantly over the last fifty years. Modern communications, the Internet, global positioning and navigation systems, and transportation have all introduced different dynamic pressures on how insurgencies develop and operate. As a result of the cultural and technological shifts of the past fifty years, we decided that the original series by SORO needed revision and updating. Like the original series, this update is written by sociologists, this time from The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.

Plenty of histories and military analyses have been written on the different revolutions that have taken place over the past fifty years, but this series—including the new, second volume of the Casebook—hopefully provides a useful perspective. Since rebellion is a sociopolitical issue that takes place in the human domain, a view through the nonmilitary lens broadens the aperture of learning for Special Forces soldiers.

Acknowledgements

This project would not have been possible without the support of COL Dave Maxwell, who was the USASOC G3 (my boss) and fought to get the project approved. Also I must thank Michael McCran, a longtime friend who encouraged me to continue to seek the approval of this project.

Paul J. Tompkins Jr. USASOC Project Lead

Preface to the First Edition, 1966

Human Factors Considerations of Undergrounds in Insurgencies is the second product of Special Operations Research Office (SORO) research on undergrounds. The first, Undergrounds in Insurgent, Revolutionary, and Resistance Warfare, was a generalized description of the organization and operations of underground movements, with seven illustrative cases. The present study provides more detailed information, with special attention to human motivation and behavior, the relation between the organizational structure of the underground and the total insurgent movement, and Communist-dominated insurgencies.

Because an understanding of the general nature of undergrounds is necessary to more detailed considerations, some of the information from the earlier study of undergrounds has been included in this report. Wherever possible, material from insurgency situations since World War II has been used. Occasionally, however, it was necessary to use information from studies of World War II underground movements in order to fill gaps about certain operations.

In the methodological approach it was assumed that confidence could be placed in the conclusions if data on underground operations and missions and similar data could be found in other insurgencies. An attempt was made to base conclusions on empirical information and actual accounts rather than theoretical discussions, and upon data from two or more insurgencies. An effort was made to find internal consistencies within the information sources. For example, if units were organized and trained to use coercive techniques for recruiting, and defectors described having been recruited in this manner, the conclusion that people were coerced into the movement can be made. Because of this approach there is a good deal of redundancy within and among the various chapters.

While the main emphasis in this report has been on underground organization, many characteristics can be understood only in relation to overt portions of the subversive organization. Therefore, discussions of guerrilla forces, the visible outgrowth of undergrounds, and of Communist structures, which often inspire, instigate, and support subversive undergrounds, have been included. The report is designed to provide the military user with a text to complement existing training materials and manuals in counterinsurgency and unconventional warfare, and to provide helpful background information for the formulation of counterinsurgency policy and doctrine. As such, it should be particularly useful for training courses related to the counterinsurgency mission.

The authors wish to express thanks to a number of persons whose expertise and advice assisted substantially in the preparation of this report. Mr. Slavko N. Bjelajac, Director of Special Operations for the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations, Department of the Army, on the basis of his personal experiences and special interest in the study of underground movements, contributed guidelines and concepts to the study.

Four men reviewed the entire report: Dr. George K. Tanham, Special Assistant to the President of the Rand Corporation of Santa Monica, California, made many helpful suggestions based upon his firsthand experiences and study of Communist insurgency; Dr. Jan Karski, Professor of Government at Georgetown University, Washington, D.C., whose personal experience as a former underground worker is combined with a talent for thorough, constructive criticism, also helped the final manuscript; Dr. Ralph Sanders of the staff of the Industrial College of the Armed Forces, Washington, D.C., offered a careful and useful critique of the manuscript and helpful suggestions; Lt. Col. Arthur J. Halligan of the U.S. Army Intelligence School, Fort Holabird, Maryland, provided valuable suggestions based upon his experience in Vietnam.

Within SORO, Dr. Alexander Askenasy, Brig. Gen. Frederick Munson (Ret.), Mr. Phillip Thienel, Mr. Adrian Jones, Dr. Michael Conley, Mrs. Virginia Hunter, and Mrs. Edith Spain contributed to the end product.

Andreiu Molnar

Preface to the Second Edition

This book, Human Factors Considerations of Undergrounds in Insurgencies, is the second edition to the 1966} book of the same name. The first edition of this book was produced by the Special Operations Research Office (SORO) at American University in Washington, DC. SORO was established by the U.S. Army in 1956. During the 1950s through the mid-1960s, SORO social scientists and military personnel researched relevant political, cultural, social, and behavioral issues occurring within the emerging nations within Asia, Africa, and Latin America.{1} The researchers conducted analyses, sometimes for the first time, on the effects of propaganda and psychological operations and the roles of the military in developing countries, and provided large bibliographies of unclassified materials related to counterinsurgency and unconventional warfare. The Army had a particular interest in understanding the processes of violent social change in order to be able to cope directly or indirectly through assistance and advice with revolutionary actions. In 1962, SORO published the Casebook on Insurgency and Revolutionary Warfare; in 1963, it published Undergrounds in Insurgent, Revolutionary, and Resistance Warfare-, and in 1966, it published Human Factors Considerations of Undergrounds in Insurgencies—each of these publications remained in the Special Operations training curricula for subsequent generations. The work of SORO, whose scholarship grew more ambitious and controversial, and later the Center for Research in Social Systems (CRESS), has endured. Some of the reports under Project PROSYMS (Propaganda Symbols) have served as examples of incorporating rigorous social science research methods into psychological operations, and the CRESS report on the subversive manipulation of crowds is still widely used as a training resource. Relevant components of many of SORO and CRESS papers are referenced in this edition.

The American experience in Afghanistan, Iraq, the Philippines, the Horn of Africa, and other locales in the twenty-first century reaffirmed the need for cooperation between the academic and operational communities. In 2009, the U.S. Army Special Operations Command (USASOC) G-3X sought to recreate some of the capability SORO had provided. They turned to, among other institutions, The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHU/APL). Under a project entitled Assessing Revolutionary and Insurgent Strategies (ARIS), researchers at JHU/APL have been engaged in understanding how social movements such as insurgencies and revolutionary groups are created; how they grow, spread, and sustain themselves; and how they succeed or fail.{2} The first product of that effort is the forthcoming Casebook on Insurgency and Revolutionary Warfare, Volume II: 1962–2009. Similar to the first volume, the second volume is intended to provide a foundational understanding of insurgent warfare by presenting cases using a common analytical framework and format. The second and third major products under ARIS are the second editions of Undergrounds in Insurgent, Revolutionary, and Resistance Warfare and Human Factors Considerations of Undergrounds in Insurgencies.

Most of the text in this edition is new. Some large sections of the first edition are retained verbatim, mostly in Chapter 3’s study of Communist organizations and sections of Chapter 5 on recruitment and retention, but also in smaller sections of the other chapters as well. We preserved much of the overall structure, although not the specific chapters, and strove to answer many of the same underlying questions. Material from the first edition is used without citation. Material from other SORO studies is referenced like any other source.

Intended as a complement to the second edition of Undergrounds in Insurgent, Revolutionary, and Resistance Warfare, this book delves deeper into theory and further into background materials and focuses less on operational details. We provide numerous chapter cross-references to the second edition of Undergrounds. We also drew heavily on the new, second volume of the Casebook, these cases are cited in the normal way. We also provide a table of contents at the beginning of every chapter to make the book more useful as a reference.

The first edition of Human Factors was an important synthesis of a poorly understood topic and has proved to have some remarkable staying power, with much still relevant even in the edition’s fifth decade. An update to the first edition is needed, however, simply because the world has changed since the 1960s.

Changes Since the Original Edition

The 1966} Human Factors edition focused on the contemporary threat of Maoist insurgencies, particularly in Southeast Asia, and also drew extensively on World War II resistance movements in Europe. Much of this information is still relevant and has been retained and integrated. In the post-Cold War world, the most important insurgencies tend to be ethnic and religious. Long-simmering conflicts, sometimes with roots in colonial policies, have become prominent; examples include the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in Sri Lanka, Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (Basque Homeland and Lreedom or ETA) in Spain, the Hutu-Tutsi genocides, the Ushtia (dirimtare e Kosoves (Kosovo Liberation Army, or KLA), and the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA). Battle lines in these conflicts are often drawn along ethnic lines, even when land or politics are the immediate issues in contention. The other important new category is extremist religious movements, most prominently Islamic groups, including regional insurgent movements like Hizbollah and Harakat al-Muqawamah al-’Islamiyyah (Islamic Resistance Movement, or HAMAS) and global movements like Al Qaeda. These present a different profile of ideology, organizational forms, and psychology than either Cold War Maoists or post-colonial ethnic insurgencies (although the Palestinian cause could be considered a post-colonial issue).

Globalization has also changed underground operations in numerous ways. Insurgencies, enabled by low-cost transportation, Internetbased communications, and other information technologies, can more easily recruit, communicate, and operate across borders. It is correspondingly much more difficult to contain an insurgency in a region. Global media has led to development of new tactics, in particular new types of terrorism, designed to capture worldwide attention.

Compared with what was available in the 1960s, there are orders of magnitude more academic research available relevant to this study’s topics. We were able to draw on more recent work in psychology, political science, economics, sociology, organizational studies, and communications studies. Readers of this edition will, over the course of eleven chapters, get a wide exposure to basic concepts from a number of disciplines. This breadth also presented a challenge in trying to evaluate and synthesize many competing explanatory frameworks while keeping focus on what is relevant (sometimes directly, sometimes as background) to the study. The authors strove to accurately synthesize relevant background material but avoided wading into inconsequential details or academic debates; readers can make their own judgment as to how effectively the latter part was accomplished.

Acknowledgments of Original Authors and Aris Contributors

Each chapter in this edition does have author credits at the beginning; chapters that borrow significant sections of the original edition list “SORO authors” as authors. (At the beginning of this effort, the co-authors for this edition, along with project lead Chuck Crossett, had a brief social meeting with Andrew Molnar, first author of the original study, who is now retired and living a short drive from our campus in Maryland. Dr. Molnar, for his part, was quite amenable to his work being used in an updated edition.)

The ARIS project is the result of the joint vision and initiative of Paul Tompkins Jr., chief USASOC, G-3X Special Programs Division, and our colleague Chuck Crossett of JHU/APL.

John Shissler, Senior Researcher, JHU/APL, served as quality reviewer for this edition and made many substantive contributions. This effort also benefitted from the knowledge and efforts of our JHU/ APL colleagues Jerome Conley, Angela Hughes, Robert Leonhard, Kelly Livieratos, and Summer Newton.

Nathan Bos, Ph.D., and Jason Spitaletta Laurel, Maryland, March 2012

List of Illustrations

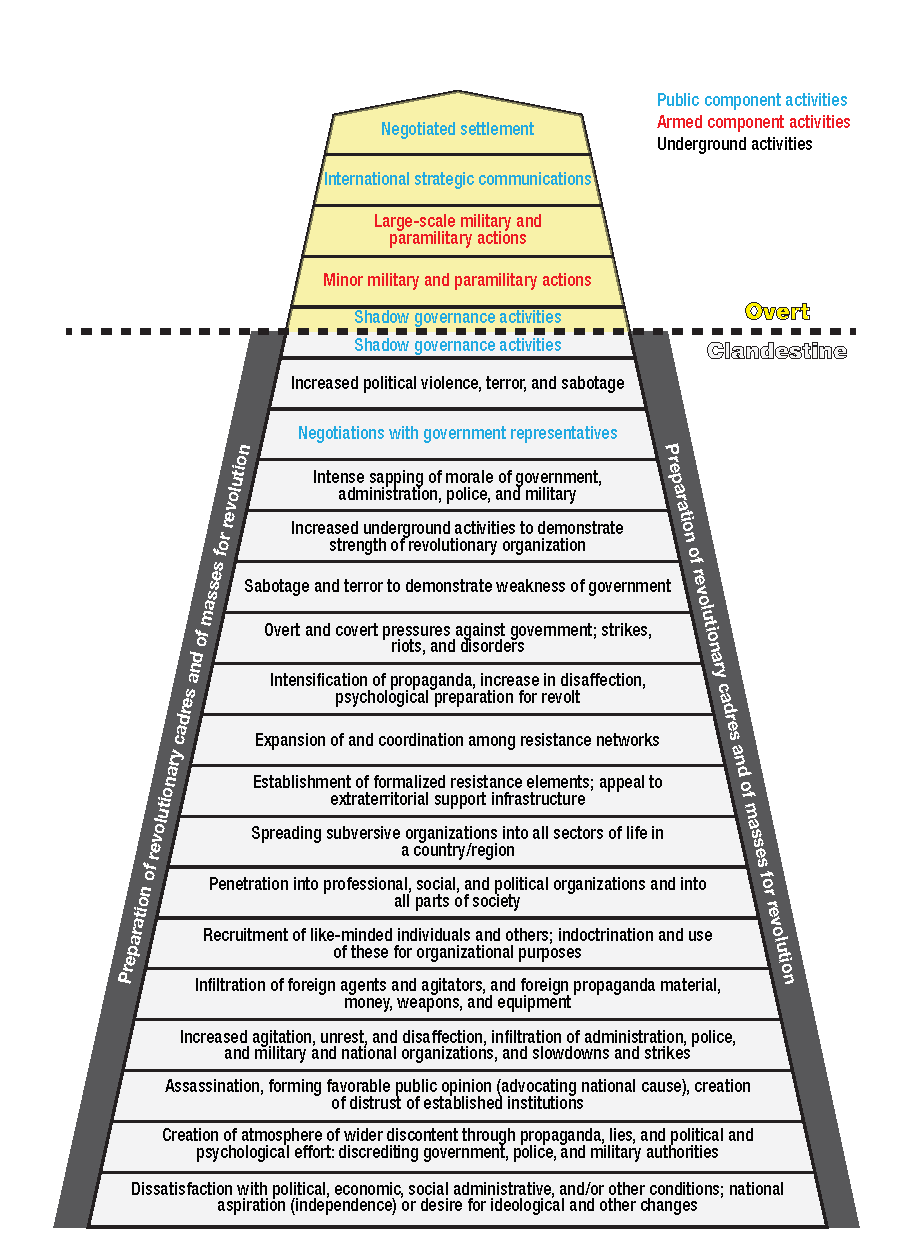

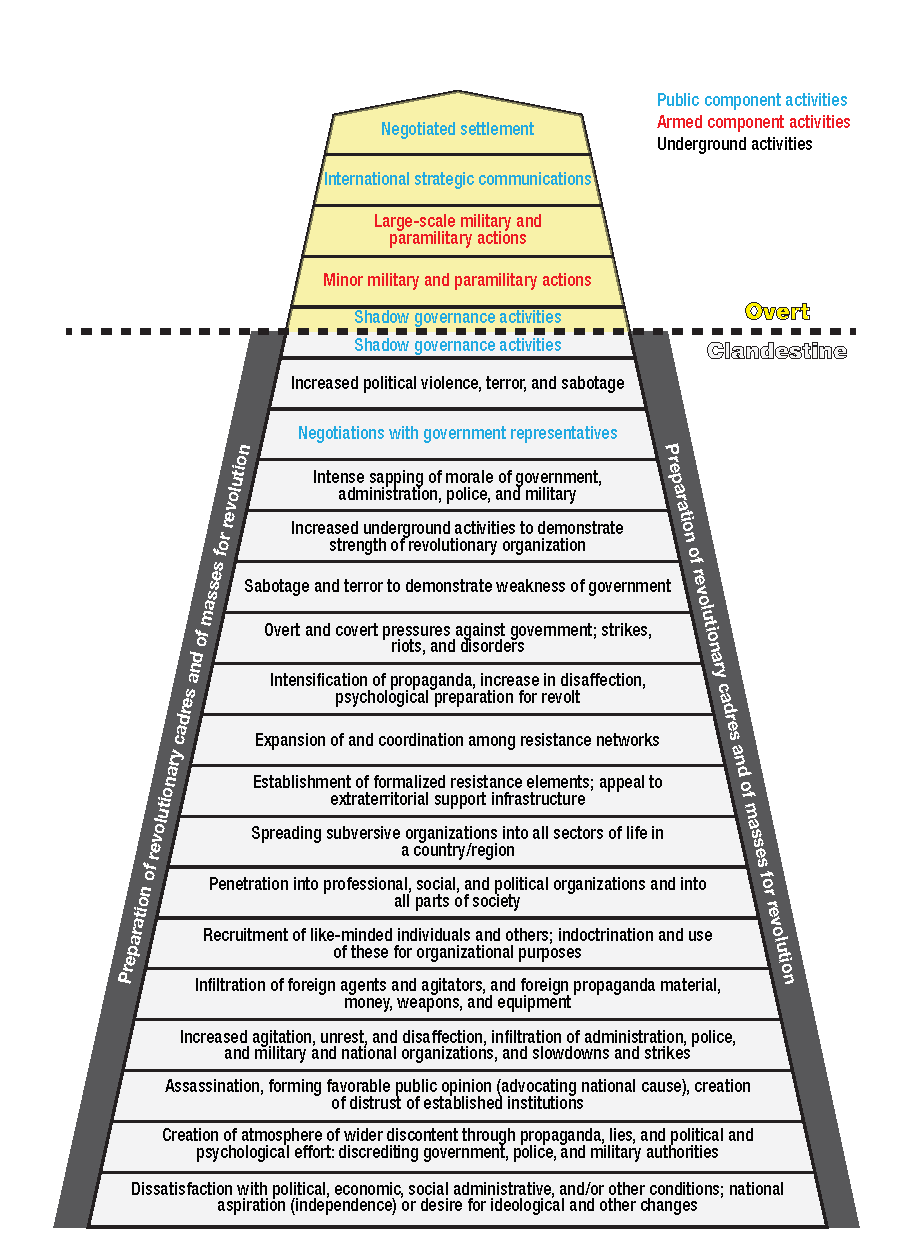

FIGURE 1–1. Covert and overt functions of an underground

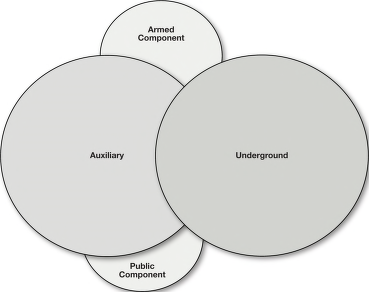

FIGURE 3–1. Components, phases, and functions of an insurgency.

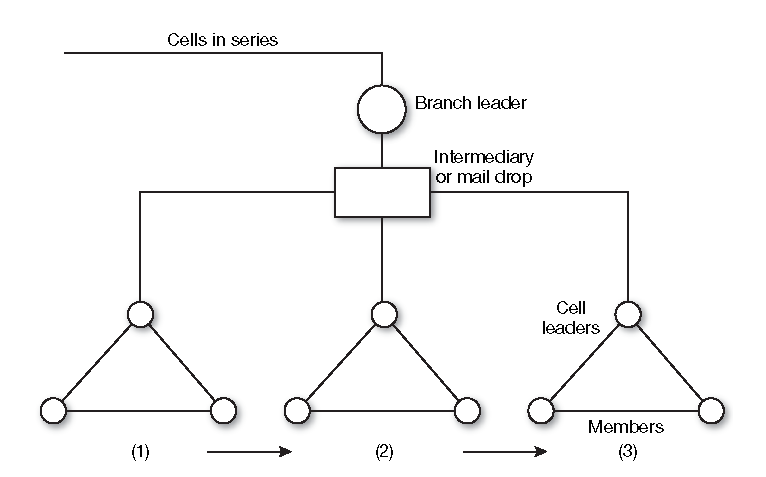

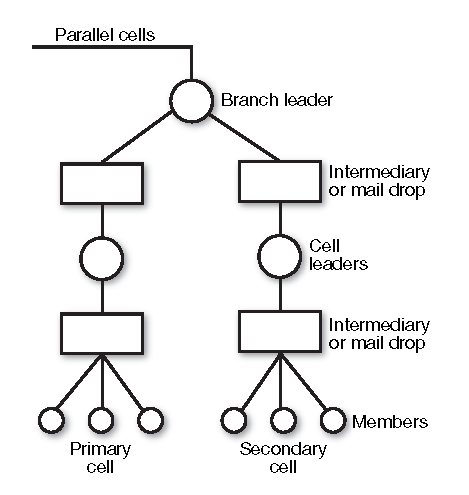

FIGURE 3–2. Cells in series

FIGURE 3–3. Parallel cells

FIGURE 3–4. Covert and overt functions of an underground

FIGURE 3–5. Cyclical evolution of the PIRA

FIGURE 3–6. Organizational divisions and hierarchy of a mature Maoist insurgency

FIGURE 3–7. Evolution of Al Qaeda as a decentralized network, 1989–2012

FIGURE 3–8. Excerpt from page 13 of the “Manchester Manual.”...

FIGURE 3–9. Excerpt from page 14 of the “Manchester Manual.” ...

FIGURE 8–1. Instructions for crowd assembly from Egyptian protestors’ pamphlet

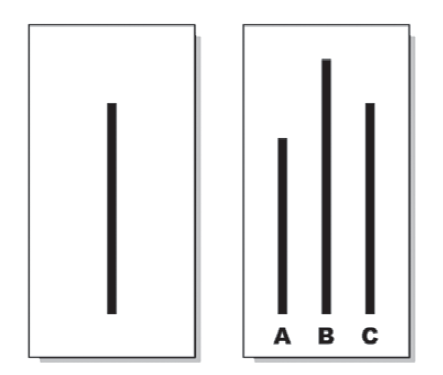

FIGURE 9–1. Which line segment matches the one on the left? ....

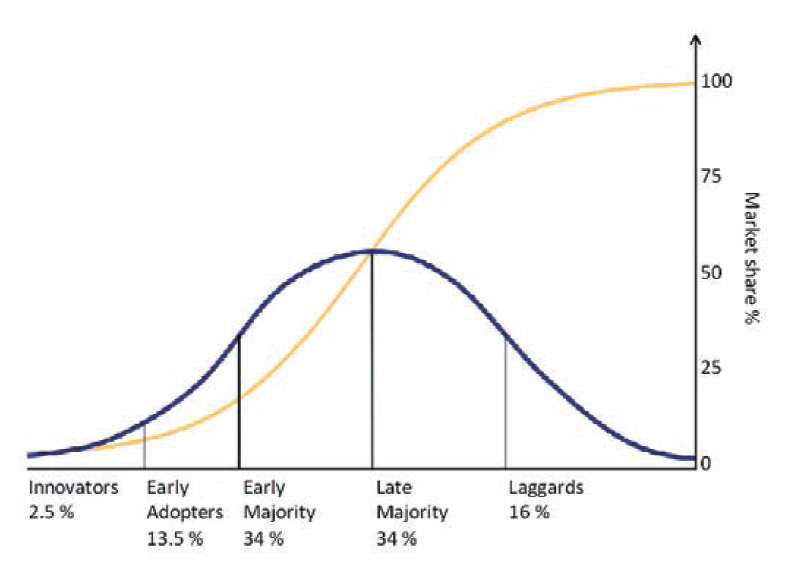

FIGURE 9–2. Everett Rogers’s diffusion of innovation model, role distribution and market saturation

FIGURE 9–3. X-ray image of a chest showing a growth on the left side of the lung

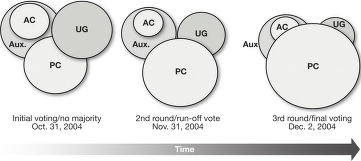

FIGURE 10–1. Time series component model for the Orange Revolution

List of Tables

TABLE 2–1. Code guidance for three discrimination categories from the MAR dataset

TABLE 3–1. Organizational features illustrated by three cases

TABLE 7–1. Radicalization mechanisms and their relevance to the Zawahiri case study

TABLE 9–1. Assessing Revolutionary and Insurgent Strategies (ARIS) dataset

TABLE 9–2. Distribution of narrative themes across ARIS categories..

TABLE 10–1. Methods of nonviolent action

Chapter 1. Introduction

Chapter Contents

-

Underlying Causes

-

Part I: Undergrounds as Organizations

-

Part II: Motivation

-

Part III: Underground Psychological Operations

Nathan Bos and Jason Spitaletta

Warfare is an inherently human activity, fraught with the idiosyncrasies of human behavior experiencing existential stress. The complexity of human factors in warfare is perhaps best articulated by Clausewitz’s wondrous trinity, which describes war as “more than a true chameleon that slightly adapts its characteristics to the given case. As a total phenomenon its dominant tendencies always make war a paradoxical trinity—composed of primordial violence, hatred, and enmity, which are to be regarded as a blind natural force; of the play of chance and probability within which the creative spirit is free to roam; and of its element of subordination, as an instrument of policy, which makes it subject to pure reason.”{3}

An understanding of human factors is arguably more critical in irregular warfare than in conventional warfare and especially critical in complex civil conflicts that extend over time into a protracted war for “hearts and minds.” The Director of Central Intelligence Directive (DCID) 7/3} defines human factors as, “The psychological, cultural, behavioral, and other human attributes that influence decision-making, the flow of information, and the interpretation of information by individuals and groups at any level in any state or organization.” This definition is appropriate but somewhat cold. It fails to communicate the simultaneously fascinating and frustrating part of human factors in insurgencies, which is that such conflicts push common behavioral and social dynamics to their extremes. Organizational design, leadership, social influence, mental health, and the other topics discussed in this book are standard topics in the behavioral sciences. But these choices take on existential significance when they involve an insurgent organization weighing trade-offs between reliability and flexibility, a strategic choice whether to embrace violence or nonviolence, or an individual’s judgments about whether to trust an ideology, a social contact, or a charismatic leader. Understanding individual choices regarding underground movements requires knowledge of mental health, the dynamics of hate, and the power of social influence in extremis. Understanding a population’s support or rejection of such movements requires understanding of a broad set of political, economic, and social factors, and often requires an understanding of how individuals respond to oppression, violence, or terrorism.

This book is divided into two background chapters and three main sections. This structure follows the basic organization and flow of the first edition. Previews of the sections and chapters are provided below.

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: Underlying Causes of Violence

Part I: Undergrounds as Organizations

Chapter 3: Organizational Structure and Function Chapter 4: Leadership

Part II: Motivation

Chapter 5: Joining, Staying In, and Leaving the Underground Chapter 6: Group Dynamics and Radicalization Chapter 7: Psychological Risk Factors

Part III: Underground Psychological Operations

Chapter 8: Insurgent Use of Media: Traditional, Broadcast, and Internet

Chapter 9: Psychology of Influence Chapter 10: Nonviolent Resistance Chapter 11: Terrorism

Underlying Causes

Why do violent insurgencies appear in some countries and persist for decades, while countries that appear culturally, politically, or economically similar experience no such events? Understanding where and why civil violence is likely to occur is of great interest to policy makers, of course, and is also relevant to soldiers on the ground inasmuch as it helps explain the causes and internal dynamics of a conflict. Chapter 2 delves into the political and social factors that seem to predict civil violence.

Poverty contributes to instability, but not in as direct a way as might be supposed. People’s perception of relative deprivation, which is failure to meet economic expectations or keep up with visible peer groups, tends to be more important than the absolute level of deprivation. Poor governance combined with poverty is an even more dangerous combination. The legitimacy of the government in the eyes of the populace can insulate governments in poor countries or endanger them even in wealthier ones; legitimate governments provide security, justice (especially related to corruption), and economic development and have ideological legitimacy conveyed to them by other powerful institutions.

Marginalization or persecution of ethnic or religious groups within the country is one of the strongest factors predicting violent resistance. The importance of social identity-based conflicts in understanding insurgencies is a common theme in this book. Countries in conflict-filled “neighborhoods,” or with a history of domestic conflict, are much more likely to see future conflict because of the ready availability of weapons and trained personnel, and because the population may be desensitized to violence. Countries experiencing a demographic “youth bulge” seem to be particularly vulnerable to instability; such population bulges often lead to feelings of relative deprivation if young people are unemployed at high levels.

Insurgencies need funding, and those that do not have external sponsors must find funding domestically; the presence of an exploitable commodity resource that can be smuggled, stolen, or extorted, such as diamonds, drugs, or oil, seems to increase the likelihood of an ongoing insurgency. The terrain itself may be a contributor, as dense forests or mountainous terrain provide cover for insurgents. Chapter 2 of this work reviews the evidence surrounding these factors and details the mechanisms by which these factors may lead to violent resistance.

Part I: Undergrounds as Organizations

Chapter 3: Organizational Structure and Function and Chapter 4: Leadership complement the similar chapters in the companion to this work, the second edition of Undergrounds in Insurgent, Revolutionary, and Resistance Warfare. In Chapter 3, we examine six organizational challenges faced by all insurgent groups: command and control, aligning of structure with strategy, secrecy and compartmentalization, evolution and growth of organizations, underground and aboveground connections, and criminal connections. To understand how these factors play out in a contrasting set of cases, we examine these aspects of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) in Ireland, of prototypical Communist organizations, and of Al Qaeda. In terms of command structure, the PIRA’s military-type of command structure is an interesting contrast to Al Qaeda’s “franchise” model, which is different again from the Communist practice in which nonmilitary decision-making bodies, at least in theory, maintain control over armed components. Navigating the aboveground and underground connections presents challenges for every insurgent group, and the PIRA’s rejection, then gradual embrace of, political engagement (via Sinn Fein) highlights these issues. The international Communist movement, although well past its peak of influence, is still a fascinating organizational study in its complex, ingenious (in concept) interlocking coordination of infiltrated civil organizations, Communist front organizations, national and international party leadership, and military components.

Public component activities

Armed component activities

Underground activities

Negotiated settlement

International strategic communciations

Large-scale military and paramilitary actions

Minor military and paramilitary actions

Shadow governance activities

----------- Overt / Clandestine

Shadow governance activities

Increased political violence, terror, and sabotage

Negotiations with government representatives

Intense sapping of morale of government, administration, police, and military

Increased underground activities to demonstrate strength of revolutionary organization

Sabotage and terror to demonstrate weakness of government

Overt and covert pressures against government; strikes, riots, and disorders

Intensification of propaganda, increase in disaffection, psychological preparation for revolt

Expansion of and coordination among resistance networks

Establishment of formalized resistance elements; appeal to extraterritorial support infrastructure

Spreading subversive organizations into all sectors of life in a country/region

Penetration into professional, social, and political organizations and into all parts of society

Recruitment of like-minded individuals and others; indoctrination and use of these for organizational purposes

Infiltration of foreign agents and agitators, and foreign propaganda material, money, weapons, and equipment

Increased agitation, unrest, and disaffection, infiltration of administration, police, and military and national organizations, and slowdowns and strikes

Assassination, forming favorable public opinion (advocating national cause), creation of distrust of established institutions

Creation of atmosphere of wider discontent through propaganda, lies, and political and psychological effort: discrediting government, police, and military authorities

Dissatisfaction with political, economic, social administrative, and/or other conditions; national aspiration (independence) or desire for ideological and other changes

Figure Ends

Figure 1–1, also shown in Chapter 3, shows the range of organizational functions performed by an underground. A figure very similar to this was included in the first edition and has been reproduced somewhat widely since; this update to the figure includes more aboveground functions of insurgent public components.

In addition to organizational structure, the personalities of key leaders can also have a strong influence on the operations of insurgent organizations, particularly during their early stages. What kind of personality is required to recruit and lead friends, relatives, and strangers in such a dangerous undertaking? Upstart insurgencies are often headed by leaders who are charismatic, a style with critical strengths and marked limitations, particularly when groups become larger. Several other strong personality traits, some bordering on psychopathologies, may be associated with insurgent leadership and may affect, hinder, or sometimes help a would-be underground leader. Chapter 4’s study of leadership includes an example profile of former Egyptian Islamic Jihad (EIJ) and current Al Qaeda leader Dr. Ayman Al-Zawahiri; the profile was drawn from an unclassified integrated personality profile{4} using the Integrated Political Personality Profile method that was created, published, and taught by Dr. Jerrold M. Post.

Part II: Motivation

The middle section of this book addresses the psychological and social variables important to understanding insurgent membership. Chapter 5 reviews what is known about joining, staying in, and leaving underground organizations, particularly foot soldiers in armed struggles. Social connections are always a key factor in recruitment. Ideology seems to play a more important role in early recruitment of true believers and a lesser role in mass recruitments during later-phase armed struggles. In these later phases, some groups turn to coercion, although this is usually paired with some subtlety with other incentives or manipulations. In Chapter 5, the recruitment strategies of rural insurgents (mostly Viet Minh and Phillipino Hukbalahap) are compared with the very different recruitment strategies used by the PIRA during “The Troubles” in Ireland and the recruitment of lonely and vulnerable college students by Egypt’s EIJ/Egyptian Islamic Group (EIG).

Ideology is a necessary although not sufficient element that affects both recruitment and retention. Ideology provides intellectual common ground for a movement, reduces uncertainty, justifies violent actions, and motivates members to persist through difficulty. One modern example of a well-developed ideology that has grounded and inspired radical and insurgent groups is Qutbism. Based on the writings of Sayyid Qutb, this ideology condemned current Arab leadership and called Muslims to a different kind of engagement with the outside world. Its influential role in shaping first modern Egyptian and ultimately global Salafist jihad movements is discussed in some detail.

Research on retention in underground movements is sparse, but there seem to be good parallels to soldiers in conventional military units in losing efforts, who often remain loyal to military units because of their social commitments and quality of leadership. There is also emerging research on why people leave insurgent groups, including a number of interesting (but largely unproven) tactics for “deradicalization” that are reviewed in Chapter 5.

Individual behavior can rarely be understood without understanding the social influences that surround that person, and the focus of Chapter 6 is on group dynamics. Academic research on in-group/outgroup conflicts started with bewildered researchers trying to explain the horrors of the Holocaust and other atrocities of World War II. These classic works remain relevant to today’s ethnic and religious conflicts, such as the escalation of tensions between Sinhalese and Tamils in Sri Lanka that fed the Tamil Tiger insurgency.

A recent paper on mechanisms of radicalization{5} provides a framework for discussing how group dynamics and outside pressures can lead groups to “radicalize,” or cross the line from nonviolent to violent actions. Some of these mechanisms are fairly easy to understand, such as radicalization under threat, but others are less intuitive, such as radicalization of groups in competition for the same base of support. The steps by which hate groups form and desensitize members to increasingly violent actions are also described.

Chapter 7 delves deeper into the individual psychological factors that may affect underground involvement. The mental stability of insurgents, terrorists, and suicide attackers is examined, and although the profile of the “psychopathic terrorist” is mostly a myth, there are some disorders that are helpful in understanding violence, suicidality, and related phenomena. A number of other more circumstantial influences on a person’s psychological state can affect the decision to become involved in a violent movement, including emotional vulnerability, experience of grievances such as abuse by government or military forces, vicarious experiences of grievances such as through Internet-based recruiting materials, and the perception that one’s religious or ethnic group has experienced humiliation at the hands of an opponent.

PART III: UNDERGROUND PSYCHOLOGICAL OPERATIONS

Insurgent groups never succeed as purely military operations; they must also effectively engage in battles of persuasion and influence. While the term “psychological operations” is no longer used by the U.S. military (in favor of Military Information Support Operations or MISO), the phrase is an appropriate label for the functions that underground groups can and do perform. The information domain’s impact on the radicalization process in modern insurgency cannot be overstated. The seemingly ubiquitous availability of information, including ideological narratives and success stories and even the presence of tactics, techniques, and procedures, can have a profound influence on cognitive processes.

Chapter 8 describes the use of media to reach a variety of audiences, to seek support from internal and external sympathizers, and to intimidate or demoralize internal opposition and the enemy. The basic functions of communication remain the same whether the medium is handbills or websites. But two recent historical technological developments did seem to be game changers for insurgent groups and those that oppose them. The first was the rise of global broadcast media, particularly satellite-linked television, which encouraged spectacular terrorist attacks such as the Munich Olympic kidnappings. The second technological breakthrough is still developing—use of the Internet. The Internet has lowered the cost and extended the reach for every important insurgent communications activity, including publicity, recruitment, training, fundraising, and command and control.

Insurgent groups, and those who oppose them, must also understand the basic principles of influence and its use in recruitment, persuasion, negotiation, and coercion. Chapter 9 is a more academic review of research in the area of influence, with relevant examples in the military domain. When influence is exercised one-on-one or oneto-many, charisma and nonverbal communication are critical factors. As influence extends throughout a population, understanding social networks and the roles of key individuals in a network becomes paramount; Everett Rogers’s model of how innovations diffuse in a population via “change agents,” “innovators,” and “opinion leaders” is relevant for political movements as well. The content of messages themselves also matters; careful use of evidence, “inoculation” messages, personal relevance, and other factors are what make certain messages resonate while others are ignored. It has also long been understood that the combination of words and actions can be more powerful than either by itself. The psychological mechanism of “cognitive dissonance” underlies some models for how this can be accomplished. Chapter 9 also includes a study of narratives as influence mechanisms, matching types of narrative arguments with different types of resistance movements.

Mastery of nonviolent tactics, as detailed in Chapter 10, is also critical for undergrounds facing stronger opponents. Some movements rely on nonviolent tactics exclusively; some integrate them with military actions (although this does tend to detract from the legitimacy of the nonviolent aspects). Many have developed ways to subversively manipulate nonviolent actions such as street protests to provoke violent confrontations, justify retaliatory attacks, or divert attention from other actions. Nonviolent actions can be classified into three broad categories: attention-getting devices such as street protests and street performance art; noncooperation techniques such as boycotts and work slowdowns; and civil disobedience campaigns such as civil rights sit-ins and Gandhi’s salt protests. Cyber activism and so-called Hacktivism are two newer developments in this area and are described in Chapter 10.

Terrorism, described in Chapter 11, has proven to be one of the more effective forms of psychological warfare. Chapter 11 discusses not only the individual and social psychological effects of terrorism but also the planning and justification processes behind the decision to use this tactic. The resultant anxiety and dysphoria associated with acts of terror create not only an increased fear but also awareness of death. This leads individuals to affiliate with those of similar worldviews and to be more willing to sacrifice their civil liberties to charismatic (and authoritarian) leaders. The chapter goes on to discuss some of the considerations and risks of terrorism as an insurgent tactic as well as some generalized patterns of behavior under the threat of terrorism.

Chapter 2. Underlying Causes of Violence

Chapter Contents

-

Economic Deprivation

-

Poor Governance

-

Lack of Government Legitimacy

-

Marginalization or Persecution of Identity Groups

-

History of Conflict in the Country or Conflict in Nearby Countries..

-

Demographic Youth Bulge

-

Exploitable Primary Commodity Resources

-

Type of Terrain

-

Summary

Nathan Bos

Why do violent insurgencies appear in some countries and persist for decades, while countries that appear culturally, politically, or economically similar experience no such events? Many people would, of course, like to be able to predict where violence is likely to occur before it happens, as well as understand what regimes are vulnerable and when. Political scientists have for decades been trying to understand what factors increase the probability of terrorism, insurgency, or other forms of political violence appearing in a country or region. This chapter will review the set of economic, political, geographic, and social variables that have the best evidence of being linked to the likelihood of violence.

In recent years, this question has been addressed with statistical analysis of large historical datasets. Without delving too far into the mathematics of these techniques, it is worth describing qualitatively how these techniques use past data to try to identify the most important factors influencing violence.

A good example of such a study was recently sponsored by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and conducted by a very accomplished group of political scientists.{6} This study sought to build a statistical model that could forecast instability events with as small a number of variables as possible. They produced a model that could “predict” 80 percent of instability events based on just four variables, which will be described later in this chapter.

Models to predict the future are necessarily based on past data, so this group, drawing on several well-known datasets, assembled data to construct a cross-national time-series dataset covering the period from 1955} through 2003} for all countries with a population of more than 500,000. Each record (row) in this dataset represented one country year (e.g., United States, 1965). The dataset included 7,500 total country years.

Their definition of an instability event included three types of events: civil wars, adverse regime changes, and genocides/politicides. (Precise definitions of each of these are included in the paper.) They identified 141 instability events and then began analysis of what factors might have predicted these.

Modern studies almost always use some form of multivariate regression, which is a statistical technique that allows one to propose a set of predictor variables (e.g., infant mortality, unemployment, civil wars in neighboring countries, climate) and an outcome variable (instability event) and determine which of the variables are most strongly associated with violent events while controlling for the other variables. The ability to control for the influence of some variables and isolate the influence of others is the most important power of regression compared with other techniques.

Different combinations of variables are tried to see which ones produce the strongest model. Multivariate regression forces predictor variables to “compete” with each other as explanatory variables within a given model. So one could enter both “infant mortality” and “unemployment” into the same model and might find that when infant mortality was available as an explanatory variable, unemployment became unimportant. The model could also show the reverse or show that they were both important independent of each other. These models can also reveal more complex relationships between three or more predictor variables.

Researchers will often try out dozens of combinations of variables over the course of a study, adding and removing variables to understand how they interact. (Because of the mathematical assumptions of noncollinearity in regression, it is impermissible to include predictor variables that are strongly correlated with each other, so researchers cannot simply include every variable in every model.) In published papers they may present just one best model or may present a series of perhaps four or five best alternative models, allowing the reader to also use their own judgment.

One of the most difficult aspects of interpreting statistical studies of past events is separating correlations from causality. There may be a strong statistical relationship between infant mortality and civil war, but does this mean that people are more likely to revolt because of high infant mortality (and associated poverty and poor health care), does it simply mean that health care services tend to be disrupted during wartime, or is there another explanation? An important additional tool is the use of time-lagged analysis. If infant mortality is also lower in the two years before the onset of a civil war, this shows that disruption in health care due to war is not the only reason for the relationship. This does not completely answer the question of how infant mortality is involved in causing instability, of course, but it does eliminate some possible explanations.

In the CIA study mentioned earlier, the authors presented a fourfactor model which “predicted” 80 percent of instability events. The four factors were (1) infant mortality (perhaps acting as a proxy for development), (2) presence of armed conflict in four or more bordering states, (3) regime type, and (4) presence of state-led discrimination. These will each be discussed below as risk factors for civil violence. The risk factors identified in this chapter are supported by similar regression-based studies performed over several decades of research with a variety of datasets and theoretical assumptions.

This chapter will discuss eight risk factors for political violence. Six of these are human factors: economic deprivation, poor governance, lack of legitimacy, marginalization and persecution of identity groups, history of conflict in the country or conflict in nearby countries, and unfavorable demographics such as a “youth bulge.” We will also discuss two risk factors that are not human factors: presence of a primary commodity resource and terrain type.

Each of these factors has been identified in at least one large-scale study relating it to political instability, political violence, or civil war. It is important to note that there is not universal agreement on any of these factors. For each of these factors, one can find at least one study or model that does not find a statistical relationship between that factor and political violence. However, absence of evidence is not necessarily evidence of absence, and we have chosen to err on the side of inclusiveness to present a broader set of possible factors.

Economic Deprivation

Political violence is more likely to occur in countries with lower levels of economic development and less likely to occur in prosperous countries, making economic deprivation a risk factor. Overall level of economic development has been shown to be a significant predictor of civil war. Different authors have used different variables as indicators or proxies for development. Each of these has been shown to have a relationship with political violence: energy usage per capita,{7} per-capita income,{8} infant mortality,{9} and level of male secondary schooling.{10}

The simplest explanation for these relationships is probably wrong: insurgencies do not spring up solely because of a population’s anger about poverty or associated deprivations such as lack of education, health care, or employment. Deprivation may lead individual poor people to participate in “bread riots” or to commit property crimes, but it does not directly lead to organized, sustained insurgencies.

It is also true that political opposition occurs in all settings, including more developed countries; and revolutions are usually led by wealthier and more educated members of society. Deprivation alone is rarely used by non-Communist groups as a narrative to explain their actions, although it is may be given as a justification after the fact of a successful revolution.{11}

Poverty is generally considered to be an indirect contributing factor and not a primary cause of political violence. Poverty may lead young military-age men to feel that they have fewer options in life and less to lose, making joining an insurgency a more attractive option. Poverty does tend to increase property crimes, which may desensitize populations to lawlessness and violence, create a criminal class and illegal markets to support insurgencies, and undermine the government’s legitimacy.

Successful Communist revolutionaries understood these dynamics very well. Their goal was to convince peasants over time that their poverty and deprivation were the fault of the elite and the government, but they saw little value in entering a village and immediately exhorting the poorest villagers to rise up against their oppressors. Before seeking recruits for a class struggle, Maoists did a great deal of groundwork learning about very specific local grievances and teaching villagers to blame these things on wealthy landowners and the government. Equally important, they worked to build the complex social, organizational, and ideological infrastructure needed for an effective insurgency, as will be described in the following chapters of this book.

Theda Skocpol’s well-regarded comparative study of three revolutions illustrates these points.{12} The three revolutions were France 1789} (the French Revolution), Russia 1917} (resulting in the takeover of Feninists), and China 1911–1949 (resulting in the takeover of Maoists). Each of these featured peasant revolts was motivated in the long term by economic exploitation and in the short term by food shortages or other economic failures. But it is the author’s view that

In all agrarian bureaucracies at all times, peasants have had grievance enough to warrant, and periodically spur, rebellions.... Economic crises (which are endemic in semi-commercial agrarian economies anyway) ... might substantially enhance the likelihood of rebellions at particular times. But such events ought to be treated as short-term precipitants of peasant unrest, not fundamental underlying causes.{13}

In order to foment revolution, each of the three cases required other elements to be in place, specifically (1) outside military and economic pressure from other countries that were modernizing faster and undermined the ruling bureaucracies and (2) parallel movements led by “marginal elites” for their own reasons. These political elites, such as the Maoist Communists in China, might assist the peasantry in forming a cohesive identity, organizing across distance, and mobilizing in a coordinated fashion. In the French and Russian cases, there was less direct coordination between elites and peasants, but there was coincident timing and mutual inspiration between peasant anti-landlord movements and urban anti-government movements. Other details relating to the structure of the central bureaucracy, loyalties of the army, and external pressures also play important roles in determining the course of events. Poverty and deprivation laid the groundwork for revolution, but other instigating factors were needed.

Ted Gurr’s influential 1970} book Why Men Rebel{14} proposed relative deprivation as another related factor. Relative deprivation is a mismatch between peoples’ level of expectation and their economic reality. Impoverished peasants with no expectations for improvement have no reason to risk what little they have on an insurgency. But groups that have experienced sudden changes of fortune, are jealous of peer groups who are prospering more, or have had expectations raised for other reasons may experience more discontent. This discontent, in the right circumstances, can lead to organized rebellion. The revolutions of France, Russia, and China studied by Skocpal{15} fit this pattern, because in each case the nation was failing to modernize as fast as their neighbors, leading to widespread dissatisfaction among elites who were in a position to observe their comparative failures. Also, fitting with the theory of relative deprivation, the thwarted ambitions of educated and underemployed youths in Middle Eastern countries such as Tunisia and Egypt have been blamed for high levels of political discontent (see the Demographic Youth Bulge section).

Subsequent research questioned whether relative deprivation is a reliable predictor of revolution,{16}{17} although it may be an important component of the political grievances of marginalized subgroups. Like economic deprivation, relative deprivation is considered to be a general risk factor but only an indirect cause of political violence.

Poor Governance

A country’s system of governance can, not surprisingly, be an important risk factor. But what kinds of governments are the most at risk for violent insurgencies? One might expect the most violent and repressive governments to be the most at risk, but the answer is more complex than this.

There is general agreement that the most democratic governments are the least vulnerable to violent insurgency. This does not mean they are free from opposition or dissent—far from it. But open democracies offer nonviolent channels for opposition, including elections, public protests, and many other forms of free speech. Most opposition groups realize that they have better options than trying to take on the central government with military force, and radicalized groups have difficulty rallying citizens to their cause when other, safer options are available.

Highly repressive regimes offer no such avenues. The most repressive regimes prevent opposition groups from forming, even informally, and prevent alternative messages from being heard. Established regimes have effective secret police embedded throughout the population who are not held in check by any legal restrictions on intelligence gathering, interrogation, or arbitrary arrest. Most dissent is quashed before it can gain any momentum. Modern North Korea is an example of a highly repressive but stable regime.

Most modern states fall somewhere in between full democracy and the most repressive dictatorships. These blended regimes are sometimes called hybrid regimes or anocracies. These regimes may allow opposition political parties but rig elections so that the ruling party is never seriously challenged; they may restrict political freedom but allow a great deal of economic freedom; or, as in recent times, they may restrict the media but allow relatively free Internet access.

Researchers in this area often make use of the Polity project dataset,{18} which assigns democracy ratings to every country with more than 500,000 people for every year since 1800. Every country-year has been assigned a “Polity” score between -10} and 10, with -10} being the most repressive regime and 10} being the most democratic. Polity scores take into account these subcomponents: competitiveness of political participation (are elections really contested?), regulation of political participation (who can vote?), competitiveness of executive recruitment (are high-level positions really contested?), openness of executive recruitment (who can be appointed?), and constraints on chief executive (checks and balances).

One interesting but controversial finding is an inverted U-shaped relationship between a nation’s Polity score and the likelihood of political violence in that country.{19}{20}[2] a The theory is that countries at the far ends of the continuum—the most autocratic and the most democratic— are the most stable, because democracies allow nonviolent opposition and complete autocracies effectively quash dissent. Anocracies, which have a mix of democratic and autocratic policies, may be the most unstable. The reason for this would be that the hybrid governments allow enough freedom of speech and assembly to allow opposition groups to form but are autocratic enough that challengers are often put down forcefully, causing opposition groups to believe they must resort to violence to achieve their aims. These hybrid governments “possess inherent contradictions ... (they) are partly open yet somewhat repressive, a combination that invites protest, rebellion, and other forms of civil violence. Repression leads to grievances that induce groups to take action, and openness allows for them to organize and engage in activities against the regime.”{21}

Lack of Government Legitimacy

Beyond style of governance, the perceived legitimacy of the government is an important predictor of its ability to govern especially in the face of challenges; legitimacy has become a core concept in counterinsurgency theory. A government has legitimacy when it is perceived as having both the right to rule and the competency to fill expected functions of government. These are the most important factors affecting legitimacy:

-

Security. People who experience threats to their physical safety tend to lose faith in their government. This is particularly true when threats are internal, from crime, insurgency, or terrorism, rather than external threats, which tend to evoke a unifying reaction. (Not surprisingly, governments tend to blame internal security problems on “outside agitators” or external manipulation whenever they can.) Terrorism is often an attempt to undermine a government’s legitimacy by undermining people’s sense of security.

-

Justice. Governments are expected to settle disputes fairly and quickly. Widespread corruption in the judicial system undermines legitimacy. Many countries with widespread corruption rely on alternate judicial systems, such as the Shura system in Afghanistan and adoption of Shari’a law in a number of states in northern Nigeria; these work-arounds undermine the legitimacy of federal governments.[3]

-

Economic needs. Governments are expected to make sure people of the nation are fed and to meet their other basic needs, which could include fuel, roads and utilities, health care, education, and employment. Expectations for what services a government should provide vary widely between cultures and nations and are closely tied to both prior conditions and conditions of immediate neighboring countries. Widespread corruption, by which employment, health care, and other services can only be obtained through bribes or connections, can undermine legitimacy (although judicious use of patronage can in some circumstances increase it).

-

Ideological legitimacy. Cultures also have idiosyncratic expectations for what constitutes a legitimate government. Religious leaders may undermine a government by withholding sanction or declaring the government illegitimate. The Catholic Church in the past held such power over many European states (Henry VIII founded the Church of England because he could not obtain legitimization by the Roman Catholic Church). Modernday Islamists often direct their most vehement criticism at secular leaders of Muslim nations who do not meet their standards for Islamic rulers. Nonreligious ideologies also matter; governments may forfeit legitimacy for violating strongly held ideals of freedom and democracy or other values that a population feels to be ideologically nonnegotiable.

Legitimacy is ultimately a subjective judgment in the eyes of the governed. Regimes that provide poorly for their people by the standards of developed democracies may nevertheless enjoy a high standing with their own people. However, exposure to information from outside, particularly related to peer nations, may be enough to engender dissatisfaction. Information and communication with the outside world are therefore important determiners of legitimacy and something that underperforming governments will have good reason to try to control. Attacking the government’s legitimacy is almost always a central theme of the war of words between insurgents and the government.

Marginalization or Persecution of Identity Groups

Perhaps the strongest and most immediate risk factor for radicalization is the systematic marginalization or persecution of identity groups in a country.{22} Politically, the most important identity groups tend to be based on ethnicity but can also be tribal, religious, political, ideological, regional, or economic.

A number of researchers have asked whether ethnically diverse countries are, in general, more prone to civil violence. Earlier models included measures such as Ethno-Linguistic Fractionalization, which is a simple measure of how diverse a country is.{23} But ethnic diversity taken by itself does not appear to be a risk factor; {24}{25} many countries have peacefully coexisting religions and ethnic groups.

Risk of political violence is great, however, when diversity is combined with some form of economic or political exclusion. Violence is particularly likely when a minority group controls the central state government and excludes other groups,{26} even if those groups have some level of local autonomy. State-led discrimination of other forms is also a strong predictor of political violence.{27}

Systematic discrimination against minority groups can endanger otherwise democratic societies. Groups usually turn to organized, violent resistance only when they believe they have no nonviolent alternatives. When a minority group believes it is systematically excluded from the democratic process, violent resistance becomes a more likely option. The Irish Republican Army (IRA) persisted within the democratic nation of Great Britain because of their Irish Republican feelings of exclusion. The civil rights movement in the United States may be seen as another example. The United States has always taken great pride in its democratic institutions, but the systematic exclusion of African Americans from these institutions led to violence during the civil rights movement and to the brink of what might have become organized insurgent-type activity.

To understand the typical types and ranges of discrimination, it is interesting to look at the criteria for discrimination used by the ongoing Minorities at Risk (MAR) project.{28} Data from this project are often used in high-level studies of political violence and discrimination. This effort monitors the treatment of minority groups identified as being at risk for discrimination. As of 2011, the project is monitoring 283} at-risk ethnic groups across the world; archived data go back to 1945. MAR examines a wide range of types of discrimination and rates each type on scales that increase from 0 to 4 or 5. Paid raters working for this project scour news archives and other sources to find evidence of different kinds of discrimination to inform these ratings. Criteria for ratings of government repression, political discrimination, and economic discrimination categories is listed in Table 2–1.

Table 2–1. Code Guidance for Three Discrimination Categories From the Mar Dataset

| Rating | Government repression | Political discrimination | Economic discrimination |

| 1 |

Surveillance, e.g., domestic spying, wiretapping, etc. |

Neglect/remedial polices Substantial underrepresentation in political office and/or participation due to historical neglect or restrictions. Explicit public policies are designed to protect or improve the group’s political status. |

Neglect/remedial polices Significant poverty and underrepresentation in desirable occupations due to historical marginality, neglect, or restrictions. Public policies are designed to improve the group’s material well-being. |

| 2 |

Harassment/containment, e.g., saturation of police/military presence, militarized checkpoints targeting members of group, curfews, states of emergency |

Neglect/no remedial policies Substantial underrepresentation due to historical neglect or restrictions. No social practice of deliberate exclusion. No formal exclusion. No evidence of protective or remedial public policies. |

Neglect/no remedial policies Significant poverty and underrepresentation due to historical marginality, neglect, or restrictions. No social practice of deliberate exclusion. Few or no public policies aim at improving the group’s material well-being. |

| 3 |

Nonviolent coercion, e.g., arrests, show-trials, property confiscation, exile/ deportation |

Social exclusion/neutral policy Substantial underrepresentation due to prevailing social practice by dominant groups. Formal public policies toward the group are neutral or, if positive, inadequate to offset discriminatory social practices. |

Social exclusion/neutral policy Significant poverty and underrepresentation due to prevailing social practice by dominant groups. Formal public policies toward the group are neutral or, if positive, inadequate to offset active and widespread discrimination. |

| 4 | Violent coercion, short of killing, e.g., forced resettlement, torture |

Exclusion/repressive policy Public policies (formal exclusion and/or recurring repression) substantially restrict the group’s political participation by comparison with other groups. (Note: This does not include repression during group rebellions. It does include patterned repression when the group is not openly resisting state authority.) |

Exclusion/repressive policy Public policies (formal exclusion and/or recurring repression) substantially restrict the group’s economic opportunities in contrast with other groups. |

| 5 |

Violent coercion, killing, e.g., systematic killings, ethnic cleansing, reprisal killings |

Besides the three variables listed in columns here, MAR also records the history of violent conflicts between groups (not necessarily involving the government), grievances expressed by group leaders, and protests and rebellion by group members.

The social psychology of relationships between social identity groups (“in-groups” versus “out-groups”) will be discussed extensively in Chapter 6: Group Dynamics and Radicalization, and elsewhere in this work.

History of Conflict in the Country or Conflict in Nearby Countries

Countries with a history of violence are more likely to experience violence in the future.{29} The same is true for countries whose geographic neighbors have experienced violence. There are both psychological and non-psychological reasons for this. The simplest cause may be the available supply of weapons and people trained to use them, either in-country or nearby. When one conflict ends or dies down, both weapons suppliers and soldiers may be unemployed and have few other skills; they may return to their home countries or cross borders as mercenaries. A second reason for the bleed-over of violence across borders may be large numbers of refugees or other displaced persons. These refugees may strain the resources of new areas, leading to violence. Or the refugees may hold claims on their prior land (such as displaced Palestinians) or have other grievances (e.g., lost relatives and friends) to be redressed with violence in a new location.

There are also psychological processes at work that create secondorder effects of regional violence. Populations can become desensitized to violence, which leads to more violence.

Wartime crime rates give some evidence for this. American sociologists Dane Archer and Rosemary Gartner{30} were among the first to show that homicide rates increased during wars and continued to be higher after the wars ended. They found that homicide rates were higher in countries that were involved in World War II than in nations that were not; in Italy, the homicide rate more than doubled. Similarly, the homicide rate increased in all six nations involved in the Vietnam War. In the United States, despite the fact that none of the fighting took place on U.S. soil and that large numbers of the demographic group responsible for homicides (young men) were fighting overseas, the homicide rate increased every year of the war, peaking in 1973} at a rate 107 percent higher (more than double) than the prewar rate. Of course, other dramatic changes were taking place in the United States at that time, including anti-war protests and the civil rights movement, but the effect holds statistically across many other nations in different situations. The increase in homicide rates holds across both victorious and defeated nations, and is, in fact, higher in victorious nations. Countries with more battle deaths experience subsequently higher homicide rates. These increases in violence cannot be attributed solely to violent or battle-scarred veterans; more violent crimes are also committed by women and older age groups during and after wars.

Most humans have natural inhibitions toward violence, and all cultures have norms and practices designed to prevent and manage violence. Wars and political conflicts can desensitize people to violence on a large scale, making many kinds of violence more likely.

Desensitization has been demonstrated in many different settings. Most of the relevant research has been done with children. Children who witness adults behaving aggressively, for example, by pummeling a stuffed animal, tend to imitate that aggression. Children who watch violent television or play violent video games have more aggressive thoughts and behaviors, less empathy toward victims, and lower physiological reactions when witnessing violence.{31} And children exposed to actual violence show a range of negative stress reactions that persist long after the events.{32} Similar results have been found with adults.

Being witness to violence does not universally cause violence. No amount of watching violent television or playing violent video games will make a child violent if they are not predisposed. Exposure to violence will lead some to commit more acts of violence, through desensitization or simple imitation, and desensitization on a large scale can affect how quickly people intervene or punish incidents, and generally weaken cultural mores that prevent violence.

There is also speculation that some national and regional cultures may be predisposed to violence, beyond the effects of recent conflicts. Generalizations about entire cultural groups tend to be controversial and might even be considered a form of racism, so there are not many empirical studies or findings on this topic. One of the few examples is Nisbett’s study of differences in the reactions of males in the north and south of the United States to minor insults. Nisbett found what he describes as an “honor culture” in the south, with a cultural imperative to preserve honor by retaliating against even minor acts of aggression. The presence of honor cultures has been tied to levels of interpersonal conflicts and low-level feuds. There may be geographic and economic reasons for these norms, e.g., the need for herdsmen to establish a tough reputation to prevent theft, but the culture seems to persist even when the underlying circumstances change.{33} Similar dynamics of honor and retribution are common (but not ubiquitous) in the Middle East.{34}

Demographic Youth Bulge