Products of Desire

On Loving the Unreal

Moe: Exploring Virtual Potential in Post-Millennial Japan

Making It Real: Fiction, Desire, and the Queerness of the Beautiful Fighting Girl

Moe: Exploring Virtual Potential in Post-Millennial Japan

Original article at https://www.academia.edu/3665389/Moe_Exploring_ Virtual_Potential_in_Post-Millennial_Japan

Making it Real: Fiction, Desire, and the Queerness of the Beautiful Fighting Girl by Keith Vincent, from Beautiful Fighting Girl by Tamaki Saitou, tr. Keith Vincent and Dawn Lawson, University of Minnesota Press, 2011

Otaku Talk

original article located at https://www.gwern.net/docs/eva/2004-okada

Products of Desire

On Loving the Unreal

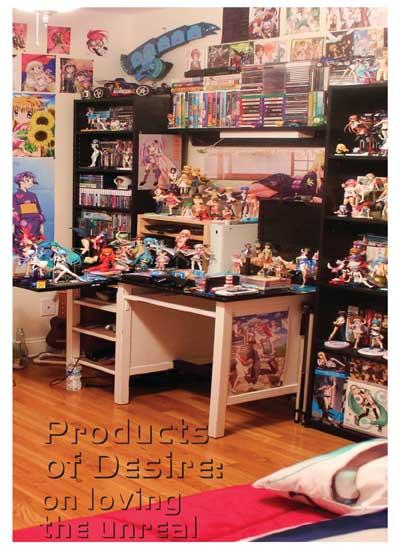

I hesitated to make this pamphlet because it’s about something so ridiculous yet intimate. Despite the often academic prose of these articles, it’s hard not to feel a bit exposed by their contents. If you’ve ever seen one of those iconic images of a fan’s bedroom— those immaculately decorated exemplars of horror vacui with every inch covered in (often lewd) posters and (often expensive) figures—this is the territory we’re stepping into. In a way, however abstract the writing may sometimes be, I’m inviting you into my bedroom. At the heart of this writing is always this space of intense desire. Perhaps this is a space you’re already familiar with—maybe it’s your bedroom too, or maybe you’ve only caught glimpses of it in the shadier portions of the internet. Perhaps you just felt weird watching Disney’s Robin Hood when you were younger.

The desire discussed here is focused on otaku (anime fans) because of the richness of critical examinations surrounding them (as well as because of the specific interests of this author), but the ideas discussed could apply to cartoon fans in general, to furries, or to any of the many circles in which deep affection is felt for the unreal. The point is to explore that desire, however briefly, to see what it does and where it goes.

A subject of interest to two of the authors contained herein is how love for the unreal implicates any stable concept of reality itself. For J. Keith Vincent, writing about Tamaki Saitou’s[1] Beautiful Fighting Girl (Saitou himself drawing on Lacanian theories around perceiving reality), there is a queerness to this attraction that “decouple[s] sexual desire from social identities and naturalized bodies”. Patrick Galbraith’s[2] treatment of moe (pronounced mo-ay and defined by him in short as an intense emotional response to a fantasy character) finds in this desire for the unreal a “certain refusal” of dominant forms of life founded in the home and family, and connects this (however briefly) to Lee Edelmen’s refusal of “reproductive futurism”. Vincent’s piece offers a more comfortable vision of the desiring subject (ultimately “there is a little otaku in all of us”) to Galbraith’s more expansive and transgressive moe, but both give us different and insightful takes on similar subject matter.

Our final piece, an excerpt from a discussion between Toshio Okada[3] and Kaichiro Morikawa[4] and moderated by Takashi Murakami[5], further highlights a tension that the reader will see in both of the aforementioned pieces: the question of how different these people actually are, despite their exotic tastes. The otaku’s response to dominant reality is debated—Morikawa claiming that moe, rather than more clearly political or utopian thinking in science fiction, “has replaced the future.” Morikawa also characterizes otaku as those who gravitate towards socially unacceptable things. Okada however describes them as merely a different kind of consumer: “tough customers who demand high standards,” discerning consumers who value quality.

In the end, the desires featured in these articles don’t appear to be a way out—in some cases far from it. We are presented again and again with the otaku who, despite having this potentially challenging view of the world, is living an otherwise unremarkable life within capitalism. Thus, the title of this work: these characters are produced by our desire for them—they are ethereal, ultimately unrealizable in the world we live in—yet there is also an intense being to them, their presence realized in the form of commodities.

One of the sad lessons of works like this is how pretty much any kind of desire can be penned into a niche market, and any excitement over the otaku’s queerness by academics such as Vincent, exists alongside the fact that transgressive practices may form the creative vanguard for capitalism’s eternal search for new markets.

It’s here that I reach my second point of hesitance for this work—where is anarchy in all of this? What’s remarkable about turning away from reality or imagining an existence entirely different from this one, when we continue to exist within it, still less when one’s activity is based on an intimate relationship with companies that produce the objects of our desire? When compiling this pamphlet, I lacked a ready answer to this question. Generally speaking, I find fan spaces interesting and have enjoyed the time I’ve spent among the people in them. There are ways of relating to each other—high levels of difference among people negotiated in the same community, a suspension of many of the normal rules that govern us, and ways of sharing with and supporting each other that feel familiar to me when I think of some of the better anarchist spaces I’ve been in. I have a sense of affinity with furries who won’t take off their tails when they go out the door, and find something heartwarming about the fact that their conventions are widely known for being accompanied by orgies (fursuits and all). And on a very base level I take heart in fantasies that are socially disruptive—the more people living with their parents in rooms full of toys instead of working or having children the better.

All of this—positive and negative—is I think informed in part by this love of the unreal (and a consequent turning away from the real), and my hope is that this work will open up some space for those of us who are fans to talk about the implications of our desires. And in case you’re one of those weirdos who haven’t found themselves bathed in the light of their computer screen crying their eyes out over some beautiful bundle of lines and sound, I hope you’ll take something from this as well, for there exists yet another point of affinity between anarchists and fans in the “virtual potential”. Much like fans, the anarchist imagination disturbs the real, opening spaces of intensity in which we can explore “new possibilities of being”. The recognition that the reality we inherit from the world we are born into is a product, and not one we want, offers the exciting and exacting possibility of our lives, relationships, and the world around us taking on new forms “without limit or control” shaped by our desires. Where Galbraith makes the subject of his paper a world of potential—boundless and transgressive but rarely realized in a way that deserves the moving description he gives us—we, with a nod to fursuiters and hardcore otaku, take the suspension of the real as an opportunity to manifest our imagined worlds as much as possible, becoming the reality of our lives.

excerpt from

Moe: Exploring Virtual Potential in Post-Millennial Japan

by Patrick W. Galbraith

Emergence of the Moe Form

Moe is affect in response to fantasy forms that emerged from information-consumer culture in Japan in the late stages of capitalism. Otaku scholar Okada Toshio states that moe is most strongly felt among ‘third-generation otaku,’ or Japanese born in the 1980s who watched Neon Genesis Evangelion in middle school and grew up amid a wealth of anime, manga, games and character merchandise following the seminal anime series. As Okada sees it, ‘There is a strong tendency among this generation of otaku to see otaku hobbies as a form of “pure sanctuary”’ (Okada 2008: 78). The use of ‘pure’ here should not be overlooked. The period of advanced economic development and material affluence from the 1960s to the 1970s was also the time when anime, manga, game and character merchandisers in Japan promoted extreme consumption among youth. Ootsuka Eiji, for example, explains the conditioning of young girls into ‘pure consumers’ (junsui na shouhisha) (Ootsuka 1984). To expand the consumer base, marketers disseminated an image of cute (kawaii) in fashion magazines and shoujo (for girls) manga, and encouraged young women to buy cute merchandise and accessories to fill up their rooms and construct identity. Such a space is disconnected from social and political concerns, and exists for the preservation of the individual. Broadly, the same argument can be made for otaku subculture, which Ootsuka states was surrounded by media and unconcerned with the social and political in the 1980s, and Azuma argues consumed as a way to build personal and group identity. Indeed, Ootsuka has suggested that today many Japanese, including boys, are becoming ‘shoujo’ (little girl) consumers in that they are surrounded by comforting media and merchandise and consume endlessly to support their spaces and notions of self. This resonates with Okada’s description of otaku as retreating into hobbies as a pure sanctuary, and with Honda’s discussion of moe men as feminized, or rather shoujo-ized. Therefore we can say that moe is connected with the rise of media (anime, manga and videogames) producing fantasy ideals and consumer culture providing material to support those fantasies.

Further, the media and consumption feeding into moe is a specific sort centered on affect. As mentioned above, the 1980s saw a blossoming of media and material targeting otaku, and this conditioned a pattern of consumption and culture. Eventually the products began to be designed specifically to elicit an emotional response in the consumer, i.e., to include characters that would inspire moe. Manga scholar Itou Gou argues that since the end of the 1980s characters in anime, manga and videogames became so appealing that fans desired them even without stories (Itou 2005). Ito dubs such character types ‘kyara,’ distinct from characters (kyarakutaa) embedded in narratives. The reality of characters is their life-like nature, but kyara are defined by a ‘reality of kyara’ (fiction) distinct from reading human characteristics and following social understandings (Itou 2005: 118). Proof of this can be found in the rise of ‘parody’ doujinshi, or fan-produced comics placing favorite characters from anime, manga and videogames into new settings and often pornographic relationships. Comiket, Japan’s largest market for doujinshi, reports that both men and women writing such character-based doujinshi increased drastically in the 1980s. Popular anime series like Urusei Yatsura (1981–1986), which featured a boy surrounded by beautiful girls, and Captain Tsubasa (1983–1986), the story of an all-boys soccer team, provided virtual harems that were for many fans more important than the original story. Thus the focus shifts from what Ootsuka calls holistic ‘narrative consumption’ (monogatari shouhi) to make meaning to what Azuma calls fragmentary ‘database consumption’ (deetabeesu shouhi) to make moe, or produce affect. Shifting the focus to kyara, or placing a character in narrative stasis, reduces concerns of consequence related to reality (the narrative) and creates a sensual, liminal experience. The further away from reality and limitations on form the greater the virtual potential and affect. This affect-logic is at the heart of moe. Moe is a response to kyara, or characters without context or depth, and is made possible by flattening characters to surfaces upon which to project desires.

The threshold in the development of moe came with the breakdown of narratives and social frames and the rise of pleasure experience in the recessionary 1990s. Identity could no longer be sustained in eroding nakama groups at home, school and work (Yoda and Harootunian 2006), and youth began an accelerated process of building world and self through consumption and hobby activities (Azuma 2009). The origin myth of moe centers on the early 1990s in archetypes such as Sagisawa Moe (Kyouryuu Wakusei, 1993–1994) and Takatsu Moe (Taiyou ni Sumasshu!, 1993), the former a series for kids and the latter for girls (Morikawa 2008). The word became widespread as an abbreviation of Hotaru Tomoe from Sailor Moon S (1994–1995). All of these characters are young girls, and display a set of moe characteristics: large, pupil-less eyes, glossy skin, small (or no) breasts and an innocent or pure personality. Azuma posits that a turning point came with Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995–1996), an immensely popular TV anime produced by studio Gainax. Evangelion features a female character named Ayanami Rei, a synthesis of different character types: a clone of the protagonist’s mother housing the soul of an otherworldly being in the body of an adolescent girl. The doll-like and semi-human Ayanami became the single most popular and influential character in the history of otaku anime; fans still isolate parts of the character to amplify and rearticulate in fanproduced works to inspire moe. After the success of Ayanami, the focus shifted to kyara with moe traits in lieu of story.[6] The prime example is Dejiko, a cute little cat girl with absolutely no story who became the mascot of anime merchandiser Gamer’s in 1998. Azuma points out that this character, an idol among otaku, is an amalgamation of codes from the moe database: a maid outfit, cat ears (nekomimi), giant saucer eyes, a saccharine voice and so on (Azuma 2009). Characters like Dejiko whose main purpose is to inspire affect are called moe characters (moe kyara). In works featuring these characters, the original work functions as a starting point, and the extended process of producing and consuming moe takes place among fans in online discussions and videos, fan-produced comics (doujinshi), costume roleplay (cosplay) and figures.

The moe character is a product of the breakdown of the grand narrative and rise of simulacra (Azuma 2009), and its form is one of unbounded virtual possibility. Concretely, a moe character is what Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari describe as a ‘body without organs,’ or the ‘virtual’ dimension of the body that is a collection of potential traits, connections and affects (Deleuze and Guattari 1987). These potentials are accessed by overcoming binary oppositions that order and control the body. It is not without significance that moe characters regularly exhibit ambiguity and contradictions – child-adult, male-female, animal-human – and that these bodies that are (both literally and figuratively) denied organs have increased virtual potential. Critics point out that characters described as moe have always tended to be physically immature ‘little girls,’ but Deleuze and Guattari suggest that ‘becoming woman’ is the first stage to becoming everything else.[7] Just so do these moe characters endlessly ‘sprout’ new forms and fantasies. The pursuit of moe is thus exposing and reacting to the body without organs, to virtual potentiality. Affect is a response to unstructured or unformed potential (Massumi 2002). That the moe form, the body without organs, is outside personal and social frames is precisely why it triggers affect. Fantasy forms and affects are fluid and amorphous, which perhaps resonates with youth who are exploring new possibilities of being in post-millennial Japan.

Otaku Discussions of Moe

Moe, a word describing affect in response to fantasy forms, appears a theoretically predictable development given the rise of character-oriented media and merchandise in Japan in the 1980s, which contributed to a ‘pure consumer’ space occupied by a certain generation of young Japanese otaku. However, perhaps no word in history has so divided otaku. Okada, who famously defined otaku culture as deep and narrow in focus, sees in ‘moe otaku’ a superficial fixation on surfaces and accelerated consumption of disposable moe kyara, impetus for him to declare this younger generation culturally ‘dead’ (Okada 2008).[8] On the other hand, those otaku who cannot dismiss moe have for the better part of a decade been discussing that which so compels them. In practice, moe means both love and a mild sexual arousal felt for fantasy characters. As Azuma points out, this is a flexible response to discrete elements.[9] When defined, however, the emphasis tends to be on pure love, which resonates with Honda. One man I spoke with said, ‘Moe is a wish for compassionate human interaction. Moe is a reaction to characters that are more sincere and pure than human beings are today.’ Similarly, another man described moe as ‘the ultimate expression of male platonic love.’ This, he said, was far more stable and rewarding than ‘real’ love could ever be. Manga artist Akamatsu Ken stresses that moe is the ‘maternal love’ (boseiai) latent in men,[10] and a ‘pure love’ (junsui na ai) unrelated to sex, the desire to be calmed when looking at a female infant (biyoujo wo mite nagomitai) (Akamatsu 2005). ‘The moe target is dependent on us for security (a child, etc.) or won’t betray us (a maid, etc.). Or we are raising it (like a pet)’ (Akamatsu 2005). This desire to ‘nurture’ (ikusei) characters is extremely common among fans. Further, moe is about the moment of affect and resists changes (‘betrayal’) in the future, or what Akamatsu refers to as a ‘moratorium’ (moratoriamu). Moe media is approached as something of a sanctuary from society (Okada 2008), and as such is couched in a discourse of purity.

A more nuanced report by and for fans suggests that perhaps both the pure and perverse are potential moe images. The author, Shingo, defines moe as a response to a human(oid) entity who is innocent, gazed at and becomes embarrassed (Shingo 2005). He then establishes four categories of moe based on imagined access to or distance from the character: junai (pure love), otome (maiden), denpa (kinetic) and ero-kawaii (erotic-cute). Shingo proposes four principles to understand moe:

-

A moe character cannot be aware of her own appeal.

-

The greater an image’s emphasis on style and fetish symbol at the expense of narrative, ambience and relationships, the less relevant propriety becomes.

-

The closer the viewer (or his narrative proxy) becomes to a moe character, the harder it is for her to maintain her sense of propriety.

-

The viewer’s emotional response to a moe image is a function of the convergence of his position relative to the image with the heroine’s state of maidenly virtue as depicted therein.

Comparison with Honda and Azuma is fruitful here. As Honda states, moe is imaginary love, and the affect is based on ‘emphasis on style and fetish symbol at the expense of narrative,’ or what Azuma would call moe elements. Shingo seems to suggest that there is a defined character to moe, and whether a moe character is pure or erotic is a function of the sexual access provided to the viewer or his (or her, though Shingo is focusing only on male otaku and their objects of desire here) avatar.

However, moe characters are fantasy forms animated by fluid desires, and as such cannot easily be divided into static categories. A range of possible responses is present in the same character. A pure character can be approached as erotic, or vice versa, and the elements are rearranged in fan productions to stimulate moe. Further, Azuma has successfully argued of dating simulator games that the propriety of the character is not always challenged by relative access. The narrative connecting moments of pleasure is absent, so the character’s status as pure can coexist with perverse sex acts. This challenges Shingo’s third and fourth assertions, but it is not irreconcilable. As Shingo himself states, ‘two-dimensional characters are moe precisely because they are depicted in two dimensions, and it is this reduction, simplification, lack of pretense – it is this lack that allows the heroine to preserve her virtue unquestioned by the viewer’ (Shingo 2005). If a character begins its existence in a certain range of moe, then it can also be re-imagined in different ranges. For example, Ayanami Rei is the vision of a pure character in the original Neon Genesis Evangelion: She is a 14-year-old virgin who in turn plays the role of both mother and daughter for various characters. She is also a clone and carries the soul of an angel, a non-human entity separate from reality and so a form of ‘pure fantasy.’ Despite her myriad persona, it is notable that Ayanami does not play the role of a lover or wife. The original does not provide desires that can be consummated; in Shingo’s terms, the ‘access’ is zero. However, in fan re-articulations made in pursuit of moe she is a target for mating and marriage, or the access is increased to the maximum. It is precisely because these ranges in the moe spectrum were not explored in the original narrative that they are exposed as virtual possibilities of the fantasy form of the character. Importantly, Ayanami can be both an entity to be nurtured and one that is highly sexualized (often transgressively so) at the same time. This is because she is approached as a moe character removed from her original context and limitations on the possibilities of her character (i.e., range of intended affect).

Moe Desire and Sexuality

As discussed above, most otaku stress emotional rather than sexual needs for moe characters, but the image of the girl-child is clearly eroticized. While Honda posits this as a balanced gender identity, it appears somewhat problematic to simultaneously protect (coded as female) and prey (coded as male) on the child in pursuit of moe, even if only in the realm of fantasy. Psychoanalyst Saitou Tamaki discusses otaku sexuality as ‘asymmetrical desire,’ or ‘a sexuality deliberately separated from everyday life’ (Saitou 2007: 245). Saitou argues that otaku sexuality depends on ‘fantasy contexts’ (kyokou no kontekusuto), or what Itou has called the ‘reality of kyara.’ What sort of sexuality is conditioned in interaction with moe characters, with pure fantasy? Consider for example dating simulator games. Interestingly, these games are often not very sexual beyond teasing images of girls in various states of undress; sexual representation stops short of vaginal penetration. There are more explicit variants,[11] but in recent years these have given way to so-called novel games,[12] which are extremely text heavy and feature few, if any, images of sex (Azuma 2009). They usually take place in idyllic school settings among fantasized youth. It is in essence nostalgia for a past that never was. Player choices are reduced and the emphasis is on passively experiencing emotional melodrama, almost like reading a romance novel (recall again the discourse on feminization of otaku in moe). These games are often called nakige (crying games) because the objective is ‘to cry’ (Azuma 2009: 76), which makes sense given Honda’s explanation of moe as a mechanism for men to indulge the feminine restricted by social norms (Honda 2005: 16). However, be it a moment in the original or an extended scene in fan production, these characters are sexualized for masturbatory fantasy. The pleasure derived from moe characters is not always physical, but is masturbatory because, even when emotional, the pleasure is derived by and for the individual. Both the possibility of purity in feelings for and as the female character and the possibility of subversive stimulation as sexual predator exist simultaneously, and this schizophrenic sexual expression exists as a mediated construct between the solitary player and the images reflected on his screen.[13] In games intended to inspire moe, the all-important purity is affirmed even as it is implicitly violated.[14]

In such media, sexuality is deferred as long as possible and, when indulged,[15] often takes the form of abuse. Moe characters are most typically youthful, innocent girls, and such characters regularly appear in dating simulators. As Akamatsu states, it is the pre-violation child that is moe, or that which does not know the world and is fetishized as pure. However, while protecting and nurturing, the child becomes a lover.[16] This theme is so pervasive that it has become a genre onto itself, ‘nurturing simulation games.’ Not surprisingly, Gainax, the company that created Ayanami Rei and helped propel the trend of moe characters, is known for making these nurturing games. Examples include Princess Maker in 1991 and Ayanami Nurturing Project in 2001. Just as Azuma points out a gradual de-sexualization of dating simulator games, later editions of Princess Maker present the player the option of being a mother with zero sexual access to the daughter (=moe object) in the game, even as the player is visually stimulated by his daughter. In all cases, the passive, emotional (coded as feminine) desire to care is juxtaposed with an aggressive, physical (coded as masculine) desire to mate. Both purity and perversion are expressed in extremes, and the existence of one makes the other possible. The original purity of Ayanami is precisely why she is so perversely abused. The girl-child inspires moe in polymorphous forms because she is tied to a moment without past (context) or future (consequence).

The emphasis on youth in moe is another aspect that demands attention. For example, a common moe character type is the little sister (imouto). Honda explains the little sister as representative of the pure otaku desire for family, which would also ostensibly account for the daughter character in the nurturing fantasy. However, we cannot ignore that the first erotic animations in Japan, Lolita Anime and Cream Lemon in 1984, featured little girl and little sister characters, respectively. The conflation of child-like innocence and adult desire has been employed for decades in Japanese pornography surrounding schoolgirls. In most cases, uniforms, the fetishized signifier of innocent status and character, remains in spite of, and even during, sexualization to provide a target for desire.[17] One man I spoke with commented that archetypes of desire are formulated between age 12 and 14, and so it makes sense that youth in Japan surrounded by young girls in uniform would desire this; those who fixate on this archetype repeat it in media, in turn reinforcing the desire. This discourse problematically places all desire on early adolescence, but it made sense for this man and others like him who fixate on middle school, a time before social pressures to perform as a responsible adult at work (earn a salary) and home (start a family). That time of purity and potential remains in ‘moratorium’ (Akamatsu 2005), even as those who access it often also remain in a state of moratorium outside society. Syu-chan, a self-proclaimed otaku in his thirties, explained his fetish for schoolgirl uniforms and related little sister characters in moe anime as coming from his inability to consummate the young love he dreamed of as an adolescent.[18] ‘By my late twenties I realized that what I didn’t have back then is what I will always want. I will always be single.’ When asked why he didn’t try to find a partner now as an adult, he explained that people like him – an otaku long on hobbies and passion and short on looks and money – are excluded from the market of love. For Syu-chan, it made sense to imagine a space of ‘pure love’ apart from reality. As the age of sexual and capitalist maturity becomes ever younger, for example ‘compensated dating’ among primary school students, the age of purity re-centers on even younger girls. The symbol of this was the little sister in uniform, but this does not equate to actual incestuous desire. This might be understood as first a longing for a time of youthful possibilities and hope (signified by the uniform) and second a desire for an uncompromising relationship not conditioned by society (the little sister). Moe characters are pure beings unspoiled by maturity. Put another way, they are not part of the world fans are reluctant to accept.

Moe characters express desires that are not of this world, and it is thus a logical conclusion that they would appear non-human. If kawaii, or the aesthetic of cute, is the longing for the freedom and innocence of youth, manifesting in the junior and high school girl in uniform (Kinsella 1995), then moe is the longing for the purity of characters pre-person, manifesting in androgynous semi and demi human forms. This is called ‘jingai,’ or outside human, and examples include robots, aliens, dolls and anthropomorphized animals, all stock characters in the moe pantheon. A specific example would be nekomimi, or cat-eared characters. More generally, in order to achieve the desired affect, moe characters are reduced to tiny deformed ‘little girl’ images with emotive, pupil-less animal eyes.[19] By reducing them so, the threat of real-world relational interaction is effectively removed from the fantasy, as is the potential for any real-life consequences. Moe is two-dimensional desire set outside the frame of human interaction. Therefore, the expression of sexuality can be ultra masculine or ultra feminine, but these possibilities are caricatures of human gender identities without connection or influence beyond the moment of virtual interaction.

Moe in Relation to “Reality”

The crucible of moe is a de-emphasis on the reality of the character and relations with the character. The people I spoke with described this as ‘pure fantasy’ – pure in the sense that it is unrelated to, and unpolluted by, reality. To produce this fantasy, characters are removed from a narrative (=context) and flattened (=emptied of depth). The response to these characters is de-centralized, unbounded euphoria, an affect that is verbalized as ‘moe.’ Azuma highlights the otaku remix culture in which it is possible to also isolate a character’s constituent elements, insert these into a ‘database’ and then rearticulate new characters in pursuit of moe. I will now demonstrate how it is further possible to reduce people to characters, or to reduce reality to fantasy in pursuit of moe. This reveals the essence of moe as a response to the virtual possibilities of characters outside the bounds of reality.

An example of the characterization of a living person is ‘cosplay,’ or ‘costumed role play’ as an anime or game character. Despite widespread misuse, cosplay culture as described by otaku is not wearing costumes for entertainment or erotic purposes, and it is also not a fashion that visually resembles a costume such as ‘gothic Lolita.’ Cosplay differs from fashion because the primary goal is not the pursuit of style, beauty or personal expression, but rather the enactment of two-dimensional characters. The ‘cosplayer’ (reiyaa) becomes a character; he or she makes a costume as close to an image as possible and memorizes character poses and spoken lines. When approached for a picture, the cosplayer attempts to recreate the aura of the character, and can request images not ‘in character’ be erased from the photographer’s camera. In this example of embodied anime and game culture, the cosplayer learns scripts from the mediated image of the character, enacts them and then becomes an image. It is precisely because the cosplayer becomes an image that the moe response is possible.[20] Honda refers to such a person as ‘2.5 dimensional’ (Honda 2005: 19), or a liminal existence between fantasy and reality. Cosplay is not mere eroticism, but rather a desire for the two dimensional, the image, for the virtual possibilities of the character.

This is even clearer in the example of maid cafés, a form of entertainment wherein young women cosplay as the titular characters. Cosplay cafés became popular in the late 1990s at sales events for dating simulator games; staff dressed up as waitress characters from games such as Welcome to Pia Carrot (1996). They were so popular that the first permanent café was established in 2001 in Akihabara, a major hub of otaku activity. As Morikawa Kaichirou explains, these cafés were at first spaces for otaku to rest after spending the day buying dating simulator games and doujinshi; they could relax indulging the thought that other customers were pursuing similar hobbies and the costumed staff were not ‘real’ people (Morikawa 2008). The structured relationships and familiar characters from games comforted otaku and simplified interactions. The maid character would later be codified as fantasy, including café rules not to expose any personal information, contractual obligations not to be seen by customers out of character and even a standards test to qualify those performing the character (Galbraith 2009). Since 2005, there has been a boom in cafés and rapid diversification of themes and services, but interactions with the costumed staff are still scripted by anime and games. For example, a maid might act belligerent, which customers would interpret as her inability to properly transmit her affection. That is, she secretly cares deeply for the customer, but cannot express herself, gets embarrassed and ends up acting coldly towards him before finally warming up. This is called tsundere, or ‘icy-hot,’ and is an extremely common trope in otaku-oriented media.[21] There are also little sister-themed cafés, indexing the fantasy earlier discussed. These connections are endless, and otaku respond to twodimensional characters and interactions as moe. Honda explains the result: ‘Let’s call it a world positioned on the border of the two-dimensional and three-dimensional. … A vague 2.5 dimensional space like a maid café is a place where the two-dimensional concepts and delusions lingering in my soul can easily be brought into the three-dimensional world’ (Honda 2005: 19). Association with the two-dimensional world, and lack of depth or access in the three-dimensional world, makes a maid moe.[22]

While in no way attempting to deny popular and vulgar articulations of maids, which exist just as abuses of the word moe do, at least in the beginning in Akihabara otaku did not go to maid cafés to ogle at maids so much as encounter two-dimensional ideals. The most famous maid in Japan, ‘hitomi,’ explains: ‘Our masters don’t look at us as friends, but rather as maids. And we don’t look at them as men, either. They are always masters in our eyes’ (Galbraith 2009: 134). The fantasy is kept alive by separating it from reality and setting it apart – not man and woman, but master and maid – and this allows a relationship to exist between but independent of the people involved, who might not match ideals or even be interested in each other. The appeal of the maid cannot purely be sexual: As many as 35 per cent of customers are women (Galbraith 2009). To draw in even more women, female staff at some cafés dress up as beautiful boys (dansou), and conversely men sometimes dress up women (josou) and become maids. While ostensibly performed as a service to female customers, men also respond to these ‘characters’ in the café space. The actual physical sex of the staff does not matter in these performances of fantasy ideals. This approaches the discourse on idols, or highly polished and produced media personalities, usually singers or pin-up models. Yamamoto Yutaka, a well-known moe anime director and idol fan, explains: ‘If you translate “idol” into Japanese, it is “image” (guuzou). Like an image of Christ. And when you say image, it means something that is not real. It is shrouded in lies. Communal worship of the image is what creates an idoru [sic]. An idoru is about remaining as close to the image in the mind of the believers as possible. I want [an] idoru to remain wrapped in lies, and I don’t care what the real person is doing’ (Galbraith 2009: 24).[23] What is moe, then, is not a response to the person so much as the representation of a two-dimensional character or fantasy ideal. For Yamamoto, the two-dimensional idol image and character is in fact the only appeal, existing separate and independent of corporeal form and physical actions. Similarly, maids exist as two-dimensional fantasy characters rather than eroticized three-dimensional women; this is characterization, which places the focus on the images projected on the body, as distinct from sexual objectification of the body.

Notes

[1] Moe (萌え), pronounced ‘moh-ay.’ It can be used as a noun (X ga moe, or ‘X is moe’) or a verb (X ni moeru, or ‘I burn for X’). It can further be used in a way similar to an adjective (X-moe, or ‘moe for X’) in that it describes something that inspires moe.

[2] Because otaku in this context enjoy playful use of language, including creating words or intentionally using incorrect Chinese characters (kanji), the emergence of moe is not far fetched. The characters under discussion were hybrids of the rorikon (Lolita Complex) a nd bishoujo (beautiful girl) genres, and the nuance of ‘budding’ seemed ideal to describe their premature beauty, another reason the moe pun stuck. However, the phenomenon is not entirely new. Attractive characters existed in even the earliest examples of modern manga from the 1940s and anime from the 1960s, and young female characters named “Moe” appeared in rorikon magazine Manga Burikko in the early 1980s (Ootsuka, interview with the author, October 2, 2009).

[3] For example, in June 2008, otaku produced an online video of Japan’s princess Akishino Mako. Drawings of the then 17-year-old girl flashed onscreen, scored by a trance-like music. The princess was an anime character, and viewers posted comments expressing ‘Mako-sama moe.’

[4] Despite parallels with Lawrence Grossberg and his work on the materiality of affect, I do not wish to invoke a discourse so connected with the conscious control of affect (i.e., meaning making, investment) (Grossberg 1997). A debate on the nature of affect is not my goal, but suffice it to say I find Massumi’s approach far more useful for the purposes of this paper.

[5] Aptly named Doku, a pun referencing both the users’ single status and poisonous character (Freedman 2009).

[6] Such a reaction to otaku was not possible a decade before, when such personalities were considered sociopaths, cultists and tribal aliens following the media coverage of the 1989 ‘otaku murderer’ Miyazaki Tsutomu (Kinsella 2000).

[7] This despite the fact that few otaku, if any, would actually say ‘moe’ when they are excited.

[8] By company You Can, in the category Group Involved in Promotion. That year, moe was used by a maid idol group associated with @home café in Akihabara. The media buzz surrounding Akihabara propelled the group and their buzzword to fame.

[9] Part of the larger US$3.5 billion annually spent by otaku.

[10] For example, at the Japan Pavilion of the 9th Venice Biennale of Architecture in 2004, Morikawa Kaichirou placed the word ‘moe’ alongside wabi and sabi, Japan’s distinguished aesthetics.

[11] The book, titled Guiding Your Friends Around Akihabara in English, describes moe as ‘the excitement young people feel about anime or comic characters, or pop idols.’

[12] Although Azuma never actually qualifies the term before his extensive use of it.

[13] In many ways, this reads like rejection of sociocultural norms. In 2005, Honda published Dempa Otoko, a manifesto about the ‘travesty’ of the didactic Densha Otoko narrative telling otaku that they must mature into socialized, adult male roles and find mates. Honda’s book sold 33,000 copies in three months, and fans planted signs in Akihabara reading, ‘Real Otaku Don’t Desire Real Women’ (Freedman 2009).

[14] For a full discussion of the collapse of work, home and school in postmillennial Japan, see Yoda and Harootunian 2006.

[15] In fall 2008, an online petition asking the government to recognize marriage to two-dimensional characters gathered 2,443 signatures in two weeks.

[16] Or gyarugee (gal games) or bishoujo geemu (beautiful girl games), a huge industry in Japan that blurs the line between direct, mediated and purely machine contact. These games range from chatting to overt pornography, but in the most basic iteration the player tries to navigate relationships with beautiful girls. The most representative is Tokimeki Memorial from 1994.

[35] A full version of this argument appears in my article in progress, ‘Fujoshi: “Moe” Fantasy and Transgressive Intimacy among Young Female Fans.’

Excerpt from

Making It Real: Fiction, Desire, and the Queerness of the Beautiful Fighting Girl

by J. Keith Vincent, written as the translator’s introduction to Beautiful Fighting Girl by Tamaki Saitou

Defining the Otaku

Who exactly are the otaku? The term refers on the most basic level to passionate fans of anime, manga, and computer games. They are known for their facility with computer technology and for their encyclopedic, even fetishistic, knowledge of particular strains of visual culture.[10] Most commentators agree that the otaku emerge historically as a new sociological type sometime in the 1970s in the vacuum left by a hegemonic mainstream culture and the sub- and countercultures that opposed it. Defined more by their tastes than their actions or convictions, the otaku are the precocious children of postmodern consumerist society.

A more precise definition than that would be impossible because the otaku have become such a highly contested (and therefore fascinating) category. As Melek Ortabasi suggests, the figure of the male otaku is akin to the prewar moga, or “modern girl,” in that he is both a lived identity and a media creation that crystallizes all sorts of social anxieties.[11] In the case of the otaku, these are about gender, sexuality, national identity, and normative development, all highly charged issues that cause the discourse about them to shift wildly back and forth between shame and pride.

First the pride. Okada Toshio, the self- proclaimed “Otaku King” who emerged in the 1990s as the chief spokesman for the otaku and proponent of so-called otakuology, has put forward the most complimentary definition of the otaku. This is to be expected, since he is himself what Saitou calls an “elite otaku.” As a founder of the hugely successful anime studio Gainax and the cocreator of some of the most important anime in the otaku canon, Okada has every reason to be proud of otaku culture.[12] He defines the otaku as, among other things, “a new human type born in the twentieth century... with an extremely evolved visual sensibility.”[13] He traces their history back to early fans of televised anime who prided themselves on being able to distinguish the pictorial styles of individual producers of anime images. The more subtle the distinctions, the more pleasure it gave the otaku to make them, and they took pride in being something more than passive consumers of mass-produced entertainment, capable of spotting value and difference where others saw only monotony. As connoisseurs, Okada claimed, they traced their roots to premodern arbiters of taste like tea ceremony founder Sen no Rikyu (1522–1591), who was famous for his ability to proclaim a broken teacup more valuable than a whole one.[14]

Other proponents of otaku culture, such as Outsuka Eiji and Morikawa Kaichirou , have written of the extraordinary power of otaku taste to create communities, to transform urban space, to upend capitalist relations of production and consumption, and to challenge American cultural hegemony.[15] These claims, which Thomas Lamarre has collectively labeled the “Gainax discourse,” after Okada’s company, shade very quickly into utopian thinking, evoking “the distributive visual field of anime to make claims for the end of all hierarchies—those of history, of modernity, and of the subject.”[16] This is heady stuff, and there are many elements of otaku culture that are in fact quite radical. As Lamarre also argues, however, the emphasis on historical rupture and Japanese cultural uniqueness in many of these texts keeps what could have been a theory of what is truly new about otaku culture from developing beyond the level of a discourse on otaku, and Japanese, identity. Otaku pride, moreover, can take rather extreme forms. Here, for example, is Okada in 1996: “At this moment the country of Japan could disappear and world culture wouldn’t suffer a bit. The only exception to this is ‘otaku culture.’ [Japanese] Anime, manga, and computer games are sought after by people all over the world.”[17]

Such hyperbolic, and often narcissistic, celebrations of otaku culture are perhaps not so surprising, however, insofar as they come in reaction to successive waves of fear and loathing from mainstream Japanese society, for whom the otaku are anything but exemplary postmodern subjects or heirs of the best of Japanese culture.

From the perspective of mainstream Japanese culture, the otaku have a reputation for being undersocialized, unhealthily obsessive, and unable to distinguish between fiction and reality. When Miyazaki Tsutomu, who later turned out to be a fan of pornographic “rorikon” anime, was found to have murdered and partially cannibalized four little girls in 1989, the idea of the otaku as pedophile and psychopath was cemented in the public imagination.[18] As a result, many find it hard to accept that the otaku’s passion for the beautiful fighting girl is limited to the realm of fiction and fantasy and does not translate into actual pedophilia. Sensationalizing news accounts of otaku who prefer so-called 2-D love over the real thing, moreover, are taken at face value as evidence of a pathetic developmental failure, and the challenge posed by otaku culture to the normative trajectory from childhood into adulthood can seem like a rejection of the future itself.[19] Even Morikawa, who writes quite sympathetically about the otaku in general, insists that they are characterized by what he calls “an inclination toward failure” (dame shikou).[20]

Beautiful Fighting Girl intervenes in this highly polarized discourse to put the otaku back on a continuum with the rest of humanity. For Saitou, the otaku have a great deal to teach us about how to survive and flourish in our media-saturated environment. They are distinguished not by their inability to distinguish reality from fiction but by their ability to take pleasure in multiple levels of fictionality and to recognize that everyday reality itself is a kind of fiction. In an essay published just after Beautiful Fighting Girl, he wrote:

Otaku seek value in fictionality itself, but they are also extremely sensitive to different levels of fictionality. From within our increasingly mediatized environment, it is already difficult to draw a clear distinction between reality and fiction. It is no longer a matter of deciding whether we are seeing one or the other, but of judging which level of fiction something represents.[21]

The otaku’s attitude toward fiction accords very well with Jacques Lacan’s understanding of the imaginary nature of experiential reality and can be a healthy adaptive strategy as well. Unlike obsessive fans who abandon themselves wantonly to their passions, the otaku maintain a detached and ironic perspective toward the objects of their fascination. Unlike their close relatives the maniacs, who covet objects that take material form (such as stamps or coins), the otaku are drawn to entirely fictional objects (such as anime characters) that they seek to “possess” by fictionalizing them further in narratives of their own creation. But the most important characteristic of Saitou’s otaku is their ability to eroticize fictional characters. It is the otaku’s sexuality, then, that really distinguishes them for Saitou. He explores it using Lacanian psychoanalysis, which may not be to everyone’s taste, but he does so without the slightest trace of moralizing judgement, which is refreshing and long overdue.

Saitou’s focus on the otaku’s sexuality has provoked quite a bit of criticism, most famously from the media critic Azuma Hiroki, as I discuss later. But it is also Saitou’s most important contribution to our understanding of otaku culture. His Lacanian approach is also particularly well suited to analyzing otaku and the beautiful fighting girl for two interrelated reasons. First, it offers powerful tools with which to understand how the proliferation of new media forms has come to trouble the distinction between fiction and reality. Second, it makes it possible to describe otaku sexuality in a language that does not pathologize and acknowledges their ability to derive pleasure from fictional images in the fundamentally perverse imaginary space of anime and manga.

Lacan as Media Theorist

How does Lacanian theory understand the difference between “reality” and “fiction”? As is well known, Lacan posits a tripartite model for understanding human subjectivity. The Symbolic is the realm of language and the law; the Imaginary is the realm of images and appearances; and the Real is the unmediated and hence unimaginable “raw material” of reality, the perception of which would be too traumatic for us to bear. In Saitou’s account of Lacan, our experience of what we know as reality takes place only in the Imaginary. It is also in the Imaginary that we experience everything else—including fiction and other images and perceptions—all mediated and regulated by Symbolic forms such as language and law. As Saitou writes, “It is here [in the Imaginary] that ‘meaning’ and ‘experiences’ are possible.” For this reason, Saitou makes it clear from the outset that his discussion of the otaku focuses exclusively on the realm of the Imaginary. This is because, in Lacanian theory—as in the otaku’s world—reality (unlike the Real) is understood as an imaginary phenomenon. Imaginary objects exist right alongside our perception of “everyday reality,” and to the extent that we are able to cathect them, or invest them with libido, they are no less “real” in terms of their psychic effect on us. The only thing that distinguishes imaginary forms and constructs from what we understand in commonsense terms as everyday reality, Saitou writes, is our consciousness of them as being mediated in some way. Everyday reality, conversely, is “nothing more than a set of experiences that emerge from a consciousness of not being mediated.” From Saitou’s Lacanian perspective, then, there is no ontological distinction between “reality” and “fiction.” It is only a matter of the perception of the absence or presence of mediation.

Lacan’s theory of the imaginary nature of reality, then, is itself a theory of media that turns out to be very useful for understanding and coping with our hypermediated world. The proliferation of modern media forms has led to an unprecedented expansion of the realm of the Imaginary. With television, newspapers, film, anime, manga, and—of course, the Internet—we now have access to a virtually unlimited store of images and ideas, all competing with “everyday reality” for our attention. Some of us experience this as enriching and exciting, while others find it threatening or overwhelming. As the realm of the Imaginary expands because of the proliferation of media, some of us may feel that the ability of the Symbolic to structure and unify the Imaginary is threatened. Since the (always illusory) unity of the subject is maintained by what Lacan calls the phallus, this threat may even be experienced as a kind of castration anxiety. The panicked desire to reinstate the Symbolic in the face of an onslaught of images that threaten to undermine the distinction between the real and the fictional can thus take the form of an anxiety over sexual norms and gender conformity. This is one reason that Saitou insists that sexuality is key to understanding both otaku culture and the reactions it provokes in mainstream society.

From this perspective, another possible definition of the otaku would be: those who take the most pleasure in and are most knowledgeable about this expansion of the Imaginary. While the rest of us may feel overwhelmed and awash in a flood of images and information, the otaku revel in it. As mentioned earlier, Saitou argues that the litmus test for a real otaku is whether they can be genuinely sexually excited by a drawn image. He writes

When a person is sexually excited by the image of a woman in an anime, they may be taken aback at first, but they are already infected by the otaku bug. This is the crucial dividing point. How is it possible for a drawing of a woman to become a sexual object?

“What is it about this impossible object, this woman that I cannot even touch, that could possibly attract me?” This sort of question reverberates in the back of the otaku’s mind. A kind of analytical perspective on his or her own sexuality yields not an answer to this question but rather a determination of the fictionality and the communal nature of sex itself. “Sex” is broken down within the framework of fiction and then put back together again.

In this respect one could say that the otaku undergoes hystericization: the otaku’s acts of narrative take the form of eternally unanswerable questions posed toward his or her own sexuality. And the narratives of hysterics cannot help but induce from us all manner of interpretations. This is of course what has led me to the present analysis.

This explosion of “acts of narrative” instigated by the otaku’s hysteria leads to the obsessive replication of the beautiful fighting girl theme as discussed earlier in the case of Miyazaki Hayao. Her “fighting” is the perverse expression of the projected and inverted hysteria of the male otaku whose fantasy she embodies. The hysteria is “inverted” because, while the hysteric expresses the trauma of sexuality by somaticizing it, the beautiful fighting girl seems to have experienced no trauma at all; her battles are not about revenge or even about justice. They are an expression of an unrepressed and deinstrumentalized sexuality. She fights for no discernible reason. She is the embodiment of the phallus and of pure jouissance, as it can exist only in the space of fiction and of infantile polymorphous perversion. As an embodiment of the Lacanian phallus, she offers a way out of the oedipal circuits of desire and lack, rivalry and revenge. She is the emblem of the otaku’s “perversion.”

Otaku Perversion

It should be emphasized here that “perversion” in Lacanian psychoanalysis is not an insult. It is a structural characteristic of all human sexuality, related to the mechanism of disavowal. As Bruce Fink writes, “It is evidence of the functioning of this mechanism— not this or that sexual behavior in itself—that leads the analyst to diagnose someone as perverse. Thus, in psychoanalysis ‘perversion’ is not a derogatory term, used to stigmatize people for engaging in sexual behaviors different from the norm.”[22]

What is it that the otaku disavow? For Saitou this would of course be the fictionality of the beautiful fighting girl and, by extension, the ontological distinction between fiction and reality more generally. While our normative understanding of sexuality insists that it must have an object in the real world (preferably of the opposite sex) and that anything else can only be a “transitional” object, Saitou’s otaku recognize that, to the extent that the “real world” is itself part of the Imaginary, there is no intrinsic difference between desiring a drawn or animated image and desiring an actual human being.[23] The otaku’s ability to eroticize fictional objects, moreover, perfectly exemplifies Lacan’s understanding of all sexuality as a fantasy and an illusion. If the proliferation of new media and the emergence of the Internet have meant that the “virtual” world has started to become just as meaningful as the “real” one, the otaku are there to tell us that this is nothing new.[24] Sometimes we do not want to hear this. And this, Saitou suggests, is a major source of the visceral contempt and derision with which the otaku are often treated.[25]

If society tends to repress the phantasmic aspects of sexuality, the otaku celebrate it. Their ability to eroticize imaginary objects, Saitou argues, has made them better equipped to cope in a mediasaturated postmodern society in which the distinction between fiction and reality is increasingly problematic. In a world in which the Imaginary threatens to overwhelm the Symbolic,[26] along with the phallus that serves as its guarantee, the fantasy of the “phallic girl” is the otaku’s way of holding on to a sense of reality. His perversion is a kind of ontological anchor; it is his salvation—and it could be ours as well. “For the world to be real,” Saitou writes, “it must be sufficiently electrified by desire. A world not given depth by desire, no matter how exactingly it is drawn, will always be flat and impersonal, like a backdrop in the theater. But once that world takes on a sexual charge, it will attain a level of reality, no matter how shoddily it is drawn.”

Saitou’s positive view of otaku sexuality has the enormous merit of making it intellectually interesting and heading off the stupefying forces of stigmatization. Its value is all the greater in a cultural context in which many want nothing more than to “castrate” the otaku by inserting them into a developmental narrative and insisting that the objects of their affection are merely transitional ones that they must eventually outgrow. Such was the message, for example, of Train Man (Densha otoko), the hugely popular media phenomenon about an otaku who inadvertently saves a girl from a harasser on a train and ends up discovering true love, thereby “graduating” from his otaku identity.[27] Although the Train Man phenomenon postdates the publication of Beautiful Fighting Girl, Saitou has been very outspoken in his opposition to what he calls “the same old calls for otaku just to ‘accept reality and grow up’ and ‘acknowledge the gap between the real and the ideal.’” For Saitou, the perversion of the otaku, their insistence on holding on to their transitional object forever, is precisely the lesson that they have to teach us.

It is important to understand that this is not the same as saying that the fictional object is the only object the otaku can love, nor does it mean that he or she cannot tell the difference between real and imaginary objects of desire. Being an otaku says nothing about one’s ability to love another human being, and one’s taste in fictional sex is not necessarily predictive of the kind of sex one actually wants to have. Saitou would no doubt agree with the queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, who included in a long and wonderfully nonnormative list of all the ways in which people’s sexuality can be different the following item: “Many people have their richest mental/emotional involvement with sexual acts that they don’t do, or even don’t want to do.”[28] Saitou argues that their ability to inhabit “multiple orientations,” a sort of nonpathological form of dissociative personality disorder, means that otaku are perfectly capable of conducting a richly perverse fantasy life while maintaining an utterly “normal” and pedestrian sex life in their day-to-day lives. Which form of sexuality represents their “true nature,” however, is a matter of indifference to Saitou. As their fantasies lead them to proliferate multiple fictional worlds, the effect is to dehierarchize the relation between fantasy and reality.

It is important to remember that Saitou makes this argument about the otaku’s “normality” partly to defend the otaku against those who revile them as perverts and pedophiles, which in some cases perhaps leads him to overstate his case. In his recent book The Anime Machine, Thomas Lamarre is extremely critical of Saitou’s eagerness to assert the otaku’s normality, characterizing his “agenda” as saying, “let your fantasies run wild as long as they lead you back to bed with your socially legitimate partner.”[29] While Lamarre’s critique is characteristically brilliant in many ways,[30] this claim strikes me as a serious mischaracterization of Saitou’s position. Saito ̄ may describe the real- life sexuality of the otaku he knows as tending toward the heterosexual and the vanilla, but he never prescribes that it be so. For Saitou, the reality-producing charge of the beautiful fighting girl sparks across the gap between the otaku’s actual heterosexual “wholesomeness” and the polymorphous perversity of their fantasies, but neither pole is privileged or pathologized. I have addressed Lamarre’s critique here because I want to stress that, contrary to the impression he gives, there is much in Saitou’s book that students of sexuality and queer theory will find both useful and exciting. Cast as unnatural and perverse, and devalued because unrelated to reproduction, there is something decidedly queer about otaku sexuality, and Saitou’s book offers a truly loving account of it. In their ability to eroticize fiction, Saitou’s otaku decouple sexual desire from social identities and naturalized bodies in ways that queer theorists will find fascinating.

His understanding of fictionality as a multilayered phenomenon rather than simply “the opposite of reality,” and therefore trivial or immature, is a useful way to get beyond binary thinking and normative theories of development. It is also a way to understand not just what fiction is but how it works in and on the world. In his critique of Saitou mentioned earlier, Lamarre describes Saitou’s work as “a quasi-Jungian apologia for the force of creative fantasy.”[31] But readers will find that there is much more to Saitou’s analysis of fiction and sexuality than the sort of mystic humanism this implies. The wellspring of the otaku’s multiple fictional worlds lies not in the depths of the human soul but in the abyss of the Lacanian Real. As Saitou writes, “What I call the ‘plurality of (imaginary) reality’ (souzouteki genjitsu no fukusuusei) has its origin and derives its potential from the positing of the Real. Without that it is nothing more than a variant of the idea that fantasy is all that exists.” Far from the mindless relativism of “the idea that fantasy is all that exists” or a simplistic celebration of creativity, Saitou’s work takes fiction seriously. As such it helps us understand how, in Michael Moon’s words, “play and pleasure—which in our society frequently get relegated to the domain of an ostensibly ‘temporary escape from reality’—can demand engagement with some of our own and other people’s most disturbing feelings, memories, and desires, and can also invite and withstand rigorous analysis.”[32]

In addition to Sedgwick and Moon, there is one more foundational queer theorist whose work seems relevant to Saitou’s. While Lamarre may be right to take issue with Saitou’s overemphasis on the otaku’s “normal” heterosexuality in real life, Saitou still gets credit for battling what Judith Butler famously argued was a much more insidious form of heteronormativity. She called it “melancholic heterosexuality” and argued that it formed the psychic basis for naturalizing the body itself. “The conflation of desire with the real—” she argued in Gender Trouble, “that is, the belief that it is parts of the body, the ‘literal’ penis, the ‘literal’ vagina, which cause pleasure and desire—is precisely the kind of literalizing fantasy characteristic of the syndrome of melancholic heterosexuality.”[33] Melancholic heterosexuality, for Butler, is the result of a taboo against homosexuality that precedes even the heterosexual incest taboo and plays a key role in forming our sense of inhabiting sexed bodies. She argues that the oedipal injunction against incestuous desire for the opposite- sex parent is preceded by a taboo against desiring the same-sex parent. The force of this taboo is such that the loss itself cannot be acknowledged, and this unmourned loss of the same-sex parent as an object of desire causes the subject to introject and identify with that object in place of desiring it.

This identification, Butler suggests, sets the same-sex parent up inside the subject as the source of the felt “reality” of our sexed bodies. In her words, “The disavowed homosexuality at the base of melancholic heterosexuality reemerges as the self-evident anatomical facticity of sex.”[34] This suggests that insofar as resistance to the otaku’s fictionalization of desire typically manifests itself in the form of an insistence on the material facticity of bodies (i.e., “people need a good slap in the face!”),[35] that resistance may itself be rooted in one of the psychic foundations of heteronormativity. Although Saitou does not make this argument himself, his articulate defense of the otaku against those who insist that desire must be rooted in real bodies suggests the critically queer potential of otaku sexuality.

Otaku Talk

by Toshio Okada & Kaichiro Morikawa; moderated by Takashi Murakami, translated & annotated by Reiko Tomii

Takashi Murakami: Okada-san, Morikawa-san, thank you for coming. Our topic today is the culture of otaku[24] [literally, “your home”]. After Japan experienced defeat in World War II, it gave birth to a distinctive phenomenon, which has gradually degenerated into a uniquely Japanese culture. Both of you are at the very center of this otaku culture.

Let us begin with a big topic, the definition of otaku. Okada-san, please start us off.

Toshio Okada: Well, a few years ago, I declared, I quit otaku studies, because I thought there were no longer any otaku to speak of.

Back then [during the 1980s and early 1990s], there were a hundred thousand, or even one million people who were pure otaku—100-proof otaku, if you will. Now, we have close to ten million otaku, but they are no more than 10- or 20-proof otaku. Of course, some otaku are still very otaku, perhaps 80 or 90 proof. Still, we can’t call the rest of them faux otaku. The otaku mentality and otaku tastes are so widespread and diverse today that otaku no longer form what you might call a “tribe”. [zoku –Editor]

Kaichiro Morikawa: Okada-san’s definition of otaku sounds positive, as if they’re quite respectable.

In my opinion, otaku are people with a certain disposition toward being dame[25] [“no good” or “hopeless”]. Mind you, I don’t use this word negatively here.

To some extent, people born in the 1960s are saddled with the baggage of an “anti-establishment vision.” In contrast, otaku, especially in the first generation, have increasingly shed this antiestablishment sensibility.

It’s important to understand that although otaku flaunt their dame-orientation—an orientation toward things that are no good— it’s not an anti-establishment strategy. This is where otaku culture differs from counterculture and subculture.

TM: Indeed, otaku are somewhat different from the mainstream. They have a unique otaku perspective, even on natural disasters. For example, the reaction of Kaiyodo’s[26] executive, Miyawaki Shuichi, to witnessing the destruction of the Great Hanshin Earthquake[27] in 1995 was, “I know it’s insensitive to say this [after such terrible disaster], but I think Gamera[28] got it wrong.” You know, the aftermath of a real earthquake was used as a criterion in otaku criticism.

TO: At the time of the earthquake, I raced to Kobe from Osaka, hopping on whatever trains were still running, taking lots of pictures. I agree, Gamera got it wrong. To create a realistic effect of destruction, you need to drape thin, gray noodles over a miniature set of rubble. Otherwise, you can’t even approach the reality of twisted, buckled steel frames. It was like, “If you call yourself a monster-filmmaker, get here now!”

When Mt. Mihara[29] erupted in 1986, the production team of the 1984 Godzilla film went there to see it.[30] They were true filmmakers.

Wabi-Sabi-Moe

Takashi Murakami: Morikawa-san will present an exhibition about otaku and moe[31] [literally, bursting into bud] at the architecture bienniale in Venice in 2004.[32] Your association of otaku with architecture is unique. Please tell us about it.

Toshio Okada: I was most impressed by your phrase, wabi-sabimoe, in the exhibition thesis.

Moe is not an easy concept to comprehend, but when you linked the three ideas linguistically, it made a lot more sense.

Those who are unfamiliar with the concepts of wabi and sabi [meaning “the beauty and elegance of modest simplicity”] must surely wonder what’s appealing about feigning poverty. Likewise, with moe, until you get the concept, I’m sure people question the origins of this seeming obsession with beautiful little girls, bishojo.[33] But once you get it, you start to feel like moe might become a megaconcept, exportable like wabi and sabi.

Kaichiro Morikawa: The truth is, I made up that phrase to pitch the show. But suddenly it was a headline in the Yomiuri newspaper.

Toshio Okada: That’s awesome. The fact that it became a headline means everybody can understand it.

KM: It’s a play on something the architect Arata Isozaki[34] did in his exhibition, Ma,[35] in Paris in 1978. He provided logical English explanations for such traditional concepts as wabi and suki [meaning “sophisticated tastes”] on exhibition panels.

The key Japanese words—such as wabi, sabi, and suki—were inscribed in classical calligraphy and accompanied by lengthy English explanations printed in Gothic fonts.

I decided I’d do the same with moe.

There is a huge gap between people who know the word moe and those who don’t. Every otaku person knows moe. For them, it’s so basic. But it’s not like all young people know the term. While at graduate school, I asked my colleagues about moe but almost none of them knew it.

It dawned on me that most mainstream people just don’t know it.

TM: That disparity is really intriguing.

KM: It clearly corresponds with another gap between those who know that Akihabara[36] is now an otaku town and those who don’t.

Those who do know couldn’t care less that others are finally catching up, while those who don’t know Akihabara today still think of Akihabara the way it’s been portrayed in commercials for household appliance stores. This gap reflects the state of Japanese culture and society today.

To those who are unfamiliar with moe, I only half-jokingly explain, “In the past, we introduced foreigners to such indigenous Japanese aesthetic concepts as wabi and suki. These days, people abroad want to know all about moe.” A lot of people respond, “Oh, is that so…”

TM: Morikawa-san, I’d like to ask you, then: What prompted otaku to gather in Akihabara?

KM: Otaku are self-conscious about being condescended to, when they go to fashionable places like Shibuya.[37]

But they feel safe in Akihabara, because they know they’ll be surrounded by people who share their quirks and tastes.

Over time, the focus of otaku taste shifted from science fiction to anime to eroge[38] [erotic games], as young boys who once embraced the bright future promised by science saw this future gradually eroded by the increasingly grim reality around them. I think they needed an alternative.

TO: I think kawaii[39] [literally, “cute”] is the concept Murakami-san exported throughout the world.

Granted, Murakami-san’s kawaii is alarming enough. But I wonder why I was further alarmed by Morikawa-san’s formulation of wabi-sabi-moe. In a previous conversation we had for a magazine article, you said, Otaku is about the vector toward dame.

As a way of expanding on that, when otaku choose this orientation, they head in the direction of becoming more and more pathetic. At the same time, they enjoy watching themselves becoming increasingly unacceptable. If you think about it, in a very, very loose sense, this is wabi and sabi.

I suspect this orientation is inherent in Japanese aesthetics. If you look for a Western equivalent, it would be Decadence, or the Baroque, though theirs is a tendency toward excessive decorativeness. I imagine such people think of themselves not in terms of “See what we’ve done. We’re amazing,” but more like, “See what we’ve done! How pathetic we are!”

TM: I have said this many times, but I am a “derailed” otaku.

Neither of your situations applies to me.

When I am talking to Okada-san, I remember feeling like I could never keep up with the distinctive climate of the otaku world.

So, I now want to explore the real reasons why I escaped being an otaku.

TO: Probably because otaku standards were so high when you tried to join them. Besides, I bet you wanted to go right to the heart of otaku, didn’t you?

The closer you tried to get to the heart of the otaku world, the farther you had to go.

TM: That’s not just true with otaku, though. The world of contemporary art is exactly the same. If you can’t discuss its history, you won’t be taken seriously and you won’t be accepted on their turf. I kept being reminded of this while listening to you two talk.

TO: In other words, just as you once had to know the history of contemporary art, now you have to understand moe, right?

Otaku vs. Mania

Takashi Murakami: This may be a frequent question, but what is the difference between otaku and mania[40]?

Kaichiro Morikawa: In otaku studies, we often argued about this distinction. Generally speaking, three differences have been articulated.

First of all, mania are “obsessives” who are socially well adjusted. They hold down jobs and love their hobbies. In contrast, otaku are socially inept. Their obsessions are self-indulgent. This point is raised mainly by the self-proclaimed mania, critical of otaku.

The second point concerns what they love. Mania tend to be obsessed with, for example, cameras and railroads, which have some sort of materiality (jittai), while otaku tend to focus on virtual things such as manga and anime. In other words, the objects of their obsessions are different.

The third point relates to the second one. A mania tends to concentrate on a single subject—say, railroads—whereas an otaku has a broader range of interests, which may encompass “figures,”[41] manga, and anime.

Taken together, I would say—although Okada-san may disagree with me—that someone who is obsessive about anime likes anime despite the fact that it’s no good, dame. That’s mania. But otaku love anime because it’s no good.

Toshio Okada: Mania is an analogue of otaku. Obsessives are adults who enjoy their hobbies, while otaku don’t want to grow up, although financially, they are adults. These days, you’re not welcome in Akihabara if you aren’t into moe.

I was already a science-fiction mania when otaku culture kicked in. I can understand it, but I can neither become an otaku myself nor understand moe. [Laughs]

TM: And I’m nowhere near Okada-san’s level. I failed to become an otaku. Period. [Laughs]

TO: I believe otaku culture has already lost its power. What you find in Akihabara today is only sexual desire. They all go to Akihabara, which is overflowing with things that offer convenient gratification of sexual desire, made possible by the power of technology and the media.

KM: But I think the sexual desire in Akihabara is different from that in Kabuki-cho.[42]

TO: Kabuki-cho is about physical sex.

Because the heart of otaku culture shuns the physical, it has renamed seiyoku [sexual desire] as moe.

Sexual fantasies are becoming more and more virtual and “virtual sexuality” proliferates in Akihabara.

KM: Many otaku think they like what they like even though they know these things are objectionable, when in fact they like them precisely because they are objectionable. This gap between their own perception and reality has made it difficult to distinguish otaku from mania.

If we define otaku through this orientation toward the unacceptable, it’s easy to explain the three differences between otaku and mania. Because if you like something that’s socially unacceptable, you will appear antisocial.

Another consideration is that material things are considered superior to the immaterial. So if you are interested in the debased, you naturally gravitate toward the virtual.

In addition, otaku don’t just purely love anime or manga, they choose to love these things in part as a means of making themselves unacceptable. That is why their interests are so broad.

This dame-orientation is evidenced by the history of otaku favorites. Up until the 1980s, people who watched anime—any kind of anime, be it Hayao Miyazaki[43] or Mamoru Oshii[44] or whatever—were all considered otaku. Today, Japanese anime is so accomplished that one film even won an Academy Award. As a result, grown-ups can safely watch, say, Miyazaki’s anime without being despised as otaku.

The upshot of this is, as soon as anime and games earned respectability in society, otaku created more repugnant genres, such as bishojo games[45] and moe anime,[46] and moved on to them.

TM: Morikawa-san, you’re saying the essence of otaku is their orientation toward dame, the unacceptable.

KM: Yes, yes. But dame does not define something as bad or low quality. It’s the self-indulgent fixation of otaku on certain things that is socially unacceptable.

TO: I totally disagree. Morikawa-san and I have two vastly different conceptions of who are the core tribe of otaku.

Morikawa-san, your otaku are “urban-centric”; they are the hopeless otaku who roam about Akihabara. That’s why you say otaku are dame-oriented. You have to remember that only about fifty thousand people buy Weekly Dearest My Brother.[47] It’s wrong to define them as core otaku.

In my experience, otaku like science fiction and anime not because these things are worthless, but because they are good. Otaku are attracted by things of high quality.

Some otaku obsessions become hits, others don’t. But according to Morikawa-san’s definition, the question of “quality” becomes irrelevant in otaku culture.

But what’s survived in otaku culture hasn’t become unacceptable. It’s survived the competition because its quality has been recognized.

Once something like a bishojo game achieves a certain level of quality, you buy it even if you don’t actually like bishojo games. I feel otaku are tough customers who demand high standards. As a producer of video and manga magazines, I was keenly aware of their standards and thought, “They make me work really hard because they won’t fall for cheap tricks.”

Generational Debate

Takashi Murakami: I have to confess, I don’t think I fully understand the moe sensibility.

Toshio Okada: The moe generation is mostly made of otaku 35 or younger.

I myself belong to the previous otaku generation, so frankly I don’t understand moe.