Robert Audi

Epistemology

A Contemporary Introduction to the Theory of Knowledge

Praise for the second edition:

Routledge Contemporary Introductions to Philosophy

Acknowledgments to the first edition

Acknowledgments to the second edition

Acknowledgments to the third edition

A sketch of the sources and nature of belief, justification, and knowledge

Perception, belief, and justification

Justification as process, as status, and as property

Memory, introspection, and self-consciousness

Reason and rational reflection

Basic sources of belief, justification, and knowledge

Three kinds of grounds of belief

Part One: Sources of justification, knowledge, and truth

The elements and basic kinds of perception

Perception, conception, and belief

Propositional and objectual perception

Perception as a source of potential beliefs

Simple, objectual, and propositional perception

The informational character of perception

Perceptual justification and perceptual knowledge

Seeing as and perceptual grounds of justification

Seeing as a ground of perceptual knowledge

Some commonsense views of perception

Perception as a causal relation and its four main elements

Sense-datum theories of perception

The argument from hallucination

Sense-datum theory as an indirect, representative realism

Appraisal of the sense-datum approach

Adverbial theories of perception

Adverbial and sense-datum theories of sensory experience

A sense-datum version of phenomenalism

Indirect seeing and delayed perception

The causal basis of memory beliefs

The representative theory of memory

The phenomenalist conception of memory

The adverbial conception of memory

Remembering, recalling, and imaging

Remembering, imaging, and recognition

The epistemological centrality of memory

Remembering, knowing, and being justified

Memorial justification and memorial knowledge

Memory as a retentional and generative source

Two basic kinds of mental properties

Introspection and inward vision

Some theories of introspective consciousness

Realism about the objects of introspection

An adverbial view of introspected objects

The analogy between introspection and ordinary perception

Introspective beliefs, beliefs about introspectables, and fallibility

Consciousness and privileged access

Infallibility, omniscience, and privileged access

Difficulties for the thesis of privileged access

The possibility of scientific grounds for rejecting privileged access

Introspective consciousness as a source of justification and knowledge

The range of introspective knowledge and justification

The defeasibility of introspective justification

Consciousness as a basic source

The classical view of the truths of reason

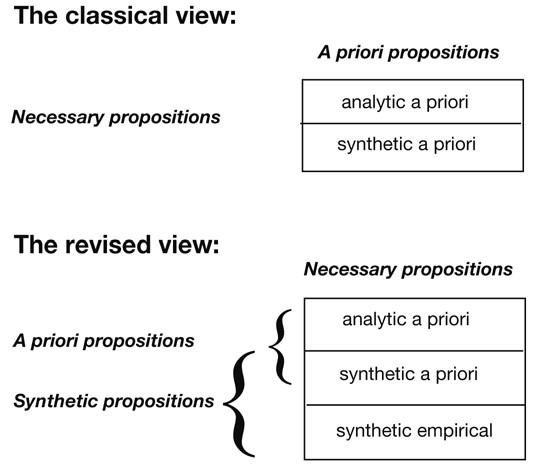

The analytic, the a priori, and the synthetic

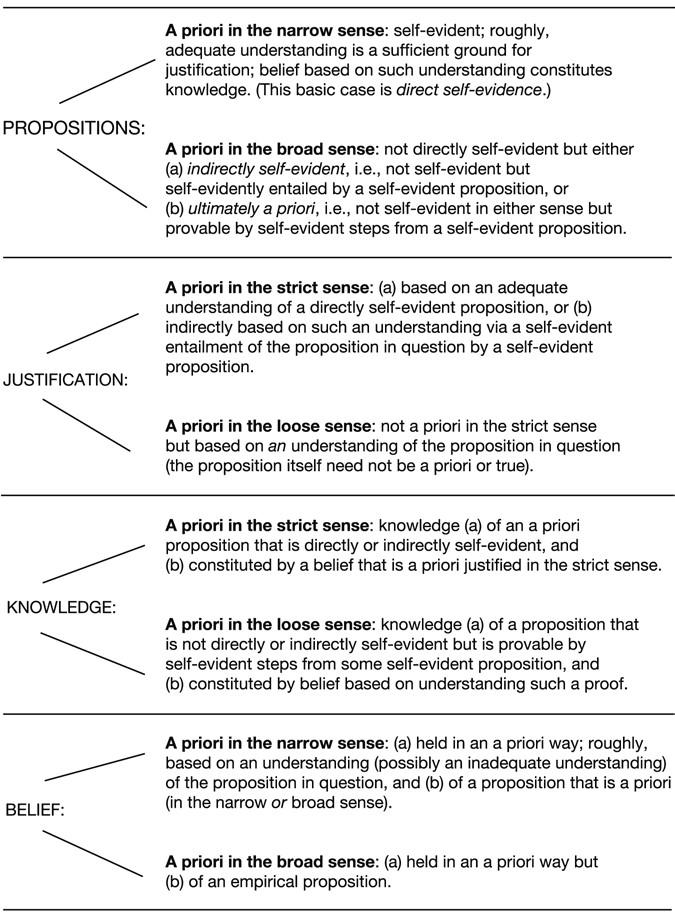

Three types of a priori propositions

Analytic truth, concept acquisition, and necessity

The empiricist view of the truths of reason

Empiricism and the genesis and confirmation of arithmetic beliefs

Empiricism and logical and analytic truths

The conventionalist view of the truths of reason

Truth by definition and truth by virtue of meaning

Knowledge through definitions versus truth by definition

Conventions as grounds for interpretation

Some difficulties and strengths of the classical view

Meaning change and falsification

The possibility of empirical necessary truth

Essential and necessary truths

Necessity, apriority, and provability

Reason, experience, and a priori justification

Loose and strict senses of ‘a priori justification’ and ‘a priori knowledge’

The power of reason and the possibility of indefeasible justification

The nature of testimony: formal and informal

The inferentialist view of testimony

Inferential grounds versus constraints on belief-formation

The direct source view of testimony

Testimony as a source of basic belief

Knowledge and justification as products of testimony

The twofold epistemic dependence of testimony

The indispensability of testimonial grounds

Conceptual versus propositional learning

Testimony as a primeval source of knowledge and justification

Non-testimonial support for testimony-based beliefs

Part Two: The structure and growth of justification and knowledge

8 Inference and the extension of knowledge

The process, content, and structure of inference

Two related senses of ‘inference’

Reasoned belief and belief for a reason

Two ways beliefs may be inferential

The basing relation: direct and indirect belief

Inference and the growth of knowledge

Confirmatory versus generative inferences

Inference as a dependent source of justification and knowledge

Inference as an extender of justification and knowledge

Source conditions and transmission conditions for inferential knowledge and justification

Deductive and inductive inference

Subsumptive and analogical inference

The inferential transmission of justification and knowledge

Inductive transmission and probabilistic inference

Some inferential transmission principles

Deductive transmission of justification and knowledge

Degrees and kinds of deductive transmission

Memorial preservation of inferential justification and inferential knowledge

9 The architecture of knowledge

Inferential chains and the structure of belief

Epistemic chains terminating in belief not constituting knowledge

Epistemic chains terminating in knowledge

The epistemic regress argument

Foundationalism and coherentism

A coherentist response to the regress argument

Coherence as an internal relation among cognitions

Coherence, reason, and experience

Coherence and the mutually explanatory

Epistemological versus conceptual coherentism

Coherence, incoherence, and defeasibility

Positive and negative epistemic dependence

Coherence and second-order justification

The process versus the property of justification

Beliefs, dispositions to believe, and grounds of belief

Justification, knowledge, and artificially created coherence

The role of coherence in moderate foundationalism

Moderate foundationalism and the charge of dogmatism

Part Three: The nature and scope of justification and knowledge

Knowledge and justified true belief

Knowledge conceived as the right kind of justified true belief

Dependence on falsehood as an epistemic defeater of justification

Knowing and knowing for certain

Naturalistic accounts of the concept of knowledge

Knowledge as appropriately caused true belief

Knowledge as reliably grounded true belief

Reliable grounding and a priori knowledge

Problems for reliability theories

Reliability, relevant alternatives, and luck

Relevant alternatives and epistemological contextualism

11 Knowledge, justification, and truth

The apparent possibility of clairvoyant knowledge

Internalism and externalism in epistemology

Some varieties of internalism and externalism

The overall contrast between internalism and externalism

Internalist and externalist versions of virtue epistemology

Some apparent problems for virtue epistemology

The internality of justification and the externality of knowledge

Justification, knowledge, and truth

Why is knowledge preferable to merely true belief?

The value of knowledge compared with that of justified true belief

The correspondence theory of truth

Minimalist and redundancy accounts of truth

12 Scientific, moral, and religious knowledge

The focus and grounding of scientific knowledge

Scientific imagination and inference to the best explanation

The role of deduction in scientific practice

Fallibilism and approximation in science

Scientific knowledge and social epistemology

Social knowledge and the idea of a scientific community

Preliminary appraisal of relativist and noncognitivist views

Moral versus “factual” beliefs

Kantian rationalism in moral epistemology

Utilitarian empiricism in moral epistemology

Kantian and utilitarian moral epistemologies compared

Evidentialism versus experientialism

The perceptual analogy and the possibility of direct theistic knowledge

Problems confronting the experientialist approach

Justification and rationality, faith and reason

Acceptance, presumption, and faith

The possibility of pervasive error

Perfectly realistic hallucination

Two competing epistemic ideals: believing truth and avoiding falsehood

Some dimensions and varieties of skepticism

Skepticism about direct knowledge and justification

Inferential knowledge and justification: the problem of induction

Knowing, knowing for certain, and telling for certain

Entailment as a requirement for inferential justification

Negative versus positive defenses of common sense

Deducibility, evidential transmission, and induction

Epistemic and logical possibility

Entailment, certainty, and fallibility

The authority of knowledge and the cogency of its grounds

Epistemic authority and cogent grounds

Grounds of knowledge as conferring epistemic authority

Exhibiting knowledge versus dogmatically claiming it

Prospects for a positive defense of common sense

The challenge of rational disagreement

Dogmatism, fallibilism, and intellectual courage

[Front Matter]

[Synopsis]

This comprehensive introduction explains the concepts and theories central to understanding knowledge. The third edition features new sections on such topics as the nature of intuition, the skeptical challenge of rational disagreement, and “the value problem”—the question why knowledge is preferable to mere true belief. Special features of the third edition of Epistemology include:

-

enhanced treatment of key topics such as perception, scientific hypotheses, self-evidence and the a priori, testimony, contextualism, understanding, and virtue epistemology

-

expanded discussion of the relation between epistemology and related fields, especially philosophy of mind, philosophy of science, and ethics

-

greater clarity for undergraduate readers.

Praise for the third edition:

“. . . Robert Audi’s Epistemology, Third Edition, is the most authoritative, comprehensive, and state-of-the-art textbook in the field. In clear, masterful prose, Audi covers all the main topics in epistemology . . . Every student of epistemology—new and old—should read this book.”

—Peter Graham, University of California, Riverside

“. . . unusually comprehensive, elegantly structured, and accessible . . . a cutting-edge treatment of the latest debates about the nature of intuitions, the significance of rational disagreement, and the value of knowledge and justified true belief.”

—Ralph Kennedy, Wake Forest University

“. . . a well-motivated, comprehensive, accessible introduction for students as well as an original, exciting, cutting-edge work of epistemology in its own right. Novices and experts alike will continually profit—and tremendously so—from studying it . . . an ideal text for undergraduate courses in epistemology, and even graduate-level surveys.”

—E.J. Coffman, University of Tennessee

Praise for the second edition:

“. . . philosophically insightful and masterfully written—even more so in its new edition. Guaranteed to fascinate the beginner while retaining its exalted status with the experts.”

—Claudio de Almeida, PUCRS, Brazil

“My students like this book and have learned much from it, as I have . . . Epistemology . . . is simply the best textbook in epistemology that I know of.”

—Thomas Vinci, Dalhousie University

Praise for the first edition:

“No less than one would expect from a first-rate epistemologist who is also a master expositor . . . A superb introduction.”

—Ernest Sosa, Rutgers University

“This is a massively impressive book, introducing . . . virtually all the main areas of epistemology lucid and highly readable, while not

shirking the considerable complexities of his subject matter.”

—Elizabeth .M. Fricker, University of Oxford

“A state-of-the-art introduction to epistemology by one of the leading figures in the field.”

—William P. Alston, Syracuse University

Robert Audi is John A. O’Brien Professor of Philosophy at the University of Notre Dame and author of many papers and books on knowledge and belief, justification, and rationality.

[Title Page]

Epistemology

A Contemporary Introduction to the

Theory of Knowledge

Third Edition

Robert Audi

NEW YORK AND LONDON

Routledge Contemporary Introductions to Philosophy

Series editor: Paul K Moser, Loyola University of Chicago

This innovative, well-structured series is for students who have already done an introductory course in philosophy. Each book introduces a core general subject in contemporary philosophy and offers students an accessible but substantial transition from introductory to higher-level college work in that subject. The series is accessible to non-specialists and each book clearly motivates and expounds the problems and positions introduced. An orientating chapter briefly introduces its topic and reminds readers of any crucial material they need to have retained from a typical introductory course. Considerable attention is given to explaining the central philosophical problems of a subject and the main competing solutions and arguments for those solutions. The primary aim is to educate students in the main problems, positions, and arguments of contemporary philosophy rather than to convince students of a single position.

Epistemology

Third edition

Robert Audi

Philosophy of Mind

Third edition

John Heil

Philosophy of Perception

William Fish

Metaphysics

Third edition

Michael J. Loux

Philosophy of Mathematics

Second edition

James Robert Brown

Classical Philosophy

Christopher Shields

Classical Modern

Philosophy

Jeffrey Tlumak

Ethics

Harry Gensler

Philosophy of Science

Second edition

Alex Rosenberg

Philosophy of Biology

Alex Rosenberg and Daniel W. McShea

Philosophy of Language

Second edition

Willam G. Lycan

Philosophy of Religion

Keith E. Yandell

Philosophy of Art

Noel Carroll

Philosophy of Psychology

Jose Bermudez

Social and Political

Philosophy

John Christman

Continental Philosophy

Andrew Cutrofello

Free Will (forthcoming)

Michael McKenna

Ethics (forthcoming)

Second edition

Harry Gensler

Feminist Philosophy (forthcoming)

Lorraine Code

Philosophy of Literature (forthcoming)

John Gibson

[Copyright]

First edition published 1998, second edition published 2003 by Routledge

This edition first published 2011 by Routledge

270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016

Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2010.

To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.

First edition © 1998 Taylor & Francis

Second edition © 2003 Taylor & Francis

Third edition © 2011 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Audi, Robert

Epistemology : a contemporary introduction to the theory of knowledge / Robert Audi. — 3rd ed.

p. cm. — (Routledge contemporary introductions to philosophy) Includes bibliographical references and index.

[etc.]

1. Knowledge, Theory of. I. Title. BD161.A783 2010

121—dc22

2010005139

ISBN 13: 978-0-415-87922-4 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-415-87923-1 (pbk)

[Dedication]

To Malou

Contents

Preface to the first edition xiii

Acknowledgments to the first edition xvi

Preface to the second edition xviii

Acknowledgments to the second edition xx

Preface to the third edition xxi

Acknowledgments to the third edition xxii

Introduction: a sketch of the sources and nature of belief, justification, and knowledge 1

Perception, belief, and justification 1

Justification as process, as status, and as property 2

Knowledge and justification 4

Memory, introspection, and self-consciousness 5

Reason and rational reflection 5

Testimony 6

Basic sources of belief, justification, and knowledge 6

Three kinds of grounds of belief 7

Fallibility and skepticism 8

Overview 9

Part One

Sources of justification, knowledge, and truth 13

1 Perception: sensing, believing, and knowing 16

The elements and basic kinds of perception 17

Seeing and believing 22

Perceptual justification and perceptual knowledge 26

Notes 31

2 Theories of perception: sense experience, appearances, and reality 38

Some commonsense views of perception 38

The theory of appearing 40

Sense-datum theories of perception 41

Adverbial theories of perception 47

Adverbial and sense-datum theories of sensory experience 49

Phenomenalism 51

Perception and the senses 55

Notes 59

3 Memory: the preservation and reconstruction of the past 62

Memory and the past 63

The causal basis of memory beliefs 64

Theories of memory 66

Remembering, recalling, and imaging 72

Remembering, imaging, and recognition 74

The epistemological centrality of memory 75

Notes 79

4 Consciousness: the life of the mind 84

Two basic kinds of mental properties 84

Introspection and inward vision 86

Some theories of introspective consciousness 87

Consciousness and privileged access 91

Introspective consciousness as a source of justification and knowledge 96

Notes 100

5 Reason I: understanding, insight, and intellectual power 104

Self-evident truths of reason 104

The classical view of the truths of reason 107

The empiricist view of the truths of reason 116

Notes 121

6 Reason II: meaning, necessity, and provability 130

The conventionalist view of the truths of reason 130

Some difficulties and strengths of the classical view 133

Reason, experience, and a priori justification 138

Notes 145

7 Testimony: the social foundation of knowledge 150

The nature of testimony: formal and informal 150

The psychology of testimony 151

The epistemology of testimony 155

The indispensability of testimonial grounds 161

Notes 167

Part Two

The structure and growth of justification and knowledge 173

8 Inference and the extension of knowledge 176

The process, content, and structure of inference 177

Inference and the growth of knowledge 182

Source conditions and transmission conditions for inferential knowledge and justification 185

Memorial preservation of inferential justification and inferential knowledge 197

Notes 199

9 The architecture of knowledge 206

Inferential chains and the structure of belief 206

The epistemic regress problem 210

The epistemic regress argument 215

Foundationalism and coherentism 216

Holistic coherentism 217

The nature of coherence 221

Coherence and second-order justification 229

Moderate foundationalism 232

Notes 236

Part Three

The nature and scope of justification and knowledge 243

10 The analysis of knowledge: justification, certainty, and reliability 246

Knowledge and justified true belief 246

Knowledge conceived as the right kind of justified true belief 248

Naturalistic accounts of the concept of knowledge 253

Problems for reliability theories 257

Notes 264

11 Knowledge, justification, and truth: internalism, externalism, and intellectual virtue 270

Knowledge and justification 270

Internalism and externalism in epistemology 272

Internalist and externalist versions of virtue epistemology 277

Justification, knowledge, and truth 281

The value problem 282

Theories of truth 286

Concluding proposals 290

Notes 292

12 Scientific, moral, and religious knowledge 298

Scientific knowledge 298

Moral knowledge 308

Religious knowledge 319

Notes 328

13 Skepticism I: the quest for certainty 334

The possibility of pervasive error 334

Skepticism generalized 337

The egocentric predicament 343

Fallibility 344

Uncertainty 347

Notes 353

14 Skepticism II: the defense of common sense in the face of fallibility 358

Negative versus positive defenses of common sense 358

Deducibility, evidential transmission, and induction 359

The authority of knowledge and the cogency of its grounds 362

Refutation and rebuttal 365

Prospects for a positive defense of common sense 366

The challenge of rational disagreement 371

Skepticism and common sense 374

Notes 375

15 Conclusion 379

Short annotated bibliography of books in epistemology

Index

Preface to the first edition

This book is a wide-ranging introduction to epistemology, conceived as the theory of knowledge and justification. It presupposes no special background in philosophy and is meant to be fully understandable to any generally educated, careful reader, but for students it is most appropriately studied after completing at least one more general course in philosophy.

The main focus is the body of concepts, theories, and problems central in understanding knowledge and justification. Historically, justification— sometimes under such names as ‘reason to believe’, ‘evidence’, and ‘war- rant’—has been as important in epistemology as knowledge itself. This is surely so at present. In many parts of the book, justification and knowledge are discussed separately; but they are also interconnected at many points. The book is not historically organized, but it does discuss selected major positions in the history of philosophy, particularly some of those that have greatly influenced human thought. Moreover, even where major philosophers are not mentioned, I try to take their views into account. One of my primary aims is to facilitate the reading of those philosophers, especially their epistemological writings. It would take a very long book to discuss representative contemporary epistemologists or, in any detail, even a few historically important epistemologies, but a shorter one can provide many of the tools needed to understand them. Providing such tools is one of my main purposes.

The use of this book in the study of philosophy is not limited to courses or investigations in epistemology. Epistemological problems and theories are often interconnected with problems and theories in the philosophy of mind; nor are these two fields of philosophy easily separated (a point that may hold, if to a lesser extent, for any two central philosophical fields). There is, then, much discussion of the topics in the philosophy of mind that are crucial for epistemology, for instance the phenomenology of perception, the nature of belief, the role of imagery in memory and introspection, the variety of mental properties figuring in self-knowledge, the nature of inference, and the structure of a person’s system of beliefs.

Parts of the book might serve as collateral reading not only in pursuing the philosophy of mind but also in the study of a number of philosophers often discussed in philosophy courses, especially Plato, Aristotle, Aquinas,

Descartes, Leibniz, Locke, Berkeley, Hume, Kant, and Mill. The book might facilitate the study of moral philosophy, such as Kantian and utilitarian ethics, both discussed in some detail in Chapter 9; and it bears directly on topics in the epistemology of religion, some of which are also discussed in Chapter 9.

The writing is intended to be as simple and concrete as possible for a philosophically serious introduction that does not seek simplicity at the cost of falsehood. The territory surveyed, however, is extensive and rich. This means that the book cannot be traversed quickly without missing landmarks or failing to get a view of the larger segments and their place in the whole. Any one chapter can perhaps be read at a sitting, but experience has shown that even the shortest chapter covers too many concepts and positions for most readers to assimilate in a single reading and far more than most instructors can cover in any detail in a single session.

To aid concentration on the main points, and to keep the book from becoming more complicated, notes are limited, though parenthetical references are given in some places and there is also a short selected bibliography with thumbnail annotations. By and large, the notes are not needed for full comprehension and are intended mainly for professional philosophers and serious students. There are also some subsections that most readers can probably scan, or even skip, without significant loss in comprehending the main points of the relevant chapter. Technical terms are explained briefly when introduced and are avoided when they can be. Most of the major terms central in epistemology are defined or explicated, and boldfaced numbers in the index indicate main definitional passages. But some are indispensable: they are not mere words, but tools; and some of these terms express concepts valuable outside epistemology and even outside philosophy. The index, by its boldfaced page references to definitions, obviates a glossary.

It should also be stressed that this book is mainly concerned to introduce the field of epistemology rather than the literature of epistemology—an important but less basic task. It will, however, help non-professional readers prepare for a critical study of that literature, contemporary as well as classical. For that reason, too, some special vocabulary is introduced and a number of the notes refer to contemporary works.

The sequence of topics is designed to introduce the field in a natural progression: from the genesis of justification and knowledge (Part One), to their development and structure (Part Two), and thence to questions about what they are and how far they extend (Part Three). Even apart from its place in this ordering, each chapter addresses a major epistemological topic, and any subset of the chapters can be studied in any order provided some appropriate effort is made to supply the (generally few) essential points for which a later chapter depends on an earlier one.

For the most part this book does epistemology rather than talk about it or, especially, about its literature. In keeping with that focus, the ordering of chapters is intended to encourage understanding epistemology before discussing it in large-scale terms, for instance before considering what sort of epistemological theory, say normativist or naturalistic, best accounts for knowledge. My strategy is, in part, to discuss myriad cases of justification and knowledge before approaching analyses of what they are, or the skeptical case against our having them.

In one way, this approach differs markedly from that of many epistemological books. I leave the assessment of skepticism for the last chapter; early passages indicate that skeptical problems must be faced and, in some cases, how they are connected with the subject at hand or are otherwise important. Unlike some philosophers, I do not think extensive discussion of skepticism is the best way to motivate the study of epistemology. Granted, historically skepticism has been a major motivating force; but it is not the only one, and epistemological concepts hold independent interest. Moreover, in assessing skepticism I use many concepts and points developed in earlier chapters; to treat it early in the book, I would have to delay assessing it.

There is also a certain risk in posing skeptical problems at or near the outset: non-professional readers may tend to be distracted, even in discussing conceptual questions concerning, say, what knowledge is, by a desire to deal with skeptical arguments purporting to show that there is none. There may be no best or wholly neutral way to treat skepticism, but I believe my approach to it can be adapted to varying degrees of skeptical inclination. An instructor who prefers to begin with skepticism can do so by taking care to explain some of the ideas introduced earlier in the book. The first few sections of Chapter 10 (Chapter 13 in the third edition), largely meant to introduce and motivate skepticism, presuppose far less of the earlier chapters than the later, evaluative discussion; and most of the chapter is understandable on the basis of Part One, which is probably easier reading than Part Two.

My exposition of problems and positions is meant to be as nearly unbiased as I can make it, and where controversial interpretations are unavoidable I try to present them tentatively. In many places, however, I offer my own view. Given the scope of the book, I cannot provide a highly detailed explanation of each major position discussed, or argue at length for my own views. I make no pretense of treating anything conclusively. But in some cases—as with skepticism—I do not want to leave the reader wondering where I stand, or perhaps doubting that there is any solution to the problem at hand. I thus propose some tentative positions for critical discussion.

Acknowledgments to the first edition

This book has profited from my reading of many articles and books by contemporary philosophers, and from many discussions I have had with them and, of course, with my students. I cannot mention all of these philosophers, and I am sure that my debt to those I will name—as well as to some I do not, such as some whose journal papers I have read but have not picked up again, and some I have heard at conferences—is incalculable. Over many years, I have benefited greatly from discussions with William Alston, as well as from reading his works; and I thank him for detailed critical comments on parts of the manuscript. Reading of books or articles (or both) by Roderick Chisholm, Richard Foley, Paul Moser, Alvin Plantinga, Walter Sinnott-Armstrong, and Ernest Sosa, and a number of discussions with them, have also substantially helped me over many years. My colleagues at the University of Nebraska, especially Albert Casullo, and several of my students have also helped me at many points. I have learned greatly from the participants in the National Endowment for the Humanities seminars and institutes I have directed. I also benefited much from the papers given to the seminars or institutes by (among others) Laurence BonJour, Fred Dretske, Alvin Goldman, Gilbert Harman, Keith Lehrer, Ruth Marcus, and John Perry, with all of whom I have been fruitfully discussing epistemological topics on one occasion or another for many years.

In relation to some of the main problems treated in the book, I have learned immensely from many other philosophers, including Frederick Adams, Robert Almeder, David Armstrong, John A. Barker, Richard Brandt, Panayot Butchvarov, Carol Caraway, the late Hector-Neri Castaneda, Wayne Davis, Michael DePaul, Susan Feagin, Richard Feldman, Roderick Firth, Richard Fumerton, Carl Ginet, Alan Goldman, Risto Hilpinen, Jaegwon Kim, John King-Farlow, Peter Klein, Hilary Kornblith, Christopher Kulp, Jonathan Kvanvig, Brian McLaughlin, George S. Pappas, John Pollock, Lawrence Powers, W.V. Quine, William Rowe, Bruce Russell, Frederick Schmitt, Thomas Senor, Robert Shope, Donna Summerfield, Marshall Swain, William Throop, Raimo Tuomela, James Van Cleve, Thomas Vinci, Jonathan Vogel, and Nicholas Wolterstorff. In most cases I have not only read some epistemological work of theirs, but discussed one or another epistemological problem with them in detail.

Other philosophers whose comments or works have helped me with some part of the book include Anthony Brueckner, Stewart Cohen, Earl Conee, Dan Crawford, Jonathan Dancy, Timothy Day, Robert Fogelin, Elizabeth Fricker, Bernard Gert, Heather Gert, David Henderson, Terence Horgan, Dale Jacquette, Eric Kraemer, Noah Lemos, Kevin Possin, Dana Radcliffe, Nicholas Rescher, Stefan Sencerz, James Taylor, Paul Tidman, Mark Timmons, William Tolhurst, Mark Webb, Douglas Weber, Umit Yalgin, and Patrick Yarnell.

I owe special thanks to the philosophers who generously commented in detail on all or most of some version of the manuscript: John Greco, Louis Pojman, and Matthias Steup. Their numerous remarks led to many improvements. Detailed helpful comments were also provided by readers for the Press, including Nicholas Everett, Frank Jackson, and Noah Lemos. All of the philosophers who commented on an earlier draft not only helped me eliminate errors, but also gave me constructive suggestions and critical remarks that evoked both clarification and other improvements. I am also grateful for permission to reuse much material that appears here in revised form from my Belief, Justification, and Knowledge (Wadsworth Publishing Co., 1988) and I thank the editor of American Philosophical Quarterly for allowing me to use material from ‘The Place of Testimony in the Fabric of Knowledge and Justification’ (vol. 34, 1997). For advice and help at several stages I thank Paul Moser, Editor of the series in which this book appears, and Adrian Driscoll and the staff at Routledge in London, including Moira Taylor and Sarah Hall, and Dennis Hodgson.

Robert Audi

February, 1997

Preface to the second edition

This preface will presuppose the Preface to the first edition and can therefore be brief. Many improvements have been made in this edition, but they do not make the previous preface inapplicable, and reading it should help anyone considering a study of even part of the book.

My main concern in revising has been to produce a book that is both philosophically stronger and easier to read. Doing this has required adding new substantive material, making minor changes throughout, adding or extending many examples, making various refinements and corrections, and bringing in new references, notes, and bibliography.

Instructors who have used the volume in their teaching will find that the content and organization are highly similar and that a transition from the first edition to this one is easy. Students and people reading for general interest should find the book easier to understand. The emphasis is still on enhancing comprehension of the field of epistemology—its concepts, problems, and methods—rather than on presenting its literature. But, perhaps even more than in the first edition, the book is generally in close contact with both classical and contemporary literature. In this edition there are also many more references to pertinent books and papers, particularly those published in recent years.

This edition includes more extensive discussion of virtue epistemology and social epistemology, with feminist epistemology figuring significantly (though not exclusively) in relation to social epistemology. The connection of epistemology with philosophy of mind and language also receives more emphasis in this edition. So does contextualism and the related theory of “relevant alternatives.”

I am happy to say that Routledge has published a fine and wide-ranging new collection of readings to accompany this book: Michael Huemer’s Epistemology: Contemporary Readings (2002). Huemer has chosen classical and contemporary book sections and papers that go well with every chapter in the present book; his larger sections match mine; and he offers helpful introductions to each section and study questions on each chapter.

This edition of my book is certainly self-contained, but its integration with Huemer’s supporting collection (for which I have done a long narrative introduction to help both instructors and students) is close, and the two together provide enough substance and diversity to facilitate numerous different kinds of epistemology courses.

Acknowledgments to the second edition

Fortunately, I have continued to benefit from reading of or discussions with most of the people acknowledged above, in the first edition. But since that writing I have come to know the work of many other writers in the field and profited from teaching many more students. I am bound to omit some people I should thank, but I want to acknowledge here a number of people not mentioned above: John Broome, Tyler Burge, David Chalmers, Roger Crisp, Mario DeCaro, Keith DeRose, Rosaria Egidi, Guido Frongia, Douglas Geivett, Joshua Gert, Peter Graham, D.W. Hamlyn, Brad Hooker, Christopher Hookway, Michael Huemer, Jonathan Jacobs, Ralph Kennedy, Simo Knuutila, Matthias Lutz-Bachmann, Hugh McCann, John McDowell, Tito Megri, Cyrille Michon, Nicholas Nathan, Ilkka Niiniluoto, Tom O’ Neil, Derek Parfit, James Pryor, Jlenia Quartarone, Joseph Raz, John Searle, John Skorupski, David Sosa, William Talbot, Wilhelm Vossenkuhl, Fritz Warfield and Paul Weirich. In addition, I have continued to benefit from regular exchanges of ideas or papers (usually both) with many philosophers, including William Alston, Laurence BonJour, Panayot Butchvarov, Elizabeth Fricker, Alvin Goldman, John Greco, Gilbert Harman, Jaegwon Kim, Christopher Kulp, Jonathan Kvanvig, Bruce Russell, Walter Sinnott-Armstrong, Ernest Sosa, Matthias Steup, Eleonore Stump, Richard Swinburne, Raimo Tuomela, Nicholas Wolterstorff, and Linda Zagzebski.

Readers of earlier versions of this edition deserve special thanks, not only the anonymous readers for the Press but also Michael Pace, Bruce Russell, Mark Owen Webb, and especially Claudio de Almeida, who provided numerous expert comments and criticism (more, indeed, than I could fully take into account in the available time and space). Special thanks are also due the Editors at Routledge, particularly Tony Bruce, Simon Bailey, and Siobhan Pattinson, whose ideas and support have been immensely helpful.

Preface to the third edition

This edition reflects some of the benefits of nearly a decade of teaching and writing about epistemology since the second edition went to press. There are revisions and improvements throughout. Some revisions are responsive to new developments in epistemological literature; others respond to comments by professional colleagues, including various instructors who have used the book. Student responses have also been taken into account.

The book is structurally much as in the second edition, and the previous prefaces largely apply to it. As before, instructors should read prefatory material and the introduction. Long chapters have been divided, but the chapters remain cumulative in content. Most of them, however, can be read independently of the others or by simply looking into some earlier chapter at certain points. The index may also help readers, and its boldface numerals indicate places where the term in question is defined.

Those who have used the second edition will find no difficulty adjusting their teaching or discussions to this one. Chapters that have been divided still cover the same issues, though with new material included and revisions of much that is included. The fit with Michael Huemer’s large collection of major papers (cited in the bibliography) is equally good.

Some topics treated in this edition are not addressed in the second. These include the nature of intuitions, the skeptical challenge of rational disagreement, and the value problem: the range of questions concerning why knowledge and justified true belief have value beyond that of merely true belief. Other topics receive considerably more exploration than in the second edition, especially contextualism, perception (including perceptual content), self-evidence and the a priori, memorial justification, inferential versus direct knowledge, inference to the best explanation, scientific hypotheses, testimony and trust, understanding, and virtue epistemology.

Acknowledgments to the third edition

I have been fortunate in being able to exchange ideas with most of the philosophers named in the previous two sets of acknowledgments, and this book has continued to benefit from those discussions. I look back on them with much gratitude. I should particularly mention continuing conversations with the late William P. Alston and with Laurence BonJour, Mario DeCaro, Elizabeth Fricker, Peter Graham, John Greco, Ralph Kennedy, Peter Klein, Christopher Kulp, Jonathan Kvanvig, Jennifer Lackey, Bruce Russell, Walter Sinnott-Armstrong, Ernest Sosa, and Thomas Vinci.

On one or another topic in the book I have greatly benefited from epistemological discussions with my Notre Dame colleagues Marian David, Michael DePaul, Peter van Inwagen, Alvin Plantinga, Leopold Stubenberg, and Fritz Warfield. Interactions with Andrew Bailey, Michael Bergmann, E.J. Coffman, Roger Crisp, Claudio De Almeida, Keith DeRose, Fred Dretske, Richard Feldman, Richard Fumerton, Alvin Goldman, Christopher Green, Stephen Grimm, Michael Huemer, Thomas Kelly, Matthew Kennedy, Hilary Kornblith, Markus Lamenranta, Duncan Pritchard, Baron Reed, David Sosa, Jeff Speaks, Matthias Steup, Raimo Tuomela, Jonathan Vogel, Michael Zimmerman, and, especially, Sanford Goldberg and Timothy Williamson have also been of great help to me.

Detailed comments on the penultimate version were provided by Scott Hagaman and (on a few parts) by Matthew Lee and Ezra Cook, and these were of great help. Hagaman also made numerous helpful comments and critical remarks in seminar discussions at Notre Dame. The numerous questions and responses by seminar students at the Universities of Notre Dame and Nebraska have been valuable at many points.

The editorial advice of Andrew Beck, Andrew R. Davidson, Michael Andrews, and, since the book’s first edition, Tony Bruce have helped me in several important matters. They and their staff have been essential in both design and production.

Introduction

A sketch of the sources and nature of belief, justification, and knowledge

Before me is a grassy green field. A line of trees marks its far edge, which is punctuated by a spruce on its left side and a maple on its right. Birds are singing. A warm breeze brings the smell of roses from a nearby trellis. I reach for a glass of iced tea, still cold to the touch and flavored by fresh mint. I am alert, the air is clear, the scene is quiet. My perceptions are quite distinct.

It is altogether natural to think that from perceptions like these, we come to know a great deal—enough to guide us through much of daily life. But we sometimes make mistakes about what we perceive, just as we sometimes misremember what we have done, or infer false conclusions from what we believe. We may then think we know something when in fact we do not, as when we make errors through inattention or are deceived by vivid dreams. And is it not possible that we are mistaken more often than we think?

Perception, belief, and justification

Philosophers have thought a great deal about these matters, especially about the nature of perceiving and about what we can know—or may mistakenly think we know—through perception or through other sources of knowledge, such as memory as a storehouse of what we have learned in the past, consciousness as revealing our inner lives, reflection as a way to acquire knowledge of abstract matters, and testimony as providing knowledge originally acquired by others. In approaching these topics in epistemology—the theory of knowledge and justification—it is appropriate to begin with perception. In my opening description, what I detailed was what I perceived: what I saw, heard, smelled, felt, and tasted. In describing my experience, I also expressed some of what I believed: that there was a green field before me, that there were bird songs, that there was a smell of roses, that my glass felt cold, and that the tea tasted of mint.

It seems altogether natural to believe these things given my experience, and I think I justifiedly believed them. I believed them, not in the way I would if I accepted the result of wishful thinking or of merely guessing, but with justification. By that I mean above all that the beliefs I refer to were justified.

This a good thing; justified beliefs are of a kind it is desirable and reasonable to hold.

Justification as process, as status, and as property

Being justified, in the sense illustrated by my beliefs about what is clearly before me, need not be the result of a process. Being justified is not, for instance, like being purified, which requires a process of purification. My beliefs about what is before me are not justified because they have been through a process of being justified, as when we defend a controversial belief by giving reasons for it. They have not; the question whether they are justified has not even come up. No one has challenged them or even asked why I hold them. They are justified—in the sense that they have the property of being justified—justifiedness—because there is something about them in virtue of which they are natural and appropriate for me as a normal rational person.

We can see what justifiedness is by starting with a contrast. Unlike believing something that one might arrive at through a wild guess in charades, our justified perceptual beliefs are justified for us simply through their arising in the normal way from our clear perceptions. Roughly, they are justified in the sense that they are quite in order from the point of view of the standards for what we may reasonably believe. That, in turn, is roughly what we may believe without being subject to certain kinds of criticism, say as intellectually lax, as sloppy, as overhasty, or the like. Justified beliefs are also a kind that we tend to expect to be true. Imagine someone’s saying ‘His belief is justified, but I don’t expect it to turn out to be true’. Without special explanation, this would be to take away with one hand something given by the other.

In saying that I justifiedly believe there is a green field before me, I am implying something else, something quite different, though it sounds very similar, namely that I am justified in believing there is a green field before me. To see the difference, notice that we can be justified in believing some- thing—roughly in the sense that we have a justification for believing it— without believing it at all, quite as we can be justified in doing something, such as criticizing a person who has failed us, without doing it. Similarly, I might be justified in believing that I can do a certain difficult task, yet fail to believe this until someone helps me overcome my hesitation. I may then see that I should have believed it.

Being justified in believing something is having justification for believing it. This, in turn, is roughly a matter of having ground for believing it (and we also speak of having a ground or a justification or a reason). Just as we can have reason to do things we do not do, we can have reason to believe things we do not believe. You can have reason to go to the library and forget to, and I can have reason to believe someone is making excuses for me but—because I have no inkling that I need any—fail to believe this. Our justification for believing is basic raw material for actual justified belief; and justified belief is commonly good raw material for knowledge.

The two justificational notions are intimately related: if one justifiedly believes something, one is also justified in believing it, hence has justification for believing it. But the converse does not hold: not everything we are justified in believing is something we do believe. When I look at a lawn, I am justified in believing it has more than ten blades of grass per square foot, but I would not normally have any belief about the number of blades per square foot. We have more justificational raw material than we need or use. We do not believe anywhere near the number of things that we have justification to believe. This holds not just in trivial matters but also in, for instance, mathematics.

There are many things we are justified in believing which we do not actually believe, such as the proposition that normal people do not drink 100 liters of water a day. Let us call the first kind of justification—justifiedly believing—belief justification, as it belongs to actual beliefs. It is also called doxastic justification, from the Greek doxa, translatable as ‘belief’. Call the second kind—being justified in believing—situational justification, since it is based on the informational situation one is in. It is a status one has in virtue of that situation. This situation includes not just what one perceives, but also one’s background beliefs and knowledge, such as the belief that people drink at most a few liters of water a day. Situational justification is also called propositional justification, since the proposition in question is justified for the person whose situation provides justification for believing it, and the person has justification for it.

In any ordinary situation in waking life, we have both a lot of general information stored in memory and much specific information presented in our perceptions. We do not need all this information, and our situational justification for believing something is often unaccompanied by our actually believing that it is so. We have situational justification for vastly more justified beliefs than we actually have. Here nature is very generous. We are built to gain from a mere glance enough information to ground vastly more beliefs than we normally form or rely on.

Without situational justification, such as the kind that comes from seeing a green field, there would be no belief justification. I would not, for instance, justifiedly believe that there is a green field before me. We cannot have a justified belief without being in a position to have it. Without situational justification, we are not in such a position. Without belief justification, on the other hand (i.e., doxastic justification), we would have no beliefs of a kind we want and need, those with a positive status—being justified—that makes them appropriate for us as rational creatures and warrants us in expecting them to be true. Belief justification, then, is more than the situational kind it presupposes.

Belief justification occurs when there is a certain kind of connection between what yields situational justification and the justified belief that benefits from it. Belief justification occurs when a belief is grounded in, and thus in a way supported by (or based on), something that gives one situational justification for that belief, such as seeing a field of green. Seeing is of course perceiving; and perceiving is a basic source of knowledge—perhaps our most elemental source, at least in childhood. This is largely why perception is so large a topic in epistemology.

Knowledge and justification

Knowledge would not be possible without belief justification—or a kind of grounding significantly like it. If I did not have the kind of justified belief I do—if, for instance, I were wearing dark sunglasses and could not tell the difference between a green field and a smoothly ploughed one that is really an earthen brown—then on the basis of what I now see I would not know that there is a green field before me.

To see how knowledge fits into the picture so far sketched, consider two points. First, justified belief is important for knowledge because at least the typical things we know we also justifiedly believe on the same basis that grounds our knowing them. If I know someone is making excuses for me, say by the way she explains my lateness, I do not just believe this but justifiedly believe it. Second, much of what we justifiedly believe we also know. Surely I could have maintained, regarding each of the things I have said I justifiedly believed through perception, that I also knew it. And do I not know these things—say that there is a lawn before me and a car on the road beyond it—on the same basis on which I justifiedly believe them, for instance on the basis of what I see and hear? This is very plausible.

As closely associated as knowledge and justified belief are, there is a major difference. If I know that something is so, then it is true, whereas I can jus- tifiedly believe something false. If a normally reliable friend tricked me into believing something false, say that he lost my car keys, I could still justifiedly believe he lost them. We must not assume, then, that everything we learn about justified belief applies to knowledge. We should look at both concepts independently.

I said that I saw the green field and that my belief that there was a green field before me arose from my seeing it. If the belief arose, under normal conditions, from my seeing the field (so that I believed it is there simply because I saw it there), then the belief was true, justified, and constituted knowledge. Again, however, we can alter the example to bring out how knowledge and justification may diverge: the belief might remain justified even if, unbeknownst to me, the grass had been burned up since I last saw it, and there was now a perfect artificial replica of it spread out in grassy-looking strips of cloth that hide the charred ground. Then, although I might think I know the green field is there, I would only falsely believe I know this. Such a bizarre happening is, to be sure, improbable. Still, a justified but false belief could arise in this way.

Memory, introspection, and self-consciousness

As I look at the field before me, I remember carefully cutting a poison ivy vine from the trunk of the spruce. Surely, my memory belief that I cut off this vine is justified. I think I also know that I did this. But here I confess to being less confident than I am of the justification of my perceptual belief, held in the radiant sunlight, that there is (now) a green field before me.

As our memories become less vivid, we tend to be correspondingly less sure that our beliefs apparently based on them are justified. Still, I distinctly recall cutting the vine. The stem was furry; it was bonded to the tree trunk; the cutting was difficult and slightly wounded the tree. By contrast, I have no belief about whether I did this in the summer or the fall. I entertain the proposition that it was in the summer; I consider whether it is true; but, being utterly uncertain, I suspend judgment on it. I thus neither believe it nor disbelieve it, that is, believe it is false. My stance is one of non-belief. I need not try to force myself to resolve the question and judge the proposition either way. I might need to resolve it if something important turned on when I did the pruning; but here suspended judgment, with the resulting non-belief, is not uncomfortable.

As I think about cutting the vine, it occurs to me that in recalling that task, I am vividly imaging it. Here, I seem to be looking into my own consciousness, thus engaging in a kind of introspection. I can still see, in my mind’s eye, the furry vine clinging to the tree, the ax, the sappy wound along the trunk where the vine was severed from it. I have turned my attention inward to my own imagery. The object of my attention, my own imaging of the scene, seems internal and is present to my consciousness, though its object is external and long gone by. But clearly, I believe that I am imaging the vine; and there is no apparent reason to doubt that I justifiedly believe this and know that it is so. This is a simple case of self-knowledge.

Reason and rational reflection

I now look back at the field and am struck by how perfectly rectangular it looks. If it is perfectly rectangular, then its corners are right angles. Here I believe something different in kind from the things cited so far: that if the field is rectangular, then its corners are right angles. This is a geometrical belief. I do not hold it on the same sort of basis I have for the other things I have mentioned believing. My conception of geometry as applied to ideal figures seems to be my basis. On that basis, my belief seems to be firmly justified and to constitute knowledge.

I can see that the spruce is taller than the maple, and that the maple is taller than the crab apple tree on the lawn closer by. I now realize that the spruce is taller than the crab apple. My underlying belief here is that if one thing is taller than a second and the second taller than a third, then the first is taller than the third. And, perhaps even more than the geometrical belief, this abstract belief seems to arise simply from my grasp of the concepts in question, above all the concept of one thing’s being taller than another.

Testimony

The season has been dry, and it now occurs to me that the roses will not flourish without a good deal of water. But this I do not believe simply on the basis of perception. One source from which I learned it is repeated observation. But there is another possible source: although much knowledge comes directly from our own experience, much also originates with testimony from others. I have received testimony as to where on the stem to trim off dead roses. If I did not learn about watering roses from my own experience, I could have learned the same things from testimony, just as I learned from a friend how far back to clip off dead roses.

To be sure, I need perception, such as hearing what I am told, to acquire knowledge on the basis of testimony, just as I needed perception to learn these things about roses on my own; and I need memory to retain them whatever their source. They are, however, generalizations and hence do not arise from perception in the direct and apparently simple way my visual beliefs do, or emerge from memory in the way my beliefs about past events I witnessed do. But do I not still justifiedly believe that the roses will not flourish without a lot of water? The commonsense view is that I both justifiedly believe and know this about roses, and that I can know it either through generalizing—a kind of reasoning—from my own observations, or from testimony, or from both.

Basic sources of belief, justification, and knowledge

The examples just given represent what philosophers have called perceptual, memorial, introspective, a priori, inductive, and testimony-based beliefs. The first four kinds are basic in epistemology. My belief that the glass is cold to the touch is perceptual, being based as it is on tactual perception. My belief that I cut the poison ivy vine from the spruce is memorial, since it is stored in my memory and held because of that fact. My belief that I am imagining a green field is called introspective because it is conceived as based on “looking within” (the etymological meaning of ‘introspection’); but it could also be called simply self-directed: no “peering” within or special concentration is required. My belief that if the spruce is taller than the maple and the maple is taller than the crab apple then the spruce is taller than the crab apple is called a priori (meaning, roughly, based on what is “prior” to observational experience) because it apparently arises not from experience of how things actually behave, but simply in an intuitive way. It arises from a rational grasp of the key concepts one needs in order to have the belief, such as the concept of one thing’s being taller than another.

By contrast, my belief that the roses will not grow well without abundant water does not arise directly from one of the four basic sources just mentioned: perception, memory, introspection, and a priori intuition (reason, in one sense of the term). It is called inductive because it is formed (and held) on the basis of a generalization from something more basic, in this case what I learned from perceptual experiences with roses. Those experiences, apparently through my beliefs recording them, “lead into” the generalization about roses, to follow the etymological meaning of ‘induction’. For instance, I remember numerous cases in which roses have faded when dry, and I eventually concluded that they need abundant water.

Each of the four basic kinds of belief I have described—perceptual, memorial, introspective, and a priori—is grounded in the source from which it arises. The nature of this grounding is explored in detail in Part One, which concerns perception, memory, consciousness, and reason. These sources are commonly taken to provide raw materials for inductive generalizations, as where observations and memories about roses yield a basis for generalizing about their needs.

Any of the beliefs we considered could instead have been grounded in testimony (the topic of Chapter 7), had I formed the beliefs on the basis of being given the same information by someone I trust. That person, however, would presumably have acquired it through one of these other sources (or ultimately through someone’s having done so), and this makes testimony a different kind of source. This is why testimony is not a basic source of knowledge. It is still, however, incalculably important for human knowledge and unlimitedly broad. It can, for instance, justify a much wider range of propositions than perception can. We can credibly tell others virtually anything we know.

Three kinds of grounds of belief

Our examples illustrate not only grounding of beliefs in a source, such as perception or introspection, but also how they are grounded in these sources. There are at least three important kinds of grounding of beliefs—ways they are grounded. These are causal, justificational, and epistemic grounding. All three are important for many major epistemological questions.

Consider my belief that there is a green field before me. It is causally grounded in my experience of seeing the field because that experience produces or underlies the belief. It is justificationally grounded in that experience because the experience, or at least some element in the experience, justifies my belief. And it is epistemically grounded in the experience because in virtue of that experience my belief constitutes knowledge that there is a green field before me (‘epistemic’ comes from the Greek episteme meaning, roughly, ‘knowledge’). These three kinds of grounding very often coincide (though Chapter 11 will describe important cases in which knowledge and justification do not). I will thus often speak simply of a belief as grounded in a source, such as visual experience, when what grounds the belief does so in all three ways.

Causal, justificational, and epistemic grounding each go with a very common kind of question about belief. Let me illustrate.

Causal grounding goes with ‘Why do you believe that?’ An answer to this, asked about my belief that there is a green field before me, would be that I see it. This is the normal kind of reply; but as far as mere causal production of beliefs goes, the answer could be brain manipulation or mere hypnotic suggestion. If, however, mere brain manipulation or mere hypnotic suggestion produces a belief, then the causal ground of the belief would not justify it. If, under hypnosis, I am told that someone dislikes me and as a result I believe this, the belief is not thereby justified.

Justificational grounding goes with such questions as ‘What is your justification for believing that?’ or ‘What justifies you in thinking that?’ or ‘Why should I accept that?’ (‘Why do you believe that?’ can be asked with this same justification-seeking force.) Again, I might answer that I see it. I might, however, have a justification (the situational kind) that, unlike seeing the truth in question, is not a cause of my believing it.

The justification I cite could also be the testimony of a credible good friend. It could be this even when, by a short circuit, brain manipulation does the causal work of producing my belief and leaves the testimony like a board that slides just beneath a roof beam but bears none of its weight. This shows that an element that provides situational justification for a belief may play no role in producing or supporting the belief, even if this element, like the auxiliary unstressed board, stands ready to play a supporting role if the belief is put under pressure by a challenge.

Epistemic grounding goes with ‘How do you know that?’ Once again, saying that I see it will commonly answer this. Here, however, it may be that a correct answer must cite something that is also a causal ground for the belief (a matter discussed in Chapter 10). Certainly a justificational ground need not be a ground of knowledge. One can justifiedly believe a proposition without knowing it.

Clearly, the same sorts of points can be made for the other five cases I have described: memorial beliefs are grounded in memory, self-directed (“introspective”) beliefs in consciousness, inductively based beliefs in further, premise-beliefs that rest on experience, a priori beliefs in reason, and testimony-based beliefs in testimony.

Fallibility and skepticism

Even well-grounded beliefs can be mistaken. We can be deceived by our senses. We are fallible in perceptual matters, as in our memories, in our reasoning, and in other respects. One might now wonder, as skeptics do, whether we know even that it is improbable that our senses are now deceiving us. One might also wonder whether, when we take ourselves to see green grass, we are even justified in our belief that no such mistake has occurred.

Suppose that I am in an unfamiliar park. I might not know or even justifiedly believe that artificial grass has not replaced the natural grass I take to be before me. (I may have heard of such substitutions and may have no good reason to believe this has not happened, though I do not consider the matter.) Am I justified in believing that there is green grass before me?

Suppose that I am not justified in believing there is green grass before me. If not, how can I be justified in believing what appear to be far less obvious truths, such as that my home is secure against the elements, my car safe to drive, and my food free of poison? And how can I know the many things I need to know in life, such as that my family and friends are trustworthy, that I can control my behavior and thus partly determine my future, and that the world we live in at least approximates the structured reality portrayed by common sense and science?

These are difficult and important questions. They indicate how insecure and disordered human life would be if we could not suppose that we possess justified beliefs and knowledge. We stake our lives every day on what we take ourselves to know. It would be unsettling to revise this stance and retreat to the view that at best we have justification to believe. But if we had to give up even this moderate view and to conclude, say, that what we believe is not even justified, we would face a crisis. Much later, in discussing skepticism, I will explore such questions at some length. Until then I will assume the commonsense view that beliefs with a basis like that of my belief that there is a green field before me are not only justified but also constitute knowledge.

Once we proceed on this commonsense assumption, it is easy to see that there are many different kinds of circumstances in which beliefs arise in such a way that they are apparently both justified and constitute knowledge. In considering this variety of circumstances yielding justification and knowledge, we can explore how beliefs are related to perception, memory, consciousness, reason, and testimony (the topics of Chapters 1-7).

Overview

There is a great deal more to be said about each of these sources of belief, justification, and knowledge and about how they ground what they do ground. The first seven chapters explore, and in some cases compare, the basic sources of belief, justification, and knowledge.

In the light of what those chapters show, we can discuss the development and structure of knowledge and justification (the task of Part Two). Much of what we believe does not come directly from perception, memory, introspection, or reflection of the kind appropriate to knowledge of such truths as those of elementary mathematics or those turning on our grasp of simple relations, for instance the proposition that if the spruce is taller than the maple, then the maple is shorter than the spruce, which we know by virtue of understanding the relations expressed by ‘taller’ and ‘shorter’. We must explore how inference and other developmental processes expand our body of knowledge and justified beliefs (this is the task of Chapter 8). Moreover,

once we think of a person as having the resulting complex body of knowledge and justified belief, we encounter the questions of what structure that large and intricate body has, and of how its structure is related to the amount and kind of knowledge and justification it contains. As we shall see in Part Two, these structural questions take us into an area where epistemology and the philosophy of mind often overlap.

On the basis of what Part One shows about sources of knowledge and justification and what Part Two shows about their development and structure, we can fruitfully proceed to consider more explicitly what knowledge and justification are and what kinds of things can be known (the task of Part Three). It is true that if we had no sense at all of what they are, we could not find the kinds of examples of them needed to explore their sources and their development and structure. If we do not have before us a wide range of examples of justification and knowledge, we lack the data appropriate to seeking a philosophically illuminating analysis of them. It is in the light of the examples and conclusions of Parts One and Two that Chapters 10 and 11 clarify the concept of knowledge, and, to a lesser extent, that of justification, in some detail.

With a conception of knowledge laid out, it is possible to explore the apparent extent of knowledge and justification in three major territories—the scientific, the ethical, and the religious. In exploring these domains, Chapter 12 applies some of the epistemological results of the earlier chapters. These chapters continue to assume the commonsense view that we have a great deal of knowledge and justification. If, however, skepticism is justified, then the commonsense assessment that the first twelve chapters make regarding the extent of knowledge and justification must be revised. Whether skepticism is justified is the focus of Chapters 13 and 14.

Along the way in all fourteen chapters, there is much to be learned about concepts that are important both in and outside epistemology, especially those of belief, causation, certainty, coherence, explanation, fallibility, illusion, inference, intellectual virtue, introspection, intuition, meaning, memory, rationality, reasoning, relativity, reliability, truth, and understanding. There are also numerous epistemological positions to be considered, sometimes in connection with historically influential philosophers. But the main focus will be on the major concepts and problems in the field, not on any particular philosopher or text. This may well be the best way to facilitate studying philosophers and epistemological texts; it will certainly simplify an already complex task.

Knowledge and justification are not only interesting in their own right as central epistemological topics; they also represent positive values in the life of every reasonable person. For all of us, there is much we want to know. We also care whether we are justified in what we believe—and whether others are justified in what they tell us. The study of epistemology can help in making this quest, even if it often does so indirectly. It can certainly help us assess how well we have done in the quest when we review our results.

Well-developed concepts of knowledge and justification can serve as ideals in human life. Positively, we can try to achieve knowledge and justification in relation to subjects that concern us. Negatively, we can refrain from forming beliefs where we think we lack justification, and we can avoid claiming knowledge where we think we can at best hypothesize. If we learn enough about knowledge and justification conceived philosophically, we can better search for them in matters that concern us and can better avoid the dangerous pitfalls that come from confusing mere impressions with justification or mere opinion with knowledge. This is not to say that epistemological knowledge can be guaranteed to yield new everyday knowledge. But the more we know about the constitution of knowledge and justification, the better we can build them through our own inquiries, and the less easily we will fall into the pervasive temptation to take an imitation to be the real thing.

Part One: Sources of justification, knowledge, and truth

1 Perception

Sensing, believing, and knowing

• The elements and basic kinds of perception

Perceptual belief

Perception, conception, and belief

Propositional and objectual perception

• Seeing and believing

Perceptually embedded beliefs

Perception as a source of potential beliefs

The perceptual hierarchy

Simple, objectual, and propositional perception

The informational character of perception

• Perceptual justification and perceptual knowledge

Seeing and seeing as

Perceptual content

Seeing as and perceptual grounds of justification

Seeing as a ground of perceptual knowledge

1 Perception

Sensing, believing, and knowing

As I look at the green field before me, I might believe not only that there is a green field there but also that I see one. And I do see one. I visually perceive it. Both beliefs, the belief that there is a green field there, and the self-referential belief that I see one, are grounded, causally, justificationally, and epistemically, in my perceptual experience. They are produced by that experience, justified by it, and constitute knowledge in virtue of it.

The same sort of thing holds for the other senses. Consider touch. I not only believe, through touch (as well as sight), that there is a glass here, I also feel its cold surface. Both beliefs—that there is a glass here and that it is cold—are grounded in my tactual experience. I could believe these things on the basis of someone’s testimony. My beliefs would then have a quite different status. For instance, my belief that there is a glass here would not be a perceptual belief, but only a belief about a perceptible, that is, a perceivable object, the kind of thing that can be seen, touched, heard, smelled, or tasted. Through testimony we have beliefs about perceptibles we have never seen or experienced in any way.

My concern is not with the hodgepodge of beliefs that are simply about perceptibles, but with perception and perceptual beliefs. Perceptual beliefs are not simply beliefs about perceptibles; they are beliefs grounded in perception. We classify beliefs as perceptual by the nature of their roots, not by the color of their foliage; by their grounds, not their type of content. Those roots may be visual, auditory, and so forth for each perceptual mode. But vision and visual beliefs are an excellent basis for discussing perception, and I will concentrate on them and mention the other senses only when it adds clarity.

Perception is a source of knowledge and justification mainly by virtue of yielding beliefs that constitute knowledge or are justified. But we cannot hope to understand perceptual knowledge and justification simply by exploring those beliefs. We must also understand what perception is and how it yields beliefs. We can then begin to understand how it yields knowledge and justification or—sometimes—fails to yield them.

The elements and basic kinds of perception

There are apparently at least four elements in perception: (1) the perceiver, me; (2) the object, the field I see; (3) the sensory experience, say my visual experience of colors and shapes; and (4) the relation between the object and the subject, commonly taken to be a causal relation by which the object produces the sensory experience in the perceiver. To see the field is apparently to have a certain sensory experience as a result of the impact of the field on our vision.

Some accounts of perception add to the four items on this list; others subtract from it. To understand perception we must consider both kinds of account and how these elements are to be conceived in relation to one another. But first, it is essential to explore examples of perception.

There are several quite different ways to speak of perception. Each corresponds to a different way of perceptually responding to experience. We often speak simply of what people perceive, for instance see. We also speak of what they perceive the object to be, and we commonly talk of facts they know through perception, such as that the grass is long. Visual perception most readily illustrates this, so let us start there.

I see, hence perceive, the green field. Second, speaking in a less familiar way, I see it to be rectangular. Thus, I might say that I know it looks irregular from the nearby hill, but from the air you can see it to be perfectly rectangular. Third, I see that it is rectangular. Perception is common to all three cases. Seeing, which is a paradigm perception, is central in each.