Robert Roberts & Daniel Telech

The Moral Psychology of Gratitude

Moral Psychology of the Emotions

The Emotion-Virtue-Debt Triad of Gratitude: An Introduction to The Moral Psychology of Gratitude

Feeling Grateful: Gratitude Qua Emotion

Being a Grateful Person: Gratitude Qua Virtue

Chapter 1: Gratitude: Generic versus Deep

When Is Deep Gratitude Appropriate?

Chapter 2: Acting from Gratitude

Acting from Gratitude: Complications

Part II: Gratitude, Rights, and Duties

Chapter 3: Obligations of Gratitude: Directedness without Rights

Directives of Different Forces

Directing Means versus Directing Ends

Conclusion: Why Do Debts of Gratitude Exist?

Chapter 5: Gratitude, Rights, and Benefit

Chapter 6: Do Children Owe Their Parents Gratitude?

Conditions for a Duty of Gratitude

Do Children Owe Their Parents Gratitude?

Gratitude for Supererogatory Benefits

What Does a Duty of Gratitude Require of Children?

Why Most People Owe Their Mothers More

Part III: Gratitude as a Reactive Attitude

Chapter 7: Gratitude as a Second-Personal Attitude (of the Heart)

Chapter 8: Gratitude and Resentment: Some Asymmetries

An Asymmetry of Moral Standing

Weighting Gratitude and Resentment

Chapter 9: Gratitude and Norms: On the Social Function of Gratitude

Communities of Respect and the Reactive Attitudes

Gratitude, Intention, and Indeterminacy

Part IV: Authentic Selves and Brains

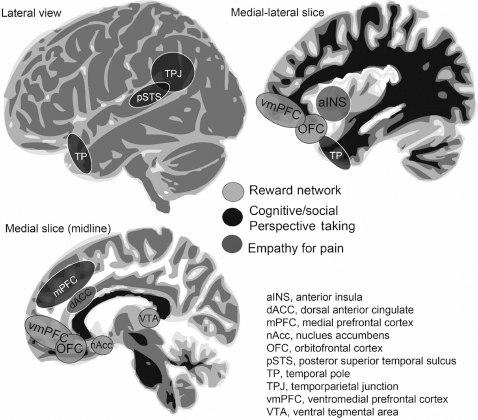

Chapter 10: Neural Perspectives on Gratitude

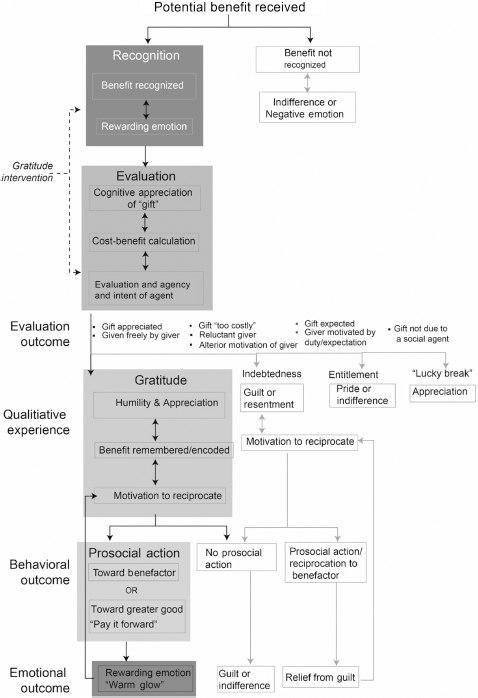

Gratitude as a Multifaceted Construct: A Gateway Model

Precursors to Gratitude: Recognition and Evaluation

The Qualitative Experience of Gratitude

Behavioral Outcomes of Gratitude

Narrative Studies of Gratitude: Who Did What

Neuroeconomic Studies of Gratitude, Exchanges, and Helping

The Future of Brain Research on Gratitude

Chapter 11: Gratitude, Authenticity, and Self-Authorship

Essentialist versus Existentialist Authenticity

Self-Discovery: Essentialist or Existentialist Authenticity?

Cultural Master Narratives of Gratitude and Authenticity

Narrative Tools of Self-Authorship

Themes of Gratitude and Authenticity

Narrative Structure of Gratitude and Authenticity

The Development of Gratitude, Authenticity, and Self-Authorship

Before We Start: Enacting Virtue versus Narrating Virtue

The Development of Narrative Themes and Narrative Structure

Childhood: The Emergence of Authentic Gratitude

Adolescence-Plus: Proto-Authenticity and Principled Gratitude

Adulthood: Existentialist Authenticity and Deep Gratitude

Chapter 12: Gratitude as a Virtue

Chapter 13: Gratitude, Truth, and Lies

Gratitude and Deceitful Benefit

Gratitude, Virtue, and Moral Virtue

Truth and Honesty in Moral Benefit and Gratitude

Chapter 14: Cross-Pollination in the Gardens of Virtue

The Cross-Pollination of Virtue: A Rationale

Cross-Pollination of Virtues in Twelve Step Programs: The Place of Humility

Cross-Pollination of Virtues in the Practice of Lojong: Creating Interdependence through Gratitude

Cross-Pollinating Virtues in Educational and Therapeutic Interventions

Chapter 15: The Virtue of Gratitude and Its Associated Vices

Response-Gratitude and Appreciation

An Elemental Analysis of Response-Gratitude

Chapter 16: Gratitude, Friendship, and Mutuality: Reflections on Three Characters in Bleak House

Moral Psychology of the Emotions

Series Editor: Mark Alfano, Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy, Delft University of Technology

How do our emotions influence our other mental states (perceptions, beliefs, motivations, intentions) and our behavior? How are they influenced by our other mental states, our environments, and our cultures? What is the moral value of a particular emotion in a particular context? This series explores the causes, consequences, and value of the emotions from an interdisciplinary perspective. Emotions are diverse, with components at various levels (biological, neural, psychological, social), so each book in this series is devoted to a distinct emotion. This focus allows the author and reader to delve into a specific mental state, rather than trying to sum up emotions en masse. Authors approach a particular emotion from their own disciplinary angle (e.g., conceptual analysis, feminist philosophy, critical race theory, phenomenology, social psychology, personality psychology, neuroscience) while connecting with other fields. In so doing, they build a mosaic for each emotion, evaluating both its nature and its moral properties.

Other titles in this series:

The Moral Psychology of Contempt,

edited by Michelle Mason

The Moral Psychology of Compassion,

edited by Justin Caouette and Carolyn Price

The Moral Psychology of Disgust,

edited by Nina Strohminger and Victor Kumar

Forthcoming titles in the series:

The Moral Psychology of Regret,

edited by Anna Gotlib

The Moral Psychology of Admiration,

edited by Alfred Archer and André Grahle

The Moral Psychology of Guilt,

edited by Corey J. Maley and Bradford Cokelet

The Moral Psychology of Hope,

edited by Claudia Blöser and Titus Stahl

The Moral Psychology of Gratitude

Edited by Robert Roberts and Daniel Telech

Published by Rowman & Littlefield International Ltd.

6 Tinworth Street, London SE11 5AL

Rowman & Littlefield International Ltd. is an affiliate of Rowman & Littlefield

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706, USA

With additional offices in Boulder, New York, Toronto (Canada), and Plymouth (UK)

Selection and editorial matter © 2019 by Robert Roberts and Daniel Telech

Copyright in individual chapters is held by the respective chapter authors.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: HB 978-1-78660-602-0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

ISBN: 978-1-78660-602-0 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN: 978-1-78660-603-7 (electronic)

Printed in the United States of America

Acknowledgments

Edited volumes, like many other projects that depend on the generosity, trust, and patience of others, are customarily preceded by words of thanks. This volume on gratitude is no exception.

We thank Mark Alfano for his attentiveness and encouragement throughout the editorial process. From suggesting possible authors to improve the breadth of the volume to ideas about acquiring funding in order to workshop the chapter drafts, Mark was generous with his advice and general support. A better series editor is difficult to imagine.

Mark suggested that we submit an application to the Templeton Foundation to fund the workshop, and their generous response enabled us to host a very fruitful meeting in the fall of 2017. They responded with an outright gift, obviating a detailed budget and expense reports. The Templeton Foundation’s kind support enabled us to hold a three-day pre-read workshop at the University of Chicago that brought the volume contributors, as well as some local scholars, into conversation with one another while the contributors worked on their drafts.

We thank Isobel Cowper Coles and Natalie Linh Bolderston at Rowman & Littlefield International for their patient and highly professional support.

Thanks also to the participants of the gratitude workshop at the University of Chicago: Jack Bauer, Agnes Callard, David Carr, Sophie-Grace Chappell, Justin Coates, Cameron Fenton, Liz Gulliford, Bennett Helm, Christina Karns, Brian Leiter, Hichem Naar, Tony Manela, Terrance McConnell, Coleen Macnamara, Adrienne Martin, Colin Shanahan, Stephen White, Marya Schechtman, and Will Small.

Daniel would like to thank Agnes Callard, Brian Leiter, and Paul Russell for their mentorship in thinking about gratitude (and praise-manifesting attitudes generally), and Robert Roberts for showing him the ropes of volume editing and teaching him much about gratitude and philosophy in the process. Bob Roberts would like to thank Daniel Telech for doing most of the work for this volume, including securing our authors, applying for funding for the workshop, and organizing and hosting the workshop.

The Emotion-Virtue-Debt Triad of Gratitude: An Introduction to The Moral Psychology of Gratitude

Robert Roberts and Daniel Telech

Gratitude is a response to another’s goodness. Paradigmatically, one is grateful to another for some benefit. That is, in feeling grateful, you typically construe yourself or someone you care about as a beneficiary and the other—the person to whom you are grateful—as a benefactor. But gratitude represents the benefactor as more than a supplier of benefits. It is a response not simply to beneficence but also to benevolence—goodwill. Natural events and malicious persons both may cause some end of mine to be fulfilled, and I may be glad that the beneficial state of affairs came to be, but such good fortune doesn’t usually dispose me to feel grateful to anyone. This is plausibly because I do not take these benefits to be expressions of benevolence, or goodwill. The claim that gratitude construes another to have acted from goodwill is a mainstay in philosophical discussion of gratitude (e.g., Berger 1975: 299–300; Camenisch 1981; McConnell 1993; Roberts 2004). Gratitude is thus an interpersonal or social emotion.

We hasten to note a usage of the word “gratitude” that does not pick out an inherently interpersonal response; for example, “I am grateful that I got to see a shooting star.” This sense of gratitude, sometimes called “propositional gratitude” (McAleer 2012), involves a relation between a person and a state of affairs, without reference to a benefactor. But little seems to be lost by redescribing instances of so-called propositional gratitude as cases of appreciation (cf. Carr 2013; Roberts 2015; Manela 2016). Whether or not “propositional gratitude” is gratitude only in name, this volume is about the social and agent-directed emotion that involves a triadic relation between two agents and (typically) an action, as expressed by the following kind of sentence: “Abe is grateful to Miranda for helping him move into his new apartment.”

Gratitude has been studied in various aspects. It has been theorized not only as a positive emotion (alongside joy and admiration), but as both a virtue and a grounding kind of debt or duty. This is not an exhaustive list, but the emotion-virtue-debt triad captures a core set of questions about gratitude, so we begin here. It might not be immediately transparent how the emotion-virtue-debt triad of gratitude hangs together. For, while the idea that gratitude is an emotion fits neatly with the idea that gratitude may also be a virtue (or a trait of excellence, whereby one is stably disposed to feel the emotion in the appropriate circumstances and to the appropriate degree), the emotion-debt dyad may be less intelligible. If one’s debt of gratitude is a duty to be grateful, and being grateful amounts to feeling an emotion, then, given that one cannot directly will oneself to feel an emotion, debts of gratitude will seem to violate the “ought implies can” principle. To help render the emotion-virtue-debt triad intelligible, we discuss its elements in turn. Then we briefly summarize the volume’s chapters.

Feeling Grateful: Gratitude Qua Emotion

Gratitude is a pleasant emotion. To be grateful is to take joy in another’s benevolently given benefit to oneself. That is, gratitude is a joyful attitude that represents another to have benefited oneself from goodwill.[1]

Morgan et al. (2014) say that some people, especially in the UK, find gratitude to be unpleasant because of the sense of indebtedness that it involves. Roberts (2016) speculates that such people may be mistaking the situation that calls for gratitude—a benefit has been gratuitously conferred—for gratitude itself, or supposing that any response to such a situation must be gratitude. Such people feel uncomfortable with being indebted, thus perhaps even resenting their benefactors for the benefits they have conferred. This is no doubt a common response; many people dislike feeling indebted and may not be clear about the special kind of indebtedness that goes with gratitude. Also, “benefactors” can be manipulative and domineering, and almost nobody likes being “indebted” to such people. Roberts (2016) argues that if this is what leads some to find “gratitude” unpleasant, the emotion they feel toward their benefactors is not properly called gratitude.

The exact propositional content definitive of gratitude is a matter of debate. In addition to representing another as having benefited one benevolently, it is sometimes held that gratitude represents the benefactor to have acted with the intention of benefiting one, and in a way that exceeds his duties toward the beneficiary (i.e., supererogatorily). Additionally, in feeling grateful, one presumably not only construes oneself as a beneficiary but also welcomes the benefit, and welcomes it as a benefit from this benefactor. What exactly it is to be a benefit is a large and important question in its own right (taken up in part by Macnamara, this volume), but it is worth mentioning that (1) the benefactor’s benefiting the beneficiary and (2) his benevolent attitudes are not always obviously separable. This is not only because one can be grateful to another for his benevolent omission but also because we are sometimes grateful for benevolent attempts, where there is no benefit to speak of apart from the kind or generous motivating attitudes of the benefactor. Though our welfare interests might not be promoted, we sometimes recognize that, as the saying has it, it’s “the thought that counts.” Indeed, Seneca, being a Stoic who thinks the only real goods are attitudes, thinks only the thought counts:

[a] benefit cannot be touched with one’s hand; the business is carried out with one’s mind. There is a big difference between the raw material of a benefit and the benefit itself… . Consequently, the benefit is not the gold, the silver, or any of the things which are thought to be most important; rather, the benefit is the intention of the giver. (On Benefits, 1.5.2)

Thus, on his view, “benevolent attitude” and “benefit” will share the same intension.[2]

As an emotion, gratitude can be considered either episodically or dispositionally. An episode of gratitude is the mental state experienced in joyfully thinking of oneself as benevolently benefited by another. One can count as being grateful, in the sense of having the emotion, however, even when one is not experiencing this joyful state. While being pulled over for speeding, Alex will not be joyful about much, but he can nevertheless be truly described as grateful to Ben for saving his life, assuming he is disposed to appreciate the action when reflecting on Ben’s benevolent deed.

Alex’s gratitude, however, will involve more than a disposition to feel positively about being benefited by another. To have the emotion of gratitude is also to be motivated to respond to one’s benefactor in a way that shows him what the benefit means to one.[3] Someone who is merely happy to have been benefited by another might have no desire to reciprocate or otherwise express his joy to the benefactor. Such a person is easily construed as an ingrate, at least if he is aware of the benevolence from which his benefit proceeds. Alex would hardly count as grateful to Ben if, when presented with the opportunity to help Ben out of an innocent bind, Alex had no motivation to help Ben. A description of someone who is grateful must include his sense of owing thanks to his benefactor. A range of factors may prevent the grateful agent from in fact expressing thanks/reciprocating, but the person who feels grateful will at least be motivated to return the kindness previously shown him.

In many respects, gratitude is the symmetrical opposite of resentment, an angry attitude that represents another to have slighted (or harmed with ill will, or perhaps merely indifference) the resenter (see, e.g., Berger 1975; Roberts 2004). As with gratitude, one can count as resentful of (or “angry with”) another for long stretches of time that include a wide range of (variously valanced) mental episodes. The contrast between gratitude and resentment is of particular importance, given that resentment is often thought to be a paradigmatic vehicle of interpersonal blame. Considered as Strawsonian “reactive attitudes,” resentment and gratitude are a “usefully opposed pair” (Strawson 1962: 77) in that resentment has the affective and motivational profile we associate with second-personal blame, while gratitude has the affective and motivational profile associated with second-personal praise (or “moral credit”). That is, these attitudes are paradigmatic ways of taking others to be responsible (i.e., blameworthy or praiseworthy). But while gratitude (along with admiration and pride) are often mentioned as paradigmatic praise-manifesting attitudes, the nature and norms of blame have thus far received the lion’s share of attention within the moral responsibility literature. Several of this volume’s chapters address the status of gratitude as a reactive attitude, shedding new light on the positive aspect of our responsibility practices.

Being a Grateful Person: Gratitude Qua Virtue

The person who is stably disposed to develop dispositions to feel gratitude plausibly has the trait of gratitude. On the assumption that this trait can be, but is not necessarily, an excellence of character, the person who is stably disposed to develop dispositions to feel gratitude toward the right person, in the right circumstances, in the right way, and to the right degree plausibly possesses the virtue of gratitude.

Thinking of gratitude as a virtue brings into focus that gratitude involves more than experiencing an emotion. Intuitively, the grateful person not only takes joy in another’s having benevolently benefited him but also—on this basis—takes the other’s concerns as providing reasons for action. While one might count as having the emotion of gratitude even if one does not in fact express one’s gratitude, it is often thought to be essential to gratitude that one at least be disposed to express one’s gratitude, where this is a matter of treating the benefactor with goodwill. Sometimes we do this by saying “thank you,” but we often “show our thanks” through more heartfelt and personalized actions. The expression of gratitude is often referred to under the banner of “reciprocation,” though it should be distinguished from repayment that cancels a debt. Unlike repayment, the reciprocation involved in gratitude essentially involves sincerity. I can successfully repay a monetary debt (for example) regardless of the attitudes I have toward my creditor, but gratitude is partly constituted by the beneficiary’s wanting to make a return of kindness (at least in part) for its own sake. This return kindness has the character of an expression of one’s heart, and is often intended as a communication with the benefactor. Though sometimes benefactors don’t want such communication, and so the sensitive beneficiary may refrain from it (see Dickens’s characters John Jarndyce and Esther Summerson, in Roberts, this volume). Plausibly then, to be disposed to have the emotion of gratitude in the right way involves being disposed to reciprocate, that is, to communicate to your benefactor, out of goodwill, what the benefit meant to you.

We emphasize the expressive component of gratitude here for the following reason. The person who is merely joyful about having been benevolently benefited is in many cases the paradigm of ingratitude. It is true that we sometimes call the person who is unhappy with her lot an “ingrate,” but when we say this, we are saying not only that she ought to appreciate what she has been given but she also has a reason to express her gratitude to her benefactor. For, suppose that the ingrate in question comes to take joy in what she has been given, yet displays indifference to her parents, teachers, and friends (perhaps out of an undue sense of self-determination). This person may very well be happy about having been benevolently benefited, but if we continue to think of her as an exemplar of ingratitude, this is because she lacks the disposition to reciprocate sincerely. The grateful person, one who has the virtue of gratitude, is not only disposed to feel the emotion at the right times, toward the right persons, and in the right circumstances, but is also disposed to feel it in the right way. A proper account of the virtue of gratitude will fill in what it is to have these appropriate dispositions. For now, let’s say the disposition to “feel gratitude in the right way” importantly includes the motive to reciprocate or express gratitude to the benefactor. This motivational/behavioral component of the virtuous agent’s grateful response is sometimes considered in isolation. As such, its fulfillment is sometimes theorized as a debt or duty of gratitude.

Debts of Gratitude

It is widely held that being benevolently benefited can generate a debt of gratitude. How to understand “debts of gratitude,” however, is a matter of much debate. These debts are often referred to as generating “obligations (or duties) of gratitude,” but unlike standard obligations, those of gratitude do not seem to provide the benefactor with the right to demand or exact reciprocation from the beneficiary. One explanation of this is that gratitude is a response to generosity (see Chappell this volume and Roberts this volume; see also Seneca’s On Benefits, where gratitude is tightly linked to generosity); for generosity is free giving, giving without requirement of return. To give generously and then turn around and demand repayment would be both inconsistent and boorish. And indeed, those who hold that “repayment of debts of gratitude is […] an obligation (or moral requirement)” (McConnell 1993: Chapter 2; McConnell 2018) typically deny that the benefactor has a claim-right to the beneficiary’s gratitude. What, then, does the idea “A has a duty of gratitude to B” come to? Should talk of duties/obligations/requirements here be understood in terms of desert, such that the beneficiary’s “having a duty of gratitude” reduces to the benefactor’s deserving the beneficiary’s reciprocal return?

These notions of deserving and owing can be connected to the idea of a right, even if not a claim right. Tony Manela (2015: especially 163–166) invokes the notion of an imperfect right for these cases. Although the original benefactor does not have a claim right to demand that the beneficiary reciprocate, she does have standing to remonstrate and express resentment, and this sort of standing affirms her self-respect. (McConnell, this volume, endnote 7)

But it may strike us that even to remonstrate, complain, or resent the ungrateful beneficiary is a compromise with the spirit of generosity unless the remonstrator also occupies the role of moral educator (say, that of a parent) vis-à-vis the ungrateful one. But in that case, the complaint is not justified by the benefactor-beneficiary relationship, but by the parent-child or other educator-learner relationship. We might say that the debt of gratitude is properly felt primarily or even solely by the beneficiary, and that it is felt not as needing to be paid off, but as a lasting bond of love. This would be why Seneca warns us to be careful in selecting our benefactors:

I should be even more careful when seeking someone to be indebted to for a benefit than for money. The financial creditor only has to be paid back as much as I accepted, and once I pay him off then I am free and clear. But I have a larger payment to make to the other creditor, and even after the favor has been returned we are still linked to each other. For once I have paid him back I must start again, and a friendship persists. (On Benefits, 2.18.5)

On this Senecan proposal, the debt of gratitude is inextricable from the beneficiary’s sense of owing reciprocation or thanks, which itself is a component of the joyful emotion of gratitude. This thought coheres with the idea that, whatever else they may be, debts of gratitude are not paradigmatically experienced by the beneficiary simply as to-be-discharged, but rather as opportunities to deepen the relation of interpersonal joy occasioned by the benefactor’s original manifestation of goodwill.

The Chapters

The volume’s first chapter challenges the idea that gratitude is inherently an affective phenomenon. Hichem Naar advances a distinction between generic and deep gratitude, where the former is a matter of merely believing that one has been benevolently benefited. Generic gratitude is neither affective nor does it motivate one to reciprocate. Naar’s proposal is motivated in part by the peculiar features of introspecting our attitudes of gratitude. In contrast to our grasp of whom we love, our grasp of whom we are grateful to is often elusive. Naar argues that the elusiveness of self-attributions of gratitude is well explained by positing a form of (“generic”) gratitude for which it is sufficient to be grateful that one have an evaluative belief with the right content, even if this belief remain largely dormant. Naar then discusses the possible grounds (or rather, the elusiveness of grounds) on which generic gratitude might appropriately become “deep gratitude,” that is, gratitude that is inherently affective and motivational.

Terrance McConnell’s chapter (chapter 2) focuses on a puzzle generated by cases in which an agent has sufficient reason to reciprocate gratefully (“to discharge a debt of gratitude”), but where it may nonetheless be morally desirable to act from reasons other than those of gratitude, especially those of love. When multiple values commend the same action, it is not always clear what the agent’s salient motive should be, or alternatively and more specifically, whether one should benefit another qua original benefactor (i.e., from gratitude), or qua loved one. Complexity is added to the analysis by McConnell’s treating love as possessed of moral content, such that the conflict between acting from love versus from gratitude is not simply a standoff between morality (understood as a burdensome source of motivation) and personal relationships.

Debts of gratitude are the focus of the next set of chapters. Adrienne Martin’s chapter advances a solution to a puzzle concerning obligations of gratitude. While debts of gratitude seem to be instances of directed obligation— the beneficiary has a debt to the benefactor for being benefited—benefactors lack a claim-right to the beneficiary’s gratitude. Unlike standard directed obligations, of which promissory obligations are paradigmatic, “obligations of gratitude” (if there are any) do not seem to give the benefactor the authority to demand the beneficiary’s reciprocation. Martin proposes a novel way to anchor obligations of gratitude. On her proposal, the beneficiary has an obligation of gratitude that corresponds not to a claim-right, but to the benefactor’s “personal expectation.” While the agent with a claim-right (e.g., the promissee) has the standing to direct both the adoption of an end and the means to it, the benefactor has the authority to “direct the beneficiary only to adopt or maintain the broad end of being grateful.” On Martin’s view, the benefactor does have the standing to issue directives, including demands, but these are directives not to perform a particular action but a broad end, of being grateful. That is, the benefactor has the standing to direct that differs from the promisee’s in scope. Martin contrasts her “scope strategy” with strategies that identify the difference between the promisee and the benefactor in the force of the kind of directive they have the standing to issue.

Agnes Callard analyzes debts of gratitude in terms of the demand to come to value something. Callard argues that such debts come in two types: debts of reciprocation, and debts of appreciation, corresponding to two forms of gratitude: assistance gratitude versus mentor gratitude. Instances of assistance gratitude are those by which the benefactor’s benevolence generates an obligation that governs how the beneficiary acts, thinks, and feels toward the benefactor. By contrast, mentor gratitude generates an obligation that governs how one acts, thinks, and feels about the benefit. Callard distinguishes both assistance gratitude and mentor gratitude from a further form of gratitude that does not generate a debt of gratitude, namely gratitude for gifts, at least when the gift satisfies the norms of gift-giving by treading the line between the overly useful and the useless. “The perfect gift is perfect precisely in that it elicits an affective response that exhausts all the demands of gratitude. It leaves no normative remainder to stand as a ‘debt of gratitude.’ ”

Coleen Macnamara’s chapter asks whether gratitude can be owed for rights-fulfilling conduct (i.e., for benefits that the benefactor has an obligation to give). The standard, but largely unargued for, view is that gratitude is not owed for rights-fulfilling conduct. After considering several baselines relative to which a beneficiary may count as being benefited, Macnamara provides an argument for the view that benefits constitutive of rights-fulfilling conduct do not generate debts of gratitude. She maintains that “requiring P1 to feel gratitude toward P2 amounts to morally forbidding her from representing herself as possessing what morality, itself, has deemed (in a sense to be specified) normatively hers.” Macnamara allays worries about her proposal by discussing the ways in which gratitude may be fitting and of moral significance even when it is not owed.

Cameron Fenton presents a view of filial gratitude that sits between the view that gratitude is owed for basic parental care and the view that it is owed for supererogatory benefits. Fenton argues that “children owe their parents gratitude only when they meet their moral parental duties and raise their children well.” In reply to the objection that a gratitude-based theory of gratitude cannot specify how filial obligations are to be discharged, Fenton outlines what it may be for children to provide their parents with “commensurate benefits” that respond to their parents’ genuine needs. Lastly, Fenton appeals to data measuring unpaid childcare performed by fathers and mothers to argue that filial duties of gratitude are apt to be stronger toward mothers.

Gratitude considered as a Strawsonian reactive attitude is the focus of the next set of chapters. Stephen Darwall advances an account of gratitude as a “second-personal attitude of the heart.” He contrasts attitudes of the heart (which also include trust and love) with the standard “juridical” reactive attitudes (resentment, indignation, and guilt), which reflect interpersonal demands and through which we hold agents accountable for conduct. While juridical reactive attitudes are second-personal in virtue of addressing their targets with implicit demands, gratitude is a reciprocating attitude that communicates to the benefactor that the beneficiary welcomes the benefit and the benefactor’s giving of it. In this way, gratitude, like other second-personal attitudes of the heart, involves “heartfelt giving and receiving.”

In the next chapter, Justin Coates argues that gratitude and resentment are asymmetrical in at least three key ways: in their fittingness conditions, in the norms that govern their expression, and in their value for human relationships. First, Coates defends the view that there is an asymmetry in conditions under which agents deserve praise-manifesting and blame-manifesting attitudes, proposing that this is to be explained by a difference in the degree of moral competence required to deserve blame in contrast to praise. Next, Coates argues that the reasons to express blame-manifesting attitudes are more readily defeasible than the reasons to express praise-manifesting attitudes, like gratitude. Finally, he argues that there exists an asymmetry in the value of praise- and blame-manifesting attitudes, such that “a world with n instrumental goods and the good of being grateful to someone who genuinely deserves gratitude seems better—more worthy of actualization—than a world with n instrumental goods and the good of resenting someone who genuinely deserves resentment.”

Bennett Helm’s chapter focuses on gratitude’s role within the broader rational network of reactive attitudes. According to Helm, this network of reactive attitudes is constitutive of a community of respect, the norms of which are sometimes made determinate through our very attitudes of gratitude and the like. He focuses on an example in which a student is grateful to her teacher for the teacher’s correcting herself after first failing to use the student’s preferred gender pronouns. On Helm’s view, though it is not clear whether the teacher benefits the student, gratitude is responsive to benevolence, understood as one’s being motivated by “recognition respect.” On the assumption that there is indeterminacy in our gender recognition norms, the student’s gratitude can be understood as further committing themselves to, and more determinately delineating, the norm, and inviting the teacher—as well as the community at large—to uphold the norm.

The next pair of chapters address the social neuroscience and social psychology of gratitude. Christina Karns provides a model for understanding how “neural systems may work together to support an experience of gratitude and how the plastic and changeable nature of the brain might be used to promote gratitude.” She begins by offering a conceptual analysis of gratitude similar to what a philosopher might provide, but she uses it to generate hypotheses about the neural processes that underlie the experience of this socially complex and morally implicated emotion. Her assumption is that in such conditions as that the grateful person feels joyful rather than guilty about receiving the benefit from the benefactor and that she feels begraced by, rather than entitled to, the benefit correspond to distinguishable neural and biological processes that can be empirically identified. And she suggests that an understanding of these physiological processes might be useful for helping people to grow in gratitude.

Jack Bauer and Colin Shanahan offer a developmental account of gratitude rooted in a narratival understanding of self identity. According to their account, the traits of existential authenticity and gratitude interact reciprocally over the decades of the lifespan in such a way that individuals become increasingly appreciative of the depth of their interdependency with others. Furthermore, their sense of what it means to “be oneself” evolves from merely not putting on a false façade socially to an incorporation of ethical values that determine the core of being human as their moral tradition construes them. Young people can be grateful, but their gratitude is largely behavioral, consisting in the disposition to “recognize” others’ contributions by expressing gratitude. But as their narrative self-awareness extends and complexifies and ethically deepens over time, they come both to feel and to understand how interlaced their lives and their identities are with those of others, thus rendering their gratitude deeper and more genuine.

The final set of chapters addresses a range of questions concerning gratitude as a virtue and the various ways of manifesting the vice of ingratitude. Sophie Grace Chappell proposes that virtues be divided into those primarily oriented toward good/right action, and those oriented toward good/right feeling. She argues that gratitude should be understood as belonging to the latter class. After providing a self-standing analysis of gratitude, on which gratitude is understood as responsive to generosity, Chappell challenges the standard view that gratitude is not among the Aristotelian virtues. She argues that Aristotle’s treatment of gratitude must be understood against the background of Athenian client-patron relations, and that a more positive Aristotelian stance on gratitude, between equals, can be extracted from Aristotle’s discussion of friendship in the Nicomachean Ethics, read alongside his discussion of gratitude between unequals in the Rhetoric. Chappell concludes by making a case for the appropriateness that we, like St. Paul, “give thanks in every circumstance,” and so makes a case for “cosmic gratitude,” or at least the intelligibility of a mind-set of cosmic gratitude.

Drawing on an example from Graham Greene’s novel Brighton Rock, David Carr addresses the question whether gratitude is a virtuous response to “benefits” that turn on some kind of deceit. The well-meaning person who lies to her friend for the latter’s benefit may strike us as both belittlingly dishonest or as compassionate. To help with the analysis of gratitude for “benefits” based on lies, Carr proposes that we distinguish talk of virtue from talk of morality. On this basis, he argues that we can understand the deceitful friend as a proper object of gratitude (though perhaps not unambivalent gratitude) insofar as she has the other’s interests in mind, even if these are not moral interests.

Liz Gulliford provides conceptual grounds and evidence for thinking that gratitude belongs to a mutually reinforcing set of benevolent virtues, that is, an “allocentric quintet” comprised of generosity, gratitude, forgiveness, compassion, and humility (Gulliford and Roberts 2018). Focusing in particular on the exercises making up Twelve Step programs and the practice of lojong (from the Tibetan Buddhist tradition), Gulliford’s chapter outlines how spiritual and self-examination practices promote cross-pollination from one allocentric virtue to another within a person’s character. Gulliford concludes with “some suggestions as to how psychological interventions to promote strengths of character might be enriched by fostering mutually reinforcing strengths, rather than targeting virtues individually.”

Tony Manela’s chapter focuses on the various ways in which one can fall short (or long) of the virtue of gratitude. After providing an account of the virtue of gratitude as a “meta-disposition” or the “disposition to perceive benevolence and to form the proper grateful beliefs and affective and behavioral dispositions vis-à-vis the source of that benevolence,” Manela provides a taxonomy of the ways one can fail to be a grateful agent. According to Manela, there are three ways an agent can fail to be properly grateful: he can fail to be properly sensitive to evidence of benevolence (failures of attunement); he can fail to establish the proper beliefs and dispositions when gratitude is called for (failures of establishment); and he can fail to preserve those beliefs and dispositions for a proper or reasonable amount of time (failures of duration).

In the volume’s final chapter, Robert Roberts explores the emotional depth of Charles Dickens’s Bleak House to illustrate how gratitude must be understood in its connection with other virtues, especially generosity, but also humility, justice (injustice), friendship, and practical wisdom. By attending to the characters of John Jarndyce, Esther Summerson, and Harold Skimpole, Roberts maintains that it is only in combination with the concept of justice that the notions of generosity (in contrast to liberality, which construes gratitude as servile) and gratitude are intelligible. The generosity-gratitude dynamic is especially central to Roberts’s contribution as he, following Dickens, identifies these as complementary virtues: gratitude is a proper or canonical response to genuine acts and attitudes of generosity and such generosity is satisfied and completed, so to speak, by expressions of gratitude. Roberts proposes that we call this pair the virtues of grace, since both are about gifts—giving and gracious receiving.

References

Berger, Fred (1975). “Gratitude.” Ethics 85: 298–309.

Camenisch, Paul (1981). “Gift and Gratitude in Ethics.” The Journal of Religious Ethics 9: 1–34.

Carr, David (2013). “Varieties of Gratitude.” Journal of Value Inquiry 46: 17–28.

Gulliford, Liz and Robert C. Roberts (2018). “Exploring the ‘Unity’ of the Virtues: The Case of an Allocentric Quintet.” Theory and Psychology 28: 208–226.

Manela, Tony (2015). “Obligations of Gratitude and Correlative Rights.” Oxford Studies in Normative Ethics 5: 151–170.

Manela, Tony (2016). “Gratitude and Appreciation.” American Philosophical Quarterly 53(3): 281–294.

McAleer, Sean (2012). “Propositional Gratitude.” American Philosophical Quarterly 49(1): 55–66.

McConnell, Terrance (1993). Gratitude. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

McConnell, Terrance (2018). Gratitude’s Moral Status. Unpublished manuscript.

Morgan, B., L. Gulliford, and K. Kristjánsson (2014). “Gratitude in the UK: A New Prototype Analysis and a Cross-Cultural Comparison.” The Journal of Positive Psychology 9: 281–294.

Roberts, Robert C. (2004). “The Blessings of Gratitude: A Conceptual Analysis.” In The Psychology of Gratitude, eds. R. A. Emmons and M. E. McCullough, pp. 58–78. New York: Oxford University Press.

Roberts, Robert C. (2015) “The Normative and Empirical in the Study of Gratitude.” Res Philosophica 92(4): 883–914.

Roberts, Robert C. (2016). “Gratitude and Humility.” In Perspectives on Gratitude: An Interdisciplinary Approach, ed. David Carr, pp. 57–69. New York: Routledge.

Seneca (2011). On Benefits. Trans. M. Griffin and B. Inwood. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Strawson, Peter (1962/1974). “Freedom and Resentment.” In Freedom and Resentment and Other Essays, pp. 1–25. London: Methuen & Co Ltd.

Part I: Reasons and Action

Chapter 1: Gratitude: Generic versus Deep

Hichem Naar

The Elusiveness of Gratitude

In this chapter, I argue that gratitude is not necessarily affective or motivating. Against a common trend in recent philosophical treatments of the notion, indeed, I argue for the introduction of an important but neglected kind of gratitude that is simply a matter of believing that one has been benefited by a benevolent benefactor. I will call this non-affective, non-motivating kind of gratitude “generic,” and the kind—taking center stage in the literature—that is affective and motivating, “deep.” After defending the distinction, I explore the connection between these kinds of gratitude.

Suppose I asked you to recall as many people as you can to whom you are grateful. How many would you be able to bring to mind? And how long would it take you? How difficult is the task? Is it easier than bringing to mind people you love, or harder? My experience is that it is much harder to bring to mind people I am grateful to. Besides a couple of obvious answers—which may not have been obvious to me until I actually tried—I find it a daunting task to come up with names of people to whom I am grateful. For one thing, many people have benefited me in the past; for another, rarely anything as deep as a state of love was formed as a result of having been benefited from them. Nonetheless, there may appear to be a fact of the matter as to whether, for any given person X, I am grateful to X for having done something for me. The problem is that it often takes some effort to come up with a satisfactory answer to the question “Whom are you grateful to, and why?”, giving the impression that, as one is thinking deeply about one’s past, one is not really grateful to the people one will ultimately cite. When you are pondering over whom you are grateful to, are you engaged in a bit of introspection, or are you, quite literally, making up your mind as to whether you are, or should be, grateful to this or that person? The fact that it takes so much effort—and what looks like genuine deliberation—to come up with names may suggest that, prior to being asked the question, you were not really grateful to the people you were hard put even to remember.

Things may look a bit less alarming when you don’t have the initial task of remembering a specific person. Suppose I ask you, for any given person X, whether there is anything for which you are grateful to X. You would probably come up with a definite answer much more easily. Since you now remember X, it is much easier for you to think of the various ways X may have contributed to your life. Perhaps X has helped you carry your furniture when you moved into your new apartment. Or perhaps X has often been there when you needed advice on relationships. Or perhaps X bought you a nice meal last weekend. In any case, provided the relevant person has already been brought to your attention, it is rather easy to remember what he may have done for you which appears to render gratitude appropriate. In such cases, one can then declare “I am grateful to X for A.” Although it might have been easier to come up with an answer to the question “Are you grateful to X?” than it is to answer the question “Whom are you grateful to?”, there remains the suspicion that one’s answer is not really revelatory of a prior state of gratitude. Indeed, if no one had asked you this question, you probably would never have given much thought to the fact that the person has benefited you. Perhaps, then, gratitude is such as to be held on the basis of effortful conscious deliberation. If true, this would imply a fairly robust form of skepticism about gratitude formed spontaneously and effortlessly, of the sort we take to be paradigmatic, the sort of gratitude we take to be revealed rather than created when reflecting on the impact other people have had on one’s life, and therefore the sort of gratitude the knowledge of which can be a matter of genuine discovery.

Perhaps, however, this sort of skepticism should not be accepted just yet. Suppose I asked you, not whether you are grateful to X for having done something or other (that you would then need to think about), but whether you are grateful to X for having done A in particular—thereby sparing you the trouble to search for ways you may have benefited from X in the past. It appears that the answer will be extremely easy to come by. Suppose you believe you were benefited by X’s action, and also believe that X’s motives were good. I can easily imagine you reply: “Sure, I’m grateful.” And this could be repeated for any agent-action pair I give you. For any such pair, it seems you will immediately know what answer to give. If you don’t believe you were benefited by a person, for instance, then you are highly likely to answer the question “Are you grateful to X for A?” with a firm “No.” By contrast, if you believe you were benefited by X, that X did something good for you, then arguably you are just as likely to give the positive answer. It appears, then, that there is a fact of the matter whether you are antecedently grateful to a person for something they have done, a fact that you are able to access if prompted in the right sort of way. Maybe you were not aware that you were grateful before being prompted, but the immediacy with which you are able to answer the question suggests that your gratitude was there all along, waiting to manifest itself.[4]

But what exactly was “there all along” that would require you to get all the relevant information in full view in order for the gratitude to be triggered? I don’t need to give you the name of someone in particular in order for you to tell me whom you love spontaneously and effortlessly. So why do I need to do this to have a spontaneous and effortless answer to a query about whom I am grateful to? I think this has to do, not with the fact that I may have failed to be grateful prior to being asked the question, but rather with the fact that gratitude is, in many cases, rather cheap, requiring something much less sophisticated than contemporary accounts of gratitude claim it requires. As I argue in the section “Being a Grateful Person: Gratitude Qua Virtue,” although there is a fact of the matter whether you are grateful at a particular time to a person for having benefited you, this fact is often hard to pin down precisely because it is trivial—in particular, it is a trivial consequence of having further, temporally persisting, and often dormant, mental states. Calling these mental states to mind, however, can have psychological consequences that are not trivial, which is why it may be important to attend to the various ways other people have benefited us. In particular, doing so might lead to a deeper form of gratitude of a sort associated with the affective and the motivational. In section “Deep Gratitude,” I discuss this sort of gratitude, which I call deep gratitude, to be contrasted with the generic gratitude of the sort discussed in the previous section. I argue that, in addition to the mental states involved in generic gratitude, deep gratitude involves an essentially affective-cum-motivational element, and I tackle the question of what turns a merely generically grateful person into a deeply grateful one. In the section “When Is Deep Gratitude Appropriate?” finally, I ask what might make deep gratitude appropriate over and above generic gratitude. As we will see, it is difficult to draw a principled distinction between appropriate and inappropriate instances of deep gratitude, and skepticism about conditions of appropriateness for deep gratitude is difficult to avoid.

Generic Gratitude

In presenting a previous version of this chapter to various audiences, I have had many comments, some very helpful, others a bit less so. In any case, I take myself to have benefited from the people who reacted to the chapter. Also, I’m assuming that many of these people really wanted to help me improve the paper, and that they didn’t do it for any self-interested ulterior motives, or at least not just for these reasons (McConnell, 1993). For simplicity, I’ll call the attitudes in a benefactor that appear to be presupposed by the grateful beneficiary “benevolent attitudes,” leaving it open what exactly these are.[5]

But am I grateful to them, now, several weeks or months after receiving the comments, comments my benefactors may not even remember? At first sight, it may appear that I am not genuinely grateful to them. For one thing, nothing in my behavior appears to suggest that I am grateful to them. To be sure, I may actually use some of the comments I received to improve the chapter. Although this might make my commentators happy, should they come to realize the impact they had on the chapter, I may do so in a way that disregards completely the origin of these comments. At least while I am writing the paper, what matters is that I improve it, and if the comments I received may help me do that, then I will use them. Otherwise, I won’t. If I don’t, however, this doesn’t mean that I am not really grateful to my commentators.

Perhaps, however, we should look at what I am disposed to feel and do with respect to my commentators. But then again, I don’t find myself experiencing anything in particular when I think about the moment I received the comments, or my commentators themselves. I might find the comments useful in and of themselves, but I might not feel anything toward the commentators who gave them. Neither am I particularly disposed to help them should they need some comments. The next time I see any of them talk, I do not think I will be particularly inclined to give a comment over and above my prior inclination to give comments whenever I find it relevant to do so. I am not, in other words, disposed to return the benefit.

To be sure, I might happen to feel differently about the various people who reacted to my chapter. I might like, or take pleasure in the company of, some more than others. I might want to keep in touch with some but not others. I might even appreciate the feedback given by some people more than I appreciate the feedback of others. And there might be commentators I actually feel, for various reasons, negatively about. And some reasons might have to do with the comments I received. Perhaps someone expressed a forceful objection to my argument, which, not knowing how to answer it, led me to form an irrational dislike of that person.

But what I happen to feel about my commentators need not be indicative of an underlying state of gratitude that I formed in response to the comments I received. I think that I am genuinely grateful to the people who reacted to my chapter, a fact whose only external sign will probably be an acknowledgment in a footnote, and that I am grateful to all these people equally. In expressing my thanks in a footnote, I take myself to be expressing the same kind of attitude to both those people I generally feel positively about and those people I generally feel negatively about. And, assuming talk of “strength” is appropriate here, such attitude may have the same strength in both cases, regardless of what I happen to independently feel. In addition, the attitude expressed need not lead me to be motivated one way or another to benefit my commentators.[6]

At this stage, one might object that I am not really grateful to my commentators if I am not disposed to benefit them in return if the occasion presents itself or do not feel a certain way with respect to them (e.g., McConnell, 1993). If this is right, then my acknowledgment would not be an expression of gratitude. At best, the objection goes, this would simply be compliance with a norm of etiquette.[7] Just as saying “Thanks” when someone is holding the door for us does not imply that I am grateful to that person for doing so, acknowledging the help of someone in a footnote need not indicate any attitude of gratitude toward her. In doing so, I may just be doing what’s conventionally expected of me, and nothing more than that, especially if I am not disposed to return a benefit or to feel in a certain way in response to having been benefited.

Suppose it is true that my “thanks” in response to someone holding the door is not a genuine expression of gratitude, but rather mere compliance with a norm of etiquette. Does my thanking my commentators have the same structure such that it is plausible that I am not expressing any sort of gratitude in this case either? I think that there are at least two differences between the two cases that would explain why I should be grateful to my commentators but not grateful to the person who holds the door for me. First, there appears to be a social norm such that, if you are entering a building and someone is not too far behind you, then you should hold the door for them. It is therefore expected that we hold doors for others when this condition obtains. In fact, it is often because of our perception of this expectation that we hold doors, and not because we want to benefit the person behind us. By contrast, giving a comment at a conference is not expected in this way. There is no social norm enjoining us to give a comment when attending a talk, especially when the number of people is large enough so that not everyone is going to have a chance to give a comment anyway. In giving a comment at a conference, to a certain extent one thereby goes out of one’s way in a way that someone holding a door for us doesn’t.[8] There are, therefore, differences in what motivates the two actions that would explain why I should be grateful for only one of them, differences that would be reflected in my attitudes toward the relevant agents.[9] Second, it is not quite clear that having the door held for one is significant enough to be called a “benefit” at all. It would clearly count as a benefit if it were somewhat burdensome to open the door ourselves. Since for most of us it is not, calling it a benefit is a bit of a stretch. At any rate, since I don’t believe that the door’s being held for me is a benefit, it is pretty clear that I am not grateful to the agent.

I have pointed to two differences between holding the door for someone and giving a comment at a conference that appear to indicate that I should be grateful only to my commentators. The two situations are therefore normatively different. One might insist, however, that the sort of gratitude called for in the conference case should involve certain dispositions—affective and motivational—that I don’t have, implying that I am not genuinely grateful. Perhaps, indeed, I should be disposed to give a comment in return, or to feel a certain way about my commentators. If I am not so disposed, the thought goes, I am not really grateful to them.

I have two responses to this argument to the effect that, given my dispositions, I am not genuinely grateful to my commentators even if I sincerely judge that I am. First, we should distinguish between the grateful response that one should form in a given context and the grateful response that one actually forms. Perhaps I should have the relevant sort of dispositions to be appropriately grateful to my commentators. This, however, does not entail that I am not grateful if I lack any of these dispositions. To appreciate this point, consider a situation in which a person merits the deepest gratitude there could ever be for an extraordinary benefit conferred on one (the person saved one’s life, say). It seems that one should be extremely grateful to that person, and thereby should be disposed to do much more than say “thanks.” Suppose, however, that one is in fact disposed to do a bit less than what the benefit calls for. Is one ungrateful? In a sense, yes. But it may still be true that one is grateful, albeit not as grateful as one should be. Perhaps, then, I am genuinely grateful to my commentators, albeit not as grateful as I should be.[10] If this much is accepted, however, then gratitude of the sort I take myself to have toward my commentators really exists, implying that gratitude does not necessarily involve the rather complex and deep dispositions— involving both motivational and affective aspects—posited in the contemporary literature (Berger, 1975; McConnell, 1993). Second, it is not even clear that I should be disposed to act and feel in certain ways to be appropriately grateful to my commentators. To be sure, I may have a sense of indebtedness, or may feel positively about my commentators, but this does not seem to be something the situation calls for. I would not be open to criticism if I failed in these respects. Nor would I be open to criticism if I did not give a comment while attending a talk delivered by any of my commentators. All the situation appears to call for, when it comes to my behavior, is a public acknowledgment of the help they have provided.

But in order for this acknowledgment to be a genuine expression of gratitude, rather than (say) compliance with a norm of etiquette, there still must be in my psychology something that makes it true of me that I am grateful, and that I have been grateful all along. Intuitively, I have been grateful ever since I have benefited from them and the acknowledgment was simply the occasion to express that gratitude. In addition, it seems that the acknowledgment does not mark the end of my gratitude, as if my gratitude was something, like thirst, to be quenched. But, as pointed out earlier, it shouldn’t be always easy for me to bring the relevant people to mind.

To get to my account of the nature of gratitude of this minimal, generic sort—which I call generic gratitude—I’d like to make explicit what I take to be an attractive general conception of gratitude. I think that gratitude is a particular mode of recognition of the impact other people have on one’s life and of the quality of their character.[11] In being grateful, I recognize that certain people have a certain concern for me—or at any rate, that they had such concern at some point in the past—and that it is such concern that motivated them to benefit me. I recognize the good things they do for me out of a concern of this sort. If one recognizes such things, then one can be truly said to be grateful. There are, however, different ways to recognize the good others bring to our lives in a way expressive of benevolent attitudes such as a concern. A particularly extreme way to do this is to commit oneself to do everything one can to improve their lives. In response to a (perhaps extraordinary) benefit I receive, I may form the disposition to be on the constant lookout to help my benefactor. Another form of recognition may involve only having a certain concern for the well-being of one’s benefactors, although not one that will lead us to constantly try to benefit them. Still another form of recognition may involve being disposed to return a benefit.

Now, I think that there is a clear sense in which I recognize the good that my commentators brought to my life, a recognition I express by thanking or acknowledging them in my chapter.[12] This recognition, I have suggested, does not necessarily involve any particular sort of motivational or affective disposition. What must be true of me, then, for me to recognize the value of what my benefactors have done for me if not being disposed in these ways? All that seems needed, I contend, is that I hold certain beliefs about the benefactor and the benefit I received. In particular, I should believe that the thing my benefactor has done was a benefit and that it was motivated by benevolent attitudes.[13] Having a belief of this sort, by itself, is a way of recognizing that you have done something good for me out of attitudes that indicate that you have a benevolent concern for me. My sincere “thanks” or acknowledgment is a way of showing you that part of my conception of you—the part that I get from the fact that you benefited me (from the relevant benevolent motives).[14] Although more details about the cognitive states involved here should be ultimately given, I think that, if gratitude is a recognition of some sort, and if recognition of this sort can be realized by cognitive states of the sort just alluded to, then there is a kind of gratitude—generic gratitude—which someone has in virtue of holding certain beliefs, and that is appropriate only if such beliefs are in fact true.[15] It is important to notice that, on this account, generic gratitude is not something over and above the relevant beliefs. Rather, it is a logical consequence of holding these beliefs. If one holds the relevant beliefs, one is thereby grateful in the generic sense.

This account of generic gratitude seems to explain why I can be grateful to my commentators for a long time, including long after I have publicly acknowledged their help. So long as I hold the relevant beliefs, then it is true of me that I am grateful to my commentators. The account also explains why complete failure to remember being benefited by a certain person will imply a failure to be grateful to them, as presumably such a failure would imply the absence of some of the relevant beliefs. How about a temporary failure to remember? Since such a failure is compatible with the presence of the relevant beliefs, and it often takes a little bit of reflection to bring to mind the content of our beliefs, the account implies that we can be grateful, at a given time, to certain people even if we would not remember them if prompted at that time. The account, therefore, allows cases in which reflection is needed to know whom we are grateful to, thereby avoiding skepticism about the sort of gratitude we spontaneously and effortlessly form (which will often be unconscious, if the relevant beliefs are unconscious) as a result of benefiting from others.

I have argued that gratitude comes in both generic and non-generic forms in virtue of the fact that gratitude is a mode of recognition of other people, their character, and the things they do for us. Given that a belief of a certain sort is sufficient to constitute this recognition, such belief is sufficient to count as gratitude (or, rather, to make it true that one is grateful). I have not given reasons to believe this inclusive conception of gratitude as recognition, however. Neither have I given any argument to the effect that, if the account of gratitude as recognition is wrong, an inclusive account is preferable to a non-inclusive one. Instead of giving an argument for the account of gratitude as recognition in particular, though, I will point to three reasons for preferring an inclusive conception of gratitude—one that allows the holding of merely cognitive states to count as sufficient for gratitude. First, I think that an inclusive account better accommodates our ordinary self-attributions of gratitude. It takes at face value my sincere judgment that I am grateful to my commentators. It also takes at face value the judgment of those who take themselves to be grateful to others for extremely minor benefits. I may be grateful to my friend for buying me breakfast last weekend. It seems, indeed, that if you believe someone else has benefited you—even in a minor way—out of benevolent attitudes, you will thereby be disposed to sincerely assent to a proposition of the form I am grateful to X for A, regardless of any other attitude you might have toward your benefactor. Second, and relatedly, an inclusive account of gratitude gives a proper account of those cases of minor benefit such that it is clear that the beneficiary has pretty much nothing to do. Most advocates of non-inclusive accounts of gratitude would presumably agree that being benefited out of benevolent attitudes is sufficient for gratitude to be called for, and this regardless of how much one was benefited. It turns out that most of the ways other people benefit us do not appear to call for any deep change in motivational or affective profile, much less to generate a “debt of gratitude.” The advocate of the non-inclusive account would therefore be forced either to deny that it is being benefited simpliciter that matters or deny that the relevant “benefits” are genuine benefits. Neither option, however, is particularly promising. Third, the inclusive account emphasizes that the evaluative beliefs other people have about us and about what we do already matter, and that they need not feel anything toward us to properly acknowledge us. If my feelings about you are significant in a way that does not derive from their disposing me to do certain things, I don’t see why my beliefs about you cannot be significant in a similar way. We certainly care about what others think of us, we care about their conception of us, and we seem to care about it for its own sake. This suggests that we attach some significance to evaluative thought over and above feeling and action. Although I do not have an account of the normative significance of thought, I find it hard to deny.

To conclude this section, gratitude is often elusive because our evaluative beliefs about others are elusive. In many cases, it takes some effort and reflection to come to know what we think of other people and their actions. The fact that beliefs do not seem to be as phenomenologically salient (if they are so at all) as emotions and motivations may explain why philosophers tend to construe gratitude nongenerically, that is, as necessarily involving precisely those dispositions (motivational and affective) whose manifestation is very difficult to ignore. If the argument in this section is on the right track, this tendency should be avoided if we want to do justice to the full spectrum of ways we can properly recognize the impact other people have on us.

Deep Gratitude

At first sight, it might be thought that gratitude is the response one forms after one has formed certain beliefs about the world—in particular, after having formed the belief that one has been benefited and that the benefit was given out of benevolent attitudes (or some such). If my argument in the previous section is on the right track, it is a mistake to think that one is not yet grateful when one has formed the relevant beliefs. As I have argued, gratitude is already present when one has those beliefs. In other words, holding the relevant beliefs is sufficient for gratitude.

This claim has an important implication, namely that affect and motivation are not necessary for gratitude. It is not true that gratitude implies a certain kind of goodwill toward one’s benefactor (contra Herman, 2012; Walker, 1980–1981), or any sort of affective disposition (contra Berger, 1975; Camenish, 19801; McConnell, 1993; Roberts, 2004). One can be grateful without having these dispositions, or at any rate without having dispositions that one didn’t already have before being benefited. Neither must one be inclined to benefit one’s benefactor to be grateful. Gratitude, therefore, does not entail reciprocity (contra Manela, 2015, Section 3.4.1). Such descriptive claims have normative counterparts. It is not the case that to be appropriately grateful, one should have rather deep affective and motivational dispositions. If gratitude was indeed called for in response to receiving comments at a conference—which I think it was—what would be called for would be no more than the holding of certain beliefs and, if the occasion arises, a public acknowledgment of the benefit one received.

Now, not all cases of gratitude will be “generic.” In fact, the clearest cases of gratitude are those that will also involve the sort of affective or motivational disposition often taken by philosophers to be essential to gratitude. The paradigmatic case of gratitude, one might argue, is not generic but deep. It is deep in the sense that it plays a rather pervasive role in one’s psychology. A deeply grateful person would not only hold certain beliefs about her benefactor but would also be disposed to feel and be motivated in ways characteristic of gratitude. Such a person would also be disposed to emphatically express one’s gratitude with claims such as that she is deeply grateful to X, or that she will always be grateful to X, for something X has done—something the generically grateful person would not typically say.[16]

I think deep gratitude—by contrast with generic gratitude—is essentially affective.[17] What this means is that it has a strong connection to the emotions. At first blush, we might take deep gratitude to be an emotion. This claim, although plausible, should be taken with a certain degree of care. For it is quite common in the literature on emotions—both in philosophy and the sciences—to take emotions to be episodic mental states, that is, mental events of some sort that are typically experienced for a relatively short period of time. On this understanding of the notion of emotion, the idea of gratitude as an emotion would be understood as about something we experience over a short period of time. Although there might exist a distinctive feeling of gratitude (a claim that itself may be doubted), gratitude as an attitude appears to be something that endures in a way that a mere emotional episode does not. As noted previously, one may be grateful for a really long time, even a lifetime. Deep gratitude, therefore, should be understood as an emotion in a rather different sense, that of an affective attitude or sentiment (Naar, 2018).[18] Just as one can love someone for a lifetime—even if it is not the case that one will constantly feel a particular way about the individual over a lifetime—one may be deeply grateful to someone for a lifetime.[19] Why should a sentiment be conceived as affective? Presumably, this is because it is connected to affective episodes in some way. Elsewhere, I argue that the nature of this connection is dispositional (Naar, 2018, see also Helm, 2001). Love, for instance, is (inter alia) a disposition to experience a certain range of emotions in various situations (Naar, 2013). Similarly, if deep gratitude is a sentiment, it will involve a disposition to experience various emotions in relevant situations.[20]

Several questions could be asked about the proposal just outlined. One might ask how we should understand the notion of disposition at play here. For instance, should it be understood in realist or antirealist terms? Although I have a view on this (Naar, 2013, 2018), I think that it is not crucial for my purposes, which is to propose a plausible distinction between two ways one can be grateful and an account of how these two sorts of gratitude are related. One might also ask how gratitude differs from other sentiments such as love. In particular, one might wonder how deep gratitude and love differ in their manifestations. Admittedly, I do not have an answer to this question.[21] In fact, I suspect that a fully satisfactory account is difficult to come by. The reason is that both deep gratitude and love appear to be species of caring. Both attitudes, indeed, appear to dispose their bearer to feel positively when things go well for the target and negatively when things go badly, and both attitudes appear to involve an inclination to advance the interests of the target. This set of dispositions, it seems, is sufficient for the subject to be properly said to care about the target, at least in some minimal way.

If true, the claim that deep gratitude is a species of caring raises important descriptive and normative questions. On the one hand, we might ask what explains that a subject could come to care about a benefactor, as opposed to merely holding the beliefs constitutive of generic gratitude as a result of having been benefited. On the other hand, we might ask what could make deep gratitude appropriate over and above generic gratitude. Why should one come to care about a benefactor in some cases and not others? Why, in other words, should being deeply grateful to someone be an appropriate way of recognizing the impact they have had on our lives? In the rest of this section, I will briefly spell out what I take to be the basic structure of deep gratitude, thereby going some way toward answering the descriptive question. In the next section, I will tackle the question of what might make deep gratitude an appropriate response to a benefactor.

The question of what explains the formation of deep gratitude is an instance of the question of what explains the formation of a special concern for someone. Why does one come to care about a person as opposed to many others one doesn’t particularly care about? It appears that having certain beliefs about them may not be sufficient. I am fully aware that there are really wonderful people out there. I might even believe—perhaps on the basis of testimony—that that person over there is wonderful. Yet, believing this won’t motivate me to care about them in the way I care about my friends. What would be needed, then, for me to be so motivated? Presumably, I would need to interact with them over a certain period of time. This would allow me to learn more about the particular way the person is wonderful. But even then, I might not be motivated to come to care about them the way I care about a friend. I think that what I learn about the person needs to resonate with me in some way. To come to care about them, indeed, what happens between us should bear on my own likes and dislikes, my desires, my personality, and my cares, namely traits I have had before meeting the person. The nature of this “bearing” relation is difficult to specify, but it is clear that without the addition of such factors, we won’t be able to fully explain why I come to care about some people rather than others.[22]

The structure of deep gratitude that appears to emerge involves two main elements. First, one must form an adequate conception of the benefactor, the considerations that motivated her, and the benefit, something I’ve suggested should count as gratitude of a certain—generic—sort. When receiving comments at a conference, I formed certain beliefs about my commentators, their motivations, and the benefit I received. But I am not disposed to feel and act in ways characteristic of deep gratitude with respect to most people who gave me comments. Suppose, however, that one of the comments somehow bears on my cares. Perhaps one innocuous comment led me to the discovery of an important insight, the sort of thing I value greatly. In such a case, the fact that the comment has bearing on what I care about will make it much more likely for me to be deeply grateful to the person who gave it. Deep gratitude, therefore, is likely to occur when (1) one has the beliefs constitutive of generic gratitude and (2) some aspect of the benefit one has received—as represented by the beliefs mentioned in (1)—bears on one’s cares, desires, likes, and so on.