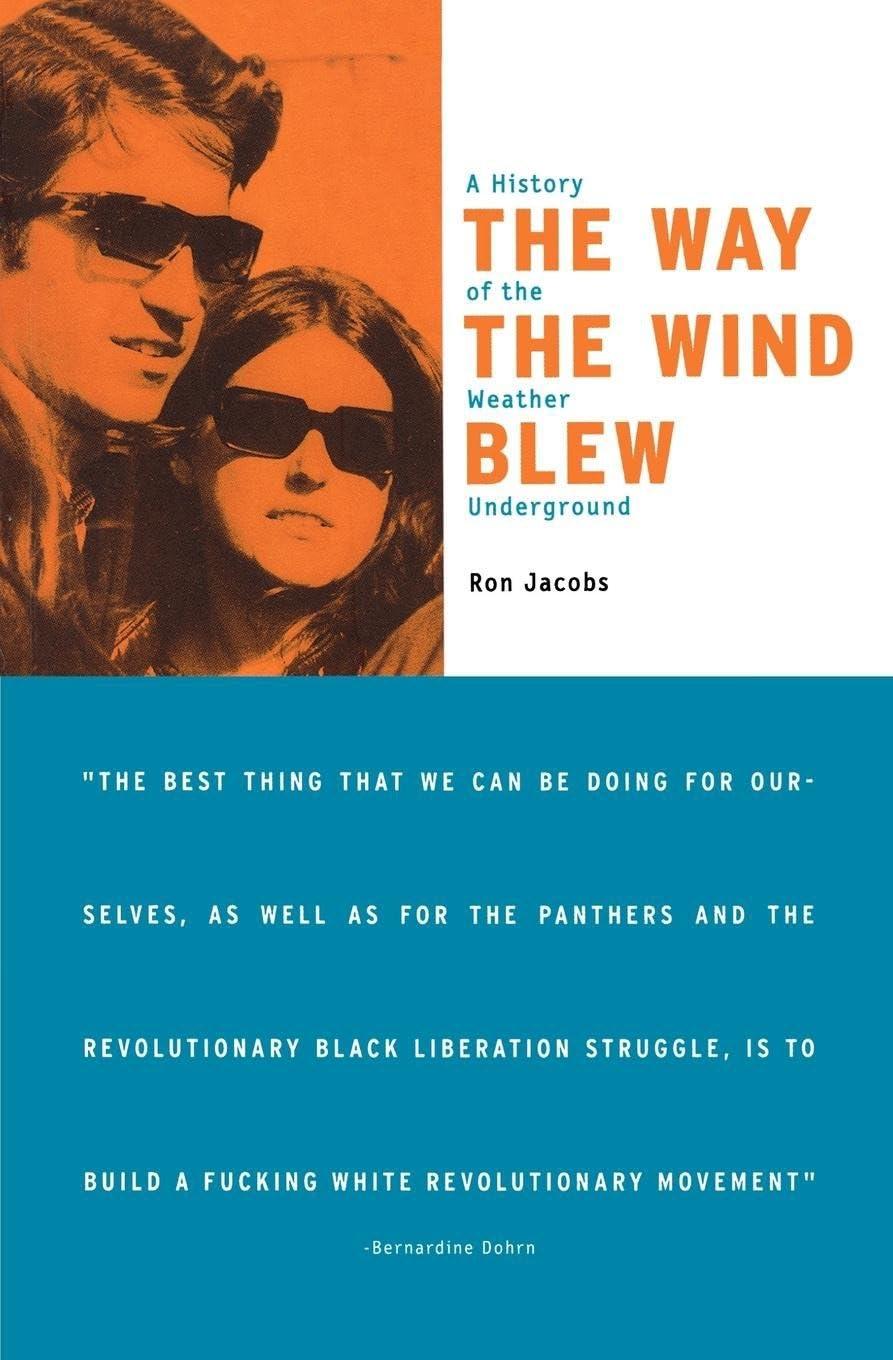

Ron Jacobs

The Way the Wind Blew

A History of the Weather Underground

2. Weather Dawns: The Break and the Statement

3. Into the Streets: Days of Rage

4. Down the Tunnel: Going Underground

5. Women, The Counterculture, And The Weather People

7. A Second Wind? The Prairie Fire Statement

Preface

I first became aware of Weatherman in the fall of 1970, after opening a copy of Quicksilver Times and reading about the group’s assistance in Timothy Leary’s escape from a prison in California. Although I personally preferred the antics of that other psychedelic prankster Ken Kesey, the fact that a political organization had aided the unreservedly apolitical Leary to escape fascinated me.

Then, at high school on a US military base in West Germany, where I was involved in organizing against the Vietnam war, I began reading as much as I could about Weatherman and its history. I found its politics difficult to understand but always admired its style and its ability to hit targets which in my view deserved to be hit. When I returned to the US after high school I floated in and out of organizations on the Left, where the presence of Weather was always felt, as an example both of commitment and of the necessity to organize deep popular support. My own political path has led me to shun military actions in favor of massbased organizing, but I believe Weather’s insistence on an anti-racist and anti-imperialist (and, belatedly, anti-sexist) analysis was fundamental to my political development.

The New Left was constantly changing, reacting to events in the world and in the movement itself. Many of today’s critics view the Students for a Democratic Society of late 1968 and early 1969 (and afterwards) in relation to its original intentions as expressed in the Port Huron Statement. When they write about its history after the June 1969 convention, they often do so in terms of a betrayal of the ideals of the organization before it split. It is my contention that what happened at that convention and afterwards was not so much the end of the New Left as yet another sharp turn in the history of the Left itself. Another tendency in many writers is to relate this part of its history with an emphasis on the personalities involved and not the politics. While they are arguably intertwined, it is my hope that this text is primarily a political history of Weatherman, and not merely an account of personalities.

*

Every attempt has been made to ensure that all citations are complete. However, given the nature of the North American underground press, it has not always been possible to provide complete information, especially in the case of specific page numbers. Also, in the early chapters of the text, I refer to the New Left as such. However, as the lines between the New Left and Old Left become blurred, I use the more general term, the Left.

1. 1968: SDS Turns Left

I send you, my friends, my best wishes for the New Year 1968.

As you all know, no Vietnamese has ever come to make trouble in the United States. Yet, half a million troops have been sent to South Vietnam who, together with over 700,000 puppet and satellite troops, are daily massacring Vietnamese people and burning and demolishing Vietnamese towns and villages.

In North Vietnam, thousands of US planes have dropped over 800,000 pounds of bombs, destroying schools, churches, hospitals, dikes and densely populated areas.

The US government has caused hundreds of thousands of US youths to die or be wounded in vain on Vietnam battlefields.

Each year, the US government spends tens of billions of dollars, the fruit of American people’s sweat and toils, to wage war on Vietnam.

In a word, the US aggressors have not only committed crimes against Vietnam, they have also wasted US lives and riches, and stained the honor of the United States.

Friends, in struggling hard to make the US government stop its aggression in Vietnam, you are defending justice and, at the same time, you are giving us support.

To ensure our Fatherland’s independence, freedom, and unity, with the desire to live in peace and friendship with all people the world over, including the American people, the entire Vietnamese people, united and of one mind, are determined to fight against the US imperialist aggressors. We enjoy the support of brothers and friends in the five continents. We shall win and so will you.

Thank you for your support for the Vietnamese people.

Ho Chi Minh[1]

The story of the Weather organization begins in 1968. From the Tet offensive of the national liberation forces in Vietnam to the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., to the uprisings in France and at Columbia University, to the invasion of Czechoslovakia and the Chicago Democratic convention — the events of that year created the political space for the emergence of this New Left organization — one arguably without precedent in United States history.

Within the United States the anti-racist and anti-war movements constituting the New Left, which had been growing in leaps and bounds since the late 1950s, took on thousands of new members in 1968, and began to develop a more radical approach in their analysis and activities. These approaches were partly reactions to the intensification of the war in Vietnam and a belief that a new “fascism” was on the rise in the United States. This fascism was manifested politically in a new concern over law and order and experienced socially in the increasing use of brutal police methods during protests and insurrections. For example, during the black rebellion following King’s murder, Mayor Richard Daley of Chicago ordered the police to “shoot to kill” any looters.

The response of the New Left was to develop a more coherent stance toward the liberal-conservative establishment. No longer were particular racist policies or murderous acts protested; instead the New Left sought to acknowledge the totality of social and political injustice in the US, a system that it came to label as imperialist.

Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) — the national organization which, partly by design and partly by default, carried the mantle for the New Left in the United States — was at the forefront of this new perspective. The organization’s paper, New Left Notes, became the forum for a discussion of how to combat US imperialism, in theory and practice — a discussion that sometimes became acrimonious and divisive. Within SDS itself an older, sectarian Marxist-Leninist group — then called the Progressive Labor Party but soon to shorten its name to Progressive Labor (PL) — formed its own power base[2]. Anti-nationalist and anti-Soviet, PL recruited mostly among students from the elite universities on the west and east coasts. It received its broadest support in 1965–7, when it formed the May 2nd Movement (M2M) against US involvement in Vietnam — the only national organization of its kind at the time. Its members’ ability to manipulate discussion and votes at SDS national conventions and locally, and their knowledge of Left rhetoric and theory, enabled them to hold more power than their numbers warranted. Although a marginal faction at the beginning of 1968, by year’s end PL had, if nothing else, created a division within SDS so deep that the rift between those who supported PL and those who didn’t was irreparable.

In the January 15, 1968 issue of New Left Notes an article appeared entitled “Resistance and Repression.” The article was an attempt to move SDS and its actions beyond “the point [where] it became necessary to define and confront the institutions of American aggression in Vietnam — [to] the point when it became necessary to start building a movement which could take over those institutions. Earlier demonstrations had “enabled [the movement] to show our strength, but did not give us forms to use that strength.”[3] The events of 1968 and beyond were to change this, as SDS began to see itself as a revolutionary movement. No longer would the New Left merely react to America’s exploitative and racist system, but, instead, it would provide an alternative vision.

On the evening of January 11, 1968, outside the Fairmount Hotel on San Francisco’s Nob Hill, a picket line of hundreds marched on the sidewalk shouting slogans and bearing signs stating their opposition to US aggression in Vietnam. Inside the hotel Secretary of State Dean Rusk, one of the war’s principal architects and apologists, addressed members of San Francisco’s political and economic elite. As the crowd of picketers grew in size and volume, police in full riot gear amassed at one end of the block. Then, suddenly, the police were on top, around and among the demonstrators. With clubs flailing, the officers grabbed and beat protestors, before throwing them in the back of waiting paddy wagons. The initial responses of the demonstrators “were shock, amazement, fear, and then, anger.” According to Karen Wald, a reporter for New Left Notes, “the fear was too great for any attempt to rescue … anyone who was grabbed.” The following day, Wald realized, like many of her fellow activists, that this was repression at its most raw. The days were “long gone when you had to be seeking arrest … in order to be busted.” No longer, she wrote, would the state allow forms of protest it did not agree with. No longer would the state treat those whom it considered dangerous as anything less than dangerous.[4]

Those who shared this opinion concluded that the only effective protest action was one not permitted by those in power. In this context, any state-sanctioned demonstration was automatically suspect. Herbert Marcuse, a controversial Marxist philosopher and professor at San Jose State University in California, termed such state tolerance of opposition “repressive tolerance.” By this he meant that by allowing certain non-confrontational forms of dissent, the state could continue its policies while providing a safety valve for those who disagreed with them. This safety valve placated the opposition without challenging the power of the state.

The Rusk demonstration was not the first instance of police violence against protestors — the Oakland Stop the Draft Week protests and the demonstrations at the Pentagon in October 1967 are two other examples. The Stop the Draft protests were attempts to block access to the Oakland induction center, at first by using such tactics as demonstrators linking arms across streets leading to the center, and then, after police viciously attacked them, by blocking the streets with their bodies, junked cars, trash cans, and whatever else might be handy. Once police moved into an area to clear it, protestors left that particular part of the street and repeated their tactics in another spot. The massive anti-war demonstration at the Pentagon was also put down violently, and the brutal tactics of the police on that occasion seemed to mark the intensification of a strategy which demanded that the state attack any demonstrations it did not approve of, no matter what their style or size.

The Fairmount police attack intensified the struggle over tactics within the movement. In its discussions and newspapers, SDS began to distinguish between moral reactions and political reactions. Although a reaction stemming from moral outrage might be militant, its symbolic nature meant that it was not seen as something that could change the reality of war or racism. Instead, such actions merely petitioned the perpetrators of those crimes to repent and remedy their ways. The morally outraged demonstrator acted from the belief that the moral rightness of his/her position would be recognized and would ultimately convince the target of the protest to change for the better.

This moral approach was contrasted to a political one, that is, a strategy which sought to impart a revolutionary consciousness to the activist. Such a consciousness-building effort “demanded that [the anti-war and anti-racist movements] transcend the difficult but inevitable boundary between symbolic and effective action.”[5] In other words, one shouldn’t just petition the system to change itself in response to moral rebukes, but should build an alternative by actively fighting the system.

The attempts by the SDS to dichotomize between morally motivated and politically motivated actions seems, in retrospect, diversionary. The history of social movements shows that, no matter what the designs of the individuals involved, such groups develop organically and usually adopt a synthesis of the two approaches.

Another facet of the larger debate taking place within SDS concerned the merits of educating to organize versus acting to organize. Differences over this question deepened the split in the movement. Proponents of educational organizing — primarily members of Progressive Labor — insisted that an educational approach strengthened anti-imperialist forces and, without such a base, militant actions could isolate and eventually weaken the movement. Proponents of action, on the other hand, argued that militancy and the police response to it played a key role in organizing efforts because they revealed the repressive nature of the state and its agencies. In the violent culture of the United States, the argument went, only violence made any impact. For newly politicized white American youth, this was a revelation.

Members of Ann Arbor SDS (calling themselves the Jesse James Gang) — notably Bill Ayers, Jim Mellen, and Terry Robbins — argued that militant tactics also “provide[d] activity based on an élan and a community which show[ed] young people that we can make a difference, we can hope to change the system, and also that life within the radical movement can be liberated, fulfilling, and meaningful.”[6] Echoing the policy of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), these three insisted that there was no dichotomy between confrontation and organizing, a position also favored by the Black Panther Party. The experiences of activists during the Columbia University strike in late spring would further validate this perspective within SDS.

Then there’s the sort of feeling among some of us that the revolutionary classes, the Vietnamese, the black people, the oppressed, are the ones who are going to make history. We’re not going to stand on the side of the oppressors. We’re going to align ourselves with the oppressed. That’s why the Vietcong flags were there in the buildings.

Mark Rudd[7]

If there was any event in 1968 in the United States which demonstrated to SDS not only the legitimacy of the action theory, but also the developing internationalist consciousness of the American New Left, it was the student uprising at Columbia University. The issues involved were directly related to US domestic and foreign policies. Columbia’s decision to continue with its ill-advised plan to build a gymnasium in Morningside Park in the black Harlem neighborhood near to the university infuriated community leaders, the student body, and local residents who had requested through official means and street rallies that Columbia cancel its plans. The university’s response was to provide a rear door to the gym allowing restricted access to neighborhood residents. Not only did this smack of Jim Crow, but it illustrated quite graphically the university’s perception of itself as the dominant force in the community, free to do whatever it wished; a perfect metaphor for the United States’ view of its role in the world.

The other issue which provoked the uprising concerned the university’s involvement with the Institute for Defense Analysis (IDA). The Institute was funded by the federal government which used the facilities of twelve private universities for weapons research and counter-insurgency and riot-control studies. In the fall of 1967, a letter written by the 100member Columbia chapter of SDS and signed by hundreds of students asked the university’s president Grayson Kirk to end the school’s participation in the IDA program. The petition was ignored. When questioned about his failure to respond, Kirk replied that the letter did not carry a return address.

Columbia’s refusal to acknowledge its complicity in the twin evils of US society — racism and imperialism — and to reconsider its position forced radicals into fighting back with a one-two combination of their own. On April 23, 1968, they marched to Low Library, which housed the university administrative offices, and demanded that charges be dropped against students placed on disciplinary probation because of an earlier protest against IDA. Three of the students on probation were Mark Rudd, a member of SDS since 1966; John Jacobs (known as JJ), a former PL member who had single-handedly led a sit-in against CIA recruiting at Columbia the previous school year; and Ted Gold, a junior at Columbia who had been arrested earlier in the year at a demonstration in New York against Secretary of State Dean Rusk, a week after Rusk spoke in San Francisco.

When the students found their way blocked by right-wing counter-demonstrators, some protestors left the area and marched to the gym construction site where a struggle with police ensued. Part of the fence surrounding the site was torn down in the melee, and one student was arrested. After this incident, students and supporters marched back to campus and took over first one, and then eventually four, buildings. As the occupation/liberation continued, almost everyone on campus and, for that matter, in the country, came to know what was going on and why. A week after the first building, Hamilton Hall, was taken over, the police attacked, vindicating “the strikers, [by] proving that the administration was more willing to have students arrested and beat-up and to disrupt the university than to stop its policies of exploitation, racism, and support for imperialism.”[8] A strike ensued, effectively shutting down the university for the rest of the semester. Two more violent mass arrests occurred: one on May 17 in an apartment building owned by Columbia, which was in the process of evicting tenants to make way for higher-income housing, and the other on May 21, at Hamilton Hall, after those whom the media labeled as leaders of the rebellion were suspended and 120 people attempted to “liberate” the building in support of those students and their demands. A total of 712 students and others were arrested during the course of the strike. Members of the New York chapter of the National Lawyers’ Guild immediately set to work on the court cases. Among these lawyers and paralegals was Bernardine Dohrn, who was to be National Secretary of SDS in 1968–9 and a central figure within Weather.

Within the “liberated” buildings themselves, the students and their allies adopted a new way of life that, in a sense, embodied the revolution they had talked about for so long. Hours were spent in discussion of tactics, politics, and logistics. In addition, for most of the participants this was the first time in their lives that they had had power, to use or abuse. For most such a realization was a liberating experience and an expression of the sense of élan and community which Ayers, Mellen, and Robbins of Ann Arbor SDS had written of.

*

Primary among the theoretical questions begging resolution in SDS policy was the role of racism in US society and how best to combat it. As the organization struggled to develop a potentially revolutionary ideology, the race issue came to be as important as opposition to the Vietnam war. However, it was infinitely more divisive. At stake was the question of how best to organize black people in the United States: as super-exploited members of the working class (PL’s position) or as an internal colony within the United States. One’s position on this question depended largely on one’s opinion of the Black Panther Party, at the time the most revolutionary group within the black struggle. Those who opposed PL politically did so primarily because they believed, like the Panthers, that blacks in the United States constituted a colony and, as such, had a right to national self-determination.

The argument revealed fundamental differences of opinion over the role of nationalism in the liberation of a people. To PL and its supporters, all nationalism was seen as diversionary and subject to manipulation by the bourgeoisie of the colony. For most of the other members of SDS, though, there was a vital difference between nationalism and national liberation and, for the black community in the United States, the Panthers represented a revolutionary road to national liberation. Bernardine Dohrn emphasized the Panther stance on this issue in an article entitled “White Mother Country Radicals,” in New Left Notes. Dohrn wrote that “ [the Panthers] have been open and aggressive opponents of black capitalism … and firm supporters of the line that anti-capitalism is fundamental to black liberation.” Further on in the article, Dohrn elaborated on an earlier SDS statement, made after the shootings by police of black students attempting to desegregate a bowling alley in Orangeburg, South Carolina: “The best thing that we can be doing for ourselves, as well as for the Panthers and the revolutionary black liberation struggle is to build a fucking white revolutionary movement.”[9] This would become one of Weatherman’s first goals.

The question of nationalism was also involved in the matter of Vietnam. Did one support the National Liberation Front in its revolutionary struggle for self-determination (the anti-PL position), or only because it was being attacked by the United States (the PL position)? As the year rolled on, and into 1969, the questions of nationalism, differences in class analysis, and perceptions of youth culture would determine the fate of SDS and create the opening from which Weatherman would emerge.

As for youth culture, SDS was focusing most of its energies on those youth who were working on the presidential campaign of Senator Eugene McCarthy of Wisconsin. His antiwar stance and appeal to college students made the campaign the natural place for SDS to organize, given their predominantly student membership. Although SDS had little faith in electoral politics, they worked with other organizations planning mass demonstrations at the upcoming Democratic Party convention in Chicago. The best known of these groups was the Youth International Party, or Yippies, founded by radicals Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, Anita Hoffman, Nancy Kurshan, and Paul Krassner. Their behavior during convention week including public insults of Mayor Daley, the nomination of a pig for president, the verbal and physical assault of police officers — and the reaction they provoked from Chicago police would change SDS politics.

SDS’s experiences that week not only caused them to shift their organizational emphasis from the McCarthy youth to those already in the streets, they also provided many in the organization with a glimpse of the revolutionary potential of the counter-culture. This, in turn, brought about a synthesis between the developing class analysis in the SDS and the burgeoning youth culture. Early attempts at producing such a synthesis began with the observation that a class is defined by its relationship to the means of production and, as the young do not control any of those means, they should identify themselves with the oppressed, not out of guilt but out of self-interest. Even the interests of privileged students (who constituted most of SDS at the time) lay more with anti-capitalist forces, not because they needed to work, but because of monopoly capitalism’s alienating expectations and requirements.

The first attempt at this synthesis can be found in a statement submitted by Mike Klonsky, a former national president of SDS, respected for his knowledge of Marxist-Leninist theory and reasoned arguments against PL. The statement, adopted at the December 1968 national convention in Ann Arbor, was entitled “Towards a Revolutionary Youth Movement.” It was an attempt not so much to present youth (specifically students) as working-class, but more to “build a link through working-class youth to the working class to bring the dynamic of the student movement to the workers.”[10] Klonsky emphasized that it was necessary for SDS to expand beyond its student base into the working class. Such an effort would be facilitated by the cross-class nature of the youth culture of the 1960s and its denial of what it saw as alienating effects of American life.

Although youth itself was not intrinsically revolutionary, Klonsky believed that “by developing roots within the class struggle, [it could be] insured that the movement would not be reactionary.”[11] Youth, the argument went, would add militancy to the struggle once it merged with the working class. The younger members of that class would be the focus of the organizing effort, not because they were more oppressed, but because they felt that oppression, in the form of the military draft, low-wage jobs, and schooling that seemed irrelevant to their experience, differently from their elders. In addition, the youth culture, in its opposition to the system, had already laid a base for such an effort.

What this expansion of the organization would necessarily mean was an end to privileges associated with being students (draft deferments); an intensified struggle against racism within the movement and the youth culture; and a redirection of organizing efforts toward technical schools, community colleges, and high schools and away from the colleges of privilege in which the movement had been born.

“Towards a Revolutionary Youth Movement” is evidence of the substantive changes which occurred in SDS in 1968, and within six months it had split the organization. It would also be a major impetus to the formation of Weatherman.

Debate over both the nationalism and the youth culture questions continued into the next year. A PL racism proposal passed at the December 1968 convention which labeled all types of nationalism reactionary was overturned at a National Council meeting in March 1969 in favor of a resolution by the anti-PL forces in support of the Black Panther Party. In another victory for the anti-PL forces, a PL-sponsored resolution condemning the use of marijuana and psychedelics, and, by inference, youth culture, was also defeated.

A proposal by Bill Ayers and Jim Mellen presented at the March 1969 National Council, entitled “Hot Town, Summer in the City,” was subsequently adopted in place of the PL statement on drugs. For the most part the proposal was a refinement of Klonsky’s “Towards a Revolutionary Youth Movement,” but there were a few substantive changes. Among these were the observations that the repression of youth culture seemed to have an inversely proportionate effect to its growth, and that there were no class boundaries to its repression, although working-class youth, especially those of color, suffered most. This recognition enhanced the view that although all workers were oppressed, youth endured a different kind of oppression. The statement went on to list some of the special forms this oppression took: the draft, mandatory and irrelevant schooling, and lack of job opportunities and meaningful employment. This proposal, like Klonsky’s, was part of a growing strategy by SDS to shift its recruiting focus away from college students and toward youth in general, including highschool and community-college students, youth in the army or who were otherwise employed, and those young people who had “dropped out” of society. The proposal searched for ways to involve less privileged youth than those found in most universities in the movement against war and racism.

Another area of concern for Ayers and Mellen was the black liberation movement. Once again, the vanguard role of the Black Panther Party was emphasized, as was the continued rise in police surveillance and repression of the Panthers’ activities. Their proposal condemned the “absence of substantial support — power — by the white movement” for facilitating this repression and urged the “white movement to be a conscious, organized, mobilized fighting force capable of giving real support to the black liberation struggle.”[12] To create such a consciousness, it was necessary for SDS to organize youth according to the Revolutionary Youth Movement’s analysis, that is, not as a cultural phenomenon but as members of the working class who had experienced “proletarianization” in schools and the army.[13] In these institutions, the young found themselves in the same boat as the oppressed black community, slaves to the lords of war and industry.

*

In the late 1960s, SDS could not ignore the evidence of the feminist movement that was gaining momentum in US society. Within SDS itself, the more revolutionary the members became, the more the women activists became conscious of their limited role in the organization. Susan Stern, an SDS member then working and living in Seattle, remarked that “SDS was operating at half of its potential” because of its failure to give women leadership positions.[14] The growing awareness that women in the movement “do office work and even run offices, but are discouraged from articulating political positions or taking organizational leadership” caused many women to rethink their participation in the movement and question its integrity.[15] Some women claimed men were to blame for their oppression. Others saw the system of power as the culprit: pitting gender against gender to keep people divided. Some voiced the possibility of considering women as a separate class, while others, citing the example of the revolutionary Vietnamese women, quoted NFL theorists: “The struggle of women for freedom and equality could not but identify itself with the common struggle for national liberation”[16] — or, simply, the common struggle.

Some women eventually left SDS for other organizations, many of them separatist in nature. Most, however, hoped, as Naomi Jaffe, a New Left Notes staffer in New York, and Bernardine Dohrn did, that a new strategy could be developed. This strategy for liberation did “not demand equal jobs, but meaningful creative activity for all; not a larger share of the power, but the abolition of commodity tyranny; not equally reified sexual roles but an end to sexual objectification and exploitation; not equal aggressive leadership in the movement, but the initiation of a new style of non-dominating leadership.”[17] If nothing else, SDS and the New Left movement would, it was hoped, redefine the nature of a white-maledominated society.

2. Weather Dawns: The Break and the Statement

If white people are going to claim to be white revolutionaries or white mother country radicals, [they] should arm themselves and support the colonies around the world in their just struggle against imperialism. Huey Newton[18]

The 1969 SDS National Convention began on June 18. By evening, over 2,000 members had passed through the security and underground-media cordon to take their places in the Chicago Coliseum. Discussion among many of the non-PL members centered on the statement which had appeared in that day’s issue of New Left Notes, entitled “You Don’t Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows …” The piece, which was written primarily by members of the Columbia chapter of SDS, borrowed its title from the Bob Dylan song, “Subterranean Homesick Blues.” It was the founding statement of the Weatherman organization.

The Weatherman statement had been discussed and argued about in SDS national and regional offices since the late spring. Its primary drafters included SDS members whose names would become synonymous with Weather: Bill Ayers, Mark Rudd, Bernardine Dohrn, Jim Mellen, Terry Robbins, John Jacobs, and Jeff Jones. The other authors were Karin Ashley, Howie Machtinger, Gerry Long, and Steve Tappis. Ashley and Tappis would cease to be Weather members before the end of the year.

As delegates argued over the contents of the Weatherman statement, and PL members figured out a strategy for maintaining some degree of power in the organization, a group of Black Panthers entered the hall. One of them launched into a tirade against PL, calling the group “counterrevolutionary traitors.” At first those who were listening applauded or booed the speaker depending on their political views, but when the speech slipped into a rant against the growing feminist movement, the noise died down. Then another Panther began to chant “Pussy power. Pussy power!” and asserted that the only position for a woman in the revolution was a prone one. These statements provoked a very loud reaction from virtually everyone on the floor, and the Panthers eventually left the podium, having lost any voice for the time being.

The next day began much the same as the first, with discussions and workshops continuing throughout the meeting space. Toward evening, while members argued over a number of resolutions on racism, a group of Panthers once again entered the hall and took the stage. They read a statement repeating much of the previous night’s comments about PL and told SDS that they would be judged by their actions — in effect calling for SDS to expel PL from its ranks. A number of PL members then grabbed the microphone and attacked the Panther position on black nationalism, while otherwise praising them. In addition, they accused the SDS leadership of opportunism in bringing the Panthers to the convention. Next, Bernardine Dohrn took the stage and asked those in the hall if it was still possible to work in the same organization as PL. Mark Rudd then called for an adjournment, but before debate could begin on the motion, Dohrn led about half the delegates to the adjacent annex where the discussion continued through the night.

Meanwhile, those who remained in the main hall also continued to talk and, some eighteen hours later, issued a resolution calling for unity. Finally, by midnight on the 21st, debate ended and the delegates who had left with Dohrn the previous night filed back into the main hall and listened to Bernardine read PL out of SDS. PL members tried unsuccessfully to shout her down with cries of “Shame” and “Smash racism!” Once the reading of the expulsion resolution was over, the new SDS, without PL, marched out of the hall with their fists in the air.

When the convention ended next day not only was PL no longer officially recognized, but, despite the existence of a third force at the convention, which came to be known as RYM (Revolutionary Youth Movement) II, the national office now comprised Weatherman members Bill Ayers, Jeff Jones, and Mark Rudd. The newly formed coalition between RYM II and Weatherman, based mostly on their opposition to PL, was tenuous, to say the least.

The only resolution to pass through this fractious convention besides the ouster of PL was a call for a week of protests in Chicago in the fall. The composition of the organizing committee for these protests also reflected Weatherman’s new power: Kathy Boudin, Bernardine Dohrn, Terry Robbins, the three national officers, and Mike Klonsky of RYM II.

With the publication of ‘You Don’t Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows,” Bernardine Dohrn’s call a year earlier for a white fighting force to support the black liberation movement began its transition from words into reality. If the statement did little else, it placed the struggle of black people in the United States at the forefront of the fight against US imperialism.

The statement identified the black struggle as part of the “worldwide fight against US imperialism,” and argued that the black community’s role in that struggle was of primary importance. If the black community (or colony, as Weather preferred to call it) was successful in its fight for liberation, the United States would not survive because of the essential role played by the citizens of the black colony in the formation and perpetuation of the US system. Slavery was fundamental to the development of capitalist society in the British colonies and in the first several decades of the United States: not only did the slave trade create profits which could be invested elsewhere, it also enabled slaveowners to acquire wealth rapidly. When slavery was no longer essential to the continued accumulation of wealth, the ex-slaves and their descendants were relegated to a no less essential but often harsher economic slavery which existed to this day.[19]

By defining the black community as a colony “existing in the country as a whole” instead of solely as a black-belt nation in the southern United States (an analysis advanced by Robert Williams and the Movement for a Republic of New Afrika) ,[20] the statement perceived the “common historical experience of importation and slavery and caste oppression” as the basis for national identity. That identity, as the “Black Proletarian Colony,” made it essential for the colony to organize as revolutionary socialists. Attempts to organize black people in other ways denied the struggle’s communist roots. Although it differed from that of many black nationalist groups, Weatherman’s analysis was virtually identical to that of the Panthers, especially in terms of its insistence on black Americans’ history of economic oppression.

“You Don’t Need a Weatherman” went on to argue that it was “necessary for black people to organize separately and determine their actions separately” from their white counterparts.[21] To do otherwise denied the struggle’s particular investment in the defeat of US imperialism and negated its revolutionary nature, a sentiment that echoed previous struggles within the black liberation movement, especially those surrounding the ouster of whites from SNCC in 1965. As Stokely Carmichael wrote in his book, Black Power, “black people must run their own organizations because only black people can convey the revolutionary idea — and it is a revolutionary idea — that black people are able to do things themselves.”[22] The authors of “You Don’t Need a Weatherman” concluded the section on the black liberation movement by stating that although the black movement did not need white revolutionary allies to win, it would be racist to contend: “1) that blacks shouldn’t go ahead making the revolution or 2) that they should go ahead alone with making it.” Instead, the statement argued that a third path, supporting the black struggle, should be taken.

While few in the revolutionary New Left disputed the central role of the black liberation struggle in the fight against US imperialism, many critics of Weatherman warned against creating an organization which would act primarily in support of the black struggle. Paul Glusman, in an article in the New Left journal Ramparts, offered the opinion that, “SDS, all of it … left out any mention of white youth as a revolutionary force for themselves … One would think the Panthers would prefer allies who are in it for themselves and not guiltridden successors to the civil-rights liberals who left when things got hot.”[23] David Hilliard of the Panthers expanded this criticism in a statement made after the Panther-sponsored United Front Against Fascism conference in Oakland, California in June 1969.[24] This statement was a response to a Weatherman offer to help participants at the conference distribute a petition calling for community control of the police in communities of color but not in white communities. Such an offer assumed that white communities would not liberalize their police forces while communities of color would. Besides expressing a lack of faith in white people, young and old, the Weatherman offer seemed to imply that the thirdworld community was not able to do the work itself.

After its discussion of the role of the black anti-imperialist struggle in the overthrow of the US system, “You Don’t Need a Weatherman” addressed the question of united-front politics. That is, whether it was desirable first to create a broad democratic coalition to throw out imperialism and then, after that task was completed, to install socialism. It was the opinion of Weatherman that this two-step process was usually applied to semi-feudal societies and was unnecessary in the United States which was in the most advanced stage of capitalism: imperialism. When imperialism was defeated in the United States, Weather argued, it would be replaced with socialism, and nothing else. While many on the revolutionary New Left agreed with this analysis, they did not agree with Weatherman’s interpretation that working with reform movements in a united front, no matter what the cause, was counterrevolutionary. It was here that Weatherman disagreed with most of the rest of the revolutionary left, RYM II included. Weatherman’s insistence on revolutionary purity — or, as “You Don’t Need a Weatherman” put it, “someone not for revolution is not actually for defeating imperialism either” — created a situation which, in the long run, made it virtually impossible to organize anyone but the already converted.

In the international fight against US imperialism Weatherman supported all struggles for self-determination in the colonies. They reasoned that the cost to the imperialists increased proportionately with the support given to those struggles which, in turn, would lead to cutbacks in social-services spending and job creation at home. These cutbacks would force welfare recipients, and the working class in general, to struggle even harder to maintain a minimal standard of living. This, theoretically, would create a revolutionary situation which, if properly organized, would lead to the defeat of the ruling elites.

To realize such a vision, however, required the organization of the working class into a revolutionary force. In order to accomplish this, the working class had to be made aware that its interests lay with the anti-imperialist forces of the world — not a simple task in 1960s America. Although a few unions supported the more liberal demands of the anti-war movement (negotiations, for example, and an end to the bombing), most did not. Of those that did, very few of their members considered themselves revolutionaries. Consequently, SDS, and especially Weatherman, perceived white workers in the United States as only too happy to support the country’s interventionist and racist program. Weatherman believed the white working class to be racist, pro-war, incapable of recognizing its own oppression, and the enemy of the anti-imperialist cause.

There was hope, however, for youth. Because of their current oppression especially in the form of the military draft, Weatherman decided it was possible to build a revolutionary youth movement, an idea that had originally been proposed in December 1968 in the statement “Towards a Revolutionary Youth Movement.” Youth met the criterion that any person who had nothing but his or her own labor to sell was a member of the working class. Because they generally held a smaller stake than their elders in the existing society and had grown up “experiencing the crises of imperialism”-Vietnam, Cuba, black liberation — young people were more open to new ideas, especially the idea that the system could be overthrown. After all, thousands of young men were monthly being coerced into fighting for that system and had good reason to be rid of it.

The system, under threat, resorted more and more to force and an accompanying authoritarian ideology which — the statement continued — met with resistance. First from the black people of the United States and eventually from Chicano, Puerto Rican, and white youth as well. Some resisted through political struggle, many others — no matter what their class origin — by rejecting mainstream society and joining the counter-culture, which by now had developed a fighting edge due to its repression by the police. Calling themselves “freaks” and “yippies,” counter-culture adherents were beaten up by the police for their anti-social behavior just as politicos were at demonstrations. When the two elements of youthful resistance joined together in a common fight, as in the ill-fated attempt by students, radicals, and counter-cultural street people to build People’s Park in Berkeley in May 1969, an armed attack by police resulted, with the death in that instance of one protestor and the maiming of many others.

The developing youth movement transcended class. However, since the oppression of youth hit working-class youth hardest, it was necessary, as stated earlier in “Towards a Revolutionary Youth Movement,” to move “from a predominantly student elite base to more oppressed [less privileged] youth” in order to expand the existing revolutionary force. To do this, the Weatherman statement emphasized the necessity of linking people’s everyday crises to revolutionary consciousness. Weatherman gave as examples of a multi-issue approach the Columbia occupation of 1968, when the expansion into the black community surrounding Columbia was linked to the university’s involvement in Defense Department counter-insurgency programs, and the battle over People’s Park in Berkeley in 1969, where the question of private property came together with the issue of free speech and the concerns of the anti-war movement. Weatherman also urged students not to fight for reforms in the schools, but to close them down until the time came when schools could serve the people and not the corporate class.

Toward the end of the statement, Weatherman addressed the role of the police. In a section entitled “RYM and the Pigs,” the police were defined not as representatives of the state, but literal embodiments of it. Given their ever-increasing aggression against radical groups (e.g. the raids on both the SDS and the Panther offices in Chicago and the shootings at People’s Park in Berkeley in the spring of 1969), Weather believed that a revolutionary movement had to overcome the police or risk becoming “irrelevant, revisionist, or dead.”

Of course, whether the primary aim was to fight the police or to attack the system which employed them, the state’s repression of its opponents was bound to increase. As a result, it was necessary to oppose repression, which would “require the invincible strength of the mass base at a high level of active participation.” In other words, “the most important task for [SDS] toward making the revolution … is the creation of a mass revolutionary movement, without which a clandestine revolutionary party would be impossible.” It is unfortunate that Weatherman failed to adhere to its own advice and, like the Panthers, develop allies outside the revolutionary movement.

Most of ‘You Don’t Need a Weatherman” is a more complex development of positions proposed in “Towards a Revolutionary Youth Movement.” One topic remained unexamined in both: the role of women and of feminism in the revolutionary youth movement. Although two women were among its drafters, “You Don’t Need a Weatherman” merely stated that the group had “a very limited understanding of the tie-up between imperialism and the women question.” While acknowledging the continually expanding wage differential in the workplace based on gender and the gradual disintegration of the nuclear family under monopoly capitalism, the Weatherman leadership collectively stated that it “had no answer, but recognize [d] the real reactionary danger of women’s groups that are not selfconsciously revolutionary and anti-imperialist.” They then proposed developing different forms of organization and leadership which would enable women to take on new, independent roles.

*

Although few Weatherman members prided themselves on their reading of political theory, seemingly preferring to draw their theory from praxis (Rudd is even quoted in Kirkpatrick Sale’s account of SDS [1973] as bragging that he hadn’t read a book in a year), one book which was widely read in the collectives was Regis Debray’s handbook of guerrilla warfare in Latin America, Revolution in the Revolution? The importance to Weatherman of Debray’s book is impossible to overstate. In addition to underground newspapers and other Left periodicals, well-thumbed copies of Revolution in the Revolution? were to be found in every Weather collective’s house.

Nominally a handbook for the revolutionaries in South America, Revolution in the Revolution? was adopted by the future members of Weatherman in the interim between the Columbia strike and the June 1969 SDS convention probably because of its discussion of recent events in the Americas, and its mention of, and the author’s familiarity with, the heroes of the New Left: Che Guevara and Fidel Castro. Although supposedly a guide to revolution, Debray seems to invalidate his purpose in the book in the first fifteen or so pages by stating that the Cuban revolution could not be repeated in Latin America or anywhere else. This was so, said Debray, because no revolution can copy another, but can only utilize the objective conditions within the particular country — conditions which, are “neither natural or obvious … [but] require years of sacrifice to discover.”[25]

Patience was the strategy that Debray emphasized above all others. Quoting from the work of Simon Bolivar, he writes that the most valuable lesson for revolutionaries is tenacity. It is tenacity, after all, which provides the revolutionary with the foresight to see beyond the various failures and victories (s)he will encounter, as Debray learnt from his own experiences and his knowledge of the history of Cuban struggle against Batista. Failure, according to Debray, provides experience and knowledge far more than victory does.

Whether or not Weatherman accepted this concept in practice is questionable. It did, however, believe itself to have a clear answer to the ultimate question for a revolutionary organization: “How to overthrow the capitalist state?”[26] Its answer was to obey Debray’s instructions in accordance with its self-perception. In contrast to the Panthers, Weatherman did not consider itself a self-defense force. Instead, it preferred the idea of forming the core of a future revolutionary army which, according to Debray, needed to exist as an organic unit separate from the regular population. In order to attain its goal, then, the revolutionary guerrilla army needed to be clandestine and, to show its viability, willing to take the initiative by attacking the enemy.

To maintain the necessary secrecy, Debray suggested operating in small autonomous groups or focos. These focos would develop their own strategy of attack to achieve an objective set out by a centralized leadership. Such a structure enabled each foco to carry out its part of the mission; however, if any member or members were captured, their knowledge of the entire operation would be limited to the movements of their particular foco. This structure also provided the organization itself with greater internal security as an infiltrator’s knowledge would be severely limited.

While the focos carried out their work, continued Debray, the masses must be educated politically. Armed struggle alone would leave the revolutionary forces isolated. On the other hand, political struggle without armed action was equally undesirable, as a political organization risked becoming an end in itself, perhaps even becoming involved in the electoral process of the state. The moment, historically speaking, when political, military, and other considerations were ripe must be seized. How one determines such a moment came not from the understanding of a particular theory or terrain, but from “a combination of political and social circumstances” which, when recognized, could be acted upon.

All of which is not to say there should be no action before that historical moment. Indeed, wrote Debray, the revolution is a constantly changing reality. The occasional well-planned attack can convert more people to the idea of revolution than months of speeches and writings — a view borne out, for example, by the actions at Columbia, which radicalized many more people than previous rallies and speeches had done, thus substantially propelling the movement forward.

In order to facilitate the organization of the people, the revolutionary group must be strengthened and develop a truly mass line. If the group develops the correct line, the people will recognize it as the vanguard party. Should the party be composed of members of the bourgeoisie and the petty bourgeoisie, like Weatherman, and the masses accept their leadership, the members must “commit suicide as a class” in order to be reborn as workers.[27]

As long as no armed struggle exists, according to Debray, there can be no vanguard. Instead, what usually occurs in such a vacuum is the growth of a plethora of groups who call themselves Marxist-Leninist and revolutionary. Thus, in the late 1960s and early 1970s there were constant battles in the US between various sectarian groups over issues and tactics in a struggle, with each claiming to be more revolutionary than the others. Mass organizations such as the Seattle Liberation Front, November Action Coalition (Boston-Cambridge), the Mayday Tribe (Washington, D.C.), and the People’s Coalition for Peace and Justice attempted to lead the movement but, due largely to the lack of a long-term program and law enforcement harassment, fell by the wayside. In the interim, revolutionary organizations with a potential for longevity disintegrated into sectarian squabbles over marginal political issues.

Weatherman recognized the danger of sectarianism because of its ongoing battle with the Progressive Labor faction in SDS. But although the organization wished to transcend such divisions by acting on Debray’s advice and “pass(ing) over to the attack,” its puerile focus on revolutionary purity undermined its aims and contributed to its failure to organize large numbers of people.[28]

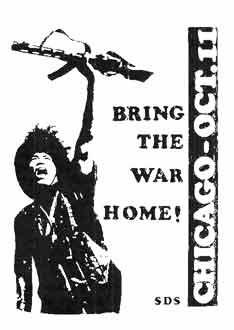

3. Into the Streets: Days of Rage

It has been almost a year since the Democratic Convention, when thousands of young people came together in Chicago and tore up pig city for five days. The action was a response to the crisis this system is facing as a result of the war, the demand by black people for liberation, and the ever-growing reality that this system just can’t make it. This fall, people are coming back to Chicago: more powerful, better organized, and more together than we were last August. SDS is calling for a National Action in Chicago October 8–11. We are coming back to Chicago, and we are going to bring those we left behind last year.

SDS leaflet, summer 1969

After the convention in June 1969, Weatherman and RYM II controlled the new SDS, although they probably represented no more than 4,000 members of an organization whose membership in late 1968 had peaked at about 100,000. Their task was clear — to organize thousands of youths to come to Chicago and demonstrate “against the war in Vietnam, in support of the Black Panther Party, and in solidarity with all political prisoners, including Black Panther Huey P. Newton, and the eight under attack for last summer’s righteous demonstrations” during the Democratic Party convention.[29] But with the National Organizing Committee for the fall protests composed of members of both Weatherman and RYM II, the stage was set for yet another split, even if no one thought so at the time.

Weatherman and RYM II were unified in their opposition to PL, mostly because of its attacks on the Black Panther Party, and black nationalism in general, and its criticism of the NLF and North Vietnam’s willingness to negotiate an end to the war. But any lasting unity between the two was unlikely because they disagreed on almost everything else, especially strategy. Both believed that armed revolution was necessary in the United States, but the timing of that revolution and the role of white workers in it were a source of much discord. By late August, Mike Klonsky, nominal leader of RYM II, quit the National Organizing Committee, primarily because of his opposition to Weatherman’s dismissal of the white working class as hopelessly reactionary. This left both the National Organizing Committee and the National Office completely in the hands of Weather. Bill Ayers, Mark Rudd, and Jeff Jones headed up the National Office, while the committee organizing the fall protests comprised Bernardine Dohrn, Terry Robbins, Kathy Boudin, and the three national officers.

RYM II regarded the call for massive demonstrations in the fall as a call for a “united front against imperialism” which would, by linking workers’ struggles with the war in Vietnam and the black colonies, convince “the masses of working people” to take a stand against imperialism.[30] Given Weatherman’s belief that united-front politics were not necessary in the United States because of its late stage of capitalist development, this issue was another point of dispute.

Also, according to Weatherman, any efforts to reform the system — the schools, workplace, army, etc. — were merely attempts to gain more privileges for the already privileged white population. As Mark Rudd and Terry Robbins put it in their reply to Klonsky’s public letter of resignation: “Here [in the United States] the just struggles of the people do not necessarily raise consciousness or build a revolutionary movement. Much to the contrary, they often obscure the differences between the colony and the mother country, obscure white skin privilege, obscure internationalism.”[31] Klonsky’s view was that the working class must be won over by addressing their issues “with patience, not arrogance,” and he and the rest of RYM II began organizing their own fall protests in Chicago.[32]

According to Weather chronicler Harold Jacobs (1970), Weatherman had not given up hope of realizing white America’s revolutionary potential, but the general perception in the New Left in 1969 was that it had. Consequently, its isolation from the movement had begun.

If there is a conspiracy to end the war, if there is a conspiracy to end racism, if there is a conspiracy to end the harassment of the cultural revolution, then, we too, must join the conspiracy.

Ad in The Seed to defend the conspiracy

The so-called conspiracy referred to the indictment of eight men — the Chicago 8 — under new federal conspiracy statutes for, among other charges, “crossing state lines with the intent to riot” during demonstrations in Chicago at the time of the Democratic Party convention in August 1968. By including counter-cultural revolutionaries Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin in the conspiracy indictment, the state demonstrated its perception of the counter-culture as insurrectionary. It is possible that by indicting the two yippies the Justice Department hoped to intimidate young people into forsaking revolutionary politics and life styles. Instead, the opposite happened. Chicago 8 defendant Tom Hayden capsulized the sentiment of a substantial number of the nation’s youth with the statement, “Our identity is on trial.”[33] The Chicago Conspiracy became a cause celebre and as a result thousands of youth adopted revolutionary politics. Weatherman, hoping to gain recruits from this phenomenon, shifted toward support of counter-cultural struggles such as that in Berkeley over People’s Park.

In Seattle, after police attacked a free rock concert at a local beach on August 10, a youth uprising lasting two nights took place in the university district, with massive looting and attacks against small businesses like record and clothing stores (“hip” capitalists) as well as buildings housing branches of national corporations. The local Weather collective encouraged attacks on banks, military recruiters, and other obvious targets connected to the war in Vietnam, as collectives would do in other cities where youth fought the police.

As the uprising in Seattle spread and black and Latino youths joined in, racist remarks were heard from some of the rioting white youth, to the distress of Weather members. Considering the centrality of racism to Weather’s analysis and its oft-repeated insistence on the necessity to combat racism wherever it was found, its involvement with youth, especially white working-class youth spouting anti-black sentiments, increasingly led some members to further question the usefulness of organizing whites. Others in the New Left faced similar dilemmas regarding racism in the counter-culture but were willing to work and struggle with the racist attitudes they encountered, while Weather simply labeled as “pigs” all those it regarded as less politically advanced.

The counter-cultural watershed of the summer of 1969 was the Woodstock festival in August. Despite the input of some radical activists in the planning of the event, the weekend concert was primarily set up by the large record companies (notably Warner Brothers) to expand their markets, but the eventual breakdown of festival security created a liberating situation. A reporter for the Chicago underground paper The Seed wrote about it thus: “Woodstock was … a massive pilgrimage to an electrified holy land where high energy communism replaced capitalism … because the immediate negative forces of the outside world, cops, rules, and prices had been removed or destroyed.”[34] The news that half a million young people had created their own society, no matter how temporary, convinced millions who didn’t attend that a great counter-cultural community existed beyond whatever locality they happened to live in.

Before the festival the number of young people who embraced some aspect of the counterculture — even if that meant merely buying records — was appreciated mainly by the entertainment industry. The sheer impact of the Woodstock festival on US society forced those in other segments of the American power structure to pay attention to youth as well. The New Left too took note. New Left Notes commented that the same record companies that “sell liberating music are big-time defense contractors,” and argued that America’s youth should liberate its culture. In the same manner that Weather linked so-called “hip” capitalists with corporate ones, the article informed readers that capitalists, not performers, made most of the money from music (soon after, of course, things changed, with entertainers often making more money than many small corporations). This was a commonly held analysis among counter-cultural radicals but would not be enough to convince the youth of America to join Weather in Chicago in the fall.[35]

*

Weatherman took the offensive once the members of the various collectives had returned to their cities of operation after the national convention. They believed that the best way to show their willingness to fight a revolution was to do just that, a view deriving not only from the Weather interpretation of the foco strategy, but also from its romanticized perception of US working-class youth. Cathy Wilkerson, a founder member, recalled that Weather “was trying to reach white youth on the basis of their most reactionary macho instinct, intellectuals playing at working-class toughs.”[36] Indeed, Mark Rudd and Terry Robbins stated that Weather needed to be “a movement that fights, not just talks about fighting. The aggressiveness, seriousness, and toughness … will attract vast numbers of working-class youth.”[37] With this class-based vision of an army, Weatherman and its approximately 350 members took its call for a revolution in Chicago to the youth of the nation.

In a highly publicized organizational effort one Saturday in July, Detroit Weatherman (or Motor City Weatherman, as the members referred to it) went to Metro Beach, located in a working-class suburb and at the time a favorite hangout for the youth of the area. Weatherman arrived in the early afternoon, carrying a red flag and distributing leaflets calling on youth to go to Chicago in October to fight the police. Within minutes of the group’s arrival, a crowd of approximately two hundred had formed. They began arguing with the Weather cadre about communism, the Viet Cong, and racism in the United States. A short time later, after being informed that lifeguards had called the local sheriffs, Motor City Weatherman moved away to regroup and decide what to do next. The crowd had other ideas. Fists began to fly, and after a fierce fight, Weather left. It is doubtful that any of those on the beach that day ever went to Chicago, but one biker involved in the brawl later told a member of the Motor City collective that while he enjoyed the fight that afternoon, he “would enjoy fighting the pigs in Chicago more.”[38]

Another action by Motor City Weatherman took place at a junior college, in an “all white working class community” according to New Left Notes. Weather’s rationale for this target was that the students at the college were being trained for low-level managerial jobs that would directly oppress black people. A group of nine women “entered the classroom chanting, and barricaded the door with the teacher’s desk. Various members of the cadre spoke to the students, who had been taking a final exam, about the Chicago action, imperialism, racism, and the oppression of women.” After listening for a few minutes and growing increasingly angry because their exam was being interrupted, some male students pushed the Weather women out of the way in an attempt to leave. A fight ensued. The women failed to escape before the police arrived, and nine were arrested and charged with disorderly conduct.[39]

During this period local collectives functioned autonomously with regards to fundraising and actions around local issues. The national leadership (or Weatherbureau, as it came to be called) directed the individual collectives in terms of political positions and organization for the national action. Collectives maintained themselves financially by various means. Some members still received checks from their trust funds or relatives. Others worked regular jobs, sold drugs, or received public assistance, and some of those who were still in college obtained some kind of financial aid. All of these monies were placed in a common fund in each collective from which expenses were paid. The Weatherbureau supplemented its own collective income with whatever membership payments and contributions it received as the nominal leadership of SDS, which by this time was not much. In fact, several pleas for money were sent out in the fall of 1969 because of SDS’s severe shortage of cash.

In tandem with external organizing actions the collectives also attempted to crush any vestiges of bourgeois ideology among members. To facilitate this, the national leaders, who were based in Chicago, traveled to Weather collectives around the country. Once there, the individual from the national leadership, say Rudd or JJ (John Jacobs), began a series of maneuvers designed to identify those local members perceived to be the most willing to cooperate with the leadership and place them in positions of power. This might involve marathon criticism sessions in which all those present, sometimes having ingested LSD, challenged the commitment of the person being critiqued. The procedure might include sexual activity designed to destroy monogamous relationships, whether equal partnerships or not, though some members agreed that their relationships needed to be redefined, and separated willingly, or the forced coupling of people who might or might not wish to sleep together. One purpose behind these procedures was to create a tightly run, autonomous, and ego-less foco of street fighters. Another, less obvious purpose was to decrease the power of locally strong individuals who might interfere with the overall plans of the national leadership. Weather’s opposition to monogamy was based on the belief that it prevented members from taking risks and that the desire to protect the relationship would cause a failure of will. Doing away with traditional forms of monogamy was not necessarily a bad idea and formed part of a strategy to end male supremacist attitudes in the organization, but the authoritarian manner in which it was undertaken caused much useless dissension and emotional stress.

If the national leadership had paid closer attention to its less political counterparts in the counter-culture, perhaps it would have learned that new forms of relating to another sexually and otherwise — are much easier to adopt if introduced with sensitivity and love. Instead, during this period the national leadership, using recruits eager to curry favor, destroyed strong monogamous associations by separating couples and ridiculing their relationships. The justification for these activities was the African revolutionary Amilcar Cabral’s dictum of the necessity to “commit suicide as a class” in order to truly lead the revolution.

*

Weather organized around the line that anyone “who played pig” was the enemy.[40] What Weather meant by the phrase was explained by Rudd in New Left Notes. His argument went like this: in order to maintain control, the ruling elites in the US utilized both “the priest and the hangman;” and, if the non-violent persuasion of the priest did not work, then the hangman’s skills were employed to maintain order. To allow the teacher or the serviceman or woman off the hook just because they might be well-intentioned victims of circumstance was to allow the bourgeoisie to go unchallenged, and, in Weather’s view, this was not much different from letting President Nixon off the hook for the continuing war in Vietnam.[41]

Accordingly, a group of Boston Weather people invaded a meeting in the early fall of 1969 at Boston University, which was called to organize anti-war actions coinciding with the October 15 Moratorium to End the War and the November 15 Mobilization to End the War. After barricading the doors, various members of the collective spoke for a few minutes and then attacked those present, calling them counter-revolutionaries and pigs because they differed with Weatherman’s program and did not support its national action planned for Chicago.[42] Another action of the Boston Weather collective that fall was a raid on the Center for International Affairs at Harvard University. This government-funded institute, directed by a man named Benjamin Brown, was involved in war-related research. The Weather people “broke into the building, hung the Viet Cong flag from the window,” attacked Mr. Brown and some of his colleagues, and then left. Three Weather men — Eric Mann, Henry Olson and Phil Nies — were charged for the attack.[43]

Its line on “playing pig,” especially in relation to the blossoming GI movement for civil rights in the military and against the war, was more self-defeating for Weather than any of its other theoretical mutations. In every revolution victory has depended on large numbers of common soldiers. In its haste to make revolution, and without regard to the economic or social pressures on those in the military or facing the draft, Weatherman issued an ultimatum to the American soldiers. “Turn your gun around,” it said, “or you are the enemy.”[44] In essence, GIs were “pigs” until they proved otherwise. Ironically, as Carl Davidson of RYM II, pointed out, Weather’s heroes, the National Liberation Front of Vietnam, who had “every reason to express a burning hatred of GIs never refer [red] to them with anything approximating the term ‘pig.’”[45]

The approach of other Left groups shows how removed Weatherman’s perspective was from that of the rest of the movement. About this time, The Black Panther, the party paper, printed weekly articles on the radical GI movement and addressed open letters to GIs calling for their support. Other anti-imperialist organizations printed special leaflets to give to GIs at demonstrations, especially when the demonstrations were held at military bases. These leaflets were sympathetic in tone and usually provided phone numbers and addresses of groups and individuals who might be of assistance to soldiers wishing to desert.

Recruiting for Weather at this time mostly involved getting young people interested in the actions planned for October in Chicago. Weather usually drew attention to itself by provoking some kind of reaction to its presence. Afterwards, those who expressed an interest in what Weatherman was or what they hoped to do, were invited either to the next planned action or to a meeting with members of the local collective at a neutral place — a coffee shop or restaurant, for example. Larry Grathwohl, an informer, was recruited into Weather in this way. After a couple of conversations in the streets of Cincinnati, about the war and the need for revolution in the US, with members of the local Weather collective, he accompanied the group to some demonstrations. They then invited him on a late-night graffiti-writing excursion and, finally, to the house the collective shared. After that visit, he was then asked to live in a house whose occupants functioned as a support group for the primary collective. His housemates in that house were allies of Weather but were not considered to be completely committed to the organization. Later he moved into the main Cincinnati collective’s house, when the move was approved by visiting members of the Weatherbureau.[46]

Organizing for the Chicago demonstrations continued for the rest of the summer and fall. On September 4, in Pittsburgh, a group of eighty or so women from Weatherman collectives around the country ran through a high school shouting “jailbreak” and urged students to decide whether they were for the black and Vietnamese revolutions or against them. When the police appeared, the women fought viciously and broke away, only for twenty-six of them to be arrested down the road a few minutes later. According to the women’s postaction summary, the demonstration proved that a “fighting force of women” existed, and, by existing, challenged male supremacy.[47]

Meanwhile, some members of Weather — including Bernardine Dohrn, Ted Gold of Columbia, Dianne Donghi of Cincinnati, Diana Oughton of Ann Arbor, and Eleanor Raskin of New York — traveled to Cuba to meet with representatives of the Cuban and North Vietnamese governments and the NLF of Vietnam. The trip lasted five weeks and involved tours of the Cuban countryside, long discussions, and even some work in the Cuban sugar fields. Although the FBI and its conservative supporters in the US Congress were convinced the trip was for “guerrilla training,” little evidence other than hearsay exists to support this belief. However, Weatherman was told to raise the level of confrontation in the US in order to help the NLF and North Vietnamese win in Vietnam. Some of the travelers received rings made from the wreckage of B-52 bombers shot down over Vietnam. Nothing concrete came of the meetings but the inspiration they provided intensified the group’s commitment to the struggle of the Vietnamese people and to a revolution in the United States.

*

As October 8 edged closer, Weatherman increased its efforts in cities throughout America, claiming that tens of thousands of youths would converge on Chicago “to tear the motherfucker apart.”[48] The local collectives worked to obtain commitments from nonWeather radicals who had expressed previous interest in the upcoming actions, as the Weatherbureau stepped up its pressure on the local collectives to produce numbers. Collectives were located in New York, Boston, Seattle, the San Francisco Bay area, and a dozen or so cities and college towns in the Midwest — Cincinnati, Cleveland, Ann Arbor, Chicago, and Detroit were some of the larger contingents. Preparing for the worst, the city of Chicago cancelled all police leave and enforced overtime. National Guard troops were also placed on alert, in case they were needed by Illinois state officials.[49] In Seattle, cars belonging to members of the Weatherman collective were shot up by plain-clothes police in an attempt to intimidate the owners. Also in Seattle, the women of the Weather collective trashed a university building which housed the campus Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC).

Many groups in the movement advised supporters to stay away from Chicago and criticized the upcoming Weatherman action as adventurist and self-destructive. Fred Hampton of the Chicago Panthers observed, “The Weathermen should have spent their time organizing the white working and lumpen class instead of prematurely engaging in combat with triggerhappy pigs.”[50] The Seed provided its readers with a preview of both the Weatherman and the RYM II actions (set to occur during the same week). The latter were coordinated with those of the Chicago Panthers and the local chapter of the revolutionary Latino organization, the Young Lords. The article included The Seed’s skeptical observation that although Weatherman was counting on thousands of youths to show up, its plans had failed to excite even the Chicago counterculture and New Left communities.[51]

Other underground papers also reported on preparations in the various local Weather collectives. Members were taught self-defense and street-fighting techniques to calm their fears. Sympathetic doctors and first-aid workers helped with medical preparations, and those planning to attend the week of actions were advised to dress appropriately with protective gear like football helmets and padding.

Along with self-defense practice came an increasing display of bravado. In a speech to fellow Weather members at the Midwest National Action conference in Cleveland that August, Bill Ayers answered charges of adventurism from the Panthers and others by claiming that “if it is a worldwide struggle … then it is the case that nothing we could do in the mother country could be adventurist … because there is a war going on already.” Ayers insisted that Weatherman was intent on opening another front in the worldwide revolution, and placed all those who disagreed with its ideas in the camp of “right-wingers [who] … are not our base, they never were, and they never could be.” In response to RYM II’s organizing slogan, “Serve the People,” Ayers said that Weather would “fight the people” if to do so would further the international revolution.[52] A writer for the Boston underground paper Old Mole-wrote at the time that “Weatherman [was] probably correct in denying that there will be a purely internal [domestic] revolution,” but its actions did not “serve the needs of oppressed peoples — American or Vietnamese — but of frustrated people in the movement.”[53]

Two days before Weatherman’s October 8 debut a dynamite explosion destroyed a 10-foot statue of a policeman in Haymarket square where the “mass march” was to begin later in the week. The statue commemorated policemen who died during the 1886 Haymarket riot.[54]