Terry Jay Ellingson

The myth of the noble savage

The Myth of the “myth of the Noble Savage"

A Rose as Represented by Another Name Might Stink

I. The birth of the noble savage

1. Colonialism, Savages, and Terrorism

2. Lescarbot’s Noble Savage and Anthropological Science

II. Ambiguous nobility. Ethnographic Discourse on “Savages” from Lescarbot to Rousseau

4. The Noble Savage Myth and Travel-Ethnographic Literature

The Unphilosophical Travelers and the Savage

5. Savages and the Philosophical Travelers

Noble Fantasies: Lahontan's Ethnography and Dialogues

Vestigial Nobility: Lafitau’s Comparative Ethnology

6. Rousseau’s Critique of Anthropological Representations

III. discursive oppositions The “Savage” after Rousseau

7. The Ethnographic Savage from Rousseau to Morgan

Vanishing Savages, Diminishing Nobility

Volney and the Ruins of Savagery

Morgan and the Ennobling Effects of Evolution

8. Scientists, the Ultimate Savage, and the Beast Within

European “wild Men": Linnaeus’s Sense of Wonder and an Acerbic Reaction

Darwin and the Savage at the End of the Earth

Scientific Racism: Lawrence’s Convincing Evidence

10. Participant Observation and the Picturesque Savage

Murray and the Theatrical Savage

11. Popular Views of the Savage

Chateaubriand in the Wilderness

Popular Ethnography and the Savage

IV. The return of the noble savage

13. Race, Mythmaking, and the Crisis in Ethnology

Anthropology and Nineteenth-century Racism

Ethnology at the Threshold: 1854-1858

14. Hunt’s Racist Anthropology

15. The Hunt-Crawfurd Alliance

17. The Myth of the Noble Savage

18 Crawfurd and the Breakup of the Racist Alliance

19 Crawfurd, Darwin, and the “Missing Link”

Epilogue: The Miscegenation Hoax

V. The noble savage meets the twenty-first century

20 The Noble Savage and the World Wide Web

21 The Ecologically Noble Savage

Front Matter

Title Page

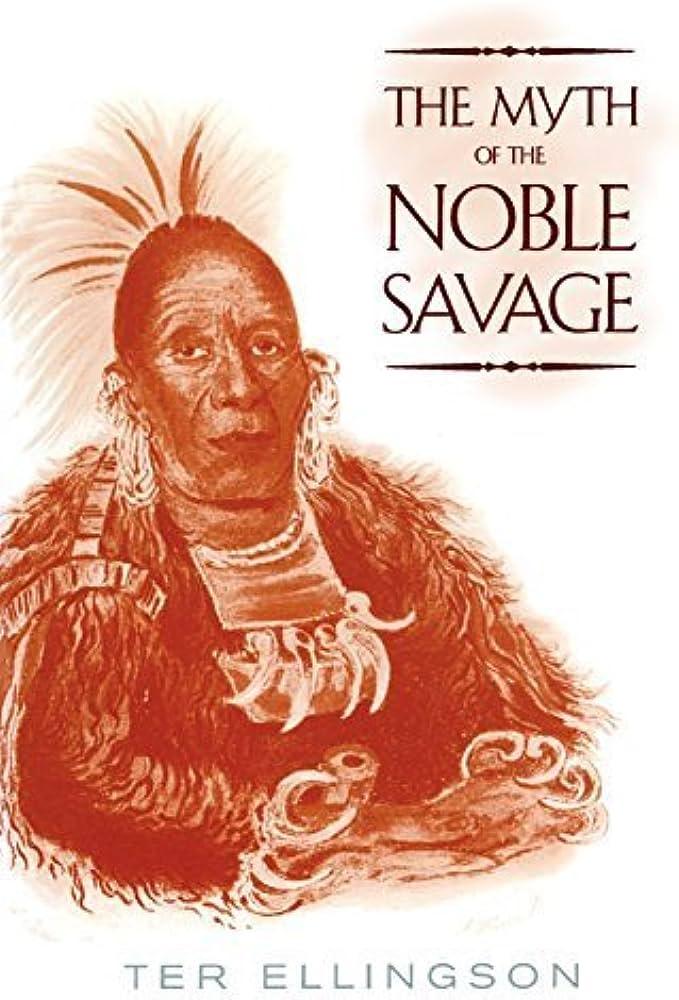

The Myth of the Noble Savage

Ter Ellingson

University of California Press

Dedication

To Linda

Note

Advice from a World Wide Web search engine, after finding more than 1,000 references to the "Noble Savage”:

Refine your search!

Illustrations

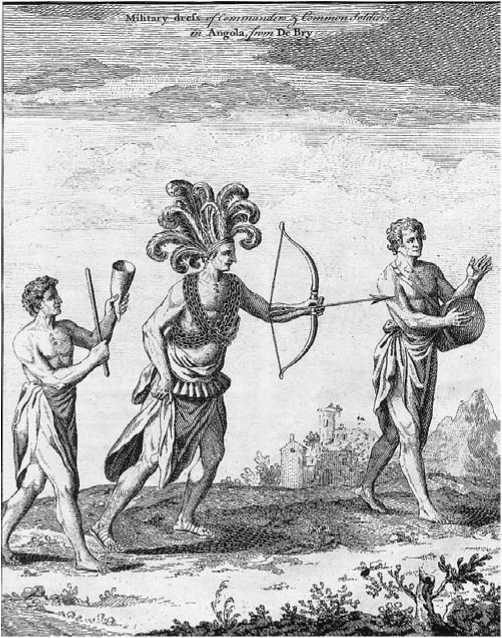

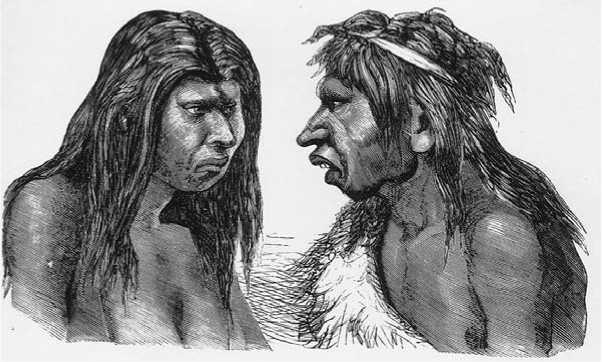

1. Savage beauty 9

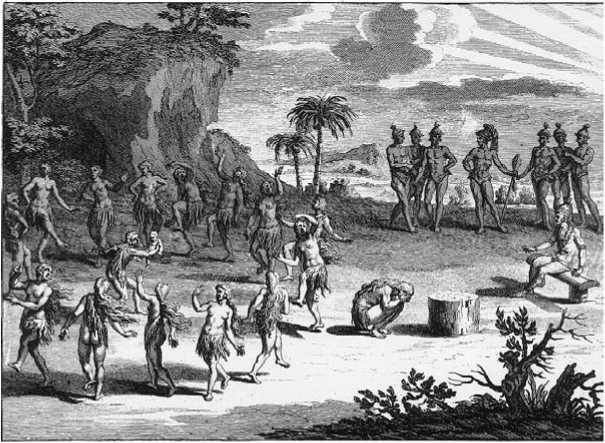

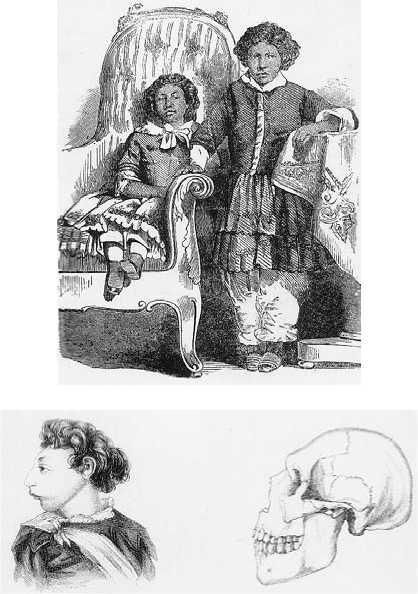

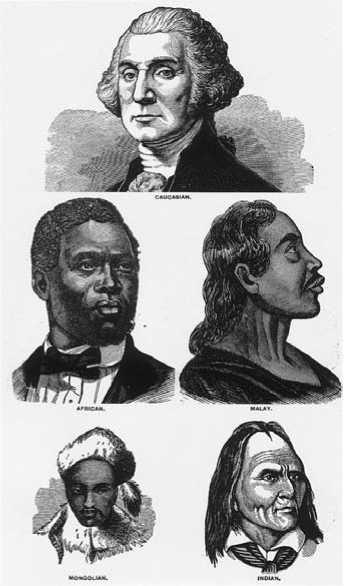

2. Savage cruelty 11

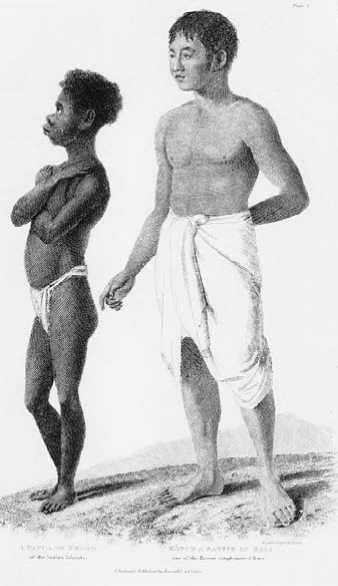

3. Noble hunter 21

4. Feudal-heroic nobility 35

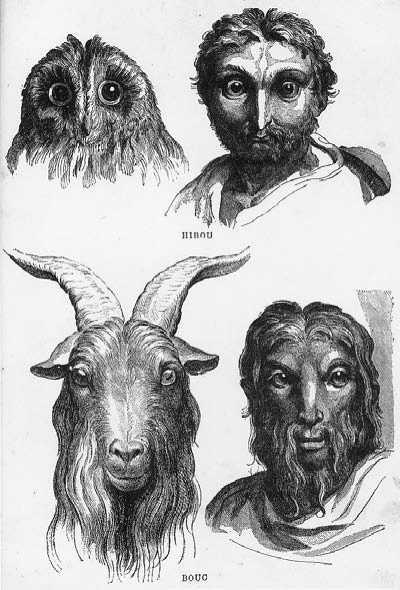

5. Savage religion 45

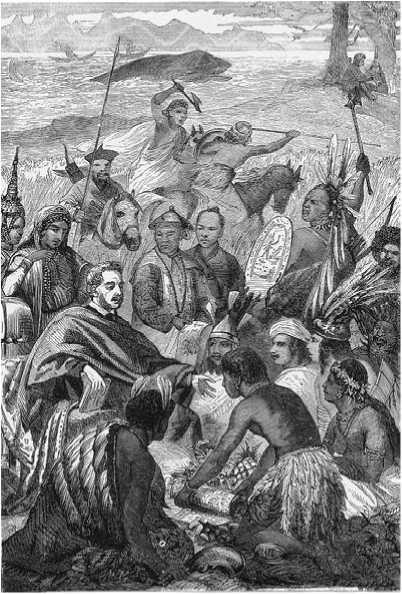

6. The savage confronts civilization 64

7. Bearskin and blanket 80

8. Caroline Parker, Iroquois ethnographer 99

9. The beast within 126

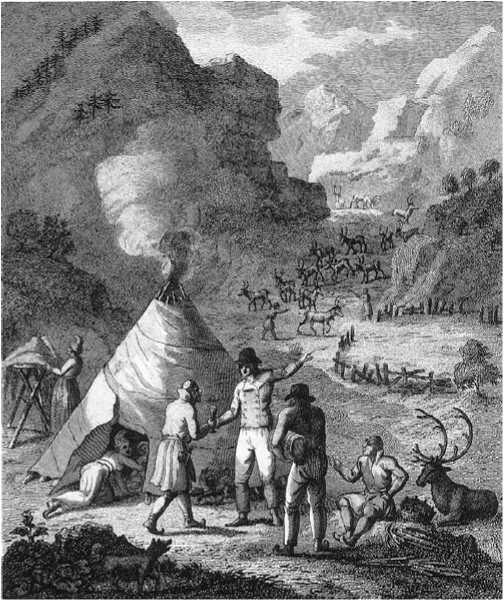

10. Saami camp 129

11. Acerbi’s discovery of the sauna 135

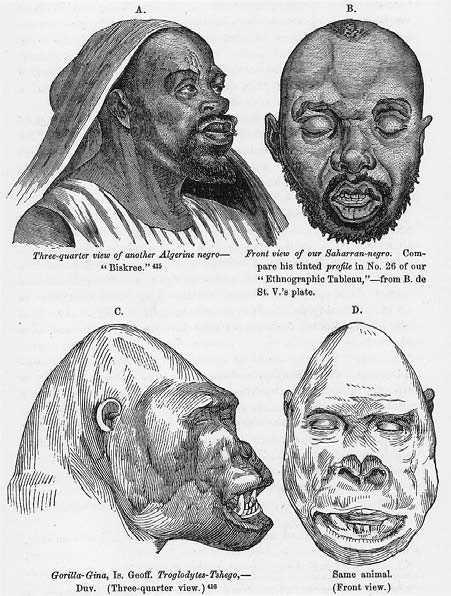

12. Science and the subhuman 152

13. Uncivilized races 158

14. Observing the observer 169

15. The picturesque "savage" 176

16. The colorful "savage" 191

17. "Dog-eaters" 193

18. Political imbalances 219

19. Savage degradation 233

20. The Aztec Lilliputians 235

21. "The Negro" as a natural slave 248

22. Fair and dark races 263

23. The triumph of anthropological racism 271

24. Paradigmatic savages 290

25. Racial hierarchies 303

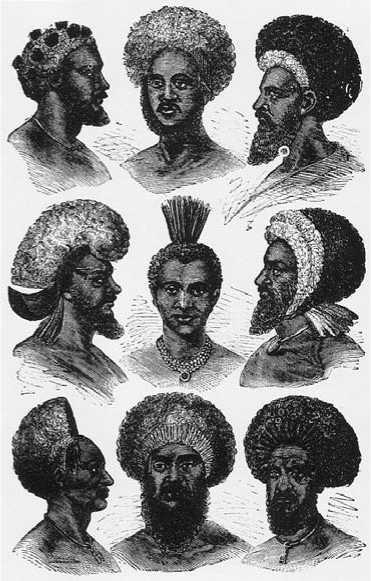

26. Fijian hairdos 316

Preface

The title of this book will inevitably create some confusion, for there are a number of dimensions in which the Noble Savage intersects the field of the mythical. The fundamental myth is that there are, or ever were, any actual peoples who were "savage," either in the term’s original sense of "wild" or in its later connotation of an almost subhuman level of fierceness and cruelty. The "Savage" and the "Oriental" were the two great ethnographic paradigms developed by European writers during the age of exploration and colonialism; and the symbolic opposition between "wild" and "domesticated" peoples, between "savages" and "civilization," was constructed as part of the discourse of European hegemony, projecting cultural inferiority as an ideological ground for political subordination. For most of the period from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, the American Indians constituted the paradigmatic case for the "savage," and the term was most widely applied to them. If "savage" is not always flagged by quotes in the following citations and discussions of writings of this period, it should never be regarded as unproblematic; the idea that any people, including American Indians, are or were "savages" is a myth that should long ago have been dispelled.

However, the primary source of the ambiguity built into the title of this book is less obvious and more insidious. This is because the title refers to a living, contemporary myth that most of us accept as fact; and because the myth itself deceives us by claiming to critique and offer an expose of another "myth," the existence of Savages who were really noble. The purported critique typically examines ethnographic or theoretical writings on "savage" peoples to problematize any potential claims to their "nobility." The supposed expose asserts that the "myth" of savage nobility was created in the eighteenth century by Jean-Jacques Rousseau as part of a romantic glorification of the "savage" to serve as a paradigmatic counterexample for constructing attacks on European society, and that belief in the existence of actual Noble Savages has been widespread ever since.

Many accept this combination of critique and expose as disproof of the "myth"; but the critique and the expose were themselves a deliberate mythological construction, projected at a particular time in the history of anthropology for a specific political purpose. It is this construction, the false claim of widespread belief in the existence of the "Noble Savage," inspired by Rousseau, that constitutes the myth that is the subject of this book.

The real myth, in other words, is what we have been deceived into thinking is the reality behind the myth. Herein lies the difficulty of our task, for it involves calling into question some of our most deeply rooted beliefs and confronting an unexpectedly insidious influence that still continues to shape the construction of our disciplinary identity. In so doing, we must inevitably consider the possibility that something we have long taken pride in as evidence of our own intelligent, critical thinking was in fact no more than our gullible acquiescence in a scholarly hoax—a hoax that has been perpetrated on us for political reasons that many of us would dislike intensely, if we understood them.

The chronological framing of the following narrative seems to me to present a clear and consistent story, but it may seem rather like a mystery novel, with the reader having to follow obscure clues until the solution is revealed at the end. In fact, there is no mystery behind the myth of the Noble Savage, other than its continued success and longevity. Serious investigators have known since the 1920s that Rousseau did not create the myth, but its source has never been satisfactorily identified. This is the first great problem we face, and it suggests a first step toward a solution.

In a preliminary approach to the question, we will find that the failure to discover the source of the myth has resulted from a misguided substan- tivist orientation that has sought its origin in objective fact, accepting that there must actually have been a real belief in something called the "Noble Savage" reflected in the ethnographic and related literatures. In fact, since the claim of the reality of belief in the Noble Savage is part of the construction of the myth itself, any attempt to find its substantive basis in the world "out there" reinforces the myth by playing the game defined by its own rules and leads away from a solution to the problem of its source. For example, Bruce Trigger and Wilcomb Washburn (1996: 1/1:72), while alluding to "the noble savage as conceptualized by Jean-Jacques Rousseau," nevertheless suggest that "the so-called myth of the Noble Savage was not simply a product of the salons of Paris, as is often claimed.” This is an important first step toward problematizing the substantive basis of the myth, but a clear critical understanding of it needs to be informed by an examination of its discursive foundations.

Thus, for example, it is hardly problematic that writers of the romantic period romanticized "savages,” since this must necessarily be true merely by definition: that "romantic” writers romanticized the subjects of their writings is simply a circular statement. We would undoubtedly find it more problematically interesting if, instead, they had never found "savage” characters worthy of embodying romantic themes; for such a case would provide evidence of a racism so obtuse as to suggest that the evolution of Europeans beyond a bestial level of intelligence had been very recent indeed. But to take all such cases as prima facie evidence of belief in the "Noble Savage” not only ignores important questions of the meanings of various modes of romantic representation but also distracts from the more important issue of what is meant by the attribution of nobility and savagery. Terms used as essentializing labels become self-validating and draw attention away from themselves to the content to which they are affixed. But to understand the Noble Savage, what is needed is not a faith in its reality supported by self-validating repetitions of a formula but rather a suspension of faith that can support a serious investigation of its origin and meaning.

The solution, as we will see, is to treat the Noble Savage as a discursive construct and to begin with a rigorous examination of occurrences of the rhetoric of nobility as it was applied by ethnographic and other European writers to the peoples they labeled "savages.” In focusing on the discursive rather than the substantive Noble Savage, which might be imagined to lurk behind any positive reference to "savages” anywhere in the literature, we will find that the term "Noble Savage” was invented in 1609, nearly a century and a half before Rousseau, by Marc Lescarbot, a French lawyer-ethnographer, as a concept in comparative law. We will see the concept of the Noble Savage virtually disappear for more than two hundred years, without reemerging in Rousseau or his contemporaries, until it is finally resurrected in 1859 by John Crawfurd, soon to become president of the Ethnological Society of London, as part of a racist coup within the society. It is Crawfurd’s construction, framed as part of a program of ideological support for an attack on anthropological advocacy of human rights, that creates the myth as we know it, including the false attribution of authorship to Rousseau; and Crawfurd’s version becomes the source for every citation of the myth by anthropologists from Lubbock, Tylor, and Boas through the scholars of the late twentieth century.

The chronological sequence of the following chapters also conceals the process followed in my own investigation of the myth. In fact, I began with a look at related historical problems in Rousseau’s writings. Having absorbed the myth as part of my professional training, I was at first incidentally surprised and then increasingly disturbed by not finding evidence of either the discursive or the substantive Noble Savage in Rousseau’s works. Finding this an interesting problem in its own right, I began to explore the secondary literature on the subject, beginning with Hoxie Neale Fairchild’s The Noble Savage (1928), finding confirmation of my readings of Rousseau but no satisfactory investigation of the myth’s real source.

Intrigued by how a myth that had been discredited for nearly seventy years had continued to dominate anthropological thinking and escaped serious critical examination for so long, I began to reexamine the ethnographic literature, where I had been convinced I had seen many references to the Noble Savage before. But all my critical reexaminations of ethnographic writings proved disappointing, until a systematic pursuit of possible earlier sources for Dryden’s well-known 1672 reference to the Noble Savage revealed what was obviously an original invention of the concept by Lescarbot some sixty-three years earlier. However, since Lescarbot’s Noble Savage was so different from that posited by the myth, further searching was necessary to find the reintroduction of the term and the construction of the myth itself.

Once again, since a temporal point of departure had been established by George W. Stocking, Jr.’s (1987: 153) identification of a reference to the myth in 1865 by John Lubbock, it was possible to establish a time frame for a search of the ethnographic and anthropological literature in the period between Rousseau and Lubbock. Examination of the sources most likely to have influenced Lubbock finally revealed a clearly original formulation of the myth as we know it in Crawfurd’s 1859 paper. With the double invention of the concept and the myth established, it seemed necessary to conduct yet another survey of selected works of the ethnographic and derivative literatures from the intervening period, but from the new perspective of a concept once privileged by its embeddedness in the myth and the culture of anthropology now having become problematized by the new critical framing of the survey.

Thus the core of this narrative is contained in the beginning and ending sections, parts 1 and 4; and a concise view of my basic argument may be found in those sections, particularly chapters 2 and 17. The intervening parts are a frankly experimental project in rereading the ethnographic literature from the perspective provided by examining the construction of the Noble Savage in Lescarbot and Crawfurd. This project is necessarily incomplete, given the vast extent of the literature, but equally necessarily undertaken if one is to understand the broad outlines of the historical developments that led from Lescarbot’s invention of the concept to its disappearance during the Enlightenment and its reemergence into the mainstream of anthropological discourse in Crawfurd’s construction of the myth in the mid-nineteenth century.

Parts 2 and 3 must therefore be taken as tentative explorations of a much larger field, where further readings will certainly reveal many more examples of the rhetoric of nobility than those presented in this brief survey. It is, of course, quite likely that such examples will necessitate some revisions of the argument presented here—after all, it would be reckless to claim that the concept of the Noble Savage does not and could not exist in the writings between Lescarbot and Crawfurd. But it seems quite unlikely that additional examples of the rhetoric of nobility would displace either or both authors from their key roles in developing the concept and the myth into powerful currents in the stream of anthropological discourse, which is the primary focus of this book. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out such a possibility. Thus, to help in the evaluation of such additional examples, I have suggested some general principles for a critique of the rhetoric of nobility in the introduction to part 2, with discussions of particular critical issues raised in conjunction with the discussions of specific works throughout parts 2 and 3.

Obviously, then, this is a book with an empty center. As a study in the history of ideas, it leaves a frustrating sense of the nonexistence of any discernible "idea" of the Noble Savage after its first invention by Lescarbot. As a study in the history of discourse, it turns away from opportunities for technical analysis of discursive forms to explore fields of changing meaning in the energizing currents of cultural, historical, and political implications of the rhetoric of nobility. But these strategies seem the only feasible approach in this first attempt at a critical study. Its central subject does not exist, being only an illusory construction resulting from the conjunction of contingent causal and contributory circumstances. As a scholar whose fieldwork has long been situated in Buddhist cultures where assertions of nonexistence and illusion often serve as normative characterizations of the state of the world and knowledge of it, this is entirely familiar, natural, and intellectually intriguing to me. For some, it may be unfamiliar and disconcerting. I hope, though, that others will find the exploration of the process of deconstructing nonexistent entities and illusions as rewarding an experience as I have found in completing this study.

Some of the most familiar names from the history of anthropology are in the following pages, as are many unfamiliar writers who have long faded into obscurity but who have played key roles in the construction of the Noble Savage. Even in the cases of well-known writers, however, our investigation leads us to consider little-studied aspects of their work; so in the end, both cases involve the exposition of material that is new and unfamiliar. For this reason, I make considerable use of citations, often fairly extensive, from the various authors studied, to allow them their own "voice" as far as possible, to present their ideas in adequate depth to avoid superficial impressions, and to gain some appreciation of the cultural and intellectual forces that shaped their ideas and rhetoric. As this study is an ethnography of other times rather than other places, and of other anthropologists rather than other races, I think this is what we owe them; and I find the attention to their viewpoints repaid by what they give us in return.

But I am too much a product of my own temporocultural environment to sit respectfully and silently by as they speak, without engaging them in conversation or debate, asking questions, and even shouting back at some egregious diatribe about the physical or mental inferiority of some racial group; or applauding the open-mindedness of Rousseau, Prichard, or Boas; or vacillating between appreciation and loathing for a complex personality such as John Crawfurd, perhaps the most likably despicable racist I have ever encountered. Some may find this frustrating, and they deserve a revisitation of the subject by authors with a more neutral, balanced viewpoint; but, in the meantime, it seems to me, neutrality and balance could hardly have been adequate sources of inspiration for the writing of a book such as this one.

There is a vast secondary literature on the wide range of periods and topics that must necessarily be touched on by a study of this subject, given the long history of its creation and its perpetuation into the present. Although considerations of space and the necessary priority of primary sources preclude extensive consideration of the scholarly literature in the following discussion, readers will find an enriched understanding of the subjects covered here by exploring some of the most important scholarly studies available. For the Noble Savage concept and myth, and the question of Rousseau’s authorship, the classic study is Fairchild’s The Noble Savage. More recent treatments are provided by works such as Gaile McGregor’s The Noble Savage in the New World Garden (1988) and Tzvetan Todorov’s

On Human Diversity (1993). For le bon sauvage in French literature, Gilbert Chinard’s L'Amerique et le reve exotique dans la litterature frangaise au XVIIe et XVIIIe siecle (1913) is an influential work that offers interpretations very different from those presented here.

Rousseau, like Darwin, is the subject of a publishing industry in his own right, and at least a considerable share of a lifetime could be spent exploring the scholarly literature on him and his ideas. Maurice Cranston (1982, 1991) provides the best available multivolume biography, still unfinished, that incorporates a great deal of recent scholarship in a balanced, analytic way. Likewise, Cranston’s translation of the Discourse on Inequality (Rousseau 1755b) may be the best available English rendition of the text that has been taken as emblematic of Noble Savage mythology. Some of the most important scholarly commentary on the issue, pro and con, is included in the works listed in the preceding paragraph. The issue of Rousseau’s influence on the development of anthropology, it seems to me, still awaits adequate scholarly treatment; but Michele Duchet’s Anthropologie et histoire au siecle des lumieres (1971) helps to situate his anthropological ideas in the context of other leading thinkers of the time without, of course, linking him to the generation of the myth of the Noble Savage.

For the Renaissance ethnography that gave birth to the Noble Savage concept, the available resources are more diverse. Margaret T. Hodgen’s Early Anthropology in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (1964) discusses many of the important issues and problems in the ethnography of the period, including the interpretation of "savage" cultures in terms of the myth of the Golden Age, a subject covered from a more general historical perspective in Harry Levin’s The Myth of the Golden Age in the Renaissance (1969). Renaissance ethnography has been given creative treatment by recent work in history, literary criticism, and cultural studies; two interesting and very different examples exploring themes covered in this study are Anthony Pagden’s The Fall of Natural Man (1982) and Stephen Greenblatt’s Marvelous Possessions (1991).

Even believers in the myth of the Noble Savage have long recognized the need to take note of the growing development, in the century after Rousseau, of increasingly negative representations of the "savage." Some have conceived this need in terms of a logically balanced opposition between the "noble" and the "ignoble Savage," an opposition given early popular currency by Mark Twain (cited in Barnett 1975: 71) and subjected to more comprehensive scholarly investigation in works such as Robert F. Berkhofer, Jr.’s The White Man's Indian (1978). Others, noting the real imbalance of positive and negative representations during this period, have focused their attention on the pervasively dominant imagery of the "ignoble savage.” The definitive work of the "ignoble savage” scholarship, Roy Harvey Pearce’s The Savages of America (1953; later retitled Savagism and Civilization, 1988), covers a wide range of ethnographic, philosophical, political, and popular writings over almost exactly the same historical time span as this study. Two more specialized works, Louise K. Barnett’s The Ignoble Savage (1975) and Ronald Meek’s Social Science and the Ignoble Savage (1976), explore the uses of negative representations of the "savage” in the fields of American literary fiction and Enlightenment European sociocultural evolutionary theory, respectively. A more broadly focused work, Olive P. Dickason’s The Myth of the Savage (1984), is useful because of its combination of critical analysis with historical and ethnographic surveys of French Canada, an area of considerable importance to this study, and its inclusion of an overview of the often-contentious subject of Indians who had visited Europe and their reactions to what they saw. Gordon Sayre’s Les Sauvages Americains (1997) is a wide-ranging exploration of the early ethnographic literature, with some provocative suggestions and interpretations that lend help in understanding the sometimes striking differences between representations of the "savage” in French and English literature. While most such recent studies explicitly or implicitly treat the savage as a constructed category, Andrew Sinclair’s The Savage (1977) argues that "savages,” in the etymological sense of "men of the forest,” represent an ancient part of the human heritage that has been drawn into increasingly oppositional polarity with civilization—thus according the category a unique sort of deeper metaphysical valorization than it receives in other studies, including this one.

For the process leading up to the construction of the myth of the Noble Savage in the context of the rise of anthropological racism in nineteenthcentury England, the single indispensable source is Stocking’s Victorian Anthropology (1987). Some of Stocking's shorter works are also very helpful, particularly "What’s in a Name?” (1971) and "From Chronology to Ethnology” (1973). The literature on race and racism is vast; but a recent historical survey of American racism, Audrey Smedley’s Race in North America (1993), provides an anthropological perspective. For American racist anthropology, which had considerable influence on the ideas and rhetoric of British racists such as Burke and Hunt, William Ragan Stanton’s The Leopard's Spots (1960) is a classic study despite its occasional tendency to idealize the scientific accomplishments of the American racists. George M. Fredrickson’s The Black Image in the White Mind (1971) provides some critiques and counterinterpretations for some of Stanton’s evaluations.

Stocking’s Race, Culture, and Evolution (1968) furnishes wider-ranging and more sophisticated treatment of important issues relating to race and racism in the history of European and American anthropology. For the leading opponents in the struggles over racism in the Ethnological and Anthropological societies, Stocking’s works contain the best available discussions of Prichard and James Hunt; and Amalie M. Kass and Edward H. Kass’s Perfecting the World (1988) is a well-researched biographical study of Thomas Hodgkin. For Crawfurd, who would influence the thought and discourse of anthropology for a century and a half by his invention of the myth of the Noble Savage, there is no scholarly study available.

Finally, a technical note: I have generally preferred to cite first editions, contemporary translations, and facsimile reprints to reproduce the style as well as the content of works covering a wide historical range. Sometimes, however, either because of accessibility or enhanced clarity for contemporary readers, I have chosen to cite modern scholarly editions and translations or use my own translations. In all cases, though, I have chosen a form of citation that differs from ordinary anthropological conventions by privileging historical over commercial chronology. In simple terms, this means that I choose the date of first publication for the primary citation, rather than the date the particular copy on my bookshelf happened to have first been offered for sale. Thus, for example, if I cite two English translations of Rousseau’s Discourse on Inequality, first published in 1755, they become Rousseau 1755a and 1755b. The actual publication dates of these particular editions, respectively 1761 and 1984, appear in a secondary position later in the citation. In primary position, they would visually suggest either the existence of two different Rousseaus writing identically titled works or a particularly long-lived individual; but their main problem is that Rousseau’s critics, such as Chinard (1913), would appear to antedate the work they criticize (Rousseau 1984), a confusion more likely to occur in cases such as Smith (1755) and Rousseau (1761), where one might be less likely to guess that the "earlier" work is a critique of the "later" one.

Assuming that most of you share my interest in understanding the development of a discursive exchange on the Noble Savage, which entails understanding who said what and when, I have chosen to render the sequence of events as transparent as possible by giving primary emphasis to the times when particular ideas were voiced and were heard. In most cases, this means primary citation of the date of first publication; but there are some exceptions. Where important new elements are introduced in second or later editions, these are cited separately from the first edition. And in part 4, where month-to-month developments in the political takeover of the Ethnological Society are of crucial importance, but the publication of papers was often delayed by two or more years, I cite key papers by the date that they were actually given before the society, rather than by the later date of their publication. Unpublished materials, of course, are cited by the date of their composition. If all this sounds complex and inconsistent, its goal—and, I hope, its result—is to provide a consistent interface that reveals as clearly as possible the complex sequence of events by which something as deviously powerful and debilitatingly consequential to anthropology as the myth of the Noble Savage was generated.

I owe particular thanks to Beverley Emery, Royal Anthropological Institute (RAI) Library Representative, and her colleagues at the Museum of Mankind, for facilitating my research in the RAI Archives in London. Research on topics related to this study has been supported by the Graduate School Research Fund and the Center for the Humanities at the University of Washington.

Introduction

The Myth of the “myth of the Noble Savage"

More than two centuries after his death, Jean-Jacques Rousseau is still widely cited as the inventor of the "Noble Savage”—a mythic personification of natural goodness by a romantic glorification of savage life— projected in the very essay (Rousseau 1755a) in which he became the first to call for the development of an anthropological Science of Man. Criticism of the Noble Savage myth is an enduring tradition in anthropology, beginning with its emergence as a formalized discipline. George Stocking (1987: 153) has cited a reference as early as 1865 by John Lubbock, vice president of the Ethnological Society of London, the first anthropological organization in the English-speaking world; and other early citations include such leading figures as E. B. Tylor (1881: 408) and Franz Boas (1889: 68). The critique extends throughout the twentieth century, appearing in the work of scholars such as Marvin Harris.

Although considerable difference existed as to the specific characterization of this primitive condition, ranging from Hobbes’s "war of all against all” to Rousseau's "noble savage,” the explanation of how some men had terminated the state of nature and arrived at their present customs and institutions was approached in a fairly uniform fashion. (Harris 1968: 38-39)

And it continues into the present. For example, a recent article begins with the assertion, "The noble savage, according to eighteenth-century French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, is an individual living in a ‘pure state of nature'—gentle, wise, uncorrupted by the vices of civilization” (Aleiss 1991: 91). Michel-Rolph Trouillot (1991: 26), taking a more complex historical position, nevertheless states, "Rousseau . . . thus formalized the myth of the ‘noble savage.'"

Clearly, in the 1990s the Noble Savage and Rousseau's purported role in its creation remains a leading critical concern both in anthropology and in the growing list of disciplines that take an interest in the ethnographic literature and the history of cross-cultural encounters between Europeans and non-Europeans. Where the Noble Savage is invoked, Rousseau's name is almost invariably found in close proximity, although sometimes with their linkage implied in ambiguous ways. Edna C. Sorber, for example, writes,

They probably didn't plan it that way, but the perpetrators of the "noble savage" concept in 18th and 19th century America were doing the rhetorical criticism that more specialized rhetorical critics were ignoring. While the followers of the Rousseau point of view may have originally been the philosophers, as writings on the American Indian came to dominate such discussions other considerations took precedence.

<sup>(1972: 227)

In a very few cases, Rousseau is identified not as the original author of the Noble Savage but rather as the most effective agent of its promotion. Bobbi S. Low (1996: 354), for example, writes, "Dryden (in The Conquest of Granada, 1672) seems to have been the first to use the term. Rousseau, of course, used the concept effectively to anathematize civilization"(cf. McGregor's discussion of Rousseau's role, below). But in most cases, attributions of authorship to Rousseau are straightforward and apparently unproblematic. Katherine A. Dettwyler (1991: 375) refers to "images of Rousseau's ‘noble savage' transported to the past"; and Michael S. Alvard (1993: 355 -56) charges that "Jean Jacques [ sic ] Rousseau's concept of the ‘Noble Savage' has been extended and re-defined into the ‘Ecological Noble Savage' by both conservationists and anthropologists." Even such a generally careful scholar as Stocking (1987: 17) remarks, "The ambiguous ‘noble savage' of Rousseau's ‘Discourse on Inequality' was not the only manifestation of primitivism or historical pessimism among the French philosophers of progress."

None of these authors apparently feels any need to support the claim of Rousseau's authorship with a citation; it is simply, unquestionably true, presumably one of those public-domain bits of information for which the citation is an implicit "Everyone knows . . ." After all, even the Oxford English Dictionary says:

Noble (4 a) Having high moral qualities or ideals; of a great or lofty character. (Also used ironically.) noble savage, primitive man, conceived of in the manner of Rousseau as morally superior to civilized man.

But like some other anthropological folklore, this particular invented tradition is not only wrong but long since known to be wrong; and its continuing vitality in the face of its demonstrated falsity confronts us with a particularly problematic current in the history of anthropology. A convenient point of entry to this current is Fairchild’s classic study, The Noble Savage. Fairchild, an avowed enemy of the Noble Savage myth and an outspoken critic of Rousseau’s influence on romantic thought, investigated Rousseau’s writings (Fairchild 1928: 120-39) and was forced to conclude, as an earlier examiner of Rousseau’s "supposed romanticism” (Lovejoy 1923) had implied, that the linkage of Rousseau to the Noble Savage concept was unfounded: "The fact is that the real Rousseau was much less sentimentally enthusiastic about savages than many of his contemporaries, did not in any sense invent the Noble Savage idea, and cannot be held wholly responsible for the forms assumed by that idea in English Romanticism” (Fairchild 1928: 139).

Those few scholars who, since Fairchild, have bothered to look critically at the question have come to the same conclusion. Thus, although anthropologists have generally tended to accept the legend of Rousseau’s connection with the Noble Savage more or less on faith, Stanley Diamond (1974: 100-1) points out his critical perspective and his avoidance of the term. Scholars of literary criticism and cultural studies who have examined the issue in any depth have reached similar or stronger conclusions. For example, Gaile McGregor, retracing Fairchild's investigation from a late- twentieth-century perspective, says,

Despite his undoubted influence, however, it is important to distinguish Rousseau’s own position on primitivism from popular assessments. As in Montaigne’s case, the text itself contains elements which are obviously inhospitable to an unadulterated theory of noble savagery. While he does indeed, in Moore’s words, lavish "uncommon praise on some aspects of savage life,” Rousseau’s overall estimate of that level of existence is far from enthusiastic. . . . Like Montaigne, then, Rousseau’s aim was basically relativistic. (1988: 19-20)

And Tzvetan Todorov (1993: 277) similarly concludes, "Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s thought is traditionally associated with primitivism and the cult of the noble savage. In reality (and attentive commentators have been pointing this out since the beginning of the twentieth century), Rousseau was actually a vigilant critic of these tendencies.”

So it seems clear that we must conclude that Rousseau’s invention of the Noble Savage myth is itself a myth. But this conclusion, unanimously supported by serious investigators and clear as it is, raises some obvious questions. If Rousseau did not create the concept of the Noble Savage, who did? How did it become associated in popular and professional belief with Rousseau, and with the origins of anthropology? And, perhaps less obviously, why has belief in a discredited theory lingered on for seven decades after the publication of a clear disproof, particularly among anthropologists themselves? Is there something in the nature of anthropology itself, either in its intrinsic nature or in its historically contingent construction, that requires such a belief?

I will suggest in the following pages that there is; that not only is everything we have believed about the myth of the Noble Savage wrong, but it is so because our profession has been historically constructed in such a way as to require exactly this kind of obviously false belief. In outlining this suggestion, I will advance some apparently contradictory proposals: that belief in the Noble Savage never existed but that the Noble Savage was indeed associated with both the conceptual and the institutional foundations of anthropology, and not only once but twice, in widely separated historical periods, both before and after Rousseau’s time; and finally, that there was indeed a single person who was the original source of both the Noble Savage concept and of the call for the foundation of a science of human diversity but that this person was not Rousseau.

A Rose as Represented by Another Name Might Stink

If Rousseau was not the inventor of the Noble Savage, who was? One who turns for help to Fairchild's 1928 study, a compendium of citations from romantic writings on the "savage,” may be surprised to find The Noble Savage almost completely lacking in references to its nominal subject. That is, although Fairchild assembles hundreds of quotations from ethnographers, philosophers, novelists, poets, and playwrights from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century, showing a rich variety of ways in which writers romanticized and idealized those whom Europeans of the period considered "savages,” almost none of them explicitly refer to something called the "Noble Savage.” Although the words, always duly capitalized, appear on nearly every page, and often several times per page, it turns out that in every instance, with four possible exceptions, they are Fairchild's words and not those of the authors cited. The myth of the Noble Savage suddenly seems very nebulous, and problematic in quite a different way than we might have expected.

But before concluding that the Noble Savage was a figment of the imagination or some kind of conceptual hoax, we should examine the apparent exceptions. Three of these date from after Rousseau's death. In Henry Mackenzie's novel Man of the World (1787), when a European captive who has lived several years with American Indians decides to return to civilization, his "imagination drew, on this side, fraud, hypocrisy and sordid baseness, while on that seemed to preside honesty, truth and savage nobleness of soul” (cited in Fairchild 1928: 92). While not an exact match, the wording is acceptably close, and the comparison of "savage nobleness” with civilized corruption seems to fit the myth as most have understood it. The comparison is, however, specifically identified as a construction of the imagination rather than as reality, and the context is not that of an idealization of the savage. For, as Fairchild (1928: 90-92) points out, Mackenzie places a noticeable emphasis on savage violence and cruelty, which seems incompatible with the Noble Savage myth. Furthermore, the passage leaves some doubt as to whether the construction "savage nobleness” implies equivalence or qualification: that is, might "savage” nobleness contrast with some other variety, such as "true nobleness”?

The other two cases are even more doubtful. In one, the wife of the poet Shelley describes the plot of one of his unfinished works written in 1822: "An Enchantress, living in one of the islands of the Indian Archipelago, saves the life of a Pirate, a man of savage but noble nature” (Fairchild 1928: 309). Here, despite the verbal similarity, the point is one of reference to qualities of an individual's nature rather than to man in a state of nature; and the "but” suggests an exceptional case that violates the normal opposition between "savage” and "noble” natures. The difference in implication of the application of the term "savage” to the pirate and to peoples living in a "state of nature” should be obvious enough to need no comment.

In the third case, Sir Walter Scott says in 1818 in The Heart of Midlothian: "One . . . stood upright before them, a lathy young savage. . . . Yet the eyes of the lad were keen and sparkling; his gesture free and noble, like that of all savages” (cited in Fairchild 1928: 317). Here again, despite the verbal resemblance, the nobility is of a different kind, a nobility of gesture; and the "savage” in question is actually a Scottish Highlander! Although Fairchild rightly points out, here and elsewhere, that attributions of savage wildness and natural goodness were often transposed from more exotic locales onto various groups of Europeans,1 he also points out that Scott showed a rather obvious disinterest in the purported nobility of more ethnographically remote peoples.

Given the problematic nature of these three cases, we seem drawn more strongly toward an impression that there is little support in the literature for the idea that there was widespread belief, or even any belief at all, in the existence of something actually called "the Noble Savage.” But is this really important? Why, after all, should we problematize the words "Noble Savage” rather than their conceptual content or objective field of reference? Isn’t this mere empty formalism? After all, isn’t there overwhelming evidence that "savages” were heavily laden by European writers with the baggage of romantic naturalism, which is the point of the critique, rather than the label attached to it?

But the fact is that both the label and the contents are problematic. In Fairchild’s survey of "exotic” and "romantic naturalist” literature, for example, one finds the label "Noble Savage” affixed to literary representations ranging from the most absurd parroting of Parisian salon discourse by Huron warriors to African slaves lamenting their lost freedom. Are these really equivalent cases of "romantic naturalism,” equally deserving of the critical scorn and derision implied by labeling them both "Noble Savage”?

In some of the cases Fairchild cites, "primitive” and "natural” ways of life seem so idealized and exalted that few readers could avoid wondering whether such paradises could ever exist on earth, or, if they did once, that anyone could ever exchange them for "civilization.” And in some cases, "civilization” takes on such a quasi-hellish character that one wonders how it could ever have developed at all, or prevented its victims from mass desertion to happier states of existence. But in other cases, even the slightest criticism of European cruelty or corruption, or the least hint that nonEuropean peoples might have any good qualities whatsoever, seems to qualify as "romantic naturalism,” to be labeled as yet a further instance of belief in the "Noble Savage.”

One can, of course, argue for the real merits of connecting such cases and maintain that any belief at all in things such as freedom or goodness is in reality nothing but romantic fantasy. But all such arguments, like the arguments against them, are necessarily problematic and require deliberate and careful construction. How much easier, instead, to have a readymade polemic label such as "the Noble Savage” that assumes the validity of the connection even as it heaps scorn on any imaginable opposition, and saves the work of constructing an argument by assuming what it purports to critique? It seems that, given the problematic nature of its field of reference, we have no other choice but to also seriously consider the problematic nature of "the Noble Savage” as a discursive construct. Neither its content nor its verbal form should be accepted at face value, without further question.

But as soon as we begin to consider the Noble Savage concept as a discursive construct rather than as a substantive given element of objective or commonsense reality, we begin to further problematize it. The term is rather obviously a forced union of questionable assumptions. That men could ever be either savage, that is, wild, or noble, that is, exalted above all others either by an environmentally imposed morality or by their station of birth, is equally questionable; that the two could be causally related is absurd. The absurdity precludes serious belief in the concept, exactly the point of their juxtaposition. The Noble Savage clearly belongs to the rhetoric of polemic criticism rather than of ethnographic analysis, or even of serious credal affirmation.

As a discursive artifact, the term is further problematic in that it would appear to belong almost exclusively to Anglophone culture, to the English language and its writers in Britain and North America. The expression is simply not widely used in other languages: compare, for example, Todorov’s (1993: 270) section called "The Noble Savage” in English translation, with "le Bon Sauvage,” literally "the good savage,” in the French original (Todorov 1989). A more striking comparison arises in juxtaposing the French, Spanish, German, and English abstracts of Georges Guille- Escuret’s "Cannibales isoles et monarques sans histoire” (1992: 327, 345): the English "noble savage” contrasts noticeably with bon sauvage, buen salvaje, and gute Wilde, all sharing attributions of goodness and wildness but lacking the highly charged polarities of the English term. And one wonders why the editors found it necessary to mark only the English term by framing it in quotes. Could it be that communication with English readers on this subject requires a dramatically highlighted emotional intensity? If so, where did that intensity, or the need for it, come from?

One might protest that le bon sauvage and "the Noble Savage” simply mean the same thing, that they are dictionary equivalents, and that translation would never be possible if strict logical equivalence and formal con- gruity were always demanded (see Church 1950; Carnap 1955). In fact, the assertion of identity may be true of their extensive meaning, in the sense of reference to the "same” object; but intensively, they say something very different about it and so represent their objects very differently. The French bon sauvage and its cognates express a gentle irony; the English "Noble Savage” drips with sarcasm, intensified by its obligatory framing in capitals and/or quotes. One usage embodies a critical stance that could, and sometimes does (see Atkinson 1924; Todorov 1989), include a dimension of critical appreciation; the other, a stance that is uncompromisingly hostile and polemic.

More specifically, nobility transcends mere goodness; it represents a more exalted state, and significantly, the exaltation implies an innate exaltation above other beings and their qualities. Nobility is a construction not only of a moral quality but also of a social class and social hierarchy. But is this not a contradictory association, given the supposed linkage of the term with eighteenth-century "romantic” advocates of egalitarian, democratic ideals? Perhaps the term represents a simple attempt to liberate by defeudalizing language, distinguishing "true” moral nobility from a class designation. Or perhaps the term’s apparent link to orders of hierarchy and dominance is more than superficial. A look at its historical usage suggests this is in fact the case.

The single clear citation of the term "Noble Savage” in either Fairchild (1928) or McGregor (1988), which is also cited as the term’s earliest occurrence by the Oxford English Dictionary, comes not from the romantic period or the eighteenth century but from John Dryden’s seventeenthcentury drama, The Conquest of Granada by the Spaniards:

I am as free as Nature first made man,

’Ere the base Laws of Servitude began,

When wild in woods the noble Savage ran.

(Dryden 1672: 34)

Here, the freedom of the noble savage is not only associated with wildness and nature, and contrasted with a baseness that must be implicitly attributed to civilization, but the latter is associated with servitude linked to law. The combination is specific and complex enough to suggest an underlying argument or a conceptual foundation not clarified in the lines themselves. Dryden’s words appear to be a poetic condensation of a preexisting construction that we must seek in earlier sources; a likely starting point would be the ethnographic sources on "savage” ways of life.

I. The birth of the noble savage

Figure i. Savage beauty.

Renaissance assimilations of non-European peoples to classical Greco-Roman ideals of innocence and beauty produced discursive and visual representations such as the myth of the Golden Age and Theodor De Bry's sixteenth-century portrait of African warriors as Greek nudes (De Bry, reprinted in Green 1745-47: 3:281, pl. 16).

1. Colonialism, Savages, and Terrorism

Figure 2. Savage cruelty.

Assimilation with the negative classical imagery of the Anthropophages, reinterpreted as New World "cannibals," led to discursive and pictorial emphases on the cruelty of "savage" peoples, as in Jacques LeMoyne's sixteenth-century depiction of infant sacrifice in Florida (LeMoyne, redrawn and printed in Picart 1712-31).

European ideas of the "savage" grew out of an imaginative fusion of classical mythology with the new descriptions that were beginning to be conceived by scientifically minded writers as "observations" of foreign peoples by Renaissance travel-ethnographic writers. In the century and a half after Columbus, such "observations," often quite descriptively accurate and perceptive, gained power through their polarization within a field of potentialities defined by the negatively and positively highly charged classicist identifications, respectively, of native Americans with the "Anthropophages," or man-eaters—now relabeled "cannibals" by identification with the newly discovered Caribs of the West Indies—and with the inhabitants of the mythological "Golden Age” (fig. 1).

In terms of their emotional impacts, the contrasting constructions of the cannibals and the Golden Age reflect outcomes of two opposing representational strategies: alienation from and assimilation to the familiar world of European experiences and values. In terms of the process of their construction, however, both reflect a common process of assimilation of the unfamiliar to the familiar; for, as Leonardo da Vinci (1489-1518: 1:29293) reminded artists of the period, monsters can only be constructed out of the animals we know. Thus both the cannibals and the Golden Age superimposed observations of unfamiliar peoples on idealized models drawn from Greco-Roman mythology, whether the idealization was given a negative or a positive valence. In turn, each became the locus for further assimilations of other negative or positive constructions. Where the actual practice of cannibalism was lacking, for example, human sacrifice, torture of prisoners, or any form of the "cruelty” inevitably found in human societies could fill its place in the axis of polarized representations, ensuring that all "savages” could be represented as at least some sort of virtual cannibals (fig. 2). Likewise, where the full litany of characteristics of the Golden Age (see below) was incomplete, almost any combination of its emblematic feature, nudity, with evocations of goodness and beauty could serve to construct the positive side of the polarization empowered by the underlying ideal of the Golden Age itself.

Although it would seem that the Golden Age, with its positive valence, should be the more relevant to our subject, in fact the more negative equation of "savages” with "cannibals” generated discourses of cultural relativism (e.g., Lery 1578; Montaigne 1588a) that would themselves be misperceived as representations of the "Noble Savage,” or at least as closely related to them.1 The Golden Age, in its turn, would generate many permutations that would reverberate through the centuries of changing discourses on the "savage.” We must take note of both concepts here to recognize their vitalizing force in representations of the "savage,” which, we must remind ourselves, given the horrific predominance of the imagery of cannibalism, were anything but generally positive, relativistic, romanticized, or "noble.”

But, about a century after Columbus, new conceptual and discursive alternatives would appear, including the quite unexpected and unlikely concept of the Noble Savage. The ideas both of the Noble Savage and of an anthropological science of human diversity grew out of the writings of these Renaissance European traveler-ethnographers. Although work by many scholars will be needed to confirm the ultimate origin of either concept, both can be traced at least to the beginning of the seventeenth century, where they appear together in Lescarbot’s (1609c) ethnography of the Indians of eastern Canada.

Lescarbot was a lawyer who, after having suffered setbacks in his Parisian legal practice, joined the Seigneur de Poutrincourt’s colonial expedition to the Bay of Fundy in eastern Canada, where he spent a year in 1606-7 living among the "Souriquois" (Mi’kmaq, or "Micmac") Indians (Biggar 1907: x-xv). In response to Poutrincourt’s invitation, Lescarbot said, "Not so much desirous to see the country ... as to be able to give an eye judgment of the land, whereto my mind was before inclined; and to avoid a corrupted world I engaged my word unto him" (1609c: 61-62). In the new colonial setting, the urban professional, friend of noblemen, found a new and unexpected self-realization:

I may say (and that truly) that I never made so much bodily work for the pleasure that I did take in dressing and tilling my gardens, to enclose and hedge them against the gluttony of the hogs, to make knots, to draw out alleys, to build arbours, to sow wheat, rye, barley, oats, beans, peas, garden-herbs, and to water them—so much desire had I to know the goodness of the ground by my own experience. So that summer’s days were unto me too short, and very often did I work by moonlight. (1609c: 43)

This experience moved Lescarbot to philosophical reflections on problems in the "corrupted world" of his own society:

But the Frenchmen and almost all nations at this day (I mean of those that be not born and brought up to the manuring of the ground) have this bad nature, that they think to derogate much from their dignity in addicting themselves to the tillage of the ground, which notwithstanding is almost the only vocation where innocency remaineth. And thereby cometh that everyone shunning this noble labour our first parents’ and ancient kings’ exercise, as also of the greatest captains of the world, seeking to make himself a gentleman at others’ costs, or else willing only to learn the trade to deceive men or to claw himself in the sun, God taketh away his blessing from us, and beateth us at this day, and hath done a long time, with an iron rod, so that in all parts the people languisheth miserably, and we see the realm of France swarming with beggars and vagabonds of all kinds, besides an infinite number, groaning in their poor cottages, not daring, or ashamed, to show forth their poverty and misery. (1609c: 59-60)

By contrast, Lescarbot found a personal epiphany that led to self-fulfillment in the three culturally and personally significant dimensions of Christian theology, Renaissance classicism, and feudal-aristocratic patronage:

Wherein I have cause to rejoice, because I was of the company and of the first tillers of that land. And herein I pleased myself the more, when I did set before mine eyes our ancient father Noah, a great king, great priest, and great prophet, whose occupation was to husband the ground, both in sowing of corn and planting the vine; and the ancient Roman Captain Seranus, who was found sowing of his field when that he was sent for to conduct the Roman army; and Quintus Cincinnatus, who all dusty did plough four acres of lands, bare-headed and open stomached, when the Senate’s herald brought letters of the dictatorship unto him; in sort that this messenger was forced to pray him to cover himself before he declared his embassage unto him. Delighting myself in this exercise, God hath blessed my poor labour, and I have had in my garden as fair wheat as any can be in France, whereof the said Monsieur de Poutrincourt gave unto me a glean. (1609c: 138-39)

But Lescarbot found a fascination at least equally great in the discovery of the "savages" who inhabited his new world: "Having never seen any before, I did admire, at the first sight, their fair shape and form of visage" (1609c: 84).

The attraction the Indians exercised on Lescarbot was certainly enhanced by the complex circumstances under which he encountered them. Far from being a first encounter with a pristine culture, the French-Indian relationship at the time of Lescarbot’s visit was the product of prolonged contact and increasingly sophisticated interactions. Although there was a hiatus in French colonial endeavors in Canada between Cartier’s explorations in the 1530s and 1540s and Champlain’s return there in the 1590s, the Indians had not remained isolated from European contacts. For a whole century, fishermen and traders of various nationalities, including French but most prominently Basque, had made yearly voyages to the Newfoundland banks and the Canadian coasts and drawn the Indians into increasingly profitable and complex trade networks and alliances. The more famous explorers whose names are known to history all mention these nameless fishermen and traders, and we may never know for sure who they were; but what they did is obvious by its results.

By the turn of the seventeenth century, when Lescarbot joined the pioneering colony in Acadia (Nova Scotia), the coastal Indians had developed trade networks with friendly peoples extending into the interior of the continent, and formed political alliances against potential and actual enemies and competitors, in pursuit of the increasingly profitable advantages of the fur trade with the Europeans. The competition had not yet developed into the international alliances with competing European powers, such as the famous French-Huron versus British-Iroquois alliances, that would grow up with Dutch and British expansion into New York and New England in the seventeenth century; but even the local competition among Indians for control of trade with transient Europeans and the initial French settlers was already intense. Some of the Indians began to appreciate the advantages of stabler, longer-term relationships with particular groups of Europeans and moved decisively to exploit the possibilities of the situation, making adjustments to their ways of life to accommodate their new strategies (for a useful overview, see Brasser 1978).

Thus, at the time of the settlement of Lescarbot’s colony in Acadia, the Mi’kmaq Indians, under the leadership of their politically skillful chief and shaman Membertou, were engaged in aggressive pursuit of the advantages of a closer alliance with the French. It was under these circumstances that Lescarbot came into close and prolonged contact with the Indians, as they and the French colonists pursued every available means of strengthening an alliance that both sides found advantageous to their own interests. It is no wonder, then, that increasing familiarity, but also the beginnings of a new and wonderful kind of friendship between such very different peoples, began to grow. Lescarbot describes the festive dinners of the colonists:

In such actions we had always twenty or thirty savages, men, women, girls, and boys, who beheld us in doing our offices. Bread was given to them gratis, as we do here to the poor. But as for the Sagamos [chief] Membertou and any Sagamos (when any came to us), they sat at table eating and drinking as we did; and we took pleasure in seeing them, as contrariwise their absence was irksome unto us. (1609c: 118-19)

Yet, while Lescarbot’s liking for Membertou and the Indians seems genuine enough, he recognized the complexity of the relationship and of their motives.

As it came to pass three or four times that all went away to the places where they knew that game and venison was, and brought one of our men with them, who lived some six weeks as they did without salt, without bread and without wine, lying on the ground upon skins, and that in snowy weather. Moreover, they had greater care of him (as also of others that have often gone with them) than of themselves, saying that, if they should chance to die, it would be laid to their charges to have killed them. And hereby it may be known that we were not (as it were) pent up in an island as Monsieur de Villegagnon was in Brazil.2 For this people love Frenchmen, and would all, at a need, arm themselves for to maintain them. (1609c: 119)

There can be little doubt that the Indians Lescarbot knew valued their relationship with the French settlers; and he gives several colorful instances of their positive actions, including their farewell to the departing colonists.

But it was piteous to see at his departing those poor people weep, who had been always kept in hope that some of ours should always tarry with them. In the end, promise was made unto them that the year following households and families should be sent thither, wholly to inhabit their land and teach them trades for to make them live as we do, which promise did somewhat comfort them. (Lescarbot 1609c: 139)

Is this merely the wishful thinking of ethnocentric Europeans, complacent in their own sense of cultural superiority? We must remember that the Mi’kmaq were pursuing an aggressive strategy of alliance with the French, apparently based on the principle that the stronger and more durable the connection was, the more they stood to gain. In arousing French hopes of their own amalgamation with colonial society, it seems that their strategy was quite successful in evoking a perception in their trading partners of the strength and permanency of the bonds between them.

The meanwhile the savages from about all their confines came to see the manners of the Frenchmen, and lodged themselves willingly near them: also, in certain variances happened amongst themselves, they did make Monsieur de Monts judge of their debates, which is a beginning of voluntary subjection, from whence a hope may be conceived that these people will soon conform themselves to our manner of living. (Lescarbot 1609c: 24)

It hardly needs to be said that Lescarbot’s perception of "a beginning of voluntary subjection” reflects a French rather than an Indian viewpoint. Rather than Lescarbot’s legalist vision of a French-style judge with absolute power over the subjects of the monarch he represents, the Indians probably placed de Monts more in the role of a tribal mediator in a dispute between equals, or perhaps even of a neutral referee such as other Northeastern tribes used for ball games and other sporting contests (Morgan 1851: 295 ff.). And in reflecting on the success of the Mi’kmaq strategy of courtship of the French alliance, we might also consider the propagandistic focus of Lescarbot’s writing, designed to encourage French settlers and allay their anxieties over the alien nature of the new world and its inhabitants by arousing expectations of their domesticability. Toward this end, he stresses the richness and comfort of the new land, the enjoyment of which was substantially enabled by the assistance of the Indians; and in so doing, he reveals something of the economic strategies and practices that facilitated the cooperation of French and Indians:

For our allowance, we had peas, beans, rice, prunes, raisins, dry cod, and salt flesh, besides oil and butter. But whensoever the savages dwelling near us had taken any quantity of sturgeons, salmons, or small fishes—item, any beavers, elans, carabous, (or fallow-deer), or other beasts . . . they brought unto us half of it; and that which remained they exposed it sometimes to sale publicly, and they that would have any thereof did truck bread for it. (1609c: 119)

Lescarbot's recognition of complexity and realism in the relationship continues in his analysis of the Indians' generosity.

For the savages have that noble quality, that they give liberally, casting at the feet of him whom they will honour the present that they give him. But it is with hope to receive some reciprocal kindness, which is a kind of contract, which we call, without name: "I give thee, to the end thou shouldest give me.” And that is done throughout all the world. (1609c: 100-1)

In this proto-Maussian characterization of the obligation inherent in the gift, the awareness of reciprocity, and its widespread occurrence in human life, we catch something of the way of thinking that led Lescarbot to become one of the first advocates of an anthropological science (see chap. 2). Indeed, his impressions of the Indians are pervaded by comparativist and relativist perspectives.

So we see that one selfsame fashion of living is received in one place and rejected in another. Which is familiarly evident unto us in many other things in our regions of these parts [Europe and France], where we see manners and fashions of living all contrary, yea, sometimes under one and the same prince. (1609c: 191)

And this comparative-relativist viewpoint leads Lescarbot again and again to draw unfavorable comparisons of European to Indian conduct and to criticize what he sees as corruptions and injustices in his own society. This is hardly surprising in a writer of the time, given the strong development of such themes by Renaissance ethnographers and humanist commentators on the "savage" such as Jean de Lery (1578) and Michel de Montaigne (1588a). Lescarbot is in many ways a typical Renaissance humanist writer: for instance, in his repeated questioning and occasional outright rejection of the claims of written authority (e.g., Lescarbot 1609c: 21, 49, 51), even as he constantly cites classical authorities as a source of comparative data and interpretive concepts. The dynamic tension between the use of classical authority for ethnographic comparisons, on the one hand, and observation as a challenge to authority, on the other, provides an energizing polarity in many Renaissance ethnographies; and so it does also in Lescarbot. His interest in classical Greek and Roman antiquity is expanded in his ethnographic description (1609c: 145 ff.) into a chain of comparisons of the ways of the "savages" with the classical civilizations of Europe—not, indeed, as a means of alienation through detemporalization (Fabian 1983) but rather as a means of bringing their experiences closer to those of Europeans, a kind of time-shifting manipulation to bridge the gaps of geographic distance and cultural contrasts.

Nevertheless, Lescarbot’s overall view of the Indians remains that of a committed advocate of colonial domination and, as such, is diametrically opposed to any project of idealization. Indeed, as a colonist confronting not only Indian alliances and friendship but also hostile peoples whose opposition sometimes violated European norms of the sanctity of property, and sometimes embraced the use of lethal force, Lescarbot presents one of the most remarkable rhetorical stances in the French colonial literature in his oscillation between strongly positive and negative rhetoric, the latter extending so far as the evocation of an incipient theory of terrorism.

We would have made them to eat of the grape, but, having taken it into their mouths, they spitted it out, so ignorant is this people of the best thing that God hath given to man next to bread. Yet, notwithstanding, they have no want of wit, and might be brought to do some good things if they were civilized and had the use of handy crafts. But they are subtle, thievish, and traitorous, and, though they be naked, yet one cannot take heed of their fingers, for if one turn never so little his eyes aside, and that they spy the opportunity to steal any knife, hatchet, or anything else, they will not miss nor fail of it; and will put the theft between their buttocks, or will hide it within the sand with their foot so cunningly that one shall not perceive it.

Indeed, I do not wonder if a people poor and naked be thievish; but when the heart is malicious, it is inexcusable. This people is such that they must be handled with terror, for if though love and gentleness one give them too free access, they will practise some surprise. (1609c: 103) The ideological justification and practical application of this policy of "terror" (terreur) is elaborated in Lescarbot’s narrative of an encounter with another group.

After certain days, the said Monsieur de Poutrincourt, seeing there great assembly of savages, came ashore, and, to give them some terror, made to march before him one of his men flourishing with two naked swords. Whereat they much wondered, but yet much more when they saw that our muskets did pierce thick pieces of wood, where their arrows could not so much as scratch. And therefore they never assailed our men as long as they kept watch. . . .

They were five [Frenchmen], armed with muskets and swords, which were warned to stand still upon their guard, and yet (being negligent) made not any watch, so much were they addicted to their own wills. The report was that they had before shot off two muskets upon the savages, because that some one of them had stolen a hatchet. Finally, those savages, either provoked by that or by their bad nature, came at the break of day without any noise (which was very easy to them, having neither horses, waggons, nor wooden shoes), even to the place where they were asleep; and, seeing a fit opportunity to play a bad part, they set upon them with shots of arrows and clubs, and killed two of them. The rest being hurt began to cry out, running towards the sea-shore. . . .

But the savages ran away as fast as ever they could, though they were above three hundred besides them that were hidden in the grass (according to their custom) which appeared not. Wherein is to be noted how God fixeth I know not what terror in the face of the faithful against infidels and miscreants, according to His sacred Word, when he saith to his chosen people [Deut. xi.25]: "None shall be able to stand before you. The Lord your God shall put a terror and fear of you over all the earth, upon which you shall march."

. . . The said Monsieur de Poutrincourt, seeing he could get nothing by pursuing of them, caused pits to be made to bury them that were dead, which I have said to be two; but there was one that died at the water’s side, thinking to save himself, and a fourth man which was so sorely wounded with arrow-shots that he died being brought to Port Royal; the fifth man had an arrow sticking in his breast, yet did scape death for that time; but it had been better he had died there, for one hath lately told us that he was hanged in the habitation that Monsieur de Monts maintaineth at Quebec in the great river of Canada, having been the author of a conspiracy made against his Captain Monsieur Champlain, which is now there. . . .

Nevertheless, the last duty towards the dead was not neglected, which were buried at the foot of the Cross that had been there planted, as is before said. But the insolency of this barbarous people was great, after the murders by them committed; for that as our men did sing over our dead men the funeral service and prayers accustomed in the Church, these rascals, I say, did dance and howled a-far off, rejoicing for their traitorous treachery, and therefore, though they were a great number, they adventured not themselves to come and assail our people, who, having at their leisure done what we have said before, because the sea waxed very low, retired themselves unto the barque, wherein remained Monsieur Champdore for the guard therof. But being low water and having no means to come a-land, this wicked generation came again to the place where they had committed the murder, pulled up the Cross, digged out and unburied one of the dead corpses, took away his shirt, and put it on them, showing their spoils that they had carried away; and, besides all this, turning their backs towards the barque, did cast sand with their two hands betwixt their buttocks in derision, howling like wolves: which did marvellously vex our people, which spared no cast pieces shots at them; but the distance was very great, and they had already that subtlety as to cast themselves on the ground when they saw the fire put at it, in such sort that no one knew not whether they had been hurt or no, so that our men were forced to drink that bitter potion, attending for the tide, which, being come and sufficient to carry them a-land, as soon as they saw our men enter into the shallop, they ran away as swift as greyhounds, trusting themselves on their agility. ... [S]o they set up the Cross again with reverence, and the body which they had digged up was buried again, and they named this Port Port Fortune. (1609c: 107-12)

Thus far Marc Lescarbot, lawyer, traveler, and farmer; friend to Mem- bertou, critic of civilized injustices, vivid chronicler of anticolonial resistance, and exponent of terrorism. He is certainly one of the most complex and interesting ethnographic writers of the French colonial enterprise. Even the abbreviated excerpt above might almost be the basis for a book in itself, so rich is it in the tropes and images of colonialism and resistance. The unexpected reframing by the Indians, for example, of the French psalm singing into one side of an Indian war-song duel between opposing tribes is as striking a case of "ethnographic" transformation as any European construction of Indians as the inhabitants of a "golden age"; and it must have been as shocking, in its own way, as the Indians’ "mooning" their French adversaries. But Lescarbot’s work would become even more complex and interesting when it passed beyond travel narrative to systematic ethnography, and to serious analysis of the nature of "savage" society.3

2. Lescarbot’s Noble Savage and Anthropological Science

Figure 3. Noble hunter. Because all Mi’kmaq men practiced hunting, enjoying a right that was restricted by law to the nobility in Europe, Lescarbot drew the comparative conclusion that “the Savages are truely Noble.” Eighteenthcentury portrait of a Mi’kmaq hunter by J. G. Saint-Sauveur and J. Laroque, courtesy of National Archives of Canada, negative no. C21112.

Lescarbot’s Histoire de la Novvelle France, a compendium of French New World voyages, including his own, together with his ethnographic treatise on the Indians, was published in Paris in 1609 after his return to France. An excerpted English translation of Lescarbot’s own voyage and ethnography, Nova Francia, was published in London the same year. With its appearance, the Noble Savage also made his entrance into English literature.

Now leaving there those Anthropophages Brazilians, let us return to our New France, where the Men there are more humane, and live but with that which God hath given to Man, not devouring their like. Also we must say of them that they are truely noble [emphasis added], not having any action but is generous, whether we consider their hunting, or their employment in the wars, or that one search out their domestical actions, wherein the women do exercise themselves, in that which is proper unto them, and the men in that which belongeth to arms, and other things befitting them, such as we have said, or will speak of in due place. But here one must consider that the most part of the world have lived so from the beginning, and by degrees men have been civilized, when that they have assembled themselves, and have formed commonwealths for to live under certain laws, rule, and policy. (Lescarbot 1609c: 276; emendations from 1609a: 257)

Here we seem to have the solution of our problem. The nobility of the Indians is associated with moral qualities such as generosity and proper and fitting behavior; and their primordial lifestyle is set off against later civilizations where men "have assembled themselves and have formed commonwealths for to live under certain laws, rule, and policy.” Clearly, this must be the source of Dryden's poetic image. To complete the impression that we have discovered the source of the full-blown Myth of the Noble Savage, we have Lescarbot's Contents heading for this part of the chapter: "The Savages are truely Noble” (Lescarbot 1609a: n.p.)! Moreover, we must reassess our hypothesis that the Noble Savage is a product of English rather than French literature, for the French text contains the same words: "Sauvages sont vrayement nobles” (Lescarbot 1609b: n.p.). And yet, surprisingly, a closer look at Lescarbot reveals that his Noble Savage is entirely different from the one known to later myth.

If there is a key to understanding Lescarbot's ideas, it is to constantly remind ourselves that he is a lawyer and that his profession shapes his perception and representation of his ethnographic experiences. Thus, for example, when dealing with other ethnographers' writings on America, and the ubiquitous Renaissance plagiarism that all too often resulted in the repetition of previous scholars' mistakes, he presents a legalist's viewpoint on the evaluation of evidence and the need for citation of sources: "One must needs believe, but not everything; and one must first consider whether the story is in itself probable or not. In any case, to cite one's authority is to go free from reproach” (1609d: 2:176).

"The Savages are truly Noble” is the concluding section of a chapter of Lescarbot's ethnography devoted to a subject—hunting—that we might perhaps not have expected as the context for the introduction of such a historically significant concept. Hunting was a primary means of subsistence in some American Indian societies and an important dietary supplement in agriculturally based societies, both for Indians and for European colonists. European writers tended to view it from a pragmatic standpoint, exaggerating its importance for some Indian groups, ignoring its widespread religious connotations (Lescarbot noted in passing the consultation of shamans in hunt planning), and generally treating it in utilitarian, technical terms. It seems an unlikely site for the construction of a concept such as the Noble Savage. Yet, if we recall that Lescarbot was a lawyer and reflect on the legal status of hunting in late Renaissance Europe, we can see why exactly this subject should have led him to reflect on matters of nobility (fig. 3).