The Ellul Forum

For the Critique of Technological Civilization

Issue #1 Fall 1988 — Debut Issue

Theological Method in Jacques Ellul

Freeom and Universal Salvation: Ellul and Origen

The Ethical Importance of Universal Salvation

Media Development Devotes Issue to Ellul

Forthcoming Ellul Publications

Issue #2 Nov 1988 — Ellul’s Universalist Eschatology

2nd Ellul Consultation Scheduled for November AAR

First Inter-American Congress on Philosophy and Technology

Conference on Democracy and Technology

The Growth of Minds and Cultures

Jesus and Marx: *From Gospel to Ideology: A Critique

The Importance of Eschatology for Ellul’s Ethics and Soteriology: A Response to Darrell Fasching

A Second Forum Response to Fasching

Bibliographic Notes on Theology and Technology

U.S.F. Monographs in Religion and Public Policy

Issue #3 Jun 1989 — Eller and Ellul on Christian Anarchy

The Presence of the Kingdom — Back in Print

A Reponse to Michael Bauman’s Review of Jesus and Marx

The Paradox of Anarchism and Christianity

Jacques Ellul, Anarchic et Christianisme

Jesus and Marx: From Gospel to Ideology, by Jacques Ellul

Bibliographic Notes on Theology and Technology

Bibliographic Report on Some Recent British Discussions Regarding Christianity and Technology

U.S.F. Monographs in Religion and Public Policy

Guidelines for Submissions to The Ellul Studies Forum

Issue #4 Nov 1989 — Judaism and Christianity after Auschwitz and Hiroshima

Un Chretien pour Israel, by Jacques Ellul

‘What I Believe’ by Jacques Ellul

After Auschwitz and Hiroshima: Judaism and Christianity in a Technological Civilization

From Anti-Judaism to Anti-Semitism and Auschwitz

Two Models of Faith and Ethics

The Sacred, the Secular and the Demonic: Genocide as Deicide

Ellul’s Contribution to Post-Shoah Christian Ethics

From Auschwitz to Hiroshima: The Demonic Autonomy of Technique

Beyond Auschwitz and Hiroshima: Welcoming the Stranger

On Christians, Jews, and the Law

Jacques Ellul, Le bluff technologique [The Technological Bluff].

Vernard Eller’s Response to Katharine Temple

Michael Bauman’s Response to Jacques Ellul

Bibliographic Notes on Theology and Technology

Issue #5 Jun 1990 — The Utopian Theology of Gabriel Vahanian

The Struggle for America ’s Soul: Evangelicals, Liberals, and Secularism. By Robert Wuthnow.

The Utopian Theology of Gabriel Vahanian

God and Utopia: The Church in a Technological Civilization

Dieu anonyme, ou la peur des mots [God Anonymous, or Fear of Words]

Salvation and Utopia: The Christ

Utopianism of the Body and Social Order The Spirit

Theology of Culture: Tillich’s Quest for a New Religious Paradigm

Law and Ethics in Ellul’s Theology

Notes on the Catholic Church and Technology

Guidelines for Submissions to The Ellul Studies Forum

Bibliographic Notes on Theology and Technology

Issue #6 Nov 1990 — Faith and Wealth in a Technological Civilization

Ellul Forum Conference at AAR, Nov. 17th

Money and Power by Jacques Ellul

Public Theology and Political Economy: Christian Stewardship in Modem Society

Faith and Wealth by Justo L. Gonzalez

The Stewardship of Life in the Kingdom of Death.

Some Reflections on Faith and Wealth

Luke 14:33 and the Normativity of Dispossession

The Context: The Cost Has Been Counted

Inadequacy of Resources in the Parables of w. 28–32

Can the Text Be Spiritualized?

Ellul Forum Meeting at the AAR Convention

Guidelines for Submissions to The Ellul Studies Forum

Issue #7 Jul 1991 — Jacques Ellul as a Theologian for Catholics

The Technological Bluff, by Jacques Ellul

Reason for Being: A Meditation on Ecclesiastes by Jacques Ellul

Into the Darkness: Discipleship in the Sermon on the Mount by Gene L. Davenport

Ethics After Babel by Jeffrey Stout. Beacon Press: Boston, 1988, xiv + 338pp.

Jacques Ellul and the Catholic Worker of the Next Century: Therefore Choose Life

Jacques Ellul: A Catholic Worker Vision of the Culture

Born-Again Catholic Workers: A Conversation between Jeff Dietrich and Katherine Temple

Jacques Ellul and Thomas Merton on Technique

Issue #8 Jan 1992 — Ivan Illich’s Theology of Technology

Forum – Ivan Illich: Toward a Theology of Technology

Health as One’s Own Responsibility: No, Thank You!

Against Health: An Interview with Ivan Illich

Promo for Narrative Theology after Auschwitz

Reflections on “Health as One’s Own Responsibility”

Recent & Forthcoming Works By Jacques Ellul

Issue #9 Jul 1992 — Ellul on Communications Technology

Ethics After Auschwitz and Hiroshima

Forum: Ellul on Communications Technology

Ellul on the Need for Symbolism

Symbolization as a Basic Human Need

Self-Symbollzatlon of la technique

Where Mass Media Abound, The Word Abounds Greater Still

Where Mass Media Abound Ethical Freedom Disappears — Or Does It?

The Word Abounds Greater Still

Promo for Narrative Theology after Auschwitz

Communication Theory in Ellul’s Sociology

Dancing in the Dark: Youth, Popular Culture and the Electronic Media

Mythmakers: Gospel, Culture, and the Media

Religious Television: Controversies and Conclusions

The Technological City: 1984 In Singapore,

Biblioraphic Notes on Theology and Technology

Issue #10 Jan 1993 — Technique and the Paradoxes of Development

A Facelift and Change of Philosophy for the Forum

Ellul Documentary Debuts in Holland

Forum: Technique and the Paradoxes of Development

Reflections on Social Techniques

Promo for Narrative Theology After Auschwitz

Jacques Ellul on Development: Why It Doesn’t Work

”Good” Development and Its Mirages

I. Development as Always “Good”

II. Sustainable Development as a Paradox

Technique, Discourse and Consciousness: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Jacques Ellul

Issue #11 Jul 1993 — Technique and Utopia Revisited

The Ellul Institute Founded in Riverside California

New Editorial Board Appointments and International Subscriptions

Wheaton College Establishes the Jacques Ellul Collection

The “Association Jacques Ellul” Formed in Bordeaux

Conference Planned in Bordeaux on “Technique and Society in the Work of Jacques Ellul”

Forum: Technique and Utopianism Revisited

Ellul and Vahanian on Technology and Utopianism

1) The Specificity of the West

Back to Ellul by Way of Weyembergh

Ellul and Vahanian: Apocalypse or Utopia?

Lire Ellul: introduction a I’oeuvre socio-politique de Jacques Ellul, by Patrick Troude-Chastenet

The Social Creation of Nature by Neil Evemden, (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992).

Narrative Theology After Auschwitz

The Ethical Challenge of Auschwitz and Hiroshima Apocalypse or Utopia?

Issue #12 Jan 1994 — Ethical Relativism and Technological Civilization

Colloquium Held In Bourdeaux: “Technique and Society in the Work of Jacques Ellul”

Advert for Narrative Theology After Auschwitz

Forum: Ethical Relativism and Technological Civilisation

Morality After Auschwitz by Peter Haas (Fortress, 1988)--

Moral Relativity in the Technological Society

Beyond Absolutism and Relativism: The Utopian Promise of Babel

From an Ethic of Honor to an Ethic of Human Dignity, Rights and Liberation

Narrative Theology after Auschwitz: From Alienation to Ethics

The Ethical Challenge of Auschwitz and Hiroshima: Apocalypse or Utopia?

The Ethical Challenge of Auschwitz and Hiroshima: Apocalpyse or Utopia?

Advert for The Ethical Challenge of Auschwitz and Hiroshima Apocalypse or Utopia?

Issue #13 Jul 1994 — In Memory of Jacques Ellul, 1912–1994

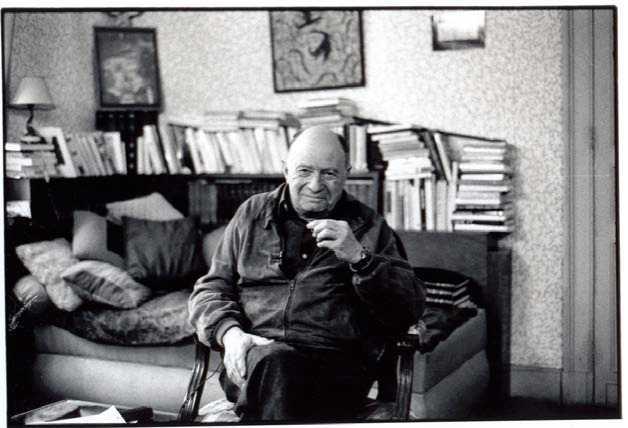

Editorial: Remembering Our Mentor and Friend, Jacques Ellul

Donations needed to Create and English Language Version of Film on Ellul

Donations Needed to Purchase Ellul’s House

New Members of the Editorial Board of the Ellul Forum

Forum: A Sermon by Jacques Ellul

Jacques Ellul, Courage, and the Christian Imagination

Thinking Globally, Acting Locally: In Memory of Jacques Ellul

Ellul’s Prophetic Witness to the Academic Community

Anarchy and the Political Illusion

Holiness vs Technology and the Sacred

Jacques Ellul — The Little Giant

An Address to “Master Jacques”

Ellul’s Response to the Symposium in his Honor at the University of Bordeaux, November 1993

Issue #14 Jan 1995 — Frederick Ferré on Science, Technology, and Religion

The One Best Way of Technology?

Hellfire and Lightning Rods: Liberating Science, Technology and Religion

Advert for Hellfire and Lightning Rods

Forum: Metaphors and Technology

Technology as Mirror of Humanity

Technology as Lens of Humanity

Technology as Incarnate Knowledge

Technology as Incarnate Values

Response to Frederick Ferre’s “New Metaphors for Technology,”

Language and Technology: A Reply to Robert S. Fortner

The American Hour: A Time of Reckoning and the Once and Future Role of Faith,

Meeting of the Jacques Ellul Association Held in Bordeaux

Retrospective on Jacques Ellul at Annual SPT Meeting in April

Issue #15 July 1995 — Women and Technology

The Coming of The Coming of the Millennium

Women and Technology: A(nother) Crisis of Representation

Women and Public and Private Space

Women and The “Science of Technology”

The Struggle for New Stories about Technological Woman

Stories Women Tell About Technology

The Symbolic Function of ‘Technique’ As Ideogram In Ellul’s Thought

Ellul’s Phenomenology of Technique

Gender on the Line: Women, The Telephone, and Community Ufe

Issue #16 Jan 1996 — The Ethics of Jacques Ellul

Donations for the Ellul Publications Project

Upcoming Programs on Jacques Ellul and Ian Barbour

Forum: The Ethics of Jacques Ellul

The Concept of “the Powers” as the Basis for Ellul’s Fore-ethics

Citizens Against the Administration

Ellul’s Ethics and the Apocalyptic Practice of Law

The Apocalyptic Practice of Law

Sur Jacques Ellul, edited by Patrick Troude-Chastenet

Thinking Through Technology: The Path between Engineering and Philosophy,

Issue #17 Jul 1996 — Ian Barbour on Religion, Science, and Technology

Advert for The Coming of the Millennium

Forum: Ian Barbour on Religion Science & Technology

The Gilford Lectures 1989–1991

Norms and the Man: A Tribute to Ian Barbour

Ellul and Barbour on Technology

Resist the Powers -with Jacques Ellul,

Issue #18 Jan 1997 — Lewis Mumford, Technological Critic

Ellul/lllich Conference on Education and Technology

New Courses from Schumacher College in England

Forum: Lewis Mumford. Technological Critic

Updating the Urban Prospect: Using Lewis Mumford to Critique Current Conditions

Mumford and McLuhan: The Roots of Modern Media Analysis

Sections from: The Coming of the Millennium: Good News for the Whole Human Race

Advert for The Coming of the Millennium: Good News for the Whole Human Race

Sources and Trajectories: Eight Early Articles by Jacques Ellul that Set the Stage

The Coming of the Millenium: Good News for the Whole Human Race

Issue #19 Jul 1997 — Technique and the Illusion of Utopia

Conference on “Education Technology” Held at Penn State

Journal Honors the Work of Jacques Ellul

Forum: Technique and the Illusion of Utopia

Singapore: Technique and the Illusion of Utopia

One Party, One Power, One Provider of Security

Issue #20 Jan 1998 — Tenth Anniversary Issue

About the 10th Anniversary Issue

Forum: From Ellul to “Picket Fences”

Mass Media in Jacques Ellul’s Technological Society

The Dialogic Nature of “Cross Examination”

10th Anniversary Forum: The Influence of Ellul

My Encounter with Jacques Ellul

Ellul and the Sentinel on the Wall

The Subversion of Christianity

Reflections on Ellul’s Influence

Jacques Ellul. Silences: Poemes.

Issue #21 Jul 1998 — Thomas Merton and Modern Technological Civilization

Manzone, Gianni. La liberta cristiana e le sue me-diazioni sociali nelpensiero di Jacques Ellul.

Forum: Thomas Merton’s Critique

Contemptus Mundi: Thomas Merton’s Critique of Modern Technological Civilization

MERTON’S CRITIQUE OF MODERNITY

Technology and the Myth of Progress

Failure of Organized Religion in an Organized Society

MERTON’S POSTMODERN CONTEMPLATIVE VISION

The Role of the Contemplative Lite

Issue #22 Jan 1999 — Conversations with Jacques Ellul

Advert: New from Scholars Press

Forum: Jacques Ellul in Conversation with Patrick Troude-Chastenet

Jaques Ellul: on Religion, Technology and Politics Converations with Patrick Troude-Chastenet

From Chastenef s Introduction:

Issue #23 Jul 1999 — Jacques Ellul on Human Rights

Advert: New from Scholars Press

Human Rights and the Natural Flaw

The Common Theoretical Roots of Modern Liberal Rights Theory, Modern Technique & the Modem State.

Rights as a Distninctive & Potentially Dangerous Feature of Modem Law

Technique, the State and the Demand for Rights

Human Rights and The Natural Law

Jaques Ellul and Human Rights — A Short Response to Sylvain Dujancount

Issue #24 Jan 2000 — Academics on a Journey of Faith

Science and Faith — A Personal View

Other Examples of Divine Guidance

Beginning research in photovoltaics.

Issue #25 Jul 2000 — Ellul in the Public Arena

Jacques Ellul: 20th century prophet for the 21st century?

The Trend Toward Virtued Christianity

Jacques Ellul’s Influence on the Cultural Critique of Thomas Merton

Issue #26 Jan 2001 — Jacques Ellul and Bernard Charbonneau

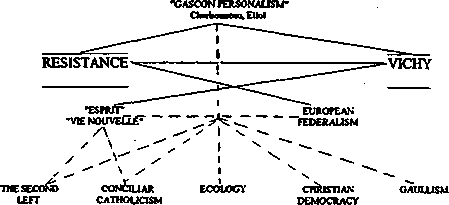

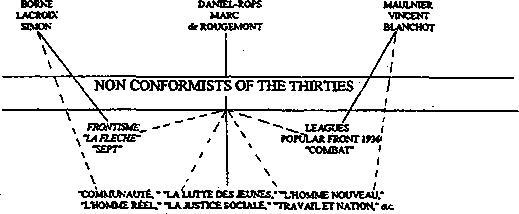

Jacques Ellul and Bernard Charbonneau

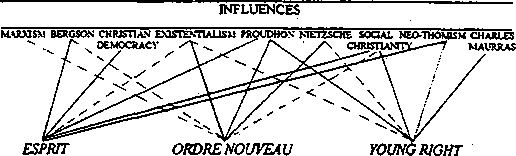

Bernard Charbonneau and the Personalist Context in the 1930s and Beyond

Patrick Chastenet Remembers Jacques Ellul

The Labyrinth of Technology by Willem H. Vanderburg, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000

Jacques Ellul: An Annotated Bibliography of Primary Works by Joyce Main Hanks

International Jacques Ellul Society

Issue #27 Jul 2001 — Ellul and Social Theorists

Include the Iconoclast: The Voice of Jacques Ellul in Contemporary Criticism

Technology as Magic: The Triumph of the Irrational by Richard Stivers

Issue #28 Jan 2002 — September 11, 2001

September 11th, 2001: On Violence, Divine and Human

The Dysfunctions of a Global Technological Era

Terrorisme international et communication politique dans les societes techniciennes

1. Images du pouvoir et pouvoir des images

II. La riposte: 1’Afghanistan bombarde au nom de la liberty

International Jacques Ellul Society

Issue #29 Jul 2002 — Rethinking Ellul’s Theory on the Role of Technology

Religiosity and the Sacred in Postmodern America

The Two Faces of Religiosity in Postmodern Society by Darrell J. Fasching

Issue #30 Dec 2002 — Ellul and Utopia

Jacques Ellul and Technological Utopia by Myung Su Yang

Whether Technology Is Autonomous or Not Matters

Technology Becomes the Only Ideology

The Technical Phenomenon Requires Changes in Religion

Accept the World Fundamentally

Ellul and Technological Utopianism

Myung Su Yang’s Challenge to Ellul

Yang’s Account of Ellul’s Thesis

Yang’s Utopian Critique of Ellul

A Response to Myung Su Yang’s Critique

Utopia and Mope: JLtResponse to Jacques Tdfrd and Mchnotoflical Utopia J. ‘Westey ‘Baper

International Jacques Ellul Society

Issue #31 Spring 2003 — Remembering Ivan Illich and Katharine Temple

Information on The Editorial Board & More

Fascinated by the Instruments of Power

Jacques Ellul—the Word of God in a World of Technique

En memoria de Ivan Illich, un anarquista entre nosotros by Carl Mitcham

In Memoriam: Ivan Illich, 1926 — 2002

A Note on the Death of Ivan Illich

The Death of Ivan Illich: A Personal Reflection

Harvard and the Unabomber: The Education of An American Terrorist

Advert: The Jacques Ellul Special Collection at Wheaton College

Advert: International Jacques Ellul Society

Seven Valuable Ellul Resources

Issue #32 Fall 2003 — Violence, Terrorism, and Technology

Information on The Editorial Board & More

Ellul on Violence and Just War

Beyond Cyberterrorism: Cybersecurity in Everyday Life by Dal Yong Jin

Cultural Aspects of Cyberterrorism

Cybersecurity in Everyday Life

Advert: You Can Help Build the Movement

Surveillance After September 11: Ellul and Electronic Profiling by David Lyon

Advert: Make Payments to IJES Electronically?

Issue #33 Spring 2004 — Jacques Ellul Today

Information on The Editorial Board & More

A Look at Ellul the Biblical Scholar

Content in Ellul’s Commentaries

New Metamorphoses of Bourgeois Society

Advert: Make Payments to IJES Electronically?

Nouvelles metamorphoses de la societe bourgeoise

Advert: International Jacques Ellul Society

Issue #34 Fall 2004 — Jacques Ellul on Sports

Information on The Editorial Board & More

Sport, Technique, & Society: Ellul on Sports

Sport, technique et societe Le sport vu par Jacques Ellul

Advert: Make Payments to IJES Electronically?

Enough: Staying Human in an Engineered Age by Bill McKibben.

Perspectives on Our Age: Jacques Ellul Speaks on His Life and Work Edited by Willem H. Vanderburg

Advert: Ellul Forum Back issues

Advert: International Jacques Ellul Society

Political Illusions & Realities

Issue #35 Spring 2005 — René Girard and Jacques Ellul

Information on The Editorial Board & More

Christianity, Violence, & Anarchy: Girard and Ellul

Advert: International Jacques Ellul Society

A Conversation With Rene Girard

Clever as Serpents: Business Ethics and Office Politics

Issue #36 Fall 2005 — Ellul and the Bible

Information on The Editorial Board & More

Jacques Ellul as a Reader of Scripture

Ellul on Scripture and Idolatry

Advert: IJES E-mail & Payment Info

Judging Ellul’s Jonah by Victor Shepherd

In Review: Tresmontant, Vahanian, Mailot, & Chouraqui

Gabriel Vahanian, Anonymous God

Advert: International Jacques Ellul Society

Issue #37 Spring 2006 — Propaganda and Ethics

Information on The Editorial Board & More

Problems in Ellul’s Treatment of Propaganda

Semantics and Ethics of Propaganda

Digital Matters: The Theory and Culture of the Matrix

Advert: International Jacques Ellul Society

Issue #38 Spring 2006 — The Politics of Jacques Ellul

Information on The Editorial Board & More

The Political Thought of Jacques Ellul A 20th Century Man

“Necessary” Revolution & Ascetic Socialism

Jacques Ellul on Politics & the State

How Ellul Influenced My Political Thought and Behavior

The Political Illusion by Jacques Ellul

Advert: International Jacques Ellul Society

Suspicion, Accusation, Fragmentation by David W. Gill

Issue #39 Spring 2007 — The Ethics of Jacques Ellul

Information on The Editorial Board & More

Jacques Ellul’s Ethics: Legacy and Promise

Preserving and Extending Ellul’s ethical legacy

A Deeper Understanding of Character and Virtue in Ethics

A Better Understanding of Individual and Community in Ethics

Jacques Ellul on Ethics & Morality

Appendix: Characteristics of the Sacred and the Holy

Ecologie et liberte: Bernard Charbonneau precurseur de l’ecologie politique.

Darrel Fasching & Dell DeChant Comparative Religious Ethics: A Narrative Approach

Ellul’s Technique, Wikinomics, & the Ethical Frontier

Advert: International Jacques Ellul Society

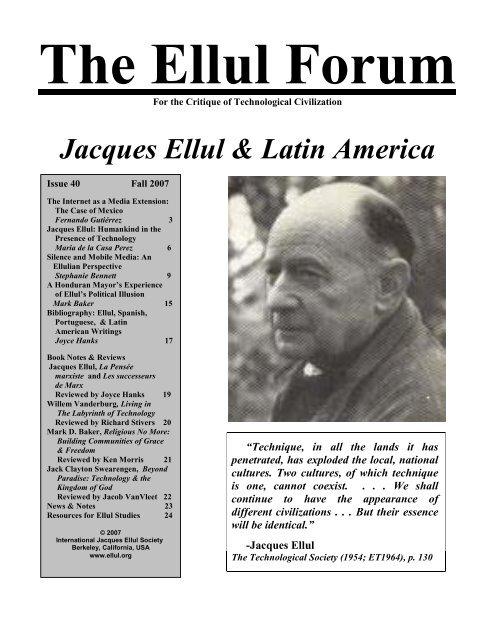

Issue #40 Spring 2007 — Jacques Ellul and Latin America

Information on The Editorial Board & More

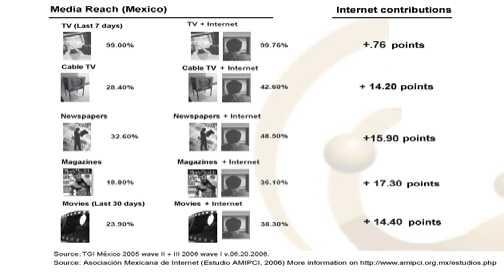

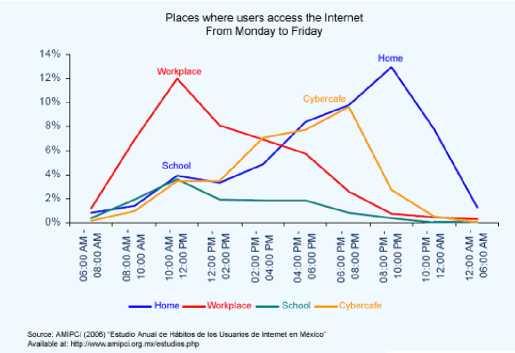

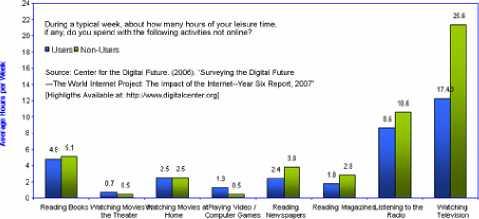

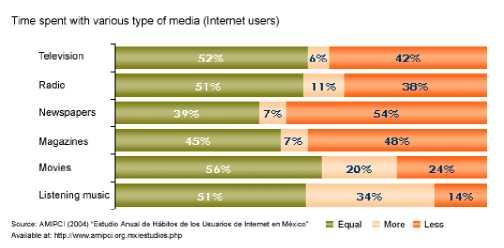

The Internet as a Media Extension: The Case of Mexico

Jacques Ellul: Humankind in the Presence of Technology

Silence and Mobile Media: An Ellulian Perspective

A Honduran Mayor’s Experience of Ellul’s Political Illusion

Selected Bibliography prepared by Joyce Hanks, University of Scranton

La pensee marxiste & Les successeurs de Marx Reviewed by Joyce Hanks

Living in the Labyrinth of Technology

Religious No More: Building Communities of Grace & Freedom

Beyond Paradise: Technology and the Kingdom of God

Advert: International Jacques Ellul Society

Issue #41 Spring 2008 — Islam and Religion

Information on The Editorial Board & More

Religious Postmodernism In An Age of Global Conflict by Darrell J. Fasching

Violence and the Sacred: Defending the Center

”Passing Over”: A Postmodern Spiritual Adventure for a New Age of Globalization

Tolstoy, Jesus, and “Saint Buddha”: An Ancient Tale with a Thousand Faces

The Children of Gandhi: An Experiment in Postmodern Global Ethics

The Story of Babel: A Postmodern Tale for an Age of Global Conflict

Jacques Ellul: The Influence of Islam On Christianity

Ecclesiastical and Political Authority

The Reception of Jacques Ellul’s Critique of Technology: An Annotated Bibliography

Hope in the Thought of Jacques Ellul

Shades of Loneliness: Pathologies of a Technological Society

Advert: International Jacques Ellul Society

Issue #42 Fall 2008 — Practical Politics

Information on The Editorial Board & More

The Political Path & the Road to God

Beneath the Froth: Witnessing to the Powers by Chuck Fager

What Divides Us & What Unites Us

Teaching, Thinking, & Friendship

Libertarian with Soul & Conscience

Moderation amidst Polarization

Advert: Make Payments to IJES Electronically?

Secularization & Cultural Criticism: Religion, Nation, & Modernity

Electing Not to Vote: Christian Reflections on Reasons for Not Voting

Advert: International Jacques Ellul Society

Issue #43 Spring 2009 — Ellul in Scandinavia

Information on The Editorial Board & More

The Brave New World of Virtual Entertainment

From the Global Village to Discarnate Man

Discarnate Man, La Technique, and Extreme Science—Technocalypse Now!

The Survival of Culture: “The Kindred Points of Heaven and Home”

Particular cultures — world culture

Green Politics Is Utopian by Paul Gilk

Advert: Make Payments to IJES Electronically?

Advert: International Jacques Ellul Society

Issue #44 Fall 2009 — Ellul, Capitalism, and the Workplace

Information on The Editorial Board & More

Capitalism in the Thought of Jacques Ellul: Eight Theses

Market Capitalism: The Religion of the Market & its Challenge to the Church

The myth of the market and doctrines of its transcendence

Doctrines of the market: cosmology, anthropology, and salvation

Market practices and institutions: advertising as evangelism and malls as sacred spaces

The Triumph of the Image Over Reasoning

From Faith to Fun: the Secularization of Humor by Russell Heddendorf

Advert: International Jacques Ellul Society

Advert: Make Payments to IJES Electronically?

Issue #45 Spring 2012 — Ellul in the Undergraduate Classroom

Information on The Editorial Board & More

Encountering Jacques Ellul on His Own Terms

A True Solidarity: Christian Community in the Thought of Jacques Ellul

The Jacques Ellul Special Collection at Wheaton College by David Malone

Advert: International Jacques Ellul Society

Advert: Make Payments to IJES Electronically?

Issue #46 Fall 2012 — Technique, Ellul, and the Food Industry

Information on The Editorial Board & More

IF WE SERVE THE GOD OF PRODUCTIVITY IS THERE ROOM FOR JESUS?

II. Does Technology Provide Freedom for the Farmer?

III. Violation of the Sacredness of Land through the Distraction of Technology

IV. An Alternative Business Model for Farmers

Jacques Ellul & Wendell Berry on an Agrarian Resistance by Matthew Regier

The Omnivore’s Dilemma & In Defense of Food Reviewed by Mark D. Baker

Advert: Make Payments to IJES Electronically?

Advert: International Jacques Ellul Society

Issue #47 Spring 2011 — Pop Culture, Jacques Ellul, and Thomas Merton

Information on The Editorial Board & More

The Emerging Field of Religion and Popular Culture

Pop Culture’s “New Demons” Obama, the Sacred, and Civil Religion”

Popular Culture and the Church

Illusions of Freedom: Thomas Merton and Jacques Ellul on Propaganda by Jeffrey Shaw

Jacques Ellul On Freedom, Love, and Power

Advert: International Jacques Ellul Society

Issue #48 Fall 2011 — Anarchism and Jacques Ellul

Information on The Editorial Board & More

Yahweh is Still King: Engaging 1 Samuel 8 and Jacques Ellul by Thomas Bridges

Introduction: Ellul’s Anti-Monarchic Deuteronomist

1 Samuel 8: The Crisis of Yahweh’s Kingship

Some Further Issues with Kingship in the Deuteronomistic History

”Come Out, My People!“ Rethinking the Bible’s Ambivalence About Civilization

Just Policing: An Ellulian Critique

Christian Anarchism: A Political Commentary on the Gospel

International Jacques Ellul Society

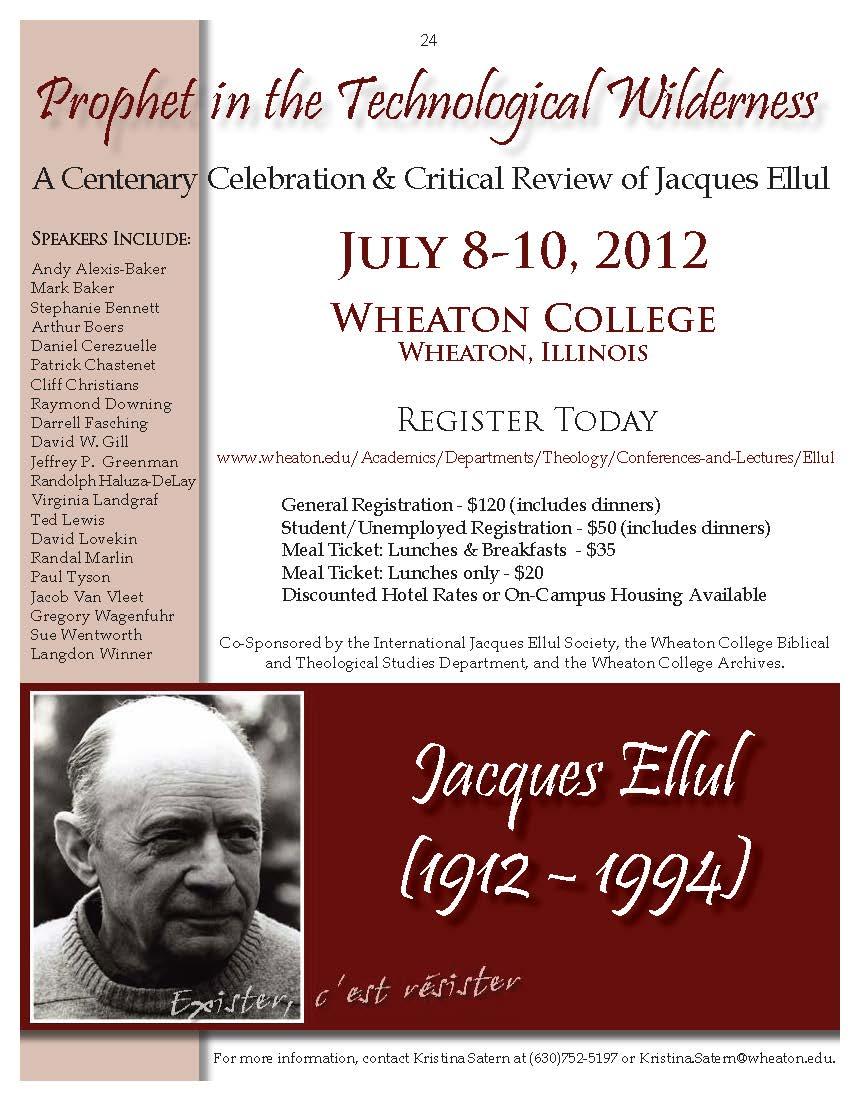

Prophet in the Technological Wilderness

Issue #49 Spring 2012 — Art, Technique, and Meaning in Jacques Ellul

Information on The Editorial Board & More

Looking and Seeing: The Play of Image and Art

The Reproducibility of Art; the Art of Reproducibility

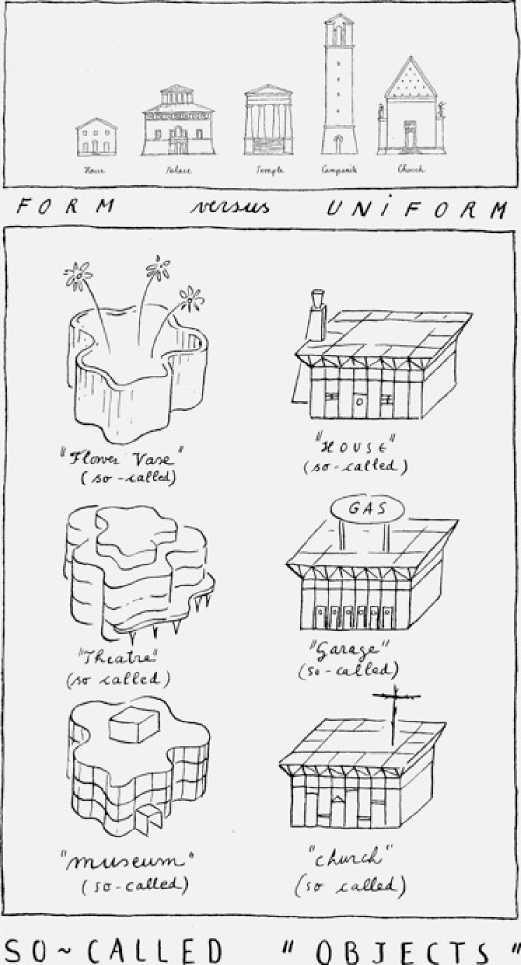

Technique and the Collapse of Symbolic Thought

Our War on Ourselves: Rethinking Science, Technology, and Economic Growth

International Jacques Ellul Society

Prophet in the Technological Wilderness

Information on The Editorial Board & More

Ellul Challenges & Illuminates

My Encounters with Jacques Ellul

From Jacques Ellul to Global Ethics

Ellul as a Model of Christian Scholarship

Connecting With Ellul: An Episodic Engagement

Our Civilization’s Wager on Technique

Advert: International Jacques Ellul Society

IJES Ellul Forum Transition Time

The Sense of Incarnation in Ellul and Charbonneau

II. Technique and Incarnation in Jacques Ellul.

III. Freedom and Incarnation in Bernard Charbonneau

The Problem of Health Care as Technique

The Problem of Risk as Technique

Generations Ellul: Soixante heritiers de la pensee de Jacques Ellul by Frederic Rognon

Generations Ellul: Soixante heritiers de la pensee de Jacques Ellul by Frederic Rognon

Technology and the Further Humiliation of the Word

The Enduring Importance of Jacques Ellul for Business Ethics

On the Lookout for the Unexpected: Ellul as Combative Contemplative by Sue Fisher Wentworth

The Lure of Technic in Current “Leadership” Fascinations

Theology and Economics: The Hermeneutical Case of Calvin Today by Roelf Haan

Jacques Ellul: L’esperance d’abord

21st Century Propaganda: Thoughts from an Ellulian Perspective

The Sacred, the Secular and the Holy:

Silences: Jacques Ellul’s Lost Book

Theologie et Technique: Pour une ethique de la non-puissance

An Unjust God? A Christian Theology of Israel in Light of Romans 9–11

Sham Universe: Field Notes on the Disappearance of Reality in a World of Hallucinations by Doug Hill

Notes on Recent Books by and about Jacques Ellul

On Terrorism, Violence, and War: Looking Back at 9/11 and Its Aftermath

The Prophet of Cuernavaca: Ivan Illich and the Crisis of the West

Ellul, Machiavelli and Autonomous Technique

Digital Vertigo: How Today’s Online Social Revolution Is Dividing, Diminishing, and Disorienting Us

On Terrorism, Violence and War: Looking Back at 9/11 and its Aftermath

Symbols of Power and the Power of Symbols

On the Symbol in the Technical Environment: Some Reflections

Security, Technology and Global Politics: Thinking With Virilio

Dialectical Theology and Jacques Ellul: An Introductory Exposition

Will the Gospel Survive? Proclamation and Faith in the Technical Milieu

“Bringing Ellul to the City Council: A Council Member Reflects on How Ellul Has Guided His Work”

The Empire of Non-Sense: Art in the Technological Society

Liberalism and the State in French and Canadian Technocritical Discourses

Illusions of Freedom: Thomas Merton and Jacques Ellul on Technology and the Human Condition

Biblical Positions on Medicine

Positions bibliques sur la medecine

“Biblical Positions on Medicine” in Theological Perspective

JACQUES ELLUL AND S0REN KIERKEGAARD

THE SICKNESS UNTO DEATH: AVOIDING MISUNDERSTANDINGS

THE SICKNESS UNTO DEATH: FROM DESPAIR TO HOPE

BIBLICAL POSITIONS ON MEDICINE: TOWARD A SPIRITUAL APPROACH TO ILLNESS

“Positions bibliques sur la medecine”: Mise en perspective theologique

JACQUES ELLUL ET S0REN KIERKEGAARD

LA MALADIE A LA MORT: DISSIPATION DE MALENTENDUS

LA MALADIE A LA MORT: DU DESESPOIR A L’ESPERANCE

POSITIONS BIBLIQUES SUR LA MEDECINE: VERS UNE APPROCHE SPIRITUELLE DE LA MALADIE

Sin as Addiction in Our “Brave New World”

Review of Andre Vitalis, The Uncertain Digital Revolution (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2016), 118pp.

Social Propaganda and Trademarks

Jacques Ellul on Violence, Resistance, and War

Information on The Editorial Board & More

Jacques Ellul as a Reader of Scripture

Ellul on Scripture and Idolatry

Advert: IJES E-mail & Payment Info

Judging Ellul’s Jonah by Victor Shepherd

In Review: Tresmontant, Vahanian, Mailot, & Chouraqui

Claude Tresmontant, The Hebrew Christ: Language in the Age of the Gospels

Gabriel Vahanian, Anonymous God (Aurora, Colorado: The Davies Group, 2001)

Advert: International Jacques Ellul Society

A Review of Les Dix Commandments Aujourd’hui & Le Decalogue

Jacques Ellul’s Apocalypse in Poetry and Exegesis

Ellul’s City in Scripture and Poetry

The “Analogy of Faith”: What Does It Mean? Why, and What For?

The Core Principles of the Ellulian Approach to the Bible

Examples of Applying the Method of the Analogy of Faith

The Parable of the Wedding Party

« L’analogie de la foi »: qu’est-ce que cela signifie? Pourquoi et en vue de quoi?

Les grands principes de l’approche ellulienne de la Bible

Exemples d’application de la methode d’analogie de la foi

Jacques Ellul: From Technique to the Technological System

Cerezuelle, Daniel. “Jacques Ellul: From Technique to the Technological System.”

Ellul’s Relationship to Ecclesiastes

The Present Time in Ellul’s Theology

Reading Qohelet through Kierkegaard

Re-Reading Kierkegaard through Qohelet

Efficiency and Availability: Jacques Ellul and Albert Borgmann on the Nature of Technology

The Consequences of Technology

The Response to the Technological Situation

Celui dans lequel je mets tout mon cœur

The One in Which I Put All My Heart

Political Illusion and Reality edited by David W. Gill and David Lovekin

Our Battle for the Human Spirit by Willem H. Vanderburg

The Burnout Society by Byung-Chul Han

About the International Jacques Ellul Society

Nature and Scripture in Bernard Charbonneau’s The Green Light

Carl Amery’s Ecological Challenge to Christianity: Contrasting Responses of Ellul and Charbonneau

Charbonneau’s Ambivalent Reading of Christian Scripture

Disentangling Christianity and Progress

Jacques Ellul and Exodus: A Summary and Review

The Centrality of Exodus in Scripture

Exodus as the Location of Christian Life

Exodus and Freedom as Not Happiness

The Exodus Temptation of Jesus and the Self-Limitation of Freedom

Evaluation of the Exodus Theme in Ellul

Le plus dur des devoirs : La liberté chez Bernard Charbonneau et Jacques Ellul

Une valeur commune : la liberté

Il n’y a de liberté que par l’acte de l’individu

Echapper à l’angoisse de la liberté

La tension entre puissance et liberté

Esprit de puissance ou esprit de liberté?

The Hardest Duty: Freedom in the Thought of Bernard Charbonneau and Jacques Ellul

There Is No Freedom but through an Individual’s Act

The Tension between Power and Freedom

Spirit of Power or Spirit of Freedom?

Anarchie et christianisme par Jacques Ellul

Kierkegaard’s Theological Sociology by Paul Tyson

The Green Light by Bernard Charbonneau

About the International Jacques Ellul Society

A Honduran Mayor’s Experience of Ellul’s Political Illusion

Jacques Ellul, Ivan Illich—and Jean Robert

Issue #1 Fall 1988 — Debut Issue

The

Ellul Studies

Bulletin

A Forum for Scholarship on Theology and Technology

Department of Religious Studies,

University of South Florida, Tampa, Fl 33620

Contents

Call For Manuscripts

Paper Exchange

Volunteers Needed

Bibliography

Media Development Devotes Issue to Ellul

Freedom and Universal Salvation: Ellul and Origen

Forthcoming Ellul Publications by Gary Lee

Forum: The Ethical Importance of Universal Salvation by Darrell J. Fasching

A Visit with Jacques Ellul by Marva Dawn

. 2nd Ellul AAR Consultation by Dan Clendenin

Ellul and Propaganda Review

BookRevlew:

Dan Clendenin’s Theological Method in Jacques Ellul by Marva Dawn

The deadline for submissions for the next issue is October 15,1988. See instructions on the last inside page for details.

Welcome

Welcome to the inaugural issue of The Ellul Studies Bulletin. Thanks to the organizational work of Dan Clendenin, Ellul scholars from around the country (and even beyond its borders) met for the first time at the American Academy of Religion convention in Boston last December. At that meeting I indicated that I would be willing to edit a newsletter which could serve as a communications link among us. This letter fulfills that commitment.

Jacques Ellul’s “contribution to contemporary theology is monumental... a comprehensive tour de force.” This conclusion from my book, The Thought of Jacques Ellul (Mellen Press, 1981), has been criticized as perhaps too strong a claim. However I remain unrepentant As the Epilogue (177ff) in which this statement appeared made clear, his work is monumental not because he is right in every respect but because of its unique focus and comprehensiveness. The depth and breadth of his work “culminates in a thorough sociological analysis of the technological society and its religiosity in such a way as to directly lay bare the ethical and theological issues surrounding human freedom and the future in our technological civilization.”

Ellul has helped theologians to see that technology is not just one more thing to think about but rather has replaced “nature” as the new all-encompassing context in which theology is done. “Perhaps the most important contribution of Jacques Ellul to the future agenda of theology is not the answers he offers to the questions he raises (although his answers are not insignificant, he would not think of them assoZuftons) but the questions themselves.” Through his sociological analysis of the sacralization of technology placed in dialectical confrontation with the Biblical witness to the Holy, Ellul has taught us how to raise the question of technology in such a way as to be appropriated for theological reflection and ethical consideration.” He has taught us how to think critically, creatively and constructively about technology in a way no one else has managed to do. Barth may be his equal, indeed his mentor, in theology. Lewis Mumford may approach his status as a sociological and historical critic of technology, but no one has brought these two disciplines (theology and sociology) together in such a way as to define the theological and ethical agenda as Ellul has. “Thus even where Ellul may be thought in error by some, I believe he will be seen as having advanced our understanding of the issues, for his bold formulations provoke further investigation, further dialogue, further insight. He is a man who has done his homework to our benefit.” One may not agree with Ellul but there is no way to responsibly do theology in our technological civilization without taking his work into account. There is no way around him, only through him. That is what makes his work monumental.

It is appropriate therefore that this publication bear Ellul’s name. It is my hope that The Ellul Studies Bulletin will live up to Ellul’s dialectical and dialogical standards. Nothing would be more embarrassing and disappointing to Ellul than to have this Bulletin be the vehicle for true disciples, Ellul groupies, or a cult of Jacques Ellul. The whole thrust of Ellul’s theological ethics has been to force Christians to think for themselves and invent their own responses. Although the Bulletin will review and discuss Ellul’s work, it should not be our purpose to turn Ellul’s scholarship into a body of sacred literature to be endlessly dissected. The appropriate tribute of the Bulletin to Ellul’s work will be to carry forward its spirit, its agenda for the critical analysis of our technological civilization. Ellul invites us to think new thoughts and enact new deeds. The Bulletin should be a vehicle for carrying out that challenge, hence the tag line of the Bulletin, “A Forum for Scholarship on Theology and Technology”

I debated about what to call this publication. At first I thought perhaps The Ellul Studies Newsletter. But I wanted it to be something more than a newsletter and yet something less than a journal. I hope the Bulletin will create such a niche for itself. It should be a vehicle for the exchange of information on conferences, publications, etc. But I also hope that it will be a forum for the exchange of ideas. I would like to invite you to submit short position papers (up to ten double spaced pages) for open discussion. Responses would be invited and printed in the next issue. Sometimes when weare working on ideas but are not quite ready to put them in final form it would be helpfill to be able to send up a trial balloon and see how it flies. The Forum, I hope, will serve that purpose.

The Ellul Studies Bulletin will be published twice a year in late Spring and again in late Ball (about a month before the AAR meeting). This first issue is free and I encourage you to duplicate it and send it to interested friends or send me their addresses and I will put them on the mailing list. If you decide you wish to receive the Bulletin you will need to fill out the subscription form on the last page of this issue and mail it in with your check. Within the United States subscriptions are $4.00 per year. Outside the U.S. subscriptions are $6.00. These rates will have to be reviewed after our first year of operation but I want to keep the cost as low as possible.

Finally, this is an experimental publication. If it is to work everyone who subscribes needs to participate by sending position papers for the Forum, annotated bibliographic information on books or articles you have published, reviews of relevant books you have read, announcements of conferences and calls for papers on relevant topics, etc. The Bulletin should function as a communications network. If you don’t send me submissions it is an indication that there is no need for the network. So let the experiment begin.

Darrell J. Fasching, Editor

Nota Bene

The deadline for submissions for the next issue is October 15, 1988. See instructions on the last inside page for details.

Call for Manuscripts

Peter Lang Publishing (New York/Bem) is searching for bold and creative manuscripts for their new monograph series on Religion, Ethics and Social Policy edited by Darrell Fasching. Scholars from the Humanities and Social Sciences are invited to submit book-length manuscripts which deal with the shaping of social policy in a religiously and culturally pluralistic world. We are especially interested in creative approaches to the problems of ethical and cultural relativism in a world divided by ideological conflicts. Manuscripts which utilize the work of Jacques Ellul would be most welcome as well as manuscripts taking other approaches. A two page brief on the series is available. For more information, or to submit a manuscript, contact the series editor, Darrell J. Fasching, Cooper Hall 317, University of South Florida, Thmpa, Florida 33620. Phone (813) 974–2221 or residence (813) 963–2968.

Fasching is also Associate Editor for U.S.E Monographs in Religion and Public Policy which accepts manuscripts on religion and public policy which are too long for journals but too short for a book. If you care to submit a manuscript in that category you may also send that to the above address. Be sure to indicate the monograph series to which you wish to submit your manuscript.

Paper Exchange

One service the Bulletin might be able to perform is providing a bulletin board for the exchange of papers delivered at academic conferences. If you have papers you have delivered on Ellul or on the general topic of theology and technology and are willing to make them available, send the title with a brief annotation and your name and address, and indicate whether there is a fee per copy. These will be listed on the bulletin board and anyone interested can write you for a copy.

Volunteers Needed

If you would be interested in assisting in the production of the Ellul Studies Bulletin please contact Darrell Fasching, CPR 317, University of Soutrh Florida, Tampa, Fl 33620. Undoubtedly we will need a book review editor, a bibliographic editor, etc. It is essential that you have access to a computer to prepare copy.

2nd Ellul Consultation Scheduled for November AAR

by Dan Clendenin

ThcAmerican Academy of Religion will sponsor the second Consultation on Jacques Ellul at its annual meeting in Chicago this November.

Last year’s meeting attracted over 40 participants. Three papers were presented.

Marva J. Dawn, The Importance of the Concept of the “Powers” in Jacques Ellul’s Work

Darrell J. Fasching, The Dialectic of Apocalypse and Utopia in the Theological Ethics of Jacques Ellul

David Lovekin, Jacques Ellul and his Dialectical Understanding

The respondents for the first session were: David W. Gill, Joyce Main Hanks and Charles Mabee.

This year we will have three papers and a single respondent for our 2 1/2 hour session:

Clifford G. Christians: Ellul’s Sociology

Joyce M. Hanks, The Kingdom in Ellul’s Thought

David W. Gill The Dialectical Relationship Between Ellul’s Theology and Sociology

Gary Lee, Respondent

For those interested, the pertinent information for the second consultation is as follows:

AAR Annual Meeting

November 19–22,1988

Chicago Hilton and “towers

Chicago

For further information, you can contact the chairperson of the consultation:

Daniel B. Clendenin

William Tyndale College 35700 West 12 Mile Rd.

Farmington Hills, MI 48018

313-553-7200/9516

Book Reviews

Theological Method in Jacques Ellul

by Daniel B. Clendenin (Lan-hanm, MD: University Press of America, 1987). pp. xvii + 145

Reviewed by Marva Dawn, Vancouver, Washington

(Marva is a Ph.D candidate in Christian Ethics at the University of Notre Dame and a founder of Christians Equipped for Ministry in Vancouver.)

Dan Clendenin’s well-researched and balanced study develops the thesis that “Ellul’s theological method revolves around one key theme or kernel idea, the dialectical interplay between freedom and necessity,.. a gold thread ... which serves as a sort of hermeneutical key to his thinking” (xi). This revised doctoral dissertation contributes immensely to the possibility that more scholars and lay readers can properly understand Jacques Ellul and let his thinking stimulate, rather than alienate, their own. Since most of us reading this publication believe that Ellul’s prophetic voice needs to be heard in our world, we can all be grateful that Dan Clendenin has provided such a useful tool for listening to him appropriately.

Clendenin’s own method is illustrated best by three concentric circles, the largest of which describes four methodological interpretations of Ellul: as theological positivist, existentialist, prophet, and dialectician. His second chapter analyzes the more narrow circle of Ellul’s dialectical method, which “operates as a description of reality [the phenomenological], an epistemological orientation to understand this reality, and as a Biblical-theological framework by which to read the Bible and craft a peculiarly Christian style of life [existential]” (xvi). Then, chapters three and four explicate Ellul’s central dialectic between freedom and necessity, the innermost circle and the “controlling idea in all of Ellul’s work” (59).

The final chapter analyzes four weaknesses and three strengths of Ellul’s method. Clendenin’s “internal” criticisms are the best part of the book, for he aptly demonstrates that Ellul’s works contain definite non-dialectical tendencies which are inconsistent with his avowed method (129). First of all, Ellul’s unclear or caustic use of language often invites antagonism rather than dialogue. Secondly, his theme that freedom is not just a virtue of the Christian life, but rather its sine qua non, is undeniably reductionistic. Ellul is right to emphasize this aspect because of the social circumstances of contemporary Christianity, but his overstatement denies the dialectical interplay of other factors in discipleship. Most helpful of Clendenin’s critiques is his analysis of the inconsistency of Ellul’s universalism in its selective reading of Biblical texts, its negation of human free will, and its negation of the individual (pp 135–141).

I disagree, however, with Qendenin’s third alleged weakness in Ellul’s; method — viz., his conception of “power as the enemy of God.” Utilizing die Biblical notion of exousiai, Ellul has maintained a dialectical tension in his understanding of power, though his latest work, The Subversion of Christianity, contradicts some of his earlier statements about the nature of “the Powers.” Furthermore, Clendenin himself must be criticized for his own overstatement that “Ellul never comes close to incorporating the use of power into his dialectic” [134, emphasis mine), and he himself is inconsistent when he asks Ellul to give “clear guidelines” for “nonpower use,” since a few pages later he cites as a first strength in Ellul’s method his deliberate refusal to provide solutions in order to obligate readers to think beyond him (133 and 142). His claim that Ellul “gives us no help here with his rather unrealistic picture” (133) overlooks the prophetic nature of Ellul’s language, designed to raise awareness of the subtlety of the demonic aspects of power.

Clendenin also cites as strengths that Ellul effectively combines theology from above (revelation) and below (practical concern for the world) and that his theology truly offers hope and freedom to the person on the street. That, of course, is a main reason why all of us care so much about his work.

Freeom and Universal Salvation: Ellul and Origen

In some ways no two theologians in the history of Christianity could be farther apart than Jacques Ellul and Origen, the Neo-Platonic theologian from the 3rd century. If one were to classify them using H. Richard Niebuhr’s five types of Christ and culture relationships, Origen would probably fall under the Christ of Culture type and Ellul would stand probably be found somewhere between Christ Against Culture and Christ and Culture in Paradox. In many ways Tfertul-lian rather than Origen would seem to be the theologian who might have the most in common with Ellul. And yet on two themes very much at the heart of Ellul’s thought, freedom and universal salvation, it is in fact Origen who is his kindred spirit. Although its hard to believe, Origen is even more radical on these two themes. On universal salvation it seems that he held that all creatures would eventually be saved, even the devil, and on freedom he thought that because God gave us the capacity to be free, even after universal salvation is achieved, the fall could happen again, should some creature choose to rebel against God. Ellul would not go quite that far on either count but he certainly goes further than most theologians in the Christian tradition have. In the Forum column for this issue a case is made for the ethical importance of universal salvation. But to refresh our minds on Ellul’s stand the following excerpt from Dan Clendenin’s recent interview with Ellul is quoted from Media Development (2/1988, p. 29).

Interview

Clendenin: You have been a strong advocate of universal salvation, which you seem to support by at least five ideas: distinction between judgment-condemnation; between salvationfreedom; priority and triumph of God’s love (Jonah’s hard lesson); your robust/high Christology; scriptural references to perdition — ‘God’s pedagogy* — only of heuristic value.

Ellul: Exactly. This is a part of Karl Barth. Barth liked very much to make a joke. One day he explained the difference between a Christian and a non-Christian in this way: everyone has received a sealed letter from God, but a Christian is the one who has opened it and read it. That’s the way it is in reality. Every person is loved by God, but Christians are the only ones who know it

Clendenin: And experience the joy, hope and freedom.

Ellul: Yes, and that changes completely one’s perspective on mission. Because toward pagan people, for example, we do not say to them, ‘Be converted or, you will be damned’, but rather, ‘I’m telling you that you are loved by God.’

Clendenin: That was Jonah’s hard lesson, that God loved even the Ninevites! No one is excluded.

Ellul: Yes.

Clendenin: You said with Karl Barth that a person must be crazy to teach universalism, but impious not to believe it.

Ellul: Yes, I like very much this phrase of Barth’s. For me, obviously, there are biblical texts which seem to go against the idea of universalism, but I really don’t understand them very well. That’s why I say very often that for me universal salvation is in the realm of faith, but I cannot present it as a dogma.

Clendenin: Would it be fair to call your belief in universal salvation a pious hope but not an absolute conviction?

Ellul: No, it’s an absolute conviction.

Clendenin: Universal salvation sounds very un-Kierkegaardian!

Ellul: Yes, this is exactly the place where I part company from Kierkegaard.

Clendenin: But what about his question: does this do away with Christianity by making everyone a Christian?

Ellul: No, it does not make everyone Christian.

Clendenin: They are not hidden Christians?

Ellul: No, that’s right, to teach people that they are loved by God is to start them on the path of being converted to Jesus Christ. But it’s not at all what Kierkegaard justly criticized as a ‘Christian’ society.

Clendenin: Yes, this latter theme you pick up in The Subversion of Christianity. What about divine coercion in universal salvation, especially given your very strong emphasis on the absolute importance of human decisions/choices.

Ellul: This is really a story of love between God and man. I don’t believe that the human being is completely independent before God.

Clendenin: And here we’ve begun to ask the metaphysical question which we can never answer.

Ellul: When the Word of God addresses a person it liberates him or her, but this free person has heard a word from God. Often I ask my students and the people to whom I’m preaching, ‘Do you understand that what you’re hearing right now is a word from God?’ Thus there is human responsibility, and one can never say that God does not speak. Yes, He does speak now.

Bibliography

Each issue the Bulletin will print bibliographical references to articles and books either on Ellul or using Ellul’s work as well as other publications of interest in the area of theology and technology. If you have written such books or articles, please submit the bibliographic information preferably with a sentence or two of annotation. You may also submit articles written by others which you believe your colleagues should know about A few articles by Dan Clendenin and Darrell Fhsching are listed below to start things off.

Clendenin, Daniel.

Theological Method in Jacques Ellul. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1987.

”Will the Real Ellul Please Stand Up? A Bibliographic Survey,” The Dinity Journal 6.2 (Autumn 1985): 176–183.

”The View from Bordeaux: An Interview with Jacques Ellul,” Media Development 2/1988.

Fasching, Darrell J.

The Thought of Jacques Ellul. New York and Toronto: Edwin Mellen Press, 1981.

A comprehensive analysis of Ellul’s sociology and theological ethics. (225pp.)

Technology as Utopian Technique of the Human,” Soundings, Vol. LXII, #2, Summer 1980.

Utilizes Ellul’s work in a broader thesis about the utopian and anti-utopian elements in modern technology.

”Jacques Ellul as a Theologian of Culture”, Cross Currents, xxxv #1, Spring 1985.

Interprets Ellul’s work in the light of Tillich’s idea of theology of culture with a focus on Ellul’s books The New Demons and Apocalypse.

”Theology and Public Policy: Reflections on Method in the Work of Juan Luis Segundo, Jacques Ellul and Robert Doran,” Method, Vol. 5, #1, March, 1987.

An critical comparative analysis of the role theologicaljsociological method in the critique of ideology as an element in the shaping of public policy.

”The Dialectic of Apocalypse and Utopia in the Theological Ethics of Jacques Ellul” in Research in Philosophy and Technology Greenwich: JAI Press, 1988.

An attempt to show that Ellul’s dialectic leads to a more positive evaluation of utopianism than he explicitly allows. The complexity of Ellul’s dialectic is unraveled using H. Richard Niebuhr’s typology of “Christ and Culture.”

”Mass Media, Ethical Paradox and Democratic Freedom: Jacques Ellul’s Ethic of the Word,” in Research in Philosophy and Technology. Greenwich: JAI Press, 1989

An attempt to suggest an ethic for Journalists based on Ellul’s analysis of media and propaganda which relates Ellul’s work to the work of Eric Voegelin and the ethics of Martin Luther as well as the Anabaptist tradition.

”The Liberating Paradox of the Word,” in Media Development 2/1988.

Relates Ellul’s work on media and propaganda and especially his The Humiliation of the Word to the implicit concern the professional fields of communication (especially journalism) have with theology and the explicit concern theology has with communications.

Forum

The Ethical Importance of Universal Salvation

by

Darrell J. Fasching, University of South Florida

The purpose of the Forum is to provoke discussion, to further that goal, let me state the thesis of this position paper bluntly. In Dan Qendenin’s book, Theological Method in Jacques Ellul, (University Press of America, 1987), he offers as one of his most devastating critiques of Ellul the following: “The most glaring inconsistency in Ellul’s theological dialectic is bis nearly unqualified affirmation of die universal salvation of all peoples beyond history.” (Clendenin, 135) According to Clendenin this dissolves the dialectical tension that Ellul otherwise maintains throughout his theology, the tension between No and Yes, between the Judgment and Promise of God. Moreover he argues that by insisting on universal salvation Ellul in fact commits the sin of collectivization (treating humanity as a mass) which he otherwise condemns in his dialectical critique of the technological society. My thesis is quite simple — Dan Clendenin is wrong. (1) Ellul’s affirmation of universal salvation has not broken the consistency of his Biblical and Barthian dialectic nor has it succumbed to collectivization. On the contrary (2) the notion of universal salvation is a necessary pre-condition for the ethic of freedom Ellul develops precisely to protest the collectivization of human behavior in a technological society Finally (3) Clendenin’s failure to understand this linkage between ethical freedom and universal salvation is complemented by his failure to understand the relationship of both to power. This leads to another questionable criticism central to his final critique of Ellul, namely that Ellul allows no positive place for the use of power within a Christian ethic.

(1) First, let’s be clear, Ellul is not professing some general philosophical dialectic. He explicitly states that he is affirming the Biblical dialectic of judgment and promise. This biblical dialectic is eschatological. That is, the Biblical literature itself, whether the prophets of the Old Testament or the Gospels of the New Testament, limits this dialectic to history. Clendenin wants Ellul to be “consistent” and carry this dialectic “beyond history.” But that is precisely what would be inconsistent. Clendenin suggests that one strategy that Ellul could take in response to his criticism would be to “be explicit about what he implicitly affirms, that his concept of dialectic is limited to history, and that there is no reason for this dialectic to continue after this life. I have found only one place where he hints at such (The Humiliation of the Word, 269).” Clendenin acts as if this were a matter for speculation on which he is inviting Ellul to take a stand and is puzzled that he cannot find explicit references by Ellul to the issue. I submit that this is not hard to understand. Since Ellul explicitly subscribes to the Biblical dialectic which is limited to history I doubt that he ever thought that the matter needed further comment. Ellul remains consistently faithful to the Biblical dialectic.

(2) Second, Ellul’s insistence on universal salvation (a) is not an instance of the collectivization which he otherwise criticizes in a technological society but rather (b) is a precondition for an ethicof freedom which is able to combat such collectivization.

Let me address point (2a) first. For Ellul collectivization is a sin which has to do with the limits of human consciousness. Human beings, he argues, (in False Presence of the Kingdom for instance) are not capable of loving the whole human race. Individuals can only love individuals, the neighbor who crosses one’s path and is in need. Mass media seduce us into trying to love everyone. The media evoke compassion in us for those in distress half way around the world who we can only know abstractly and collectively. In the process we become diverted from caring for the neighbor we can personally know and help. Intent on changing the world, we become swept up in mass movements and bureaucratic structures which rob us of our individuality while at the same time we end up neglecting our neighbor. Such collectivization is a function of our being limited finite beings. As such we can neither know nor relate to all individuals personally and individually. Universal salvation on the other hand has nothing to do with this human limitation. Universal salvation is about God’s capacity, not our human capacity. Unlike ourselves, God’s knowing and caring are not limited. Only God could conceivably know, love and save the whole human race and do so without collectivization. Only God could love the whole human race by loving each individual as an individual. Therefore Clendenin is quite wrong to say that universal salvation is inconsistent with Ellul’s dialectical critique of collectivization.

Now let me turn to point (2b). In fact, the case is quite the contrary of the one Clendenin suggests. Universal salvation actually plays a central role in making possible Ellul’s ethic of freedom and its protest against collectivization by undermining the theological rational which has historically promoted Christianity as a collectivizing religion, one which produces an ethic of conformity to the world. Th make my case I wish to appeal to arguments advanced not by Ellul himself, although I believe they are presupposed in his work, but by two of his theological contemporaries, John Howard Yoder and Juan Luis Segundo. These are an unlikely pair of names to link together. Yoder champions the Anabaptist tradition while Segundo is an advocate of liberation theology. But on one issue both agree, namely that as soon as Christianity came to view its message as something everyone must accept in order to be saved, Christianity began to be “watered down” and abandoned its “ethic of discipleship” for a Constantinian ethic of “Christian civilization.” [see chapter 8 in Segundo’s The Liberation of Theology, (Orbis Books, 1976) and chapter 7 in Yoder’s The Priestly Kingdom, (University of Notre Dame Press, 1984)].

Both argue that the sociological pressure of preaching a Christianity for everyone leads to the compromising of the Gospel ethicand ends up legitimating a “Christian civilization” whose final outcome is the Inquisition. Both argue that the core of this betrayal of the Gospel lies in assuming everyone has to be Christian in order to be saved. At this point Segundo makes the same move that Ellul does. That is, he appeals to Barth’s teaching on universal salvation. Only in this way, he argues, can the drive toward collectivization be broken in Christianity and its function as a minority Teaven” within society be recovered. Yoder is more suggestive and less explicit bu t he too insists that we have to get rid of the notion that everyone needs to be Christian, and implies that the separateness of Christians has as its goal the “whole world’s salvation” (12). Both of these theologian’s share Ellul’s conviction that Christians are and should be a minority in the world and that the desire to be otherwise leads to the “betrayal of Christianity”. All three are intent upon recovering an important element of prophetic faith, namely, the insistence that election isa call to vocation (i.e., being a light to the nations) and not to a status of special privilege. To put it in New Testament terms, conversion as a response to the call or election to faith is not a privileged guarantee of salvation but rather a call to be a leaven for the transformation of the world into a new creation. When Jesus tells his disciples that they are to be the “salt of the earth” the metaphor is quite deliberate. Who in his right mind would sit down to a meal of salt On the other hand a little salt brings out the true flavor, the best flavor of any plate of food.

Those who admire Ellul’s prophetic ethical critique of our technological civilization but who would choose to deny his position on universal salvation need to ask themselves whether these two can really be separated. As Yoder and Segundo argue, the weight of Christian history suggests otherwise. For Ellul faith is a call to vocation. It is what some are called to do for God’s world in history. Salvation on the other hand is what God has done for the whole human race in Christ The good news of the latter frees Christians to assume the task of the former. Ruth is not a work that earns one a ticket to “heaven”. But faith does make a difference, precisely where it should — in history as the freedom to struggle against the demonic forces of necessity, of collectivization and dehumanization. Rith inserts the freedom of God into history to the benefit of the rest of the world.

Clendenin’s presuppositions become clear when he accuses Ellul of making everyone into a Christian as a consequence of universal salvation (at the very least he seems to think Ellul must believe them to be “hidden Christians”). Clendenin cannot imagine that anyone can be saved unless he or she is a Christian. This never occurs to Ellul. In Clendenin’s interview Ellul explicitly denies this interpretation. Ellul is not playing games with Clendenin. It is simply that he can conceive of non-Christians being saved. For Ellul “being saved” and “being Christian” are overlapping categories, for Clendenin they are one and the same category.

(3) Let me tum to my final point, Clendenin’s critique of Ellul’s treatment of “power.” That he should criticize Ellul for holding a view of universal salvation and also for not advocating a “positive” use of power is rather telling. At least from the point of view of John Howard Yoder’s theology. For Yoder thinks that it is significant that as soon as Christianity decided everybody had to be Christian it gave up the way of non-violence for the way of power and coercion. Where Christians of the first centuries refused to serve in the military, Constantinian Christians made serving the state into a Christian duty. Where Christian’s of the first centuries practiced the Judaic ethic of welcoming the stranger, Constantinian Christianity made being a stranger, one of another faith, illegal. By force of law, and arms if necessary, being a citizen required being a Christian. Yoder and Ellul understand that if you give power an inch it will take a mile — it will take over the whole world. To give power an inch is to compromise the Gospel as embodied in the Sermon on the Mount.

It is interesting that Segundo recognizes this but argues that not even Jesus could live in the world without compromising this message and so suggests that the Gospel must be compromised and the use of force must be baptized by the Gospel. Ellul does not make that mistake. He too recognizes that no one can live in the world without the use of power but he refuses to baptize it. Power may be necessary but necessity belongs to the realm of sin. To use the Gospel to condone power is to do the devils work. Even the power of a benevolent state rests on power as coercion which will never be used only for just purposes. For Ellul, Christians can hold positions of power but they must never succumb to the illusion that their use of power is blessed by the Gospel — rather they must learn to live with the dialectical tension and paradox of being both saints and sinners at the same time. Clendenin’s critique of Ellul on power is wide of the mark. For Ellul power is used positively when the Christian, like the yachtsman, welcomes the conflicting forces of power or necessity that impinge upon him or her and uses them against each other even as the yachtsman tacks against the wind. The only thing to be feared is the calm, for then he or she can do nothing. For Ellul, there is no freedom without power and necessity but as soon as we bless necessity we tum it into a demonic fatality and the positive becomes negative.

The question of the use of power is the most troubling question that Christian ethidsts face. I continue to wrestle with this issue myself. There is room for positions on the “positive use of power” in the ethical dialogue and I hope we will hear more from Dan Clendenin on this matter. But such positions need to take seriously the challenge of Ellul and Yoder (and we could add Stanley Hauerwas to this camp) who insist that Christians have got to stop thinking of themselves as having to “be in charge.” The motivation to baptize power does not come from within the Gospel but from the outside, namely, from desire of Christians to run the world. This desire is closely tied to the presupposition that the whole world ought to be Christian, indeed must be Christian, in order to be saved. That is a dangerous pattern of reasoning and motivation and one which Ellul undercuts, severing the traditional link of Constantinian Christianity (Catholic and Protestant) between election and salvation. Since all are saved through Christ’s death and resurrection that task is already accomplished. What remains unfinished is the struggle with the demonic dehumanization and collectivization which occurs in history. It is to that struggle that the elect are called. Ellul’s insistence on universal salvation serves to rechannel the energy of Christians in the direction which is most needed in our time, the ethical direction. Rr from capitulating to collectivization in any way, it is rather a most potent force against it.

Clendenin has two other aspects to his argument with Ellul that I have not focused on. One is the charge that universal salvation violates human freedom. But universal salvation does not violate free will. It is not about human freedom at all but about divine freedom. It insists that no matter what humans may do God remains free to accept them in his reconciling love — that his love, like the rain, falls on the just and the unjust alike. Rather than reject those who reject him, he chooses to take the consequences of that rejection upon himself in an act of suffering reconciliation. As Paul puts it, prior to any act of repentance, “while we were still sinners, Christ died for us... when we were God’s enemies, we were reconciled to him by the death of his Son...”.(Romans 5:8&10)

Clendenin puts his objection another way by arguing that the problem with Ellul’s position is that human “actions no longer have ultimate soteriological value.” He is quite right and that is as it should be. The act that has “ultimate soteriological value” is the sacrifice of Christ, an act of grace. On this too Ellul is surely right Human acts are restricted to the plane of penultimate value, the plane of history where they can make a difference.

Finally Clendenin argues that universal salvation cannot be scrip-turally maintained. In this position paper I have not tried to show that universal salvation is true or consistent with scripture. I have simply tried to argue that to remove it from Ellul’s position effectively undermines the potency of the prophetic ethic he is so much admired for. In fact, however, I am largely persuaded by Ellul’s arguments in this area as well.

Clendenin seems to imply that the Biblical dialectic of “judgment and promise” should finally result in a division of the world into the saved and the damned. Such a conclusion however assimilates the “Good News” to the historical and dialectical categories of the sacred and profane. It is the power of the demonic (the diabolos or divider) over that dialectic which creates dualistic division, strife and chaos. But Ellul correctly perceives that that dialectical dualism is relativized by the Biblical (eschatological/apocalyptic) dialectic between the Sacred and the Holy, in which the Holy unites what the sacred once divided. Hence the love of God transcends the categories of the sacred and profane (the saved and the damned) and falls upon the just and the unjust alike.

Clendenin also accuses Ellul of a “selective reading of the Biblical texts” but this surely begs the question, since the opposing view selectively reads the Biblical text as well, ignoring precisely those elements Ellul would emphasize. But more to the point every theological position selectively reads the text. After all, (as Krister Stendahl and others have shown) “Justification by faith” is not the dominant theme in Paul’s thought and yet Luther made it the criterion by which all other scriptural statements were to be judged and forged it into the pillar of Protestant faith. Until I read Ellul’s brilliant exegesis of the Book of Revelation I remained skeptical that universal salvation could be scripturally maintained. I came away with my mind decisively changed. It seems to me that Ellul does with the Book of Revelation what Luther did with “justification by faith.” Clendenin may disagree with Ellul’s reading of the Biblical texts but I doubt that he can show that his own alternative reading is any less selective. In the end I am inclined to accept the Pauline advice to Timothy, “We have put our trust in the living God and he is the Saviour of the whole human race but particularly of all believers.This is what you are to enforce in your teaching.” (1 Timothy 4:10 )

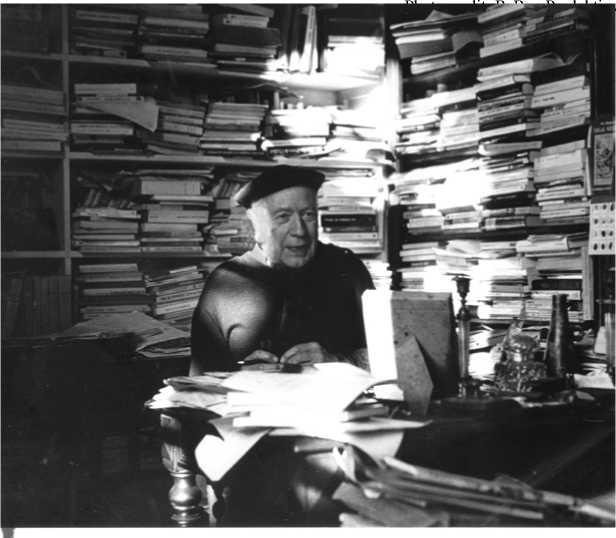

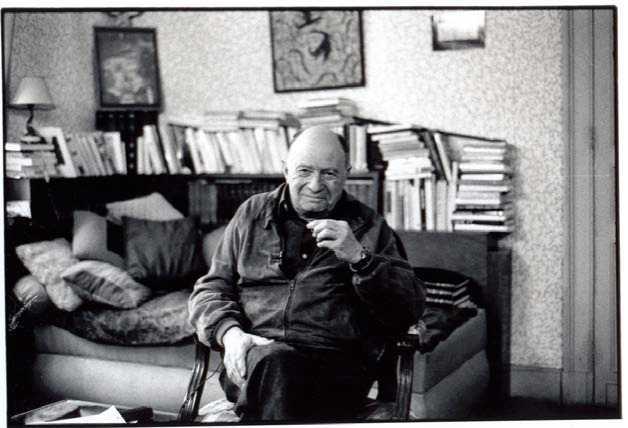

A Visit with Jacques Ellul

Pessac, France, June 27,1987

by Marva Dawn

Jacques Ellul and his wife are very gracious people! They welcomed me kindly and even served raspberries from their garden. Through the excellent translating of Philip Adams, we held a far-ranging conversation for almost two hours. Prof. Ellul asked questions about my work, too — especially about some articles on teaching ethics to children. This stands out in my memory because Ellul serves as an excellent model of a profound scholar who is also able to relate well to other people. Concerning the common split in theologians between the head and the heart he said, “it is contrary to the Gospel.”

We talked about many practical issues that day — the situation in South Africa, the ecology movement, U.S. intervention in Nicaragua, caring for the poor and the handicapped, euthanasia. As would be expected, Ellul stressed the importance of avoiding propaganda and political games, of thinking about each problem as a whole (thinking globally), and of seeing what we can modify practically in our own communities. He urged the U.S. to fight communism with economic justice rather than armies and to help the poor not only materially but also with fellowship, spiritual security and support in their anguish.

Regarding his efforts to reform the Church, Ellul criticized a “whole generation of liberal pastors” who “don’t believe in anything so they have nothing to say.” He said that most of the renewal in France is taking place beside the churches (except for the charismatics), rather than in them. Now he belongs to a small transdenomination-al group trying to listen to laypeople, but this “scares the authorities.” Ellul feels his most important insight for the Church has been his emphasis on hope. Secondly, against the particular French problem of 200,000 people (including many intellectuals) becoming Muslim, he stresses, “our God is a Tfinity.” This led to a discussion of universalism; had

I already read Dan Clendenin’s book (see review) I could have been more able to press him further about the inconsistencies of his views.

The other major doctrinal topic was his concept of “the powers,” the subject of my dissertation. When I questioned certain inconsistencies in his writings, he stressed that the powers must be understood dialectically — that they can’t be personalized, and yet that there is a Power beyond what can be explained, that every human rupture is a diabolos, the Separator.

Most helpful for me were Ellul’s comments about practical issues in writing and teaching, such as creating the necessary balance of preparing for one’s Bible studies while yet dealing with all the people who want to speak with us when we are leading retreats. He stressed the importance of the Holy Spirit in helping us to find the time to do both. When I thanked him for taking the time to talk with me in spite of all he has to do, he answered, “I’m almost done with what I want to write.” Even as The Presence of the Kingdom was the introduction to his corpus, his recently complete commentary on Ecclesiastes is its conclusion. He said that he continues to write, but without a tight program. His Ethics of Holiness is written, but he doubts whether it will ever be published because it is too long — which led to a discussion of presenting our work in publishable ways. He said that he had created his own market, but that it had taken a long time. When I responded that I’m too impatient, he replied, “you must always be impatient.”

I wanted to know Ellul as a person, encountering typical obstacles in the struggle to live out his faith and ministry. He revealed himself as I expected — a wonderful model of a gracious man incarnating the Gospel in practical ways, a brilliant man choosing carefully the values of the kingdom of God.

Media Development Devotes Issue to Ellul

Media Development: Journal of the World Association for Christian Communication has just devoted most of its 2/1988 (vol XXXV) issue to Perspectives on Jacques Ellul. Many of you who are receiving this first issue of Die Ellul Studies Bulletin have also received a copy since I supplied Michael Haber, the editor, with a copy of our mailing list However a number of you who have been added to the list since then will not have received it. You may want towrite fora copy. The address is Media Development, 357 Kennington Lane, London SEII 5QY England (Tblephone 01–582 9139).

The collection of articles is impressive. The table of contents is listed below for your information.

Table of Contents

Editorial: Jacques Ellul — a passion for freedom

Jacques Ellul — a profile

Some thoughts on the responsibility of new communication media

by Jacques Ellul

Is Ellul prophetic by Gifford G. Oiristians

The liberating paradox of the word by Darrell J. Fasching

Understanding progress: cultural poverty in a technological society

by RoelfHaan

Jacques Ellul: a formidable witness for honesty

by John M. Phelan

Feminism in the writings of Jacques Ellul by Joyce Main Hanks

Jacques Ellul-a consistent distinction by Katherine Tomple

Idolatry in a technical society: gaining the world but losing the soul

by Willem H.Vanderburg

An interview with Jacques Ellul by Daniel B. Qendenin

Annotated bibliography by James McDonnell

Forthcoming Ellul Publications

by Gary Lee, Editor, Eerdmans Publishing Co.

It is difficult to keep up with the work of a prolific author like Ellul — he seems towrite more quickly than most of us can read! This difficulty is compounded when the work has to be translated. But it is worth the effort (and the wait, for those who do not read French).

I will begin by just mentioning Eerdmans two most recent translations of Ellul titles: In 1985 we published The Humiliation of the Word (285 pages, $14.95), a translation by Joyce Hanks of La Parole humili^e. In 1986 we published The Subversion of Christianity (224 pages, $9.95), translated by Geoffrey Bromiley from La Subversion du christianisme.