Thomas Carlyle

The French Revolution

A History

Chronological Summary of the French Revolution

Part I : the Bastille (May 10, 1774–October 5, 1789)

Part II: the Constitution (January 1790–August 12, 1792.)

Part III: the Guillotine (August 10, 1792–October 4, 1795.)

Chapter I: Louis the Well-beloved

Chapter IV: Louis the Unforgotten

Chapter II: Petition in Hieroglyphs

Chapter V: Astraea Redux Without Cash

Book III: The Parlement of Paris

Chapter II: Controller Calonne

Chapter V: Loménie’s Thunderbolts

Chapter VIII: Loménie’s Death-Throes

Chapter IX: Burial With Bonfire

Chapter III: Broglie the War-God

Chapter VIII: Conquering Your King

Chapter I: Make the Constitution

Chapter II: The Constituent Assembly

Chapter III: The General Overturn

Book VII: The Insurrection of Women

Chapter II: O Richard, O My King

Chapter II: In the Salle De Manége

Chapter VIII: Solemn League and Covenant

Chapter XI: As in the Age of Gold

Chapter II: Arrears and Aristocrats

Chapter V: Inspector Malseigne

Chapter IV: To Fly or Not to Fly

Chapter V: The Day of Poniards

Chapter VII: Death of Mirabeau

Chapter I: Easter at Saint-Cloud

Chapter VI: Old-Dragoon Drouet

Chapter VII: The Night of Spurs

Chapter V: Kings and Emigrants

Chapter VI: Brigands and Jalès

Chapter VII: Constitution Will Not March

Chapter X: Pétion-National-Pique

Chapter XI: The Hereditary Representative

Chapter XII: Procession of the Black Breeches

Chapter I: Executive That Does Not Act

Chapter III: Some Consolation to Mankind

Chapter VI: The Steeples at Midnight

Chapter VIII: Constitution Burst in Pieces

Chapter I: The Improvised Commune

Chapter IV: September in Paris

Chapter VII: September in Argonne

Chapter V: Stretching of Formulas

Chapter VII: The Three Votings

Chapter VIII: Place De La Révolution

Chapter II: Culottic and Sansculottic

Chapter IV: Fatherland in Danger

Chapter V: Sansculottism Accoutred

Chapter III: Retreat of the Eleven

Chapter VI: Risen Against Tyrants

Book V: Terror the Order of the Day

Chapter IV: Carmagnole Complete

Chapter V: Like a Thunder-Cloud

Chapter I: The Gods Are Athirst

Chapter II: Danton, No Weakness

Chapter VI: To Finish the Terror

Chapter V: Lion Sprawling Its Last

Chapter VII: The Whiff of Grapeshot

[Front Matter]

[Title Page]

Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle was born on December 4, 1795, in Ecclefechan, Scotland, into a strict and pious Calvinist family. After attending Annan Academy (1806–09) and Edinburgh University (1809–14; he left without taking a degree), he began a career as writer and critic, initially working as a translator and reviewer. His first book began as a biographical essay commissioned by London Magazine, evolving into a full-length biography, The Life of Friedrich Schiller (1825).

Carlyle was introduced to London literary circles on a visit in 1824; he later became close friends with J. S. Mill, John Sterling, and many others. With a strong interest in German literature, biography, and history, he began contributing regularly to the Edinburgh Review and other publications. In the early 1830s, Frazier’s magazine published in installments a novel, Sartor Resartus, which, while received harshly at the time, is now regarded by many as a highly innovative masterpiece. In 1834 Carlyle began work on The French Revolution, which would take him three years to complete. The story of its completion is legendary: while left in the care of J. S. Mill, Carlyle’s complete manuscript was mistaken for trash and burned. It was said that Carlyle then rewrote the entire manuscript from memory. The French Revolution was Carlyle’s first broad popular and critical success.

Carlyle’s literary output was prodigious, and his influence upon his contemporaries is hard to overstate; at the height of his powers he was probably the most influential literary figure in Victorian letters. Other major works include On Heroes, Hero-Worship and The Heroic in History, which originated as a series of lectures in 1840; Latter-Day Pamphlets (1850), a work highly critical of democracy, and also unsympathetically received by critics; The Life of John Sterling (1851); and the monumental History of Friedrich II of Prussia, called Frederick the Great (published in six volumes, 1858–65).

Speaking of his influence, George Eliot wrote, “It is an idle question to ask whether his books will be read a century hence; if they were all burnt ... on his funeral pile, it would be only like cutting down an oak after its acorns have sown a forest. For there is hardly a superior and active mind of this generation that has not been modified by Carlyle’s writing.” He died on February 5, 1881, and his reputation thereafter went into a steep decline. In the years since, his writings have continued to suffer neglect, though in recent decades there have been signs of renewed interest. As one recent biographer, Simon Heffer, noted in 1992, “No one from his time cries out for rediscovery and reappraisal as urgently as he does.”

Introduction

John D. Rosenberg

The archetypal Victorian, Thomas Carlyle was born in the same year (1795) as the Romantic Keats. Yet in the course of his long life, England changed radically under the twin pressures of two revolutions, the French and the Industrial. The first inspired Carlyle’s The French Revolution (1837), the second, his great outcry against the barbarism of laissez-faire capitalism, Past and Present (1843). By the end of his long life, England had undergone a political and cultural sea change. In the year before his death in 1882, Oscar Wilde published his Poems and Gilbert and Sullivan’s Patience opened on the London stage. Yeats and Kipling were in print before the end of the 1880s. Long estranged from his earlier radicalism, Carlyle lived out his last solitary decade in a kind of posthumous silence, “a spectre moving in a world of spectres.” The world had changed; Carlyle had not.

Yet in the third quarter of the nineteenth century, Carlyle was the most widely influential voice in the English-speaking world. Those he profoundly touched constitute a roster of eminent Victorians, English and American: the young John Stuart Mill, Ruskin, Dickens, Emerson, Whitman, Melville, Tennyson, Browning, Arnold, Meredith. All in one way or another discovered themselves in discovering Carlyle. Dickens dedicated Hard Times to Carlyle, and across the channel En-gels paid him fervent tribute in a review of Past and Present. George Eliot wrote that for the leading minds of her generation the reading of Carlyle “was an epoch in the history of their minds.” And after the news of Carlyle’s death reached Whitman, he remarked that trying to imagine the larger culture of the past half-century without Carlyle would be like trying to imagine an army with the artillery left out.

Yet today, Carlyle is rarely read by nonspecialists and only occasionally appears on reading lists within the academy. The causes are many, not least of which is that Carlyle is one of the most allusive and innovative of English prose writers, a kind of proto-Joyce in his incessant verbal coinages,[1] conflation of ancient myth and modern actuality, his labyrinthine narrative strategies and gift for impersonation. It is impossible to “speed-read” Carlyle, any more than Milton, whose Paradise Lost figures on virtually every page of The French Revolution, as do Homer and the Bible. If he is now half-forgotten, his is not the case of a once-inflated popular reputation expiring into decent oblivion, but of meteoric genius now in partial eclipse. Nowhere is that genius on more dazzling display than in The French Revolution, at last available to American readers, complete and moderately priced, in the present Modern Library edition.

No creation of Carlyle’s is more striking than his self-creation as a poet-prophet in the years immediately preceding the composition of The French Revolution. In 1826, he married the brilliant Jane Baillie Welsh, who, in choosing Carlyle, made a kind of Faustian bargain, selling not her soul but her happiness by wedding genius in the person of her difficult, dyspeptic, possibly impotent, and self-absorbed husband. In 1828, they moved to virtual seclusion on a farm amidst the desolate Scottish moors at Craigenputtock. For the following six years, Carlyle searched to find his true vocation. He published anonymously a remarkable series of essays surveying the whole of contemporary English culture. Emerson read them in America, recognized a new mind of the first magnitude, and journeyed all the way to Craigenputtock to greet their author. During these years he created one of the strangest, most innovative books in English, the quasi-autobiographical Sartor Resartus (1833–34). In Sartor he became adept at impersonating “many voices,” and, most memorably, he anatomizes the revolution in individual consciousness that results in conversion, as he was soon to explore conversion writ large as revolution across the nation of France. But he had yet to find a subject large enough to contain his ambition as a writer or a style appropriate to his subject. He began to groom himself for the role of latter-day prophet, a kind of ironic John the Baptist in an age that worshipped the machine. “I have some thoughts of beginning to prophecy [ sic] ... that seems the best style, could one strike into it rightly,” he wrote in 1829 to the editor of Blackwood’s Magazine. His new friend John Stuart Mill sent him a library of books on the French Revolution, and in a letter of 1833 acknowledging the gift, Carlyle announces that the “right History” of the Revolution would be the “grand Poem of our Time.... [The] man who could write the truth of that, were worth all other writers and singers.” The French Revolution is just that, one of the grand poems of his century, yet its poetry consists in being everywhere scrupulously rooted in historical fact. But the letter most revealing of Carlyle’s self-consecration as poet-prophet-historian is his first to Emerson: “I am busy constantly studying with my whole might for a Book on the French Revolution. It is part of my creed that the only Poetry is History, could we tell it right.” To tell it right means, first, transcending the linear, time-bound limits of narrative so that, for example, when Carlyle depicts the storming of the Bastille in a roar of voices, his reader also hears the crashing of the towers of Troy and the fall of the walls of Jericho. “Narrative is linear, Action is solid,” Carlyle had written in “On History” (1830). How then can a writer render in lines on a page a world in upheaval in which all events are contiguous with all other events, “prior or contemporaneous,” and events themselves are highly problematic, a world in which everything, as Carlyle delights in pointing out, is “optique,” depends upon the angle of vision of countless beholders? The solution is to create through a montage of words on a page a world of historical actuality in which no event occurs in isolation from any other and all are rendered in their rounded fullness.

I pause a moment longer over the oddity of Carlyle’s use of the word tell. Storytellers tell tales but we expect historiographers to write history. To tell it in Carlyle’s sense implies a concept of history we have virtually lost but that lies at the heart of his vocation—history as utterance, as song or revelation, as in telling a secret, or in the joyous proclamation, “Go, Tell it on the Mountain.” History in this ancient sense is not narration but prophecy. It is not data but speech—the sung speech of a poet.

On at last beginning the book, Carlyle wrote to his brother John that he was composing “quite an epic Poem on the Revolution: an Apotheosis of Sansculottism.”[2] Robert Lowell, it seems, agreed with Carlyle’s description. In a gnomic essay on Homer and Virgil, Dante and Milton, drafted shortly before his death, Lowell wondered if there are any epics in prose: “I know one, Carlyle’s French Revolution.” Carlyle had prepared to write his revolutionary epic with all the awesome deliberateness and self-consecration that Milton brought to the writing of Paradise Lost, Wordsworth to The Prelude, or Joyce to Ulysses.

Magnitude of scale combined with minuteness of realization mark the defining quality that energizes all epic. For epic is not confined to any particular form or literary period. Rather, it embodies the dominant impulse of the literary imagination in any age—from Gilgamesh to Derek Walcott’s Omeros —by which the panoramic and the particular, the cosmic and the local, the mythic and the historic, are held in most fruitful tension. Epic is the great colonizer of all other genres. A prime sign of the burst of literary creativity in the nineteenth century is that the epic impulse manifested itself in so many different genres— primarily in the novel (the “home epic” of Middlemarch, for example)— but also in autobiography (The Prelude), in history (The French Revolution; The Stones of Venice), in Henry Mayhew’s teeming sociological panorama (London Labour and the London Poor), to say nothing of the great American and Continental epics, historical and fictional, of Prescott and Michelet, of Melville, Tolstoy, and Balzac.

With all the skill of a modern documentary journalist, Carlyle writes The French Revolution as if he were a witness-survivor of the Apocalypse. But in the modern world the gods have gone underground, God Himself is in apparent hiding, and the Apocalypse has relocated itself in historical time. Much of the power of The French Revolution lies in the shock of its transpositions, the explosive inter-penetration of modern fact and ancient myth, of journalism and Scripture. And so Carlyle invents a mixed style, a unique “ludicro-terric” idiom that is by turns prophetic and ironic, epic and mock-epic, and that interweaves the language of Homer and the Bible with the abrupt argot of the Parisian barricades.

The hero of Carlyle’s latter-day epic is the demonic Sansculottes: “The ‘destructive wrath’ of Sansculottism: this is what we speak, having unhappily no voice for singing.” Tucked within the modest disclaimer is the traditional boast of the epic poet—Carlyle’s tacit comparison of himself to Homer—and the further suggestion that in a post-heroic age speech (prose) is a more persuasive medium than song (poetry). Hence in The French Revolution Carlyle writes, or rather speaks—for history is at bottom a “telling”—a kind of inspired vernacular poetry that is closer to Homer and Milton than to the prose of Gibbon or Macaulay. John Stuart Mill said as much at the start of his review of The French Revolution, a review perhaps written in partial recompense for his having been inadvertently responsible for the burning of the sole manuscript of Carlyle’s first volume:[3]

This is not so much a history, as an epic poem; and notwithstanding, or even in consequence of this, the truest of histories. It is the history of the French Revolution, and the poetry of it, both in one; and on the whole no work of greater genius, either historical or poetical, has been produced in this country for many years.

Carlyle’s analysis of the causes of the Revolution is starkly simple: “For ourselves ... [the] French Revolution means ... the open violent Rebellion, and Victory, of disimprisoned Anarchy against corrupt worn-out Authority.” Anarchy bursts its prison, rises from the “infinite Deep,” rages, and finally consumes itself in the Reign of Terror. The huge, stalking capitalizations that loom at the reader from Carlyle’s pages—Rebellion, Anarchy, infinite Deep—are the metaphoric equivalent of the Greek Furies or of the Old Testament God who shakes Israel’s oppressors from their thrones. The disimprisoned Anarchy that destroys ancient Authority is both psychological and political; within the psyche, it represents the unleashing of all unconscious drives.[4] In the nation, it is the overturning of ancient Authority by the Sansculottes. Anarchy is enthroned throughout Part III of The French Revolution, “The Guillotine,” a descent into a Dantesque underworld, a “Black precipitous Abyss” presided over by Carlyle’s mock-heroic Satan, the infernal cellar-dweller Marat. Classical Underworld, Christian Hell, and the naked psyche regressed back to Cannibalism—these are the three types under which Carlyle comprehends the Reign of Terror. This incarnate anarchy is always present in man, therefore always immanent in history. In certain epochs (the Ancien Régime) it is pent up; in others, it bursts forth, is disimprisoned, until it devours itself in its own flames. On the single most appalling page of The French Revolution, Carlyle asks an appalling question. He is at the human tannery at Meudon, where the flayed skins of the newly guillotined were reportedly dressed into leather and sold. “At Meudon,” Carlyle writes, citing Montgaillard,

there was a Tannery of Human Skins; such of the Guillotined as seemed worth flaying: of which perfectly good wash-leather was made; for breeches, and other uses. The skin of the men, he remarks, was superior in toughness (consistance) and quality to shamoy; that of the women was good for almost nothing, being so soft in texture!— History looking back over Cannibalism ... will perhaps find no terrestrial Cannibalism of a sort, on the whole, so detestable. It is a manufactured, soft-feeling, quietly elegant sort; a sort perfide! Alas, then, is man’s civilisation only a wrappage, through which the savage nature of him can still burst, infernal as ever?

Much earlier in The French Revolution Carlyle had written that society rests on the primitive political fact “that I can devour Thee.” Imagery of gorging and disgorging is so prevalent as to suggest that, for Carlyle, revolution is the politics of aggression by ingestion. This darkly tragic view of the human condition inevitably makes Carlyle a mocker of the Enlightenment. True to its Enlightenment origins, the Revolution enthroned Reason; but it also unleashed the Furies; it worshipped Liberty, yet institutionalized Terror as an instrument of state policy; it proclaimed Brotherhood, but, in the words of a Gironist orator about to be beheaded, the Revolution, like Saturn, devoured its children. Carlyle found much irony—but no contradiction—in the fact that the Festival of Reason was celebrated on the eve of the worst atrocities of the Revolution, the mass shootings at Lyon and the mass drownings at Nantes. How could the sons of the Enlightenment have fathered such a state? Because they were sons of the Enlightenment, Carlyle grimly replies. Atrocity is the bloody underbelly of the Social Contract, darkness the underside of the Enlightenment, the wages of believing we are creatures of pure reason and benevolence. No, says Carlyle, we have reason and still inhabit the cave; we love our brother, and also flay and eat him. The heraldic emblem of The French Revolution is the Great Beast of the Apocalypse in Sansculottish dress. Primitive, vital, cathartic, he is a beast who destroys and cleanses, who fathers both violence and renewal—a “ludicro-terrific” beast, as all demons must be in the Age of Reason. Hence the narrative of The French Revolution is simultaneously epic and mock-epic, tragic, ironic, comic. The Great Beast of the Revolution can be as comically incongruous as Robespierre, dressed in a kind of Revolutionary drag, presiding over the absurd Feast of Reason; and he can be as tragic as the same Robespierre, mutilated[5] and shrieking, at the foot of the guillotine:

All eyes are on Robespierre’s Tumbril, where he, his jaw bound in dirty linen, with his half-dead Brother and half-dead Henriot, lie shattered; their “seventeen hours” of agony about to end. The Gendarmes point their swords at him, to show the people which is he. A woman springs on the Tumbril; clutching the side of it with one hand, waving the other Sibyl-like; and exclaims: “The death of thee gladdens my very heart, m’enivre de joie”; Robespierre opened his eyes; “Scélérat, go down to Hell, with the curses of all wives and mothers!”—At the foot of the scaffold, they stretched him on the ground till his turn came. Lifted aloft, his eyes again opened; caught the bloody axe. Samson [the Executioner] wrenched the coat off him; wrenched the dirty linen from his jaw: the jaw fell powerless, there burst from him a cry;—hideous to hear and see. Samson, thou canst not be too quick!

The whole gathered power of The French Revolution compresses to a single point in that shriek of Robespierre. The Revolution had begun in words: first, the words of the philosophes, then a buzzing in the streets of Paris that rose to a roar and shattered the Bastille. Robespierre had become the articulate intelligence of revolutionary France, its “Chief Priest and Speaker.” Speech had been fine-tuned into slogan and decree and epigram—“The Revolution, like Saturn, is devouring its own children”; even the phlegmatic Louis XVI arrived at the scaffold prepared to speak his final piece, until Samson cut him short. But in this last act of Carlyle’s drama, death lapses into pure savagery, the Revolution cannibalizes itself, and speech degenerates into an aboriginal scream. The thin skin of civilization—a mere “wrappage” Carlyle had called it at Meudon—is ripped from Robespierre’s jaw, a gesture of gratuitous malice, for the blood-soaked bandage could not have resisted the falling blade. The cries of the self-blinded Oedipus, the howls of Lear, are not more chilling than the shriek of Robespierre.

Carlyle had called the beheading of Robespierre the last act of a “natural Greek drama.” The ancient Greeks followed the performance of their tragedies with a brief, comic satyr play. The short closing book of The French Revolution is Carlyle’s updating of a satyr play. The Sansculottes, formerly depicted as avenging Furies, are transmuted into Dandies, Jeunesse Dorée, gilded youth dancing in the streets with women in Greek costume in celebration of the end of the Reign of Terror. With the French armies everywhere victorious across Europe and Napoleon moving to center stage, having hijacked the Revolution to serve his own imperial ends, Carlyle brings his epic to a close. The old metaphors return, but now stood on their heads. Young women dressed as Minervas and Junos appear at costume balls in sheer tunics that barely conceal their “flesh-coloured drawers.” The new decadence of feigned nudity supplants the old Sansculottism of naked power. But through the flesh-colored drawers peep the human skins at Meudon and the obscenely mutilated body of the Princesse de Lamballe, hacked to pieces some two hundred pages earlier “with indignities, and obscene horrors of moustachio grands-lèvres.” One incident in Carlyle’s satyr play signals the movement from high drama to farce. A band of carousing Jeunesse Dorée in plaited hair tresses drags the remains of the martyred Marat from the Pantheon and dumps them in the cesspool of Montmartre, “grand Cloaca” of Paris and the World: “Shorter godhead had no living man.” This apotheosis-in-reverse nicely illustrates, in advance, Marx’s aphorism on history repeating itself—first as tragedy, then as farce. Carlyle’s great flaming meteor of a book ends not with an apocalyptic bang but with titters of decadent laughter echoing through the freshly gilded salons of Paris.

JOHN D. ROSENBERG is the William Peterfield Trent Professor of English at Columbia University, where he teaches Victorian literature and has chaired the undergraduate program in literature humanities. He is the author of The Darkening Glass: A Portrait of Ruskin’s Genius, The Fall of Camelot: A Study of Tennyson’s “Idylls of the King,” and Carlyle and the Burden of History.

Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881)

A Note on the Author of “The French Revolution”

The legend of Thomas Carlyle as a truculent husband and a misanthropic genius is a persistent historic libel which is gradually being revised to do justice to the qualities of his mind and character. His ghastly experience with the manuscript of The French Revolution was in itself enough to embitter his outlook on life. Having finished the first volume of his work, he entrusted the only copy of the manuscript to J. S. Mill for comment and annotation. By an accident, it was burned. Carlyle thereupon set to work and rewrote the entire history, achieving what he described as a book that came “direct and flamingly from the heart.” The world has since concurred in this estimate of The French Revolution.

Bibliography

Essay on Goethe’s “Faust” (1822) Goethe’s “Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship” (Translation) (1824) The Life of Friedrich Schiller (1825) Sartor Resartus (1833) The French Revolution (1837) Chartism (1839) On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History (1841) Past and Present (1843) Oliver Cromwell’s Letters and Speeches (1845) Latter-day Pamphlets (1850) Life of Sterling (1851) History of Friedrich the Second, Called Frederick the Great (1858–1865) Life of Robert Burns (1859) The Early Kings of Norway (1875) Reminiscences (1881) Letters and Memorials (1883)

Chronological Summary of the French Revolution

[Drawn up by “Philo,” for Edition 1857]

Part I : the Bastille (May 10, 1774–October 5, 1789)

1774.

Louis XV dies, at Versailles, May 10, 1774, of smallpox, after a short illness: Great-grandson of Louis XIV; age then 64; in the 59th year of his nominal “reign.” Retrospect to 1774: sad decay of “Realized Ideals,” secular and sacred. Scenes about Louis XV’s deathbed, Scene of the Noblesse entering, “with a noise like thunder,” to do homage to the New King and Queen. New King, Louis XVI, was his Predecessor’s Grandson; age then near 20,—born August 23, 1754. New Queen was Marie-Antoinette, Daughter (8th daughter, 12th child) of the great Empress Maria-Theresa and her Emperor Francis (originally “Duke of Lorraine,” but with no territory there); her age at this time was under 19 (born November 2, 1755). Louis and she were wedded four years ago (May 16, 1770); but had as yet no children;—none till 1778, when their first was born; a Daughter known long afterwards as Duchess d’Angoulême. Two Sons followed, who were successively called “Dauphin”; but died both, the second in very miserable circumstances, while still in boyhood. Their fourth and last child, a Daughter (1786), lived only 11 months. These two were now King and Queen, piously reckoning themselves “too young to reign.”

December 18, 1773, Tea, a celebrated cargo of it, had been flung out in the harbour of Boston, Massachusetts: June 7, 1775, Battle of Bunker Hill, first of the American War, is fought in the same neighbourhood,— far over seas.

1774‒83.

Change of Administration. Maurepas, a man now 73 years old and of great levity, is appointed Prime-Minister; Vergennes favourably known for his correct habits, for his embassies in Turkey, in Sweden, gets the Department of Foreign Affairs. Old Parlement is reinstated; “Parlement Maupeou,” which had been invented for getting edicts, particularly tax-edicts, “registered,” and made available in law, is dismissed. Turgot, made Controller-General of Finances (“Chancellor of the Exchequer” and something more), August 24, 1774, gives rise to high hopes, being already known as a man of much intelligence speculative and practical, of noble patriotic intentions, and of a probity beyond question.

There are many changes; but one steady fact, of supreme significance, continued Deficit of Revenue,—that is the only History of the Period. Noblesse and Clergy are exempt from direct imposts; no tax that can be devised, on such principle, will yield due ways and means. Meanings of that fact; little surmised by the then populations of France. Turgot aiming at juster principles, cannot: “Corn-trade” (domestic) “made free,” and many improvements and high intentions;— much discontent at Court in consequence; famine-riots withal, and “gallows forty feet high.” Turgot will tax Noblesse and Clergy like the other ranks; tempest of astonishment and indignation in consequence; Turgot dismissed, May 1776. Flat snuff-boxes come out, this summer, under the name of Turgotines, as being “platitudes” (in the notion of a fashionable snuffing public), like the Plans of this Controller. Necker, a Genevese become rich by Banking in Paris, and well seen by the Philosophe party, is appointed Controller in his stead (1776);—and there is continued Deficit of Revenue.

For the rest, Benevolence, Tolerance, Doctrine of universal Love and Charity to good and bad. Scepticism, Philosophism, Sensualism portentous “Electuary,” of sweet taste, into which “Good and Evil,” the distinctions of them lost, have been mashed up. Jean-Jacques, Contrat-Social: universal Millennium, of Liberty, Brotherhood, and whatever is desirable, expected to be rapidly approaching on those terms. Balloons, Horse-races, Anglomania. Continued Deficit of Revenue. Necker’s plans for “filling up the Deficit” are not approved of, and are only partially gone into: Frugality is of slow operation; curtailment of expenses occasions numerous dismissals, numerous discontents at Court: from Noblesse and Clergy, if their privilege of exemption be touched, what is to be hoped?

American-English War (since April 1775); Franklin, and Agents of the Revolted Colonies, at Paris (1776 and afterwards), where their Cause is in high favour. Treaty with Revolted Colonies, February 6, 1778; extensive Official smugglings of supplies to them (in which Beaumarchais is much concerned) for some time before. Departure of French “volunteer” Auxiliaries, under Lafayette, 1778. “Volunteers” these, not sanctioned, only countenanced and furthered, the public clamour being strong that way. War from England, in consequence; Rochambeau to America, with public Auxiliaries, in 1780:—War not notable, except by the siege of Gibraltar, and by the general result arrived at shortly after.

Continued Deficit of Revenue: Necker’s ulterior plans still less approved of; by Noblesse and Clergy, least of all. January 1781, he publishes a Compte Rendu (“Account Rendered,” of himself and them). “Two hundred thousand copies of it sold”;—and is dismissed in the May following. Returns to Switzerland; and there writes New Books, on the same interesting subject or pair of subjects. Maurepas dies, November 21, 1781: the essential “Prime-Minister” is henceforth the Controller-General, if any such could be found; there being an ever-increasing Deficit of Revenue,—a Millennium thought to be just coming on, and evidently no money in its pocket.

Siege of Gibraltar (September 13, to middle of November, 1782): Siege futile on the part of France and Spain; hopeless since that day (September 13) of the red-hot balls. General result arrived at is important: American Independence recognized (Peace of Versailles, January 20, 1783). Lafayette returns in illustrious condition; named Scipio Americanus by some able-editors of the time.

1783‒7.

Ever-increasing Deficit of Revenue. Worse, not better, since Necker’s dismissal. After one or two transient Controllers, who can do nothing, Calonne, a memorable one, is nominated, November, 1783. Who continues, with lavish expenditure raised by loans, contenting all the world by his liberality, “quenching fire by oil thrown on it”; for three years and more. “All the world was holding out its hand, I held out my hat.” Ominous scandalous Affair called the Diamond Necklace (Cardinal de Rohan, Dame de Lamotte, Arch-Quack Cagliostro the principal actors), tragically compromising the Queen’s name who had no vestige of concern with it, becomes public as Criminal-Trial, 1785; penal sentence on the above active parties and others, May 31, 1786: with immense rumour and conjecture from all mankind. Calonne, his borrowing resources being out, convokes the Notables (First Convocation of the Notables) February 22, 1787, to sanction his new Plans of Taxing; who will not hear of him or them: so that he is dismissed, and “exiled,” April 8, 1787. First Convocation of Notables,—who treat not of this thing only, but of all manner of public things, and mention States-General among others,—sat from February 22 to May 25, 1787.

1787.

Cardinal Loménie de Brienne, who had long been ambitious of the post, succeeds Calonne. A man now of sixty, dissolute, worthless;— devises Tax-Edicts, Stamp-tax (Edit du Timbre, July 6, 1787) and others, with “successive loans,” and the like; which the Parlement, greatly to the joy of the Public, will not register. Ominous condition of the Public, all virtually in opposition; Parlements, at Paris and elsewhere, have a cheap method of becoming glorious. Contests of Loménie and Parlement. Beds-of-Justice (first of them, August 6, 1787); Lettres-de-Cachet, and the like methods; general “Exile” of Parlement (August 15, 1787), who return upon conditions, September 20. Increasing ferment of the Public. Loménie helps himself by temporary shifts till he can, privately, get ready for wrestling down the rebellious Parlement.

1788. JANUARY‒SEPTEMBER.

Spring of 1788, grand scheme of dismissing the Parlement altogether, and nominating instead a “Plenary Court (Cour Plénière ),” which shall be obedient in “registering” and in other points. Scheme detected before quite ripe: Parlement in permanent session thereupon; haranguing all night (May 3); applausive idle crowds inundating the Outer Courts; D’Espréménil and Goeslard de Monsabert seized by military in the grey of the morning (May 4), and whirled off to distant places of imprisonment: Parlement itself dismissed to exile. Attempt to govern (that is, to raise supplies) by Royal Edict simply,—“Plenary Court” having expired in the birth. Rebellion of all the Provincial Parlements; idle Public more and more noisily approving and applauding. Destructive Hailstorm, July 13, which was remembered next year. Royal Edict ( August 8), That States-General, often vaguely promised before, shall actually assemble in May next. Proclamation (August 16), That “Treasury Payments be henceforth three-fifths in cash, two-fifths in paper,”—in other words, that the Treasury is fallen insolvent. Loménie thereupon immediately dismissed: with immense explosion of popular rejoicing, more riotous than usual. Necker, favourite of all the world, is immediately ( August 24) recalled from Switzerland to succeed him, and is hailed “Saviour of France.”

1788. NOVEMBER, DECEMBER.

Second Convocation of the Notables (November 6– December 12), by Necker, for the purpose of settling how, in various essential particulars, the States-General shall be held. For instance, Are the Three Estates to meet as one Deliberative Body? Or as Three, or Two? Above all, what is to be the relative force, in deciding, of the Third Estate or Commonalty? Notables, as other less formal Assemblages had done and do, depart without settling any of the points in question; most points remain unsettled,—especially that of the Third Estate and its relative force. Elections begin everywhere January next. Troubles of France seem now to be about becoming Revolution in France. Commencement of the “French Revolution,”—henceforth a phenomenon absorbing all others for mankind,—is commonly dated here.

1789. MAY, JUNE.

Assembling of States-General at Versailles; Procession to the Church of St. Louis there, May 4. Third Estate has the Nation behind it; wishes to be a main element in the business. Hopes, and (led by Mirabeau and other able heads) decides, that it must be the main element of all,—and will continue “inert,” and do nothing, till that come about: namely, till the other Two Estates, Noblesse and Clergy, be joined with it; in which conjunct state it can outvote them, and may become what it wishes. “Inertia,” or the scheme of doing only harangues and adroit formalities, is adopted by it; adroitly persevered in, for seven weeks: much to the hope of France; to the alarm of Necker and the Court.

Court decides to intervene. Hall of Assembly is found shut ( Saturday, June 20); Third-Estate Deputies take Oath, celebrated “Oath of the Tennis-Court,” in that emergency. Emotion of French mankind Monday, June 22, Court does intervene, but with reverse effect: Séance Royale, Royal Speech, giving open intimation of much significance, “If you, Three Estates, cannot agree, I the King will myself achieve the happiness of my People.” Noblesse and Clergy leave the Hall along with King; Third Estate remains pondering this intimation. Enter Supreme-Usher de Brézé, to command departure; Mirabeau’s fulminant words to him: exit De Brézé, fruitless and worse, “amid seas of angry people.” All France on the edge of blazing out: Court recoils; Third Estate, other Two now joining it on order, triumphs, successful in every particular. The States-General are henceforth “National Assembly”; called in Books distinctively “Constituent Assembly”; that is, Assembly met “to make the Constitution,”—perfect Constitution, under which the French People might realize their Millennium.

1789. JUNE, JULY.

Great hope, great excitement, great suspicion. Court terrors and plans: old Maréchal Broglie,—this is the Broglie who was young in the Seven-Years War; son of a Marshal Broglie, and grandson of another, who much filled the newspapers in their time. Gardes Françaises at Paris need to be confined to their quarters; and cannot (June 26). Sunday, July 12, News that Necker is dismissed, and gone homewards overnight: panic terror of Paris, kindling into hot frenzy;—ends in besieging the Bastille; and in taking it, chiefly by infinite noise, the Gardes Françaises at length mutely assisting in the rear. Bastille falls, “like the City of Jericho, by sound,” Tuesday, July 14, 1789. Kind of “firebaptism” to the Revolution; which continues insuppressible thenceforth, and beyond hope of suppression. All France, as National Guards, to suppress Brigands and enemies to the making of the Constitution,” takes arms.

1789. AUGUST‒OCTOBER.

Scipio Americanus, Mayor Bailly and “Patrollotism versus Patriotism” (August, September). Hope, terror, suspicion, excitement, rising ever more, towards the transcendental pitch;—continued scarcity of grain. Progress towards Fifth of October, called here “Insurrection of Women.” Regiment de Flandre has come to Versailles (September 23); Officers have had a dinner (October 3), with much demonstration and gesticulative foolery, of an anti-constitutional and monarchic character. Paris, semi-delirious, hears of it (Sunday, October 4), with endless emotion;—next day, some “10,000 women” (men being under awe of “Patrollotism”) march upon Versailles; followed by endless miscellaneous multitudes, and finally by Lafayette and National Guards. Phenomena and procedure there. Result is, they bring the Royal Family and National Assembly home with them to Paris; Paris thereafter centre of the Revolution, and October Five a memorable day.

1789. OCTOBER‒DECEMBER.

“First Emigration,” of certain higher Noblesse and Princes of the Blood; which more or less continues through the ensuing years, and at length on an altogether profuse scale. Much legal inquiring and procedure as to Philippe d’Orléans and his (imaginary) concern in this Fifth of October; who retires to England for a while, and is ill seen by the polite classes there.

Part II: the Constitution (January 1790–August 12, 1792.)

1790.

Constitution-building, and its difficulties and accompaniments. Clubs, Journalisms; advent of anarchic souls from every quarter of the world. February 4, King’s visit to Constituent Assembly; emotion thereupon and National Oath, which flies over France. Progress of swearing it, detailed. General “Federation,” or mutual Oath of all Frenchmen, otherwise called “Feast of Pikes” (July 14, Anniversary of Bastille-day), which also is a memorable Day. Its effects on the Military, in Lieutenant Napoleon Bonaparte’s experience.

General disorganization of the Army, and attempts to mend it. Affair of Nanci (catastrophe is August 31); called “Massacre of Nanci”; irritation thereupon. Mutineer Swiss sent to the Galleys; solemn Funeral-service for the Slain at Nanci (September 20), and riotous menaces and mobs in consequence. Steady progress of disorganization, of anarchy spiritual and practical. Mirabeau, desperate of Constitution-building under such accompaniments, has interviews with the Queen, and contemplates great things.

1791. APRIL‒JULY.

Death of Mirabeau (April 2): last chance of guiding or controlling this Revolution gone thereby. Royal Family, still hopeful to control it, means to get away from Paris as the first step. Suspected of such intention; visit to St. Cloud violently prevented by the Populace (April 19). Actual Flight to Varennes (June 20); and misventures there: return captive to Paris, in a frightfully worsened position, the fifth evening after (June 25): “Republic” mentioned in Placards, during King’s Flight; generally reprobated. Queen and Barnave. A Throne held up; as if “set on its vertex,” to be held there by hand. Should not this runaway King be deposed? Immense assemblage, petitioning at Altar of Fatherland to that effect (Sunday, July 17), is dispersed by musketry, from Lafayette and Mayor Bailly, with extensive shrieks following, and leaving remembrances of a very bitter kind.

1791. AUGUST.

Foreign Governments, who had long looked with disapproval on the French Revolution, now set about preparing for actual interference. Convention of Pilnitz (August 25–27): Emperor Leopold II, Friedrich Wilhelm II, King of Prussia, with certain less important Potentates, and Emigrant Princes of the Blood, assembling at this Pilnitz (Electoral Country-house near Dresden), express their sorrow and concern at the impossible posture of his now French Majesty, which they think calls upon regular Governments to interfere and mend it: they themselves, prepared at present to “resist French aggression” on their own territories, will co-operate with said Governments in “interfering by effectual methods.” This Document, of date August 27, 1791, rouses violent indignations in France; which blaze up higher and higher, and are not quenched for twenty-five years after. Constitution finished; accepted by the King (September 14); Constituent Assembly proclaims “in a sonorous voice” (September 30), that its Sessions are all ended;—and goes its way amid “illuminations.”

1791. OCTOBER‒DECEMBER.

Legislative Assembly, elected according to the Constitution, the first and also the last Assembly of that character, meets October 1, 1791: sat till September 21, 1792; a Twelve-month all but nine days. More republican than its predecessor; inferior in talent; destitute, like it, of parliamentary experience. Its debates, futilities, staggering parliamentary procedure (Book V, cc. 1–3). Court “pretending to be dead,”—not “aiding the Constitution to march.” Sunday, October 16, L’Escuyer, at Avignon, murdered in a Church; Massacres in the Ice-Tower follow. Suspicions of their King, and of each other; anxieties about foreign attack, and whether they are in a right condition to meet it; painful questionings of Ministers, continual changes of Ministry,—occupy France and its Legislative with sad debates, growing ever more desperate and stormy in the coming months. Narbonne (Madame de Staël’s friend) made War-Minister, December 7; continues for nearly half a year; then Servan, who lasts three months; then Dumouriez, who, in that capacity, lasts only five days (had, with Roland as Home Minister, been otherwise in place for a year or more); mere “Ghosts of Ministries.”

1792. FEBRUARY‒APRIL.

Terror of rural France (February–March); Camp of Jalès; copious Emigration. February 7, Emperor Leopold and the King of Prussia, mending their Pilnitz offer, make public Treaty, That they specially will endeavour to keep down disturbances, and if attacked will assist one another. Sardinia, Naples, Spain, and even Russia and the Pope, understood to be in the rear of these two. April 20, French Assembly, after violent debates, decrees war against Emperor Leopold. This is the first Declaration of War; which the others followed, pro and contra, all around, like pieces of a great Firework blazing out now here now there. The Prussian Declaration, which followed first, some months after, is the immediately important one.

1792. JUNE.

In presence of these alarming phenomena, Government cannot act; will not, say the People. Clubs, Journalists, Sections (organized population of Paris) growing ever more violent and desperate. Issue forth (June 20) in vast Procession, the combined Sections and leaders, with banners, with demonstrations; marching through the streets of Paris, “To quicken the Executive,” and give it a fillip as to the time of day. Called “Procession of the Black Breeches” in this Book. Immense Procession, peaceable but dangerous; finds the Tuileries gates closed, and no access to his Majesty; squeezes, crushes, and is squeezed, crushed against the Tuileries gates and doors till they give way; and the admission to his Majesty, and the dialogue with him, and behaviour in his House, are of an utterly chaotic kind, dangerous and scandalous, though not otherwise than peaceable. Giving rise to much angry commentary in France and over Europe. June Twenty henceforth a memorable Day. General Lafayette suddenly appears in the Assembly; without leave, as is splenetically observed: makes fruitless attempts to reinstate authority in Paris (June 28); withdraws as an extinct popularity.

1792. JULY.

July 6, Reconciliatory Scene in the Assembly, derisively called Baiser L’amourette. “Third Federation,” July 14, being at hand,—could not the assembling “Federates” be united into some Nucleus of Force near Paris? Court answers, No; not without reason of its own. Barbaroux writes to Marseilles for “500 men that know how to die”; who accordingly get under way, though like to be too late for the Federation. Sunday, July 22, Solemn Proclamation that the “Country is in Danger.”

July 24, Prussian Declaration of War; and Duke of Brunswick’s celebrated Manifesto, threatening France “with military execution” if Royalty were meddled with: the latter bears date, Coblentz, July 27, 1792, in the name of both Emperor and King of Prussia. Duke of Brunswick commands in chief: Nephew (sister’s son) of Frederick the Great; and Father of our unlucky “Queen Caroline”: had served, very young, in the Seven Years War, under his Father’s Brother, Prince Ferdinand; often in command of detachments bigger or smaller; and had gained distinction by his swift marches, audacity and battle-spirit: never hitherto commanded any wide system of operations; nor ever again till 1806, when he suddenly encountered ruin and death at the very starting (Battle of Jena, October 14 of that year). This Proclamation, which awoke endless indignation in France and much criticism in the world elsewhere, is understood to have been prepared by other hands (French-Emigrants chiefly, who were along with him in force), and to have been signed by the Duke much against his will. “Insigne vengeance,” “military execution,” and other terms of overbearing menace: Prussian Army, and Austrians from Netherlands, are advancing in that humour. Marseillese, “who know how to die,” arrive in Paris (July 29); dinner-scene in the Champs Elysées.

1792. AUGUST.

Indignation waxing desperate at Paris: France, boiling with ability and will, tied up from defending itself by “an inactive Government” (fatally unable to act). Secret conclaves, consultations of Municipality and Clubs; Danton understood to be the presiding genius there. Legislative Assembly is itself plotting and participant; no other course for it. August 10, Universal Insurrection of the Armed Population of Paris; Tuileries forced, Swiss Guards cut to pieces. King, when once violence was imminent, and before any act of violence, had with Queen and Dauphin sought shelter in the Legislative-Assembly Hall. They continue there till August 13 (Friday-Monday), listening to the debates, in a reporter’s box. Are conducted thence to the Temple “as Hostages,”— do not get out again except to die. Legislative Assembly has its Decree ready, That in terms of the Constitution in such alarming crisis a National Convention (Parliament with absolute powers) shall be elected; Decree issued that same day, August 10, 1792. After which the Legislative only waits in existence till it be fulfilled.

Part III: the Guillotine (August 10, 1792–October 4, 1795.)

1792. AUGUST–SEPTEMBER.

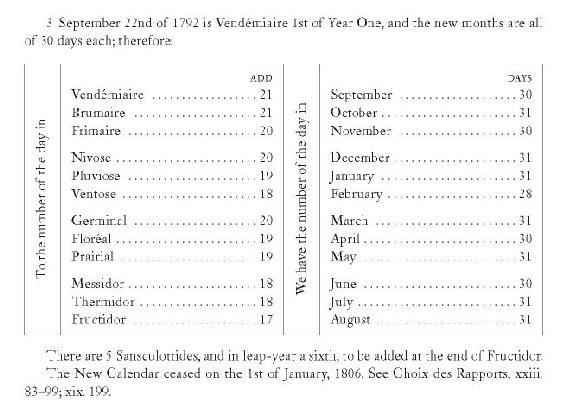

Legislative continues its sittings till Election be completed. Enemy advancing, with armed Emigrants, enter France, Luxembourg region; take Longwy, almost without resistance (August 23); prepare to take Verdun. Austrians besieging Thionville; cannot take it. Dumouriez seizes the Passes of Argonne, August 29. Great agitation in Paris. Sunday, September 2, and onwards till Thursday 6, September Massacres: described Book I, cc. 4–6. Prussians have taken Verdun, September 2 (Sunday, while the Massacres are beginning): except on the score of provisions and of weather, little or no hindrance. Dumouriez waiting in the Passes of Argonne. Prussians detained three weeks forcing these. Famine, and torrents of rain. Battle or Cannonade of Vamly (September 20): French do not fly, as expected. Convention meets, September 22, 1792; Legislative had sat till the day before, and now gives place to it: Republic decreed, same day. Austrians, renouncing Thionville, besiege Lille (September 28–October 8); cannot: “fashionable shaving-dish,” the splinter of a Lille bombshell. Prussians, drenched deep in mud, in dysentery and famine, are obliged to retreat: Goethe’s account of it. Total failure of that Brunswick Enterprise.

1792. DECEMBER–1793. JANUARY.

Revolutionary activities in Paris and over France; King shall be brought to “trial.” Trial of the King (Tuesday, December 11–Sunday 16). Three Votes (January 15–17, 1793): Sentence, Death without respite. Executed Monday, January 21, 1793, morning about 10 o’clock. English Ambassador quits Paris; French Ambassador ordered to quit England (January 24). War between the two countries imminent.

1793. FEBRUARY.

Dumouriez, in rear of the retreating Austrians, has seized the whole Austrian Netherlands, in a month or less (November 4–December 2 last); and now holds that territory. February 1, France declares War against England and Holland; England declares in return, February 11: Dumouriez immediately invades Holland; English, under Duke of York, go to the rescue: rather successful at first. Committee of Salut hence. June 1, Howe’s Sea-victory; and Fable of the Vengeur. General Jourdan: Battle of Fleurus, sore stroke against the Austrian Netherlands (June 26).

Conspiracy of Mountain against Robespierre: Tallien and others desirous not to be “eaten.” Last scenes of Robespierre: July 28 (10 Thermidor, Year 2), guillotined with his Consorts;—which, unexpectedly, ends the Reign of Terror. Victorious French Armies: enter Cologne, October 6; masters of Spanish bulwarks (Dugommier shot), October 17: Duke of York and Dutch Stadtholder in a ruinous condition. Reaction against Robespierre: “whole Nation a Committee of Mercy.” Jacobins Club assaulted by mob; shut up, November 10–12. Law of Maximum abolished, December 24. Duke of York gone home; Pichegru and 70,000 overrun Holland; frost so hard, “hussars can take ships.”

1795.

Stadtholder quits Holland, January 19; glad to get across to England. Spanish Cities “opening to the petard” (Rosas first, January 5, and rapidly thereafter, till almost Madrid come in view). Continued downfall of Sansculottism. Effervescence of luxury; La Cabarus; Greek Costumes; Jeunesse Dorée; balls in flesh-coloured drawers. Sansculottism rises twice in Insurrection; both times in vain. Insurrection of Germinal (“12 Germinal,” Year 3, April 1, 1795); ends by “two blank cannon-shot” from Pichegru.

1795. APRIL–OCTOBER.

Prussia makes Peace of Bâle (Basel), April 5; Spain, Peace of Bâle is three months later. Armies everywhere successful: Catalogue of Victories and Conquests hung up in the Convention Hall. Famine of the lower classes. Fouquier-Tinville guillotined (May 8). Insurrection of Prairial, the Second attempt of Sansculottism to recover power (“1 Prairial,” May 20); Deputy Féraud massacred:—issues in the Disarming and Finishing of Sansculottism. Emigrant Invasion, in English ships, lands at Quiberon, and is blown to pieces (July 15–20): La Vendée, which had before been three years in Revolt, is hereby kindled into a “Second” less important “Revolt of La Vendée,” which lasts some eight months. Reactionary “Companies of Jesus,” “Companies of the Sun,” assassinating Jacobins in the Rhone Countries (July–August ). New Constitution: Directory and Consuls,—Two-thirds of the Convention to be re-elected. Objections to that clause. Section Lepelletier, and miscellaneous Discontented, revolt against it: Insurrection of Vendémiaire, Last of the Insurrections (“13 Vendémiaire, Year 4,” October 5, 1795); quelled by Napoleon. On which “The Revolution as defined here, ends,—Anarchic Government, if still anarchic, proceeding by softer methods than that of continued insurrection.

Part I: The Bastille

Book I: Death of Louis XV

Chapter I: Louis the Well-beloved

President Hénault, remarking on royal Surnames of Honour how difficult it often is to ascertain not only why, but even when, they were conferred, takes occasion in his sleek official way to make a philosophical reflection. “The Surname of Bien-aimé (Well-beloved),” says he, “which Louis XV bears, will not leave posterity in the same doubt. This Prince, in the year 1744, while hastening from one end of his kingdom to the other, and suspending his conquests in Flanders that he might fly to the assistance of Alsace, was arrested at Metz by a malady which threatened to cut short his days. At the news of this, Paris, all in terror, seemed a city taken by storm: the churches resounded with supplications and groans; the prayers of priests and people were every moment interrupted by their sobs: and it was from an interest so dear and tender that this Surname of Bien-aimé fashioned itself,—a title higher still than all the rest which this great Prince has earned.”[6]

So stands it written; in lasting memorial of that year 1744. Thirty other years have come and gone; and “this great Prince” again lies sick; but in how altered circumstances now! Churches resound not with excessive groanings; Paris is stoically calm; sobs interrupt no prayers, for indeed none are offered; except Priests’ Litanies, read or chanted at fixed money-rate per hour, which are not liable to interruption. This shepherd of the people has been carried home from Little Trianon, heavy of heart, and been put to bed in his own Château of Versailles: the flock knows it, and heeds it not. At most, in the immeasurable tide of French Speech (which ceases not day after day, and only ebbs towards the short hours of night), may this of the royal sickness emerge from time to time as an article of news. Bets are doubtless depending; nay, some people “express themselves loudly in the streets.”[7] But for the rest, on green field and steepled city, the May sun shines out, the May evening fades; and men ply their useful or useless business as if no Louis lay in danger.

Dame Dubarry, indeed, might pray, if she had a talent for it; Duke d’Aiguillon too, Maupeou and the Parlement Maupeou: these, as they sit in their high places, with France harnessed under their feet, know well on what basis they continue there. Look to it, D’Aiguillon; sharply as thou didst, from the Mill of St. Cast, on Quiberon and the invading English; thou “covered if not with glory yet with meal!” Fortune was ever accounted inconstant: and each dog has but his day.

Forlorn enough languished Duke d’Aiguillon, some years ago; covered, as we said, with meal; nay with worse. For La Chalotais, the Breton Parlementeer, accused him not only of poltroonery and tyranny, but even concussion (official plunder of money); which accusations it was easier to get “quashed” by backstairs Influences than to get answered: neither could the thoughts, or even the tongues of men be tied. Thus, under disastrous eclipse, had this grand-nephew of the great Richelieu to glide about; unworshipped by the world; resolute Choiseul, the abrupt proud man, disdaining him, or even forgetting him. Little prospect but to glide into Gascony, to rebuild Châteaus there,[8]and die inglorious killing game! However, in the year 1770, a certain young soldier, Dumouriez by name, returning from Corsica, could see “with sorrow, at Compiègne, the old King of France, on foot, with doffed hat, in sight of his army, at the side of a magnificent phaeton, doing homage to the—Dubarry.”[9]

Much lay therein! Thereby, for one thing, could D’Aiguillon postpone the rebuilding of his Château, and rebuild his fortunes first. For stout Choiseul would discern in the Dubarry nothing but a wonderfully dizened Scarlet-woman; and go on his way as if she were not. Intolerable: the source of sighs, tears, of pettings and poutings; which would not end till “France” (La France, as she named her royal valet) finally mustered heart to see Choiseul; and with that “quivering in the chin” (tremblement du menton) natural in such case,[10] faltered out a dismissal: dismissal of his last substantial man, but pacification of his Scarlet-woman. Thus D’Aiguillon rose again, and culminated. And with him there rose Maupeou, the banisher of Parlements; who plants you a refractory President “at Croe in Combrailles on the top of steep rocks, inaccessible except by litters,” there to consider himself. Likewise there rose Abbé Terray, dissolute Financier, paying eightpence in the shilling,—so that wits exclaim in some press at the playhouse, “Where is Abbé Terray, that he might reduce us to two-thirds!” And so have these individuals (verily by black-art) built them a Domdaniel, or enchanted Dubarrydom; call it an Armida-Palace, where they dwell pleasantly; Chancellor Maupeou “playing blindman’s-buff” with the scarlet Enchantress; or gallantly presenting her with dwarf Negroes;—and a Most Christian King has unspeakable peace within doors, whatever he may have without. “My Chancellor is a scoundrel; but I cannot do without him.”[11]

Beautiful Armida-Palace, where the inmates live enchanted lives; lapped in soft music of adulation; waited on by the splendours of the world;—which nevertheless hangs wondrously as by a single hair. Should the Most Christian King die; or even get seriously afraid of dying! For, alas, had not the fair haughty Chateauroux to fly, with wet cheeks and flaming heart, from that Fever-scene at Metz, long since; driven forth by sour shavelings? She hardly returned, when fever and shavelings were both swept into the background. Pompadour too, when Damiens wounded Royalty “slightly, under the fifth rib,” and our drive to Trianon went off futile, in shrieks and madly shaken torches,—had to pack, and be in readiness: yet did not go, the wound not proving poisoned. For his Majesty has religious faith; believes, at least in a Devil. And now a third peril; and who knows what may be in it! For the Doctors look grave; ask privily, If his Majesty had not the small-pox long ago?—and doubt it may have been a false kind. Yes, Maupeou, pucker those sinister brows of thine, and peer out on it with thy malign rat-eyes: it is a questionable case. Sure only that man is mortal; that with the life of one mortal snaps irrevocably the wonderfullest talisman, and all Dubarrydom rushes off, with tumult, into infinite Space; and ye, as subterranean Apparitions are wont, vanish utterly,—leaving only a smell of sulphur!

These, and what holds of these may pray,—to Beelzebub, or whoever will hear them. But from the rest of France there comes, as was said, no prayer; or one of an opposite character, “expressed openly in the streets.” Château or Hôtel, where an enlightened Philosophism scrutinizes many things, is not given to prayer: neither are Rossbach victories, Terray Finances, nor, say only “sixty thousand Lettres de Cachet” (which is Maupeou’s share), persuasives towards that. O Hénault! Prayers? From a France smitten (by black-art) with plague after plague; and lying now, in shame and pain, with a Harlot’s foot on its neck, what prayer can come? Those lank scarecrows, that prowl hunger-stricken through all highways and byways of French Existence, will they pray? The dull millions that, in the workshop or furrowfield, grind foredone at the wheel of Labour, like haltered gin-horses, if blind so much the quieter? Or they that in the Bicêtre Hospital, “eight to a bed,” lie waiting their manumission? Dim are those heads of theirs, dull stagnant those hearts: to them the great Sovereign is known mainly as the great Regrater of Bread. If they hear of his sickness, they will answer with a dull Tant pis pour lui; or with the question, Will he die?

Yes, will he die? that is now, for all France, the grand question, and hope; whereby alone the King’s sickness has still some interest.

Chapter II: Realized Ideals

Such a changed France have we; and a changed Louis. Changed, truly; and further than thou yet seest!—To the eye of History many things, in that sick-room of Louis, are now visible, which to the Courtiers there present were invisible. For indeed it is well said, “in every object there is inexhaustible meaning; the eye sees in it what the eye brings means of seeing.” To Newton and to Newton’s Dog Diamond, what a different pair of Universes; while the painting on the optical retina of both was, most likely, the same! Let the Reader here, in this sick-room of Louis, endeavour to look with the mind too.

Time was when men could (so to speak) of a given man, by nourishing and decorating him with fit appliances, to the due pitch, make themselves a King, almost as the Bees do; and, what was still more to the purpose, loyally obey him when made. The man so nourished and decorated, thenceforth named royal, does verily bear rule; and is said, and even thought, to be, for example, “prosecuting conquests in Flanders,” when he lets himself like luggage be carried thither: and no light luggage; covering miles of road. For he has his unblushing Chateauroux, with her bandboxes and rouge-pots, at his side; so that, at every new station, a wooden gallery must be run up between their lodgings. He has not only his Maison-Bouche, and Valetaille without end, but his very Troop of Players, with their pasteboard coulisses, thunder-barrels, their kettles, fiddles, stage-wardrobes, portable larders (and chaffering and quarrelling enough); all mounted in wagons, tumbrils, second-hand chaises,—sufficient not to conquer Flanders, but the patience of the world. With such a flood of loud jingling appurtenances does he lumber along, prosecuting his conquests in Flanders: wonderful to behold. So nevertheless it was and had been: to some solitary thinker it might seem strange; but even to him, inevitable, not unnatural.

For ours is a most fictile world; and man is the most fingent plastic of creatures. A world not fixable; not fathomable! An unfathomable Somewhat, which is Not we; which we can work with, and live amidst,—and model, miraculously in our miraculous Being, and name World.—But if the very Rocks and Rivers (as Metaphysic teaches) are, in strict language, made by those Outward Senses of ours, how much more, by the Inward Sense, are all Phenomena of the spiritual kind: Dignities, Authorities, Holies, Unholies! Which inward sense, moreover, is not permanent like the outward ones, but for ever growing and changing. Does not the Black African take of Sticks and Old Clothes (say, exported Monmouth-Street cast-clothes) what will suffice; and of these, cunningly combining them, fabricate for himself an Eidolon (Idol, or Thing Seen), and name it Mumbo-Jumbo; which he can thenceforth pray to, with upturned awestruck eye, not without hope? The white European mocks; but ought rather to consider; and see whether he, at home, could not do the like a little more wisely.

So it was, we say, in those conquests of Flanders, thirty years ago: but so it no longer is. Alas, much more lies sick than poor Louis: not the French King only, but the French Kingship; this too, after long rough tear and wear, is breaking down. The world is all so changed; so much that seemed vigorous has sunk decrepit, so much that was not is beginning to be!—Borne over the Atlantic, to the closing ear of Louis, King by the Grace of God, what sounds are these; muffledominous, new in our centuries? Boston Harbour is black with unexpected Tea: behold a Pennsylvanian Congress gather; and ere long, on Bunker Hill, DEMOCRACY announcing, in rifle-volleys death-winged, under her Star Banner, to the tune of Yankee-doodle-doo, that she is born, and, whirlwind-like, will envelop the whole world!

Sovereigns die and Sovereignties; how all dies, and is for a Time only; is a “Time-phantasm, yet reckons itself real!” The Merovingian Kings, slowly wending on their bullock-carts through the streets of Paris, with their long hair flowing, have all wended slowly on,—into Eternity. Charlemagne sleeps at Salzburg, with truncheon grounded; only Fable expecting that he will awaken. Charles the Hammer, Pepin Bow-legged, where now is their eye of menace, their voice of command? Rollo and his shaggy Northmen cover not the Seine with ships; but have sailed off on a longer voyage. The hair of Towhead (Tête d’étoupes) now needs no combing; Iron-cutter (Taillefer) cannot cut a cobweb; shrill Fredegonda, shrill Brunhilda have had out their hot life-scold, and lie silent, their hot life-frenzy cooled. Neither from that black Tower de Nesle descends now darkling the doomed gallant, in his sack, to the Seine waters; plunging into Night; for Dame de Nesle now cares not for this world’s gallantry, heeds not this world’s scandal; Dame de Nesle is herself gone into Night. They are all gone; sunk,— down, down, with the tumult they made; and the rolling and the trampling of ever new generations passes over them; and they hear it not any more for ever.

And yet withal has there not been realized somewhat? Consider (to go no further) these strong Stone-edifices, and what they hold! Mud-Town of the Borderers (Lutetia Parisiorum or Barisiorum) has paved itself, has spread over all the Seine Islands, and far and wide on each bank, and become City of Paris, sometimes boasting to “Athens of Europe,” and even “Capital of the Universe.” Stone towers frown aloft; long-lasting, grim with a thousand years. Cathedrals are there, and a Creed (or memory of a Creed) in them; Palaces, and a State and Law. Thou seest the Smoke-vapour; unextinguished Breath as of a thing living. Labour’s thousand hammers ring on her anvils: also a more miraculous Labour works noiselessly, not with the Hand but with the Thought. How have cunning workmen in all crafts, with their cunning head and right-hand, tamed the Four Elements to be their ministers; yoking the Winds to their Sea-chariot, making the very Stars their Nautical Timepiece;—and written and collected a Bibliothèque du Roi; among whose Books is the Hebrew BOOK! A wondrous race of creatures: these have been realized, and what of Skill is in these: call not the Past Time, with all its confused wretchednesses, a lost one.

Observe, however, that of man’s whole terrestrial possessions and attainments, unspeakably the noblest are his Symbols, divine or divine-seeming; under which he marches and fights, with victorious assurance, in this life-battle; what we can call his Realized Ideals. Of which realized Ideals, omitting the rest, consider only these two: his Church, or spiritual Guidance; his Kingship, or temporal one. The Church: what a word was there; richer than Golconda and the treasures of the world! In the heart of the remotest mountains rises the little Kirk; the Dead all slumbering round it, under their white memorial-stones, “in hope of a happy resurrection”: dull wert thou, O Reader, if never in any hour (say of moaning midnight, when such Kirk hung spectral in the sky, and Being was as if swallowed up of Darkness) it spoke to thee—things unspeakable, that went to thy soul’s soul. Strong was he that had a Church, what we can call a Church: he stood thereby, though “in the centre of Immensities, in the conflux of Eternities,” yet manlike towards God and man; the vague shoreless Universe had become for him a firm city, and dwelling which he knew. Such virtue was in Belief; in these words, well spoken: I believe. Well might men prize their Credo, and raise stateliest Temples for it, and reverend Hierarchies, and give it the tithe of their substance; it was worth living for and dying for.

Neither was that an inconsiderable moment when wild armed men first raised their Strongest aloft on the buckler-throne; and, with clanging armour and hearts, said solemnly: Be thou our Acknowledged Strongest! In such Acknowledged Strongest (well named King, Könning, Can-ning, or Man that was Able) what a Symbol shone now for them,—significant with the destinies of the world! A Symbol of true Guidance in return for loving Obedience; properly, if he knew it, the prime want of man. A Symbol which might be called sacred; for is there not, in reverence for what is better than we, an indestructible sacredness? On which ground, too, it was well said there lay in the Acknowledged Strongest a divine right; as surely there might in the Strongest, whether Acknowledged or not,—considering who it was that made him strong. And so, in the midst of confusions and unutterable incongruities (as all growth is confused), did this of Royalty, with Loyalty environing it, spring up; and grow mysteriously, subduing and assimilating (for a principle of Life was in it); till it also had grown world-great, and was among the main Facts of our modern existence. Such a Fact, that Louis XIV, for example, could answer the expostulatory Magistrate with his “L’Etat c’est moi (The State? I am the State)”; and be replied to by silence and abashed looks. So far had accident and forethought; had your Louis Elevenths, with the leaden Virgin in their hatband, and torture-wheels and conical oubliettes (man-eating!) under their feet; your Henri Fourths, with their prophesied social millennium, “when every peasant should have his fowl in the pot”; and on the whole, the fertility of this most fertile Existence, named of Good and Evil,—brought it, in the matter of the Kingship. Wondrous! Concerning which may we not again say, that in the huge mass of Evil, as it rolls and swells, there is ever some Good working imprisoned; working towards deliverance and triumph?

How such Ideals do realize themselves; and grow, wondrously, from amid the incongruous ever-fluctuating chaos of the Actual: this is what World-History, if it teach any thing, has to teach us. How they grow; and, after long stormy growth, bloom out mature, supreme; then quickly (for the blossom is brief) fall into decay; sorrowfully dwindle; and crumble down, or rush down, noisily or noiselessly disappearing. The blossom is so brief; as of some centennial Cactus-flower, which after a century of waiting shines out for hours! Thus from the day when rough Clovis, in the Champ de Mars, in sight of his whole army, had to cleave retributively the head of that rough Frank, with sudden battle-axe, and the fierce words, “It was thus thou clavest the vase” (St. Remi’s and mine) “at Soissons,” forward to Louis the Grand and his L’Etat c’est moi, we count some twelve hundred years: and now this the very next Louis is dying, and so much dying with him!—Nay, thus too if Catholicism, with and against Feudalism (but not against Nature and her bounty), gave us English a Shakespeare and Era of Shakespeare, and so produced a blossom of Catholicism—it was not till Catholicism itself, so far as Law could abolish it, had been abolished here.

But of those decadent ages in which no Ideal either grows or blossoms? When Belief and Loyalty have passed away, and only the cant and false echo of them remains; and all Solemnity has become Pageantry; and the Creed of persons in authority has become one of two things: an Imbecility or a Machiavelism? Alas, of these ages World-History can take no notice; they have to become compressed more and more, and finally suppressed in the Annals of Mankind; blotted out as spurious,—which indeed they are. Hapless ages: wherein, if ever in any, it is an unhappiness to be born. To be born, and to learn only, by every tradition and example, that God’s Universe is Belial’s and a Lie; and “the Supreme Quack” the hierarch of men! In which mournfullest faith, nevertheless, do we not see whole generations (two, and sometimes even three successively) live, what they call living; and vanish,—without chance of reappearance?

In such a decadent age, or one fast verging that way, had our poor Louis been born. Grant also that if the French Kingship had not, by course of Nature, long to live, he of all men was the man to accelerate Nature. The blossom of French Royalty, cactus-like, has accordingly made an astonishing progress. In those Metz days, it was still standing with all its petals, though bedimmed by Orleans Regents and Roué Ministers and Cardinals; but now, in 1774, we behold it bald, and the virtue nigh gone out of it.

Disastrous indeed does it look with those same “realized Ideals,” one and all! The Church, which in its palmy season, seven hundred years ago, could make an Emperor wait barefoot, in penance-shirt, three days, in the snow, has for centuries seen itself decaying; reduced even to forget old purposes and enmities, and join interest with the Kingship: on this younger strength it would fain stay its decrepitude; and these two will henceforth stand and fall together. Alas, the Sorbonne still sits there, in its old mansion; but mumbles only jargon of dotage, and no longer leads the consciences of men: not the Sorbonne; it is Encyclopédies, Philosophie, and who knows what nameless innumerable multitude of ready Writers, profane Singers, Romancers, Players, Disputators, and Pamphleteers, that now form the Spiritual Guidance of the world. The world’s Practical Guidance too is lost, or has glided into the same miscellaneous hands. Who is it that the King (Able-man, named also Roi, Rex, or Director) now guides? His own huntsmen and prickers: when there is to be no hunt, it is well said, “Le Roi ne fera rien (To-day his Majesty will do nothing).”[12] He lives and linger there, because he is living there, and none has yet laid hands on him.

The Nobles, in like manner, have nearly ceased either to guide or misguide; and are now, as their master is, little more than ornamental figures. It is long since they have done with butchering one another or their king: the Workers, protected, encouraged by Majesty, have ages ago built walled towns, and there ply their crafts; will permit no Robber Baron to “live by the saddle,” but maintain a gallows to prevent it. Ever since that period of the Fronde, the Noble has changed his fighting sword into a court rapier; and now loyally attends his King as ministering satellite; divides the spoil, not now by violence and murder, but by soliciting and finesse. These men call themselves supports of the throne: singular gilt-pasteboard caryatides in that singular edifice! For the rest, their privileges every way are now much curtailed. That Law authorizing a Seigneur, as he returned from hunting, to kill not more than two Serfs, and refresh his feet in their warm blood and bowels, has fallen into perfect desuetude,— and even into incredibility; for if Deputy Lapoule can believe in it, and call for the abrogation of it, so cannot we.[13] No Charolois, for these last fifty years, though never so fond of shooting, has been in use to bring down slaters and plumbers, and see them roll from their roofs;[14] but contents himself with partridges and grouse. Close-viewed, their industry and function is that of dressing gracefully and eating sumptuously. As for their debauchery and depravity, it is perhaps unexampled since the era of Tiberius and Commodus. Nevertheless, one has still partly a feeling with the lady Maréchale. “Depend upon it, Sir, God thinks twice before damning a man of that quality.”[15] These people, of old, surely had virtues, uses; or they could not have been there. Nay, one virtue they are still required to have (for mortal man cannot live without a conscience): the virtue of perfect readiness to fight duels.

Such are the shepherds of the people: and now how fares it with the flock? With the flock, as is inevitable, it fares ill, and ever worse. They are not tended, they are only regularly shorn. They are sent for, to do statute-labour, to pay statue-taxes; to fatten battlefields (named “bed of honour”) with their bodies, in quarrels which are not theirs; their hand and toil is in every possession of man; but for themselves they have little or no possession. Untaught, uncomforted, unfed; to pine stagnantly in thick obscuration, in squalid destitution and obstruction: this is the lot of the millions; peuple taillable et corvéable à merci et miséricorde. In Brittany they once rose in revolt at the first introduction of Pendulum Clocks; thinking it had something to do with the Gabelle. Paris requires to be cleared out periodically by the Police; and the horde of hunger-stricken vagabonds to be sent wandering again over space—for a time. “During one such periodical clearance,” says Lacretelle, “in May, 1750, the Police had presumed withal to carry off some reputable people’s children, in the hope of extorting ransoms for them. The mothers fill the public places with cries of despair; crowds gather, get excited; so many women in distraction run about exaggerating the alarm: an absurd and horrid fable rises among the people; it is said that the Doctors have ordered a Great Person to take baths of young human blood for the restoration of his own, all spoiled by debaucheries. Some of the rioters,” adds Lacretelle, quite coolly, “were hanged on the following days”: the Police went on.[16]O ye poor naked wretches! and this then is your inarticulate cry to Heaven, as of a dumb tortured animal, crying from uttermost depths of pain and debasement? Do these azure skies, like a dead crystalline vault, only reverberate the echo of it on you? Respond to it only by “hanging on the following days”?—Not so: not for ever! Ye are heard in Heaven. And the answer too will come,—in a horror of great darkness, and shakings of the world, and a cup of trembling which all the nations shall drink.