Todd DePastino

Citizen Hobo

How a Century of Homelessness Shaped America

Part I: The Rise of Hobohemia, 1870 — 1920

The Making of America’s Tramp Army

Tasting of the “fountain of Indolence”: Origin Myths of Tramping

“From the Fraternity of Haut Beaus”

The Opening of the Wageworkers’ Frontier

Part II: Hobohemia and Homelessness in the Early Twentieth Century

5. “A Civilization without Homes”

Part III: The Decline and Fall of Hobohemia, 1920–1980

The Closing of the Wageworkers’ Frontier

A New Deal for the American Homeless

The Decline and Fall of Skid Row

Part IV: The Enduring Legacy: Homelessness and American Culture Since 1980

Front Matter

[Synopsis]

In the years following the Civil War, a veritable army of homeless men swept across America’s “wageworkers’ frontier” and forged a beguiling and bedeviling counterculture known as “hobohemia.” Celebrating unfettered masculinity and jealously guarding the American road as the preserve of white manhood, hoboes look command of downtown districts and swaggered onto center stage of the new urban culture Less obviously, perhaps, they also staked their own claims on the American polity claims that would in fact transform the very entitlements of American citizenship.

In this eye-opening work of American history, Todd DePastino tells the story of hohohemia’s rise and fall, and crafts a stunning new interpretation of the “American century” in the process. Drawing on sources ranging from diaries, letters, anil police reports to movies and memoirs, Citizen Hobo breathes life into the largely forgotten world of the road, but it also, crucially, shows how the hobo army so haunted the American body politic that it prompted the creation of an entirely new social order and political economy. DePastino illustrates how hoboes—with their reputation as dangers to civilization, sexual savages, and professional idlers—became a cultural and political force, influencing the creation of welfare state measures, the promotion of mass consumption, and the sub-urbanization of America Citizen Hohn’s sweeping retelling of American nationhood in light of enduring struggles over “home” does more than chart the change from “homelesness” to “houselessness.”- In its breadth and scope, the book oilers nothing less than an essential new context for thinking about Americans’ struggles against inequality and alienation

Cover illustrations:

Top: The “Bonus March” demonstration of 1932. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration. Center: The medallion “Hungry hut Alive” (1933), a “hobo nickel” carved from a coin by an unemployed man for barter. From the collection of Bill Fivaz. Used by permission. Bottom: Providence Bob and Philadelphia Shorty riding the rods in 1894. Butler-McCook House & Garden, Antiquarian & Landmarks Society.

Printed in the U.S.A.

[Title Page]

TODD DEPASTINO

Citizen

Hobo

HOW A

CENTURY OF

HOMELESSNESS

SHAPED

AMERICA

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

CHICAGO AND LONDON

[Copyright]

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

© 2003 by The University of Chicago

<br’all rights reserved. Published 2003

Paperback edition 2005

Printed in the United States of America

12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 2 3 4 5

ISBN: 0-226-14378-3

ISBN: 0-226-14379-1 (paperback)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

DePastino,Todd.

Citizen hobo : how a century of homelessness shaped America / Todd DePastino.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-226-14378-3 (alk. paper)

1. Tramps—United States—History. 2. Homelessness—United States—History.

3. Marginality, Social—United States—History. 4. Subculture—United States—History.

I. Title.

HV4504 D47 2003

305.5’68—dc21

2002154907

® The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48–1992.

[Dedication]

For Steph, Ellie, and Libbie

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Part I: The Rise of Hobohemia, 1870–1920

1. “The Great Army of Tramps”

The Making of America’s Tramp Army

Tasting from the “Fountain of Indolence”: Origin Myths of Tramping

2. The Other Side of the Road

”The Broken Home Circle”

From Patriarch to Pariah

”From the Fraternity of Haut Beaus”

3. “Hallelujah, I’m a Bum!“

The Opening of the Wageworkers’ Frontier

The Main Stem

”(White) Man’s Country”

Hobosexuality

Part II: Hobohemia and Homelessness in the Early Twentieth Century

4. The Politics of Hobohemia

Organizing the Main Stem

”The Song of the Jungles”

5. “A Civilization without Homes”

Reforming the Main Stem

The “Hotel Spirit”

The Comic Tramp

Part III: Resettling the Hobo Army, 1920–1980

6. The Decline and Fall of Hobohemia

The Closing of the Wageworker’s Frontier

Contesting Hobohemia

7. Forgotten Men

A New Deal for the American Homeless

Folklores of Homelessness

8. Coming Home

The Decline and Fall of Skid Row

Dharma Bums and Easy Riders

Part IV: The Enduring Legacy: Homelessness and American Culture Since 1980

9. Rediscovering Homelessness

The New Homeless

Romancing the Road, Surviving the Streets

Notes

Index

Illustrations

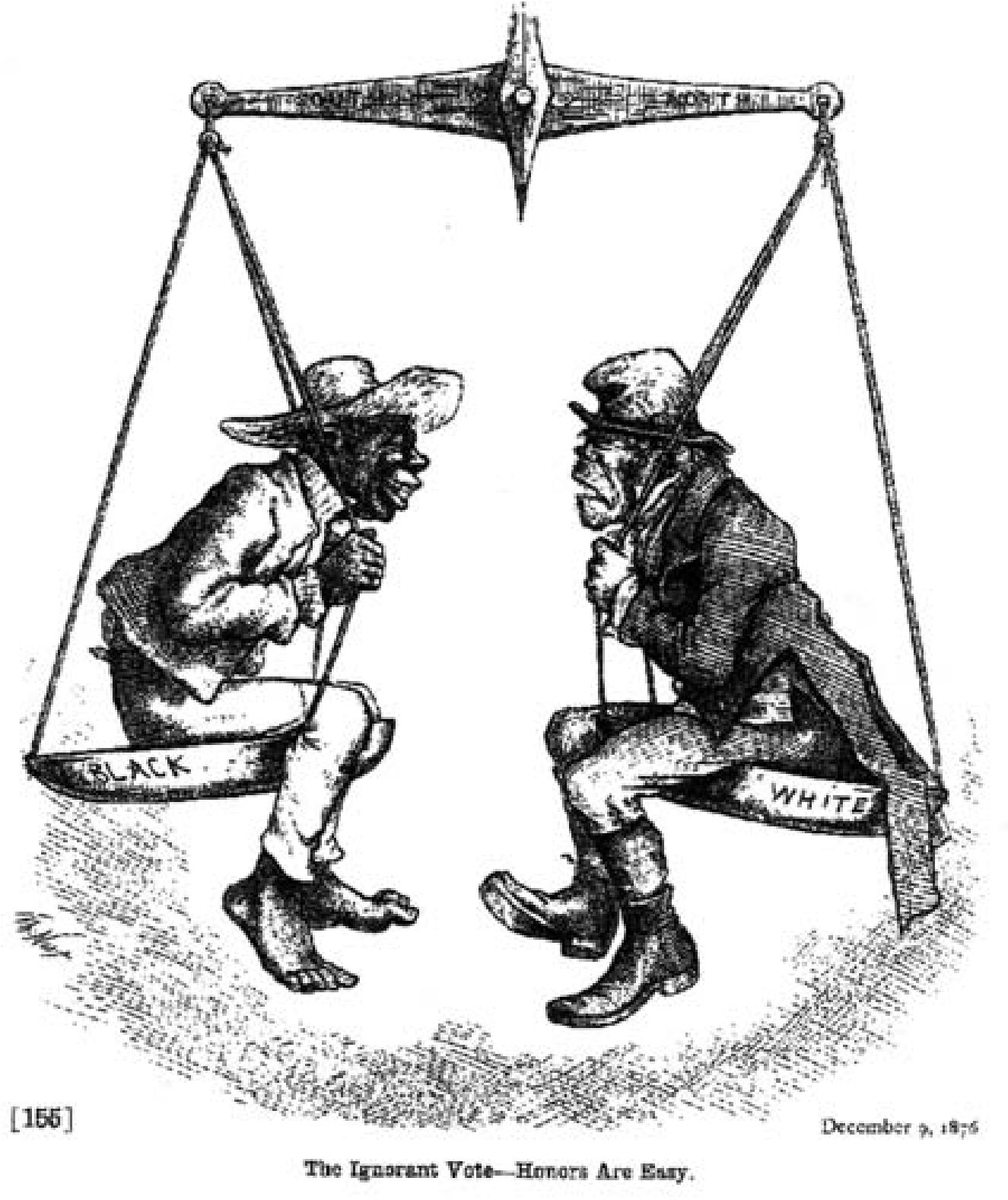

1.1. “The Ignorant Vote—Honors Are Easy,” Harper’s Weekly (December 9,1876) 21

1.2. “The Tramp,” Harper’s Weekly (September 2,1876) 28

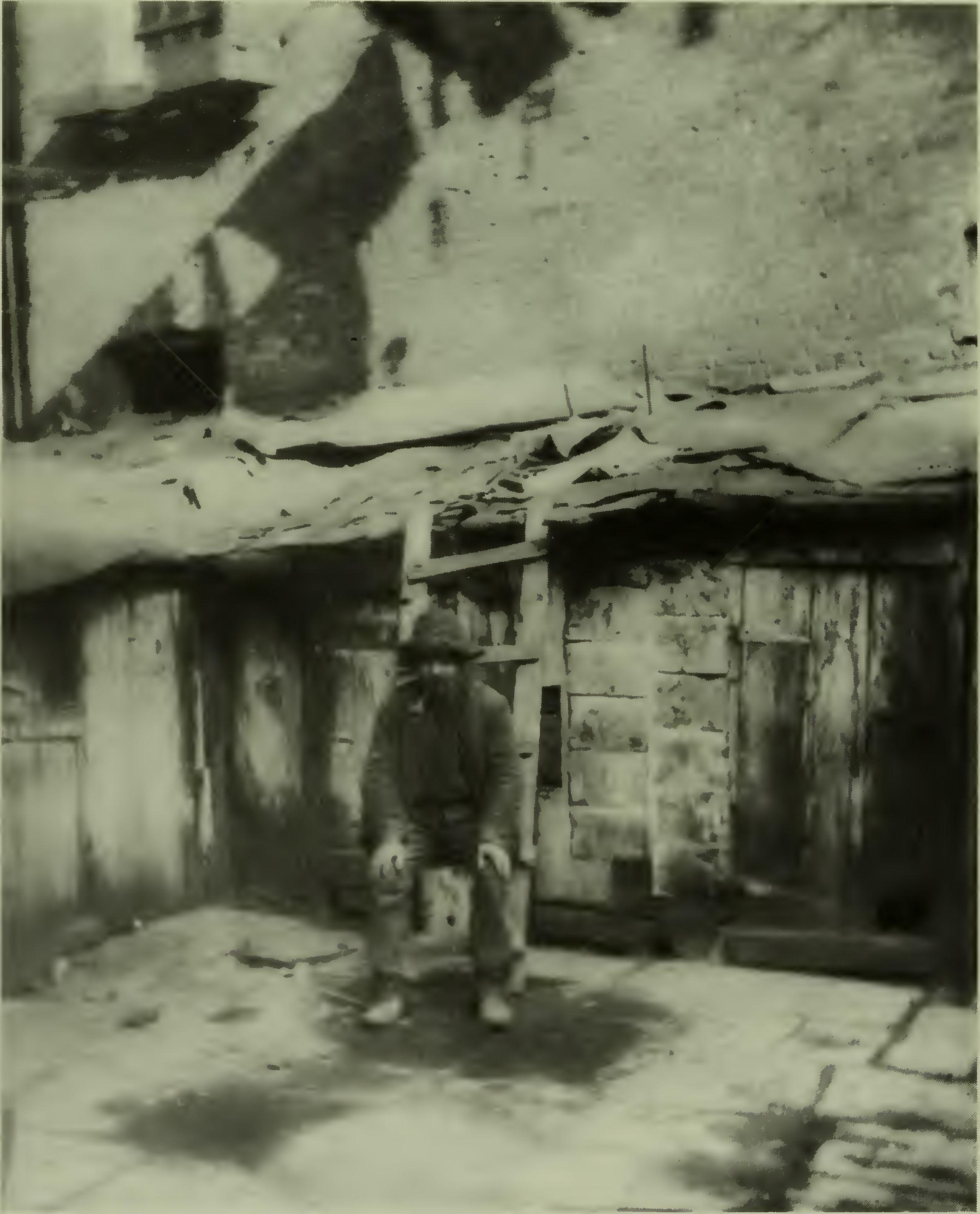

2.1. Jacob A. Riis, “The Tramp in a Mulberry Street Yard” (1887) 48

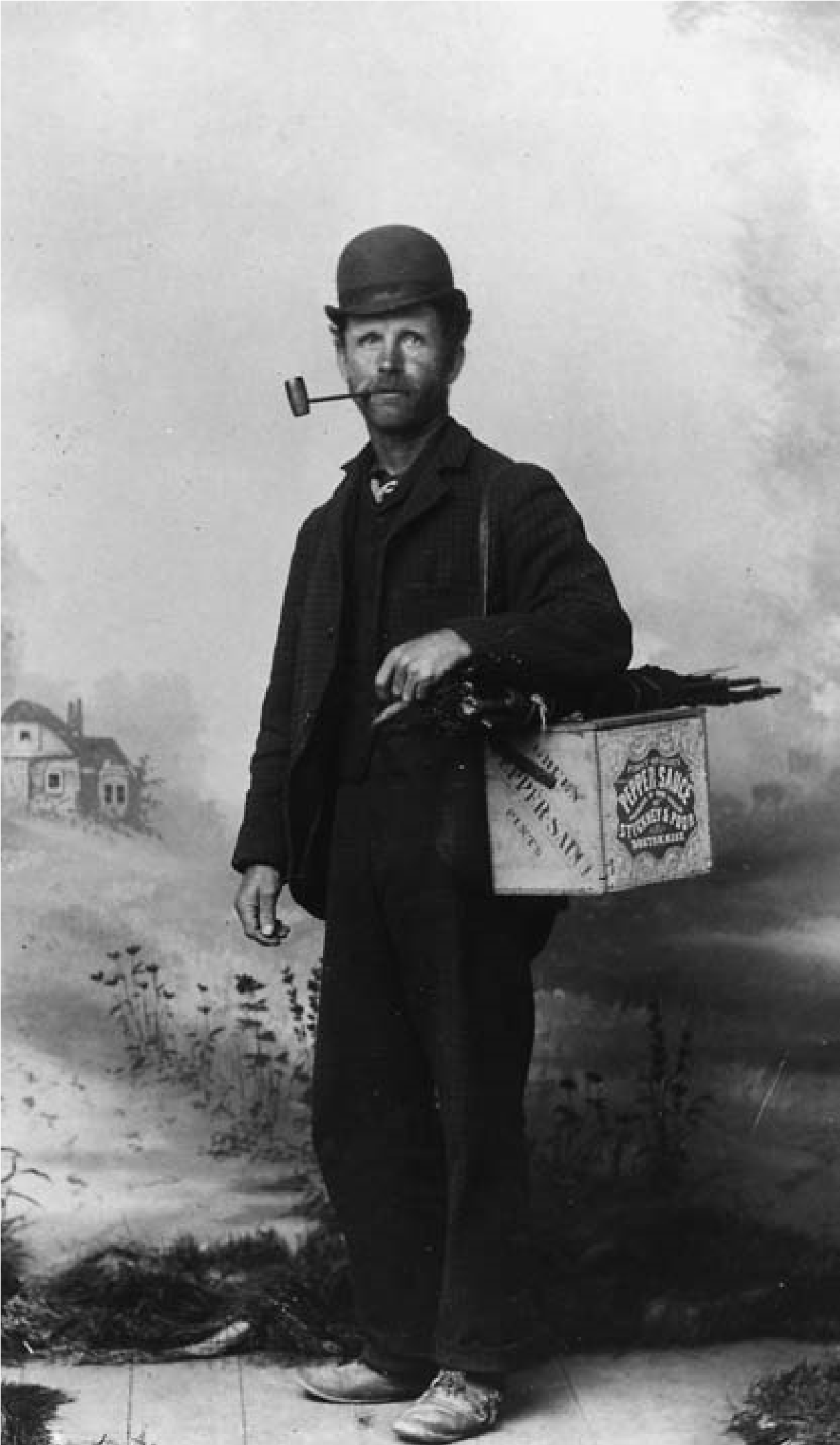

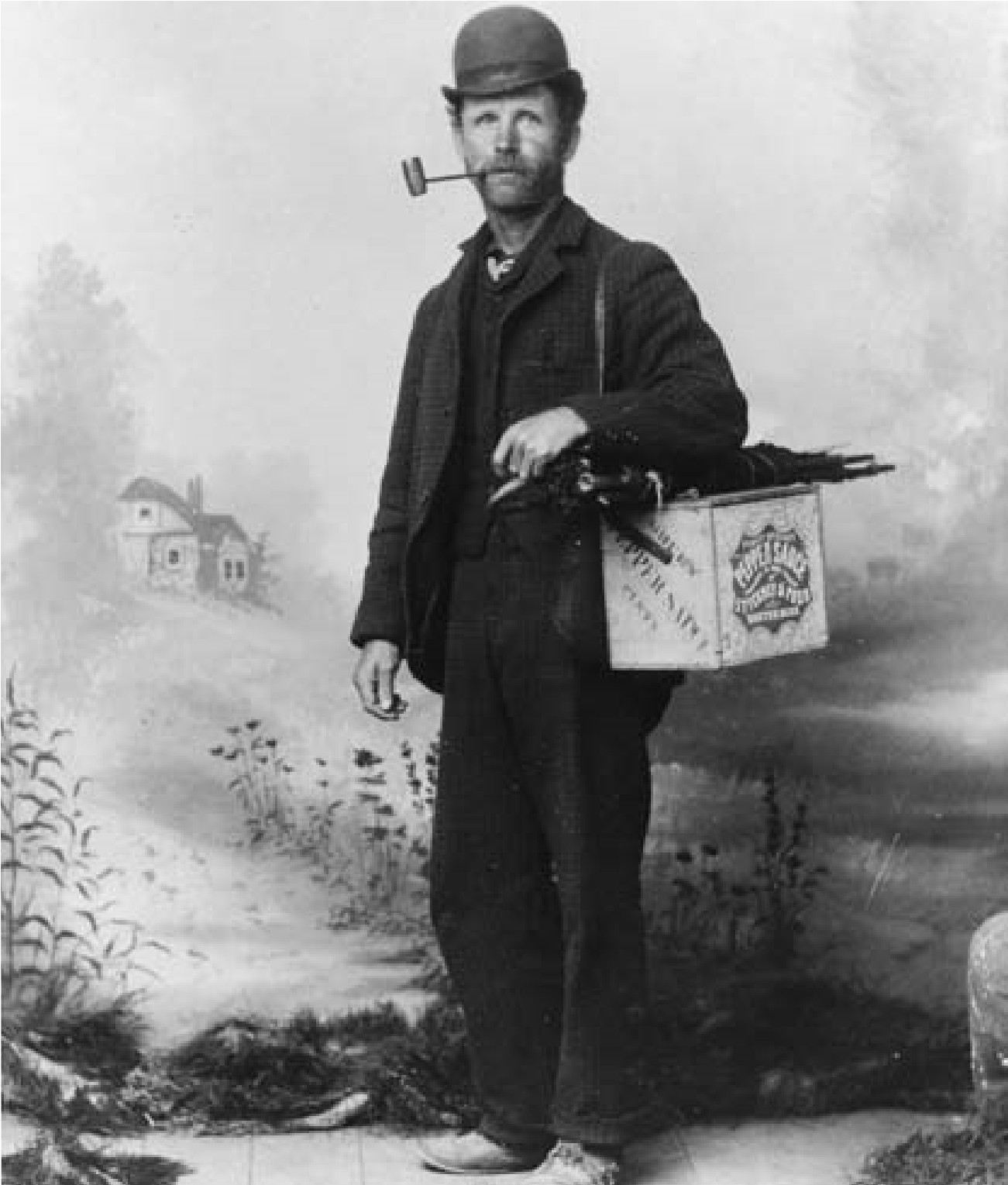

2.2. Portrait of William W. “Roving Bill” Aspinwall (1893) 55

3.1. “Providence Bob and Philadelphia Shorty Riding the Rods” (1894) 67

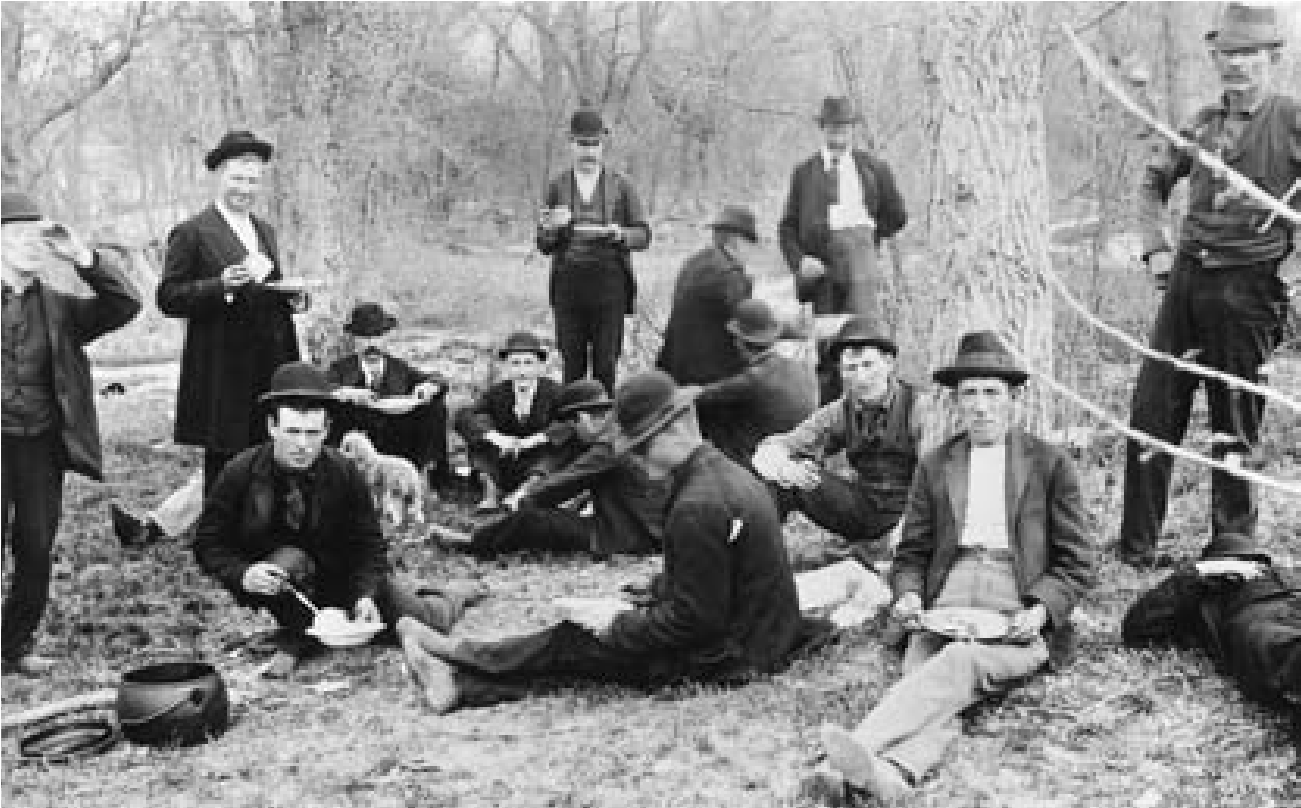

3.2. A hobo jungle picnic (1895) 71

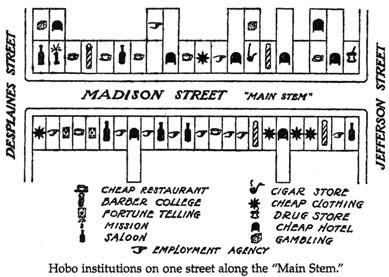

3.3. Map of West Madison Street (1923) 76

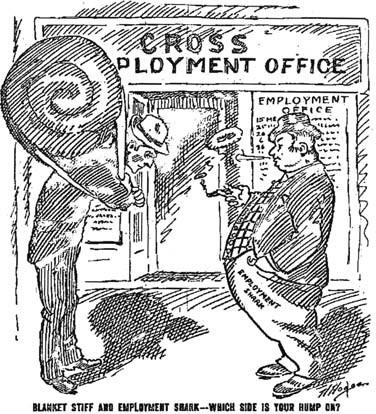

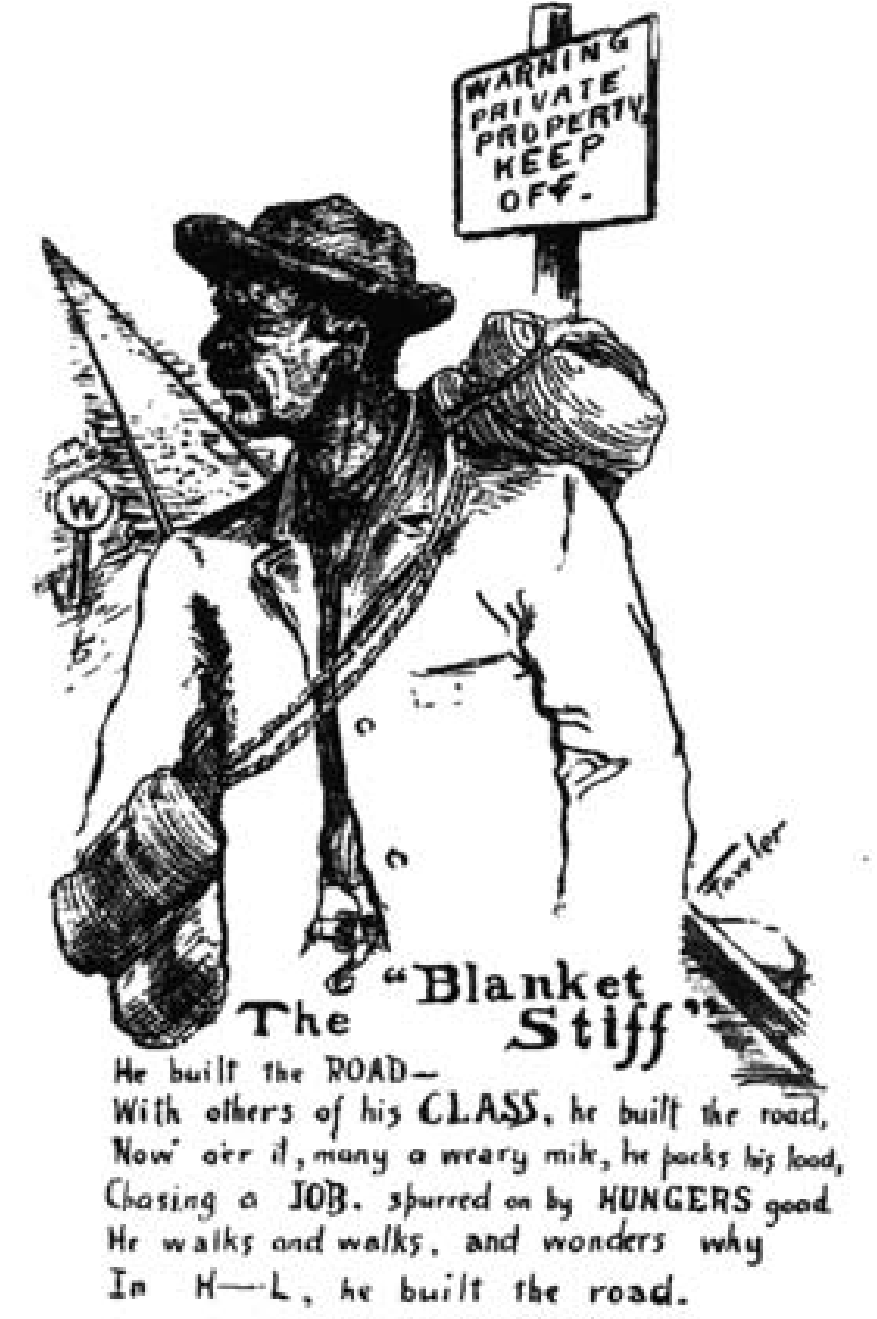

4.1. “Blanket Stiff and Employment Shark—Which Side IsYour Hump On?” Industrial Worker (June io, 1909) 103

4.2. “The ‘Blanket Stiff,’” Industrial Worker (April 23,1910) 109

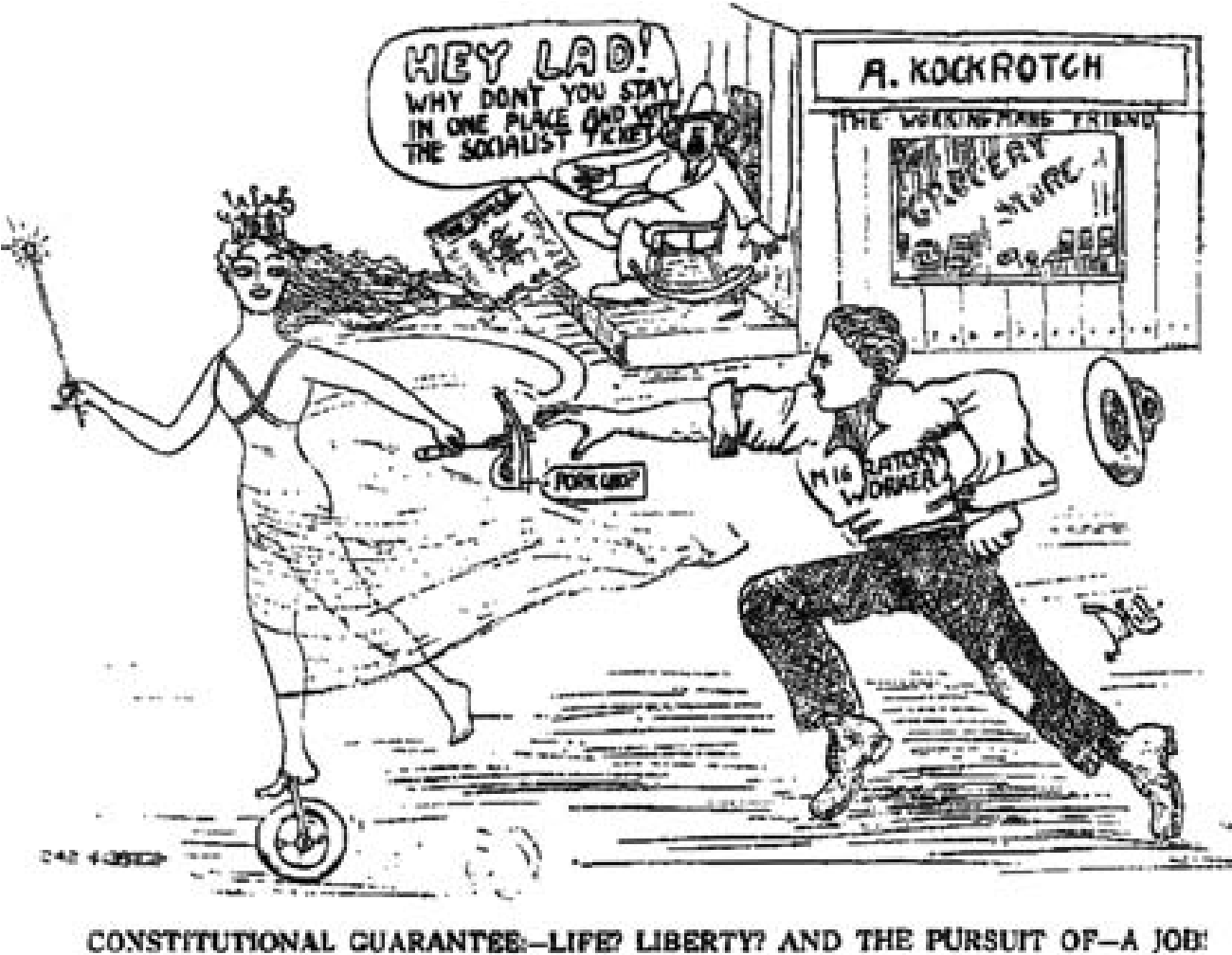

4.3. “Constitutional Guarantee:—Life? Liberty? And the Pursuit of—a Job!” Industrial Worker (April 24,1913) 116

4.4. “Now for the Eastern Invasion!” Solidarity (October 14,1916) 122

4.5. “Somebody Has Got to Get Out of the Way!” Solidarity (August 19,1916) 123

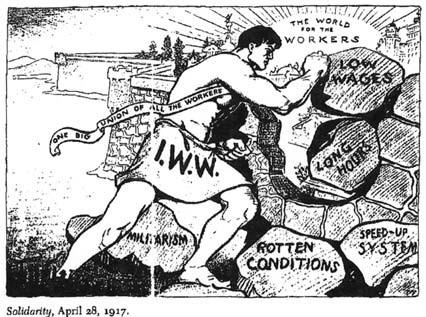

4.6. “One Big Union of All the Workers,” Solidarity (April 28,1917) 124

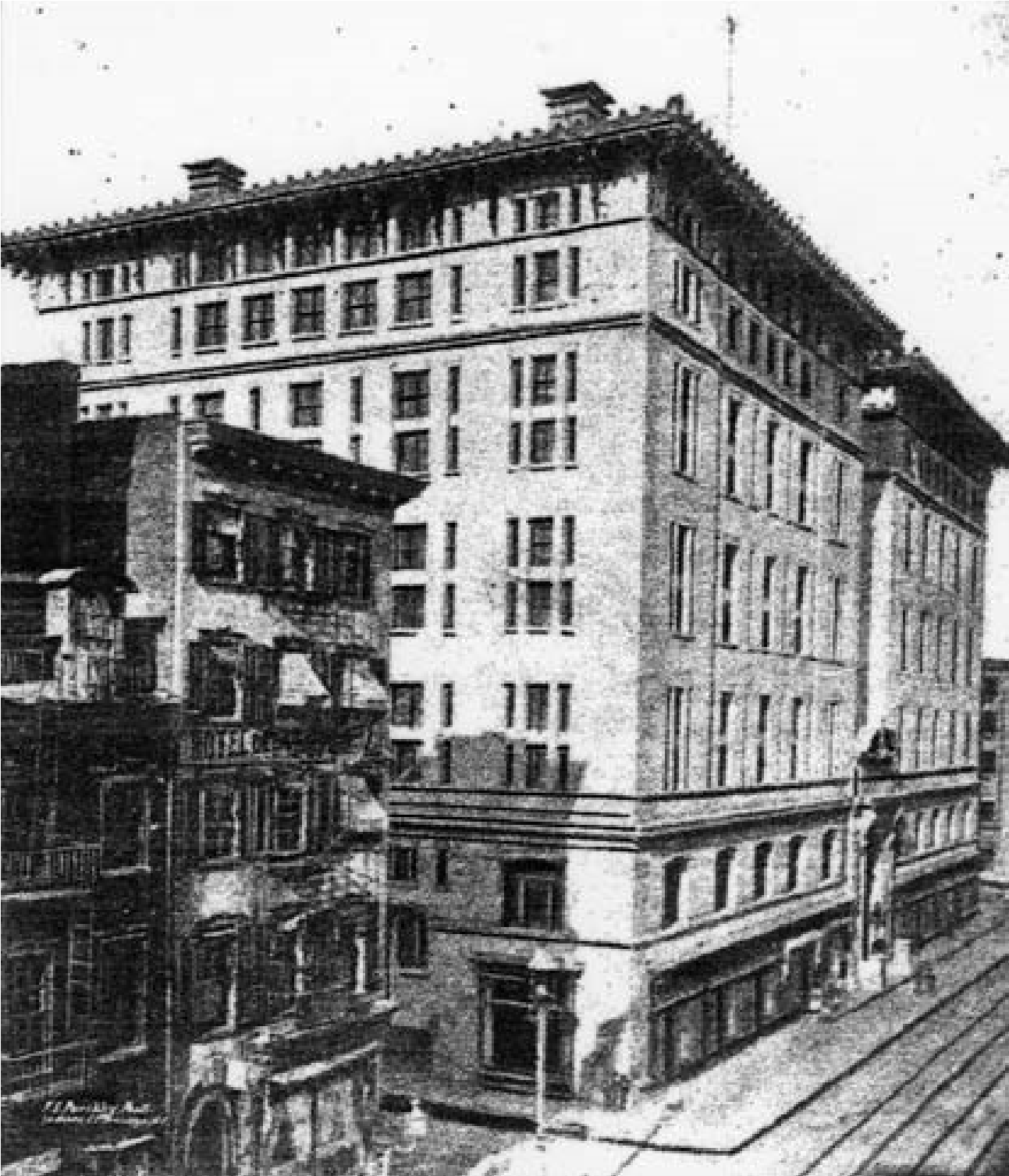

5.1. Mills Hotel (1899) 136

5.2. Waldorf-Astoria Hotel (ca. 1910) 141

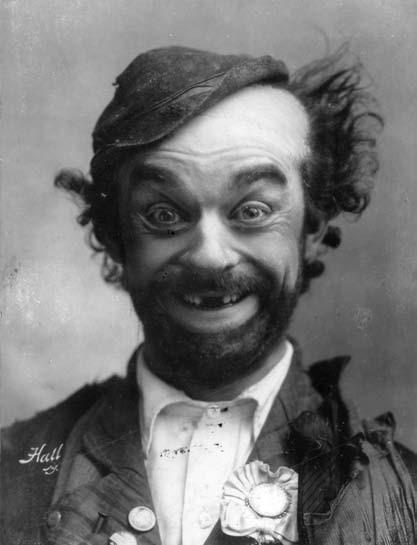

5.3. Portrait of Nat M. Wills, “the Happy Tramp” (1907) 155

5.4. Charlie Chaplin, film still from City Lights (1931) 165

5.5. Frederick Burr Opper, “Happy Hooligan” (1904) 166

6.1. Dorothea Lange, “Migrants, Family of Mexicans, on the Road with Tire Trouble” (1936) 180

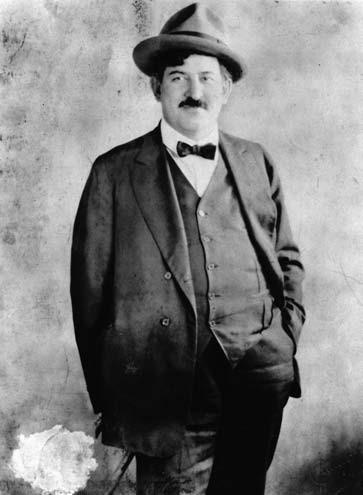

6.2. Portrait of Ben Reitman, the “Main Stem Dandy” (ca. 1919) 189

7.1. Bonus Marchers battling police (1932) 200

7.2. Wilifred J. Mead, “We Can Take It!” (ca. 1935) 207

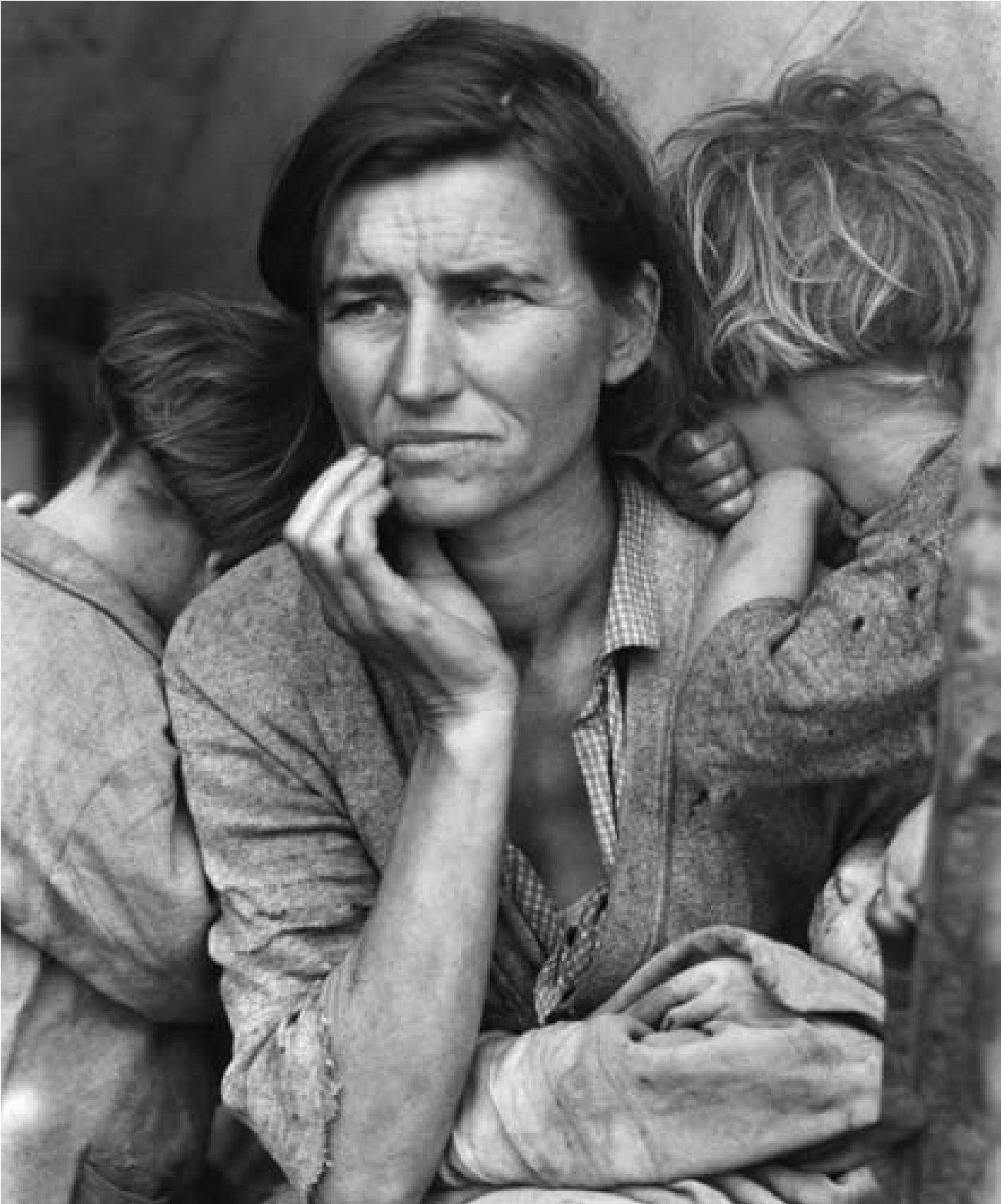

7.3. Dorothea Lange, “Migrant Mother” (1936) 217

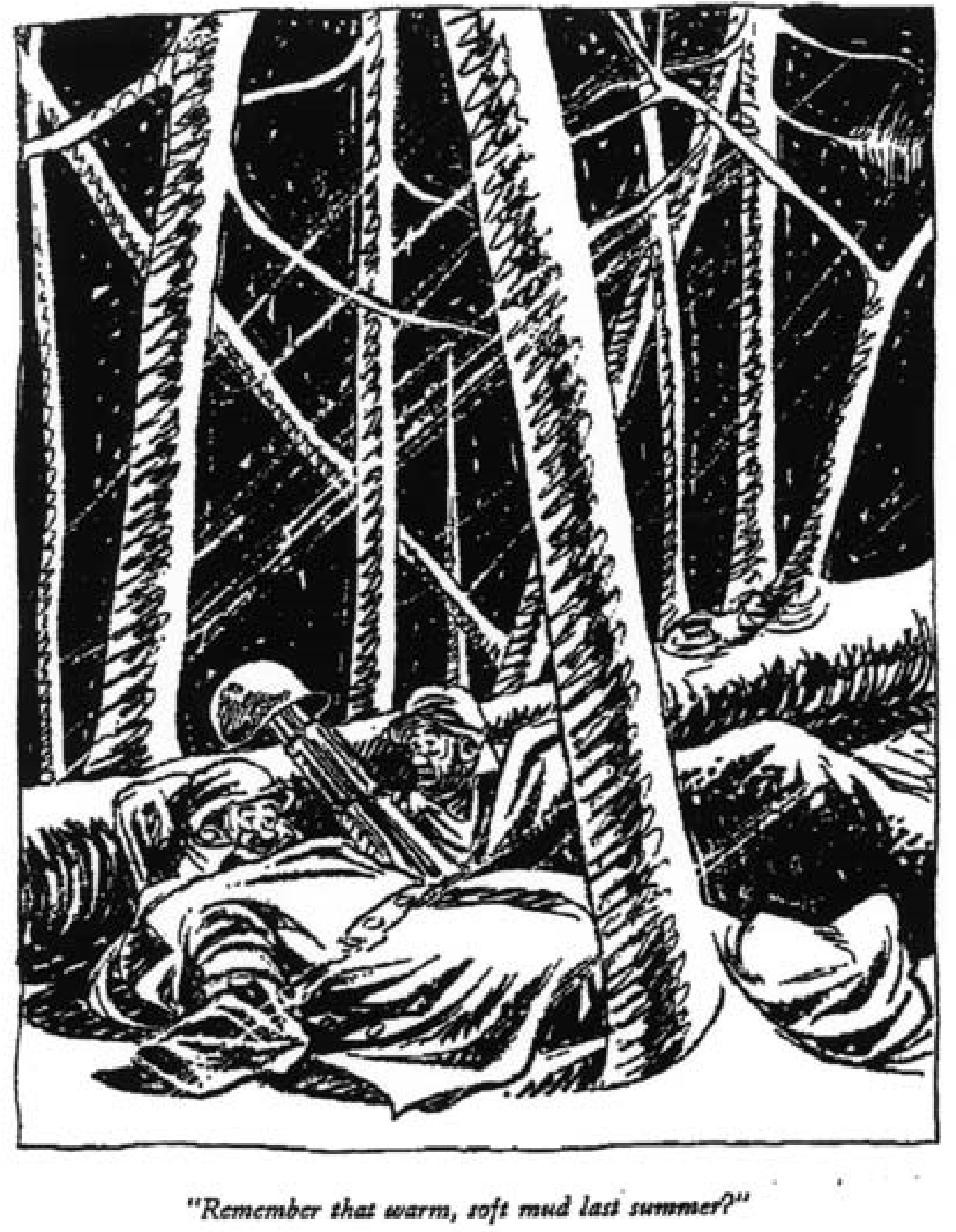

8.1. Bill Mauldin, “Remember that warm, soft mud last summer?” (1944) 222

8.2. Bill Mauldin, “How’s it feel to be a free man,Willie?” (1947) 225

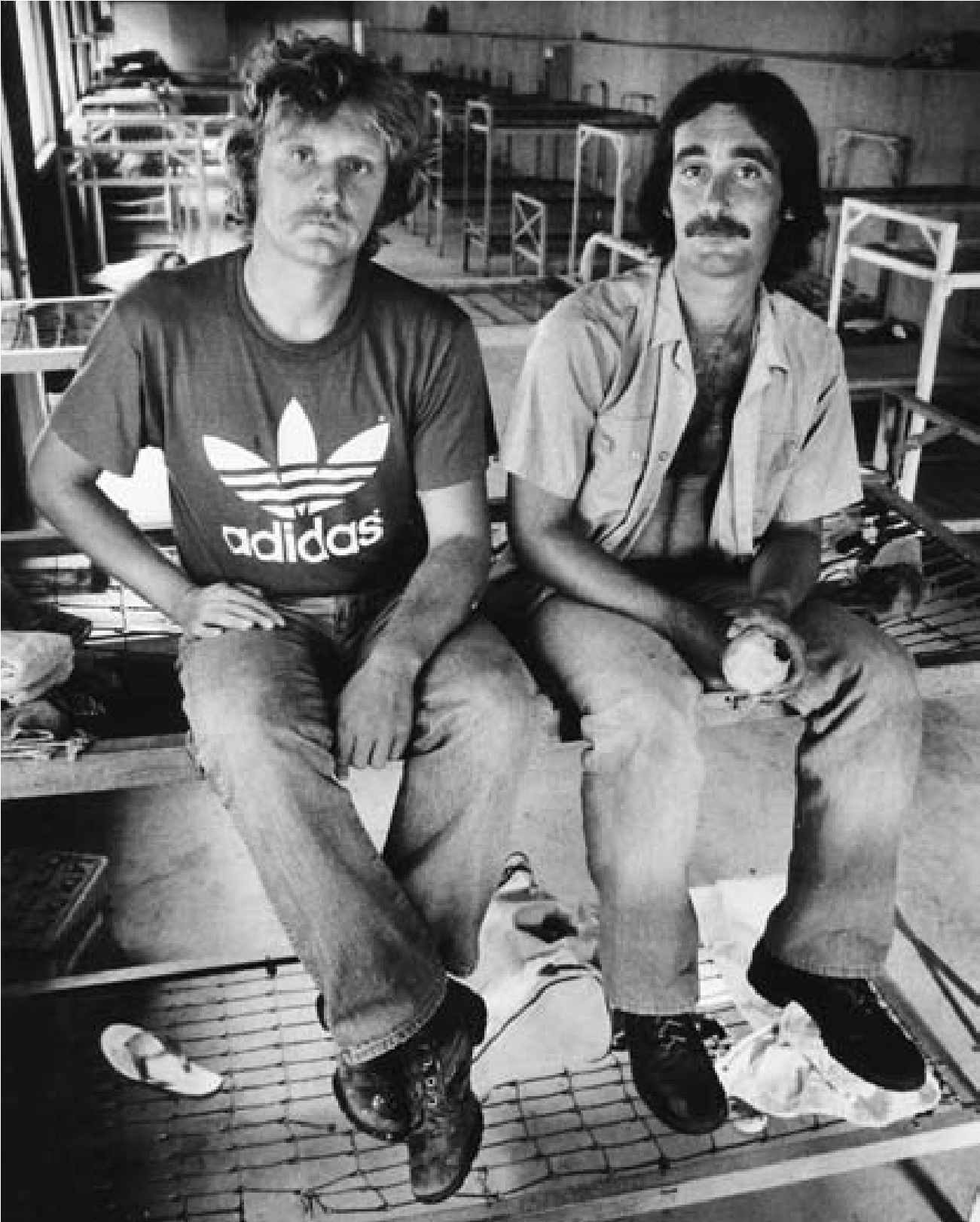

9.1. Mike Sienienkiewiczi and James Brown, Los Banos camp (1982) 250

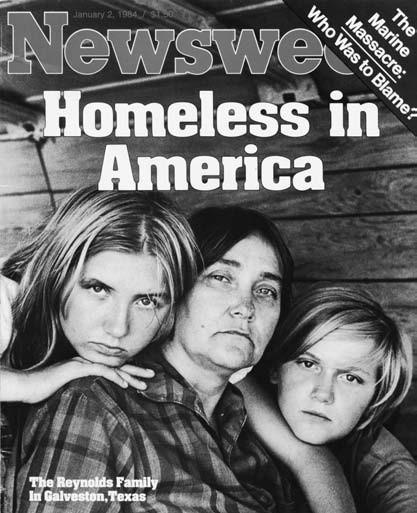

9.2. The Reynolds family, Newsweek (January 2, 1984) 260

Acknowledgments

This book was long in the making and would never have been possible without the help and support of many people. It is my privilege to thank some of them here.

This book began as a dissertation at Yale University, where, I am ashamed to say, I drew upon the expertise and kind offices of friends, colleagues, and professors in grossly unequal proportion to the amount I returned. From the moment I walked into his office, announced my dissertation topic, and asked him to advise it, Jean-Christophe Agnew has given indispensable direction, encouragement, and support through every step of my career. Offering guidance with his characteristic humor and insight, he has profoundly deepened my basic understanding of the historian’s craft. This book’s scholarly contribution is largely the result of Jean-Christophe’s constant but gentle prodding to get me to expand the scope of my argument and recognize the larger significance of my material.

I am also deeply grateful to David Brion Davis, whose high standards of scholarship, devotion to his students, and strong moral vision not only greatly improved this book, but also continue to inspire me as a scholar and teacher. Ann Fabian guided me out of the murkiness that characterized the early stages of this study, and also, incidentally, provided the wonderful company that helped make graduate study at Yale collegial and pleasurable. Like countless others who have come before me, I thank David Montgomery for sharing his invaluable advice and encyclopedic knowledge and for first inspiring my interest in working-class history. I appreciate his patience through my early missteps as much as I do his voluminous and painstaking commentary on every draft I sent his way. Finally, I must confess my long-standing debt to three scholars and teachers at Boston College—Paul Breines, Alan Lawson, and Mark O’Connor—who taught me about writing, history, and critical thinking long before this book was conceived.

So many friends and colleagues contributed to this book that I can only mention those who commented upon all or large parts of the manuscript. With his characteristic intellectual generosity and enthusiasm, James E. Mooney emboldened me to address larger themes. Robert Sherry not only read drafts and listened patiently as I tried to make sense of this topic, but also helped me to work through the strains of writing. His guidance has meant more to me than he could know. As a friend and confidant, Kevin Rozario read virtually every sentence—fragments and run-ons included— produced during this writing process, subjecting each to his exacting critical review. With his gentle humor, sharp wit, and humane approach to scholarship and life, Kevin has shaped this book in immeasurable ways. Lane Hall-Witt lent his truly rare intellect to early chapters, offering extensive and imaginative written commentaries that forced me to rethink and revise the very questions I was posing. Louis Warren provided many kinds of support and advice, not least of which was suggesting its very topic in the first place. Finally, my old friend Paul Allen Anderson devoted his prodigious intellectual, scholarly, and literary skills to a thorough critique of the entire manuscript that reoriented the study as a whole. I can only hope that the final product repays his efforts, if only in part.

At the University of Chicago Press, Doug Mitchell provided enthusiastic support and encouragement past many deadlines and over many hurdles. When I felt like the chips were down, Doug offered a stunningly erudite, and overly flattering, precis of the book that guided my final revisions. Two anonymous readers at the Press also contributed to these revisions, saving me from making several blunders, though perhaps not as many as they would have liked. On short notice, Douglas Harper generously extended his expertise, critical eye, and literary gifts to a thorough reading of the entire manuscript, contributing greatly to some final improvements. Robert Devens and Timothy McGovern supplied their own expertise as I prepared the final manuscript. No one read this work more closely than Erin DeWitt, who lived up to her billing as the best manuscript editor in the business.

In my search for sources, I have been assisted by the knowledge and energies of many persons. The reference librarians and archivists at Yale University, the University of Illinois at Chicago, the University of Pittsburgh, the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, the Chicago Historical Society, the State Historical Society of Iowa, the Library of Congress, the Rockefeller Archives Center (whereThomas Rosenbaum was particularly helpful), and the National Archives were indispensable. I would especially like to thank Pat Groeller, Polly Inge, and Carol Pistachio at Penn State Beaver for cheerfully putting up with my weekly stacks of arcane interlibrary loan requests. Marie Steenlage and George Horton of Iowa offered both their hospitality and access to their wonderful collections of tramp and hobo ephemera.

Financial support for research and writing came from many sources, including a John F. Enders Grant and an AndrewW. Mellon Fellowship at Yale University, an American Historical Association Albert J. Beveridge Award, a Rockefeller Archives Center Grant, and a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship and summer stipend. Parts of chapters 3 and 4 appeared in Community in the American West, a Halcyon imprint published by the Nevada Humanities Committee. I thank them for their permission to reprint.

Finally, no study of homelessness would be complete without acknowledging the manifold gifts of home. My parents, Allan and Bernice DePastino, shall always have my undying gratitude for the sacrifices they have made on my behalf, the love they have shown, and the example they have set. These and the many other gifts they have given will be a part of me always. My brother, Blake DePastino, offered insights and inspiration in his own inimitable style, forcing me to admit to myself, though never to him, that he is the better writer. Jennifer and Drew Haberberger have offered unflagging encouragement, support, love, and understanding throughout this project. Their daughters, my nieces Rosaleigh and Annabel, have enriched my life beyond anything I could ever have imagined.

This book is dedicated especially to the three persons with whom I most closely share my life. My wife, Stephanie Ross, has lived with this book far longer than was promised. She has supported and nourished this effort often to the detriment of her own work and dreams. Her love and respect have set a high standard for our marriage, and although I know my debt to her can never be repaid, I nonetheless hope that over our long life together I will find an appropriate way to say thank you. My daughters, Eleanor and Elizabeth, were not here when I started this study and were of not much help when I finished it. They read no drafts, provided no insights, and offered no support or encouragement. Indeed, apart from keeping up their nap schedules, Ellie and Libbie constantly distracted me and hampered my best efforts to keep my life focused on research and writing. For this, I thank them.

Introduction

“Warren,” she said, “he has come home to die: You needn’t be afraid he’ll leave you this time.”

“Home,” he mocked gently.

“Yes, what else but home?

It all depends on what you mean by home.

Of course he’s nothing to us, any more

Than was the hound that came a stranger to us Out of the woods, worn out upon the trail.”

“Home is the place where, when you have to go there, They have to take you in.”

“I should have called it

Something you somehow haven’t to deserve.”

—Robert Frost, “The Death of the Hired Man” (1914)

Perhaps no category of human experience exerts more ideological power than that of home. Fundamental and universal, home nonetheless defies simple definition, for it exists in memory and imagination as much as it does in brick and mortar. More than mere shelter or the means of social reproduction, home provides a well of identity and belonging, “a place in the world.” In exchange, home demands subordination to prescribed roles and routines, exercising a tyranny over its members and a vigilant defense against the encroachments of outsiders. A castle for some, a prison house for others, home structures and regulates human activity in ways that model and articulate the social relations governing the larger community. Societies riddled with persons deemed “homeless” are, by definition, societies in crisis.[1]

In 1914, when Robert Frost crafted his poetical meditation on the meaning of home, the United States was in the grip of such a crisis. Ever since the CivilWar, a veritable army of homeless men, predominantly white and native-born, had occupied the nation, growing virtually unabated year by year until it had become such a permanent fixture on the American landscape that few thought it could ever be resettled. For these men, commonly referred to as “tramps” and “hoboes,” homelessness was not so much a shelter condition, but a distinct way of life characterized by casual lodging, temporary labor, and frequent migration. As both products and agents of corporate capitalist expansion, hoboes pressed everywhere on the eyes and minds of a nation struggling to match nineteenth-century domestic ideals with the new realities of urban industrial life. Challenging home’s status as a central place of being and building block of social order, hoboes put their own ideals of “homelessness” on prominent display, especially as they gathered along the “main stem” of the industrial city. By the time Frost published his poem about the final journey and unwelcomed claims of a “Hired Man,” they had forged a swaggering counterculture known as “hobohemia” that defied, unsettled, and eventually transformed everything Americans meant by home.

Thus, while Frost’s poem offers a timeless allegory of a universal human alienation, it also captures a particular historical moment when white male homelessness cast such an ominous shadow over American nationhood and citizenship that it called into question the very status of home in a democratic polity. In the poem, a once-fractious and inconstant Hired Man appears at the door of his former employer in an exhausted and ailing condition. Having once flaunted, and now barely weathering, the hard freedoms afforded by the wage contract, the Hired Man triggers a crisis in the farmhouse, compelling the farmer and his wife to deliberate over the meaning of home, to negotiate its boundaries and define its rules of access and exclusion. Whereas the farmer’s definition emphasizes the social power, and hence the obligations, of the householder, his wife’s rejoinder focuses on the relative powerlessness, and hence the inalienable rights, of the dispossessed. All the while, the question of what constitutes a home remains open, as do the terms and conditions under which the Hired Man will be “taken in.” “It all depends,” as the farmer’s wife reminds her husband, “on what you mean by home.”

Citizen Hobo examines what Americans have meant by home—and, by extension, its absence—since modern homelessness first emerged in the late nineteenth century. It argues, in essence, that the specter of white male homelessness so haunted the American body politic between the end of the Civil War and the onset of the Cold War that it prompted the creation of an entirely new social order and political economy. Over these decades, the Hired Man took on many forms—the “tramp” of the Gilded Age, the “hobohemian” of the Progressive Era, the “transient” and “migrant” of the Great Depression, and the skid row “bum” of the postwar period—but each time he appeared at the threshold, he signaled a crisis of home that was always also one of nationhood and citizenship, race and gender. Each crisis, in turn, reinvigorated efforts to resettle the hobo army and reintegrate the white male “floater” back into the American polity. By the middle of the twentieth century, these efforts had yielded not only in the welfare state and corporate liberal economy, but also in the modern American home itself, with all it entails for class formation, gender order, and racial identity.

As this argument suggests, Citizen Hobo is not a comprehensive history of American homelessness. Neither does it offer a sustained structural analysis, nor even an exhaustive ethnography of hobo subculture, although both the structural and ethnographic approaches form key components of the study. Rather, this book traces the history of homelessness as a category of culture as well as economy, focusing especially on how its racialized and gendered meanings shaped the entitlements and exclusions of “social citizenship” in modern America.[2]

In so doing, it draws upon a rich body of previous scholarship in the history of race, poverty, gender, sexuality, social welfare, migratory labor, and urban culture. Indeed, the subject of American homelessness brings together a great many discrete historiographies, from the social and institutional histories of tramping and poor relief to the now-crowded fields of “whiteness studies” and gender and social policy. While social, urban, and public policy historians have documented the changing experiences, social composition, institutional contexts, and physical spaces of homelessness, feminist and political scholars have demonstrated the racialized and gendered dimensions of social citizenship, as well as the ways in which social policy constitutes racial, gender, and class difference.[3] These studies have supplied the departure points for my own investigation, one that explores how culturally defined crises of homelessness have both reflected and shaped larger changes in the political economy and culture of America since the late nineteenth century.

The first step of such an investigation is to narrate the rise, fall, and indelible legacy of hobohemia, plotting the boundaries, recapturing the culture, and analyzing the politics of a way of life largely forgotten by historians and obscured by contemporary assumptions and concerns. As part of the larger homeless world to which the Hired Man belonged, hobohemia constituted a distinct white male counterculture with its own rules of membership, codes of behavior, and notions of the good life. Rejecting the range of manners, morals, and habits associated with middleclass domesticity, hobohemia fostered a powerful sense of collective identity among its members, an identity reinforced by the numerous advocacy groups that arose to promote hoboes’ interests. By World War I, virtually every main stem in America hosted a local of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) or some other formal organization intent on mobilizing the subculture for the larger purposes of social change. Through their pamphlets, newspapers, and songbooks, these organizations also disseminated a powerful set of hobo myths that enhanced group definition and celebrated hobohemia as a revolutionary vanguard.

But while the IWW touted migratory homeless men as the “real proletarians,” hoboes almost always defined their world in terms not only of class, but also of race, ethnicity, gender, and region. Jealously guarding the road as the preserve of white men, hoboes also, from time to time, staked compelling claims to the polity on the basis of white male privilege. These claims carried particular weight when registered in the form of a disenfranchised hobo “army,” a figure that evoked not only the size, sway, mobility, militancy, and camaraderie of the subculture, but also the spectacle of an aggrieved “National Manhood.”These armies occupied real spaces— not just discursive ones—most conspicuously when rail-riding protesters in old military garb swept down on the nation’s capital to dramatize the burdens they had borne for the state and to demand the compensating entitlements. The Industrial Armies of 1894 and the Bonus Army of 1932 proved particularly effective in offering up powerful models of nationhood, as well as working-class white manhood, during times of severe economic crisis. Coupled with the everyday claims that hoboes made on railroads, employers, householders, local officials, and urban space itself, these protests suggested to many Americans that the “imagined fraternity of white men” that had historically constituted American nationhood needed to be domesticated.[4] On the road too long and enchanted by its romance of perfect freedom and brotherhood, the hobo had to be “taken in,” reminded of his “paternalist” duties, and resettled as a family breadwinner.

In tracing the various campaigns to recover and resettle the homeless man, this book examines the diverse and conflicted meanings that hobohemia held for Americans, from the investigators who first charted the problem of homelessness to the poets, performers, songwriters, filmmakers, labor organizers, and various other commentators who saw both perils and possibilities in the hobo life. Of special consequence, of course, was the attention that hobohemia attracted from politicians, policy makers, businesspersons, and reformers of all stripes. Over time and through a sweeping series of interventions in labor, housing, and transportation markets, these activists eventually managed to dismantle hobohemia and demobilize the roving army of hobo labor. Through their struggle with a population they deemed homeless, they created, in effect, the modern American home, redistributing its benefits as well as its burdens.

When homelessness first emerged as a widespread social problem after the Civil War, most Americans still clung to patriarchal ideals of home as productive property, a shop or farm that harbored the labor of dependent families and granted its owner the full privileges of citizenship. By the turn of the twentieth century, these old ideals had succumbed to the new realities of industrial wage earning, which stripped home of its central economic purpose and its civic status. Amidst Progressive and New Era experiments with “welfare capitalism” and working-class housing arose a new vision of suburban homeownership, a vision that emphasized the aesthetic and spiritual values of rootedness, place, and familial belonging.

While this vision effectively recast the problem of homelessness in the modern terms of alienation and estrangement, it was not until the New Deal of the 1930s when mass suburban homeownership became an explicitly political goal, a way of restoring the bonds of community and nationhood during a time of unparalleled homelessness. After World War II, when the discharge of millions of soldiers and sailors once again threatened to unleash a homeless army upon the nation, this political goal was finally achieved. With the help of the GI Bill, the suburban home became the centerpiece of a new corporate liberal order that promoted masculine breadwinning, feminine child rearing, and the steady consumption of durable goods within the context of the nuclear family. By extending the family-wage pact and the suburban ideal of single-family homeownership to a broad segment of the white working class, the corporate liberal state effectively solved the modern problem of homelessness and infused the home with new meanings for democratic citizenship.

As a solution to the vexing problem of white male homelessness, the “postwar settlement” redefined the privileges of whiteness by failing to extend the full social benefits of citizenship to those who had historically been barred from hobohemia. This failure ensured that when the corporate liberal order faltered in the 1970s, a new homeless army would arise bearing the marks not of white manhood, but of a feminized and racialized “underclass.”

Cast adrift by the very political economy of home that recovered the Hired Man, the so-called “new homeless” have once again fractured our unified domestic visions and triggered a new round of debate over what we mean by home. The homeless men, women, and children of postmodern America also bear witness to the unresolved issues of nationhood and citizenship that struggles over home have historically entailed. Almost one hundred years after “The Death of the Hired Man,” we find ourselves asking the same questions posed by Frost’s farm couple: What are the rules governing access to and exclusion from settled society? How are the dispossessed and disenfranchised to be “taken in” as full members of the polity and economy? Is home truly “something you somehow haven’t to deserve,” or is it a privilege reserved for the worthy? Although, as a work of history, this book cannot presume to answer these questions in any definitive or programmatic way, it can provide a new context for thinking through the vexing problems of poverty, inequality, and alienation. Like the proverbial traveler who arrives where she started and knows that place for the first time, we explore what we mean by homelessness in order to understand better the rules, privileges, and exclusions by which we claim our homes.

Because this book tells a story, it proceeds in chronological order with each chapter highlighting a particular event or turning point in the history of modern American homelessness. To signpost the overarching narrative, the chapters are organized into four parts that together chart the rise and decline of hobohemia and track its legacy down to the present day. In addition to plotting change over time, this book also analyzes in depth key topics and themes—especially those relating to race, ethnicity, class, gender, sexuality, nationhood, and citizenship—that emerged and accumulated during each stage of the long crisis.

Chapter i traces the roots of the crisis to the depressions of the Gilded Age, when a “great army of tramps”—departing dramatically in size, scope, and composition from previous generations of vagrants and vagabonds—let loose upon the land, conjuring up widespread fears of gender disorder, class warfare, and a masculine regression to “savagery.” Chapter 2 turns to working-class observers and victims of the crisis who, like Walt Whitman, often idealized the “Open Road,” but also valued “home” as the property necessary for free, independent “manhood.”

Opening with an analysis of the Industrial Army movement’s unprecedented March on Washington in 1894, chapter 3 tracks the emergence of hobo subculture, including its peculiar sexual code, through the bunkhouses, boxcars, “jungle” camps, and main stems of the western “wageworkers’ frontier.” Chapter 4 then examines how the IWW and other radicals infused hobohemia with new political meanings, crafting an enduring canon of hobo folklore that drew upon frontier romances of virile white manhood.

From the romances of the open road, chapter 5 turns to the mysteries of the great city, exploring how, in the context of Progressive efforts to reform the main stem, the “tramp crisis” became known as the “problem of homelessness.” The new language figuratively linked the hobo to the larger urban “hotel spirit,” which, reformers argued, bureaucratized and commodified “home,” reducing it to the functions of “housing.”While the “hotel spirit” received a ringing endorsement from the likes of Upton Sinclair, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and the outrageously popular comic tramps of vaudeville, a coalition of activists worked to dismantle “hotel civilization” and reengineer the American home in the suburbs.

While housing activists advanced new suburban ideals as antidotes to a broadly defined moral crisis of homelessness, employers and industrial relations experts after World War I, as chapter 6 demonstrates, worked to curtail hobohemia through long-term changes in the migratory labor market and the political economy of unemployment. As hobohemia slipped into the past, a cultural struggle over its memory pitted radicals like John Dos Passos on the Left against popular folklorists on the Right. These debates not only reflected the realities of New Era capitalism, but also shaped popular and official responses to the mass homelessness of the 1930s, a decade haunted by the specter of hobohemia.

This specter acquired flesh and blood in 1932, when, as chapter 7 argues, the Bonus Army’s March on Washington sparked a new crisis of nationhood that eventually prompted President Franklin Roosevelt to make the recovery of the “Forgotten Man” the priority of his New Deal. In response to stinging criticism that FDR’s various “armies” of recovery merely replicated the fraternalist camp camaraderie of hobohemia, the second New Deal shifted its emphasis to bolstering men’s breadwinning roles. While the hobo endured as a populist folk figure, he competed with diverse new folklores of homelessness featuring those never counted among the Forgotten Men, namely, women and nonwhites.

The Forgotten Man’s recovery became complete only after World War II, when, as chapter 8 explains, returning veterans took to the suburbs rather than the streets. Meanwhile, blighted skid row districts served as embarrassing reminders of past grievances as well as living laboratories for the study of “disaffiliation,” the diagnosis given to those single white men who stubbornly refused their entitlements to breadwinning and homeowning. While the postwar Beat counterculture tried to revive the spirit of the old main stem, the road took on very different meanings with the countercultural upheavals of the late 1960s, by which time most skid row districts had met the wrecking ball.

Chapter 9 traces the emergence and persistence of a new homelessness crisis during the 1980s and 1990s, when a population largely bereft of the romance, the housing, and the racial and gender privileges of its hobo forebearers appeared on the streets. Betokening a renewed cultural crisis of “home,” as well as an economic crisis of shelter, the “new homeless” fell victim to the same racialized and gendered politics of the nuclear family imperative that had recovered the hobo. Like their predecessors, however, America’s homeless continue to forge their own communities and chafe against family breadwinning ideals. Imprecise and ideologically loaded as it is, the category of homelessness persists not only as the most visible symptom of larger racial, class, and gender inequalities, but also as an immanent frame of reference for their analysis.

A final word on terminology is in order, especially for those readers who are already frustrated with the imprecise and shifting use of the word “homelessness” in this book. As the ironizing quotation marks suggest, “homelessness” is a term whose meaning depends entirely on the specific historical conditions of its use. It has therefore denoted different things to different people at different times. Sometimes its meaning is quite narrow, as in contemporary references to shelterlessness. At other times, the term has signified the dispossession of particular kinds of property, the estrangement of men from the feminine realm of nurture, or the condition of alienation associated with the rise of modernity. The following chapters will signpost these shifts in meaning, paying careful attention to the larger claims implied by the term’s use.

While “homelessness” serves as a rich and useful metaphor and a wonderful heuristic device for charting larger changes in ideology and social structure over the twentieth century, it works very poorly as an objective measure of poverty and inequality. Despite the arresting sight of a family waiting for shelter or persons sleeping on a steam grate or huddled under a bridge, those we call homeless differ very little, if at all, from the laboring poor in general. As a symptom of poverty, the dramatic loss of home is rarely permanent, and the resort to the streets largely episodic. In their effort to gain a margin of social power and define the terms of their own situations, the dislocated stake new claims to space and place, squatting, resettling, and otherwise improvising new homes in alien environments. While prevailing notions of home often cast these domestic improvisations as “homelessness,” such struggles really concern the normative conditions, meanings, and forms of “home” themselves. One of the goals of this study is to examine our own habitual uses of these keywords, to recover the unacknowledged assumptions, fears, and desires buried within our seemingly objective concepts and definitions. This is not to say that such public encounters with the dispossessed should not prompt concern, outrage, or action on our part. Like the Hired Man at the door, the visible presence of homelessness reminds even those of us who are comfortably housed that no home is purely private and no place in the world is always guaranteed.

Part I: The Rise of Hobohemia, 1870 — 1920

1. “The Great Army of Tramps”

Long before he became famous as a pioneering photojournalist and slum reformer, Jacob Riis was a tramp. Riis first arrived to America in the spring of 1870, a twenty-one-year-old Danish immigrant with empty pockets but great ambition. For the next three and a half years, Riis walked and rode over thirty-five hundred miles in search of work, traveling back and forth between the metropolitan areas of New York, Buffalo, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and Chicago. While on the move, Riis improvised shelter—“rarely the same for two nights together”— stealing sleep in hay wagons, sheds, barns, open fields, and graveyards (because “brownstone keeps warm long after the sun has set”). While in the city, Riis lodged day-to-day when he could, taking to doorways, parks, and, in at least two instances, police station lodging when money ran out. For food, Riis scavenged and begged, searching out “windfall apples,” knocking on back doors, and even, on occasion, hunting rabbits and squirrels, in order to eat the meat and sell the pelts. Of course, Riis also sold his labor. By the time he launched his career as a Bowery beat reporter, Riis had worked as a carpenter, coal miner, farmhand, railroad tracklayer, dockworker, steamship sailor, sawmill hand, factory operative, drummer, peddler, brick maker, telegrapher, and house servant. Not one of his jobs lasted for more than six weeks; most lasted for only a few days. “The love of change belongs to youth,” Riis explains in his autobiography, “and I meant to take a hand in things as they came along.”[5]

Whether from the love of change or the pinch of hunger, Jacob Riis had joined a growing body of young male workers who, in the years following the CivilWar, traveled far and often in search of wage labor. In 1870, when Riis entered this migratory labor stream, most Americans were unaware of what Riis called “the great army of tramps” flocking to American highways. It would take a Wall Street crash in September 1873 and five subsequent years of bankruptcies, wage cuts, layoffs, strikes, and mass unemployment—the first international “great depression”—to thrust the tramp army to the fore of public consciousness. With thousands, perhaps millions, on the road, newspaper editors, charity workers, and government officials across the nation asked the question “What shall we do with our tramps?”[6] “There is perhaps no problem in social science that is just now more pressing,” declared the NewYorT Times in 1875, “than what to do with the great and increasing army of mendicants who ... from their mode of life, have gained the name of ‘tramp.’”[7]

In responding to this problem, America’s opinion and policy makers were not generous. Rather than offer charity, they called for mass arrests, workhouses, and chain gangs. Some advocated more creative solutions. On July 12, 1877, the Chicago Tribune advised “putting a little strychnine or arsenic in the meat and other supplies furnished to tramps” as “a warning to other tramps to keep out of the neighborhood.”[8] Another paper proposed flooding poorhouses with six feet of water so that tramps would “be compelled to bail” or drown.[9] Justifying such extreme measures was the dean of Yale Law School, FrancisWayland, who delivered a widely circulated paper on tramps before the American Social Science Association in September 1877. “As we utter the word Tramp,” Wayland declared at the outset of his address, “there arises straightway before us the spectacle of a lazy, shiftless, sauntering or swaggering, ill-conditioned, irreclaimable, incorrigible, cowardly, utterly depraved savage.”[10]

Although revealing little about actual tramps themselves, such expressions of fear and loathing tell us much about middle-class perceptions of crisis in the Gilded Age. Tramps stood at the center of a swirling vortex of concerns about the new corporate industrial order coming into being after the CivilWar. Americans in these years saw the rise of large-scale manufacturing and mass production, the spread of railroads and continental markets, and the creation of strict workplace hierarchies based on a universal system of wage labor. As the pace of industrialization quickened and economic power became concentrated in fewer hands, pitched battles erupted between capital and labor over not only the fruits of production, but the very destiny of industrial civilization itself. Tramps were both victims and agents of the new economic system, itinerant laborers clinging beneath the speeding freight train of industrial capitalist expansion. Because they seemed strange and placeless—“here to-day and gone tomorrow”—tramps served as convenient screens onto which middle-class Americans projected their insecurities, anxieties, and fantasies about urban industrial life.[11]

Tramps, of course, wrestled with their own insecurities, though middleclass descriptions of tramp life hardly mentioned them. Tramping was an expression of the new social and economic relationships coming to dominate American life in the Gilded Age. Increasingly dependent upon wages and decreasingly secure in their jobs, working people the nation over faced the threat of poverty, dislocation, and the shattering of their customary patterns of life. In the face of these changes, some workers took to the road and, in so doing, collectively gave rise to a new modern problem of homelessness that would command the attention of private and public officials for generations to come.

Because the alarm raised by the tramp crisis of the 1870s reverberated halfway into the twentieth century, charting the emergence of this first tramp army is crucial to understanding the subsequent history of American homelessness. What exactly was new about the great army of tramps? How did Gilded Age tramps differ from previous generations of homeless vagrants? Where and how did they travel? Why did some poor Americans hit the road while others stayed put? And how did tramps get by once they found themselves, as Jacob Riis did, “on the tow-path looking for a job”?[12]

As for the larger culture, what was its response to this new tramp army? How did middle-class observers explain its rather sudden appearance? What logic, conscious or not, governed middle-class nightmares about “savage” tramps? And why did the tramp crisis become such a flashpoint in the larger struggle over the destiny and meaning of the new industrial America?

The Making of America’s Tramp Army

In what one commentator called “a happy innovation of language,” Americans in 1873 coined the word “tramp” to describe the legion of men traveling the nation “with no visible means of support.”[13] Previously, the noun had denoted “an invigorating walking expedition” or, during the CivilWar, “a long, tiring, or toilsome walk or march.”[14] Stressing mobility, the new usage also signified a sense of novelty, as if older terms such as “vagrant” or “vagabond” were somehow inappropriate to the moment.

But despite the innovation of language, neither homeless migration nor the fearful responses to it were new to American life in the Gilded Age. Long before the tramp crisis of the 1870s, poor men and women traveled in search of work and relief, often encountering fear and hostility instead. Indeed, court records from the earliest English settlements in America abound with references to the “strolling” or “wandering” poor. Seventeenth century English colonists had left a country that itself was awash with “vagabonds” and “masterless men”: displaced laborers drifting in and out of urban centers. A flourishing literature of “roguery” that purported to catalog the various deceits and depredations of these wayfarers kept the sense of crisis alive, while new draconian penalties for vagabondage— whipping, branding, and hanging among them—set the standard for cruelty. The problem was so urgent that propagandists for colonization such as Richard Hakluyt even urged the establishment of English settlements in America in order to relieve the mother country of its vagrant and “surplus” population. British America, in a sense, was founded as a refuge from, and solution to, the homelessness crisis of Tudor and Stuart England.[15]

A highly mobile people themselves, seventeenth- and eighteenthcentury Americans harbored the Old World’s suspicions of wandering strangers and took vigorous measures to suppress the transient poor. “Masterlessness” remained a major problem in the New World as the vagabond population swelled with escaped slaves, runaway servants and apprentices, and a host of others recently released from bondage. Those with skills or money usually gained residency or “settlement” when they moved to a new town, while indigent migrants were often “warned out” and physically removed beyond town limits. Settlement laws, which remained in effect until well into the twentieth century, protected towns not only from the responsibilities of poor relief, but also from the exotic and unwanted cultural influences that often accompanied wandering strangers. The tightly regulated towns of colonial New England, for example, frequently banned newcomers who carried religious convictions, political ideas, or moral standards that departed from community norms. Transients judged to be particularly dangerous, in either the criminal or cultural senses, could be deemed “vagabonds” and subjected to the grisly punishments customary in England. Pillorying, branding, flogging, or ear cropping often awaited those migrants who could not give “a good and satisfactory account of their wandering up and down.”[16] Like the laws of settlement, vagrancy statutes legitimized and facilitated the mobility of better-off transients while discouraging and criminalizing the movement of the poor.

These laws, strict as they were, proved ineffective in the face of the market and transportation revolutions of the 1820s and 1830s, which unleashed new streams of poor migrants throughout the country. Some of these migrants sought the new employment opportunities afforded by the Jacksonian economy. Young single men poured into and out of such inland boomtowns as Rochester, New York, for example, finding seasonal work along the Erie Canal. These unattached and highly mobile workers

made up 71 percent of Rochester’s adult male workforce, filling the city’s burgeoning workshops, boardinghouses, barrooms, and streets. The rowdy subculture they created alarmed Rochester’s more stable middleclass residents. Caught up in the religious revivals of the Second Great Awakening, reform-minded citizens launched temperance crusades and other organizations to impose moral order on this floating army of workers.[17]

While the commercial revolution set new groups of migrants in pursuit of opportunity, it also dislocated those farmers and artisans bankrupted by the new wildly competitive economy. Rural families scrambling for cash to pay rents, debts, or taxes swarmed into urban centers such as Philadelphia and New York on the promise of wage labor. Testifying to the frequent failure of these cities to make good on that promise was a newly refurbished urban institution: the almshouse. No longer able merely to “pass on” or “warn out” shelterless paupers, antebellum civic leaders sought to control and rehabilitate the vagrant poor in regimented caretaking institutions.[18]

The vast majority of those we might now call homeless, however, managed to avoid whatever care the almshouse afforded by earning their subsistence in the economy of the streets. Indeed, when antebellum commentators talked of the “vagrant mode of life,” they denoted not homelessness per se, but the casual labor that poor city dwellers increasingly pursued. Peddling, scavenging, begging, prostitution, petty thievery, gambling, and any other “disorderly” public activity that threatened or “injured” the moneymaking potential of urban real estate all fell under the legal purview of vagrancy. By 1860 entire neighborhoods of the propertyless poor, like New York City’s notorious Five Points in lower Manhattan, became known as “vagrant” districts not only because of their degraded housing conditions, but also because of their illegal street economies. That relatively settled neighborhood residents could be deemed vagrants attests to the enduring and multifaceted nature of vagrancy in nineteenthcentury America.[19]

As these historical precedents suggest, the tramp crisis of 1873–78, while eclipsing everything that had come before in its breadth and intensity, was not entirely, as one journalist claimed in 1877, like “a thunderburst from a clear sky.”[20] Indeed, the great army of tramps was in many ways merely another variation on the old, if ever-changing, theme of American homelessness stretching back to the days of colonization. Gilded Age tramps, like their homeless predecessors, took to the road because of dislocation and unemployment or because of new opportunities resulting from economic expansion. Just as propertyless migrants in the early nineteenth century encountered an array of law enforcement and charity officials bent on punishing, incarcerating, or rehabilitating them, so, too, did late-nineteenth-century tramps. Indeed, tramps of the 1870s inspired a whole new generation of vagrancy laws and workhouse disciplines. But, also like earlier vagrants, most tramps found temporary refuges of their own in working-class neighborhoods and the casual labor economy.

Middle-class perceptions of crisis in the Gilded Age also mirrored earlier panics over vagrancy. The factors generating concern about the “vagrant mode of life” in the antebellum period also fueled the tramp scare of the 1870s: the struggles between the propertied and unpropertied over the uses of public space, fears about the growth of a propertyless proletariat, and anxieties about the loss of traditional social controls in American cities. Viewed from one perspective, the rise of America’s great tramp army in the 1870s proves nothing more than the biblical adage “the poor you have with you always.”

But, to borrow again from Scripture, American homelessness was a house of many mansions, and the great army of tramps possessed numerous features distinguishing it from previous groups of the migrant poor. As the term “tramp” suggests, what struck Gilded Age Americans most about the new homeless army was its stunning mobility. Jacob Riis’s constant shifting back and forth between and within metropolitan regions was not unusual. Unemployed men of the 1870s routinely traveled hundreds of miles at a stretch. Even in a nation where over half the population changed residences every ten years, such extreme mobility caused alarm.

The primary reason for this new mobility was the vast expansion of the nation’s railroad network in the years following the Civil War. A loose collection of tracks in the antebellum period, railroad lines expanded into a tightly connected web by the 1870s, adding as much as 7,379 miles in a single year and attaining a total mileage of 93,000 by 1880.[21] With a continental network of transportation and communication in place, the consequences of industrial life—beneficial and unsavory alike—penetrated every corner of the land. Created to deliver commodities to a great national market, railroads now also transported, often without remuneration, an increasingly footloose working class that circulated throughout industrial America after the Civil War. No longer were the problems of vagrancy and floating workers contained within metropolitan regions. Almshouses that had previously served local paupers now swelled with nonlocal tramps who could not claim residency anywhere.[22] America, it seemed to many, was overrun with wandering strangers. To make matters worse, those who wandered most tended also to be the poorest.

What was it about the post-Civil War years that put the poor in motion? Elite observers often attributed Gilded Age migrations to a certain “roving disposition” among the poor.[23] Jacob Riis, however, revealed the predominant cause while describing his arrival in New York City from New Brunswick, New Jersey, where he had previously worked in a brickyard:

It was now late in the fall. The brick-making season was over. The city was full of idle men. My last hope, a promise of employment in a human hair factory, failed, and, homeless and penniless, I joined the great army of tramps, wandering about the streets in the daytime with the one aim of somehow stilling the hunger that gnawed at my vitals, and fighting at night with vagrant curs or outcasts as miserable as myself for the protection of some sheltering ash-bin or doorway.[24]

Jacob Riis’s dependence on wages had made him vulnerable to seasonal shifts in the demand for labor, a vulnerability that compelled him to scavenge for the food and shelter he could not purchase on the market. In other words, Jacob Riis, like millions of other Americans, had discovered firsthand the problem of unemployment.

Although the problem of unemployment might seem as old as time, it is actually a fairly recent phenomenon. In fact, the word “unemployment” did not even appear in print in America until 1887.[25] The experience of joblessness, of course, predated the term, as any Jacksonian-era laborer standing outside the shuttered doors of his former workshop could have attested. But unemployment did not become a widespread problem until roughly the eve of the CivilWar, when, for the first time, a solid majority of Americans in the industrializing North worked for others. In the first half of the nineteenth century, most northern heads of households were selfemployed, either as farmers, artisans, or tradesmen who owned the property they used to make a living. Although they all faced periods of “forced idleness,” self-employed property owners possessed precious “shelters against unemployment” that allowed them to subsist during slack periods. Farmers and shop owners controlled the pace of their labors and prepared for intervals of inactivity. In addition to growing their own food, farming families also manufactured at home important necessities—such as clothing, soap, and candles—that wage-earning people had to buy on the market. Finally, for those Americans who did work for others, the customary intimacy of the small farm and workshop often generated personal bonds between employers and their workers that protected employees from being laid off during economic downturns.[26]

Through the course of the nineteenth century, the ever-encroaching tide of commercial exchange steadily eroded these protections. By the 1870s they had diminished to the vanishing point. Most northerners were now wage earners who did not own productive property and who encountered their employers in relations of the market rather than paternalist authority. In such cases, the seasonal inactivity such as Jacob Riis experienced precipitated not a routine shifting of productive activity, but rather a desperate search for the cash income one needed to survive.

Seasonal inactivity marked virtually every field of occupation, from agriculture to industry. Outdoor labor—harvesting, dock work, canal digging, and building of all sorts, for example—had to be done in temperate months, leaving many unemployed during the winter, a season when poorhouse populations swelled.[27] Indoor labor in factories and workshops also had their idle periods, usually corresponding to the cycles of consumer demand. These slack periods—coupled with local, regional, and national business cycles—made for highly volatile employment patterns. One scholar estimates that between 20 and 25 percent of all northern wage earners spent at least three months jobless during the average year in the late nineteenth century, with both figures rising sharply during depressions.[28]

Once jobless, many wage earners had little choice but to move. Housing, which earlier in the century had provided a resource for subsisting through idle periods, was now a cash drain that required the constant transfer of wages into rent.[29] “I’ll give you one instance out of a hundred how workingmen manage to live in these hard times,” explained one worker in the 1870s. “A man moved eighteen times in two years without paying his rent.”[30] The lack of cheap public transportation meant that most workers had to live within walking distance of their workplaces. Since each neighborhood supported only a limited amount of wage labor, losing one’s job quite often required changing one’s residence. Under these circumstances shelter was anything but permanent, and being caught, like Riis, without lodging or the means to pay for it became a routine hazard of working-class life.

Just how far and in what direction jobless migrants traveled once on the road depended largely upon their point of origin and the skill level they expected from their jobs. Most migration involved cities, either as departure points or destinations. Cities with diverse employment opportunities sustained comparatively higher and more stable employment rates than smaller communities dominated by fewer industries and trades.[31] Rather than pursue random itineraries, then, jobless migrants everywhere traveled predictable routes to urban centers, expecting with reason that cities would offer good chances for employment. As Riis found in New York City, however, moving to a metropolis was not a guarantee of finding work. Whether or not an urban job search succeeded, migration to a city exposed the tramping worker to a greater variety of subsequent migration options. The larger transportation networks available to urban migrants— such as carriage roads, water routes, and especially railroads—broadened the choice of travel methods and destinations, as Riis demonstrated when he tramped, ferried, and hitched freight trains to Philadelphia after his traumatic experiences on the streets of New York.[32] Cities also served as information centers on labor market conditions elsewhere, enabling migrants to determine with greater precision what travel routes would likely lead them to jobs. Twenty years before urban lodging-house districts provided institutional frameworks for disseminating such information, Jacob Riis and other transient men of the 1870s gathered reports from the job front in the streets, parks, and saloons surrounding cheap boardinghouses.

Whether into or out of metropolises, short migrations, such as Riis’s trip from New Brunswick to New York City, were more common than longer ones, especially among “casual” workers who circulated around fixed and familiar territories. Most tramping workers, especially unskilled day laborers, headed for the closest cities and towns where they thought they might find work. Skilled workers tended to tramp farther than their less skilled cohorts, taking advantage of the Gilded Age’s rapidly expanding railroad networks to plot more elaborate travel routes.[33] Jacob Riis’s longer migrations, such as his direct trips back and forth between Pittsburgh, Buffalo, and New York City, generally corresponded with stints as a carpenter, furniture maker, and journalist. Once these highly skilled jobs ended, Riis often then traveled shorter distances to surrounding towns or villages, picking up whatever work he could, usually casual labor in a factory, lumber camp, or on a farm. Skilled workers were also more likely to pursue wage opportunities in rapidly growing communities of the Midwest and West. These places especially attracted large numbers of workers in building trades who followed construction booms only to depart when demand inevitably slackened. Jacob Riis’s very first migration in the United States was to build housing for coal miners in what soon became the industrial town of East Brady, Pennsylvania. After “some temporary slackness in the building trade,” Riis then tried mining (“one day was enough for me”) and various kinds of casual labor before pawning his clothes for a trip back to New York.[34]

Unlike previous generations of jobless migrants, the tramp army of the 1870 s contained large numbers of skilled workers like Riis.[35] Some of these workers benefited from formal “tramping systems” sponsored by unions of printers, carpenters, cigar makers, iron molders, and miners to control and accommodate the mobility of their notoriously footloose members.[36] The vast majority of “tramping artisans,” however, migrated without the aid of union-sponsored traveling cards, relief funds, and lodgings. Especially during depressions, most skilled workers stole freight train rides, begged meals, competed for common labor, and faced vagrancy arrest right alongside their less skilled compatriots. By the time Jacob Riis found himself among the great army of tramps, occupational skill provided precious little buffer against the hazards of seasonal unemployment.

In addition to finding work, another ongoing task a jobless migrant faced when in a new district was securing shelter. By the turn of the century, virtually every American city contained lodging house neighborhoods that offered transient workers a wide array of cheap lodging options, from full private rooms in furnished hotels to dry spaces on saloon floors. In the 1870s, however, the temporary lodging market was still in its infancy, and most tramping workers roomed in private homes or in small boarding houses. The most affordable boarding arrangements in the 1870s were in tenements, which were already overcrowded and offered few amenities that could not be scavenged elsewhere. Finding himself “crowded out of the tenements of the Bend by their utter nastiness,” the destitute Jacob Riis turned to the doorways of Chatham Square, which, in dry weather, provided a cheaper (and perhaps better) opportunity for sleeping, despite periodic roustings by police officers.[37] Outside of larger cities, cheap boarding options were scarce, leaving transients like Riis to inhabit barns, wagons, and sheds, often even when employed.

Another shelter alternative for migrants both in small towns and large cities was the public lodging provided by poorhouses and police stations. Even if, as Jacob Riis testified, public lodging was a last resort for “honest” homeless men, it was nonetheless an increasingly common recourse for the migratory poor during the 1870s. Overnight lodging was one of the first functions performed by the newly organized urban police departments of the 1850s. Nineteenth-century police departments often fed and lodged more persons than they arrested, although during seasons of slack labor demand, an otherwise homeless “lodger” could be locked up as a criminal vagrant. By the 1870s police stations had replaced poorhouses as the primary public lodging for indigent working-age males. Conditions of police station lodging varied, but most provided only temporary shelter on bare floors for a few days or hours, leaving lodgers to shift for themselves once released. By the end of the century, a growing chorus of social reformers led by Jacob Riis would condemn the short-term, unsupervised relief offered by police stations as an encouragement to tramping. By that time, however, cheap private lodging houses had begun to replace police stations as the poor man’s last resort. Before then, approximately one adult male in twenty-three slept in a police station at some point in his life, and between io and 20 percent of American families contained a member who had lodged. In the late nineteenth century, police station lodging was a familiar and even routine experience for many poor Americans.[38]

The rise of police station lodging signaled major changes in the social composition of the migratory homeless. Whereas previous populations of vagrants exhibited considerable ethnic, gender, and even racial diversity, those who gained admission to police stations in the 1870s were a remarkably homogenous group. Bordering as it was on incarceration, admission to police station lodging hardly seems a privilege. But given the importance of police stations in underwriting the mobility of tramps, denial of admission could effectively bar a poor person from conducting a migratory job search at all. As a result, only a narrow segment of the laboring population could respond to their job insecurity through the extreme and deliberate transiency of a Jacob Riis.

Poor women, for example, were excluded from police station lodging, one reason they were not counted among the great army of tramps. Homeless women have always existed, but in the late nineteenth century their presence so disrupted settled notions of dependent womanhood that they were quickly rendered “invisible,” either by being placed in protective custody or by being recruited into the army of female “tramps,” that is, prostitutes, that occupied nineteenth-century urban centers.[39] Subsisting through an economy of sex, rather than itinerant labor, was indeed one of the few options available to indigent women. While female wage opportunities in manufacturing and domestic services improved during the nineteenth century, the kind of extensive migrations often required to maintain employment were exceedingly difficult for female workers. On the road, women faced frequent harassment, violence, as well as exclusion from such public services as police station lodging. In order to prevent women from hitting the road in the first place, charitable organizations founded unprecedented numbers of caretaking institutions for poor women that housed and often put the indigent to work before they could even begin their job searches. Thus, only a little over 6 percent of all jobless migrants who applied for public aid in New York State in the winter of 1874 and 1875 were female; of these, over half were accompanied by husbands.[40] In Philadelphia the proportion of women vagrants incarcerated in the city’s House of Correction dropped dramatically between the antebellum period and the 1870s, from about half to a quarter or fewer. Accounting for this decline was the extreme underrepresentation of women among the increasing numbers of transient poor. The rise of “mothers’ pensions” and other protectionist measures in the early twentieth century ensured that tramping, as it emerged in the 1870s, remained an experience defined almost exclusively by men.[41]

In addition to sex, race also played a large role in determining the social composition of America’s tramp army in the 1870s. African Americans had long idealized geographic mobility as a crucial component of freedom, both before and after the end of slavery. For slaves, self-emancipation often involved long, arduous journeys, whether escaping individually or in mass during the CivilWar. After the war black migration continued as former slaves took to the road for diverse reasons: to search for family members, to establish independent livelihoods, and, as Peter Kolchin so aptly puts it, simply “to affirm their freedom.”[42]

Infusing this ideal of free movement with even greater urgency was the coordinated campaign on the part of white planters and their political allies in the South to coerce black workers to stay put. Southern power brokers after the Civil War sought to secure their rural labor force by restricting mobility through debt peonage, draconian vagrancy ordinances, and a uniform structure of low wages. Without the right to move on their own terms, African Americans were effectively barred from the privileges of tramping. Southern homelessness, therefore, tended to be a white, urban, and relatively infrequent experience, a product of the same patterns of wage employment that created larger-scale homelessness in the North.[43]

Homelessness among African Americans in the North was even rarer proportionately than in the South. Late-nineteenth-century surveys of public lodgers report consistently low rates of black admission; only 2.3 percent of New York State’s homeless aid recipients during 1874 and 1875, for example, were African American.[44] Nonlocal black paupers became especially rare, for few poor African Americans dared to step foot on the road. The black aversion to tramping is attributable not only to outright racial discrimination in public assistance, but also to the hostility and violence that blacks could expect to encounter on the road itself. Simply put, black migrants could not count on the already haphazard kindness of strangers—not to mention railroads, missions, and municipal authorities—upon which the transient homeless so often depended.

Tramps often threw up barriers of their own to black migration. The large number of Irish immigrants in America’s tramp army suggests that the road itself may have served as a critical racial proving ground for poor white men. Notorious for their particularly virulent brand of white supremacy, Irish immigrants accounted for almost one-half of police station lodgers and vagrants.[45] Jacob Riis’s disdain for his fellow tramps stemmed in part from his dislike of the “Irishmen” with whom he was forced to share the road. While German-, English-, and native-born men all found their places in the great army of tramps, the Irish wayfarer became a common Gilded Age stereotype, one that gained strength and currency toward the turn of the century. Indeed, as new waves of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe poured into the country, the equation of Irishness and tramping became even more pronounced as the newcomers failed to take their places in the tramp army. By the 1890s the sons of older immigrants and native-born Americans were replenishing the army’s ranks, while the new immigrants followed their own distinct patterns of group migration.

Regardless of nativity or nationality, Gilded Age tramps, like their footloose forebearers, were overwhelmingly young. Tramping was a young man’s pursuit, a virtual stage in the working-class life cycle. Age figures culled from police and relief records document a median age for tramps in the mid- to late twenties, with the vast majority being under forty and unmarried.[46] Old age, of course, did not preclude poverty. But age did discourage many of the elderly poor from exercising the migration options so often seized by the young, a fact that explains why local poorhouses of the period increasingly took on characteristics of old-age homes. One fortyeight-year-old tramping worker told an investigator in 1893 that although he had “tramped and roamed about more in my life than any man of my age” and had experienced “all the vicisitudes [sic] and hardships it is possible for a human to stand,” he still remained “Hale and Harty [sic]” and tramped when jobless instead of taking refuge in almshouses.[47] Although being single contributed to this older migrant’s continued transiency, two important attributes of youth—health and hardiness—also certainly permitted him to pursue the migratory existence he thought preferable to institutionalization.

In contrast to this persistent vagabond, the vast majority of Gilded Age vagrants did not make a career out of tramping, roaming about for months or years on end. For most homeless wanderers, the road represented a brief stage of poverty, an episodic experience rather than a permanent condition. Almost 90 percent of those migrants who applied for public aid in New York State in 1874–75 had been on the road for less than one month. Fewer than 5 percent of police station lodgers surveyed in 1891–92 had been tramping for more than one year. Vagrancy arrest records from the period reveal low rates of recidivism, with three-quarters of incarcerated vagrants having committed no previous offense. Far from a stable population, America’s Gilded Age tramp army relied on high turnover rates and fresh recruits to maintain its muster rolls.[48]

As a variation on an old theme, the rise of the Gilded Age tramp army signaled the triumph of an industrial capitalist order that had been generations in the making. But that army’s unique features—its mobility and its preponderance of white men—also reflected the transitional character of the 1870s. Having completed its long march toward dominance, the wage labor system now conferred upon the country, and the laboring classes in particular, a crisis of home and work that would endure for the next three-quarters of a century. Faced with the diminishing use value of home as productive property and an increasing dependence on wages, working people responded in various ways, from scavenging, taking in boarders, and going into debt to the more extreme recourses of institutional relief. For the young (or at least hale and hardy), white, male members of the northern working class, moving about from place to place and doing without the luxury of “home” was an additional possibility. One can even consider life on the road as something of an option, albeit a dire and life-threatening one, among competing strategies of survival. Homeless men would certainly have recognized their own feelings in labor leader Terence Powderly’s recollection of his “painful experience as a tramp” in 1874 when he was uniformly “unsuccessful, footsore, heart-sick and hungry.”[49] But, weighing their options, many must have also considered the road to be the most agreeable way to endure their poverty. Those who pursued this option joined an already overstocked mobile labor force that the nation’s rapidly expanding industrial economy required.

However, by the fall of 1873, when Jacob Riis quit his migratory habits by finding a secure employment niche in New York City journalism, the great army of tramps had yet to emerge as a topic of widespread concern. When tramps did make their dramatic appearance on the American landscape, their presence provoked strong reactions from a culture that had long promoted free labor as a national system. Beholding the spectacle of ragged, road-weary nomads tramping up and down the country, middleclass observers questioned each other about the origins of these grim travelers. Some recognized their colonial, even Old World, provenance. Others saw the tramp army as an entirely novel phenomenon. In developing their various explanations, legislators, journalists, clergymen, and social commentators of all stripes formulated imaginative origin myths of tramping that disclose much more about the concerns of the dominant culture than they do about tramps themselves. By addressing the problem of the tramp, civic leaders grappled with new problems of labor discipline and class conflict, as well as with broad cultural crises of nation, community, and family that the triumph of corporate capitalism had precipitated. In the vision of a rising tramp army, the middle classes saw a force alien and hostile to all they had worked so hard to achieve: “the deadly foe,” as one writer put it, “to civilization, thrift, and property.”[50]

Tasting of the “fountain of Indolence”: Origin Myths of Tramping

Given the coincidence of industrial depression and mass joblessness with the rise of tramps in the 1870s, one might expect the most learned commentators on the tramp crisis to have recognized its roots in the problem of unemployment. Such, however, was not the case. Surprising as it seems, a preponderance of official opinion rejected out of hand any contention, usually proffered by labor tribunes, that members of the tramp army were involuntary conscripts. Like the American Social Science Association president Francis Wayland, most pundits considered tramps to be flouting the primal curse: “By the sweat of thy brow shall thou eat bread.”[51] The litany of adjectives used to describe tramps invariably began with “lazy” and “shiftless” before winding its way to “sauntering” and “savage.” Consequently, few experts who approached the matter from the perspective of charity administration or social science blamed the tramp crisis on the depression. Echoing the mass of expert opinion, the NewY ork Times argued in 1877 that “if the tramp nuisance is ever brought to an end in this country, it will not be by a return of prosperous times.” “Good times,” the paper concluded, “will only make things easier for him.”[52]

The charge of laziness only begged the question of what had caused this epidemic of indolence in the first place. Those who took up this question offered various theories. Almost all noted American habits of “indiscriminate charity” that discouraged the “able-bodied poor” from working. Others pointed to the flood of poor immigrants from Ireland, unschooled in the habits of thrift and industry and perhaps irreclaimable in their degeneration. Inspired by the burgeoning pseudoscience of eugenics, some theorized tramps to be the issue of degenerate immigrants who reproduced at higher rates than the racially “purified.”[53]

One further theory about the origins of the “tramp nuisance” recurs so frequently in the 1870s that one might fairly call it one of the period’s prevailing explanations for why men tramp. Time and again, the literature on tramping returns to “the lazy habits of camp-life” acquired by the millions of men who served in the Union army during the CivilWar.[54] “This tramp system is undoubtedly an outgrowth of the war,” stated one Massachusetts police official in 1878. “The bummers of our armies,” he continued, “could not give up their habits of roving and marauding, and settle down to the honest and industrious duties of the citizen.” Another charities official in 1877 explained that the war had taught “to a large number of laboring men, the methods of the bivouac.” Having learned how to travel quickly, find temporary shelter, forage for food, and otherwise “trust tomorrow to take care of to-morrow,” the Civil War veteran, according to this theory, possessed the skills necessary to live without working.[55]

Renowned private detective and Union army spy Allan Pinkerton also had no doubt that “our late war created thousands of tramps.” Having spent part of his youth as a tramping barrel maker in Scotland, Pinkerton had a great fondness for army “camp-life,” but admitted that the only habits it fostered were “to play social guerilla and forage.”[56] Similarly, the first novel about tramping, Lee O. Harris’s The Man Who Tramps: A Story of To-day, explains the rise of tramping with reference to the Civil War. In telling his story about villainous tramps who “stir up strife between capital and labor,” Harris digresses to describe how the war lured many of the “manufacturing and producing classes” into the thralls of trampdom. “The reckless, free life of the army had given them a taste for wandering and a distaste for every species of labor,” Harris explains. Once discharged, old soldiers recruited others into the habits of the bivouac, which offered “so many fascinations, so much change and adventure.” “Once having tasted of the fountain of indolence,” Harris writes, these men “lost all wish to labor” and consequently became “professional tramps.”[57]