Translated by Nina Zumel

A Selection of Horacio Quiroga's Stories

Introduction: Reading Horacio Quiroga

Exploring the dark tales of this Uruguayan author.

I recently found Horacio Quiroga’s short story “The Dead Man” in Clifton Fadiman’s 1986 collection The World of the Short Story, and it’s given me a new hobby: tracking down all of his short stories that I can find.

I’ve seen Quiroga’s stories compared variously to Edgar Allan Poe, Ambrose Bierce, William Faulkner, and Rudyard Kipling; he himself acknowledged the influences of Poe, Kipling and de Maupassant on his work. Like Poe, he had a theory of the perfect short story (one he often contradicted in his own work). Also like Poe, and he was incredibly obsessed with death, and fascinated with madness as well.

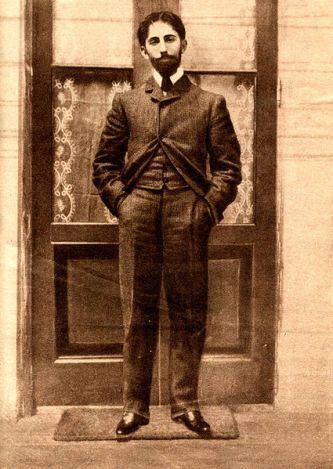

This morbid viewpoint is not surprising, given Quiroga’s own life history. His father accidentally shot himself on a hunting trip and later his stepfather deliberately shot himself (apparently, Quiroga witnessed it). In 1900, when Quiroga would have been about twenty-one, his two brothers died of typhoid fever. The following year, one of Quiroga’s best friends, Federico Ferrando, was challenged to a duel. Since Ferrando knew nothing about guns, Quiroga offered to check Ferrando’s gun for him — and accidentally shot and killed Ferrando in the process. Though Quiroga was found innocent of any crime, his own feelings of guilt led him to leave his native Uruguay for Argentina.

In Buenos Aires he worked as a teacher. He also became fascinated with the jungle, eventually buying a farm in the jungle province of Misiones. This fascination with the jungle, in particular its indifference to human life, informs a great deal of his work (shades of Algernon Blackwood’s Canadian tales!). In 1909 he married one of his students, Ana Maria Cires. The couple moved out of the city to Quiroga’s farm, where they had two children. But this wilderness life didn’t suit Ana, and in 1915 she poisoned herself.

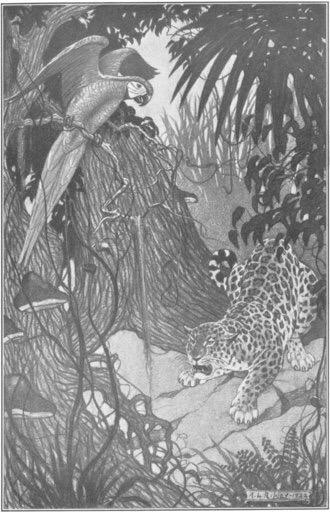

It was about this time that Quiroga wrote the short story collections that established his reputation, the 1917 collection Cuentos de amor, de locura y de muerte (Tales of Love, Madness and Death) and the 1918 collection of children’s tales, Cuentos de la selva (Tales of the Jungle). Cuentos de amor… is, well, just like it says: stories of obsession, madness, failed relationships, brutal and deadly jungle life. Cuentos de la selva is lighter-hearted: tales of humans and animals coexisting in the jungle, sort of a less imperialistic Jungle Book. It’s delightful—but there is still plenty of death and violence. I’m not sure if parents would be recommending it for their children, today. Quiroga also uses the device of telling a story through the eyes of animals in some of his adult stories, as well, though not always as benignly.

Throughout the twenties Quiroga put out several more short story collections: Anaconda (1921), El desierto (The Desert, 1924), and Los desterrados (The Exiled, 1926), which is said to be his best collection. In addition to his usual themes of death and of brutal, unforgiving jungle life, it’s no surprise that death by accidental shooting shows up a few times as well, in particular in “El hombre muerto” (“The Dead Man” — from Los desterrados), and “El hijo” (“The Son” — from the 1935 collection Más allá (Further On)).

Quiroga married again in 1928 (to one of his daughter’s classmates!), and settled with her in Misiones. She left him about 1935, and a few years later Quiroga was diagnosed with terminal prostrate cancer. He committed suicide by poison in 1937. He was 58.

Though Quiroga is considered one of the fathers of the Latin American short story, he seems less well known in Anglophone countries than the Argentinian magical realists who came after him. I found a couple of volumes of selected stories in translation, both from the University of Texas Press: The Decapitated Chicken and Other Stories (originally published 1976) and The Exiles and Other Stories (originally published 1987). Much of his work has fallen into the public domain (at least somewhere), and you can find it readily online in Spanish. I’ve been itching to try some more translations, for practice; so far I’ve done two of Quiroga’s stories, and I hope to do more.

“El almohadón de plumas” (The Feather Pillow) is one of Quiroga’s earlier stories, originally published in 1904, later included in Cuentos de amor, de locura y de muerte. I think every amateur who has ever tried translating Quiroga has taken a crack at this one, first of all because it’s short, and second because its ending packs quite a punch. It’s a good first introduction to his work, as well.

“El Solitario” (The Solitaire) is also from Cuentos de amor, de locura y de muerte. When I first saw the title I read it as “The Loner” (or “The Solitary Man”) — Google will translate it as “The Lonely Man.” I suspect that the double meaning between solitario as “solitary man” and “diamond solitaire” is not accidental. This is not a jungle story, but it’s certainly a tale of love and madness.

Do check them out. I hope you enjoy them. I’ll update here at Multo as I complete more stories.

If you are up for the original Spanish, you can find much of Quiroga’s writing at Spanish Wikisource. Cuentos de amor, de locura y de muerte and an English translation of Cuentos de la selva (as South American Jungle Tales) are at Project Gutenberg.

You can also find a few of Quiroga’s stories, translated, at the Translated Works of Horacio Quiroga site. I plan to try to keep my selections mostly separate from theirs, but there are few stories that I really like, and I might do them myself, anyway.

If you like Poe, de Maupassant, or generally have a taste for the morbid, do check Horacio Quiroga out.

References

Arrechedora, Iraima. “Horacio Quiroga: Biografía, Obras y Premios Recibidos,” lefeder.com

Encylopedia Britannica entry on Horacio Quiroga.

Fadiman, Clifton. Introduction to “The Dead Man,” The World of the Short Story, edited by Clifton Fadiman, Houghton Mifflin, 1986.

Wikipedia entryon Horacio Quiroga.

The Feather Pillow

Her honeymoon was one long frisson. Blonde, angelic, and timid, her husband’s stern character had chilled her childish girlhood dreams. She loved him very much; yet at times, when returning at night together with him on the street, she would glance furtively and with a light shiver at Jordan’s tall stature, silent for over an hour. He, for his part, loved her profoundly, without realizing it.

For three months—they had married in April—they lived in a special bliss. No doubt she would have preferred less severity in this rigid paradise of love, more expansive and reckless tenderness; but her husband’s impassive countenance remained self-contained.

The house in which they lived contributed to her shivers. The whiteness of the silent patio, its friezes, columns, and marble statues, produced the autumnal impression of an enchanted palace. Inside, the glacial brilliance of the stucco, without the slightest scratch on the high walls, reinforced the sensation of bleak cold. When crossing from one room to another, one’s footsteps echoed throughout the house, as if a long abandonment had made the house more sensitive in its resonance.

In this strange love nest, Alicia passed the entire autumn. By the end, she had cast a veil over her long-ago dreams, yet still lived somnolently in the hostile house, not wanting to think of anything until her husband arrived home.

It’s not strange that she would lose weight. She had a light attack of influenza that dragged on insidiously for days; Alicia never recoverd. Finally one afternoon she was able to go out to the garden, supported on her husband’s arm. She gazed indifferently from one side to the other. Suddenly Jordan, with profound tenderness, stroked her head, upon which Alicia burst into sobs, throwing her arms about his neck. For a long time, she wept out her silent terror, redoubling her tears at the least tentative caress. Later her sobs subsided, and yet she remained for a long time, her face hidden in his neck, without moving or saying a word.

It was the last day that Alicia was able to get up. The following day she awoke, faint. The doctor examined her with great attention, ordering absolute calm and rest.

“I don’t know,” he said to Jordan at the street door, with his voice still lowered. “She’s very weak, and I can’t explain it, no vomiting, nothing…. If tomorrow she wakes like this, call me immediately.”

The next day Alicia was worse. There were consultations. They verified an aggressive, completely inexplicable anemia. Alicia had no more fainting spells, but she was visibly on the verge of death. All day the bedroom stayed fully lit, in complete silence. Hours passed without the least noise. Alicia slept. Jordan almost lived in the front room, also with all the lights burning. He walked ceaselessly from one end to the other, with untiring obstinancy. The carpet muffled his footsteps. At times he went into the bedroom and continued his mute pacing beside the bed, watching her face each time he walked in her direction.

Soon Alicia began to have hallucinations, confused and floating at first, and then descending to the ground. The young woman, her eyes wide open, constantly watched the carpet on either side of the back of the bed.

“Jordan! Jordan!” she cried, rigid with terror, without taking her eyes from the carpet.

Jordan ran to the bedroom, and on seeing him appear Alicia screamed in horror.

“It’s me, Alicia, it’s me!”

Alicia looked at him strangely, looked at the carpet, looked at him, and after a long moment of stupified contemplation, became serene. She smiled and taking his hand between hers, caressed it, trembling.

Among her more stubborn hallucinations was an ape, his fingers brushing the carpet, his eyes fixed on hers.

The doctors returned, but it was useless. In front of them was a life that was fading, bleeding out day by day, hour by hour, without them knowing how. In the last consultation Alicia lay in a stupor while they took her pulse, passing her inert wrist from one to the other. They stood in silence for some time, and then proceeded to the dining room.

“Pst…,” the doctor slumped his shoulder, discouraged. “It’s a serious case… there’s little we can do…”

“There’s something I’m missing!” Jordan sighed heavily, his fingers drumming in agitation on the table.

Alicia was overcome by the delirium of her anemia, which worsened in the afternoon, but always receded in the early hours. During the day her illness did not progress, but each morning she awoke pale, barely conscious. Only at night, it seemed, did her life leave her, on new wings of blood. She had always on awakening the sensation of collapsing into the bed under a great weight. From the third day this sinking sensation never left her. She could barely move her head. She didn’t want others to touch the bed, not even to arrange her pillows. Her twilight terrors advanced in the form of monsters that crawled towards the bed, and climbed with difficulty up the bedspread.

Later, she lost consciousness. The two final days she raved ceaselessly in a low voice. The lights stayed burning funereally in the bedroom and front room.

At last, she died. The maid, entering alone afterwards to unmake the bed, stared with surprise at the pillow for some time.

“Señor,” she called to Jordan in a low voice. “These look like bloodstains on the pillow.”

Jordan approached quickly and bent over the pillow in turn. Sure enough, on the pillowcase, on both sides of the indentation left by Alicia’s head, there were small dark spots.

“They look like bites,” murmured the maid after a moment of intent observation.

“Hold it up to the light,” Jordan said.

The maid picked up the pillow, but immediately let it fall, and remained staring at it, pale and trembling. Without knowing why, Jordan felt his hair stand on end.

“What is it?” he whispered hoarsely.

“It’s heavy,” the maid said, still trembling.

Jordan picked up the pillow; it was extraordinarily heavy. They left the room with it, and on the dining room table Jordan cut away the pillowcase and slit open the pillow. The upper feathers flew in the air, and the maid gave a scream of horror, her mouth wide open, her clenched hands flying to the sides of her face. On the pillow’s cover, between the feathers, slowly moving its hairy legs, was a monstrous animal, a slimy, living ball. It was so swollen that it could hardly move its mouth.

Night after night, while Alicia lay in bed, it had stealthily attached its mouth—or more accurately, its proboscis—to her temple, sucking her blood. The bite was almost imperceptible. The daily arranging of the pillow had no doubt slowed its progress, but when the young woman could no longer move, the bloodsucking accelerated dramatically. In five days, in five nights, it had sucked Alicia dry.

These parasites from birds, so small in their usual environment, under certain conditions reach enormous proportions. Human blood seems especially favorable to them, and it’s not unusual to find them in feather pillows.

From the collection Cuentos de amor de locura y de muerte (Stories of love, madness and death), 1917.

Translated by Nina Zumel

The Solitaire

Kassim was a sickly man, a jeweler by profession, though he had no established shop. He worked for the big houses, his specialty being the mounting of precious stones. There were few who had hands like his for delicate settings. With more ambition and commercial ability, he would have been rich. But at the age of thirty five he went on as he always had, a fixture in his workshop under the window.

Kassim, with his wart-covered body, his bloodless face darkened by a sparse black beard, had a beautiful and fiercely passionate wife. The young woman, a child of the streets, had hoped to use her beauty to marry up. She had hoped this for twenty years, provoking men and the other neighborhood women with her body. But, fearful at the end, she had nervously accepted Kassim.

But now, no more dreams of luxury. Her husband, though skilled—an artist, even–completely lacked the character for making a fortune. So while the jeweler worked hunched over his tools, she, leaning on her elbows, would maintain on her husband an intense, drawn-out stare, later to abruptly tear herself away and turn her gaze through the window at some passerby who could have been her husband.

Whatever Kassim earned, however, was for her. He worked Sundays, too, for the extra money. When Maria wanted a piece of jewelry—and with what passion she would want it!—he worked nights. Afterwards, he would pay with coughs and stabbing pains in his side; but Maria had her sparkly bauble.

Little by little the daily exposure to gems gave her a love for the work of the craftsman, and she studied passionately the intimate delicacies of a setting. But when the piece was finished–he had to send it off, it wasn’t for her–she regretted more deeply the deception of her marriage. She would try on the jewelry, posing before the mirror. At last she would leave it there, and go to her room. Kassim would arise on hearing her sobs, and would find her on the bed, ignoring him.

“But I do as much as I can for you,” he would say at last, sadly.

Her sobs would grow louder at this, and the jeweler would slowly reinstall himself at his bench.

This scene was repeated, so much so that Kassim no longer got up to console her. Console her! For what? But this did not prevent Kassim from prolonging his evenings even more, to make bigger bonuses.

He was an indecisive man, irresolute and quiet. His wife now regarded his mute tranquility with an even more intense fixity.

“And you think you’re a man!” she murmured.

Kassim did not pause the movement of his fingers upon his work.

“You’re not happy with me, Maria,” he said after a while.

“Happy! You have the nerve to say that! Who could be happy with you? Not the last woman on earth… Poor devil!” Concluding her speech with a nervous laugh, she left.

Kassim worked that night until three in the morning, and then his wife had new sparkles, which she considered for an instant with pursed lips.

“Hmmm…it’s not an impressive diadem!…When did you do it?”

“I’ve been working on it since Tuesday.” He gazed at her with feeble tenderness. “While you were sleeping.”

“Oh, you could have gone to bed!…Such huge diamonds!”

For her passion was for the immense stones that Kassim set for his clients. She followed his work with a crazed hunger for it to be finished then and there, and the piece would hardly be completed before she would run with it to the mirror. Then, a fit of sobs.

“Anyone, any husband, the least of them, would make sacrifices to please his wife. But you…you…not even one miserable dress do I have to wear!”

Once she has lost enough respect for him, a woman is capable of saying to her husband the most incredible things.

Kassim’s wife crossed that line with a passion at least equal to the passion she felt for diamonds. One afternoon, while locking up his jewels, Kassim noticed that a brooch was missing–two solitaires worth five thousand pesos. He looked through his drawers again.

“You haven’t seen the brooch, have you Maria? I left it here.”

“Yes I saw it.”

“Where is it?” he responded, surprised.

“Here!”

His wife stood there, with burning eyes and a mocking smile, wearing the brooch.

“It looks good on you,” Kassim said after a moment. “Let’s put it away.”

Maria laughed.

“Oh no! It’s mine.”

“Are you joking?”

“Yes, it’s a joke! A joke, yes! How it hurts to think it could be mine…Tomorrow I’ll give it to you. Tonight I’m wearing it to the theater.”

Kassim’s expression changed.

“You can’t do that….they could see you. They would lose all trust in me.”

“Oh!” Without another word, she left in an infuriated huff, slamming the door shut violently.

On returning from the theater, she put the brooch on the nightstand. Kassim picked it up and locked it away in his workshop. When he came back, his wife was sitting on the bed.

“That means you’re afraid that I’ll steal it! That I’m a thief!”

“Don’t look at me like that… you’ve been reckless, nothing more.”

“Ah! And they trust you with it! You! And when your wife asks you for just a little gratification, and she wants… you call me a thief! Disgraceful!”

She fell asleep at last. But Kassim did not sleep.

Later on, they sent Kassim a solitaire to mount, the most magnificent diamond that had ever passed through his hands.

“Look Maria, what a stone. I’ve never seen another like it.”

His wife said nothing; but Kassim felt her breathing deeply over the solitaire.

“Such admirable clarity,” he continued. “It must cost nine or ten thousand pesos.”

“A ring!” Maria murmured at last.

“No, it’s for a man… A stickpin.”

In time to the mounting of the solitaire, Kassim felt on his laboring back all the burning resentment and frustrated vanity of his wife. Ten times a day she would interrupt her husband to stand with the diamond in front of the mirror. Then she would try it with different outfits.

“If you want to do that afterwards….” Kassim ventured. “This is a rush job.”

He waited for a response, in vain; his wife opened the doors to the balcony.

“Maria, they can see you!”

“Take it! There’s your stone!”

The solitaire, flung violently away, rolled along the floor.

Kassim, pale, examined it as he picked it up, then raised his eyes from the floor to his wife.

“Well, why do you look at me like that? Did something happen to your stone?”

“No,” said Kassim. And he resumed his work at once, although his hands trembled piteously.

But at last he had to get up to see his wife in the bedroom, having a complete nervous breakdown. Her hair had fallen loose and her eyes bulged from their sockets.

“Give me the diamond!” she cried. “Give it to me! We’ll run away! It’s mine! Give it to me!”

“Maria…” Kassim stammered, trying to extricate himself.

“Ah!” his crazed wife screamed. “You are the thief, you miserable dog! You’ve stolen my life, you thief…thief! And you thought I wouldn’t get even… you thought I wouldn’t find someone else! Aha! Look at me… it never occurred to you, eh? Ah!” And she raised both hands to her choking throat. But when Kassim turned to go, she jumped from the bed and tripped, grasping for her prize.

“It doesn’t matter! The diamond, give it to me! That’s all I want! It’s mine, Kassim, you wretch!”

Kassim helped her up, pale.

“You’re not well, Maria. We’ll talk later… go to bed.”

“My diamond!”

“All right, we’ll see if it’s possible… go to bed.”

“Give it to me!”

And the bile rose again in her throat.

Kassim resumed working on the solitaire. Since his hands had a mathematical precision, he only needed a few more hours.

Maria arose to eat, and Kassim showed her the same attention as usual. At the end of the dinner his wife looked him straight in the face.

“It’s a lie, Kassim,” she said.

“Oh!” said Kassim, smiling. “It’s nothing.”

“I swear it’s a lie!” She insisted.

Kassim smiled again, patting her hand with awkward affection.

“Silly! I told you it’s all forgotten.”

And he got up and went back to work. His wife, with her face between her hands, continued to watch him.

“And he won’t say more than that…” she murmured. And with a deep nausea for that clingy, limp, inert creature who was her husband, she went to her room.

She did not sleep well. She awoke late in the evening and saw light in the workshop; her husband was still working. An hour later, he heard a shriek.

“Give it to me!”

“Yes it’s for you; just a little left to do, Maria,” he said hurriedly, getting up. But his wife, after that shout from her nightmare, fell back asleep. At two in the morning Kassim was finished; the diamond gleamed, secure and virile in its setting. With silent steps he went to the bedroom and turned on the bedside lamp. Maria slept on her back, in the icy whiteness of her nightgown and the sheet.

He went to the workshop and returned again. For a moment he contemplated her almost completely exposed breast, and with a faint smile he nudged her loose nightgown down a little more.

His wife did not feel it.

There was not much light. Kassim’s face suddenly acquired a hard immobility. For an instant he suspended the jewel high above her naked breast, and then, holding it firmly and perpendicular like a nail, he sank the entire pin into his wife’s heart.

There was a sudden opening of her eyes, followed by a slow drop of her eyelids. Her fingers arched, and nothing more.

The jewel, shaken by the convulsions of her wounded nervous system, trembled for an unsteady instant. Kassim waited a moment; and when the solitaire at last remained perfectly still, then he withdrew, closing the door after himself without a sound.

From the collection Cuentos de amor de locura y de muerte (Stories of love, madness and death), 1917.

Translated by Nina Zumel

The Artificial Hell

On nights when there is a moon, the gravedigger advances through the tombs with a singularly stiff step. He is nude to the waist and wears a large straw hat. His fixed smile gives the impression of being stuck to his face with glue. If he were barefoot, one would notice that he walks with his big toes turned down.

There is nothing strange about this, because the gravedigger abuses choloroform. The hazards of his trade led him to try the anesthestic, and when choloroform bites a man, it rarely lets go. Our acquaintance waits for night to open his bottle, and as he has great common sense, he chooses the cemetery for the inviolable theater of his binges.

Chloroform dilates the chest on the first whiff; the second fills the mouth with saliva; the extremities tingle at the third; at the fourth one’s lips swell, along with one’s ideas, and then odd things happen.

As if in a dream the gravedigger’s steps have taken him to an open tomb, where that afternoon there had been a disenterment—unfinished for lack of time. A coffin was left open behind the gate, and at its side, on the sand, the skeleton of the man who had been enclosed in it.

Did he hear something? Really? Our acquaintance draws back the bolt, enters, and then after a bewildered turn around the bone man, he kneels and puts his eys to the orbits of the skull.

There, in the back, a little above the base of the cranium, perched as if on a parapet in the roughness of the back of the skull, is huddled a little shivering yellow man, his face crossed with wrinkles. He has a bruised mouth, deeply sunken eyes, and a gaze mad with anguish.

He is all that remains of a cocaine addict.

“Cocaine! Please, a little cocaine!”

The gravedigger, serene, knows well that he himself would dissolve the glass of his bottle with his spit in order to reach the forbidden chloroform. It is, therefore, his duty to help the little shivering man.

He leaves and returns with a full syringe, provided by the cemetery medical kit. But how to give it to the tiny little man?

“Through the cranial fissures! … Quickly!”

Of course! How had that not occurred to him? And the gravedigger, on his knees, injects the fissures with the entire contents of the syringe, which filters and disappears between the cracks.

But surely something has reached the fissure that the little man desperately clings to. After eight years of abstinence, what molecule of cocaine doesn’t ignite a delirium of strength, youth, beauty?

The gravedigger put his eyes to the orbits of the skull, and didn’t recognize the dying little man. There was not the least trace of a wrinkle on his firm smooth skin. His vibrant red lips were intertwined with a lazy voluptousness that would have no manly explanation, if narcotics were not almost all feminine; and above all his eyes, which before were glassy and dull, now shone with such passion that the gravedigger felt an pang of envious surprise.

“And that’s what it’s like … cocaine?” he murmured.

The voice from inside sounded with ineffable charm.

“Ah! You have no idea what eight years of agony are! Eight desperate, freezing years, tied to eternity by the lone hope of a drop! Yes, it’s because of cocaine… And you? I know that smell… chloroform?”

“Yes,” replied the gravedigger, ashamed by the paltriness of his artificial paradise. And he added in a low voice: “Chloroform, too… I would kill myself before I quit.”

The voice sounded a bit mocking.

“Kill yourself! And that would be the end of you, for sure; you would be just like any of these neighbors of mine… You would rot in three hours, you and your desires.”

“True,” thought the gravedigger, “my cravings would perish with me. But his did not surrender. After eight years it still burns, that passion that has resisted the very absence of the cup of delight; that overcame the final death of the organism who created it, sustained it, and could not annihilate it with himself; that survives monstrously on its own, transmuting the causal craving in a supreme final pleasure, maintaining itself before eternity in a crevice of an old skull.”

The voice, warm and slurred with voluptuousness, still sounded mocking.

“You would kill yourself… Nice thing! I killed myself, too… Ah, that interests you, doesn’t it? But we are of different temperaments…. Anyway, bring your chloroform, breathe in a little more and listen to me. Then you will appreciate what goes from your drug to cocaine. Come on, now!”

The gravedigger returned, and lying on the ground chest down, leaning on his elbows with the flask under his nose, he waited.

“Your chloro! It’s not much, let’s say. And even morphine … Are you familiar with the love for perfumes? No? And Jicky, by Guerlain? Listen, then. At thirty I married, and had three children. With a fortune, an adorable wife and three healthy offspring, I was perfectly happy. Nevertheless, our house was too large for us. You’ve seen such places. You have not…to be brief…seen that luxuriously furnished rooms seem more lonely and useless. Above all, lonely. Our whole palace existed like that, in silence, in sterile and gloomy luxury.

“One day, in less than eighteen hours, our oldest son left us following a bout of diptheria. The following afternoon the second joined his brother, and my wife threw herself desperately upon the only one we had remaining: our daughter of four months. What did we care about diptheria, contagion and all the rest? In spite of the doctor’s orders, the mother breastfed her child, and after a while the little one was writhing and convulsed, to die eight hours later, poisoned by her mother’s milk.

“Add it up: 18, 24, 9. In 51 hours, a little more than two days, our house was left perfectly silent, and there was nothing we could do. My wife stayed in her room, and I paced nearby. Outside of that nothing, not one noise. And two days before we had three children…

“Well. My wife spent four days clawing at the sheets with a brain fever, and I turned to morphine.

“‘Leave that alone,’ the doctor told me, ‘it’s not for you.’

“‘What, then?’ I replied. And I pointed out the gloomy luxury of my house, which kept on slowly igniting catastrophes, like rubies.

The man took pity.

“‘Try sulfonal, anything… But your nerves will not give way.’

“Sulfonal, brional, datura… bah! Ah, cocaine! So much of the infinite goes from the joy scattered in ashes at the foot of each empty bed, to the radiant recovery of this same burnt happiness, fit in one lone drop of cocaine! The wonder of having suffered an immense pain, moments before; sudden and simple confidence in life, now; an instantaneous resurgence of illusions that brings the future closer to ten centimeters from the open soul, all this rushes through the veins from the platinum needle. And your chloroform!… My wife died. For two years I spent on cocaine so much more than you can imagine. Do you know something of tolerance? Five centigrams of morphine kills a robust individual. Quincey came to take two grams a day for fifteen years; or forty times more than a fatal dose.

“But one pays for it. In me, intoxicated day after day, the dismal truths, suppressed, began to take revenge, and I had barely enough twisted nerves to throw aside the horrible hallucinations that besieged me. Then I made unheard of efforts to rid myself of the demon, with no success. Three times I resisted the cocaine for a month, an entire month. And I fell again. And you don’t know, but you will know one day, what suffering, what anguish, what sweat of agony you feel when you attempt to suppress drugs for a single day!

“At last, poisoned to the depths of my being, fraught with tortures and phantasms, transformed into trembling human spoils, bloodless, lifeless—misery to which ten times a day cocaine lent a radiant disguise, only to sink me immediately into a stupor, deeper each time, in the end a remnant of dignity sent me to a sanatorium, I surrendered myself tied hand and foot for a cure.

“There, under the dominance of another’s will, constantly monitored so that I could not obtain the poison, I would forcibly de-cocaineize myself.

“Do you know what happened? That I, along with the heroism to submit myself to torture, brought a small vial of cocaine, well hidden in a pocket… Now you work out what passion is.

“For an entire year after this failure, I continued to inject myself. Undertaking a long voyage gave me I don’t know what mysterious strength of resistance, and then I fell in love.”

The voice fell silent. The gravedigger, who had been listening with a drooling smile plastered to his face, brought his eye closer and thought he noticed a slightly opaque and glassy veil in the eyes of his interlocutor. His skin, as well, cracked visibly.

“Yes,” the voice continued, “that’s the beginning … I’ll conclude at once. I owe you, a colleague, this whole story.

“Her parents did everything possible to resist: imagine, a morphine fiend! For misfortune —mine, hers, everyone’s—had put in my path a high-strung beauty. Oh, admirably beautiful! She was no more than eighteen. Luxury for her was what cut crystal is for a perfume: her natural environment.

“The first time that, having forgotten to give myself a new injection before she arrived, she saw me suddenly deteriorate in her presence, become an idiot, crumple, she fixed on me her immensely large eyes, beautiful and frightened. So curiously frightened! Pale and unmoving, she saw me giving myself the injection. For the rest of the evening, she never left off watching me for an instant. And behind those dilated eyes that had seen me in that state, I saw in my turn her neurotic defects, her hospitalized uncle, and her younger epileptic brother…

“The next day I found her inhaling Jicky, her favorite perfume; in twenty-four hours she had read how much is possible with narcotics.

“Well, now: it’s enough that two people drink in the pleasures of life in an abnormal way, so as to understand them more intimately; how much stranger is the quest for enjoyment. They immediately join together, excluding all other passion, to isolate themselves in the hallucinatory joy of an artificial paradise.

“In twenty days, that enchantress of beauty, youth and elegance hung suspended in the heady fragrance of perfumes. She began to live, as I did with cocaine, in the delirious heaven of her Jicky.

“In the end this mutual somnambulism in her house, however fleeting, seemed dangerous to us, and we decided to create our own paradise. None seemed better than my own house, in which nothing had been touched, and to which I had not returned. Wide, low couches were brought to the living room, and there, in the same silence and the same funereal sumptuousness that had incubated the death of my children; in the profound stillness of the living room, with a lamp burning at one in the afternoon; below the atmosphere heavy with perfumes, we lived for hours and hours our fraternal and taciturn idyll, I sprawled out motionless with open eyes, as pale as death; she flung across a divan, holding the flask of Jicky below her nostrils with her frozen hand.

“For we had in ourselves not the least trace of desire—and how beautiful she was with the deep circles under her eyes, her disarranged hair, and the ardent luxury of her immaculate skirt!

“For three consecutive months she was rarely absent, and never without explaining to me what combinations of visits, weddings, and garden party she had to attend to avoid suspicion. On those rare occasions she would arrive anxious the following day, entering without looking at me, tossing her hat off with a brusque gesture, to stretch out immediately, her head thrown back and her eyes half-closed, to the sonambulism of her Jicky.

“Briefly: one afternoon, and by one of those inexplicable reactions with which poisoned organisms fire off their reserves of defense—morphine addicts know them well!—I felt all the deep pleasure that there was, not in my cocaine, but in that eighteen year old body, admirably made to be desired. That afternoon, as never before, her beauty emerged pale and sensual from the sumptuous stillness of the illuminated living room. So sudden was the jolt, that I found myself sitting on the couch, watching her. Eighteen years old… and with that beauty!

“She saw me approach her without making a movement, and as I bent over her she looked at me with cold surprise.

“‘Yes …’, I murmured.

“‘No, no …’ she said in a high voice, dodging my mouth in heavy movements of her hair.

“At last, at last, she threw back her head and surrendered, closing her eyes.

“Ah! Why be resuscitated for an instant, if my virile potency, if my male pride did not revive as well! It was forever dead, drowned, dissolved in the sea of cocaine! I fell to her side, sitting on the floor, and buried my head in her skirts, remaining so for an hour in deep silence, while she, very pale, also remained motionless, her eyes fixed on the ceiling.

“But the burst of reaction that had ignited an ephemeral lightning bolt of sensory ruin, also brought to the flower of my awareness how much of my masculine honor and virile shame was dying in me. The disaster of one day in the sanitarium, and the daily failure of my own dignity, was nothing in comparison to the failure of this moment, do you understand? Why live, if the artificial hell into which I had flung myself and from which I could not escape, was incapable of absorbing me altogether! And I had broken free for a moment, only to sink back into this final state!

“I stood up and went inside, to the well remembered rooms where my revolver still lay. When I returned, her eyes were closed.

“‘Let’s kill ourselves,’ I said to her.

“She half-opened her eyes, and for a minute she held my gaze. Her limpid brow returned to the same movement of tired ecstasy:

“‘Let’s kill ourselves,’ she murmured.

“Then she looked around the funereal luxury of the living room, in which the lamp burned high, and her brow furrowed slightly.

“‘Not here,’ she added.

“We left together, still heavy with hallucination, and we passed through the echoing house, room by room. At last she leaned against a door and shut her eyes. She fell at the foot of the wall. I then turned the gun on myself, and killed myself.

“Then, when at the explosion my jaw abruptly dropped, and I felt an immense buzzing in my head; when my heart gave two or three jolts, and stopped, paralyzed; when in my brain and in my nerves and in my blood there was not the most remote probability that life would return, I felt that my debt to cocaine was fulfilled. It had killed me, but I had killed it in turn!

“And I was mistaken! Because an instant later I could see, entering hesitantly and on hands and knees, through the door of the living room, our dead bodies, obstinately returning…”

The voice suddenly snapped.

“Cocaine, please! A little cocaine!”

From the collection Cuentos de amor de locura y de muerte (Stories of love, madness and death), 1917.

Translated by Nina Zumel

The Rabid Dog

On the 20th of March of this year, the residents of a town in the Santa Fe Chaco pursued a rabid man who, while trying to unload his shotgun on his wife, shot and killed a peón who crossed in front of him. His neighbors, armed, tracked him into the bush like a wild beast, finally discovering him climbing a tree, still with his shotgun, howling in a horrible way. They saw no choice but to shoot and kill him.

March 9.

Today it’s been thirty-nine days, hour by hour, since the rabid dog entered our room at night. If there is a memory that will live on in my mind, it’s that of the two hours that followed that moment.

The house had no doors except for the room Mamá occupied; since from the start she had been prone to fear, I didn’t do anything, in the first urgent days of moving in, other than saw boards for the doors and windows of her room. In our room, and in the hope of more work space, my wife contented herself—under a little pressure on my part, true—with magnificent doors of burlap. As it was summer, this detail of rigorous ornamentation didn’t damage our health or our fear. It was through one of these burlap portals, the one that gave onto the central corridor, that the rabid dog entered and bit me.

I don’t know if the shriek of an epileptic gives to others the sensation of a bestial clamor, beyond all humanity, that it produces in me. But I am sure that the howling of a rabid dog, lingering at night around our house, would provoke in everyone the same melancholy anguish. It is a short cry, strangled, agonized, as if the animal were already breathing its last, and all of it saturated with the grim suggestion of a rabid animal.

It was a black dog, large, with clipped ears. And to make things worse, from the time that we had arrived it had done nothing but rain. The wilderness enclosed by the rain, the short, depressing afternoons; we would hardly leave the house before the desolation of the countryside, in a storm without respite, would overshadow Mamá’s spirit.

With this, the mad dogs. One morning the peón told us that one had passed through his house the night before, and had bit one of his family. Two nights before, a reddish-gray dog had howled in an ugly way in the bush. There were several dogs, according to the peón. My wife and I did not give much importance to the matter, but this was not so for Mamá, who began to find our half-finished house terribly defenseless. Every moment she would go out into the corridor to watch the road.

But when our son returned that morning from town, he confirmed the news. A devastating epidemic of rabies had exploded. One hour earlier, they had chased a dog down in the village. A peón had had time to give it a machete-chop in the ear, and the animal, at a trot, nose to the ground and tail between its forelegs, had crossed our street, biting a foal and a pig that it had encountered on the way.

Still more news. In the farm neighboring ours, in the early hours of that same day, another dog had tried unsuccessfully to jump into the cattle corral. An immense skinny dog had run at a man on horseback on the trail to the old port. It was still afternoon when the agonized howl of a dog sounded in the bush. As a last piece of data, at nine two agents arrived at a gallop, giving us the details of the rabid dogs that had been seen, and recommending that we take the utmost care.

That was enough for Mamá to lose the rest of the courage she had left. Although she was serene through every trial, she was terrified of rabid dogs, because of something horrible that she had seen as a child. Her nerves, already on edge from the constantly overcast and rainy skies, conjured up realistic hallucinations of dogs trotting through the front door.

There was a real reason for this fear. Here, as everywhere where poor people have many more dogs than they can keep, the houses are prowled nightly by hungry dogs, to whom the dangers of the task–a shot or a badly thrown stone–have given the true behavior of wild beasts. They advance step by step, crouched low to the ground, muscles relaxed. One never notices their approach. They steal–if that word makes sense here–as much as their atrocious hunger demands. At the slightest murmur, they don’t flee, because that would make noise, but move away on bended legs. When they reach the grasses outside, they crouch down and wait there calmly thirty minutes or an hour, and then advance anew.

Hence, Mamá’s anxiety, since, as our house was one of the many being prowled, we were of course threatened by a visit from the rabid dogs, who would remember the nocturnal path.

In fact, that same afternoon, while Mamá, a bit forgetful, was walking slowly towards the front entrance, I heard her cry:

“Federico! A rabid dog!”

A reddish-grey dog, with its back arched, advanced at a trot in a blind straight line. On seeing me approach it stopped, the hair on its back bristling. I backed away withoug turning my body to search for the shotgun, but the animal fled. I went up and down the road in vain, without finding it again.

Two days passed. The countyside remained desolated by rain and sadness, while the number of rabid dogs increased. To avoid exposing the children to a terrible mishap on the infested roads, the school closed; and the already traffic-free road, thus deprived of the schoolchild racket that enlivened its solitude at seven and at twelve, acquired a gloomy silence.

Mamá did not dare to take a step outside the patio. At the least bark she peered, frightened, towards the front entrance, and just as night fell, she saw phosphorescent eyes advancing through the grass. After dinner she shut herself in her room, her hearing attentive for the most hypothetical howl.

It was on the third night that I awoke, when it was already very late; I had the impression of having heard a cry, but I couldn’t pin down the sensation. I waited a while. And suddenly a short metallic howl, of atrocious suffering, vibrated down the corridor

“Federico!” I heard Mamá’s voice, shot through with emotion. “Did you hear?”

“Yes,” I said, sliding off the bed. But she heard the noise I made.

“Dear God, it’s a rabid dog! Federico, don’t go out, for God’s sake! Juana! Tell your husband not to go out!” She cried out desperately, addressing my wife.

Another howl exploded, this time in the central corridor, in front of the door. A fine shower of chills washed my spine to the waist. I don’t think that there is anything more profoundly dismal than the howl of a rabid dog at that hour. Rising up above it was the desperate voice of my mother.

“Federico! It’s going into your room! Don’t go out, my God, don’t go out! Juana! Tell your husband! …”

“Federico!” my wife grabbed my arm.

But the situation could become quite serious if I waited for the animal to enter, and turning on the light I took down my shotgun. I raised the edge of the burlap over the doorway, and saw nothing but the black triangle of the deep fog outside. I hardly had time to step forward when I felt something firm and warm rub against my thigh: the rabid dog had entered our room. I threw its head back violently with a blow from my knee, and suddenly it lunged to bite me, but failed, with an audible clash of its teeth. But the next instant I felt a sharp pain.

Neither my wife nor my mother realized that it had bitten me.

“Federico! What was that?” cried Mamá, who had heard my halt before the bite at the air.

“Nothing: it wanted to come in.”

“Oh! …”

Again, this time beyond Mamá’s room, the ominous howl exploded.

“Federico! It’s rabid! Don’t go out!” she cried madly, hearing the animal through the wooden wall, a meter away from her.

There are absurd things that have all the appearance of legitimate reasoning: I went outside with the lamp in one hand and the shotgun in the other, exactly as if I were searching for a terrified rat that had provided me the perfect space to place the light on the ground and kill it at the end of a pitchfork.

I traversed the corridors. I didn’t hear a sound, but from inside the rooms I was trailed by the tremendous anguish of Mamá and my wife, who were waiting for the boom of the gun.

The dog was gone.

“Federico!” Mamá exclaimed on hearing me return at last. “Did the dog leave?”

“I think so; I didn’t see it. I think I heard its trot when I left.”

“Yes, I heard it too…Federico: it’s not in your room? … It hasn’t got a door, my God! Stay inside! It could come back!”

In effect, it could come back. It was two-twenty in the morning. And I swear that the two hours that my wife and I passed were intense, with the light on until dawn, she lying in bed, I sitting on the bed, constantly watching the floating burlap.

I had healed before. The bite was clean: two purple holes, which I compressed with all my strength, and washed with permanganate.

I didn’t really believe that the animal was rabid. Since the previous day they had begun to poison the dogs, and something in the overwhelmed attitude of our dog predisposed me in favor of strychnine. There remained the dismal howl and the bite; but anyway I was inclined to the first theory. From here, surely, came my relative carelessness with the wound.

Finally, day arrived. At eight o’clock, and four blocks from home, a passerby shot and killed the black dog with a revolver; it had been in an unequivocally rabid state. The moment we knew, I had on my part to fight a real battle against Mamá and my wife not to go down to Buenos Aires for shots. The wound, frankly, had been well compressed, and washed with a luxurious, bitingly painful amount of permangante. All this, within five minutes of the bite. What the hell could I be afraid of after this hygenic treatment? At home they finally reassured themselves, and as the epidemic—provoked by a crisis of rain without respite such as had never been seen here—had ended almost at once, life recovered its habitual routine.

But in spite of that Mamá and my wife did not leave off, and have not left off, taking exact account of time. The classical forty days weigh strongly, above all for Mamá, and even today, with thirty-nine days passed without the slightest ailment, she waits for tomorrow, in order to expel from her spirit, in an immense sigh, the everliving terror that she retains from that night.

Perhaps the only nuisance for me has been this: to remember, point by point, what has happened. I am confident that tomorrow night, with the end of the quarantine, will conclude this story that keeps the eyes of my wife and my mother fixed on me, as if they are searching my expression for the first sign of illness.

March 10.

At last! I hope that from now on I can live like any other man, who does not have crowns of death suspended above his head. I have passed the famous forty days, and the anxiety, the persecution mania and the horrible screams that they anticipated from me have also passed forever.

My wife and my mother have celebrated the joyous occasion in a particular way: by telling me, point by point, all the terrors that they have suffered without letting me see. My most insignificant lack of appetite plunged them into mortal anguish. “It’s the rabies beginning!” they moaned.

If some morning I arose late, for hours they stopped living, waiting for another symptom. The annoying infection in a finger that had me feverish and impatient for three days, was for them an absolute proof that the rabies had begun, from which came their consternation, more anguished for being furtive.

And so the least change of humor, the slightest dejection, provoked in them, over the forty days, many other hours of worry. In spite of these retrospective confessions, always disagreeable for one who has been in the dark, even with the most archangelic good will, I have laughed heartily at all of it. “Ah, my son! You can’t imagine how horrible it is for a mother to think that her son might be rabid! Anything else…. but rabid, rabid!”

My wife, although more sensible, has also rambled far more than she confesses. But now it’s over, thankfully! This situation of martyrdom, of a baby watched second to second against such an absurd threat of death, is not appealing, after all. At last, again, we will live peacefully, and hopefully tomorrow the past won’t dawn with a headache, and resurrect the craziness.

I wanted to be absolutely calm, but it’s impossible. There is no longer, I believe, any possibility that this will end. Sidelong glances all day, incessant whispering that stops suddenly when they hear my steps, an irritating spying upon my expression when we are at table, all this is becoming intolerable.

“What’s wrong, please?” I just said to them. “Do you see something abnormal about me, am I not exactly as always? This story of the rabid dog is already a bit boring!”

“But Federico!” they replied, looking at me with surprise. “We didn’t say anything to you, or remember doing so!”

And they don’t, however, do anything else, other than spy on me night and day, day and night, to see if the stupid dog’s rabies has infected me!

March 18.

For three days I have lived as I should and I would like to do so all my life. They have left me in peace, at last, at last, at last!

March 19.

Again! Again it’s begun! They don’t take their eyes off me anymore, as if what they seem to want has happened: that I am rabid. How is such stupidity in two sensible people possible! Now they no longer dissimulate, and they speak rashly aloud about me; but—I don’t know why—I can’t understand a word. As soon as I arrive they stop suddenly, and the moment I step away the dizzying chatter begins again. I could not contain myself and I turned with rage.

“But if you talk, say it in front of me, it’s less cowardly!”

I didn’t want to hear what they said and I left. This is no longer life that I’m living!

8 pm

They want to leave! They want us to leave!

Oh, I know why they want to leave me! …

March 20. (6 am)

Howling, howling! All night I’ve heard nothing but howling! I’ve spent all night waking up every moment! Dogs, there’s been nothing but dogs around the house tonight! And my wife and my mother have feigned the most placid dreams, so that only I would absorb through my eyes the howls of all the dogs that watch me!…

7 am

Nothing but vipers! My house is full of vipers! While washing myself there were three in the basin! There are several in the lining of the sacking! And there’s more! There are other things! My wife has filled my house with vipers! She has brought enormous hairy spiders that chase me! Now I understand why she spied on me day and night! Now I understand everything! This is why she wanted to leave!

7.15 am

The patio is full of vipers! I can’t take a step! No, no!…. Help!…

My wife is running away! My mother is leaving! They have murdered me!…Ah, the shotgun!…Damn it! It’s loaded with ammo! But it doesn’t matter…

What a scream she gave! I missed her… Again the vipers! There! There’s an enormous one! Ah! Help, help!!

Everyone wants to kill me! They’re all against me! The bush is full of spiders! They’ve followed me from the house!…

Here comes another assassin… He got them in his hand! He’s coming and throwing vipers to the ground! He’s pulling vipers from his mouth and throwing them to the ground towards me! Ah! but he won’t live long… I hit him! He’s died with all the vipers!… The spiders! Ah! Help!!

Here they come, everyone’s coming!… They’re looking for me, looking for me!… They’ve launched a million vipers against me! Everyone is putting them on the ground! And I have no more cartridges!… They’ve seen me!… One of them is pointing at me…

From the collection Cuentos de amor de locura y de muerte (Stories of love, madness and death), 1917.

Translated by Nina Zumel

The Spectre

Every night in the Grand Splendid in Santa Fe, Enid and I attend the film premieres. Neither storms nor icy nights prevent us from appearing, promptly at ten o’clock, in the pallid half-light of the theater. There, from one box or another, we follow the stories of the film in silence and with an interest that might draw attention to us, if our circumstances were other than they are.

From one box or another, I said; because its location is indifferent to us. And although we might be missing from the same spot some night, the Splendid being full, we settle ourselves, silent and always attentive to the performance, in any already occupied box.

I don’t think we bother anyone; at least, not in any appreciable way. From the back of the box, or between the young woman on the balcony and the boyfriend clinging to her neck, Enid and I, separate from the world that surrounds us, are all eyes towards the screen. And if in truth some people, with a nervous shiver whose origin they don’t quite understand, occasionally turn their heads to look for what they can’t see, or they feel an icy draft they can’t explain in the warm atmosphere, our intruding presence is never noticed; because it’s necessary to admit now that Enid and I are dead.

Of all the women that I knew in the world of the living, none of them had the effect on me that Enid did. The impression was so strong that the images and the very memory of all other women were erased. In my soul it was night, where a single imperishable star rose: Enid. The mere possibility that her eyes could look upon me with indifference would suddenly stop my heart. And at the idea that some day she could be mine, my jaw would tremble. Enid!

She had then, when we lived in the world, a more divine beauty than the epics of cinema have ever launched a thousand leagues and exposed to the fixed gaze of men. Her eyes, above all, were unique; and never did a velvet gaze have such a frame of eyelashes like Enid’s eyes: blue velvet, moist and calm, like the happiness that sobbed in them.

Misfortune put me in front of her when she was already married.

There is no reason now to hide names. Everyone remembers Duncan Wyoming, the extraordinary actor who, beginning his career at the same time as William Hart, had, like him and on par with him, the same deep talent for virile roles. Hart has already given to the cinema all that we could expect from him, and he is a falling star. From Wyoming, on the other hand, we don’t know what we could have seen, when right at the beginning of his brief and fantastic career he created—as a contrast to the cloying modern hero—the tough guy, coarse, ugly, careless, whatever you like; but a man from head to toe in the sobriety, the drive, and the distinctive character of the sex. Hart is still acting, and we’ve already seen it all. Wyoming was snatched from us in the prime of his life, leaving performances that resulted in two extraordinary films, according to the reports: The Wasteland and Beyond What Is Seen.

But the enchantment—the captivation of all the feelings of a man— that Enid exerted over me, was balanced by a equal bitterness: Wyoming, who was her husband, was also my best friend. It had been two years since we’d seen each other; he, occupied with his film work, and I with my literary work. When I found him again in Hollywood, he was already married.

“Here you have my wife,” he said to me, throwing her into my arms.

And to her:

“Give him a good hug, because you will never have a friend like Grant. And kiss him, if you like.”

She didn’t kiss me, but at the touch of her long hair on my neck, I felt with a shiver of all my nerves that I could never be a brother to this woman.

We lived two months in Canada, and it’s not difficult to understand my state of mind with respect to Enid. But not in one word, nor one movement, nor one gesture did I betray myself in front of Wyoming. Only she read in my glance, however calm, how deeply I wanted her. Love, desire… One and the other were twins in me, sharp and mixed; because if I desired her with all the strength of my ethereal soul, I adored her with all the torrent of my material blood.

Duncan didn’t see this. How could he have seen?

When winter came we returned to Hollywood, and Wyoming fell with the attack of the flu that would cost him his life. He left his widow with a fortune and no children.

But he was worried about the solitude in which he was leaving his wife.

“It’s not the economic situation,” he said to me, “but the moral abandonment. And in this hellhole of moviemaking…”

At the moment of his death, he beckoned his wife and me down to his pillow, and said, with a voice already labored:

“Trust yourself to Grant, Enid… While you have him, you have nothing to fear. And you, old friend, watch over her. Be her brother… No, don’t promise… Now I can go to the other side…”

There was nothing new in Enid’s pain or mine. After seven days we returned to Canada, to the same summer cabin that a month before had seen the three of us dining in front of the campfire. Just like then, Enid was staring now at the flames, wrapped in a glacial serenity, while I stood contemplating her. And Duncan was no more.

I must say it: in Wyoming’s death I saw nothing but the liberation of the terrible eagle caged in our hearts, namely the desire for a woman at our side who can’t be touched. I had been Wyoming’s best friend, and while he lived the eagle didn’t want his blood; it fed—I fed it—with my own. But between him and me had arisen something more solid than a shadow. His wife was, while he lived—and it would have been eternally—beyond my reach. But he had died. Wyoming couldn’t demand of me the sacrifice of the Life that he had just unraveled. And Enid was my life, my future, my breath and my yearning to live, that no one, not even Duncan—my intimate friend, though dead—could deny me. Look after her… Yes, but give to her what he had withdrawn on losing his tenure: the adoration of an entire life consecrated to her!

For two months, at her side day and night, I looked after her like a brother. But on the third month I fell at her feet. Enid looked at me, motionless, and surely Wyoming’s last moments arose in her memory, because she repulsed me violently. But I would not lift my head from her skirt.

“I love you, Enid,” I said. “Without you I’ll die…”

“You, William!” she murmured. “It’s horrible to hear you say that!”

“Anything you say,” I replied. “But I love you immensely.”

“Hush, hush!”

“And I have always loved you… You already know that.”

“No, I don’t know that!”

“Yes, you know.”

Enid kept pushing me away, and I resisted, with my head upon her knees.

“Tell me that you knew…”

“No, shut up! We are profaning…”

“Tell me that you knew…”

“William!”

“Just tell me that you knew that I have always loved you…”

Her tired arms surrendered, and I raised my head. I met her eyes for an instant, a single instant, before Enid broke down and cried upon her own knees.

I left her alone; and when an hour later I returned, white as snow, no one would have suspected, on seeing our simulated and calm everyday affection, that we had just distended the cords of our hearts until they bled. Because in the alliance of Enid and Wyoming there had never been love. Their union always lacked a blaze of foolishness, excess, injustice—the call of passion that incinerates all the morale of a man and scorches a woman in prolonged sobs of fire. Enid had been fond of her husband, nothing more; and he had been fond of her, nothing more than fond compared to me, who was the warm shadow of her heart, who burned with everything that she would not get from Wyoming, and whom she knew would give refuge to everything from her that he would not accept.

And later, his death, leaving a void that I had to fill with the affection of a brother… Of a brother, to her, Enid, who was my only thirst for happiness in this wide world!

Three days after the scene that I have just related we returned to Hollywood. And a month later the exact same situation repeated itself: I again at Enid’s feet with my head on her knees, and she trying to prevent it.

“I love you more each day, Enid…”

“William!”

“Tell me that some day you will love me.”

“No!”

“Just tell me that you are convinced how much I love you.”

“No!”

“Tell me.”

“Leave me alone! Don’t you see that you’re making me suffer horribly?”

And when she felt me trembling, mute, at the altar of her knees, she abruptly lifted my face between her hands:

“Just leave me alone, I tell you! Leave me alone! Don’t you see that I also love you with all my soul, and we are commiting a crime?”

Four months precisely, just one hundred twenty days from the death of the man that she loved, of the friend who had interposed me as a protective screen between his wife and a new love…I’ll make it short. Our love was so deep and intertwined, that even today I ask myself with amazement what absurd purpose might our lives have had if we had not found ourselves under Wyoming’s hands.

One night—we were in New York—I found out that The Wasteland, one of the two films that I mentioned, was finally playing; its premiere had been awaited anxiously. I, too, had the liveliest interest in seeing it, and I suggested it to Enid. Why not? We looked at each other for a long moment; an eternity of silence, during which memory galloped back among snowstorms and a dying face. But Enid’s gaze was life itself, and soon between the moist velvet of her eyes and of mine lay nothing but the convulsive joy of our adoration. And nothing more!

We went to the Metropole, and from the reddish half-light of the box we saw Duncan Wyoming appear, enormous and with a face as white as at the hour of his death. I felt Enid’s arm tremble beneath my hand.

Duncan!

Those were his same gestures. The same confident smile was on his lips. It was his same energetic figure that glided along the screen. And twenty meters from him was his same wife in the clasp of his close friend….

While the theater was in darkness, neither Enid nor I uttered a word or looked away from the screen for an instant. And silently, we returned home. But there Enid took my face between her hands. Large tears rolled down her cheeks, and she smiled at me. She smiled at me without trying to hide her tears.

“Yes, I understand, my love…” I murmured, with my lips on the end of her furs, which, being a dark detail of her outfit, likewise represented all of her idolized person. “I understand, but we won’t give in…Okay? So we’ll forget…”

For her entire answer, Enid, still smiling at me, clung without speaking to my neck.

The following night we went back. What did we have to forget? The other’s presence, vibrant in the beam of light that transported him to the screen, pulsating with life; his unconsciousness of the situation; his trust in his wife and his friend; this was precisely what we had to get used to. One night after another, always attentive to the characters, we witnessed the growing success of The Wasteland.

Wyoming’s performance was outstanding and developed in a drama of brutal energy; a small part in the forests of Canada and the rest in New York itself. The central situation involved a scene in which Wyoming, wounded in a fight with another man, abruptly discovers his wife’s love for that man, whom he had just killed from motives other than that love. Wyoming had just tied a handkerchief to his forehead. And stretched out on the couch, still gasping with fatigue, he observed the despair of his wife over her lover’s body.

Seldom have the revelation of a downfall, desolation and hate risen on a human face with more violent clarity than in Wyoming’s eyes in this scene.

The film’s direction had drawn out that marvel of expression to the point of torture, and the scene lasted an infinite number of seconds, when a single one would have sufficed to display, white-hot, the crisis of a heart in that state.

Enid and I, close together and unmoving in the dark, were lost in admiration for our dead friend, whose eyelashes almost touched us when Wyoming emerged from the background to fill the screen, alone. And when he receded again into the ensemble scene, the entire theater seemed to expand in perspective. And Enid and I, with a slight vertigo from this effect, still felt the touch of Duncan’s hair that had reached out to brush against us.

Why did we keep going to the Metropole? What quirk of our consciences brought us there night after night to drench our immaculate love in blood? What omen dragged us like sleepwalkers before a hallucinatory accusation that was not aimed at us, since Wyoming’s eyes were looking off to the side? Where were they looking? I don’t know where, at some box to our left. But one night I noticed, I felt to the roots of my hair, that his eyes were turning towards us. Enid must have noticed as well, because I felt the deep tremor of her shoulders under my hand. There are natural laws, physical principles that teach us how this cold magic works, about the photographic spectres dancing on the screen, mimicking to the most intimate details a life that has been lost. This hallucination in black and white is only the frozen persistence of an instant, the immutable engraving of one vital second. It would be easier for us to see at our side a dead man who had left his tomb to join us, than to perceive the slightest change in the pale trace of a film.

Perfectly true. But in spite of the laws and the principles, Wyoming was watching us. If for the rest of the theater The Wasteland was a romantic fiction, and Wyoming existed only by an irony of the light, if he was no more than an electric facade of celluloid without sides or back, for us—Wyoming, Enid, and I— the filmed scene was blatantly alive, but not on the screen, rather in the box, where our innocent love was transformed into a monstrous infidelity in front of a living husband…. An actor’s farce? Hate feigned by Duncan for that scene of The Wasteland? No! There was the brutal revelation: the loving wife and the close friend in the movie theater, laughing, with their heads close together, at the trust placed in them…. But we didn’t laugh, because night after night, from box to box, his gaze was turning each time more towards us.

“It won’t be long now!” I said to myself.

“Tomorrow will be the day…” Enid thought.

While the Metropole burned with light, the real world of physical laws empowered us and we breathed deeply. But in the sudden cessation of light, which we felt like a painful blow to our nerves, the spectral drama caught hold of us again.

A thousand leagues from New York, encased under the earth, Duncan Wyoming lay sightless. But his surprise at Enid’s frantic forgetfulness, his ire and his vengeance were alive here, lighting up Wyoming’s chemical vestige, moving in his living eyes, which finally ended up fixed on ours.

Enid stifled a scream and hugged me desperately.

“William!”

“Quiet, please…”

“But he’s just lowered a leg from the couch!”

I felt the hair on my back stand up, and I looked: with the deliberation of a wild beast and his eyes pinned on us, Wyoming sat up from the couch. Enid and I watched him stand, advance towards us from the background of the scene, become a monstrous close-up… a dazzling flash blinded us; at the same time Enid let out a scream.

The film had just caught fire.

But in the lit-up theater all the heads were turned towards us. Some had sat up in their seats to see what had happened.

“The lady is ill; she looks like a corpse,” said someone from the orchestra section.

“He looks even more dead,” someone added.

The usher had already handed us our coats and we left. What else? Nothing, except for all the following day Enid and I did not meet. Only on seeing each other for the first time at night to go to the Metropole, Enid now had in her deep pupils a darkness from beyond, and I had a revolver in my pocket.

I don’t know if anyone in the theater recognized us as the people who took ill the night before. The lights went out, came on, and went back out again, and not a single normal idea managed to settle into the brain of William Grant; nor did my tense fingers abandon the trigger of the gun for an instant.

I had been master of myself all my life. I had been until the night before, when against all justice a cold spectre, playing his daily photographic role, raised his strangling fingers towards a theater box to end the film.

As on the previous night, no one noticed anything unusual on the screen, and it was evident that Wyoming was still gasping, glued to the couch. But Enid—Enid within my arms!—had her face raised to the light, ready to scream… Then Wyoming sat up at last!

I saw him get up, grow larger, approach the same edge of the screen, without taking his gaze from mine. I saw him come down from the screen, come towards us in a beam of light; come through the air over the heads in the orchestra section, rise up, approach us with his head bandaged. I saw him extend his claw-like fingers…at the same time Enid gave a horrible shriek, as if with her vocal cords she had ripped away all her reason and set it aflame.

I can’t say what happened in the first instant. But following the first moments of confusion and smoke, I saw myself, with my body hanging off the railing of the box, dead.

From the instant in which Wyoming sat up on the couch, I had pointed the barrel of the revolver at his head. I remember this with total clarity. And it was I who got the bullet in the temple. I am completely sure that I meant to point the gun at Duncan. Except, believing that I was aiming at the murderer, in reality I aimed at myself. It was an error, a simple mistake, nothing more; but it cost me my life.

Three days later Enid in her turn was cast out of this world. And here concludes our romance. But it has not finished yet. A shot and a spectre are not enough to dispel a love like ours. Beyond death, beyond life and its bitterness, Enid and I have found each other. Invisible to the living world, Enid and I are always together, awaiting the announcement of another cinematic premiere. We have traveled the world. Anything is possible, except that the slightest incident in a film should pass unnoticed to our eyes. We have not gone to see The Wasteland again. Wyoming’s performance in that film can no longer bring us any surprises, outside of those that we so painfully paid for.

Now our hopes are placed on Beyond What is Seen. Seven years ago the film company announced its premiere, and for seven years Enid and I have been waiting. Duncan is the protagonist; but we will not be in the box anymore, at least not as we were when we were defeated. In the present circumstances, Duncan can make a mistake that allows us to enter the visible world again, in the same way as our living selves, seven years ago, allowed him to animate the frozen celluloid of his film.

Enid and I now occupy, in the invisible mist of the incorporeal, the privileged position of lying in wait that was all of Wyoming’s power in the previous drama. If his jealousy still persists, if he makes a mistake on seeing us and makes the least movement outward from the grave, we will take advantage of it. The curtain that separates life from death has not been drawn back only in his favor, and the portal is half-open.

Between the Nothingness that has dissolved what was once Wyoming, and his electrical resurrection, there remains an empty space. At the slightest movement that he makes, as soon as he comes off the screen, Enid and I will slip through the fissure into the dark corridor. But we will not follow the path to Wyoming’s grave, we will go towards Life, we will enter it anew. And it’s the warm world from which we were expelled, a love that is tangible and vibrant in every human sense, that awaits Enid and me.

Within a month or within a year, it will arrive. The only thing that worries us is the possibility that Beyond What is Seen will premiere under another name, as is the custom in this city. To avoid this, we never miss a premiere. Night after night, at ten o’clock on the dot, we enter the Grand Splendid, where we settle into a box; empty or already occupied, it doesn’t matter which.

From the collection El desierto (The Desert), 1924.

Translated by Nina Zumel

Juan Darién

Here is the story of a jaguar who was raised and educated among humans, named Juan Darién. He attended four years of school dressed in trousers and shirt, reciting his lessons correctly, though he was a jaguar from the jungle; but this is because his figure was that of a man, as narrated in the following lines.

Once, at the beginning of autumn, smallpox visited a village from a distant country and killed many people. Brothers lost their little sisters, and children just beginning to walk were left without father or mother. Mothers in turn lost their children, and one poor young widowed mother took herself to bury her baby son, the only thing she had in this world. When she returned home, she sat thinking about her little child. And she murmured:

“God should have more compassion for me, and he has taken my son. In heaven there may be angels, but my son doesn’t know them. It’s me that he recognizes, my poor son!”

And she gazed out in the distance, as she was sitting at the back of her house, facing a small gate through which the jungle was visible.

Now then: in the jungle there were many ferocious animals that roared at nightfall and at dawn. And the poor woman, who remained sitting, could see in the darkness something small and unsteady that entered through the gate, like a kitten that hardly had the strength to walk. The woman bent down and raised in her hands a jaguar cub, only a few days old, for its eyes were still closed. And when the miserable cub felt the touch of her hands, it purred with contentment, because now it was no longer alone. The mother held for a long moment, suspended in the air, this little enemy of humanity, this defenseless wild creature that she could exterminate so easily. But she remained pensive before the helpless cub who had come from who knows where, and whose mother was surely dead. Without thinking much about what she was doing, she took the little cub to her breast and enveloped it in her hands. And the jaguar kitten, on feeling the heat of her bosom, found a comfortable position, purred peacefully and fell asleep with its throat against the maternal breast.

The woman, still pensive, entered the house. And for the rest of the night, on hearing moans of hunger from the little cub, and on seeing how it sought her breast with its eyes closed, felt in her wounded heart that, before the supreme law of the Universe, one life is equivalent to another…

And she nursed the little jaguar.

The cub was saved, and the mother had found immense consolation. So great a consolation that she saw with terror the moment when it would be snatched from her, because if it came to be known in the village that she was nursing a savage being, they would surely kill the little creature. What to do? The cub, soft and affectionate–for it played with her upon her breast–was now her own son.

In these circumstances, a man who one rainy night was hurrying past the woman’s house heard a raspy whine—the harsh whine of wild beasts that, even newly born, startle human beings. The man halted suddenly, and while groping for his revolver, knocked on the door. The mother, who had heard his footsteps, ran madly with anguish to hide the little jaguar in the garden. But such was her luck that on opening the back door she found herself before a calm, old and wise serpent who blocked the way. The unfortunate woman was about to scream in terror, when the serpent spoke: