William Glaberson

Kaczynski Avoids a Death Sentence With Guilty Plea

Accepts Life Term Without Parole and Forgoes Right to Appeal

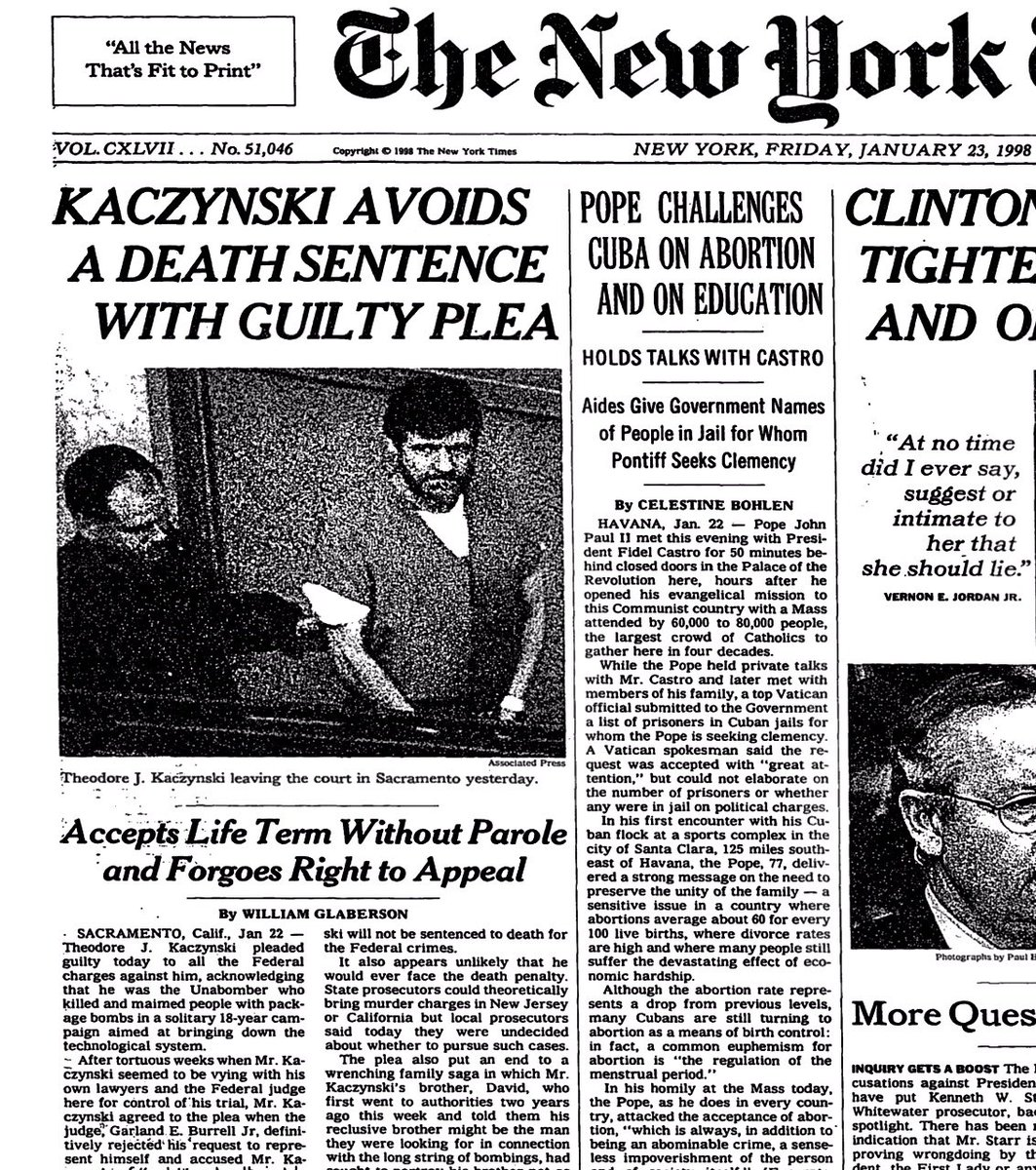

Theodore J. Kaczynski pleaded guilty today to all the Federal charges against him, acknowledging that he was the Unabomber who killed and maimed people with package bombs in a solitary 18-year campaign aimed at bringing down the technological system.

After tortuous weeks when Mr. Kaczynski seemed to be vying with his own lawyers and the Federal judge here for control of his trial, Mr. Kaczynski agreed to the plea when the judge, Garland E. Burrell Jr, definitively rejected his request to represent himself and accused Mr. Kaczynski of “a deliberate attempt to manipulate the trial process.”

The agreement was an unconditional plea under which Mr. Kaczynski accepted a sentence of life in prison without the possibility of release and gave up the right to appeal any rulings in the case. It resolved all Federal charges against him here and in Newark for bombings that killed three people and injured two others.

In addition to the three killings, prosecutors say, Mr. Kaczynski injured a total of 28 people in a meticulous and cold-blooded campaign aimed at challenging society by killing and maiming people he had never met, including intellectuals, business executives and, in some cases, students or airline passengers who somehow strayed into his sights.

“The Unabomber's career is over,” said the chief prosecutor, Robert J. Cleary.

The plea means that Mr. Kaczynski will not be sentenced to death for the Federal crimes.

It also appears unlikely that he would ever face the death penalty. State prosecutors could theoretically bring murder charges in New Jersey or California but local prosecutors said today they were undecided about whether to pursue such cases.

The plea also put an end to a wrenching family saga in which Mr. Kaczynski's brother, David, who first went to authorities two years ago this week and told them his reclusive brother might be the man they were looking for in connection with the long string of bombings, had sought to portray his brother not as an evil manipulator but as a troubled, mentally ill man.

David Kaczynski, whose actions provoked a national examination of the balance between familial loyalty and social duty, has repeatedly said that the death sentence the prosecutors sought represented cruel treatment of a disturbed man. David Kaczynski, clutching his 80-year-old mother, Wanda, worked his way into the center of a knot of reporters after his brother had accepted the plea and said they were deeply relieved.

“Our reaction to today's plea agreement,” he said, “is one of deep relief. We feel it is the appropriate, just and civilized resolution to this tragedy in light of Ted's diagnosed mental illness.”

Theodore Kaczynski had been fighting an increasingly futile battle to, in effect, insist on his sanity. But, particularly after a court-appointed psychiatrist diagnosed him as a paranoid schizophrenic last weekend, Mr. Kaczynski's struggle seemed more and more to highlight the legal system's difficulties in dealing with the mentally ill.

In a statement just after the plea was formalized in court, the chief prosecutor, Mr. Cleary, said the prosecutors were grateful for the “heroic acts” of David Kaczynski. “He is a true American hero,” Mr. Cleary said.

David and Wanda Kaczynski were in court today. As has been his custom, Theodore Kaczynski did not acknowledge their presence. They watched slumped in their front-row seats as their son and brother sat ramrod straight and in a high-pitched and polite voice acknowledged a catalogue of the Unabomber's horrific acts detailed by a prosecutor, R. Steven Lapham.

“Yes, Your Honor,” Theodore Kaczynski said in what sounded like cheerful tones as Judge Burrell asked him repeatedly if he acknowledged committing the acts described by Mr. Lapham. Mr. Lapham's list included the four bombings with which Mr. Kaczynski was charged here and 12 others in the campaign that lasted nearly two decades.

In the flat tones of a career prosecutor, Mr. Lapham described bombs that blew off people's fingers and brought death into a family kitchen. And he included quotes from Mr. Kaczynski's diaries that detailed his efforts to kill and, sometimes, his annoyance at failure.

One of the quotes Mr. Lapham read, from an entry from 1982, said Mr. Kaczynski had found it “frustrating, but I can't seem to make a lethal bomb.” In the third row, people who knew Hugh Scrutton, a Sacramento computer store owner, groaned. One woman held her head. On Dec. 11, 1985, Mr. Kaczynski admitted today, he left a bomb behind Mr. Scrutton's store that killed him.

The prosecutors said they had accepted the plea offer today because it was the first time Mr. Kaczynski had offered to plead guilty unconditionally.

Senior law enforcement officials in Washington said their interest in plea negotiations increased after the court-appointed psychiatrist, Sally C. Johnson, concluded that Mr. Kaczynski was a paranoid schizophrenic. That, combined with Mr. Kaczynski's unpredictable behavior in court, left them facing the prospect of being caught in the spectacle of trying a man whose insanity seemed evident.

In an interview on National Public Radio on Wednesday night, President Clinton suggested that he was opposed to a plea bargain and thought jurors should be able to decide whether to impose the death penalty.He said that if Mr. Kaczynski were guilty, “he killed a lot of people deliberately. And therefore I think it's something that the jury should be able to consider.”

In a news conference in Washington before the deal was complete Attorney General Janet Reno said the decision would be made internally at the Justice Department, which had not discussed the case with the White House.

Justice Department officials said the breakthrough came when Mr. Kaczynski's lawyers said he had given up his insistence on making only a conditional plea agreement that would have permitted him to appeal some of Judge Burrell's rulings.

In the courtroom today after the deal that had been much rumored and discussed nationally was complete, friends of one of the victims, Gilbert Murray, the president of the California Forestry Association who was killed by a bomb in 1995, said to each other, “It's finally over.”

In an aisle seat, Charles Epstein, a nationally known geneticist who was maimed by a bomb in 1993, squeezed the shoulder of his wife.

Mark O'Sullivan, a Federal Bureau of Investigation chaplain, read a statement from Gilbert Murray's widow, Connie, who said she supported the plea bargain but said the prosecutors had been right to seek the death penalty.

Mr. Murray was killed when he opened a package addressed to his predecessor at the Forestry Association. Mr. Kaczynski, the statement from Mrs. Murray said, “is a cold, calculated killer with no remorse. This was terrorism. Gilbert Murray was assassinated and there was no remorse even though he killed the wrong man.”

Mrs. Murray's statement said that Mr. Kaczynski's acts were little more than manipulation by a serial killer.

“Mr. Kaczynski saw loopholes in the system,” her statement read. “His manipulation of the system was very visible.”

Judge Burrell set May 15 for Mr. Kaczynski's formal sentencing. But Mr. Cleary said the plea arrangement did not permit any sentence of less than life in prison without any possibility of release.

In addition, Mr. Kaczynski, who has no known resources, could be fined $3,250,000. The agreement provided that if he should ever earn any money from writing, interviews or other endeavors, those profits would be used to pay restitution to the victims.

Mr. Kaczynski's demeanor was never somber today. He talked easily with the two lawyers with whom he has been warring for weeks, Quin Denvir and Judy Clarke, who sat on either side of him.

As Judge Burrell led him through the series of formalistic questions a judge must ask of a defendant who is pleading guilty, he seemed self-confident to the point of defiance. Occasionally, he seemed to see the situation as comic or absurd.

Judge Burrell asked his age, education and occupation. He was 55, he said. He had a Ph.D. in mathematics and his occupation was “an open question.”

“I was once an assistant professor of mathematics,” he said. “Since then I have spent time living in the woods in Montana.”