Alan Bullock

Hitler: A Study in Tyranny

Completely Revised Edition

PREFACE TO THE REVISED EDITION

BOOK I: PARTY LEADER 1889–1933

CHAPTER ONE: THE FORMATIVE YEARS 1889–1918

CHAPTER TWO: THE YEARS OF STRUGGLE; 1919–24

CHAPTER THREE: THE YEARS OF WAITING; 1924–31

CHAPTER FOUR: THE MONTHS OF OPPORTUNITY; October 1931–30 January 1933

CHAPTER FIVE: REVOLUTION AFTER POWER; 30 January 1933-August 1934

CHAPTER SIX: THE COUNTERFEIT PEACE; 1933–7

CHAPTER EIGHT: FROM VIENNA TO PRAGUE 1938–9

CHAPTER NINE: HITLER’S WAR; 1939

CHAPTER TEN: THE INCONCLUSIVE VICTORY; 1939–40

CHAPTER ELEVEN: ‘THE WORLD WILL HOLD ITS BREATH’; 1940–1

CHAPTER TWELVE: THE UNACHIEVED EMPIRE; 1941–3

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: TWO JULYS; 1943–4

CHAPTER FOURTEEN: THE EMPEROR WITHOUT HIS CLOTHES

1. WRITINGS AND SPEECHES OF ADOLF HITLER

4. SECONDARY WORKS WHICH CONTAIN OR MAKE USE OF ORIGINAL MATERIAL

[Front Matter]

[Title Page]

hitler A STUDY IN TYRANNY

by ALAN BULLOCK

Completely Revised Edition

HARPER TORCHBOOKS

The Academy Library

Harper & Row, Publishers

New York, and Evanston

[Dedication]

TO MY

MOTHER AND FATHER

[Copyright]

HITLER: A STUDY IN TYRANNY—Completely Revised Edition. Preface and newly revised material Copyright © 1962 by Alan Bullock. Printed in the United States of America.

This edition was originally published in 1964 by Harper & Row, Publishers, Incorporated.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address Harper & Row, Publishers, Incorporated, 49 East 38rd Street, New York 16, N.Y. First harper torchbook edition published March 1964 by Harper & Row, Publishers, Incorporated, New York and Evanston.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 63–21045.

CONTENTS

Preface to the Revised Edition 15.

Acknowledgements 18

Abbreviations 20

BOOK I

PARTY LEADER, 1889–1933

1 The Formative Years, 1889–1918 23

2 The Years of Struggle, 1919–24 57

3 The Years of Waiting, 1924–31 121

4 The Months of Opportunity, October 1931–30 January 1933 187

BOOK II

CHANCELLOR, 1933–9

5 Revolution after Power, 30 January 1933-August 1934 253

6 The Counterfeit Peace, 1933–7 312

7 The Dictator 372

8 From Vienna to Prague, 1938–9 411

9 Hitler’s War, 1939 490

BOOK III

WAR-LORD, 1939–45

10 The Inconclusive Victory, 1939–40 563

11 ‘The World Will Hold Its Breath’, 1940–41 610

12 The Unachieved Empire, 1941–3 651

13 Two Julys, 1943–4 704

14 The Emperor Without His Clothes 753

EPILOGUE 805

Bibliography 809

Index 817

ILLUSTRATIONS

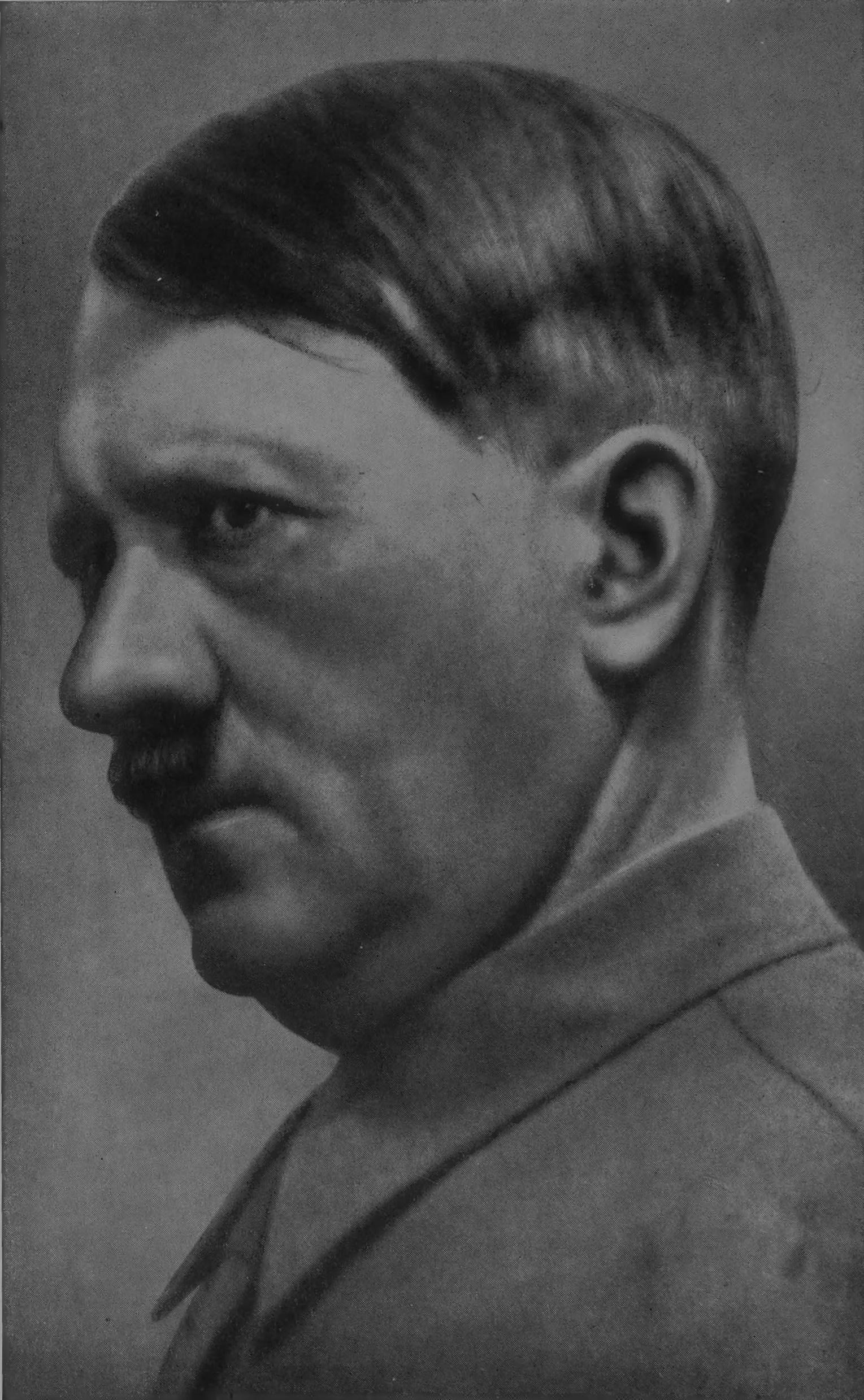

| Adolf Hitler | Frontispiece |

The following will be found after page 384:

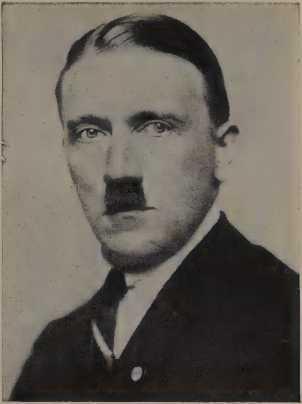

At the age of thirty-four

At Munich in the early 1920s

Leaving a Party meeting

In Weimar, 1926

With President Hindenburg

In Potsdam Garrison Church, 1933

In the Sportpalast

At the Nuremberg Parteitag, 1934

The Berghof

The Fuehrer’s study at the Berghof

Eva Braun

Hitler and Eva Braun

With Tiso, 1939

With Franco, 1940

Hitler and his Generals in 1941

After 20 July, 1944

Maps and Charts

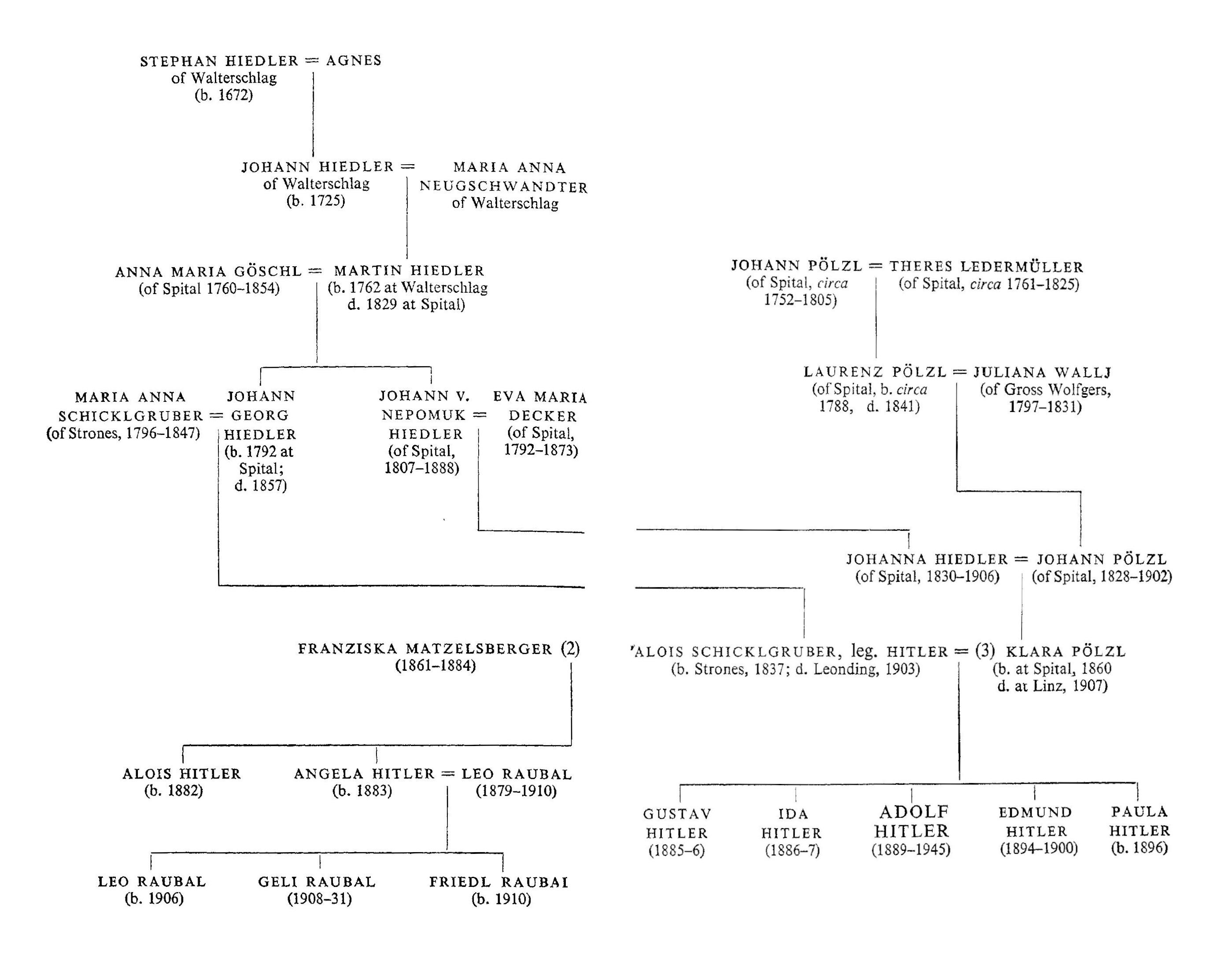

Hitler’s Ancestry

German Annexations, 1938–1939

Expansion of Hitler’s Empire, 1938–1943

[Epigraph]

Men do not become tyrants in order to

keep out the cold.

Aristotle, Politics

PREFACE TO THE REVISED EDITION

I first began this study with two questions in mind. The first, suggested by much that was said at the Nuremberg Trials, was to discover how great a part Hitler played in the history of the Third Reich and whether Goring and the other defendants were exaggerating when they claimed that under the Nazi regime the will of one man, and of one man alone, was decisive. This led to the second and larger question: if the picture of Hitler given at Nuremberg was substantially accurate, what were the gifts Hitler possessed which enabled him first to secure and then to maintain such power. I determined to reconstruct, so far as I was able, the course of his life from his birth in 1889 to his death in 1945, in the hope that this would enable me to offer an account of one of the most puzzling and remarkable careers in modern history.

The book is cast, therefore, in the form of a historical narrative, interrupted only at one point by a chapter in which I have tried to present a portrait of Hitler on the eve of his greatest triumphs (Chapter 7). I have not attempted to write a history of Germany, nor a study of government and society under the Nazi regime. My theme is not dictatorship, but the dictator, the personal power of one man, although it may be added that for most of the years between 1933 and 1945 this is identical with the most important part of the history of the Third Reich. Up to 1934 the interest lies in the means by which Hitler secured power in Germany. After 1934 the emphasis shifts to foreign policy and ultimately to war, the means by which Hitler sought to extend his power outside Germany. If at times, especially between 1938 and 1945, the figure of the man is submerged beneath the complicated narrative of politics and war, this corresponds to Hitler’s own sacrifice of his private life (which was meagre and uninteresting at the best of times) to the demands of the position he had created for himself. In the last year of his life, however, as his empire begins to crumble, the true nature of the man is revealed again in all its harshness.

No man can sit down to write about the history of his own times — or perhaps of any time — without bringing to the task the preconceptions which spring out of his own character and experience. This is the inescapable condition of the historian’s work, and the present study is no more exempt from these limitations than any other account of the events of the recent past. Nevertheless, I wrote this book without any particular axe to grind or case to argue. I have no simple formula to offer in explanation of the events I have described; few major historical events appear to me to be susceptible of simple explanations. Nor has it been my purpose either to rehabilitate or to indict Adolf Hitler. If I cannot claim the impartiality of a judge, I have not cast myself for the role of prosecuting counsel, still less for that of counsel for the defence. However disputable some of my interpretations may be, there is a solid substratum of fact — and the facts are eloquent enough.

The bibliography printed at the end sets out the sources on which this study is based. In the ten years since this book was first published much new material has appeared which throws light on the history of the Nazi Party and the Third Reich. I have taken the opportunity of a new edition to make a thorough revision of the whole text, taking this material into account and, where it seemed necessary, rewriting in order to make use of it.

The passage of ten years also means a change of perspective: this is more difficult to take into account. I have found no reason to alter substantially the picture I drew of Hitler when the book was first published, although I have not hesitated to change the emphasis where it no longer seemed right. It is in the account of the events leading up to the Second World War that I have made the most complete revision, partly because of the large number of new diplomatic documents that have been published, partly because it is here that my own views have been most affected by the longer perspective in which we are now able to see these events. I am indebted to Mr A. J. P. Taylor’s Origins of the Second World War for stimulating me to re-read the whole of the documentary evidence for Hitler’s foreign policy in the years 1933–9. The fact that I disagree with Mr Taylor in his view of Hitler and his foreign policy — more than ever, now that I have re-read the documents — does not reduce my debt to him for stirring me up to take a critical look at my own account.

Amongst many other writers from whom I have learned since this book was originally published, I should like to mention two other Oxford colleagues: Professor Trevor-Roper whose essay on The Mind of Adolf Hitler convinced me that Hitler’s table talk would repay careful re-reading, and the Warden of St Antony’s (Mr F. W. Deakin), the proofs of whose study of German-Italian relations, The Brutal Friendship, he was kind enough to let me see before publication. Franz Jetzinger’s painstaking researches, recorded in his book Hitler’s Youth (to the English translation of which I contributed a foreword), have enabled me to provide a fuller and more credible account of Hitler’s early years. My other debts, too numerous to acknowledge here, I have indicated in the footnotes.

The bibliography as well as the text has been revised and brought up to date, but the number of publications on the history of these years has forced me to confine it to original sources and first-hand accounts, excluding secondary works except where these print or make use of unpublished material.

In the preface to the original edition I expressed my thanks to the friends who had helped me in a variety of ways, not least to Mr Stanley Hyland for his skill and patience in compiling the index. To these I must now add my thanks to Miss S. Buttar for the trouble she has taken in deciphering and typing the revised manuscript.

My debt to my wife remains the greatest of all, not only for the help she gave me in first undertaking this study, but for her good judgement and encouragement in facing the task of its revision.

ALAN bullock

St Catherine’s College

Oxford

March 1962

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to acknowledge the permission of the Controller H.M. Stationery- Office to quote from publications issued by the British Government. I wish to express my gratitude to the authors, editors, publishers, and agents concerned for permission to quote from the following books: Mein Kampf (translated by James Murphy), and My Part in Germany’s Fight - Hurst & Blackett Ltd. The Speeches of Adolf Hitler (ed. Norman H. Baynes); Documents on International Affairs, 1936 and 1939–46 — Oxford University Press and Royal Institute of International Affairs. Hitler Directs His War (ed. F. Gilbert) — Oxford University Press Inc., New York. The French Yellow Book-, ThePolish White Book; The Last Attempt by B. Dahlerus, and My War Mentories by Gen. Ludendorff — Hutchinson & Co. (Publishers) Ltd. Failure of a Mission by Sir N. Henderson — Raymond Savage Ltd. I Paid Hitler by Fritz Thyssen — Hodder & Stoughton Ltd. Hitler Speaks by Herman Rauschning and The Royal Family of Bayreuth by F. Wagner — Eyre & Spottiswoode (Publishers) Ltd. Hitler as War-Lord by Franz Halder — Putnam & Co. Ltd. Ciano’s Diary, 1939–43 - Wm Heinemann Ltd. Ciano’s Diplomatic Papers - Odhams Press Ltd. Der Führer by K. Heiden — Victor Gollancz Ltd, and the Houghton Mifflin Co. A History of National Socialism by K. Heiden — Methuen & Co. Ltd. The Goebbels Diaries, and Berlin Diary by W. L. Shirer — Hamish Hamilton Ltd. The Last Days of Hitler by H. R. Trevor-Roper, and The Life of Neville Chamberlain by K. Feiling — Macmillan & Co. Ltd. Hitler and I by Otto Strasser — International Press Alliance Corporation. Hitlers Tischgespräche and Statist auf diplomatischer Bühne by Paul Schmidt — Athenäum Verlag. The Second World War, vol. i by Winston S. Churchill — Cassell & Co. Ltd, and the Houghton Mifflin Co.; Farewell Austria by K. von Schuschnigg, and The Other Side of the Hill by B. H. Liddell-Hart — Cassell & Co. Ltd. Defeat in the West by Milton Shulman, and Hitler and His Admirals by A. Martienn- sen — Seeker & Warburg Ltd. To the Bitter End by H. B. Gisevius — Jonathan Cape Ltd, and the Houghton Mifflin Co. Hitler the Pawn by R. Olden — Victor Gollancz Ltd. The Fateful Years by A. François-Poncet — Victor Gollancz Ltd, and Harcourt, Brace & Co., Inc. The Memoirs of Ernst von Weizsäcker - Victor Gollancz Ltd, and the Henry Regnery Co. Panzer Leader by Heinz Guderian — Michael Joseph Ltd. Hitler by K. Heiden — Constable & Co. Ltd. Account Settled by H. Schacht — Weidenfeld & Nicolson Ltd. The Errant Diplomat by O. Dutch — Arnold & Co. The Fall of the German Republic — Allen & Unwin Ltd. The Curtain Falls by Count Bernadotte — Alfred Knopf Inc. The Struggle for Europe by Chester Wilmot, and Rommel by Desmond Young — Collins, Sons and Co. Ltd. Hegel’s Lectures on the Philosophy of History - G. Bell & Sons Ltd. Die deutsche Katastrophe by Fr. Meinecke — Eberhard Brockhaus Verlag. Rätsel um Deutschland by B. Schwertreger — Carl Winter Universitätsverlag. Les Lettres secrètes échangées par Hitler et Mussolini - Éditions du Pavois. Hitler Privat by A. Zoller — Droste Verlag. Austrian Requiem by K. von Schuschnigg — Victor Gollancz Ltd, and G. P. Putnam’s Sons. Blue Print of the Nazi Underground by R. W. M. Kempner — Research Studies of the State College of Washington. ‘Von Schleicher, von Papen et l’avènement de Hitler’ by G. Castellan — Cahiers d’Histoire de la Guerre, Paris. ‘Reichswehr and National Socialism’ by Gordon A. Craig — Political Science Quarterly, N.Y. My New Order (ed. Count Roussy de Sales) — Harcourt, Brace & Co. Inc. Der letzte Monat by Karl Koller — Norbert Wohlgemuth Verlag. Die letzten 30 Tage by Joachim Schultz — Steingrüben Verlag. Rosenberg’s Memoirs - Ziff-Davis Publishing Co. I Knew Hitler by K. Ludecke — Jarrolds, Publishers (London) Ltd, and Hitler’s Words by Gordon W. Prange — Public Affairs Press, Washington. I am grateful to the following authors and publishers for permission to quote additional material in this revised edition: Hitler’s Table Talk - Weidenfeld & Nicolson Ltd. Hitler’s Youth by Franz Jetzinger — Hutchinson & Co. (Publishers) Ltd. Hitler, the Missing Years by Ernst Hanfstängl — Eyre & Spottiswoode (Publishers) Ltd. Hitler was my Friend by Heinrich Hoffmann — Burke Publishing Co. Ltd. The Testament of Adolf Hitler - Cassell & Co. Ltd, and Memoirs by Franz von Papen — André Deutsch Ltd.

Quotations have been made from a number of other books which lack of space prevents me from acknowledging individually. Full acknowledgement is, however, given in the bibliography at the end of the book and in the footnotes, and I am grateful to all those who have granted me permission to quote. In some cases it has proved impossible to locate sources of copyright property. If, therefore, any quotations have been incorrectly acknowledged I hope the persons concerned will accept my apologies.

ABBREVIATIONS

The following abbreviations have been used in the footnotes:

N.D. — Nuremberg Documents presented in evidence at the trial before the International Military Tribunal, Nuremberg, 1945–6. The reference numbers (e.g. 376-PS) are the same in all publications.

N.P. — Nuremberg Proceedings. The Trial of German Major War Criminals. Proceedings of the International Military Tribunal Sitting at Nuremberg. 22 Parts (H.M.S.O., London, 1946–50).

N.C.A. — Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression-, 8 vols. plus 2 supp. vols. (U.S. Govt Printing Office, Washington, 1946–8).

Brit. Doc. — Documents on British Foreign Policy, 1919–39, edited by E. L. Woodward and Rohan Butler (H.M.S.O., London, 1946-).

G.D. — Documents on German Foreign Policy, 1918–45. From the Archives of the German Foreign Ministry (H.M.S.O., London, 1948-).

Baynes — The Speeches of Adolf Hitler, edited by Norman H. Baynes, 2 vols. (Oxford U.P. for R.I.I.A., 1942).

Prange — Hitler’s Words, edited by Gordon W. Prange (American Council on Foreign Relations, Washington, 1944).

BOOK I: PARTY LEADER 1889–1933

CHAPTER ONE: THE FORMATIVE YEARS 1889–1918

I

Adolf Hitler was bom at half past six on the evening of 20 April 1889, in the Gasthof zum Pommer, an inn in the small town of Brannan on the River Inn which forms the frontier between Austria and Bavaria.

The Europe into which he was bom and which he was to destroy gave an unusual impression of stability and permanence at the time of his birth. The Hapsburg Empire, of which his father was a minor official, had survived the storms of the 1860s, the loss of the Italian provinces, defeat by Prussia, even the transformation of the old Empire into the Dual Monarchy of Austria- Hungary. The Hapsburgs, the oldest of the great ruling houses, who had outlived the Turks, the French Revolution, and Napoleon, were a visible guarantee of continuity. The Emperor Franz Joseph had already celebrated the fortieth anniversary of his accession, and had still more than a quarter of a century left to reign.

The three republics Hitler was to destroy, the Austria of the Treaty of St Germain, Czechoslovakia, and Poland, were not yet in existence. Four great empires — the Hapsburg, the Hohenzol- lem, the Romanov, and the Ottoman — ruled over Central and Eastern Europe. The Bolshevik Revolution and the Soviet Union were not yet imagined: Russia was still the Holy Russia of the Tsars. In the summer of this same year, 1889, Lenin, a student of nineteen in trouble with the authorities^ moved with his mother from Kazan to Samara. Stalin was a poor cobbler’s son in Tiflis, Mussolini the six-year-old child of a blacksmith in the bleak Romagna.

Hitler’s family, on both sides, came from the Waldviertel, a poor, remote country district, lying on the north side of the Danube, some fifty miles north-west of Vienna, between the Danube and the frontiers of Bohemia and Moravia. In this countryside of hills and woods, with few towns or railways, lived a peasant population cut off from the main arteries of Austrian life. It was from this Country stock, with its frequent intermarriages, that Hitler sprang. The family name, possibly Czech in origin and spelled in a variety of ways, first appears in the Waldviertel in the first half of the fifteenth century.

The presumed grandfather of the future chancellor, Johann Georg Hiedler, seems to have been a wanderer who never settled down, but followed the trade of a miller in several places in Lower Austria. In the course of these wanderings he picked up with a peasant girl from the village of Strones, Maria Anna Schickl- gruber, whom he married at Dollersheim in May 1842.

Five years earlier, in 1837, Maria had given birth to an illegitimate child, who was known by the name of Alois. According to the accepted tradition the father of this child was Johann Georg Hiedler. However, although Johann Georg married Maria, then forty-seven in 1842, he did not bother to legitimize the child, who continued to be known by his mother’s maiden name of Schicklgruber until he was nearly forty and who was brought up at Spital in the house of his father’s brother, Johann Nepomuk Hiedler.

In 1876 Johann Nepomuk took steps to legitimize the young man who had grown up in his house. He called on the parish priest at Dollersheim and persuaded him to cross out the word ‘illegitimate’ in the register and to append a statement signed by three witnesses that his brother Johann Georg Hiedler hAd accepted the paternity of the child Alois. This is by no means conclusive evidence, and, in all probability, we shall never know for certain who Adolf Hitler’s grandfather, the father of Alois, really was. It has been suggested that he may have been a Jew, without definite proof one way or the other. However this may be, from the beginning of 1877, twelve years before Adolf was born, his father called himself Hitler and his son was never known by any other name until his opponents dug up this long-forgotten village scandal and tried, without justification, to label him with his grandmother’s name of Schicklgruber.[1]

Alois left his uncle’s home at the age of thirteen to serve as a cobbler’s apprentice in Vienna. But he did not take to a trade and by the time he was eighteen he had joined the Imperial Customs Service. From 1855 to 1895 Alois served as a customs officer in Braunau and other towns of Upper Austria. He earned the normal promotion and as a minor state official he had certainly moved up several steps in the social scale from his peasant origins.

As an official in the resplendent imperial uniform of the Haps- burg service Alois Hitler appeared the image of respectability. But his private life belied appearances.

In 1864 he married Anna Glass, the adopted daughter of another customs collector. The marriage was not a success. There were no children and, after a separation, Alois’s wife, who was considerably older and had long been ailing, died in 1883. A month later Alois married a young hotel servant, Franziska Matzelberger, who had already borne him a son out of wedlock and who gave birth to a daughter, Angela, three months after their marriage.

Alois had no better luck with his second marriage. Within a year of her daughter’s birth, Franziska was dead of tuberculosis. This time he waited half a year before marrying again. His third wife, Klara Polzl, twenty-three years younger than himself, came from the village of Spital, where the Hitlers had originated. The two famihes were already related by marriage, and Klara herself was the granddaughter of that Johann Nepomuk Hiedler in whose house Alois had been brought up as a child. She had even lived with Alois and his first wife for a time at Braunau, but at the age of twenty had gone off to Vienna to earn her living as a domestic servant. An episcopal dispensation had to be secured for such a marriage between second cousins, but finally, on 7 January 1885, Alois Hitler married his third wife, and on 17 May of the same year their first child, Gustav, was bom at Braunau.

Adolf was the third child of Alois Hitler’s third marriage. Gustav and Ida, both born before him, died in infancy; his younger brother, Edward, died when he was six; only his younger sister, Paula, born in 1896, lived to grow up. There were also, however, the two children of the second marriage with Franziska, Adolf Hitler’s half-brother Alois, and his half-sister Angela. Angela was the only one of his relations with whom Hitler maintained any sort of friendship. She kept house for him at Berchtesgaden for a time, and it was her daughter, Geli Raubal, with whom Hitler fell in love.

When Adolf was bom his father was over fifty and his mother was under thirty. Alois Hitler was not only very much older than Klara and her children, but hard, unsympathetic, and short- tempered. His domestic life — three wives, one fourteen years older than himself, one twenty-three years younger; a separation; and seven children, including one illegitimate child and two others born shortly after the wedding — suggest a difficult and passionate temperament. Towards the end of his life Alois Hitler seems to have become bitter over some disappointment, perhaps connected with another inheritance. He did not go back to his native district when he retired in 1895 at the age of fifty-eight. Instead he stayed in Upper Austria. From Passau, the German frontier town, where Alois Hitler held his last post, the family moved briefly to Hafeld- am-Traun and Lambach before they settled at Leonding, a village just outside Linz, overlooking the confluence of the Traun and the Danube. Here the retired customs official spent his remaining years, from 1899 to 1903, in a small house with a garden.

Hitler attempted to represent himself in Mein Kampf[2] as the child of poverty and privation. In fact, his father had a perfectly adequate pension and gave the boy the chance of a good education. After five years in primary schools, the eleven-year-old Adolf entered the Linz Realschule in September 1900. This was a secondary school designed to train boys for a technical or commercial career. At the beginning of 1903 Alois Hitler died, but his widow continued to draw a pension and was not left in need. Adolf left the Linz Realschule in 1904 not because his mother was too poor to pay the fees, but because his record at school was so indifferent that he had to accept a transfer to another school at Steyr, where he boarded out and finished his education at the age of sixteen. A year before, on Whit Sunday 1904, he had been confirmed in the Roman Catholic Cathedral at Linz at his mother’s wish.

In Mein Kampf Hitler makes much of a dramatic conflict between himself and his father over his ambition to become an artist.

I did not want to become a civil servant, no, and again no. All attempt on my father’s part to inspire me with love or pleasure in this profession by stories from his own life accomplished the exact opposite.... One day it became clear to me that I would become a painter, an artist.... My father was struck speechless.... ‘Artist! No! Never as long as I live! ...’ My father would never depart from his ‘Never!’ And I intensified my ‘Nevertheless!’[3]

There is no doubt that he did not get on well with his father, but it is unlikely that his ambition to become an artist (he was not fourteen when his father died) had much to do with it. A more probable explanation is that his father was dissatisfied with his , school reports and made his dissatisfaction plain. Hitler glossed over his poor performance at school which he left without securing the customary Leaving Certificate. He found every possible excuse for himself, from illness and his father’s tyranny to artistic ambition and political prejudice. It was a failure which rankled for a long time and found frequent expression in sneers at the ‘educated gentlemen’ with their diplomas and doctorates.

Forty years later, in the sessions at his Headquarters which produced the record of his table talk, Hitler several times recalled the teachers of his schooldays with contempt.

They had no sympathy with youth; their one object was to stuff our brains and turn us into erudite apes like themselves. If any pupil showed the slightest trace of originality, they persecuted him relentlessly, and the only model pupils whom I have ever known have all been failures in later-life.[4]

For their part they seem to have had no great opinion of their most famous pupil. One of his teachers, Dr Eduard Humer, gave this description of the schoolboy Hitler at the time of his trial in 1923:

I can recall the gaunt, pale-faced youth pretty well. He had definite talent, though in a narrow field. But he lacked self-discipline, being notoriously cantankerous, wilful, arrogant, and bad-tempered. He had obvious difficulty in fitting in at school. Moreover he was lazy ... his enthusiasm for hard work evaporated all too quickly. He reacted with ill-concealed hostility to advice or reproof; at the same time, he demanded of his fellow pupils their unqualified subservience, fancying himself in the role of leader....[5]

For only one of his teachers had Hitler anything good to say. In Mein Kampf he went out of his way to praise Dr Leopold Potsch, an ardent German nationalist who, Hitler claimed, had a decisive influence upon him:

There we sat, often aflame with enthusiasm, sometimes even moved to tears.... The national fervour which we felt in our own small way was used by him as an instrument of our education.... It was because I had such a professor that history became my favourite subject.[6]

When Adolf finally left school in 1905, his widowed mother, then forty-six, sold the house at Leonding. With the proceeds of the sale and a monthly pension of 140 kronen, she was not ill provided for and she moved to a small flat, first in the Humboldt- strasse in Linz, then in 1907 to Urfahr, a suburb of Linz. There is no doubt that Hitler was fond of his mother, but she had little control over her self-willed son who refused to settle down to earn his living and spent the next two years indulging in dreams of becoming an artist or architect, living at home, filling his sketch book with entirely unoriginal drawings and elaborating grandiose plans for the rebuilding of Linz. His one friend was August Kubizek, the son of a Linz upholsterer, eight months younger than Hitler, who provided a willing and awe-struck audience for the ambitions and enthusiasms which Hitler poured out in their walks round Linz. Together they visited the theatre where Hitler acquired a life-long passion for Wagner’s opera. Wagnerian romanticism and vast dreams of his own success as an artist and Kubizek’s as a musician filled his mind. He lived in a world of his own, content to let his mother provide for his needs, scornfully refusing to concern himself with such petty mundane affairs as money or a job.

A visit to Vienna in May and June 1906 fired him with enthusiasm for the splendour of its buildings, its art galleries and Opera. On his return to Linz, he was less inclined than ever to find a job for himself. His ambition now was to go back to Vienna and enter the Academy of Fine Arts. His mother was anxious and uneasy but finally capitulated. In the autumn of 1907 he set off for Vienna a second time with high hopes for the future.

His first attempt to enter the Academy in October 1907 was unsuccessful. The Academy’s Classification List contains the entry:

The following took the test with insufficient results or were not admitted....

Adolf Hitler, Braunau a.Inn, 20 April 1889.

German. Catholic. Father, civil servant. 4 classes in Realschule. Few heads. Test drawing unsatisfactory.[7]

The result, he says in Mein Kampf, came as a bitter shock. The Director advised him to try his talents in the direction of architecture: he was not cut out to be a painter. But Hitler refused to admit defeat. Even his mother’s illness (she was dying of cancer) did not bring him back to Linz. He returned only after her death (21 December 1907) in time for the funeral, and in February 1908 went back to Vienna, to resume his life as an ‘art student’.

He was entitled to draw an orphan’s pension and had the small savings left by his mother to fall back on. He was soon joined by his friend Kubizek whom he had prevailed upon to follow his example and seek a place at the Vienna Conservatoire. The two shared a room on the second floor of a house on the Stumper- gasse, close to the West Station, in which there was hardly space for Kubizek’s piano and Hitler’s table.

Apart from Kubizek, Hitler lived a solitary life. He had no other friends. Women were attracted to him, but he showed complete indifference to them. Much of the time he spent dreaming or brooding. His moods alternated between abstracted preoccupation and outbursts of excited talk. He wandered for hours through the streets and parks, staring at buildings which he admired, or suddenly disappearing into the public library in pursuit of some new enthusiasm. Again and again, the two young men visited the Opera and the Burgtheater. But while Kubizek pursued his studies at the Conservatoire, Hitler was incapable of any disciplined or systematic work. He drew little, wrote more and even attempted to compose a music drama on the theme of Wieland the Smith. He had the artist’s temperament without either talent, training, or creative energy.

In July 1908, Kubizek went back to Linz for the summer. A month later Hitler set out to visit two of his aunts in Spltal. When they said good-bye, both young men expected to meet again in Vienna in the autumn. But when Kubizek returned to the capital, he could find no trace of his friend.

In mid-September Hitler had again applied for admission to the Academy of Art. This time, he was not even admitted to the examination. The Director advised him to apply to the School of Architecture, but there entry was barred by his lack of a school Leaving Certificate. Perhaps it was wounded pride that led him to avoid Kubizek. Whatever the reason, for the next five years he chose to bury himself in obscurity.

II

Vienna, at the beginning of 1909, was still an imperial city, capital of an Empire of fifty million souls stretching from the Rhine to the Dniester, from Saxony to Montenegro. The aristrocratic baroque city of Mozart’s time had become a great commercial and industrial centre with a population of two million people. Electric trams ran through its noisy and crowded streets. The massive, monumental buildings erected on the Ringstrasse in the last quarter of the nineteenth century reflected the prosperity and selfconfidence of the Viennese middle class; the factories and poorer streets of the outer districts the rise of an industrial working class. To a young man of twenty, without a home, friends, or resources, it must have appeared a callous and unfriendly city: Vienna was no place to be without money or a job. The four years that now followed, from 1909 to 1913, Hitler himself says, were the unhappiest of his life. They were also in many ways the most important, the formative years in which his character and opinions were given definite shape.

Hitler speaks of his stay in Vienna as ‘five years in which I had to earn my daily bread, first as a casual labourer then as a painter of little trifles.’[8] He writes with feeling of the poor boy from the country who discovers himself out of work. ‘ He loiters about and is hungry. Often he pawns or sells the last of his belongings. His clothes begin to get shabby — with the increasing poverty of his outward appearance he descends to a lower social level.’[9]

A little further on, Hitler gives another picture of his Vienna days. ‘In the years 1909–10 I had so far improved my position that I no longer had to earn my daily bread as a manual labourer. I was now working independently as a draughtsman and painter in water-colours.’ Hitler explains that he made very little money at this, but that he was master of his own time and felt that he was getting nearer to the profession he wanted to take up, that of an architect.

This is a very highly coloured account compared with the evidence of those who knew him then. Meagre though this is, it is enough to make nonsense of Hitler’s picture of himself as a man who had once éamed his living by his hands and then by hard work turned himself into an art student.

According to Konrad Heiden, who was the first man to piece together the scraps of independent evidence, in 1909, Hitler was obliged to give up the furnished room in which he had been living in the Simon Denk Gasse for lack of funds. In the summer he could sleep out, but with the coming of autumn he found a bed in a doss-house behind Meidling Station. At the end of the year, Hitler moved to a hostel for men started by a charitable foundation at 27 Meldemannstrasse, in the 20th district of Vienna, over on the other side of the city, close to the Danube. Here he lived, for the remaining three years of his stay in Vienna, from 1910 to 1913.

A few others who knew Hitler at this time have been traced and questioned, amongst them a certain Reinhold Hanisch, a tramp from German Bohemia, who for a time knew Hitler well. Hanisch’s testimony is partly confirmed by one of the few pieces of documentary evidence which have been discovered for the early years. For in 1910, after a quarrel, Hitler sued Hanisch for cheating him of a small sum of money, and the records of the Vienna police court have been published, including (besides Hitler’s own affidavit) the statement of Siegfried Loffner, another inmate of the hostel in Meldemannstrasse who testified that Hanisch and Hitler always sat together and were friendly.

Hanisch describes his first meeting with Hitler in the doss-house in Meidling in 1909. ‘On the very first day there sat next to the bed that had been allotted to me a man who had nothing on except an old tom pair of trousers — Hitler. His clothes were being cleaned of lice, since for days he had been wandering about without a roof and in a terribly neglected condition.’[10]

Hanisch and Hitler joined forces in looking for work; they beat carpets, carried bags outside the West Station, and did casual labouring jobs, on more than one occasion shovelling snow off the streets. As Hitler had no overcoat, he felt the cold badly. Then Hanisch had a better idea. He asked Hitler one day what trade he had learned. ‘ “I am a painter”, was the answer. Thinking that he was a house decorator, I said that it would surely be easy to make money at this trade. He was offended and answered that he was not that sort of painter, but an academician and an artist.’ When the two moved to the Meldemannstrasse, ‘we had to think out better ways of making money. Hitler proposed that we should fake pictures. He told me that already in Linz he had painted small landscapes in oil, had roasted them in an oven until they had become quite brown and had several times been successful in selling these pictures to traders as valuable old masters.’ This sounds highly improbable, but in any case Hanisch, who had registered under another name as Walter Fritz, was afraid of the police. ‘ So I suggested to Hitler that it would be better to stay in an honest trade and paint postcards. I myself was to sell the painted cards, we decided to work together and share the money we earned.’[11]

Hitler had enough money to buy a few cards, ink and paints. With these he produced little copies of views of Vienna, which Hanisch peddled in taverns and fairs, or to small traders who wanted something to fill their empty picture frames. In this way they made enough to keep them until, in the summer of 1910, Hanisch sold a copy which Hitler had made of a drawing of the Vienna Parliament for ten crowns. Hitler, who was sure it was worth far more — he valued it at fifty in his statement to the police — was convinced he had been cheated. When Hanisch failed to return to the hostel, Hitler brought a lawsuit against him which ended in Hanisch spending a week in prison and the break-up of their partnership.

This was in August 1910. For the remaining four years before the First World War, first in Vienna, later in Munich, Hitler continued to eke out a living in the same way. Some of Hitlei’s drawings, mostly stiff, lifeless copies of buildings in which his attempts to add human figures are a failure, were still to be found in Vienna in the 1930s, when they had acquired the value of collectors’ pieces. More often he drew posters and crude advertisements for small shops — Teddy Perspiration Powder, Santa Claus selling coloured candles, or St Stefan’s spire rising over a mountain of soap, with the signature ‘A. Hitler’ in the corner. Hitler himself later described these as years of great loneliness, in which his only contacts with other human beings were in the hostel where he continued to live and where, according to Hanisch, ‘only tramps, drunkards, and such spent any time’.

After their quarrel Hanisch lost sight of Hitler, but he gives a description of Hitler as he knew him in 1910 at the age of twenty- one. He wore an ancient black overcoat, which had been given him by an old-clothes dealer in the hostel, a Hungarian Jew named Neumann, and which reached down over his knees. From under a greasy, black derby hat, his hair hung long over his coat collar. His thin and hungry face was covered with a black beard above which his large staring eyes were the one prominent feature. Altogether, Hanisch adds, ‘an apparition such as rarely occurs among Christians’.[12]

From time to time Hitler had received financial help from his aunt in Linz, Johanna Pólzl and, when she died in March 1911, it seems likely that he was left some small legacy. In May of that year his orphan’s pension was stopped, but he still avoided any regular work.

Hanisch depicts him as lazy and moody, two characteristics which were often to reappear. He disliked regular work. If he earned a few crowns, he refused to draw for days and went off to a café to eat cream cakes and read newspapers. He had none of the common vices. He neither smoked nor drank and, according to Hanisch, was too shy and awkward to have any success with women. His passions were reading newspapers and talking poli tics. ‘Over and over again,’ Hanisch recalls, ‘there were days on which he simply refused to work. Then he would hang around night shelters, living on the bread and soup that he got there, and discussing politics, often getting involved in heated controversies.’[13]

When he became excited in argument he would shout and wave his arms until the others in the room cursed him for disturbing them, or the porter came in to stop the noise. Sometimes people laughed at him, at other times they were oddly impressed. ‘One evening,’ Hanish relates, ‘Hitler went to a cinema where Keller- mann’s Tunnel was being shown. In this piece an agitator appears who rouses the working masses by his speeches. Hitler almost went crazy. The impression it made on him was so strong that for days afterwards he spoke of nothing except the power of the spoken word.’[14] These outbursts of violent argument and denunciation alternated with moods of despondency.

Everyone who knew him was struck by the combination of ambition, energy, and indolence in Hitler. Hitler was not only desperately anxious to impress people but was full of clever ideas for making his fortune and fame — from water-divining to designing an aeroplane. In this mood he would talk exuberantly and begin to spend the fortune he was to make in anticipation, but he was incapable of the application and hard work needed to carry out his projects. His enthusiasm would flag, he would relapse into moodiness and disappear until he began to hare off after some new trick or short cut to success. His intellectual interests followed the same pattern. He spent much time in the public library, but his reading was indiscriminate and unsystematic. Ancient Rome, the Eastern religions, Yoga, Occultism, Hypnotism, Astrology, Protestantism, each in turn excited his interest for a moment. He started a score of jobs but failed to make anything of them and relapsed into the old hand-to-mouth existence, living by expedients and little spurts of activity, but never settling down to anything for long.

As time passed these habits became ingrained, and he became more eccentric, more turned in on himself. He struck people as ‘queer’, unbalanced. He gave rein to his hatreds — against the Jews, the priests, the Social Democrats, the Hapsburgs — without restraint. The few people with whom he had been friendly became tired of him, of his strange behaviour and wild talk. Neumann, the Jew, who had befriended him, was offended by the violence of his anti-Semitism; Kanya, who kept the hostel for men, thought him one of the oddest customers with whom he had had to deal. Yet these Vienna days stamped an indelible impression on his character and mind. ‘During these years a view of life and a definite outlook on the world took shape in my mind. These became the granite basis of my conduct at that time. Since then I have extended that foundation very little, I have changed nothing in it ... Vienna was a hard school for me, but it taught me the most profound lessons of my life.’[15] However pretentiously expressed, this is true. It is time to examine what these lessons were.

III

The idea of struggle is as old as life itself, for life is only preserved because other living things perish through struggle.... In this struggle, the stronger, the more able, win, while the less able, the weak, lose. Struggle is the father of all things.... It is not by the principles of humanity that man lives or is able to preserve himself above the animal world, but solely by means of the most brutal struggle.... If you do not fight for life, then life will never be won.[16]

This is the natural philosophy of the doss-house. In this struggle any trick or ruse, however unscrupulous, the use of any weapon or opportunity, however treacherous, are permissible. To quote another typical sentence from Hitler’s speeches: ‘Whatever goal man has reached is due to his originality plus his brutality.’[17] Astuteness; the ability to lie, twist, cheat and flatter; the elimination of sentimentality or loyalty in favour of ruthlessness, these were the qualities which enabled men to rise; above all, strength of will. Such were the principles which Hitler drew from his years in Vienna. Hitler never trusted anyone; he never committed himself to anyone, never admitted any loyalty. His lack of scruple later took by surprise even those who prided themselves on their unscrupulousness. He learned to lie with conviction and dissemble with candour. To the end he refused to admit defeat and still held to the belief that by the power of will alone he could transform events.

Distrust was matched by contempt. Men were moved by fear, greed, lust for power, envy, often by mean and petty motives. Politics, Hitler was later to conclude, is the art of knowing how to use these weaknesses for one’s own ends. Already in Vienna Hitler admired Karl Lueger, the famous Burgomaster of Vienna and leader of the Christian Social Party, because ‘he had a rare gift of insight into human nature and was very careful not to take men as something better than they were in reality.’[18] He felt particular contempt for the masses — ‘everybody who properly estimates the political intelligence of the masses can easily see that this is not sufficiently developed to enable them to form general political judgements on their own account.’[19] Here again was material to be manipulated by a skilful politician. As yet Hitler had no idea of making a political career, but he spent a great deal of time reading and arguing politics, and what he learned was an important part of his political apprenticeship.

In the situation in which he found himself in Vienna, Hitler clung tenaciously to the conviction that he was better than the people with whom he was now driven to associate. ‘Those among whom I passed my younger days belonged to the petit bourgeois class.... The ditch which separated that class, which is by no means well-off, from the manual labouring class is often deeper than people think. The reason for this division, which we may almost call enmity, lies in the fear that dominates a social group which has only just risen above the level of the manual labourer — a fear lest it may fall back into its old condition or at least be classed with the labourers....’[20]

Although Hitler writes in Mein Kampf of the misery in which the Vienna working class lived at this time, it is evident from every line of the account that these conditions produced no feeling of sympathy in him. ‘I do not know which appalled me most at that time: the economic misery of those who were then my companions, their crude customs and morals, or the low level of their intellectual culture.’[21] Least of all did he feel any sympathy with the attempts of the poor and the exploited to improve their position by their own efforts. Hitler’s hatred was directed not so much against the rogues, beggars, bankrupt business men, and déclassé ‘gentlemen’ who were the flotsam and jetsam drifting in and out of the hostel in the Meldemannstrasse, as against the working men who belonged to organizations like the Social Democratic Party and the trade unions and who preached equality and the solidarity of the working classes. It was these, much more than the former, who threatened his claim to superiority. Solidarity was a virtue for which Hitler had no use. He passionately refused to join a trade union, or in any way to accept the status of a working man.

The whole ideology of the working-class movement was alien and hateful to him:

All that I heard had the effect of arousing the strongest antagonism in me. Everything was disparaged — the nation because it was held to be an invention of the capitalist class (how often I had to listen to that phrase!); the Fatherland, because it was held to be an instrument in the hand of the bourgeoisie for the exploitation of the working masses; the authority of the law, because this was a means of holding down the proletariat; religion, as a means of doping the people, so as to exploit them afterwards ; morality, as a badge of stupid and sheepish docility. There was nothing that they did not drag in the mud.... Then I asked myself: are these men worthy to belong to a great people? The question was profoundly disturbing; for if the answer were‘Yes’, then the struggle to defend one’s nationality is no longer worth all the trouble and sacrifice we demand of our best elements if it be in the interest of such a rabble. On the other hand, if the answer had to be ‘ No ’, then our nation is poor indeed in men. During these days of mental anguish and deep meditation I saw before my mind the ever-increasing and menacing army of people who could no longer be reckoned as belonging to their own nation.[22]

Hitler found the solution of his dilemma in the ‘ discovery ’ that the working men were the victims of a deliberate system for corrupting and poisoning the popular mind, organized by the Social Democratic Party’s leaders, who cynically exploited the distress of the masses for their own ends. Then came the crowning revelation: ‘I discovered the relations existing between this destructive teaching and the specific character of a people, who up to that time had been almost unknown to me. Knowledge of the Jews is the only key whereby one may understand the inner nature and the real aims of Social Democracy.’[23]

There was nothing new in Hitler’s anti-Semitism; it was endemic in Vienna, and everything he ever said or wrote about the Jews is only a reflection of the anti-Semitic periodicals and pamphlets he read in Vienna before 1914. In Linz there had been very few Jews — ‘I do not remember ever having heard the word at home during my father’s lifetime.’ Even in Vienna Hitler had at first been repelled by the violence of the anti-Semitic Press. Then, ‘one day, when passing through the Inner City, I suddenly encountered a phenomenon in a long caftan and wearing black sidelocks. My first thought was: is this a Jew? They certainly did not have this appearance in Linz, I watched the man stealthily and cautiously, but the longer I gazed at this strange countenance and examined it section by section, the more the question shaped itself in my brain: is this a German? I turned to books for help in removing my doubts. For the first time in my life I bought myself some anti-Semitic pamphlets for a few pence.’[24]

The language in which Hitler describes his discovery has the obscene taint to be found in most anti-Semitic literature: ‘Was there any shady undertaking, any form of foulness, especially in cultural life, in which at least one Jew did not participate? On putting the probing knife carefully to that kind of abscess one immediately discovered, like a maggot in a putrescent body, a little Jew who was often blinded by the sudden light.’[25]

Especially characteristic of Viennese anti-Semitism was its sexuality. ‘The black-haired Jewish youth lies in wait for hours on end, satanically glaring at and spying on the unsuspicious girl whom he plans to seduce, adulterating her blood and removing her from the bosom of her own people.... The Jews were responsible for bringing negroes into the Rhineland with the ultimate idea of bastardizing the white race which they hate and thus lowering its cultural and political level so that the Jew might dominate.’[26] Elsewhere Hitler writes of ‘the nightmare vision of the seduction of hundreds of thousands of girls by repulsive, crooked-legged Jew bastards ’. More than one writer has suggested that some sexual experience — possibly the contraction of venereal disease — was at the back of Hitler’s anti-Semitism.

In all the pages which Hitler devotes to the Jews in Mein Kampf he does not bring forward a single fact to support his wild assertions. This was entirely right, for Hitler’s anti-Semitism bore no relation to facts, it was pure fantasy: to read these pages is to enter the world of the insane, a world peopled by hideous and distorted shadows. The Jew is no longer a human being, he has become a mythical figure, a grimacing, leering devil invested with infernal powers, the incarnation of evil, into which Hitler projects all that he hates and fears — and desires. Like all obsessions, the Jew is not a partial, but a total explanation. The Jew is everywhere, responsible for everything — the Modernism in art and music Hitler disliked; pornography and prostitution; the antinational criticism of the Press; the exploitation of the masses by Capitalism, and its reverse, the exploitation of the masses by Socialism; not least for his own failure to get on. ‘Thus I finally discovered who were the evil spirits leading our people astray.... My love for my own people increased correspondingly. Considering the satanic skill which these evil counsellors displayed, how could their unfortunate victims be blamed? ... The more I came to know the Jew, the easier it was to excuse the workers.’[27]

Behind all this, Hitler soon convinced himself, lay a Jewish world conspiracy to destroy and subdue the Aryan peoples, as an act of revenge for their own inferiority. Their purpose was to weaken the nation by fomenting social divisions and class conflict, and by attacking the values of race, heroism, struggle, and authoritarian rule in favour of the false internationalist, humanitarian, pacifist, materialist ideals of democracy. ‘The Jewish doctrine of Marxism repudiates the aristocratic principle of nature and substitutes for it and the eternal privilege of force and energy, numerical mass and its dead weight. Thus it denies the individual worth of the human personality, impugns the teaching that nationhood and race have a primary significance, and by doing this takes away the very foundations of human existence and human civilization.’[28]

In Hitler’s eyes the inequality of individuals and of races was one of the laws of Nature. This poor wretch, often half-starved, without a job, family, or home, clung obstinately to any belief that would bolster up the claim of his own superiority. He belonged by right, he felt, to the Herrenmenschen. To preach equality was to threaten the belief which kept him going, that he was different from the labourers, the tramps, the Jews, and the Slavs with whom he rubbed shoulders in the streets.

Hitler bad no use for any democratic institution: free speech, free press, or parliament. During the earlier part of his time in Vienna he had sometimes attended the sessions of the Reichsrat, the representative assembly of the Austrian half of the Empire, and he devotes fifteen pages of Mein Kampf to expressing his scorn for what he saw. Parliamentary democracy reduced government to political jobbery, it put a premium on mediocrity and was inimical to leadership, encouraged the avoidance of responsibility, and sacrificed decisions to party compromises. ‘The majority represents not only ignorance but cowardice.... The majority can never replace the man.’[29]

All his life Hitler was irritated by discussion. In the arguments into which he was drawn in the hostel for men or in cafés he showed no self-control in face of contradiction or debate. He began to shout and shower abuse on his opponents, with an hysterical note in his voice. It was precisely the same pattern of uncontrolled behaviour he displayed when he came to supreme power and found himself crossed or contradicted. This authoritarian temper developed with the exercise of power, but it was already there in his twenties, the instinct of tyranny.

Belief in equality between races was an even greater offence in Hitler’s eyes than belief in equality between individuals. He had already become a passionate German nationalist while still at school. In Austria-Hungary this meant even more than it meant in Germany itself, and the fanatical quality of Hitler’s nationalism throughout his life reflects his Austrian origin.

For several hundred years the Germans of Austria played the leading part in the politics and cultural life of Central Europe. Until 1871 there had been no single unified German state. Germans had lived under the rule of a score of different states — Bavaria, Prussia, Württemberg, Hanover, Saxony — loosely grouped together in the Holy Roman Empire, and then, after 1815, in the German Federation. Both in the Empire and in the Federation Austria had enjoyed a traditional hegemony as the leading German Power. In the middle of the nineteenth century it was still Vienna, not Berlin, which ranked as the first of German cities. Moreover, the Hapsburgs not only enjoyed a pre-eminent position among the German states, but also ruled over wide lands inhabited by many different peoples.

On both counts the Germans of Vienna and the Austrian lands, who identified themselves with the Hapsburgs, looked on themselves as an imperial race, enjoying a position of political privilege and boasting of a cultural tradition which few other peoples in Europe could equal. From the middle of the nineteenth century, however, this position was first challenged and then undermined.

In place of the German Federation a unified German state was established by Prussia, from which the Germans of Austria were excluded. Prussia defeated Austria at Sadowa in 1866, and thereafter the new German Empire with its capital at Berlin increasingly took the place hitherto occupied by Austria and Vienna as the premier German state.

At the same time the pre-eminence of the Germans within the Hapsburg Empire itself was challenged, first by the Italians, who secured their independence in the 1860s; then by the Magyars of Hungary, to whom equality had to be conceded in 1867; finally by the Slav peoples. The growth of the demand for equal rights among the Slavs and other subject peoples was slower than with the Magyars, and uneven in its development. But especially in Bohemia and Moravia, where the most advanced of the Slav peoples, the Czechs, lived, it was bitterly resented by the Germans and fiercely resisted. This conflict of the nationalities dominated Austrian politics from 1870 to the break-up of the Empire in 1918.

In this conflict Hitler had no patience with concessions. The Germans should rule the Empire, at least the Austrian half of it, with an authoritarian and centralized administration; there should be only one official language — German — and the schools and universities should be used ’to inculcate a feeling of common citizenship’, an ambiguous expression for Germanization. The representative assembly of the Reichsrat, in which the Germans (only thirty-five per cent of the population of Austria) were permanently outnumbered, should be suppressed. Here was a special reason for hatred of the Social Democratic Party, which refused to follow the nationalist lead of the Pan-Germans, and instead fostered class conflicts at the expense of national unity.

In September 1938, at the time of the Sudeten crisis, Hitler said in a newspaper interview: ‘ The Czechs have none of the characteristics of a nation, whether from the standpoint of ethnology, strategy, economics, or language. To set an intellectually inferior handful of Czechs to rule over minorities belonging to races like the Germans, Poles, Hungarians, with a thousand years of culture behind them, was a work of folly and ignorance.’[30] This was a view which Hitler first learned in Austria before 1914, and indeed the whole Czech crisis of 1938–9 was part of an old quarrel rooted deep in the history of the Hapsburg Empire from which Hitler came.

The influence of his Austrian origins is even more obvious in the case of the Anschluss, the incorporation of Austria in the German Reich, which Hitler carried out at the beginning of 1938. Long before 1914 extreme German nationalists in Austria had begun to talk openly of the break-up of the Hapsburg Empire and the reunion of the Germans of Austria with the German Empire. Habsburg policy in face of the national conflicts which divided their peoples had been uncertain and vacillating. To the PanGerman extremists this appeared as a betrayal of the German cause. In Mein KampfyAitXex asked:

How could one remain a faithful subject of the House of Hapsburg, whose past history and present conduct proved it to be ready ever and always to betray the interests of the German people? ... The German Austrian had come to feel in the very depth of his being that the historical mission of the House of Hapsburg had come to an end.... Therefore I welcomed every movement that might lead towards the final disruption of that impossible State which had decreed that it would stamp out the German character in ten millions of people, this Babylonian Empire. That would mean the liberating of my German Austrian people and only then would it become possible for them to be reunited to the Motherland,[31]

When Hitler returned to Vienna after the Anschluss had been carried out and the dream of a Greater Germany which Bismarck had rejected had at last been fulfilled, he said with a touch of genuine exultation: ‘I believe that it was God’s will to send a boy from here into the Reich, to let him grow up and to raise him to be the leader of the nation so that he could lead back his homeland into the Reich.’[32] In March 1938, the Austrian-born Chancellor of Germany reversed the decision which Bismarck, a Prussian-born Chancellor, had made in the 1860s when he excluded the German Austrians from the new German Reich. The Babylonian captivity was at an end.

IV

The political ideas and programme which Hitler picked up in Vienna were entirely unoriginal. They were the clichés of radical and Pan-German gutter politics, the stock-in-trade of the antisemitic and nationalist Press. The originality was to appear in Hitler’s grasp of how to create a mass-movement and secure power on the basis of these ideas. Here, too, although he took no active part in politics, he owed much to observations drawn from his years in Vienna.

The three parties which interested Hitler were the Austrian Social Democrats, Georg von Schönerer’s Pan-German Nationalists, and Karl Lueger’s Christian Social Party.

From the Social Democrats Hitler derived the idea of a mass party and mass propaganda. In Mein Kampf he describes the impression made on him when ‘ I gazed on the interminable ranks, four abreast, of Viennese workmen parading at a mass demonstration. I stood dumb-founded for almost two hours, watching this enormous human dragon which slowly uncoiled itself before me.’[33]

Studying the Social Democratic Press and Party speeches, Hitler reached the conclusion that: ‘the psyche of the broad masses is accessible only to what is strong and uncompromising.... The masses of the people prefer the ruler to the suppliant and are filled with a stronger sense of mental security by a teaching that brooks no rival than by a teaching which offers them a liberal choice. They have very little idea of how to make such a choice and thus are prone to feel that they have been abandoned. Whereas they feel very little shame at being terrorized intellectually and are scarcely conscious of the fact that their freedom as human beings is impudently abused.... I also came to understand that physical intimidation has its significance for the mass as well as the individual.... For the successes which are thus obtained are taken by the adherents as a triumphant symbol of the righteousness of their own cause; while the beaten opponent very often loses faith in the effectiveness of any further resistance.’[34]

From Schönerer Hitler took his extreme German Nationalism, his anti-Socialism, his anti-Semitism, his hatred of the Hapsburgs and his programme of reunion with Germany. But he learned as much from the mistakes which Schönerer and the Nationalists committed in their political tactics. For Schönerer, Hitler believed, made three cardinal errors.

The Nationalists failed to grasp the importance of the social problem, directing their attention to the middle classes and neglecting the masses. They wasted their energy in a parliamentary struggle and failed to establish themselves as the leaders of a great movement. Finally they made the mistake of attacking the Catholic Church and split their forces instead of concentrating them. ‘The art of leadership,’ Hitler wrote, ‘consists of consolidating the attention of the people against a single adversary and taking care that nothing will split up this attention.... The leader of genius must have the ability to make different opponents appear as if they belonged to one category.’[35]

It was in the third party, the Christian Socialists, and their remarkable leader, Karl Lueger, that Hitler found brilliantly displayed that grasp of political tactics, the lack of which hampered the success of the Nationalists. Lueger had made himself Burgomaster of Vienna — in many ways the most important elective post in Austria — and by 1907 the Christian Socialists under his leadership had become the strongest party in the Austrian parliament. Hitler saw much to criticize in Lueger’s programme. His anti-Semitism was based on religious and economic, not on racial, grounds (T decide who is a Jew,’ Lueger once said), and he rejected the intransigent nationalism of the Pan-Germans, seeking to preserve and strengthen the Hapsburg State with its mixture of nationalities. But Hitler was prepared to overlook even this in his admiration for Lueger’s leadership.

The strength of Lueger’s following lay in the lower middle class of Vienna, the small shopkeepers, business men and artisans, the petty officials and municipal employees. ‘He devoted the greatest part of his political activity’, Hitler noted, ‘to the task of winning over those sections of the population whose existence was in danger.’[36]

Years later Hitler was to show a brilliant appreciation of the importance of these same classes in German politics. From the beginning Lueger understood the importance both of social problems and of appealing to the masses. ‘Their leaders recognized the value of propaganda on a large scale and they were veritable virtuosos in working up the spiritual instincts of the broad masses of their electorate.’[37]

Finally, instead of quarrelling with the Church, Lueger made it his ally and used to the full the traditional loyalty to crown and altar. In a sentence which again points forward to his later career, Hitler remarks: ‘He was quick to adopt all available means for winning the support of long-established institutions, so as to be able to derive the greatest possible advantage for his movement from those old sources of power.’[38]

Hitler concludes his comparison of Schbnerer’s and Lueger’s leadership with these words:

If the Christian Socialist Party, together with its shrewd judgement in regard to the worth of the popular masses, had only judged rightly also on the importance of the racial problem — which was properly grasped by the Pan-German movement — and if this party had been really nationalist; or if the Pan-German leaders, on the other hand, in addition to their correct judgement of the Jewish problem and of the national idea, had adopted the practical wisdom of the Christian-Socialist Party, and particularly their attitude towards Socialism — then a movement would have developed which might have successfully altered the course of German destiny.[39]

Here already is the idea of a party which should be both national and socialist. This was written a dozen years after he had left Vienna, and it would be an exaggeration to suppose that Hitler had already formulated clearly the ideas he set out in Mein Kampfin the middle of the 1920s. None the less the greater part of the experience on which he drew was already complete when he left Vienna, and to the end Hitler bore the stamp of his Austrian origins.

V

Hitler left Vienna for good in the spring of 1913. He was then twenty-four years old, awkward, moody and reserved, yet nursing a passion of hatred and fanaticism which from time to time broke out in a torrent of excited words. Years of failure had laid up a deep store of resentment in him, but had failed to weaken the conviction of his own superiority.

In Mein Kampf Hitler speaks of leaving Vienna in the spring of 1912, but the Vienna police records report him as living there until May 1913. Hitler is so careless about dates and facts in his book that the later date seems more likeiy to be correct. Hitler is equally evasive about the reasons which led him to leave. He writes in general terms of his dislike of Vienna and the state of affairs in Austria:

My inner aversion to the Hapsburg State was increasing daily.... This motley of Czechs, Poles, Hungarians, Ruthenians, Serbs and Croats, and always the bacillus which is the solvent of human society, the Jew, here and there and everywhere — the whole spectacle was repugnant to me.... The longer I lived in that city the stronger became my hatred for the promiscuous swarm of foreign peoples which had begun to batten on that old nursery ground of German culture. All these considerations intensified my yearning to depart for that country for which my heart had been secretly longing since the days of my youth. I hoped that one day I might be able to make my mark as an architect and that I could devote my talents to the service of my country. A final reason was that I hoped to be among those who lived and worked in that land from which the movement should be launched, the object of which would be the fulfilment of what my heart had always longed for, the reunion of the country in which I was born with our common fatherland, the German Empire.[40]

All this, we may be sure, is true enough, but it gives no specific reason why, on one day rather than another, Hitler decided to go to the station, buy a ticket and at last leave the city he had come to detest.

The most likely explanation is that Hitler was anxious to escape military service, for which he had failed to report each year since 1910. Inquiries were being made by the police, and he may have found it necessary to slip over the frontier. Eventually he was located in Munich and ordered to present himself for examination at Linz. The correspondence between Hitler and the authorities at Linz has been published.[41] Hitler’s explanation, with its half truths, lies, evasions and its characteristic mixture of the brazen and the sly, ranks as the first of a long series of similar ‘explanations’ with which the world was to become only too familiar. Hitler denied that he had left Vienna to avoid conscription, and asked, on account of his lack of means, to be allowed to report at Salzburg, which was nearer to Munich than Linz. His request was agreed to, and he duly presented himself for examination at Salzburg on 5 February 1914. He was rejected for military or auxiliary service on the grounds of poor health, and the incident was closed. But after the Germans marched into Austria in 1938 a very thorough search was made in Linz for the records connected with Hitler’s military service and Hitler was furious when the Gestapo failed to discover them.

It was in the May of 1913 that Hitler moved to Munich, across the German frontier. He found lodgings with a tailor’s family, by the name of Popp, which lived in the Schleissheimerstrasse, a poor quarter near the barracks. In retrospect, Hitler described this as ‘by far the happiest time of my life.... I came to love that city more than any other place known to me. A German city. How different from Vienna.’[42]

It may be doubted if this represented Hitler’s feelings at the time. His life followed much the same pattern as before. His dislike of hard work and regular employment had by now hardened into a habit. He made a precarious living by drawing advertisements and posters, or peddling sketches to dealers. He was perpetually short of money. Despite his enthusiasm for the architecture and paintings of Munich, he was not a step nearer making a career than he had been on the day when he was turned down by the Vienna Academy. In his new surroundings he appears to have lost touch with his relations, and to have made few, if any, friends.

The shadowy picture that emerges from the reminiscences of the few people who knew him in Munich is once again of a man living in his own world of fantasy. He gives the same impression of eccentricity and lack of balance, brooding and muttering to himself over his extravagant theories of race, anti-Semitism, and anti-Marxism, then bursting out in wild, sarcastic diatribes. He spent much time in cafes and beer-cellars, devouring the newspapers and arguing about politics. Frau Popp, his landlady, speaks of him as a voracious reader, an impression Hitler more than once tries to create in Mein Kampf. Yet nowhere is there any indication of the works he read. Nietzsche, Houston Stewart Chamberlain, Schopenhauer, Wagner, Gobineau? Perhaps. But Hitler’s own comment on reading is illuminating. ‘Reading had probably a different significance for me from that which it has for the average run of our so-called “intellectuals.” I know people who read interminably, book after book, from page to page.... Of course they “know” an immense amount, but ... they have not the faculty of distinguishing between what is useful and useless in a book; so that they may retain the former in their minds and if possible skip over the latter.... Reading is not an end in itself, but a means to an end.... One who has cultivated the art of reading will instantly discern, in a book or journal or pamphlet, what ought to be remembered because it meets one’s personal needs or is of value as general knowledge.’[43]

This is a picture of a man with a closed mind, reading only to confirm what he already believes, ignoring what does not fit in with his preconceived scheme. ‘Otherwise,’ Hitler says, ‘only a confused jumble of chaotic notions will result from all this reading.... Such a person never succeeds in turning his knowledge to practical account when the opportune moment arrives; for his mental equipment is not ordered with a view to meeting the demands of everyday life.’[44] Hitler was speaking the truth when he said: ‘Since then (i.e. since his days in Vienna) I have extended that foundation very little, and I have changed nothing in it.’[45]

Hitler retained his passionate interest in politics. He was indignant at the ignorance and indifference of people in Munich to the situation of the Germans in Austria. Since 1879 the two states, the German Empire and the Hapsburg Monarchy, had been bound together by a military alliance, which remained the foundation of German foreign policy up to the defeat of 1918. Hitler felt that this predisposed most Germans to refuse to listen to the exaggerated accounts he gave of the ‘desperate’ position of the German Austrians in the conflict of nationalities within the Monarchy.

Hitler’s objection to the alliance of Germany and Austria was twofold. It crippled the Austrians in their resistance to what he regarded as the deliberate anti-German policy of the Hapsburgs. At the same time, for Germany herself it represented a dangerous commitment to the support of a state which, he was convinced, was on the verge of disintegration. Hitler would have agreed with the view expressed by Ludendorff in his memoirs: ‘A Jew in Radom once said to one of my officers that he could not understand why so strong and vital a body as Germany should ally itself with a corpse. He was right.’[46]

When Franz Ferdinand was assassinated by Serbian students, at Sarajevo on 28 June 1914, Hitler’s first reaction was confused. For, in his eyes, it was Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Hapsburg throne, who had been more responsible than anyone else for that policy of concessions to the Slav peoples of the Monarchy which roused the anger of the German nationalists in Austria. But, as events moved towards the outbreak of a general European war, Hitler brushed aside his doubts. At least Austria would be

compelled to fight, and could not, as he had always feared, betray her ally Germany. In any case, ‘I believed that it was not a case of Austria fighting to get satisfaction from Serbia, but rather a case of Germany fighting for her own existence — the German nation for its own to be or not to be, for its freedom and for its future.... For me, as for every other German, the most memorable period of my life now began. Face to face with that mighty struggle all the past fell away into oblivion.’[47]

There were other, deeper and more personal reasons for his satisfaction. War meant to Hitler something more than the chance to express his nationalist ardour, it offered the opportunity to slough off the frustration, failure, and resentment of the past six years. Here was an escape from the tension and dissatisfaction of a lonely individuality into the excitement and warmth of a close, disciplined, collective life, in which he could identify himself with the power and purpose of a great organization. ‘The war of 1914’, he wrote in Mein Kampf, ‘was certainly not forced on the masses; it was even desired by the whole people’ — a remark which illustrates at least this man’s state of mind. ‘ For me these hours came as a deliverance from the distress that had weighed upon me during the days of my youth. I am not ashamed to acknowledge today that I was carried away by the enthusiasm of the moment and that I sank down upon my knees and thanked Heaven out of the fullness of my heart for the favour of having been permitted to live in such a time.’[48]

On 1 August Hitler was in the cheering, singing crowd which gathered on the Odeons Platz to listen to the proclamation declaring war. In a chance photograph that has been preserved his face is clearly recognizable, his eyes excited and exultant; it is the face of a man who has come home at last. Two days later he addressed a formal petition to King Ludwig III of Bavaria, asking to be allowed to volunteer, although of Austrian nationality, for a Bavarian regiment. The reply granted his request. ‘I opened the document with trembling hands; no words of mine can describe the satisfaction I felt.... Within a few days I was wearing that uniform which I was not to put off again for nearly six years.’[49]

Together with a large number of other volunteers he was enrolled in the 1st Company of the 16th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment, known from its original commander as the List Regiment. Another volunteer in the same regiment was Rudolf Hess; the regimental clerk was a Sergeant-major Max Amann, later to become business manager of the Nazi Party’s paper and of the Party publishing house. After a period of initial training in Munich, they spent several weeks at Lechfeld, and then, on 21 October 1914, entrained for the Front.