Barre Toelken

The Dynamics of Folklore

Introduction: Into Folkloristics with Gun and Camera

The Folk Group: Environment for Esoteric Dynamics

Esoteric Recognition of Dynamics

Walkaway: The Independent Logger

Pranks: Inducting the Greenhorn

Names and Expressions: Folk Poetry in the Woods

Esoteric Eating: Japanese Americans

4. Dimensions of the Folk Event

Understanding the Inventory: From Within and Without

A Check List: Apparent and Esoteric Dimensions

The Beginnings of Questions (A Summary)

An Ethnic Event: The Japanese New Year

Induced or Recalled Events: Mrs. Judkins's Cante-Fable

The Integration of Genres in a Traditional Repertoire

Putting in a Garden and Gardening

Old Mister Fox and Old Man Coyote

Sir Hugh and the International Minority Conspiracy

A Matter Of Taste: Folk Aesthetics

Intentional Connotation: Imagery

Connotative Word Play: The Double-Entendre Cherry

The Sun Myth: Structural Connotations of Morality

7. Folklore and Cultural Worldview

Worldview and Tradition among European Americans

Cultural Philosophy and Folklore

Worldview and Traditional Material Artifacts of the Navajo

Individual and Cultural Orientation

Individual and Cultural Deportment

Worldviews in Multicultural America

Ethnicity and Worldview: African Americans

Ethnicity and Worldview: Spanish Americans, Mexican Americans, Latinos

Ethnic Folklore and Cultural Terminology

From Corn God to Tractor in Northern Europe

"I'll Be down to Get You in My One-eyed Ford" (From a 1930s Navajo Song)

The Ax, the Alphabet, and the TV

The Cultural Cement Truck Driver

Cultural Psychology and Folklore

The Racial Polack and Other Shared Concerns

The Approach to Fieldwork: Tactics

Aftermath: Transcription and Notes

Folklore and Literary Criticism

Folklore and Historical Meaning

Applied Folklore as a Basis for Action

Folklore and Life in Multicultural Settings

Folklore and Cultural Relations

Front Matter

Title Page

The Dynamics of Folklore

Revised and expanded Edition

Barre Toelken

Utah State University Press

Logan, Utah

1996[[b-t-barre-toelken-the-dynamics-of-folklore-1.jpg

Dedication

For

William A. “Bert” Wilson, friend and mentor, whose mantle I inherited, along with his chair, desk, office, archives, house, chimney, bookcases, and job

Publisher Details

1996 Utah State University Press

All rights reserved

Utah State University Press

Logan, UT 84322-7800

Typography by WolfPack

Cover Design by Michelle Sellers

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 98765432

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Toelken, Barre.

The dynamics of folklore/Barre Toelken.—Rev. and expanded ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-87421-203-0

1. Folklore—Methodology. 2. Folklore—United States. 3. United States—Social life and customs. I. Title.

GR40.T63 1996

39O’.O1— dc20 95-50243

CIP

Illustrations

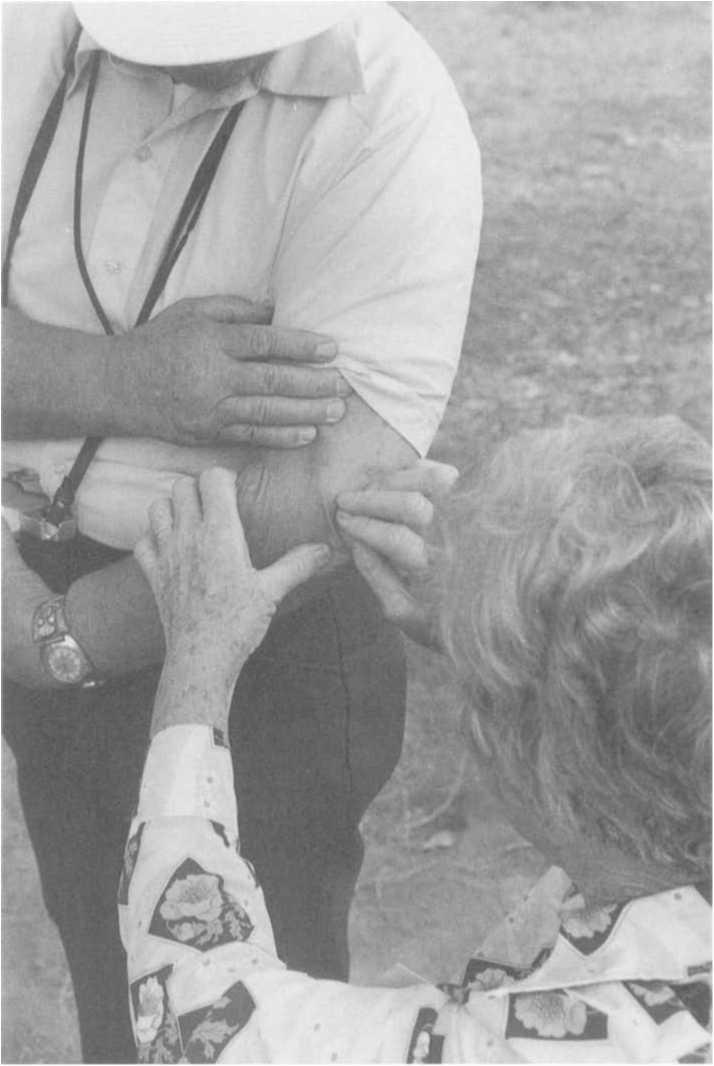

Wart charmer Onie Ruesch

Paulmina Nick New provides Italian customary foods 21

Hunting for Easter eggs 21

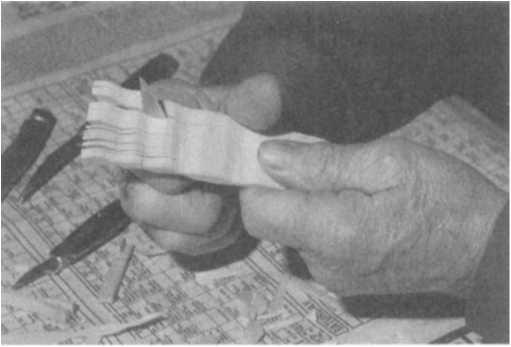

Vernon Shaffer, carver and whittler 35

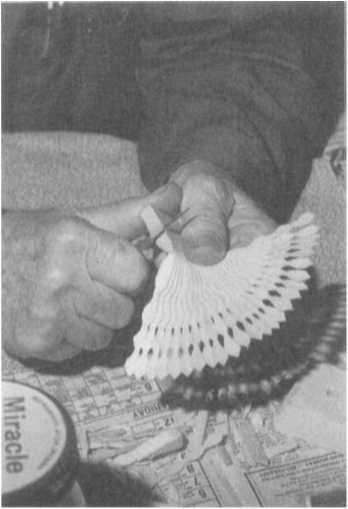

Vernon Shaffer’s handiwork in whittled fans 36

Dah diniilghaazh (“frybread”) 45

Yodeling along a mountain trail in Austria 46

A “climber” or “topper” waves from the top of a spar pole 61

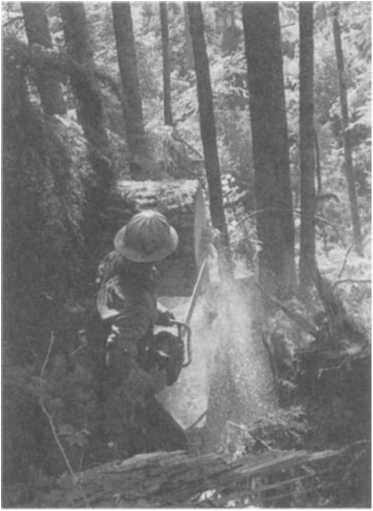

A modern logger working in the woods 63

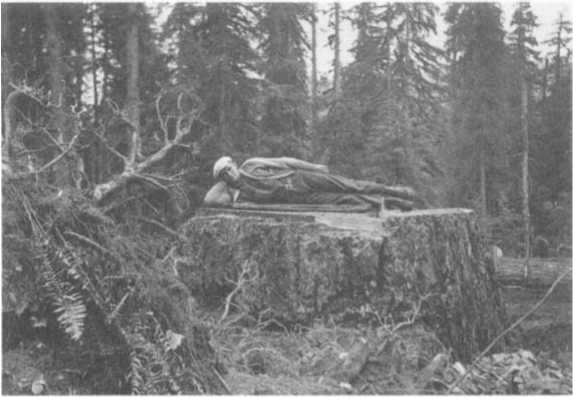

A logger in the 1930s on a freshly cut stump 63

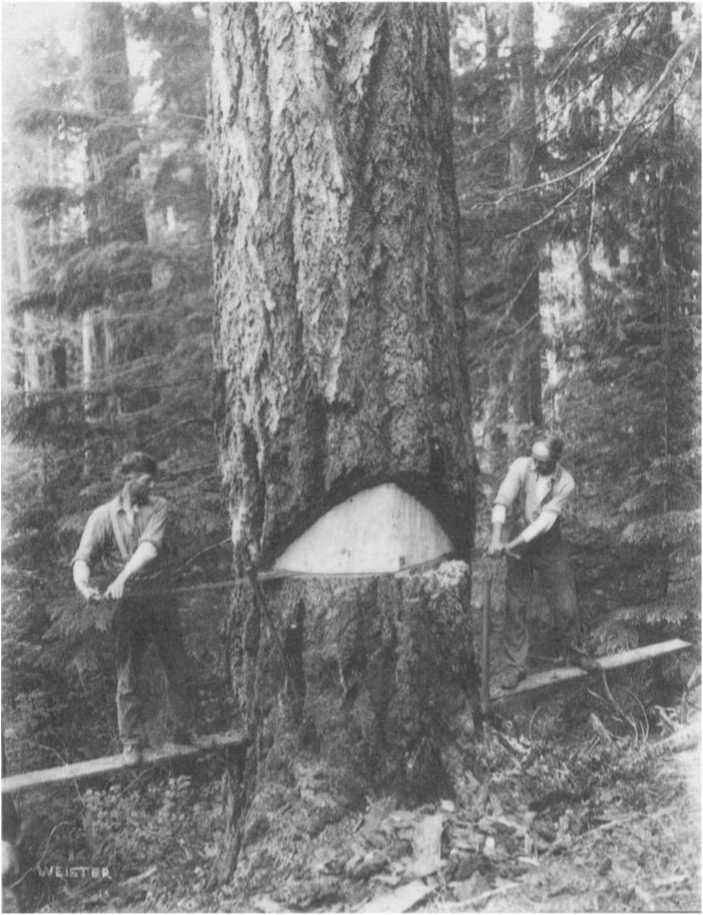

Standing on springboards, loggers fall a Douglas fir 65

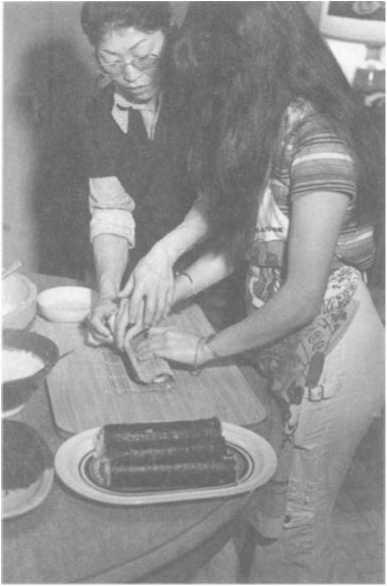

Sushi 82

Evaporating the sweet rice vinegar from the sushi rice 82

A sheet of nori is toasted lightly 83

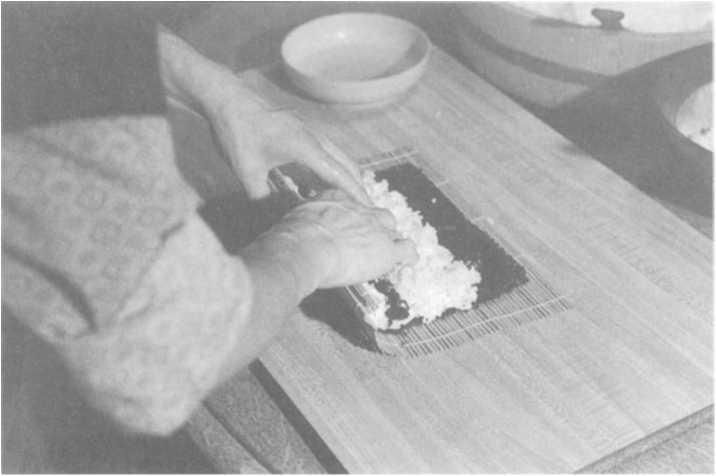

Rolling up vinegared rice on a sheet of nori 83

Controlling the density of the roll by “feel” 84

Proper technique in rolling 84

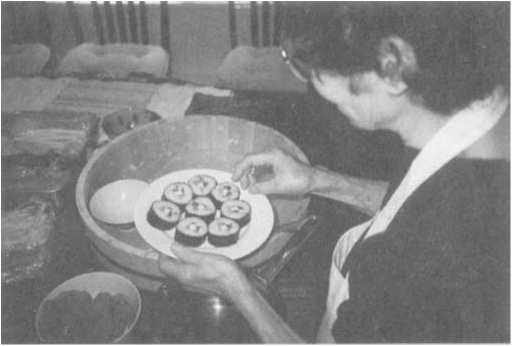

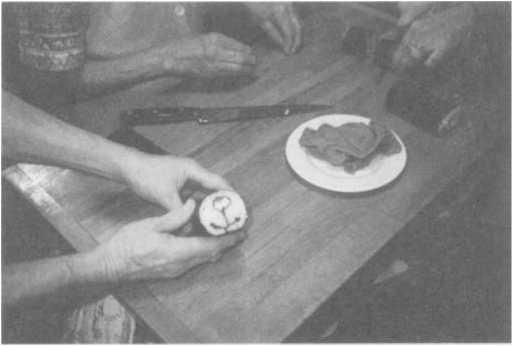

Makizushi rolls 85

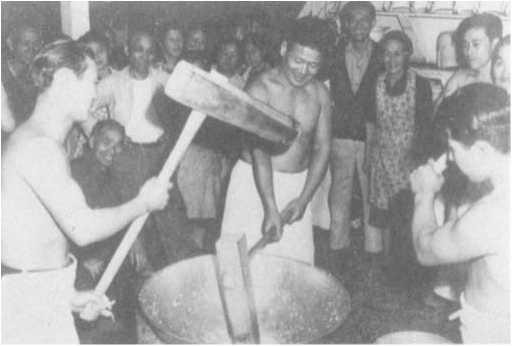

Pounding rice for mochi in an usu (mortar) with kine (mallets) 88

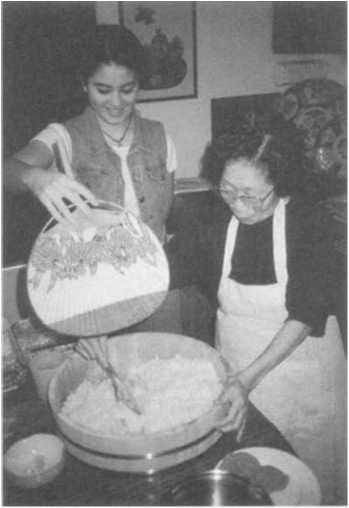

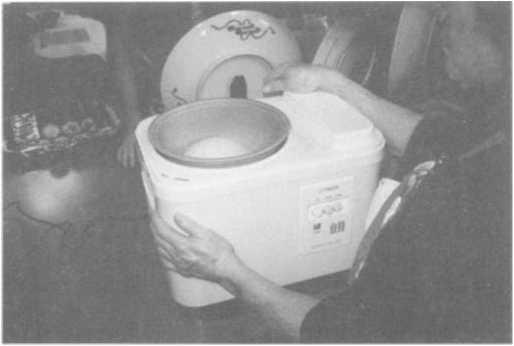

Making mochi at the Smithsonian Festival of American Folklife 88

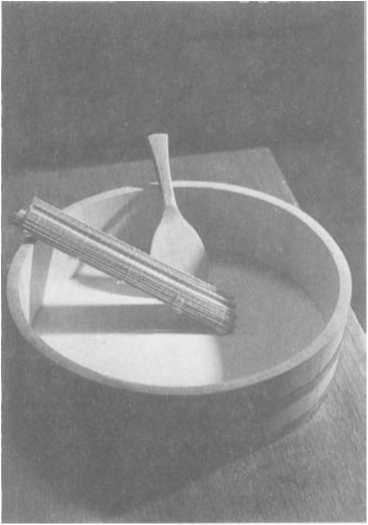

The basic “tools” for making sushi 89

Making mochi using an oscillating machine 89

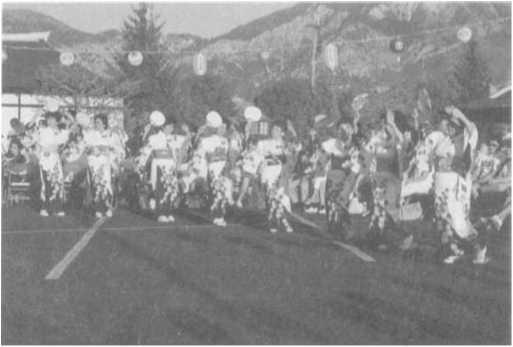

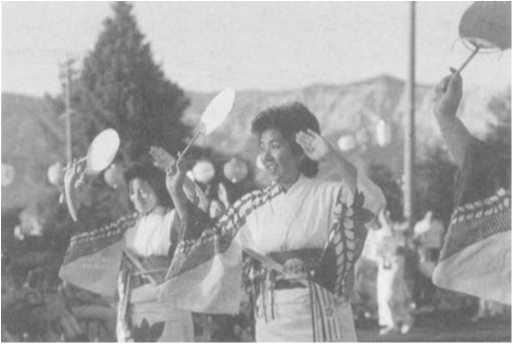

Japanese Americans celebrate the summer Obon festival 96

Young women share their culture through the Obon dance 96

Obon dancing 97

Taiko drummers 97

Horse head tombstone in Monticello, Utah 104

Mormon gravestone with temple 104

Gravestones in Astoria, Oregon, showing fishing boats 105

A “weeping lady” gravemarker in Logan, Utah 106

Irish and Serbian American gravestones 107

A graveyard in Japan 108

The grave of a young English visitor in southwestern Germany 108 A Maypole dance 116

The Navajo string figure for dilyehe, the Pleiades 119

A Navajo string figure of a worm crawling over branches 120

Chiyo Toelken and Patsy Bedonie do a series of string games 122

Cooking dah diniilghaazh for a kinaaldd 131

Yazzie Johnson makes naneeskaadi 132

The Yellowman family eating ndneeskaadi 132

John Palanuk adjusts the strings on a hammered dulcimer 142

The Haywire Band of Springdale, Utah 143

Exchanging tunes and fingering at the West Virginia State Folk Festival 143

Water dowser Eldon McArthur teaches water witching 147

William Wilson learns water witching 148

Helen Yellowman weaves a Fen rug 161

“Chris” Christensen whittles a fan for his grandson 186

A fan and a tower of balls-in-boxes whittled by “Chris” Christensen 187 Joanne, Helen, Hugh, and Mike Yellowman 189

A pair of moccasins made by Yellowman 189

Yellowman stands by his wife’s loom 191

The wily western jackalope 193

Christmas ornament made from an African Ankoli cow skull 194

Bess Hockema 198

Bess Hockema working on an afghan 202

“Chair Quilt” by African American quilter Annie Jackson 224

A “fancy dancer” at the University of Oregon Powwow 224

A young woman dances the Shawl Dance at the powwow 225

Ute flutemaker Aldean Ketchum plays his Hawk Flute 227

Flutes made by Aldean Ketchum 227

A Navajo wedding basket 240

Neatly stacked woodpiles from Austria, Germany, and Alsatia 264 Navajo necklaces made from gad bi naa’(juniper seed shells) 279

Round rosettes in Navajo jewelry that suggest stars and the cosmos 280 Navajo wedding basket design in a juniper seed necklace 281

A Ye’ii rug woven by Helen Yellowman 283

A personalized rug made by Zonnie “Grandma” Johnson 285

Grandma Johnson spinning yarn sunwise 286

Grandma Johnson and the author flirting 286

Yellowman with his self-made bow and arrows 288

“Molding and straightening” during kinaaldd, the Navajo girls’

maturation ceremony 290

Grinding white cornmeal for the kinaaldd cake 290

Women pour cornmeal batter for the kinaaldd cake into a cornhusk-lined pit 291

Vanessa Brown puts the cornhusk covering over the cornmeal batter 292 Sonya Starblanket Brown distributes pieces of her kinaaldd cake 292 Traditional methods of stacking loose hay in the arid West 302

Appaloosa markings and a warrior’s hand stamp on a Native American pickup 305

A couple enters a hogan at the beginning of a Navajo wedding 314

Kissing on “the A” to become a True Aggie

Henry Fleming hand-braiding his own rawhide riata

Winding string to make Japanese temari

Measuring the string ball for roundness

Temari are given away as decorations, toys, or Christmas ornaments

A hand-wrought iron doorhandle and a “Nebraska logging chain”

Grinding chiilchin (desert sumac berries) on a traditional grindstone

Preface

Up to the 1970s, it was common for most folklorists, and most folklore textbooks, to pay more attention to the items of folklore than to the live processes by and through which folklore is produced. This led at least one folklorist to lament that folklore scholarship tended to “dehumanize” folklore. Briefly put, this book is an attempt to humanize folklore by urging an approach to folklore study that stresses “the folk” and the dynamics of their traditional expressions. In this approach, my thinking is very much indebted to the works of those who have focused on style, performance, context, event, and process, rather than on genre, structure, or text. However, the book does not attempt to do away with generic considerations. My hope is rather that it will constitute a theoretical complement to other works on folklore by providing a balance, or, to use another figure, by suggesting other equally valid avenues by which the living performances of tradition may be perceived and studied.

No particular folklore school is espoused or represented here; indeed, the suggestions offered by this book should be palatable to a broad spectrum of theoretical positions, for in it I try to provide a fair, eclectic combination of the main trends in folklore today, with the focus admittedly on the active, live aspects of folk and their lore.

Students complain, with justification, that literature is often killed in the classroom, that social sciences in the academic setting can cause us nearly to overlook people, that the music in a book of technical analysis is nowhere near as interesting as music falling on the ear from a live source. The same kinds of objections have been made to folklore classes and folklore texts: since it is possible to separate the lore from the “folk” and spend endless hours dissecting and studying the resultant texts, it is indeed possible for folklorists to overlook, or to avoid intentionally, those very dynamic human elements that make the field an exciting one to begin with. But let us remember that the word “text” comes from Latin textum, “that which is woven,” that is, a fabric, and thus it can stand as a ready metaphor for any human construction.

I hope this book can present some views of cultural “weaving” that have not been particularly characteristic of the academic approach. For one thing, where possible I have followed the lead of the tradition-bearers themselves, using their terms, topics, and perspectives. For another, I have not filtered out the so-called obscene elements that are so characteristic of folklore. In real life, and therefore in folklore, the ingenuous and friendly hospitality of Bess Hockema stands side by side with the brash machismo of “Jigger” Jones, the logger; and next to the shy, home-oriented customs of the Japanese American family there exists the open, exciting gaming and street jive of urban African American youths. Since folklore is not limited to rural environs, minority groups, and past times, I have looked as much as possible to all situations where we may see folklore in performance the way it is normally performed.

In so doing, I have stressed groups with whom I have had considerable acquaintance (loggers, Navajos, Westerners, Japanese Americans, farm families) so I could use anecdotal examples from my own experience to illustrate the main points of the book. For parallel ideas I have referred to the published work of others, but I have not pretended to scrape up extra fieldwork for this book just for rhetorical (or political) balance. For example, I have not done much work in folklore among Mexican Americans; they are certainly one of the most dynamic folk groups in the United States today, but for that very reason I have decided not to “throw them in” for mere color. Their traditions are too important for that. But I have tried to indicate works to which the reader can refer so as not to be limited by the peculiarity of my experiences.

A picture may not be worth a thousand words in folklore, for we always want multiple pictures of any folk performance or event. Nonetheless, an attempt is made in this book to present pictures of some of the dynamic processes that are discussed. The pictures concentrate chiefly on folklore actually being performed or on folk traditions being passed directly from one person to another. In addition, a few pictures are provided only so that items discussed in the various chapters may be scrutinized by the interested reader.

In the task of compiling this book and providing analytical remarks about its contents, I am primarily indebted to the people who so graciously allowed me to use their most cherished customs, beliefs, and performances. “Informants” are identified in the notes to each chapter, but I must give particular thanks to the Yellowman family and my other adopted relatives in southern Utah, the Damon and Howland families in Massachusetts, the Tabler family in Oregon, the Kubota family of Utah and California, and the Wasson-Hockema family in southwestern Oregon for allowing me to talk about them at such great length here.

All whose words are quoted have given their permission either directly to me or to other fieldworkers who recorded the materials. Some people did not want their names mentioned but nonetheless allowed their remarks to be quoted or paraphrased. No one has received payment for materials used here, but neither have the folk expressions become mine or the publisher’s by virtue of appearing in this book. Even if it were not for copyright law (which protects the ownership of spoken texts), the various folk “performances” offered here, mere fossils on the printed page, remain among the cultural property and under the personal proprietorship of those who are still telling stories, singing songs, building barns, and playing the dozens in complete (and admirable) disregard for the fortunes of textbooks, the passions of students, and the aspirations of university professors. The appearance of their folklore in these pages does not interrupt the regular traditional process, nor does it diminish the cultural possessions of traditionbearers. On the other hand, it would certainly impoverish the student of culture if these texts and expressions and events were not available. The flesh, blood, and bones of the live folklore discussed here belong to those who have been the tradition carriers; the commentaries are mine, guided and informed by their remarks.

For assistance in fieldwork details and analysis leading to some of the passages in this book, I am indebted to Ray Scofield, who helped with logger folklore and with the songs sung by Mrs. Clarice Judkins; to George Wasson for his intermediary role with the Wassons and Hockemas; to my wife, Miiko, and to Misa Joo, Seiko Kikuta, and Chiyoe Kubota for guidance in interpreting Japanese American cooking custom and symbolism; to Twilo Scofield for helping provide a full description of the Wodtli-Tabler Thanksgiving dinner; to Edwin L. Coleman II, Beverly Robinson, and Patricia Turner for suggestions and interpretations on African American folklore; to Joseph Epes Brown for unfailing wisdom in regard to Native American culture, religion, and worldview; to William A. Wilson for insight into the proprieties of outsider interpretation of Mormon folklore, as well as valuable perspectives on the importance of folklore study generally.

Photographers other than myself are identified in the photo captions, but I must mention here my sincere thanks to the following people for allowing me to use their fine pictures. Suzi Jones let me pore over her extensive photo collection of Northwest traditions; the American Folklife Center generously supplied a number of photographs from the Center’s collecting projects; William Tablet, formerly a logger and scaler near Sweet Home, Oregon, loaned me pictures he took of loggers in the woods during the 1940s; the Fife Folklore Archives section of Utah State University’s Special Collections Division, under the direction of Barbara Walker, has an immense collection of color slides taken by folklorists Austin Fife, Alta Fife, and William A. Wilson, which were generously put at my disposal. Historical logging photos from glass plates taken in the early 1900s were supplied by the Special Collections Division of the University of Oregon Library.

Professors Louie Attebery of the College of Idaho, George Carey of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and Patrick Mullen of Ohio State University were my distant advisors during the writing of the first edition of this book. In addition to perspectives I have gained over the years by following the work of folklorists like Roger D. Abrahams, Richard Bauman, Dan Ben- Amos, Alan Dundes, Henry Glassie, Dell Hymes, Albert Lord, and John Miles Foley (i.e., those who have worked mainly on the performative aspects of folk expression), I have benefitted very much while working on this revision from advice and from ongoing discussions with my immediate colleagues at Utah State University—Steve Siporin, Barbara Walker, Randy Williams, Jay Anderson, Leonard Rosenband, and Clyde Milner II—as well as from more distant colleagues such as Neil V. Rosenberg, Patrick Mullen, Simon Bronner, Bengt af Klintberg, Michiko Iwasaka, David Buchan, Jack Santino, David Hufford, Jan H. Brunvand, Sandy Ives, Wolfgang Mieder, Lynwood Montell, Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barry Ancelet, Carol Edison, Meg Brady, Jim Griffith, Polly Stewart, Roger Welsch, Jo Radner, Bob McCarl, Chip Sullivan, Jerry Parsons, Joe Hickerson, Alan Jabbour, Knut Djupedal, and Ellen Stekert—a formidable array of folklorists, believe me. My continuing dialectic interaction with Elliott Oring has forced me to be more clear and logical in my formulations and my associations with German colleagues like Hermann Bausinger, Hannjost Lixfeld, and Rolf-Wilhelm Brednich have continually encouraged me to take a broader look at European perspectives in the study now referred to there as All- tagsforschung (research in the everyday) and empirische Kulturwissenscha.fi (empirical cultural science). The book has been deeply affected by their help and would not be in its current state without their generous advice. Of course I accept the responsibility for the way it now stands, but I cannot overstate the really considerable role these colleagues have played in shaping the final product and giving me reasons to believe it was worth doing.

Utah State University Press has been exceptionally fortunate in having John Alley as editor and Michael Spooner as director, considering the quality they have brought to the press’s offerings generally and to the development of a folklore component in particular. When I was trying to decide where to publish this revision of The Dynamics of Folklore, it was their skills and commitment that convinced me that USU was the best place to do it. Working with these talented professionals has made it even more clear that I made the right choice.

Introduction: Into Folkloristics with Gun and Camera

Anyone looking into the subject of folklore for the first time will perhaps be surprised to discover that the scholarly discussion of the subject has been taking place for over two hundred years, mostly among people who have approached it from vantage points related to other interests and disciplines: language, religion, literature, anthropology, history, and even nostalgia and something close to ancestor worship. Indeed, the famous story of the blind men describing the elephant provides a valid analogy for the field of folklore: The historian may see in folklore the common person’s version of a sequence of grand events already charted; the anthropologist sees the oral expression of social systems, cultural meaning, and sacred relationships; the literary scholar looks for genres of oral literature, the psychologist for universal imprints, the art historian for primitive art, the linguist for folk speech and worldview, and so on. The field of folklore as we know it today has been formed and defined by the very variety of its approaches, excited by the debate (and sometimes the rancor) brought about by inevitable clashes between opposed truths.

The earliest “schools” of folklore were mainly antiquarian; that is, they concerned themselves with the recording and study of customs, ideas, and expressions that were thought to be survivals of ancient cultural systems still existing vestigially in the modern world. Many early scholars were interested in primitive religions and the ancient myths that may have informed their development. Still others were interested in the roots of language and in the study of the relationships between languages in far-flung families. Still others, often country parsons, busied themselves in noting quaint rural observances that might have hearkened back to pre-Christian times. Among the many encouragements to the study of tradition, not the least was the appearance of Darwinian theories in the mid-1800s; if life could be said to have developed from simple to complex forms, then, many argued, culture itself might have evolved in the same way. Folk observances and fragments of early rituals were taken as simple elements from an earlier stratum of civilization, studied because they might reveal to us the building blocks of our own contemporary, complex society. The focus for these studies was primarily on lower classes, peasants, simple folk, “backward” cultures, and “primitives,” for it was believed that these kinds of people had avoided or resisted longest the sophisticating influences of so-called advanced culture. Conversely, urban dwellers, immersed in literacy and sophistication, were thought to be immune to folklore or beyond its limitations. From their ranks came those who studied “the folk.”

Under these circumstances, it is not surprising that the main arena for early folklore study was the rural environment. In fact, among the German folklorists, the term Volkskunde denoted the entire lifestyle of the rural people, and das Volk, “the folk,” were conceived of as a homogeneous group. The assumption seems to have been that only away from the influence of technology and modern civilization—with their possibilities for education and mobility—could one find those antique remnants of tradition that might reveal to us the early stages of our cultural existence. This basic assumption for the normal habitat of folklore still exists today in many European and South American countries where folklore is understood to be, by definition, the traditions of rural people, who are ethnically and regionally homogeneous. In fact, up until very recently the rural scene has been the basis for most American folklore studies as well, for American culture itself has been defined—in its own terms—by a vanishing frontier, a disappearing pioneer tradition, a fading of the “good old days.” Modern America has been thought by many to be totally lacking in folklore, almost in direct proportion to the time that separates Americans from their own rural frontier.

Since early American folklorists saw the rural atmosphere as one that might harbor fading remnants of folklore, they made their way to the Appalachians and other “remote” spots in search of the treasures of olden times. In tune with the feeling of the countryside in which the materials were sought, the accompanying descriptions were markedly bucolic: Folklorists spoke of reaping rich harvests of lore, gleaning last remnants of song, plowing narrow fields of folklore, tracking elusive genres in the nooks and byways of the back country, one heard about small eddies of ethnic groups, song catching the mountains, and, inevitably, the nurturing of a field considered ripe for the picking.

Even though these words are still used, modern folklorists do not limit their attention to the rural, quaint, or “backward” elements of their culture. Rather, they will study and discuss any expressive phenomena—urban or rural—that seem to act like other previously recognized folk traditions. This has led to the development of a field of inquiry with few formal boundaries, one with lots of feel but little definition, one both engaging and frustrating.

The person who wishes to look into this expanding discipline will want to have more detailed guides and maps for the terrain. It will come as neither a surprise nor a satisfaction to find that more than one folklorist has defined the field as being made up of those things that folklorists care to talk about. One will need to know that this field has particular battlegrounds, heroes, and monuments. There was the Ballad War, in which a whole generation of scholars fought over the question of communal origins versus individual composition for the traditional ballad (modern scholars are inclined to view that battle as unfortunate and even needless, yet out of it came a mature field of ballad scholarship that one must master in order to proceed into fruitful areas of new folksong research and speculation). There was the Solar Mythology School of Max Muller and others, which related nearly all mythic phenomena to sun, moon, and stars (the Reverend R. F. Littledale, using Muller’s own theories, subsequently proved that Muller himself was a sun god). There was the myth-ritual theory urged by Lord Raglan, among others, which insisted that the heroes of myth and folklore could only have derived from ritual characters and not from historical people. (This view had been under attack for years when Francis Lee Utley finally proved, using Raglan’s list of attributes for the hero, that Abraham Lincoln got a perfect score and therefore was a ritual character who had never really lived.) And there have been skirmishes over the widespread view that folklore is simply (1) pagan detritus, stuff left over from previous, barbaric times, passed along by ignorant and illiterate peasants who didn’t know any better, or (2) degenerated material from once courtly sources. J. G. Frazer felt that folk remnants could tell us what culture was like in earlier days, that the study of today’s primitives could show us what we had been like at that stage of development. Others busied themselves to collect bits of folklore before it should degenerate altogether and cease to exist. These views obviously reflect the European-American premise of linear movement of time and history, and they represent thus a cultural attitude toward tradition rather than a critical observation of how tradition really operates.

Perhaps the most subtle battle in modern folklore is the constant attempt of scholars to reform the widespread journalistic use of the words folklore and myth. In the newspapers, and in the common understanding of many people, the terms have come to mean “misinformation” or “misconception” or “outmoded (and, by implication, naively accepted where believed) ideas.” The misunderstanding and misapplication of these terms seem to stem from a modern continuation of that notion referred to previously, that only backward or illiterate people have folklore; where it exists among us, by implication, it represents backward or naive thinking. As subsequent chapters will show, this use of folklore to imply intellectual deficit is simply not borne out by the facts: something we call folklore is found in great plenty on all levels of society, and scholars are at some pains to account for its persistence and development.

These wars, the struggles over definition, and the dizzying variety of critical approaches may initially put off the person newly interested in folklore. They need not cause fear, however, if put in a proper perspective. The great wars are over, anyhow, largely because there is now a profession of folklorists who talk to each other (sharply, at times, to be sure) and share perspectives and approaches.

There are universities in which folklore is taught as an advanced undergraduate and graduate discipline, and many of America’s leading folklorists are former classmates.

We have not become immune to the well-educated, well-intentioned myopia suffered by Muller and Raglan, however, so it is all to the good that each era of folklore study has continued to have its mavericks, young upstarts who do not accept present boundaries of the field. While one generation of established scholars studies texts and artifacts, a new group arises to call attention to the folk themselves; then others come forward to insist that a focus on context or communication or performance or structure would do better justice to the subject. The Young Turks of one era in turn become the middle-aged professors who teach folklore courses in the university, only to deal with the mavericks in their own classes.

Some leading folklorists have described the current state of the discipline in terms of schools, acknowledging that, in spite of widespread agreement about the field in general, there are distinct and well-structured methods of scrutinizing materials. The full account of these schools given by Richard Dorson in Folklore and Folklife: An Introduction is obligatory reading for anyone starting out in folklore. A characterization of these schools by their focus may help show their real differences in critical stance.

The most prominent single approach is that which asks us to look at the artifacts of folklore: “the text,” the final product of the folk performance, whether it be made of words (a ballad, a tale, a proverb) or of physical materials (a quilt, a barn, a chimney) or of music (a fiddle tune) or of physical movements (a dance, a gesture) or of culture-based thought and behavior (popular belief, custom). As long as we note the broadened use of the term, we may call this the text orientation to folklore. Usually, texts are grouped into genres and scrutinized for their content, their structure, and their kinship with other texts. Comparative approaches such as the historical-geographical method (sometimes referred to as the Finnish School, it is as much a critical stance as a methodology) are based on the concept that a study of text or artifact variation can reveal the real contours and principal features of the folk item. The focus is thus on the folk expression as an object of interest, and the processes of its development are inferred from a study of the range of features changed or retained in those variant items considered to be versions of the same item. No doubt one reason for the strength and wide development of this view is that many early folklorists were trained in literature, where the text is usually central. But folklorists today use the word “text” broadly, in its etymological fullness: a woven object, hence a culturally “constructed” expression.

A different stance, one long familiar to anthropologists and now championed by many folklorists, may be called the ethnological orientation. Its main focus is the group of people that produces the lore and provides the live cultural matrix within which a text is articulated and understood. Here, the text or artifact is important, of course, but the principal features scrutinized by the scholar are the dynamics of the group: what it is, how it functions, how it perpetuates itself, what its coordinates for reality and logic are, what its systems (subgroups, clans, status levels, moieties, kinship patterns) may be, and how all these functional societal realities are expressed in vernacular formats. While the basic question for the textual approach might be, “What is the item like, and how does it function?” the main question for the ethnographic approach might be phrased, “How does a particular culture express itself and its shared values in shared traditional ways?”

Another more recent orientation seizes on performance as the primary grouping of phenomena to be studied. Here the individual performer or creator of traditional artifacts is viewed operating in and for an audience made up of the group of people whose tastes and responses condition—and occasion—the performance. The primary question here is, “Who is expressing what for whom— and when, how, and why?”

Still another scholarly preference is a leaning toward the explanation of how and why certain kinds of folklore continue to operate in any given instance. This orientation may be termed the functional approach. Why do certain elements of folklore come into being? Why do we continue to pass them on? Observing that traditions can hardly exist when they make no sense or fulfill no purpose at all, the functionalists seek to account for folklore’s generation and survival by studying particular instances and applications of traditional expression and behavior.

Probably the most prominent approach to folklore in recent years has been contextual, addressing details of the immediate surroundings in which folklore takes place and out of which folklore may grow. One of the most basic areas of scrutiny here has been the psychological: the immediate personal, biological, and psychosocial drives and constraints felt by an individual as a tradition is practiced. Drawing especially upon the work of Freud and Jung, folklorists have sought to relate basic mental processes to the kinds of idea sets that foster traditional behavior and expression from culture to culture. Beyond the psychological bearings of the individual, many folklorists explore the immediate physical context in which an artifact or a folk expression is produced: the group of people who may be present, the weather, the occupational situation, or any other setting that may induce or modify traditional behaviors or performances. On still another level, contextualists are interested in geographical factors—how region may exert an influence on the maintenance or development of traditional expressions. Broader yet is the interest in historical context, the ways in which certain periods of humanity’s experience may occasion the development or the dismemberment of folk tradition. (Historical and geographical concerns expressed as contextual interests should not be confused with the historical- geographical method mentioned in connection with the first area of focus, in which the artifact itself is the main subject.) Social, political, and economic contexts have become obligatory considerations in current work on the folklore of gender, ethnicity, and occupation, thus extending the reading range of modern folklorists.

Contextual perspectives are demanded of all folklorists today; most of the major practicing scholars can be found centering their interests on any one or several of the areas of focus previously mentioned, but they all take contextual evidence into consideration as a standard obligation. Perhaps it is this recognition of the unavoidable effects of context that sets modern folklore scholarship apart from that of the late 1800s and early 1900s. Certainly, the very best works of folklore criticism are combinations of all these interests; Alan Dundes’s and Alessandro Falassi’s La Terra in Piazza is a prime example of a multi-disciplinary approach to a particular folk tradition, the running of the Palio horserace in Siena, Italy. Joan N. Radner’s Feminist Messages: Coding in Women’s Folk Culture brings the specialties of several scholars together into a rich treatment of gendered meaning in context.

Of other possible areas of focus that have not become very well defined yet, one of the most important is folk aesthetics, a concern with the aesthetic ideas of folk performers and their communities. To what extent does the exercise of a culture-centered aesthetic (taste) play a role in the performance of any traditional song or story, the production of a folk play, the construction of a quilt or a barn? Scholars are likely to pay attention to the observable community standards for what a barn or a quilt should look like, but they have been relatively hesitant to take seriously the aesthetic reflections of the performers themselves, especially with regard to the way traditional artists may extend, challenge, or contradict the customary conventions. There are exciting exceptions to this, and they will be discussed further in Chapter 5. A tour de force treatment of folk aesthetic is Henry Classic’s Turkish Traditional Art Today.

It is common for newcomers to the subject of folklore to see these varying orientations as pedantic disputes among desperate sects of purists. Why make these distinctions? Do they really matter? Is this not merely academic posing? But in fact these are empty objections. In any field one needs to determine what one is studying, and to outline at least in general those approaches to the subject that have been considered fruitful by those who have spent a considerable amount of time trying to understand the materials. One does not study medieval literature without first determining whether the literature in question is in fact medieval; one does not try to discuss poetry without first determining that the items under consideration are poems; one does not presume to discuss classical music without first determining the composer and date; and one may as well not begin talking about folklore unless there is a willingness to help establish what the ingredients of the field are, what the processes seem to be, and what the nature of the discussion should be. It is not purism but utility that leads to the discussion of what folklore is and what the focal areas are through which it may be examined. Liking the subject is only a prelude to talking about it. The old “heart-throb” school of literary criticism is gone (forever, one hopes), and we may similarly wish that the essentially elitist heartthrob school of folklore is gone forever; one does not study folklore simply by adoring the proletariat, or by clutching a guitar and sighing, but by coming to grips with serious and complex matters related to everyday expression and cultural dynamics.

It should be apparent by now that folklore is not a static field of inquiry. Not only are its approaches and methods subject to change as we sharpen our perceptions (as is true in any active inquiry), but the very content of the subject expands as our study shows us new kinships and forms. Other areas, such as medieval literature, have continually developed new approaches, but the materials studied have remained pretty much the same over the years. In folklore, by contrast, where a hundred years ago we were studying mainly tales, songs, and beliefs, we now include barns, quilts, chain letters, proxemics, games, and many other genres. The multiplicity of traditional expressions and the diversity of critical approaches to them make for an extremely exciting field of study; they also inhibit the writing of books on folklore, for one expert’s favorite line of reasoning may be of only minimal use in the classroom of another. Yet it does seem to me that all these approaches are, or could be, complementary and that no single one needs to be championed as the only way for which a textbook must provide exclusive maps and charts.

This book is founded on the simple assumption that there must be some element all folklore has in common (or else we could not lump it all together). No doubt an astute student could name several possible unifying characteristics, but I have chosen a particular one: all folklore participates in a distinctive, dynamic process. Constant change, variation within a tradition, whether intentional or inadvertent, is viewed here simply as a central fact of existence for folklore, and rather than presenting it in opposed terms of conscious artistic manipulation vs. forgetfulness, I accept it as a defining feature that grows out of context, performance, attitude, cultural tastes, and the like.

The various leading theories of folklore will be mentioned or implied in the discussion and will be noted in the bibliographical sections at the end of each chapter. The student should turn to these works for sound theoretical accounts of various particular problems in folklore; the present book, on the other hand, will provide examples of the dynamism in folklore, leaving readers free to follow particular theoretical interests on their own. To put it another way, the variety of folklore expressions and the interdisciplinary nature of the folklore field call for a book to discuss and illustrate folklore without defining it so narrowly as to inhibit particular theoretical interests or practical applications.

Accordingly, this book will be highly anecdotal and suggestive, for it aims to provide perspectives and to introduce the dynamics in a broad field. Examples come from my own fieldwork, from collections done by my students, from friends, from fellow folklorists. Some of my examples, such as the urban legend of the girl with a bouffant hairdo who is found to have a nest of black widow spiders in her coiffure, are as dated as the bouffant hairdo itself; others, like the “death car” for sale cheap in a local used car lot, may drift through our experience every couple of years. Both are examples of the continuing viability of folklore and its changeability. Readers will be able to augment my examples with their own repertoires of folklore. In any case, the book does not rest on antiquarian interests but on viability. If you haven’t heard these urban legends, which ones have you heard?

I have wanted to avoid embarrassment for anyone whose folklore, originally delivered in its usual “home” context, is quoted here as vivid example. Some names are thus withheld or changed by request to ensure privacy and to avoid making individuals into objects of scrutiny; this is especially a concern with Native American materials, particularly in those tribes where an individual may be perfectly willing to give his or her own opinion but cannot speak for the entire tribe. In addition, many of our Native American friends have been shocked at the way in which we so glibly throw their names around in our classes: said a young Navajo woman at a recent meeting of scholars interested in working with American Indian narratives, “You people get paid to study us and to put our names in your books.” Thus, while I have made certain that the materials from Native American backgrounds I have referred to here are acceptable for public scrutiny, I have not always named the specific source.

The reader hitherto unfamiliar with folklore must realize that many of the materials circulating in oral tradition among members of close groups might easily fall into the category of crude or obscene when they are quoted in print. Some scholars even estimate that some 80 percent of orally transmitted material would be thought crude by someone if it were encountered out of context. Because the central interest of folklorists today is to deal with folklore as it actually is, I have made no attempt to expurgate the texts referred to here; instead, I have omitted some materials rather than change their essential nature by “cleaning them up.” This is not to champion “obscene” materials per se, but to point out that all folklore is phrased in terms appropriate to—and usually demanded by—the group in which it is performed. Often these particular manners of expression are registered as inappropriate when they are heard by outsiders, when they are presented out of their normal context, when their audience is expanded beyond the usual local group for which and in which the performance makes sense. For these reasons, the reader is urged to go beyond the antiseptic environment of the page, beyond the restrictions of local views on propriety, and take a close look at the real folklore of real people for what it truly is. I hope this book will provide some helpful considerations for that quest.

Before the quest can get under way, of course, we need to have some basic terminology for describing (and recognizing) the features of the folklore we seek to understand. The genres (that is, the forms and kinds) of folklore fall into a number of partially overlapping categories. For convenience, the American Folklife Center in the Library of Congress uses the characterization which appeared in Public Law 94-201 (January 2, 1976) in Congress’s own definition of folklore as expressive culture: . .a wide range of creative symbolic forms such as custom, belief, technical skill, language, literature, art, architecture, music, play, dance, drama, ritual, pageantry, handicraft.” These kinds of expression are of course those which may be found on all levels of any culture; what makes them folklore is that they “are mainly learned orally, by imitation, or in performance, and are generally maintained without benefit of formal instruction or institutional direction.” What are some of the particular “forms” under these rather broad headings? Most folklorists divide them up (again, for focus and convenience in discussion) into verbal folklore (that is, expressions people make with words, usually in oral interchange), material folklore (expressions which use physical materials for their media), and customary folklore (expressions which exist through people’s actions).

Verbal folklore includes genres like epics, ballads, lyric songs (lullabies, love songs), myths (stories of sacred or universal import which people, cultures, religions, and nations believe in), legends (stories of local import which people believe actually happened but they learned about from someone else), memorates (culturally based first-person accounts and interpretations of striking incidents), folktales and jokes (fictional stories which embody cultural values), proverbs, riddles, rhymes, chants, charms, insults, retorts, taunts, teases, toasts, tongue twisters, greeting and leave-taking formulas, names and naming, autograph-book verses, limericks, and epitaphs, to name only a few of the most common.

Material folklore includes vernacular houses and barns (designed and made by those who use them rather than by trained architects), fence types, homemade tools, toys, tombstones, foods, costumes, stitchery, embroidery, tatting, braiding, whittling, woven items, quilts, decorations (Christmas trees, birthday party decor), and culturally based musical instruments and rhythm makers— insofar as they are learned by example within an ongoing tradition shared by people with something in common.

Customary folklore includes shared popular beliefs that are not transmitted by formal systems of science or religion (“superstitions”), vernacular medical practices, dances, instrumental music, gestures, pranks, games, traditional work “canons,” celebrations (festivals, birthday/wedding/anniversary/fimeral/holiday/ religious observances not required by law or theology).

Obviously, the custom of celebrating a birthday usually involves the material expressions embodied in the cake, the presents, and the decorations, and the verbal singing of “Happy Birthday.” Verbal expressions like proverbs and riddles often emerge at customary gatherings like weddings and funerals, where material items like certain foods and traditional clothing will also be part of the normal scene. Thus, while we may list these genres and categories separately (as we might also list parts of the human body separately in an anatomy class), we will normally expect to find all these forms actually functioning together interactively in customary frames of realization which involve many different kinds of expression at once, as we shall see more fully in the following chapter.

Bibliographical Notes

The bibliographical supplements to the chapters in this book are meant to be selective, suggestive, and conversational, not exhaustive. The works cited are in many instances the sources or instigations for concepts advanced in the book; others are exemplary or typical of parallel or even contrasting ideas. Some will be repeated because of their application to different chapters. Most references to articles in periodicals are to work that has appeared since 1960, although there will be numerous exceptions to this rule where certain articles on particular subjects are too germane to omit.

I assume that the interested reader, and especially the student of folklore, will become acquainted with some of the standard works in the field, chief among them the following: Stith Thompson, ed., Motif-Index of Folk Literature (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1955-1958), for the basic compendium of recurrent units in orally transmitted folklore; Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson, eds., The Types of the Folktale, 2nd rev., Folklore Fellows Communications, no. 184 (1961), for the standard listing of recurrent narrative clusters in tale form; Maria Leach, ed., Funk & Wagnalls Standard Dictionary of Folklore, Mythology, and Legend (New York: Funk & Wagnails, 1949), for a somewhat dated but encyclopedic view of folklore and its ingredients written by numerous folklorists of the day; Jan Harold Brunvand, The Study of American Folklore: An Introduction, 3rd rev. ed. (New York: Norton, 1986), for clear and brief delineations of the generic categories in folklore; Alan Dundes, ed., The Study of Folklore (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1965), for an anthology of important essays on folklore by a wide variety of scholars; and Richard M. Dorson, ed., Folklore and Folklife: An Introduction (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1972), for a modern invited symposium of professional folklorists on principal areas of interest to the serious student.

While this book will cite primarily the leading professional folklore journals, the reader, along with other serious folklorists, should make it a matter of obligation to follow up particular interests in other reputable anthropologically oriented publications as well as to check the smaller but important regional folklore journals and professional journals in geography, psychology, literature, linguistics, dialects, natural history, and history. Each of these latter fields, of course, has its own professional interests and demands, and it is well to remember that scholars in these areas do not always use the word (or the concept) folklore in the way professional folklorists might prefer. Thus, while the student should not hesitate to look into the recent journals and the contemporary standard texts of these fields for specific considerations on approach, theory, analytical models, and vocabulary, a good previous foundation in current folklore theory will be necessary to prevent disorientation and indigestion. Wherever possible, this book will call attention to some of the more helpful nonfolkloristic resources, and it will attempt to flag the topics on which specialists in the various fields may differ in their understanding (the concept of folk art, which will come up numerous times herein, is an example).

The term "folklore” was coined by a gentleman-antiquarian, William J. Thoms, one of the many well-read Victorian hobbyists interested in what were then called popular antiquities. Suggesting to readers of The Anthenaeum in 1846 that “a good Saxon compound, Folk-lore,—the Lore of the People. . .” would be a proper way of describing “the manners, customs, observances, superstitions, ballads, proverbs, etc., of olden time. . Thoms consciously created the umbrella term for a field of study which engaged some of the foremost writers and scholars of his day. Thoms’s letter is reprinted in Alan Dundes, The Study of Folklore (Englewood Cliffs, NJ.: Prentice-Hall, 1965), 4-6.

Richard M. Dorson, in The British Folklorists: A History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968) and in Peasant Customs and Savage Myths: Selections from the British Folklorists, 2 vols. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968) provides the most complete, and certainly the most readable, account of the exciting developments among English scholars during the emergence of the field we now call folklore. Much of the theoretical orientation of modern British and American folklore scholarship has its origins in the arguments and discussions recorded in these books. For a comparison between the Anglo-American orientation in folklore and that found commonly in Latin America, see Americo Paredes, “Concepts about Folklore in Latin America and the United States,” Journal of the Folklore Instituted) (1969): 2-38; also, note that since its inception JFI (subsequently renamed JFR—Journal of Folklore Research} has provided a continuing account of folklore concepts and work in progress in a variety of countries.

Historical: Among Dorson’s many works that deal with history and folklore, a good, brief sample would be “The Debate over the Trustworthiness of Oral Traditional History,” in Volksuberlieferung: Festschrift fur Kurt Ranke zur Vollendung des 60. Lebens- jahres, ed. Fritz Harkort, Karel C. Peeters, and Robert Wildhaber (Gottingen: O. Schwartz, 1968), 19-35. A more recent book-length treatment of the intersection of history and folklore is Edward D. Ives, George Magoon and the Down East Game War: History, Folklore, and the Law (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1988). Social historians routinely use folklore in their works; for a brilliant example, see Robert Darnton, The Great Cat Massacre (New York: Random House, 1984).

Anthropological: An organic view of all connotative literature as folklore is given in an anthropological frame by Munro S. Edmonson in Lore: An Introduction to the Science of Folklore and Literature (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1971); while very provocative, it pays little heed to the oral/nonoral distinction so basic to much of modern folklore theory. Three studies which approach folklore from an anthropological perspective are William R. Bascom, “Folklore and Anthropology,” Journal of American Folklore fid) (1953): 283-90; William R. Bascom, “Four Functions of Folklore,” Journal of American Folklore 67 (1954): 333-49; and Elliott Oring, “Three Functions of Folklore,” Journal of American Folklore 89 (1976): 67-80. An incisive survey of developments in the field of folklore since 1972 (when Richard Bauman and others articulated a shift from textual interest to concerns for process and performance) is J. E. Limon and M. J. Young, “Frontiers, Settlements, and Development in Folklore Studies, 19721985,” Annual Review of Anthropology 15 (1986): 437—60.

Literary: Probably the classic work is Stith Thompson, The Folktale (1946; reprint ed., Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977); in it, the tale is discussed as a distinct literary genre that has been shaped by the processes of traditional transmission. Many regions of the country are so well characterized by their folk literature that published collections are now included in literary studies. For an exceptionally well-conceived example, see Suzi Jones and Jarold Ramsey, eds., The Stories We Tell: An Anthology of Oregon Folk Literature (Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1994 [volume 5 of a six-volume series on Oregon literature]). For a discussion of how legends may be seen as folk literary dramatizations of cultural abstractions, see Michiko Iwasaka and Barre Toelken, Ghosts and the Japanese: Cultural Experience in Japanese Death Legends (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1995).

Psychological: Both Freud and Jung were extremely interested in folklore and mythology, although their theories have been beaten “to airy thinness” by their avid students. Freud believed that dreams are the less-developed materials of folklore, jokes, proverbs, and myths (see, among many others, Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams, trans. A. M. O. Richards [New York: International Universities Press, 1958] and Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, trans. James Strachey [London: Routledge and Paul, I960]). Jung felt that the recurrent patternings in myth and folklore indicated an inherited fund of potential images shared by human beings generally, although he was more disposed than his disciples to the idea that local manifestations of these images might vary considerably. A helpful article is Carlos C. Drake, “Jungian Psychology and Its Uses in Folklore,” Journal of American Folklore 82 (1969): 122-31. Joseph Campbell, once almost exclusively a Jungian, eventually combined Jung’s theories with the resources of anthropology, archaeology, history, botany, and literature in his impressive four-volume work The Masks of God: Primitive Mythology, Oriental Mythology, Occidental Mythology, and Creative Mythology (New York: Viking Press, 1959-1968); although the examples he cites are partial to his particular viewpoint, the work, especially volume 1, is interesting reading. Among present-day folklorists, probably Alan Dundes and Elliott Oring are the most consistent in their employment of psychological perspectives (mainly Freudian). Several of Dundes’s most influential essays are republished in his Interpreting Folklore (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980); some of Oring’s work is brought together in Jokes and Their Relations (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1992). An overview of the relationships between psychology and folklore as propounded by an early disciple of Freud can be found in Ernest Jones, “Psychoanalysis and Folklore,” Jubilee Congress of the Folklore Society: Papers and Transactions (London: Folklore Society, 1930): 220-37, reprinted in Dundes’s The Study of Folklore, 88-102.

Artistic and Art-Historical: This is one of the unfortunate areas wherein trained experts in art and museology differ markedly from experts in folklore on the subject of folk art. For the former, folk art is usually seen as naive or untrained art, or as whatever is left over after one has exhausted the fine arts. Primitive art—that is, art produced by nontechnological peoples—is often given serious notice, as in Paul S. Wingert, Primitive Art, Its Traditions and Styles (New York: Oxford University Press, 1962) and in Ralph Linton, “Primitive Art,” Kenyon Review 3 (1941): 34-51, reprinted in Every Man His Way: Readings in Cultural Anthropology, ed. Alan Dundes (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1968): 352-64. But folk art that lies outside the primitive category, while taken seriously by folklorists, is often stereotyped as “quaint and folksy” by art historians. Munro Thomas, in Evolution in the Arts (Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, 1932): 361-462, gives it fair but minuscule mention, while one of the standard art history textbooks, H. W. Janson’s History of Art: A Survey of Major Visual Arts from the Dawn of History to the Present Day (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1962)—in spite of its omniscient-sounding title—overlooks folk arts altogether. One of the most informative pieces on folk art is the chapter so titled by Henry Glassie in Dorson, Folklore and Folklife, 253-80. Subsequently, Glassie produced what must be the fullest study of a single nation’s folk art, Turkish Traditional Art Today (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993); it is a model of definition, sensitive description, and cultural understanding. Steve Siporin’s American Folk Masters: The National Heritage Fellows (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1992) celebrates the wide variety of folk artists recognized by the National Endowment of the Arts as the United States’ equivalents to Japan’s Living National Treasures during the first ten years of the National Heritage Fellowship Awards program. In Exploring Folk Art: Twenty Years of Thought on Craft, Work, and Aesthetics (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1987), Michael Owen Jones brings together his wide-ranging and provocative insights on a subject which has been his lifelong specialty.

Language and Linguistics: Of those whose work has aligned language study with the processes of tradition, the most prominent have been anthropologists seeking to understand better the relationship between culture and meaning. Dell H. Hymes, “The Contribution of Folklore to Sociolinguistic Research,” Journal of American Folklore 84 (1971): 42-50, as well as Dell H. Hymes, ed., Language in Culture and Society: A Reader in Linguistics and Anthropology (New York: Harper & Row, 1964) are samples of work by a dedicated and continually developing scholar in the field. One should review, as well, the work of Benjamin Lee Whorf, for example, his Language, Thought, and Reality (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1956); Harry Hoijer, ed., Language in Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1954); John J. Gumperz and Dell H. Hymes, eds., The Ethnography of Communication, American Anthropological Association Special Publications, vol. 66 (Menasha, Wis.: American Anthropological Association, 1964); and, for a broader modern look at the whole live process of language, Peter Farb, Word Play: What Happens When People Talk (1974; reprint ed., New York: Bantam, 1975). One of the most exciting developments in recent folklore-and-language studies has involved a re-examination of women’s language in its vernacular contexts. Among the most interesting are Deborah Cameron, Feminism and Linguistic Theory (London: Macmillan, 1985); Jennifer Coates and Deborah Cameron, eds., Women in Their Speech Communities: New Perspectives on Language and Sex (London: Longman, 1988); Joan Newlon Radner, ed., Feminist Messages: Coding in Women s Folk Culture (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993).

The antiquarians are often glibly dismissed for not knowing as much as we do today (may the charity of later generations be more generous when it comes to the scrutiny of present-day truths), but they and their works make some of the most fascinating reading in all folklore. The newcomer to folklore must be warned that an entry into John Brand’s Observations on Popular Antiquities: Chiefly Illustrating the Origin of Our Vulgar Customs, Ceremonies, and Superstitions, 2 vols., arr. and rev. Henry Ellis (London: R. C. and J. Rivington, 1813) is an overwhelming and fascinating detour from which readers seldom recover. Brand and other students of antique times were erudite and serious scholars, mostly, and were often the masters of several languages. They were among the central thinkers of their day, and they overlooked little in their searches through notebooks, country customs, and church and town records to find elements of thought and action that had flourished before the coming of Christianity. Brand lamented the way in which the Puritans and their successors had tried to obliterate the older customs (obviously his use of vulgar means “of the common people" and does not include the modern inference that common means “lowly”). Other representative antiquarians, often identifiable by the titles of their works, were Sabine Baring-Gould, Curious Myths of the Middle Ages (London: Rivingtons, 1866), among numerous works on songs and fairy tales; Henry Bourne, Antiquitates Vulgares (Newcastle: J. White, 1725); Allen Cunningham, Songs: Chiefly in the Rural Language of Scotland (London: Smith and Davy, 1813) and Traditional Tales of the English and Scottish Peasantry (London: Taylor and Hessey, 1822); Francis Grose, The Antiquities of England and Wales, 6 vols. (London: S. Hooper, 1773-1787); Alfred Nutt, Celtic and Mediaeval Romance (London: D. Nutt, 1899); Thomas Percy, Reliques of Ancient English Poetry, 3 vols. (London: J. Dodsley, 1765); Walter Scott, The Border Antiquities of England and Scotland, 2 vols. (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Browne, 1814-1817); Thomas F. Thiselton-Dyer, British Popular Customs (London: G. Bells and Sons, 1871); William J. Thoms, Anecdotes and Traditions (London: Printed for the Camden Society by J. B. Nichols and Son, 1839); Edward B. Tylor, Primitive Culture, 2 vols. (London: J. Murray, 1871). Dorson gives a very full and fair account of them in The British Folklorists, mentioned earlier; more recently, Francis A. De Caro has related the antiquaries to our whole conception of how the field of folkloristics has developed in “Concepts of the Past in Folkloristics,” Western Folklore 35 (1976): 3-22.

No doubt the best-known German scholars of the early period were Wilhelm Mannhardt, whose Germanische Mythen (Berlin: F. Schneider, 1858) became the resource for many subsequent conjectural studies on the origins of medieval European symbols, and Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm, whose collection of Kinder-und Hausmiirchen, 2 vols. (Berlin: Realschulbuchhandlung, 1812-1815), undertaken in part due to their interest in the processes of language features, has been basic to all subsequent studies of European tales (and has made the name Grimm a household word throughout much of the world). Subsequently Johannes Bolte and George Polivka, in their monumental Anmerkungen zu den Kinder-und Hausmarchen der Bruder Grimm, 5 vols. (Leipzig: Dieterich’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1913-1932), provided linguistic and cultural notes and explanations for the Grimms’ collection, which made the materials even richer and more useful for folkloristic examination.

Alexander Haggerty Krappe, The Science of Folklore (1930; reprint ed., New York: Norton, 1964) shows the influence of the European scholarly-antiquarian stance at the turn of the century. Krappe, an American, was sure that folklore was essentially rural and antique, and it followed that progressive America would not provide much for the scholar. Statements such as, “In every modern country the rural populations are still addicted to beliefs and practices long since given up by the bulk of the city people” (p. xvii) and “In the city proper, as is well known, the typical proletarian is the most traditionless creature imaginable” (p. xviii) give a typical picture of the state of mind of the well-educated scholar interested in folklore before the professional folklore explosion of the 1950s and 1960s. Even lately, some folklorists have felt the need to explain the importance of folklore in terms of what it could teach us about “high culture;” see, for example, Francis Lee Utley, “Oral Genres as Bridge to Written Literature,” in Genre 2 (1969): 91-103, reprinted in Folklore Genres, ed. Dan Ben-Amos (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1976); the paper is of solid pedagogical value, for often students can see their own relationships to literature through comparison with traditions they already take part in. On the other hand, most folklorists today feel that folklore need not be rationalized as a field whose primary function is to acquaint us more fully with elite culture.

The ballad wars cannot be quickly summed up, for they range from petty differences to substantial and creative scholarly arguments. The best single account is still D. K. Wilgus, Anglo-American Folksong Scholarship since 1898 (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1959), esp. chs. 1, 2. One should also consult Sigurd Bernhard Hustvedt, Ballad Books and Ballad Men (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1930)—an unfortunate title, since one of the principal belligerents of the fray was Louise Pound, with her Poetic Origins and the Ballad (New York: Macmillan, 1921); Francis B. Gummere, another combatant, wrote The Beginnings of Poetry (New York: Macmillan, 1901), The Popular Ballad (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1907), and Democracy and Poetry (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1911); George Lyman Kittredge, a student of Francis James Child (the first principal American ballad anthologist and scholar) wrote an essay, “The Popular Ballad,” in Atlantic Monthly 101 (1908): 276 ff., and collaborated with Helen Child Sargent in the introduction to a one-volume abridgment of Child’s great work, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1882-1898). Although the flaming commitment to ballad studies characteristic of the old war seems to have waned, there are continuing attempts to assess and study this particular form of folk expression. Of several obligatory works, students should certainly consult Tristram P. Coffin, The British Traditional Ballad in North America, rev. ed. Roger deV. Renwick (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1977); David Buchan, The Ballad and the Folk (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1972); Albert Friedman, The Viking Book of Folk Ballads of the English Speaking World (New York: Viking, 1956); Patricia Conroy, ed., Ballads and Ballad Research (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1978); Joseph Harris, ed., The Ballad and Oral Literature (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991); M. J. C. Hodgart, The Ballads (New York: Hutchinson’s University Library, 1950); D. K. Wilgus and Barre Toelken, The Ballad and the Scholars: Approaches to Ballad Study (Los Angeles: William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, 1986).

Some of Max Muller’s theories are put forward in Chips from a German Workshop, 4 vols. (London: Longmans, Green, 1867-1875); Natural Religion: The Gifford Lectures Delivered before the University of Glasgow in 1888 (London: Longmans, Green, 1889); Anthropological Religion (London: Longmans, Green, 1892); and Contributions to the Science of Mythology, 2 vols. (London: Longmans, Green, 1887)—among many others. Reverend Littledale’s refutation appeared in “The Oxford Solar Myth: A Contribution to Comparative Mythology,” in Echoes from Kottabos, ed. R. Y. Tyrell and Sir Edward Sullivan (London: E. Grant Richards, 1906), 279-90. Richard Dorson gives a full account of the controversy in “The Eclipse of Solar Mythology,” Journal of American Folklore 68 (1955): 393-416, reprinted in Dundes, The Study of Folklore, 57-83.

Raglan’s statement on the hero is found in its fullest form in The Hero: A Study in Tradition, Myth, and Drama (London: Methuen, 1936). Utley’s witty and embarrassingly thorough rejoinder is Lincoln Wasn’t There, or, Lord Raglan’s Hero, College English Association Chapbook (Washington, D.C.: College English Association, 1965). James G. Frazer, The Golden Bough, 3rd ed., 12 vols. (London: Macmillan, 1907-1915) is both a delight and a frustration; while the examples in it and the theories suggested are illuminating and thought-provoking, the instances of folk custom outside Europe are often derived from the accounts of missionaries and other well-meaning but myopic tourists who had no professional training in how to observe people of other cultures with impartiality or clarity of vision. See Theodor H. Gaster’s enviable abridgment of the work that gives modern evaluations of Frazer’s theory and method: The New Golden Bough (New York: Criterion Books, 1959). George Laurence Gomme, in Ethnology in Folklore (London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner, 1892), argued against the simple notion that folklore was made up of survivals from particular levels of human existence that could tell us, like tree rings do today, what things were like when our culture was at a particular stage. Gomme argued that much folklore in England was pre-Aryan and had been retained and maintained precisely because of the pressure from newly arrived, intrusive, but stable “higher” civilizations. In this, he anticipated the modern notion that folklore is partly a function of internal group dynamics, of “esoteric” response, not to be easily explained only as leftovers from the past. The idea that folklore is always breaking down is discussed by Alan Dundes in “The Devolutionary Premise in Folklore Theory,” Journal of the Folklore Institute 6 (1969): 5-19; that it has had such a central role in folkloristics is challenged by Elliott Oring in “The Devolutionary Premise: A Definitional Delusion?” Western Folklore 34 (1975): 36-44, and by William A. Wilson in “The Evolutionary Premise in Folklore and the ’Finnish Method,’” Western Folklore 35 (1976): 241-49.

The standard single work on the “Finnish Method” is Kaarle Krohn, Die folkloris- tische Arbeitsmethode (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1926), trans. Roger Welsch as Folklore Methodology (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1971). Typical examples of full attempts to study the variations in a particular folklore item are Paul G. Brewster, “Some Notes on the Guessing Game, How Many Horns Has the Buck?” Bea- loideas: Journal of the Folklore of Ireland Society 12 (1942): 40-78, reprinted in Dundes, The Study of Folklore, 338-68; Bertrand H. Bronson, The Traditional Tunes of the Child Ballads, 4 vols. (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1959-1972); Henry Glassie, “The Types of the Southern Mountain Cabin,” in Brunvand, The Study of American Folklore, 529-62; Holger 0. Nygard, The Ballad of “Heer Halewijn, ’’Its Forms and Variations in Western Europe: A Study of the History and Nature of a Ballad Tradition, Folklore Fellows Communications, no. 169 (Helsinki, 1958); Stith Thompson, “The Star Husband Tale,” Studia Septentrionalia 4 (1953): 93-163, reprinted in Dundes, The Study of Folklore, 414-74. In his presidential address to the American Folklore Society, D. K. Wilgus made a special plea for the centrality of textual concern; see ‘“The Text Is the Thing,”’ Journal of American Folklore 86 (1973): 241-52.

The ethnological approach is used by far too many scholars to allow for a fair representation here. The following put forth the premise that traditional items in a culture cannot be studied except with direct reference to the cultural context from which they spring: Ruth Benedict, Patterns of Culture (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1934) and Bronislaw Malinowski, Argonauts of the Western Pacific (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1922) are classic. More recent studies by Clifford Geertz, such as “Ethos, World View and the Analysis of Sacred Symbols,” The Antioch Review 17 (1957): 421-37, his The Religion of Java (Glencoe, Ill.: Free Press, 1960) and The Interpretation ofCultures (New York: Basic Books, 1973) show the continuing application of this culturally holistic approach. For a collection of essays by various specialists of this orientation, see Alan Dundes, ed., Every Man His Way: Readings in Cultural Anthropology (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1968).

Many folklorists focus on performance and performance styles. For some solid perspectives see Roger D. Abrahams, Deep Down in the Jungle: Negro Narrative Folklore from the Streets of Philadelphia, rev. ed. (Chicago: Aldine, 1970), and its companion, Positively Black (Englewood Cliffs, NJ.: Prentice-Hall, 1970), in which African American toasts and dozens are discussed as performances (rather than as “texts”) and in which the whole dynamic of urban Black life, including economics and politics, is seen in terms of performance modes. For a more general theory on the subject, consult Richard Bauman, Verbal Art As Performance (Prospect Heights, Ill.: Waveland Press, 1984), which contains not only Bauman’s earlier essay from the Journal of American Folklore, but several supplementary pieces by other specialists in the study of performance. The relationships between live performance and eventual appearance of a “text” in printed form are discussed by Elizabeth C. Fine in The Folklore Text: From Performance to Print (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984). Critical issues in the discussion of performance meanings are taken up by Dennis Tedlock in The Spoken Word and the Work of Interpretation (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1983); Tedlock illustrates many of these issues in his presentation of Native American narrative performances in Finding the Center: Narrative Poetry of the Zuni Indians (New York: Dial Press, 1972; repr. University of Nebraska Press, 1978). The interactive, reflexive dynamics of verbal performance are brilliantly discussed by John Miles Foley in Immanent Art: From Structure to Meaning in Traditional Oral Epic (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991). Michael Owen Jones makes it clear in The Hand Made Object and Its Maker (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1975) that the idea of performance is not to be limited to songs and stories, but must be extended to cover all kinds of expressive activities—including the production of material items—performed for others.

As it will become clear from the rest of this book, context is one of the most important single considerations in folklore study today. Two clear statements on this are obligatory reading: Alan Dundes, “Texture, Text, and Context,” Southern Folklore Quarterly'll (1964): 251-65 and Dan Ben-Amos, “Toward a Definition of Folklore in Context,” Journal of American Folklore 84 (1971): 5-15, reprinted in Toward New Perspectives in Folklore, ed. Americo Paredes and Richard Bauman (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1972), 3-15. Kay Cothran discusses the effect of immediate personal context (male narrator, female interviewer, wife of narrator sitting nearby) on anecdotal performance in “Talking Trash in the Okefenokee Swamp Rim, Georgia,” Journal of American Folklore 87 (1974): 340-56. Foran excellent discussion of the effects of region on people and their folklore, see Suzi Jones, “Regionalization: A Rhetorical Strategy,” Journal of the Folklore Institute 13 (1976): 105-20. The dynamic relations among nature, geography, setting, and culture are brilliantly discussed by Yi Fu Tuan in Topo- philia (Englewood Cliffs, NJ.: Prentice-Hall, 1974; repr. with new preface, New York: Columbia University Press, 1990). The historical context of folklore is of course the foundation of Richard Dorson’s standard, American Folklore (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1959). The early chapters of Lewis Mumford, The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and World, 1961) delineate a combination of geographical, historical, mythic, and folkloric forces that interplayed as a context for the earliest villages and towns; see esp. pp. 5-35.

Aesthetics in folklore will be taken up more fully in Chapter 5. For a central statement on the subject, see Michael Owen Jones, “The Concept of‘Aesthetic’ in the Traditional Arts,” Western Folklore 30 (1971): 77-104.

Although “obscenity” is only one aspect of response to folklore out of its usual habitat, it is a matter the student should try to settle accounts with early. The Journal of

American Folklore dedicated an entire issue to the subject (vol. 75, no. 297 [July- September 1962]). One might also consult G. Legman, No Laughing Matter: Rationale of the Dirty Joke, 2nd series (New York: Breaking Point, 1975); and Vance Randolph, Pissing in the Snow and Other Ozark Folktales, ed. Rayna Green and Frank Hoffman (Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 1976).