About the authors: “Benrik are Ben Carey and Henrik Delehag, authors, artists and all-round creative pundits. Benrik’s goal is to create an alternative to the current rationalistic collective imagination, turning everyday life on its head before bashing it in. Once this alternative worldview has been seeded in enough readers’ minds, it will be child’s play to take over the state, the army, the media and most of the major multilateral institutions. Watch this space.”

Benrik

This Book Will Change Your Life (Preview)

Day 3: Throw something away that you like

Day 5: Cut out and stick this sign on any item of public infrastructure

Day 6: Write the opening sentence of your debut novel

Day 7: Masturbate at 12:55 to the following fantasy!

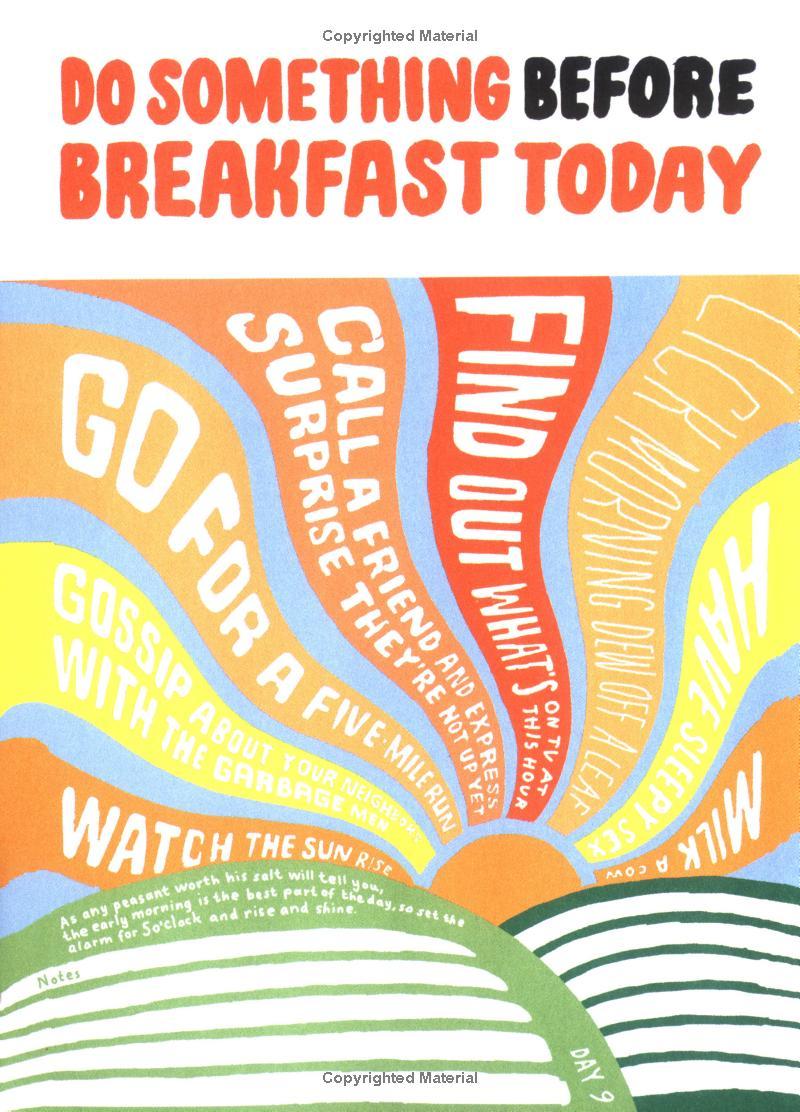

Day 8: Do something before breakfast today

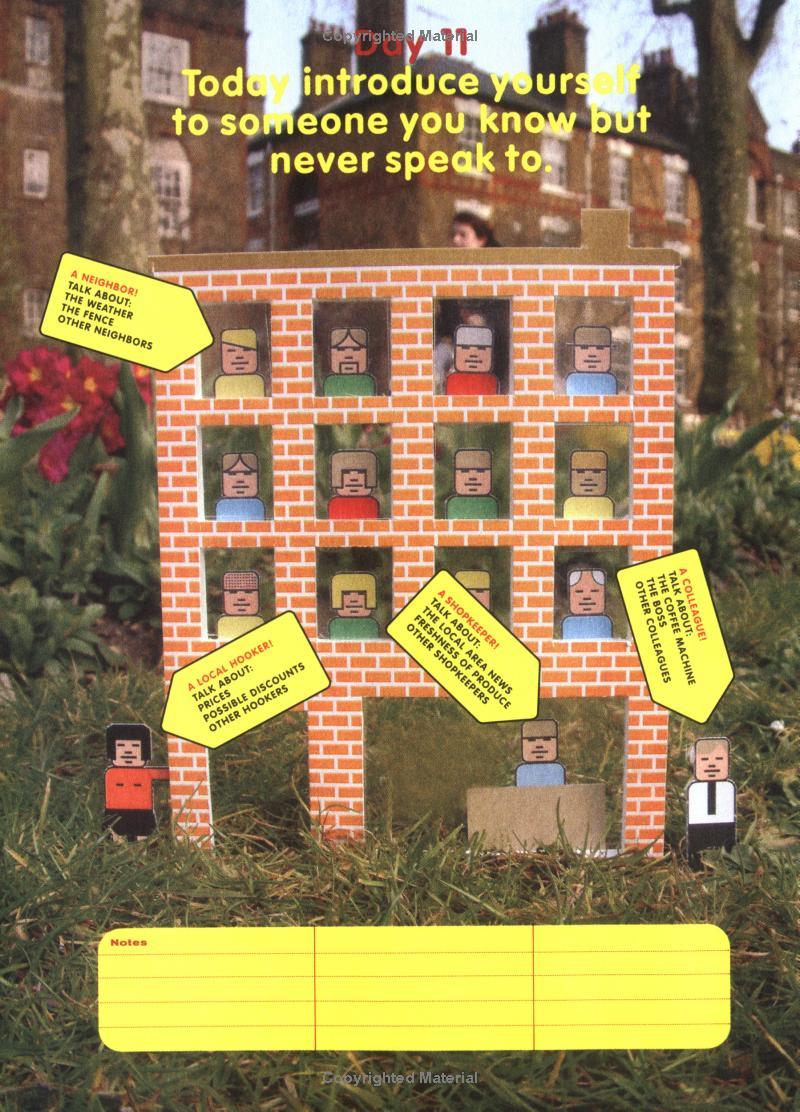

Day 11: Today introduce yourself to someone you know but never speak to

Day 12: Tick off what’s your type

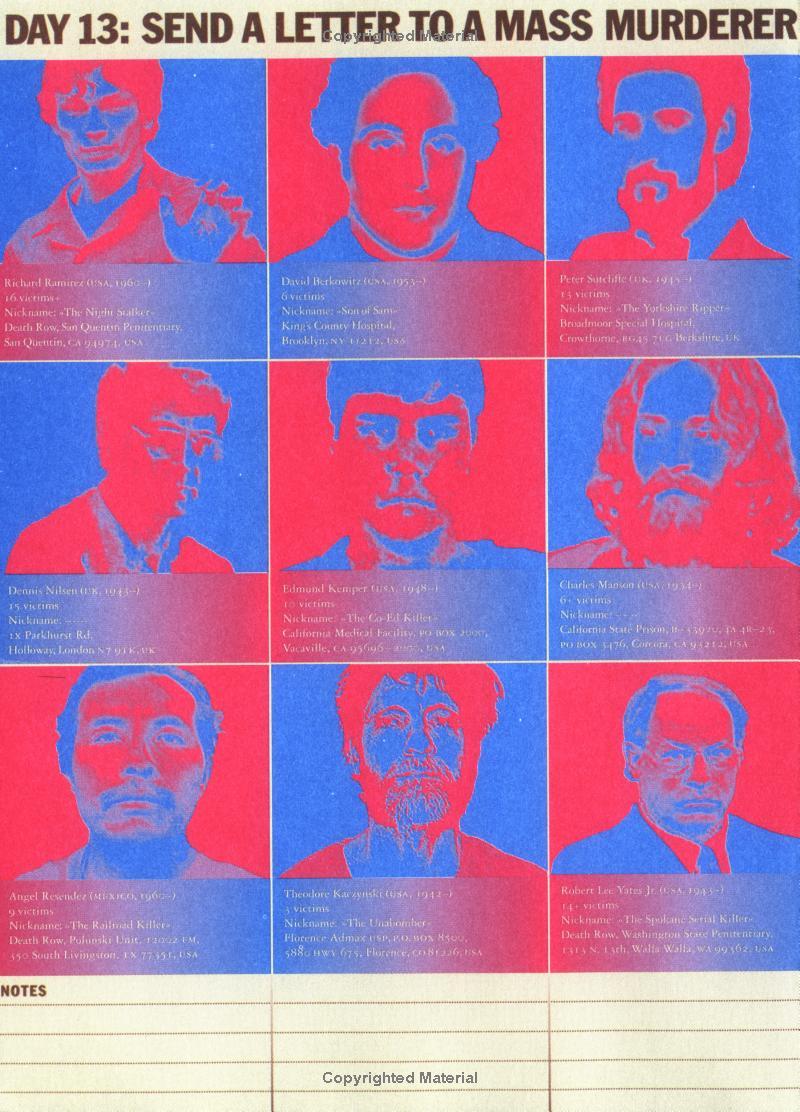

Day 13: Send a letter to a mass murderer

Day 16: Discreetly give the finger to people all day today

Day 17: Eat nothing but asparagus all day long to ascertain just how noxious your pee can get

The history of the Book

Most readers will be surprised to learn that the Book is not entirely new. The present authors have endeavored to bring it back to life. But it has a long and rich history, which Dr. Gunther Pedersen of the Bern Institute of Cultural Studies (Kulturelles Zentrum, Bern) has researched for this edition.

The precise origins of This book will change your life are a matter of academic dispute. So divided are scholars even as to its original title, the truth may never be conclusively established. Over the centuries it has been known variously as The Book of Days, Fate’s Very Own Calendar, Perish Ye Whom Glance Herein, 365 Rollickin’ Rides and Die Entdeckung der Weltgeschichte — amongst many others. Nevertheless we will attempt to outline in broad terms its history, pointing out inconsistencies and gaps in our knowledge, bearing in mind along the way that, as the great Carlyle has said, ultimately history is but a distillation of rumor.

The first mention of the Book is to be found in Herodotus, the Greek father of history, writing in about 450BC. He refers to the curious custom practiced by the Pelasgians of following everyday of the calendar rites written on their oracle’s tablets (Histories, VI.56). Herodotus discusses the derivation of this custom: I may say, for instance, that it was the daughters of Danaos who brought this ceremony from Egypt and instructed the Pelasgian women in it. (II. 171). The Pelasgians, of course, mentioned both by Herodotus and the more reliable Thucydides, are recognized as the majority tribe within the nomadic population of Greece and the Aegean, before their gradual assimilation by the Hellenes. There is therefore a strong case to suggest that the very origins of the Book can be traced beyond the classical age and back co Egyptian civilization, the ultimate cradle of our culture.

Indeed, some have seen fit to speculate on the influence of the (as yet nameless) Book on Egyptian history. Could Pharaoh Akhnaton’s contempt for age-old tradition, for instance, stem from his worship of the Book‘s ancestor? Certainly much has been made of the fact that when his sarcophagus was opened by the American amateur Egyptologist Theodore Davis in 1907, the dusty and unreadable remnants of twelve papyrus scrolls were found at his side. But in truth there is no solid evidence to back this claim.

At this point we should attempt to shed some light on two contentious issues. First of all, which of the multifarious versions is the genuine Book? Fakes and translations are legion. For our purposes, the real Book is the so-called Greek version, as found in Constantinople in 1422 by scholar Giovanni Aurispa (of whom more later). Both in depth and in originality, it stands out as the truest incarnation of the Book, as anyone who cares to study it at the British Museum will surely agree (by appointment with the British Museum Special Finds Dept, London WCIB 3DG). We call it the Original Book, though no one has managed to pinpoint its ultimate authors (many have tried; see for instance H. Beckenbauer, The origins of the Book: Atlantis revealed?, Eon Press, 1954).

Secondly, why is there so little mention of this ancient text in conventional histories? The answer will become readily apparent as we proceed; the Book is essentially an instrument of radical change, unleashing forces too powerful for authorities to control. Thus it has been ignored and hidden away in official accounts; for those who know to look though, its footprints are everywhere.

Following Herodotus, The Book resurfaces now and again in Greek fragments, mostly concerned with Orphism. Anaximander, for instance, tells us of yuyevti, loosely translated as The Book Of Days. It is perhaps then no coincidence that Plato is the first to refer to it at any length, for we know he spent 12 years in Egypt and a deep understanding of Orphic cosmology permeates his works (his contemporary’ Krantor in fact accused him of lifting the Republic‘s political hierarchy straight from the Egyptian caste system). In a little-known appendix to his Sympostum, he has prophetess Diotima of Mantinea argue the following:

What do you think, Socrates, of the study that Euthydemus and others make of that Phoebean text in which their pursuits are commanded day by day? Haven’t you noticed how the course of their existence is varied, when so many people in Athens repeat everyday yesterday’s actions again. Don’t you agree?

By Zeus I do! said [Socrates].

Well then, [said Diotima], can we say that this text is a medium for messages between mortals and the goddess Fate?

Socrates then goes off on something of a tangent regarding the parentage of said goddess Fate; but it is clear from this that the Book was in use round about 400BC It is also surely more than mere coincidence that it is mentioned in the course of the Symposium, famous for its emphasis on homosexual relations between adult males and young men. Could some early Book injunction to experiment sexually have caught on in Greek culture?

The Book then enters a long period of obscurity, along with so many classical masterpieces. True, there is the odd reference to it in Roman texts; Cicero associates it uncritically with Epicureanism, accusing it of being so easily grasped and so much to the taste of the unlearned (Tusculan Disputations, IV, 3). But in truth it was more suited to the imaginative Greek spirit than to the more plodding organizationally-minded Roman outlook, and so never really caught on.

Of course throughout Antiquity the Book was very much intertwined with religion. Early versions might have enjoined Phoenicians to sacrifice goats and suchlike. Indeed it is probable that the religious trend for issuing arbitrary instructions, such as the Ten Commandments, was derived from that very source. But it is with its rediscovery and adaptation in the Renaissance that it enters the modern age.

The Book re-emerges — where else? — in Florence. Under Coluccio Salutati, Chancellor of Florence from 1375 to 1406, there came a new yearning for knowledge of the classical past. Very few authors remained in circulation, with some quasi-extinct; there was only one known manuscript of Catullus in existence anywhere, for example.

In 1392 Coluccio himself found Cicero’s Epistolae Familiares, which signalled the beginning of an intensive search for classical manuscripts. It was directed by Niccolo Niccoli, with the help of his right-hand man, the irrepressibly enterprising Poggio Bracciolini.

In the summer of 1416, Poggio visited St Gall, a 7th century Benedictine monastery 20 miles from Constance in Switzerland. He asked to visit the library, which turned out to have been grossly neglected, a most foul and dimly lighted dungeon at the very bottom of a tower. As he leafed through the dusty old manuscripts, mostly in deplorable condition, Poggios excitement grew. Here he had found a complete manuscript of Quintilian’s Training of an Orator, substantial portions of Cicero, and a partial damaged Roman copy of something enigmatically named the codex diei, the book of days.

Poggio stayed at the monastery and copied it out himself with goose quills and inkhorn over 56 days. He then sent his copy back to Florence for which we must be grateful, as the original was lost in a monastery fire 7 years later. We are also in his debt for making it readable; the original, like most old parchment manuscripts, was copied out in minute Gothic text, which he exchanged for his own much rounder script (which in due course became the basis of modern handwriting).

It would be false to claim that the Florentines immediately recognized the value of the Book, which is why it is hardly mentioned in contemporary accounts. This was partly because the Roman version they inherited was very much incomplete Fragments such as Today abandon all your pursuits in favour of the greatest good of them all ...... chariot! left them bemused rather than amazed. This all changed in 1423 when Giovanni Aurispa arrived in Italy with a vast hoard of original Greek manuscripts, 239 in all, including most of Greek literature: the Iliad, the Odyssey, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Herodotus, Plato, and countless others, all of a sudden given to Florence, along with of course the original Greek copy of the Book. This treasure chest of classical culture was seized, debated and lectured upon avidly by the Florentines. The young Greek scholar Marsilio Ficino translated Plato and the Book, declaring the latter to be one of the crowning achievements of classical civilization. Indeed, his famous inscription in the hallway of the Academy, where the leading lights of Florence used to meet, was meant to bear witness to its influence: Rejoice in the present. Every citizen had a copy; Lorenzo de Medici had his bound in gold leaf. In retrospect, it is hard to resist the conclusion that the Book contributed substantially to the conception of the individual that flowered in Quattrocento Florence. It enshrined the notion of complete man, one who realized all his innate qualities. It also chimed with the new Renaissance perception of time. The agricultural and monastical societies of the Middle Ages moved to the slow rhythm of the seasons and eternity. With their eye firmly fixed on the afterlife, they cared little for daily upheaval. But the Florentines were a manufacturing and trading people, to whom time was precious, to whom indeed time was money. It is no coincidence that a Florentine, Brunelleschi, invented the alarm clock (in between painting masterpieces and building his famous dome).The Renaissance man lived for the here and now, and prized every moment. The Book was part and parcel of this Weltanschauung.

Along with so much else in Florentine civilisation, the Book met its nemesis in the form of Dominican friar Savonarola, who took Florence by storm in the 1490’s with his apocalyptic preaching of hellfire and brimstone against the corrupt citizens who had abandoned the gospels for more wordly pleasures and values. In Savonarola’s vision of Florence as the new Jerusalem, there was no room for the impious free-thinking Book. And in 1497, he tried to make sure all copies were burnt in his infamous Bonfire of the Vanities, along with copies of Boccaccio, Petrarch, paintings by Botticelli and other masterpieces. Almost all Books were thus consumed by the flames, and none would likely have survived if he had held power much longer. But in 1498 he finally went too far and was excommunicated by the Pope, then hanged in the Piazza della Signoria and thrown on a bonfire of his own. The Florentine Renaissance was at an end.

Thankfully one of the factors in its downfall also guaranteed its survival. When Charles VIII and the French Army invaded Italy in 1494, precipitating the demise of the Medici dynasty, they were spellbound by the scale and beauty of the Florentine achievement: the Medici palace, the sculptors and painters, the tapestries... And so as conquering king, he shipped back to Amboise 21 artists and craftsmen, manuscripts, pictures, over 34 tons of marble — effectively transplanting the Renaissance back to France.

The Book went with him of course. It was in large part because the French held the original copy that Leonardo da Vinci accepted Francois Is offer to move to France from Italy in 1516, so that he could study it. For the next few centuries, under the absolutist reign of the Bourbon kings, the Book held a much lower profile, and was considered mostly a quaint, even frivolous curio. Voltaire though saw its subversive potential and in 1778 translated it into French, none too scrupulously, adding much of his own trademark irony in the process.

CE LIVRE VOUS CHANGERA LA VIE, as it had become, then re-emerged in aftermath of the French Revolution in the unlikely hands of Donatien Alphonse Francois Marquis de Sade. Sade, of course, was an indefatigable scribbler himself and it will readily be perceived how the livre’s mix of arbitrary dictates fired up his imagination. A dozen days he wrote survive. The least unprintable enjoin followers to copulate variously with goats, toads, dwarves and grandmothers (the conceit here being to precipitate a fatal heart attack). Baudelaire claimed to have read the full-year Sadean version, describing it in his correspondence as a veritable Kamasutra of pain. No copy alas is extant.

The original Book fell victim to Sade’s notoriety and excesses. On March 6, 1801, Parisian police arrived suddenly to search the premises of Sade’s publisher Nicolas Mosse, in hot pursuit of an obscure pamphlet, Zoloe, which Sade had allegedly penned against Napoleon and Josephine. The accusation turned out to be false, but the police nevertheless seized all the remaining stock of his novel Juliette, and of course his copy of the Book. Napoleon, it seems, was ungrateful for this new acquisition, for he had Sade imprisoned without trial, and later transferred to Charenton insane asylum, where he stayed locked up until his death in 1814. In 1810, Napoleon punished him further by signing a decision to keep him in detention and forbidding all communication with the outside world, depriving him also of any writing materials. Whether this fate would have befallen him without the Book is quite possible, but it is clear that Napoleon’s unlawful confiscation of such a valuable manuscript helped consign the Marquis to political oblivion.

There is no record of Napoleon himself directly referring to the Book, but there is no doubt he would have perused it; it is known that he iiked books-even in difficult times at St. Helena he had 3370 books in his library. But as Madame de Remusat informs us, he was really ignorant, having read very little and always hastily. The Book‘s clear and concise orders would have suited his military temperament.

Few of his career-defining decisions can be traced directly to the Book‘s dictates, with one exception: the Louisiana Purchase. Historians have always been somewhat puzzled by Napoleon’s agreement to suddenly relinquish French possession of what was then called Louisiana but in fact encompassed 13 current states and over 900,000 square miles, for a relative pittance (15 million dollars). This was one of the greatest real estate deals in history, doubling the size of the United States, transforming it into a world power and effectively ending France’s dreams of worldwide presence overnight. No one was more surprised than Napoleon’s finance minister, the Marquis de Barbe-Marbois, when he was instructed to reverse official policy on the morning of April 4, 1803. Perhaps if he had known that day’s Original Book entry, he would have been wiser: Aujourd’hui, debarrassez vous d’une source d’ennui (Today, get rid of something tiresome). Thus was the whole course of 19th century geopolitics and the destiny of nations transformed in one stroke.

On a more general note, it is surely not coincidental that the year Napoleon acquired the Book corresponds to that when his ego exploded: he was already First Consul by 1801, but by 1802 he had made himself Consul for Life, and by 1804 he was Emperor. Perhaps he took the Book‘s emphasis on extreme individualism at face value. Some historians even posit he kept it close to his heart in his famous Imperial greatcoat, hence his famous position right hand tucked inside the tunic. Certainly he took it with him on all his major campaigns, and indeed this is how it was acquired by its next owner, one Alexei Fedrovsky. As Napoleon retreated across the Berezina in December 1812 after his disastrous invasion of Russia, one of his staff officers, a Bordelais by the name of Ramballe, was hastily put in charge of the Emperor’s remaining possessions as Bonaparte fled back to Paris in a fur-laden sleigh. Ramballe was immortalized by Tolstoy in War and Peace, where we find him ragged and near-delirious with his orderly Morel sharing a campfire with Russian soldiers near Krasnoe. Alas, he never made it back to Bordeaux. Like so many thousands, both French and Russian, worn out by the sub-zero temperatures and incessant gales, he froze to death drunk in the knee-deep snow on the roadside near Orsk, only ten miles from the Prussian border. The Book was found amongst other papers by a band of pillaging cossacks, more interested in mens’ boots than any obscure bundle of documents. They dumped the lot at their local billet, the castle of Alexei Fedrovsky, a count exiled from Moscow for political reasons in 1807. Alexei was famous for his imaginative cruelty: on at least one documented occasion, he sent his servants out early one morning to the local weekly village market, ordering them to buy up all the food available so that his peasant neighbors would have to starve for the week.

Fedrovsky was an early exponent of Russian political dissent, a radical before his time and more by temperament than ideology: he advocated the overthrow of Tsar Alexander on the grounds that his beard was not sufficiently manly. Rather like Sade, he was exiled at the insistence of his family, who kept finding their relative the laughing stock of Muscovite society. Nevertheless, Fedrovsky maintained links with the early precursors of Russian dissent. Though he did not make much use of the Book himself (except when following its edicts could annoy his loved ones), he did pass it on upon his death in 1827, along with copious notes on facial hair throughout history, to his anarchist friend Bakunin. Bakunin, at the time, was not yet quite the international firebrand and scourge of governments worldwide that he became in the 1850s. But he was still too impetuous and restless to sit down and take orders from a mere manuscript. He was also permanently penniless, and so it came that he gave the Book away in exchange for some cabbage soup at the house of a friend of his in 1832. Fortunately, this friend was none other than literary critic Vissarion Grigorievich Belinsky, perhaps the man most deserving of the Book anywhere on the planet at the time.

By the early 1830s, Russia was a moral and intellectual vacuum. The burgeoning young intelligentsia was desperate for spiritual nourishment, caught between the dumbly repressive autocracy of Nicolas I on the one hand, and the illiterate groaning peasant masses on the other. With no native role models to look up to, the Russian youth avidly absorbed every Western notion with a hint of revolutionary change. This was fertile ground for the Book, and no one took it up more forcefully than their effective spokesman, Belinsky, the conscience of the Russian intelligentsia as Isaiah Berlin so aptly terms him. To Belinsky, books and ideas represented salvation from the grim material philistine circumstances of Russian life. His was a philosophy of engagement; a mans life should reflect his beliefs, however much of a struggle was involved. Behavior had to follow on from ideas. He lived in a state of permanent moral frenzy, of constant searching after the true ends of life. It is no surprise that the Book, with its zeal for unending revolutionary experimentation and disregard for social conventions, appealed to him immediately. He copied out some of the more extreme days like Go up to a member of the ruling classes and tell him how ignomious he is or the religious-themed God is dead. Make a small clay model of him and bury him in your back garden and disseminated them amongst his friends and fellow radicals. He even penned a few pages of his own on the subject of serfdom (Grab the nearest serf and run for the woods to free him, Paint serfdom is the doom of the human spirit on the wall of the Kremlin). This sort of sentiment did not endear him to the Tsarist police as can readily be imagined.

And indeed it is reading out these pages of Belinsky’s (and not merely his more famous 1847 Letter to Gogol) that got Dostoevsky condemned to death and sent to Siberia. By then Belinsky had alas died of consumption. But such had been his influence that he can legitimately be called one of the founders of the movement that led to the Russian Revolution.

After his death the Book continued as one of the underground texts that fuelled the revolutionary fire across Russia and in the various places of exile where Russian radicals congregated. Though it has to be said that Belinsky probably best understood the essence of the Book, which is its permanent encouragement of the flowering of the individual human spirit, the expression of the whole of man’s nature, unfettered by the shackles of tradition. Later generations of revolutionaries were to put it to far more prosaic use. For the rest of the 19th century the Book passed from radical to radical. It is difficult to know its exact history’ during this period as its successive owners were understandably publicity-shy and left few traces of their whereabouts and activities. The Populist-turned-Marxist leader Plekhanov seems to have recuperated it sometime in the 1880s. He in turn entrusted it to his star pupil Lenin, who found its radical tone of great comfort during his lonely years abroad in Geneva and Paris. Indeed it played a direct part in the Russian Revolution. During the 1905 uprising, Lenin had decided to stay abroad, obeying his more prudent instincts. When it came to the February 1917 uprising though, he consulted the Book on February’ 12, which urged him thus: Today plan a surprise trip somewhere hot. Immediately he resolved to set off for Moscow in the famous sealed train and changed the course of the revolution, ending with the Bolshevik takeover in October 1917.

More generally, it is clear that the nature of Lenin’s rule was influenced by the Book, as reflected both in his ruthless drive and in the speed of his decisions. By the time Lenin died in 1924, he had grown mistrustful of both his comrades Trotsky and Stalin, and so bequested the Book to Nicholas Bukharin, whom he called in his testament the greatest and most valuable theoretician of the party. His theorizing was no real match for Stalin’s peasant cunning though, and the Book soon got Bukharin into trouble. To be fair, it was no easy task to Sovietize what was essentially an individualistic bible, no matter how glorious its part in the history of the Revolution. Whole schools were given special versions, with tasks such as Today, work to achieve the goals of the Five-Year-Plan or Dispose of ten kulaks by lunchtime! (at the height of the collectivization hysteria in 1929). Yet this did not go far enough for Stalin. Unintentional lapses such as How much do you love Comrade Stalin on a scale of 1 to 1000? were seen as perilously close to inviting dissent, and undoubtedly contributed to the downfall and eventual execution of Bukharin. But there was worse to come for the Book, or rather its bastardized Stalinist form. By the early 30s, such was Stalin’s paranoia and fear of Trotskyist contraband that everything published (not just the Book) was expected to be rewritten in his own personal style Half the days in the 1934 Correct edition were about Stalin directly (Compose a realist poem to the glory of the Revolution and its leader and nail it to an enemy of the working classes). The other half were merely written in his plodding repetitious pseudo-scientific manner (Today help organize your local communist associations with a view to undermining international capitalist superstructures). Eventually fault was found with this edition too and its supervisor Sokolnikov was purged in the Trial of the Seventeen in 1937 Thus ended the sorry saga of the Soviet Book.

Fortunately for us, the original emerged unscathed. Trotsky, who had seen which way the wind was blowing, managed to procure Bukharin’s copy and took it with him in exile in 1929. He wandered about for years, persecuted at a distance by Stalin who still feared his moral authority, until he eventually landed in Mexico. There he found a house in Coyoacan near Mexico City with his wife Natalia Sedova. The Mexican Communist Party was strong but deeply divided into Stalinist and anti-Stalinist factions. Trotsky soon settled in, making friends with local sympathizers. He was particularly close to revolutionary muralist Diego Rivera and even closer to his painter wife Frida Kahlo. Rivera had helped Trotsky gain asylum in Mexico; they were comrades until 19^8 when they split over ideological differences, and rumors of an affair between Trotsky and Kahlo.

Finally history caught up with him when Spanish communist and Stalinist agent Ramon Mercador smashed his head with an alpine pickaxe on August 20, 1940 while he was writing an accusatory biography of his nemesis. Rather gruesomely, he did not die from the blow’ but stood straight up, screamed, and started pelting his assassin with everything within reach, including his dictaphone. His eventual death the next night went relatively unnoticed, as the world was otherwise preoccupied at the time.

Trotsky’s wife Natalia couldn’t find the Book after her husbands traumatic death. She suspected Stalin’s agents had stolen it back, but the truth was closer to home. Frida Kahlo had indeed had an affair with Trotsky, in the course of which she’d borrowed the Book. When the two of them broke up under suspicion from their spouses, she never returned it. Trotsky would not have been best pleased with her behavior after his death: both her and Rivera showed little sympathy for him, seeking readmission to the Stalinist Mexican Communist Party and denouncing Trotskyism. Kahlo added insult to injury by slandering Trotsky as a thief and a coward. Her last painting was an unfinished portrait of Stalin, started after the dictator’s death in 1953, and interrupted by Kahlo’s suicide in 1954. By one of those minor quirks of which history is fond, the Book then ended up in the hands of the FBI. Kahlo had died at the height of the McCarthyite hysteria in the US. Under heavy political pressure, all government security agencies were looking for reds under the American bed, particularly writers and artists whom everyone knew’ were susceptible to communist leanings at the best of times. Mexico was America’s backyard. Naturally the spotlight fell on Rivera and Kahlo, artists of international renown with documented links to one of the chief instigators of the Russian Revolution.

J. Edgar Hoover himself, head of the bureau since 1924 and vehement anti-commie, took an interest in their activities, so that immediately upon Kahlo’s death FBI agents in Mexico raided her house and made off with addresses of supposed Communist sympathizers, and Trotsky’s copy of the Hoot, no doubt regarding it as some kind of timing masterplan for global insurrection.

The investigation into Kahlos anti-American activities eventually petered out for want of firm evidence. No mention is made of the Book, for the simple reason that Hoover kept it to himself. Like so many powerful men before him, he fell under its spell. Perhaps to those used to the hubris of arbitrary authority and unquestioning obedience, submitting to the Book‘s straightforward orders represented something of a liberation.

In any event, its influence on Hoover was more tragicomic than machiavellic. The entry that particularly caught his eye was March 24, 1958: Experiment with forbidden fantasies. The result saw him attending at least two gay orgies at the New York Plaza Hotel in 1958, wearing a fluffy black dress with flounces and lace stockings and high heels and a black curly wig according to one witness. He was introduced as Mary and allegedly engaged in sex with boys as the Bible was read to him, throwing the Good Book down at climax. The latter claim is not considered reliable; but certainly the episode explains why the FBI had limited success against the Mafia during his long tenure. With blackmail material such as this, underworld bosses Frank Costello and Meyer Lansky had little to fear from J. Edgar.

The Book has lain in Hoover’s classified files since his death in 1972. Under Exec. Order 11152 it was meant to be declassified 30 years later in May 2002 The FBI claim a clerical error prevented it from being found until November 2002, when it was finally made available to the public, and even then it languished at the bottom of a box in the FBI archive hall in Washington. It is only by amazing luck that the present authors, whilst engaged in a much larger authoritative study of the JFK Roswell cover-up, found it and decided to dust it off and update it for the benefit of the present generation. As with so much pertaining to this incredible artifact, it is impossible to tell whether the delay was deliberate.

One thing that history teaches us is certain: the Book has always threatened various powerful groups by its very existence. May this new edition continue to do so.

Dr. Pedersen (1956–2003)